Abstract

Background

Jianpi Yiqi Taohua decoction (JYTD) has shown therapeutic effects in ulcerative colitis (UC). However, the pharmacological mechanism of JYTD against UC remains unclear.

Material/Methods

Compounds and targets of JYTD and UC-related genes were screened from public databases. Integrated analysis was performed to identify therapeutic targets of UC, followed by functional enrichment analysis. Protein–protein interaction (PPI) and pharmacological networks were then established. Molecular docking was used to validate the affinity of compounds and their targets. Further, the efficacy of JYTD was evaluated by meta-analysis. Relevant studies were searched from 5 databases. Outcomes were complete response rate (CRR) and overall response rate (ORR), and pooled results were estimated by risk ratio (RR) with corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CIs).

Results

The pharmacological network identified 13 herbal medicines, 28 compounds, 54 targets, and 20 pathways. Stigmasterol, liquiritigenin, and naringenin were potential active compounds, and PRKCA, NFKB1, ESR1, NTRK1, AKT1, PPARG, RXRA, and VDR were hub targets. Pathway analysis revealed that genes were mainly involved in the cellular response to lipids. Molecular docking indicated that AKT1, NFKB1, ESR1, NTRK1, PRKCA, and PPARG exhibited good affinity to 6 key compounds of JYTD. Then, meta-analysis revealed that Tao Hua decoction treatment significantly improved CRR (RR, 1.21; 95% CI, 1.06–1.37; P=0.004) and ORR (RR, 1.16; 95% CI, 1.08–1.24; P<0.001).

Conclusions

JYTD was found to have preventive and therapeutic effects on UC through multiple compounds, targets, and pathways. These findings enhanced our understanding of the potential pharmacological mechanisms of JYTD against UC.

Keywords: Molecular Docking Simulation, Pediatric Ulcerative Colitis, Pharmacology

Background

Ulcerative colitis (UC) is a chronic idiopathic bowel disease characterized by intestinal (colon and rectum) inflammation [1], with clinical symptoms that include bloody diarrhea, acute pain, hemafecia, and weight loss [2]. UC is a common gastrointestinal disease in China. To date, UC has been predominantly treated with 5-aminosalicylate, cyclosporine, and ustekinumab. However, these drugs may produce a series of adverse events that can increase the risk of infection and neoplasia [3,4]. Moreover, the main objective of these drug therapies for patients with UC is to induce and maintain the relief of symptoms and mucosal inflammation [5]. Therefore, it is necessary to explore safe and effective treatments.

Jianpi Yiqi Taohua decoction (JYTD) is a common traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) that derives from the basis of the classic prescription “Tao Hua decoction” and has been used to treat UC with various causes [6]. According to TCM theory, UC can be divided into different TCM syndromes, mainly including Pi-Xu-Shi-Yun syndrome (syndrome of spleen deficiency and dampness) and Da-Chang-Shi-Re syndrome (syndrome of dampness-heat in the large intestine) [7]. JYTD has been most effective in patients with UC who have Pi-Xu-Shi-Yun syndrome. The usage of this prescription is as follows: “when UC is characterized by Shaoyin disease with purulent bloody stool syndrome, the Tao Hua decoction is prescribed”. This formula is composed of Codonopsis pilosula (Dangshen, DS), Atractylodis Macrocephalae Rhizoma (Baizhu, BZ), Astragalus membranaceus (Huangqi, HQ), Zingiberis Rhizoma (Ganjiang, GJ), Halloysitum Rubrum (Chishizhi, CSZ), Coptis chinensis Franch. (Huanglian, HL), Dolichos lablab L. (Baibiandou, BBD), Terminalia chebula Retz. (Hezi, HZ), Dioscorea opposita Thunb. (Shanyao, SY), Rhizoma Curculigins (Xianmao, XM), Amomi fructus (Sharen, SR), Corydalis yanhusuo (Yuanhu, YH), Semen Coicis (Yiyiren, YYR), Aucklandia lappa Dence. (Muxiang, MX), Citrus reticulata Blanco (Chenpi, CP), Oryza sativa L. (Jingmi, JM), Paeonia lactiflora Pall. (Baishao, BS), and Glycyrrhiza uralensis Fisch. (Zhigancao, ZGC). TCM studies have indicated that UC is related to the spleen and kidneys [8], and spleen deficiency is the main cause of UC [9]. Evidence indicates that the TCM in JYTD can alleviate UC injury by relieving diarrhea, dispelling cold, nourishing the stomach, and strengthening the spleen [10]. However, the potential molecular mechanisms of JYTD have not been fully elucidated.

TCM is used to treat diseases through multiple compounds and targets, rather than through a single compound or target. Similarly, network pharmacology studies emphasize network targets and multi-compound therapeutics, which is consistent with the principle of TCM [11]. In addition, other bioinformatics resources, including molecular docking, have been developed to provide good opportunities for comprehensive drug mechanism studies. Molecular docking is an important tool for computer-aided drug design [12] and can evaluate the binding potential of protein ligands based on network pharmacological prediction and analysis [13]. In this study, network pharmacology and molecular docking methods were employed to investigate potential core compounds and their targets for JYTD in the treatment of UC. Further, meta-analysis was performed to evaluate the effective of JYTD. The flow chart of this analysis is shown in Supplementary Figure 1. The goal of this study is to provide evidence-based scientific support for the use of JYTD against UC in clinical practice.

Material and Methods

Identification of Compounds in JYTD

All chemical compounds of each herb in the JYTD were extracted from the Traditional Chinese Medicine Systems Pharmacology Database (TCMSP) (http://lsp.nwu.edu.cn/browse.php?qc=herbs) [14] and the Traditional Chinese Medicine Integrated Database (TCMID) (http://119.3.41.228:8000/tcmid/search/) [15]. In brief, we searched these online databases using the names of the herbal medicines to obtain the corresponding compound information.

Screening of Active Compounds

The absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion (ADME) parameters obtained from the TCMSP database were used to identify potential active compounds [16]. Oral bioavailability and drug-likeness are the most significant pharmacokinetic parameters in ADME. Oral bioavailability is defined as “the extent to which the active compounds are used by the human body, including the dose and rate of entry into the blood” [17]. The degree of oral bioavailability largely determines the effect of the compound on disease, and high oral bioavailability is a key indicator to confirm the similarity of bioactive molecules as therapeutic drugs [18]. Drug-likeness is a qualitative concept for drug design, and the accurate early evaluation of drug-likeness properties of a compound can assist in determining whether the compound is chemically suitable for use as a drug [19]. Thus, molecular drug-likeness evaluation is related to parameters that affect its pharmacodynamics, which ultimately influence its ADME properties [20]. In this study, the active compounds in JYTD were selected according to the criteria of oral bioavailability ≥40% and drug-likeness ≥0.2.

Prediction of Targets of Compound

The BATMAN database [21] (http://bionet.ncpsb.org/batman-tcm/) was used to predict target proteins corresponding to compounds. BATMAN can predict the potential targets of TCM compounds based on the similarity approach. First, the targets existing in the Therapeutic Target Database, Drugbank, and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) databases were obtained; then, the predicted targets were ranked in decreasing order based on the interactions between potential targets and similarities of known targets. In the present study, target proteins with scores >20 were selected for further analysis [22].

Cross-Validation of Target Proteins

The Comparative Toxicogenomics Database (CTD) [23] (http://ctdbase.org/) was published by the Mount Desert Island Biological Laboratory. The purpose of the CTD is to promote a comprehensive understanding of how environmental risks affect human health, and the CTD provides information on chemical-gene/protein interactions and chemical-disease and gene-disease relationships to help formulate disease mechanisms for environmental impacts. In the CTD, “ulcerative colitis” was used as a keyword to search for genes related to UC, and then genes were sorted by inference score [24,25]. Target proteins with scores >20 and target proteins predicted in the previous step were intersected to narrow the target protein range. The inference score was calculated from the log-transformed product of 2 public neighborhood statistics and then used to assess the functional correlation between proteins in the PPI network.

Functional Enrichment Analysis

To explore the biological function of these targets, the Gene Ontology biological processes (GO-BP), KEGG pathways, and Reactome Gene Sets enrichment analyses were performed by using the online tool “Metascape” [26] (http://metascape.org) with the default parameters. The terms that conformed to the above parameters were then obtained. According to the kappa coefficient, further clustering was conducted based on the similarity of the genes enriched in each term. The top 20 clusters were presented as bar graphs. To further understand the relationship between the terms, the interactions were screened. In brief, terms with the best P value from each cluster were selected, and terms with similarity >0.3 were connected by edges. The network was visualized using Cytoscape software [27] (version 3.4.0, http://chianti.ucsd.edu/cytoscape-3.4.0/).

PPI Network and Module Analysis

PPI pairs were explored using Metascape, and PPI enrichment analysis was conducted using the following databases: BioGrid [28], InWeb_IM [29], and OmniPath [30]. Cytoscape software was used to construct the PPI network. Next, modules were excavated from the PPI network via the molecular complex detection (MCODE) [31] algorithm in Metascape. In addition, the GO-BP, KEGG pathway, and Reactome enrichment analyses of genes in each module were performed.

Construction of Pharmacological Network

Based on the herbs-compound-targets-pathways interactions, the pharmacological network was visualized using Cytoscape software.

Molecular Docking Technology

The hub nodes with the highest connectivity in the PPI network were selected for molecular docking analysis. The 3D structure of these targets were downloaded from the Protein Data Bank (PDB) database (http://www.rcsb.org/) [32], and the conformations were screened according to the following conditions: (1) the protein structure was obtained using the X-ray diffraction method, (2) the resolution of protein structure was <3, (3) type was set to protein, and (4) protein ranked first in descending order of score for further study. Then, PyMol software (version 2.0 Schrödinger, LLC) was applied to remove other ligands and water molecules, and the isolated proteins were used for subsequent molecular docking. In this analysis, the compounds that targeted these key proteins and had higher degrees in the pharmacological network were regarded as the key compounds. The molecular structures of key compounds were downloaded from the PubChem Compound database (https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/) [33] and converted to PDB format files using PyMol for further analysis. Finally, the Lamarckian GA algorithm in AutoDock (version 4.2.6) software [34] was used to dock the active compounds with the receptor protein.

Validation of the Clinical Effect Therapeutic Effects of JYTD on UC by Using Meta-Analysis

Literature Search

The meta-analysis was performed in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Item for Systematic Review and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) [35]. JYTD is derived from the classic prescription “Tao Hua decoction”, and it is widely used in UC caused by various etiologies. Thus, we used the compounds of Tao Hua decoction to verify the efficacy of the drug. Randomized controlled trials (RCTs) were searched from PubMed, Wanfang data, the China National Knowledge Infrastructure, the China Science and Technology Journal database, and the China Biology Medicine disc through September 3, 2021, with the keywords “Taohua Tang, Taohua decoction, ulcerative colitis, and UC”. The reference lists of relevant reviews and eligible RCTs were also searched to obtain additional studies that could be used for meta-analysis.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) patients with UC diagnosed by pathology, imaging, or histology; (2) experimental group for Tao Hua decoction alone or Tao Hua decoction combined with other Chinese medicines or a control group of Western medicine treatment; (3) studies were designed as RCTs; and (4) outcome indicators were complete response rate (CRR) or overall response rate (ORR). The exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) nonrandomized trials; and (2) incomplete data on the clinical curative effect. For the same data used in multiple publications, only the study with the most complete information was included.

Data Extraction and Quality Assessment

Two reviewers independently extracted the following information from each included study: the first author, year of publication, country of study, basic characteristics of research (sample size, sex, and age), treatment protocols, and clinical outcomes. The Cochrane Collaboration’s tool [36] was used to assess the quality of included studies.

Statistical Analysis

The odds ratio (OR) with 95% confidence interval (CI) was applied to evaluate the difference in CRR and ORR between the experimental group and control group. The Cochran’s Q test and I2 test were used to measure heterogeneity among studies [37]. A value of P<0.05 and/or I2 >50% were considered as significant heterogeneity, and the random effects model was selected for meta-analysis; otherwise, the fixed effects model was used to pool results (P≥0.05 and I2 ≤50%). The Egger test was employed to assess publication bias. All statistical analyses were conducted by using RevMan 5.3 (Cochrane Collaboration, Oxford, UK) and Stata12.0 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA) software.

Results

Screening of Compounds

The chemical compounds of YJTD were initially obtained from the TCMSP and TCMID databases, and 1158 compounds were identified. After filtering with 2 ADME parameters (oral bioavailability ≥40% and drug-likeness ≥0.2), 106 active compounds were obtained from 16 different herbs, including 12 from DS, 4 from BZ, 15 from HQ, 2 from GJ, 1 from CSZ, 8 from HL, 6 from HZ, 9 from SY, 2 from XM, 4 from SR, 7 from YH, 2 from YYR, 3 from MX, 4 from CP, 10 from BS, and 17 from ZGC.

Prediction of Target Genes of YJTD

The active compounds screened in the TCMSP and TCMID databases were retrieved from the BATMAN database, and 13 core herbs and 36 active compounds with 422 potential targets were collected.

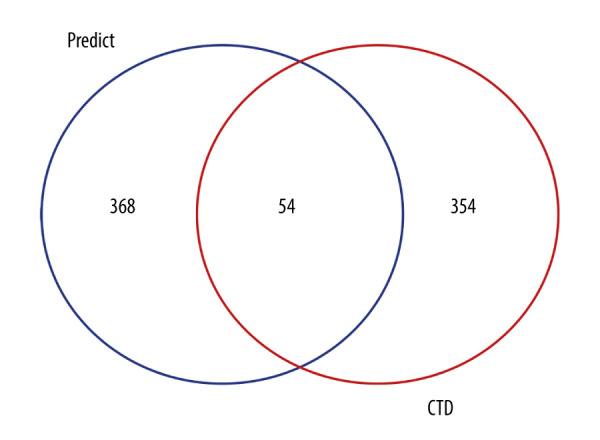

Identification of JYTD Targets for UC Treatment

UC-related genes were searched from the CTD database using the keyword “ulcerative colitis”, and 408 targets were obtained. Then, these targets were integrated with JYTD-related targets, and 54 overlapping targets were identified as effective targets for JYTD intervention in UC (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Integration analysis of potential targets and ulcerative colitis-related genes using Venn online tool (https://bioinfogp.cnb.csic.es/tools/venny/).

GO and KEGG Enrichment Analysis of Effective Targets

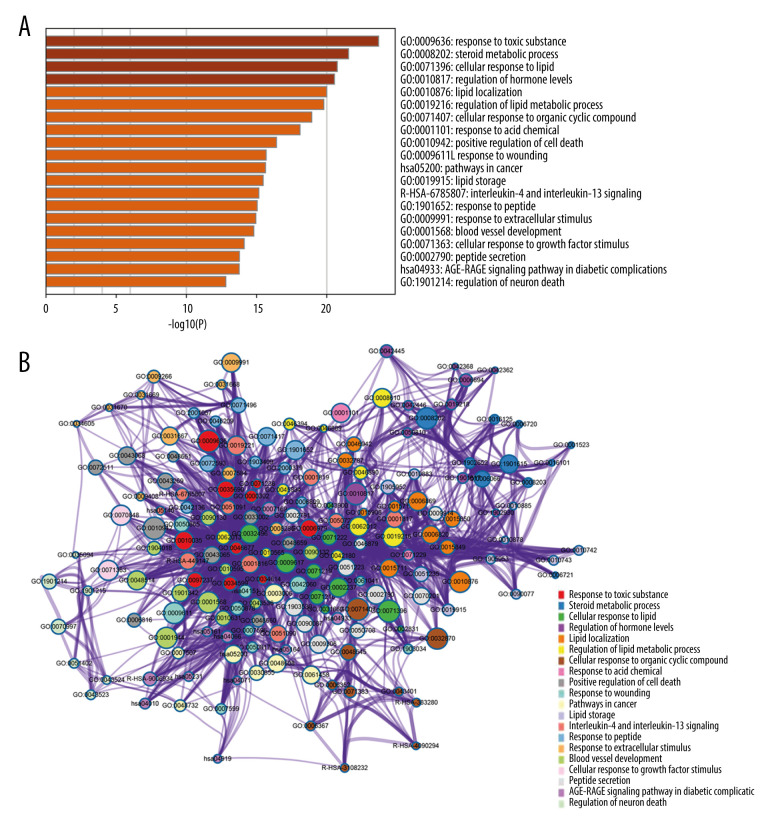

For these overlapping genes, GO-BP and pathway enrichment analyses were carried out with the following sources: GO-BP, KEGG pathway, and Reactome Gene Sets analyses. The results showed that 1146 GO-BP terms, 111 KEGG pathways, and 81 Reactome Gene Sets were significantly enriched. After the similarity clustering analysis, 77 clusters were obtained; the top 20 clusters are displayed in Figure 2A. To further investigate the relationships between the terms in each cluster, we constructed an interactive network (Figure 2B). In brief, genes were mainly enriched in several GO-BP terms, such as response to toxic substances, steroid metabolic processes, and cellular responses to lipids; and genes were primarily involved in pathways such as pathways in cancer and the AGE-RAGE signaling pathway in diabetic complications.

Figure 2. Functional enrichment analysis of target proteins by Metascape (http://metascape.org).

(A) Top 20 clusters of functional enrichment; (B) interactive network of terms. Different node color indicates different clusters, the connection indicates the gene similarity between terms, and the node size indicates the number of enriched genes.

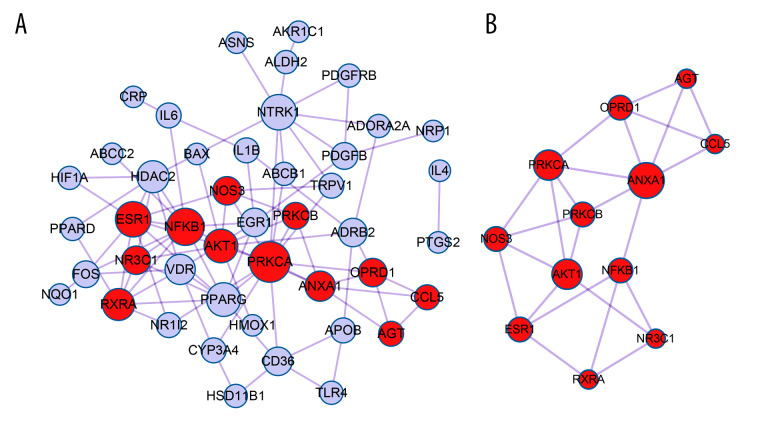

Construction of PPI Network and Module Network

To further investigate the relationship between targets, PPI analysis was performed. The PPI network was composed of 45 nodes and 87 connected edges (Figure 3A). The top 10 nodes with higher degrees were considered as hub genes, including PRKCA, NFKB1, ESR1, NTRK1, AKT1, PPARG, HDAC2, RXRA, ANXA1, and VDR. Next, the MCODE plugin was used to extract modules from the PPI network, and a significant module composed of 12 genes and 23 edges was identified (Figure 3B).

Figure 3. Construction of protein–protein interaction (PPI) network using Cytoscape (version 3.4.0, http://chianti.ucsd.edu/cytoscape-3.4.0/).

(A) Identification of PPI pair via online tool Metascape. Edge represents the protein–protein interaction and red node represents gene in module. (B) Screening of module from PPI network by using MCODE algorithm. The size of the node represents the degree value of node.

Functional enrichment analysis of the genes in the module was also conducted. GO enrichment analysis indicated that genes were significantly associated with cellular responses to lipids and hormone stimuli. Pathway analysis revealed that these genes were observably involved in the sphingolipid signaling pathway, AGE-RAGE signaling pathway in diabetic complications, and HIF-1 signaling pathway.

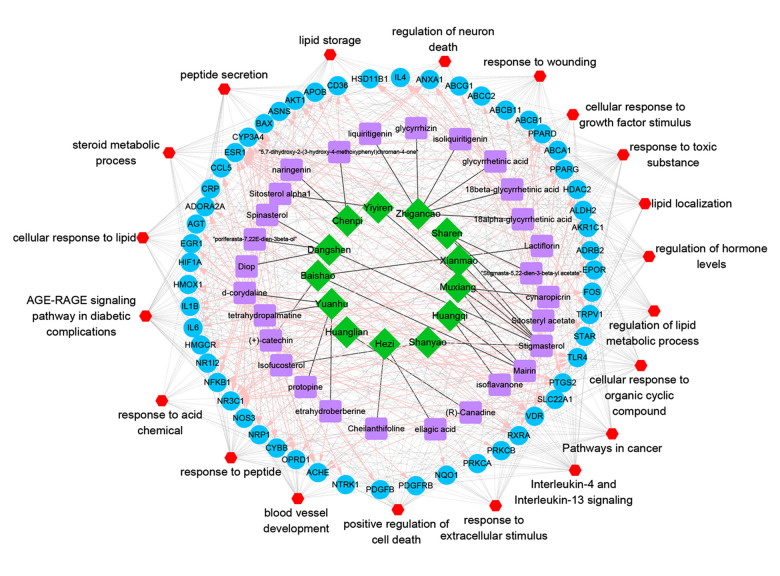

Construction of Pharmacological Network

To more intuitively represent the relationship among herbs, compounds, targets, and pathways, a pharmacological network was constructed. This network included 13 herbal medicines, 28 compounds, 54 targets, and 724 relation pairs (Figure 4). Among these, the top 5 compounds were stigmasterol, tetrahydropalmatine, mairin, 18alpha-glycyrrhetinic acid, and 18beta-glycyrrhetinic acid; the top 5 targets with the greatest number of edges included AKT1, ESR1, PTGS2, ANXA1, and IL1B; and pathways enriched by more genes primarily included interleukin-4 and interleukin-13 signaling, AGE-RAGE signaling pathway in diabetic complications, and response to peptide.

Figure 4. Construction of pharmacological network using Cytoscape (version 3.4.0).

The green diamond indicates herb, purple square indicates compound, blue circle indicates target, and red hexagon indicates KEGG pathway.

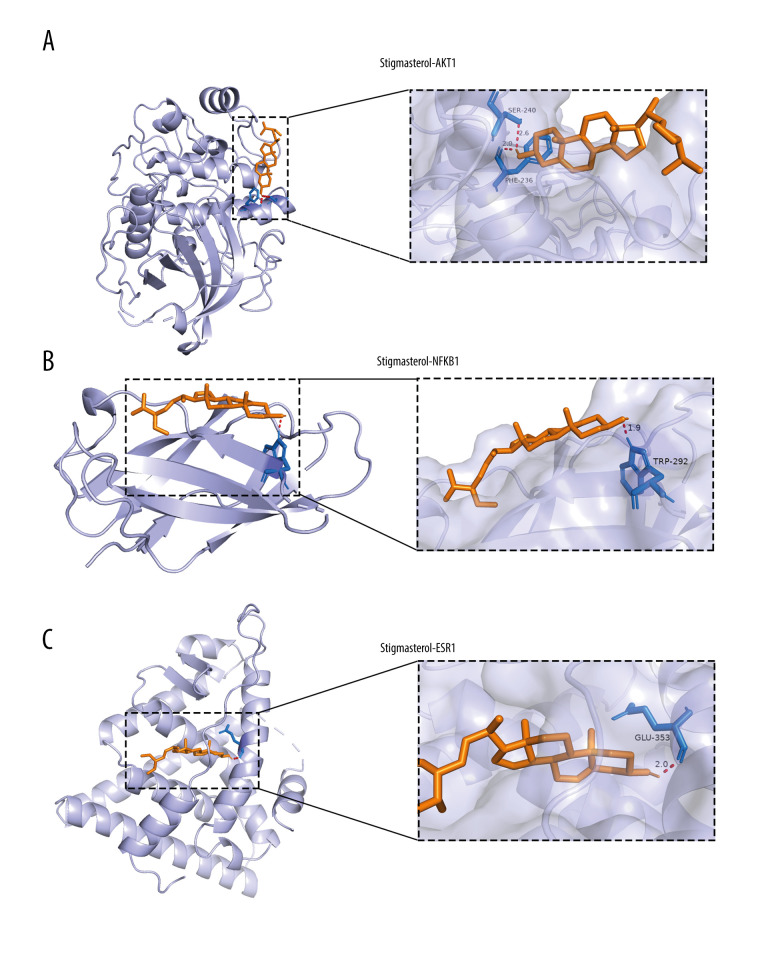

Molecular Docking Verification

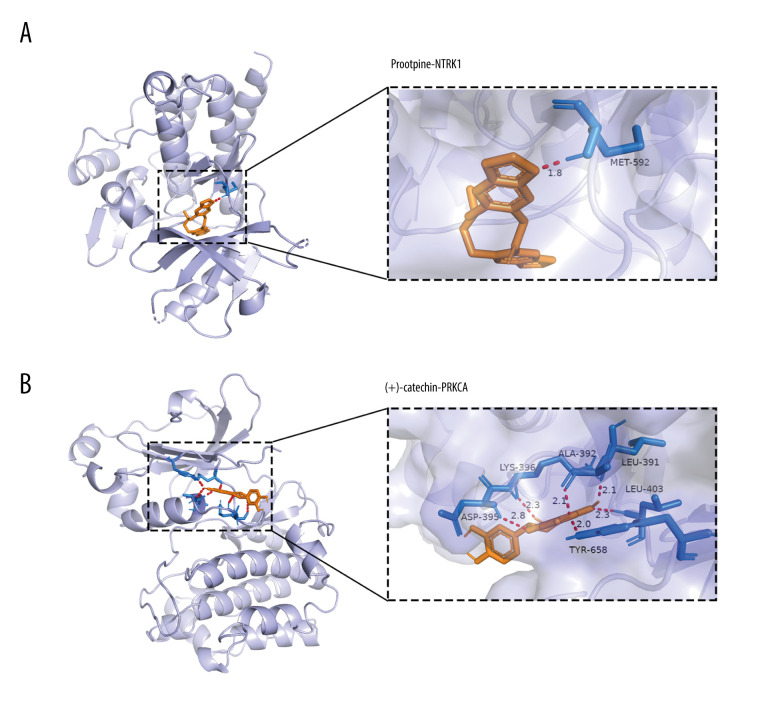

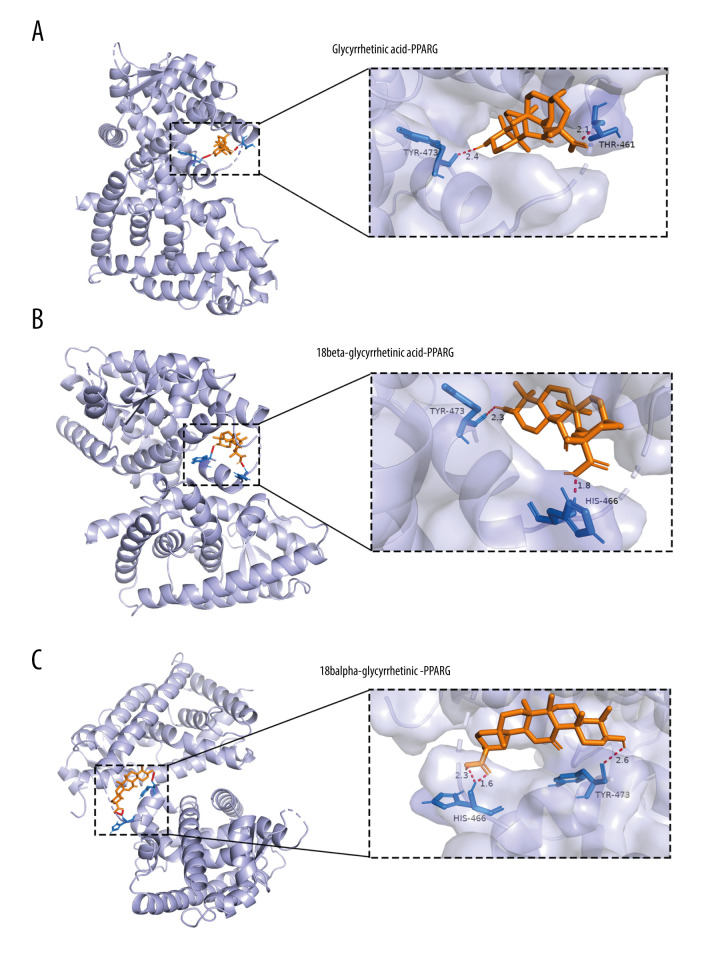

Molecular docking is an important tool in drug research and can be used to study the interactions between small ligand molecules and receptor biomacromolecules. Moreover, molecular docking can predict ligand conformation and assess binding affinity [12]. In this study, to further validate potential targets in UC treatment, molecular docking was performed on the top 6 hub genes in the PPI network (PRKCA, NFKB1, ESR1, NTRK1, AKT1, and PPARG). Specifically, drug molecules corresponding to these genes in the pharmacological network were identified. For multiple small molecules targeting the same target, we selected small molecules with higher degrees for molecular docking analysis. Finally, 6 compounds were obtained, namely, stigmasterol, protopine, (+)-catechin, 18alpha-glycyrrhetinic acid, 18beta-glycyrrhetinic acid, and glycyrrhetinic acid. Next, the molecular docking model was generated. In brief, stigmasterol bound to the active pockets of AKT1 and interacted with SER240 and PHE236 to form hydrogen bonds (Figure 5A); stigmasterol bound to NFKB1 via a hydrogen bond interaction with TRP292 (Figure 5B); and stigmasterol bound to ESR1 by interacting with GLU353 to form hydrogen bonds (Figure 5C). The binding of NTRK1 to protopine was achieved through hydrogen bound interactions with MET592 (Figure 6A); and the binding of PRKCA to (+)-catechin was predominantly through hydrogen bond interactions with ASP395, LYS396, ALA392, LEU391, LEU403, and TYR658 (Figure 6B). Furthermore, glycyrrhetinic acid bound to the active pocket of PPARG and interacted with TYR473 and THR461 to form hydrogen bonds (Figure 7A); 18beta-glycyrrhetinic acid and 18alpha-glycyrrhetinic bound to the active pocket of PPARG and interacted with HIS466 and TYR473 to form hydrogen bonds (Figure 7B, 7C).

Figure 5. Molecular docking analysis of stigmasterol with AKT1.

(A),NFKB1 (B), andESR1 (C) using AutoDock 4.2 software (Sousa, Fernandes & Ramos). Purple, orange, red, and blue represent protein receptor, small drug ligand, hydrogen bond, and amino acid residue, respectively. The length of bond is added to the bond.

Figure 6. The docking model of core active compounds withNTRK1 andPRKCA by AutoDock 4.2 software.

Protopine binds to NTRK1 (A), and (+)-catechin binds to PRKCA (B). Purple, orange, red, and blue represent protein receptor, small drug ligand, hydrogen bond, and amino acid residue, respectively. The length of bond is added to the bond.

Figure 7. Molecular docking models of glycyrrhetinic acid (A), 18beta-glycyrrhetinic acid (B), and 18alpha-glycyrrhetinic (C) binding to PPARG by AutoDock 4.2 software.

Purple, orange, red, and blue represent protein receptor, small drug ligand, hydrogen bond, and amino acid residue, respectively. The length of bond is added to the bond.

Validation of Clinical Effective of Tao Hua Decoction by Using Meta-Analysis

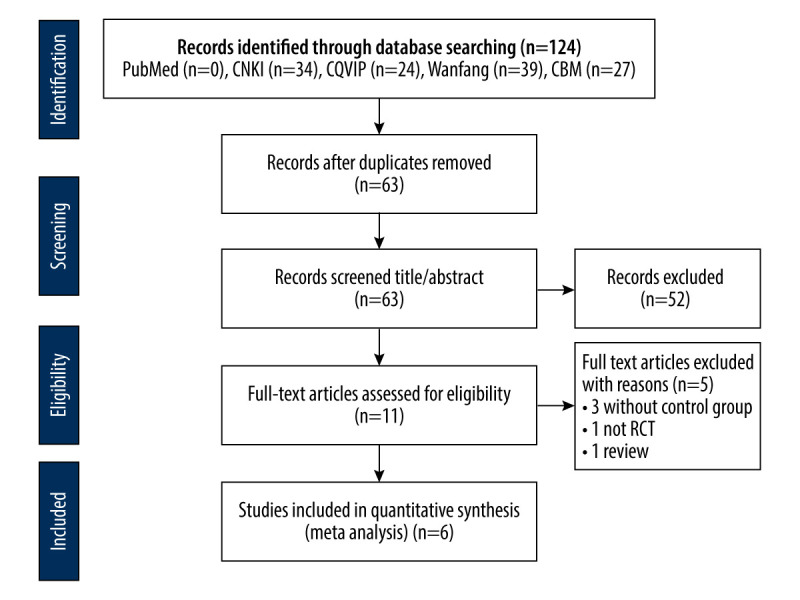

Literature Retrieval Results

The selection procedure of eligible studies is presented in Figure 8. A total of 124 articles were obtained via preliminary screening as follows: 0 from PubMed, 34 from the China National Knowledge Infrastructure, 24 from the China Science and Technology Journal database, 39 from Wanfang, and 27 from the China Biology Medicine disc. After removing duplicates, 63 articles remained. Among these, 52 articles were excluded because of failure to meet inclusion criteria after reading the titles and abstracts. Five studies that were not RCTs were subsequently eliminated. Finally, 6 RCTs were included for further meta-analysis [6,38–42].

Figure 8.

Flow chart of the research retrieval process.

Overall Characteristics of Studies

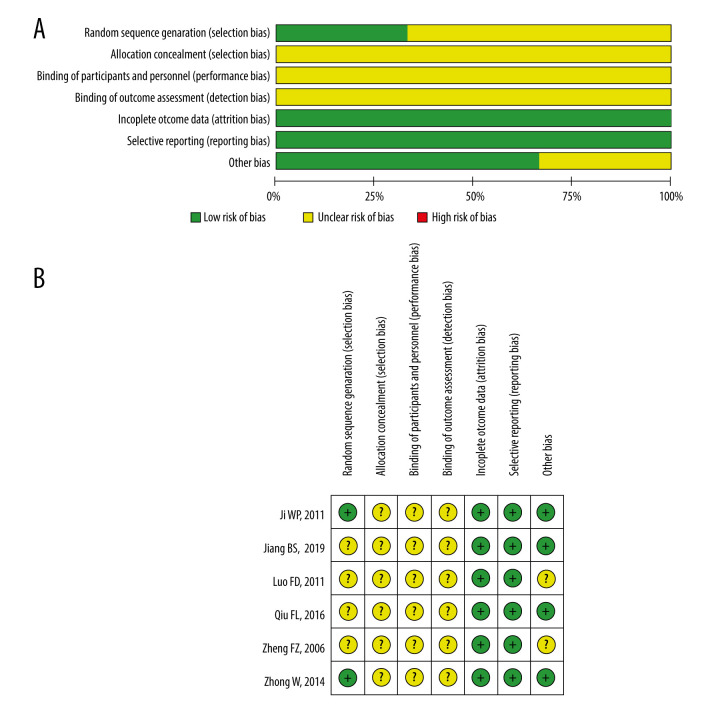

In total, 6 studies involving 580 cases (311 of experimental groups and 269 of control groups) were included in the meta-analysis. These RCTs were published in 2006 to 2019 and all were carried out in China. For each included study, there were no statistically significant differences in sex and age between the 2 groups. In the experimental group, 3 studies used Tao Hua decoction [38,40,41], and 3 studies used Shenling Baizhu powder combined with Tao Hua decoction [6,39,42]. In terms of the control group, the Western medicines used included the sulfasalazine tablet, salazine tablet, and oxalazine sodium capsule. The detailed characteristics of each study are listed in Table 1. Moreover, high risk of bias was not observed in all studies; however, more unclear risk was found. The risk of the included literature is shown in Figure 9.

Table 1.

The characteristics of all included studies.

| Study | Group | Therapeutic regimen | n, M/F | Age, years |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ji WP, 2011 | Experimental | Taohua Decoction (2 times/day, 1 month/course, 2 courses) | 52, 30/22 | 45.8±11.2 |

| Control | Sulfasalazine tablet 1 g (4 times/day, 1 month/course, 2 courses) | 34, 20/14 | 44.6±11.6 | |

| Jiang BS, 2019 | Experimental | Shenling Baizhu Powder + Taohua Decoction (2 times/day, 3 months/course, 1 course) | 57, 32/25 | 36.54±6.62 |

| Control | Salazine tablet 1g (4 times/day, 3 months/course, 1 course) | 57, 30/27 | 36.51±6.68 | |

| Luo FD, 2011 | Experimental | Shenling Baizhu Powder + Taohua Decoction (2 times/day, 10 days/course, 3 courses) | 35, NR | NR |

| Control | Sulfasalazine tablet 1–2 g (4 times/day, 10 days/course, 3 courses) | 33, NR | NR | |

| Qiu FL, 2016 | Experimental | Shenling Baizhu Powder + Taohua Decoction (2 times/day, 3 months/course, 1 course) | 60, 34/26 | 38.42±8.74 |

| Control | Salazine tablet 1 g (3 times/day, 3 months/course, 1 course) | 60, 36/24 | 39.25±8.84 | |

| Zheng FZ, 2006 | Experimental | Taohua Decoction (2 times/day, 1 month/course, 1 course) | 62, 38/24 | 37.2 |

| Control | Sulfasalazine tablet 1 g + prednisone 10 mg (4 times/day, 1 month/course, 1 course) | 40, 22/18 | 36.4 | |

| Zhong W, 2014 | Experimental | Taohua Decoction (2 times/day, 8 weeks/course, 1 course) | 45, 28/17 | 42.5±10.6 |

| Control | Oxalazine sodium capsule 1 g (4 times/day, 8 weeks/course, 1 course) | 45, 30/15 | 41.9±11.1 |

F – female; M – male; NR – not report.

Figure 9. Quality assessment of all included studies by using Cochrane Collaboration’s tool.

(A) Risk of bias graph. (B) Risk of bias summary. Green box/node represents low risk of bias, yellow box/node represents unclear risk of bias, and red box/node represents high risk of bias.

Results of Meta-Analysis

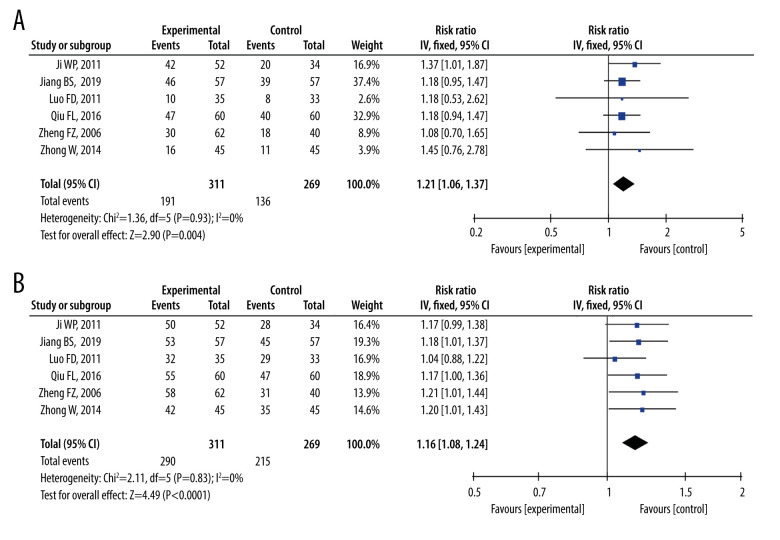

All studies reported information in CRR between the experimental groups and control groups. Due to no significant heterogeneity (I2=0%, P=0.93), a fixed effects model was selected to merge the results of CRR. The CRR was improved in the experimental group compared with the control group (RR, 1.21; 95% CI, 1.06–1.37; P=0.004; Figure 10A). In addition, 6 studies reported the ORR of patients with UC after treatment. Meta-analysis showed that patients in the experimental group had higher ORR than those in the control group (RR, 1.16; 95% CI, 1.08–1.24; P<0.001; I2=0%; P=0.83; Figure 10B). Further, the Egger test indicated that there was no significant publication bias among the included studies (CRR: P=0.672; ORR: P=0.659).

Figure 10. Forest plot of Tao Hua decoction treatment versus control for CRR (A) and ORR (B) using RevMan 5.3 (Cochrane Collaboration, Oxford, UK).

CRR – complete response rate; ORR – overall response rate.

Discussion

UC is a nonspecific chronic colitis characterized by inflammation and ulceration of the mucosa and submucosa. As UC etiology remains unknown and no effective treatment is available, this disease generally progresses to a chronic refractory relapse. Conventional treatment can lead to poor effects on multiple pro-inflammatory and safety variables of patients with UC; thus, many TCMs have been used for UC treatment [43].

In the present study, we used the network pharmacology method to identify the potential compounds and targets of JYTD. The pharmacological network revealed 28 compounds, 54 targets, and 20 pathways. Among these, the top 10 targets (PRKCA, NFKB1, ESR1, NTRK1, AKT1, PPARG, HDAC2, RXRA, ANXA1, and VDR) in the PPI network were considered as hub genes. Meanwhile, pathway analysis revealed these genes were significantly involved in the cellular response to lipids and the regulation of the lipid metabolic process. Furthermore, molecular docking indicated PRKCA, NFKB1, ESR1, NTRK1, AKT1, and PPARG had good affinity with 6 core compounds, namely stigmasterol, protopine, (+)-catechin, 18alpha-glycyrrhetinic acid, 18beta-glycyrrhetinic acid, and glycyrrhetinic acid. Moreover, meta-analysis indicated that Tao Hua decoction showed significant efficacy for treating patients with UC, and TCMs based on Tao Hua decoction treatment observably improved ORR and CRR compared with those of the control group (treatment with Western medicine).

Among the identified compounds, stigmasterol, liquiritigenin, and naringenin were regarded as key active compounds in the treatment of UC. Stigmasterol is an unsaturated phytosterol found in various medicinal plants and has pharmacological effects, such as anti-osteoarthritis, anti-tumor, and anti-inflammatory effects [44]. Feng et al [45] demonstrated that stigmasterol significantly inhibited colon cancer and decreased severe colitis also in the distal colon, suggesting that stigmasterol might improve colitis. In addition, Junior et al [46] observed that the extract of Physalis angulata L. (including stigmasterol) could regulate inflammatory mediator expression and had potential use in the treatment of inflammatory bowel disease. Liquiritigenin is the main compound of Huangqin-Tang, which is widely used to treat UC in China [47]. Also, liquiritigenin had a protective effect against colitis damage, and, in a colitis mouse model treated with liquiritigenin, inflammatory factor expression was significantly suppressed [48]. Another key compound, naringenin, is a dihydroflavonoid with multiple beneficial effects, such as antibacterial, anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, and anti-tumor effects [49]. Al-Rejaie et al [50] observed that naringenin protected UC by inhibiting inflammation and oxidation biomarkers. These studies supported our findings that these key compounds might play important role in UC treatment.

The key genes identified in the PPI network were PRKCA, NFKB1, ESR1, NTRK1, AKT1, PPARG, HDAC2, RXRA, ANXA1, and VDR. NFKB1 is an inflammatory pathway gene and its polymorphism is associated with an increased risk of inflammatory bowel disease [51,52]. ESR1, PPARG, and AKT1 were predicted targets of the Gegen-Qinlian decoction, which was used in UC treatment [53], and these targets might be considered as potential therapeutic targets for UC. Histone deacetylase (HDAC) isoforms, such as HDAC2, appeared to be specifically involved in chronic intestinal inflammation [54]. HDAC inhibitors significantly suppressed the development of inflammation and tumors and might be useful in UC treatment [55]. RXRA played an important role in regulating inflammation in acute colitis [56]. Intestinal VDR gene disruption affected phenotypic changes that might exacerbate inflammatory bowel disease [57]. Furthermore, ANXA1 expression was upregulated in inflamed intestinal mucosal tissues and used as a potential biomarker for treating inflammatory bowel disease [58]. Taken together, these genes were mainly correlated with inflammation and may be potential targets of JYTD against UC.

Moreover, our study revealed that these genes were primarily involved in the cellular response to lipids and the regulation of lipid metabolic processes. Lipids play a vital role in the pathogenesis and treatment of UC. Schneider et al [59] indicated that lipids were applied to UC therapy, and phospholipids had the potential to treat inflammatory bowel disease. Moreover, Beloqui et al [60] showed that berberine could improve colitis by inhibiting lipid peroxidation. Thus, we speculate that these targets may serve a role in UC treatment via affecting lipid metabolism-related pathways.

Molecular docking revealed the interaction between compounds and targets in the pharmacological network. Results indicated that stigmasterol bound to the active pockets of AKT1, NFKB1, and ESR1 to form hydrogen bonds; protopine bound to the active pockets of NTRK1; (+)-catechin was linked to PRKCA; glycyrrhetinic acid bound to the active pocket of PPARG; and 18beta-glycyrrhetinic acid and 18alpha-glycyrrhetinic acid bound to the active pocket of PPARG. Andújar et al [61] found that catechin, as a major phenolic, had anti-inflammatory properties against UC in mice. As a parent constituent of Gegen-Qinlian decoction, glycyrrhetinic acid was effective against inflammatory intestinal diseases such as UC [62]. These results suggested that active JYTD compounds could effectively treat UC by binding core genes.

Further, meta-analysis systematically collected the available data and measured the current clinical evidence supporting the efficacy of JYTD in providing benefits in UC treatment. Unfortunately, only a few studies reported the direct relationship between JYTD and UC. Nevertheless, JYTD was derived from the basis of “Tao Hua decoction”; therefore, we used “Tao Hua decoction and UC” as keywords to screen relevant studies. Finally, 6 RCTs were included, and from these, the TCMs in the experimental group included “Tao Hua decoction” and “Shenling Baizhu powder combined with Tao Hua decoction”. Although the meta-analysis did not include a JYTD-related study, the key herbs in these 2 TCMs were all contained in JYTD, such as DS, BZ, HQ, CSZ, GJ, and JM. Meta-analysis results revealed that these TCMs based on the Tao Hua decoction could significantly improve the therapeutic effect of UC. Importantly, there was no significant heterogeneity among included studies; thus, the studies had good consistency and the results were reliable. These results provide a clue for further research related to JYTD-based therapy in UC treatment.

Notably, there are limitations in the current study. First, not all compounds from JYTD, such as JM, are identified in the TCMSP database, and therefore several key compounds and their targets may be missing. Second, all targets are obtained via predicting, and molecular docking analysis can only reveal the binding between compounds and targets, while it cannot reflect whether gene expression is inhibited or promoted. Third, the dose effect is very important in the clinic, and the network pharmacology approach cannot offer dose-effect outcomes. Fourth, gut microbiota can transform drugs and herbal compounds and impact their efficacy and toxicity [63]; however, network pharmacology cannot accurately predict the effects of drugs on the gut microbiota. Moreover, the function of gut microbiota varies from person to person, and thus personalized research is required to reveal a drug response in depth. Finally, although a meta-analysis was used to verify the pharmacological results, the number of included studies as well as their sample sizes were small, and few studies directly reported the role of JYTD in UC. In addition, the biological function of identified targets and compounds has not been explored. Therefore, in vivo experiments and clinical trials should be performed to validate our findings.

Conclusions

In conclusion, network pharmacological analysis and meta-analysis revealed that JYTD had therapeutic effects on patients with UC partly by regulating multiple compounds, targets, and lipid metabolism-related pathways. Meanwhile, molecular docking results further revealed that several JYTD compounds exhibited a good affinity for their core targets. Our study provides a new perspective for further elucidating the mechanisms of JYTD in UC treatment.

Supplementary Material

The flow chart of this analysis.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: None declared

Department and Institution Where Work Was Done

The work was done in the Department of Traditional Chinese Medicine, Taian City Central Hospital, Taian, Shandong, China.

Declaration of Figures’ Authenticity

All figures submitted have been created by the authors, who confirm that the images are original with no duplication and have not been previously published in whole or in part.

Financial support: None declared

References

- 1.Zhai H, Huang W, Liu A, et al. Current smoking improves ulcerative colitis patients’ disease behaviour in the northwest of China. Prz Gastroenterol. 2017;12:286–90. doi: 10.5114/pg.2017.72104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhang M, Wang X, Han MK, et al. Oral administration of ginger-derived nanolipids loaded with siRNA as a novel approach for efficient siRNA drug delivery to treat ulcerative colitis. Nanomedicine. 2017;12:1927–43. doi: 10.2217/nnm-2017-0196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sandborn WJ, Feagan BG, Wolf DC, et al. Ozanimod induction and maintenance treatment for ulcerative colitis. New Engl J Med. 2016;374:1754–62. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1513248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sands BE, Sandborn WJ, Panaccione R, et al. Ustekinumab as induction and maintenance therapy for ulcerative colitis. New Engl J Med. 2019;381:1201–14. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1900750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lichtenstein GR, Rutgeerts P. Importance of mucosal healing in ulcerative colitis. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2010;16:338–46. doi: 10.1002/ibd.20997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Qiu F. [Ulcerative colitis treated with Tao Hua Decoction and Shenlingbaizhu Powder in 60 cases]. Zhejiang Journal of Traditional Chinese Medicine. 2016;51:113. [in Chinese] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhang Y-L, Cai L-T, Qi J-Y, et al. Gut microbiota contributes to the distinction between two traditional Chinese medicine syndromes of ulcerative colitis. World J Gastroenterol. 2019;25:3242–55. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v25.i25.3242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhou Z, Wang W. Clinical observation on Yiyi Fuzi Baijiang powder for treatment of patients with ulcerative colitis accompanied by yang-deficiency of spleen and kidney: A report of 80 cases. Chin J Integr Med. 2017;24:419–22. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kou F-S, Shi L, Li J-X, et al. Clinical evaluation of traditional Chinese medicine on mild active ulcerative colitis: A multi-center, randomized, double-blind, controlled trial. Medicine (Baltimore) 2020;99:e21903. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000021903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Huang T, Chen J, Zhang L, Hao B. Traditional Chinese medicine understanding of ulcerative colitis. J Drug Deliv Ther. 2019;9:390–92. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Li S, Zhang B. Traditional Chinese medicine network pharmacology: Theory, methodology and application. Chin J Nat Med. 2013;11:110–20. doi: 10.1016/S1875-5364(13)60037-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Morris GM, Lim-Wilby M. Molecular docking Molecular modeling of proteins. Springer; 2008. pp. 365–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Meng X-Y, Zhang H-X, Mezei M, Cui M. Molecular docking: A powerful approach for structure-based drug discovery. Curr Comput Aided Drug Des. 2011;7:146–57. doi: 10.2174/157340911795677602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ru J, Li P, Wang J, et al. TCMSP: A database of systems pharmacology for drug discovery from herbal medicines. J Cheminformatics. 2014;6:13. doi: 10.1186/1758-2946-6-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Xue R, Fang Z, Zhang M, et al. TCMID: traditional Chinese medicine integrative database for herb molecular mechanism analysis. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;41:D1089–95. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks1100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Madden JC. In silico approaches for predicting ADME properties Recent advances in QSAR studies. Springer; 2010. pp. 283–304. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Xu X, Zhang W, Huang C, et al. A novel chemometric method for the prediction of human oral bioavailability. Int J Mol Sci. 2012;13:6964–82. doi: 10.3390/ijms13066964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chen ML, Shah V, Patnaik R, et al. Bioavailability and bioequivalence: An FDA regulatory overview. Pharm Res. 2001;18:1645–50. doi: 10.1023/a:1013319408893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tao Q, Du J, Li X, et al. Network pharmacology and molecular docking analysis on molecular targets and mechanisms of Huashi Baidu formula in the treatment of COVID-19. Drug Dev Ind Pharm. 2020;46:1345–53. doi: 10.1080/03639045.2020.1788070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tian S, Wang J, Li Y, et al. Drug-likeness analysis of traditional Chinese medicines: Prediction of drug-likeness using machine learning approaches. Mol Pharm. 2012;9:2875–86. doi: 10.1021/mp300198d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liu Z, Guo F, Wang Y, et al. BATMAN-TCM: A bioinformatics analysis tool for molecular mechanism of traditional Chinese medicine. Sci Rep. 2016;6:21146. doi: 10.1038/srep21146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ma JX, Wang B, Li HS, et al. Uncovering the mechanisms of leech and centipede granules in the treatment of diabetes mellitus-induced erectile dysfunction utilising network pharmacology. J Ethnopharmacol. 2021;265:113358. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2020.113358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Davis AP, Grondin CJ, Johnson RJ, et al. The comparative toxicogenomics database: Update 2019. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019;47:D948–54. doi: 10.1093/nar/gky868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Barabási A-L, Albert R. Emergence of scaling in random networks. Science. 1999;286:509–12. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5439.509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li H, Liang S. Local network topology in human protein interaction data predicts functional association. PLoS One. 2009;4:e6410. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0006410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhou Y, Zhou B, Pache L, et al. Metascape provides a biologist-oriented resource for the analysis of systems-level datasets. Nat Commun. 2019;10:1–10. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-09234-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shannon P, Markiel A, Ozier O, et al. Cytoscape: A software environment for integrated models of biomolecular interaction networks. Genome Res. 2003;13:2498–504. doi: 10.1101/gr.1239303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chatr-Aryamontri A, Oughtred R, Boucher L, et al. The BioGRID interaction database: 2017 update. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017;45:D369–79. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw1102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Li T, Wernersson R, Hansen RB, et al. A scored human protein–protein interaction network to catalyze genomic interpretation. Nat Methods. 2017;14:61. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.4083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Türei D, Korcsmáros T, Saez-Rodriguez J. OmniPath: Guidelines and gateway for literature-curated signaling pathway resources. Nat Methods. 2016;13:966. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.4077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bader GD, Hogue CW. An automated method for finding molecular complexes in large protein interaction networks. BMC Bioinform. 2003;4:2. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-4-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sussman JL, Lin D, Jiang J, et al. Protein Data Bank (PDB): Database of three-dimensional structural information of biological macromolecules. Acta Crystallogr D. 1998;54:1078–84. doi: 10.1107/s0907444998009378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kim S, Chen J, Cheng T, et al. PubChem 2019 update: Improved access to chemical data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019;47:D1102–9. doi: 10.1093/nar/gky1033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Morris GM, Huey R, Lindstrom W, et al. AutoDock4 and AutoDockTools4: Automated docking with selective receptor flexibility. J Comput Chem. 2009;30:2785–91. doi: 10.1002/jcc.21256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate healthcare interventions: explanation and elaboration. Br Med J. 2009;339:b2700. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b2700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Higgins JPT, Altman DG, Gøtzsche PC, et al. The Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. Br Med J. 2011;343:d5928. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d5928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Higgins JPT, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. Br Med J. 2003;327:557–60. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ji W. [Modified Tao Hua Decoction in treating 52 cases of ulcerative colitis]. TCM Research. 2011;24:39–41. [in Chinese] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jiang B. [Observation on the therapeutic effect of Tao Hua Decoction and Shenlingbaizhu Powder on ulcerative colitis]. Guide of China Medicine. 2019;17:223. [in Chinese] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zheng F. [Treatment of 62 cases of ulcerative colitis with Tao Hua decoction and enema]. Forum on Traditional Chinese Medicine. 2006;5:8. [in Chinese] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhong W, Deng Z, Fu Z. [Observation on the curative effect of Jiawei Taohua Decoction combined with Kangfuxin Liquid in the treatment of active ulcerative colitis]. Zhejiang Practical Medicine. 2014;19:104–6. [in Chinese] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Luo F, Kong P, Tang X. [Shenling Baizhu Powder and Taohua Decoction retention enema for ulcerative colitis]. Journal of Practical Traditional Chinese Internal Medicine. 2011;25:54–55. [in Chinese] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cao S-Y, Ye S-J, Wang W-W, et al. Progress in active compounds effective on ulcerative colitis from Chinese medicines. Chin J Nat Med. 2019;17:81–102. doi: 10.1016/S1875-5364(19)30012-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kaur N, Chaudhary J, Jain A, Kishore L. Stigmasterol: A comprehensive review. International J Pharm Sci Res. 2011;2:2259. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Feng S, Dai Z, Liu A, et al. β-Sitosterol and stigmasterol ameliorate dextran sulfate sodium-induced colitis in mice fed a high fat Western-style diet. J Funct Foods. 2017;8:4179–86. doi: 10.1039/c7fo00375g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Junior LDA, Quaglio AEV, de Almeida Costa CAR, Di Stasi LC. Intestinal anti-inflammatory activity of Ground Cherry (Physalis angulata L.) standardized CO2 phytopharmaceutical preparation. World J Gastroenterol. 2017;23:4369. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v23.i24.4369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wang C, Tang X, Zhang L. Huangqin-Tang and ingredients in modulating the pathogenesis of ulcerative colitis. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2017;2017:7016468. doi: 10.1155/2017/7016468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Min JK, Lee CH, Jang SE, et al. Amelioration of trinitrobenzene sulfonic acid-induced colitis in mice by liquiritigenin. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;30:858–65. doi: 10.1111/jgh.12812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Huang B, Hu P, Hu A, et al. Naringenin attenuates carotid restenosis in rats after balloon injury through its anti-inflammation and anti-oxidative effects via the RIP1-RIP3-MLKL signaling pathway. Eur J Pharmacol. 2019;855:167–74. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2019.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Al-Rejaie SS, Abuohashish HM, Al-Enazi MM, et al. Protective effect of naringenin on acetic acid-induced ulcerative colitis in rats. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19:5633. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v19.i34.5633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bank S, Andersen PS, Burisch J, et al. Polymorphisms in the inflammatory pathway genes TLR2, TLR4, TLR9, LY96, NFKBIA, NFKB1, TNFA, TNFRSF1A, IL6R, IL10, IL23R, PTPN22, and PPARG are associated with susceptibility of inflammatory bowel disease in a Danish cohort. PLoS One. 2014;9:e98815. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0098815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Fan Y, Yu W, Ye P, et al. NFKB1 insertion/deletion promoter polymorphism increases the risk of advanced ovarian cancer in a Chinese population. DNA Cell Biol. 2011;30:241–45. doi: 10.1089/dna.2010.1107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wei M, Li H, Li Q, et al. based on network pharmacology to explore the molecular targets and Mechanisms of Gegen Qinlian Decoction for the treatment of ulcerative colitis. Biomed Res Int. 2020;2020:5217405. doi: 10.1155/2020/5217405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Glauben R, Sonnenberg E, Zeitz M, Siegmund B. HDAC inhibitors in models of inflammation-related tumorigenesis. Cancer Lett. 2009;280:154–59. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2008.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Glauben R, Siegmund B. Inhibition of histone deacetylases in inflammatory bowel diseases. Mol Med. 2011;17:426–33. doi: 10.2119/molmed.2011.00069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Knackstedt R, Shaoli S, Moseley V, Wargovich M. The importance of the retinoid X receptor alpha in modulating inflammatory signaling in acute murine colitis. Dig Dis Sci. 2014;59:753–59. doi: 10.1007/s10620-013-2902-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kim J-H, Yamaori S, Tanabe T, et al. Implication of intestinal VDR deficiency in inflammatory bowel disease. Biochim Biophys Acta Gen Subj. 2013;1830:2118–28. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2012.09.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.de Paula-Silva M, Barrios BE, Macció-Maretto L, et al. Role of the protein annexin A1 on the efficacy of anti-TNF treatment in a murine model of acute colitis. Biochem Pharmacol. 2016;115:104–13. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2016.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Schneider H, Braun A, Füllekrug J, et al. Lipid based therapy for ulcerative colitis – modulation of intestinal mucus membrane phospholipids as a tool to influence inflammation. Int J Mol Sci. 2010;11:4149–64. doi: 10.3390/ijms11104149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Beloqui A, Coco R, Alhouayek M, et al. Budesonide-loaded nanostructured lipid carriers reduce inflammation in murine DSS-induced colitis. Int J Pharm. 2013;454:775–83. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2013.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Andújar I, Recio MC, Giner RM, et al. Inhibition of ulcerative colitis in mice after oral administration of a polyphenol-enriched cocoa extract is mediated by the inhibition of STAT1 and STAT3 phosphorylation in colon cells. J Agric Food Chem. 2011;59:6474–83. doi: 10.1021/jf2008925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lu J-Z, Ye D, Ma B-L. Constituents, pharmacokinetics, and pharmacology of decoction. Front Pharmacol. 2021;12:668418. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2021.668418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Feng W, Liu J, Ao H, et al. Targeting gut microbiota for precision medicine: Focusing on the efficacy and toxicity of drugs. Theranostics. 2020;10:11278–301. doi: 10.7150/thno.47289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

The flow chart of this analysis.