Abstract

Bias toward historically marginalized patients affects patient-provider interactions and can lead to lower quality of care and poor health outcomes for patients who are Black, Indigenous, People of Color (BIPOC) and Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender and Gender Diverse (LGBTQ+). We gathered experiences with biased healthcare interactions and suggested solutions from 25 BIPOC and LGBTQ+ people. Through qualitative thematic analysis of interviews, we identified ten themes. Eight themes reflect the experience of bias: Transactional Care, Power Inequity, Communication Casualties, Bias-Embedded Medicine, System-level problems, Bigotry in Disguise, Fight or Flight, and The Aftermath. The remaining two themes reflect strategies for improving those experiences: Solutions and Good Experiences. Characterizing these themes and their interconnections is crucial to design effective informatics solutions that can address biases operating in clinical interactions with BIPOC and LGBTQ+ patients, improve the quality of patient-provider interactions, and ultimately promote health equity.

Introduction

Implicit bias shapes healthcare providers' behavior and can result in health disparities based on race, ethnicity, gender, and sexual orientation.1,2,3,4 These biases reflect prejudices and stereotypes that may be subtle and unintentional, and lead to well-recognized inequities in health and healthcare for patients who are Black, Indigenous, People of Color (BIPOC) and Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender and Gender Diverse (LGBTQ+).3,4,5 For example, Black patients are prescribed less pain medication,6 receive less aggressive heart attack treatments,4 receive fewer cardiovascular referrals,7 achieve poorer reproductive outcomes,8 experience less patient-centered communication, and rate care quality worse than White patients.9 Similarly, bias towards LGBTQ+ people can result in poor quality of care related to discrimination based on sexual orientation and/or gender identity,10 avoiding seeking care,11,12 lack of provider knowledge and training about LGBTQ+ health care needs,13 a preference among heterosexual providers towards heterosexual patients,14 and insufficient research about the health of LGBTQ+ populations.15 Implicit biases towards these historically marginalized groups negatively impact patient-provider interactions and produce unnecessary health inequities.

Although many have recognized and attempted to mitigate implicit bias,16 evidence suggests that this bias continues to influence clinical interactions.17 This ongoing problem exposes the need for a deeper understanding of how marginalized and underserved patients experience unfair treatment related to perceived bias and discrimination,18 which can help inform mitigating strategies in the future,19 including informatics solutions. As a first step in the design of automated technology to identify biases operating in patient provider interactions, this qualitative study investigated healthcare biases experienced by BIPOC and LGBTQ+ people and elicited their ideas for improving those experiences in future interactions with healthcare providers. We describe themes that emerged from our qualitative analysis of interviews with BIPOC and LGBTQ+ people, including their experiences of bias, their responses, the consequences, and their ideas for solutions. The research questions this study addresses are:

RQ1. How do BIPOC and LGBTQ+ patients experience biases in healthcare?

RQ2. What solutions do BIPOC and LGBTQ+ patients suggest for improving those experiences in the future?

Methods

Study Design

Data collection included an online survey and a semi-structured interview conducted remotely through Zoom. The University of Washington Institutional Review Board approved this study.

Participant Recruitment

Inclusion criteria for participant recruitment were: (1) to be BIPOC and/or LGBTQ+, (2) be 18 years of age or older, and (3) reside in the United States. The research team distributed recruitment flyers through institutional mailing lists, social media, and "community champions" who are patient representatives from BIPOC and LGBTQ+ communities who serve on our project's advisory board. Those who consented to participate completed the online survey and interview. Recruitment ended when the interviews reached thematic saturation.

Online survey

The online survey collected demographics information, including age, gender, race, ethnicity, education, and self-identification as BIPOC and/or LGBTQ+, and experiences of discrimination through the standardized 10-item Day-to-Day Unfair Treatment Scale.20 This widely used scale collects the frequency of experiencing situations considered to be unfair, such as being treated with less courtesy or respect than other people or being called names, harassed or followed around in stores. Response options were "Never", "Once", "2-3 times", and "4 or more times." For example, if the respondent answered something other than "Never" to the question "Have you been followed around in stores?", an additional question asked about the main reason for it with the following options: Ancestry, gender, race, age, religion, height or weight, shade or skin color, sexual orientation, education or income level, physical disability, or other. We did not recruit information about participants' socio-economic status or insurance coverage.

Interviews

Interviews occurred between June and November 2020 via Zoom and lasted one-hour. Except for one interview, two researchers interviewed each participant, one as the primary interviewer following the interview guide and the other one asking clarifying questions. During the first half of the interview, we asked participants to "Tell us about a time when you had an interaction with a doctor where you felt not heard, disrespected, or made uncomfortable?" (RQ1. Experiences). The second half of the interview asked them "If you had the power to change the experience you described, what would you change?" (RQ2. Strategies). After each interview, the researchers made notes summarizing the participants' experiences and solutions. Interviews were recorded and transcribed for qualitative analysis.

Data Analysis

Survey data was summarized with descriptive statistics, and qualitative data was summarized using thematic analysis.21 Thematic analysis involved developing and refining a codebook and transcript coding. Codebook development started with three researchers (RCP, CL & DV) inductively creating a preliminary codebook with the key themes identified from the initial transcript review. RCP incorporated relevant codes from existing literature16 and advice from co-authors. Next, two new coders (DM & EB) and an interviewer (CA) familiarized themselves with the data and refined the codebook. The analysis team was composed of four coders (RCP, DM, EB, CA). Two were female (DM & EB), one male (CA), and one non-binary (RCP). Two coders identify as Hispanic/Latino (CA & RCP), one as Asian American (DM) and one as White (EB). The analysis team read two transcripts weekly for codebook refinement and iterated until they reached a consensus. With the refined codebook, the researchers had two sessions of consensus coding where they coded individually two transcripts in Atlas.TI v.9 and manually reviewed the applied codes as a team. After making small adjustments to the codebook for addressing remaining discrepancies, the analysis team coded transcripts in pairs in Atlas.TI until completion.

Research Context

In early 2020, the WHO declared a pandemic due to the COVID-19 disease, which forced states and countries to go into lockdown, requiring this study work to take place remotely. COVID-19 brought to light long existing health disparities towards marginalized communities who were disproportionately exposed to the virus because of their 'essential' job category which prohibited them from staying home. Additionally, the Black Lives Matter (BLM) movement gained massive support after graphic videos depicting police brutality against Black people went viral on social media. Simultaneously, the American political environment and media was frequently filled with discriminatory comments. These three aspects may have influenced BIPOC or LGBTQ+ people to be more willing to share their negative experiences and how those experiences impacted their life. Collecting the data in these unprecedented circumstances presented a unique opportunity to understand patients' experiences of bias and discrimination during clinical interactions.

Results

Participants

Twenty-five participants completed the survey and the interview. Table 1 summarizes their characteristics. Participants ranged in age from 19-60 and were racially diverse. The majority were women, not Hispanic/Latino, and college educated. Eleven participants were BIPOC, ten reported were BIPOC & LGBTQ+, and three were LGBTQ+. One participant did not report to be BIPOC or LGBTQ+ but described themself as an "older Asian woman."

Table 1.

Participant Characteristics (n=25)

| Characteristics | n (%) |

| Age | |

| 19-29 | 15 (60%) |

| 30-50 | 9 (36%) |

| 50+ | 1 (4%) |

| Gender | |

| Woman | 16 (64%) |

| Man | 3 (12%) |

| Non-Binary | 3 (12%) |

| Gender Diverse | 3 (12%) |

| Race | |

| Black/African American | 5 (20%) |

| Chinese | 3 (12%) |

| Asian Indian | 4 (16%) |

| Native American/Alaskan Native | 1 (4%) |

| White | 3 (12%) |

| Multi-race | 6 (24%) |

| Other | 3 (12%) |

| Ethnicity | |

| Hispanic / Latino/a | 7 (28%) |

| Not Hispanic / Latino/a | 17 (68%) |

| Prefer not to disclose | 1 (4%) |

| Education | |

| Less than high school | 1 (4%) |

| High school | 1 (4%) |

| Some college, no degree | 4 (16%) |

| Bachelors degree | 12 (48%) |

| Graduate degree | 7 (28%) |

Experience of day-to-day unfair treatment

Table 2 summarizes participants' responses to the 10-item Day-to-Day Unfair Treatment Scale. Overall, participants reported experiencing substantial levels of unfair treatment. For example, all participants reported receiving poorer service than others and experiencing people acting as if they are superior. Eighty-seven percent of participants reported being treated with less respect and courtesy than others, 83% reported being called names or insulted, and 91% reported experiencing other people 'acting as if they think you are not smart'. Seventy-five percent of participants said they had been followed around in stores because of racial bias. Of those, 70% reported this was due to race, 10% due to sexual orientation or gender, and the remaining 20% chose other reasons such as height or weight, and shade of skin color.

Table 2.

Responses to the Day-to-Day Unfair Treatment Scale (n=24)

| In your day-to-day life, how often do any of the following things happen to you? | Never |

1 Time |

2 - 3 Times |

4+ Times |

| 1. You have been treated with less courtesy than other people are. | 12.50% | 12.50% | 33% | 42% |

| 2. You have been treated with less respect than other people are. | 12.50% | 8% | 42% | 37.50% |

| 3. You have received poorer service than other people at restaurants or stores. | 0% |

25% |

50% |

25% |

| 4. People have acted as if they think you are not smart. | 9% | 25% | 33% | 33% |

| 5. People have acted as if they are afraid of you. | 46% | 25% | 8% | 21% |

| 6. People have acted as if they think you are dishonest. | 33% | 21% | 29% | 17% |

| 7. People have acted as if theyre better than you are. | 0% | 17% | 29% | 54% |

| 8. You have been called names or insulted. | 17% | 21% | 29% | 33% |

| 9. You have been threatened or harassed. | 21% | 29% | 17% | 33% |

| 10. You have been followed around in stores | 25% | 21% | 25% | 29% |

Interview themes

Participants talked about their experiences of bias in the healthcare system, their reaction, and its consequences. They described experiences in different healthcare settings during the entire process for care-seeking, from scheduling the appointment to picking up their medications; explaining why their experiences involved different types of healthcare providers (Physicians, Nurses, Pharmacists). Although participants were not prompted, they organically mentioned healthcare system problems that made them feel not being taken care of and contrasted their negative experiences with positive ones. We identified two types of themes: (A) Experience and (B) Strategy. Experience themes refer to the biased healthcare experiences that contributed to feelings of not being taken care of. We identified and named eight Experience themes:

Transactional Care, Power Inequity, Communication Casualties, Bias-Embedded Medicine, System-level problems, Bigotry in Disguise, Fight or Flight, The Aftermath. We also report on interconnections among these themes. Strategy themes refer to insights for mitigating experiences of bias in healthcare. We identified two Strategy themes: Good Experiences and Solutions.

A. Experience with bias in healthcare

1. Transactional care

Transactional care refers to a provider treating an appointment as a job rather than an opportunity to look after the patient's well-being. This theme refers to the patients' experience of the appointment. Participants told us about incidents regarding providers rushing the appointment, not being thorough enough or only treating symptoms, refusing to take care of more than one medical concern in one appointment, and being uninformative with the patient about their medical reasoning, diagnoses, treatments, or alternatives. Participants expressed feeling unseen in transactions:

"I talked about being at the hospital and feeling I was just like, an assignment or some sort… of just one thing to do, like, 'okay, this is what you have to check the vitals, and this is where you need to give him this specific thing.' But not really being felt like I was really being seen." - PT18, BIPOC & LGBTQ+ Non-binary.

"That's what I always hear from my previous PCP is, 'Oh, we'll see if it gets better or take some over-the-counter medication for this' or, 'Oh, you know, just change your diet or exercise more.' But I didn't feel like he was really paying attention to, you know, what I actually was going through." - PT01, BIPOC & LGBTQ+ Man

2. Power Inequity

Power Inequity refers to the power imbalance between patients and providers that affected rapport building. This imbalance was often described as due to a knowledge difference between patients and providers. This imbalance made some participants feel that the provider judged them not to be smart enough to understand medical information, identify valid medical concerns, or make the best medical decisions. This judgment made some participants feel powerless and have no say in their own health or how they want to manage it. For example, one participant told us:

"I do think that it also comes with that power dynamic of like having more control as a doctor. As a professional you can say like 'I have all these degrees and have all these years of experience, and you're just a patient' … you don't have as much power in the situation, so they can kind of have control." - PT08, BIPOC & LGBTQ+ Woman.

Incidents for this theme involve providers making all the medical decisions without including the patient in the process, not building rapport with the patient, dismissing the patient without giving them an explanation, and making the patient feel that they do not have the qualifications for making medical decisions. For example, PT13 felt dismissed:

"I was asking the doctor what he thought would be like the cause of my symptoms. I suggested something, and he just kind of brushed it off. I feel like I wish he would have just explained why that wouldn't have been the case, rather than brushing it off. It kind of left me wondering why did he brush it off? was it a dumb reason or something?" - PT13, BIPOC Woman.

3. Communication Casualties

Communication Casualties refers to verbal or non-verbal cues that the patient identified as uncomfortable, awkward, or inappropriate. These negative cues made the patient feel unwelcomed, judged, or not taken care of. Participants described how some providers' comments negatively impacted their ability to receive care. Negative verbal cues refer to providers saying inappropriate comments to the patient, scolding them, or verbally judging their actions. Non-verbal cues refer to behaviors that made the patient feel that the physician was not paying attention to them, wanted the appointment to be over, or is did not understand their needs; these nonverbal cues included lack of eye contact, approaching the door when the patient was speaking, or having a judgmental tone of voice. For example, PT15 described negative cues expressed by a healthcare provider:

"I was seated, she was standing above me hands on her hips, literally lecturing me as if she was my mother. And flat out said 'if you were my son, this is what I would say to you'" - PT15, BIPOC & LGBTQ+ Man.

Several participants talked about the provider transmitting a 'vibe' that made them not trust the providers even if they could not explain the communication cue explicitly in words. PT14 describes the "vibe" of a negative interaction:

"I told (the provider) about my issue and (they) don't really offer any suggestions, and it was so tough. You can't explain vibes, right? There's no definition, it just felt awkward and weird" - PT14, BIPOC & LGBTQ+ Woman.

4. Bias-Embedded Medicine

Bias-Embedded Medicine refers to instances in which the patient felt they were treated unfairly because of their personal characteristics, such as race, ethnicity, gender identity, sexual orientation, or physical characteristics (e.g., weight). Because of these possible assumptions, patients had a hard time accessing tests, treatment, or obtaining a diagnosis. Incidents for this theme are misunderstanding of pain, BIPOC & LGBTQ+ stereotyping, and other types of stereotyping, such as weight or age. Misunderstanding of pain was when providers were thought to assume that the patient (BIPOC patients usually) was exaggerating their pain to get pain medication. For example, PT21 told us:

"I said, 'could you please do that [MRI] because I'm a movement performance artist. So, I would jeopardize my entire well-being, career, and financial status if I injured myself further. It's really, really important I treat myself for the exact condition'. He said, well, 'we are deeming it medically unnecessary because we do not feel it's necessary for you to have an MRI because we feel this information is good enough'" - PT21, BIPOC Woman.

BIPOC & LGBTQ+ stereotyping is when the provider adopts certain behaviors and characteristics after making assumptions related to the patient's demographic. Other types of stereotyping included assumptions based on reasons, like age or weight. For example, one participant described an experience of stereotyping:

"I saw written down 'high-risk homosexual behavior'. She asked me if I ever had sex with men. She didn't ask me the last time I had sex with men, and it couldn't have been because I hadn't had sex in like months, (…) I just dislike for her to make that assumption, that I was out there having unprotected sex" - PT23, BIPOC & LGBTQ+ Non-binary.

5. System-level problems

System-level problems refer to the patient feeling that the healthcare system is unwelcoming and difficult to navigate. Incidents in this theme related to the medical record, such as trouble accessing their records, or problems like confusing insurance systems, non-inclusive medical forms, and the lack of diversity in the medical workforce. For example, one participant described inaccurate medical records:

"After discharging me, (the physician) wrote in the chart notes that I had refused care. And I said, 'That's not true, this is what he told me, and I wasn't going to stay there for things to get worse'" - PT06, BIPOC & LGBTQ+ Woman.

Another participant describes the lack of diversity they perceive in the healthcare workforce:

"There's a real issue with supporting doctors who look like their patients. The only people of color are the ones cleaning, or in the cafeteria, I think diversity is such a huge part of it... I'm not saying that all doctors need to be people of color but, maybe seeing more people who just aren't in that standard mold that we've created healthcare to follow." - PT14, BIPOC & LGBTQ+ Woman.

6. Bigotry in Disguise

Bigotry in Disguise refers to when participants perceived providers to have implicit discriminatory attitudes or behaviors towards BIPOC and LGBTQ+ patients. Examples are the provider not knowing how to talk or take care of gender-diverse patients or appearing unaware of important needs for BIPOC patients, such as the prevalence of specific conditions among certain races/ethnicities. Participants understood that providers are not supposed to know everything but wanted providers to be honest about being unknowledgeable. For example, PT21 describes perceptions of a provider's disregard for her South Asian ancestry:

"I said 'there's a British study done on South Asians and cardiovascular disease and metabolic syndrome. There should be specifications as to what is healthy (for South Asians)'. He dismissed me and said 'all that matters is you do x, y, and z, which is not only for South Asians, just start, just do this'. And I said, 'okay, you don't know about the South Asian Studies'. And he said, 'I've never heard of any of this, and it doesn't matter'" - PT21, BIPOC Woman.

Another incident is when patients feel 'othered' by providers, meaning that the provider makes a rigid distinction between the provider's and the patient's community. These distinctions peaked when BIPOC participants saw providers treating White patients better than them (i.e., racial favoritism). These discriminatory attitudes were also experienced by LGBTQ+ participants. For example, PT25 describes a provider's bias toward their girlfriend:

"I said, "My partner has a penis. Does that affect this or that?" And he laughed and said, "Oh, well, I'm sure your boyfriend, yada, yada, yada." It made me so angry, because not only was he... I guess, for my body, I can justify it, and I can understand not everybody is super educated about trans issues or pronouns, whatever. I can excuse that even if it's not right, to help me get through the process and minimize my discomfort, but as soon as he disrespected my girlfriend, I got mad, and I just stopped talking, started giving very short, to-the-point answers, because I didn't wanna get angry and I wasn't going to explain everything in a hospital gown." - PT25, LGBTQ+ Multi-gender.

7. Fight or Flight

Fight or Flight refers to responses in which the patient realized they were being treated unfairly. There were two distinctly different types of responses: Active and Passive. The active response is when the patient self-advocates and demands to be treated with respect (i.e., fight). The passive response is when the patient says nothing and waits until the interaction is over (i.e., flight) for fear of repercussions. For example, PT21 described her "fight" response:

"I was so angry, and I told him 'I'm extremely upset with how you treated me, the difference in statistics for a South Asian person and a white person are very, very different. You're dismissing me. You're just dismissing me because I'm young and I'm brown, and you don't think my statistics are bad enough, and you've already told me that you think I'm fat, so I'm not going to see you again'" - PT21, BIPOC Woman.

Surprisingly, several participants, independent of whether they had an active or passive response, justified the providers' behavior for treating them unfairly. For example, PT04 told us:

"Okay, giving them the benefit of the doubt, they were probably just following protocol. That's where I think that maybe healthcare procedures need to account for looking more like situation alliance." - PT04, BIPOC Woman.

8. The Aftermath

The Aftermath refers to the consequences that biased experiences had in patients' lives. The most serious was the health-related consequences, where a patient's conditions got worse following a provider's dismissal. Other serious consequences were the patient self-medicating, delayed or avoided healthcare unless it was an emergency, or simply mistrusted the healthcare system altogether. For example, PT11 describes consequences of such. dismissal:

"I was overweight but active, I complained about knee pain all the time, and doctors always said 'lose weight.' Well, one time on vacation, I got injured and had to go get X-rays done on my knee. When the X-rays came back, the doctor was, like, "you have arthritis, and also your kneecap is misaligned." My first reaction was 'I'm not even 30, and I have arthritis?' and then it was anger because I have been dismissed for like a decade". - PT11, BIPOC & LGBTQ+.

Other consequences were changing providers searching for one who would treat them fairly, or start having "covering" behaviors, where the patient would change their physical presentation in the hope that providers will treat them better:

"This is another thing too that I have to do - I'll make sure that I'm suited that day. Like head to toe. Because even that sometimes can help the experience. Let me put on my professional attire. Sadly, it still doesn't work… I actually have to prepare myself in that way and be selective about what I choose to wear that day. Like I wouldn't want to go in like my leggings." - PT16, BIPOC Woman. Quote about covering behaviors

Interconnections among themes related to participants' experiences with bias in healthcare

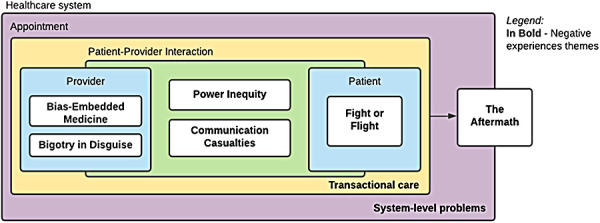

Identified themes are intrinsically connected. Figure 1 is a visual representation of interconnection among themes within three nested dimensions: the healthcare system (purple rectangle), the appointment (yellow rectangle), and the patient-provider interaction (green). The eight Experience themes are in bold. The first dimension, the healthcare system, includes the 'System-level problems' since participants mentioned structural problems as a challenge when visiting the provider. In the appointment dimension, we found 'Transactional Care' since it refers to problems during appointments. In the appointment dimension, we found two entities (in blue), the provider and the patient, connected within the patient-provider interaction dimension. The provider can bring the 'Bias-Embedded Medicine' and 'Bigotry in Disguise' into the interaction which the patient can perceive as 'Power Inequity' and 'Communication Casualties,' leaving the decision of "Fight or Flight" to the patient. After the appointment, 'The Aftermath' could result in the patient choosing to leave the healthcare system altogether, so it sits halfway outside the healthcare system dimension.

Figure 1.

Interconnections among themes related to participants' experiences of bias in healthcare

B. Strategies to mitigate the experience of bias in healthcare

The second half of the interview focused on the participants' suggested solutions about how to prevent these biased healthcare experiences from repeating. Many participants organically contrasted their negative experiences with good experiences. We report both participant-generated solutions along with those good experiences since they can display well-received providers' actions and could help guide mitigating strategies.

1. Solutions

Solutions refer to the participants' ideas about what could help prevent the biased interactions from repeating. Participants' ideas include having patient advocates accompany them to feel more comfortable at the providers' office, provide feedback to the provider to let them know what went wrong during the interaction, enhance provider training on interpersonal skills and cultural competence towards BIPOC and LGBTQ+ patients, and promote diversity in the healthcare workforce. For example, PT16 describes providing feedback:

"The goal, hopefully, from the doctor's perspective, would be to have this honest feedback that they could grow from and implement changes for. It's tough, but you know it's a necessity." - PT16, BIPOC Woman.

Participants mostly referred to non-technological solutions, but some mentioned the use of technology to address the solutions. For example, PT02 proposed using technology for patient advocacy:

"I think it would be useful in the doctor's office if there was a robot that could be like 'wait, doctor, let the patient talk' because I feel like doctors are always in a rush" - PT02, BIPOC Woman.

2. Good experiences with healthcare

When talking about negative experiences with providers, most participants organically compared those experiences with good experiences they had with other providers. For BIPOC patients, good experiences were the ones when the provider did not doubt their symptoms. For LGBTQ+ patients, good experiences happened when the provider validated their identity and did not make assumptions about them or their partner. For both groups, good experiences were when the provider treated them with respect, carefully listened, took their needs into consideration, gave a thorough explanation of the diagnosis and treatment, genuinely worked in rapport building, and were noticeably interested in reducing the power differences (e.g., sitting at the patients' eye level, looked them in the eyes). For example, PT22 describe feeling respected by the provider:

"I think it was that my first doctor, he respected that I wouldn't have been there if I hadn't done a ton of research, and he also respected the fact that I had been working in the medical field for 11 years. That I wasn't just an internet researcher. So, he wasn't wasting time trying to dumb things down, and he explained what needed to happen and why it needed to happen" - PT22, LGBTQ Transgender Woman

PT16 describes feeling a warm welcome from a provider:

"He spent time with us, like he wanted to know what I was doing for my well-being, and I talked to him about my arthritis and using CBD, and I went there for my lungs (laugh). And that was a cool experience. And my daughter had just turned 18, so we were in separate rooms, and he was 'if you guys are cool with it, we can sit together.' It was really warm, and this is a walk-in clinic." - PT16, BIPOC Woman

Discussion

As a critical first step to inform design of automated technology to identify how biases operate in patient provider clinical interactions, we interviewed 25 BIPOC and/or LGBTQ+ participants about biased healthcare experiences. We found eight themes related to the experiences and two themes about the strategies to mitigate bias in the future. Experience themes were Transactional Care, Power Inequity, Communication Casualties, Bias-Embedded Medicine, System-level problems, Bigotry in Disguise, Fight or Flight, and The Aftermath. We presented a visual representation on the interconnections among the eight experience themes. Strategy themes were Solutions and Good Experiences. The ten themes presented in this study contribute to the understanding of biased healthcare experiences from the perspective of BIPOC and LGBTQ+ patients. Although prior research examines impacts of implicit bias on healthcare (1)(3)(4) we are contributing to filling the gap that exists surrounding how to apply the perspectives of BIPOC and LGBTQ+ patients on biased healthcare experiences and gathers their ideas for designing informatics solutions. Health informatics researchers and practitioners can leverage our findings to inform the development of technological innovations that improve the quality of patient-provider interaction by addressing implicit bias.

The experiences we heard from both groups support prior work related to not being heard22 and being dismissed by providers.23 BIPOC participants experiences related to racial discrimination in healthcare,24 measurements of perceived racial/ethnic discrimination,25 its impact on health and well-being,26 pain misinterpretation,27 physical and mental health outcomes,27,28 the perpetuation of health inequities,29 and its impact to patient-provider communication.30 Experiences from LGBTQ+ participants are consistent with literature reporting poor quality of care due to discrimination based on sexual orientation or gender identity,10 lack of provider knowledge about LGBTQ+ health care needs,13 and a preference towards heterosexual patients.14 We corroborated that institutional racism and homo-/transphobia remain problems in healthcare.31,32,33 Themes related to the patients' response and consequences from a biased interaction, support prior work about medical mistrust originating from perceived discrimination experiences.34 This understanding of the "Fight or Flight" and "The Aftermath" themes can inform a better healthcare service design for improving patients' experiences in the healthcare system. These themes and their interconnection allowed us to understand how BIPOC and LGBTQ+ patients experience biases in healthcare, our RQ1.

The "Good Experiences" that participants shared demonstrated that some healthcare providers may have noted these problems and contributed to enhancing the experiences of patients from marginalized groups. Simple non-technical solutions might go a long way to help patients feel validated and cared for, such as a questionnaire for the patient to fill out their sexual orientation and gender identity. Thus, health informatics researchers and practitioners can leverage simple and familiar technologies (e.g., electronic questionnaires) to improve patient-provider interactions. Solutions that aim to enhance providers' training reflect the need for medical education curriculum with a strong, fully integrated, culturally competent component35 and content on the medical needs of the BIPOC and LGBTQ+ community.36,37,38 Diversifying the healthcare workforce is another priority in the quest for more equitable care and strategic use of technology in healthcare to achieve health equity (i.e.,"TechQuity").39 The themes we identified allow us to understand how BIPOC and LGBTQ+ patients want to improve healthcare experiences, which provides critical guidance for all of these potential solutions.

This study has a number of limitations and strengths. One significant limitation is sampling bias. Due to COVID-19 restrictions, we were only able to recruit through virtual means which skewed our sample to be younger and college educated, and potentially socioeconomically advantaged. Our sample was likely limited due to the technological requirements for participating in the interview (e.g., device compatible with Zoom software with a microphone, stable internet connection), which could have prevented people with non-technological backgrounds from participating. Another limitation is recall bias, which could have impacted the experiences the participants reported. Our use of recently minted terminology such as "BIPOC" could also have had an impact on the age of participants because this term may have been more familiar to younger people. Finally, we only interviewed three participants who were LGBTQ+-only, which limits the transferability of findings for this population. However, we captured perspectives from ten participants who were both BIPOC and LGBTQ+, which offered important insights on intersectional experiences.

We demonstrate that there is an opportunity for the biomedical informatics community to establish a more collaborative environment between patients and informaticians for solutions on how to improve the patient-provider interaction, provide better patient-centered care, and incorporate marginalized patients' needs. Patients' perspectives about biased healthcare experiences have laid the groundwork for using these patient reported themes in a range of future work to promote TechQuity. In particular, we are using findings to inform co-design work with patients and providers inform automated assessment tools40,41 that raise awareness of hidden bias in patient-provider communication. Future work should also examine experiences of intersectional individuals in greater depth and how this intersectionality can be represented and incorporated into technological solutions.

Conclusion

We interviewed 25 BIPOC and/or LGBTQ+ participants who described biased healthcare experiences when visiting a healthcare provider. Through qualitative thematic analysis, we describe ten themes that describe their experiences and suggested solutions to mitigate those experiences in the future. Characterizing these themes and their interconnections lays a foundation for understanding lived experiences of patients from marginalized groups that can critically guide the design of informatics solutions to mitigate those biases, improve the quality of patient-provider interactions, and ultimately promote health equity.

Acknowledgements

The study is supported by #1R01LM013301. We want to acknowledge our participants for sharing their experiences, community champions who helped us recruit, and our advisory board members who helped frame the study.

Figures & Table

References

- 1.Maina IW, Belton TD, Ginzberg S, Singh A, Johnson TJ. A decade of studying implicit racial/ethnic bias in healthcare providers using the implicit association test. Soc Sci Med. 2018 Feb 1;199:219–29. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2017.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shavers VL, Klein WMP, Fagan P. Research on Race/Ethnicity and Health Care Discrimination: Where We Are and Where We Need to Go. Am J Public Health. 2012 Apr 11;102(5):930–2. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.300708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hall WJ, Chapman MV, Lee KM, Merino YM, Thomas TW, Payne BK, et al. Implicit Racial/Ethnic Bias Among Health Care Professionals and Its Influence on Health Care Outcomes: A Systematic Review. Am J Public Health. 2015 Oct 15;105(12):e60–76. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2015.302903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Green AR, Carney DR, Pallin DJ, Ngo LH, Raymond KL, Iezzoni LI, et al. Implicit Bias among Physicians and its Prediction of Thrombolysis Decisions for Black and White Patients. J Gen Intern Med. 2007 Sep 1;22(9):1231–8. doi: 10.1007/s11606-007-0258-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.FitzGerald C, Hurst S. Implicit bias in healthcare professionals: a systematic review. BMC Med Ethics. 2017 Mar 1;18(1):19. doi: 10.1186/s12910-017-0179-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tamayo-Sarver JH, Hinze SW, Cydulka RK, Baker DW. Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Emergency Department Analgesic Prescription. Am J Public Health. 2003 Dec 1;93(12):2067–73. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.12.2067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schulman KA, Berlin JA, Harless W, Kerner JF, Sistrunk S, Gersh BJ, et al. The Effect of Race and Sex on Physicians’ Recommendations for Cardiac Catheterization. N Engl J Med. 1999 Feb 25;340(8):618–26. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199902253400806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Eichelberger KY, Doll K, Ekpo GE, Zerden ML. Black Lives Matter: Claiming a Space for Evidence-Based Outrage in Obstetrics and Gynecology. Am J Public Health. 2016 Sep 14;106(10):1771–2. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2016.303313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cooper LA, Roter DL, Carson KA, Beach MC, Sabin JA, Greenwald AG, et al. The Associations of Clinicians’ Implicit Attitudes About Race With Medical Visit Communication and Patient Ratings of Interpersonal Care. Am J Public Health. 2012 Mar 15;102(5):979–87. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Conron KJ, Mimiaga MJ, Landers SJ. A population-based study of sexual orientation identity and gender differences in adult health. Am J Public Health. 2010 Oct;100(10):1953–60. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.174169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tracy JK, Lydecker AD, Ireland L. Barriers to Cervical Cancer Screening Among Lesbians. J Womens Health. 2010 Feb;19(2):229–37. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2009.1393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Simpson TL, Balsam KF, Cochran BN, Lehavot K, Gold SD. Veterans administration health care utilization among sexual minority veterans. Psychol Serv. 2013 May;10(2):223–32. doi: 10.1037/a0031281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gates G. In U.S., LGBT More Likely Than Non-LGBT to Be Uninsured [Internet] Gallup.com . 2014 [cited 2020 Jun 21]. Available from: https://news.gallup.com/poll/175445/lgbt-likely-non-lgbt-uninsured.aspx . [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sabin JA, Riskind RG, Nosek BA. Health Care Providers’ Implicit and Explicit Attitudes Toward Lesbian Women and Gay Men. Am J Public Health. 2015 Jul 16;105(9):1831–41. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2015.302631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Health Issues and Research Gaps and Opportunities . The Health of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender People: Building a Foundation for Better Understanding [Internet] Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 2011. [cited 2021 Mar 1]. (The National Academies Collection: Reports funded by National Institutes of Health). Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK64806/ [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Marcelin JR, Siraj DS, Victor R, Kotadia S, Maldonado YA. The Impact of Unconscious Bias in Healthcare: How to Recognize and Mitigate It. J Infect Dis. 2019 Aug 20;220(Supplement_2):S62–73. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiz214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lewis D, Paulson E. Proceedings of the Diversity and Inclusion Innovation Forum: Unconscious Bias in Academic Medicine. Fac Bookshelf [Internet] 2017 Feb 1; Available from: https://hsrc.himmelfarb.gwu.edu/books/132 . [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hausmann LRM, Jones AL, McInnes SE, Zickmund SL. Identifying healthcare experiences associated with perceptions of racial/ethnic discrimination among veterans with pain: A cross-sectional mixed methods survey. PLOS ONE. 2020 Sep 3;15(9):e0237650. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0237650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Turan JM, Elafros MA, Logie CH, Banik S, Turan B, Crockett KB, et al. Challenges and opportunities in examining and addressing intersectional stigma and health. BMC Med. 2019 Feb 15;17(1):7. doi: 10.1186/s12916-018-1246-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Krieger N, Smith K, Naishadham D, Hartman C, Barbeau EM. Experiences of discrimination: Validity and reliability of a self-report measure for population health research on racism and health. Soc Sci Med. 2005 Oct 1;61(7):1576–96. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006 Jan 1;3(2):77–101. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gordon HS, Solanki P, Bokhour BG, Gopal RK. “I’m Not Feeling Like I’m Part of the Conversation” Patients’ Perspectives on Communicating in Clinical Video Telehealth Visits. J Gen Intern Med. 2020 Jun 1;35(6):1751–8. doi: 10.1007/s11606-020-05673-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Upshur CC, Bacigalupe G, Luckmann R. “They Don’t Want Anything to Do with You”: Patient Views of Primary Care Management of Chronic Pain. Pain Med. 2010 Dec 1;11(12):1791–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4637.2010.00960.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Baptiste D-L, Josiah NA, Alexander KA, Commodore-Mensah Y, Wilson PR, Jacques K, et al. Racial discrimination in health care: An “us” problem. J Clin Nurs. 2020;29(23–24):4415–7. doi: 10.1111/jocn.15449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hausmann L, Kressin N, Hanusa B, Ibrahim S. Perceived Racial Discrimination in Health Care and its Association with Patients’ Healthcare Experiences: Does the Measure Matter? Ethn Dis. 2010 Dec 1;20:40–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Priest N, Paradies Y, Trenerry B, Truong M, Karlsen S, Kelly Y. A systematic review of studies examining the relationship between reported racism and health and wellbeing for children and young people. Soc Sci Med. 2013 Oct 1;95:115–27. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2012.11.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Paradies Y, Ben J, Denson N, Elias A, Priest N, Pieterse A, et al. Racism as a Determinant of Health: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. PLOS ONE. 2015 Sep 23;10(9):e0138511. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0138511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Smedley BD. The Lived Experience of Race and Its Health Consequences. Am J Public Health. 2012 Mar 15;102(5):933–5. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Krieger N. Discrimination and Health Inequities. Int J Health Serv. 2014 Oct 1;44(4):643–710. doi: 10.2190/HS.44.4.b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hausmann LRM, Hannon MJ, Kresevic DM, Hanusa BH, Kwoh CK, Ibrahim SA. Impact of perceived discrimination in health care on patient-provider communication. Med Care. 2011 Jul;49(7):626–33. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e318215d93c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Randall VR. What is Institutional Racism? [Internet] [cited 2021 Mar 1]. Available from: https://academic.udayton.edu/race/2008electionandracism/raceandracism/racism02.htm . [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chapman R, Wardrop J, Freeman P, Zappia T, Watkins R, Shields L. A descriptive study of the experiences of lesbian, gay and transgender parents accessing health services for their children. J Clin Nurs. 2012 Apr;21(7–8):1128–35. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2011.03939.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Durso LE, Meyer IH. Patterns and Predictors of Disclosure of Sexual Orientation to Healthcare Providers among Lesbians, Gay Men, and Bisexuals. Sex Res Soc Policy J NSRC SR SP. 2013 Mar 1;10(1):35–42. doi: 10.1007/s13178-012-0105-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Benkert R, Cuevas A, Thompson HS, Dove-Meadows E, Knuckles D. Ubiquitous Yet Unclear: A Systematic Review of Medical Mistrust. Behav Med. 2019 Apr 3;45(2):86–101. doi: 10.1080/08964289.2019.1588220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kripalani S, Bussey-Jones J, Katz MG, Genao I. A prescription for cultural competence in medical education. J Gen Intern Med. 2006 Oct 1;21(10):1116–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00557.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Streed CG, Davis JA. Improving Clinical Education and Training on Sexual and Gender Minority Health. Curr Sex Health Rep. 2018 Dec 1;10(4):273–80. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Morris M, Cooper RL, Ramesh A, Tabatabai M, Arcury TA, Shinn M, et al. Training to reduce LGBTQ-related bias among medical, nursing, and dental students and providers: a systematic review. BMC Med Educ. 2019 Aug 30;19(1):325. doi: 10.1186/s12909-019-1727-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ding JM, Ehrenfeld JM, Edmiston EK, Eckstrand K, Beach LB. A Model for Improving Health Care Quality for Transgender and Gender Nonconforming Patients. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2020 Jan 1;46(1):37–43. doi: 10.1016/j.jcjq.2019.09.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rhee K. What is TechQuity? J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2021:xiii–xviii. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hartzler AL, Patel RA, Czerwinski M, Pratt W, Roseway A, Chandrasekaran N, et al. Real-time feedback on nonverbal clinical communication. Theoretical framework and clinician acceptance of ambient visual design. Methods Inf Med. 2014;53(5):389–405. doi: 10.3414/ME13-02-0033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Weibel N, Rick S, Emmenegger C, Ashfaq S, Calvitti A, Agha Z. LAB-IN-A-BOX: Semi-automatic Tracking of Activity in the Medical Office. Pers Ubiquitous Comput. 2015 Feb;19(2):317–34. [Google Scholar]