Abstract

Objective

To evaluate the effectiveness of autologous platelet concentrates (APCs) as adjuncts on accelerating orthodontic tooth movement (OTM) of the human subjects undergoing orthodontic treatment and to critically appraise the available literature.

Methods and materials

Five electronic databases (PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science, Embase, and Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials) were searched from 2000 up to May 2021 to retrieve eligible randomized controlled trials (RCTs) investigating patients who underwent orthodontic treatment that involved OTM of maxillary and mandibular incisors and canines. All the enrolled cases were treated with APCs and had no local or systemic interfering factors. The quality of the included studies was assessed using the modified JADAD scale. The effect sizes were assessed using mean difference (MD). The heterogeneity analysis was conducted using (I2) statistic at α=0.10.

Results

Finally, seven RCTs were included in the qualitative, and two RCTs were included in the quantitative analysis. The meta-analysis was performed regarding the effect of injectable platelet-rich fibrin (I-PRF) on the rate of canine tooth movement in millimeters at different intervals of the 1st, 2nd, and 3rd months. In the 1st month, I-PRF (WMD:0.12mm, CI95% −5.01 to 5.24, I2=90%) did not significantly affect OTM. In the 2nd month, I-PRF (WMD:0.66mm, CI95% 0.60 to 0.73, I2=10%) significantly increased the OTM. However, in the 3rd month, I-PRF did not significantly increase the OTM (WMD:0.54mm, CI95% −1.38 to 2.47, I2=67%).

Conclusions

According to the low certainty of evidence about this topic, providing a definite conclusion is not possible. However, applying I-PRF seems to be efficient in accelerating the OTM of the canines. Further high-quality studies with larger sample sizes will be indispensable to validate this conclusion.

Keywords: Platelet-rich Plasma, Platelet-rich Fibrin, PRP, PRF, Tooth Movement Techniques

Introduction

Orthodontic tooth movement (OTM) results from an interactive process regulated by mechanical forces and remodelling of the alveolar bone and periodontal ligament (PDL) [1]. Bone remodelling is a process through which bone resorbs at the pressure sites, and bone forms at the tension sites. Applying mechanical force to the teeth will cause local alteration in the blood flow, resulting in the release of various inflammatory mediators such as growth factors, cytokines, neurotransmitters, and arachidonic acid metabolites [1,2]. The aforementioned series of actions play an imperative role in the bone remodelling process and, accordingly, OTM [3]. OTM is also considerably dependent on the rate of bone and periodontal tissue turnover and the density of the bone [4,5]. In this regard, a comprehensive insight toward confounding factors on OTM is of utmost importance to better optimize the orthodontic treatment protocols.

As orthodontic treatments can take relatively long periods, the chance of developing treatment-related complications such as dental caries, periodontal diseases, external root resorption, temporomandibular disorders (TMDs) are conceivable [6]. In this regard, various methods have been exploited to accelerate OTM such as utilization of lasers, mechanical vibration, ultrasound, corticotomy, corticision, piezocision, etc [7]. Among the suggested approaches, surgical procedures have caught considerable attention [8]. The basis of this approach was first explained by Frost [9] as the regional acceleration phenomenon. According to the phenomenon, surgical approaches can play an imperative role in changing the bone structure and enhancing the rate of OTM. However, the complications of the above-mentioned surgical interventions in orthodontic treatments can avoid their widespread applications in daily practice. The adverse effects of the current surgical interventions are periodontal tissue destruction, interdental bone loss, attached gingiva defects, and pain and discomfort [10,11]. More recently, to reduce the incidence of the aforementioned orthodontic treatment-related and surgical complications, various biological substances such as prostaglandins (PGs), vitamin C and D, human hormones, autologous platelet concentrates (APCs), and so on have been utilized as an adjunct to promote the rate of OTM [1,12].

Among all of the above-mentioned biological substances, APCs as one of the main candidates have caught extreme attention during the last few years. APCs can be easily processed in clinical practice by obtaining a blood sample and performing centrifugation at a specific speed and time [13,14]. In this regard, different generations of APCs [platelet-rich plasma (PRP) and platelet-rich fibrin (PRF)] have been introduced to act as biological substances aiding the tissue regeneration process [14,15]. These biological substances have exhibited acceptable anti-microbial and anti-inflammatory effects, as well as highly regenerative potentials [16–18]. Furthermore, with the prolonged release of various growth factors and cytokines, APCs can provide a suitable environment for proliferation, migration, adhesion, and differentiation of various cells and, consequently, enhancing the tissue turnover [19]. All of these favorable characteristics make APCs an ideal choice for clinical utilization. Since these biomaterials can be easily prepared as a chairside procedure [20], and their promising efficacies in tissue regeneration are evident [21], their employment has been recently regarded in orthodontic treatments [7,22–27]. Since several studies have assessed the clinical outcomes of different APCs [PRP, leukocyte-PRF (L-PRF), and injectable-PRF (I-PRF)] on OTM [7,22–27], it is imperative to evaluate the efficiency of these biological substances on OTM and investigate if they have any benefit in acceleration and enhancement of OTM or not. Therefore, this systematic review and meta-analysis aims to map the current literature and critically appraise the available published randomized controlled trials (RCTs) with reference to the efficacy of APCs on OTM.

Materials and methods

Protocol development

All aspects of this systematic reviews’ methodology were conducted in accordance with the 2020 updated PRISMA guidelines for systematic reviews [28]. The protocol of this study was previously submitted and registered in PROSPERO (CRD42021243711).

Eligibility criteria

Table I illustrates the eligibility criteria for the aspects of participants, intervention, comparison, outcomes, and research design (PICOS). All prospective RCTs, involving healthy individuals, investigated the adjunctive effect of APCs on the rate of OTM were considered for inclusion. Comparisons were made to the placebo intervention and no administration of the investigated APCs. Studies comparing different APCs without including a placebo or administration group, non-comparative studies, reviews, and systematic reviews with or without meta-analyses were excluded. Studies in languages other than English or Persian were excluded from our review considering the linguistic competency of the research team.

Table I.

Eligibility criteria for the present systematic review and meta-analysis.

| Domain | Inclusion Criteria | Exclusion Criteria |

|---|---|---|

| Participants | - Patients undergoing orthodontic treatment with fixed appliances without any local or systemic interfering factor & with permanent dentition in maxilla & mandible except the third molars. | - Human subjects undergoing orthodontic treatment with systemic or local interfering factors, such as pregnancy, lactation, systemic diseases, specific medication intake, etc. - Human subjects with a history of previous orthodontic treatment. |

| Intervention | - Local injection or placement of the autologous platelet concentrates, e.g., PRP, L-PRF, or I-PRF to facilitate tooth movement. | - Local or systemic administration of other biological agents such as Vitamin D, Hormones, Prostaglandins, etc. - Application of any other intervention, such as drugs, piezocision, surgical interventions, low level laser therapy, vibration, etc. |

| Comparison | - Placebo intervention or no intervention | - |

| Outcome | - Qualitative or quantitative data regarding the rate of tooth movement measured by various measurement tools, such as stone or digital study casts, calipers, flexible ruler, radiographies, etc. | - |

| Study Design | - Randomized controlled trials. | - Case reports, narrative reviews, systematic reviews with or without meta-analysis, letters to the editors, short communications, in-vitro studies, ex-vivo studies, animal studies, and non-comparative studies. |

Information sources and search strategy

An electronic search using five databases (PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science, Embase, and Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials) was performed, which is illustrated in Supplementary Table I. Articles published from 2000 up to May 24, 2021, were considered. Besides, the reference list of the eligible included studies and other relevant reviews were also screened for possible inclusion of additional relevant studies.

Study selection

The titles and abstracts of the retrieved articles were independently screened by three reviewers (NF, MAA, and PF) based on the inclusion criteria. The retrieved articles were verified for any possible predatory publication. Discrepancies were solved by discussion among all authors. The full texts of the previously selected abstracts were acquired. The screening procedure was carried out independently by the three reviewers (NF, MAA, and PF). Then, for data extraction, articles that fulfilled the inclusion criteria were processed.

Data collection and data items

The data from the selected studies were collected using a customized data extraction form. The information, including: Name of the authors, year of publications, type of studies, specifications of the treatments, characteristics of the participants, duration of treatments, and outcome measures, were all extracted.

Quality assessment of the individual studies

Three authors (NF, MAA, PF) independently evaluated the quality of included studies in this systematic review and meta-analysis using the modified JADAD scale. RCTs with a score of > 5 were considered as high quality, RCTs with a score of ≤ 3 were considered as low quality, and otherwise, they were considered as moderate quality. Consensus discussions with all authors were held to solve any disagreements.

Strategy for data synthesis

OTM of maxillary and mandibular canines was selected as the primary outcome measure for the current meta-analysis, and the most homogenous studies that had reported mean and standard deviation values regarding the primary outcome in specific timepoints were included in the meta-analysis. The effect sizes were calculated using weighted mean difference (WMD) and corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for continuous outcomes. The Chi-square (I2) statistic was used to assess heterogeneity at the level of α = 0.10. The I2 statistic greater than 50% and a P < 0.1 were considered statistically significant heterogeneity across included studies.

In cases with a high amount of heterogeneity, the random-effects model was applied to effect sizes, and Tau2 was estimated using Sidik-Jonkman (SJ) estimator due to its better properties in estimating the between-study variance compared to DerSimonian-Laird (DL) method [29,30]. Also, in cases with considerable heterogeneity and a low number of included studies, Hartung-Knapp adjustment was applied to the random-effects model which outperforms the DL method in many cases [31] to provide more robust estimates [32,33]. Otherwise, in cases with homogeneity, the fixed-effect model was applied to effect sizes. Statistical analysis was performed with the R software (Version 3.5, “meta” package) using the random-effects model. Subgroup analysis was carried out based on the type of APCs.

Level of evidence

The GRADE approach (Grading of Recommendation, Assessment, Development, and Evaluation) was used to evaluated the quality of evidence and to determine the level of certainty for the results of the included studies in this meta-analysis [34]. Accordingly, the certainty level was rated as high, moderate, low, and very low.

Results

Study selection

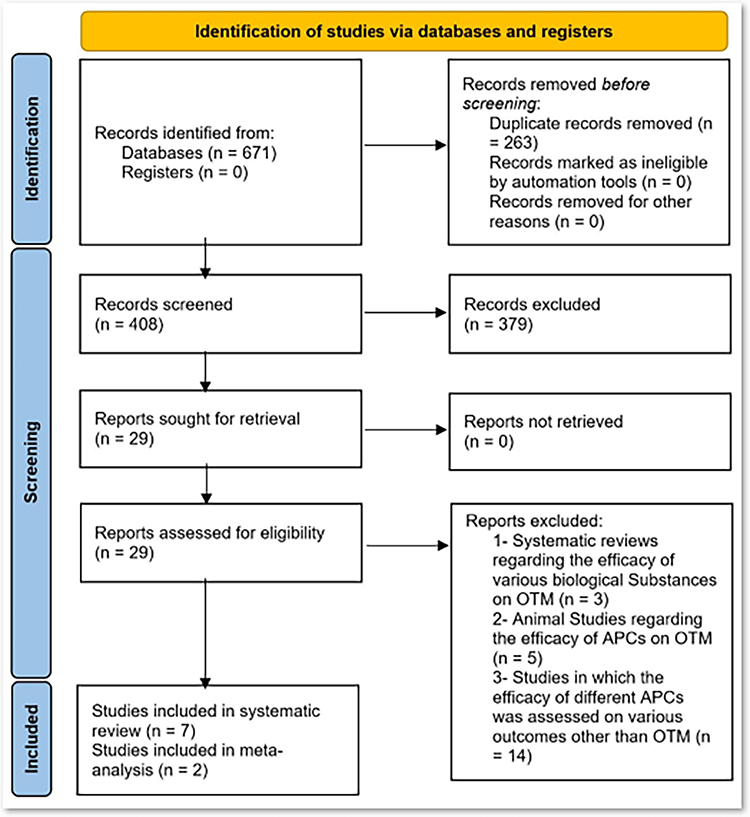

In total, the initial search strategies generated 671 articles. After duplicate removal, 408 abstracts remained for title and abstract evaluation. A total of 379 papers were excluded due to a mismatch with our search criteria and 29 articles were retained for final full text review. Finally, seven RCTs [7,22–27] were included in the qualitative, and two RCTs [22,26] were included in the quantitative analysis (figure 1).

Figure 1:

PRISMA 2020 flow chart.

Study characteristics

Tables II and III present the characteristics of the included studies [7,22–27].

Table II.

Characteristics of included studies, Part 1.

| Study ID | APC Type | Study Design | Number of Participants (Female/Male) |

Mean Age (Range) | Malocclusion | Orthodontic Procedure | Study Groups | Measurement Tool | Treatment Time | Measurement Time | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| El-Timamy et al. (2020) [27] |

PRP | RCT (Split-mouth) | 15 (15/0) | 18 ± 3 (N/A) | N/A | Canine retraction by Ni-Ti closed-coil spring Force = 150 g |

G1(Control Side): 0.25mL CaCl2 10% injection (3 times with a 3-week interval) G2: 0.25mL PRP + 0.25mL CaCl2 (3 times with a 3-week interval) |

Digital ruler (Superimposition of digital casts) | 4 months | 0, 1st, 2nd, 3rd, and 4th months |

PRP > control (1st month) PRP = control (2nd, and 4th month) PRP < Control (3rd month) |

| Karcı and Baka (2021) [7] |

I-PRF | RCT (Split-mouth) | 24 (14/10) | 16.45 ± 0.27 (14–22) | Class II Division I | Extraction of the maxillary first premolars, and canine retraction by Ni-Ti closed-coil spring Force = 150 g |

G1(Control Side): - G2: 2.1mL I-PRF injection (3 times with a 2-week interval) G3 (Control Side): - G4: Piezocision |

Digital ruler (Superimposition of digital casts) | 12 weeks | 0, and 12th weeks | I-PRF = Piezocision > Control Sides |

| Zeitounlouian et al. (2021) [26] |

RCT (Split-mouth) | 21 (15/6) | 20.85 ± 3.85 (N/A) | Class II Division I | Extraction of the maxillary first premolars, and canine retraction by Ni-Ti closed-coil spring Force = 150 g |

G1(Control Side): - G2: 3mL I-PRF injection (2 times with a 1-month interval) | Digital ruler(Occlusograms of stone cast) | 5 months | 0, 1st, 2nd, 3rd, 4th, and 5th months | I-PRF > Control (2nd month) I-PRF = Control (1st, 3rd, 4th, and 5th month) |

|

| Erdur et al. (2021) [22] |

RCT (Split-mouth) | 20 (12/8) | 21.4 ± 2.9 (N/A) | Class II Division I | Extraction of the maxillary first premolars, and canine retraction by Ni-Ti closed-coil spring Force = 150 g |

G1(Control Side): - G2: 4mL I-PRF injection (2 times with a 2-week interval) | Digital caliper (Stone cast) | 3 months | 0, 1st, 4th, 8th, and 12th weeks | I-PRF > Control | |

| Karakasli and Erdur (2020) [23] |

RCT (Full-mouth) | 40 (23/17) | 20.7 ± 1.45 (N/A) | Class II Division I | Extraction of the maxillary first premolars, and canine, and maxillary incisors retraction by Ni-Ti closed-coil spring Force = 150 g |

G1(Control Side): - G2: 4mL I-PRF injection (2 times with a 2-week interval) | Digital caliper (Stone cast) | 4 weeks | 0, 1st, 2nd, 3rd, and 4th weeks | I-PRF > Control | |

| Pacheco et al. (2020) [24] |

L-PRF | RCT (Split-mouth) | 21 (N/A) | 33 ± 5.9 (N/A) | Class I, and Class II Division I | Extraction of the maxillary first premolars, and canine retraction by an elastic chain Force = 150 g |

G1(Control Side): - G2: L-PRF placed in the socket | Flexible ruler (Intraoral) | 5 months | 0, 1st, 2nd, 3rd, 4th, and 5th months | L-PRF < Control |

| Tehranchi et al. (2018) [25] |

RCT (Split-mouth) | 8 (3/5) | 17.37 (12–25) | N/A | Extraction of first premolars of each jaw, and canine retraction by Ni-Ti closed-coil spring Force = 150 g |

G1(Control Side): - G2: L-PRF placed in the socket | Digital caliper (Stone cast) | 4 months | 0, 2nd, 4th, 6th, 8th, 10th, 12th, 14th, and 16th weeks | L-PRF > Control |

Table III.

Characteristics of included studies, Part 2.

| Study ID | APC Type | Blood Sample | Preparation Method | Injection Method | Injection/Placement Site | Whole Injection Volume | Injection Interval |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| El-Timamy et al. (2020) [27] |

PRP | 5 mL blood sample with anticoagulant + 10% CaCl2 and thrombin | Double spin technique | Intraligamental injection | Middle, distobuccal, and distopalatal areas of the distal surface of the canines | 0.25mL | 0, 3th, and 6th week |

| Submucosal injection | Buccal and palatal surface of canine | ||||||

| Karcı and Baka (2021) [7] |

I-PRF | 9mL without anticoagulant | 800 rpm 3 min N/A (N/A) | Submucosal injection | Buccal, palatal, and distal surface of canine | 2.1mL | 0, 4th, and 8th week |

| Zeitounlouian et al. (2021) [26] |

20mL with anticoagulant | 700 rpm 3 min N/A (N/A) | Submucosal injection | Buccal and palatal surface of canine | 3mL | 0, and 1st month | |

| Erdur et al. (2021) [22] |

10mL without anticoagulant | 700 rpm 3 min Room temperature (Duo Centrifuge, Nice, France) | Intraligamental injection | Distobuccal and distopalatal surface of canine | 4mL | 0, and 2nd week | |

| Karakasli and Erdur (2020) [23] |

10mL without anticoagulant | 700 rpm 3 min Room temperature (Duo Centrifuge, Nice, France) | Intraligamental injection | N/A | 2–3mL | 0, and 2nd week | |

| Pacheco et al. (2020) [24] |

L-PRF | N/A | 2700 rpm 14 min N/A (IntraSpin Centrifuge, Florida, USA) |

N/A | Socket | N/A | Before orthodontic force application |

| Tehranchi et al. (2018) [25] |

N/A | 2700 rpm 12 min N/A (PC-02, Nice, France) | N/A | Socket | N/A | Before orthodontic force application |

Out of seven studies, PRP was used in only one study [27], while I-PRF was used in four studies [7,22,23,26], and L-PRF was applied in two studies [24,25].

All of the included studies were RCTs [7,22–27]. Six studies were split-mouth designs [7,22,24–27], whereas only one study was a full-mouth design [23]. In all the studies, both male and female subjects were included [7,22,24–26] except for one study in which only female patients were involved [27].

The mean age of the included subjects ranged between 16.45 to 33 years old [7,22–27]. Class II division I malocclusion was mostly used as a required inclusion criterion for subjects [7,22–24,26].

Out of seven studies, two studies used L-PRF inside the extracted socket of the first premolars [24,25].

L-PRF was only applied once during the whole treatment time [24,25].

On the other hand, in five studies, APCs were used as an injectable biomaterial [7,22,23,26,27]. Out of these five studies, four studies used I-PRF [7,22,23,26], whereas only one study administrated PRP [27] Regarding I-PRF administration, one study administered 2.1mL of I-PRF three times with a two-week interval [7]; two studies used 4mL of I-PRF two times with a two-week interval [22,23]; whereas, in another study, 3mL of I-PRF was injected twice with a one-month interval [26]. Moreover, regarding PRP administration, 0.25mL PRP in addition to 0.25mL CaCl2 was injected three times with a three-week interval [27]. All of the aforementioned studies had no placebo group except the last study in which 0.25mL CaCl2 injection was used as the placebo intervention [27].

The rate of tooth movement was measured in maxillary and mandibular anterior teeth (canines and incisors) [7,22–27].

Ni-Ti closed-coil springs [7,22,23,25–27] and elastomeric chains [24] were used for canine and incisor retraction. In all of the included studies, 150 g of force was used to initiate the space closure procedure [7,22–27].

Different observational periods (4 months for PRP, 4 weeks to 5 months for I-PRF, and 4 to 5 months for L-PRF) were used for assessing the outcomes of various types of APCs on OTM. Overall, the duration of the aforementioned orthodontic treatments varied between 4 weeks to 5 months [7,22–27].

On this basis, the rate of tooth movement was assessed through stone casts [22,23,25], digital casts superimposition [7,27], occlusograms [26], and direct clinical assessments [24]. Table IV illustrates the type and the rate of OTM in mm per interval mentioned in each included RCTs.

Table IV.

The type and the rate of OTM in mm per interval mentioned in each included RCTs.

| Study ID | APC Type | Type of Tooth Movement | Measurement Time | Rate of Orthodontic Tooth Movement | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Experimental Group | Control Group | ||||||

| Mean (mm) | SD (mm) | Mean (mm) | SD (mm) | ||||

| El-Timamy et al. (2020) [27] |

PRP | Canine Retraction | 1st month | 1.55 | 0.63 | 1.35 | 0.62 |

| 2nd month | 1.33 | 0.87 | 1.27 | 0.40 | |||

| 3rd month | 0.59 | 0.96 | 1.01 | 0.63 | |||

| 4th month | 1.10 | 0.58 | 0.90 | 0.50 | |||

| Karcı and Baka (2021) [7] |

I-PRF |

Canine Retraction | 12th week | 2.83 | 0.21 | 2.04 | 0.22 |

| Zeitounlouian et al. (2021) [26] |

Canine Retraction | 1st month | 0.92 | 0.56 | 1.25 | 0.99 | |

| 2nd month | 1.40 | 0.83 | 0.97 | 0.61 | |||

| 3rd month | 1.46 | 0.56 | 1.13 | 0.60 | |||

| 4th month | 1.14 | 0.87 | 0.86 | 0.71 | |||

| 5th month | 0.68 | 0.55 | 1.23 | 0.31 | |||

| Erdur et al. (2021) [22] |

Canine Retraction | 1st week | 0.73 | 0.11 | 0.35 | 0.08 | |

| 4th week | 1.56 | 0.08 | 1.08 | 0.1 | |||

| 8th week | 1.90 | 0.1 | 1.23 | 0.12 | |||

| 12th week | 1.88 | 0.11 | 1.23 | 0.13 | |||

| Karakasli and Erdur (2020) [23] |

Incisor Retraction | 1st week | 0.136 1 | 0.032 1 | 0.081 1 | 0.018 1 | |

| 0.138 2 | 0.036 2 | 0.079 2 | 0.033 2 | ||||

| 4th week | 0.105 1 | 0.026 1 | 0.077 1 | 0.024 1 | |||

| 0.098 2 | 0.026 2 | 0.070 2 | 0.015 2 | ||||

| Pacheco et al. (2020) [24] |

L-PRF | Canine Retraction | 1st month | 0.668 3 | N/A 3 | 0.909 3 | N/A 3 |

| 2nd month | |||||||

| 3rd month | |||||||

| 4th month | |||||||

| 5th month | |||||||

| Tehranchi et al. (2018) [25] |

Canine Retraction | 2nd week | 6.65 3 | 0.834 3 | 6.76 3 | 0.763 3 | |

| 4th week | |||||||

| 6th week | |||||||

| 8th week | |||||||

| 10th week | |||||||

| 12th week | |||||||

| 14th week | |||||||

| 16th week | |||||||

The reported measurements of incisor retraction on the right side of the maxillary arch.

The reported measurements of incisor retraction on the left side of the maxillary arch.

The mean and SD of the total rate of canine retraction were reported instead of each interval.

Risk of bias within studies

The risk of bias of included studies that were assessed by the modified JADAD scale is illustrated in table V. Two studies had high [26,27], three had moderate [7,23,24], and two had [22,25] low overall quality. The method of blinding was not appropriate in most studies [7,22–25].

Table V.

Quality assessment of the included studies by the modified JADAD scale.

| Modified JADAD Scale | El-Timamy et al. (2020) [27] |

Karcı and Baka (2021) [7] |

Zeitounlouian et al. (2021) [26] |

Erdur et al. (2021) [22] |

Karakasli et al. (2020) [23] |

Pacheco et al. (2020) [24] |

Tehranchi et al. (2018) [25] |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Randomization | Was the study described as randomized? | +1 | +1 | +1 | +1 | +1 | +1 | +1 |

| Was the randomization described and appropriate? | +1 | +1 | +1 | +1 | +1 | +1 | +1 | |

| Blinding | Was the study described as blinded? | +1 | 0 | +0.5 | −1 | 0 | 0 | −1 |

| Was the method of blinding appropriate? | +1 | 0 | +1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| An account of all patients | Was there a description of withdrawals and drop outs? | +1 | +1 | +1 | 0 | +1 | +1 | +1 |

| Was there a description of the inclusion/exclusion criteria? | +1 | +1 | +1 | +1 | +1 | +1 | +1 | |

| Was the method used to assess adverse effects described? | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Was the method of statistical analysis described? | +1 | +1 | +1 | +1 | +1 | +1 | +1 | |

| Result | 7 | 5 | 6.5 | 3 | 5 | 5 | 4 | |

| Quality of study | High | Moderate | High | Low | Moderate | Moderate | Low | |

Results of individual studies

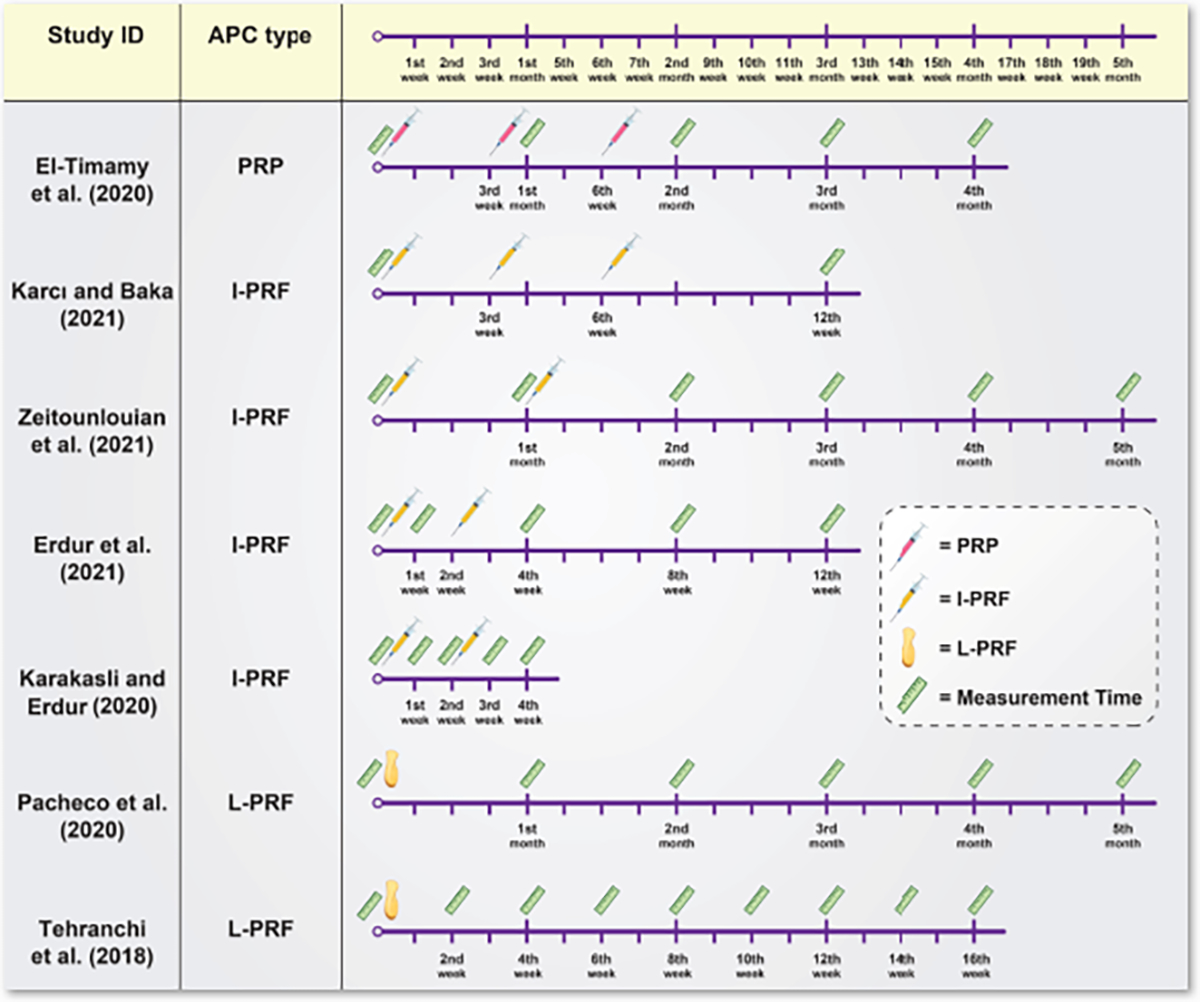

Figure 2 illustrates a schematic timeline of each included study in which the intervals of APC administration and the measurement time of OTM are reported. The last column of table II briefly describes the clinical efficacy of administrating APCs in all included studies [7,22–27]. The efficacy of these APCs on OTM varied among different studies.

Figure 2:

Schematic timeline of each included study in which the intervals of APC administration and the measurement time of OTM are reported.

On this basis, only one study has evaluated the effect of intraligamental and submucosal injection of PRP on accelerating canine tooth movements [27]. It was demonstrated that PRP has significantly accelerated the rate of canine retraction when injected in the first months in comparison to the control side. However, the rate of canine retraction was significantly greater on the control side in the third month, and there were no significant differences in both 2nd and 4th months among the interventional and control groups [27].

On the other hand, four studies have assessed the efficacy of I-PRF on OT [7,22,23,26]. Despite the different observation periods, intraligamental and submucosal administration of I-PRF was found to have a significantly increased effect on the rate of OTM in three studies [7,22,23]. In the other study, submucosal injection of I-PRF has significantly accelerated the rate of canine retraction only in the second month [26]. On the other hand, two studies have evaluated the effect of L-PRF placement in the extraction socket of first premolars on the rate of tooth movement. L-PRF has led to both significantly less [24] and more [25] canine retraction rates compared to the control sides.

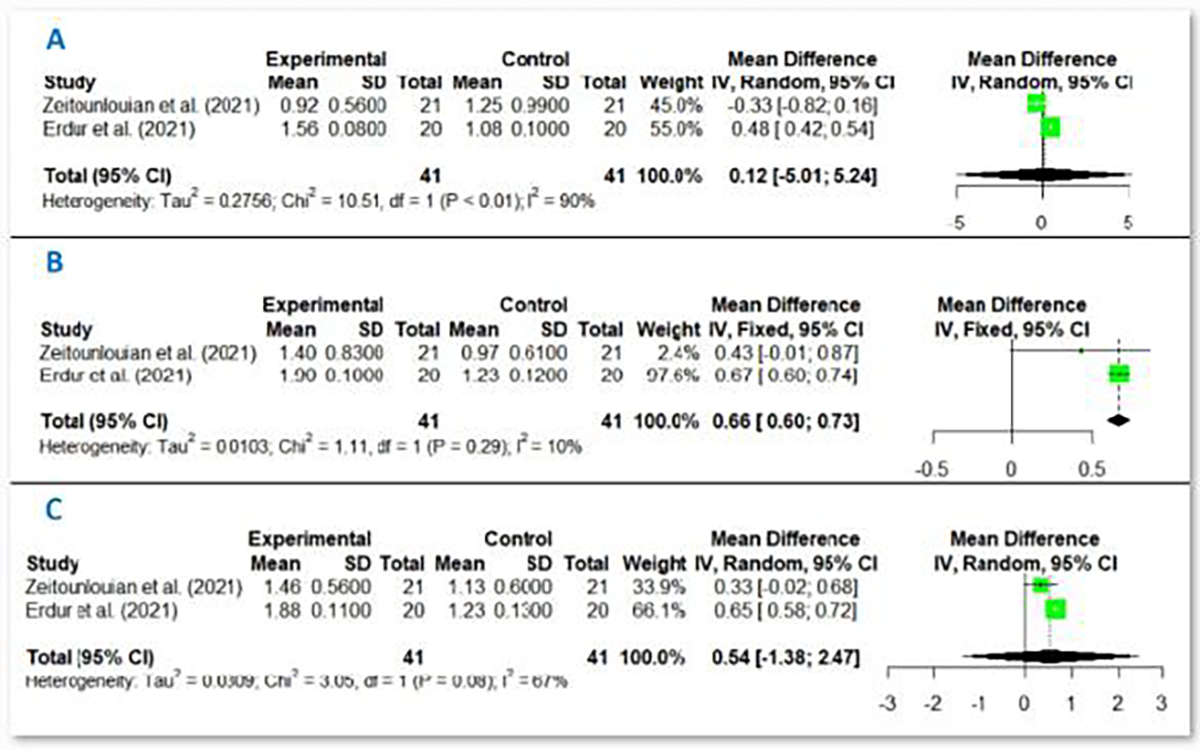

Results of meta-analysis

Finally, only two RCTs with 41 participants (82 sides) in the I-PRF group have met the eligibility criteria to be included in this meta-analysis [22,26]. In this regard, meta-analysis was performed regarding the effect of I-PRF on the rate of canine tooth movement in millimeters at different intervals of first, second, and third months.

In the 1st month, I-PRF (WMD:0.12mm, CI95% −5.01 to 5.24, I2=90%) did not significantly affect OTM with very low certainty of evidence (Supplementary Table II).

In the 2nd month, I-PRF significantly increased the OTM (WMD:0.66mm, CI95% 0.60 to 0.73, I2=10%), and the certainty of the evidence was scored as low (Supplementary Table II).

However, in the 3rd month, I-PRF did not significantly increase the OTM (WMD:0.54mm, CI95% −1.38 to 2.47, I2=67%) with very low certainty of evidence (Supplementary Table II), (figures 3a, 3b, and 3c).

Figure 3:

Forest plot of the adjunct effect of I-PRF on OTM in a) 1st month b) 2nd month c) 3rd month.

Discussion

OTM has been defined as “the result of a biologic response to interference in the physiologic equilibrium of the dentofacial complex by an externally applied force” [35]. The process of OTM has been extensively investigated in terms of molecular-, cellular-, and tissue-based reactions [36]. Numerous factors, unaccompanied or in combination, might have an effect on remodelling activities and eventually tooth displacement, and the changes in bone turnover and density may alter the rate of tooth movement [36]. Apparently, many biological substances may play a role in altering the inflammatory process and bone remodeling pathways accompanying OTM [36]. On this basis, the use of APCs, as useful biological substances that release a wide variety of growth factors and cytokines, has caught extreme attention in the acceleration of oral and maxillofacial tissues regeneration [14,37]. Accordingly, several animal studies have been conducted to evaluate the adjunctive effect of different APCs on OTM [1,38]. A recently published systematic review by Li et al. [38] gathered current evidence available from animal studies pertaining to the effectiveness of PRP in accelerating OTM. Overall, five animal studies were included in this systematic review. Three of them found a positive correlation between PRP administration and acceleration of OTM, along with corresponding histological changes. However, the other two studies demonstrated no significant difference in the rate of OTM after PRP administration. They have concluded that based on the currently limited evidence, the efficacy of PRP on the acceleration of OTM remains controversial [38]. Besides, it is worth mentioning that it is not prudent to merely rely on the information derived from animal experiments to interpret the clinical outcomes [1]. Hence, this systematic review and meta-analysis evaluated the current RCTs to find out whether locally administered APCs such as PRP, I-PRF, and L-PRF can significantly accelerate OTM in humans.

Based on the qualitative synthesis of the collected studies, inconsistent effects on the rate of tooth movement were detected between different APCs, with PRP showing overall no influence [27], I-PRF presenting overall positive effects [7,22,23,26], and L-PRF demonstrating contradictory negative and positive influences [24,25]. These dissimilarities in the outcomes can be attributed to several factors including the insufficient number of studies conducted on each APC, differences in age and sex ratios, limited number of participants, and different methods of assessing the OTM. Moreover, non-negligible risk of bias in some studies, the different observational periods, and frequencies of application for the APCs, as well as their various amounts and different delivery methods, should also be concerned.

Regardless of these factors, it was demonstrated that the sequential administration of PRP did not significantly affect the rate of canine retraction compared to the control group over four months (P = 0.895) [27]. The rate of canine retraction was faster on the intervention side in the first 2 months, with a statistically significant difference in the first month (P = 0.049). On the other hand, the rate was statistically significantly slower on the intervention side in the third month following cessation of PRP injections (P = 0.02). A plausible explanation for this observation might be the negative feedback mechanism in growth factor secretion as the same as the hormonal negative feedback that occurs in association with increased blood and/or tissue concentration [39,40]. Consequently, due to the local increase in the growth factors concentrations in the tissues adjacent to the teeth following the PRP injection, the normal growth factor release of the tissues could have been inhibited during OTM [27]. Additionally, Fernandez-Medina et al. [41] reported that high concentrations of PRP (≥60%) have detrimental effects on the viability and migration of osteoblasts, which could be considered as an aspect of the decreased rate of OTM in the third month. Furthermore, the increased amount of thrombin in PRP may produce a toxic effect on surrounding tissues; therefore, decreasing the rate of OTM [7]. It is also worth mentioning that the dissimilarities in the methods of PRP preparation, the different delivery methods, and the amount of PRP administration in various clinical studies make it difficult to compare its outcomes [42]. Given that the growth factors contained in PRP are released very quickly, another challenge in using PRP is to maintain its biologically active state for a long time, which is mainly dependent on the leukocyte concentration and its form of application [7,42,43]. Subsequently, several studies have focused on PRF, especially its injectable form (I-PRF), due to the slow release of growth factors over a long period of time in promoting OTM [7,22,23,26]. Moreover, numerous studies have assessed the adjunctive effect of I-PRF on OTM of canines over different observational periods (i.e., 12 weeks [7], 3 months [22], and 5 months [26]). In this regard, I-PRF has notably shown promising results on accelerating OTM of canines in almost all periods [7,22], except for the study by Zeitounlouian et al. [26] in which I-PRF significantly increased canine tooth movement in only the 2nd month (P = 0.018). Moreover, the adjunctive effect of I-PRF on OTM of incisors was also measured by Karakasli and Erdur [23] over a period of four weeks. They administered I-PRF two times with an interval of 2 weeks from the beginning of the study. The average movements of incisors were significantly higher in the study group compared to the control group at all time points (P < 0.05). Hence, they found that administration of I-PRF can also significantly increase the rate of maxillary incisor retraction [23]. Similar to other forms of APCs, I-PRF is an easily obtainable, low-cost biomaterial with the least possible complications [23]. This biomaterial is obtained by decreasing the rate of the centrifugation speed that allows I-PRF to contain and release more growth factors and cytokines from its fibrin network [44,45]. In addition, the prolonged release of bioactive molecules from I-PRF makes it a resourceful biomaterial for clinical utilization [44]. Another applicable form of PRF is used as a solid scaffold. On this basis, L-PRF as a powerful scaffold with an integrated reservoir of several growth factors and cytokines has also been utilized for tissue regeneration [1,46]. To evaluate the effectiveness of L-PRF on the rate of canine retraction, Tehranchi et al. [25] observed a profound decrease in distance between the mid-marginal points of the maxillary and mandibular teeth adjacent to the extracted socket by placing the L-PRF in the extracted socket of the first premolar. More recently, Pacheco et al. [24] did the same experiment on the extraction sockets of the maxillary first premolars in patients with Class I or Class II division 1 malocclusion undergoing canine retraction. However, they demonstrated that L-PRF could result in a slower canine retraction rate which was in contrast to the results of the previous study [25]. This phenomenon could be explained by the effect of the transforming growth factor beta (TGF-β) in L-PRF, leading to the proliferation of the osteoblasts and synthesis of collagen and osteoprotegerin and, accordingly, inducing bone regeneration [47,48]. Moreover, TGF-β is capable of downregulating osteoclasts’ activity and avoiding bone resorption, which is essential for OTM to occur [24,48]. Therefore, the concentrated amount of TGF-β can be one of the possible reasons to better justify the decreased rate of OTM in the presence of L-PRF in the extracted socket [24]. Besides, in the study of Tehranchi et al. [25], the small sample size (8 patients between the ages of 12 and 25 years) and the variable selection of teeth (maxillary and mandibular) may have affected the outcome and limited the clinical significance. Furthermore, to avoid the unintended influence of age variability, Pacheco et al. [24] have only included young patients which can also ascertain a better response of periodontium to orthodontic forces. Moreover, to avoid any bias regarding the variations in site of receiving the treatment (maxillary and mandibular alveoli), maxillary alveoli were solely evaluated and grafted in their study [24]. Additionally, since this study has been performed on a larger sample size (almost twice), and the extracted sites were grafted with bigger amounts of L-PRF than those described by Tehranchi et al. [25], by weighing up the results, it seems that the adjunctive application of L-PRF together with orthodontic treatment should be reconsidered and reevaluated.

On the other hand, based on quantitative data synthesis, studies that only had reported means and standard deviations values regarding OTM of anterior teeth in different time points were included in the meta-analysis. In this regard, all PRP-related [27] and L-PRF-related [24,25], and some I-PRF-related studies [7,23] were excluded from further analysis since they did not report any of the aforementioned information. Finally, the adjunctive effect of I-PRF [22,26] was analyzed on the rate of canine tooth movement in millimeters at different intervals of first, second, and third months.

In the first month, I-PRF did not cause any statistically significant acceleration on OTM. The failure to affect OTM in the first month could be ascribed to the fact that the injected amount of I-PRF in the adjacent tissues are not enough to release sufficient concentrations of growth factors and cytokines to promote OTM. Despite the fact that I-PRF is able to be hydrolyzed in a few days, the physiologic polymerization of these biomaterials allows the growth factors and cytokines to be stored and then slowly released over a long period of time [26,49]. Therefore, it seems that one month is a very short time for this biomaterial to influence OTM. Besides, a higher percentage of heterogeneity (I2=90%) was also found among those studies in which the effect of I-PRF on OTM was assessed. This could be due to different amounts and numbers of I-PRF injections at different intervals in those studies [22,26]. Additionally, the differences between submucosal and intraligamental injection might have been effective in the yielded results.

In the second month, I-PRF significantly increased the OTM, and the percentage of heterogeneity becomes extremely lessened (I2=10%) in comparison to the first month. This acceleration and low heterogeneity among these studies might be explained by a cumulative effect of the multiple I-PRF boost injections performed at previous intervals which could temporarily increase the concentrations of growth factors and cytokines for enhancing OTM [26]. This finding reveals that the boost injections of I-PRF might be necessary on a monthly, or other timely bases, to reach a sustained and faster OTM [26]. However, the timing of the boost injections must be chosen with caution since the degradation, and the injection site of I-PRF may play an imperative role in this regard. Erdur et al. [22] performed intraligamentary injections of I-PRF at the beginning of the study and the second week to assess the canine retraction rate. They found significant outcomes until the 12th week [22]. Given the fact that I-PRF generally degrades during a 2-week period [50,51], it seems that the site of injection and the affected cells by this injection may be an important issue while considering the injection intervals. Additionally, since the periodontium is a key part in mediating OTM [52], it seems that the intraligamentary injection of I-PRF can have a more significant and long-lasting effect than submucosal injections. Considering the effect of submucosal injection of I-PRF, Zeitounlouian et al. [26], have shown that, during a 5-month period, by two submucoal injections at the beginning of the study and the 1st month, only the second month measurements were statistically significant. It can be postulated that submucosal injections can not be as effective as intraligamentray injections; hence, they may need shorter injection intervals. Based on the current literature, it seems the approach of Erdur et al. [22] may be the optimized methods of applying boost injections with the most long-lasting significant outcomes.

Finally, in the third month unlike to the second month, the administration of I-PRF did not significantly increase the rate OTM. On this basis, the amount of OTM decreased slightly in comparison to the previous month. This decrease could be related to the fact that the remnant amount of I-PRF has been reduced in the adjacent tissues, and the injection was not continuous in the third month. It seems that the administration of boost injections at timely intervals based on the degradation rate, and the injection site of I-PRF might be able to increase the amount of tooth movement. Besides, the rate of heterogeneity (I2=67%) among studies in which the effect of I-PRF on the OTM was assessed was also elevated. This elevation could be ascribed to different remnants of I-PRF in adjacent tissues since these two studies [22,26] administrated different amounts and numbers of I-PRF injections at different intervals. In this regard, different injection methods (submucosal and intraligamental) might influence the residual amounts of I-PRF in the tissues adjacent to teeth.

Based on the current meta-analysis, the administration of I-PRF seems to have the most significant effect on the OTM of canines in the second month. Nevertheless, the clinical significance and applicability of this biomaterial must be carefully weighed based on whether the statistically significant results would lead to clinically significant outcomes. Clinically, “the typical rate of OTM depends on magnitude and duration of force applied, number and shape of roots, quality of bony trabeculae, individual response, and patient compliance” [53]. Based on the above-mentioned factors, the rate of biological OTM with optimum mechanical force could be varied between 1.0 to 1.5 mm in 4 to 5 weeks [53,54]. In this regard, the results of the meta-analysis demonstrated that the administration of I-PRF increases the OTM of canines in second (0.65 mm) and third (0.54 mm) months compared to negative control groups. Since, in cases of maximum anchorage premolar extraction, the canine retraction phase usually takes about 6 to 9 months (with an average of 2 years) [53], it seems that this amount of OTMs would effectively decrease the overall orthodontic treatment time. As mentioned earlier, the application of biological substances can be considered as alternatives to surgically-assisted OTM since they cause fewer complications and leave the patient with less discomfort. This can be further validated by considering the positive effect of I-PRF on OTM. Concerning the comparative effect of I-PRF versus surgically-assisted OTM, according to the study by Karcı and Baka [7], the injection of I-PRF and the utilization of piezocision can both significantly accelerate the rate of OTM, while there is no superiority between these two methods. However, further well-designed RCTs with larger samples and more standardized parameters (e.g., a totally blinded setting, split-mouth design, different patient groups, placebo injections, and comparisons of different types of APCs at various intervals) are recommended to assess the adjunctive effects of APCs on OTM in a long period of time.

It is crucial to note that the results of this meta-analysis should be interpreted with caution because the number of included RCTs in the analysis was small and the heterogeneity among studies was high in some cases. In addition, the level of quality and certainty of the studies included in this meta-analysis was low. The other limitations of this study were the small sample sizes of each included RCTs and the methodological differences between the studies, which have led to some inconsistent results between the meta-analysis and the results yielded by each included RCT. Nonetheless, the random effects were applied in cases with high percentages of heterogeneity to increase the precision of the results. Additionally, the overall quality of the majority of the included RCTs was moderate.

Conclusions

According to the low certainty of the evidence, a definite conclusion may not be reached currently. Nevertheless, based on both qualitative and quantitative results, it seems that performing intraligamentary injection of I-PRF, as an easy and minimally invasive technique, might be potentially considered as an adjunctive in accelerating OTM of the canines. However, further high-quality studies with improved methodology and larger sample sizes are required to validate the efficacy of APCs in improving OTM. Additionally, the current evidence suggests the potential effect of boost injection of APCs to maintain the enhanced rate of OTM. In order to determine the optimal intervals of boost injections, the type and degradation rate of APCs, and their injection/application sites should be highly considered for the future investigations.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgement:

Part of the research reported in this paper was supported by National Institute of Dental & Craniofacial Research of the National Institutes of Health under award number R15DE027533, 1 R56 DE029191-01A1, and 3R15DE027533-01A1W1.

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Conflict of interests: None.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- [1].Arqub SA, Gandhi V, Iverson MG, Ahmed M, Kuo CL, Mu J, et al. The effect of the local administration of biological substances on the rate of orthodontic tooth movement: a systematic review of human studies. Prog Orthod 2021;22:1–12. 10.1186/s40510-021-00349-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Meikle MC. The tissue, cellular, and molecular regulation of orthodontic tooth movement: 100 Years after Carl Sandstedt. Eur J Orthod 2006;28:221–40. 10.1093/ejo/cjl001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Singh A, Gill G, Kaur H, Amhmed M, Jakhu H. Role of osteopontin in bone remodeling and orthodontic tooth movement: a review. Prog Orthod 2018;19:1–8. 10.1186/s40510-018-0216-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Francisco I, Fernandes MH, Vale F. Platelet-rich fibrin in bone regenerative strategies in orthodontics: A systematic review. Materials (Basel) 2020;13:1866. 10.3390/MA13081866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Asiry MA. Biological aspects of orthodontic tooth movement: A review of literature. Saudi J Biol Sci 2018;25:1027–32. 10.1016/j.sjbs.2018.03.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Wishney M Potential risks of orthodontic therapy: a critical review and conceptual framework. Aust Dent J 2017;62:86–96. 10.1111/adj.12486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Çağlı Karcı İ, Baka ZM. Assessment of the effects of local platelet-rich fibrin injection and piezocision on orthodontic tooth movement during canine distalization. Am J Orthod Dentofac Orthop 2021. 10.1016/j.ajodo.2020.03.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Murphy KG, Wilcko MT, Wilcko WM, Ferguson DJ. Periodontal Accelerated Osteogenic Orthodontics: A Description of the Surgical Technique. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2009;67:2160–6. 10.1016/j.joms.2009.04.124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Frost HM. The regional acceleratory phenomenon: A review. Henry Ford Hosp Med J 1983;31:3–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Al-Naoum F, Hajeer MY, Al-Jundi A. Does alveolar corticotomy accelerate orthodontic tooth movement when retracting upper canines? A split-mouth design randomized controlled trial. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2014;72:1880–9. 10.1016/j.joms.2014.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Lee W Corticotomy for orthodontic tooth movement. J Korean Assoc Oral Maxillofac Surg 2018;44:251–8. 10.5125/jkaoms.2018.44.6.251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Li Z, Zhou J, Chen S. The effectiveness of locally injected platelet-rich plasma on orthodontic tooth movement acceleration: Angle Orthod 2021;91:391–8. 10.2319/061320-544.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Chou TM, Chang HP, Wang JC. Autologous platelet concentrates in maxillofacial regenerative therapy. Kaohsiung J Med Sci 2020;36:305–10. 10.1002/kjm2.12192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Amiri MA, Farshidfar N, Hamedani S. The prospective relevance of autologous platelet concentrates for the treatment of oral mucositis. Oral Oncol 2021;122:105549. 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2021.105549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Dohan Ehrenfest DM, Rasmusson L, Albrektsson T. Classification of platelet concentrates: from pure platelet-rich plasma (P-PRP) to leucocyte- and platelet-rich fibrin (L-PRF). Trends Biotechnol 2009;27:158–67. 10.1016/j.tibtech.2008.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Feng M, Wang Y, Zhang P, Zhao Q, Yu S, Shen K, et al. Antibacterial effects of platelet-rich fibrin produced by horizontal centrifugation. Int J Oral Sci 2020;12:32. 10.1038/s41368-020-00099-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Kargarpour Z, Nasirzade J, Panahipour L, Miron RJ, Gruber R. Liquid PRF Reduces the Inflammatory Response and Osteoclastogenesis in Murine Macrophages. Front Immunol 2021;12. 10.3389/fimmu.2021.636427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Mijiritsky E, Assaf HD, Peleg O, Shacham M, Cerroni L, Mangani L. Use of PRP, PRF and CGF in periodontal regeneration and facial rejuvenation-a narrative review. Biology (Basel) 2021;10:317. 10.3390/biology10040317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Metlerska J, Fagogeni I, Nowicka A. Efficacy of Autologous Platelet Concentrates in Regenerative Endodontic Treatment: A Systematic Review of Human Studies. J Endod 2019;45:20–30.e1. 10.1016/j.joen.2018.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Ding Z-Y, Tan Y, Peng Q, Zuo J, Li N. Novel applications of platelet concentrates in tissue regeneration (Review). Exp Ther Med 2021;21:1. 10.3892/etm.2021.9657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Jasmine S, Thangavelu A, Krishnamoorthy R, Alshatwi AA. Platelet Concentrates as Biomaterials in Tissue Engineering: a Review. Regen Eng Transl Med 2020:1–13. 10.1007/s40883-020-00165-z.33816776 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Erdur EA, Karakaslı K, Oncu E, Ozturk B, Hakkı S. Effect of injectable platelet-rich fibrin (i-PRF) on the rate of tooth movement: Angle Orthod 2021;91:285–92. 10.2319/060320-508.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Karakasli K, Erdur EA. The effect of platelet-rich fibrin (PRF) on maxillary incisor retraction rate. Angle Orthod 2021;91:213–9. 10.2319/050820-412.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Reyes Pacheco AA, Collins JR, Contreras N, Lantigua A, Pithon MM, Tanaka OM. Distalization rate of maxillary canines in an alveolus filled with leukocyte-platelet–rich fibrin in adults: A randomized controlled clinical split-mouth trial. Am J Orthod Dentofac Orthop 2020;158:182–91. 10.1016/j.ajodo.2020.03.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Tehranchi A, Behnia H, Pourdanesh F, Behnia P, Pinto N, Younessian F. The effect of autologous leukocyte platelet rich fibrin on the rate of orthodontic tooth movement: A prospective randomized clinical trial. Eur J Dent 2018;12:350–7. 10.4103/ejd.ejd_424_17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Zeitounlouian TS, Zeno KG, Brad BA, Haddad RA. Effect of injectable platelet-rich fibrin (i-PRF) in accelerating orthodontic tooth movement: A randomized split-mouth-controlled trial. J Orofac Orthop 2021:1–9. 10.1007/s00056-020-00275-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].El-Timamy A, El Sharaby F, Eid F, El Dakroury A, Mostafa Y, Shaker O. Effect of platelet-rich plasma on the rate of orthodontic tooth movement: A split-mouth randomized trial. Angle Orthod 2020;90:354–61. 10.2319/072119-483.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Page MJ, Moher D, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. PRISMA 2020 explanation and elaboration: Updated guidance and exemplars for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021;372. 10.1136/bmj.n160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Sidik K, Jonkman JN. A comparison of heterogeneity variance estimators in combining results of studies. Stat Med 2007;26:1964–81. 10.1002/sim.2688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Viechtbauer W. Bias and efficiency of meta-analytic variance estimators in the random-effects model. J Educ Behav Stat 2005;30:261–93. 10.3102/10769986030003261. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Inthout J, Ioannidis JP, Borm GF. The Hartung-Knapp-Sidik-Jonkman method for random effects meta-analysis is straightforward and considerably outperforms the standard DerSimonian-Laird method. BMC Med Res Methodol 2014;14. 10.1186/1471-2288-14-25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Hartung J, Knapp G. On tests of the overall treatment effect in meta-analysis with normally distributed responses. Stat Med 2001;20:1771–82. 10.1002/sim.791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Hartung J An alternative method for meta-analysis. Biometrical J 1999;41:901–16. . [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Schünemann H, Brożek J, Guyatt G, Oxman A E. GRADE handbook for grading quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. Updated October 2013. The GRADE Working Group, 2013. Available from Guidel Org/Handb 2013. [Google Scholar]

- [35].Proffit WR, Fields HW, Larson B, Sarver DM. Contemporary orthodontics-e-book. Elsevier Health Sciences; 2018: 744 pages. [Google Scholar]

- [36].Krishnan V, Davidovitch Z. Cellular, molecular, and tissue-level reactions to orthodontic force. Am J Orthod Dentofac Orthop 2006;129:469.e1–469.e32. 10.1016/j.ajodo.2005.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Amiri MA, Farshidfar N, Hamedani S. The potential application of platelet-rich fibrin (PRF) in vestibuloplasty. Maxillofac Plast Reconstr Surg 2021;43:1–2. 10.1186/s40902-021-00308-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Li Z, Zhou J, Chen S. The effectiveness of locally injected platelet-rich plasma on orthodontic tooth movement acceleration: A systematic review of animal studies. Angle Orthod 2021;91:391–8. 10.2319/061320-544.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Shah P, Keppler L, Rutkowski J. A review of platelet derived growth factor playing pivotal role in bone regeneration. J Oral Implantol 2014;40:330–40. 10.1563/AAID-JOI-D-11-00173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Vassbotn FS, Havnen OK, Heldin CH, Holmsen H. Negative feedback regulation of human platelets via autocrine activation of the platelet-derived growth factor α-receptor. J Biol Chem 1994;269:13874–9. 10.1016/s0021-9258(17)36728-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Fernández-Medina T, Vaquette C, Ivanovski S. Systematic comparison of the effect of four clinical-grade platelet rich hemoderivatives on osteoblast behaviour. Int J Mol Sci 2019;20:6243. 10.3390/ijms20246243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Rodriguez IA, Growney Kalaf EA, Bowlin GL, Sell SA. Platelet-rich plasma in bone regeneration: Engineering the delivery for improved clinical efficacy. Biomed Res Int 2014;2014. 10.1155/2014/392398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Anitua E, Zalduendo M, Troya M, Padilla S, Orive G. Leukocyte inclusion within a platelet rich plasma-derived fibrin scaffold stimulates a more pro-inflammatory environment and alters fibrin properties. PLoS One 2015;10:e0121713. 10.1371/journal.pone.0121713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Wang X, Zhang Y, Choukroun J, Ghanaati S, Miron RJ. Effects of an injectable platelet-rich fibrin on osteoblast behavior and bone tissue formation in comparison to platelet-rich plasma. Platelets 2018;29:48–55. 10.1080/09537104.2017.1293807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Dohan DM, Choukroun J, Diss A, Dohan SL, Dohan AJJ, Mouhyi J, et al. Platelet-rich fibrin (PRF): A second-generation platelet concentrate. Part I: Technological concepts and evolution. Oral Surgery, Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endodontology 2006;101:e37–44. 10.1016/j.tripleo.2005.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Kang YH, Jeon SH, Park JY, Chung JH, Choung YH, Choung HW, et al. Platelet-rich fibrin is a bioscaffold and reservoir of growth factors for tissue regeneration. Tissue Eng - Part A 2011;17:349–59. 10.1089/ten.tea.2010.0327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Tsai CH, Shen SY, Zhao JH, Chang YC. Platelet-rich fibrin modulates cell proliferation of human periodontally related cells in vitro. J Dent Sci 2009;4:130–5. 10.1016/S1991-7902(09)60018-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Anitua E, Prado R, Sánchez M, Orive G. Platelet-Rich Plasma: Preparation and Formulation. Oper Tech Orthop 2012;22:25–32. 10.1053/j.oto.2012.01.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Kobayashi E, Flückiger L, Fujioka-Kobayashi M, Sawada K, Sculean A, Schaller B, et al. Comparative release of growth factors from PRP, PRF, and advanced-PRF. Clin Oral Investig 2016;20:2353–60. 10.1007/s00784-016-1719-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Fujioka-Kobayashi M, Schaller B, Mourão CFDAB, Zhang Y, Sculean A, Miron RJ. Biological characterization of an injectable platelet-rich fibrin mixture consisting of autologous albumin gel and liquid platelet-rich fibrin (Alb-PRF). Platelets 2021;32:74–81. 10.1080/09537104.2020.1717455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Kyyak S, Blatt S, Pabst A, Thiem D, Al-Nawas B, Kämmerer PW. Combination of an allogenic and a xenogenic bone substitute material with injectable platelet-rich fibrin – A comparative in vitro study. J Biomater Appl 2020;35:83–96. 10.1177/0885328220914407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Li Z, Yu M, Jin S, Wang Y, Luo R, Huo B, et al. Stress distribution and collagen remodeling of periodontal ligament during orthodontic tooth movement. Front Pharmacol 2019;10:1263. 10.3389/fphar.2019.01263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Işeri H, Kurt G, Kişnişci R. Biomechanics of Rapid Tooth Movement by Dentoalveolar Distraction Osteogenesis. Curr. Ther. Orthod, Elsevier; 2010, p. 321–37. 10.1016/B978-0-323-05460-7.00025-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Pilon JJ, Kuijpers-Jagtman AM, Maltha JC. Magnitude of orthodontic forces and rate of bodily tooth movement. An experimental study. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 1996;110:16–23. 10.1016/S0889-5406(96)70082-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.