Abstract

PCR assays for the diagnosis of systemic candidiasis can be performed either on serum or on whole blood, but results obtained with the two kinds of samples have never been formally compared. Thus we designed a nested PCR assay in which five specific inner pairs of primers were used to amplify specific targets on the rRNA genes of Candida albicans, C. tropicalis, C. parapsilosis, C. krusei, and C. glabrata. In vitro, the lower limit of detection of each nested PCR assay was 1 fg of purified DNA from the corresponding Candida species. In rabbits with candidemia of 120 minutes’ duration following intravenous (i.v.) injection of 108 CFU of C. albicans, the sensitivities of the PCR in serum and whole blood were not significantly different (93 versus 86%). In other rabbits, injected with only 105 CFU of C. albicans, detection of candidemia by culture was possible for only 1 min, whereas DNA could be detected by PCR in whole blood and in serum for 15 and 150 min, respectively. PCR was more often positive in serum than in whole blood in 40 culture-negative samples (27 versus 7%; P < 0.05%). Lastly, experiments with rabbits injected i.v. with 20 or 200 μg of purified C. albicans DNA showed that PCRs were positive in serum from 30 to at least 120 min after injection, suggesting that the clearance of free DNA is slow. These results suggest that serum is the sample of choice, which should be used preferentially over whole blood for the diagnosis of systemic candidiasis by PCR.

Systemic candidiasis is a major nosocomial infection in patients given immunosuppressive chemotherapy for cancer treatment or organ transplantation and in patients undergoing heart or abdominal surgery (18). Patients with candidemia have a poorer prognosis than those with nosocomial bacteremia (19, 25). Mortality rates among those with systemic candidiasis remain high, ranging from 50 to 80%, despite adequate treatment (11, 26). In the absence of pathognomonic signs or symptoms of systemic candidiasis, diagnosis is usually based on the isolation of Candida species from blood cultures or tissue biopsy specimens. However, since the sensitivity of blood cultures for diagnosis of systemic candidiasis is low at the early stage of the infection, and since it has been shown that the prognosis is better when treatment is started early, it is usually recommended that antifungal therapy be started as soon as a strong suspicion of systemic candidiasis exists (9, 16, 20). On the other hand, such empiric antifungal therapy may be unnecessarily toxic and costly, and it may increase the selective pressure towards more-resistant Candida species (29). Thus, efforts have been made to develop more-sensitive methods for the earliest possible diagnosis of systemic candidiasis. One of these involves the PCR method in which different targets of Candida DNA have been tested: either single-copy genes such as the actin (15), chitin synthase (14), HSP 90 (7), and lanosterol-14 α-demethylase-encoding genes (3, 4) or multicopy genes such as the gene coding for rRNA (12, 13, 22, 23). Hybridization (8, 12, 22, 23) and nested PCR (4, 6) experiments have been used to identify all the amplimers at the Candida species level. The best of these assays are those which can identify all the species most commonly involved in candidemia: Candida albicans, C. tropicalis, C. krusei, C. parapsilosis, and C. glabrata (8, 12–14, 22).

It has been demonstrated that PCR can be performed either on whole-blood samples (3, 4, 10) or on serum samples (5, 6, 15). However, the efficiencies of the same PCR assay applied simultaneously to serum or whole blood have never been formally compared. These might not be equivalent, since the DNAs present in the two types of samples are probably different in origin. Indeed, only free template DNA should be detectable in serum samples, since fungal cells are eliminated by centrifugation without having been lysed to release intracellular DNA (6). By contrast, when whole-blood samples are used, both free DNA and intracellular DNA could be present when the sample is drawn from the patient. However, because of the presence in blood of PCR inhibitors, such as hemoglobin, a decontamination step, including lysis of blood cells and washing, is performed first. These steps probably eliminate free Candida DNA, leaving intracellular Candida DNA as the sole possible target for the PCR assay (3, 4, 8, 23). Thus, depending on the sample used, the origin of the detected DNA probably varies. This may result in a difference in the sensitivity of the assay and in its clinical significance. To our knowledge these issues have not been fully investigated. This is why, in the present study, our efforts have been focused on that question. We have used a rabbit model of experimental candidemia specifically developed in this laboratory. We used DNA coding for the 5.8S rRNA and the adjacent internal transcribed spacer (ITS) as the target for amplification, and we have compared the positivities of the PCR on whole-blood and serum specimens, using blood cultures as the reference assay.

(Part of this work was presented at the 37th Interscience Conference on Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy, Toronto, Ontario, Canada, 28 September to 1 October 1997 [2a]).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Candida organisms.

C. albicans ATCC 2091 was used for both in vitro and in vivo experiments, whereas C. tropicalis ATCC 66029, C. glabrata ATCC 66032, C. krusei IP 208-52, C. parapsilosis IP 205-52, and clinical isolates of C. albicans (n = 18), C. tropicalis (n = 3), C. glabrata (n = 6), C. parapsilosis (n = 3), and C. krusei (n = 2) were used for the in vitro experiments only.

Control DNA.

DNAs from different species, including bacterial species (Proteus mirabilis, Enterobacter cloacae, Escherichia coli, Staphylococcus aureus, and Mycobacterium tuberculosis), parasites (Toxoplasma gondii), and non-Candida fungal species (Aspergillus fumigatus, Cryptococcus neoformans, Pneumocystis carinii, Trichophyton rubrum, and Microsporum canis), and human DNA prepared from amniotic fluid were used to determine the specificity of the primers designed to amplify Candida DNAs.

Preparation of Candida cells.

Candida cells from stationary phase cultures in yeast extract-peptone-dextrose broth (18 h at 37°C, with shaking) were washed twice in phosphate-buffered saline and counted in a hemocytometer. Counts were confirmed by agar plate counts.

DNA extractions.

Candida DNA, extracted from broth culture as previously described (21), was stored at −80°C until use. Purified Candida DNA was quantified by using a GeneQuant RNA/DNA calculator (Pharmacia Biotech, Orsay, France).

DNA was extracted from whole blood as previously described (23), with slight modifications. Briefly, 100 μl of whole blood was mixed with 100 μl of blood cell lysis buffer (0.32 M sucrose, 10 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.5], 5 mM MgCl2, and 1% Triton X-100) and centrifuged at 16,000 × g for 5 min. The pellet was resuspended in 200 μl of lysis buffer to which 7 μl of DNase I (10 mg/ml; Boehringer Mannheim, Meylan, France) was added, in order to eliminate free DNA. The mixture was incubated for 1 h at 37°C, and the DNase was then inactivated by heating for 10 min at 85°C. After centrifugation, the pellet was resuspended in 200 μl of TEG buffer (50 mM glucose, 25 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8], and 10 mM EDTA) containing 1.5 μl of lyticase (900 U/ml; Sigma, Saint Quentin Fallavier, France), and incubated for 1 h at 37°C. Three microliters of pronase E (15 mg/ml; Sigma) and 10 μl of 10% sodium dodecyl sulfate were added, and incubation was continued for another hour at 37°C. DNA was then extracted with phenol-chloroform-isoamyl alcohol, precipitated with 2 volumes of ethanol, and dissolved in 40 μl of sterile water.

DNA was extracted from serum as previously described (6), also with slight modifications. Briefly, proteinase K (Sigma) and sodium dodecyl sulfate were added to 100 μl of serum at final concentrations of 15 μg/ml and 1%, respectively. The mixture was incubated for 1 h at 37°C and then boiled for 10 min to inactivate proteinase K. After phenol-chloroform-isoamyl alcohol extraction and ethanol precipitation, DNA was dissolved in 40 μl of sterile water.

Oligonucleotide primers and PCR.

The fungus-specific universal primers ITS1 (5′TCCGTAGGTGAACCTGCGG3′) and ITS4 (5′TCCTCCGCTTATTGATATGC 3′) (27) were used as outer primers to amplify the intergenic transcribed spacer regions of Candida species rRNAs. As indicated in Table 1, specific inner primers were designed for C. albicans, C. parapsilosis, C. tropicalis, and C. krusei on the basis of the ITS1–ITS4 sequences derived from GenBank (respective accession numbers: L47111, L47109, L47112, and L47113). For C. glabrata, inner primers were designed from the ITS1–ITS3 sequence (GenBank accession no. L47110). The sequences of the specific inner primers used in the nested PCR, and the sizes of the amplification products, are indicated in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Oligonucleotides used in nested PCR

| Species (accession no.) and primers | Sequence (5′→3′) | Nucleotide positiona | Fragment size (bp) | Tempb (°C) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| C. albicans (L47111) | ||||

| Oligonucleotide 1: CAL1 | AACTTGCTTTGGCGGTGGGC | 73 | 386 | 66 |

| Oligonucleotide 2: CAL3 | TGGACGTTACCGCCGCAAGC | 439 | ||

| C. tropicalis (L47112) | ||||

| Oligonucleotide 1: CTR1 | ATTTCTTTGGTGGCGGGAGC | 73 | 373 | 57 |

| Oligonucleotide 2: CTR3 | GGCCACTAGCAAAATAAGCG | 426 | ||

| C. glabrata (L47110) | ||||

| Oligonucleotide 1: CGL1 | ATGCTATTTCTCCTGCCTGC | 128 | 234 | 57 |

| Oligonucleotide 2: CGL3 | TGNATCCACTGGGAGAACTC | 342 | ||

| C. parapsilosis (L47109) | ||||

| Oligonucleotide 1: CPA1 | GCCAGAGATTANACTCAACC | 123 | 336 | 55 |

| Oligonucleotide 2: CPA3 | GGAAGAAGTTTTGGAGTTTG | 439 | ||

| C. krusei (L47113) | ||||

| Oligonucleotide 1: CKR2 | ACTACACTGCGTGAGCGGAA | 43 | 360 | 55 |

| Oligonucleotide 2: CKR3 | AAAAAGTCTAGTTCGCTCGG | 383 | ||

| Internal control | ||||

| Oligonucleotide 1: M1 | AACTTGCTTTGGCGGTGGGCCCTCGGTTTCCTTCTGGTA | 491 | 66 | |

| Oligonucleotide 2: M3 | TGGACGTTACCGCCGCAAGCGCGAACCTCCCGACTTGCG |

In the ITS sequence.

Annealing temperature.

PCR amplification was performed in a final volume of 25 μl by using a reaction mixture containing 50 mM KCl, 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.3), 1.5 mM MgCl2, 100 μM each deoxynucleoside triphosphate, and 1.25 U of Taq DNA polymerase (Boehringer Mannheim). For the first PCR, 10 pmol of each outer primer was mixed either with 5 μl of DNA prepared from whole blood or serum or with 1 μl of purified DNA. A 9600 thermal cycler (Perkin-Elmer, Saint Quentin-en-Yvelines, France) was used with the following temperature cycles: 95°C for 5 min; then 30 cycles of 20 s at 95°C, 15 s at 55°C, and 65 s at 72°C; and a final cycle of PCR extension at 72°C for 5 min. For the nested PCR, 1 μl of the product obtained from the first amplification and 10 pmol of each inner primer was mixed in fresh reaction mixture. The second amplification was performed under the conditions described above, except for the annealing temperatures, which were specific for each pair of inner primers, as indicated in Table 1. The nested PCR products were submitted to electrophoresis on a 1.5% agarose gel containing ethidium bromide. Amplicon carryover was prevented by using aerosol-guarded pipette tips (ATGC Biotechnologie, Noisy Le Grand, France) and by carefully separating the DNA extraction area from the areas in which PCR reaction mixtures were prepared and the amplification and electrophoresis were performed. Appropriate negative controls, i.e., the DNA extraction and reaction mixture controls, were tested for each amplification reaction.

To avoid false interpretation of negative PCRs in rabbit blood samples, a positive internal control was designed. Two 39-mer composite primers containing M13mp18 phage sequences flanked at their 5′ ends by C. albicans inner primers (Table 1) were synthesized (Genset, Paris, France). PCR was performed by using these composite primers on M13mp18 template DNA to generate an M13mp18 fragment with a C. albicans sequence for each 5′ position. When 90 pg of this amplified product was added to the nested PCR reaction mixture, a 491-bp fragment was generated in the absence of inhibitors.

In vitro evaluation of the sensitivity and specificity of Candida nested PCR.

To determine the detection limit for the purified DNAs of five Candida species, each nested PCR was performed with 1 pg and with 100, 10, 1, and 0.1 fg of purified Candida DNA from each species tested. To check the inter-Candida species specificity of the five nested PCRs, each nested PCR was performed with 100 ng of Candida DNA from the other four species. Candida species specificity was then evaluated by applying the five nested PCRs to 100 ng of control DNA.

To determine the smallest number of Candida cells for which Candida DNA was detectable by nested PCR, different amounts of C. albicans and C. tropicalis cells were artificially inoculated into human and rabbit blood samples so that each sample contained 104 to 1 CFU/ml.

Rabbit model.

Fifteen male New Zealand rabbits weighing 2 to 2.5 kg were housed in individual cages and anesthetized by injection of 15 mg of sodium pentobarbital/kg of body weight into the marginal ear vein. Tracheotomy was performed, and the lungs were mechanically ventilated. Anesthesia and muscle paralysis were maintained by intermittent intravenous injection of 12.5 mg of pentobarbital and 0.2 mg of pancuronium. Throughout the study period, rabbits received 8 ml of 0.9% sodium chloride solution/h and 2 ml of 8.4% sodium bicarbonate solution/h, by continuous intravenous infusion. A 14-gauge cannula was inserted into the right carotid artery to measure mean arterial pressure, and a jugular vein catheter was inserted under sterile conditions for volume resuscitation and blood sampling for PCR and cultures.

Experimental protocol.

Rabbits were injected in the marginal ear vein either with a 1-ml bolus of 108 (five rabbits) or 105 (six rabbits) C. albicans cells or with 200 (two rabbits) or 20 (two rabbits) μg of purified C. albicans DNA. Before injection and 1, 5, 15, 30, 60, 90, 120, 150, and 180 min thereafter, blood samples were collected in both EDTA-coated and dry tubes. One milliliter of the blood collected in the EDTA-coated tube was cultured on Sabouraud-chloramphenicol agar plates in order to count Candida cells. Another milliliter of the blood collected in the EDTA-coated tube and 500 μl of the serum obtained from the dry tube were used for independent DNA extractions and PCR assays. All PCRs and cultures were performed in duplicate.

Sequencing of the C. albicans fragment amplified by nested PCR.

The fragment generated by inner primers of C. albicans from either purified DNA of C. albicans ATCC 2091 or infected rabbit sera was sequenced from both ends with primers CAL1 and CAL3 (Genome Express, Lyon, France). These sequences were compared to the C. albicans sequence available from GenBank (accession no. L47111).

Statistical analysis.

The differences between PCR positivity rates on serum and on whole blood were tested by using the chi-square test with Yates’ correction at the 5% level of significance.

RESULTS

In vitro sensitivity and specificity of Candida nested PCR.

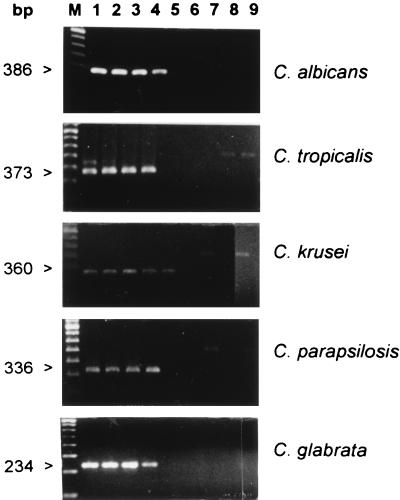

As indicated in Fig. 1, the limits of purified Candida DNA detection by nested PCR ranged from 1 to 0.1 fg, depending on the Candida species. By inoculation of human and rabbit blood samples with either C. albicans or C. tropicalis cells, a PCR assay was able to detect the Candida DNA extracted from as few as 100 CFU/ml for C. albicans and 30 CFU/ml for C. tropicalis. There was no difference between the results of experiments performed with human and rabbit blood (data not shown).

FIG. 1.

Sensitivities and specificities of DNA detection by species-specific nested PCRs of purified DNA from C. albicans, C. tropicalis, C. krusei, C. parapsilosis, and C. glabrata with ethidium bromide staining on agarose gel electrophoresis. Shown are nested PCR products obtained with each species-specific inner pair of primers from different amounts of template DNA from the corresponding Candida species (lane 1, 1 pg; lane 2, 100 fg; lane 3, 10 fg; lane 4, 1 fg; lane 5, 0.1 fg). The size of the specific amplified fragment is indicated on the left. The specificity of the C. albicans primers was tested on 100 ng of purified DNA from C. tropicalis (lane 6), C. glabrata (lane 7), C. krusei (lane 8), and C. parapsilosis (lane 9). The specificity of the C. tropicalis primers was tested on 100 ng of purified DNA from C. albicans (lane 6), C. glabrata (lane 7), C. krusei (lane 8), and C. parapsilosis (lane 9). The specificity of the C. krusei primers was tested on 100 ng of purified DNA from C. albicans (lane 6), C. tropicalis (lane 7), C. glabrata (lane 8), and C. parapsilosis (lane 9). The specificity of the C. parapsilosis primers was tested on 100 ng of purified DNA from C. albicans (lane 6), C. tropicalis (lane 7), C. glabrata (lane 8), and C. krusei (lane 9). The specificity of the C. glabrata primers was tested on 100 ng of purified DNA of C. albicans (lane 6), C. tropicalis (lane 7), C. krusei (lane 8), and C. parapsilosis (lane 9). In these experiments, the amplified products generated by the Candida universal primers (ITS1 and ITS4) in the first reaction are sometimes visible. M, molecular weight marker.

The observed specificities of the species-specific Candida nested PCRs were all 100%. Indeed, the inner primers designed for a given Candida species never amplified DNA from any of the other four Candida species (Fig. 1 and Table 2) or from any of the other fungal, bacterial, or parasitic species tested. No cross-reactivity with human DNA was observed (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Specificity of Candida species nested PCR

| Species | No. of positive PCRs/no. of DNA specimens

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C. albicans | C. tropicalis | C. parapsilosis | C. glabrata | C. krusei | |

| C. albicans | 18/18a | 0/18 | 0/18 | 0/18 | 0/18 |

| C. tropicalis | 0/3 | 3/3a | 0/3 | 0/3 | 0/3 |

| C. parapsilosis | 0/3 | 0/3 | 3/3a | 0/3 | 0/3 |

| C. glabrata | 0/6 | 0/6 | 0/6 | 6/6a | 0/6 |

| C. krusei | 0/2 | 0/2 | 0/2 | 0/2 | 2/2a |

| A. fumigatus | 0/5 | 0/5 | 0/5 | 0/5 | 0/5 |

| C. neoformans | 0/1 | 0/1 | 0/1 | 0/1 | 0/1 |

| P. carinii | 0/2 | 0/2 | 0/2 | 0/2 | 0/2 |

| M. canis | 0/2 | 0/2 | 0/2 | 0/2 | 0/2 |

| T. rubrum | 0/1 | 0/1 | 0/1 | 0/1 | 0/1 |

| T. gondii | 0/1 | 0/1 | 0/1 | 0/1 | 0/1 |

| P. mirabilis | 0/2 | 0/2 | 0/2 | 0/2 | 0/2 |

| E. coli | 0/2 | 0/2 | 0/2 | 0/2 | 0/2 |

| S. aureus | 0/2 | 0/2 | 0/2 | 0/2 | 0/2 |

| E. cloacae | 0/1 | 0/1 | 0/1 | 0/1 | 0/1 |

| M. tuberculosis | 0/1 | 0/1 | 0/1 | 0/1 | 0/1 |

| Human | 0/5 | 0/5 | 0/5 | 0/5 | 0/5 |

Homospecific interactions.

Sensitivity of C. albicans nested PCR applied to whole blood and serum, compared to that of quantitative blood cultures in the rabbit model.

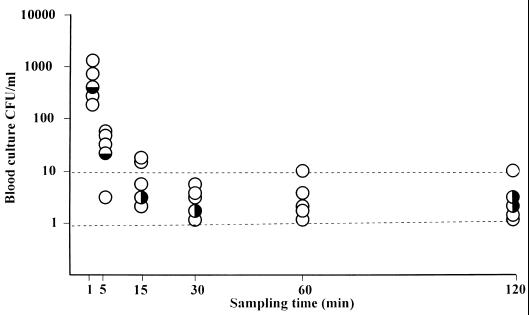

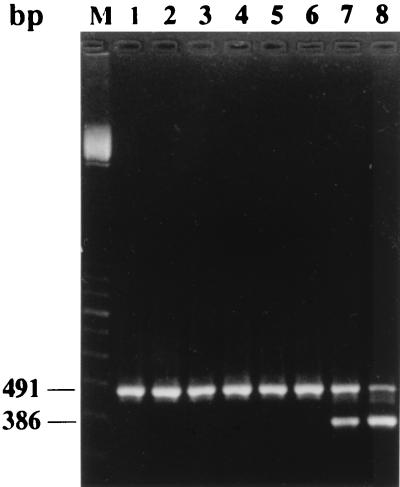

In the five rabbits injected with 108 CFU of C. albicans ATCC 2091, results of quantitative blood cultures showed that 90% of the microorganisms present in the blood 1 min after injection were cleared within 4 min. Blood cultures then remained positive, with a low concentration of C. albicans (1 to 17 CFU/ml) during the remaining 115 min of the experiment. Nested PCRs performed on whole blood were positive in 26 of 30 (86%) samples tested, comprising all of the 11 samples in which the counts of C. albicans were greater than 10 CFU/ml, and 15 of the 19 samples in which the counts were equal to or lower than 10 CFU/ml (Fig. 2). When PCR was performed on serum, a total of 28 of 30 (93%) samples were positive. The two negative serum samples were from the same rabbit and were drawn at 1 and 5 min after injection, when cell concentrations of C. albicans were high (Fig. 2). Negative PCRs were not due to the presence of inhibitors in whole-blood or serum samples, since the internal positive PCR controls were always positive (Fig. 3).

FIG. 2.

Sensitivity of quantitative blood cultures compared to that of nested PCR performed on whole blood and on serum from five rabbits infected with 108 CFU of C. albicans. Each rabbit is represented by a circle at each sampling time. ○, positive nested PCR in both whole blood and serum; ◒, positive nested PCR in whole blood and negative nested PCR in serum; ◑, negative nested PCR in whole blood and positive nested PCR in serum.

FIG. 3.

Coamplification of internal PCR control and rabbit blood samples. Lanes 1, 2, 3, and 4, whole-blood samples; lanes 5 and 6, serum samples which exhibited a negative C. albicans nested PCR; lanes 7 and 8, two whole-blood samples for which this PCR was positive. Amplification of the internal control is indicated by the presence of a 491-bp fragment, and amplification of C. albicans DNA in blood is indicated by the presence of a 386-bp fragment. M, molecular weight marker.

When a smaller inoculum of 105 CFU of C. albicans ATCC 2091 was injected, a candidemia of brief duration was observed in five rabbits and no candidemia was observed in one rabbit at 1 min postinjection, and the PCRs performed on whole blood and on sera were positive in 4 of 6 and 3 of 6 of these rabbits, respectively (Table 3). The blood cultures remained negative thereafter, but the PCRs performed on whole blood were still positive in two rabbits and one rabbit at 5 and 15 min postinjection, respectively (Table 3). In addition, the PCRs performed on sera were positive for 11 of the 35 samples drawn from 5 to 150 min postinjection but were always negative for samples drawn 180 min after injection. Overall, among the 40 culture-negative samples drawn later than 1 min after injection, 3 (7%) were positive when PCR was performed on whole blood and 11 (27%) were positive when PCR was performed on serum (P < 0.05%).

TABLE 3.

C. albicans detection from quantitative blood cultures and from nested PCR performed on whole-blood and serum samples of rabbits infected with 105 CFU of C. albicans

| Method | No. positive/no. tested at the following sampling time (min):

|

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 5 | 15 | 30 | 60 | 120 | 150 | 180 | Total | |

| Blood culture | 5/6a | 0/6 | 0/6 | 0/6 | 0/6 | 0/6 | 0/5 | 0/5 | 5/46 |

| PCR, whole blood | 4/6 | 2/6 | 1/6 | 0/6 | 0/6 | 0/6 | 0/5 | 0/5 | 7/46 |

| PCR, serum | 3/6 | 1/6 | 3/6 | 3/6 | 3/6 | 0/6 | 1/5 | 0/5 | 14/46 |

Individual counts were 20, 8, 2, 2, 1, and 0 CFU/ml.

Sequence comparison.

The sequences of the 386-bp fragments amplified from C. albicans ATCC 2091 and from the sera of infected rabbits were strictly homologous. They differed from the corresponding GenBank C. albicans sequence (accession no. L47111) only by the insertion of a G base between positions 353 and 354 (99.7% homology).

Purified Candida DNA clearance from rabbit blood using nested PCR.

When purified C. albicans DNA was directly injected into rabbits at a dose of 200 μg, the PCRs were positive in serum samples from 1 to at least 120 min. They were positive from 1 to at least 30 min when only 20 μg was injected (Table 4).

TABLE 4.

PCR evaluation of serum clearance of different amounts of purified C. albicans DNA injected intravenously into four rabbits

| Rabbit no. | Quantity of purified DNA (μg) | Resulta at the following sampling time (min):

|

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1 | 5 | 15 | 30 | 60 | 90 | 120 | 150 | 180 | ||

| 1 | 200 | − | + | + | + | + | + | NA | + | NA | NA |

| 2 | 200 | − | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | NA | − |

| 3 | 20 | − | + | + | + | + | − | − | + | − | − |

| 4 | 20 | − | + | + | + | + | − | − | − | − | − |

NA; not available; +, positive nested PCR; −, negative nested PCR.

DISCUSSION

We designed a nested Candida PCR assay in which an amplified fragment of the Candida ITS repeated region was used as a template for five different inner primer pairs, which were chosen for specific amplification of the DNAs of the five species most frequently causing human candidiasis (2, 28). The in vitro specificity of our five PCRs was 100%. The sensitivity was similar to that published elsewhere for PCR targeting repeated genes and using specific probe hybridization assays for species differentiation (8, 12).

For in vivo evaluation, we used an experimental model of infection in rabbits in which candidemia was studied over a period of 120 min after injection of a 108-CFU C. albicans bolus. This inoculum was similar to that used in a previously described model of experimental candidemia in rabbits (1). Because of the large volumes of the blood samples that could be drawn from rabbits, we could precisely compare the sensitivities of our nested PCR in whole blood and serum. Such a strict comparison had not and probably could not have been performed in studies of experimental candidiasis in smaller laboratory animals (6, 15, 17). Compared to quantitative blood cultures, the overall observed sensitivity of our PCR assay was 86% for whole blood and 93% for serum. The PCR assay was negative in four whole-blood and two serum samples which were positive in culture. The sampling times at which the PCR was negative in whole blood differed from those at which it was negative in serum, possibly due to the different origins of the template DNA. Considering, first, that template DNA in whole blood originated from DNA extracted ex vivo from Candida cells circulating in the blood and, second, that the four PCRs with false-negative results in whole blood were performed on samples with low Candida counts (5, 4, 2, and 2 CFU/ml), negativity may reflect difficulty in extracting DNA ex vivo by cell lysis, as reported elsewhere (23, 24). PCR was positive in 28 of 30 serum samples for which there was no such ex vivo cell lysis included in the protocol, suggesting that DNA could be physiologically released in serum, which is in agreement with results published by others (5, 6, 15). The only two negative serum samples were from the same animal and were drawn early, at 1 and 5 min after bolus injection, suggesting that the amount of DNA physiologically released during the first minutes after injection was too small to be detectable by PCR.

In previously published clinical studies evaluating the sensitivity of PCR assays in the diagnosis of candidemia, samples for PCR were drawn at the same time as blood cultures and were frozen, and only those yielding positive cultures were later assayed by PCR (4, 10, 15). These samples were either whole blood (4, 10) or serum (15), but the two kinds of samples were never tested in the same study. In one study, the sensitivity of a C. albicans- and C. glabrata-specific nested PCR performed on whole blood was 90% (19 of 21 positive blood cultures tested) (4). In another study, in which a C. albicans-specific probe was used for the detection of Candida DNA amplified from whole blood, all samples tested were positive by PCR, but they all had Candida counts equal to or greater than 20 CFU/ml (10). In our work the only four false-negative PCR results on whole blood were from samples with Candida cell counts below 10 CFU/ml. By contrast, the 93% sensitivity that we found for PCR performed on serum samples from candidemic rabbits was higher than the 79% sensitivity reported by others using a single-copy gene (actin gene) target for a PCR assay performed on serum samples from candidemic patients (15). We concluded from this first set of experiments in rabbits injected with a large Candida inoculum (108 CFU) that the PCR assay that we designed had a high sensitivity for detection of DNA both in whole-blood samples and in serum samples drawn during the culture-positive candidemic periods.

When we injected the rabbits with only 105 CFU of C. albicans, blood cultures were positive only during the 1st min following injection, but PCRs performed on whole blood and on sera remained positive for a longer period, confirming that PCR was more sensitive than cultures in diagnosing candidemia, as reported both for murine (6, 15, 17, 24) and for human (5, 6, 15) candidemia. However, we also showed that during the culture-negative period, the PCRs performed on sera remained positive longer than those performed on whole blood. This could be explained by the different origins of template DNA amplified in the two types of samples. We suggest that the positivity of whole-blood PCRs performed on culture-negative samples was due to the presence of noncultivable Candida cells, as previously reported (17, 23). The positivity of PCR on serum samples long after cultures and PCR on whole blood had become negative suggested that the clearance of free DNA was slower than that of either cultivable or noncultivable Candida cells. A slow clearance of free DNA was also observed in the rabbits that we injected with purified C. albicans DNA.

In conclusion, our results showed that serum samples should be used preferentially over whole blood to diagnose candidemia by PCR. They also confirmed that Candida template DNA which can be detected by PCR during the candidemic episodes corresponds both to DNA from intact cultivable or noncultivable Candida cells, and to free DNA released in vivo. Whether the same will be observed in neutropenic and postsurgery patients who are at high risk of Candida infection is now being investigated in a prospective clinical trial.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported in part by grant CRC95238 from Assistance Publique—Hôpitaux de Paris and by a grant from the Ligue Nationale Française contre le Cancer.

REFERENCE

- 1.Baine W B, Koenig M G, Goodman J S. Clearance of Candida albicans from the bloodstream of rabbits. Infect Immun. 1974;10:1420–1425. doi: 10.1128/iai.10.6.1420-1425.1974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barns S M, Lane D J, Sogin M L, Bibeau C, Weinsburg W G. Evolutionary relationships among pathogenic Candida species and relatives. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:2250–2255. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.7.2250-2255.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2a.Bougnoux M E, Dupont C, Mateo J, Saulnier P, Payen D, Nicolas-Chanoine M H. Abstracts of the 37th Interscience Conference on Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. Washington, D.C: American Society for Microbiology; 1997. Rapid diagnosis of candidemia by DNA amplification applied to serum abstr. D-131; p. 106. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Buchman T G, Rossier M, Merz W G, Charache P. Detection of surgical pathogens by in vitro DNA amplifications. Part 1. Rapid identification of Candida albicans by in vitro amplification of a fungus-specific gene. Surgery. 1990;108:338–347. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Burgener-Kairuz P, Zuber J P, Jaunin P, Buchman T G, Billie J, Rossier M. Rapid detection and identification of Candida albicans and Torulopsis (Candida) glabrata in clinical specimens by species-specific nested PCR amplification of a cytochrome P-450 lanosterol-α-demethylase (L1A1) gene fragment. J Clin Microbiol. 1994;32:1902–1907. doi: 10.1128/jcm.32.8.1902-1907.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Burnie J P, Golbang N, Matthews R C. Semiquantitative polymerase chain reaction enzyme immunoassay for diagnosis of disseminated candidiasis. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 1997;16:346–350. doi: 10.1007/BF01726361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chryssanthou E, Andersson B, Petrini B, Löfdahl S, Tollemar J. Detection of Candida albicans DNA in serum by polymerase chain reaction. Scand J Infect Dis. 1994;26:479–485. doi: 10.3109/00365549409008623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Crampin A C, Matthews R C. Application of the polymerase chain reaction to the diagnosis of candidosis by amplification of an HSP 90 gene fragment. J Med Microbiol. 1993;39:233–238. doi: 10.1099/00222615-39-3-233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Einsele H, Hebart H, Roller G, Löffler J, Rothenhofer I, Müller C A, Bowden R A, van Burik J-A, Engelhard D, Kanz L, Schumacher U. Detection and identification of fungal pathogens in blood by using molecular probes. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:1353–1360. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.6.1353-1360.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer and International Antimicrobial Therapy Cooperative Group. Empiric antifungal therapy in febrile granulocytopenic patients. Am J Med. 1989;86:668–672. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(89)90441-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Flahaut M, Sanglard D, Monod M, Bille J, Rossier M. Rapid detection of Candida albicans in clinical samples by DNA amplification of common regions from C. albicans-secreted aspartic proteinase genes. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:395–401. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.2.395-401.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fraser V J, Jones M, Dunkel J, Storfer S, Medoff G, Dunagan W C. Candidemia in a tertiary care hospital: epidemiology, risk factors, and predictors of mortality. Clin Infect Dis. 1992;15:414–421. doi: 10.1093/clind/15.3.414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fujita S I, Lasker B A, Lott T J, Reiss E, Morrison C J. Microtitration plate enzyme immunoassay to detect PCR-amplified DNA from Candida species in blood. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:962–967. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.4.962-967.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Haynes K A, Westerneng T J, Fell J W, Moens W. Rapid detection and identification of pathogenic fungi by polymerase chain reaction amplification of large subunit ribosomal DNA. J Med Vet Mycol. 1995;33:319–325. doi: 10.1080/02681219580000641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jordan J A. PCR identification of four medically important Candida species by using a single primer pair. J Clin Microbiol. 1994;32:2962–2967. doi: 10.1128/jcm.32.12.2962-2967.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kan V L. Polymerase chain reaction for the diagnosis of candidemia. J Infect Dis. 1993;168:779–783. doi: 10.1093/infdis/168.3.779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Karp J E, Merz W G, Churache P. Response to empiric amphotericin B during antileukemic therapy-induced granulocytopenia. Rev Infect Dis. 1991;13:592–599. doi: 10.1093/clinids/13.4.592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Makimura K, Murayama S Y, Yamaguchi H. Detection of a wide range of medically important fungi by the polymerase chain reaction. J Med Microbiol. 1994;40:358–364. doi: 10.1099/00222615-40-5-358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pfaller M A. Nosocomial candidiasis: emerging species, reservoirs, and modes of transmission. Clin Infect Dis. 1996;22:S89–S94. doi: 10.1093/clinids/22.supplement_2.s89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pittet D, Monod M, Suter P M, Frenk E, Auckenthaler R. Candida colonization and subsequent infections in critically ill surgical patients. Ann Surg. 1994;220:751–758. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199412000-00008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pizzo P A. Management of fever in patients with cancer and treatment-induced neutropenia. N Engl J Med. 1993;328:1323–1332. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199305063281808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Robert F, Lebreton F, Bougnoux M-E, Paugam A, Wassermann D, Schlotterer M, Tourte-Schaefer C, Dupouy-Camet J. Use of random amplified polymorphic DNA as a typing method for Candida albicans in epidemiological surveillance of a burn unit. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:2366–2371. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.9.2366-2371.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shin J H, Notle F S, Morrison C J. Rapid identification of Candida species in blood cultures by a clinically useful PCR method. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:1454–1459. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.6.1454-1459.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.van Deventer A J M, Goessens W H F, van Belkum A, van Vliet H J A, van Etten E W M, Verbrugh H A. Improved detection of Candida albicans by PCR in blood of neutropenic mice with systemic candidiasis. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:625–628. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.3.625-628.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.van Deventer A J M, Goessens W H F, van Belkum A, van Vliet J A, van Etten W M, Verbrugh H A. PCR monitoring of response to liposomal amphotericin B treatment of systemic candidiasis in neutropenic mice. J Clin Microbiol. 1996;34:25–28. doi: 10.1128/jcm.34.1.25-28.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Weinstein M P, Towns M L, Quartey S M, Mirrett S, Reimer L G, Parmigiani G, Barth Reller L. The clinical significance of positive blood cultures in the 1990s: a prospective comprehensive evaluation of the microbiology, epidemiology, and outcome of bacteremia and fungemia in adults. Clin Infect Dis. 1997;24:584–602. doi: 10.1093/clind/24.4.584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wey S B, Mori M, Pfaller M A, Woolson R F, Wenzel R P. Hospital-acquired candidemia: the attributable mortality and excess length of stay. Arch Intern Med. 1988;148:2642–2645. doi: 10.1001/archinte.148.12.2642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.White T J, Burns T D, Lee S B, Taylor J W. Amplification and direct sequencing of fungal ribosomal RNA genes for phylogenetics. In: Innis M A, Gelfand D H, Sninsky J J, White T J, editors. PCR protocols. A guide to methods and applications. San Diego, Calif: Academic Press, Inc.; 1990. pp. 315–322. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wingard J R. Importance of Candida species other than C. albicans as pathogens in oncology patients. Clin Infect Dis. 1995;20:115–125. doi: 10.1093/clinids/20.1.115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wingard J R. Infections due to resistant Candida species in patients with cancer who are receiving chemotherapy. Clin Infect Dis. 1994;19:S49–S53. doi: 10.1093/clinids/19.supplement_1.s49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]