Abstract

From January 1996 to December 1997, 200 isolates of Streptococcus pneumoniae recovered from 200 patients treated at National Taiwan University Hospital were serotyped and their susceptibilities to 16 antimicrobial agents were determined by the agar dilution method. Sixty-one percent of the isolates were nonsusceptible to penicillin, exhibiting either intermediate resistance (28%) or high-level resistance (33%). About two-fifths of the isolates displayed intermediate or high-level resistance to cefotaxime, ceftriaxone, cefepime, imipenem, and meropenem. Extremely high proportions of the isolates were resistant to erythromycin (82%), clarithromycin (90%), and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (TMP-SMZ) (87%). Among the isolates nonsusceptible to penicillin, 23.8% were resistant to imipenem; more than 60% displayed resistance to cefotaxime, ceftriaxone, cefepime, and carbapenems; 96.7% were resistant to erythromycin; and 100% were resistant to TMP-SMZ. All isolates were susceptible to rifampin and vancomycin. The MICs at which 50% and 90% of the isolates were inhibited were 0.12 and 1 μg/ml, respectively, for cefpirome, and 0.12 and 0.25 μg/ml, respectively, for moxifloxacin. Six serogroups or serotypes (23F, 19F, 6B, 14, 3, and 9) accounted for 77.5% of all isolates. Overall, 92.5% of the isolates were included in the serogroups or serotypes represented in the 23-valent pneumococcal vaccine. The incidence of macrolide and TMP-SMZ resistance for S. pneumoniae isolates in Taiwan in this study is among the highest in the world published to date.

Streptococcus pneumoniae is a common pathogen that causes pneumonia, bacteremia, meningitis, otitis media, and sinusitis and is a major cause of morbidity and mortality among children and adults (12, 22). The clinical significance of isolates of this organism that manifest resistance to multiple antimicrobial agents, including high-level resistance to penicillin, was first recognized in South Africa in 1977 (15). Since then, penicillin-nonsusceptible S. pneumoniae (PNSSP; strains with intermediate and high-level resistance) and multidrug-resistant S. pneumoniae (MDRSP) have been isolated from different geographic areas, and in some countries their prevalence has increased remarkably in recent years (3, 13, 16, 17, 19, 25).

Pneumococci resistant to macrolides and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (TMP-SMZ) have been reported worldwide (1, 13, 16). High incidences of erythromycin- and TMP-SMZ-resistant isolates were found in Hungary, South Africa, and Spain (3, 16). Pneumococci resistant to macrolides and TMP-SMZ are frequently associated with penicillin or multiple-drug resistance and may have evolved in response to different antibiotic pressures in the various communities (3, 16). In Taiwan, macrolides and TMP-SMZ are widely used in primary care clinics and can be obtained at drugstores without a prescription. Furthermore, macrolides are frequently prescribed as the first-line drug for the treatment of patients with respiratory tract infections in hospitals (13).

The distribution of serotypes of S. pneumoniae varies according to time and geographic locations (1, 3, 10, 13, 16, 17, 19, 25, 30). Because it is impossible to include coverage against all 90 known serotypes in a vaccine, a selection should be made on the basis of the types that are most prevalent and that are more resistant to antimicrobial agents in a given geographic area. Although the current 23-valent pneumococcal vaccine is efficacious in preventing invasive pneumococcal infections, the vaccine is designed predominantly to provide coverage against the serotypes of the European and North American strains (27). Information on the prevailing serotypes of recent pneumococcal isolates associated with clinical diseases and those associated with antimicrobial resistance is essential when monitoring the appropriateness of the 23-valent vaccine (the vaccine is not available in Taiwan) (13).

In the present article we analyze data on the susceptibilities (as determined by the disk diffusion method) of S. pneumoniae strains obtained over a 14-year period from a university hospital in northern Taiwan and study the distribution of serotypes and the incidence of antimicrobial resistance among 200 clinical isolates collected from 1996 to 1997 at National Taiwan University Hospital.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial isolates.

A total of 837 isolates of S. pneumoniae were recovered from various clinical specimens from patients who were treated at National Taiwan University Hospital, a tertiary-care referral center with 2,000 beds in northern Taiwan, from January 1984 to December 1997. All the isolates were identified by recognition of the typical colony morphology on Trypticase soy agar supplemented with 5% sheep blood (BBL Microbiology Systems, Cockeyville, Md.), Gram staining characteristics, susceptibility to ethylhydrocupreine hydrochloride (optochin; Difco Laboratories, Detroit, Mich.), and bile solubility (26). Two hundred isolates of S. pneumoniae collected from January 1996 to December 1997 were preserved for further study. All of these isolates were stored at −70°C in Trypticase soy broth (BBL Microbiology Systems) with 15% glycerol and 5% sheep blood until they were tested.

Antimicrobial susceptibility testing.

The standard disk diffusion method on Mueller-Hinton agar containing 5% sheep blood (BBL Microbiology Systems) incubated in a 5% CO2 atmosphere was used as the first test to screen the 837 isolates for their susceptibilities to penicillin (10-U penicillin disk from 1984 to 1989 and 1-μg oxacillin disk since 1990) and erythromycin (15-μg disk) (23). For definition of penicillin susceptibility by the disk diffusion method in this study, isolates that had an oxacillin inhibition zone of ≤19 mm were presumptively considered resistant (intermediate and high-level resistance). The MICs of 16 antimicrobial agents for the 200 isolates were determined by the agar dilution method with Mueller-Hinton agar containing 5% sheep blood (BBL Microbiology Systems), as described by the National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards (NCCLS) (24).

The antimicrobial agents tested in this study were obtained from the corresponding manufacturers as standard powders for laboratory use: penicillin, erythromycin, gentamicin, rifampin, TMP-SMZ, and vancomycin were from Sigma Chemical Co. (St. Louis, Mo.); cefotaxime and cefpirome were from Hoechst Marion Roussel (Frankfurt, Germany); ceftriaxone was from Roche Laboratories (Nutley, N.J.); ceftazidime was from Glaxo Operations, Ltd. (Greenford, England); cefepime was from Bristol-Myers Squibb Laboratories (Princeton, N.J.); imipenem was from Merck Sharp & Dohme (West Point, Pa.); meropenem was from Sumitomo Pharmaceuticals (Osaka, Japan); clarithromycin was from Abbott Laboratories Pharmaceutical Products Division (North Chicago, Ill.); and ciprofloxacin and moxifloxacin were from Bayer Co. (Leverkusen, Germany). The concentrations of these drugs ranged from 0.03 to 256 μg/ml; the concentration of TMP-SMZ (concentration ratio, 1:19), however, ranged from 0.03 to 32 μg/ml (trimethoprim component). The plates were incubated in ambient air, and the MICs were read at 18 to 20 h. The MIC breakpoints for susceptibility or resistance for all drugs except ceftazidime, cefpirome, ciprofloxacin, moxifloxacin, and gentamicin are according to the 1998 guidelines of NCCLS (24). No criteria for ceftazidime, cefpirome, ciprofloxacin, moxifloxacin, and gentamicin were provided by NCCLS. Staphylococcus aureus ATCC 29213, Enterococcus faecalis ATCC 29212, and S. pneumoniae ATCC 49619 were used as control strains in each set of tests.

MDRSP was defined as a strain that was nonsusceptible to at least three of the classes of antibiotics tested. In the present study, PNSSP isolates were designated as isolates with intermediate resistance or high-level resistance to penicillin (MICs, ≥0.12 μg/ml).

β-Lactamase detection.

The β-lactamase activities of the isolates were determined by a chromogenic cephalosporin assay (Cefinase; BBL Microbiology Systems).

Serotype determination.

All isolates were serogrouped or serotyped by the capsular swelling (Quellung reaction) method (17). Serogroups 23, 19, and 6 were further serotyped with the corresponding factor sera. All antisera were obtained from the Statens Seruminstitut in Copenhagen, Denmark.

Statistics.

The two-tailed Fisher’s exact test was used for statistical analysis. A P value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Trend of penicillin and erythromycin nonsusceptibility.

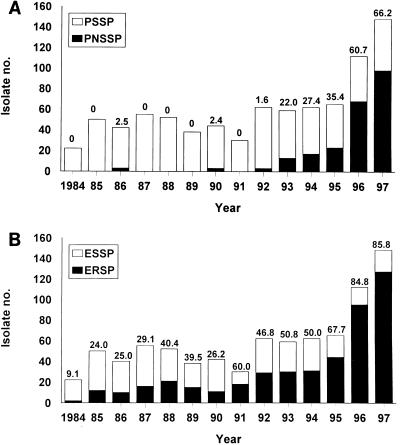

Figure 1 shows the annual incidences of penicillin nonsusceptibility and erythromycin resistance (including intermediate and high-level resistance) among the 837 isolates of S. pneumoniae obtained from 1984 to 1997. The numbers of the organisms isolated rose remarkably in 1996 and 1997 compared with the numbers recovered before 1996. A PNSSP isolate might have first been seen in 1986 (the disk used for determination of penicillin susceptibility was not the standard 1-μg oxacillin disk), and a stepwise increase in the rates of PNSSP from 1.6% in 1992 to 66.2% in 1997 was also noted. A dramatic rise in the rate of erythromycin resistance was also seen, from 9.1% in 1984 to 85.8% in 1997.

FIG. 1.

Incidences of PNSSP (A) and erythromycin-resistant S. pneumoniae (B) isolates at National Taiwan University Hospital from 1984 to 1997. Susceptibility testing was performed by the disk diffusion method. For penicillin susceptibility testing the 10-U penicillin disk was used from 1984 to 1989 and the 1-μg oxacillin disk was used after 1990. The numbers above the bars indicate the percentage of isolates with penicillin nonsusceptibility and erythromycin resistance in each year. ERSP, erythromycin-resistant S. pneumoniae; ESSP, erythromycin-susceptible S. pneumoniae.

Antimicrobial susceptibilities.

Table 1 presents the MIC range, the MICs at which 50% of isolates are inhibited (MIC50s), and the MIC90s of the 16 antimicrobial agents for 200 isolates of S. pneumoniae. MICs of the 11 agents tested for all three control strains were within the acceptable quality control ranges provided by NCCLS (24). None of the isolates produced β-lactamase. Sixty-one percent of the isolates were nonsusceptible to penicillin, exhibiting either intermediate resistance (28%) or high-level resistance (33%). For 18 isolates (9%) penicillin MICs were ≥4 μg/ml. Among the five cephalosporins tested, cefpirome was the most active, with the MIC50 and the MIC90 being 0.12 and 1 μg/ml, respectively. Extremely large numbers of the isolates were resistant (including intermediate and high-level resistance) to erythromycin (82%), clarithromycin (90%), and TMP-SMZ (87%). All isolates were susceptible to rifampin and vancomycin. The MIC50 and MIC90 were 0.12 and 0.5 μg/ml, respectively, for cefpirome, and 0.12 and 1 μg/ml, respectively, for moxifloxacin. The activity of moxifloxacin was eightfold higher than that of ciprofloxacin. Table 2 presents the MIC ranges, MIC50s, MIC90s, and percentages of resistance of eight agents for which the criteria defining susceptibility or resistance were provided by NCCLS for penicillin-susceptible S. pneumoniae (PSSP) and PNSSP isolates. Among the PNSSP isolates, more than 60% were also resistant to cefotaxime, ceftriaxone, cefepime, and carbapenems, 96.7% were resistant to erythromycin, and 100% were resistant to TMP-SMZ. All penicillin-resistant S. pneumoniae (PRSP) isolates were resistant to multiple drugs.

TABLE 1.

Susceptibilities of 200 S. pneumoniae isolates to 16 antimicrobial agents

| Agent | MIC (μg/ml)

|

Isolate susceptibility (% of isolates)a

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Range | 50% | 90% | S | I | R | |

| Penicillinb | <0.03–8 | 0.25 | 2 | 39.0 | 28.0 | 33.0 |

| Cefotaxime | <0.03–16 | 0.5 | 2 | 61.5 | 16.5 | 22.0 |

| Ceftriaxone | <0.03–32 | 0.5 | 2 | 61.5 | 15.5 | 23.0 |

| Ceftazidime | <0.03–128 | 4 | 16 | |||

| Cefepime | <0.03–8 | 0.5 | 2 | 57.5 | 18.5 | 24.0 |

| Cefpirome | <0.03–8 | 0.12 | 1 | |||

| Imipenem | <0.03–4 | 0.06 | 0.5 | 60.5 | 29.5 | 10.0 |

| Meropenem | <0.03–4 | 0.12 | 0.5 | 61.5 | 28.5 | 10.0 |

| Erythromycin | <0.03–>256 | 64 | >256 | 18.0 | 5.5 | 76.5 |

| Clarithromycin | <0.03–>256 | 128 | >256 | 10.0 | 9.0 | 81.0 |

| Ciprofloxacin | <0.03–4 | 1 | 2 | |||

| Moxifloxacin | <0.03–0.5 | 0.12 | 0.25 | |||

| Gentamicin | 0.5–64 | 16 | 32 | |||

| Rifampin | <0.03–0.25 | 0.06 | 0.12 | 100.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| TMP-SMZc | <0.12–>32 | 16 | >32 | 13.0 | 6.0 | 81.0 |

| Vancomycin | <0.03–1 | 0.25 | 0.5 | 100.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

S, susceptible; I, intermediate; R, resistant.

Among the 66 isolates for which MICs were ≥2 μg/ml, MICs were 2 μg/ml for 48 isolates, 4 μg/ml for 5 isolates, and 8 μg/ml for 13 isolates.

Ratio of concentrations of trimethoprim and sulfamethoxazole, 1:19.

TABLE 2.

Susceptibilities of PSSP and PNSSP to eight antimicrobial agents

| Antimicrobial agent | MIC (μg/ml)

|

% Resistant isolates

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Range

|

50%

|

90%

|

||||||

| PSSP | PNSSP | PSSP | PNSSP | PSSP | PNSSP | PSSP | PNSSP | |

| Cefotaxime | <0.03–0.5 | <0.03–16 | <0.03 | 1 | 0.06 | 8 | 0.0 | 63.1 |

| Ceftriaxone | <0.03–0.5 | <0.03–32 | <0.03 | 1 | 0.25 | 8 | 0.0 | 63.1 |

| Cefepime | <0.03–1 | 0.06–8 | <0.03 | 1 | 0.25 | 4 | 5.1 | 66.4 |

| Imipenem | <0.03–0.25 | <0.03–4 | <0.03 | 0.25 | 0.06 | 1 | 0.0 | 64.8 |

| Meropenem | <0.03–0.25 | <0.03–4 | <0.03 | 0.25 | 0.06 | 1 | 0.0 | 63.1 |

| Erythromycin | <0.03–>256 | 2–>256 | 8 | 64 | >256 | >256 | 59.0 | 96.7 |

| TMP-SMZa | <0.03–>32 | 0.5–>32 | 4 | 16 | >32 | >32 | 84.6 | 100.0 |

| Vancomycin | <0.03–0.5 | <0.03–1.0 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

Ratio of concentrations for trimethoprim and sulfamethoxazole, 1:19.

Serotype distribution.

The distribution of serotypes of the 200 isolates of S. pneumoniae tested in this study as well as those obtained from two previous Taiwanese studies is presented in Table 3. In the present study, 185 isolates (92.5%) belonged to 15 different serotypes and 7.5% of the isolates were nontypeable. Serogroups or serotypes 23, 19, 6, 14, 3, and 9 accounted for 80.5% of all isolates (Table 3). All serogroup 6 isolates belonged to serotype 6B, 97% of serogroup 23 isolates belonged to serotype 23F, and 91% of serogroup 19 isolates belonged to serotype 19F. Compared with the serogroup and serotype profiles presented in two previous studies for isolates obtained during different time periods, four major serogroups and serotypes varied in their frequencies: the frequencies of serogroups and serotypes 23 and 19 increased remarkably, and those of serogroups and serotypes 14 and 1 declined (10, 13). Overall, 92.5% of the isolates were included in the serogroups or serotypes covered by the 23-valent pneumococcal vaccine.

TABLE 3.

Serogroup or serotype distributions of S. pneumoniae isolates in Taiwan

| Serogroup or serotype | No. (%) of isolates

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| 1984–1987a | 1990–1993b | 1996–1997 | |

| 23 | 15 (8.8) | 18 (15.7) | 65 (32.5)c |

| 19 | 18 (10.6) | 5 (4.3) | 44 (22.0)d |

| 6 | 16 (9.4) | 12 (10.4) | 21 (10.5)e |

| 14 | 17 (10.0) | 22 (19.1) | 11 (5.5) |

| 3 | 10 (5.9) | 20 (17.4) | 10 (5.0) |

| 9 | 7 (4.1) | 2 (1.7) | 10 (5.0) |

| 1 | 5 (2.9) | 0 (0.0) | 6 (3.0) |

| 20 | 2 (1.2) | 1 (0.9) | 6 (3.0) |

| 18 | 2 (1.2) | 2 (1.7) | 6 (3.0) |

| Others | 78 (45.8) | 24 (20.9) | 6 (3.0)f |

| Nontypeable | 0 (0.0) | 9 (7.8) | 15 (7.5) |

| Total | 170 (100) | 115 (100) | 200 (100) |

Data from reference 10.

Data from reference 13.

Includes serotypes 23F (63 isolates) and 23A (2 isolates).

Includes serotypes 19F (40 isolates) and 19A (4 isolates).

All isolates belong to serotype 6B.

Include serogroups or serotypes 8 (two isolates), 11 (two isolates), 10 (one isolate), and 20 (one isolate).

Patients’ ages, sources of specimens, serotype distributions, and antimicrobial susceptibilities.

As indicated in Table 4, the majority (60%) of the isolates studied were recovered from respiratory secretions, followed by blood samples (27%). The incidence of PRSP isolates varied with the source of the specimen from which the isolate was recovered; values ranged from 41% among isolates from blood samples to 83% among isolates from upper respiratory secretions. Isolates of respiratory origins also had higher incidences of resistance to erythromycin (nearly 90%) and TMP-SMZ (>90%) compared with the incidences for isolates from blood samples (<80%). Only four isolates were recovered from cerebrospinal fluid; among these four isolates, two were susceptible to penicillin, ceftriaxone, and cefotaxime and the remaining two isolates had high-level resistance (MICs, 2 μg/ml for each agent) to these three agents.

TABLE 4.

Antimicrobial resistance and serogroup or serotype distributions of 200 S. pneumoniae isolates in specimens from different body sites

| Specimen | No. of isolates | No. (%) of isolates nonsusceptiblea to the following:

|

No. (%) of each of the following major serogroups or serotypes:

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Penicillinb | Erythromycin | TMP-SMZ | 23 | 19 | 6 | 14 | 3 | 9 | ||

| Throat, nose, ear, or sinus | 36 | 30 (83) | 32 (89) | 34 (94) | 18 (50) | 6 (17) | 5 (14) | 2 (6) | 1 (3) | 3 (8) |

| Sputum or bronchial washing | 85 | 59 (69) | 76 (89) | 82 (96) | 29 (34) | 17 (20) | 7 (8) | 3 (4) | 4 (5) | 1 (1) |

| Blood | 54 | 22 (41) | 39 (72) | 42 (78) | 14 (26) | 14 (26) | 5 (9) | 4 (7) | 2 (4) | 4 (7) |

| Cerebrospinal fluid | 4 | 2 (59) | 2 (50) | 1 (50) | 2 (50) | 1 (25) | 1 (25) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Pleural effusion | 4 | 2 (50) | 3 (75) | 2 (50) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Miscellaneousc | 17 | 7 (41) | 12 (71) | 13 (81) | 2 (13) | 6 (38) | 3 (19) | 2 (13) | 3 (19) | 1 (6) |

Includes intermediate and high-level resistant strains.

The numbers of isolates for which MICs were ≥2 μg/ml were as follows: 20 isolates from the throat, nose, ear, or sinus specimens, 30 isolates from sputum or bronchial washing specimens, 10 isolates from blood specimens, 2 isolates from cerebrospinal fluid specimens, 1 isolate from a pleural effusion specimens and 3 isolates from other specimens. Isolates for which penicillin MICs were 8 μg/ml were all recovered from respiratory sources.

These specimens included would discharge (14 isolates), ascites fluid (1 isolate), synovial fluid (1 isolate), and bile (1 isolate).

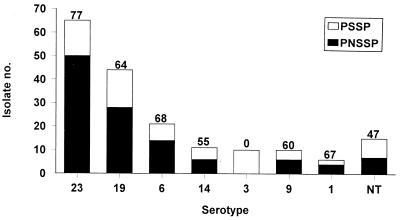

The six major serogroups and serotypes of S. pneumoniae were widely distributed in the various specimens (Table 4). Among the 54 isolates from blood, 28 (52%) isolates belonged to serogroups 23 and 19 and only 2 (4%) isolates were of serotype 3. PNSSP isolates belonged to 10 serogroups or serotypes. Among them, serogroup 23 isolates had the highest incidence of penicillin nonsusceptibility (Fig. 2). For 60% (38 isolates) of PNSSP serotype 23F isolates and 71% (15 isolates) of PNSSP serotype 6B isolates, erythromycin MICs were ≥256 μg/ml. For 80% (32 isolates) of PNSSP 19F isolates penicillin MICs were 1 to 2 μg/ml. None of pneumococcal serotype 3 isolates was nonsusceptible to penicillin.

FIG. 2.

Serogroup and serotype distributions and proportions of S. pneumoniae isolates with nonsusceptibility to penicillin. NT, nontypeable. The numbers above the bars indicate the percentage of S. pneumoniae isolates in each serogroup or serotype.

The incidence of penicillin nonsusceptibility for isolates recovered from patients who were ≤15 years of age (108 isolates; 90 isolates were recovered from children who were <5 years old) and those from patients who were >16 years of age (92 isolates) was not significantly different (65 versus 57%; P > 0.05). The differences in the incidences of resistance to erythromycin and TMP-SMZ between these two groups were also not statistically significant. The serogroup distributions of isolates from these two patient populations (≤15 years of age and >16 years of age) were similar: for serogroup 23, 30 versus 35 isolates; for serogroup 19, 20 versus 24 isolates; and for serogroup 6, 12 versus 9 isolates.

DISCUSSION

Resistance to penicillin and other β-lactam antibiotics among strains of S. pneumoniae is now widespread, and the rate is rapidly rising worldwide (3, 16). The highest rates (>50%) of penicillin nonsusceptibility of clinical pneumococcal isolates have been reported in Hungary, Spain, South Africa, and Korea (3, 15, 17, 19). In the present study, the remarkably stepwise increase in the rate of penicillin nonsusceptibility from 1.6% in 1992 to 66.2% in 1997 is impressive. This remarkable increase in the rate of penicillin nonsusceptibility existed not only among isolates from respiratory sources but also among those that cause invasive infections (12, 13). This finding suggests that PNSSP has been spreading very rapidly over the past few years in Taiwan.

Two facets regarding the antimicrobial susceptibilities and serotype distributions of clinical isolates of S. pneumoniae in Taiwan are of particular importance. First, the incidences of macrolide and TMP-SMZ resistance of Taiwanese S. pneumoniae isolates in this study are among the highest figures published to date. Second, the high incidence of macrolide-resistant, TMP-SMZ-resistant, and PNSSP isolates is probably due to the dissemination of clones of some serotypes, i.e., serotypes 23F, 19F, and 6B (12).

In Taiwan, we are concerned with the current status of the high incidence of macrolide resistance among respiratory bacterial pathogens, especially S. pneumoniae, for two reasons (13, 14, 29, 32). First, erythromycin and some long-acting new macrolides (roxithromycin, clarithromycin, and azithromycin) are commonly used in primary care clinics (both adult and pediatric clinics) and are prescribed for the treatment of respiratory tract infections in outpatients and hospitalized patients. Furthermore, these drugs can easily be obtained at drugstores without a prescription (13). The widespread use of macrolides might contribute to the extremely high incidence of macrolide resistance among nasopharyngeal isolates that colonize healthy children (9) or clinical isolates of S. pneumoniae from various sources from symptomatic patients (as shown in this study) in Taiwan. Second, the guidelines for the treatment of community-acquired pneumonia in adults recommended by the 1993 American Thoracic Society and the 1998 Infectious Diseases Society of America as well as the suggestions for the management of sinusitis, otitis media, and chronic bronchitis, which all (ATS and IDSA) included one macrolide or TMP-SMZ as the drug of choice or as an alternative antimicrobial agents, may be inappropriate in this area because of the high incidence of resistance to these two agents (2, 5, 22).

The continued spread of PNSSP strains, particularly MDRSP strains, is providing a therapeutic dilemma (5, 7, 8, 15). Recent studies recommended that pneumonia and/or bacteremia caused by S. pneumoniae strains for which penicillin MICs are ≤2 μg/ml may be treated successfully with intravenous high-dose penicillin (5, 8, 15). If we followed these guidelines for the empiric treatment of community-acquired pneumonia, vancomycin or other agents that are active in vitro are preferred because for ≥30% of the isolates MICs are ≥2 μg/ml (5, 8, 15). For bacterial meningitis in adults and children, an empiric antibiotic regimen should also include vancomycin (vancomycin alone or in combination with ceftriaxone or cefotaxime) because many of the S. pneumoniae isolates tested were nonsusceptible to penicillin and extended-spectrum cephalosporins (15, 21, 23, 24). Further isolates from cerebrospinal fluid or blood specimens from Taiwanese patients with meningitis should be studied for their susceptibilities to these agents. From the MIC point of view, moxifloxacin and cefpirome may be agents with potential for the treatment of infections caused by PRSP in Taiwan (28, 31).

The remarkably high incidence of TMP-SMZ resistance in S. pneumoniae isolates in Taiwan was first documented in this study. The upsurge in resistance associated with the increased incidence of penicillin resistance and multidrug resistance has been reported in many countries (1, 16). The chronological trend of resistance to this drug in the National Taiwan University Hospital is not known because this drug was not included in the antibiotic panel for routine disk susceptibility testing of S. pneumoniae isolates. However, our previous study showed no TMP-SMZ resistance among 115 isolates (PNSSP, 12.2%; MDRSP, 40.9%) recovered from southern Taiwan (13). There is no plausible explanation for this change in the rate of resistance. More isolates should be collected from various parts of Taiwan, and molecular studies should be conducted to clarify this phenomenon.

The serotype distribution of the S. pneumoniae strains reported in this study was different from those described for isolates obtained during other time periods in Taiwan and is similar to those for isolates from some other geographic areas of the world (1, 10, 13, 17, 18, 19, 25, 30). Fulminant infections that were caused by serotype 3 isolates and that resulted in a rapidly fatal outcome were a major threat in the past few years in Taiwan (12). Fortunately, at present the incidence of this serotype has decreased compared to that reported in our previous study (13). Although penicillin resistance in serotype 3 strains was recently reported in Norway, all of our Taiwanese serotype 3 isolates were susceptible to penicillin (6, 12).

In conclusion, this survey provides further emphasis for the need to routinely test S. pneumoniae isolates for their antimicrobial susceptibilities. With the increasing incidence of PNSSP and MDRSP in Taiwan and the decreasing availability of adequate antibiotic treatments for PNSSP infections, strict control of antibiotic usage and the introduction of the 23-valent pneumococcal vaccine seem to be essential for improving the present unfavorable situation.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This work was partly supported by a grant (NSC86-2314-B-002-053) from the National Science Council of the Republic of China.

REFERENCES

- 1.Adrian P V, Klugman K P. Mutation in the dihydrofolate reductase gene of trimethoprim-resistant isolates of Streptococcus pneumoniae. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1997;41:2406–2413. doi: 10.1128/aac.41.11.2406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.American Thoracic Society. Guidelines for the initial management of adults with community-acquired pneumonia: diagnosis, assessment of severity, and initial antimicrobial therapy. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1993;148:1418–1426. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/148.5.1418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Appelbaum P C. Antimicrobial resistance in Streptococcus pneumoniae: an overview. Clin Infect Dis. 1992;15:77–83. doi: 10.1093/clinids/15.1.77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barnes D M, Whittier S, Gilligan P H, Soares S, Tomasz A, Henderson F W. Transmission of multidrug-resistant serotype 23F Streptococcus pneumoniae in group day care: evidence suggesting capsular transformation of the resistant strain in vivo. Clin Infect Dis. 1995;171:890–896. doi: 10.1093/infdis/171.4.890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bartlett J G, Breiman R F, Mandell L A, File T M., Jr Community-acquired pneumonia in adults: guidelines for management. Clin Infect Dis. 1998;26:811–838. doi: 10.1086/513953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bergan T, Gaustad P, Høiby E A, Berdal B P, Furuberg G, Baann J, Tønjum T. Antibiotic resistance of pneumococci in Norway. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 1998;10:77–81. doi: 10.1016/s0924-8579(98)00018-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bradley J S, Scheld W M. The challenge of penicillin-resistant Streptococcus pneumoniae meningitis: current antibiotic therapy in the 1990s. Clin Infect Dis. 1997;24(Suppl. 2):S213–S221. doi: 10.1093/clinids/24.supplement_2.s213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Campbell D G, Jr, Silberman R. Drug-resistant Streptococcus pneumoniae. Clin Infect Dis. 1998;26:1188–1195. doi: 10.1086/520286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chiou C C C, Liu Y C, Huang T S, Hwang W K, Wang J H, Lin H H, Yen M Y, Hsieh K S. Extremely high prevalence of nasopharyngeal carriage of penicillin-resistant Streptococcus pneumoniae among children in Kaoshsiung, Taiwan. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:1933–1937. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.7.1933-1937.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chung S T, Lee J C, Shieh W C. Type distribution of pneumococcal strains in Taiwan. Chin J Microbiol Immunol. 1991;24:196–200. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Coffey T J, Daniels M, Mcdougal L K, Dowson C G, Tenover F C, Spratt B G. Genetic analysis of clinical isolates of Streptococcus pneumoniae with high-level resistance to expanded-spectrum cephalosporins. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1995;39:1306–1313. doi: 10.1128/aac.39.6.1306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hsueh, P.-R., L.-J. Teng, L.-N. Lee, P.-C. Yang, S.-W. Ho, and K.-T. Luh. Dissemination of high-level penicillin-, extended-spectrum cephalosporin-, and erythromycin-resistant Streptococcus pneumoniae in Taiwan. J. Clin. Microbiol. 37:221–224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 13.Hsueh P R, Chen H M, Lu Y C, Wu J J. Antimicrobial resistance and serotype distribution of Streptococcus pneumoniae strains isolated in southern Taiwan. J Formos Med Assoc. 1996;95:29–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hsueh P R, Chen H M, Huang A H, Wu J J. Decreased activity of erythromycin against Streptococcus pyogenes in Taiwan. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1995;61:3369–3374. doi: 10.1128/aac.39.10.2239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kaplan S L, Mason E O., Jr Management of infections due to antibiotic-resistant Streptococcus pneumoniae. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1998;11:628–644. doi: 10.1128/cmr.11.4.628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Klugman K P. Pneumococcal resistance to antibiotics. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1990;3:171–196. doi: 10.1128/cmr.3.2.171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lee H J, Park J Y, Jang S H, Kim J H, Kim E C, Choi K W. High incidence of resistance to multiple antimicrobials in clinical isolates of Streptococcus pneumoniae from a university hospital in Korea. Clin Infect Dis. 1995;20:826–835. doi: 10.1093/clinids/20.4.826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lyon D J, Scheel O, Fung K S C, Cheng A F B, Henrichsen J. Rapid emergence of penicillin-resistant pneumococci in Hong Kong. Scand J Infect Dis. 1996;28:375–376. doi: 10.3109/00365549609037922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Marton A, Gulyas M, Munoz R, Tomasz A. Extremely high incidence of antibiotic resistance in clinical isolates of Streptococcus pneumoniae in Hungary. Clin Infect Dis. 1991;163:542–548. doi: 10.1093/infdis/163.3.542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McDougal L K, Rasheed J K, Biddle J W, Tenover F C. Identification of multiple clones of extended-spectrum cephalosporin-resistant Streptococcus pneumoniae isolates in the United States. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1995;39:2282–2288. doi: 10.1128/aac.39.10.2282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Muñoz R, Coffey T J, Daniels M, Dowson C G, Laible G, Casal J, Hakenbeck R, Jacobs M, Musser J M, Spratt B G, Tomasz A. Intercontinental spread of a multiresistant clone of serotype 23F S. pneumoniae. J Infect Dis. 1991;164:302–306. doi: 10.1093/infdis/164.2.302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Musher D M. Infections caused by Streptococcus pneumoniae: clinical spectrum, pathogenesis, immunity, and treatment. Clin Infect Dis. 1992;14:801–809. doi: 10.1093/clinids/14.4.801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards. Performance standard for antimicrobial disk susceptibility tests. Approved standard. 5th ed. NCCLS document M2-A5. Wayne, Pa: National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 24.National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards. Performance standard for antimicrobial susceptibility testing, eighth informational supplement, M100-S8. Wayne, Pa: National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nissinen A, Leinonen M, Huovinen P, Herva E, Katila M L, Kontiainen S. Antimicrobial resistance of Streptococcus pneumoniae in Finland, 1987–1990. Clin Infect Dis. 1995;20:1275–1280. doi: 10.1093/clinids/20.5.1275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ruoff K L. Streptococcus. In: Murray P R, Baron E J, Pfaller M A, Tenover F C, Yolken R H, editors. Manual of clinical microbiology. 6th ed. Washington, D.C: American Society for Microbiology; 1995. pp. 299–307. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shapiro E D, Berg A T, Austrian R. The prospective efficacy of polyvalent pneumococcal polysdaccharide vaccine. N Engl J Med. 1991;325:1453–1460. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199111213252101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Spangler S K, Jacobs M R, Appelbaum P C. Susceptibilities of 177 penicillin-susceptible and -resistant pneumococci to FK 037, cefpirome, cefepime, ceftriaxone, cefotaxime, ceftazidime, imipenem, biapenem, meropenem, and vancomycin. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1994;38:898–900. doi: 10.1128/aac.38.4.898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Teng L J, Hsueh P R, Chen Y C, Ho S W, Luh K T. Antimicrobial susceptibility of viridans group streptococci in Taiwan with emphasis on the high rates of resistance to penicillin and macrolides in Streptococcus oralis. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1998;41:621–627. doi: 10.1093/jac/41.6.621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Verhaegen J, Glupczynski Y, Verbist L, Blogie M, Verbiest N, Vandeven J, Yourassowsky E. Capsular types and antibiotic susceptibility of pneumococci isolated from patients in Belgium with serious infections, 1980–1993. Clin Infect Dis. 1995;20:1339–1345. doi: 10.1093/clinids/20.5.1339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Visalli M A, Jacobs M R, Appelbaum P C. Antipneumococcal activity of BAY 128039, a new quinolone, compared with activities of three quinolones and four oral β-lactams. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1997;41:2786–2789. doi: 10.1128/aac.41.12.2786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wu J J, Lin K Y, Hsueh P R, Liu J W, Pan H I, Sheu S M. High frequency of erythromycin-resistant streptococci in Taiwan. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1997;41:844–846. doi: 10.1128/aac.41.4.844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]