Abstract

Background

The coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic spread to >200 countries in <6 months. To understand coronavirus spread, determining transmission rate and defining factors that increase transmission risk are essential. Most cases are asymptomatic, but people with asymptomatic infection have viral loads indistinguishable from those in symptomatic people, and they do transmit severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2). However, asymptomatic cases are often undetected.

Methods

Given high residence hall student density, the University of Colorado Boulder established a mandatory weekly screening test program. We analyzed longitudinal data from 6408 students and identified 116 likely transmission events in which a second roommate tested positive within 14 days of the index roommate.

Results

Although the infection rate was lower in single-occupancy rooms (10%) than in multiple-occupancy rooms (19%), interroommate transmission occurred only about 20% of the time. Cases were usually asymptomatic at the time of detection. Notably, individuals who likely transmitted had an average viral load approximately 6.5-fold higher than individuals who did not (mean quantification cycle [Cq], 26.2 vs 28.9). Although students with diagnosed SARS-CoV-2 infection moved to isolation rooms, there was no difference in time to isolation between cases with or without interroommate transmission.

Conclusions

This analysis argues that interroommate transmission occurs infrequently in residence halls and provides strong correlative evidence that viral load is proportional to transmission probability.

Keywords: asymptomatic transmission, COVID-19, SARS-CoV-2, viral load

Although most carriers of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 are asymptomatic, they are understudied compared with symptomatic patients. Test data from university students revealed a 20% transmission rate between roommates. In those who transmitted infection, viral load was 6.5-fold higher than in those who did not.

By early July 2021, >4 million people worldwide had died of coronavirus disease-19 (COVID-19), caused by the novel coronavirus severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2) [1, 2]. Because COVID-19 is an airborne respiratory disease, households are at elevated risk due to close personal contact and a shared environment. However, secondary attack rates are estimated at 17%, indicating that many households do not experience spread [3]. The factors underlying this variable transmission risk are under intense scrutiny. Importantly, viral load, which spans 6 orders of magnitude or more [4–6], is emerging as an important transmission risk factor [7].

To date, most transmission studies have focused primarily on symptomatic index cases, particularly hospitalized individuals. In contrast, asymptomatic infections are typically underreported due to lack of overt illness to reveal them and inadequate testing resources to look for them. Given the many variables associated with determining the asymptomatic infection rate, including evolving symptom definition, demographic characteristics, study population size, and testing penetrance, estimates of the asymptomatic fraction vary substantially. However, studies with high testing penetrance or incorporation of large-population serologic data indicate that 40%–90% of cases may be asymptomatic [4, 8–10]. Importantly, asymptomatic infected individuals still transmit virus and have viral loads equivalent to those in symptomatic individuals yet are expected to be more mobile because they are not experiencing illness [6, 8, 11, 12]. Modeling studies also indicate that asymptomatic transmission is likely a significant contributor to the COVID-19 pandemic spread [10, 13]. This conflicts with a meta-analysis of household transmission, which included 4 reports describing asymptomatic transmission and concluded that secondary attack rates were higher from symptomatic index cases [3]. Therefore, in investigating SARS-CoV-2 transmission, it is critical to study this potentially large reservoir of viral carriers in a population participating in regular asymptomatic testing.

University residence hall roommates are an example of dense households, typically with shared bedrooms, bathrooms, and dining facilities. Moreover, they are also a young adult population with a higher likelihood of being asymptomatic and lower rates of comorbid conditions linked to severe disease [4, 9, 14]. Thus, they are ideal for investigating the extent of transmissibility from asymptomatic or mildly symptomatic cases.

During the fall 2020 semester, the University of Colorado Boulder (CU Boulder) followed a traditional model of on-campus living, including roommate pairing. This was accompanied by a comprehensive student-centered public health system. Aggressive screening with a quantitative molecular assay and a robust track/trace/isolate system allowed us to examine the factors that may influence transmissibility in a household, particularly from asymptomatic individuals. Therefore, we determined (1) the extent of roommate transmission, (2) the contribution of viral load to transmission likelihood, and (3) the impact of time spent cohoused while infected.

METHODS

Expanded Methods are available in the Supplementary Data.

CU Boulder Public Health Operations

Daily Symptom Monitoring and Reporting

Residence hall students were required to answer an online daily health questionnaire that assessed whether they had any symptoms consistent with COVID-19. Those who reported symptoms were directed to immediately contact the CU Public Health Clinic.

Quantitative Reverse-Transcription Polymerase Chain Reaction Screening

Asymptomatic residence hall students were required to test weekly. Testing staff confirmed that students completed the health questionnaire before giving their saliva sample. The saliva-based quantitative reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR) screening test was developed at CU Boulder and is described in detail elsewhere, including primer and probe sequences and fluorophores along with example standard curves [6].

Diagnostic RT-qPCR Testing

Diagnostic RT-qPCR testing was available at the on-campus Public Health Clinic through Student Health Services. The Lyra Direct SARS-CoV-2 Assay (Quidel; M124) was used according to the emergency use authorization. The test audience included presumptive positive students referred from screening, symptomatic students, and students identified through contact tracing. The time to result for both screening and diagnostic testing was 24–36 hours.

Isolation Protocol

Students identified as SARS-CoV-2 positive were moved into isolation accommodations for 10 days, in accordance with Centers for Disease Control (CDC) and Prevention recommendations [15]. They either isolated in dedicated residence halls with rooms containing en suite bathrooms or were allowed to isolate off site if they lived within a 250-mile radius.

Data Collection

SARS-CoV-2 test data, housing assignments, and isolation data were collected through the campus COVID-19 operational activities, and data were all stripped of identifying information before analysis. Data were analyzed and are reported here in aggregate. This does not meet the definition of human subject research described in US Health and Human Services 45 Code of Federal Regulations, part 46. For this reason, this study did not fall under institutional review board purview.

Data Analysis

Fraction of Required Tests

Students with diagnosed COVID-19 were exempt from the required weekly screening test for the rest of the semester. We determined the number of required tests adjusted to their detection date if they did test positive. We then calculated the fraction of required tests each student completed. We assessed the statistical significance of differences in test compliance between students in single-occupancy rooms and those in multiple-occupancy rooms using unpaired t tests, and we further compared the groups using a violin plot, displaying medians and interquartile ranges (IQRs).

In-Room Transmission

For students identified as positive, we determined the first date of detection by compiling all positive records from both screening and diagnostic testing. We used this date to calculate the detection interval between positive roommate pairs and the minimum amount of time spent in a room while positive before moving to isolation. To determine transmission likelihood, we defined likely transmission as 2 positive roommates identified within a 1–14-day range. We based this on what is known regarding viral latency, detection thresholds, and the weekly screening cadence. This interval also informs the quarantine time after exposure recommended by the CDC [15].

Viral Load

With the quantitative data from the screening test, we analyzed the lowest quantification cycle (Cq) recorded in each multiple-occupancy room as a surrogate for the highest viral load. We compared the mean Cq in the likely transmission to the unlikely transmission group. We assessed statistical significance of the mean Cq difference using unpaired t tests and further compared the groups using a violin plot, displaying medians and IQRs. Supplementary Table 1 presents individual Cq values for each index case. Cq data were unavailable for the diagnostic test.

Time to Isolation

To determine time to isolation, we calculated the difference between the first date of detection for the index case and the date that student entered isolation. Isolation data were not available for every student. We analyzed the time distributions of the likely and unlikely transmission groups by permutation hypothesis testing with R software [16], permuting the random data set 100 000 times. The P value was based on the difference in means between the experimental and the permutation data set. We also analyzed isolation kinetics with a Kaplan-Meier curve followed by a Gehan-Breslow-Wilcoxon test. Supplementary Table 2 presents times for each index case.

Logistic Regression

We assessed SARS-CoV-2 transmission as a function of viral load and the amount of time an index patient spent with their roommate using logistic regression. Using R software, we fit the logistic regression model to a subset of index cases for whom we had both Cq and time to isolation information (Supplementary Table 3 contains source data). To determine whether there was an interaction between viral load and time, we repeated the analysis with an interaction term added.

RESULTS

CU Boulder established a multifaceted, self-contained public health system (fully described in the Supplementary Data). This included daily symptom reporting and mandatory weekly testing with a screening RT-qPCR test. The first residence hall cases were detected on 24 August, and 1058 positive residential students were ultimately identified by the time of residence hall closure on 25 November, representing 16.5% of the 6408 residential students. Many residence hall cases originated off campus, based on case investigation and contact tracing. However, residence hall cases may also have resulted from interroommate transmission. Based on screening and on-campus diagnostic testing, we analyzed SARS-CoV-2 transmission in residence halls.

Lower Infection Rate in Single-Occupancy Rooms

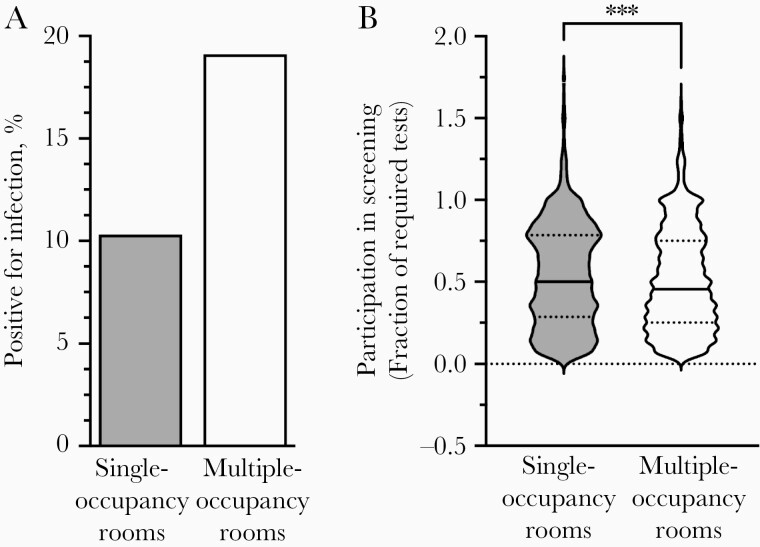

We first examined whether students living alone became infected at different rates than students with roommates. Approximately 30% of the 6408 residential students lived in single-occupancy rooms (1916 students) and 70% in multiple-occupancy rooms (4492 students in 2230 rooms). We detected 198 cases in single-occupancy rooms (10.3%) but 860 cases (19.1%) among students in multiple-occupancy rooms (Figure 1A, Figure 2, and Table 1). To determine whether this was due to a testing bias toward students in multiple-occupancy rooms, we calculated the fraction of required weekly tests on record for each student. Students in single rooms actually tested at a slightly higher frequency than those in multiple-occupancy rooms (mean [standard error of the mean] for students in single vs those in multiple-occupancy rooms, 0.54 [0.0073] vs 0.51 [0.0048]) (Figure 1B). Test frequency bias is therefore unlikely to be responsible for the higher observed cumulative positivity among students in multiple-occupancy rooms.

Figure 1.

Students in multiple-occupancy rooms were infected at twice the rate of students in single-occupancy rooms. A, A total of 198 students in 1916 single rooms (10.3%) were infected, as were 860 of 4492 students in multiple-occupancy rooms (19.1%). B, The mean and median fractions of required tests were modestly higher for students in single rooms (n = 1872) than for those in multiple-occupancy rooms (n = 4353). Violin plots reveal medians (solid lines) and interquartile ranges (dotted lines). ***P < .001 (unpaired t tests comparing means). A small set of students did not have a screening test on record or tested much more frequently than required.

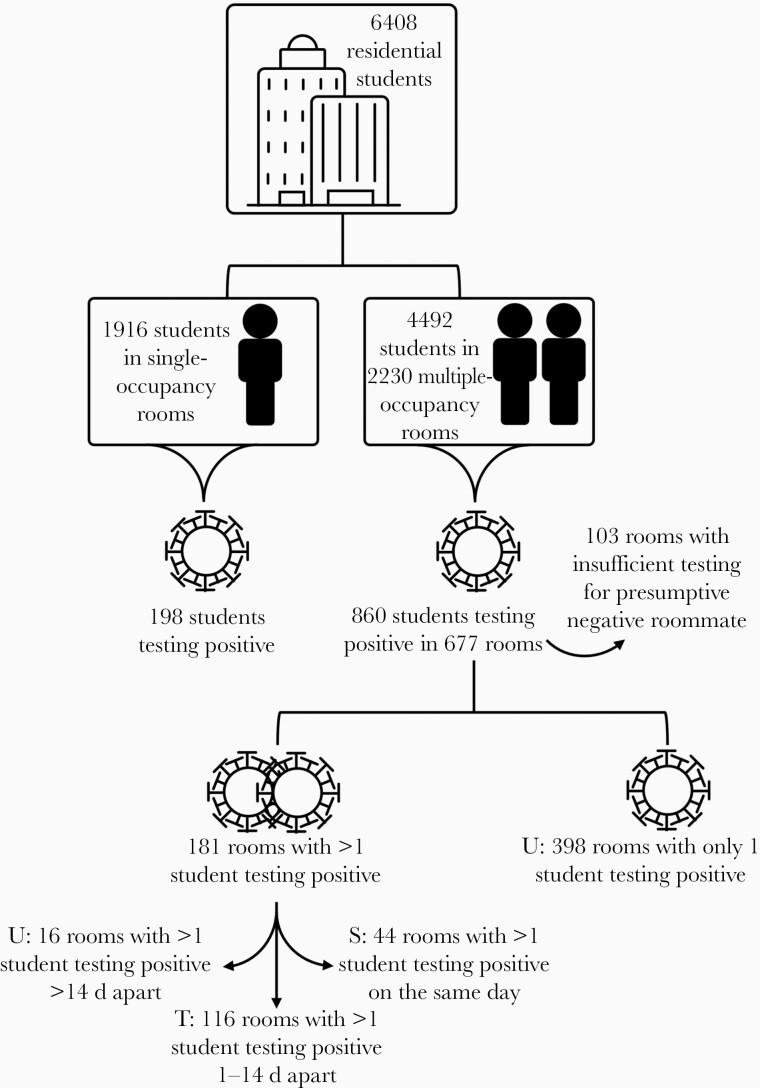

Figure 2.

Illustration of logic for identifying rooms with and without potential in-room transmission and determining infection patterns in residence hall students. “U” indicates unlikely in-room transmission; “T”, likely in-room transmission; and “S”, likely simultaneous infection from an external source.

Table 1.

Population Characteristics

| Category | Category Description | Students or Rooms, No. (%) | Fraction Calculated to Obtain % (Description) |

|---|---|---|---|

| A | Total residential students | 6408 (100) | … |

| B | Total students living in single-occupancy rooms | 1916 (29.9) | B/A (fraction of residential students living in single-occupancy rooms) |

| C | Total students living in multiple-occupancy rooms | 4492 (70.1) | C/A (fraction of residential students living in multiple-occupancy rooms) |

| D | Total residential students testing positive | 1058 (16.5) |

D/A (fraction of residential population with SARS-CoV-2 infection detected) |

| E | Students testing positive in single-occupancy rooms | 198 (10.3) | E/B (fraction of students living in single-occupancy rooms who tested positive) |

| F | Students testing positive in multiple-occupancy rooms | 860 (19.1) | F/C (fraction of students living in multiple-occupancy rooms who tested positive) |

| G | Total occupied rooms | 4146 (100) | … |

| H | Total single-occupancy rooms | 1916 (46.2) | H/G (fraction of occupied rooms that are single-occupancy) |

| I | Total multiple-occupancy rooms | 2230 (53.8) | I/G (fraction of occupied rooms that are multiple-occupancy) |

| J | Rooms with ≥1 student testing positive | 875 (21.1) | J/G (fraction of occupied rooms with ≥1 infected students) |

| K | Single-occupancy rooms with a student testing positive | 198 (22.6) | K/J (fraction of rooms with a student testing positive that are single-occupancy) |

| L | Multiple-occupancy rooms with ≥1 student testing positive | 677 (77.4) | L/J (fraction of rooms with ≥1 infected students that are occupied by >1 student) |

| M | Rooms with multiple students testing positive | 181 (26.7) | M/L (fraction of multiple-occupancy rooms with >1 infected student) |

| N | Rooms with multiple students testing positive on the same day | 44 |

… |

| O | Rooms with multiple students testing positive >14 d apart | 21 |

… |

| P | Multiple-occupancy rooms with only 1 student testing positive | 496 |

… |

| Q | Rooms from (P) where presumptive negative roommate has an insufficient testing record | 98 |

… |

| R | Rooms from (O) where presumptive negative roommate has an insufficient testing record | 5 |

… |

| S | All rooms from (P) excluded from analysis (Q + R) | 103 |

… |

| T | Multiple-occupancy rooms with ≥1 student testing positive and a sufficient testing record to assess transmission (L − S) | 574 |

… |

| U | Rooms with multiple students testing positive likely infected externally and simultaneously (N) | 44 (7.7) | U/T (fraction of multiple-occupancy rooms with >1 infected student that do not likely represent in-room transmission) |

| V | Rooms with potential in-room transmission (M − N − O) | 116 (20.2) | V/T (fraction of multiple-occupancy rooms with >1 infected student with likely in-room transmission) |

| W | Rooms with sufficient testing record with unlikely in-room transmission (P − S), 1 student testing positive | 398 |

… |

| X | Rooms with multiple students testing positive detected >14 d apart and with likely cohabitation during infectious period for index case (O − R) | 16 |

… |

| Y | Rooms with sufficient testing record with unlikely in-room transmission (W + X) | 414 (72.1) | Y/T (fraction of multiple-occupancy rooms with 1 infected student detected and sufficient testing record of roommate pair: unlikely in-room transmission) |

Abbreviation: SARS-CoV-2, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2.

Low Rates of Roommate Transmission

To examine whether interroommate transmission accounted for the higher cumulative incidence in multiple-occupancy rooms, we investigated whether the timing of cases supported interroommate transmission (Figure 2 and Table 1; see Methods and Supplementary Data for the full process of identifying likely and unlikely cases of transmission). A total of 116 rooms fit our definition of likely transmission, and 87% of transmission cases were detected within 1 week of index case identification (Supplementary Figure 1).

A total of 496 multiple-occupancy rooms had only 1 student testing positive per room. We analyzed the test history of the roommates of index cases to ensure that there was a negative test on record within 3 weeks of detecting the index case and found 398 rooms where the roommate of the index case never tested positive. We also found 16 rooms with 2 widely spaced infections (>14-day separation) that likely resulted from 2 independent external exposures. In total, in 414 cases there was no apparent interroommate transmission.

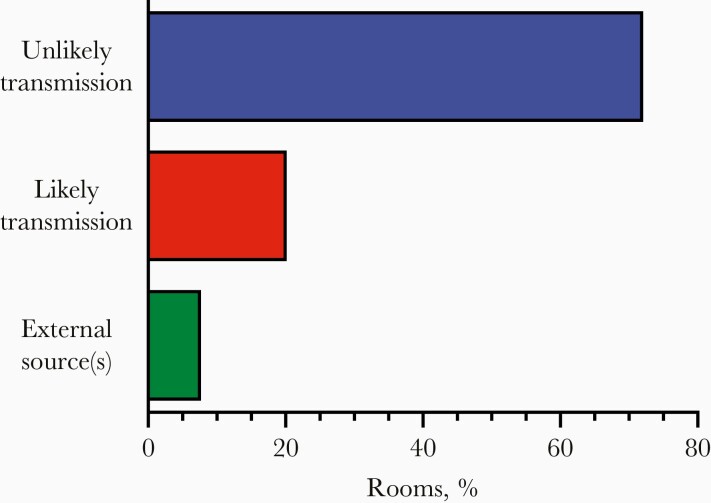

Overall, of 574 multiple-occupancy rooms with ≥1 student testing positive and a sufficient testing record, 7.7% had multiple positive cases detected simultaneously and likely due to external exposures of both roommates, 20.2% had likely in-room transmission, and 72.1% did not appear to have transmission events despite close contact during the infectious period (Figure 3). Thus, roommate-to-roommate transmission is not the primary reason that positive cases occurred nearly twice as frequently among students in multiple-occupancy rooms compared with those in single rooms (Figure 1).

Figure 3.

Most multiple-occupancy rooms with an infected student did not have interroommate transmission: 574 rooms housed students with a testing record sufficient to evaluate potential transmission, 44 (7.7%) had multiple students testing positive who were likely infected simultaneously by external sources, 116 (20.2%) had likely in-room transmission from one roommate to another (infections detected within a 2-week period but not on the same day), 398 had only 1 infected student and ≥1 closely spaced downstream negative test on record for the roommate, and 16 had 2 widely spaced infections with clear presence of the second student in the room during the infectious period for the index case (72.1% unlikely transmission).

In sensitivity analyses, we explored whether the estimated 20.2% in-room transmission could be higher or lower by considering: (1) the possibility that same-day roommate detections actually did represent transmission, (2) the possibility that 2 infections detected 1 or 2 days apart did not represent transmission, (3) the likelihood that 2 infections from 2 independent exposures appeared in the same room simply by chance, and (4) the potential that a midsemester remote learning period could have prevented some transmission events (see Supplementary Data). Across these additional analyses, we find that asymptomatic transmission remains low probability, with only 16%–28% of index cases transmitting to their roommate.

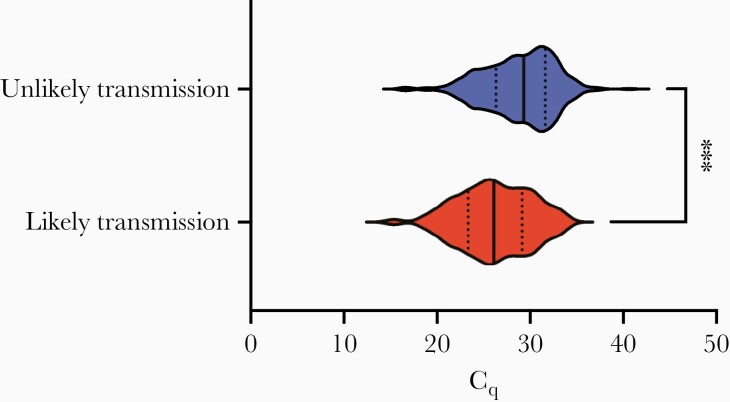

Viral Loads in Infected Students

One factor that could have contributed to a low secondary attack rate is viral load diversity. To measure viral load, we analyzed the Cq of viral E gene RNA in the screening RT-qPCR test as a proxy for viral genomes. We compared the lowest Cq on record for each room in both the likely and unlikely transmission groups. Cq values indicate the amplification rounds necessary to reach detection, so higher Cq values indicate lower viral loads and each whole unit is a factor of 2 in RNA copies per milliliter. This analysis showed that the average viral load was 6.5-fold higher in rooms with likely transmission (mean Cq [standard error of the mean], 26.2 [0.43]) than in rooms without transmission (mean Cq, 28.9 [0.20]; see Figure 4). The difference in median (IQR) between groups was similar (likely transmission, 26.11 [23.36–29.13]; unlikely transmission, 29.32 [26.34–31.64]). This striking difference between groups indicates that individuals with higher viral load may produce a higher infectious dose for their contacts, raising the risk of infection accordingly.

Figure 4.

Rooms with transmission had higher viral load. Comparison of the lowest quantification cycle Cq values on record in multiple-occupancy rooms with likely (n = 80) or unlikely transmission (n = 366) for students detected through the screening program. The significant difference between groups indicated a 6.5-fold higher average viral load in the group with transmission. Violin plots reveal medians (solid lines) and interquartile ranges (dotted lines). ***P < .001 (unpaired t test comparing means).

Across cases, viral loads spanned >7 orders of magnitude. The highest was found in the likely transmission group (Cq, 15.4), and the lowest in the unlikely transmission group (Cq, 40.6). The only cases with Cq values >34 (22 cases) were found in the unlikely transmission group.

The correlation between viral loads and transmission is notable, given that the weekly testing cadence typically allows for only 1 viral load measurement for each infected individual. Measurements could occur at different times over the course of infection, during which viral loads may vary greatly from one day to the next [5]. However, because our sample set comprises hundreds of identified infections, Cq values should be representative of the window during which individuals can test positive. Moreover, due to the regular screening program combined with high assay sensitivity, it is likely that most students were in the early stages of infection when their infection was detected. We found that 48% of students with unlikely transmission and 56% with likely transmission had a negative test result on record from the previous week, and these proportions increase to 81% and 78%, respectively, when considering a 2-week window. There was no significant difference in the distributions of most recent negative test dates between the 2 groups (2-sample Kolmogorov-Smirnov test, P = .62; D statistic = 0.093). As a result, the observed higher viral loads among transmitting roommate pairs are unlikely to be an artifact of biases in sampling times.

Time to Isolation for Infected Students

Increased exposure time is one of the factors used to identify at-risk close contacts and invoke quarantine protocols [15]. CU Boulder established dedicated isolation residence halls to temporarily rehouse infected students in an effort to reduce community spread, particularly among roommates. Isolation was not initiated until infection was confirmed by a diagnostic RT-qPCR test, leading to variation in the time before a student isolated. Therefore, we examined whether the amount of time an index case spent with a roommate while infected could have contributed to transmission risk.

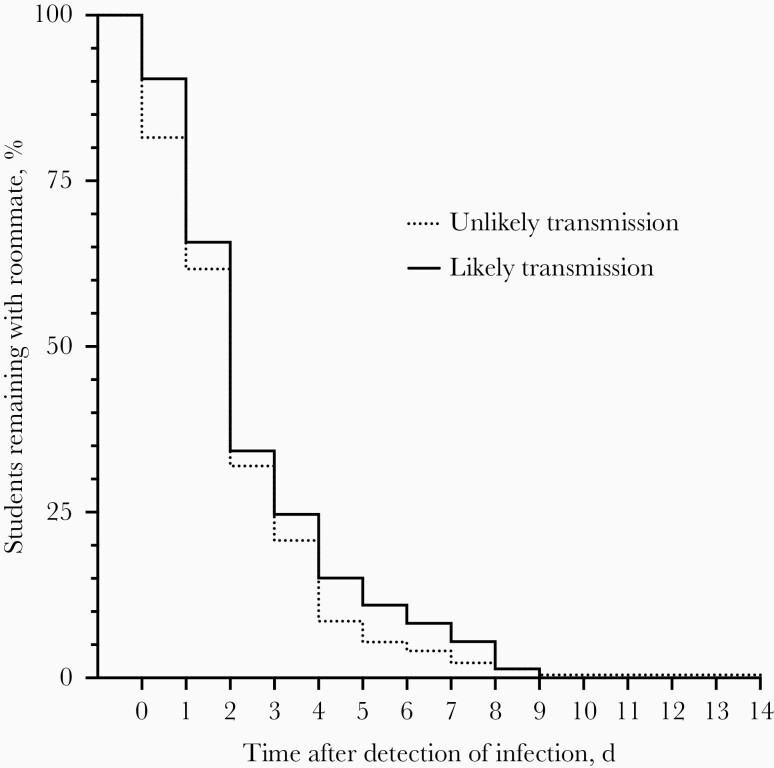

We found no difference in time to isolation between rooms with and rooms without transmission (permutation hypothesis test, P = .19). Furthermore, although 18.6% of cases with unlikely transmission entered isolation on the day infection was detected compared with only 9.6% of those with likely transmission, a Kaplan-Meier analysis of the time to isolation distributions indicated no significant difference between likely and unlikely transmission groups (Gehan-Breslow-Wilcoxon test, P = .26; Figure 5). While this does not negate the potential benefit of quickly isolating infected individuals from their households, it does indicate that a lag in time to isolation does not explain the transmissions we observed.

Figure 5.

There was no difference in isolation patterns between students with (n = 73) and rooms without (n = 222) likely transmission. Kaplan-Meier curves compare the percentage of students testing positive who remained with their roommate and the days since first detection; there is no significant difference between curves (P = .26 by Gehan-Breslow-Wilcoxon test).

Increasing Viral Load Increases the Transmission Risk

Although there was no difference in overall isolation patterns between the likely and unlikely transmission groups, we evaluated the concept of cumulative dose driving transmission. Using a generalized linear model to fit a logistic regression in a subset of cases for which we had both index case Cq and isolation information, we considered the effects of viral load and time to isolation (Table 2). We found an odds ratio of 0.86 (P < .001) for Cq, which indicates that for every 1-unit increase in Cq, the odds of transmission are reduced by approximately 14%. This is consistent with transmission risk decreasing as viral load decreases (increasing Cq). Analysis of time to isolation indicated that it was not a significant contributor (odds ratio, 1.155; P = .06) but suggested that increasing time in the room trends with elevated transmission risk. An interaction term added to the model was not statistically significant (Supplementary Table 4). Therefore, we conclude that viral load is an independent risk factor rather than cumulative exposure driven by the combination of viral load and time.

Table 2.

Logistic Regression Analysis of Association Between Index Case Variables and Transmission Outcome

| Variable | OR (95% CI) | P Value |

|---|---|---|

| Cq for index case | 0.86 (.79–.94) | <.001 |

| Days of cohousing after index case detection | 1.15 (.99–1.35) | .06 |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; Cq, quantification cycle; OR, odds ratio.

Discussion

This study revealed several key findings that help to identify which factors influence transmission from largely asymptomatic cases living in small, dense households. First, we observed a 2-fold higher positivity among students with roommates than those who live alone. However, this difference cannot be explained solely by interroommate transmission, as we estimate that occurred in only 20% of these multiple-occupancy rooms. Interestingly, behavioral studies have shown that people living alone have less frequent social contact than those who live in households and that roommates can exert peer effects with risky behaviors [17, 18]. Therefore, it may be that students living with roommates are at a higher risk of infection due to both higher levels of social contact outside the home and moderate levels of interroommate transmission within the home.

Second, a notable contribution of this work is to provide evidence that viral levels are positively correlated with the probability of transmission in the context of a high frequency screening program for asymptomatic young adults. We observed that students who transmitted SARS-CoV-2 to their roommates had, on average, 6.5-fold higher viral loads than students who did not transmit the virus (Figure 4). The relationship between viral load and transmission risk is a common hypothesis underpinning COVID-19 transmission modeling studies [19, 20]. This is also supported by recent analyses of symptomatic cases, including one finding that viral loads >1 × 1010 copies/mL were associated with double the rate of transmission (24%) of viral loads <1 × 106 copies/mL [7, 21]. Our study brings new evidence from 579 concordant and discordant sets of primarily asymptomatic young adults undergoing regular RT-qPCR testing. We suggest that a key parameter in transmission is the viral load of the index case. We note that this study period precedes widespread US circulation of SARS-CoV-2 variants B.1.1.7 (alpha), B.1.351 (beta), P.1 (gamma), and B.617.2 (delta), which could have different transmission dynamics and virulence.

Importantly, our study population was largely asymptomatic; this population is a continued concern as a COVID-19 transmission source and yet is relatively understudied compared with symptomatic, often hospitalized, patients. For example, in a recent meta-analysis of 79 studies, 73 focused on hospitalized patients [12]. However, the majority of SARS-CoV-2–infected individuals appear to be asymptomatic [4, 8–10]. We were able to identify asymptomatic infected individuals due to a mandatory weekly screening program for all residential students and robust contact tracing, both coupled to on-campus diagnostic testing. The majority of students were asymptomatic at the time of first detection. There is speculation that asymptomatic individuals who test positive for SARS-CoV-2 infection may shed less live virus than symptomatic patients and that RNA levels are not always a reliable surrogate for live virus, which is not routinely isolated and quantified. That extends to the argument that asymptomatic infections contribute less to viral transmission. However, we found transmission rates similar to studies involving mostly symptomatic populations, supporting the idea that asymptomatic infected individuals can transmit as efficiently as symptomatic individuals [3, 10]. This is strengthened by the observation that viral loads are similar between symptomatic and asymptomatic individuals [4, 6].

The large fraction of rooms that did not experience transmission is encouraging, as roommate pairing could support positive mental health, particularly with restricted in-person socialization opportunities. In fact, the Georgia Institute of Technology, with a residence hall population comparable to that of CU Boulder, offered its students the opportunity to leave their roommates and move into single rooms after they detected a wave of cases. However, many elected to stay cohoused for mental health reasons, despite a 30% secondary attack rate between roommates [22]. Furthermore, a study of 13 US colleges and universities with mandatory screening programs found no correlation between residence hall density and the fraction of students infected in the fall 2020 semester, consistent with primarily off-campus origins of cases [23].

In contrast to the importance of viral load, we did not observe a significant difference in isolation dynamics between the likely and unlike transmission groups. This does not mean that isolation has no effect on preventing transmission. Compared to the 20% secondary attack rate we saw among roommates, the secondary attack rate within households is reported to be 38% between spouses but 18% between nonspouse household members [3]. The reasons for this difference are unknown, but spouses likely spend more time in close contact with each other, including sleeping in the same room. This suggests that transmission between residence hall roommates could have been higher in the absence of off-site isolation. Even so, logistic regression analysis of index case Cq and time to isolation indicated that increasing viral load was the dominant risk factor for transmission in this population, despite a trend toward elevated risk associated with prolonged time in the room.

Given the many unknowns surrounding an emergent disease, concerns regarding the safety of roommate pairing were justifiable early in the pandemic. However, in addition to mental health benefits, roommate pairing permits higher-density on-campus presence, which is valuable for students who benefit from in-person instruction and added university support services, or who may experience housing, food, or financial insecurities at their permanent residence. Our study adds reassurance that roommate pairing is relatively safe. This is qualified by the finding that asymptomatic individuals with high viral loads do pose a transmission risk. Therefore, quantitative tests than can efficiently identify these cases could help prioritize downstream measures, such as isolation protocols, contact tracing, and quarantine advice for close contacts, particularly because it is estimated that 80% of secondary transmission events originate from about 10% of infected individuals [24]. Those with the highest viral load could represent potential superspreaders, and efficiently identifying them could help prevent large outbreaks.

Supplementary Data

Supplementary materials are available at The Journal of Infectious Diseases online. Consisting of data provided by the authors to benefit the reader, the posted materials are not copyedited and are the sole responsibility of the authors, so questions or comments should be addressed to the corresponding author.

Notes

Acknowledgments. We are grateful to Carolyn Decker for developing the reliable and sensitive quantitative reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction screening test on which the screening program at the University of Colorado Boulder (CU Boulder) was built. We also thank CU leadership, the Scientific Steering Committee, and the Pandemic Response Office for institutional support and scientific guidance that allowed the university to remain operational. Finally, we acknowledge the CU Boulder student body for persevering through an unprecedented college semester and participating in the CU public health system.

We dedicate this work to the memory of Denise Muhlrad, who was essential in establishing the screening program despite the many challenges a pandemic presents.

Financial support. This work was supported by US government Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act funding to CU Boulder.

Potential conflicts of interest. T. K. S., E. L., and P. K. G. are cofounders of TUMI Genomics, and R. P. is a cofounder of Faze Medicines; both companies offer commercial severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 testing. All other authors report no potential conflicts. All authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. Conflicts that the editors consider relevant to the content of the manuscript have been disclosed.

Contributor Information

Kristen K Bjorkman, BioFrontiers Institute, University of Colorado Boulder, Boulder, Colorado, USA.

Tassa K Saldi, BioFrontiers Institute, University of Colorado Boulder, Boulder, Colorado, USA.

Erika Lasda, BioFrontiers Institute, University of Colorado Boulder, Boulder, Colorado, USA.

Leisha Conners Bauer, Health Promotion, University of Colorado Boulder, Boulder, Colorado, USA.

Jennifer Kovarik, Health Promotion, University of Colorado Boulder, Boulder, Colorado, USA.

Patrick K Gonzales, BioFrontiers Institute, University of Colorado Boulder, Boulder, Colorado, USA.

Morgan R Fink, BioFrontiers Institute, University of Colorado Boulder, Boulder, Colorado, USA.

Kimngan L Tat, BioFrontiers Institute, University of Colorado Boulder, Boulder, Colorado, USA.

Cole R Hager, BioFrontiers Institute, University of Colorado Boulder, Boulder, Colorado, USA.

Jack C Davis, BioFrontiers Institute, University of Colorado Boulder, Boulder, Colorado, USA; Department of Molecular, Cellular, and Developmental Biology, University of Colorado Boulder, Boulder, Colorado, USA.

Christopher D Ozeroff, BioFrontiers Institute, University of Colorado Boulder, Boulder, Colorado, USA; Department of Molecular, Cellular, and Developmental Biology, University of Colorado Boulder, Boulder, Colorado, USA.

Gloria R Brisson, Medical Services, University of Colorado Boulder, Boulder, Colorado, USA.

Daniel B Larremore, BioFrontiers Institute, University of Colorado Boulder, Boulder, Colorado, USA; Department of Computer Science, University of Colorado Boulder, Boulder, Colorado, USA.

Leslie A Leinwand, BioFrontiers Institute, University of Colorado Boulder, Boulder, Colorado, USA; Department of Molecular, Cellular, and Developmental Biology, University of Colorado Boulder, Boulder, Colorado, USA.

Matthew B McQueen, Department of Integrative Physiology, University of Colorado Boulder, Boulder, Colorado, USA; Institute for Behavioral Genetics, University of Colorado Boulder, Boulder, Colorado, USA.

Roy Parker, BioFrontiers Institute, University of Colorado Boulder, Boulder, Colorado, USA; Howard Hughes Medical Institute, University of Colorado Boulder, Boulder, Colorado, USA; Department of Biochemistry, University of Colorado Boulder, Boulder, Colorado, USA.

References

- 1. CSSE at Johns Hopkins University. COVID-19 dashboard by the Center for Systems Science and Engineering (CSSE) at Johns Hopkins University (JHU). 2021. https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/map.html. Accessed 8 July 2021.

- 2. Dong E, Du H, Gardner L. An interactive web-based dashboard to track COVID-19 in real time. Lancet Infect Dis 2020; 20:533–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Madewell ZJ, Yang Y, Longini IM Jr, Halloran ME, Dean NE. Household transmission of SARS-CoV-2: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Netw Open 2020; 3:e2031756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Lennon NJ, Bhattacharyya RP, Mina MJ, et al. Comparison of viral levels in individuals with or without symptoms at time of COVID-19 testing among 32,480 residents and staff of nursing homes and assisted living facilities in Massachusetts. medRxiv [Preprint: not peer reviewed]. 26 July 2020. Available from: https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2020.07.20.20157792v1. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kissler SM, Fauver JR, Mack C, et al. Viral dynamics of acute SARS-CoV-2 infection and applications to diagnostic and public health strategies. PLoS Biol 2021; 19:e3001333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Yang Q, Saldi TK, Lasda E, et al. Just 2% of SARS-CoV-2-positive individuals carry 90% of the virus circulating in communities. Proc Natl Acad Sci 2021; 118:e2104547118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Marks M, Millat-Martinez P, Ouchi D, et al. Transmission of COVID-19 in 282 clusters in Catalonia, Spain: a cohort study. Lancet Infect Dis 2021; 21:914–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Lavezzo E, Franchin E, Ciavarella C, et al. ; Imperial College COVID-19 Response Team; Imperial College COVID-19 Response Team. Suppression of a SARS-CoV-2 outbreak in the Italian municipality of Vo’. Nature 2020; 584:425–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Poletti P, Tirani M, Cereda D, et al. ; ATS Lombardy COVID-19 Task Force. Association of age with likelihood of developing symptoms and critical disease among close contacts exposed to patients with confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection in Italy. JAMA Netw Open 2021; 4:e211085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Subramanian R, He Q, Pascual M. Quantifying asymptomatic infection and transmission of COVID-19 in New York City using observed cases, serology, and testing capacity. Proc Natl Acad Sci 2021; 118:e2019716118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Lee S, Kim T, Lee E, et al. Clinical course and molecular viral shedding among asymptomatic and symptomatic patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection in a community treatment center in the Republic of Korea. JAMA Intern Med 2020; 180:1447–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Cevik M, Tate M, Lloyd O, Maraolo AE, Schafers J, Ho A. SARS-CoV-2, SARS-CoV, and MERS-CoV viral load dynamics, duration of viral shedding, and infectiousness: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Microbe 2021; 2:e13–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Johansson MA, Quandelacy TM, Kada S, et al. SARS-CoV-2 transmission from people without COVID-19 symptoms. JAMA Netw Open 2021; 4:e2035057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Williamson EJ, Walker AJ, Bhaskaran K, et al. Factors associated with COVID-19-related death using OpenSAFELY. Nature 2020; 584:430–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. When to quarantine. 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/if-you-are-sick/quarantine.html. Accessed 12 February 2021.

- 16. R Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing [Internet]. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing, 2020. https://www.r-project.org/. Accessed 2 February 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Hefner J, Eisenberg D. Social support and mental health among college students. Am J Orthopsychiatry 2009; 79:491–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Eisenberg D, Golberstein E, Whitlock JL. Peer effects on risky behaviors: new evidence from college roommate assignments. J Health Econ 2014; 33:126–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Larremore DB, Toomre D, Parker R. Modeling the effectiveness of olfactory testing to limit SARS-CoV-2 transmission. Nat Commun 2021; 12:3664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Larremore DB, Wilder B, Lester E, et al. Test sensitivity is secondary to frequency and turnaround time for COVID-19 screening. Sci Adv 2021; 7:eabd5393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kawasuji H, Takegoshi Y, Kaneda M, et al. Transmissibility of COVID-19 depends on the viral load around onset in adult and symptomatic patients. PLoS One 2020; 15:e0243597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Gibson GC, Weitz JS, Shannon MP, et al. Surveillance-to-diagnostic testing program for asymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infections on a large urban campus—Georgia institute of technology fall 2020. medRxiv [Preprint: not peer reviewed]. 31 January 2021. Available from: https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2021.01.28.21250700v1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Stubbs CW, Springer M, Thomas TS. The impacts of testing cadence, mode of instruction, and student density on fall 2020 COVID-19 rates on campus. medRxiv [Preprint: not peer reviewed]. 9 December 2020. Available from: https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2020.12.08.20244574v1. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Endo A, Abbott S, Kucharski AJ, Funk S; Centre for the Mathematical Modelling of Infectious Diseases COVID-19 Working Group. Estimating the overdispersion in COVID-19 transmission using outbreak sizes outside China. Wellcome Open Res 2020; 5:67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.