Introduction

Protein glycosylation is a highly prevalent post-translational modification involving the attachment of oligosaccharides, most commonly to a serine/threonine residue (O-linked glycosylation) or an asparagine residue (N-linked glycosylation). Glycosylation is a highly regulated process with over 300 enzymes involved in their biosynthesis and processing in a non-template driven manner. This is done by a series of sequential reactions involving a wide array of glycotransferases that attach single monosaccharides from nucleotide sugar donors, as well as different glycosidases that remove individual monosaccharides.1 The expression, activity, and localization of these enzymes are sensitive to the physiological state of the cell. Estimated to occur on over half of human proteins,2 N-linked glycosylation has essential roles in protein folding, molecular trafficking, signal transduction, cell-cell interactions, and many other processes.3-6 Glycans serve as one of the initial points of contact during cell to cell interactions, so therefore disease changes in glycan biosynthesis can be more apparent than disease related changes associated with gene mutations and proteins.7 Alterations in N-linked glycosylation have been found in a variety of diseases, including but not limited to cancer,8 inflammatory arthritis,9 liver fibrosis/cirrhosis,10 schizophrenia,11 type 2 diabetes,12 ischemic stroke,13 and Parkinson’s disease.14 Particularly for cancers, the majority of FDA-approved cancer biomarkers are comprised of circulating glycoproteins or carbohydrate antigens for measurement in blood.7,8,15-18 Glycoproteins can be ideal biomarkers because they enter circulation from tissues or blood cells through active secretion or leakage, making them assessable for analysis through serum. These current biomarker targets, for example prostate specific antigen or the carbohydrate antigen CA19-9, are far from ideal and have many limitations due to specificity and other factors.17

There are many analytical approaches that have been applied to the analysis of disease associated changes in the glycan constituents of glycoproteins in tissues biofluids. Reviews highlighting some of these methods are as follows, and include use of carbohydrate binding lectins,19,20 anti-carbohydrate antigen antibodies,21 glycan microarrays,22 HPLC and mass spectrometry.23-27 Historically, there have been persistent challenges across all glycan analysis methods related to generally poor affinities of antibodies for carbohydrate epitopes, weak and non-specific binding affinities of lectins, distinguishing isomeric species, and issues of extensive sample processing for HPLC and mass spectrometry. The aforementioned reviews highlight progress in these areas, and the field in general is moving toward development of potential clinical and diagnostic assay workflows. Our group has recently developed several glycan targeted assays using imaging mass spectrometry (IMS) approaches,28-33 including extensive detailed protocols.34,35 Originally developed for spatial analysis of N-glycans in tissues,28-30 different adaptations of the approach have been developed for analysis of N-glycans of biofluids,31 cells,32 and captured proteins33 directly on glass slides. These approaches are distinguished by their overall throughput, ease and speed of preparation, and robustness. Using mass spectrometers equipped with matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization (MALDI) sources for these assays, the consistent and reproducible detection of N-glycan structures in clinical samples has the potential to mature into clinical assays analogous to the MALDI MS-based assays that have transformed clinical microbiology identification of bacterial and other pathogen species.36,37 The workflows, strengths, limitations, and clinical implications of using MALDI IMS N-glycan analysis will be discussed with examples for the analysis of tissues, clinical biofluids, cultured cells, and immunoarray captured glycoproteins.

Method Overview and Applications of N-Glycan MALDI-IMS of Tissues

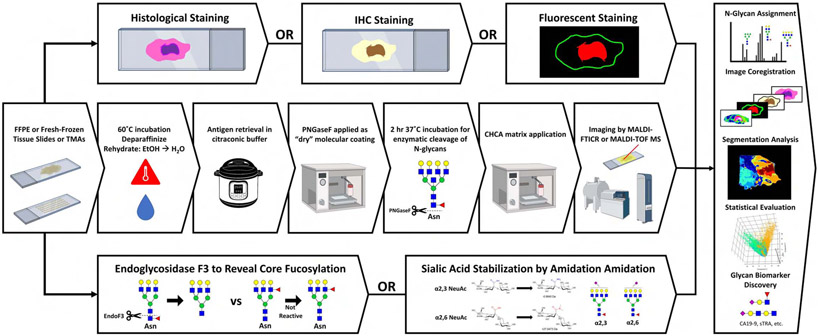

MALDI-IMS analysis of proteins in tissues was initially described in 1997 by the Caprioli laboratory,38 and the field has rapidly evolved to facilitate the spatial distribution and identification of all classes of biomolecules using multiple types of mass spectrometers and ionization sources.39-41 Key to the success of MALDI-IMS in identification of disease-specific biomolecules has been the ability to correlate imaging mass spectrometry data with histopathological classification of tissue subtypes by standard histology and immunohistochemistry stains.42,43 Specific application of N-glycan targeted MALDI-IMS was reported initially in fresh frozen tissues in 2013, followed a year later in formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tissue sections.28-30 The method workflow is summarized in the schematic shown in Figure 1. The key to the approach is to spray a molecular coating of peptide N-glycosidase F (PNGase F) on the tissue, an enzyme that will cleave the N-linked glycan structures at their site of attachment to an asparagine residue on the glycoprotein carrier. The released N-glycans are detected in the mass spectrometer after application of an organic acid matrix and ionization by laser desorption, using a rastered grid of locations generally 40 to 100 microns apart across the entire tissue. A two-dimensional distribution map of the peak intensities of each released glycan is generated by analysis of the cumulative spectra obtained from each spot on the tissue. Use of a solvent sprayer has allowed robust and reproducible sample preparatory workflows to evolve that facilitates large scale analysis of clinical tissue cohorts.28,44 This basic workflow has been used by multiple laboratories to characterize the N-glycan distributions for multiple cancer types including breast,45-47 prostate,48,49 liver,48,50 pancreas,29,51 ovary,52 colon,30,53 sarcoma,54,55 kidney,43 and lung56 as well as in cardiac57,58 and other tissue types.43,45,46,50,57,59,60 An example MALDI-IMS N-glycan image of a human colorectal adenocarcinoma tissue is shown in Figure 2. This example clearly illustrates the histopathological co-localization of specific glycans to different regions of the tissue, including tumor and adjacent normal crypt, stroma and smooth muscle regions. The overlay and single glycan images shown are representative of over 100 distinct glycan species that can be detected in this tissue.

Figure 1.

Overview of MALDI-IMS workflow and orthogonal analyses. Middle row: A standardized N-glycan IMS workflow including dewaxing and rehydration, antigen retrieval, release of N-glycans by PNGase F, matrix application and imaging by MALDI-MS. Bottom row: Endoglycosidase F3 and sialic acid-amidation adaptations to the N-glycan IMS workflow for detection of fucosylation and sialylation isomers, respectively. Top row: Orthogonal imaging techniques including histological, immunohistochemistry and immunofluorescence staining. Panel, right side: Integration of data from traditional, adapted, and orthogonal analyses for comprehensive characterization of the tissue N-glycome.

Figure 2.

Example N-glycan imaging mass spectrometry of a colorectal adenocarcinoma tissue. A) H&E staining showing different tissue structures. B) Overlay image of six N-glycan structures which colocalize with distinct tissue regions. C-H) Individual N-glycan heatmaps from overlay in panel B Hex8HexNAc2 (red), Hex4HexNAc4Fuc2 (yellow), Hex4HexNAc5Fuc1 (purple), Hex5HexNAc4α2,6NeuAc1 (blue), Hex5HexNAc4Fuc1α2,3NeuAc1 (green) and Hex7HexNAc6Fuc1α2,6NeuAc1 (orange). Monosaccharide unit symbols: mannose (green circle), galactose (yellow circle), N-acetylglucosamine (blue square), fucose (red triangle), α2,3-linked sialic acid (purple diamond, right shifted) α2,6-linked sialic acid (purple diamond, left shifted).

Based on thousands of analyses of individual FFPE tumor tissue slides and tumor cores in tissue microarray slides, several advantages to N-glycan MALDI-IMS are evident relative to other MALDI-IMS targets. A major advantage in regard to clinical translation is the ability to perform these analyses on FFPE tissues, thereby leveraging the predominant specimen type found in clinical histopathology labs and tissue biorepositories. The MALDI IMS workflow fits seamlessly into the pathology lab, as it uses the same tissue sections required for pathological evaluation without additional patient interactions. Similarly, the processing steps for the method prior to PNGase F application are essentially the same as standard histology practices for tissue staining and IHC (Figure 1). Because the N-glycans lack free amine groups and are thus not cross-linked by formalin, it has been shown that only dewaxing but not antigen retrieval can be used effectively to obtain glycan signals.54,61 For analytical considerations using the basic workflow, the released glycans are detected directly from the tissue without need of enrichment or derivatization. The glycans detected are entirely dependent on the activity of the PNGase F, thus any background signal due to tissue is minimal. The use of the automated solvent sprayer to apply a reproducible thin molecular coating of PNGase F ensures minimal diffusion and excellent co-localization of glycans to their site of origin.34 Lastly, because of the sequential nature of their biosynthesis, the basic structural compositions of the N-glycans that can arise are known and well documented.3,30 For MALDI-IMS, this results in highly reproducible detection of a core number of ~ 40 N-glycan species in normal and tumor tissues that can be used for basic biostatistical comparisons across conditions. These glycans also serve as the scaffolds for disease associated increases in sialic acid and fucose modifications resulting from expression of different genes in the fucosyltransferase and sialyltransferase families. Some tumor types also are characterized by increases in glycans with bisecting N-acetylglucosamine structures and poly-lactosamine extensions.46,62 Thus in cancer tissues, like that shown in Figure 2, the numbers of N-glycans detected generally increase in proportion to pathology grade and tumor stage. The masses of these added sugars are also well defined, therefore determinations of the structural compositions of these larger N-glycans are straightforward. This type of data is essentially a glycan bar code that can be applied to clinical cohorts for biostatistical analysis and biomarker studies, described more in a different section.

Limitations and Method Adaptations for N-Glycan MALDI-IMS

There are several limitations of N-glycan IMS that are inherent to the properties of N-glycans, as well as instrumentation and method ones that are related to use of MALDI as the ionization source. These include differentiating structural isomers, stability of sialic acid glycans to MALDI ionization, suppression of N-glycan signal due to matrix effects, the detection of glycans with masses above m/z = 4000, and decreased sensitivity with increased spatial resolution. Strategies used to overcome these limitations, along with other potential approaches are summarized as follows.

There are many structural isomers that can arise from the sequential addition of sugars in N-glycans. Notably, there are 13 fucosyltransferase genes that encode a family of enzymes responsible for the addition of fucose to N-glycan structures. Outer arm fucose residues, i.e. those attached to sugars on the branched antennae, are primarily attached via either α-1,2 (FUT1,2) or α-1,3 and α-1,4 (FUT3,4,6,7,9-11) linkages, Core fucosylation at the terminal N-acetylglucosamine residue attached to the Asn of the protein is done exclusively by FUT8, with an α-1,6 linkage.63 For sialic acids, two main glycosyltransferases ST3Gal1 and ST6Gal1, from a gene family of more than 15 sialyltransferases, are responsible for the addition of α-2,3 or α-2,6 linked sialic acids to the terminal galactose moieties on branched N-glycans.64 The presence or absence of these different fucose and sialic acid linkages is largely dependent on the specific gene expression patterns in each tissue and cell type, as well as disease state, thus each tissue analyzed by MALDI-IMS has many possible glycans that could be present. Distinguishing these structural isomers has always been a challenge for mass spectrometry analysis of N-glycans, and especially for MALDI-MS approaches. While accurate masses and glycan compositions can be readily determined, the specific antennae location and anomeric linkages associated with fucose and sialic acid modifications are difficult to establish. Recently, several enzymatic and chemical adaptations to the standard workflow have been developed to solve some of the difficulties associated with detection of fucosylation and sialylation isomers (Figure 1). The distinction between core or terminal fucosylation is important to determine, as increases in core fucosylation are associated with more aggressive cancer phenotypes and poorer patient outcomes.50,65-67 Recently, a new enzyme has been incorporated into the N-glycan MALDI-IMS workflow. Termed endoglycosidase F3 (Endo F3), this enzyme specifically cleaves N-glycans with core fucose residues, between the two N-acetylglucosamine residues on the N-glycan chitobiose core in the presence of a core fucose residue (see Figure 1). This results in a mass shift of 349 m.u. to the released N-glycan, representing the loss of one N-acetylglucosamine and one fucose.48 N-glycans lacking a core fucose are poor substrates for this enzyme. Subsequently, incorporation of this enzyme into N-glycan IMS strategies resolves core versus outer arm fucosylation isomers.48 Using Endo F3 and PNGase F in a 1:10 ratio can free both core and terminally fucosylated N-glycan isomers in a single tissue analysis. Distinguishing the isomeric linkages of α-2,3 versus α-2,6 sialic acid residues on N-glycans is further complicated by the lability of sialic acid residues during MALDI ionization, as well as by the fact that the negative charge of sialic acids typically forms salt adducts with additional sodium ions, reducing sensitivity of detection.68,69 To overcome these challenges, an on-tissue chemical amidation approach has been developed which stabilizes sialic acid residues prior to preparation for MALDI-IMS.53 Critically, in addition to stabilization, this method differentially derivatizes α-2,3 and α-2,6 linked sialic acid N-glycans with stable amide and dimethylamide groups, respectively. This disparate incorporation induces a distinct mass shifts in sialylated N-glycans which allows for the specific detection of α-2,3 versus α-2,6 isomers in IMS-derived data. Examples of these anomeric differences are also shown in the data for the colorectal tumor in Figure 2.

Common to all types of MALDI-MS and MALDI-IMS is the blunting of analyte signal due to interference by the chemical matrix. The laser desorption process and subsequent transfer of analytes into the gas phase fragments the matrix and results in the ejection of matrix ions into the mass spectrometer alongside N-glycan ions. These additional m/z peaks detected complicate the analysis of MALDI-generated mass spectra and may lead to overall signal suppression and potential obfuscation of N-glycan peaks, especially those of lower molecular weight or lower intensities. These challenges are currently being overcome by several approaches. Simplest amongst them is the incorporation of ammonium salts (acetate, formate or phosphate)70,71 either as a matrix solution component or as a post-matrix application spray, into the MALDI-IMS workflow.70 Ammonium salts helps prevent the formation of matrix adducts thereby breaking up the larger matrix crystal clusters which differentially absorb laser energy and lead to signal suppression.72-74 Recently, a strategy to reduce matrix interference specific to N-glycan MALDI-MS has been developed. The use of a modified reactive DHB (DHBH) in combination with catalytic DHB allows for the simultaneous derivatization of cleaved N-glycans and co-crystallization of these analytes with this novel matrix mixture.75 Subsequently, this workflow modification has shown utility not only in the reduction of matrix interference but also in the boosting of N-glycan signal and the quantification of these species.

Mammalian N-glycans are known to range in molecular weight from m/z 933 (the common Hex3HexNAc2 N-glycan core) to over 10,000 m/z for very large polylactosamine-containing structures. The analysis of such higher molecular weight N-glycan structures is typically difficult via traditional MALDI-IMS workflows, which even when optimized for increased signal from the upper m/z range struggle to reliably detect masses greater than 5000 m/z. Here again, multiple strategies are available to address this shortcoming. Chemical derivatization of tissue homogenate followed by MALDI-TOF detection and N-glycan identification via a matched filtering algorithm analysis recently allowed for the identification of polylactosamine N-glycan ions up to ~14,000 m/z.76 Also, a novel instrumentation approach may soon be able to overcome this obstacle. Laser positronization-coupled MALDI-IMS (MALDI-2) utilizes a secondary laser source to further ionize the analyte plume ejected by the primary laser.77 In doing so, low abundance and hard to detect ions receive a signal boost and are therefore detected more robustly. Because this second laser ionizes the analyte cloud as a whole, it has the potential to increase signal across the entire mass range. The aforementioned methods to address glycan isomer determinations begin to unravel some of the major glycan isomer challenges, but not all. There remain other challenges associated with distinguishing modifications like terminal N-acetylglucosamine residues versus bisecting N-acetylglucosamine, as well as determining which antennae branch is modified. The recent introduction of trapped ion mobility separated time of flight MS (timsTOF) instruments into the MALDI-IMS space helps to deconvolute this complexity.78,79 Structural isomers from an ion packet of the same m/z migrate through an electric field in a manner proportional to their structural geometry, allowing for high resolving power and very fine discrimination of structures which are compositionally the same but differ in their precise linkages. This technology has already demonstrated utility in parsing out N-glycan isomers.80

Although the breadth of detectable molecular information in imaging mass spectrometry can identify many analytes, the routine image resolution obtained at the tissue and cell levels is at the 20 micron level and higher. Other imaging modalities like fluorescent microscopy and super resolution microscopy (SRM),81 as well as alternative imaging mass spectrometry methods like TOF-SIMS and MIBI-TOF41,82-84 allow for imaging of analytes at sub-micron resolution. This level of resolution is not currently achievable using standard MALDI-IMS. Advances in MALDI-IMS platforms, such as transmission geometry MALDI-IMS, and associated methodologies have progressively increased spatial resolution, but at the cost of signal intensity.85 To achieve cellular or sub-cellular resolutions in imaging mass spectrometry, the typically large laser pixel size (~25 μm) must be reduced. In doing so the amount of laser energy directed at the tissue in a single shot necessarily decreases, resulting in the detection of fewer analytes and an overall reduction in signal strength.83 This trade-off is potentially addressed by the above mentioned MALDI-2, which can compensate for this loss of molecular information through increasing signal post desorption, and has demonstrated a pixel size as low as 600 nm.86 It is yet to be determined if single micron resolution capabilities are necessary to improve current N-glycan MALDI-IMS data, particularly in the context of clinical assay development.

Emerging Uses of N-Glycan MALDI-IMS for Cancer Tissue Biomarkers and Diagnostics

In our group, the use of tissue microarrays (TMA) representing liver, kidney, pancreas and breast cancers in conjunction with whole tissue slices have allowed larger cohorts of samples to be analyzed.29,36,51,59 The resulting glycan peak lists can be combined with clinical patient data, pathology and genetic sub-typing information to evaluate detection of glycan changes as potential diagnostic biomarkers. For breast cancer, an initial study evaluated TMAs representing Her2+ and triple negative (TNBC) breast cancer subtypes.46 There were minor differences in glycan metabolism, with Her2+ tumors having higher levels of tri- and tetra-antennary precursors relative to TNBC, while TNBC tumors had higher levels of high mannose N-glycans. A more striking finding was the detection of N-glycans with poly-lactosamine extensions in the most aggressive tumor cores of Her2+ and TNBC, as well as in a cohort of metastatic and primary tumor tissue pairs. The ability to detect these poly-lactosamine N-glycans in the most advanced breast tumors was further evaluated in a tissue microarray of 145 breast tumor cores, primarily representing intraductal ductal carcinomas, with outcome and survival data.47 Analysis of the resulting N-glycan peak lists indicated that the presence of core-fucosylated tetra-antennary N-glycan with a single N-acetyllactosamine extension indicated tissues associated with poor outcome, including lymph node metastasis, recurrent disease and reduced survival. The presence of core fucose was confirmed using EndoF3. We hypothesize that this approach could be applied to diagnostic biopsy and/or primary resection tissues to improve identification of women with more lethal forms of breast cancers.

Another example is the use of N-glycans detected in TMAs from hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) tissue to predict survival outcomes. From an N-glycan imaging analysis of 138 tumor cores and whole tissues, there were ten N-glycans identified as significantly elevated relative to normal or cirrhotic liver tissues. These tumor glycans primarily had increased levels of fucosylation. There was also a distinct subset of tumors with a primary tetra-antennary branched glycan as the main difference. In one subset, a non-fucosylated structure (Hex7HexNAc6) predominated, and the other subset had mono and di-fucosylated versions (Hex7HexNAc6Fuc1/2). The tumors associated with the fucosylated glycans had poorer outcomes and decreased survival times relative to the samples with the non-fucosylated glycan. A follow-up study using EndoF3 digestion of the same TMAs, further indicated that for the mono- and di-fucosylated glycans, those that were core fucosylated had worse survival times than those without.48 The demonstration that core fucosylated N-glycans in HCC tissues is associated with poorer outcomes is consistent with many previous studies reporting overall increases in core fucosylation for HCC.50,59,66,67,87-90 Current efforts are focused on applying the same N-glycan MALDI-IMS workflows to a large cohort of genetically subtyped HCC tumors (S1,S2,S3) that are correlated with clinical parameters such as tumor size, extent of cellular differentiation, serum alpha-fetoprotein levels, signaling pathways, treatment responses and outcomes.91,92 Similar strategies are ongoing to link established cancer biomarkers and other clinical correlates with N-glycans from prostate and pancreatic cancer tissue cohorts, including 3D strategies and linkage for prostate with clinical MRI co-registrations.49

N-Glycan IMS of Clinical Biofluids

Blood-based samples are attractive mediums for biomarker detection due to the availability of large clinical cohorts, as well as the cost-effective and minimally invasive manner of collection. While there have been several MALDI-MS strategies developed for analysis of N-glycan profiles in biofluids, there are a limited number of high-throughput methodologies capable of analyzing the current-day clinical cohorts that commonly contain thousands of samples. One of the largest plasma N-glycan studies analyzed over 2144 individuals by MALDI-MS to identify associations of plasma N-glycans with markers of inflammation and metabolic health.93 The MALDI-MS workflow involved the release of N-glycans with PNGase F, sialic acid stabilization by ethyl esterification, purification by hydrophilic interaction liquid chromatography (HILIC), incorporation of chemical matrix, and spotting onto a MALDI target plate, with many of the steps completed with an automated liquid handling robot.94 This workflow would be further optimized by limiting derivatization side-reactions, decreasing batch-to-batch variances by changing the HILIC stationary phase, and using MALDI-FTICR instead of MALDI-TOF.95 A non-automated form of this workflow was adapted for dried blood spot N-glycan analysis, which represents an even less-invasive collection strategy.96 These strategies have been used to investigate a wide array of diseases, including multiple myeloma,97 inflammatory bowel disease,98 rheumatoid arthritis,24 and colorectal cancer.99 These extensive studies on large sample cohorts have established N-glycan detection in plasma by MALDI-IMS as a clinically relevant assay for us in clinical diagnostic laboratories.

Another method for serum N-glycan analysis utilizes an enrichment strategy termed glycoblotting, in which beads conjugated with hydrazide groups bind N-glycans released from serum samples.100 Not only are the bead-bound N-glycans purified with a series of washes, but the sialic acids are stabilized by methyl esterification. The hydrazide groups with attached N-glycans are released from the bead by reduction with dithiothreitol. The enriched N-glycans are spotted directly onto a MALDI target plate, mixed with matrix, and analyzed by MALDI-TOF MS. The processing time of this workflow was reduced when combined with an automated sample-processing system that can carry out the majority of the steps.101 Glycoblotting-based serum analysis has been used extensively to find many disease-specific N-glycan alterations.102-107 The clinical utility of this workflow is distinguished by the minimal hands-on-time.

Recently, Blaschke and colleagues developed a rapid high-throughput IMS workflow for serum and plasma N-glycan profiling.31 In this workflow, serum or plasma is spotted on an amine-reactive hydrogel coated slide resulting in the covalent binding of proteins to the slide during a 1-hour incubation in a humidity chamber. It is well known that lipids and salts will suppress the N-glycan signal during IMS. Accordingly, samples are delipidated with washes of Carnoy’s solution (60% ethanol, 30% chloroform, 10% glacial acetic acid), and desalted with a water wash. The rest of the workflow follows the tissue processing steps shown in Figure 1. The slide is sprayed with PNGase F, incubated for 2 hours, and sprayed with matrix. The sample processing time is significantly decreased by avoiding lengthy derivatization and purification steps typically found in clinical biofluid N-glycan profiling methods. A slide with 28 samples can be processed and imaged in less than 11 hours on an FT-ICR instrument. Multiple slides can be processed together to increase throughput with minimal additional time requirements, and other MS instruments can be used for quicker MS data acquisition. This workflow can detect 75 N-glycans from less than one microliter of serum or plasma. The simplicity, speed, and sensitivity of this method make it highly amenable for use as a clinical assay.

Shown in Figure 3 is example data for detection of 6 N-glycans detected from the serum of a patient with liver cirrhosis and a patient with hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). Alterations in the glycosylation of glycoproteins found in tissue and serum during the development of HCC have been well documented.87,90,108,109 For example, increased fucosylation of bi, tri and tetra-antennary glycans have been found in several studies.50,59,66,67,87-90 Consistent with this, fucosylated bi-antennary N-glycans were detected at higher levels in the HCC sample relative to the cirrhotic sample. Analysis of larger clinical patient sample cohorts is ongoing, as well as strategies for automated sample spotting and processing.

Figure 3.

Profiling of 6 N-glycans from the serum of patients with either liver cirrhosis or hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) using the method described by Blaschke and colleagues.31 Monosaccharide unit symbols are as indicated in Figure 2.

N-Glycan IMS of Cultured Cells

While liquid chromatography coupled to mass spectrometry (LC-MS) is the most common technique for analyzing the N-glycan profile of cells,110,111 Angel and colleagues utilized MALDI IMS to create an alternative method that is rapid and robust.32 In this novel method, cells are cultured on a conventional cell culture chamber slide array, fixated with neutral buffered formalin, and delipidated with Carnoy’s solution. Subsequent steps mirror the tissue imaging workflow, except for a few minor alterations. Compared to tissue, this cell imaging method had the greatest sensitivity by applying less PNGase F and matrix. Additionally, ammonium phosphate monobasic (AP) was sprayed on to the slide after the matrix application to minimize the formation of signal-suppressing matrix-clusters. Signal detected from N-glycans in the serum-containing media was found to be highly reproducible and could be subtracted out as background. The arrays can be normalized for cellular protein levels by incorporating a traditional protein-binding stain, Coomassie G-250, after MS data acquisition. With this simple workflow, 88 cell chambers can be N-glycan profiled within 1 day, including overnight MS analysis, with minimal hands-on time. This represents a vast improvement compared to the lengthy sample processing steps needed when using LC-MS.

Utilizing this method, Angel and colleagues were able to reproducibly detect 70 N-glycoforms from as few as in a variety of human and mouse cell lines. The N-glycan profiles contained a variety of N-glycan structures, including high-mannose and fucose and sialic acid containing bi-, tri-, and tetra-antennary N-glycans. As discussed, N-glycans have important roles in cell signaling and require precise regulation. With no additional processing time, N-glycan turnover could be detected by integrating an isotopic detection of aminosugars with glutamine (IDAWG) labeling approach (Figure 4). The incorporation of 15N amide glutamine into all N-acetylglucosamine, N-acetylgalactosamine, and sialic acids creates a distinct mass shift in all newly synthesized N-glycans. As illustrated in Figure 4 at near single cell resolution, turnover rates of individual N-glycans can be determined by comparing the intensities of the unlabeled and labeled forms over several time points. The rapid and robust array-based MALDI-IMS approach is an innovative solution to the analytical challenge of glycomic studies in cultured cells and serves as a foundational launching point for basic, translational, and pharmaceutical investigations into mechanisms of N-glycan function and regulation in cultured cells.

Figure 4.

N-glycan turnover in cell culture by imaging MS strategies. Human aortic endothelial cells are grown in 15N glutamine for 48 hours, adding an 15N at every N-acetylglucosamine, N-acetylgalactose, and N-acetylneuraminic acid. Fully labeled N-glycans with complete incorporation of 15N indicate a complete turnover of that N-glycan. A) Human aortic endothelial cells are grown with 15N glutamine on a conventional cell chamber slide. This image shows cells that have been stained after IMS analysis with Coomassie Blue to allow normalization to cell numbers & protein content. B) Example image data of the same region of cultured cells. Image is of high mannose N-glycan Man9. Cells were scanned at a step size of 25 μm. Blue indicates no turnover, yellow indicates full turnover, white is partial incorporation of the label, indicating a slower turnover rate for some cells (red arrows). C) Example N-glycan profile showing the high mannose peak Man9. Monosaccharide unit symbols are as indicated in Figure 2.

N-Glycan IMS of Immunoarray Captured Glycoproteins

Recently developed immunoassays modified for glycosylation analysis of isolated glycoproteins have the potential for robust analysis of large cohorts of clinical samples. Disease associated alterations in the glycosylation of immunoglobulin G (IgG),112 α1-acid glycoprotein (AGP),113 haptoglobin,114 transferrin,115 and α-fetoprotein (AFP)108 have been demonstrated and could have utility as biomarkers. There have been several methods for high-throughput N-glycan analysis of immunocaptured glycoproteins utilizing lectin microarrays to identify carbohydrate structural motifs.116,117 Essentially, these techniques work like the common ELISA technique where the a protein of interest is captured by an antibody and analyzed with multiple lectins. While the large number of different lectins can cover a wide range of glycan structures, the low binding affinities and undefined specificities of most lectins limit their utility for analysis of clinical cohorts. Additionally, lectins are unable to determine the entire composition or type of the bound glycan.

These limitations can be mitigated by a mass spectrometry-based approach. Darebna and colleagues developed a method for detecting altered glycoforms of transferrin that are characteristic of heavy alcohol abuse using MALDI IMS.118 The workflow includes electrospraying antitransferrin antibody on to an indium tin oxide glass slides, capturing transferrin from serum, washing the slide, and applying matrix. The glycoforms of transferrin have distinct masses that can be detected by MALDI-TOF MS. The peak intensities of the glycoforms were compared between healthy and alcoholic patient serum samples. This immunoassay approach avoids the previously discussed limitations of lectin microarrays and the lengthy sample cleanup necessary for traditional protein glycosylation techniques.

Black and colleagues expanded and adapted the immunoarray approach for glycoprotein analysis with the development of antibody panel based (APB) N-glycan imaging.33,35 In this novel technique, antibodies are spotted onto a microscope slide in an array, glycoproteins are specifically captured from patient biofluids, and N-glycans are enzymatically released for analysis by MALDI IMS. The multiplexing of antibodies can be used to analyze the intensities of 100s of glycans from 100s of glycoproteins from 1 μl of serum in a single imaging run. This method only requires 8 hours of hands-on time and has the possibility of being automated with a liquid handling robot. To ensure N-glycan changes are not due to varying protein levels, a saturating amount of protein must be added to the antibody array. This technique relies on the binding affinity and specificity of the antibodies and requires validation of each antibody used. Figure 5 illustrates representative APB N-glycan imaging data obtained from serum analysis of 7 glycoproteins simultaneously. Antibody panel based (APB) N-glycan imaging improves the sensitivity and simplicity of glycoprotein analysis in a manner suitable for robust analysis of large clinical cohorts.

Figure 5.

Antibody panel based imaging of 3 N-glycans for 7 glycoproteins captured from a pool of serum collected from patients with liver cirrhosis using the method described by Black and colleagues.33 Monosaccharide unit symbols are as indicated in Figure 2. A1AT = alpha-1-antitrypsin, Hapto = haptoglobin, Hemo = hemoglobin, IgG = Immunoglobulin G, LMWK = low-molecular-weight kininogen, Trans = transferrin, AGP = alpha-1-acid glycoprotein.

Future Directions

For each of the indicated applications, multiple steps in the workflow can be optimized to move toward clinical assay implementation. Glycan profiling of biopsy tissues in particular, like those frequently obtained for liver, prostate and breast cancer assessments, or kidney for diabetes, could be integrated with current pathology practices. A recent report described a rapid MALDI-IMS analysis workflow for frozen tissues that required only ~ 5 total minutes of preparation and analysis time integrated into a pathology lab setting.119 It is unlikely that this timeline could be adapted directly to N-glycan IMS workflows, as the PNGase F digestion step is required, but it is feasible to incorporate components of the method optimization strategies that were reported. The optimized tissue imaging workflows are also applicable to multimodal IMS combinations with other glycosidases and proteases, as well as large scale 3D imaging.49,120,121 A recent study illustrates how co-registering IMS data with data from magnetic resonance imaging of prostate cancer allows 3D reconstruction of tumors and tumor margins and spatial identification of specific oncometabolites.120 Other enzymes can also readily be incorporated into the workflow. As described for incorporating Endo F3 into the current workflows, other enzymes targeting different glycoconjugates could also be used. For example, another endoglycosidase, Endoglycosidase S (Endo S), cleaves N-glycans in a similar manner to Endo F3 but is specific to N-glycans present on human immunoglobulin G91. This enzyme could find applicability in each of the tissue, biofluid and antibody microarray workflow. Additionally, the slide-based biofluid assays described for antibody capture arrays and total serum and plasma glycan analysis and immunoarrays could be adapted to other types of biofluid targets. A major new target is the adaptation of these approaches to characterizing the N-glycan constituents of immune cell subsets, either using peripheral blood mononuclear cell isolates or from flow cytometry sorted fractions. Different components of the antibody capture array, amine-reactive slide and cell culturing strategies are being applied to clinical immune cell isolates. This remains a largely unexplored area for N-glycans that could lead to major diagnostic advances for cancer immunotherapy and infectious disease monitoring.

Summary

The purpose of this review was to provide an overview of the clinically relevant applications of this rapidly evolving glycan MALDI-IMS methodology and highlights its potential value as a clinical diagnostic tool. Applying N-glycan MALDI-IMS workflows to the study of tissues, cells and biofluids has expanded the ability to link glycobiology to mechanisms of disease and improved biomarker detection capabilities. The development and integration of technological advancements in mass spectrometers and sample preparation techniques have and will continue to expand the use of MALDI-IMS for the robust analysis of clinical specimens.

KEY POINTS.

Imaging mass spectrometry (IMS) is a powerful tool to link changes in disease associated N-linked glycosylation with histopathology features in standard formalin-fixed paraffin embedded tissue samples

N-glycan IMS has revealed specific carbohydrate structures and motifs associated with a variety of cancers with the potential for development into clinical biomarkers

Advancements in instrumentation and sample preparation can effectively address N-glycan IMS limitations, such as sialic acid stability, structural isomer determination, and matrix effects

The tissue N-glycan IMS workflow has been adapted to clinical biofluids, cultured cells, and immunoarray captured glycoproteins for detection of changes in glycosylation associated with disease

SYNOPSIS.

N-glycan imaging mass spectrometry (IMS) is a recent and adaptable new tool to rapidly and reproducibly identify changes in disease associated N-linked glycosylation that are linked with histopathology features in standard formalin-fixed paraffin embedded tissue samples. The method can detect multiple N-glycans simultaneously and has been used to identify specific N-glycans and carbohydrate structural motifs as possible cancer biomarkers. Recent advancements in instrumentation and sample preparation are also discussed that address known limitations of the method and challenges for mass spectrometry analysis of glycans. The tissue N-glycan IMS workflow has been adapted to new glass slide-based assays for effective and rapid analysis of clinical biofluids, cultured cells, and immunoarray captured glycoproteins for detection of changes in glycosylation associated with disease.

Funding Acknowledgements:

This research was supported in part by the South Carolina Smart State Centers of Economic Excellence (RRD, ASM) and National Institutes of Health grants U01CA242096 (RRD,ASM,PMA); R41DK124058 (ASM), U01CA226052 (ASM,RRD), Biorepository and Tissue Analysis Shared Resource, Hollings Cancer Center, Medical University of South Carolina (P30 CA138313), and T32GM132055 to CTM.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Author Disclosures:

Richard Drake, Peggi Angel and Anand Mehta disclose partial ownership interests in two companies, GlycoPath, LLC, Mt. Pleasant, South Carolina, and N-Zyme Scientifics, Doylestown Pennsylvania.

References

- 1.Nairn AV, York WS, Harris K, Hall EM, Pierce JM, Moremen KW. Regulation of glycan structures in animal tissues: Transcript profiling of glycan-related genes. J Biol Chem. 2008;283(25):17298–17313. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M801964200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Apweiler R, Hermjakob H, Sharon N. On the frequency of protein glycosylation, as deduced from analysis of the SWISS-PROT database. Biochim Biophys Acta - Gen Subj. 1999;1473(1):4–8. doi: 10.1016/S0304-4165(99)00165-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Moremen KW, Tiemeyer M, Nairn A V. Vertebrate protein glycosylation: Diversity, synthesis and function. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2012;13(7):448–462. doi: 10.1038/nrm3383 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tanaka T, Yoneyama T, Noro D, et al. Aberrant N-glycosylation profile of serum immunoglobulins is a diagnostic biomarker of urothelial carcinomas. Int J Mol Sci. 2017;18(12):1–14. doi: 10.3390/ijms18122632 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gu J, Isaji T, Xu Q, et al. Potential roles of N-glycosylation in cell adhesion. Glycoconj J. 2012;29(8-9):599–607. doi: 10.1007/s10719-012-9386-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shental-Bechor D, Levy Y. Folding of glycoproteins: toward understanding the biophysics of the glycosylation code. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2009;19(5):524–533. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2009.07.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kailemia MJ, Park D, Lebrilla CB. Glycans and glycoproteins as specific biomarkers for cancer. Anal Bioanal Chem. 2017;409(2):395–410. doi: 10.1007/s00216-016-9880-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Adamczyk B, Tharmalingam T, Rudd PM. Glycans as cancer biomarkers. Biochim Biophys Acta - Gen Subj. 2012;1820(9):1347–1353. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2011.12.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Albrecht S, Unwin L, Muniyappa M, Rudd PM. Glycosylation as a marker for inflammatory arthritis. Cancer Biomarkers. 2014;14:17–28. doi: 10.3233/CBM-130373 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Blomme B, Van Steenkiste C, Callewaert N, Van Vlierberghe H. Alteration of protein glycosylation in liver diseases. J Hepatol. 2009;50(3):592–603. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2008.12.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Williams SE, Mealer RG, Scolnick EM, Smoller JW, Cummings RD. Aberrant glycosylation in schizophrenia: a review of 25 years of post-mortem brain studies. Mol Psychiatry. 2020. doi: 10.1038/s41380-020-0761-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lemmers RFH, Vilaj M, Urda D, et al. IgG glycan patterns are associated with type 2 diabetes in independent European populations. Biochim Biophys Acta - Gen Subj. 2017;1861(9):2240–2249. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2017.06.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liu D, Zhao Z, Wang A, et al. Ischemic stroke is associated with the pro-inflammatory potential of N-glycosylated immunoglobulin G. J Neuroinflammation. 2018;15(1):123. doi: 10.1186/s12974-018-1161-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Russell AC, Šimurina M, Garcia MT, et al. The N-glycosylation of immunoglobulin G as a novel biomarker of Parkinson’s disease. Glycobiology. 2017;27(5):501–510. doi: 10.1093/glycob/cwx022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Barton JG, Bois JP, Sarr MG, et al. Predictive and prognostic value of CA 19-9 in resected pancreatic adenocarcinoma. J Gastrointest Surg. 2009;13(11):2050–2058. doi: 10.1007/s11605-009-0849-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Drake RR. Glycosylation and cancer: Moving glycomics to the forefront. In: Advances in Cancer Research. Vol 126. Academic Press Inc.; 2015:1–10. doi: 10.1016/bs.acr.2014.12.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ludwig JA, Weinstein JN. Biomarkers in cancer staging, prognosis and treatment selection. Nat Rev Cancer. 2005;5(11):845–856. doi: 10.1038/nrc1739 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Song E, Mechref Y. Defining glycoprotein cancer biomarkers by MS in conjunction with glycoprotein enrichment. Biomark Med. 2015;9(9):835–844. doi: 10.2217/bmm.15.55 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brooks SA. Lectin histochemistry: Historical perspectives, state of the art, and the future. In: Methods in Molecular Biology. Vol 1560. Humana Press Inc.; 2017:93–107. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-6788-9_6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cummings RD. The repertoire of glycan determinants in the human glycome. Mol Biosyst. 2009;5(10):1087–1104. doi: 10.1039/b907931a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sterner E, Flanagan N, Gildersleeve JC. Perspectives on Anti-Glycan Antibodies Gleaned from Development of a Community Resource Database. ACS Chem Biol. 2016;11(7):1773–1783. doi: 10.1021/acschembio.6b00244 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Smith DF, Cummings RD. Application of microarrays for deciphering the structure and function of the human glycome. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2013;12(4):902–912. doi: 10.1074/mcp.R112.027110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ruhaak LR, Xu G, Li Q, Goonatilleke E, Lebrilla CB. Mass Spectrometry Approaches to Glycomic and Glycoproteomic Analyses. Chem Rev. 2018;118(17):7886–7930. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.7b00732 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Reiding KR, Bondt A, Hennig R, et al. High-throughput Serum N-Glycomics: Method Comparison and Application to Study Rheumatoid Arthritis and Pregnancy-associated Changes. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gray C, Flitsch SL. Methods for the high resolution analysis of glycoconjugates. In: Coupling and Decoupling of Diverse Molecular Units in Glycosciences. Springer International Publishing; 2017:225–267. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-65587-1_11 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Reider B, Jarvas G, Krenkova J, Guttman A. Separation based characterization methods for the N-glycosylation analysis of prostate-specific antigen. J Pharm Biomed Anal. 2021;194:113797. doi: 10.1016/j.jpba.2020.113797 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhang L, Luo S, Zhang B. Glycan analysis of therapeutic glycoproteins Glycan analysis of therapeutic glycoproteins. MAbs. 2016;8(2):205–215. doi: 10.1080/19420862.2015.1117719 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Powers TW, Jones EE, Betesh LR, et al. Matrix assisted laser desorption ionization imaging mass spectrometry workflow for spatial profiling analysis of N-linked Glycan expression in tissues. Anal Chem. 2013;85(20):9799–9806. doi: 10.1021/ac402108x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Powers TW, Neely BA, Shao Y, et al. MALDI imaging mass spectrometry profiling of N-glycans in formalin-fixed paraffin embedded clinical tissue blocks and tissue microarrays. PLoS One. 2014;9(9):1–11. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0106255 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Drake RR, Powers TW, Jones EE, Bruner E, Mehta AS, Angel PM. MALDI Mass Spectrometry Imaging of N-Linked Glycans in Cancer Tissues. In: Advances in Cancer Research. Vol 134. Academic Press Inc.; 2017:85–116. doi: 10.1016/bs.acr.2016.11.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Blaschke C, Black A, Mehta AS, Angel PM, Drake RR. Rapid N-Glycan Profiling of Serum and Plasma by a Novel Slide Based Imaging Mass Spectrometry Workflow. J Am Soc Mass Spectrom. 2020. doi: 10.1021/jasms.0c00213 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Angel PM, Saunders J, Clift CL, et al. A Rapid Array-Based Approach to N-Glycan Profiling of Cultured Cells. J Proteome Res. 2019;18(10):3630–3639. doi: 10.1021/acs.jproteome.9b00303 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Black AP, Liang H, West CA, et al. A novel mass spectrometry platform for multiplexed N-glycoprotein biomarker discovery from patient biofluids by antibody panel based N-glycan imaging. Anal Chem. 2019;91(13):8429–8435. doi: 10.1021/acs.analchem.9b01445 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Drake RR, Powers TW, Norris-Caneda K, Mehta AS, Angel PM. In Situ Imaging of N-Glycans by MALDI Imaging Mass Spectrometry of Fresh or Formalin-Fixed Paraffin-Embedded Tissue. Curr Protoc Protein Sci. 2018;94(1):1–21. doi: 10.1002/cpps.68 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Black AP, Angel PM, Drake RR, Mehta AS. Antibody Panel Based N -Glycan Imaging for N -Glycoprotein Biomarker Discovery. Curr Protoc Protein Sci. 2019;98(1). doi: 10.1002/cpps.99 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Drake RR, Boggs SR, Drake SK. Pathogen identification using mass spectrometry in the clinical microbiology laboratory. J Mass Spectrom. 2011;46(12):1223–1232. doi: 10.1002/jms.2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kostrzewa M Application of the MALDI Biotyper to clinical microbiology: progress and potential. Expert Rev Proteomics. 2018;15(3):193–202. doi: 10.1080/14789450.2018.1438193 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Caprioli RM, Farmer TB, Gile J. Molecular Imaging of Biological Samples: Localization of Peptides and Proteins Using MALDI-TOF MS. Anal Chem. 1997;69(23):4751–4760. doi: 10.1021/ac970888i [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schwamborn K, Caprioli RM. Molecular imaging by mass spectrometry-looking beyond classical histology. Nat Rev Cancer. 2010;10(9):639–646. doi: 10.1038/nrc2917 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Angel PM, Caprioli RM. Matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization imaging mass spectrometry: In situ molecular mapping. Biochemistry. 2013;52(22):3818–3828. doi: 10.1021/bi301519p [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Porta Siegel T, Hamm G, Bunch J, Cappell J, Fletcher JS, Schwamborn K. Mass Spectrometry Imaging and Integration with Other Imaging Modalities for Greater Molecular Understanding of Biological Tissues. Mol Imaging Biol. 2018;20(6):888–901. doi: 10.1007/s11307-018-1267-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Deutskens F, Yang J, Caprioli RM. High spatial resolution imaging mass spectrometry and classical histology on a single tissue section. J Mass Spectrom. 2011;46(6):568–571. doi: 10.1002/jms.1926 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Drake RR, McDowell C, West C, et al. Defining the human kidney N-glycome in normal and cancer tissues using MALDI imaging mass spectrometry. J Mass Spectrom. 2020;55(4):e4490. doi: 10.1002/jms.4490 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gemperline E, Rawson S, Li L. Optimization and comparison of multiple MALDI matrix application methods for small molecule mass spectrometric imaging. Anal Chem. 2014;86(20):10030–10035. doi: 10.1021/ac5028534 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Scott DA, Norris-Caneda K, Spruill L, et al. Specific N-linked glycosylation patterns in areas of necrosis in tumor tissues. Int J Mass Spectrom. 2019;437:69–76. doi: 10.1016/j.ijms.2018.01.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Scott DA, Casadonte R, Cardinali B, et al. Increases in Tumor N-Glycan Polylactosamines Associated with Advanced HER2-Positive and Triple-Negative Breast Cancer Tissues. PROTEOMICS – Clin Appl. 2019;13(1):1800014. doi: 10.1002/prca.201800014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Herrera H, Dilday T, Uber A, et al. Core-Fucosylated Tetra-Antennary N-Glycan Containing A Single N-Acetyllactosamine Branch Is Associated with Poor Survival Outcome in Breast Cancer. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20(10):2528. doi: 10.3390/ijms20102528 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.West CA, Liang H, Drake RR, Mehta AS. A New Enzymatic Approach to Distinguish Fucosylation Isomers of N-linked Glycans in Tissues Using MALDI Imaging Mass Spectrometry. J Proteome Res. 2020. doi: 10.1021/acs.jproteome.0c00024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Drake RR, Angel PM, Wu J, Pachynski RK, Ippolito JE. How else can we approach prostate cancer biomarker discovery? Expert Rev Mol Diagn. 2020;20(2):123–125. doi: 10.1080/14737159.2019.1665507 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.West CA, Wang M, Herrera H, et al. N-Linked Glycan Branching and Fucosylation Are Increased Directly in Hcc Tissue As Determined through in Situ Glycan Imaging. J Proteome Res. 2018;17(10):3454–3462. doi: 10.1021/acs.jproteome.8b00323 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.McDowell CT, Klamer Z, Hall J, et al. Imaging Mass Spectrometry and Lectin Analysis of N-linked Glycans in Carbohydrate Antigen Defined Pancreatic Cancer Tissues. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2021;20. doi: 10.1074/mcp.ra120.002256 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Briggs MT, Condina MR, Ho YY, et al. MALDI Mass Spectrometry Imaging of Early- and Late-Stage Serous Ovarian Cancer Tissue Reveals Stage-Specific N-Glycans. Proteomics. 2019;19(21-22):1800482. doi: 10.1002/pmic.201800482 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Holst S, Heijs B, De Haan N, et al. Linkage-Specific in Situ Sialic Acid Derivatization for N-Glycan Mass Spectrometry Imaging of Formalin-Fixed Paraffin-Embedded Tissues. Anal Chem. 2016;88(11):5904–5913. doi: 10.1021/acs.analchem.6b00819 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Heijs B, Holst S, Briaire-De Bruijn IH, et al. Multimodal Mass Spectrometry Imaging of N-Glycans and Proteins from the Same Tissue Section. Anal Chem. 2016;88(15):7745–7753. doi: 10.1021/acs.analchem.6b01739 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Heijs B, Holst-Bernal S, de Graaff MA, et al. Molecular signatures of tumor progression in myxoid liposarcoma identified by N-glycan mass spectrometry imaging. Lab Investig. 2020;100(9):1252–1261. doi: 10.1038/s41374-020-0435-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Carter CL, Parker GA, Hankey KG, Farese AM, MacVittie TJ, Kane MA. MALDI-MSI spatially maps N-glycan alterations to histologically distinct pulmonary pathologies following irradiation. Sci Rep. 2020;10(1):1–14. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-68508-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Angel PM, Baldwin HS, Gottlieb Sen D, et al. Advances in MALDI imaging mass spectrometry of proteins in cardiac tissue, including the heart valve. Biochim Biophys Acta - Proteins Proteomics. 2017;1865(7):927–935. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2017.03.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Angel PM, Drake RR, Park Y, et al. Spatial N-glycomics of the human aortic valve in development and pediatric endstage congenital aortic valve stenosis. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2021;154:6–20. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2021.01.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Powers T, Holst S, Wuhrer M, et al. Two-Dimensional N-Glycan Distribution Mapping of Hepatocellular Carcinoma Tissues by MALDI-Imaging Mass Spectrometry. Biomolecules. 2015;5(4):2554–2572. doi: 10.3390/biom5042554 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Briggs MT, Kuliwaba JS, Muratovic D, et al. MALDI mass spectrometry imaging of N -glycans on tibial cartilage and subchondral bone proteins in knee osteoarthritis. Proteomics. 2016;16(11-12):1736–1741. doi: 10.1002/pmic.201500461 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ostasiewicz P, Zielinska DF, Mann M, Wisniewski JR. Proteome, phosphoproteome, and N-glycoproteome are quantitatively preserved in formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tissue and analyzable by high-resolution mass spectrometry. J Proteome Res. 2010;9(7):3688–3700. doi: 10.1021/pr100234w [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Porterfield M, Zhao P, Han H, et al. Discrimination between adenocarcinoma and normal pancreatic ductal fluid by proteomic and glycomic analysis. J Proteome Res. 2014;13(2):395–407. doi: 10.1021/pr400422g [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Schneider M, Al-Shareffi E, Haltiwanger RS. Biological functions of fucose in mammals. Glycobiology. 2017;7(27):601–618. doi: 10.1093/glycob/cwx034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Harduin-Lepers A, Vallejo-Ruiz V, Krzewinski-Recchi MA, Samyn-Petit B, Julien S, Delannoy P. The human sialyltransferase family. Biochimie. 2001;83(8):727–737. doi: 10.1016/S0300-9084(01)01301-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Keeley TS, Yang S, Lau E. The diverse contributions of fucose linkages in cancer. Cancers (Basel). 2019;11(9). doi: 10.3390/cancers11091241 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Comunale MA, Rodemich-Betesh L, Hafner J, et al. Linkage Specific Fucosylation of Alpha-1-Antitrypsin in Liver Cirrhosis and Cancer Patients: Implications for a Biomarker of Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Ryu W-S, ed. PLoS One. 2010;5(8):e12419. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0012419 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Comunale MA, Wang M, Hafner J, et al. Identification and development of fucosylated glycoproteins as biomarkers of primary hepatocellular carcinoma. J Proteome Res. 2009;8(2):595–602. doi: 10.1021/pr800752c [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Nie H, Li Y, Sun XL. Recent advances in sialic acid-focused glycomics. J Proteomics. 2012;75(11):3098–3112. doi: 10.1016/j.jprot.2012.03.050 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Reiding KR, Blank D, Kuijper DM, Deelder AA, Wuhrer M. High-Throughput Profiling of Protein N-Glycosylation by MALDI-TOF-MS Employing Linkage-Specific Sialic Acid Esterification. 2014. doi: 10.1021/ac500335t [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Ucal Y, Ozpinar A. Improved spectra for MALDI MSI of peptides using ammonium phosphate monobasic in MALDI matrix. J Mass Spectrom. 2018;53(8):635–648. doi: 10.1002/jms.4198 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Angel PM, Spraggins JM, Baldwin HS, Caprioli R. Enhanced sensitivity for high spatial resolution lipid analysis by negative ion mode matrix assisted laser desorption ionization imaging mass spectrometry. Anal Chem. 2012;84(3):1557–1564. doi: 10.1021/ac202383m [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Zhu X, Papayannopoulos IA. Improvement in the Detection of Low Concentration Protein Digests on a MALDI TOF/TOF Workstation by Reducing-Cyano-4-Hydroxycinnamic Acid Adduct Ions. Vol 14. The Association of Biomolecular Resource Facilities; 2003. /pmc/articles/PMC2279961/?report=abstract. Accessed August 18, 2020. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Smirnov IP, Zhu X, Taylor T, et al. Suppression of α-cyano-4-hydroxycinnamic acid matrix clusters and reduction of chemical noise in MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry. Anal Chem. 2004;76(10):2958–2965. doi: 10.1021/ac035331j [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Asara JM, Allison J. Enhanced detection of phosphopeptides in matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization mass spectrometry using ammonium salts. J Am Soc Mass Spectrom. 1999;10(1):35–44. doi: 10.1016/S1044-0305(98)00129-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Zhao X, Guo C, Huang Y, et al. Combination Strategy of Reactive and Catalytic Matrices for Qualitative and Quantitative Profiling of N-Glycans in MALDI-MS. Anal Chem. 2019. doi: 10.1021/acs.analchem.9b02144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Bern M, Brito AE, Pang PC, Rekhi A, Dell A, Haslam SM. Polylactosaminoglycan glycomics: Enhancing the detection of high-molecular-weight N-glycans in matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization time-of-flight profiles by matched filtering. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2013;12(4):996–1004. doi: 10.1074/mcp.O112.026377 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Barré FPY, Paine MRL, Flinders B, et al. Enhanced sensitivity using maldi imaging coupled with laser postionization (maldi-2) for pharmaceutical research. Anal Chem. 2019;91(16):10840–10848. doi: 10.1021/acs.analchem.9b02495 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Fernandez-Lima F Trapped Ion Mobility Spectrometry: past, present and future trends. Int J Ion Mobil Spectrom. 2016;19(2-3):65–67. doi: 10.1007/s12127-016-0206-3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Spraggins JM, Djambazova KV., Rivera ES, et al. High-Performance Molecular Imaging with MALDI Trapped Ion-Mobility Time-of-Flight (timsTOF) Mass Spectrometry. Anal Chem. 2019;91(22):14552–14560. doi: 10.1021/acs.analchem.9b03612 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Pu Y, Ridgeway ME, Glaskin RS, Park MA, Costello CE, Lin C. Separation and Identification of Isomeric Glycans by Selected Accumulation-Trapped Ion Mobility Spectrometry-Electron Activated Dissociation Tandem Mass Spectrometry. Anal Chem. 2016;88(7):3440–3443. doi: 10.1021/acs.analchem.6b00041 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Sigal YM, Zhou R, Zhuang X. Visualizing and discovering cellular structures with super-resolution microscopy. Science (80- ). 2018;361(6405):880–887. doi: 10.1126/science.aau1044 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Keren L, Bosse M, Thompson S, et al. MIBI-TOF: A multiplexed imaging platform relates cellular phenotypes and tissue structure. Sci Adv. 2019;5(10):eaax5851. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.aax5851 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Ščupáková K, Balluff B, Tressler C, et al. Cellular resolution in clinical MALDI mass spectrometry imaging: The latest advancements and current challenges. Clin Chem Lab Med. 2020;58(6):914–929. doi: 10.1515/cclm-2019-0858 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Keren L, Bosse M, Marquez D, et al. A Structured Tumor-Immune Microenvironment in Triple Negative Breast Cancer Revealed by Multiplexed Ion Beam Imaging. Cell. 2018;174(6):1373–1387.e19. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2018.08.039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Zavalin A, Todd EM, Rawhouser PD, Yang J, Norris JL, Caprioli RM. Direct imaging of single cells and tissue at sub-cellular spatial resolution using transmission geometry MALDI MS. J Mass Spectrom. 2012;47(11):i–i. doi: 10.1002/jms.3132 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Niehaus M, Soltwisch J, Belov ME, Dreisewerd K. Transmission-mode MALDI-2 mass spectrometry imaging of cells and tissues at subcellular resolution. Nat Methods. 2019;16(9):925–931. doi: 10.1038/s41592-019-0536-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Block TM, Comunale MA, Lowman M, et al. Use of targeted glycoproteomics to identify serum glycoproteins that correlate with liver cancer in woodchucks and humans. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102(3):779–784. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0408928102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Wang M, Sanda M, Comunale MA, et al. Changes in the glycosylation of kininogen and the development of a kininogen-based algorithm for the early detection of HCC. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2017;26(5):795–803. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-16-0974 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Wang M, Long RE, Comunale MA, et al. Novel fucosylated biomarkers for the early detection of hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2009;18(6):1914–1921. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-08-0980 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Comunale MA, Lowman M, Long RE, et al. Proteomic analysis of serum associated fucosylated glycoproteins in the development of primary hepatocellular carcinoma. J Proteome Res. 2006;5(2):308–315. doi: 10.1021/pr050328x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Hoshida Y, Nijman SMB, Kobayashi M, et al. Integrative Transcriptome Analysis Reveals Common Molecular Subclasses of Human Hepatocellular Carcinoma. 2009. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-1089 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Tan PS, Nakagawa S, Goossens N, et al. Clinicopathological indices to predict hepatocellular carcinoma molecular classification. Liver Int. 2016;36(1):108–118. doi: 10.1111/liv.12889 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Reiding KR, Ruhaak LR, Uh H-W, et al. Human Plasma N-glycosylation as Analyzed by Matrix-Assisted Laser Desorption/Ionization-Fourier Transform Ion Cyclotron Resonance-MS Associates with Markers of Inflammation and Metabolic Health*. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2017;16(2):228–242. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M116.065250 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Bladergroen MR, Reiding KR, Hipgrave Ederveen AL, et al. Automation of high-throughput mass spectrometry-based plasma n-glycome analysis with linkage-specific sialic acid esterification. J Proteome Res. 2015;14(9):4080–4086. doi: 10.1021/acs.jproteome.5b00538 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.M Vreeker GC, Nicolardi S, Bladergroen MR, et al. Automated Plasma Glycomics with Linkage-Specific Sialic Acid Esterification and Ultrahigh Resolution MS. 2018. doi: 10.1021/acs.analchem.8b02391 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Vreeker GCM, Bladergroen MR, Nicolardi S, et al. Dried blood spot N-glycome analysis by MALDI mass spectrometry. Talanta. 2019;205:120104. doi: 10.1016/J.TALANTA.2019.06.104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Zhang Z, Westhrin M, Bondt A, Wuhrer M, Standal T, Holst S. Serum protein N-glycosylation changes in multiple myeloma. Biochim Biophys Acta - Gen Subj. 2019;1863(5):960–970. doi: 10.1016/J.BBAGEN.2019.03.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Clerc F, Novokmet M, Dotz V, et al. Plasma N-Glycan Signatures Are Associated With Features of Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. Gastroenterology. 2018;155(3):829–843. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2018.05.030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.de Vroome SW, Holst S, Girondo MR, et al. Serum N-glycome alterations in colorectal cancer associate with survival. Oncotarget. 2018;9(55):30610–30623. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.25753 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Miura Y, Hato M, Shinohara Y, et al. BlotGlycoABC™, an integrated glycoblotting technique for rapid and large scale clinical glycomics. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2008;7(2):370–377. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M700377-MCP200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Nishimura SI. Toward automated glycan analysis. Adv Carbohydr Chem Biochem. 2011;65:219–271. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-385520-6.00005-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Miyahara K, Nouso K, Saito S, et al. Serum Glycan Markers for Evaluation of Disease Activity and Prediction of Clinical Course in Patients with Ulcerative Colitis. Takehara T, ed. PLoS One. 2013;8(10):e74861. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0074861 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Gebrehiwot AG, Melka DS, Kassaye YM, et al. Exploring serum and immunoglobulin G N-glycome as diagnostic biomarkers for early detection of breast cancer in Ethiopian women. BMC Cancer. 2019;19(1):588. doi: 10.1186/s12885-019-5817-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Hatakeyama S, Amano M, Tobisawa Y, et al. Serum N-Glycan Alteration Associated with Renal Cell Carcinoma Detected by High Throughput Glycan Analysis. J Urol. 2014;191(3):805–813. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2013.10.052 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Gizaw ST, Ohashi T, Tanaka M, Hinou H, Nishimura SI. Glycoblotting method allows for rapid and efficient glycome profiling of human Alzheimer’s disease brain, serum and cerebrospinal fluid towards potential biomarker discovery. Biochim Biophys Acta - Gen Subj. 2016;1860(8):1716–1727. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2016.03.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Matsumoto T, Hatakeyama S, Yoneyama T, et al. Serum N-glycan profiling is a potential biomarker for castration-resistant prostate cancer. Sci Rep. 2019;9(1):16761. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-53384-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Noro D, Yoneyama T, Hatakeyama S, et al. Serum aberrant N-glycan profile as a marker associated with early antibody-mediated rejection in patients receiving a living donor kidney transplant. Int J Mol Sci. 2017;18(8). doi: 10.3390/ijms18081731 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Johnson PJ, Poon TCW, Hjelm NM, Ho CS, Blake C, Ho SKW. Structures of disease-specific serum alpha-fetoprotein isoforms. Br J Cancer. 2000;83(10):1330–1337. doi: 10.1054/bjoc.2000.1441 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Mehta A, Herrera H, Block T. Glycosylation and liver cancer. In: Advances in Cancer Research. Vol 126. Academic Press Inc.; 2015:257–279. doi: 10.1016/bs.acr.2014.11.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Shajahan A, Heiss C, Ishihara M, Azadi P. Glycomic and glycoproteomic analysis of glycoproteins—a tutorial. Anal Bioanal Chem. 2017;409(19):4483–4505. doi: 10.1007/s00216-017-0406-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Domann PJ, Pardos-Pardos AC, Fernandes DL, et al. Separation-based Glycoprofiling Approaches using Fluorescent Labels. Proteomics. 2007;7(S1):70–76. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200700640 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Vilaj M, Gudelj I, Trbojević-Akmačić I, Lauc G, Pezer M. IgG Glycans as a Biomarker of Biological Age. In: ; 2019:81–99. doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-24970-0_7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Imre T, Kremmer T, Héberger K, et al. Mass spectrometric and linear discriminant analysis of N-glycans of human serum alpha-1-acid glycoprotein in cancer patients and healthy individuals. J Proteomics. 2008;71(2):186–197. doi: 10.1016/j.jprot.2008.04.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Tsai H-Y, Boonyapranai K, Sriyam S, et al. Glycoproteomics analysis to identify a glycoform on haptoglobin associated with lung cancer. Proteomics. 2011;11(11):2162–2170. doi: 10.1002/pmic.201000319 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Bones J, Mittermayr S, O’Donoghue N, Guttman A, Rudd PM. Ultra performance liquid chromatographic profiling of serum N-glycans for fast and efficient identification of cancer associated alterations in glycosylation. Anal Chem. 2010;82(24):10208–10215. doi: 10.1021/ac102860w [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Hirabayashi J, Concept strategy and realization of lectin-based glycan profiling. J Biochem. 2008;144(2):139–147. doi: 10.1093/jb/mvn043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Chen S, LaRoche T, Hamelinck D, et al. Multiplexed analysis of glycan variation on native proteins captured by antibody microarrays. Nat Methods. 2007;4(5):437–444. doi: 10.1038/nmeth1035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Darebna P, Spicka J, Kucera R, et al. Detection and Quantification of Carbohydrate-Deficient Transferrin by MALDI-Compatible Protein Chips Prepared by Ambient Ion Soft Landing. Clin Chem. 2018;64(9):1319–1326. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2017.285452 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Basu SS, Regan MS, Randall EC, et al. Rapid MALDI mass spectrometry imaging for surgical pathology. npj Precis Oncol. 2019;3(1). doi: 10.1038/s41698-019-0089-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Abdelmoula WM, Regan MS, Lopez BGC, et al. Automatic 3D Nonlinear Registration of Mass Spectrometry Imaging and Magnetic Resonance Imaging Data. Anal Chem. 2019;91(9):6206–6216. doi: 10.1021/acs.analchem.9b00854 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Clift CL, Mehta AS, Drake RR, Angel PM. Multiplexed imaging mass spectrometry of the extracellular matrix using serial enzyme digests from formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tissue sections. Anal Bioanal Chem. November 2020:1–11. doi: 10.1007/s00216-020-03047-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]