ABSTRACT

Background

Urinary sediment messenger RNAs (mRNAs) have been shown as novel biomarkers of kidney disease. We aimed to identify targeted urinary mRNAs in diabetic nephropathy (DN) based on bioinformatics analysis and clinical validation.

Methods

Microarray studies of DN were searched in the GEO database and Nephroseq platform. Gene modules negatively correlated with estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) were identified by informatics methods. Hub genes were screened within the selected modules. In validation cohorts, a quantitative polymerase chain reaction assay was used to compare the expression levels of candidate mRNAs. Patients with renal biopsy–confirmed DN were then followed up for a median time of 21 months. End-stage renal disease (ESRD) was defined as the primary endpoint. Multivariate Cox proportional hazards regression was developed to evaluate the prognostic values of candidate mRNAs.

Results

Bioinformatics analysis revealed four chemokines (CCL5, CXCL1, CXLC6 and CXCL12) as candidate mRNAs negatively correlated with eGFR, of which CCL5 and CXCL1 mRNA levels were upregulated in the urinary sediment of patients with DN. In addition, urinary sediment mRNA of CXCL1 was negatively correlated with eGFR (r = −0.2275, P = 0.0301) and CCL5 level was negatively correlated with eGFR (r = −0.4388, P < 0.0001) and positively correlated with urinary albumin:creatinine ratio (r = 0.2693, P = 0.0098); also, CCL5 and CXCL1 were upregulated in patients with severe renal interstitial fibrosis. Urinary sediment CCL5 mRNA was an independent predictor of ESRD [hazard ratio 1.350 (95% confidence interval 1.045–1.745)].

Conclusions

Urinary sediment CCL5 and CXCL1 mRNAs were upregulated in DN patients and associated with a decline in renal function and degree of renal interstitial fibrosis. Urinary sediment CCL5 mRNA could be used as a potential prognostic biomarker of DN.

Keywords: chemokines, diabetic nephropathies, end-stage renal disease, gene regulatory networks, glomerular filtration rate, prognosis

INTRODUCTION

The worldwide prevalence of diabetes mellitus (DM) has increased dramatically in the past few decades. Diabetic nephropathy (DN) is an established chronic complication of DM, which occurs in  30% of patients with type 1 DM (T1DM) and 40% of type 2 DM (T2DM) patients [1]. The overall prognosis of DN is relatively poor. About 20–30% of individuals with DN will progress to end-stage renal disease (ESRD) even when on optimal glycemic control and therapy with a renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system (RAAS) blocker [2]. Estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR), an indicator of renal function, has been regarded as the preferred diagnostic and prognostic biomarker of DN in clinical practice or trials [3]. However, the abnormality of eGFR only reflects an advanced stage rather than the early functional changes. Albuminuria also predicts the progression of DN, but it lacks specificity and sensitivity for progressive decline in eGFR and occurrence of ESRD. A proportion of renal impairment happened even before the appearance of albuminuria [4]. The biomarkers currently in use are not accurate enough to predict the risk for the above-mentioned limitations. Thus, it is still a challenge to identify DN patients with a high risk of progression.

30% of patients with type 1 DM (T1DM) and 40% of type 2 DM (T2DM) patients [1]. The overall prognosis of DN is relatively poor. About 20–30% of individuals with DN will progress to end-stage renal disease (ESRD) even when on optimal glycemic control and therapy with a renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system (RAAS) blocker [2]. Estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR), an indicator of renal function, has been regarded as the preferred diagnostic and prognostic biomarker of DN in clinical practice or trials [3]. However, the abnormality of eGFR only reflects an advanced stage rather than the early functional changes. Albuminuria also predicts the progression of DN, but it lacks specificity and sensitivity for progressive decline in eGFR and occurrence of ESRD. A proportion of renal impairment happened even before the appearance of albuminuria [4]. The biomarkers currently in use are not accurate enough to predict the risk for the above-mentioned limitations. Thus, it is still a challenge to identify DN patients with a high risk of progression.

Previously, various types of cells have been described in the urinary sediment of patients with renal disease. Quantification of targeted messenger RNAs (mRNAs) in urinary sediments represents a potential non-invasive diagnostic method for multiple types of kidney injuries. The detection of podocyte markers [5], molecules associated with epithelial-mesenchymal transition [6] and inflammatory cytokines [7, 8] has emerged as a potential approach to identify novel biomarkers for diagnosis of DN. In recent years, tools of bioinformatics have also been applied to screen urinary mRNAs in DN, providing candidate biomarkers for clinical validation [9]. However, most of previous studies were cross-sectional studies, and there is still insufficient evidence on the role of urinary mRNAs in predicting the progression of DN.

Weighted gene co-expression network analysis (WGCNA), a systems biology algorithm, can identify gene modules that are co-expressed and correlated with clinical traits, providing us a powerful tool to identify candidate biomarkers in multiple diseases [10, 11]. Urinary single-cell RNA sequencing indicated the similarities in gene expression between cells of kidney and cells in urine [12]. It is suggested that the changes of gene expression in urinary cells can reflect the changes of renal tissue to some extent. In this study, we recognized the gene modules negatively related to eGFR based on available published microarray data of renal biopsies by WGCNA. Also, gene ontology (GO) and pathway enrichment analysis were conducted and candidate hub genes were identified by bioinformatics tools. Furthermore, the mRNA levels of candidate genes were detected in urine sediment and their correlations with albuminuria, eGFR and renal interstitial fibrosis were performed in validation cohorts. Finally, the patients were followed up to investigate the role of candidate biomarkers in predicting DN progression.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Gene expression data and pre-processing

Raw CEL files of microarray datasets GSE30528 and GSE30529 [13] were downloaded from the GEO Database (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/), containing mRNA data from glomeruli samples of 9 patients with DN and 13 healthy donors and tubule samples of 10 DN patients and 12 healthy donors, respectively. Raw data were pre-processed using R version 3.6.1 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria) and Bioconductor (version 2.14; www.bioconductor.org). Background correction and normalization were performed by the robust multichip average (RMA) function in the affy (version 1.52.0) R package. Then we mapped the array probes to the respective Entrez gene symbol using array annotation data in the hgu133plus2.db (version 3.11) R package. Clinical data of GSE30528 and GSE30529 were downloaded from the Nephroseq platform (https://www.nephroseq.org/), including age, sex, ethnicity and eGFR.

Bioinformatics analysis

According to the protocols of the WGCNA R package (version 1.70.3), gene co-expression modules were created based on transcript and clinical data for GSE30528 and GSE30529. Module eigengenes (MEs) were calculated to summarize and represent the gene modules. Then the MEs were analyzed for correlations with clinical traits including age, sex, ethnicity and eGFR.

To explore whether module genes share a similar biological function, the visualization of GO and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) enrichment analysis for the selected gene modules were performed using the R package clusterProfiler (version 3.11). Adjusted P-values <0.05 were considered as statistical significance. Search Tool for the Retrieval of Interacting Genes (STRING) is an online platform that collects comprehensive information of experimental and predictive interactions of proteins. It was applied to establish protein–protein interaction (PPI) networks and Cytoscape software (version 3.7.2) was used for visualization. The Maximal Clique Centrality (MCC) algorithm in cyto-hubba, a plug-in of Cytoscape software, was performed to identify hub genes in the PPI networks. In order to compare the levels of interested hub genes between DN and normal subjects, their mRNA levels were obtained from the microarray data in the two datasets. Pearson's correlation was performed between the expression levels of hub genes and eGFR.

Study participants

The study protocol was approved by the Ethical Committee of Zhongda Hospital Southeast University (2019ZDSYLL057-P01) and all of the subjects gave their written informed consent in compliance with the Helsinki Declaration. A total of 91 patients with renal biopsy–confirmed DN, 60 T2DM patients with no signs of renal damage [urinary albumin: creatinine ratio (uACR) <30 mg/g and eGFR ≥60 mL/min/1.73 m2] and 61 healthy controls (HCs) were recruited from August 2018 to July 2019 from three hospitals in China (Zhongda Hospital Southeast University, First Affiliated Hospital of Zhengzhou University and Second Xiangya Hospital of Central South University). T2DM was diagnosed based on the 2021 criteria of the American Diabetes Association [14]. DN was diagnosed by renal biopsy according to the pathological characteristics of diagnostic criteria [15]. HCs were enrolled if they were non-diabetic and without clinical or laboratory evidence of kidney diseases. The exclusion criteria were as follows: infection or cancer, signs or symptoms of non-diabetic kidney disease, eGFR <15 mL/min/1.73 m2 or receiving renal replacement therapy and suffering from a mental illness.

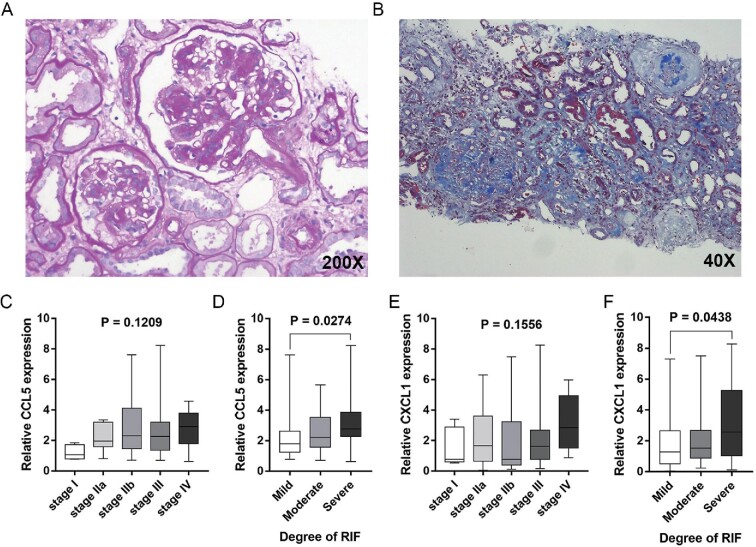

The glomerular lesions of DN were assessed according to the Tervaert classification [16], calculating the percentage of glomerulosclerosis. Ten randomly selected visual areas were assessed in each patient, and renal interstitial fibrosis was semi-quantitatively graded into mild (<25%), moderate (>25% but <50%) and severe (>50%) by calculating the average percentage of fibrosis in Masson trichrome stain of renal biopsy samples.

Collection of urine samples and total RNA extraction

A whole-stream early-morning urine specimen for each subject was collected in a sterile container and then treated within 1 h after collection. An aliquot of 50 mL was centrifuged at 3000 g for 30 min at 4°C to obtain the urine sediments. The supernatant was then discarded and the urinary pellet was washed twice in 1 mL phosphate‐buffered saline (PBS) and centrifuged at 12 500 g for 5 min at 4°C. Total RNA was isolated with the miRNeasy mini kit (217 004; Qiagen, Düsseldorf, Germany) according to the manufacturer's instructions and stored at −80°C until use.

Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assay

The quantification of the candidate genes was performed using a one-step Taqman RT-qPCR MasterMix kit (Ace105, AceBioX, Shanghai, China). Beta-2 microglobulin (B2M) was used as the housekeeping gene. Sequences of primers and Taqman probes used in the PCR assay are listed in Table 1. Briefly, 100 ng of RNA was used in 10 µL reaction mixtures with gene-specific primers and probes according to the manufacturers protocol. Cycling procedures were set as follows: 42°C for 5 min, 95°C for 10 min, followed by 45 cycles of 95°C for 20 s and 60°C for 1 min. PCR assays were operated using an ABI PRISM7700 platform (Applied Biosystems, Waltham, MA, USA). The relative levels of candidate mRNA were normalized by B2M, and the relative expression for each gene was calculated by the comparative method 2–ΔΔCT.

Table 1.

Sequences of primers and Taqman probes used in the PCR assay

| Genes | Primers | Sequences |

|---|---|---|

| CCL5 | Forward (5′- 3′) | CTGCTGCTTTGCCTACATTG |

| Reverse (5′-3′) | ACACACTTGGCGGTTCTTTC | |

| Taqman probe | FAM-CCCCGTGCCCACATCAAGGA-BHQ1 | |

| CXCL1 | Forward (5′- 3′) | CTGACCAGAAGGGAGGAGGA |

| Reverse (5′-3′) | CCTCTGCAGCTGTGTCTCTC | |

| Taqman probe | FAM-CCTGAAGGAGGCCCTGCCCT-BHQ1 | |

| CXCL6 | Forward (5′- 3′) | AGATCCCTGGACCCAGTAAGA |

| Reverse (5′-3′) | AACTTCAGGGAGAAGCGTAGG | |

| Taqman probe | FAM-TCCCTACTTTGAAGAGTGTGGGGGA-BHQ1 | |

| CXCL12 | Forward (5′- 3′) | CAAGGTCGTGGTCGTGCT |

| Reverse (5′-3′) | AGATGCTTGACGTTGGCTCT | |

| Taqman probe | FAM-GGGAAGCCCGTCAGCCTGAG-BHQ1 | |

| B2M | Forward (5′- 3′) | TGTCTTTCAGCAAGGACTGG |

| Reverse (5′-3′) | AACTATCTTGGGCTGTGACAAA | |

| Taqman probe | FAM-CATGGTTCACACGGCAGGCATACT-BHQ1 |

Follow-up

After renal biopsy, 91 DN patients were followed up for at least 1.5 years until December 2020. The clinical strategy was made by the nephrologist alone and was not influenced by the study. Renal function tests, including serum creatinine and blood urea, were examined at least every 3 months. As mentioned, eGFR was calculated by the Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration equation according to the concentration of serum creatinine. ESRD (eGFR <15 mL/min/1.73 m2 or receiving renal replacement therapy) was defined as the primary endpoint. The overall design of our study is summarized in the Supplementary data, Figure S1.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using R version 3.6.1 SPSS Statistics 25 (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA) and GraphPad Prism 7.00 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA). The data normality was determined by the Shapiro–Wilk test. The normally distributed variables were given as mean ± standard deviation (SD) and non-normally distributed variables were given as median with interquartile range (IQR). Depending on the distribution type of values, unpaired t‑test or Mann‑Whitney U-test was used to evaluate the significant differences between DN patients and HCs; one-way ANOVA analysis of variance or Kruskal–Wallis test was performed for comparisons of data with more than two groups and Holm-Sidak's or Dunn's multiple comparisons test was performed in groups with statistical significance. Pearson's or Spearman's correlation analysis was used to evaluate the correlation between gene expression levels and eGFR or uACR for each subject. To determine the independent risk factors of the primary endpoint, multivariate Cox proportional hazards regression was developed to calculate the hazard ratio (HR) and 95% confidence interval (95% CI) and variate with P-values <0.1 in the univariate analysis were added to the regression model. All P‑values were two tailed and P < 0.05 was considered a statistically significant difference.

RESULTS

Transcriptome data and clinical characteristics of selected datasets

A total of 12 411 genes in GSE30528 and GSE30529 were identified based on the GPL571 platform (Affymetrix Human Genome U133A 2.0 Array; Affymetrix, Santa Clara, CA, USA). Dataset GSE30528 contained the transcriptome data of microdissected glomeruli samples from 9 DN patients and 13 HCs. Dataset GSE30529 contained the transcriptome data of tubule samples from 10 DN patients and 12 HCs. Clinical information, including age, race, gender and eGFR, of these two datasets was downloaded from Nephroseq open-access platforms (Supplementary data, Tables S1 and S2).

Gene modules negatively associated with eGFR identified by WGCNA mainly enriched in regulation of chemokine signaling pathway

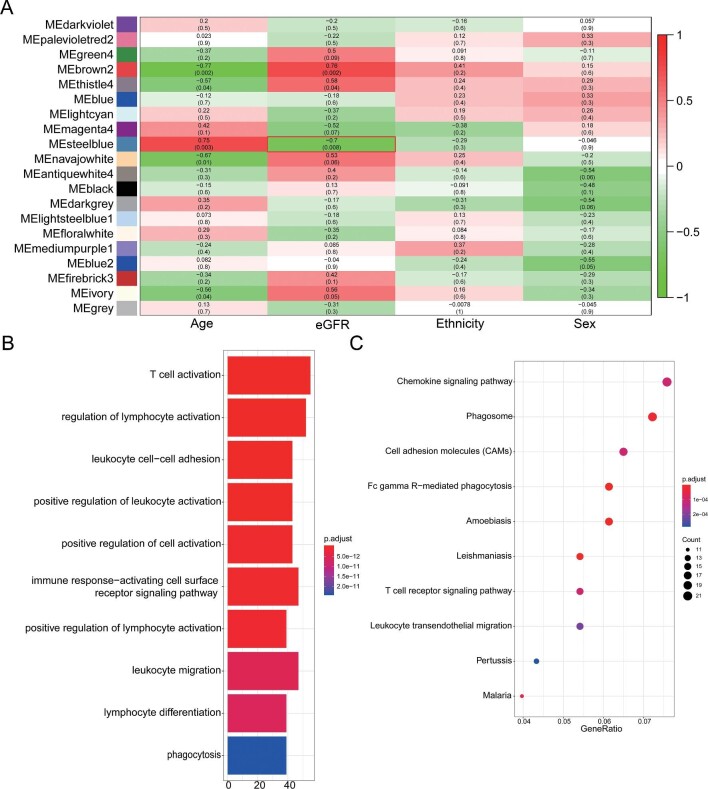

In order to find the key modules negatively associated with eGFR, WGCNA was performed on the microarray data and clinical information of GSE30528 and GSE30529. We found 19 modules in glomeruli samples and 14 modules in tubule samples. MEs were calculated as the representative for modules, then Pearson's correlation coefficients were evaluated between MEs and the clinical traits of eGFR. According to the heatmap of module–trait correlations, we identified that the steel blue module was the highest negatively correlated with eGFR (r = −0.70, P = 0.008) in glomeruli samples (Figure 1A), including 515 genes. To reveal potential biological functions of the genes within the steel blue modules, we conducted GO and KEGG pathway enrichment analysis. In glomeruli samples, the top 10 GO terms were significantly enriched in T-cell activation, regulation of lymphocyte activation, immune response and leukocyte migration (Figure 1B). According to KEGG analysis, genes were significantly enriched in the chemokine signal pathway, phagosome, cell adhesion and T cell receptor signal pathway (Figure 1C). As shown in Supplementary data, Figure S2A, the PPI network was constructed using STRING.

FIGURE 1:

Identification of gene modules negatively associated with eGFR in dataset GSE30528 and GO and KEGG pathway enrichment analysis. (A) Heatmap of the correlation between MEs and clinical characters in dataset GSE30528. The MEsteelblue was the highest negatively correlated with eGFR. (B) The top 10 terms of GO analysis of all genes in the steelblue module identified by WGCNA. (C) The top 10 terms of KEGG pathway analysis of all genes in the steelblue module identified by WGCNA. GSE30528, dataset of microarray data of microdissected glomeruli samples from 9 patients with DN and 13 HCs ME, module eigengene. Source: Woroniecka KI, Park AS, Mohtat D et al. Transcriptome analysis of human diabetic kidney disease. Diabetes 2011;60(9);2354–69; PMID: 21 752 957.

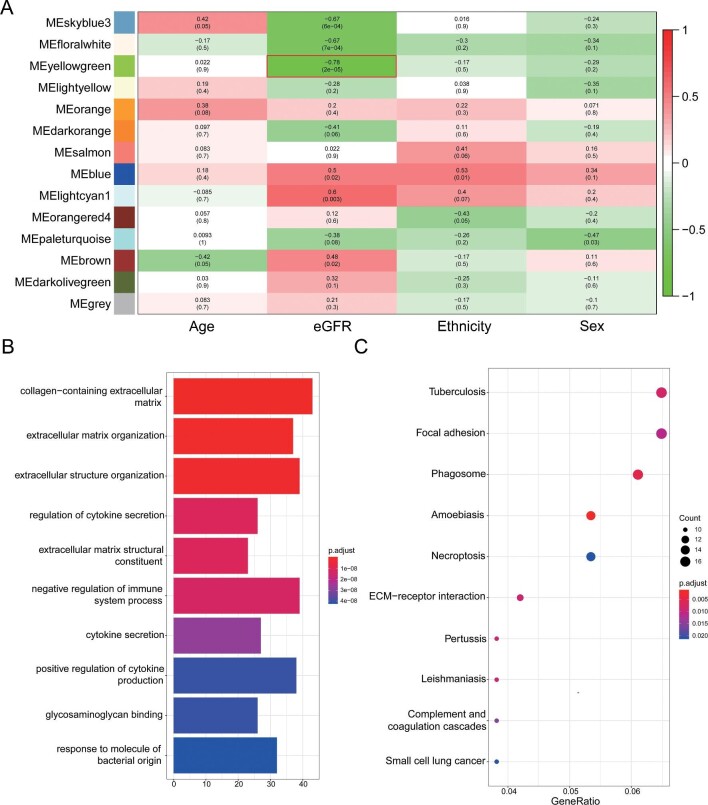

In tubule samples, the yellowgreen module showed the highest negative correlation with eGFR (r = −0.78, P = 2e-05) (Figure 2A), including 525 genes. The top 10 GO terms were significantly enriched in extracellular matrix, regulation of cytokines secretion and regulation of immune system process (Figure 2B). According to the KEGG enrichment analysis, genes were significantly enriched in tuberculosis, extracellular matrix receptor interaction and phagosome (Figure 2C). As shown in Supplementary data, Figure S2B, the PPI network was constructed using STRING.

FIGURE 2:

Identification of gene modules negatively associated with eGFR in dataset GSE30529 and GO and KEGG pathway enrichment analysis. (A) Heatmap of the correlation between MEs and clinical characters in dataset GSE30529. The MEyellowgreen was the highest negatively correlated with eGFR. (B) The top 10 terms of GO analysis of all genes in the yellowgreen module identified by WGCNA. (C) The top 10 terms of KEGG pathway analysis of all genes in the yellowgreen module identified by WGCNA. GSE30529, dataset of microarray data of microdissected tubule samples from 10 patients with DN and 12 HC ME, module eigengene. Source: Woroniecka KI, Park AS, Mohtat D et al. Transcriptome analysis of human diabetic kidney disease. Diabetes 2011;60(9):2354–69; PMID: 21 752 957.

Chemokines and chemokine receptors were identified in hub genes as potential biomarkers of DN

In glomeruli samples, 8 of the top 10 hub genes recognized by the MCC algorithm belonged to members of the chemokines or chemokine receptors (Supplementary data, Table S3), including C-C motif chemokine receptor 5 (CCR5), C-X-C motif chemokine receptor 4 (CXCR4), CCR7, C-C motif chemokine ligand 5 (CCL5, also known as RANTES), C-X-C motif chemokine ligand 8 (CXCL8), CCR2, CCR1 and C-X3-C motif chemokine receptor 1 (CX3CR1). Similarly, in tubule samples, 6 of the top 10 hub genes belonged to members of the chemokines or chemokine receptors (Supplementary data, Table S4), including CXCR4, CCR2, CX3CR1, CXCL12, CXCL1 and CXCL6.

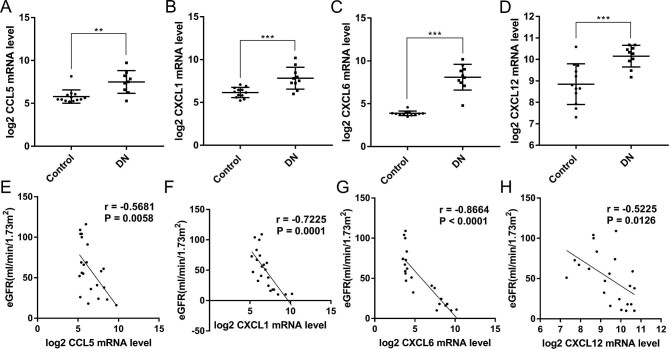

To compare the expression of chemokines screened in these two datasets, mRNA levels of CCL5, CXCL8 in GSE30528 and CXCL1, CXCL6 and CXCL12 in GSE30529 were extracted from the uploaded data. The log2-transformed mRNA level of CXCL8 was not statistically different between the two groups (Supplementary data, Figure S3). As shown in Figure 3A–D, the mRNA levels of CCL5, CXCL1, CXCL6 and CXCL12 were significantly higher in DN than in the HC group. To evaluate the potential roles of candidate chemokines in detecting the progression of DN, Pearson's correlation analysis between log2-transformed mRNA levels and eGFR were performed. As shown in Figure 3E–H, the expression levels of CCL5, CXCL1, CXCL6 and CXCL12 were negatively correlated with eGFR.

FIGURE 3:

Expression levels of candidate hub genes in DN biopsy tissues belonging to chemokines and their correlation with eGFR extracted from public datasets. (A) Expression level of CCL5 was elevated in DN glomeruli in dataset GSE30528. (B) Expression level of CXCL1 was elevated in DN tubules in dataset GSE30529. (C) Expression level of CXCL6 was elevated in DN tubules in dataset GSE30529. (D) Expression level of CXCL12 was elevated in DN tubules in dataset GSE30529. (E) Expression level of CCL5 was negatively correlated with eGFR in DN glomeruli in dataset GSE30528 (r = −0.5681, P = 0.0058). (F) Expression level of CXCL1 was negatively correlated with eGFR in DN tubules in dataset GSE30529 (r =–0.7225, P = 0.0001). (G) Expression level of CXCL6 was negatively correlated with eGFR in DN tubules in dataset GSE30529 (r = −0.8664, P < 0.0001). (H) Expression level of CXCL12 was negatively correlated with eGFR in DN tubules in dataset GSE30529 (r = −0.5225, P = 0.0126). * P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01, *** P < 0.001. Control, healthy controls. GSE30528, dataset of microarray data of microdissected glomeruli samples from 9 patients with DN and 13 HCs. GSE30529, dataset of microarray data of microdissected tubule samples from 10 patients with DN and 12 HCs. Source: Woroniecka KI, Park AS, Mohtat D et al. Transcriptome analysis of human diabetic kidney disease. Diabetes 2011;60(9):2354–69; PMID: 21 752 957.

Characteristics of subjects

A total of 212 subjects were enrolled in the study (DN, n = 91; T2DM, n = 60; HCs, n = 61). The baseline clinical, laboratory and pathological characteristics of the subjects are summarized in Table 2. There was no significant difference in sex ratios among three groups. The HCs had normal albuminuria, blood glucose levels and eGFR. Patients with T2DM were older and had higher levels of glycosylated hemoglobin than the other two groups. Patients with DN had lower levels of eGFR, plasma albumin and hemoglobin, and higher levels of albuminuria and uric acid than patients with T2DM.

Table 2.

Clinical characteristics of subjects

| Parameter | HCs | T2DM | DN | P-values |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Subjects, n | 61 | 60 | 91 | |

| Sex (M/F), n/n | 37/24 | 39/21 | 64/27 | 0.458 |

| Age (years), mean ± SD | 51.90 ± 14.84 | 58.48 ± 11.47 | 53.38 ± 11.6 | 0.005 |

| T2DM duration (months), mean ± SD | — | 109.90 ± 95.83 | 111.60 ± 75.83 | 0.908 |

| Hb (g/L), mean ± SD | 145.40 ± 14.95 | 144 ± 16.22 | 107.60 ± 19.79a,b | <0.001 |

| HbA1C (%), median (IQR) | — | 9.10 (7.40–10.50) | 7.20 (6.31–8.60) b | <0.001 |

| Alb (g/L), mean ± SD | 43.24 ± 4.45 | 39.53 ± 3.81 | 33.38 ± 6.41a,b | <0.001 |

| TC (mmol/L), mean ± SD | 4.76 ± 0.94 | 4.75 ± 1.78 | 5.11 ± 1.67 | 0.166 |

| UA (umol/L), mean ± SD | 305.20 ± 75.25 | 301.10 ± 99.40 | 361.80 ± 105.10a,b | <0.001 |

| eGFR (mL/min/1.73 m2), mean ± SD | 101.70 ± 13.85 | 99.92 ± 12.70 | 52.15 ± 31.47a,b | <0.001 |

| uACR (mg/g), median (IQR) | 10.98 (4.65–19.13) | 13.57 (7.82–22.58) | 1649 (961.20–2833) a,b | <0.001 |

| Glomerulosclerosis (%), median (IQR) | — | — | 20 (11.8–34.8) | |

| Renal interstitial fibrosis (%), median (IQR) | — | — | 30 (20–50) | |

| Relative urinary CCL5 mRNA, median (IQR) | 1 (0.902–1.223) | 1.527 (1.243–1.857) | 2.204 (1.454–3.204) a,b | <0.001 |

| Relative urinary CXCL1 mRNA, median (IQR) | 1 (0.691–1.177) | 0.972 (0.806–1.372) | 1.599 (0.649–3.310) a,b | <0.001 |

| Relative urinary CXCL6 mRNA, median (IQR) | 1 (0.628–1.213) | 0.789 (0.654–1.114) | 0.792 (0.657–1.332) | 0.623 |

| Relative urinary CXCL12 mRNA, median (IQR) | 1 (0.447–2.170) | 0.914 (0.201–1.626) | 1.063 (0.508–1.623) | 0.277 |

Hb: hemoglobin; HbA1C: glycosylated hemoglobin; Alb: albumin; TC: total cholesterol; UA: uric acid. aCompared with the HC group. bCompared with the DM group.

Urinary CCL5 and CXCL1 mRNAs were upregulated in the DN patients

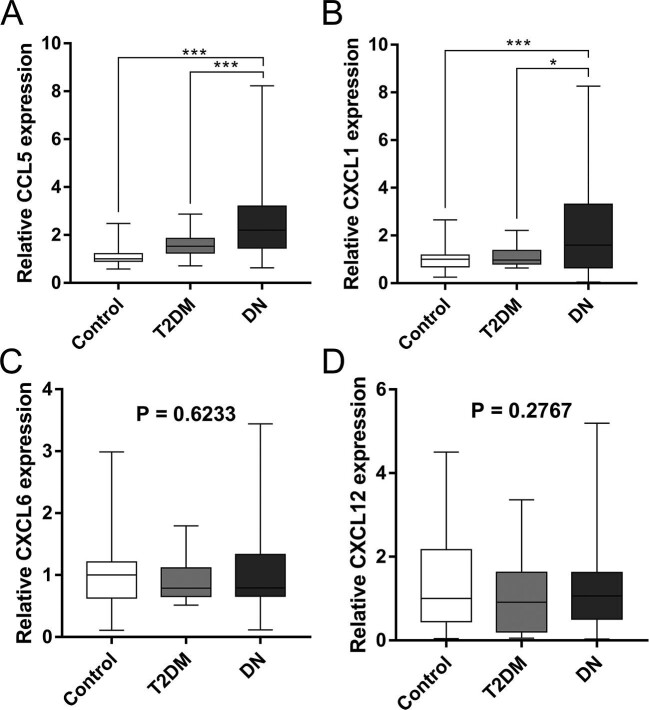

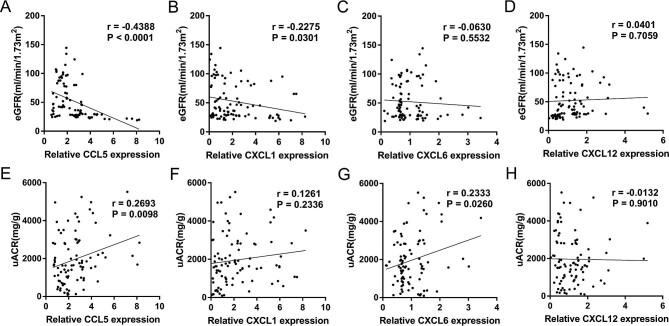

The expression levels of candidate genes (CCL5, CXCL1, CXCL6 and CXCL12) were validated in the urinary sediment in cohorts by one-step Taqman PCR assay. B2M and the four chemokines could be amplified in the samples collected from all the subjects. As shown in Table 2 and Figure 4, there was no significant difference in urinary expression of CXCL6 and CXCL12 among three groups and the expression levels of CCL5 and CXCL1 were significantly upregulated in the DN group. Furthermore, CCL5 was also positively correlated with uACR (r = 0.2693, P = 0.0098) and negatively correlated with eGFR (r = −0.4388, P < 0.0001); CXCL1 was negatively correlated with eGFR (r = −0.2275, P = 0.0301)

FIGURE 4:

Urinary relative mRNA level in subjects of validation cohorts. (A) Urinary relative mRNA level of CCL5 was elevated in DN group. (B) Urinary relative mRNA level of CXCL1 was elevated in DN group. (C) Urinary relative mRNA level of CXCL6 among three groups. (D) Urinary relative mRNA level of CXCL12 among three groups. * P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01, *** P < 0.001. Control, healthy controls.

(Figure 5). As shown in Figure 6, there was no significant difference in the expression of CCL5 and CXCL1 in different Tervaert stages of DN. In the group of severe renal interstitial fibrosis, the expression levels of urinary CCL5 (P = 0.0274) and CXCL1 (P = 0.0438) were higher than those in the mild and moderate renal interstitial fibrosis groups. There was no statistical difference for the expression levels of CXCL6 and CXCL12 in different Tervaert stages and grades of renal interstitial fibrosis (Supplementary data, Figure S4).

FIGURE 5:

Correlation of urinary relative mRNA levels with eGFR and uACR in DN group. (A) Urinary relative mRNA level of CCL5 was negatively correlated with eGFR (r = −0.4388, P < 0.0001). (B) Urinary relative mRNA level of CXCL1 was negatively correlated with eGFR (r = −0.2275, P = 0.0301). (C) Correlation of urinary relative mRNA level of CXCL6 with eGFR (r = −0.0630, P = 0.5532). (D) Correlation of urinary relative mRNA level of CXCL12 with eGFR (r = 0.0401, P = 0.7059). (E) Urinary relative mRNA level of CCL5 was correlated with uACR (r = 0.2693, P = 0.0098). (F) Correlation of urinary relative mRNA level of CXCL1 with uACR (r = 0.1261, P = 0.2336). (G) Urinary relative mRNA level of CXCL6 was correlated with uACR (r = 0.2333, P = 0.0260). (H) Correlation of urinary relative mRNA level of CXCL12 with uACR (r = −0.0132, P = 0.9010). P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

FIGURE 6:

Urinary mRNA levels of CCL5 and CXCL1 in different stages of glomerular lesion and renal interstitial fibrosis in DN group. (A) Periodic acid–Schiff staining of renal biopsy samples of DN. (B) Masson trichrome stain of renal biopsy samples of DN. (C) Urinary mRNA level of CCL5 in different stages of glomerular lesions according to Tervaert classification. (D) Urinary mRNA level of CCL5 in different degrees of renal interstitial fibrosis. (E) Urinary mRNA level of CXCL1 in different stages of glomerular lesions according to Tervaert classification. (F) Urinary mRNA level of CXCL1 in different degrees of renal interstitial fibrosis. Renal interstitial fibrosis was semi-quantitatively graded into mild (<25%), moderate (>25% but <50%) and severe (>50%). RIF: renal interstitial fibrosis. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Risk factors to ESRD

After a median follow-up of 21 months, 38 of 91 DN patients progressed to ESRD and 4 patients died from complications associated with ESRD. During the study period, six patients were lost to follow-up. Clinical parameters, histological damage and mRNA levels of candidate genes that had P-values <0.1 in univariate Cox regression analysis were entered into the prediction model. As shown in Table 3, univariate Cox regression analysis revealed that hemoglobin, glycosylated hemoglobin, albumin, eGFR, uACR, percentage of glomerulosclerosis, proportion of tubulointerstitial fibrosis and urinary mRNA level of CCL5 were selected to develop the prediction model. The results of the multivariate Cox proportional hazards regression for ESRD are presented in Table 4. eGFR [HR 0.933 (95% CI 0.885–0.983)], uACR [HR 1.000 (95% CI 1.000–1.001)], proportion of tubulointerstitial fibrosis [HR 25.804 (95% CI 2.092–318.215)] as well as urinary CCL5 mRNA expression [HR 1.350 (95% CI 1.045–1.745)] were the independent indicators of the primary endpoint.

Table 3.

Univariate Cox regression analysis for predictors of ESRD

| Variables | HR | 95% CI | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | 0.860 | 0.440–1.681 | 0.659 |

| Age (years) | 0.996 | 0.969–1.024 | 0.759 |

| T2DM duration (months) | 1.002 | 0.998–1.006 | 0.314 |

| Hb (g/L) | 0.977 | 0.961–0.993 | 0.004 |

| HbA1C (%) | 0.804 | 0.632–1.022 | 0.075 |

| Alb (g/L) | 0.953 | 0.905–1.004 | 0.068 |

| TC (mmol/L) | 0.989 | 0.816–1.199 | 0.912 |

| UA (umol/L) | 1.001 | 0.998–1.004 | 0.560 |

| eGFR (mL/min/1.73 m2) | 0.903 | 0.860–0.947 | <0.001 |

| uACR (mg/g) | 1.000 | 1.000–1.001 | <0.001 |

| Glomerulosclerosis (%) | 4.362 | 0.912–20.706 | 0.064 |

| Real interstitial fibrosis (%) | 40.725 | 12.155–136.451 | <0.001 |

| Relative urinary CCL5 mRNA | 1.461 | 1.233–1.732 | <0.001 |

| Relative urinary CXCL1 mRNA | 1.094 | 0.950–1.259 | 0.213 |

| Relative urinary CXCL6 mRNA | 1.365 | 0.824–2.260 | 0.226 |

| Relative urinary CXCL12 mRNA | 0.782 | 0.503–1.218 | 0.277 |

Hb: hemoglobin; HbA1C: glycosylated hemoglobin; Alb: albumin; TC: total cholesterol; UA: uric acid.

Table 4.

Multivariate Cox proportional hazards analysis for independent predictors of ESRD

| Variables | Hazard ratio | 95% Confidence interval | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hb (g/L) | 1.016 | 0.988–1.045 | 0.274 |

| HbA1C (%) | 1.100 | 0.830–1.458 | 0.508 |

| Alb (g/L) | 1.015 | 0.944–1.092 | 0.685 |

| eGFR (mL/min/1.73 m2) | 0.933 | 0.885–0.983 | 0.009 |

| uACR (mg/g) | 1.000 | 1.000–1.001 | 0.008 |

| Glomerulosclerosis (%) | 0.182 | 0.013–2.454 | 0.199 |

| Renal interstitial fibrosis (%) | 25.804 | 2.092–318.215 | 0.011 |

| Relative urinary CCL5 mRNA | 1.350 | 1.045–1.745 | 0.022 |

Hb: hemoglobin; HbA1C: glycosylated hemoglobin; Alb: albumin.

DISCUSSION

As an algorithm for gene co-expression network construction, WGCNA can divide the whole transcriptome into several modules according to the similarity of gene expression patterns and analyze the correlation between these modules and specific clinical characteristics. Thus it might be a powerful tool for finding the gene sets closely related to eGFR and to discover the hub genes potentially related to the progression of DN. At present there have been only a few published reports applying WGCNA in DN research. In 2012, Tang et al. [17] analyzed gene expression profiles and identified several transcription factors of DN by WGCNA. Shang et al. [18] identified three key long noncoding RNAs (NR_130 134.1, NR_038 335.1 and NR_029 395.1) and found they might play important roles in DN by regulating the biological process of inflammation and metabolism. More recently, a study using WGCNA suggested that HIF1A is involved in renal interstitial fibrosis in DN [19]. To our knowledge, biomarkers correlated with a decline in eGFR of DN identified by WGCNA have not yet been reported previously.

The pathogenesis of DN remains complex and involves numerous distinct pathways. Previous studies have proved urinary mRNAs of podocyte markers, such as nephrin and podocin, are correlated with a decline in renal function in DN [20, 21]. Furthermore, measuring the mRNA levels of podocyte markers in urine may be valuable for monitoring treatment response [22]. In the present study we analyzed the gene clusters negatively related to eGFR in microdissected glomeruli and tubules of patients with DN by WGCNA, avoiding the bias in selecting candidate biomarkers. On the one hand, through functional annotation and pathway enrichment analysis of gene modules, module genes were mainly involved in chemokine signal and inflammatory cell activation. Most of the top 10 MCC score hub genes in glomeruli and tubule samples were members of the chemokines or chemokine receptors. It suggested that chemokines may play an important role in the progression of DN. On the other hand, the candidate chemokines were identified by hub gene screening and differential expression analysis. After multicenter clinical verification by quantitative PCR, it was found that urinary CCL5 and CXCL1 were related to the decline in renal function and the degree of renal interstitial fibrosis, and CCL5 could independently predict the disease progression of DN. Our study indicated that chemokines play an important role in the progression of DN and identified urinary CCL5 mRNA as a novel prognostic biomarker for DN, providing a novel approach of systems biology to study DN biomarkers.

Traditionally, DN has long been regarded as a non-inflammatory glomerular lesion induced by hemodynamic and metabolic disorders. Increasing evidence from experimental and clinical studies has demonstrated that both systemic and

local inflammation play crucial roles in the occurrence and progression of DN [23]. Consequently, inflammatory cytokines have attracted investigators’ attention as potential biomarkers of DN. Elevated concentrations of inflammatory cytokines, including tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α and TNF receptors (TNFRs), interleukin (IL)-1, IL-18 and IL-6 have been detected in the peripheral blood of patients with DN, with some increasing with disease progression [24]. For example, numerous prospective studies have suggested a strong association between plasma TNF-R1/2 and increased risk of DN progression, including a decline in renal function, occurrence of ESRD and all-cause mortality [25–27]. Chemokines, together with their receptors, induce inflammation by promoting activation and recruitment of circulating leukocytes toward the kidney. Macrophages are considered as key inflammatory cells involved in kidney repair or fibrosis [28]. In DN patients, the interstitial infiltration of inflammatory cells, such as macrophages and lymphocytes, could be attracted by chemokines released from injured renal tissue [29]. CCL2 is one of the most widely studied chemokines in renal injury [30]. The evidence of urinary CCL2 as a potential biomarker of detecting progression [31–33] and an intervention target [34] of DN demonstrated the potential application of chemokines in clinical utility. A proteomics study of patients with T1DM or T2DM identified a panel of inflammatory signatures of kidney outcome risk, including 17 circulating inflammatory cytokines (including CCL14 and CCL15) that were associated to progression to ESRD followed for 8–13 years [35]. It also emphasized the critical roles of chemokines in the progression of DN.

In the present study, we found that the levels of CXCL1 and CCL5 in urine were increased in DN, which may be associated with the deterioration of renal function and renal interstitial fibrosis. Several reports have been published regarding the role of these two chemokines in experimental and clinical studies of DN. A previous study indicated CXCL1 was increased in glomerular podocytes of OVE, db/db and STZ-induced DM mice [36]. However, there is not sufficient evidence for the expression of CXCL1 in patients with DN. CCL5 is a potent chemoattractant for macrophages, T cells and granulocytes and is expressed by multiple cell types, including mesangial cells, fibroblasts and tubular epithelial cells in the kidney. In STZ-induced DM mice, CCL5 was increased with inflammation and fibrosis during kidney injury [37]. Moreover, upregulation of CCL5 was observed in renal biopsy tissues from patients with DN, mainly located in tubular cells, and expression of CCL5 has a positive correlation with proteinuria and interstitial inflammation [38]. Increased plasma or urinary levels of CCL5 have been reported in scattered studies in patients with T2DM and were associated with the development of microalbuminuria [39, 40]. The present study found that urinary CCL5 and CXCL1 mRNA levels could reflect the decline of renal function in patients with DN. In addition, urinary CCL5 mRNA could potentially predict the progression to ESRD. These findings would provide novel methods for assessing the prognosis of DN and warrant further clinical investigation. Some shortcomings exist in this study, such as the sample size was relatively small and the follow-up period was also short. Clearly, further studies with larger samples and a longer follow-up period to confirm the role of CCL5 mRNA in the progression of DN are needed.

CONCLUSIONS

To sum up, through WGCNA analysis, we found that numerous chemokine members might be related to the progression of DN. Through clinical verification and prospective follow-up, it was found that the expression of urinary CCL5 mRNA and CXCL1 mRNA is associated with lower eGFR and severe renal interstitial fibrosis, and urinary CCL5 mRNA could be an independent risk factor for DN progression to ESRD. This study may provide a methodological reference for identifying key molecules related to specific phenotypes in DN.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The datasets used and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to thank the contributors of the microarray and clinical data used in the bioinformatics analysis step. In addition, we thank all the clinical subjects recruited in this study.

Contributor Information

Song-Tao Feng, Institute of Nephrology, Zhongda Hospital, Southeast University School of Medicine, Nanjing, Jiangsu Province, China.

Yang Yang, Department of Nephrology, the First Affiliated Hospital of Zhengzhou University, Zhengzhou, Henan Province, China.

Jin-Fei Yang, Department of Nephrology, the Second Xiangya Hospital of Central South University, Changsha, Hunan Province, China.

Yue-Ming Gao, Institute of Nephrology, Zhongda Hospital, Southeast University School of Medicine, Nanjing, Jiangsu Province, China.

Jing-Yuan Cao, Institute of Nephrology, Zhongda Hospital, Southeast University School of Medicine, Nanjing, Jiangsu Province, China.

Zuo-Lin Li, Institute of Nephrology, Zhongda Hospital, Southeast University School of Medicine, Nanjing, Jiangsu Province, China.

Tao-Tao Tang, Institute of Nephrology, Zhongda Hospital, Southeast University School of Medicine, Nanjing, Jiangsu Province, China.

Lin-Li Lv, Institute of Nephrology, Zhongda Hospital, Southeast University School of Medicine, Nanjing, Jiangsu Province, China.

Bin Wang, Institute of Nephrology, Zhongda Hospital, Southeast University School of Medicine, Nanjing, Jiangsu Province, China.

Yi Wen, Institute of Nephrology, Zhongda Hospital, Southeast University School of Medicine, Nanjing, Jiangsu Province, China.

Lin Sun, Department of Nephrology, the Second Xiangya Hospital of Central South University, Changsha, Hunan Province, China.

Guo-Lan Xing, Department of Nephrology, the First Affiliated Hospital of Zhengzhou University, Zhengzhou, Henan Province, China.

Bi-Cheng Liu, Institute of Nephrology, Zhongda Hospital, Southeast University School of Medicine, Nanjing, Jiangsu Province, China.

FUNDING

This study was supported by grants from the National Key Research and Development Program (grant 2018YFC1314000).

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

None declared.

ETHICS APPROVAL AND CONSENT TO PARTICIPATE

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Zhongda Hospital, Southeast University (2019ZDSYLL057-P01). All of the subjects gave their written informed consent in compliance with the World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki.

REFERENCES

- 1. Alicic RZ, Rooney MT, Tuttle KR.. Diabetic kidney disease: challenges, progress, and possibilities. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2017; 12: 2032–2045 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Zhang WR, Parikh CR.. Biomarkers of acute and chronic kidney disease. Annu Rev Physiol 2019; 81: 309–333 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Colhoun HM, Marcovecchio ML.. Biomarkers of diabetic kidney disease. Diabetologia 2018; 61: 996–1011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Macisaac RJ, Jerums G.. Diabetic kidney disease with and without albuminuria. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens 2011; 20: 246–257 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Zheng M, Lv LL, Ni Jet al. . Urinary podocyte-associated mRNA profile in various stages of diabetic nephropathy. PLoS One 2011; 6: e20431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Zheng M, Lv LL, Cao YHet al. . Urinary mRNA markers of epithelial-mesenchymal transition correlate with progression of diabetic nephropathy. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2012; 76: 657–664 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Szeto CC, Chow KM, Lai KBet al. . mRNA expression of target genes in the urinary sediment as a noninvasive prognostic indicator of CKD. Am J Kidney Dis 2006; 47: 578–586 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Wang G, Lai FM, Chow KMet al. . Urinary mRNA levels of ELR-negative CXC chemokine ligand and extracellular matrix in diabetic nephropathy. Diabetes Metab Res Rev 2015; 31: 699–706 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Zhou LT, Lv LL, Qiu Set al. . Bioinformatics-based discovery of the urinary BBOX1 mRNA as a potential biomarker of diabetic kidney disease. J Transl Med 2019; 17: 59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Song ZY, Chao F, Zhuo Zet al. . Identification of hub genes in prostate cancer using robust rank aggregation and weighted gene co-expression network analysis. Aging (Albany NY) 2019; 11: 4736–4756 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Feng ST, Gao YM, Yin Det al. . Identification of lumican and fibromodulin as hub genes associated with accumulation of extracellular matrix in diabetic nephropathy. Kidney Blood Press Res 2021; 46: 275–285 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Abedini A, Zhu YO, Chatterjee Set al. . Urinary single-cell profiling captures the cellular diversity of the kidney. J Am Soc Nephrol 2021; 32: 614–627 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Woroniecka KI, Park AS, Mohtat Det al. . Transcriptome analysis of human diabetic kidney disease. Diabetes 2011; 60: 2354–2369 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. American Diabetes Association . 11. Microvascular complications and foot care: standards of medical care in diabetes-2021. Diabetes Care 2021; 44(Suppl 1): S151–S167 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Persson F, Rossing P.. Diagnosis of diabetic kidney disease: state of the art and future perspective. Kidney Int Suppl (2011) 2018; 8: 2–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Qi C, Mao X, Zhang Z, Wu H.. Classification and differential diagnosis of diabetic nephropathy. J Diabetes Res 2017; 2017: 8637138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Tang W, Gao Y, Li Y, Shi G.. Gene networks implicated in diabetic kidney disease. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci 2012; 16: 1967–1973 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Shang J, Wang S, Jiang Yet al. . Identification of key lncRNAs contributing to diabetic nephropathy by gene co-expression network analysis. Sci Rep 2019; 9: 3328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Li X, Yang S, Yan Met al. . Interstitial HIF1A induces an estimated glomerular filtration rate decline through potentiating renal fibrosis in diabetic nephropathy. Life Sci 2020; 241: 117109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Szeto CC, Lai KB, Chow KMet al. . Messenger RNA expression of glomerular podocyte markers in the urinary sediment of acquired proteinuric diseases. Clin Chim Acta 2005; 361: 182–190 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Wang G, Lai FM, Lai KB, Chow KM, Li KT, Szeto CC.. Messenger RNA expression of podocyte-associated molecules in the urinary sediment of patients with diabetic nephropathy. Nephron Clin Pract 2007; 106: c169–c179 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Wang G, Lai FM, Lai KBet al. . Urinary messenger RNA expression of podocyte-associated molecules in patients with diabetic nephropathy treated by angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor and angiotensin receptor blocker. Eur J Endocrinol 2008; 158: 317–322 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Tang SCW, Yiu WH.. Innate immunity in diabetic kidney disease. Nat Rev Nephrol 2020; 16: 206–222 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Perlman AS, Chevalier JM, Wilkinson Pet al. . Serum inflammatory and immune mediators are elevated in early stage diabetic nephropathy. Ann Clin Lab Sci 2015; 45: 256–263 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Saulnier PJ, Gand E, Ragot Set al. . Association of serum concentration of TNFR1 with all-cause mortality in patients with type 2 diabetes and chronic kidney disease: follow-up of the SURDIAGENE cohort. Diabetes Care 2014; 37: 1425–1431 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Bhatraju PK, Zelnick LR, Shlipak M, Katz R, Kestenbaum B.. Association of soluble TNFR-1 concentrations with long-term decline in kidney function: the multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis. J Am Soc Nephrol 2018; 29: 2713–2721 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Niewczas MA, Gohda T, Skupien Jet al. . Circulating TNF receptors 1 and 2 predict ESRD in type 2 diabetes. J Am Soc Nephrol 2012; 23: 507–515 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Lv LL, Feng Y, Wen Yet al. . Exosomal CCL2 from tubular epithelial cells is critical for albumin-induced tubulointerstitial inflammation. J Am Soc Nephrol 2018; 29: 919–935 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Feng Y, Zhong X, Ni HFet al. . Urinary small extracellular vesicles derived CCL21 mRNA as biomarker linked with pathogenesis for diabetic nephropathy. J Transl Med 2021; 19: 355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Liu BC, Tang TT, Lv LLet al. . Renal tubule injury: a driving force toward chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int 2018; 93: 568–579 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Shoukry A, Bdeer Sel A, El-Sokkary RH. Urinary monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 and vitamin D-binding protein as biomarkers for early detection of diabetic nephropathy in type 2 diabetes mellitus. Mol Cell Biochem 2015; 408: 25–35 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Satirapoj B, Dispan R, Radinahamed Pet al. . Urinary epidermal growth factor, monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 or their ratio as predictors for rapid loss of renal function in type 2 diabetic patients with diabetic kidney disease. BMC Nephrol 2018; 19: 246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Wada T, Furuichi K, Sakai Net al. . Up-regulation of monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 in tubulointerstitial lesions of human diabetic nephropathy. Kidney Int 2000; 58: 1492–1499 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Kanamori H, Matsubara T, Mima Aet al. . Inhibition of MCP-1/CCR2 pathway ameliorates the development of diabetic nephropathy. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2007; 360: 772–777 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Niewczas MA, Pavkov ME, Skupien Jet al. . A signature of circulating inflammatory proteins and development of end-stage renal disease in diabetes. Nat Med 2019; 25: 805–813 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Xu J, Zheng S, Kralik PMet al. . Diabetes induced changes in podocyte morphology and gene expression evaluated using GFP transgenic podocytes. Int J Biol Sci 2016; 12: 210–218 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Norlin J, Nielsen Fink L, Helding Kvist Pet al. . Abatacept treatment does not preserve renal function in the streptozocin-induced model of diabetic nephropathy. PLoS One 2016; 11: e0152315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Mezzano S, Aros C, Droguett Aet al. . NF-κB activation and overexpression of regulated genes in human diabetic nephropathy. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2004; 19: 2505–2512 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Cherney DZ, Scholey JW, Daneman Det al. . Urinary markers of renal inflammation in adolescents with type 1 diabetes mellitus and normoalbuminuria. Diabet Med 2012; 29: 1297–1302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Wu CC, Chen JS, Lu KCet al. . Aberrant cytokines/chemokines production correlate with proteinuria in patients with overt diabetic nephropathy. Clin Chim Acta 2010; 411: 700–704 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.