Abstract

Although numerous dinoflagellate species (Family Symbiodiniaceae) are present in coral reef environments, Acropora corals tend to select a single species, Symbiodinium microadriaticum, in early life stages, even though this species is rarely found in mature colonies. In order to identify molecular mechanisms involved in initial contact with native symbionts, we analyzed transcriptomic responses of Acropora tenuis larvae at 1, 3, 6, 12, and 24 h after their first contact with S. microadriaticum, as well as with non-native symbionts, including the non-symbiotic S. natans and the occasional symbiont, S. tridacnidorum. Some gene expression changes were detected in larvae inoculated with non-native symbionts at 1 h post-inoculation, but those returned to baseline levels afterward. In contrast, when larvae were exposed to native symbionts, we found that the number of differentially expressed genes gradually increased in relation to inoculation time. As a specific response to native symbionts, upregulation of pattern recognition receptor-like and transporter genes, and suppression of cellular function genes related to immunity and apoptosis, were exclusively observed. These findings indicate that coral larvae recognize differences between symbionts, and when the appropriate symbionts infect, they coordinate gene expression to establish stable mutualism.

Subject terms: Cell biology, Molecular biology

Introduction

Symbioses are ubiquitous in nature and are intricately involved in adaptation, ecology, and evolution of most life forms1, 2. Cnidarians, such as reef-building corals, are associated with endosymbiotic dinoflagellates of the family Symbiodiniaceae3, 4. Coral reefs, structurally dependent upon reef-building corals and their symbionts, are the most biologically diverse shallow-water marine ecosystems5. Most coral species (~ 71%) acquire algal symbionts directly from the ocean in each generation6. The scleractinian coral genus, Acropora, the most common and widespread in the Indo-Pacific7, harbors Symbiodinium or Durusdinium in its early life stages8, 9 while mature colonies generally harbor Cladocopium10, 11. In addition, more than half of Acropora recruits (~ 70%) at Ishigaki Island, Okinawa Prefecture, Japan, harbor Symbiodinium, even though numerous other genera/species of Symbiodiniaceae, including Cladocopium, are common in the water column9. Host-symbiont specificity can also be extended to the species level, with S. microadriaticum predominating (~ 97%) among the Symbiodinium taxa in Acropora recruits12, indicating that S. microadriaticum is a native symbiont in early life stages of Acropora in Okinawa.

For recognition of beneficial symbionts or harmful pathogens, pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) on surfaces of host cells and microbe-associated molecular patterns (MAMPs) on surfaces of symbionts are thought to be important13. In cnidarians, the PRR-MAMP system is also crucial to establish symbiotic relationships3. Cell surfaces of symbiotic dinoflagellates are populated with glycoconjugates, with some glycan motifs similar among species and others unique to each species14. Various lectins, which recognize glycans, have been isolated from corals, suggesting that these are involved in recognition of specific symbiotic partners of corals3, 15–17. After recognition of symbiotic algae, downstream cellular signaling pathways, such as the innate immune system, were modulated to initiate symbiosis18. For example, stimulation of the Toll-like receptor (TLR) signaling pathway affects the stability of symbiosis between the sea anemone, Exaiptasia diaphana, and microalgae19. In corals, several studies involving bleaching treatments of mature colonies have suggested the importance of immunity and apoptosis for their symbioses20–24. However, cellular mechanisms that occur in corals and symbionts during initial contact are still unidentified. Although several studies have examined transcriptomic responses of coral larvae to symbiotic dinoflagellates during initial contact25–28, no studies have used their native algal symbionts in early coral life stages.

We recently developed an Acropora larval system as a model to study symbiont selection and recognition by host corals29. Using this system, we previously documented transcriptomic responses of A. tenuis during symbiosis establishment with its native symbiont, S. microadriaticum (Smic)30. To study molecular responses that occur in coral larvae during initial contact with native symbionts, we analyzed the transcriptome of A. tenuis larvae at 1, 3, 6, 12, and 24 h post-inoculation (hpi) with symbionts. In addition, in order to highlight gene expression changes exclusive to native symbionts, we also investigated transcriptomic responses of A. tenuis larvae exposed to a closely related, non-symbiotic Symbiodinium taxon S. natans, (herein Snat), and an occasionally symbiotic Symbiodinium, S. tridacnidorum (herein Stri).

Results

Acroporatenuis larvae express different genes during initial contact with three Symbiodinium strains

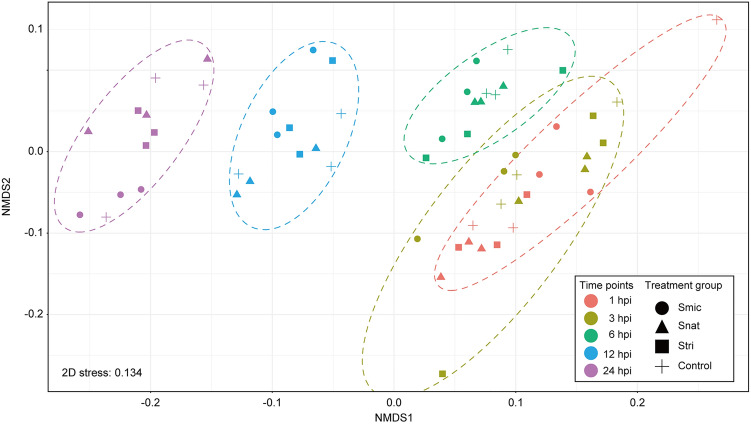

Successful infection with each symbiont culture (Smic, Snat, and Stri) was confirmed by fluorescence microscopy in all treatment groups at 24 hpi (Supplementary Fig 1), and proportions of planula larvae with symbiont cells at 24 hpi were about 30% for Smic, 6% for Snat, and 3% for Stri (details are shown in Supplementary Table S1). We performed 3’ mRNA sequencing of Acropora tenuis larvae inoculated with Smic, Snat, and Stri and with no Symbiodinium exposure (apo-symbiotic) (Supplementary Table S2). At 1, 3, 6, 12, and 24 hpi, gene expression of all A. tenuis genes was compared between Symbiodinium-exposed and unexposed groups. An average of five million RNA-Seq reads per sample were retained after quality trimming, 65% of which were mapped to A. tenuis gene models (n = 22,905, Supplementary Table S2). Non-metric multidimensional scaling (NMDS), based on gene expression levels of 5340 genes for which expression levels (TMM-normalized CPM) were larger than 10 in all samples, showed clear differences in time post-inoculation, but not in treatment groups (Smic-, Snat-, and Stri-inoculated samples and control (apo-symbiotic) samples), indicating that overall transcriptomic states of A. tenuis larvae were not significantly affected by symbiont infection and species (Fig. 1). When we compared gene expression levels between Smic-inoculated and control samples, the number of differentially expressed genes (DEGs) gradually increased with inoculation time (three genes at 3 hpi, five at 6 hpi, 106 at 12 hpi, and 392 at 24 hpi; Table 1). In contrast, larvae inoculated with Snat and Stri showed completely different transcriptomic responses (Table 1): 19 genes were differentially expressed in the Snat-inoculated samples and 49 genes in Stri-inoculated samples at 1 hpi (Supplementary Table S3). No gene expression changes were observed at 3 or 12 hpi in the presence of either Snat and Stri, and only one DEG was detected at 6 hpi in Snat- and Stri-inoculated larvae (Supplementary Table S3). Eight DEGs were detected at 24 hpi in Stri-inoculated larvae, but none in Snat-inoculated larvae (Supplementary Table S3).

Figure 1.

Non-metric multidimensional scaling (NMDS) of RNA-seq samples based on expression levels of Acropora tenuis genes. Gene expression levels among all samples were normalized using the trimmed mean of M values method, and then converted to CPM. A total of 5340 genes for which expression levels (TMM-normalized CPM) were larger than 10 in all samples were used with the “metaMDS” of the vegan package73. 2D stress was 0.134. Ellipses (dotted line) are drawn around each time point using “geom_mark_ellipse” of the ggplot package74. Hpi indicates hours post-inoculation.

Table 1.

Summary of DEG profiles of Symbiodinium-inoculated A. tenuis larvae at 1, 3, 6, 12, and 24 hpi.

| Number of DEGs | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 hpi | 3 hpi | 6 hpi | 12 hpi | 24 hpi | |

| Smic-inoculation | 0 | 3 | 5 | 106 | 392 |

| Snat-inoculation | 19 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Stri-inoculation | 49 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 8 |

Gene expression levels were compared between Symbiodinium-exposed and unexposed groups, and genes exhibiting FDR < 0.05 were considered DEGs. Smic, S. microadriaticum; Snat, S. natans; Stri, S. tridacnidorum; hpi, hour post-inoculation.

Comparison of DEG repertoires between initial contact and symbiosis establishment

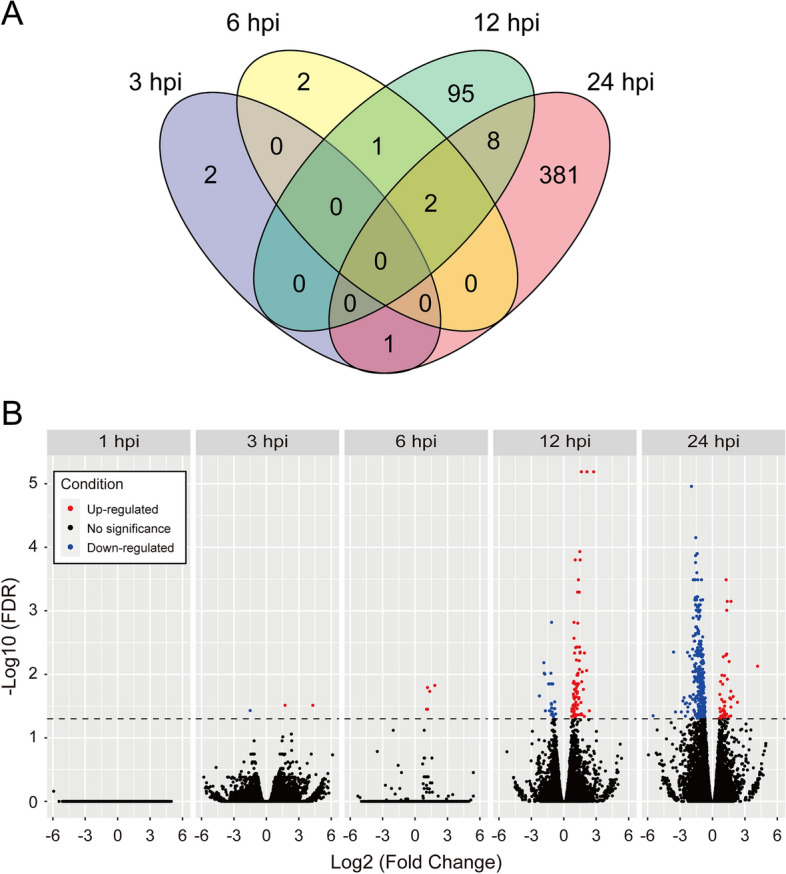

In Smic-inoculated larvae, a limited number of DEGs was shared between time points (3–24 hpi) (Fig. 2A), suggesting that gene expression changes of host corals were drastic during initial contact with native symbionts. Next, we compared DEG repertoires at 24 hpi with a previous study analyzing transcriptomic responses of A. tenuis larvae during symbiosis establishment (4, 8, and 12 dpi)30. Six DEGs were observed at all time points, 24 hpi, and 4, 8, and 12 dpi (Supplementary Fig. S2), and only 2 upregulated DEGs and 38 downregulated DEGs identified at 24 hpi in this study were also observed at 4 dpi (Supplementary Fig. 2), indicating that DEG repertoires between initial contact and symbiosis establishment are independent, but that the limited array of genes that is constantly differentially expressed in both stages could be important for transition of symbiosis phases.

Figure 2.

Transcriptomic changes of Acropora tenuis larvae during initial contact with native symbionts, Symbiodinium microadriaticum. (A) Comparison of DEG repertoires of Smic-inoculated larvae at 3, 6, 12, and 24 hpi. Raw data are provided in Supplementary Table S3. Hpi indicates hours post-inoculation. (B) DEGs that are upregulated or downregulated in Smic-inoculated larvae compared to controls are colored red or blue, respectively. The dotted line indicates FDR = 0.05.

Acroporatenuis genes that respond to native symbionts during initial contact

We annotated DEGs using BLAST homology searches against the Swiss-Prot database (Supplementary Table S3). Two, five, 80, and 42 genes were upregulated at 3, 6, 12, and 24 hpi, respectively (Fig. 2B). Among those, 0% (0/2 genes), 20% (1/5), 28% (22/80), and 88% (37/42) of DEGs were annotated (Supplementary Table S3). One, 26, and 350 genes were downregulated at 3, 12, and 24 hpi, respectively (Fig. 2B). Of those, 100% (1/1 gene), 69% (18/26), and 70% (246/350) of DEGs were annotated (Supplementary Table S3), indicating that upregulated DEGs involved in initial contact with native symbionts have no homologs that have been annotated yet.

DEGs with Swiss-Prot annotation were used to infer biological processes that occur in Smic-inoculated larvae. To ensure reliability, we focused on categories of UniProt keywords in which more than two annotated genes were detected at each time point. Upregulated DEGs belonging to seven and five categories and downregulated DEGs belonging to one and 28 categories were detected at 12 and 24 hpi, respectively (Table 2). Some categories, such as transport and biological rhythms, were commonly observed among both up- and downregulated DEGs at 24 hpi (Table 2). In A. tenuis, seven genes similar to core circadian genes were differentially expressed from 4 to 12 d post-Symbiodinium inoculation in the previous study 30, and three (CRY1: aten_s0034.g64 and aten_s0034.g66; TIMELESS: aten_s0021.g100) of them were also differentially expressed in Smic-inoculated larvae at 12 or 24 hpi, or Stri-inoculated samples at 1 hpi (Supplementary Figure S3), indicating that gene expression of core circadian rhythm-regulated genes changed as soon as they were inoculated with Symbiodinium. When A. tenuis larvae were inoculated with native symbionts, several sugar- and amino acid-transporter genes were specifically upregulated during symbiosis establishment30. Nine DEGs possibly involved in transport were upregulated in Smic-inoculated larvae (Supplementary Fig. S4), as were one that contributes to cell volume homeostasis (SLC12A6: aten_s0482.g4) and two that may transport sugars or amino acids (SLC2A12: aten_s0153.g34, SLC16A3: aten_s0261.g16), suggesting that these may be needed to adjust intercellular condition within the symbiosome during initial contact with native symbionts. In addition, in the previous study, two genes, aten_s0153.g34 (SLC2A12) and aten_s0482.g4 (SLC12A6), were also upregulated at 4 dpi30, suggesting their importance during the transition to symbiosis.

Table 2.

Gene function categories (UniProt Keywords) of differentially expressed genes at 12 and 24 h post-inoculation in Smic-inoculated larvae.

| Annotation term (UniProt Keywords) | Number of genes | |

|---|---|---|

| Up-regulated at 12 hpi | Transport | 6 |

| Biological rhythms | 4 | |

| mRNA processing | 4 | |

| Sensory transduction | 3 | |

| Transcription | 3 | |

| Cell adhesion | 2 | |

| Cell cycle | 2 | |

| Ubl conjugation pathway | 2 | |

| Down-regulated at 12 hpi | Transport | 6 |

| Up-regulated at 24 hpi | Transcription | 4 |

| Transport | 4 | |

| Differentiation | 3 | |

| Biological rhythms | 2 | |

| Neurogenesis | 2 | |

| Down-regulated at 24 hpi | Transcription | 41 |

| Cell cycle | 40 | |

| Transport | 29 | |

| mRNA processing | 17 | |

| Cilium biogenesis/degradation | 13 | |

| Apoptosis | 12 | |

| DNA damage | 12 | |

| Differentiation | 7 | |

| Endocytosis | 6 | |

| Wnt signaling pathway | 6 | |

| RNA-mediated gene silencing | 5 | |

| Ubl conjugation pathway | 5 | |

| rRNA processing | 5 | |

| Biological rhythms | 4 | |

| Host-virus interaction | 4 | |

| Immunity | 4 | |

| Inflammatory response | 4 | |

| Cell adhesion | 3 | |

| DNA recombination | 3 | |

| Ribosome biogenesis | 3 | |

| Chromosome partition | 2 | |

| DNA condensation | 2 | |

| DNA replication | 2 | |

| Exocytosis | 2 | |

| Hearing | 2 | |

| Lipid metabolism | 2 | |

| Meiosis | 2 | |

| Myogenesis | 2 | |

| Nonsense-mediated mRNA decay | 2 | |

| Protein biosynthesis | 2 | |

| Sensory transduction | 2 |

On the other hand, 23 categories of UniProt keywords were exclusively observed among downregulated DEGs at 24 hpi (Table 2). In these categories, transcription and translation (RNA-mediated gene splicing, rRNA processing, ribosome biogenesis, chromosome partition, DNA condensation, nonsense-mediated mRNA decay, and protein biosynthesis), cell proliferation (cell cycle, differentiation, DNA recombination, and myogenesis), bulk transport (endocytosis and exocytosis), and immune response (apoptosis and immunity) were included (Table 2).

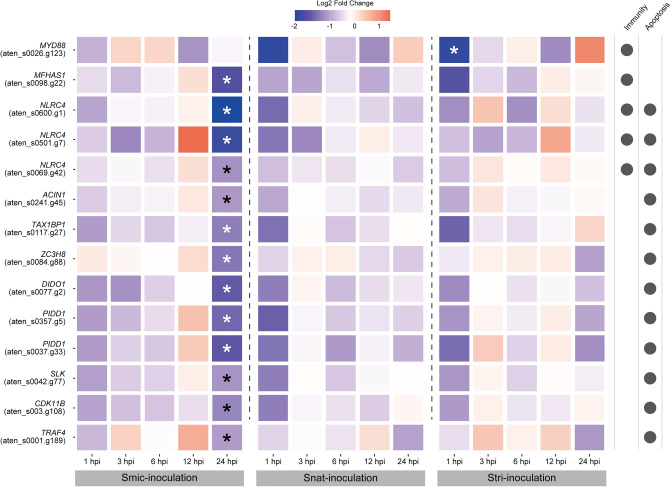

DEGs related to immunity and apoptosis

It is well known that the immune system is modulated during symbiosis establishment in sea anemones 18, 31, 32. Four genes (NLRC4: aten_s0069.g42, aten_s0501.g7 and aten_s0600.g1; MFHAS1: aten_s0098.g22) possibly involved in immunity were significantly downregulated in Smic-inoculated samples at 24 hpi, and one gene (MYD88: aten_s0026.g123) was downregulated in Stri-inoculated larvae at 1 hpi (Fig. 3). Apoptosis plays a major role in the host immune response to invading microbes33. 12 genes (NLRC4: aten_s0069.g42, aten_s0501.g7 and aten_s0600.g1; ACIN1: aten_s0241.g45; TAXBP1: aten_s0117.g27; ZC3H8: aten_s0084.g88; DIDO1: aten_s0077.g2; PIDD1: aten_s0357.g5 and aten_s0037.g33; SLK: aten_s0042.g77; CDK11B: aten_s0003.g108; TRAF4: aten_s0001.g189) involved in apoptosis were exclusively downregulated in Smic-inoculated larvae at 24 hpi (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

Expression patterns of DEGs related to immunity and apoptosis. DEGs possibly involved in immunity and apoptosis are shown. Possible gene names and gene IDs are shown at the left. Circles on the right indicate functions with which a given gene is associated. “Fold Change” indicates the relative gene expression level compared to controls (apo-symbiotic). NLRC4: NLR family CARD domain-containing protein 4. MFHAS1: Malignant fibrous histiocytoma-amplified sequence 1. MYD88: Myeloid differentiation primary response protein 88. PIDD1: p53-induced death domain-containing protein 1. ACIN1: Apoptotic chromatin condensation inducer in the nucleus. TAX1BP1: Tax1-binding protein 1 homolog. ZC3H8: Zinc finger CCCH domain-containing protein 8. DIDO1: Death-inducer obliterator 1. SLK: STE20-like serine/threonine-protein kinase. CDK11B: Cyclin-dependent kinase 11B. TRAF4: TNF receptor-associated factor 4.

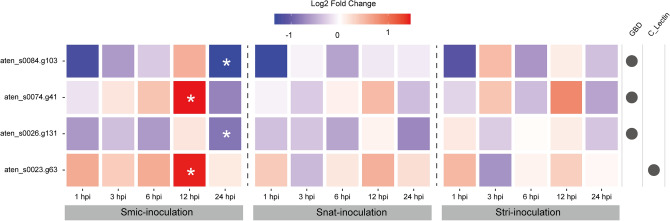

DEGs related to symbiont recognition and phagocytosis

The initial interaction with algal symbionts must involve pattern recognition3. Lectin-like genes are important to identify glycans on surfaces of symbionts15. We identified 306 genes with lectin-like domains from the A. tenuis genome (Supplemental Data S1) and found that four genes (aten_s0084.g103; aten_s0074.g41; aten_s0026.g131; aten_s0023.g63) were exclusively differentially expressed in Smic-inoculated larvae (Fig. 4). Of those, three genes (aten_s0074.g41, aten_s0026.g131 and aten_s0023.g63) were predicted by DeepLoc, a deep learning neural network model, to be localized on the cell membrane. Endocytosis, including phagocytosis, is the main cellular mechanism to acquire symbionts3. Among genes involved in this process, one (STAB2: aten_s0096.g129) was upregulated, but three genes (FKBP15: aten_s0162.g6; EPS15: aten_s0079.g89; MYO6: aten_s0018.g47) were downregulated in Smic-inoculated larvae (Supplementary Fig. S5). One gene (LRP4: aten_s0033.g2) was downregulated in all three samples, but at a different time, and one gene (APP: aten_s0027.g17) was exclusively downregulated in Stri-inoculated larvae (Supplementary Fig. S5). On the other hand, two genes (UNC13B: aten_s0106.g44l; MIA3: aten_s0223.g30) involved in exocytosis were significantly downregulated in Smic-inoculated samples (Supplementary Fig. S5).

Figure 4.

Expression patterns of DEGs related to pattern recognition. DEGs bearing C-type lectin-like superfamily (C_lectin) or galactose-binding domain-like superfamily (GBD) domains are shown. Gene IDs are shown on the left. Circles on the right indicate domains that the gene possesses. “Fold Change” indicates the relative gene expression level compared to controls (apo-symbiotic).

DEGs possibly controlling gene expression for establishment of coral-algal symbiosis

In order to identify genes that may govern coral-algal symbiosis, we focused on signal molecules and transcription factors among DEGs. While eight genes (HLF: aten_s0063.g61 and aten_s0156.g13; TEF: aten_s0156.g11; ETS-2: aten_s0128.g47; HES4: aten_s0026.g27; ZNF271: aten_s0028.g32; CIC: aten_s0075.g3; GCM2: aten_s0286.g9) with transcription factor domains were detected as DEGs, no genes with signaling domains were detected (Supplementary Table S4). These genes were not differentially expressed during symbiosis establishment with native symbionts30, indicating that they may control the drastic changes in gene expression during initial contact with native symbionts.

Discussion

A previous study reported that A. digitifera larvae immediately changed the expression level of 1,073 genes after exposure (4 hpi) to a non-native symbiont (Breviolum minutum), but that no genes were differentially expressed later (at 12 and 24 hpi)26. Consistent with the previous study, A. tenuis larvae responded to non-native symbionts immediately after inoculation, but expression levels of DEG soon returned to baseline levels (Table 1), suggesting that initial recognition of Symbiodinium occurred within 1 h. In contrast, A. tenuis larvae gradually responded during initial contact with native symbionts (Table 1). Interestingly, when A. tenuis larvae were exposed to Cladocopium, a native symbiont of adult corals, the number of DEGs did not increase with infection time27, which is different from the results of this study. These differences were probably caused by an infection with symbionts that should not have co-existed in the early life stages in nature. For example, Yuyama et al.34 reported that all inoculated Cladocopium in A. tenuis polyps were abnormal in shape, suggesting that Cladocopium may be unsuitable for host corals in early life stages, as the majority of Acropora larvae favor Symbiodinium or Durusdinium in nature8, 12.

Symbiotic dinoflagellates possess glycan ligands on their cell surfaces, such as mannose, glucose, and galactose, which are recognized as MAMPs by host corals15–17, and lectins that recognize the glycan ligands have been reported from various corals17, 35–40. Although continuous gene expression of these lectins should be crucial during initial contact with symbionts, expression of some of them was upregulated when coral larvae were exposed to symbionts26, 30. In this study, two genes with lectin-related domains were significantly upregulated only when A. tenuis larvae were inoculated with native symbionts (Fig. 4). Interestingly, no genes with lectin-related domains were reportedly differentially expressed when A. tenuis was exposed to Cladocopium27. Considering the specific upregulation of genes with lectin domains to native symbionts in early life stages, these two genes may help to recognize appropriate symbionts in specific life stages.

Dinoflagellates produce diverse photosynthetic products, such as carbohydrates and amino acids41, 42, and metabolic exchanges between hosts and symbionts are well known4. Upregulation of solute carrier (SLC) transporters, which transport sugars and amino acids, in host corals under daylight43 and several days after exposure to native symbionts30 have been reported. These SLC transporters are thought to be the major pathway for metabolic exchanges between host corals and symbionts. Although Mohamed et al.27 reported upregulation of transporters (S23A2 and S26A6) by 72 hpi with Cladocopium, no genes with potential to transport sugars or amino acids were included among DEGs of host corals in that study. In contrast, SLC2A12-like gene, which may transport sugars, was upregulated at 24 hpi in this study (Supplementary Fig, S4). Furthermore, this gene was also upregulated at 4 d post-S. microadriaticum inoculation30, suggesting that nutrient exchange with native symbionts occurs as early as 24 hpi.

Three NLRC4-like genes and one MFHAS1-like gene were specifically downregulated in Smic-inoculated larvae (Fig. 3). NLRC4 is a member of the nucleotide oligomerization domain-like receptor (NLR) family44, and coral-specific expansion of this group has been reported45. NLR can activate several innate immune pathways, including the NFkB and MAPK pathways44. MFHAS1 is a leucine-rich repeat-containing protein and has the potential to modulate the TLR signaling pathway in human macrophages46. Although we could not detect downregulation of downstream genes in bulk RNA-seq, these results suggest the occurrence of immune-suppression in Smic-inoculated larvae. On the other hand, an MYD88-like gene was significantly downregulated in larvae inoculated with S. tridacnidorum, which is an occasional symbiont in early life stages of Acropora12. MYD88 is a critical adapter protein downstream of all TLR signaling in mammals47, suggesting that immune-suppression may also occur in Stri-inoculated larvae. The importance of immune suppression during symbiosis establishment has been suggested in sea anemones (reviewed in Mansfield and Gilmore18), and recently it was experimentally demonstrated in Aiptasia19, suggesting that immune suppression is conserved and essential for cnidarians during initial contact with their symbionts.

Apoptosis is a highly conserved programmed cell death mechanism in metazoans48, 49 and has previously been suggested as a possible pathway in the breakdown of symbiosis under stress in corals22–24. Although the possible role of apoptosis in maintenance of a stable symbiotic relationship has not been experimentally addressed, its association during initial contact with symbiotic algae has been suggested, since some apoptosis-related genes were up- and downregulated25, 50. Hence, it is thought that apoptosis may contribute to the dynamic equilibrium between host and symbiont cell growth and proliferation50. However, another hypothesis has also been proposed by Dunn and Weis51. When caspase activity that causes apoptosis was inhibited, larvae of the coral, Fungia scutaria, were successfully colonized with a symbiont that is normally unable to colonize; therefore, apoptosis contributes to selection of compatible symbionts after phagocytic uptake51. Consistent with this hypothesis, 11 genes involved in apoptosis were exclusively downregulated in larvae inoculated with native symbionts in this study (Fig. 3), indicating that suppression of apoptosis may be conserved among corals as a selection mechanism after phagocytic uptake of symbionts.

In addition to suppression of genes involved in immunity and apoptosis, most DEGs (89.2%) were downregulated at 24 hpi, and functional annotation revealed that many of these encoded transcription and translation, cell proliferation, and immune responses (Table 2), indicating that overall downregulation of cellular functions occurs during initial contact with native symbionts. Although we were unable to detect it in larval transcriptome data until 24 hpi, metabolic suppression of amino acids, sugars, and lipids has been reported in A. tenuis larvae at 4–12 dpi30; thus, suppression of genes involved in transcription and translation may be related to metabolic suppression.

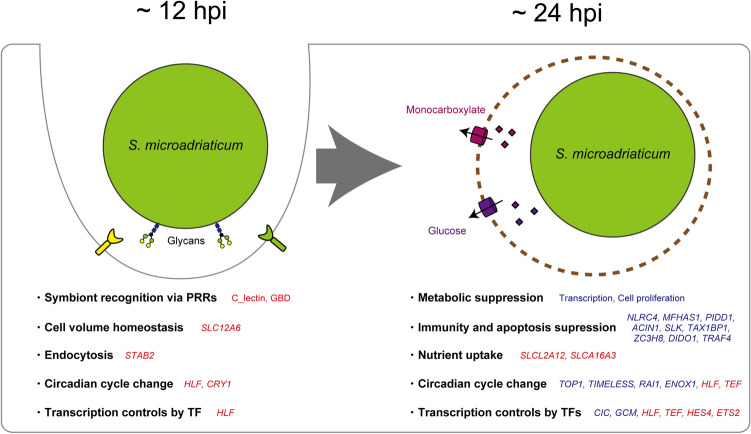

Symbiodinium is one of the dominant algal symbionts in early life stages of Acropora corals at Ishigaki Island, Okinawa Prefecture, Japan (until they are at least 14 d old) 12 and the southern Great Barrier Reef, Australia (until they are at least 83 d old)52. One reason for this may be that Symbiodinium are highly infectious to corals at this stage8, 52, 53. However, another possible reason for this may be that Symbiodinium tolerates higher solar irradiance and thermal stress54–57. Despite these advantages, adult colonies of Acropora in those locations are mainly associated with Cladocopium10, 11, 52. Perhaps this is because Symbiodinium has a lower carbon fixation rate than Cladocopium, which is required to form calcium carbonate skeletons58. The genus Symbiodinium includes species with characteristics ranging from symbiotic to opportunistic or free living59. Symbiosis between Acropora and Symbiodinium differs even among closely related species29. Smic (AJIS2-C2) isolated from an Acropora recruit is taken up by A. tenuis planula larvae more than other Symbiodinium29. Our transcriptomic data suggest that Smic modulates the immune system of host corals and exchanges metabolites with the host within 24 h (Fig. 5), indicating that highly infectious Smic is a suitable symbiotic partner for Acropora in early life stages.

Figure 5.

Schematic time series summary of possible intercellular events occurring in Acropora tenuis larvae during initial contact with native symbionts. Sentences with a dot indicate possible cellular events, and genes associated with them are shown nearby. A brown dotted line indicates a symbiosome (the organelle in which a symbiont resides). Red or blue text indicates significantly (FDR < 0.05) up- or down-regulated genes, respectively. PRRs indicate pattern recognition receptors. TF indicates transcription factor.

In summary, our data show clear transcriptomic differences in coral larvae in response to native and non-native symbionts, indicating that A. tenuis larvae recognize different Symbiodinium strains within 1 hpi. When A. tenuis larvae contact native symbionts, symbiont recognition, circadian cycle changes, cell volume homeostasis, and endocytic uptake occur within 12 hpi (Fig. 5), and then metabolic suppression, immune and apoptosis suppression, circadian cycle changes, and nutrient uptake are induced by 24 hpi (Fig. 5). This study highlights not only the importance of immune-response suppression and apoptosis suppression during initial contact with native symbionts, but also the relevance of cellular mechanisms, such as circadian cycle changes and nutrient uptake, during the period from initial contact to symbiosis establishment. Although RNA-seq techniques have become more feasible than in the previous decade, it is still difficult to capture minute gene expression changes with bulk RNA-seq, because only a small percentage of the volume of a coral larva contains cells with algae. Tissue-specific RNA-seq19, 60, single cell RNA-seq61, or coral cell lines62 may reveal more comprehensive molecular responses of coral symbioses in the future.

Methods

Preparation of Acroporatenuis planula larvae and Symbiodinium culture strains

Colonies of A. tenuis were collected in Sekisei Lagoon, Okinawa, Japan, in May 2018, and were maintained in aquaria at the Yaeyama Station, Fisheries Technology Institute, until spawning. Permits for coral collection were kindly provided by the Okinawa Prefectural Government for research use (Permits 29-74). After fertilization, we washed the embryos with seawater passed through a 0.2-µm filter (FSW) to remove unwanted contaminants. Embryos were maintained at a concentration of ~ 2 individuals per mL of FSW in plastic bottles at 23.6 ± 0.7 °C. FSW was changed once a day until planula larvae reached 6 d post-fertilization.

We used three Symbiodinium culture strains, AJIS2-C2 (S. microadriaticum), CS-161 (S. tridacnidorum) and ISS-C2-Sy (S. natans) in this study. The culture strain AJIS-C2 was originally isolated from Acropora recruits63. Culture strain CS-161, which has occasionally been detected in wild corals, was purchased from the Australian National Algae Culture Collection, Australia. Culture strain ISS-C2-Sy was originally isolated from coral reef sand at Ishigaki Island63.

Inoculation experiments

A. tenuis larvae were divided into four treatment groups, with three replicates per treatment. Inoculation experiments using the three culture strains were conducted as in Yamashita et al.29. In each replicate, ~ 1500 A. tenuis planula larvae at 6 d post-fertilization were placed in 2-L bottles containing 1500 mL of FSW. Smic, Snat and Stri strains at 50 cells/mL were added to the first to third group of larvae, respectively. The remaining group was used as control (apo-symbiotic). All bottles were kept at 23.6 ± 0.7 °C. At 24 hpi, 10 randomly selected larvae from each bottle were used for observation of the algae under a fluorescence microscope (BX50; Olympus; 400–410 nm excitation) to determine whether they were infected with Symbiodinium.

RNA extraction, sequencing, and transcriptomic analyses

At 1, 3, 6, 12, and 24 hpi, ~ 300 planula larvae from each bottle were collected and stored at − 80 °C until use. Coral larvae were homogenized with zirconia beads (ZB-20) in TRIzol reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific) using a beads beater (TOMY Micro Smash MS-100) at 3000 rpm for 10 s. Total RNA was extracted from each larva using TRIzol reagent according to the manufacturer’s protocol. A Collibri 3’ mRNA Library Prep Kit for Illumina (Thermo Fisher Scientific) was used for sequencing library preparations. Sequencing adaptors were attached by PCR amplification with 16 cycles of annealing according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Each library was sequenced on a NovaSeq 6000 (Illumina) with 50-bp, single-end reads. Low-quality reads (quality score < 20 and length < 20-bp) and Illumina sequence adaptors were trimmed with CUTADAPT v1.1664. Then cleaned reads were mapped to the A. tenuis gene model (mRNA) using BWA v0.7.1765 with default settings. Transcript abundances in each sample were quantified using SALMON v1.0.066. Mapping counts were normalized by the trimmed mean of M values (TMM) method, and then converted to counts per million (CPM) using EdgeR v3.32.167 in R v4.0.368. Gene expression levels (numbers of mapped reads) in treatment groups were compared with control samples (apo-symbiotic) to identify DEGs. Obtained p-values were adjusted using the Benjamini–Hochberg method in EdgeR. When the gene expression level was significantly different (False discovery rate < 0.05) than control samples, genes were considered DEGs. We downloaded gene models of A. tenuis69 from the genome browser of the OIST Marine Genomics Unit (https://marinegenomics.oist.jp). Gene models were annotated with BLASTP70 and InterProScan71 against the Swiss-Prot database and Pfam database as described in Yoshioka et al.30. Putative transposable elements in gene models were identified with Pfam keywords (“Transposase”, “Integrase”, and “Reverse transcriptase”) and were excluded from analyses in this study. Subcellular localization of lectin-like genes was predicted using the DeepLoc-1.0 online server72.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by JSPS KAKENHI Grants (20H03235 and 20K21860 for CS, 18H02270 and 21H04742 for HY, and 20H03066 for GS) and Grant-in-Aid for JSPS Fellows to YY (20J21301). Computations were partially performed on the NIG supercomputer at ROIS National Institute of Genetics.

Author contributions

C.S. and H.Y. Commenced the project. G.S. and C.S. Performed coral sampling and larval culturing. H.Y. Maintained Symbiodinium culture strains and performed inoculation experiments. Y.Y. performed molecular biological experiments, bioinformatic analyses, and wrote the main manuscript. C.S. supervised the project and edited the main manuscript. All authors checked and commented on the manuscript.

Data availability

Raw RNA sequencing data were deposited in the DDBJ/EMBL/GenBank databases under accession number DRA013077 (BioProject ID: PRJDB8332). A genome browser for A. tenuis is available from the Marine Genomics Unit web site (https://marinegenomics.oist.jp/). Results of statistical analyses for identify DEGs were provided in Supplementary Data S2. Normalized expression data (TMM-normalized CPM) was provided in Supplementary Data S3.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-022-06822-3.

References

- 1.Gilbert SF, Bosch TC, Ledón-Rettig C. Eco-Evo-Devo: Developmental symbiosis and developmental plasticity as evolutionary agents. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2015;16:611–622. doi: 10.1038/nrg3982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McFall-Ngai M, et al. Animals in a bacterial world, a new imperative for the life sciences. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2013;110:3229–3236. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1218525110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Davy SK, Allemand D, Weis VM. Cell biology of Cnidarian-dinoflagellate symbiosis. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2012;76:229–261. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.05014-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yellowlees D, Rees TA, Leggat W. Metabolic interactions between algal symbionts and invertebrate hosts. Plant. Cell. Environ. 2008;31:679–694. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3040.2008.01802.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Roberts CM, et al. Marine biodiversity hotspots and conservation priorities for tropical reefs. Science. 2002;295:1280–1284. doi: 10.1126/science.1067728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baird AH, Guest JR, Willis BL. Systematic and biogeographical patterns in the reproductive biology of scleractinian corals. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 2009;40:551–571. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wallace, C. C. in Staghorn Corals of the World: A Revision of the Coral Genus Acropora (Scleractinia; Astrocoeniina; Acroporidae) Worldwide, with Emphasis on Morphology, Phylogeny and Biogeography. 421 (CSIRO Publishing, Collingwood, 1999).

- 8.Abrego D, Van Oppen MJ, Willis BL. Highly infectious symbiont dominates initial uptake in coral juveniles. Mol. Ecol. 2009;18:3518–3531. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2009.04275.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yamashita H, Suzuki G, Hayashibara T, Koike K. Acropora recruits harbor “rare” Symbiodinium in the environmental pool. Coral Reefs. 2013;32:355–366. [Google Scholar]

- 10.LaJeunesse TC. “Species” radiations of symbiotic dinoflagellates in the Atlantic and Indo-pacific since the miocene-pliocene transition. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2005;22:570–581. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msi042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lien Y, Fukami H, Yamashita Y. Symbiodinium Clade C Dominates Zooxanthellate Corals (Scleractinia) in the Temperate Region of Japan. Zool. Sci. 2012;29:173–180. doi: 10.2108/zsj.29.173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yamashita H, Suzuki G, Kai S, Hayashibara T, Koike K. Establishment of coral–algal symbiosis requires attraction and selection. PLoS One. 2014;9:e97003. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0097003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Janeway CA, Jr, Medzhitov R. Innate immune recognition. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2002;20:197–216. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.20.083001.084359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Markell, D. A., Trench, R. K. & Iglesias-Prieto, R. Macromolecules associated with the cell walls of symbiotic dinoflagellates. Symbiosis, 19–31 (1992).

- 15.Wood-Charlson EM, Hollingsworth LL, Krupp DA, Weis VM. Lectin/glycan interactions play a role in recognition in a coral/dinoflagellate symbiosis. Cell. Microbiol. 2006;8:1985–1993. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2006.00765.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Koike K, et al. Octocoral chemical signaling selects and controls dinoflagellate symbionts. Biol. Bull. 2004;207:80–86. doi: 10.2307/1543582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jimbo M, et al. The D-galactose-binding lectin of the octocoral Sinularia lochmodes: Characterization and possible relationship to the symbiotic dinoflagellates. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. B: Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2000;125:227–236. doi: 10.1016/s0305-0491(99)00173-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mansfield KM, Gilmore TD. Innate immunity and cnidarian-Symbiodiniaceae mutualism. Dev. Comp. Immunol. 2019;90:199–209. doi: 10.1016/j.dci.2018.09.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jacobovitz MR, et al. Dinoflagellate symbionts escape vomocytosis by host cell immune suppression. Nat. Microbiol. 2021;6:769–782. doi: 10.1038/s41564-021-00897-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Barshis DJ, et al. Genomic basis for coral resilience to climate change. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2013;110:1387–1392. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1210224110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Traylor-Knowles N, Rose NH, Sheets EA, Palumbi SR. Early transcriptional responses during heat stress in the coral Acropora hyacinthus. Biol. Bull. 2017;232:91–100. doi: 10.1086/692717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.DeSalvo MK, et al. Differential gene expression during thermal stress and bleaching in the Caribbean coral Montastraea faveolata. Mol. Ecol. 2008;17:3952–3971. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2008.03879.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ainsworth TD, Hoegh-Guldberg O, Heron SF, Skirving WJ, Leggat W. Early cellular changes are indicators of pre-bleaching thermal stress in the coral host. J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 2008;364:63–71. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tchernov D, et al. Apoptosis and the selective survival of host animals following thermal bleaching in zooxanthellate corals. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2011;108:9905–9909. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1106924108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Voolstra CR, et al. The host transcriptome remains unaltered during the establishment of coral–algal symbioses. Mol. Ecol. 2009;18:1823–1833. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2009.04167.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mohamed AR, et al. The transcriptomic response of the coral Acropora digitifera to a competent Symbiodinium strain: the symbiosome as an arrested early phagosome. Mol. Ecol. 2016;25:3127–3141. doi: 10.1111/mec.13659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mohamed AR, et al. Dual RNA-sequencing analyses of a coral and its native symbiont during the establishment of symbiosis. Mol. Ecol. 2020;29:3921–3937. doi: 10.1111/mec.15612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schwarz JA, et al. Coral life history and symbiosis: functional genomic resources for two reef building Caribbean corals, Acropora palmata and Montastraea faveolata. BMC Genom. 2008;9:1–16. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-9-97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yamashita H, Suzuki G, Shinzato C, Jimbo M, Koike K. Symbiosis process between Acropora larvae and Symbiodinium differs even among closely related Symbiodinium types. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 2018;592:119–128. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yoshioka Y, et al. Whole-genome transcriptome analyses of native symbionts reveal host coral genomic novelties for establishing coral-algae symbioses. Genome Biol. Evolut. 2021;13:240. doi: 10.1093/gbe/evaa240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mansfield KM, et al. Transcription factor NF-κB is modulated by symbiotic status in a sea anemone model of cnidarian bleaching. Sci. Rep. 2017;7:1–14. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-16168-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Matthews JL, et al. Optimal nutrient exchange and immune responses operate in partner specificity in the cnidarian-dinoflagellate symbiosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2017;114:13194–13199. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1710733114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.James ER, Green DR. Manipulation of apoptosis in the host–parasite interaction. Trends Parasitol. 2004;20:280–287. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2004.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yuyama I, Ishikawa M, Nozawa M, Yoshida M, Ikeo K. Transcriptomic changes with increasing algal symbiont reveal the detailed process underlying establishment of coral-algal symbiosis. Sci. Rep. 2018;8:16802. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-34575-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jimbo M, Koike K, Sakai R, Muramoto K, Kamiya H. Cloning and characterization of a lectin from the octocoral Sinularia lochmodes. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2005;330:157–162. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.02.137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jimbo M, Yamashita H, Koike K, Sakai R, Kamiya H. Effects of lectin in the scleractinian coral Ctenactis echinata on symbiotic zooxanthellae. Fish. Sci. 2010;76:355–363. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kvennefors ECE, Leggat W, Hoegh-Guldberg O, Degnan BM, Barnes AC. An ancient and variable mannose-binding lectin from the coral Acropora millepora binds both pathogens and symbionts. Dev. Comp. Immunol. 2008;32:1582–1592. doi: 10.1016/j.dci.2008.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kvennefors ECE, et al. Analysis of evolutionarily conserved innate immune components in coral links immunity and symbiosis. Dev. Comp. Immunol. 2010;34:1219–1229. doi: 10.1016/j.dci.2010.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Vidal-Dupiol J, et al. Coral bleaching under thermal stress: Putative involvement of host/symbiont recognition mechanisms. BMC Physiol. 2009;9:14. doi: 10.1186/1472-6793-9-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kuniya N, et al. Possible involvement of Tachylectin-2-like lectin from Acropora tenuis in the process of Symbiodinium acquisition. Fish. Sci. 2015;81:473–483. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Muscatine L, Cernichiari E. Assimilation of photosynthetic products of zooxanthellae by a reef coral. Biol. Bull. 1969;137:506–523. doi: 10.2307/1540172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bil, K. Y., Kolmakov, P. V. & Muscatine, L. Photosynthetic products of zooxanthellae of the reef-building corals Stylophora pistillata and Seriatopora coliendrum from different depths of the Seychelles Islands. Atoll Res. Bull. (1992).

- 43.Bertucci A, Forêt S, Ball EE, Miller DJ. Transcriptomic differences between day and night in Acropora millepora provide new insights into metabolite exchange and light-enhanced calcification in corals. Mol. Ecol. 2015;24:4489–4504. doi: 10.1111/mec.13328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Franchi L, Warner N, Viani K, Nuñez G. Function of Nod-like receptors in microbial recognition and host defense. Immunol. Rev. 2009;227:106–128. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2008.00734.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hamada M, et al. The complex NOD-like receptor repertoire of the coral Acropora digitifera includes novel domain combinations. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2013;30:167–176. doi: 10.1093/molbev/mss213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ng AC, et al. Human leucine-rich repeat proteins: a genome-wide bioinformatic categorization and functional analysis in innate immunity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2011;108:4631–4638. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1000093107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ghosh D, Stumhofer J. Do you see what I see: Recognition of protozoan parasites by toll-like receptors. Curr. Immunol. Rev. 2013;9:129–140. doi: 10.2174/1573395509666131203225929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wyllie AH, Kerr JR, Currie AR. Cell death: The significance of apoptosis. Int. Rev. Cytol. 1980;68:251–306. doi: 10.1016/s0074-7696(08)62312-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Dunn SR, Phillips WS, Spatafora JW, Green DR, Weis VM. Highly conserved caspase and Bcl-2 homologues from the sea anemone Aiptasia pallida: Lower metazoans as models for the study of apoptosis evolution. J. Mol. Evol. 2006;63:95–107. doi: 10.1007/s00239-005-0236-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lehnert EM, et al. Extensive differences in gene expression between symbiotic and aposymbiotic cnidarians. G3 Genes Genom. Genetics. 2014;4:277–295. doi: 10.1534/g3.113.009084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Dunn SR, Weis VM. Apoptosis as a post-phagocytic winnowing mechanism in a coral–dinoflagellate mutualism. Environ. Microbiol. 2009;11:268–276. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2008.01774.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gómez-Cabrera MDC, Ortiz JC, Loh W, Ward S, Hoegh-Guldberg O. Acquisition of symbiotic dinoflagellates (Symbiodinium) by juveniles of the coral Acropora longicyathus. Coral Reefs. 2008;27:219–226. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Robison JD, Warner ME. Differential impacts of photoacclimation and thermal stress on the photobiology of four different phylotypes of Symbiodinium (pyrrhophyta) 1. J. Phycol. 2006;42:568–579. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Reynolds JM, Bruns BU, Fitt WK, Schmidt GW. Enhanced photoprotection pathways in symbiotic dinoflagellates of shallow-water corals and other cnidarians. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2008;105:13674–13678. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0805187105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Suggett DJ, et al. Photosynthesis and production of hydrogen peroxide by Symbiodinium (pyrrhophyta) phylotypes with different thermal tolerances 1. J. Phycol. 2008;44:948–956. doi: 10.1111/j.1529-8817.2008.00537.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ragni M, et al. PSII photoinhibition and photorepair in Symbiodinium (Pyrrhophyta) differs between thermally tolerant and sensitive phylotypes. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 2010;406:57–70. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lesser MP, Stat M, Gates RD. The endosymbiotic dinoflagellates (Symbiodinium sp.) of corals are parasites and mutualists. Coral Reefs. 2013;32:603–611. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Stat M, Morris E, Gates RD. Functional diversity in coral–dinoflagellate symbiosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2008;105:9256–9261. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0801328105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.LaJeunesse TC, et al. Systematic revision of symbiodiniaceae highlights the antiquity and diversity of coral endosymbionts. Curr. Biol. 2018;28:2570–2580.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2018.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Chiu Y, Shikina S, Yoshioka Y, Shinzato C, Chang CD. novo transcriptome assembly from the gonads of a scleractinian coral, Euphyllia ancora: molecular mechanisms underlying scleractinian gametogenesis. BMC Genom. 2020;21:1–20. doi: 10.1186/s12864-020-07113-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Levy S, et al. A stony coral cell atlas illuminates the molecular and cellular basis of coral symbiosis, calcification, and immunity. Cell. 2021;184:2973–2987.e18. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2021.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kawamura K, et al. In vitro symbiosis of reef-building coral cells with photosynthetic dinoflagellates. Front. Marine Sci. 2021 doi: 10.3389/fmars.2021.706308. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Yamashita H, Koike K. Genetic identity of free-living Symbiodinium obtained over a broad latitudinal range in the Japanese coast. Phycol. Res. 2013;61:68–80. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Martin M. Cutadapt removes adapter sequences from high-throughput sequencing reads. EMBnet.journal. 2011;17:10. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Li H, Durbin R. Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows-Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:1754–1760. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Patro R, Duggal G, Love MI, Irizarry RA, Kingsford C. Salmon provides fast and bias-aware quantification of transcript expression. Nat. Methods. 2017;14:417–419. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.4197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Robinson MD, McCarthy DJ, Smyth GK. edgeR: A Bioconductor package for differential expression analysis of digital gene expression data. Bioinformatics. 2010;26:139–140. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.R core team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. (2020).

- 69.Shinzato C, et al. Eighteen coral genomes reveal the evolutionary origin of Acropora strategies to accommodate environmental changes. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2021;38:16–30. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msaa216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Camacho C, et al. BLAST plus: Architecture and applications. BMC Bioinform. 2009;10:421. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-10-421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Jones P, et al. InterProScan 5: Genome-scale protein function classification. Bioinformatics. 2014;30:1236–124s0. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Almagro AJJ, Sønderby CK, Sønderby SK, Nielsen H, Winther O. DeepLoc: prediction of protein subcellular localization using deep learning. Bioinformatics. 2017;33:3387–3395. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btx431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Oksanen J, et al. The vegan package. Commun. Ecol. Package. 2007;10:719. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Wickham H. Elegant graphics for data analysis. Media. 2009;35:10.1007. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Raw RNA sequencing data were deposited in the DDBJ/EMBL/GenBank databases under accession number DRA013077 (BioProject ID: PRJDB8332). A genome browser for A. tenuis is available from the Marine Genomics Unit web site (https://marinegenomics.oist.jp/). Results of statistical analyses for identify DEGs were provided in Supplementary Data S2. Normalized expression data (TMM-normalized CPM) was provided in Supplementary Data S3.