Abstract

Objective

To report long-term safety from the completed extension trial of baricitinib, an oral selective Janus kinase inhibitor, in patients with active rheumatoid arthritis (RA).

Methods

Treatment-emergent adverse events are summarised from an integrated database (9 phase III/II/Ib and 1 long-term extension) of patients who received any baricitinib dose (All-bari-RA). Standardised incidence ratio (SIR) for malignancy (excluding non-melanoma skin cancer (NMSC)) and standardised mortality ratio (SMR) were estimated. Additional analysis was done in a subset of patients who had ever taken 2 mg or 4 mg baricitinib.

Results

3770 patients received baricitinib (14 744 patient-years of exposure (PYE)). All-bari-RA incidence rates (IRs) per 100 patient-years at risk were 2.6, 3.0 and 0.5 for serious infections, herpes zoster and major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE), respectively. In patients aged ≥50 with ≥1 cardiovascular risk factor, the IR for MACE was 0.77 (95% CI 0.56 to 1.04). The IR for malignancy (excluding NMSC) during the first 48 weeks was 0.6 and remained stable thereafter (IR 1.0). The SIR for malignancies excluding NMSC was 1.07 (95% CI 0.90 to 1.26) and the SMR was 0.74 (95% CI 0.59 to 0.92). All-bari-RA IRs for deep vein thrombosis (DVT)/pulmonary embolism (PE), DVT and PE were 0.5 (95% CI 0.38 to 0.61), 0.4 (95% CI 0.26 to 0.45) and 0.3 (95% CI 0.18 to 0.35), respectively. No clear dose differences were noted for exposure-adjusted IRs (per 100 PYE) for deaths, serious infections, DVT/PE and MACE.

Conclusions

In this integrated analysis including long-term data of baricitinib from 3770 patients (median 4.6 years, up to 9.3 years) with active RA, baricitinib maintained a similar safety profile to earlier analyses. No new safety signals were identified.

Trial registration number

NCT01185353, NCT00902486, NCT01469013, NCT01710358, NCT02265705, NCT01721044, NCT01721057, NCT01711359 and NCT01885078.

Keywords: rheumatoid arthritis, autoimmune diseases, biological therapy

Key messages.

What is already known about this subject?

The efficacy and safety of baricitinib, an oral, reversible and selective Janus kinase (JAK)1/JAK2 inhibitor in rheumatoid arthritis (RA), have been reported from previous phase II and III randomised controlled trials and open-label, long-term extension studies.

The efficacy of baricitinib has been demonstrated in populations that cover the clinical disease continuum.

Previous integrated analyses of the long-term safety of baricitinib in patients with RA included placebo-controlled and dose–response assessments.

Adverse events were stable over time and no new safety risks were observed.

The safety profile of JAK inhibitors in clinical trials includes an increased risk of herpes zoster and associations with increased cardiovascular events, venous thromboembolic events (VTE) and malignancies.

As disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs, JAK inhibiotors are used chronically in patients with RA, and it is important to continuously monitor and assess the evolving long-term safety profile.

Key messages.

What does this study add?

This final report of the long-term safety of baricitinib describes the highest level of patient exposure use of up to 9 years and over 14 000 patient-years of exposure, across the spectrum of the RA population, from integrated data of randomised clinical trials and the completed long-term extension study.

The safety profile of baricitinib remained consistent with previous reports.

Rates of safety events of special interest, including deaths, malignancies, major adverse cardiovascular event (MACE) and deep vein thrombosis/pulmonary embolism, remained stable through exposures up to 9.3 years and were generally similar between the 2 mg and 4 mg groups.

The potential risk of MACE, VTE and malignancy events with JAK inhibitors warrants further characterisation, including registries.

How might this impact on clinical practice or future developments?

This study is the largest integrated safety analysis of baricitinib.

The results suggest that baricitinib has a consistent safety profile as demonstrated in previous reports and is in line with other JAK inhibitors and biologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs.

Because RA is a chronic inflammatory disease that requires long-term treatment, this study gives assurances that baricitinib can be used for prolonged periods of time.

Continued follow-up and further research, including long-term population-based studies, are needed to fully understand the risk of outcomes, including malignancies, MACE and VTE, and the comparative real-world risk of baricitinib and therapies in RA.

Introduction

Baricitinib, an oral, reversible and selective Janus kinase (JAK)1/JAK2 inhibitor,1 is indicated for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis (RA). In clinical trials, once-daily baricitinib at 2 mg and 4 mg doses have shown significant clinical efficacy with acceptable safety.2–5 The most commonly reported serious adverse events (SAEs) during the placebo-controlled period were infections.2–5 Integrated long-term safety of baricitinib in 3770 patients (10 127 patient-years of exposure (PYE)) during the RA clinical development programme has been previously reported.6 7 As baricitinib, like other disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs), is used chronically in patients with RA, it is important to continuously monitor and assess the evolving long-term safety profile. These long-term data are most relevant to assess the incidence and risk of uncommon adverse events of special interest (AESI), including malignancies and major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE). Since the previous analysis, the long-term extension (LTE) study has concluded, and we present the final update of integrated data of up to 9.3 years of treatment, representing an additional 4617 PYE.6

Materials and methods

Study design and patients

Pooled data of patients ≥18 years old with moderate-to-severe active RA from nine randomised clinical trials (five phase III, three phase II, one phase Ib) and one completed LTE trial (online supplemental table 1) were analysed.2–5 8–10 Exclusion criteria included current or recent (<30 days prior to study entry) clinically serious infection requiring antimicrobial treatment and selected laboratory abnormalities (eg, hepatic/renal function tests, selected haematology and markers of infection). Baricitinib doses ranged from 1 mg to 15 mg daily, with 2 mg and 4 mg daily doses in the phase III and LTE trials. All patients provided written informed consent.

annrheumdis-2021-221276supp001.pdf (266.1KB, pdf)

Patients completing phase III trials and phase II trial (NCT01185353) were eligible for the LTE. Patients randomised to baricitinib 2 mg and not rescued in the originating study continued on baricitinib 2 mg in the LTE; all other patients received baricitinib 4 mg at LTE entry. Patients receiving 4 mg for at least 15 months without rescue and achieving sustained low disease activity (Clinical Disease Activity Index (CDAI) score ≤10) or remission (CDAI score ≤2.8)11 were blindly rerandomised to 4 mg or tapered down to 2 mg.

Patient and public involvement

This research was done without patient and public involvement.

Analysis sets

The All-bari-RA analysis set includes data of all patients who received ≥1 dose of baricitinib using all available data after the first dose without censoring for rescue or dose change. This analysis set is uncontrolled and provides reliable estimates for adverse event incidence within the baricitinib programme, which is particularly relevant for less common event types and for evaluating the incidence after long-term exposure. An exploratory analysis of AESI and death was done in a subset of data from All-bari-RA that included patients who had ever taken baricitinib at 2 mg or 4 mg. As a postmarketing study found an increased risk of MACE and malignancies excluding non-melanoma skin cancer (NMSC) with tofacitinib versus tumour necrosis factor inhibitors (TNFi) in patients ≥50 years with cardiovascular risk factors, the incidence rate (IR) of MACE was analysed in a similar subpopulation.

Safety evaluations included treatment-emergent adverse events (TEAEs), adverse events leading to temporary interruption or permanent discontinuation of study drug, SAEs, deaths, and AESI, including serious and opportunistic infections, malignancies, MACE, deep vein thrombosis (DVT)/pulmonary embolism (PE), and gastrointestinal perforations. SAEs were any event meeting the International Conference on Harmonisation E2A seriousness criteria.12 Cardiovascular adverse events from the five phase III studies and LTE, identified by investigators or according to a predefined list of event terms, were adjudicated for MACE by an independent, external Clinical Endpoint Committee that remained blinded to treatment assignments. Venous thromboembolic events were not externally adjudicated in the baricitinib RA programme. Gastrointestinal perforations were based on events identified from a medical review of the gastrointestinal perforations Standardised Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities Queries and were considered definite or probable perforations after internal medical review.

Statistical analysis

Baseline characteristics were descriptively analysed. For adverse events (except AESI), the exposure-adjusted incidence rate (EAIR) was calculated as the number of patients with an event per 100 PYE, including observation time during the follow-up period. For AESI, the IR was calculated as the number of patients with an event per 100 patient-years at risk (PYR), including follow-up time censored at event onset date. Poisson distribution was used to calculate 95% CI. The EAIR for death, serious infections, MACE and DVT/PE was calculated for groups of patients receiving baricitinib 2 mg or 4 mg within All-bari-RA, with the EAIR based on the dose at the time of the event, given that patients in this subset could contribute events to both treatment groups depending on their drug dose at the time of the event. The IR for MACE was evaluated in subgroups of patients aged ≥50 years and presenting with cardiovascular risk factors (current smoker, hypertension, high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol <40 mg/dL, diabetes or arteriosclerotic cardiovascular disease). This IR was calculated as 100 times the number of patients experiencing MACE divided by PYR (exposure time up to the event for patients with MACE and exposure time up to the end of the period for patients without MACE) in years in the subgroup of the specific factor. To account for ageing of the cohort, standardised incidence ratio (SIR) was calculated as the ratio of observed to expected number of malignancies (excluding NMSC) using age-specific malignancy data from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results 17 (SEER17), 2013–2017 US population cancer rates.13 Standardised mortality ratio (SMR) was estimated using 2019 population mortality calculated as compared with the general US population with the same age and sex distribution.14

Results

Patients

Patient demographics and disease activity are presented in online supplemental table 2. In this final analysis of All-bari-RA, 3770 patients received ≥1 dose of baricitinib for a total of 14 744 PYE, an additional 4617 PYE from our previous report.6 The majority of PYE (80.5%) were baricitinib 4 mg, while 18.1% of PYE were baricitinib 2 mg; 78.5% of patients had ≥1 year and 47.1% had ≥5 years of baricitinib treatment. The median exposure was 4.6 years and the maximum exposure was 9.3 years (table 1).

Table 1.

Safety summary among patients with RA treated with at least one dose of baricitinib (All-bari-RA analysis set)

| All-bari-RA (N=3770) |

|

| Exposure | |

| Total patient-years of exposure to baricitinib | 14 744.4 |

| Total patient-years (including follow-up period) | 15 114.1 |

| Number of patients with ≥52 weeks, n (%) | 2961 (78.5) |

| Number of patients with ≥104 weeks, n (%) | 2519 (66.8) |

| Number of patients with ≥208 weeks, n (%) | 2093 (55.5) |

| Number of patients with ≥260 weeks, n (%) | 1775 (47.1) |

| Median duration, days | 1682.5 |

| Longest exposure, days | 3405 |

| ≥1 AE, n (EAIR) | |

| Any TEAE | 3421 (22.6) |

| SAE | 1117 (7.4) |

| Temporary study drug interruption due to AE | 1282 (8.5)* |

| Permanent discontinuation of the study drug due to AE | 704 (4.7) |

| Death, n (IR) | 85 (0.56) |

| Infections, n (IR) | |

| Treatment-emergent infections† | 2590 (17.1) |

| Serious infection | 372 (2.6) |

| Herpes zoster | 422 (3.0) |

| Infection leading to death† | 19 (0.1) |

| TB† | 19 (0.1) |

| Opportunistic infection excluding TB | 69 (0.5) |

| Malignancy, n (IR) | |

| Malignancy excluding NMSC | 139 (0.9) |

| Lymphoma | 9 (0.06) |

| NMSC | 50 (0.3) |

| Adverse CV events of special interest, n (IR) | |

| MACE‡ | 73 (0.5) |

| MI | 24 (0.2) |

| CV death | 20 (0.1) |

| Stroke | 38 (0.3) |

| DVT/PE | 73 (0.5) |

| DVT§ | 52 (0.4) |

| PE | 39 (0.3) |

| GI disorder, n (IR) | |

| GI perforations | 9 (0.06) |

*Some studies did not collect temporary interruption of study drug.

†Used EAIR per 100 PY (patient exposure not censored at the event).

‡Potential CV adverse events from the phase III and LTE trials, identified by investigators or according to a predefined list of event terms, were adjudicated by an independent, external Clinical Endpoint Committee that remained blinded to treatment assignments.

§DVT includes distal events below the knee.

AE, adverse events; bari, baricitinib; CV, cardiovascular; DVT, deep vein thrombosis; EAIR, exposure-adjusted incidence rate; GI, gastrointestinal; IR, incidence rate; LTE, long-term extension; MACE, major adverse cardiovascular events; MI, myocardial infarction; N, number of patients in the analysis set; n, number of patients in the specified category; NMSC, non-melanoma skin cancer; PE, pulmonary embolism; PY, patient-years; RA, rheumatoid arthritis; SAE, serious adverse event; TB, tuberculosis; TEAE, treatment-emergent adverse event.

Adverse events including SAEs

In All-bari-RA, the EAIRs (per 100 PYE) for any TEAE and SAE were 22.6 and 7.4, respectively. The most common TEAEs were nasopharyngitis, upper respiratory tract infections, bronchitis, urinary tract infections and herpes zoster (online supplemental table 3). Interruptions and discontinuations were most frequently due to infections. There were 85 deaths, and the IR (patient-years=15 114, IR=0.56, 95% CI 0.45 to 0.70) increased over time. After controlling for age and sex, the baricitinib SMR was <1 (SMR 0.74, 95% CI 0.59 to 0.92; online supplemental figure 1). Of the 85 deaths, categories (system organ class based on Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities Terminology V.23.1) for causes that included >2 deaths were cardiovascular-related (n=19, 22.4%), infections (n=19, 22.4%), neoplasms (n=19, 22.4%), respiratory-related (n=13, 15.3%, including 4 due to PE, 2 of which included comorbid cancer and 1 who had comorbid diverticulitis with sepsis), general disorders (n=6, 7.1%), nervous system-related (n=5, 5.9%) and vascular disorders (n=3, 3.5%). The EAIRs for death were similar in the 2 mg and 4 mg subsets of All-bari-RA (table 2).

Table 2.

Exposure-adjusted incidence rates of adverse events of special interest in the 2 mg and 4 mg subsets of the All-bari-RA analysis set

| Ever on 2 mg (N=1077) (PYE=2678) EAIR (95% CI) |

Ever on 4 mg (N=3401) (PYE=11 872) EAIR (95% CI) |

All-bari-RA (N=3770) (PYE=14 744) IR (95% CI) |

|

| Death | 0.56 (0.31 to 0.92) | 0.57 (0.44 to 0.73) | 0.56 (0.45 to 0.70) |

| Serious infections | 2.13 (1.61 to 2.76) | 2.62 (2.34 to 2.93) | 2.58 (2.33 to 2.86) |

| Thromboembolic events | |||

| DVT/PE | 0.49 (0.26 to 0.83) | 0.51 (0.39 to 0.66) | 0.49 (0.38 to 0.61) |

| DVT | 0.41 (0.21 to 0.73) | 0.35 (0.25 to 0.48) | 0.35 (0.26 to 0.45) |

| PE | 0.26 (0.11 to 0.54) | 0.27 (0.18 to 0.38) | 0.26 (0.18 to 0.35) |

| MACE* | 0.42 (0.21 to 0.74) | 0.54 (0.41 to 0.69) | 0.51 (0.40 to 0.64) |

*Positively adjudicated events of myocardial infarction, stroke and cardiovascular deaths.

bari, baricitinib; DVT, deep vein thrombosis; EAIR, exposure-adjusted incidence rate; IR, incidence rate; MACE, major adverse cardiovascular events; N, number of patients in the analysis set; PE, pulmonary embolism; PYE, patient-years of exposure; RA, rheumatoid arthritis.

Adverse events of special interest

Infections

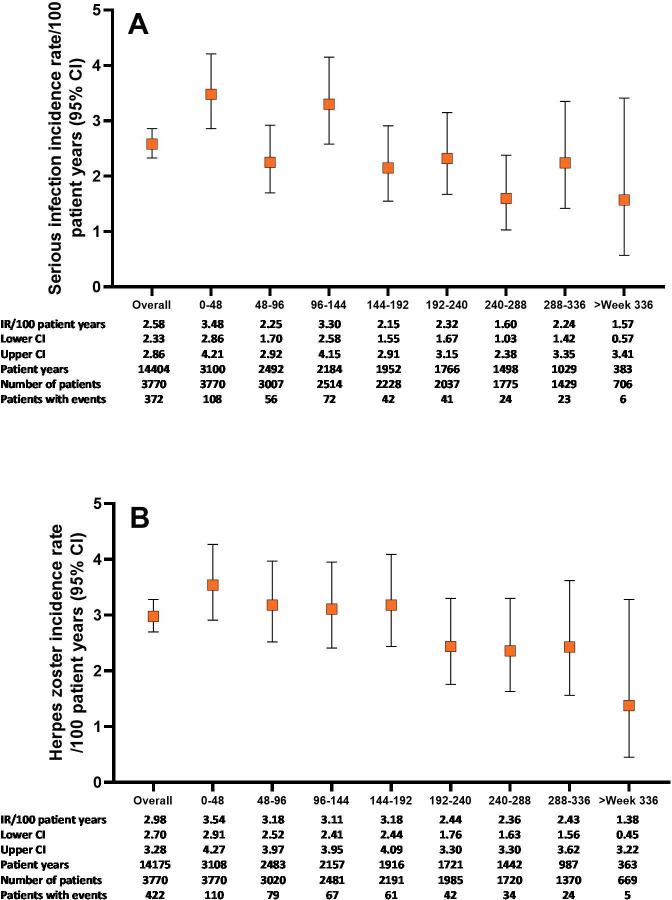

Infections were the most common TEAE. The IR for serious infections (2.6, 95% CI 2.33 to 2.86) remained stable from the previous report6 and did not increase with prolonged exposure (figure 1); the IRs for serious infection in patients <65 years and ≥65 years were 2.1 (95% CI 1.85 to 2.37) and 5.5 (95% CI 4.53 to 6.60), respectively. The EAIRs for serious infections were 2.13 (95% CI 1.61 to 2.76) for the 2 mg subset and 2.62 (95% CI 2.34 to 2.93) for the 4 mg subset of All-bari-RA (table 2). The most common serious infections were pneumonia (n=84, EAIR 0.6), herpes zoster (n=44, EAIR 0.3), urinary tract infection (n=25, EAIR 0.2) and cellulitis (n=23, EAIR 0.2). Multivariable risk factor analysis for serious infections in patients treated with baricitinib was previously reported.15

Figure 1.

Serious infections and herpes zoster over time for the All-bari-RA analysis set. Cumulative incidence rate of serious infections (A) and herpes zoster (B) by time period for the All-bari-RA analysis set. Data are presented by IR per 100 PY at risk. The number of total patients and patients with events, as well as the total PY per time period, are also provided. bari, baricitinib; IR, incidence rate; PY, patient-years; RA, rheumatoid arthritis.

The IR for herpes zoster (3.0, 95% CI 2.70 to 3.28) remained essentially unchanged from our previous report6 and did not increase with prolonged exposure (figure 1). The IR for herpes zoster was highest in Asia (IR 5.2, 95% CI 4.42 to 6.01). Majority of the herpes zoster cases were mild (39.8%) or moderate (54.5%) in severity and occurred mostly in patients who were older (75.1% in patients ≥50 years), without prior episodes (96.0%) or without prior vaccination (96.1%), and 91% of the patients recovered. There were 15 complicated cases of herpes zoster (ocular/ophthalmic, n=10 (2 were SAEs); herpes zoster meningitis, n=1 (SAE); palsy, n=4), and 42 cases of multidermatomal herpes zoster of which 18 were disseminated.

The IR for tuberculosis in All-bari-RA (0.1, 95% CI 0.08 to 0.20) (table 1) did not increase with prolonged exposure.6 No cases were reported with 2 mg, and the events occurred almost exclusively in endemic countries (Argentina, China, India, Lithuania, Mexico, Russia, South Africa, South Korea and Taiwan), with one report in the USA.

Malignancies

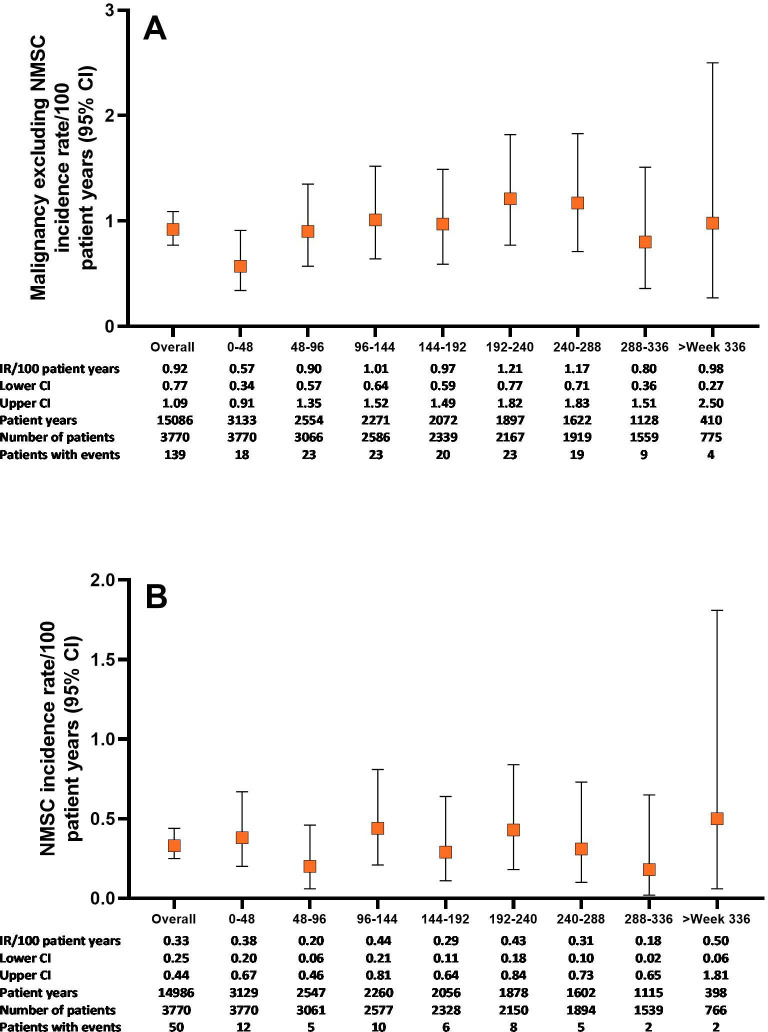

In All-bari-RA, the IR for malignancy (excluding NMSC) during the first 48 weeks was 0.6 (95% CI 0.34 to 0.91) and remained stable thereafter at approximately 1.0 (overall IR 0.9, 95% CI 0.77 to 1.09) (figure 2A). The most commonly reported types of malignancy were respiratory and mediastinal (n=26, EAIR=0.17), breast (n=23, EAIR=0.15) and gastrointestinal (n=19, EAIR=0.13) (table 3). The number of malignancy events, excluding NMSC, in each 5-year age category was compared with the expected number of malignancies based on SEER17 data (online supplemental figure 2). The resulting overall age-adjusted SIR was 1.07 (95% CI 0.90 to 1.26), suggesting similar incidence of malignancies as in the general US population. In All-bari-RA, the IR for NMSC was 0.3 (95% CI 0.25 to 0.44) and did not increase over time (figure 2B). The IR for lymphoma was 0.06 (95% CI 0.03 to 0.11), with diffuse large B cell lymphoma remaining the most common subtype.

Figure 2.

Malignancy-related events over time for the All-bari-RA analysis set. Cumulative incidence rate of (A) malignancy (excluding NMSC) and (B) NMSC by time period for the All-bari-RA analysis set. Data are presented by IR per 100 PY at risk. The number of total patients and patients with events, as well as the total PY per time period, are also provided in both panels. bari, baricitinib; IR, incidence rate; NMSC, non-melanoma skin cancer; PY, patient-years; RA, rheumatoid arthritis.

Table 3.

Exposure-adjusted incidence rates of malignancies excluding NMSC by high-level term

| High-level (group) term | n | EAIR (95% CI) |

| Respiratory and mediastinal neoplasms malignant and unspecified | 26 | 0.17 (0.11 to 0.25) |

| Breast neoplasms malignant and unspecified (including nipple) | 23 | 0.15 (0.10 to 0.23) |

| Gastrointestinal neoplasms malignant and unspecified | 19 | 0.13 (0.08 to 0.20) |

| Reproductive neoplasms female malignant and unspecified | 16 | 0.11 (0.06 to 0.17) |

| Reproductive neoplasms male malignant and unspecified (all reported cases were prostatic neoplasms) | 10 | 0.07 (0.03 to 0.12) |

| Skin neoplasms malignant and unspecified (other than NMSC) | 10 | 0.07 (0.03 to 0.12) |

| Renal and urinary tract neoplasms malignant and unspecified | 9 | 0.06 (0.03 to 0.11) |

| Lymphomas non-Hodgkin’s B cell | 6 | 0.04 (0.01 to 0.09) |

| Endocrine neoplasms malignant and unspecified | 4 | 0.03 (0.01 to 0.07) |

| Metastases | 3 | 0.02 (0.00 to 0.06) |

| Others* | 15 | 0.10 (0.06 to 0.16) |

*Others are all high-level group terms with 2 cases or fewer, including haematopoietic neoplasms (excluding leukaemias and lymphomas); hepatobiliary neoplasms malignant and unspecified; leukaemias; lymphomas non-Hodgkin’s T cell; lymphomas non-Hodgkin’s unspecified histology; miscellaneous and site unspecified neoplasms malignant and unspecified; neoplasm-related morbidities; nervous system neoplasms malignant and unspecified not elsewhere classified (NEC); not coded; ocular neoplasms; and soft tissue neoplasms malignant and unspecified.

EAIR, exposure-adjusted incidence rate; n, number of subjects in the specified category; NMSC, non-melanoma skin cancer.

Cardiovascular events

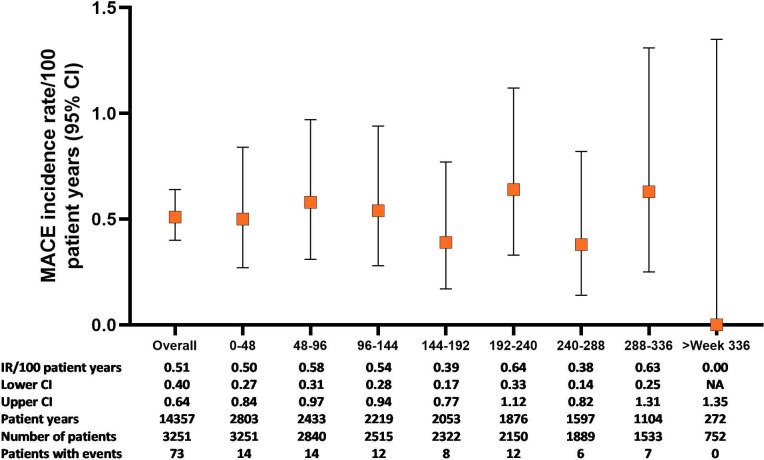

In All-bari-RA, the IR for positively adjudicated MACE was 0.5 (95% CI 0.40 to 0.64) and remained stable with longer baricitinib exposure (figure 3). The IRs for stroke, myocardial infarction and cardiovascular-related death were 0.3 (95% CI 0.19 to 0.36), 0.2 (95% CI 0.11 to 0.25) and 0.1 (95% CI 0.08 to 0.21), respectively. In the overall population, 54.8% of patients had ≥1 cardiovascular risk factor, with an IR for MACE of 0.70 (95% CI 0.53 to 0.92) in this group (table 4). In patients aged ≥50 with ≥1 cardiovascular risk factors (n=1325), 44 patients (3.3%) had MACE (IR 0.77, 95% CI 0.56 to 1.04). The EAIRs were similar in the 2 mg (0.42, 95% CI 0.21 to 0.74) and 4 mg (0.54, 95% CI 0.41 to 0.69) subsets of All-bari-RA (table 2).

Figure 3.

MACE over time for the All-bari-RA analysis set. Cumulative incidence rate of MACE (calculated for the five phase III studies and the LTE) by time period for the All-bari-RA analysis set. Data are presented by IR per 100 PY at risk. The number of total patients and patients with events, as well as the total PY per time period, are also provided. bari, baricitinib; IR, incidence rate; LTE, long-term extension; MACE, major adverse cardiovascular event; PY, patient-years; RA, rheumatoid arthritis.

Table 4.

Patient demographics and cardiovascular risk factors in patients with and without MACE

| Patients with MACE (N=73) | Patients without MACE (N=3178) | IR (95% CI) | All-bari-RA (N=3251)* |

|

| Patients with ≥1 cardiovascular risk factor, n (%)† | 55 (75.3) | 1725 (54.3) | 0.70 (0.53 to 0.92) | 1780 (54.8) |

| Age, mean (SD) | 58.9 (10.1) | 52.2 (12.2) | 52.3 (12.2) | |

| <50 years, n (%) | 13 (17.8) | 1214 (38.2) | 0.23 (0.12 to 0.40) | 1227 (37.7) |

| ≥50 years, n (%) | 60 (82.2) | 1964 (61.8) | 0.68 (0.52 to 0.88) | 2024 (62.3) |

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 29 (39.7) | 659 (20.7) | 0.93 (0.62 to 1.33) | 688 (21.2) |

| Female | 44 (60.3) | 2519 (79.3) | 0.39 (0.28 to 0.53) | 2563 (78.8) |

| BMI category, n (%) | ||||

| Underweight (<18.5 kg/m2) | 2 (2.8) | 138 (4.3) | 0.35 (0.04. 1.27) | 140 (4.3) |

| Normal or underweight (≥18.5 and <25 kg/m2) | 16 (22.2) | 1156 (36.4) | 0.31 (0.18 to 0.50) | 1172 (36.1) |

| Overweight (≥25 and <30 kg/m2) | 27 (37.5) | 951 (30.0) | 0.62 (0.41 to 0.90) | 978 (30.1) |

| Obese (≥30 kg/m2) | 27 (37.5) | 930 (29.3) | 0.65 (0.43 to 0.94) | 957 (29.5) |

| Current cigarette smoker, n (%) | 22 (30.1) | 581 (18.3) | 0.81 (0.51 to 1.23) | 603 (18.5) |

| Arteriosclerotic cardiovascular disease, n (%)‡ | 6 (8.2) | 68 (2.1) | 2.01 (0.74 to 4.37) | 74 (2.3) |

| Cardiac disorder (SOC), n (%) | 21 (28.8) | 292 (9.2) | 1.60 (0.99 to 2.45) | 313 (9.6) |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 43 (58.9) | 1126 (35.4) | 0.86 (0.62 to 1.15) | 1169 (36.0) |

| Diabetes, n (%) | 14 (19.2) | 283 (8.9) | 1.17 (0.64 to 1.97) | 297 (9.1) |

| Hypercholesterolaemia§, n (%) | 45 (61.6) | 1482 (46.6) | 0.68 (0.49 to 0.91) | 1527 (47.0) |

| Treatment-emergent thrombocytosis, n (%) | 4 (5.5) | 154 (4.8) | 0.57 (0.16 to 1.47) | 162 (5.0) |

| Baseline corticosteroid use, n (%) | 46 (61.6) | 1650 (51.9) | 0.60 (0.44 to 0.80) | 1695 (52.1) |

| HDL cholesterol <40 mg/dL, n (%) | 9 (12.3) | 280 (8.8) | 0.72 (0.33 to 1.37) | 289 (8.9) |

*All-bari-RA for MACE is only from phase II and III studies where MACE was adjudicated.

†The five possible cardiovascular risk factors included in this analysis were current smoker, hypertension, HDL cholesterol <40 mg/dL, diabetes mellitus and ASCVD.

‡Arteriosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) is defined at baseline by medical history of myocardial infarction, coronary artery bypass, stroke, transient ischaemic attack or peripheral vascular disease.

§Hypercholesterolaemia was defined by (1) baseline total cholesterol ≥200 mg/dL or LDL ≥130 mg/dL; or (2) preferred terms of ‘blood cholesterol abnormal, blood cholesterol increased, LDL abnormal, LDL increased, very LDL abnormal, very LDL increased, LDL/HDL ratio increased, total cholesterol/HDL ratio increased, total cholesterol/HDL ratio abnormal, lipids abnormal’; and high-level terms of ‘elevated cholesterol, hyperlipidaemias NEC’.

bari, baricitinib; BMI, body mass index; HDL, high-density lipoprotein; HDL, high-density lipoprotein; IR, incidence rate; LDL, low-density lipoprotein; MACE, major adverse cardiovascular event; n, number of patients in the specified category; N, number of patients in the analysis set; RA, rheumatoid arthritis; SOC, system organ class.

Venous thromboembolic events

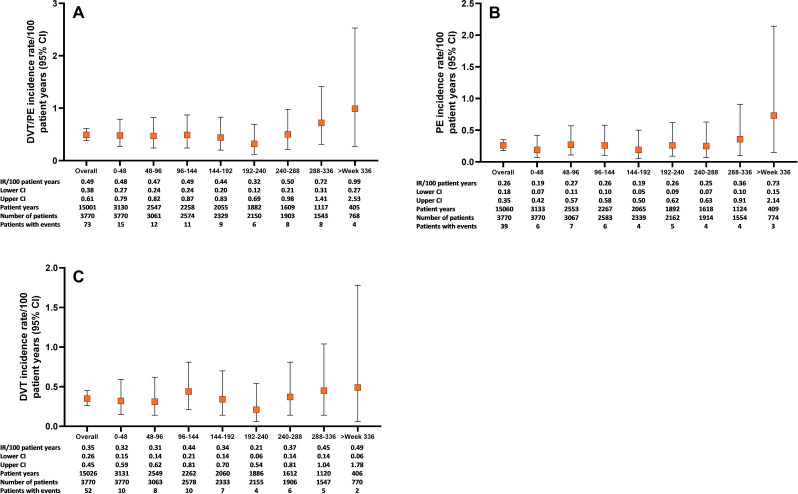

In All-bari-RA, the overall IRs for DVT/PE, DVT and PE were 0.49 (95% CI 0.38 to 0.61), 0.35 (95% CI 0.26 to 0.45) and 0.26 (95% CI 0.18 to 0.35) (table 1) and remained stable over time (figure 4). The EAIRs for DVT/PE were similar in the 2 mg (0.49, 95% CI 0.26 to 0.83) and 4 mg (0.51, 95% CI 0.39 to 0.66) subsets of All-bari-RA (table 2).

Figure 4.

Thromboembolic events over time for the All-bari-RA analysis set. Cumulative incidence rate of (A) DVT/PE, (B) PE and (C) DVT by time period for the All-bari-RA analysis set. Data are presented by IR per 100 PY at risk. The number of total patients and patients with events, as well as the total PY per time period, are also provided in both panels. bari, baricitinib; DVT, deep vein thrombosis; IR, incidence rate; PE, pulmonary embolism; PY, patient-years; RA, rheumatoid arthritis.

Diverticulitis and lower gastrointestinal perforation

There were 23 treatment-emergent events of diverticulitis (EAIR 0.15). Diverticulitis occurred in patients with risk factors including pre-existing diverticulosis, older age, overweight and obesity, and chronic corticosteroid or non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) treatment. Since the prior reported analysis, five additional cases of gastrointestinal perforations have been reported in All-bari-RA, bringing the total to nine (IR 0.06, 95% CI 0.03 to 0.11) (table 1). There were seven (IR 0.05) lower gastrointestinal perforations.

Laboratory

In All-bari-RA treatment-emergent shifts of selected laboratory parameters are presented in online supplemental table 4. Changes in selected haematological parameters following once-daily baricitinib dose were previously disclosed.16 The IR for laboratory-related treatment-emergent events included anaemia (1.74, 95% CI 1.53 to 1.97), neutropaenia (0.4, 95% CI 0.31 to 0.52), lymphopaenia (1.04, 95% CI 0.89 to 1.22) and thrombocytosis (0.3, 95% CI 0.24 to 0.43).

Discussion

We report an updated assessment of safety from an integrated database of baricitinib in patients with RA through 9.3 years of treatment for a total of 14 744 years of patient exposure, in which baricitinib maintained a safety profile similar to that previously reported.6 The incidence of death, SAEs (including infections), MACE and malignancy in the baricitinib analysis is similar to those observed for other therapeutic trials of JAK inhibitors17–20 and biologic DMARDs.21 Few patients (EAIR 4.7) discontinued due to adverse events. In the baricitinib 2 mg and 4 mg subsets of All-bari-RA, the incidence of AESI was generally similar between the two dosing groups.

Although the incidence of deaths appears to be increasing over time, the overall IR for death (0.56) and the EAIR per dose (2 mg, 0.56; 4 mg, 0.57) are lower than the reported IR of 1.5–2.4/100 patient-years in epidemiological studies of RA.22 23 The risk of mortality in patients treated with baricitinib was not increased compared with the general population after controlling for age and sex, with the SMR for baricitinib <1. Causes of death for baricitinib-treated patients are in line with the percentages of total deaths in the US general population,24 as well as those reported in clinical trials of other RA therapies.17 20 25 26

Due to disease and therapeutic interventions, patients with RA are at an elevated risk of infection. The EAIR of treatment-emergent infections for patients in the current analysis decreased to 17.1 from previously reported EAIRs of 23.7–26.9.6 15 Similarly, EAIRs for TEAEs that led to temporary or permanent discontinuations from study drug have continued to decrease with prolonged exposure. The overall incidence of serious infections has remained stable over time. EAIRs of serious infections in the baricitinib 2 mg group could be numerically lower than 4 mg, related to lower disease activity and lower corticosteroid and methotrexate (MTX) use at the start of dose. Infections leading to death were rare in this patient population. The incidence of herpes zoster remained stable and is similar to that of other JAK inhibitors, including tofacitinib27 and upadacitinib.28 In our study, the rates of herpes zoster were highest in Asia and driven by higher rates in Japan, Taiwan and South Korea, as shown in a previous report of herpes zoster in patients treated with baricitinib.29

There were an additional 54 cases of malignancy (excluding NMSC) since our previous report, with a similar IR (0.9 in the current analysis vs 0.8).6 Patients with RA are predisposed to an increased risk of malignancy, especially lymphoma, lung cancer and NMSC.30 The incidence of lymphoma remained unchanged at 0.06 from previous reports of baricitinib6 and similar to rates reported for other RA therapies, including an IR of 0.1 for adalimumab21 and 0.096 in patients using TNFi.31

The effects of JAK inhibitors on the risk of malignancies remain unclear and need further research. Data reported from a recent systematic review and meta-analysis concluded that there was no increased risk of malignancies in patients who combined a JAK inhibitor with MTX compared with those treated with MTX alone.32 It must be noted that 79% of the patients included in our analysis had concomitant use of MTX. Furthermore, evidence from observational studies reported no increased risk of malignancy between other JAK inhibitors (tofacitinib) compared with conventional synthetic DMARDs or biologic DMARDs, such as TNFi.33 34 However, preliminary findings from a prospective, randomised, postmarketing safety study of tofacitinib (A3921133, NCT02092467), comparing outcomes between treatments in patients with RA who were aged ≥50 years and had ≥1 additional cardiovascular risk factor, showed an increased rate of malignancies for tofacitinib (IR/100 patient-years, 1.13) relative to TNFi (IR/100 patient-years, 0.77),35 with the observed IR for tofacitinib remaining within reported boundaries in patients treated with biologic DMARDs (IR 0.8–2.3).36 Further data on this study are, however, needed to appropriately contextualise these findings. In this report, the observed number of malignancies for the baricitinib population was similar to the expected events for the US population sample, resulting in an SIR of 1.07. Although the present long-term data on baricitinib do not show an increased risk of malignancy, lung cancer or lymphoma with longer exposure to baricitinib, long-term direct comparative data are not yet available from the ongoing randomised trial of baricitinib versus TNFi.

Patients with RA are at an increased risk of DVT and PE (IR 0.3–0.8/100 patient-years)16 compared with the general population.37 38 In this analysis, the IR of DVT/PE in patients treated with baricitinib was consistent with previously reported data6 39 and comparable with other JAK inhibitors.16 17 40 41 In the subset of patients receiving baricitinib 2 mg or 4 mg, the EAIRs were similar between dose groups and comparable with those previously reported.6 While recent meta-analyses of randomised controlled trials of JAK inhibitors (including tofacitinib, baricitinib and upadacitinib) in patients with RA have shown no increased risk of venous thromboembolic events during the placebo-controlled periods, longer-term data are needed to fully characterise the risk of these events.42 43

The incidence of MACE in the current study (0.5) remained low and stable from previous reports.6 37 The IRs showed no increase with longer exposure to baricitinib despite the ageing of the study population and were observed at similar rates to TNFi (0.62/100 patient-years)44 and other JAK inhibitors (0.4/100 patient-years; 0.6–1.0/100 patient-years).18 19 42 The EAIR of MACE was similar between baricitinib 2 mg (0.42) and 4 mg (0.54). Of the patients, 55% had at least one of five cardiovascular risk factors at baseline used in the analysis (current smoker, hypertension, diabetes, history of atherosclerotic disorder or HDL cholesterol <40 mg/dL), and as expected the IR for MACE was higher in this at-risk subpopulation (0.70), remaining similar to rates reported for TNFi in the preliminary data of the tofacitinib postmarketing study (IR/100 patient-years, 0.98 for tofacitinib compared with 0.73 for TNFi).35 40 It should be noted that the higher IR observed with tofacitinib in a study (A3921133) remains within the wide boundaries (IR 0.2–2.4) reported for MACE in epidemiological studies within the general RA population.44–47 It has been hypothesised that TNFi could provide a protective effect against MACE.48 49

The EAIR for diverticulitis in the current study (0.15) is consistent with published data among patients with RA reported at 0.250–52 and consistent with IR for diverticulitis of 0.27 among a general population of similar mean age.53 Important risk factors for diverticulitis in the general population include age, obesity, diet, smoking and medication use, in particular opioids, corticosteroids and NSAIDs.54 55 Diverticulitis in our study occurred in patients with risk factors. The IR for gastrointestinal perforations (0.06) remains low in the context of reports from tofacitinib, tocilizumab and other biologic DMARDs in real-world data56 and upadacitinib (0.08/100 patient-years).19

Moderate decreases in haemoglobin and neutrophils and increases in transaminase and creatinine phosphokinase observed with baricitinib were consistent with laboratory changes previously reported and observed with other JAK inhibitors.19 20

As previously reported, there are limitations to this analysis, including lack of control group in the LTE and possible modifications of background therapy by clinicians in the study extension; however, these factors more closely resemble real-world treatment plans. Additionally, during the LTE, because dose changes were allowed whether for tapering from baricitinib 4 mg to 2 mg or rescue to baricitinib 4 mg, the ability to assess the effects of dose on outcomes is restricted. Despite this limitation, the subset analysis provides a view of dose time of event for death, serious infections, MACE and DVT/PE. The study is also limited by survival bias; patients with adverse events and/or lack of efficacy that led to discontinuation from their originating study were not included in the LTD, therefore yeilding a more robust cohort for analysis at the end of 9 years. All data in this analysis are from randomised controlled trials with specific inclusion criteria and protocols, which may limit the applicability of these data to clinical practice. Caution should also be taken when interpreting the results for patients with the shortest and longest baricitinib exposure due to differences in patient numbers, which are fewer in later months. Safety in the baricitinib placebo-controlled analysis set is not included in the current study as there are no new data from the short placebo-controlled period that was previously reported.6

In summary, this report describes the highest level of patient exposure to baricitinib across the spectrum of the RA population, including the LTE study, RA-BEYOND, which is now completed. The study included 3770 patients and over 14 000 PYE with rigorous safety monitoring throughout the clinical trials and robust mortality data. Baricitinib maintained a safety profile similar to that previously reported, with rates of safety events of special interest (including deaths, malignancies, MACE and DVT/PE) remaining stable through exposures up to 9.3 years.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank the patients, the investigators and the study staff who were involved in these studies. Medical writing support, under the guidance of the authors, was provided by Kathy Oneacre, MA, and editing support by Cynthia Rae Abbott of Syneos Health (Morrisville, North Carolina, USA), in accordance with Good Publication Practice guidelines.

Footnotes

Handling editor: Francis Berenbaum

Contributors: PCT, NB, WD, JRT: conception and design of the study; interpretation of data for the study; drafting and critical revision of the manuscript. TT, PD, KLW: interpretation of data for the study and critical revision of the manuscript. G-RRB, JSS: acquisition and interpretation of data for the study and critical revision of the manuscript. MI: analysis and interpretation of data for the study; critical revision of the manuscript. All authors approved the manuscript’s content before submission. PCT is author acting as guarantor.

Funding: Baricitinib is developed by Eli Lilly and Company, under licence from Incyte Corporation. This study was sponsored by Eli Lilly and Company. Medical writing and editing support was funded by Eli Lilly and Company (Indianapolis, Indiana, USA).

Competing interests: PCT has received consultant fees from AbbVie, Biogen, Galapagos, Gilead, GlaxoSmithKline, Janssen, Lilly, BMS, Pfizer, Roche, Celltrion, Sanofi, Nordic Pharma, Fresenius and UCB; and grant/research support from Celgene, Galapagos, Janssen and Lilly. TT has received grant/research support from Daiichi Sankyo, Takeda, Nippon Kayaku, JCR Pharma, Astellas, Chugai, AbbVie GK, Asahi Kasei Pharma, Mitsubishi Tanabe, UCB Japan and Eisai; consulting fees from Astellas, AbbVie GK, Gilead, Daiichi Sankyo, Taisho Pharma, Nippon Kayaku, Bristol-Myers Squibb, GlaxoSmithKline, Eli Lilly, Novartis, Mitsubishi Tanabe and Chugai; and speakers’ bureau fees from Mitsubishi Tanabe, Pfizer, Astellas, Daiichi Sankyo, Eisai, Sanofi, Novartis, Eli Lilly, Gilead, AbbVie GK, Bristol-Myers Squibb and Chugai. G-RRB has received honoraria for lectures and consulting from AbbVie, Gilead, Lilly and Pfizer. PD has received fees for speakers' bureau from BMS, Sanofi, Eli Lilly and Celltrion. JSS has received grant/research support from AbbVie, Eli Lilly and Company, Janssen, MSD, Novartis, Pfizer and Roche; and consultancy fees from AbbVie, Amgen, AstraZeneca, Astro, BMS, Celgene, Celltrion, Chugai, Eli Lilly and Company, Gilead, ILTOO, Janssen, MedImmune, MSD, Novartis, Pfizer, Roche, Samsung, Sanofi and UCB. WD, MI, JRT and NB are employees and stockholders of Eli Lilly and Company. KLW has received grant/research support from Pfizer and BMS; and consulting fees from Pfizer, UCB, AbbVie, Eli Lilly and Company, Amgen, BMS, Galapagos and Gilead.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Data availability statement

Eli Lilly and Company provides access to all individual participant data collected during the trial, after anonymisation, with the exception of pharmacokinetic or genetic data. Data are available to request six months after the indication studied has been approved in the United States and the European Union and after primary publication acceptance, whichever is later. No expiration date of data requests is currently set once data are made available. Access is provided after a proposal has been approved by an independent review committee identified for this purpose and after receipt of a signed data sharing agreement. Data and documents, including the study protocol, statistical analysis plan, clinical study report, and blank or annotated case report forms, will be provided in a secure data sharing environment. For details on submitting a request, see the instructions provided at www.vivli.org.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not required.

Ethics approval

Trials were conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and Good Clinical Practice guidelines and were approved by each centre’s institutional review board.

References

- 1. Fridman JS, Scherle PA, Collins R, et al. Selective inhibition of JAK1 and JAK2 is efficacious in rodent models of arthritis: preclinical characterization of INCB028050. J Immunol 2010;184:5298–307. 10.4049/jimmunol.0902819 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Taylor PC, Keystone EC, van der Heijde D, et al. Baricitinib versus placebo or adalimumab in rheumatoid arthritis. N Engl J Med 2017;376:652–62. 10.1056/NEJMoa1608345 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Genovese MC, Kremer J, Zamani O, et al. Baricitinib in patients with refractory rheumatoid arthritis. N Engl J Med 2016;374:1243–52. 10.1056/NEJMoa1507247 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Dougados M, van der Heijde D, Chen Y-C, et al. Baricitinib in patients with inadequate response or intolerance to conventional synthetic DMARDs: results from the RA-BUILD study. Ann Rheum Dis 2017;76:88–95. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2016-210094 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Fleischmann R, Schiff M, van der Heijde D, et al. Baricitinib, methotrexate, or combination in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and no or limited prior disease-modifying antirheumatic drug treatment. Arthritis Rheumatol 2017;69:506–17. 10.1002/art.39953 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Genovese MC, Smolen JS, Takeuchi T, et al. Safety profile of baricitinib for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis over a median of 3 years of treatment: an updated integrated safety analysis. Lancet Rheumatol 2020;2:e347–57. 10.1016/S2665-9913(20)30032-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Genovese MC, Smolen JS, Takeuchi T, et al. Safety profile of baricitinib for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis up to 8.4 years: an updated integrated safety analysis [abstract]. Ann Rheum Dis 2020;79:642.1–3. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2020-eular.1723 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Payne C, Zhang X, Shahri N. Evaluation of potential drug-drug interactions with baricitinib. J Manag Care Spect Pharm 2014;20:S51–2. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Keystone EC, Taylor PC, Drescher E, et al. Safety and efficacy of baricitinib at 24 weeks in patients with rheumatoid arthritis who have had an inadequate response to methotrexate. Ann Rheum Dis 2015;74:333–40. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2014-206478 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Tanaka Y, Emoto K, Cai Z, et al. Efficacy and safety of baricitinib in Japanese patients with active rheumatoid arthritis receiving background methotrexate therapy: a 12-week, double-blind, randomized placebo-controlled study. J Rheumatol 2016;43:504–11. 10.3899/jrheum.150613 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Aletaha D, Smolen J. The simplified disease activity index (SDAI) and the clinical disease activity index (CDAI): a review of their usefulness and validity in rheumatoid arthritis. Clin Exp Rheumatol 2005;23:S100–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Baber N. International Conference on harmonisation of technical requirements for registration of pharmaceuticals for human use (ICH). Br J Clin Pharmacol 1994;37:401–4. 10.1111/j.1365-2125.1994.tb05705.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Howlader N, Noone AM, Krapcho M. Seer cancer statistics review, 1975-2018. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute, 2021. https://seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2018/ [Google Scholar]

- 14. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention,, National Center for Health Statistics . Underlying cause of death 1999-2019 on CDC wonder online database, released in 2020. data are from the multiple cause of death files, 1999–2019, as compiled from data provided by the 57 vital statistics jurisdictions through the vital statistics cooperative program. Available: http://wonder.cdc.gov/ucd-icd10.html [Accessed 15 July 2021].

- 15. Winthrop KL, Harigai M, Genovese MC, et al. Infections in baricitinib clinical trials for patients with active rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 2020;79:1290–7. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2019-216852 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kay J, Harigai M, Rancourt J, et al. Changes in selected haematological parameters associated with JAK1/JAK2 inhibition observed in patients with rheumatoid arthritis treated with baricitinib. RMD Open 2020;6:e001370. 10.1136/rmdopen-2020-001370 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Cohen SB, Tanaka Y, Mariette X, et al. Long-term safety of tofacitinib for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis up to 8.5 years: integrated analysis of data from the global clinical trials. Ann Rheum Dis 2017;76:1253–62. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2016-210457 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Cohen SB, Tanaka Y, Mariette X, et al. Long-Term safety of tofacitinib up to 9.5 years: a comprehensive integrated analysis of the rheumatoid arthritis clinical development programme. RMD Open 2020;6:e001395. 10.1136/rmdopen-2020-001395 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Cohen SB, van Vollenhoven RF, Winthrop KL. Correction: Safety profile of upadacitinib in rheumatoid arthritis: integrated analysis from the SELECT phase III clinical programme. Ann Rheum Dis 2021;80:304–11. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2020-218510 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Wollenhaupt J, Silverfield J, Lee EB, et al. Safety and efficacy of tofacitinib, an oral Janus kinase inhibitor, for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis in open-label, longterm extension studies. J Rheumatol 2014;41:837–52. 10.3899/jrheum.130683 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Burmester GR, Panaccione R, Gordon KB, et al. Adalimumab: long-term safety in 23 458 patients from global clinical trials in rheumatoid arthritis, juvenile idiopathic arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis, psoriatic arthritis, psoriasis and Crohn's disease. Ann Rheum Dis 2013;72:517–24. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2011-201244 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Humphreys JH, Warner A, Chipping J, et al. Mortality trends in patients with early rheumatoid arthritis over 20 years: results from the Norfolk arthritis register. Arthritis Care Res 2014;66:1296–301. 10.1002/acr.22296 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Sparks JA, Chang S-C, Liao KP, et al. Rheumatoid arthritis and mortality among women during 36 years of prospective follow-up: results from the nurses' health study. Arthritis Care Res 2016;68:753–62. 10.1002/acr.22752 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. CDC National Center for Health Statistics . FastStats – leading causes of death, 2021. Available: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/fastats/leading-causes-of-death.htm [Accessed 15 Jul 2021].

- 25. Schiff MH, Kremer JM, Jahreis A, et al. Integrated safety in tocilizumab clinical trials. Arthritis Res Ther 2011;13:R141. 10.1186/ar3455 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Klareskog L, Gaubitz M, Rodríguez-Valverde V, et al. Assessment of long-term safety and efficacy of etanercept in a 5-year extension study in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Clin Exp Rheumatol 2011;29:238–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Winthrop KL, Curtis JR, Lindsey S, et al. Herpes zoster and tofacitinib: clinical outcomes and the risk of concomitant therapy. Arthritis Rheumatol 2017;69:1960–8. 10.1002/art.40189 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. van Vollenhoven R, Takeuchi T, Pangan AL. A phase 3, randomized, controlled trial comparing upadacitinib monotherapy to MTX monotherapy in MTX-naïve patients with active rheumatoid arthritis [abstract]. Arthritis Rheumatol 2018;70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Chen Y, Chen Y, Smolen JS. Incidence rate and characterization of herpes zoster in patients with moderate-to-severe rheumatoid arthritis: an update from baricitinib clinical studies. Ann Rheum Dis 2019;78:755. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Simon TA, Thompson A, Gandhi KK, et al. Incidence of malignancy in adult patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a meta-analysis. Arthritis Res Ther 2015;17:212. 10.1186/s13075-015-0728-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Askling J, Baecklund E, Granath F, et al. Anti-Tumour necrosis factor therapy in rheumatoid arthritis and risk of malignant lymphomas: relative risks and time trends in the Swedish biologics register. Ann Rheum Dis 2009;68:648–53. 10.1136/ard.2007.085852 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Solipuram V, Mohan A, Patel R, et al. Effect of Janus kinase inhibitors and methotrexate combination on malignancy in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Auto Immun Highlights 2021;12:8. 10.1186/s13317-021-00153-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Kremer J, Bingham C, Cappelli L. Comparison of malignancy and mortality rates between tofacitinib and biologic DMARDs in clinical practice: Five-year results from a US-based rheumatoid arthritis registry [abstract]. Arthritis Rheumatol 2019;71. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Xie W, Yang X, Huang H, et al. Risk of malignancy with non-TNFi biologic or tofacitinib therapy in rheumatoid arthritis: a meta-analysis of observational studies. Semin Arthritis Rheum 2020;50:930–7. 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2020.08.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Pfizer, Inc . Pfizer share co-primary endpoint results from post-marketing required safety study of XELJANZ (Tofacitinib) in subjects with rheumatioid arthritis (RA) [Press release]. Available: https://www.pfizer.com/news/press-release/press-release-detail/pfizer-shares-co-primary-endpoint-results-post-marketing [Accessed 27 Jan 2021].

- 36. Kim SC, Pawar A, Desai RJ, et al. Risk of malignancy associated with use of tocilizumab versus other biologics in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a multi-database cohort study. Semin Arthritis Rheum 2019;49:222–8. 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2019.03.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Kim SC, Schneeweiss S, Liu J, et al. Risk of venous thromboembolism in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Care Res 2013;65:NA–7. 10.1002/acr.22039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Ogdie A, Kay McGill N, Shin DB, et al. Risk of venous thromboembolism in patients with psoriatic arthritis, psoriasis and rheumatoid arthritis: a general population-based cohort study. Eur Heart J 2018;39:3608–14. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehx145 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Taylor PC, Weinblatt ME, Burmester GR, et al. Cardiovascular safety during treatment with baricitinib in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheumatol 2019;71:1042–55. 10.1002/art.40841 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Burmester GR, Nash P, Sands BE, et al. Adverse events of special interest in clinical trials of rheumatoid arthritis, psoriatic arthritis, ulcerative colitis and psoriasis with 37 066 patient-years of tofacitinib exposure. RMD Open 2021;7:e001595. 10.1136/rmdopen-2021-001595 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Mease P, Charles-Schoeman C, Cohen S, et al. Incidence of venous and arterial thromboembolic events reported in the tofacitinib rheumatoid arthritis, psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis development programmes and from real-world data. Ann Rheum Dis 2020;79:1400–13. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2019-216761 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Xie W, Huang Y, Xiao S, et al. Impact of Janus kinase inhibitors on risk of cardiovascular events in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Ann Rheum Dis 2019;78:1048–54. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2018-214846 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Bilal J, Riaz IB, Naqvi SAA, et al. Janus kinase inhibitors and risk of venous thromboembolism: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Mayo Clin Proc 2021;96:1861–73. 10.1016/j.mayocp.2020.12.035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Curtis JR, Mariette X, Gaujoux-Viala C, et al. Long-Term safety of certolizumab pegol in rheumatoid arthritis, axial spondyloarthritis, psoriatic arthritis, psoriasis and Crohn's disease: a pooled analysis of 11 317 patients across clinical trials. RMD Open 2019;5:e000942. 10.1136/rmdopen-2019-000942 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Lauper K, Courvoisier DS, Chevallier P, et al. Incidence and prevalence of major adverse cardiovascular events in rheumatoid arthritis, psoriatic arthritis, and axial spondyloarthritis. Arthritis Care Res 2018;70:1756–63. 10.1002/acr.23567 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Cooksey R, Brophy S, Kennedy J, et al. Cardiovascular risk factors predicting cardiac events are different in patients with rheumatoid arthritis, psoriatic arthritis, and psoriasis. Semin Arthritis Rheum 2018;48:367–73. 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2018.03.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. de Thurah A, Andersen IT, Tinggaard AB, et al. Risk of major adverse cardiovascular events among patients with rheumatoid arthritis after initial CT-based diagnosis and treatment. RMD Open 2020;6:e001113. 10.1136/rmdopen-2019-001113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Singh S, Fumery M, Singh AG, et al. Comparative risk of cardiovascular events with biologic and synthetic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Arthritis Care Res 2020;72:561–76. 10.1002/acr.23875 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Roubille C, Richer V, Starnino T, et al. The effects of tumour necrosis factor inhibitors, methotrexate, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and corticosteroids on cardiovascular events in rheumatoid arthritis, psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Rheum Dis 2015;74:480–9. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2014-206624 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Strangfeld A, Richter A, Siegmund B, et al. Risk for lower intestinal perforations in patients with rheumatoid arthritis treated with tocilizumab in comparison to treatment with other biologic or conventional synthetic DMARDs. Ann Rheum Dis 2017;76:504–10. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2016-209773 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Pawar A, Desai RJ, Solomon DH, et al. Risk of serious infections in tocilizumab versus other biologic drugs in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a multidatabase cohort study. Ann Rheum Dis 2019;78:456–64. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2018-214367 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Harrold LR, Litman HJ, Saunders KC, et al. One-Year risk of serious infection in patients treated with certolizumab pegol as compared with other TNF inhibitors in a real-world setting: data from a national U.S. rheumatoid arthritis registry. Arthritis Res Ther 2018;20:2. 10.1186/s13075-017-1496-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Bharucha AE, Parthasarathy G, Ditah I, et al. Temporal trends in the incidence and natural history of diverticulitis: a population-based study. Am J Gastroenterol 2015;110:1589–96. 10.1038/ajg.2015.302 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Lee TH, Setty PT, Parthasarathy G, et al. Aging, obesity, and the incidence of diverticulitis: a population-based study. Mayo Clin Proc 2018;93:1256–65. 10.1016/j.mayocp.2018.03.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Morris AM, Regenbogen SE, Hardiman KM, et al. Sigmoid diverticulitis: a systematic review. JAMA 2014;311:287–97. 10.1001/jama.2013.282025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Xie F, Yun H, Bernatsky S, et al. Brief report: risk of gastrointestinal perforation among rheumatoid arthritis patients receiving tofacitinib, tocilizumab, or other biologic treatments. Arthritis Rheumatol 2016;68:2612–7. 10.1002/art.39761 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

annrheumdis-2021-221276supp001.pdf (266.1KB, pdf)

Data Availability Statement

Eli Lilly and Company provides access to all individual participant data collected during the trial, after anonymisation, with the exception of pharmacokinetic or genetic data. Data are available to request six months after the indication studied has been approved in the United States and the European Union and after primary publication acceptance, whichever is later. No expiration date of data requests is currently set once data are made available. Access is provided after a proposal has been approved by an independent review committee identified for this purpose and after receipt of a signed data sharing agreement. Data and documents, including the study protocol, statistical analysis plan, clinical study report, and blank or annotated case report forms, will be provided in a secure data sharing environment. For details on submitting a request, see the instructions provided at www.vivli.org.