Dear editor,

Spontaneous pneumomediastinum (SPM, also known as Hamman’s syndrome) is an uncommon finding. SPM is induced without any comorbidities and is secondary to underlying factors, such as smoke, asthma, esophageal rupture, or labor and delivery.[1,2] The frequency of idiopathic pneumomediastinum is 1 of 32,000 hospitalized persons.[3] Awareness of SPM and appropriate examination play a key role in the early diagnosis and intervention for SPM to avoid potentially serious complications. SPM in diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA) has been described in several case reports.[4-6] However, most data are described from isolated cases, and these cases have varying clinical symptoms. This study presents a case series of ten patients diagnosed with SPM complicating DKA to assess their characteristics, treatment, and prognosis.

CASE

We retrospectively included patients diagnosed with SPM complicating DKA between March 2012 and June 2021. Demographics data, radiological features, treatment, and prognosis were collected and analyzed.

DKA was defined as glucose >11 mmol/L, pH <7.30 or bicarbonate <15 mmol/L, and ketonuria. All cases were confirmed to have subcutaneous emphysema or pneumomediastinum by chest computed tomography (CT). Patients with SPM secondary to thoracic injury, surgery, invasive procedures, or invasive examinations for the upper gastrointestinal tract were excluded.

During the 9-year period, a total of 747 patients diagnosed with DKA were admitted to our center. Approximately 86% (n=642) of the patients had chest CT examinations because of extension assessment and respiratory symptoms. A total of 10 cases met our criteria and were included in the analysis. The clinical characteristics of them are presented in Table 1. The average age of the cohort was 25.9 years with a range of 15 to 39 years, and eight patients were male.

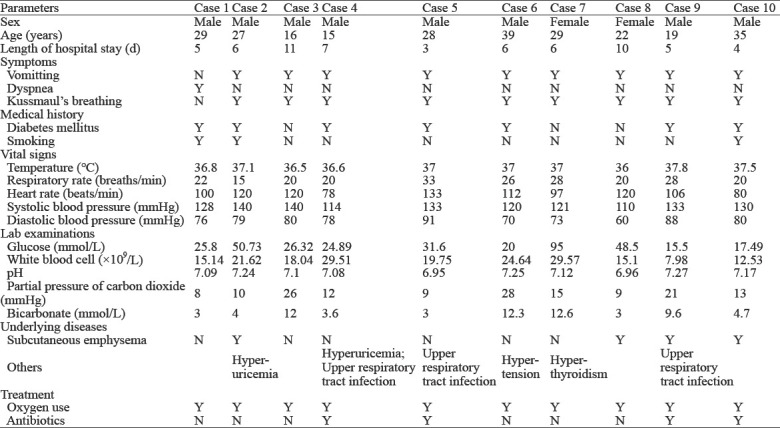

Table 1.

The clinical characteristics of patients with spontaneous pneumomediastinum complicating diabetic ketoacidosis

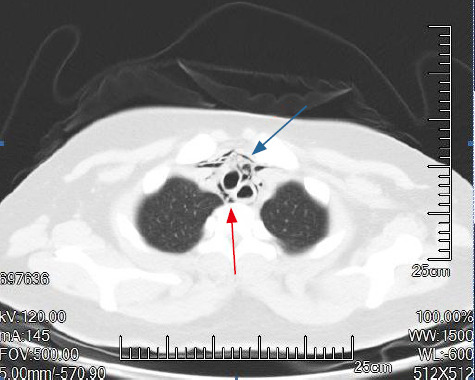

All cases were confirmed to have pneumomediastinum (Figure 1, as red arrow showed) and three cases showed subcutaneous emphysema (Figure 1, as blue arrow showed). In addition, seven patients had a history of diabetes mellitus, and three patients had a smoking habit. The initial symptoms included vomiting (n=9), dyspnea (n=1), and Kussmaul’s respiration (n=9). On physical examination, the following vital sign information was recorded: respiratory rate 23.2±5.1 breaths/min; heart rate 106.6±17.1 beats/min; temperature 36.9±0.5 °C; and systolic/diastolic blood pressure 126.9±9.8/77.5±8.3 mmHg (1 mmHg=0.133 kPa).

Figure 1.

Chest CT of a patient with Hamman’s syndrome. Pneumomediastinum (red arrow); subcutaneous emphysema (blue arrow).

Ketonuria was detected in all cases. Laboratory examinations revealed a pH of 7.1±0.1 and a white blood cell count (WBC) of 19.3×1010/L. Plasma glucose and bicarbonate levels were 35.8±22.8 mmol/L and 6.7±4.0 mmol/L, respectively. The underlying diseases included hypertension (n=1) and hyperthyroidism (n=1). All cases were treated with conserved therapy, including oxygen therapy (n=10) and antibiotics (n=3). The period between symptom initiation and complete recovery was 6.3±2.3 d. Complete resolution was confirmed in all cases by a follow-up chest CT (Figure 2). In addition, there were no sequelae and no recurrence in all patients.

Figure 2.

Chest CT of the recovered patient with Hamman’s syndrome.

DISCUSSION

Pneumomediastinum is a rare complication in DKA that was first reported in 1819 and further characterized by Hamman in 1939.[7] Pneumomediastinum is described as air accumulation within the mediastinum, which can be primary or secondary to other diseases (such as trauma and respiratory diseases). The process is usually self-resolving.

The precise etiology of DKA is not yet fully explained. However, DKA has been proposed as a trigger for numerous pathological conditions. Physiologically, pressure in the mediastinum is lower than alveolar pressure. However, Kussmaul’s breathing is associated with DKA’ status. Therefore, Kussmaul’s breathing was considered to play a role in developing pneumomediastinum.[8] High intrathoracic pressure caused by Kussmaul’s breathing leads to alveoli overdistension and rupture. Air can then leak and track to the mediastinum.[5,7] DKA is also associated with severe vomiting due to acidosis, and vomiting also increases the intrathoracic pressure. [4] Air can then track to the subcutaneous tissues, and subcutaneous emphysema occurs.

SPM presents with various symptoms, such as retrosternal chest pain, neck pain, dyspnea, dysphagia, and facial swelling.[9] In our cases, vomiting was the most common symptom of SPM at admission. All ten patients had pneumomediastinum, but only three cases showed subcutaneous emphysema. However, in another study, the majority of patients with SPM had subcutaneous emphysema (65%), followed by pneumomediastinum (52%) and pneumothorax (11%).[10] Leucocytosis was reported in 80% of patients without any evidence of infection.[9] Consistent with this result, the mean peripheral WBC in our study was at 19.3×1010/L (normal range [4–10]×1010/L).

According to DKA guidelines, high dose fixed-rate insulin is advocated to reverse ketoacidosis quickly, because this would reduce the use of compensatory hyperventilation and antiemetics among DKA patients for managing vomiting.[11] After correcting acidosis and vomiting, the pathological collection of air is gradually reabsorbed.[12,13] Therefore, the treatment for this condition is mainly supportive.

SPM often follows a benign course, and most patients diagnosed with the uncomplicated form of SPM can be managed conservatively. However, occasional complications are encountered, including Boerrhave’s syndrome, pneumothorax requiring intervention, pneumopericardium, and cardiac tamponade.[14-17] Oxygen leads to the rapid absorption of air leaks from an increased nitrogen diffusion.[16,17] In our cases, oxygen therapy was routinely used. However, the possible underlying disease should be treated to prevent recurrence or potential complications. SPM resolves with conservative measures with a satisfactory clinical outcome, and has a very low recurrence rate. In a retrospective study, no recurrence was reported during a 24-month follow-up period.[9] A follow-up radiological investigation was not recommended, unless patients had symptoms of recurrence or complications.[18] Notably, the outcome is not always favorable as fatal complications may occur. A previous study showed that SPM could be fatal and approximately 25% of undiagnosed patients die within two months.[19] This strengthens the value of chest CT in such cases.

CONCLUSIONS

Although SPM is a rare symptom, emergency physicians should consider SPM during assessing patients with DKA. Clinical suspicion is required for early diagnosis and prevents further complications, favoring a good outcome.

Footnotes

Funding: None.

Ethical approval: This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the First Affiliated Hospital, Jilin University. Written informed consent from patients was waived because of the retrospective design and the anonymous nature of data collection.

Conflicts of interests: The authors indicated no potential conflicts of interests.

Contributors: WLX and LCS collected the patient’s clinical data, and wrote the paper. XXZ designed the study. HW and WL carried out the medical images collection and revised. WLX and LCS contributed equally to this study. All authors have read and approved the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Zapardiel I, Delafuente-Valero J, Diaz-Miguel V, Godoy-Tundidor V, Bajo-Arenas JM. Pneumomediastinum during the fourth stage of labor. Gynecol Obstet Invest. 2009;67(1):70–2. doi: 10.1159/000162103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mohamed W, Exley C, Sutcliffe IM, Dwarakanath A. Spontaneous pneumomediastinum (Hamman's syndrome):presenting as acute severe asthma. J R Coll Physicians Edinb. 2019;49(1):31–3. doi: 10.4997/JRCPE.2019.106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Abolnik I, Lossos IS, Breuer R. Spontaneous pneumomediastinum:a report of 25 cases. Chest. 1991;100(1):93–5. doi: 10.1378/chest.100.1.93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pain AR, Pomroy J, Benjamin A. Hamman's syndrome in diabetic ketoacidosis. Endocrinol Diabetes Metab Case Rep. 2017;2017:17–0135. doi: 10.1530/EDM-17-0135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kamei S, Kaneto H, Tanabe A, Shigemoto R, Irie S, Hirata Y, et al. Hamman's syndrome triggered by the onset of type 1 diabetes mellitus accompanied by diabetic ketoacidosis. Acta Diabetol. 2016;53(6):1067–8. doi: 10.1007/s00592-016-0871-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hamamoto H, Sakaguchi K, Muro S, Sasaki K, Kobayashi S, Fujisawa T, et al. A case of Hamman's syndrome associated with acute-onset type 1 diabetes mellitus presenting with abdominal pain. Nihon Shokakibyo Gakkai Zasshi. 2015;112(5):856–62. doi: 10.11405/nisshoshi.112.856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hamman L. Spontaneous mediastinal emphysema. Bull Johns Hopkins Hosp. 1939;64:1–21. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hirayama I, Hiruma T, Ueda Y, Doi K, Nakajima S. Hamman syndrome:pneumomediastinum combined with hyperosmolar hyperglycemic state. Am J Emerg Med. 2016;34(10):205.e1–2058.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2016.03.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Takada K, Matsumoto S, Hiramatsu T, Kojima E, Watanabe H, Sizu M, et al. Management of spontaneous pneumomediastinum based on clinical experience of 25 cases. Respir Med. 2008;102(9):1329–34. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2008.03.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Panacek EA, Singer AJ, Sherman BW, Prescott A, Rutherford WF. Spontaneous pneumomediastinum:clinical and natural history. Ann Emerg Med. 1992;21(10):1222–7. doi: 10.1016/s0196-0644(05)81750-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wolfsdorf JI, Glaser N, Agus M, Fritsch M, Hanas R, Rewers A, et al. ISPAD Clinical Practice Consensus Guidelines 2018:Diabetic ketoacidosis and the hyperglycemic hyperosmolar state. Pediatr Diabetes. 2018;19(Suppl 27):155–77. doi: 10.1111/pedi.12701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Makdsi F, Kolade VO. Diabetic ketoacidosis with pneumomediastinum:a case report. Cases J. 2009;2:8095. doi: 10.4076/1757-1626-2-8095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Marchon KA, Nunn MO, Chakera AJ. Images of the month:an incidental finding of spontaneous pneumomediastinum (Hamman's syndrome) secondary to diabetic ketoacidosis during the coronavirus pandemic. Clin Med (Lond) 2020;20(6):e275–7. doi: 10.7861/clinmed.2020-0739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shaker H, Elsayed H, Whittle I, Hussein S, Shackcloth M. The influence of the 'golden 24-h rule'on the prognosis of oesophageal perforation in the modern era. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2010;38(2):216–22. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcts.2010.01.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Newcomb AE, Clarke CP. Spontaneous pneumomediastinum:a benign curiosity or a significant problem? Chest. 2005;128(5):3298–302. doi: 10.1378/chest.128.5.3298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sahni S, Verma S, Grullon J, Esquire A, Patel P, Talwar A. Spontaneous pneumomediastinum:time for consensus. N Am J Med Sci. 2013;5(8):460–4. doi: 10.4103/1947-2714.117296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cicak B, Verona E, Mihatov-Stefanović I, Vrsalović R. Spontaneous pneumomediastinum in a healthy adolescent. Acta Clin Croat. 2009;48(4):461–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gasser CR, Pellaton R, Rochat CP. Pediatric spontaneous pneumomediastinum:narrative literature review. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2017;33(5):370–4. doi: 10.1097/PEC.0000000000000625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ma XL, Chen ZY, Hu W, Guo ZW, Wang Y, Kuwana M, et al. Clinical and serological features of patients with dermatomyositis complicated by spontaneous pneumomediastinum. Clin Rheumatol. 2016;35(2):489–93. doi: 10.1007/s10067-015-3001-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]