Abstract

We describe the first human case of lobomycosis caused by Lacazia loboi in a 42-year-old white male resident of Georgia. The patient had traveled to Venezuela 7 years earlier, where he had planned to rappel down Angel Falls in Canaima. Although he never actually rappelled the falls, he did walk under the falls at least three times, exposing himself to the high water pressures of the falls. He noticed a small pustule with surrounding erythema developing on the skin of his right chest wall. The lesion gradually increased in size and had an appearance of a keloid. For cosmetic reasons, the patient sought medical treatment to remove the lesion. After an uncomplicated excision of the lesion, the patient recovered completely. The excised tissue was fixed in formalin for pathologic examination. Tissue sections stained by hematoxylin and eosin, periodic acid-Schiff stain, and Gomori methenamine silver stain procedures showed numerous histiocytes, multinucleated giant cells, and numerous globose or subglobose, lemon-shaped cells producing multiple blastoconidia connected by narrow tube-like connectors and catenate chains of various lengths characteristic of L. loboi.

Lobomycosis is characterized by slowly developing variably sized cutaneous nodules after a traumatic event. The dermal nodules manifest as either smooth, verrucose, or ulcerated surfaces which can attain the size of a small cauliflower-like keloid (7, 11). The onset of the disease is generally insidious. The increase in size or number of lesions is a slow process, progressing over a period of 40 to 50 years (11). The lesions are composed of granulomatous inflammatory tissue containing numerous globose or subglobose to lemon-shaped, yeast-like fungal cells singly or in simple and branched chains.

The etiologic agent of lobomycosis is an obligate pathogen of humans and lower mammals which has yet to be isolated and grown in vitro; therefore, nothing is known of its basic cultural characteristics and growth (3). Diagnosis is based on demonstrating the presence of globose, thick-walled yeast-like cells ranging from 5 to 12 μm in diameter in lesion exudate or tissue sections. The organism multiplies by budding, and thus mother cells with single buds are often observed. However, characteristic sequential budding leads to the production of chains of cells that are linked to each other by a tubular connection, or isthmus. Budding may occur at more than one point on a cell, giving rise to branched or radiating chains of cells. These thick-walled, hyaline, spherical cells with chains of cells interconnected by tubular connections are the basis on which a diagnosis of lobomycosis rests. The thick-walled, budding hyaline cells with catenate chains of conidia can be readily observed in tissue smears or exudates mounted in 10% KOH or in Calcofluor mounts (3). Surgical excision of localized lesions or single plaque infections is the optimal therapy. In cases involving larger areas of infection, treatment with clofazimine (Lamprene) is recommended. At present, the disease does not have a satisfactory medical treatment (11).

A new monotypic genus, Lacazia, with Lacazia loboi as the type species, was recently proposed by Taborda et al. (15) to accommodate the obligate etiologic agent of lobomycosis in mammals. The continued placement of L. loboi in the genus Paracoccidioides as Paracoccidioides loboi O.M. Fonseca et Lacaz was found to be taxonomically inappropriate. The older name Loboa loboi Ciferri et al. was considered to be a synonym of Paracoccidioides brasiliensis (15).

The human disease is endemic in the tropical zone of the New World and has been reported in central and western Brazil, Bolivia, Colombia, Costa Rica, Ecuador, Guyana, French Guiana, Mexico, Panama, Peru, Suriname, and Venezuela (11). There have been isolated cases reported in Holland (5, 14) and a doubtful case in Bangladesh (12, 15). Identification of the disease in dolphins widened the geographic distribution of the disease. Seven cases of lobomycosis involving two species of dolphins, namely, marine dolphins (Tursiops truncatus) and marine freshwater dolphins (Sotalia fluviatilis) (4, 15), have been reported for Florida, the Texas coast (2, 4, 8), the Spanish-French coast, the South Brazilian coast, and the Suriname River estuary (11, 15). Even though lobomycosis in dolphins has been reported in the United States, to our knowledge no human infection has been reported so far. We describe the first human case of lobomycosis in the United States in a white male resident of Georgia. The patient gave a history of travel to Venezuela, one of the countries where lobomycosis is endemic.

Case report.

A 42-year-old white male patient, a resident of Georgia, presented to a general surgeon. The patient requested removal of a skin lesion on his right chest wall for cosmetic reasons. Seven years earlier, the lesion had started as a small pustule with surrounding erythema. At that time, the patient pierced the pustule with a needle and then expressed a tiny amount of bloody fluid. Afterwards, the lesion developed into a small nodule that gradually increased in size. Some mild itching was associated with the lesion but there was no pain or discomfort.

Two and one-half years prior to the appearance of the pustule, the patient had traveled to Venezuela, where he had planned to rappel down Angel Falls in Canaima. Although he never actually rappelled the falls, he did walk under the falls at least three times. On each of these occasions, he was exposed to extremely high water pressures due to the height (3,000 ft) of the falls. Each exposure lasted around 30 min. Although he was wearing a diving suit, he said that the water penetrated the suit, leaving him soaked. He also swam in the river at the bottom of the falls. His only previous travel outside the United States involved two trips to Mexico in the late 1980s, during which he performed vertical rappelling in caves. His only water exposure during the Mexican trips was limited to showering in the local facilities. He was not aware of any injury to the skin during any of these adventures.

On physical examination, the patient was found to have a raised 3.5- by 2-cm reddish purple nodule with a smooth surface and distinct margins located on the right chest wall in the midaxillary line at the level of the eighth rib. It had the appearance of a keloid. After an uncomplicated excision, the excised tissue was sent for pathologic evaluation.

Histologic examination.

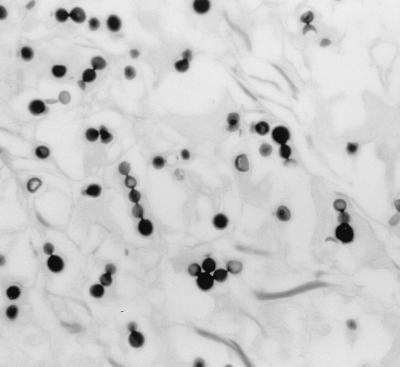

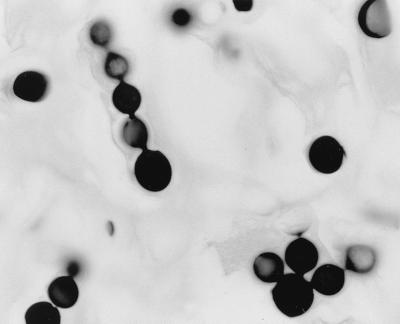

The excised tissue, fixed in formalin, was a skin ellipse which measured 4.9 by 2.6 by 0.6 cm, with the lesion measuring 3.5 by 2.1 cm. No fresh tissue was saved for bacterial or fungal cultures. Tissue sections were prepared and stained by hematoxylin and eosin, periodic acid-Schiff stain, and Gomori methenamine silver stain procedures. Microscopic examination of the tissue sections showed a nodular inflammatory infiltrate of foamy histiocytes, multinucleated giant cells, and scattered lymphocytes. Throughout the infiltrate were numerous globose or subglobose, lemon-shaped cells that measured 5.0 to 11.0 μm in diameter. Many cells showed thick refractile walls and reproduced by single and multiple budding. The buds were attached to the mother cell by narrow tubular connections, giving a beaded appearance. There were many chains of cells showing narrow tubular connections (Fig. 1 and 2) characteristic of L. loboi (3, 7, 15).

FIG. 1.

Excised tissue section showing globose and subglobose budding cells and chains of blastoconidia of L. boboi. Gomori's methenamine silver stain was used. Magnification, ×140.

FIG. 2.

Globose to subglobose cells in a chain with distinctive tubular connectors and a cell showing multiple buds. Gomori's methenamine silver stain was used. Magnification, ×770.

The globose and subglobose budding cells of L. loboi resemble budding cells of P. brasiliensis in tissue. However, the central mother cells of P. brasiliensis become large and thick-walled compared to the daughter cells, which remain smaller. In contrast, yeast cells of L. loboi remain consistent in diameter, giving rise to branching chains of blastoconidia (15). In addition, according to Taborda et al. (15), the cell wall of L. loboi contains constitutive melanin, which can be detected by the use of the Fontana-Masson histologic stain. The walls of cells of P. brasiliensis are not known to contain melanin. L. loboi has never been cultured in vitro. On the other hand, P. brasiliensis can be grown in artificial culture and is known to be a dimorphic pathogen.

With the greater frequency of international travel, many cases of endemic mycosis are often diagnosed in areas of nonendemicity. In the United States, cases of paracoccidioidomycosis (a disease endemic in Latin America), African histoplasmosis (endemic in Africa), and penicilliosis marneffei (endemic in Southeast and Far East Asia) have been diagnosed (1, 6, 9, 10, 13) in patients with a history of travel or residence in the areas of endemicity. The case histories of such imported mycoses often illustrate an important feature of these diseases, namely, their long dormancy periods. These diseases often go through a remarkably long quiescent period of no symptoms. These dormancy periods may range from a few months to several years (1). In lobomycosis, the onset of the disease is generally insidious and difficult to document. The increase in size and number of lesions is a slow process; it can take 40 to 50 years (11). This latency period often makes it important to note the patient's history of travel or stay in areas of endemicity to arrive at a proper diagnosis. In the present case, the incubation period was 7 years. The history often reveals the cause being a trauma, for example, an arthropod sting, a snake bite, a cut from an instrument, or a wound acquired while cutting vegetation. The causal agent of lobomycosis appears to be saprobic in aquatic environments, which probably plays an extremely significant part in its life cycle (11). In the present case, the patient's listed activity involved exposure to high water pressures due to the height of the water falls and swimming in the river. The surgical excision led to uncomplicated cure of the infection.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ajello L, Polonelli L. Imported paracoccidioidomycosis: a public health problem in non-endemic areas. Eur J Epidemiol. 1985;1:160–165. doi: 10.1007/BF00234089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Caldwell D K, Caldwell M C, Woodward J C, Ajello L, Kaplan W, McClure H M. Lobomycosis as a disease of the Atlantic bottle-nosed dolphin (Tursiops truncatus Montagu, 1821) Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1995;24:105–114. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1975.24.105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chandler F W, Kaplan W, Ajello L. A colour atlas and textbook of the histopathology of the mycotic diseases. London, England: Wolfe Medical Publications Ltd.; 1980. pp. 73–75. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cowan D F. Lobo's disease in a bottlenose dolphin (Tursiops truncatus) from Matagorda Bay, Texas. J Wildl Dis. 1993;29:488–489. doi: 10.7589/0090-3558-29.3.488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.De Vries G A, Laarman J J. A case of Lobo's disease in the dolphin Sotalia guianensis. Aquat Mamm. 1973;1:1–8. [Google Scholar]

- 6.DiSalvo A F, Fickling M, Ajello L. Infection caused by Penicillium marneffei: description of first natural infection in man. Am J Clin Pathol. 1973;60:259–263. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/60.2.259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kwon-Chung K J, Bennett J E. Medical mycology. Philadelphia, Pa: Lea Febiger; 1992. pp. 514–523. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Migaki G, Valerio M G, Irvine B, Garner F M. Lobo's disease in an Atlantic bottle-nosed dolphin. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 1971;159:578–582. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pautler K B, Padhye A A, Ajello L. Imported penicilliosis marneffei in the United States: report of a second human infection. Sabouraudia J Med Vet Mycol. 1984;22:433–438. doi: 10.1080/00362178485380691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Piehl M R, Kaplan R L, Haber M H. Disseminated penicilliosis in a patient with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1988;112:1262–1264. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pradinaud R. Loboa loboi. In: Collier L, Balows A, Sussman M, editors. Topley and Wilson's microbiology and microbial infections. Vol. 4. New York, N.Y: Oxford University Press; 1998. pp. 585–594. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rumi T K, Kapkaev R A. Keloid blastomycosis (Lobo's disease) Vestn Dermatol Venerol. 1988;62:41–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shore R N, Waltersdorff R L, Edelstein M V, Teske J H. African histoplasmosis in the United States. JAMA. 1981;245:734. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Symmers W S. A possible case of Lobo's disease acquired in Europe from a bottle-nosed dolphin (Tursiops truncatus) Bull Soc Pathol Exot. 1983;77:777–784. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Taborda P R, Taborda V A, McGinnis M R. Lacazia loboi gen nov., comb. nov., the etiologic agent of lobomycosis. J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37:2031–2033. doi: 10.1128/jcm.37.6.2031-2033.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]