Abstract

We aimed to estimate parents' willingness and refusal to vaccinate their children against the COVID-19, and to investigate the predictors for their decision. We followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis guidelines. We searched Scopus, Web of Science, Medline, PubMed, CINAHL and medrxiv from inception to December 12, 2021. We applied a random effect model to estimate pooled effects since the heterogeneity was very high. We used subgroup analysis and metaregression analysis to explore sources of heterogeneity. We found 44 studies including 317,055 parents. The overall proportion of parents that intend to vaccinate their children against the COVID-19 was 60.1%, while the proportion of parents that refuse to vaccinate their children was 22.9% and the proportion of unsure parents was 25.8%. The main predictors of parents' intention to vaccinate their children were fathers, older age of parents, higher income, higher levels of perceived threat from the COVID-19, and positive attitudes towards vaccination (e.g. children's complete vaccination history, history of children's and parents' vaccination against influenza, confidence in vaccines and COVID-19 vaccines, and COVID-19 vaccine uptake among parents). Parents' willingness to vaccinate their children against the COVID-19 is moderate and several factors affect this decision. Understanding parental COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy does help policy makers to change the stereotypes and establish broad community COVID-19 vaccination. Identification of the factors that affect parents' willingness to vaccinate their children against COVID-19 will provide opportunities to enhance parents' trust in the COVID-19 vaccines and optimize children's uptake of a COVID-19 vaccine.

Keywords: COVID-19, Vaccination, Willingness, Predictors, Refusal, Children, Parents

1. Introduction

Given the human, social and economic burden of the Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, the uptake of a safe and effective vaccine remains a critical strategy to curb its impact (Graham, 2020). Simulation experiments revealed that up to 80% of the population needs to receive a COVID-19 vaccine that is at least 80% effective to largely extinguish the COVID-19 pandemic without any other non-pharmaceutical measures (e.g., social distancing, masks, etc.) (Bartsch et al., 2020). Thus, COVID-19 vaccine uptake among children will be instrumental in limiting the spread of the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) and the disease.

COVID-19 vaccine uptake relies on adequate production, fair distribution, and high levels of acceptance among the general public (Neumann-Böhme et al., 2020). Recent meta-analyses found that the overall COVID-19 vaccine acceptance rate was approximately 73%, while acceptance among the general population is higher than among healthcare workers (Galanis et al., 2021; Luo et al., 2021; Snehota et al., 2021; Wang et al., 2021b). Also, real-world data from early studies reveal that COVID-19 vaccination uptake ranges from 28.6% to 98% in the general population (Galanis et al., 2021a). Several factors influence vaccination intention and uptake in the general population such as sociodemographic characteristics, attitudes towards vaccination, psychological factors, perceptions of risk and susceptibility to COVID-19, knowledge, information, personal factors, medical conditions, etc. (Al-Amer et al., 2021; Galanis et al., 2021a; Snehota et al., 2021; Wake, 2021; Wang et al., 2021b).

The risk of severe illness and death from the COVID-19 remains quite low for children, but children COVID-19 cases rise sharply due to the highly transmissible delta variant (Tanne, 2021). For instance, since the COVID-19 pandemic began, children represent 14.4% of total COVID-19 cases in the USA but for the week ending August 12, 2021, children were 18% of weekly cases (American Academy of Pediatrics, 2021). Moreover, children make up about 2.4% of total hospitalizations in the USA and about 1% of all pediatric COVID-19 cases resulted in hospitalization since the start of the pandemic (American Academy of Pediatrics, 2021). Additionally, preliminary findings show that a recent mutation of SARS-CoV-2 (omicron variant) is spreading faster than any previous variant and may be more transmissible than other coronavirus variants (Dyer, 2021; Mahase, 2021). Thus, there is a need for safe and effective COVID-19 vaccines for children of all ages as swiftly as possible (Tanne, 2021). Currently, COVID-19 vaccines are approved for children aged 12 and older and it is anticipated that younger children will become eligible since pharmaceutical companies are running clinical trials with children to study the safety and efficacy of COVID-19 vaccines (European Medicines Agency, 2021a, European Medicines Agency, 2021b; Health Canada, 2021).

Since parents are key decision-makers for whether their children will receive a COVID-19 vaccine, it is important to measure willingness of parents to vaccinate their children against the COVID-19. Early studies have already investigated parents' intention to vaccinate their children but until now, no systematic review and meta-analysis on this field is published. Thus, we performed a systematic review and meta-analysis to estimate parents' willingness to vaccinate their children against the COVID-19, and to investigate the predictors for their decision. Also, we estimated the percentage of the parents that (a) refuse to vaccinate their children against the COVID-19, and (b) were unsure.

2. Methods

2.1. Data sources and strategy

We performed a systematic review and meta-analysis, applying the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) guidelines (Moher et al., 2009). We searched Scopus, Web of Science, Medline, PubMed, CINAHL and pre-print services (medrxiv) from inception to December 12, 2021. We used the following strategy in all fields: ((vaccin*) AND (COVID-19)) AND (parent*). The review protocol was registered with PROSPERO (CRD42021273125).

2.2. Selection and eligibility criteria

Firstly, we removed duplicates, and then we screened consecutively titles, abstracts, and full texts. Also, we examined reference lists of all relevant articles. Two independent researchers performed study selection and a third, senior researcher resolved the discrepancies. We included quantitative studies reporting parents' willingness to vaccinate their children against the COVID-19. Also, we included quantitative studies that examine factors that affect parents' willingness to vaccinate their children. Study population included parents and guardians of children aged <18 years. We did not apply criteria regarding study population, e.g. gender, age, race, sample size, etc. We included studies with parents from the general population and excluded studies involving specific population groups (e.g. parents with mental issues or other health issues, specific occupational groups such as physicians, nurses, teachers, etc.). Studies published in English in journals with peer review system were eligible to be included. We excluded protocols, reviews, case reports, opinions articles, commentaries, editorials, and letters to the Editor.

2.3. Data extraction and quality assessment

Two authors independently extracted the following data from the studies: reference, country, data collection time, sample size, gender of parents, age of parents and children, study design, sampling method, recruitment method, response rate, publication type (journal or pre-print), question or statement to measure parents' willingness, response scales, percentage of parents that agree to vaccinate their children, percentage of parents that refuse to vaccinate their children, percentage of parents that were unsure, and factors that affect parents' willingness to vaccinate their children.

Studies quality was assessed with the Joanna Briggs Institute critical appraisal tool (Santos et al., 2018). The tool consists of eight questions regarding inclusion criteria for the sample, study settings, exposure and outcome measurement, identification and elimination of confounders, and statistical analysis. There are four answers for each question; e.g., the answers “yes”, “no”, “unclear” and “not applicable” for the question “were strategies to deal with confounding factors stated?”. For this question, when authors use multivariable methods to estimate the relation between an independent variable and the outcome the answer is “yes”, when authors use only univariate methods the answer is “no”, and when the authors do not investigate the relation between an independent variable and the outcome the answer is “not applicable”. Two independent authors rated the quality of the studies and a third senior author solved any discrepancies.

2.4. Statistical analysis

Parents' intention to vaccinate their children was assessed with a variety of statements or questions like these “When a vaccine for Coronavirus becomes available, I will have my child get it”, “If a COVID-19 vaccine is safe and available to your child for free, how likely would your child be to get vaccinated?”, “At this moment, are you willing to receive COVID-19 vaccination for your child?” etc. Possible answers were in (a) Likert scales (e.g. strongly disagree; disagree; neither disagree nor agree; agree; strongly agree), (b) yes/no/unsure options, and (c) yes/no options. For each study, we followed the authors' decision regarding the positive answer, the negative answer and the unsure answer of parents. For instance, in studies where authors used Likert scales, a positive answer could be only one answer (strongly agree) or two answers (agree and strongly agree). We divided the positive answers of parents by the total number of parents to calculate the proportion of parents that agreed to vaccinate their children. In a similar way, we calculated the proportion of parents that refuse a COVID-19 vaccine for their children, and the proportion of parents that were unsure. Then, we transformed these three proportions with the Freeman-Tukey Double Arcsine method and we calculated the proportion of parents that (a) intend to vaccinate their children against the COVID-19, (b) refuse to vaccinate their children, and (c) were unsure. Moreover, we calculated the 95% confidence intervals (CI) for the proportions (Barendregt et al., 2013).

We used the Hedges Q statistics and I2 to assess heterogeneity between studies. A p-value < 0.1 for the Hedges Q statistic indicates statistically significant heterogeneity, while I2 value higher than 75% indicates high heterogeneity (Higgins, 2003). We applied a random effect model to estimate pooled effects since the heterogeneity between results was very high (Higgins, 2003). We considered data collection time, age of parents and children, study design, sampling method, recruitment method, response rate, publication type, response scales (studies with or without unsure option), studies quality, and the continent that studies were conducted as pre-specified sources of heterogeneity. Due to the scarce data and the high heterogeneity in the results in some variables (e.g. age of parents and children), we decided to perform subgroup analysis for recruitment method, publication type, response scales, studies quality, and the continent that studies were conducted. Also, we performed meta-regression analysis using data collection time as the independent variable. We treated data collection time as a continuous variable giving the number 1 for studies that were conducted in January 2020, the number 2 for studies that were conducted in February 2020 etc. We conducted a leave-one-out sensitivity analysis to determine the influence of each study on the overall effect. We used the funnel plot and the Egger's test to assess the publication bias. Regarding the Egger's test, a p-value < 0.05 indicating publication bias (Egger et al., 1997). We used OpenMeta[Analyst] for the meta-analysis (Wallace et al., 2009).

We did not perform meta-analysis for the factors that influence parents' decision to vaccinate their children against the COVID-19 since the data were highly heterogeneous. Since predictors were measured and/or analyzed differently across studies, we reported the proportion of studies finding positive or negative significant relationships (p-value < 0.05) between each predictor and parents' intention to vaccinate their children. Thus, we calculated this proportion dividing the number of studies with a significant association (p-value < 0.05) between the predictor and parents' willingness to vaccinate their children against the COVID-19 by the total number of studies examined the predictor.

3. Results

3.1. Identification and selection of studies

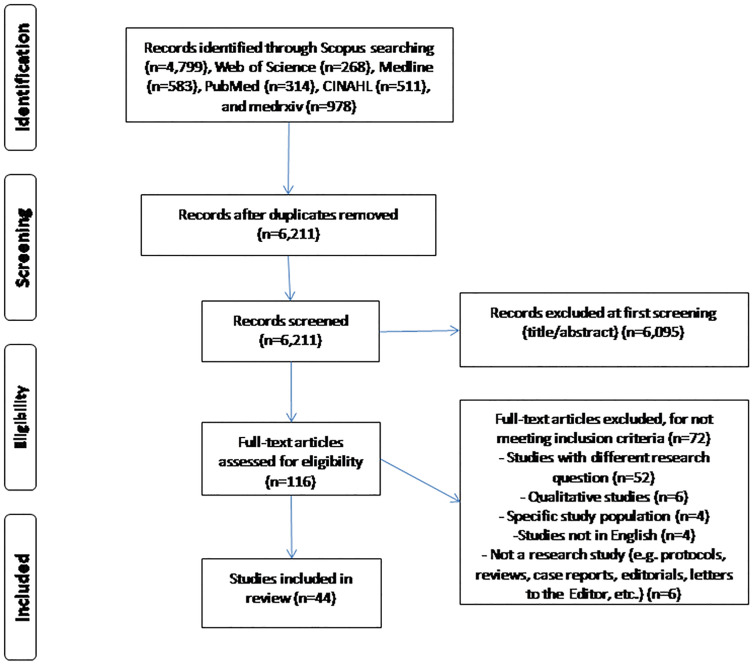

After initial search, we found 6211 unique records. Applying the inclusion and exclusion criteria, we identified 44 articles (Fig. 1 ).

Fig. 1.

Flowchart of the literature search according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis.

3.2. Characteristics of the studies

We found 44 studies including 317,055 parents. Details of the studies included in this systematic review are presented in Table 1 . Seven studies were conducted in the USA, six studies in China, four studies in Canada, four studies in Israel, four studies in Turkey, four studies in Saudi Arabia, five studies in other European countries (German, Greece, Italy, Poland, and United Kingdom), and one study in India, Korea, New Zealand, Qatar, Zambia, Australia, and Brazil. Also, three studies covered more than two countries. Data collection time among studies ranged from March 2020 to September 2021. Sample size ranged from 226 to 227,740 parents with a median number of 1094 parents. The minimum percentage of mothers participating in the studies was 39.6%, while the maximum percentage was 100%. All studies were cross-sectional, while 38 studies used a convenience sample, three studies used a probability sample, one study used a non-probability sample, and two studies used the snowball sampling method. Recruitment of parents was achieved through online surveys in 34 studies, while in 10 studies the study questionnaire was completed during the visit of parents in clinical settings (e.g., pediatric emergency departments, outpatients clinics, primary healthcare centers, etc.). Thirty-eight articles were in peer-reviewed journals and six articles were in pre-print services. Twenty-nine studies included an “unsure” response option for parents' willingness to vaccinate their children, 14 studies did not include this response option, and one study used a scale from 1 to 100 (Table 2 ).

Table 1.

Overview of the studies included in systematic review.

| Reference | Country | Data collection time | Sample size (n) | Mothers (%)/fathers (%) | Age of parents, mean (SD) | Age of children, mean (SD) | Study design | Sampling method | Recruitment method | Response rate (%) | Published in |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Ruggiero et al., 2021) | USA | November 2020 to January 2021 | 427 | NR | NR | <3 years, 23.1%; 4–12 years, 59.2%; 13–18 years, 23.6% | Cross-sectional | Snowball | Online survey | NR | Journal |

| (Wang et al., 2021a) | China | September 21 to October 17, 2020 | 3009 | 74.6/25.4 | 31.4 (4.5) | 2.2 (2.4) | Cross-sectional | Convenience | Community health service center immunization clinics | NR | Journal |

| (Szilagyi et al., 2021) | USA | February 17 to March 30, 2021 | 1745 | 57.9/42.1 | 18–39 years, 23.3%; 40–49 years, 34.3%; ≥50 years, 38.2% | <5 years, 21.8%; 5–10 years, 27%; 11–18 years, 32.7% | Cross-sectional | Probability | National online survey | 87 | Journal |

| (Montalti et al., 2021) | Italy | December 2020 to January 2021 | 4993 | 76.6/23.4 | ≤29 years, 1.8%; 30–39 years, 18.9%; 40–49 years, 55.4%; ≥50 years, 24% | ≤5 years, 12.7%; 6–13 years, 62.5%; ≥14 years, 24.9% | Cross-sectional | Convenience | Online survey | NR | Journal |

| (Kelly et al., 2021) | USA | April 2020 | 2279 | 52/48 | ≤34 years, 27%; 35–49 years, 24%; 50–64 years, 26%; ≥65 years, 22% | NR | Cross-sectional | Probability | National community online survey | NR | Journal |

| (Bell et al., 2020a) | United Kingdom | April 19 to May 11, 2020 | 1252 | 95/5 | 32.9 (4.6) | ≤14 months, 88.9%; 14–18 months, 11.1% | Cross-sectional | Convenience | Online survey | NR | Journal |

| (Xu et al., 2021c) | China | December 2020 | 4748 | 76/24 | 40.2 (5.1) | <10 years, 27.9%; 10–14 years, 49.5%; ≥14 years, 22.6% | Cross-sectional | Convenience | Online survey | NR | Journal |

| (Brandstetter et al., 2021) | Germany | May 2020 | 612 | 80/10 (10 mothers and fathers) | NR | 3.4 (0.9) | Cross-sectional | Convenience | Online survey | 50.1 | Journal |

| (Skjefte et al., 2021) | USA, India, Brazil, Russia, Spain, Argentina, Colombia, United Kingdom, Mexico, Peru, South Africa, Italy, Chile, Philippines, Australia, and New Zealand | October 28 to November 18, 2020 | 17,054 | 100/0 | 34.4 (7.3) | NR | Cross-sectional | Convenience | Online survey | NR | Journal |

| (Goldman et al., 2020) | USA, Canada, Spain, Israel, Japan, and Switzerland | March 26 to May 31, 2020 | 1541 | 72/25.5 (2.5 other) | 39.9 (7.6)a | 7.5 (5.0)a | Cross-sectional | Convenience | Pediatric emergency departments | NR | Journal |

| (Hetherington et al., 2021) | Canada | May to June 2020 | 1321 | 100/0 | 42.2 (4.4) | NR | Cross-sectional | Convenience | Online survey | 53.8 | Journal |

| (Yigit et al., 2021) | Turkey | NR | 428 | 63.6/36.4 | 39.7 (10.7) | NR | Cross-sectional | Convenience | Children's hospital | NR | Journal |

| (Yilmaz and Sahin, 2021) | Turkey | February 2021 | 1035 | 77.8/22.2 | ≤29 years, 12.6%; 30–39 years, 53.3%; ≥40 years, 34.1% | ≤6 years, 49.8%; 7–12 years, 28.9%; ≥13 years, 21.4% | Cross-sectional | Convenience | Online survey | NR | Journal |

| (Teasdale et al., 2021) | USA | March 2021 | 2074 | 60.1/39.3 (0.6 others) | ≤29 years, 20.3%; 30–44 years, 65.1%; ≥45 years, 14.6% | 4.7 (1.7–8.3)b | Cross-sectional | Convenience | Community online survey | NR | Journal |

| (Jeffs et al., 2021) | New Zealand | May 2020 | 1191 | 92.7/6.2 (1.2 caregivers) | 39.9 (NR) | NR | Cross-sectional | Convenience | Online survey | NR | Journal |

| (Scherer et al., 2021) | USA | April 2021 | 1022 | 48.2/51.3 (0.5 others) | NR | ≤15 years, 62%; ≥16 years, 38% | Cross-sectional | Convenience | Online survey | 77.5 | Journal |

| (Zhang et al., 2020) | China | September 2020 | 1052 | 62.5/37.5 | ≤30 years, 22.6%; 31–40 years, 55.7%; ≥41 years, 21.7% | ≤12 years, 82%; ≥13 years, 18% | Cross-sectional | Convenience | Online survey | NR | Journal |

| (Akarsu et al., 2021) | Turkey | June to July 2020 | 232 | 62.8/37.2 | 32.4 (9.9) | NR | Cross-sectional | Snowball | Online survey | NR | Journal |

| (Aldakhil et al., 2021) | Saudi Arabia | January to February 2021 | 280 | 100/0 | 33 (5.5) | <6 months, 12.4%; 6–18 months, 18.2%; >18 months, 69.4% | Cross-sectional | Non-probability purposive | Outpatients clinics | NR | Journal |

| (Alfieri et al., 2021) | USA | June 2020 | 1425 | NR | NR | NR | Cross-sectional | Probability purposive | Online survey | 38.4 | Journal |

| (Almusbah et al., 2021) | Saudi Arabia | May to June 2021 | 1000 | 78.8/21.2 | NR | 0–2 years, 40.2%; 2–6 years, 40.2%; >6 years, 35.2% | Cross-sectional | Convenience | Online survey | NR | Journal |

| (Altulaihi et al., 2021) | Saudi Arabia | NR | 333 | 49.8/50.2 | 18–30 years, 29.1%; 31–40 years, 45.6%; >40 years, 25.3% | 0–6 years, 41.4%; 7–17 years, 58.6% | Cross-sectional | Convenience | Primary healthcare centers | 83.3 | Journal |

| (Babicki et al., 2021) | Poland | May 2021 | 4432 | 77.6/22.4 | 37.5 (6.6) | <2 years, 16.6%; ≥2 years, 83.4% | Cross-sectional | Convenience | Online survey | NR | Journal |

| (Bagateli et al., 2021) | Brazil | May to June 2021 | 501 | 85/15 | 18–29 years, 13%; ≥30 years, 87% | <9 years, 59%; ≥9 years, 41% | Cross-sectional | Convenience | Pediatric emergency departments | 100 | Journal |

| (Carcelen et al., 2021) | Zambia | November 2020 | 2400 | NR | NR | NR | Cross-sectional | Convenience | Primary healthcare centers | NR | Journal |

| (Choi et al., 2021) | Korea | May to June 2021 | 226 | 79.6/20/4 | <39 years, 34.5%; ≥40 years, 65.5% | 10–15 years, 84.6%; 16–18 years, 15.4% | Cross-sectional | Convenience | Outpatients clinics | NR | Journal |

| (Dror et al., 2020) | Israel | March 2020 | 1112 | NR | NR | NR | Cross-sectional | Convenience | Online survey | NR | Journal |

| (Evans et al., 2021) | Australia | January 2021 | 1094 | 83/17 | 39.2 (6.8) | 8.9 (5.1) | Cross-sectional | Convenience | Online survey | NR | Journal |

| (Gendler and Ofri, 2021) | Israel | June 2021 | 520 | 77.1/22.9 | 44.8 (8.1) | NR | Cross-sectional | Convenience | Online survey | NR | Journal |

| (Humble et al., 2021) | Canada | December 2020 | 1702 | 55.3/44 | 39.2 (8.4) | <12 years, 66.4%; ≥12 33.6% | Cross-sectional | Convenience | Online survey | NR | Journal |

| (Kezhong et al., 2021) | China | July 2021 | 13,451 | 63.6/36.4 | 36.0 (5.7) | NR | Cross-sectional | Convenience | Online survey | NR | Journal |

| (Lackner and Wang, 2021) | Canada | July 2020 | 455 | 91.9/7.3 | 38.2 (6.8) | NR | Cross-sectional | Convenience | Online survey | NR | Journal |

| (Musa et al., 2021) | Qatar | May to June 2021 | 4023 | NR | NR | 13.4 (1.1) | Cross-sectional | Convenience | Outpatients clinics | NR | Journal |

| (Temsah et al., 2021) | Saudi Arabia | NR | 3167 | 65/35 | 18–44 years, 62.7%; ≥45 years, 37.3% | NR | Cross-sectional | Convenience | Online survey | NR | Journal |

| (Urrunaga-Pastor et al., 2021) | 20 Latin America and Caribbean countries | May to July 2021 | 227,740 | 55/45 | 18–34 years, 41.3%; ≥35 years, 58.7% | NR | Cross-sectional | Convenience | Online survey | NR | Journal |

| (Xu et al., 2021b) | China | July to August 2021 | 917 | 67.5/32.5 | 37.0 (5.9) | NR | Cross-sectional | Convenience | Online survey | NR | Journal |

| (Yılmazbaş et al., 2021) | Turkey | May 2020 | 440 | 70.5/29.5 | 39.1 (6.4) | NR | Cross-sectional | Convenience | Online survey | NR | Journal |

| (Zhou et al., 2021) | China | July to September 2020 | 747 | 75.5/24.5 | <40 years, 82.6%; ≥40 years, 17.4% | NR | Cross-sectional | Convenience | Primary healthcare centers | NR | Journal |

| (Galanis et al., 2021b) | Greece | September 2021 | 813 | 76.1/23.9 | 42.3 (7.4) | NR | Cross-sectional | Convenience | Online survey | NR | Pre-print |

| (Atad et al., 2021) | Israel | April to May 2021 | 1118 | NR | NR | NR | Cross-sectional | Convenience | Online survey | NR | Pre-print |

| (Davis et al., 2020) | USA | June 2020 | 1008 | NR | NR | NR | Cross-sectional | Convenience | National online survey | 50 | Pre-print |

| (Padhi et al., 2021) | India | November 2020 to January 2021 | 770 | 39.6/60.4 | 18–49 years, 75.6%; ≥50 years, 24.4% | NR | Cross-sectional | Convenience | Online survey | NR | Pre-print |

| (McKinnon et al., 2021) | Canada | May to June 2021 | 809 | NR | NR | NR | Cross-sectional | Convenience | Online survey | NR | Pre-print |

| (Shmueli, 2021) | Israel | September to October 2021 | 1012 | 51/49 | 18–39 years, 48.3%, ≥40 years, 51.7% | NR | Cross-sectional | Convenience | Online survey | NR | Pre-print |

NR: not reported.

Median (standard deviation).

Median (interquartile range).

Table 2.

Response scales and results of parents' willingness to vaccinate their children against the COVID-19 in studies included in systematic review.

| Reference | Question/statement to measure parents' willingness | Response scalea | Willingness results (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| (Ruggiero et al., 2021) | I plan to have my child vaccinated with a COVID-19 vaccine if one becomes available | Yes [Y], no [N] | Yes: 44.3 |

| No: 55.7 | |||

| (Wang et al., 2021a) | If a COVID-19 vaccine is available, will you vaccinate for your child? | Yes [Y], unsure [U], no [N] | Yes: 59.3 |

| Unsure: 37.4 | |||

| No: 3.3 | |||

| (Szilagyi et al., 2021) | How likely are you to get your child vaccinated for coronavirus once a vaccine is available for children? | Very likely [Y], somewhat likely [Y], unsure [N], somewhat unlikely [N], very unlikely [N] | Yes: 48 |

| No: 52 | |||

| (Montalti et al., 2021) | If a new COVID-19 vaccine became available would you accept the vaccine for your child/children? | Yes [Y], unsure [U], no [N] | Yes: 60.4 |

| Unsure: 29.6 | |||

| No: 9.9 | |||

| (Kelly et al., 2021) | When a vaccine for Coronavirus becomes available, I will have my child get it | Strongly agree [Y], agree [Y], disagree [N], strongly disagree [N] | Yes: 73 |

| No: 27 | |||

| (Bell et al., 2020a) | If a new coronavirus (COVID-19) vaccine became available would you accept the vaccine for your child/children? | Yes, definitely [Y], unsure but leaning towards yes [U], unsure but leaning towards no [U], no, definitely not [N] | Yes: 48.2 |

| Unsure: 48.4 | |||

| No: 3.4 | |||

| (Xu et al., 2021c) | At this moment, are you willing to receive COVID-19 vaccination for your child? | Yes [Y], unsure [U], no [N] | Yes: 72.7 |

| Unsure: 6.7 | |||

| No: 20.6 | |||

| (Brandstetter et al., 2021) | If there was an effective vaccine against COVID-19, would you have your child vaccinated? | Yes [Y], unsure [U], no [N] | Yes: 51 |

| Unsure: NR | |||

| No: NR | |||

| (Skjefte et al., 2021) | If a COVID-19 vaccine is safe and available to your child for free, how likely would your child be to get vaccinated if the vaccine has an efficacy of 90% (in other words, it reduces the chance of getting infected by 90%)? | Very likely [Y], fairly likely [Y], somewhat likely [Y], quite unlikely [N], not at all likely [N] | Yes: 69.2 |

| No: 30.8 | |||

| (Goldman et al., 2020) | There is no vaccine/immunization currently available for Coronavirus (COVID-19). If a vaccine/immunization was available today, would you give it to your child? | Yes [Y], no [N] | Yes: 65.2 |

| No: 34.8 | |||

| (Hetherington et al., 2021) | If an approved COVID-19 vaccine becomes available, would you plan to have your child receive this vaccine? | Yes [Y], unsure [U], no [N] | Yes: 60.4 |

| Unsure: 31.0 | |||

| No: 8.6 | |||

| (Yigit et al., 2021) | Would you vaccinate your child if a COVID-19 vaccine is available? | Yes [Y], no [N] | Yes: 29 |

| No: 71 | |||

| (Yilmaz and Sahin, 2021) | If an approved COVID-19 vaccine becomes available, would you plan to have your child receive this vaccine? | Yes [Y], unsure [U], no [N] | Yes: 36.3 |

| Unsure: 35.6 | |||

| No: 28.1 | |||

| (Teasdale et al., 2021) | When a vaccine to prevent COVID-19 is approved for children, would you want your child to receive the vaccine? | Yes [Y], unsure [U], no [N] | Yes: 49.4 |

| Unsure: 25.0 | |||

| No: 25.6 | |||

| (Jeffs et al., 2021) | Would you vaccinate your child if a COVID-19 vaccine is available? | Yes [Y], unsure [U], no [N] | Yes: 69.5 |

| Unsure: NR | |||

| No: NR | |||

| (Scherer et al., 2021) | Would you vaccinate your child if a COVID-19 vaccine is available? | Definitely will get a vaccine [Y], probably will get a vaccine [Y], probably will not get a vaccine [N], definitely will not get a vaccine [N] | Yes: 55.5 |

| No: 44.5 | |||

| (Zhang et al., 2020) | If a COVID-19 vaccine is safe and available to your child for free, how likely would your child be to get vaccinated? | Very likely [Y], likely [Y], neutral [U], unlikely [N], very unlikely [N] | Yes: 72.6 |

| Unsure: 21.3 | |||

| No: 6.1 | |||

| (Akarsu et al., 2021) | If an approved COVID-19 vaccine becomes available, would you plan to have your child receive this vaccine? | Yes [Y], unsure [U], no [N] | Yes: 55.5 |

| Unsure: 35.9 | |||

| No: 8.6 | |||

| (Aldakhil et al., 2021) | It is likely that I will vaccinate my child/children against COVID-19 in the next 6 months | Strongly agree [Y], agree [Y], neutral [U], disagree [N], strongly disagree [N] | Yes: 52.5 |

| Unsure: 27.9 | |||

| No: 19.6 | |||

| (Alfieri et al., 2021) | If a new vaccine against COVID-19 became available, how likely would you be to get your child vaccinated? | Very likely [Y], somewhat likely [Y], I'm not sure [U], not likely [N] | Yes: 33.0 |

| Unsure: NR | |||

| No: NR | |||

| (Almusbah et al., 2021) | Are you willing to get the COVID-19 vaccine for your child if approved? | Yes [Y], unsure [U], no [N] | Yes: 25.6 |

| Unsure: 37.0 | |||

| No: 37.4 | |||

| (Altulaihi et al., 2021) | If a COVID-19 vaccine is available, will you vaccinate for your child? | Very likely [Y], likely [Y], neutral [U], unlikely [N], very unlikely [N] | Yes: 54.1 |

| Unsure: 18.9 | |||

| No: 27.0 | |||

| (Babicki et al., 2021) | Are you planning to vaccinate your child against COVID-19? | Yes, as soon as it will be possible [Y], yes, but only in a few months (up to a year) [Ν], yes, but in more than a year [Ν], I cannot decide [U], no, but maybe I will consider it in the future [N], no, never [N] | Yes: 44.1 |

| Unsure: 11.3 | |||

| No: 44.6 | |||

| (Bagateli et al., 2021) | Would you have your child vaccinated with a vaccine reported effective against COVID-19 and approved by the authorities? | Yes [Y], unsure [U], no [N] | Yes: 91 |

| Unsure: 4.6 | |||

| No:4.4 | |||

| (Carcelen et al., 2021) | If a COVID-19 vaccine is available, will you vaccinate your child? | Yes [Y], unsure [U], no [N] | Yes: 92 |

| Unsure: NR | |||

| No: NR | |||

| (Choi et al., 2021) | If a vaccine against COVID-19 is available, how likely would you be to get your children vaccinated? | Extremely likely [Y], somewhat likely [Y], neither likely nor unlikely [U], somewhat unlikely [N], extremely unlikely [N] | Yes: 64.2 |

| Unsure: 23.5 | |||

| No: 12.3 | |||

| (Dror et al., 2020) | Would you vaccinate your child for COVID-19? | Yes [Y], unsure [U], no [N] | Yes: 70 |

| Unsure: NR | |||

| No: NR | |||

| (Evans et al., 2021) | If a COVID-19 vaccine is available, will you vaccinate for your child? | Yes [Y], unsure [U], no [N] | Yes: 48 |

| Unsure: 38 | |||

| No: 14 | |||

| (Gendler and Ofri, 2021) | If a vaccine against COVID-19 is available, how likely would you be to get your children vaccinated? | Very likely [Y], somewhat likely [Y], somewhat unlikely [N], definitely not [N] | Yes: 70.4 |

| No:29.6 | |||

| (Humble et al., 2021) | If a safe and effective COVID-19 vaccine is available, I will get my child/children vaccinated | Strongly agree [Y], agree [Y], neutral [U], disagree [N], strongly disagree [N] | Yes: 63.1 |

| Unsure: NR | |||

| No: NR | |||

| (Kezhong et al., 2021) | If a COVID-19 vaccine is available, will you vaccinate for your child? | Yes [Y], unsure [U], no [N] | Yes: 50.0 |

| Unsure: NR | |||

| No: NR | |||

| (Lackner and Wang, 2021) | If a vaccine against COVID-19 is available, how likely would you be to get your children vaccinated? | A scale from 1 to 100 | Yes: NR |

| Unsure: NR | |||

| No: NR | |||

| (Musa et al., 2021) | Parents' agreement to obtain a confirmed COVID-19 vaccine booking appointment for their children at the time of study | Yes [Y], no [N] | Yes: 82.1 |

| No: 17.9 | |||

| (Temsah et al., 2021) | Are you willing/intending to give the COVID-19 vaccine to your child (children)? | Yes [Y], unsure [U], no [N] | Yes: 47.5 |

| Unsure: 20.5 | |||

| No: 32.0 | |||

| (Urrunaga-Pastor et al., 2021) | Will you choose to get a COVID-19 vaccine for your child or children when they are eligible? | Yes, definitely [Y], yes, probably [Y], no, probably not [N], no, definitely not [N] | Yes: 92.2 |

| No: 7.8 | |||

| (Xu et al., 2021b) | If a COVID-19 vaccine is available for your children, would you like them to get it? | Yes [Y], unsure [U], no [N] | Yes: 84.3 |

| Unsure: NR | |||

| No: NR | |||

| (Yılmazbaş et al., 2021) | If a vaccine is reported to be effective against COVID-19, would you consider getting it to your children? | I definitely do [Y], I'll probably get it [U], undecided [U], I definitely not [N] | Yes: 43.4 |

| Unsure: 55.0 | |||

| No: 1.6 | |||

| (Zhou et al., 2021) | If a COVID-19 vaccine is available, will you vaccinate your child? | Yes [Y], no [N] | Yes: 85.3 |

| No: 14.7 | |||

| (Galanis et al., 2021b) | If a COVID-19 vaccine is available, will you vaccinate your child? | Yes [Y], unsure [U], no [N] | Yes: 36.0 |

| Unsure: 30.5 | |||

| No: 33.5 | |||

| (Atad et al., 2021) | Do you intend to vaccinate your children when the COVID-19 vaccine becomes available for them? | Yes, definitely [Y], yes, probably [N], undecided [N], no, probably not [N], no, definitely not [N] | Yes: 31.5 |

| No: 68.5 | |||

| (Davis et al., 2020) | If a vaccine against COVID-19 becomes available in the next 12 months, how likely are you to get it for your child(ren)? | Very likely [Y], somewhat likely [Y], not too likely [N], not at all likely [N] | Yes: 63.0 |

| No: 37.0 | |||

| (Padhi et al., 2021) | Do you intend to vaccinate your child(ren) for COVID-19 once a vaccine is available for children? | Yes [Y], unsure [U], no [N] | Yes: 74.0 |

| Unsure: 14.0 | |||

| No: 12.0 | |||

| (McKinnon et al., 2021) | If a COVID-19 vaccine is available, will you vaccinate your child? | Very likely [Y], somewhat likely [U], unlikely [N] | Yes: 73.3 |

| Unsure: 14.3 | |||

| No: 12.4 | |||

| (Shmueli, 2021) | How appropriate do you consider to vaccinate your children against COVID-19? | A scale from 1 [not appropriate at all] to 6 [very appropriate, Y] | Yes: 57.2 |

| Unsure: NR | |||

| No: NR |

NR: not reported.

[Y], [N] and [U] indicate extracted response options representing yes, no and unsure in this meta-analysis.

3.3. Quality assessment

Quality assessment of cross-sectional studies included in this review is shown in Supplementary Table S1. Quality was good in 37 studies, moderate in six studies, and low in one study.

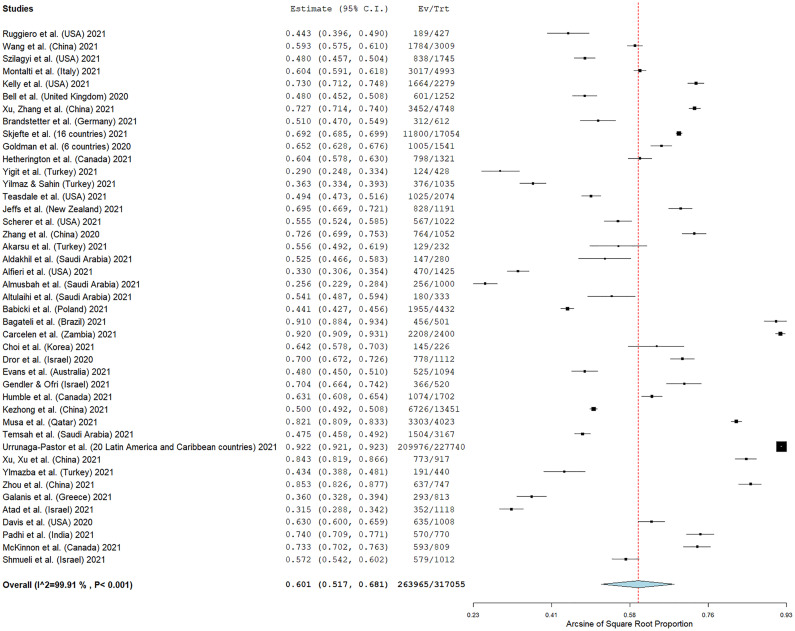

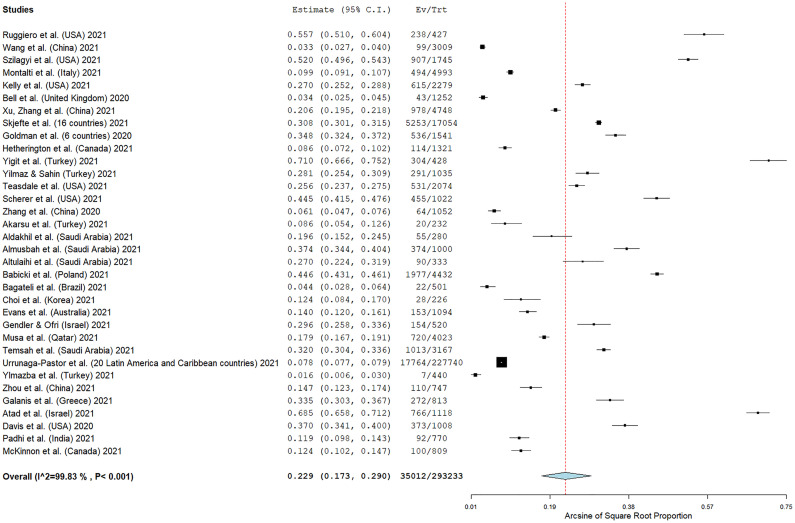

3.4. Parents' willingness and refusal to vaccinate their children

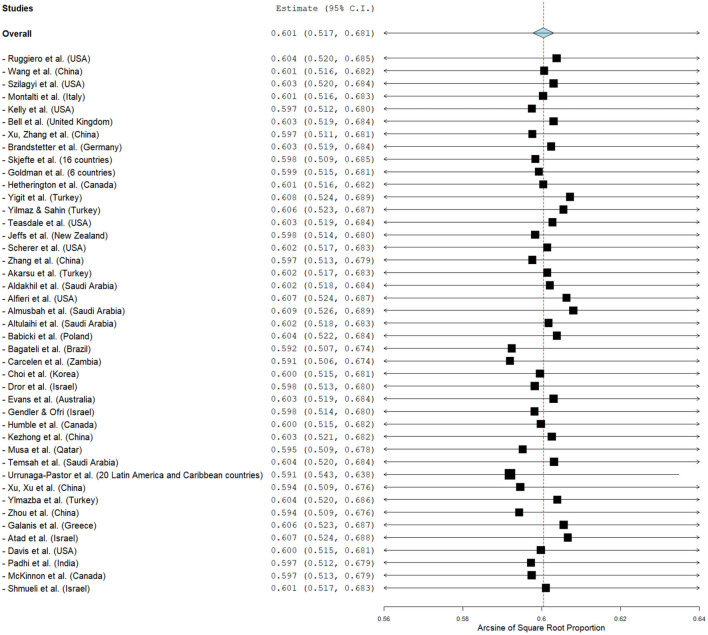

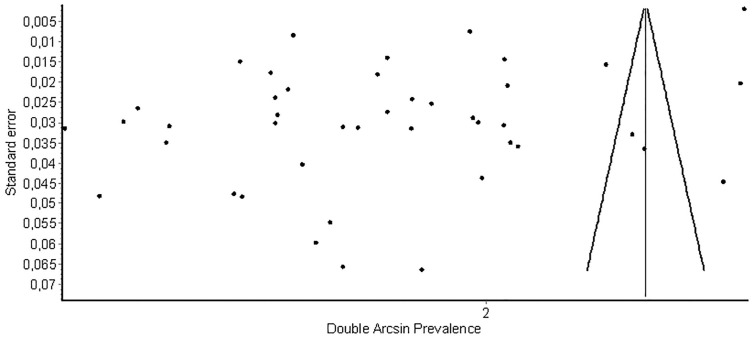

Forty-three studies reported the number of parents that intend to vaccinate their children, while one study measured parents' willingness in a scale from 0 to 100. The overall proportion of parents that intend to vaccinate their children against the COVID-19 was 60.1% (95% CI: 51.7–68.1%) (Fig. 2). The heterogeneity between results was very high (I2 = 99.91%, p-value for the Hedges Q statistic < 0.001). Parents' willingness ranged from 25.6% to 92.2%. A leave-one-out sensitivity analysis showed that no single study had a disproportional effect on the overall proportion, which varied between 59.1% (95% CI: 50.6–67.4%), and 60.9% (95% CI: 52.6–68.9%) (Supplementary Fig. S1). p-value for Egger's test (<0.05) and funnel plot (Supplementary Fig. S2) indicated potential publication bias.

Fig. 2.

Forest plot of parents' willingness to vaccinate their children against the COVID-19.

Supplementary Fig. S1.

Leave-one-out sensitivity analysis for parents' willingness to vaccinate their children against the COVID-19.

Supplementary Fig. S2.

Funnel plot for parents' willingness to vaccinate their children against the COVID-19.

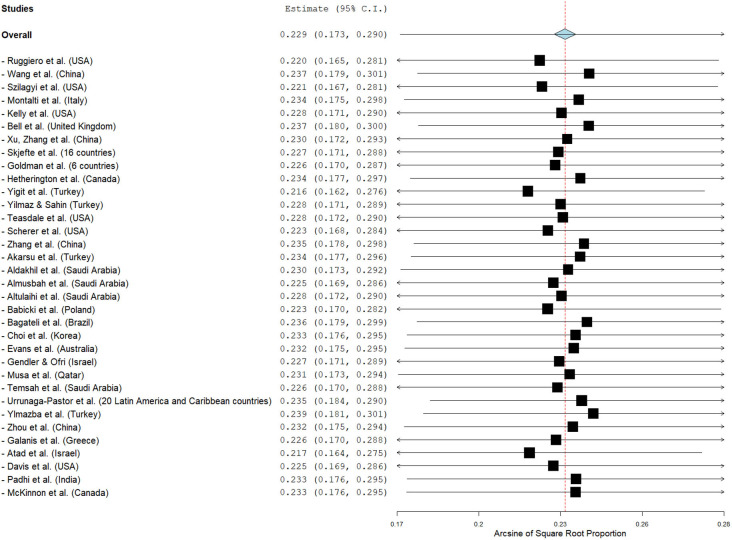

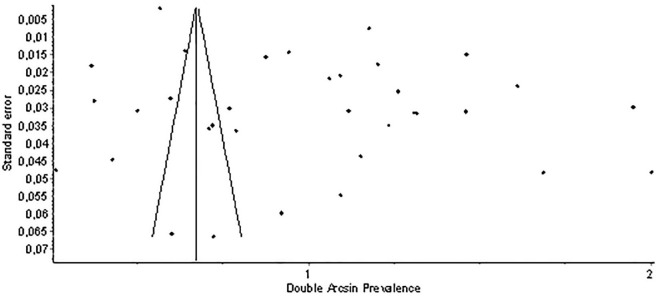

Thirty-four studies reported data on parents' refusal to vaccinate their children. The pooled proportion of parents that refuse to vaccinate their children was 22.9% (95% CI: 17.3–29.0%) (Fig. 3). The heterogeneity between results was very high (I2 = 99.83%, p-value for the Hedges Q statistic < 0.001). Parents' refusal ranged from 1.6% to 71.0%. A leave-one-out sensitivity analysis showed that no single study had a disproportional effect on the overall proportion, which varied between 21.6% (95% CI: 16.2–27.6%) and 23.9% (95% CI: 18.1–30.1%) (Supplementary Fig. S3). p-value for Egger's test (<0.05) and funnel plot (Supplementary Fig. S4) indicated potential publication bias.

Fig. 3.

Forest plot of parents' refusal to vaccinate their children against the COVID-19.

Supplementary Fig. S3.

Leave-one-out sensitivity analysis for parents' refusal to vaccinate their children against the COVID-19.

Supplementary Fig. S4.

Funnel plot for parents' refusal to vaccinate their children against the COVID-19.

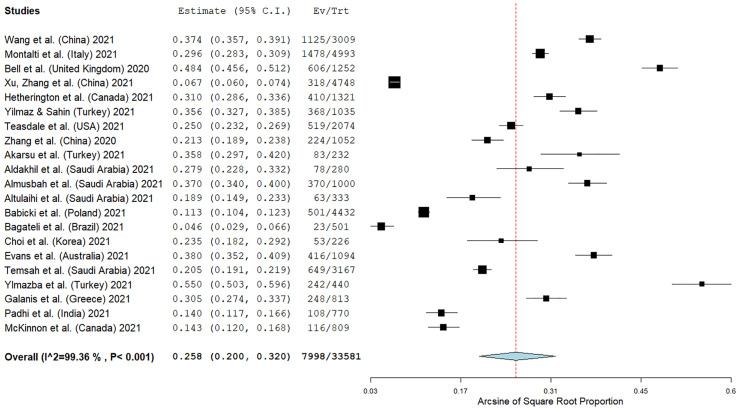

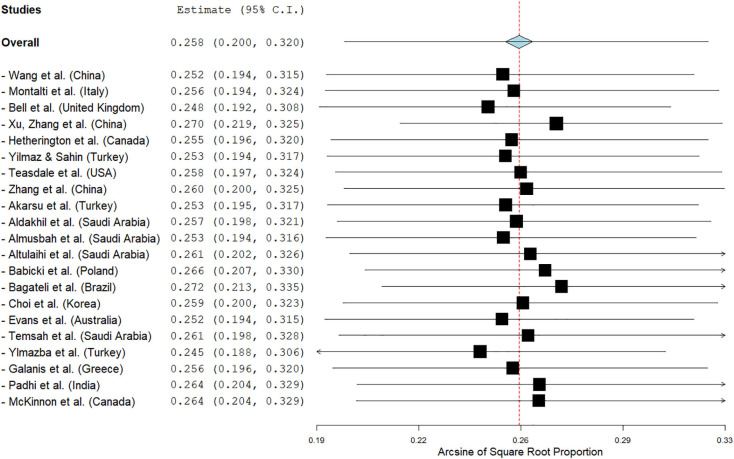

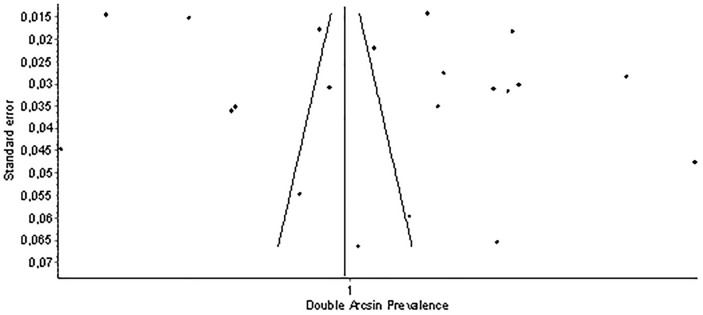

Twenty-one studies presented the number of parents reporting unsure of their children's vaccination against the COVID-19. The pooled proportion of unsure parents was 25.8% (95% CI: 20.0–32.0%) (Fig. 4). The heterogeneity between results was very high (I2 = 99.36%, p-value for the Hedges Q statistic < 0.001). Proportion of unsure parents ranged from 4.6% to 55.0%. A leave-one-out sensitivity analysis showed that no single study had a disproportional effect on the overall proportion, which varied between 24.5% (95% CI: 18.8–30.6%) and 27.2% (95% CI: 21.3–33.5%) (Supplementary Fig. S5). p-value for Egger's test (<0.05) and funnel plot (Supplementary Fig. S6) indicated potential publication bias.

Fig. 4.

Forest plot of parents reporting unsure of their children's vaccination against the COVID-19.

Supplementary Fig. S5.

Leave-one-out sensitivity analysis for parents reporting unsure of their children's vaccination against the COVID-19.

Supplementary Fig. S6.

Funnel plot for parents reporting unsure of their children's vaccination against the COVID-19.

3.5. Presence vs. absence of an “unsure” response option

When “unsure” was a response option for the parents the overall proportion of parents that intend to vaccinate their children was lower (58.3%, 95% CI = 52.7–63.8%, I2 = 99.45%) than in studies where there was no “unsure” response option (64.5%, 95% CI = 51.6–76.5%, I2 = 99.91%). Difference was larger in case of parents' refusal to vaccinate their children. In particular, when there was the “unsure” response option the pooled proportion of parents that refuse to vaccinate their children was 16.9% (95% CI = 11.1–23.6%, I2 = 99.60%), and when “unsure” was not a response option the proportion was 35.5% (95% CI = 23.5–48.4%, I2 = 99.91%).

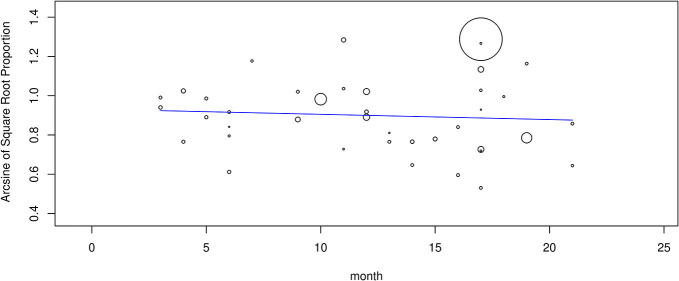

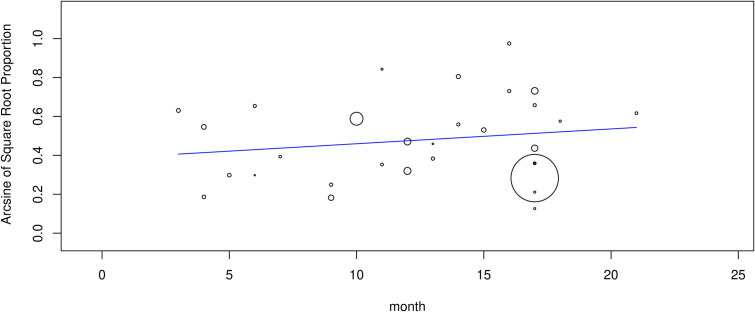

3.6. Time trends

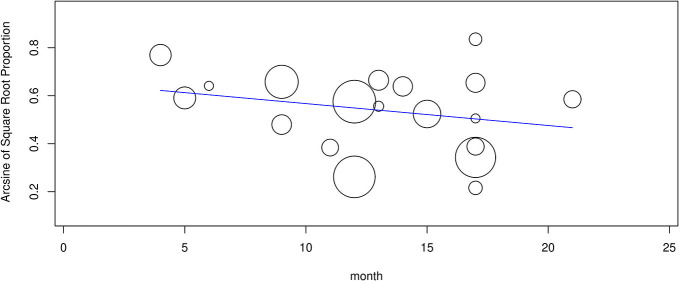

Meta-regression analysis showed that parents' willingness to vaccinate their children was independent data collection time (coefficient = −0.003, 95% CI = −0.014 to 0.008, p = 0.63) (Supplementary Fig. S7). Similarly, there was not a relation between intention of parents not to vaccinate their children and month study was conducted (coefficient = 0.008, 95% CI = −0.007 to 0.022, p = 0.32) (Supplementary Fig. S8). Moreover, there was no relation between proportion of parents being unsure about their children's vaccination and month of study (coefficient = −0.009, 95% CI = −0.024 to 0.006, p = 0.24) (Supplementary Fig. S9).

Supplementary Fig. S7.

Meta-regression analysis between parents' willingness to vaccinate their children and data collection time.

Supplementary Fig. S8.

Meta-regression analysis between parents' refusal to vaccinate their children and data collection time.

Supplementary Fig. S9.

Meta-regression analysis between parents reporting unsure of their children's vaccination and data collection time.

Also, we analyzed the time trend separately for studies with an “unsure” response option and those without this response option and we confirmed that data collection time did not affect parents' intentions. Specifically, there was not a relation between intention of parents to vaccinate their children and data collection time in studies with an “unsure” response option (coefficient = −0.003, 95% CI = −0.015 to 0.010, p = 0.68), as well as in studies without an “unsure” response option (coefficient = −0.001, 95% CI = −0.021 to 0.020, p = 0.97). We found evidence that data collection time affected parents' refusal to vaccinate their children. Specifically, over time intention not to vaccinate increased in studies with an “unsure” response option (coefficient = 0.02, 95% CI = 0.003–0.036, p = 0.018). On the other hand, data collection time did not affect parents' refusal to vaccinate their children in studies without an “unsure” response option (coefficient = 0.001, 95% CI = −0.020 to 0.021, p = 0.97).

3.7. Risk of bias analysis

The pooled proportion of parents that intend to vaccinate their children was higher in studies with high quality (62.0%, 95% CI = 53.1–70.4%, I2 = 99.92%) than in studies with low/moderate quality (50.1%, 95% CI = 31.8–68.3%, I2 = 99.4%). Similarly, the pooled proportion of parents that refuse to vaccinate their children was 21.6% (95% CI = 15.9–28.0%, I2 = 99.84%) in studies with high quality and 28.0% (95% CI = 9.1–52.3%, I2 = 99.67%) in studies with low/moderate quality.

Parents' willingness to vaccinate their children was higher in journal articles (60.7%, 95% CI = 51.8–69.3%, I2 = 99.92%) than in pre-prints (56.1%, 95% CI = 41.1–70.5%, I2 = 99.23%). Moreover, parents' refusal was higher in pre-prints (31.1%, 95% CI = 12.4–53.8%, I2 = 99.6%) than in journal articles (21.6%, 95% CI = 15.9–27.8%, I2 = 99.84%).

We found evidence that recruitment method affected parents' willingness to vaccinate their children. When data were collected through online surveys the proportion was 57.2% (95% CI = 47.2–66.9%, I2 = 99.93%), and when data were collected through questionnaires in clinical settings the proportion was 69.2% (95% CI = 57.2–80.0%, I2 = 99.49%). Similarly, when data were collected through online surveys the proportion of parents that refuse to vaccinate their children was 23.8% (95% CI = 17.1–31.3%, I2 = 99.86%), and when data were collected through questionnaires in clinical settings the proportion was 20.4% (95% CI = 10.2–33.1%, I2 = 99.51%).

There was evidence of differences in findings between studies in North America, Asia, and Europe. In particular, the proportion of parents that intend to vaccinate their children in studies that were conducted in Asia was 58.5% (95% CI = 51.0–65.9%, I2 = 99.52%), in North America was 56.5% (95% CI = 48.2–64.6%, I2 = 98.97), and in Europe was 47.9% (95% CI = 39.0–56.9%, I2 = 98.84%). Additionally, the proportion of parents that refuse to vaccinate their children in studies that were conducted in North America was 31.5% (95% CI = 20.5–43.6%, I2 = 99.41%), in Asia was 21.8% (95% CI = 14.1–30.5%, I2 = 99.55%), and in Europe was 20.0% (95% CI = 4.0–44.1%, I2 = 99.86%).

3.8. Predictors of parents' willingness to vaccinate their children against COVID-19

Thirty-nine studies investigated factors that affect parents' willingness to vaccinate their children against COVID-19 (Table 3a,b). Thirty-two studies used multivariable analysis eliminating confounders, while seven studies used univariate analysis.

Table 3.

Studies examining factors related with parents' willingness to vaccinate their children against the COVID-19.

| (a) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reference | Older children | Older parents | Fathers | Higher educational level | Ethnicity | Higher income | Health insurance | Increased number of children | Children with chronic illness | Higher risk perception of getting infected | Increased perceived threat from the COVID-19 | Psychological distress | Trust in public health agencies/health science/physicians |

| (Ruggiero et al., 2021) | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | ↑ | – | – | – | – |

| (Wang et al., 2021a) | – | NS | NS | ↓ | – | NS | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| (Szilagyi et al., 2021) | ↑ | – | NS | ↑ | NS | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| (Montalti et al., 2021) | – | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| (Kelly et al., 2021) | – | NS | ↑ | ↑ | ↓ (Black parents) | ↑ | NS | – | NS | ↑ | ↑ | – | – |

| (Bell et al., 2020a) | – | NS | – | – | ↓ (parents from Black, Asian or minority ethnic groups) | NS | – | ↑ | – | – | – | – | – |

| (Xu et al., 2021c) | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | ↓ | |

| (Brandstetter et al., 2021) | – | NS | – | ↑ | NS | – | – | – | – | NS | NS | – | NS |

| (Skjefte et al., 2021) | – | NS | – | NS | – | ↑ | NS | NS | – | – | ↑ | – | ↑ |

| (Goldman et al., 2020) | ↑ | – | ↑ | NS | – | – | – | – | ↓ | – | – | – | – |

| (Hetherington et al., 2021) | – | NS | – | ↑ | NS | ↑ | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| (Yigit et al., 2021) | – | NS | ↑ | ↓ | – | – | – | – | NS | – | – | ↓ | – |

| (Yilmaz and Sahin, 2021) | – | NS | – | NS | – | NS | – | NS | – | – | ↑ | – | – |

| (Teasdale et al., 2021) | – | NS | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ (Asian parents) | ↑ | NS | NS | – | – | – | – | – |

| (Scherer et al., 2021) | – | NS | ↑ | ↑ | ↓ (Black parents) | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| (Zhang et al., 2020) | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| (Akarsu et al., 2021) | – | NS | NS | ↑ | – | NS | ↑ | – | NS | – | – | NS | – |

| (Aldakhil et al., 2021) | NS | NS | – | ↑ | – | – | – | NS | – | – | – | – | – |

| (Alfieri et al., 2021) | – | – | – | ↑ | ↓ (Black parents) | ↑ | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| (Almusbah et al., 2021) | NS | – | ↑ | – | – | – | – | – | NS | – | – | – | – |

| (Altulaihi et al., 2021) | ↑ | ↑ | NS | NS | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| (Babicki et al., 2021) | NS | ↑ | NS | – | – | – | – | NS | NS | – | ↑ | – | – |

| (Bagateli et al., 2021) | NS | ↑ | NS | ↑ | NS | ↑ | – | ↓ | – | – | – | – | – |

| (Choi et al., 2021) | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | NS | NS | – | – | – |

| (Evans et al., 2021) | – | – | NS | NS | – | NS | – | – | NS | – | – | NS | ↑ |

| (Humble et al., 2021) | – | NS | NS | NS | NS | – | – | – | – | NS | NS | – | – |

| (Kezhong et al., 2021) | ↓ | NS | – | ↓ | – | NS | – | NS | – | – | – | – | – |

| (Lackner and Wang, 2021) | NS | ↑ | NS | NS | – | NS | – | – | – | – | – | NS | – |

| (Musa et al., 2021) | ↓ | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | NS | – | – | – | – |

| (Temsah et al., 2021) | ↑ | ↑ | NS | ↓ | – | NS | – | ↑ | – | – | – | – | – |

| (Urrunaga-Pastor et al., 2021) | NS | ↑ | NS | ↑ | – | ↓ | – | – | – | – | – | ↑ | – |

| (Xu et al., 2021b) | NS | NS | NS | ↓ | – | ↓ | – | ↑ | – | – | – | – | – |

| (Zhou et al., 2021) | NS | NS | NS | ↓ | – | – | – | NS | – | – | – | – | – |

| (Galanis et al., 2021b) | – | ↑ | NS | NS | – | NS | – | – | – | – | ↑ | – | ↑ |

| (Atad et al., 2021) | – | – | – | ↑ | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| (Davis et al., 2020) | – | ↑ | NS | ↑ | ↑ (Hispanic parents) | NS | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| (Padhi et al., 2021) | NS | NS | ↑ | NS | – | – | – | NS | – | – | NS | ||

| (McKinnon et al., 2021) | NS | NS | NS | – | ↑ (White parents) | ↑ | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| (Shmueli, 2021) | – | ↑ | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | ↑ | – | – | – |

| Positive associationa | 4/16 | 10/25 | 7/24 | 15/29 | 3/12 (White [n = 1], Asian, [n = 1], and Hispanic [n = 1] parents) | 7/20 | 1/4 | 3/11 | 1/10 | 2/6 | 4/6 | 1/6 | 3/5 |

| Negative associationb | 2/16 | 0/25 | 0/24 | 6/29 | 4/12 (Black [n = 4] and Asian [n = 1] parents) | 2/20 | 0/4 | 1/11 | 1/10 | 0/6 | 0/6 | 2/6 | 0/5 |

| No associationc | 10/16 | 15/25 | 17/24 | 8/29 | 5/12 | 11/20 | 3/4 | 7/11 | 8/10 | 4/6 | 2/6 | 3/6 | 2/5 |

| (b) | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reference | Children's complete vaccination history | History of children's vaccination against influenza | History of parents' vaccination against influenza | Confidence in vaccines | Confidence in COVID-19 vaccines | Vaccination hesitancy | Concerns for serious side effects and effectiveness of COVID-19 vaccines | COVID-19 vaccine uptake/intention among parents | Information based in the web/social media | Compliance with prevention measures/knowledge about prevention measures | High level of information about the COVID-19 pandemic/vaccination | Level of analysis |

| (Ruggiero et al., 2021) | – | ↑ | – | ↑ | – | ↓ | ↓ | – | – | – | – | Multivariable |

| (Wang et al., 2021a) | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | Multivariable |

| (Szilagyi et al., 2021) | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | ↑ | – | – | – | Multivariable |

| (Montalti et al., 2021) | – | – | – | – | – | ↓ | – | – | ↓ | – | – | Multivariable |

| (Kelly et al., 2021) | – | – | ↑ | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | Multivariable |

| (Bell et al., 2020a) | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | Multivariable |

| (Xu et al., 2021c) | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | Multivariable |

| (Brandstetter et al., 2021) | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | ↑ | ↑ | Multivariable |

| (Skjefte et al., 2021) | ↑ | – | – | ↑ | ↑ | – | – | – | – | – | – | Multivariable |

| (Goldman et al., 2020) | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | Univariate |

| (Hetherington et al., 2021) | ↑ | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | Multivariable |

| (Yigit et al., 2021) | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | Univariate |

| (Yilmaz and Sahin, 2021) | – | – | – | – | ↑ | – | – | – | – | – | – | Multivariable |

| (Teasdale et al., 2021) | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | Multivariable |

| (Scherer et al., 2021) | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | Multivariable |

| (Zhang et al., 2020) | – | – | – | – | ↑ | – | – | – | – | – | ↑ | Multivariable |

| (Akarsu et al., 2021) | NS | – | ↑ | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | Univariate |

| (Aldakhil et al., 2021) | – | – | – | – | – | ↓ | – | – | – | – | – | Univariate |

| (Alfieri et al., 2021) | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | Multivariable |

| (Almusbah et al., 2021) | NS | – | ↑ | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | Univariate |

| (Altulaihi et al., 2021) | – | – | ↑ | – | – | – | – | – | NS | – | NS | Multivariable |

| (Babicki et al., 2021) | ↑ | – | – | – | – | – | ↓ | – | – | – | – | Multivariable |

| (Bagateli et al., 2021) | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | Univariate |

| (Choi et al., 2021) | – | – | – | – | ↑ | – | – | ↑ | – | – | – | Multivariable |

| (Evans et al., 2021) | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | Multivariable |

| (Humble et al., 2021) | NS | NS | – | – | ↑ | – | – | ↑ | – | – | – | Multivariable |

| (Kezhong et al., 2021) | – | – | – | – | – | ↓ | – | – | – | – | – | Multivariable |

| (Lackner and Wang, 2021) | ↑ | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | Multivariable |

| (Musa et al., 2021) | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | Multivariable |

| (Temsah et al., 2021) | – | – | – | – | – | ↓ | – | ↑ | – | – | – | Multivariable |

| (Urrunaga-Pastor et al., 2021) | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | ↑ | – | ↑ | – | Multivariable |

| (Xu et al., 2021b) | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | Multivariable |

| (Zhou et al., 2021) | – | – | ↑ | – | – | – | – | – | – | NS | – | Multivariable |

| (Galanis et al., 2021b) | – | – | ↑ | ↑ | – | – | ↓ | NS | – | – | ↑ | Multivariable |

| (Atad et al., 2021) | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | ↑ | – | – | – | Univariate |

| (Davis et al., 2020) | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | Multivariable |

| (Padhi et al., 2021) | – | – | – | – | – | NS | – | ↑ | – | – | – | Multivariable |

| (McKinnon et al., 2021) | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | Multivariable |

| (Shmueli, 2021) | – | ↑ | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | Multivariable |

| Positive associationa | 5/8 | 3/4 | 7/7 | 3/3 | 5/5 | 0/6 | 0/3 | 7/8 | 0/2 | 2/3 | 3/4 | |

| Negative associationb | 0/8 | 0/4 | 0/7 | 0/3 | 0/5 | 5/6 | 3/3 | 0/8 | 1/2 | 0/3 | 0/4 | |

| No associationc | 3/8 | 1/4 | 0/7 | 0/3 | 0/5 | 1/6 | 0/3 | 1/8 | 1/2 | 1/3 | 1/4 | |

NS: non-significant.

↑ more likely to vaccinate.

↓ less likely to vaccinate.

- not investigated.

Number of studies with a positive significant association (p-value < 0.05) between the predictor and parents' willingness to vaccinate their children against the COVID-19/total number of studies examined the predictor.

Number of studies with a negative significant association (p-value < 0.05) between the predictor and parents' willingness to vaccinate their children against the COVID-19/total number of studies examined the predictor.

Number of studies without a significant association (p-value ≥ 0.05) between the predictor and parents' willingness to vaccinate their children against the COVID-19/total number of studies examined the predictor.

Several sociodemographic characteristics affected parents' intention to vaccinate their children against COVID-19. In 10/25 studies older parents were more likely to intend to vaccinate their children than young parents, while 15 studies found no effect of age. In 7/24 studies, fathers were more likely to report intending to vaccinate than mother, while 17 studies did not find a significant association. Four studies out of 16 found that parents intend to vaccinate older children more often than younger children, but two studies found the opposite and 10 studies found no effect of children's age. Higher income was associated with parents' willingness to vaccinate their children in 7/20 studies, while two studies found the opposite relation and 11 studies found no effect of income. Educational level was a controversial issue, since in 15/29 studies higher educational level was associated with intending to vaccinate, but in 6/29 studies lower educational level was associated with intending to vaccinate (no association in eight studies). With regards to ethnicity, Black parents were less likely to intend to vaccinate their children (4/12 studies), while White parents (one study) and Hispanic parents (one study) were more likely to intend to vaccinate their children (no association in five studies). Health insurance, increased number of children, and children with chronic illness were non-significant predictors in 3/4, 7/11, and 8/10 studies respectively.

Positive attitudes regarding vaccination affected positively parents' intention to vaccinate their children against COVID-19. In particular, children's complete vaccination history (5/8 studies; no association in three studies), history of children's vaccination against influenza (3/4 studies; no association in one study), history of parents' vaccination against influenza (7/7 studies), confidence in vaccines (3/3 studies), confidence in COVID-19 vaccines (5/5 studies), and COVID-19 vaccine uptake/intention among parents (7/8 studies; no association in one study) were associated with increased intended uptake of a COVID-19 vaccine. On the other hand, overall vaccination hesitancy (5/6 studies; no association in one study), and concerns for serious side effects and effectiveness of COVID-19 vaccination (3/3 studies) decreased parents' willingness to vaccinate their children.

Moreover, higher levels of perceived threat from the COVID-19 (4/6 studies; no association in two studies), compliance with prevention measures (2/3 studies; no association in one study), trust in public health agencies/health science/physicians (3/5 studies; no association in two studies), and high level of information about the COVID-19 pandemic/vaccination (3/4 studies; no association in one study) were associated with parents' intention to accept COVID-19 vaccination for their children.

4. Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first systematic review and meta-analysis that assesses the willingness and the refusal of parents to vaccinate their children against the COVID-19 and investigates the predictors for their decision. Forty-four papers including 317,055 parents met our inclusion criteria. The primary reasons that papers were excluded from our systematic review include irrelevant research questions and other types of publications (e.g. reviews, qualitative studies, case reports, protocols, etc.).

4.1. Parents' willingness and refusal to vaccinate their children

We found that the overall proportion of parents that intend to vaccinate their children against the COVID-19 is moderate (60.1%) with a wide range among studies from 25.6% to 92.2%. Parents' intention to vaccinate their children against the COVID-19 is lower than the intention of the general population to take a COVID-19 vaccine (60.1% vs. 73%) (Snehota et al., 2021; Wang et al., 2021b). This finding is confirmed by a meta-analysis of large nationally representative samples where 72.9% of the general population intend to vaccinate against the COVID-19, 14.3% intend to refuse vaccination, and 22.1% were unsure (Robinson et al., 2021). Similarly, in our study 60.1% of parents intend to vaccinate their children, 22.9% intend to refuse vaccination, and 25.8% were unsure. Intentions and refusals vary substantially between studies included in both meta-analyses. Also, the willingness of high-risk groups such as healthcare workers to accept COVID-19 vaccination is higher than parents' willingness to vaccinate their children (63.5% vs. 60.1%) (Galanis et al., 2021; Luo et al., 2021). A possible explanation for the lower overall intention of parents to vaccinate their children against the COVID-19 demonstrated by our meta-analysis could be the perception of a very low risk of severe COVID-19 in children and the fact that children are often asymptomatic carriers. The wide range of parents' willingness among studies is confirmed by similar reviews in the general population and could be due to different study designs, study populations, levels of knowledge and information, attitudes towards vaccination, etc. (Galanis et al., 2021a; Snehota et al., 2021; Wang et al., 2021b).

4.2. Sub-group analysis

Interestingly, we found differences in parents' willingness to vaccinate their children according to the continent that studies were conducted. In general, acceptance of COVID-19 vaccination for children is higher among parents from Asia than those from North America and Europe. On the other hand, refusal of COVID-19 vaccination is higher among parents from North America than those from Asia and Europe.

Moreover, subgroup analysis identified that recruitment method affected parents' intention to vaccinate their children. In particular, parents' willingness was higher in studies where data were collected through questionnaires in clinical settings than in studies where data were collected through online surveys. Also, the proportion of parents that refuse to vaccinate their children was lower in studies that were conducted in clinical settings than in studies that were conducted online.

Another interesting finding of our meta-analysis is the effect of the “unsure” response option in surveys. In particular, the presence of the “unsure” response option decreased both the intention of parents to accept a COVID-19 vaccine for their children and their refusal. A recent meta-analysis of samples from the general population confirms this finding since when there was no “unsure” response option the proportion of participants intending to vaccinate was 82.8%, and when there was an “unsure” response option the proportion was 63.5% (Robinson et al., 2021). Also, when there was no “unsure” response option the proportion intending to refuse a COVID-19 vaccine was 17.2%, while when there was an “unsure” response option the proportion was 12.4%.

It is noteworthy that our meta-regression analysis revealed that data collection time does not affect parents' intention and refusal to vaccinate their children but studies of current and ongoing attitudes towards COVID-19 vaccination should be conducted since information and knowledge about COVID-19 vaccines are still evolving. In that case, the only significant relation we found was that over time intention not to vaccinate increased in studies with an “unsure” response option.

4.3. Predictors of parents' willingness to vaccinate their children against COVID-19

According to our review, several sociodemographic characteristics affect parents' willingness to vaccinate their children against COVID-19. In particular, mothers and younger parents were more hesitant, a finding that is confirmed by the literature since females and younger individuals are in general more likely to report vaccine hesitancy (Galanis et al., 2021a; Lin et al., 2020b; Neumann-Böhme et al., 2020; Schwarzinger et al., 2021). This could be due to the fact that males and older individuals, reported being at higher risk of intensive care unit admission and death from COVID-19, and so could be more prone to vaccination (Bienvenu et al., 2020; Peckham et al., 2020). On the other hand, females tend to experience more adverse events after COVID-19 vaccination and their vaccine hesitancy may be related to poor knowledge regarding issues such as fertility, pregnancy, and breastfeeding (Schrading et al., 2021; Xu et al., 2021a). Therefore, mothers could be more worried about potential side effects of the COVID-19 vaccines in their children, and thus are more reluctant to vaccinate their children.

Moreover, we found that educational level is a controversial issue regarding parents' intention to accept a COVID-19 vaccine for their children. The impact of parents' educational level on vaccine hesitancy is debatable since previous studies have shown that lower educational level is associated with more concerns about vaccine safety and efficacy (Gust et al., 2003; Shui et al., 2006; Smith et al., 2004), but other studies found the opposite (Opel et al., 2011). Also, a higher level of parents' education is related to higher confidence towards vaccination by giving more tools for decision-making (Bocquier et al., 2018; Gualano et al., 2018; Kempe et al., 2020), but higher educated parents are more likely to forego immunizations (Gilkey et al., 2013; Smith et al., 2011).

Our review revealed that parents from Black, Asian and minority ethnic groups are less willing than White parents to vaccinate their children against COVID-19. This is consistent with a systematic review which shows that COVID-19 vaccination uptake is higher among individuals from White race than individuals from Black race (Galanis et al., 2021a). Also, individuals from Black, Asian and minority ethnic groups have a lower level of COVID-19 vaccine acceptability (Funk and Tyson, 2021; Hamel et al., 2021; Malik et al., 2020; Ruiz and Bell, 2021) and they have lower seasonal influence vaccine coverage (Williams et al., 2017). Given that people from Black, Asian and minority ethnic groups are at higher risk of acquiring SARS-CoV-2 infection and at increased risk of adverse outcomes from COVID-19, a concerted effort must be made to minimize inequalities in COVID-19 vaccination uptake and ensure equitable access to the COVID-19 vaccines (Martin et al., 2020; Sze et al., 2020; Voysey et al., 2021).

We found that parents' positive attitudes towards vaccination affect their decision to vaccinate their children against COVID-19. In particular, parents whose children had recently received the influenza vaccination or had a completed vaccination history reported a higher likelihood of COVID-19 vaccination for their children. During the COVID-19 pandemic, an important predictor of future behavior remains past behavior (Bourassa et al., 2020). Past behavior predicts future behavior in a direct pathway, where a habitual process occurring, or in an indirect pathway via conscious, intentional processes (Ouellette and Wood, 1998; Schwarzer and Hamilton, 2020). For instance, several studies have identified the relationship between individuals' vaccination in the past and uptake of the pandemic H1N1 vaccine (Bish et al., 2011; Rubin et al., 2011; Setbon and Raude, 2010; Torun et al., 2010). This pattern is similar to our finding that COVID-19 vaccine uptake among parents is associated with increased intended uptake of a COVID-19 vaccine among children. Moreover, the COVID-19 pandemic seems to increase the polarization of parents' vaccination behaviors since parents who did not vaccinate their children in the past reported becoming even less likely to vaccinate them in the near future (Sokol and Grummon, 2020).

According to our review, confidence in vaccination, concerns for serious side effects and effectiveness of vaccines, and vaccine hesitancy are significant predictors of parents' attitudes regarding vaccination. These findings are confirmed by the literature since parents in the USA are hesitant to vaccinate their children with routine immunizations because of safety, side effects and low effectiveness concerns (Kempe et al., 2020; Nyhan and Reifler, 2015). Vaccine hesitancy is a complex issue and one of the main obstacles to control the COVID-19 pandemic since an instrumental percentage of the general population refuses COVID-19 vaccines (Jaca et al., 2021; Wiysonge et al., 2021). Unfortunately, providing information on vaccine safety and effectiveness to individuals who are vaccine-hesitant can be counterproductive (Nyhan et al., 2014; Nyhan and Reifler, 2015; L. D. Scherer et al., 2016). Tailored and targeted communication materials and balanced information on vaccines providing both the benefits and risks of vaccination are necessary to optimize vaccine uptake (Dubé et al., 2015; Dubé et al., 2020). A robust, transparent, reasonable, and widespread COVID-19 vaccine educational campaign harnessing media, healthcare workers, leaders, and social influencers should be implemented by the public health officials to diminish parents' concerns for COVID-19 vaccine safety and efficacy (Schaffer DeRoo et al., 2020). Also, behavioral-change theories (e.g., the health-belief model) have already been effectively adapted to improve individual medical use and should be used by government and health authorities to curb COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy among parents (Lin et al., 2020a; Opel et al., 2009).

Since COVID-19 vaccine safety and effectiveness are key parental concerns, it is critical to emphasize the safety profile of COVID-19 vaccines for children based on evidence from randomized controlled trials and post-approval data. Well-informed parents experience less worry, fear, and anxiety about COVID-19 and are more likely to receive a COVID-19 vaccine for their children as suggested by our review. The rigorous development and approval process of COVID-19 vaccines by the federal agencies worldwide increase parents' concerns and there is a need for continued transparency and active public education regarding the development of the COVID-19 vaccines (Bell et al., 2020b; Lee et al., 2020). In that case, the role of primary care physicians to communicate about COVID-19 vaccines for children is critical since prior studies show that clear messages and recommendations by primary care physicians have a large impact on vaccine uptake (Braun and O'Leary, 2020; Dempsey and O'Leary, 2018; Edwards et al., 2016).

5. Limitations

This systematic review has several limitations. In particular, the statistical heterogeneity was very high due probably to heterogeneity in study designs and populations. To account for this heterogeneity, we applied a random effects model and we performed subgroup and meta-regression analysis. At least, subgroup analysis and leave-one-out sensitivity analysis revealed that our results are robust. We searched for studies conducted until to December 12, 2021, but the availability of COVID-19 vaccines and evidence from randomized controlled trials and post-approval data are increasing on an ongoing basis and parents' attitudes could be changed. Thus, our findings may not be generalizable to later in the COVID-19 pandemic. Since all studies in our review were cross-sectional, we cannot infer causal relationships between parents' willingness to vaccinate their children against the COVID-19 and predictors of this attitude. Additionally, we included in our review articles in pre-print services which do not apply peer-review process. Thus, articles in pre-print services could be of low quality. To overcome this limitation, we assessed studies quality and we performed subgroup analysis according to studies quality and publication type. We consider predictors of parents' intention to vaccinate their children as a potential area for future study since only sociodemographic variables have so far been investigated thoroughly. Future studies should assess broader and diverse parent populations to fully understand the factors that affect parents' intention to vaccinate their children against the COVID-19. Finally, the proportion of parents that agreed to vaccinate their children against the COVID-19 may be a biased estimation since studies measured willingness and not COVID-19 vaccination uptake.

6. Conclusions

High vaccination coverage is indispensable to control the COVID-19 pandemic. Given the highly transmissible delta and omicron variants, COVID-19 vaccination coverage should be increased to achieve herd immunity to COVID-19. This is the main reason that the COVID-19 vaccine rollout is expanding to the children population. Thus, it is critical to better understand what factors affect parents' decision to vaccinate their children against COVID-19. Understanding parental COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy does help policymakers to change the stereotypes and establish broad community COVID-19 vaccination. As global COVID-19 vaccines rollout continue, our review could help policy makers and healthcare workers to understand parental decision around COVID-19 vaccination. This information can be used for evidence-based targeted campaigns and health interventions to ultimately maximize future COVID-19 vaccine uptake among children. There is a need to build vaccine confidence during the COVID-19 pandemic through clear messages and effective community engagement. Targeted public health strategies should aim to assuage parents' concerns regarding COVID-19 vaccines. Identification of the factors that affect parents' willingness to vaccinate their children against COVID-19 will provide opportunities to enhance parents' trust in the COVID-19 vaccines and optimize children's uptake of a COVID-19 vaccine.

Funding

None.

Conflicts of interest

None.

The following are the supplementary data related to this article.

Quality of studies included in this systematic review.

References

- Akarsu B., Canbay Özdemir D., Ayhan Baser D., Aksoy H., Fidancı İ., Cankurtaran M. While studies on COVID-19 vaccine is ongoing, the public’s thoughts and attitudes to the future COVID-19 vaccine. Int. J. Clin. Pract. 2021;75(4) doi: 10.1111/ijcp.13891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Amer R., Maneze D., Everett B., Montayre J., Villarosa A.R., Dwekat E., Salamonson Y. COVID-19 vaccination intention in the first year of the pandemic: a systematic review. J. Clin. Nurs. 2021 doi: 10.1111/jocn.15951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aldakhil H., Albedah N., Alturaiki N., Alajlan R., Abusalih H. Vaccine hesitancy towards childhood immunizations as a predictor of mothers’ intention to vaccinate their children against COVID-19 in Saudi Arabia. J. Infect. Public Health. 2021;14(10):1497–1504. doi: 10.1016/j.jiph.2021.08.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alfieri N.L., Kusma J.D., Heard-Garris N., Davis M.M., Golbeck E., Barrera L., Macy M.L. Parental COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy for children: vulnerability in an urban hotspot. BMC Public Health. 2021;21(1):1662. doi: 10.1186/s12889-021-11725-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Almusbah Z., Alhajji Z., Alshayeb Z., Alhabdan R., Alghafli S., Almusabah M., Almuqarrab F., Aljazeeri I., Almuhawas F. Caregivers’ willingness to vaccinate their children against COVID-19 in Saudi Arabia: a cross-sectional survey. Cureus. 2021 doi: 10.7759/cureus.17243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altulaihi B.A., Alaboodi T., Alharbi K.G., Alajmi M.S., Alkanhal H., Alshehri A. Perception of parents towards COVID-19 vaccine for children in Saudi population. Cureus. 2021 doi: 10.7759/cureus.18342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Academy of Pediatrics Children and COVID-19: State-Level Data Report. 2021. https://www.aap.org/en/pages/2019-novel-coronavirus-covid-19-infections/children-and-covid-19-state-level-data-report/

- Atad E., Netzer I., Peleg O., Landsman K., Dalyot K., Reuven S.E., Baram-Tsabari A. Vaccine-hesitant parents’ considerations regarding Covid-19 vaccination of adolescents [Preprint] Pediatrics. 2021 doi: 10.1101/2021.05.25.21257780. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Babicki M., Pokorna-Kałwak D., Doniec Z., Mastalerz-Migas A. Attitudes of parents with regard to vaccination of children against COVID-19 in Poland. A nationwide online survey. Vaccines. 2021;9(10):1192. doi: 10.3390/vaccines9101192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bagateli L.E., Saeki E.Y., Fadda M., Agostoni C., Marchisio P., Milani G.P. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy among parents of children and adolescents living in Brazil. Vaccines. 2021;9(10):1115. doi: 10.3390/vaccines9101115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barendregt J.J., Doi S.A., Lee Y.Y., Norman R.E., Vos T. Meta-analysis of prevalence. J. Epidemiol. Community Health. 2013;67(11):974–978. doi: 10.1136/jech-2013-203104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartsch S.M., O’Shea K.J., Ferguson M.C., Bottazzi M.E., Wedlock P.T., Strych U., McKinnell J.A., Siegmund S.S., Cox S.N., Hotez P.J., Lee B.Y. Vaccine efficacy needed for a COVID-19 Coronavirus vaccine to prevent or stop an epidemic as the sole intervention. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2020;59(4):493–503. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2020.06.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell S., Clarke R., Mounier-Jack S., Walker J., Paterson P. Parents’ and guardians’ views on the acceptability of a future COVID-19 vaccine: a multi-methods study in England. Vaccine. 2020;38(49):7789–7798. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2020.10.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell B.P., Romero J.R., Lee G.M. Scientific and ethical principles underlying recommendations from the advisory committee on immunization practices for COVID-19 vaccination implementation. JAMA. 2020;324(20):2025–2026. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.20847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bienvenu L.A., Noonan J., Wang X., Peter K. Higher mortality of COVID-19 in males: sex differences in immune response and cardiovascular comorbidities. Cardiovasc. Res. 2020;116(14):2197–2206. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvaa284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bish A., Yardley L., Nicoll A., Michie S. Factors associated with uptake of vaccination against pandemic influenza: a systematic review. Vaccine. 2011;29(38):6472–6484. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.06.107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bocquier A., Fressard L., Cortaredona S., Zaytseva A., Ward J., Gautier A., Peretti-Watel P., Verger P., Baromètre santé 2016 group Social differentiation of vaccine hesitancy among French parents and the mediating role of trust and commitment to health: a nationwide cross-sectional study. Vaccine. 2018;36(50):7666–7673. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2018.10.085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourassa K.J., Sbarra D.A., Caspi A., Moffitt T.E. Social distancing as a health behavior: county-level movement in the United States during the COVID-19 pandemic is associated with conventional health behaviors. Ann. Behav. Med. 2020;54(8):548–556. doi: 10.1093/abm/kaaa049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandstetter S., Bohmer M., Pawellek M., Seelbach-Gobel B., Melter M., Kabesch M., Apfelbacher C., KUNO-Kids Study Grp Parents’ intention to get vaccinated and to have their child vaccinated against COVID-19: cross-sectional analyses using data from the KUNO-Kids health study. Eur. J. Pediatr. 2021 doi: 10.1007/s00431-021-04094-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braun C., O’Leary S.T. Recent advances in addressing vaccine hesitancy. Curr. Opin. Pediatr. 2020;32(4):601–609. doi: 10.1097/MOP.0000000000000929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carcelen A.C., Prosperi C., Mutembo S., Chongwe G., Mwansa F.D., Ndubani P., Simulundu E., Chilumba I., Musukwa G., Thuma P., Kapungu K., Hamahuwa M., Mutale I., Winter A., Moss W.J., Truelove S.A. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy in Zambia: a glimpse at the possible challenges ahead for COVID-19 vaccination rollout in sub-Saharan Africa. Hum. Vaccines Immunotherapeutics. 2021;1–6 doi: 10.1080/21645515.2021.1948784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi S.-H., Jo Y.H., Jo K.J., Park S.E. Pediatric and parents’ attitudes towards COVID-19 vaccines and intention to vaccinate for children. J. Korean Med. Sci. 2021;36(31) doi: 10.3346/jkms.2021.36.e227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis M.M., Zickafoose J.S., Halvorson A.E., Patrick S.W. Parents’ likelihood to vaccinate their children and themselves against COVID-19. Pediatrics. 2020 doi: 10.1101/2020.11.10.20228759. [Preprint] [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dempsey A.F., O’Leary S.T. Human papillomavirus vaccination: narrative review of studies on how providers’ vaccine communication affects attitudes and uptake. Acad. Pediatr. 2018;18(2S):S23–S27. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2017.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dror A.A., Eisenbach N., Taiber S., Morozov N.G., Mizrachi M., Zigron A., Srouji S., Sela E. Vaccine hesitancy: the next challenge in the fight against COVID-19. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 2020;35(8):775–779. doi: 10.1007/s10654-020-00671-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubé E., Gagnon D., MacDonald N.E., SAGE Working Group on Vaccine Hesitancy Strategies intended to address vaccine hesitancy: review of published reviews. Vaccine. 2015;33(34):4191–4203. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.04.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubé E., Gagnon D., Vivion M. Optimizing communication material to address vaccine hesitancy. Canada Communicable Disease Report = Releve Des Maladies Transmissibles Au Canada. 2020;46(2–3):48–52. doi: 10.14745/ccdr.v46i23a05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dyer O. Covid-19: Omicron is causing more infections but fewer hospital admissions than delta, South African data show. BMJ. 2021 doi: 10.1136/bmj.n3104. n3104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards K.M., Hackell J.M., Committee on Infectious Diseases, the Committee on Practice and Ambulatory Medicine Countering Vaccine Hesitancy. Pediatrics. 2016;138(3) doi: 10.1542/peds.2016-2146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]