Abstract

Objective

HCV-genotype 4 infections are a major cause of liver diseases in the Middle East/Africa with certain subtypes associated with increased risk of direct-acting antiviral (DAA) treatment failures. We aimed at developing infectious genotype 4 cell culture systems to understand the evolutionary genetic landscapes of antiviral resistance, which can help preserve the future efficacy of DAA-based therapy.

Design

HCV recombinants were tested in liver-derived cells. Long-term coculture with DAAs served to induce antiviral-resistance phenotypes. Next-generation sequencing (NGS) of the entire HCV-coding sequence identified mutation networks. Resistance-associated substitutions (RAS) were studied using reverse-genetics.

Result

The in-vivo infectious ED43(4a) clone was adapted in Huh7.5 cells, using substitutions identified in ED43(Core-NS5A)/JFH1-chimeric viruses combined with selected NS5B-changes. NGS, and linkage analysis, permitted identification of multiple genetic branches emerging during culture adaptation, one of which had 31 substitutions leading to robust replication/propagation. Treatment of culture-adapted ED43 with nine clinically relevant protease-DAA, NS5A-DAA and NS5B-DAA led to complex dynamics of drug-target-specific RAS with coselection of genome-wide substitutions. Approved DAA combinations were efficient against the original virus, but not against variants with RAS in corresponding drug targets. However, retreatment with glecaprevir/pibrentasvir remained efficient against NS5A inhibitor and sofosbuvir resistant variants. Recombinants with specific RAS at NS3-156, NS5A-28, 30, 31 and 93 and NS5B-282 were viable, but NS3-A156M and NS5A-L30Δ (deletion) led to attenuated phenotypes.

Conclusion

Rapidly emerging complex evolutionary landscapes of mutations define the persistence of HCV-RASs conferring resistance levels leading to treatment failure in genotype 4. The high barrier to resistance of glecaprevir/pibrentasvir could prevent persistence and propagation of antiviral resistance.

Keywords: HCV, drug resistance, Hepatitis C, genotype

Significance of this study.

What is already known about this subject?

HCV genotype 4 is highly prevalent in the Middle East and Africa, particularly in Egypt.

Direct-acting antivirals (DAAs) are efficient against genotype 4, but treatment failures in general, and involving specific subtypes, have been reported.

RAS NS5B-S282T is more commonly found in genotype 4-infected patients compared with other genotypes.

Retreatment in low-income countries is challenging, thus, it is important to define optimal first-line therapies.

There is a lack of efficient infectious HCV genotype 4 cell culture systems, which challenges studies of antiviral resistance.

What are the new findings?

An in vivo infectious HCV genotype 4a clone (strain ED43) was adapted to efficiently replicate and propagate in cell culture.

Haplotype reconstruction based on next-generation sequencing showed complex evolutionary networks of resistance-associated substitutions (RASs) emerging in drug targets with coselection of genome-wide substitutions during treatment with DAA.

Baseline NS5A resistance had a central role in treatment failure.

Retreatment with glecaprevir/pibrentasvir remained efficient against viruses with baseline NS5A inhibitor and sofosbuvir resistance.

We observed persistence of the NS5B-S282T RAS in genotype 4 in culture.

Significance of this study.

How might it impact on clinical practice in the foreseeable future?

Our study provides a unique overview of the evolutionary landscape underlying the emergence of RASs conferring viral resistance to DAAs in cell culture, which provides valuable information for strategies to avoid emergence and spread of DAA-resistant variants for prevention of future treatment failures in the clinic.

The highly efficient genotype 4a infectious system provides a key tool for development and testing of vaccine candidates, a key intervention to eliminate HCV at a global scale.

Introduction

HCV infection remains an important health threat, with 71 million chronically infected people, resulting in 400 thousand deaths yearly. The use of direct-acting antivirals (DAA) targeting the viral nonstructural 3 protease (NS3P), NS5A and NS5B-polymerase increased cure rates to >90%.1 However, emergence of resistance-associated substitutions (RAS)1 2 compromises efficacy of DAA regimens.3 4 Treatment failures have been widely reported and will increase as patients are treated worldwide.1

HCV shows extensive genetic diversity with eight major genotypes and >90 subtypes.5–7 Genotype 4 represents ~8% of infections worldwide, being highly predominant in the Middle-East and North and Central Africa.5 Particularly, ~93% of >5 million HCV infections in Egypt were caused by genotype 4.5 This genotype is highly heterogeneous with >18 recognised subtypes.5 6 8 In addition, due to human migration and increasing transmission among intravenous drug users and individuals with high-risk sexual practices, the prevalence of genotype 4 is currently increasing in Europe.5 Subtype 4a is common, particularly in Egypt, the origin of prototype 4a strain ED43.5 9 10

Approved DAA regimens are highly efficient against genotype 4.11–13 However, high rates of treatment failure with preexisting and emergent RASs were recently reported in subsets of genotype 4-infected patients.14–19 In Egypt alone, ~2.4 million patients have been treated with DAAs, in particular, various NS5A inhibitors combined with the polymerase-inhibitor sofosbuvir.20 Although the sustained virologic response (SVR) rates were >90%, treatment failures were reported.18 Antiviral resistance will not necessarily alter the current treatment guidelines, but it could potentially affect treatment options in the future. Although DAA-resistance occurs at low prevalence, the extensive cross-resistance between the same molecular classes of drugs could limit future treatment options, especially since no additional antivirals are being developed for the treatment of HCV. Thus, generating new knowledge on viral resistance to DAAs is of great importance to prevent treatment failure in the future and to avoid the emergence and transmission of DAA-resistant viruses to highly exposed populations. This effort will require detailed understanding of the mechanisms underlying emergence of RASs.

In addition, prophylactic HCV vaccines will be essential for preventing transmission globally. Efficient infectious cell culture systems representing the major HCV genotypes can play an important role in the development and testing of vaccine candidates. Vaccine candidates based on inactivated whole-virus-particles are dependent on the efficient production of the virus in cell culture, which for HCV can only be achieved after virus adaptation, thus, understanding such processes is fundamental to generate relevant candidates. In addition, evaluation of the ability of vaccines to induce broad cross-genotype neutralising antibodies requires the establishment of culture systems representing the genetic heterogeneity of HCV, and here infectious full-length systems are most relevant since they recapitulate the entire viral life cycle.21–23

Efficient full-length infectious culture systems have been developed for selected strains of genotypes 1a, 2a, 2b, 3a and 6a after complex adaptation processes.3 4 24–28 For genotype 4, a full-length cell culture system has recently been reported, but with limited propagation in Huh7.5 cells,29 thus, a high titre system is still required for most studies on the viral life cycle, antivirals and vaccine development. Here, we aimed at developing a robust and efficient (high infectivity titre) full-length infectious system for HCV genotype 4a, permitting in-depth analysis of evolutionary networks underlying the emergence of DAA-resistance and assessments of the efficacy and barrier to resistance of clinically relevant DAA regimens.

Materials and methods

Construction of HCV genotype 4a clones

The in vivo infectious strain ED43 clone was described.10 The chimeric genome comprising ED43 Core-NS5A (C5A) and JFH1-NS5B and—untranslated regions (UTRs) was generated by replacing the 5’UTR from ED43 5’UTR-NS5A recombinant30 with the corresponding JFH1 sequence. Mutations were introduced by QuikChange site-directed mutagenesis kit (Agilent) or by fusion PCR. The HCV sequences of final plasmid preparations were confirmed by Sanger sequencing (Macrogen). The nucleotide and amino acid (aa) numbers refer to the ED43 full-length recombinant sequence.

Production and analysis of culture viruses

Viability of HCV recombinants was tested by transfection of RNA transcripts into Huh7.5 cells using Lipofectamine 2000 (ThermoFisher).26 Cells were subcultured every 2–3 days and viral passage was performed as described.3 Harvested cellular pellets were centrifuged at 2000 rpm for 5 min, washed 2–3 times with sterile phosphate buffered saline (PBS) (Sigma-Aldrich) and stored in 1 mL of Trizol (ThermoFisher). Infectivity titres were determined in triplicate and reported as log10 focus-forming units per milliliter (log10FFU/mL).24

Genome analysis of recovered viruses

Next-generation sequencing (NGS) was performed as described.3 31–33 Briefly, RNA was extracted, and reverse transcription (RT)-PCR performed to obtain complete HCV open reading frame (ORF) amplicons.33 For RT, primer 5’-CTAAGGTCGGAGTGTTAAGC-3’, and for PCR, primers 5’-TGCCTGATAGGGTGCTTGCG-3’ and 5’-AGGTCGGAGTGTTAAGCTGCC-3’ were used. PCR amplicons were processed with NEBNext Ultra II FS DNA Library Prep Kit (New England Biolabs). In order to sequence up to 500 bp to cover NS3P, NS5A domain I or the NS5B-palm domain (up to 167 aa), we performed size selection. Sequencing was carried out in-house by Illumina Miseq using 500 cycles v2 kit. Data were analysed for single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP).31 32 The linkage analysis was done with LinkGE on coding SNPs with frequencies ≥2%.31 32 The haplotypes were reconstructed and plotted using GraphPad Prism version 6.

For ORF analysis, the linkage and haplotype reconstruction could not be applied in one read pair. Therefore, the frequency development of SNP variants over time was used. For specific samples, PCR amplicons were subcloned into TOPO-XL2 vector (ThemoFisher), allowing ORF linkage analyses. Each clone was sequenced by Sanger and aligned to build phylogeny and ancestral reconstruction.31

For ED43(C5A) recombinants, recovered viruses were analysed by Sanger.3 For viral 5’UTR sequences, we used a 5’RACE procedure on culture supernatants.3 26 The PCR products were analysed by Sanger.3

Virus stocks and treatment assays

Inhibitors (Acme Bioscience) were diluted in dimethyl sulfoxide.3 4 27 34 Escape and treatment assays were conducted using the 5th, 7th and 10th passages of ED43-20m (figure 1A, B), and not the final ED43cc virus, in order to optimise the timing of the different experiments. For the reverse-genetic testing of RAS, the ED43-31m/+A1973T/-Q2931R (named ED43-31m_opt) recombinant was used (figure 1A).

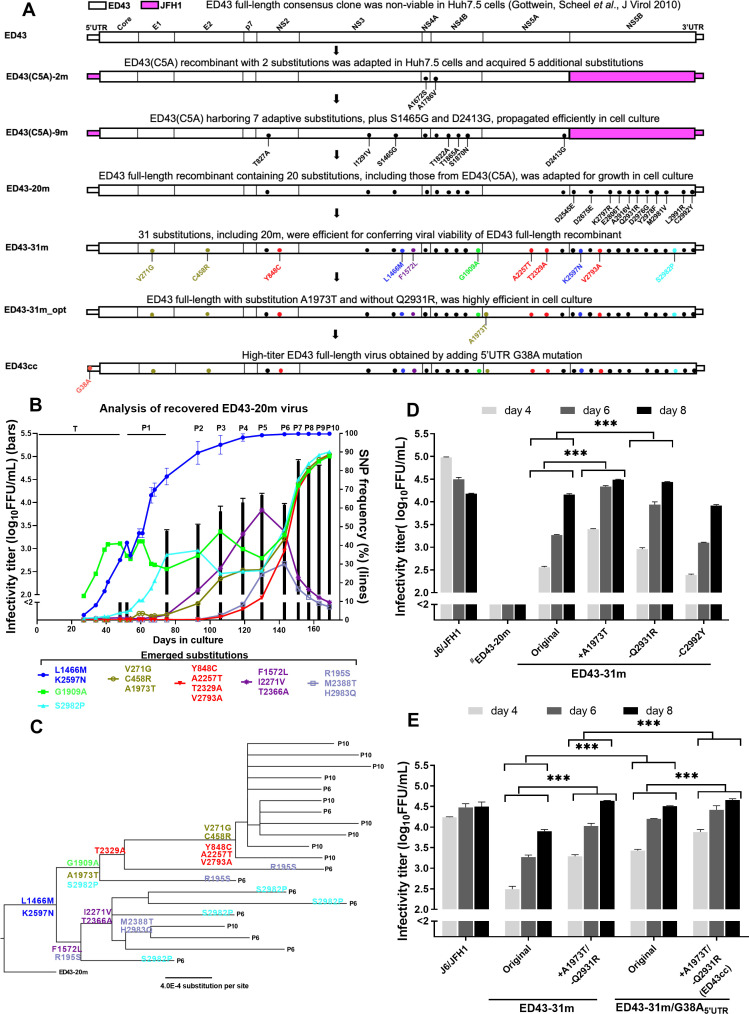

Figure 1.

Full-length HCV genotype 4a infectious cell-culture system. (A) Schematic overview of the culture adaptation process of strain ED43. Substitutions introduced into the full-length recombinant ED43-20m are shown in black. Adaptive substitutions identified during passage of the ED43-20m virus are indicated by colours from panels B and C. (B) HCV infectivity (bars) determined by FFU assays and shown by mean of triplicates±SEM (left y-axis; break indicates the cut-off of the assay), and emergence of substitutions for ED43-20m (lines) during adaptation following transfection (T; samples not available from days 0 to 27) and serial passages (P1, 2, 3, etc.). Only substitutions with SNP frequencies >20% at any time-point are shown (right y-axis). For substitutions that emerged with similar patterns, means±SEM are shown. The substitutions with similar SNP frequencies are grouped and shown with the same colour. (C) Clonal ORF sequence analysis of ED43-20m virus obtained from the 6th and 10th passages; phylogeny was generated as described.31 Subsequently, ancestral reconstruction was performed based on alignment and phylogeny to predict the appearance of respective substitutions. Only substitutions indicated in (B) are shown. (D, E) Infectivity titres (y-axis) of specific ED43 recombinant viruses at indicated days (x-axis) after transfection of Huh7.5 cells. J6/JFH1 was included as a control. #The data were obtained from a separate experiment with similar J6/JFH1 titres. Statistical significance (p<0001, two-way ANOVA) is carried out for indicated samples and shown with asterisks (***). ANOVA, analysis of variance; FFU, focus-forming unit; ORF, open reading frame; SNP, single nucleotide polymorphism; SEM, standard error of the mean.

gutjnl-2020-323585supp001.pdf (8.4MB, pdf)

Treatments were initiated upon virus spread (≥90% HCV antigen-positive cells) and the inhibitors were added every 2–3 days when cells were subcultured.3 For concentration-response assays using described methods,3 4 27 stocks of nontreated and of single-treatment escape viruses were prepared. To prepare virus stocks from escape viruses, supernatants recovered from the treatment experiments were used to infect naïve Huh7.5 cells that were then cultured without inhibitors until virus spread. Sequences of virus stocks were confirmed by NGS. The half-maximal effective concentration (EC50) value was calculated using GraphPad Prism version 6.

For combination treatments with indicated DAA concentrations, escape stock viruses were used to infect naïve Huh7.5 cells and followed until virus spread.3 Viral supernatants were collected at treatment initiation (day 0) and frequently hereafter, and HCV sequences were confirmed by NGS. Unless otherwise stated, the viruses were treated 28–30 days. Afterwards, cultures were followed without drugs for 14 days3; infection was defined as eradicated, if no HCV antigen-positive cells were detected.3 4

Results

Development of HCV genotype 4a full-length infectious cell-culture systems

Like most prototype HCV clones, the full-length clone of genotype 4a prototype strain ED43 (pED43) is infectious in chimpanzees, but not in Huh7.5 cells.10 Therefore, we aimed at identifying adaptive substitutions permitting culture of this full-length clone. It has been reported that the JFH1-NS5B has high replication activity in cell culture.35 36 Taking advantage of this, we showed that for various genotypes, cell culture adaptation of recombinants with genotype-specific Core-NS5A (C5A), JFH1-NS5B, and JFH1-UTRs resulted in identification of mutations that permitted replication of the corresponding full-length genome.21 Thus, we first generated JFH1-based ED43-C5A recombinants for this same purpose.

Culture-efficient ED43(C5A)-adapted recombinant

RNA transcripts from ED43(C5A)-clones with or without A1672S(NS4A), required for culture of genotypes 1a, 2a and 2b strains,24–27 yielded no HCV antigen-positive Huh7.5 cells during 30 days of follow-up. However, ED43(C5A)-2 m (figure 1A) with A1786V(NS4B), previously used for adaptation of the ED43 5’UTR-NS5A recombinant,30 and A1672S(NS4A) spread at day 52 (4.0 log10FFU/mL) and acquired five additional substitutions (online supplemental table 1), which were added into ED43(C5A)-2 m. The resulting ED43(C5A)-7 m spread at day 11 post-transfection yielding 4.1 log10FFU/mL in second passage. Adding two previously identified substitutions,3 4 25 led to ED43(C5A)-9 m (figure 1A and online supplemental table 1) spreading at day 6 post-transfection, producing 4.2 log10FFU/mL in second passage (online supplemental table 1).

Development of high titre culture-infectious-ED43 full-length recombinants

For adaptation of pED43,10 we generated recombinants harbouring nine substitutions from ED43(C5A)-9 m, and 6 NS5B substitutions (A499V, Q514R, D559G, Y561F, L574R, C575Y), previously used for culture adaptation of genotypes 1a, 2a, 2b, 3a and 6a (figure 1A).21 In addition to these 15 changes, we used additional NS5B substitutions and produced two different recombinants: one with 3 NS5B changes (D128E, D258E, and M564V; ED43-18m) or with 5 NS5B changes (adding K380R and E389T creating ED43-20m) (figure 1A). These NS5B changes were selected based on the comparative analysis of polymerase sequences from ED43 and other strains for which infectious cultures were developed. This analysis led to the identification of conserved residues that were different in ED43, which we hypothesised might be important for viral viability in cell culture (online supplemental figure 1A). Following transfection, ED43-18m was nonviable, but ED43-20m spread at day 41 (2.6 log10FFU/mL). The infectivity titres increased during consecutive passages, reaching ~5.0 log10 FFU/mL at passage 10 (figure 1B and table 1).

Table 1.

Non-synonymous ORF mutations in ED43 recombinant viruses during culture adaptation

| ED43 | H77 | SNP frequencies (%) | ||||||||||

| ED43-20m | ED43-31m | ED43-31m_opt | ED43cc* | |||||||||

| HCV gene | NT pos | NT change | AA pos | AA change | AA pos | 4.1† (4th, 13) | 5.0† (10th, 6) |

4.3† (2nd, 8) |

5.1† (2nd, 6) |

5.1† (2nd, 6) |

||

| E1 | 923 | C | A | 195 | R | S | 195 | 7.1 | 6,9 | – | – | – |

| E1 | 1152 | T | G | 271 | V | G | 271 | 28.1 | 89.1 | 99.9 | 100 | 100 |

| E2 | 1553 | T | C | 405 | S | P | 405 | 7.2 | – | – | ||

| E2 | 1712 | T | C | 458 | C | R | 458 | 26.2 | 88.9 | 99.9 | 100 | 100 |

| E2 | 2534 | T | C | 732 | S | P | 732 | 8.6 | – | – | – | – |

| p7 | 2597 | A | G | 753 | N | D | 753 | 16.8 | – | – | – | – |

| p7 | 2646 | T | C | 769 | I | T | 769 | 10.2 | – | – | – | – |

| p7 | 2730 | T | C | 797 | F | S | 797 | 11.5 | – | – | – | – |

| NS2 | 2819 | A | G | 827 | T | A | 827 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| NS2 | 2883 | A | G | 848 | Y | C | 848 | 6.5 | 88.2 | 99.6 | 100 | 100 |

| NS3 | 3710 | A | G | 1124 | T | A | 1124 | – | 11,3 | – | – | – |

| NS3 | 4211 | A | G | 1291 | I | V | 1291 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| NS3 | 4487 | G | A | 1383 | E | K | 1383 | 11.7 | – | – | – | – |

| NS3 | 4733 | A | G | 1465 | S | G | 1465 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| NS3 | 4736 | T | A | 1466 | L | M | 1466 | 99.8 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| NS3 | 5054 | T | C | 1572 | F | L | 1572 | 45.8 | 9.8 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| NS4A | 5354 | G | T | 1672 | A | S | 1672 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| NS4B | 5697 | C | T | 1786 | A | V | 1786 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| NS4B | 5804 | A | G | 1822 | T | A | 1822 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| NS4B | 5933 | A | G | 1865 | T | A | 1865 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| NS4B | 5949 | G | A | 1870 | S | N | 1870 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| NS4B | 6066 | G | C | 1909 | G | A | 1909 | 38.0 | 87.8 | 99.9 | 100 | 100 |

| NS5A | 6257 | G | A | 1973 | A | T | 1973 | 25.8 | 88.4 | – | 100 | 100 |

| NS5A | 7017 | T | C | 2226 | L | P | 2226 | 7.7 | – | – | – | – |

| NS5A | 7109 | G | A | 2257 | A | T | 2261 | 5.3 | 88.4 | 99.9 | 100 | 100 |

| NS5A | 7126 | C | A | 2262 | D | E | 2265 | 17.8 | – | – | – | – |

| NS5A | 7151 | A | G | 2271 | I | V | 2274 | 46.7 | 9.6 | – | – | – |

| NS5A | 7325 | A | G | 2329 | T | A | 2332 | 5.4 | 88.4 | 99.5 | 100 | 100 |

| NS5A | 7436 | A | G | 2366 | T | A | 2369 | 45.9 | 9.0 | – | – | – |

| NS5A | 7503 | T | C | 2388 | M | T | 2388 | 11.2 | 7.3 | – | – | – |

| NS5A | 7578 | A | G | 2413 | D | G | 2416 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| NS5B | 7975 | C | A | 2545 | D | E | 2548 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| NS5B | 7979 | A | G | 2547 | N | D | 2550 | 11.8 | – | – | – | – |

| NS5B | 8033 | A | G | 2565 | N | D | 2568 | 5.9 | – | – | – | – |

| NS5B | 8131 | A | T | 2597 | K | N | 2600 | 95.8 | 99.7 | 99.8 | 100 | 100 |

| NS5B | 8134 | A | C | 2598 | K | N | 2601 | 8.6 | – | – | – | – |

| NS5B | 8365 | T | G | 2675 | D | E | 2678 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| NS5B | 8718 | T | C | 2793 | V | A | 2796 | 6.1 | 88.4 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| NS5B | 8730 | A | G | 2797 | K | R | 2800 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| NS5B | 8756 | G | A | 2806 | E | T | 2809 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| NS5B | 8757 | A | C | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | ||||

| NS5B | 9087 | C | T | 2916 | A | V | 2919 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| NS5B | 9132 | A | G | 2931 | Q | R | 2934 | 98.1 | 97.3 | 100 | -‡ | -‡ |

| NS5B | 9267 | A | G | 2976 | D | G | 2979 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| NS5B | 9273 | A | T | 2978 | Y | F | 2981 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| NS5B | 9281 | A | G | 2981 | M | V | 2984 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| NS5B | 9284 | T | C | 2982 | S | P | 2985 | 26.0 | 90.1 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| NS5B | 9289 | T | G | 2983 | H | Q | 2986 | 6.3 | 7.0 | – | – | – |

| NS5B | 9312 | T | G | 2991 | L | R | 2994 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| NS5B | 9315 | G | A | 2992 | C | Y | 2995 | 99.3 | 99.1 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

Only mutations with a frequency of >5% of the viral population in NGS analysis are shown. Shaded background indicates frequencies of engineered mutations.

*Nucleotide G at position 38 in 5’UTR was changed to A.

†HCV infectivity titres at indicated passage and day (parentheses) are shown as log10FFU/mL.

‡These recombinant viruses had A at position 9132 instead of G, and this nt was maintained.

AA, amino acid; NGS, next-generation sequencing; NT, nucleotide; NT pos and AA pos, nucleotide and amino acid positions; SNP, single nucleotide polymorphism.

To identify substitutions evolving during serial passage of ED43-20m in Huh7.5 cells, we analysed extracellular viral RNAs using NGS. The substitutions that emerged with similar patterns were grouped as shown in figure 1B. L1466M(NS3) and K2597N(NS5B) were found in >80% of the viral population at second passage (figure 1B). However, the fitness of a recombinant with these substitutions (ED43-22m) remained low and the virus acquired additional changes (online supplemental figure 2). Thus, we investigated other substitution patterns (figure 1B). As shown in figure 1B, two different viral populations evolved that showed relatively equal prevalence in passage 6. However, one population became dominant in passage 10. The stepwise acquisition of substitutions was confirmed by further analysis of 6th and 10th passage viruses (figure 1C), by Sanger sequencing analysis of TA clones of amplicons. Clones were analysed by linkage and ancestral reconstruction based on phylogeny. L1466M and K2597N were observed in all clones, followed by the emergence of two different viral populations. Interestingly, we found that the mutation patterns were similar between cell-free and cell-associated viruses (figure 1B and online supplemental figure 3).

Based on the evolution during ED43-20m adaptation, we constructed a recombinant harbouring all dominant 10th passage substitutions, except for A1973T(NS5A) (figure 1A, B). We also introduced F1572L, detected in the ED43(C5A)-7 m recovered virus and emerging during the first five passages of ED43-20m (figure 1A, B and online supplemental table 1). The resulting ED43-31m spread fast and produced ~4.3 log10 FFU/mL (figure 1A, D). We did not detect other substitutions at >5% of the viral population in the second passage (table 1). However, the titres of this virus did not match those observed at passage 10 of ED43-20m, and thus there was room for further optimisation.

Among the original 20 m substitutions, Q2931R and C2992Y had partly reverted (table 1), and R2931Q was found to increase ED43-31m titres after transfection (figure 1D). In addition, titres of ED43-31m further increased after introducing A1973T(NS5A) (detected in the ED43-20m 10th passage virus but not initially included in ED43-31m) (figure 1D). Thus, we generated an ED43-31m recombinant containing A1973T and the reversion of Q2931R (ED43-31m/+A1973T/-Q2931R; or ED43-31m_opt), which showed fast spread kinetics and slightly higher ~4.6 log10 FFU/mL post-transfection titres (figure 1E).

Finally, we found that a recombinant carrying the G38A mutation in the 5’UTR (ED43-31m_opt with 5’UTR G38A, designated ED43cc, GenBank accession: MW531222), which was detected in the 10th passage of ED43-20m, produced the highest titres mimicking the ED43-20m virus 10th passage, ~4.7 and 5.1 log10 FFU/mL in transfection and second passage, respectively. We did not detect additional substitutions emerging at >5% of the viral population in the second passage virus (table 1).

Overall, we revealed unique evolutionary details on HCV culture adaptation and developed full-length 4a recombinants that propagated robustly in Huh7.5 cells. The ED43cc harboured 32 changes compared with the consensus ED43 clone, including 5, 4 and 13 coding changes in NS3/4A, NS5A and NS5B, respectively (online supplemental figure 1B).

HCV evolutionary genetic networks resulting in DAA-resistance for genotype 4a

The recommended DAA-based regimens for patients with chronic genotype 4 infection include NS3 protease (grazoprevir, paritaprevir and glecaprevir), NS5A (elbasvir, ledipasvir, ombitasvir, velpatasvir and pibrentasvir) and NS5B polymerase (sofosbuvir) inhibitors.11 13 The evolutionary features underlying the emergence of viral resistance are not well characterised. The HCV genotype 4a infectious culture system can serve as a valuable model to explore determinants of virus escape from DAAs. We, thus, performed NGS and linkage analysis permitting detailed investigation of emerging RASs during culture escape experiments and examined the evolution of putative fitness compensating substitutions throughout the HCV genome using reverse genetics.3 31 32

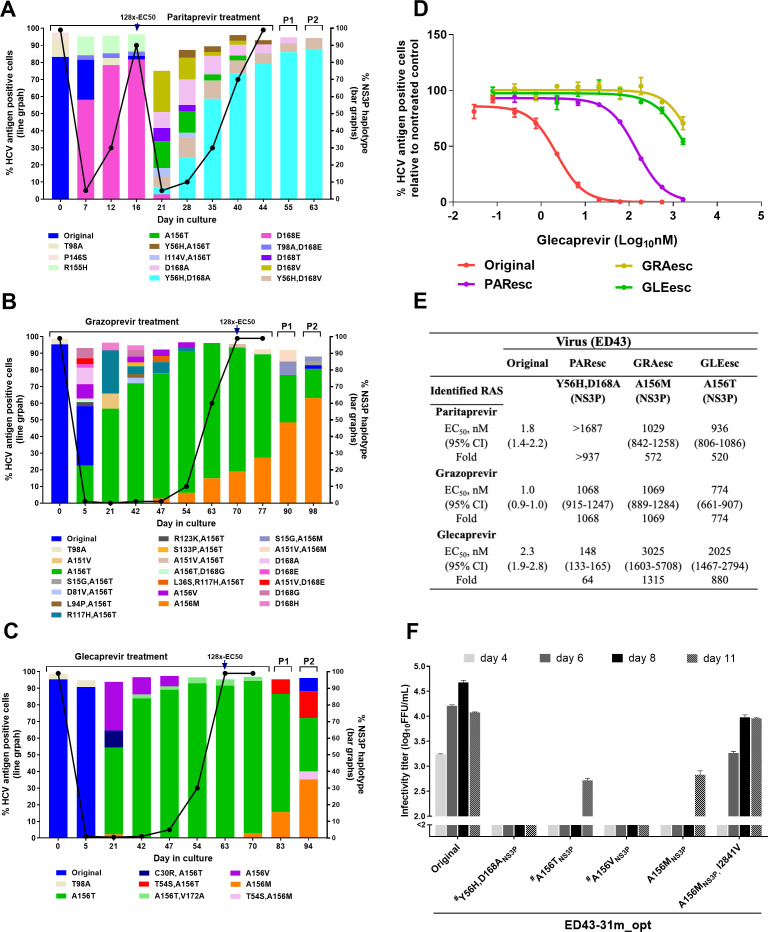

Evolutionary pathways underlying emergence of RASs during treatments with protease inhibitors

To induce viral escape from protease inhibitors (PIs), we performed long-term treatments of the ED43 virus with paritaprevir, grazoprevir or glecaprevir at concentrations equivalent to 8xEC50 31 32 (figure 2A–C). For paritaprevir, NS3P-D168E emerged at day 7 after treatment initiation and became a major RAS when the virus escaped at day 16. Under a higher inhibitor concentration (128xEC50), D168E decreased in prevalence and different RASs singly or in combination emerged. Y56H+D168A appeared at low frequency at day 21 but became dominant following viral escape. The escape virus (PAResc) showed cross-resistance to all tested PIs compared with the original virus with ≥64-fold increase in EC50 (figure 2E; online supplemental figure 4). However, an ED43 recombinant harbouring Y56H+D168A was highly attenuated (figure 2F) and engineered RASs reverted after a second drug-free passage (table 2). Therefore, compensatory substitutions might be required for stability of these RASs, which were maintained during second passage of the escape virus (figure 2A). NGS analysis of the complete viral ORF during treatment showed complex patterns of substitutions (online supplemental figure 5A). T1566S[NS3-helicase (NS3H)] and K2317T(NS5A) emerged together with Y56H/D168A, suggesting linkage (online supplemental figure 5A). In addition, Q1552L(NS3H) and V1656M(NS3H) evolved in drug-free passages suggesting a role in viral fitness (online supplemental figure 5A).

Figure 2.

Substitution networks emerging in NS3P domain under protease inhibitor treatments. (A–C) ED43 full-length cultures were treated with protease inhibitors paritaprevir (A), grazoprevir (B) and glecaprevir (C) and analysed by NGS. The percentage of HCV-antigen positive cells was determined by immunostaining (line graph, left y-axis). The distribution of haplotypes (bar graphs, right y-axis) was determined by linkage analysis and indicated by different colours. Treatments were initiated with concentrations equivalent to 8x-EC50, then concentrations were increased to 128x-EC50 at day 16 (paritaprevir), 70 (grazoprevir) and 63 (glecaprevir). Only haplotypes constituting ≥2% of the viral population are shown. Supernatant samples from the last treatment time-points were used for passage. P1 and P2: the first and second passages. (D) Efficacy of glecaprevir against indicated ED43 full-length DAA escape viruses. Values are means of triplicates±SEM. (E) EC50 values and 95% CI of indicated escape viruses were calculated from data shown in (D) and online supplemental figure 4. Fold changes in EC50 values were compared with the original ED43. (F) Fitness of ED43 recombinant virus harbouring NS3P RASs. For details, see figure 1D, E legend. The corresponding drug targets and protein-specific numbers are indicated for RASs. Other substitutions are shown with polyprotein specific numbers. #The data were obtained from a separate experiment with similar titres of the original virus. NGS, next-generation sequencing; RAS, resistance-associated substitution; SEM, standard error of the mean.

Table 2.

NGS analysis of recombinant ED43 viruses harbouring RASs recovered from the second passage culture

| HCV gene | Polyprotein | P# | SNP frequencies (%) | NS5B* | ||||||||||||||

| NS3* | NS5A* | |||||||||||||||||

| NT pos | NT change | AA pos | AA change | AA pos | Y56H, D168A | A156M | A156M, I2841V | L28V | L30P, Y93H | L30H, M31V | L28M, L30F, M31V | L30Ơ | L30Ơ, T2047I | S282T | S282T, A1309P | |||

| NS3 | 3584 | T | C | 1082 | Y | H | 56 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| NS3 | 3884 | G | A | 1182 | A | M | 156 | – | 99.6 | 99.8 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| NS3 | 3885 | C | T | – | 99.6 | 99.7 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | ||||

| NS3 | 3921 | A | C | 1194 | D | A | 168 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| NS3 | 4265 | G | C | 1309 | A | P | 283 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 99.8 |

| NS3 | 5268 | A | G | 1643 | K | R | 617 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 13.9 | – | – | – |

| NS4B | 5645 | A | G | 1769 | I | V | 58 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 27.5 | – | – | – |

| NS5A | 6338 | C | G | 2000 | L | V | 28 | – | – | – | 99.6 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| NS5A | 6338 | C | A | 2000 | L | M | 28 | – | – | – | – | – | – | 99.9 | – | – | – | – |

| NS5A | 6339 | T | C | 2000 | L | P | 28 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 7.2 | – | – | – |

| NS5A | 6344 | C | T | 2002 | L | F | 30 | – | – | – | – | – | – | 99.8 | – | – | – | – |

| NS5A | 6344 | CTC | del‡ | 2002 | L | del‡ | 30 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 97.0 | 97.0 | – | – |

| NS5A | 6345 | T | C | 2002 | L | P | 30 | – | – | – | – | 99.5 | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| NS5A | 6345 | T | A | 2002 | L | H | 30 | – | – | – | – | – | 99.6 | – | – | – | – | – |

| NS5A | 6347 | A | G | 2003 | M | V | 31 | – | – | – | – | – | 99.8 | 99.9 | – | – | – | – |

| NS5A | 6480 | C | T | 2047 | T | I | 75 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 7.1 | 99.8 | – | – |

| NS5A | 6510 | A | G | 2057 | H | R | 85 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 5.6 | – | – |

| NS5A | 6533 | T | C | 2065 | Y | H | 93 | – | – | – | – | 99.5 | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| NS5A | 6637 | C | A | 2099 | F | L | 127 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 8.6 | – | – | – |

| NS5A | 6737 | C | T | 2133 | H | Y | 161 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 23.7 | – | – | – |

| NS5A | 7266 | A | T | 2309 | H | L | 337 | 97.2 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| NS5A | 7578 | G | A | 2413 | G | D | 441 | – | 5.5 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| NS5B | 8406 | A | G | 2689 | D | G | 272 | – | 5.3 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| NS5B | 8435 | A | T§ | 2699 | S | C | 282 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 16.9§ | – |

| NS5B | 8436 | G | C | 2699 | S | T | 282 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 97.4 | 99.6 |

| NS5B | 8861 | A | G | 2841 | I | V | 424 | – | 57.2 | 99.9 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

All recombinant viruses harbouring RASs were generated using the ED43-31m_opt backbone as shown in figures 2–4. Shaded background indicates frequencies of mutations that were introduced into this recombinant. Only non-synonymous (coding) mutations that represented >5% of the viral population are shown.

*Target proteins in which the recombinants harbouring RASs were numbered.

†This recombinant had a deletion at NS5A position 30.

‡Three nucleotides were deleted, resulting in an amino acid deletion.

§The linkage analysis showed that this nucleotide was combined with C at position 8436, resulting in the reversion of S282T with a frequency of 16.9%. Therefore, the actual frequency of S282T was ~80%.

AA, amino acid; NGS, next-generation sequencing; NT, nucleotide; NT pos and AA pos, nucleotide and amino acid positions; P#, protein specific numbers; RAS, resistance-associated substitution; SNP, single nucleotide polymorphism.

Similarly, we investigated patterns of RASs under grazoprevir and glecaprevir treatments. After treatment initiation, different RASs developed, including A156T/V (figure 2B, C). However, viral spread did not occur until after day 53, even though A156T emerged to >50% by day 21. Viral escape was associated with T156 being replaced by M156. The grazoprevir (GRAesc) and glecaprevir (GLEesc) escape viruses were highly resistant to PIs with >500-fold increases in EC50 (figure 2D, E; online supplemental figure 4). However, ED43 recombinants harbouring engineered A156T/V/M were highly attenuated (figure 2F), and the A156T/V reverted after transfection.31 A156M was maintained, but the virus acquired additional coding ORF changes, including I2841V(NS5B;>50%), G2413D(NS5A;>5%) and D2689G(NS5B;>5%), in second passage (table 2). Furthermore, during inhibitor treatments, we found complex dynamic networks of substitutions outside NS3P (online supplemental figure 5B, C). We detected I2841V, seen in the recombinant A156M virus, at 5% frequency in the GRAesc virus second passage. Interestingly, the A156M recombinant virus harbouring I2841V was efficient and genetically stable (figure 2F and table 2).

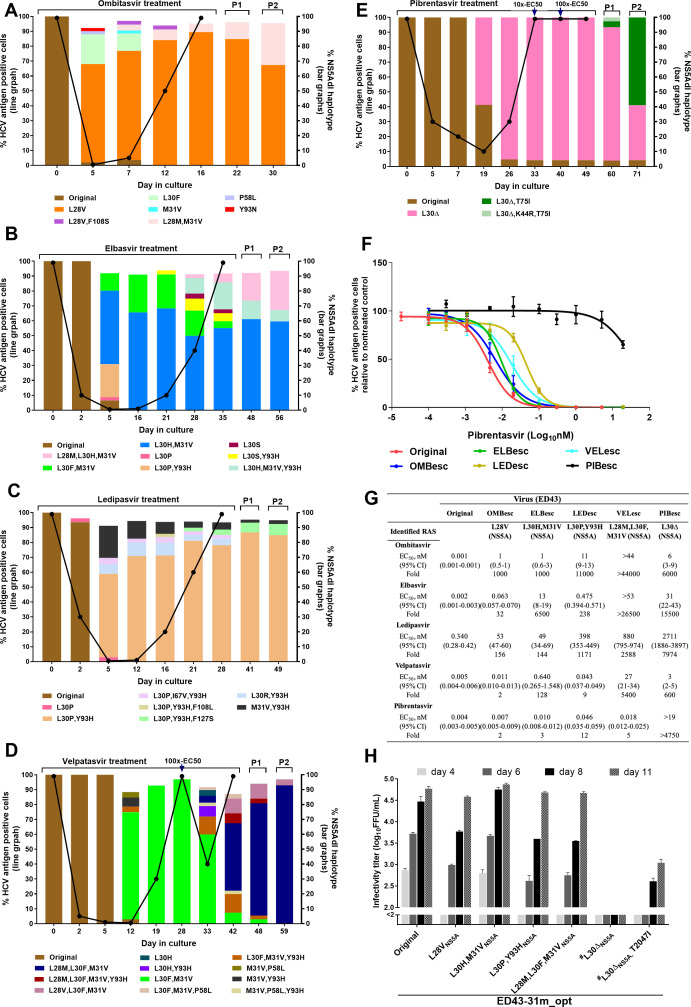

Evolution induced by NS5A inhibitors

Under ombitasvir, elbasvir and ledipasvir treatments (concentrations equivalent to 100xEC50), the main RASs responsible for ED43 escape emerged at day 5 (figure 3A–C).3 Following viral escape from ombitasvir (OMBesc), elbasvir (ELBesc), and ledipasvir (LEDesc), RASs conferring high-level resistance (figure 3G and online supplemental figure 6) became dominant (figure 3A–C). The main NS5A RASs L28V (ombitasvir), L30H+M31V (elbasvir) and L30P+Y93H (ledipasvir) did not result in a high loss of fitness when introduced in the ED43 recombinant and were maintained after second passage (figure 3H and table 2).

Figure 3.

Substitution networks emerging in NS5A domain I under treatments with NS5A inhibitors. (A–E) ED43 full-length cultures were treated with ombitasvir (A), elbasvir (B), ledipasvir (C), velpatasvir (D) and pibrentasvir (E). (A–C): Inhibitor concentration: 100x-EC50. (D) Initial concentration: 10x-EC50; increased to 100x-EC50 at day 28. (E) Treatment initiated at 5x-EC50, then increased to 10x- and 100x-EC50 at days 33 and 40, respectively. (F) Efficacy of pibrentasvir against ED43 full-length DAA escape viruses. Values are means of triplicates±SEM. (G) EC50 values and 95% CI of indicated escape viruses were calculated from data shown in (F) and online supplemental figure 6. (H) Fitness of ED43 recombinant viruses harbouring NS5A RASs. #The data were obtained from the experiment shown in figure 2F. For details, see figure 2 legend. RAS, resistance-associated substitution; SEM, standard error of the mean.

For velpatasvir, we did not observe viral escape with 100xEC50 and performed an experiment at 10xEC50. The major RASs of L30F+M31V were not acquired as rapidly as for ombitasvir, elbasvir and ledipasvir, suggesting higher barrier to resistance (figure 3D). These RASs were dominant in escape viruses until day 28. Here, the concentration was increased to 100xEC50, resulting in diversification of the viral population, associated with increased viral suppression (figure 3D). L28M+L30F+M31V emerged as a major population, which led to viral escape (VELesc) and high resistance levels to NS5A inhibitors (except pibrentasvir) (figure 3F, G and online supplemental figure 6). The ED43 L28M+L30F+M31V recombinant was highly fit and maintained the RASs after second passage (figure 3H and table 2).

Genome-wide NGS showed that substitutions outside NS5A-domain I emerged in viruses escaping ombitasvir, elbasvir, ledipasvir and velpatasvir (online supplemental figure 7A–D).

Pibrentasvir 10xEC50 treatment resulted in viral eradication. However, 5xEC50 treatment led to escape by day 33 (figure 3E). Interestingly, we primarily observed NS5A RAS L30Δ (deletion) (figure 3E), and no viral suppression was observed at increased concentrations (10xEC50 and 100xEC50), indicating that L30Δ conferred high resistance. Indeed, the escape virus (PIBesc) showed high levels of resistance to all NS5A inhibitors (figure 3F, G and online supplemental figure 6). In contrast to other NS5A-RASs, the ED43-L30Δ recombinant was highly attenuated and acquired additional substitutions after second passage (figure 3H; table 2). One of these substitutions, T2047I (T75I, NS5A-numbering), also found in the second drug-free passage of PIBesc, increased fitness of the L30Δ recombinant (figure 3E, H and online supplemental figure 7E).

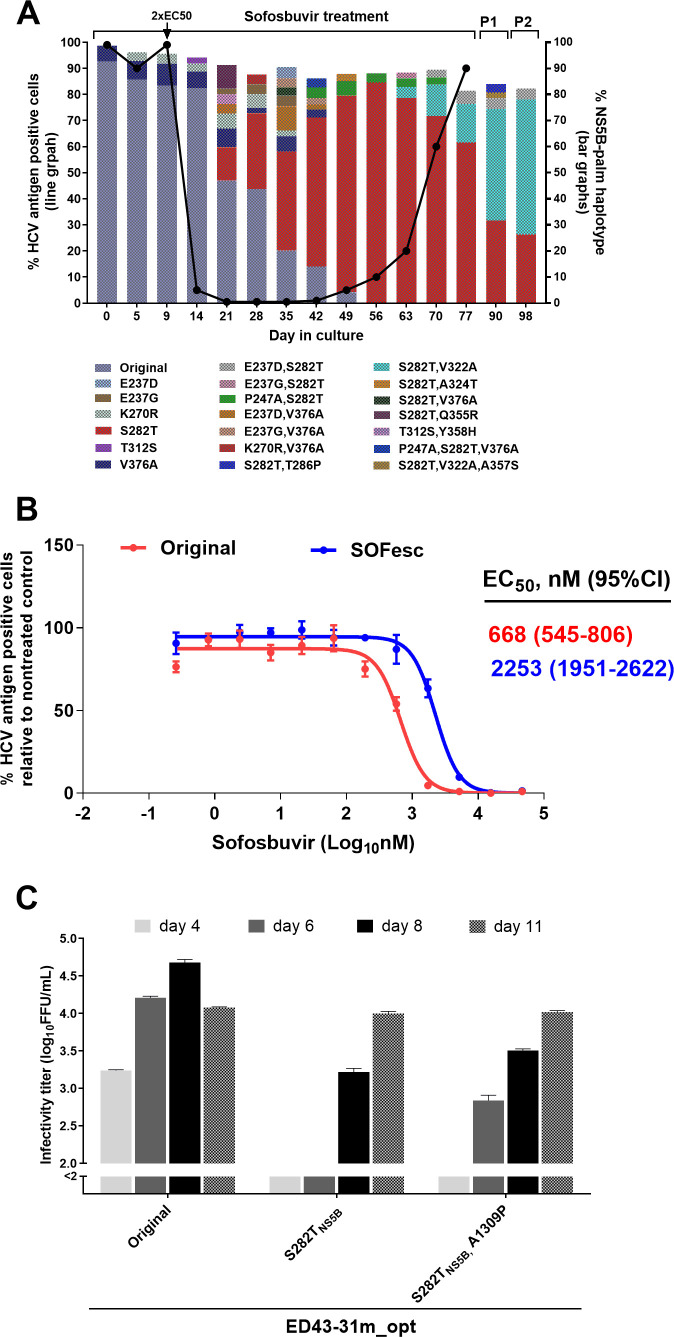

Evolution induced by sofosbuvir

The ED43 virus treated with sofosbuvir was initially suppressed at 2xEC50 but escaped at day 77 (figure 4A). NGS analysis of HCV-ORF during treatment highlighted a complex network of coselection of substitutions underlying the gradual emergence of single NS5B-RAS S282T (online supplemental figure 8), coexisting with S282T+V322A (figure 4A). Interestingly, the S282T+V322A population increased during drug-free passages (figure 4A). The SOFesc virus had decreased sensitivity to sofosbuvir (figure 4B). Strikingly, the ED43 recombinants harbouring engineered S282T with or without A1309P(NS3H), which developed following the emergence of S282T (online supplemental figure 8), were relatively fit (figure 4C) and S282T was maintained after two consecutive drug-free passages (table 2).

Figure 4.

Substitution networks emerging in NS5B-palm domain under sofosbuvir treatment. (A) ED43 full-length cultures were treated with sofosbuvir and analysed by NGS. Treatment was initiated with 1x-EC50, then increased to 2x-EC50 at day 9. (B) Efficacy of sofosbuvir against indicated ED43 full-length DAA escape viruses. Values are means of triplicates±SEM. (C) Fitness of ED43 recombinant viruses harbouring RAS NS5B-S282T. For details, see figure 2 legend. NGS, next-generation sequencing; SEM, standard error of the mean.

Efficacy of clinically relevant DAA combinations against genotype 4a

Recommended DAA combinations include paritaprevir/ombitasvir, grazoprevir/elbasvir, ledipasvir/sofosbuvir, velpatasvir/sofosbuvir and glecaprevir/pibrentasvir.11 13 These regimens were efficient in suppressing the original ED43 virus (figures 5 and 6). Except for treatment with LED(5xEC50)/SOF(1xEC50), where we consistently detected HCV-positive cells, the original virus was eradicated in all treatments. Next, we tested whether DAA combinations remained efficient against their corresponding single drug escape ED43 variants.

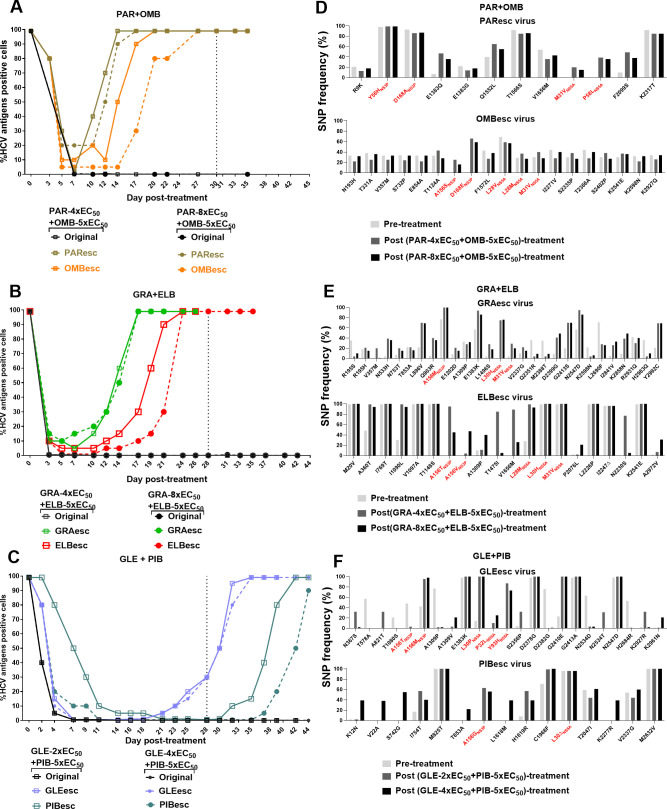

Figure 5.

Efficacy of DAA combinations containing PIs and NS5A inhibitors against ED43 escape viruses. (A–C) For each DAA combination, concentrations of 5x-EC50 of NS5A inhibitors were used in combination with either 2x-, 4x- or 8x-EC50 of corresponding PIs. Black dashed lines indicate the time when the treatments were stopped. (D–F) NGS analysis of complete ORF sequences of viruses that escaped from DAA combinations. Only SNP of non-synonymous mutations with frequencies>20% in pre- and/or post-treatments are shown. These SNPs showed a frequency of <20% in the original virus that underwent treatments with single inhibitors (online supplemental figures 5 and 7). The putative RASs are shown in red. The corresponding drug targets and protein specific numbers are indicated for RASs. NGS, next-generation sequencing; ORF, open reading frame; PIs, protease inhibitors; SNP, single nucleotide polymorphism.

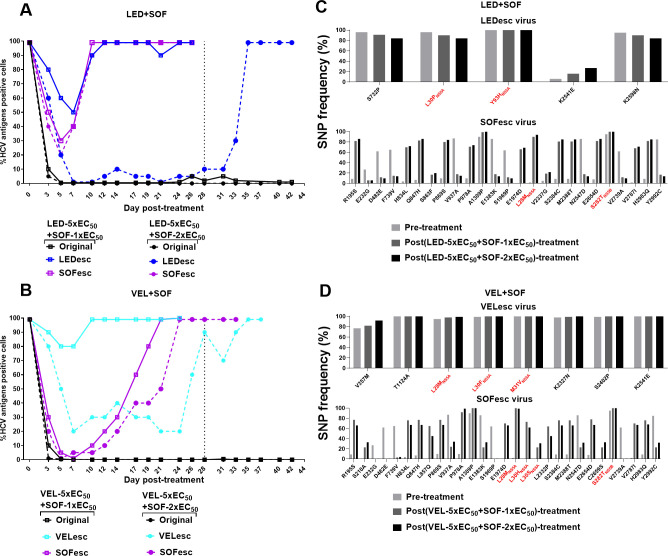

Figure 6.

Efficacy of DAA combinations containing NS5A inhibitors and sofosbuvir against ED43 escape viruses. (A, B) For each DAA combination, concentrations of 5x-EC50 of NS5A inhibitors were used in combination with either 1x- or 2x-EC50 of sofosbuvir. (C, D) NGS analysis of complete ORF sequences of viruses after combination treatments. For details, see figure 5 legend. NGS, next-generation sequencing; ORF, open reading frame.

DAA regimens based on PIs (paritaprevir, grazoprevir or glecaprevir) and NS5A inhibitors (ombitasvir, elbasvir or pibrentasvir) were inefficient against viruses that had escaped one of the included drugs, and thus harboured RASs at baseline (figure 5A–C).3 4 31 Only glecaprevir/pibrentasvir was able to control the GLEesc and PIBesc viral infections during treatment (figure 5C). In contrast, paritaprevir/ombitasvir and grazoprevir/elbasvir combinations were inefficient to suppress infections with PI or NS5A-resistant viruses (figure 5A, B), which escaped after 2 weeks of treatment.

NGS and linkage analysis of viruses escaping from these combination treatments showed that in addition to the RAS at baseline, they all acquired RASs in the new target (figure 5D–F and online supplemental figure 9). Moreover, additional substitutions outside the drug targets emerged after combination treatments (figure 5D–F). Particularly, I2841V emerged in the GRAesc virus containing NS3P-A156M.

Similarly, we tested the DAA combinations of NS5A (ledipasvir or velpatasvir) and NS5B (sofosbuvir) inhibitors against the respective LEDesc, VELesc and SOFesc viruses and found that those viral infections were not eradicated (figure 6A, B). The treatment with velpatasvir/sofosbuvir resulted in high suppression and delayed spread of the SOFesc virus as compared with ledipasvir/sofosbuvir.

After combination treatments, the original LEDesc and VELesc viruses maintained the NS5A RASs (figure 6C, D and online supplemental figure 10). The original SOFesc virus acquired NS5A L28M, L30H and L30S, while maintaining NS5B-S282T, and acquiring additional substitutions throughout the ORF (figure 6C, D).

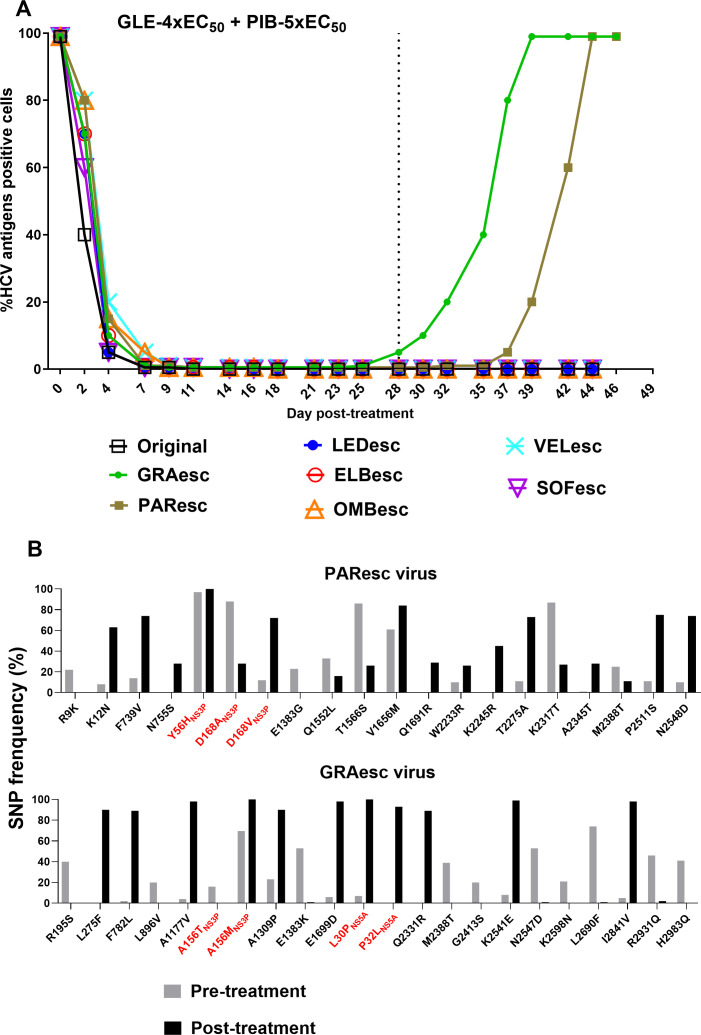

Glecaprevir/pibrentasvir as a retreatment option for HCV genotype 4a with baseline resistance in culture

Our data demonstrated that DAA combinations could not eradicate infections with viruses resistant to one of the included inhibitors. Clinically, glecaprevir/pibrentasvir has been investigated as a retreatment option for HCV-infected patients who failed DAA-containing regimens.37 Thus, we investigated its effectiveness against PAResc, GRAesc, OMBesc, LEDesc, ELBesc, VELesc and SOFesc viruses. Infected cultures were treated with 4xEC50 glecaprevir/5xEC50 pibrentasvir. The infection was suppressed by day 7 of treatment and all except for PAResc and GRAesc viruses were eradicated after 28 days of treatment (figure 7A). NGS analysis of glecaprevir/pibrentasvir escape viruses showed that the GRAesc virus mainly harboured NS3P-A156M (combined with NS3P-A151V) and NS5A-L30P+P32L (figure 7B). The PAResc virus maintained NS3P-Y56H+D168 A/V and acquired NS5A-L30Δ+T75I (as a minor population) (figure 7B and online supplemental figure 11). Among substitutions emerging outside NS3P and NS5A domain I, we also found I2841V(NS5B) in the GRAesc virus (figure 7B). Thus, baseline PI resistance compromised the effectiveness of glecaprevir/pibrentasvir.

Figure 7.

Evaluation of glecaprevir/pibrentasvir as a re-treatment option against ED43 DAA escape viruses. HCV infections (A) and NGS analysis of complete ORF sequences of viruses (B) after treatments with glecaprevir/pibrentasvir. DAA escape viruses that were not eradicated by other investigated DAA combinations, were all treated with glecaprevir/pibrentasvir. Concentrations of 4x-EC50 of glecaprevir in combination with 5x-EC50 of pibrentasvir were used. For details, see figure 5 legend. NGS, next-generation sequencing; ORF, open reading frame.

Discussion

We unravelled viral adaptation leading to the development of a high-titre full-length infectious culture system for HCV genotype 4, a major cause of chronic liver diseases in the Middle East and North/Central Africa. Using cell-culture-adapted ED43(4a) viruses and detailed NGS combined with haplotype reconstruction analysis, we showed that complex networks of RASs and other substitutions outside the drug targets evolved under DAA treatments, which resulted in positive selection of RASs inducing high levels of resistance. We further demonstrated that glecaprevir/pibrentasvir remained efficient as a retreatment option against viruses that had escaped NS5A inhibitors or sofosbuvir, in culture. This is highly relevant, since most genotype 4 patients have been treated with an NS5A inhibitor combined with sofosbuvir.

Recently, an ED43 infectious system was reported by Watanabe et al.29 This system was developed by using substitutions previously identified in ED43 replicons,38 and the final ED43 virus could produce infectivity titres of ~3.5 log10FFU/mL after 39 days of infection.29 Here, we report a different strategy, which is based on the use of substitutions conferring both viral replication and propagation combined with high infectivity titres. Previously, we had succeeded in adapting genotypes 3a and 6a to efficiently grow in culture by initially combining substitutions identified in their corresponding C5A recombinants with changes in NS5B, which consisted of modifications of the sequence to reflect the consensus as compared with other genotypes 3a and 6a sequences, respectively.3 4 However, for the original ED43, the NS5B sequence in the clone already reflected the consensus when compared with other deposited genotype 4a sequences.39 Instead, we focused on the 10 amino acids of ED43-NS5B that differ from conserved sequences of other HCV genotype strains for which efficient infectious culture systems had been developed (online supplemental figure 1A)21 and found that a subset of these changes facilitated adaptation of the full-length ED43 clone. Our ED43cc virus was highly efficient and produced titres of ~5.1 log10FFU/mL after 6 days of infection (table 1). It should be noted that the ED43cc virus contains numerous substitutions identified through an extensive adaptation process. Thus, we cannot rule out that these adaptive substitutions could impact selection of viral resistance to DAAs. Among substitutions identified in our study and in Watanabe et al,29 substitutions at positions 271 (V271F/G) and 2413 (D2413G) were commonly observed, suggesting that these changes might be important for the culture viability of this particular virus strain. It is worth mentioning that selection of viral resistance to DAAs and development of whole-virus vaccine candidates require highly efficient viruses.

Genotype 4a ED43 replicon systems have been developed.38 40 Nevertheless, the cell culture adaptive mutations identified in this study could be an alternative to generate even more efficient genotype 4 subgenomic replicons, as recently demonstrated for strain DBN3a of genotype 3a.4 41 Such replicons with or without RAS, recapitulating only the intracellular replication of the virus, are useful tools to study the effect of antivirals on replication but cannot be used to understand genomic-wide mutation networks.22

Infectious cell culture systems can be important tools for vaccine development. The efficient growth of the ED43cc virus, with high infectivity titres, might permit the production of enough virus to generate inactivated whole virus vaccine candidates for preclinical testing. Alternatively, further cell culture adaptation can be achieved through serial passage of ED43cc, as described previously for another recombinant.23 Thus, the highly adapted ED43cc virus could contribute to the production of HCV virions needed in whole virus particle vaccine studies. Nevertheless, we must acknowledge a putative influence of the cell culture-adaptive substitutions needed to grow ED43 in culture in the overall viral sensitivity to neutralising antibodies, which could influence vaccine-induced immune responses. Particularly, C458R(E2) has been shown to induce viral escape from host-immune responses.42 Furthermore, adaptive substitutions might also influence viral sensitivity to DAAs and facilitate viral escape; however, as the study of HCV in culture is dependent on adaptive mutations this is a universal limitation of cell culture systems.

We showed that heterologous ED43 viral populations containing different RASs evolved under various DAA treatments, which resulted in positive selection of RASs conferring high levels of resistance (figures 2A–C, 3A–E and 4A). Also, the emergence and number of RASs did not depend only on the initial potency of the drug (EC50). At a concentration of 8xEC50, A156T/V/M emerged during treatments with grazoprevir and glecaprevir, but not with paritaprevir, suggesting higher selection pressure of glecaprevir and grazoprevir during long-term treatment despite similar potency (figure 2A vs 2B and C). For NS5A inhibitors, a similar effect was observed, since despite exhibiting similar potency, ombitasvir selected a single RAS, while ledipasvir and elbasvir selected double RAS during long-term treatment (figure 3A vs 3B and C). The observed RASs L28V and L30R+Y93H also developed in genotype 4-infected patients after treatment failures with ombitasvir and ledipasvir containing regimens, respectively.43

Additionally, our data suggest that viral escape heavily relied on the fitness of the corresponding RAS-containing ED43 variant. Most NS3P RASs were detrimental for viral fitness and reverted to wildtype, as also shown previously for other genotypes in culture.31 For A156M, although it was maintained when introduced singly in ED43, compensatory substitutions were required to improve fitness (figure 2F). Clinically, this RAS has been detected in HCV-infected patients failing grazoprevir/elbasvir, including in genotype 4 infections.44

The only NS5A RAS with a high fitness cost was NS5A-L30Δ, which could partly be compensated by NS5A-T75I (figure 3H). In line with the loss of fitness of L30Δ, we previously showed that an NS5A-P32 deletion led to low fitness, but it conferred high levels of resistance to all clinically relevant NS5A inhibitors in genotype 1 viruses.34 In genotype 1-infected patients failing glecaprevir/pibrentasvir, NS5A-P32 deletion is also observed.45

The NS5B-S282T is usually associated with reduced fitness, thus, it is rarely detected at baseline in HCV-infected patients.2 However, it was reported that this RAS could be selected in culture under sofosbuvir treatment.3 4 46 We showed that S282T was gradually selected under sofosbuvir treatment of genotype 4a and maintained without drug pressure (figure 4A). In fact, compared with other genotypes, S282T is more frequently found in genotype 4-infected patients after DAA failures.14 15 47 In previous cell culture studies, we demonstrated that a genotype 6a recombinant harbouring S282T exhibited severely impaired fitness, in contrast to the relatively fit 4a recombinant (figure 4C), suggesting differential effect of S282T among genotypes.3 This relative fitness advantage observed for genotype 4 could enable the S282T virus to accumulate additional substitutions for facilitating its long-term persistence after treatment failures. If the same occurs in patients, it could consequently decrease the barrier of resistance of sofosbuvir-containing regimens.

DAA combination treatments for genotype 4 have not been investigated in detail in culture. Our data showed that recommended DAA regimens were highly efficient against the original genotype 4 virus (figures 5A–C and 6A, B). Similarly, these regimens are highly efficient in the clinic.11 13 Nonetheless, viral resistance to DAA combinations remains an issue, which could hamper treatment. In Egypt, treatment failures occur in 3%–5% of genotype 4-infected patients.12 As treatment failure due to antiviral resistance is universally linked to NS5A inhibitor resistance, a valid option for a salvage DAA regimen should include the pan-genotypic NS5A inhibitor pibrentasvir, which exhibits higher potency against most NS5A-resistant variants.34 Indeed, we showed that glecaprevir/pibrentasvir remained efficient against the 4a viruses harbouring NS5A RASs (figure 7A). This effectiveness was likely due to the high barrier to resistance of pibrentasvir, as shown by resistance profile testing (figure 3F).34 Moreover, the virus harbouring NS5B-S282T was also eradicated by this combination. This finding has important implications for patients failing regimens containing an NS5A inhibitor combined with sofosbuvir, which have been used for the treatment of a high number of infected individuals in Egypt. In addition, since in this study the biggest loss of fitness in the ED43 virus was only associated with the introduction of substitutions at NS3-156 and NS5A-L30Δ, glecaprevir/pibrentasvir exhibits a high barrier to resistance. In fact, it was reported that patients failing treatment with an NS5A inhibitor and sofosbuvir were retreated with glecaprevir/pibrentasvir, resulting in >90% SVR.37 Importantly, most patients had baseline NS5A RASs before retreatment.37

In our study, the viruses with NS3P RASs conferring high-level glecaprevir resistance could not be eradicated by glecaprevir/pibrentasvir (figure 7A). Possible retreatment options for these viruses could include triple combinations of velpatasvir/sofosbuvir/voxilaprevir or glecaprevir/pibrentasvir with the addition of sofosbuvir and/or ribavirin, which have shown great efficacy in patients.48 49 Therefore, it would be relevant to test these combinations against PI escape viruses in future studies, using developed infectious full-length culture systems of genotypes 1a, 2a, 2b, 2c, 3a, 4a and 6a.21 29 50

In summary, we developed a highly efficient full-length HCV genotype 4a infectious culture system. Besides its use to improve our understanding about DAA resistance, this system could serve as a useful tool for the development of an HCV vaccine, which is urgently needed for control of HCV worldwide.23 Here, we performed an extensive analysis of all clinically relevant DAAs that are currently being used for the treatment of genotype 4 infections. NGS and linkage analysis revealed complex dynamics operating in the selection of different RASs during treatments. The relatively high fitness and stability of NS5B-S282T observed in ED43 recombinants could have implications for the persistence of this RAS in genotype 4 infections after treatment with sofosbuvir-containing regimens. However, we showed that glecaprevir/pibrentasvir might be a promising salvage DAA regimen for the retreatment of genotype 4 after failure with sofosbuvir/NS5A inhibitor-containing regimens, as also shown recently for genotype 2 using full-length culture systems.50 The detailed understanding of the evolutionary mechanisms underlying emergence of RASs generated here can contribute to efforts directed at avoiding the emergence and transmission of DAA-resistant viruses and thus to prevent treatment failure in the future.

Acknowledgments

We thank Anna-Louise Sørensen and Lotte Mikkelsen (Hvidovre Hospital) for laboratory assistance, Bjarne Ørskov Lindhardt (Hvidovre Hospital) and Carsten Geisler (University of Copenhagen) for valuable support. We thank C.M. Rice (Rockefeller University, New York) and R. Purcell (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda) for providing reagents.

Footnotes

Contributors: Study concept and design: LP, SR and JB. Acquisition of data: LP, MSP, UF, CF-A, DH, KS and SR. Analysis and interpretation of data: LP, UF, SR and JB. Manuscript preparation: LP, SR and JB. Revision and approval of manuscript: all authors. Resources: LP, UF, CF-A, KS, SR and JB. Study supervision: SR and JB.

Funding: This study was supported by grants from The Region H Foundation (SR, JB), The Lundbeck Foundation (JB), The Novo Nordisk Foundation (JB), Independent Research Fund Denmark (DFF), Medical Sciences (SR, JB), Innovation Fund Denmark (Infect-ERA EU, JB), the Candys Foundation (LP, CF-A, JB), The Danish Cancer Society (JB) and the Weimann Foundation (UF). JB is the 2015 recipient of the Novo Nordisk Prize and the 2019 recipient of a Distinguished Investigator grant from the Novo Nordisk Foundation.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Data availability statement

All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as supplemental information.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not required.

References

- 1. Li DK, Chung RT. Overview of direct-acting antiviral drugs and drug resistance of hepatitis C virus. Methods Mol Biol 2019;1911:3–32. 10.1007/978-1-4939-8976-8_1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Pawlotsky J-M. Hepatitis C Virus Resistance to Direct-Acting Antiviral Drugs in Interferon-Free Regimens. Gastroenterology 2016;151:70–86. 10.1053/j.gastro.2016.04.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Pham LV, Ramirez S, Gottwein JM, et al. HCV genotype 6a escape from and resistance to Velpatasvir, Pibrentasvir, and sofosbuvir in robust infectious cell culture models. Gastroenterology 2018;154:2194–208. 10.1053/j.gastro.2018.02.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ramirez S, Mikkelsen LS, Gottwein JM, et al. Robust HCV genotype 3a infectious cell culture system permits identification of escape variants with resistance to sofosbuvir. Gastroenterology 2016;151:973–85. 10.1053/j.gastro.2016.07.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bukh J. The history of hepatitis C virus (HCV): basic research reveals unique features in phylogeny, evolution and the viral life cycle with new perspectives for epidemic control. J Hepatol 2016;65:S2–21. 10.1016/j.jhep.2016.07.035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Hedskog C, Parhy B, Chang S, et al. Identification of 19 novel hepatitis C virus Subtypes-Further expanding HCV classification. Open Forum Infect Dis 2019;6:ofz076. 10.1093/ofid/ofz076 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Simmonds P, Becher P, Bukh J, et al. ICTV virus taxonomy profile: Flaviviridae. J Gen Virol 2017;98:2–3. 10.1099/jgv.0.000672 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Davis C, Mgomella GS, da Silva Filipe A, et al. Highly diverse hepatitis C strains detected in sub-Saharan Africa have unknown susceptibility to direct-acting antiviral treatments. Hepatology 2019;69:1426–41. 10.1002/hep.30342 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Bukh J, Meuleman P, Tellier R, et al. Challenge pools of hepatitis C virus genotypes 1-6 prototype strains: replication fitness and pathogenicity in chimpanzees and human liver-chimeric mouse models. J Infect Dis 2010;201:1381–9. 10.1086/651579 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Gottwein JM, Scheel TKH, Callendret B, et al. Novel infectious cDNA clones of hepatitis C virus genotype 3a (strain S52) and 4a (strain ED43): genetic analyses and in vivo pathogenesis studies. J Virol 2010;84:5277–93. 10.1128/JVI.02667-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. European Association for the Study of the Liver. Electronic address: easloffice@easloffice.eu, European Association for the Study of the Liver . EASL recommendations on treatment of hepatitis C 2018. J Hepatol 2018;69:461–511. 10.1016/j.jhep.2018.03.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Di Biagio A, Taramasso L, Cenderello G. Treatment of hepatitis C virus genotype 4 in the DAA era. Virol J 2018;15:180. 10.1186/s12985-018-1094-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ghany MG, Morgan TR, AASLD-IDSA Hepatitis C Guidance Panel . Hepatitis C guidance 2019 update: American association for the study of liver Diseases-Infectious diseases Society of America recommendations for testing, managing, and treating hepatitis C virus infection. Hepatology 2020;71:686–721. 10.1002/hep.31060 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Fourati S, Rodriguez C, Hézode C, et al. Frequent antiviral treatment failures in patients infected with hepatitis C virus genotype 4, subtype 4r. Hepatology 2019;69:513–23. 10.1002/hep.30225 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Newsum AM, Molenkamp R, van der Meer JT, et al. Persistence of NS5B-S282T, a sofosbuvir resistance-associated substitution, in a HIV/HCV-coinfected MSM with risk of onward transmission. J Hepatol 2018;69:968–70. 10.1016/j.jhep.2018.06.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Nguyen T, Akhavan S, Caby F, et al. Net emergence of substitutions at position 28 in NS5A of hepatitis C virus genotype 4 in patients failing direct-acting antivirals detected by next-generation sequencing. Int J Antimicrob Agents 2019;53:80–3. 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2018.09.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Minosse C, Selleri M, Giombini E, et al. Clinical and virological properties of hepatitis C virus genotype 4 infection in patients treated with different direct-acting antiviral agents. Infect Drug Resist 2018;11:2117–27. 10.2147/IDR.S179158 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Amer F, Yousif MM, Hammad NM, et al. Deep-sequencing study of HCV G4a resistance-associated substitutions in Egyptian patients failing DAA treatment. Infect Drug Resist 2019;12:2799–807. 10.2147/IDR.S214735 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Dietz J, Kalinina OV, Vermehren J, et al. Resistance-associated substitutions in patients with chronic hepatitis C virus genotype 4 infection. J Viral Hepat 2020;27:974–86. 10.1111/jvh.13322 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Abdel-Razek W, Hassany M, El-Sayed MH, et al. Hepatitis C virus in Egypt: interim report from the world's largest national program. Clin Liver Dis 2019;14:203–6. 10.1002/cld.868 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Ramirez S, Bukh J. Current status and future development of infectious cell-culture models for the major genotypes of hepatitis C virus: essential tools in testing of antivirals and emerging vaccine strategies. Antiviral Res 2018;158:264–87. 10.1016/j.antiviral.2018.07.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Lohmann V. Hepatitis C virus cell culture models: an encomium on basic research paving the road to therapy development. Med Microbiol Immunol 2019;208:3–24. 10.1007/s00430-018-0566-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Mathiesen CK, Prentoe J, Meredith LW, et al. Adaptive mutations enhance assembly and cell-to-cell transmission of a high-titer hepatitis C virus genotype 5a Core-NS2 JFH1-Based recombinant. J Virol 2015;89:7758–75. 10.1128/JVI.00039-15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Li Y-P, Ramirez S, Jensen SB, et al. Highly efficient full-length hepatitis C virus genotype 1 (strain TN) infectious culture system. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2012;109:19757–62. 10.1073/pnas.1218260109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Li Y-P, Ramirez S, Mikkelsen L, et al. Efficient infectious cell culture systems of the hepatitis C virus (HCV) prototype strains HCV-1 and H77. J Virol 2015;89:811–23. 10.1128/JVI.02877-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Li Y-P, Ramirez S, Gottwein JM, et al. Robust full-length hepatitis C virus genotype 2a and 2b infectious cultures using mutations identified by a systematic approach applicable to patient strains. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2012;109:E1101–10. 10.1073/pnas.1203829109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Ramirez S, Li Y-P, Jensen SB, et al. Highly efficient infectious cell culture of three hepatitis C virus genotype 2b strains and sensitivity to lead protease, nonstructural protein 5A, and polymerase inhibitors. Hepatology 2014;59:395–407. 10.1002/hep.26660 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Lindenbach BD, Evans MJ, Syder AJ, et al. Complete replication of hepatitis C virus in cell culture. Science 2005;309:623–6. 10.1126/science.1114016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Watanabe N, Suzuki T, Date T, et al. Establishment of infectious genotype 4 cell culture-derived hepatitis C virus. J Gen Virol 2020;101:188–97. 10.1099/jgv.0.001378 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Li Y-P, Ramirez S, Humes D, et al. Differential sensitivity of 5'UTR-NS5A recombinants of hepatitis C virus genotypes 1-6 to protease and NS5A inhibitors. Gastroenterology 2014;146:812–21. 10.1053/j.gastro.2013.11.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Jensen SB, Fahnøe U, Pham LV, et al. Evolutionary pathways to persistence of highly fit and resistant hepatitis C virus protease inhibitor escape variants. Hepatology 2019;70:771–87. 10.1002/hep.30647 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Pham LV, Jensen SB, Fahnøe U, et al. HCV genotype 1-6 NS3 residue 80 substitutions impact protease inhibitor activity and promote viral escape. J Hepatol 2019;70:388–97. 10.1016/j.jhep.2018.10.031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Fahnøe U, Bukh J. Full-Length open reading frame amplification of hepatitis C virus. Methods Mol Biol 2019;1911:85–91. 10.1007/978-1-4939-8976-8_5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Gottwein JM, Pham LV, Mikkelsen LS, et al. Efficacy of NS5A inhibitors against hepatitis C virus genotypes 1-7 and escape variants. Gastroenterology 2018;154:1435–48. 10.1053/j.gastro.2017.12.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Simister P, Schmitt M, Geitmann M, et al. Structural and functional analysis of hepatitis C virus strain JFH1 polymerase. J Virol 2009;83:11926–39. 10.1128/JVI.01008-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Schmitt M, Scrima N, Radujkovic D, et al. A comprehensive structure-function comparison of hepatitis C virus strain JFH1 and J6 polymerases reveals a key residue stimulating replication in cell culture across genotypes. J Virol 2011;85:2565–81. 10.1128/JVI.02177-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Lok AS, Sulkowski MS, Kort JJ, et al. Efficacy of Glecaprevir and Pibrentasvir in patients with genotype 1 hepatitis C virus infection with treatment failure after NS5A inhibitor plus sofosbuvir therapy. Gastroenterology 2019;157:1506–17. 10.1053/j.gastro.2019.08.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Peng B, Yu M, Xu S, et al. Development of robust hepatitis C virus genotype 4 subgenomic replicons. Gastroenterology 2013;144:59–61. 10.1053/j.gastro.2012.09.033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Combet C, Garnier N, Charavay C, et al. euHCVdb: the European hepatitis C virus database. Nucleic Acids Res 2007;35:D363–6. 10.1093/nar/gkl970 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Saeed M, Scheel TKH, Gottwein JM, et al. Efficient replication of genotype 3a and 4a hepatitis C virus replicons in human hepatoma cells. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2012;56:5365–73. 10.1128/AAC.01256-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Ward JC, Bowyer S, Chen S, et al. Insights into the unique characteristics of hepatitis C virus genotype 3 revealed by development of a robust sub-genomic DBN3a replicon. J Gen Virol 2020;101:1182–90. 10.1099/jgv.0.001486 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Fofana I, Fafi-Kremer S, Carolla P, et al. Mutations that alter use of hepatitis C virus cell entry factors mediate escape from neutralizing antibodies. Gastroenterology 2012;143:223–33. 10.1053/j.gastro.2012.04.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Halfon P, Scholtès C, Izopet J, et al. Retreatment with direct-acting antivirals of genotypes 1-3-4 hepatitis C patients who failed an anti-NS5A regimen in real world. J Hepatol 2018;68:595–7. 10.1016/j.jhep.2017.09.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Asselah T, Reesink H, Gerstoft J, et al. Efficacy of elbasvir and grazoprevir in participants with hepatitis C virus genotype 4 infection: a pooled analysis. Liver Int 2018;38:1583–91. 10.1111/liv.13727 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Uemura H, Uchida Y, Kouyama J-ichi, et al. NS5A-P32 deletion as a factor involved in virologic failure in patients receiving glecaprevir and pibrentasvir. J Gastroenterol 2019;54:459–70. 10.1007/s00535-018-01543-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Xu S, Doehle B, Rajyaguru S, et al. In vitro selection of resistance to sofosbuvir in HCV replicons of genotype-1 to -6. Antivir Ther 2017;22:587–97. 10.3851/IMP3149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Dietz J, Susser S, Vermehren J, et al. Patterns of Resistance-Associated Substitutions in Patients With Chronic HCV Infection Following Treatment With Direct-Acting Antivirals. Gastroenterology 2018;154:976–88. 10.1053/j.gastro.2017.11.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Pearlman B, Perrys M, Hinds A. Sofosbuvir/Velpatasvir/Voxilaprevir for previous treatment failures with Glecaprevir/Pibrentasvir in chronic hepatitis C infection. Am J Gastroenterol 2019;114:1550–2. 10.14309/ajg.0000000000000248 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Wyles D, Weiland O, Yao B, et al. Retreatment of patients who failed glecaprevir/pibrentasvir treatment for hepatitis C virus infection. J Hepatol 2019;70:1019–23. 10.1016/j.jhep.2019.01.031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Ramirez S, Fernandez-Antunez C, Mikkelsen LS. Cell culture studies of the efficacy and barrier to resistance of Sofosbuvir-Velpatasvir and Glecaprevir-Pibrentasvir against hepatitis C virus genotypes 2a, 2b, and 2c. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2020;64. 10.1128/AAC.01888-19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

gutjnl-2020-323585supp001.pdf (8.4MB, pdf)

Data Availability Statement

All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as supplemental information.