Abstract

Objective

With the development of 75% of mental health disorders before age 25, it is alarming that service use among youth is so low. Little theoretically driven research has explored the decision-making process youth make when accessing services. This study utilized a decision-making framework, the Unified Theory of Behavior (UTB), to understand service use among youth attending Foundry, a network of integrated youth services centres designed to support the health and wellbeing of youth.

Methods

Forty-one participants were recruited from one Foundry centre in an urban community in Canada. Semi-structured interviews with participants aged 15 – 24 explored the relationship between UTB constructs and service use. Youth and parent advisory teams were engaged in the research process. Analysts used content analysis methodology to develop a taxonomy of the top categories for each construct.

Results

Categories with the most salient and rich content were reported for each construct. The impact of emotions on service use was most commonly discussed in relation to the framework. The UTB constructs ‘self-efficacy’ and ‘knowledge’ were found to be interrelated. Differences in UTB categories emerged by symptom severity. Findings pointed towards a dynamic nature of service use, whereby service use experiences, may lead youth to consider future decisions surrounding service use within Foundry.

Conclusions

This study contributes to a new understanding of integrated youth services utilization. The results can help shape the development of interventions to increase service access and retention, in addition to informing the design of systems of care that are accessible to all.

Keywords: youth, mental health, decision-making, integrated youth services, unified theory of behavior, service use

Résumé

Objectif

En tenant compte de ce que le développement de 75 % des troubles de santé mentale a lieu avant l’âge de 25 ans, il est alarmant que l’utilisation des services chez les jeunes soit si faible. Peu de recherche menée théoriquement a exploré le processus décisionnel que font les jeunes quand ils accèdent à des services. La présente étude a utilisé un cadre décisionnel, la théorie unifiée du comportement (TUC), pour comprendre l’utilisation des services chez les jeunes qui fréquentent Foundry, un réseau de centres de services intégrés pour les jeunes, conçu pour soutenir la santé et le bien-être des jeunes.

Méthodes

Quarante-et-un participants ont été recrutés dans un centre Foundry d’une communauté urbaine du Canada. Des interviews semi-structurées de participants de 15 à 24 ans ont exploré la relation entre les concepts TUC et l’utilisation des services. Les équipes de consultation jeunes-parents étaient engagées au processus de recherche. Les analystes ont utilisé la méthodologie de l’analyse du contenu pour développer une taxonomie des meilleures catégories pour chaque notion.

Résultats

Les catégories ayant le contenu le plus saillant et le plus riche ont été rapportées pour chaque notion. L’effet des émotions sur l’utilisation des services était le plus souvent discuté en relation au cadre. Les notions « auto-efficacité » et « connaissance » de la TUC ont été jugées inter-reliées. Les différences dans les catégories TUC ont émergé par la gravité des symptômes. Les résultats indiquaient une nature dynamique de l’utilisation des services, par laquelle les expériences d’utilisation des services peuvent mener les jeunes à considérer de futures décisions concernant l’utilisation des services dans Founndry.

Conclusions

La présente étude contribue à une nouvelle compréhension de l’utilisation des services intégrés pour les jeunes. Les résultats peuvent aider à donner forme au développement d’interventions afin d’accroître l’accès aux services et la rétention de ceux-ci, en plus d’éclairer la conception de systèmes de soins accessibles à tous.

Mots clés: jeunes, santé mentale, processus décisionnel, services intégrés pour les jeunes, théorie unifiée du comportement, utilisation des services

Introduction

Adolescence and young adulthood are important developmental periods where both psychosocial and neurobiological changes occur, yet the coinciding emergence of mental health disorders during this period can disrupt critical milestones in a young person’s life (1). Research has shown that 50% of mental disorders develop by age 14, and 75% of mental disorders develop before the age of 25 (2,3). Canadian youth aged 15 to 24 have the highest rates of mental illness and/or substance use disorders than any other age group (4). Untreated mental health challenges can lead to increased risk of severe mental health disorders later in life (1). Despite these alarming statistics, only 20% of youth receive appropriate treatment (5,6).

At this time, there is little theoretically driven research exploring service use decision-making among Canadian youth seeking services. Theory-driven empirical research helps inform meaningful research questions grounded in the data (7). The following study addresses this gap by applying the Unified Theory of Behavior (UTB) (8) a health behavior change theory, to examine decision-making among youth accessing mental health services from an integrated youth health services centre in Western Canada called Foundry. Foundry is a youth service initiative that has a network of 11 centres offering integrated care services such as primary care, mental health, substance use, physical and sexual health, peer support, social services, and virtual care to youth aged 12–24. Foundry aims to improve the health and wellness of all young people and families (9).

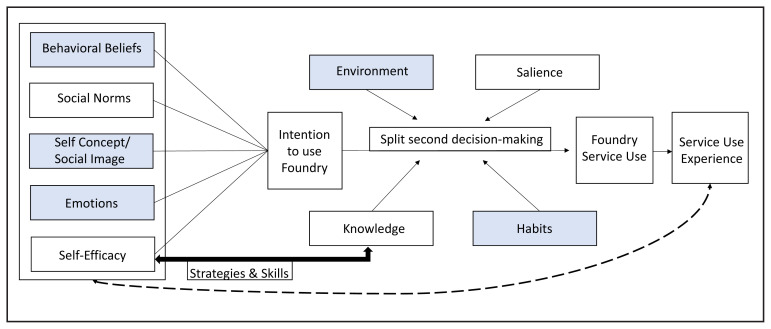

The Unified Theory of Behavior (8) is a framework that integrates five theories from health and social psychology including the Reasoned Action Model (10), the Health Belief Model (11,12), Social Learning Theory (13), Theories of Subjective Culture (14), and Emotion Regulation theories (15). It is based on the proposition that a youth’s behavior is influenced by their intentions to perform a behavior (16). It identifies five constructs that determine behavioral intentions: behavioral beliefs, social norms, self-concept/social image, emotions, and self-efficacy. Additionally, there are four moderator constructs that can either impede or facilitate the relationship between intentions and service use behavior: environment, knowledge, salience, habits. Finally, a more recently added construct to the framework is split-second decision-making (16). See Table 1 for definitions of each UTB construct.

Table 1.

Unified Theory of Behavior constructs and questions

| Construct | Definition | Example of Questions |

|---|---|---|

| Intentions | ||

|

| ||

| Behavioral beliefs | The benefits and drawbacks that youth associate with service use. | What are some benefits/drawbacks of seeking mental health services from the clinic now and for the next month? |

| Social Norms | Whether or not social supports (e.g. family/friends) approve or disapprove of a youth accessing services. | Are there important people in your life that support/don’t support you seeking mental health services at the clinic now and for the next month? |

| Self-Concept/ Social Image | Youth may be influenced by the type of youth they imagine accesses (or not) mental health services. | Now we want you to think of young people that may/would not use mental health services at the clinic or a similar type of mental health service now and for the next month. How would you describe them? |

| Emotions | The emotional reactions that youth have when considering accessing services. | We want to know if you have any feelings when you think of coming to the clinic now and for the next month. |

| Self-Efficacy (combined with knowledge) | Whether or not youth feel they can be successful in accessing services. | Please describe what type of strategies you use/will use to come to the clinic now and for the next month. |

|

| ||

| Moderators of intention-behavior | ||

|

| ||

| Knowledge (combined with skills) | Available knowledge used to facilitate service use. | Please describe what type of skills you use/will use to come to the clinic now and for the next month. |

| Environment | Barriers or facilitators in the environment that influence service use. | Please list any circumstances that would make it easier/ more difficult for you to come to the clinic now and for the next 6 months. |

| Salience | Cues in the environment to facilitate service use. | Are there any types of reminders that can be used to help you come to the clinic now and the next month? |

| Habits | Automatic processes that impact whether a youth may access services. | Please describe any habits that might lead you to not come to the clinic now and for the next month. |

| Split-second decision-making | Youth confronted with a situation last minute that gets in the way of them accessing services despite previous intention to access. | Is there anything that would make you change your mind about coming to the clinic now and for the next month? |

The majority of research focusing on the pathways to care for youth has been among those experiencing early psychosis (17), on more general barriers and facilitators to service use (18,19), and about the instrumental influence of informal supports (e.g. family, friends) in youth intentions to seek (or not) mental health services (20). Less focus is placed on bringing together multiple factors that may impede or facilitate service use under one holistic framework. More recently, the UTB has been used to understand mental health service use among young adults with mood disorders (21), at clinical high-risk for psychosis (22), and with Black adolescents and their caregivers (23). The current study builds on these previous findings, while being the first study to explore the relationship between decision-making and service use among Canadian youth accessing Foundry. This service setting is similar to other youth integrated service models across across Canada and in the world, such as Youth Wellness Hubs Ontario, headspace in Australia, Jigsaw in Ireland, or allcove in the United States providing integrated primary care, mental health, substance use, peer support, and work/study support (24). This study builds off a growing movement in Canada to engage patient partners in all levels of research. Canada’s Strategy for Patient-Oriented Patient Engagement Framework (SPOR/SPOR2) emphasizes the importance of patient partners actively collaborating in health service research (25). Through collaboration, the quality of research is improved by asking more relevant research questions, improving feasibility of the study, and ensuring that the research aligns with the priorities of young people (26,27). In this study, youth and parent advisory groups were involved in the research process to add perspective and context. The purpose of this study was to apply the Unified Theory of Behavior (UTB) to understand service use decision-making among youth attending a Foundry centre.

Methods

The current study is addressing the second aim of a multi-method qualitative study seeking to: 1) develop a grounded theory framework of mental health service use, and 2) apply the Unified Theory of Behavior (UTB) to understand mental health service decisions among youth accessing one Foundry centre. Purposive sampling (28) was used to recruit youth between the ages of 14–24 that had accessed mental health services at one Foundry centre in an urban Canadian city. Youth were not included in the sample if they were actively psychotic, under the influence of a substance, or in visible distress at the time of the interview. Theoretical sampling was also utilized to ensure a range of ages and gender identities were represented. This was important as preliminary findings from the grounded theory study revealed gender identities and age differences in help-seeking experiences. Recruitment was conducted between the years 2018–2020.

Youth and parent advisory groups at the Foundry centre were consulted, which led to development of several recruitment methods and strategies to target diverse populations in research (e.g. youth under 19, male, non-binary and transgender youth) (29). These methods included: 1) youth indicating interest on an intake form, 2) flyers, 3) booth at Foundry, 4) participating in social groups at Foundry, and 5) peer navigators. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants. This study was approved by the University of British Columbia institutional review board, as well as through the local health authority ethics board.

Data collection and analysis occurred concurrently. Four graduate students conducted interviews lasting 1–2 hrs at a Foundry centre. The first part of the interview included demographic and mental health questions (e.g. diagnosis, medication, hospitalization, service use experiences), as well as filling out the PHQ-8 and GAD-7 in order to measure levels of anxiety and depression over the last two weeks (See Table 2). Next, open-ended questions related to the grounded theory portion of the study were asked. The last portion of the interview tapped into the ten constructs of the UTB (See Table 1), for example, “What are some benefits/drawbacks of seeking mental health services from the clinic now and for the next month?”

Table 2.

Sample characteristics (N=41)

| Socio-demographic characteristics | % (N) | Mean (SD)/Min–Max |

|---|---|---|

| Age | 20 (2.6)/15–24 | |

| Gender | ||

| Female | 46 (19) | |

| Male | 32 (13) | |

| Trans male/female | 12 (5) | |

| Non-binary | 5 (2) | |

| Two-spirit | 2 (1) | |

| Other | 2 (1) | |

| Race | ||

| White | 83 (34) | |

| Biracial | 7 (5) | |

| Filipino | 2.5 (1) | |

| Latin American | 2.5 (1) | |

| South Asian | 2.5 (1) | |

| Other | 2.5 (1) | |

| Ever been homeless | 12 (5) | |

| Born in Canada | 90 (37) | |

| Currently school | 54 (22) | |

| Currently employed | 44 (18) | |

| Mental health and service use characteristics | ||

| PHQ8 | 14 (5.2)/3–24 a | |

| GAD7 | 12.2 (4.8)/4–19 a | |

| Ever diagnosed with mental health disorder | 73 (30) | |

| Patient self-reported diagnosisb | ||

| Anxiety | 46 (19) | |

| Depression | 44 (18) | |

| ADHD | 12 (5) | |

| Bipolar | 7 (3) | |

| Autism | 5 (2) | |

| PTSD | 5 (2) | |

| Personality disorder | 5 (2) | |

| Past suicidal behaviors | 71 (29) | |

| Even been hospitalized for mental health | 32 (13) | |

| Take medication for mental health | 61 (25) | |

| Age first time seek MHSc | 15 (4.9)/3–23 | |

| Accessed MHS at Foundry at one point in time | 100 (41) | |

| Currently seeking MHS at Foundry | 85 (35) | |

| Currently seeking MHS outside Foundry | 27 (11)d |

Missing data (N=4);

some youth endorse more than one diagnosis;

Mental health services (MHS);

6 of these youth overlap with outside MHS and Foundry MHS

Content analysis methodology was used to come up with top categories containing the most salient and rich content for each UTB construct. This method is particularly useful when working with data to create and define categories describing phenomenon (30). Graduate students were also involved in the analysis of the data and received training by the PI and a senior qualitative expert, both with experience conducting qualitive research with youth experiencing mental illness. The trainings reviewed major concepts like developing categories, and consensus building (e.g. reflexivity, constant comparison). The coding team met on a regular basis. To begin, analysts independently read through the UTB data in an excel sheet to gain a general understanding of participants’ responses. Then analysts condensed and divided participants’ responses into smaller meaningful units ensuring the core meaning was retained (31). The units were then formed into condensed codes and by grouping the codes, the most salient categories emerged under each UTB construct (31). Analysts met regularly at consensus meetings to conduct constant comparison; reviewing the developed taxonomy of categories to ensure codes were related through content and context across all interviews and across analysts. A frequency count was conducted for each category. Strategies for rigour included utilizing several coders, youth feedback on the development of the interview questions and framework, coding training, weekly debriefing meetings, and audit trails (32).

A secondary analysis was conducted comparing PHQ-8 and GAD-7 scores by the UTB categories. This sample only included 37 youth, as the PHQ-8 and GAD-7 were introduced after piloting the interviews with the first four youth. Based off PHQ-8 scores, youth were split into two groups: mild to moderate (scores 3–14) & moderately severe to severely depressed (scores 15–24) (Spitzer et al., 1990). Based off GAD-7 scores, youth were split into two groups: mild to moderate (scores 4–14) & severe anxiety (scores 15–19). Next, we created two groups combining the PHQ-8 and GAD-7 groupings by symptoms severity. Group 1 comprised of fifty-seven percent (n=21) of youth that reported no symptoms, mild and moderate depression, and anxiety scores on the PhQ-8 and GAD-7. Group 2 comprised of forty-three percent (n=16) of youth that reported moderately severe, to severely depressed, or anxious scores on the PhQ-8 and GAD-7. A comparison was done between the combined final two groups to note any differences in the UTB categories. See Table 4 for results.

Table 4.

| GAD7 & PHQ8 scores combined | ||

|---|---|---|

|

|

||

| Construct and category | Mild (n=21) e % (n) |

Severe (n=16) f % (n) |

| Behavioral beliefs | ||

| Getting the help they are looking for g | 19 (4) | 81 (13) |

| Safety and security g | 29 (6) | 6 (1) |

| Services improves well-being g | 14 (3) | 56 (9) |

| Talking to someone g | 24 (5) | 56 (9) |

| Accessing services impact emotions h | 14 (3) | 44 (7) |

| Social norms | ||

| Family disapproves | 10 (2) | 50 (8) |

| Family approves | 24 (5) | 63 (10) |

| Friends approve | 67 (14) | 88 (14) |

| Formal supports approve | 10 (2) | 38 (6) |

| Emotions | ||

| Nervous, apprehensive | 10 (2) | 75 (12) |

| Hopeful | 48 (10) | 81 (13) |

| Social image | ||

| Life challenges (access services) | 14 (3) | 44 (7) |

| No supports (refuses services) | 0 (0) | 31 (5) |

| Afraid of stigma | 29 (6) | 69 (11) |

| Courageous | 0 (0) | 25 (4) |

| For anybody | 24 (5) | 50 (8) |

| Environmental barriers | ||

| Personal access barriers | 14 (3) | 44 (7) |

| Geography | 5 (1) | 31 (5) |

| Transportation | 19 (4) | 63 (10) |

| Self-efficacy/knowledge | ||

| Everyday tasks | 5 (1) | 25 (4) |

| Coping skills | 0 (0) | 38 (6) |

| Supports | 14 (3) | 44 (7) |

| Saliency | ||

| Reminder from informal support | 10 (2) | 38 (6) |

| Reminders self-initiated | 33 (7) | 56 (9) |

| Habits | ||

| Negative mind-set | 5 (1) | 44 (7) |

| Sleep habits | 14 (3) | 38 (6) |

| Split-second-decision-making | ||

| Negative experiences using services | 14 (3) | 56 (9) |

Unified Theory of Behavior,

Patient Health Questionnaire depression scale,

Generalized Anxiety Disorder Scale,

first four participants did not fill out PHQ8 and GAD7,

mild symptoms based off PHQ8 & GAD7,

severe symptoms based off PHQ8 & GAD7,

benefits,

drawbacks

Results

Forty-one young adults at Foundry participated in the study. Based off of the Patient Health Questionnaire Depression scale (PHQ-8) mean scores and the Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD-7) mean scores youth were experiencing moderate levels of anxiety and depression at the time of their interview (33). Seventy-three percent of the participants self-reported receiving a mental health diagnoses (e.g. anxiety, depression). Please see Table 2 for sample characteristics.

The results are organized around the categories for each UTB construct that were the most salient to the help-seeking experience of the participants (See Table 3 for additional quotes and see Figure 1 for a model displaying the UTB constructs among youth accessing integrated youth services).

Table 3.

Top categories and illustrative quotes

| Construct | Top categories | Quotes |

|---|---|---|

| Behavioral beliefs-Benefits | a) Receive the help they are looking for (n=19) | “learn new techniques to cope (#39)” |

| b) Talking to someone (n=16) | “the space to talk about thoughts and feelings (#12)” | |

| c) Improve well-being (n=14) | “better understanding of health and habits (#34)” | |

| d) Access to services (n=12) | “resources & immediate programs they can provide (#22)” | |

| e) Feeling of security and safety (n=8) | “knowing you have a safe space to come back to (#2)” | |

| f) Community (n=7) | “feelings of inclusiveness, understanding, solidarity (#7)” | |

| Behavioral beliefs-Drawbacks | a) Accessing services impacts emotions (n=10) | “draining emotionally (#31)” |

| b) Personal time commitment (n=8) | “it puts a damper on my work schedule (#29)” | |

| c) Lack of accessibility of services (n=7) | “not being seen that day, full capacity (#8)”, | |

| d) Quality of service or service provider (n=6) | “counsellor who doesn’t get you the first time you meet (#16)” | |

| e) External factors (n=5) | “changes in bus times (#3)” | |

| Social norms-Approve | a) Friends (n=31) | “roommate (#5)” |

| b) Primary caregivers/guardians (n=25) | “stepdad (#22)” | |

| c) Family (n=17) | “sister (#1)” | |

| d) Significant other (n=16) | “girlfriend (#18)” | |

| e) Formal supports (n=10) | “Aboriginal Advocate (#36)” | |

| Social norms-Disapprove | a) Primary caregivers/guardians (n=10) | “mom and dad [are] not very supportive (#25)” |

| b) Other informal supports (n=5) | “[a] couple of [my] male friends (#38)” | |

| Social image-Seek services | a) Looking for help (n=16) | “wandering lost soul [with] not a good connection to the world (#10)” |

| b) For anybody (n=14) | “any age, any sex, open to all people (#1)” | |

| c) Negative emotions (n=12) | “fear and anxiety as motivating factors to come to the Foundry (#11)” | |

| d) Experiencing life challenges (n=11) | “on academic probation (#20)” | |

| e) Feeling lost or confused (n=11) | “don’t understand, don’t know what’s going on (#15)” | |

| f) Young person (n=9) | “someone in high school who is about to transition [out] (#18)” | |

| g) Courageous (n=5) | “brave and strong; taking responsibility of [their] mental health (#41)” | |

| Social image-Don’t seek services | a) Negative emotions (n=17) | “nervous and don’t want to ask for help (#8)” |

| b) Lack of awareness (n=12) | “can’t recognize their own feelings (#1)” | |

| c) Negative personality traits (n=10) | “arrogant, pride gets in the way (#4)” | |

| d) Does not have supports (n=6) | “don’t have anyone to tell them about it (#20)” | |

| e) Positive personality traits (n=6) | “someone who looks like they have their life together (#29)” | |

| Emotions | a) Hopeful or positive (n=27) | “hope for the future and what I can accomplish (#11)” |

| b) Nervous or apprehensive (n=16) | “lots of anxiety (#24)” | |

| c) Relief or reassurance (n=8) | “help[ing] to ease anxiety and pressure (#9)” | |

| d) Confident (n=5) | “sense of self-assuredness (#10)” | |

| e) Neutral (n=5) | “no feeling in particular (#29)” | |

| Self-efficacy & Knowledge - Current strategies & skills | a) Time management (n=18) | “make a routine for every Thursday (#2)” |

| b) Supports (n=10) | “if you told your friend they could ask when you’re going (#18).” | |

| c) Self-awareness (n=10) | “knowing when I need to come for a check-in (#10)” | |

| d) Positive self-talk/motivation (n=8) | “positive self-talk (#33)” | |

| e) Coping (n=7) | “reframing it as something worthwhile (#32)” | |

| f) Everyday tasks (n=7) | “able to take the bus on my own (#4)” | |

| Environment-Facilitators | a) Expanded hours (n=14) | “expanded hours and days for walk-in counselling (#14)” |

| b) Transportation access (n=12) | “someone driving me here rather than bussing (#9)” | |

| c) Geographical access (n=5) | “mobility, have mobile wellness (#5)” | |

| Environment-Barriers | a) Lack of transportation (n=16) | “if buses weren’t running or couldn’t get a ride from parents (#40)” |

| b) Personal access barriers (n=12) | “school obligations (#4)” | |

| c) Foundry access barriers (n=9) | “you need referrals and getting those can be difficult (#22)” | |

| d) Geographic barriers (n=6) | “in [a] different location (#38)” | |

| e) Emotional or mental barriers (n=6) | “low mood episodes (#32)” | |

| f) Lack of support from important people (n=5) | “if my dad or someone close disapproves of the idea (#35)” | |

| Saliency | a) Technology reminders from Foundry (n=21) | “reminder from Foundry before appointment (#5)” |

| b) Self-initiated reminders (n=19) | “mood tracker on tablet (#32)” | |

| c) Reminders from informal supports (n=8) | “really rely on [my] mom for appointment and the day (#16)” | |

| Habits | a) Sleep habits (n=10) | “poor sleep schedule (#33)” |

| b) Negative mindset (n=9) | “too depressed of a mind state (#21)” | |

| c) Organizational challenges (n=9) | “trouble with time management (#1)” | |

| d) Procrastination/avoidance (n=9) | “brushing it off (#22)” | |

| Split-Second Decision-Making | a) Nothing would stop them (n=14) | “no matter what I would still get something out of coming here (#11)” |

| b) Negative experience using services (n=12) | “having a counsellor that didn’t listen and lack of connection (#9)” | |

| c) Change in access to service (n=6) | “if they required you to participate in groups (#26)” |

Figure 1.

Unified theory of behaviour among youth accessing integrated youth services

Constructs highight in blue have an emotion category

Behavioural beliefs

Participants endorsed benefits and drawbacks to seeking services at Foundry. Overall, youth responded with almost twice as many benefits than drawbacks. Benefits included categories such as: receive the help they are looking for – this included tools to manage their mental health, talking to someone, improve well-being, access to services are important, having a feeling of security and safety, and community. One participant stated, ‘[Foundry] gives you the tools to drive around the potholes so you can go around them and not slam into them (#15)”. Drawbacks included categories such as: accessing services impacts emotions, personal time commitment, lack of accessibility of services when needed, quality of service or provider, and external factors, such as the weather or the bus schedule. One participant said, “[Services are] busy when I show up and I need it (#7)”.

Social norms

Youth identified important people in their life that either approved or disapproved of them accessing services at Foundry. Participants endorsed more approval supports than those that disapproved of them seeking services. The following categories emerged for important people that supported youth: primary caregivers/guardians such as biological parents or stepparents, family, which included siblings, and grandparents, and formal supports, such as multi-professional clinicians, aboriginal advocates, and teachers. One youth indicated that, “parents [were] very instrumental in [my] recovery” and were “there when you’re at your worst (#23)”. Half of the youth reported no unsupportive people. While, a third of the participants endorsed the following categories for individuals that disapproved of them accessing services: primary caregivers/guardians, and other informal supports that included peers or family. One participant said, “parents, if they were more supportive, I would still talk to them (#11)”.

Social image

Participants provided descriptions of the types of youth that would seek services /or not seek services at Foundry. The following categories emerged for youth that seek services: looking for help, for anybody, experiencing negative emotions such as being anxious, embarrassed, experiencing life challenges such as relationship issues, feeling lost or confused, a young person such as someone in high school, and courageous. One participant explained that a youth that uses services is, “in tune with emotions and understand[s] what they’re going through and [has] enough self-worth to seek help (#12).” The following categories emerged for youth that don’t seek services: lack awareness, have negative personality traits such as “being cocky” or “superior”, do not have support, have positive personality traits such as being successful or stable, and independent. One participant said this youth is, “someone that has no help, friends, or family (#2)”.

Emotions

Participants endorsed a range of emotions when they considered seeking services at Foundry. Top emotions categories included: hopeful or positive, nervous or apprehensive, relief or reassurance, confident, and feeling neutral. Additionally, 27% of participants displayed mixed emotions, as illustrated by the following youth, “sense of relief but also anxiety towards possibly still not receiving support (#41).”

Self-Efficacy (strategies)/Knowledge (skills)

Prior to beginning data collection, the youth advisory council at a Foundry centre suggested combining these two constructs into one question: what are the skills or strategies you will use when seeking services? As a result, during analysis participant responses were combined under one category. Youth described the following strategies/skills categories when accessing services at Foundry: time management, involvement of supports, self-awareness, positive self-talk/motivation, coping, and everyday tasks such as taking the bus. Positive self-talk is demonstrated by the following youth, “pep talk with yourself, pushing yourself (#1)”,

Environmental barriers and facilitators

Participants described circumstances that would make it easier or more difficult to access services. The following categories for circumstances that would make it easier to access service included: expanded hours, such as evenings and weekends, transportation access, and geographical access. Ten percent of the youth reported they had no problem getting here. Expanded hours is illustrated by the following youth “school ends at … and it doesn’t give you enough time (#35)”. The following categories for circumstances that would make it more difficult for them to access services included: lack of transportation, personal access barriers such as a busy school schedule or work commitments, service access barriers such as referrals or financial costs, geographic barriers, emotional or mental barriers, or lack of support from important people. Emotional barriers are highlighted by the following youth, “if physical and mental health declined (#34)”.

Salience

Participants described reminders that would help them access services. These included the following categories; technology reminders from service such as texts, calls, or emails, self-initiated reminders such as using a phone calendar, planner, or post it notes, and reminders from informal supports such as important people who help manage appointments. One participant indicated they would like “email & text message check-in[s] (#17)”.

Habits

Participants described habits that may get in the way of them accessing services. These categories included: sleep habits such as oversleeping, having negative mindsets such as their mood getting in the way, organizational challenges, and procrastination/ avoidance. For example, one participant said, “if people don’t check on me and ask if I’m seeing someone I might let it slide (#9)”. Seventeen percent of participants did not report any habits.

Split-second decision-making

Youth were asked if there is anything that would change their mind about accessing services. A third of the youth in the study reported that nothing would change their mind about accessing services. A third of the youth stated that the category negative experiences at Foundry would influence future access to services (e.g. service provider interaction, heard from others about negative experience), as indicated by the following youth, “not unless I met with someone that made me feel guilty or bad (#17)”. Finally, several youths endorsed the category a change in access to service as something that would change their mind about accessing services.

UTB constructs by PHQ-8 and GAD-7 scores

Group 2 (severe symptoms) endorsed 1.5 times more categories compared to group 1 (mild to moderate symptoms). Compared to group 1, group 2 more frequently endorsed the following categories: behavioral belief benefits (e.g. benefits and drawbacks), getting the help they are looking for, social norms (e.g. disapproval and approval), emotions (e.g. negative and positive), social image, environmental barriers, self-efficacy/knowledge, saliency, habit, and split-second decision-making. See Table 4 for analysis of UTB constructs by PHQ-8 and GAD-7 scores.

Discussion

This is the first study to utilize the Unified Theory of Behavior (UTB) to understand mental health service use decision-making among youth accessing a Foundry centre. Overall, we found that youth more frequently endorsed benefits than drawbacks, and approval than disapproval messages from people in their life about accessing services. Services at Foundry may reduce the social stigma experienced when youth consider accessing services (21–23). One way Foundry does this is by engaging youth in the development of content to reflect the needs of its audience, most recently to support the needs of youth and their families during the COVID-19 pandemic (34). The following discussion will highlight the most salient constructs that emerged. First, we will expand upon the influence of emotions on service use, as it emerged as important to youth decision-making. Second, we will discuss important contributions between the intention and moderator constructs knowledge and self-efficacy. Third, we will discuss the impact of negative service use experiences on help-seeking. Finally, we will discuss the relationship between symptom severity and UTB categories.

Emotions

Emotion categories emerged beyond just the emotion construct. For example, the belief that accessing services impacts emotions; the social image of youth that seek or refuse services is that they experience negative emotions, emotions as an environmental barrier, and negative mindset as a habit. This indicated that youth are using their emotions to guide their decision-making when considering intentions to seeking services, as well as moderators that get in the way of actual services use. Similar to Munson and colleagues (21), negative emotional responses were found to be both motivators and/or inhibitors of service use. Developmentally, youth are experiencing more intense emotions during adolescence (35). Research has found that lower emotional competence in youth is linked to decreased intentions in seeking mental health services (36). That is until youth experience more moderate or severe mental health symptoms that pushes them to service use, often times initiated by family members (37). Once at services, experiencing positive emotions like relief may increase their chances of accessing services again. Psychoeducation, for both youth and caregivers, potentially delivered by peers, about how to identify and regulate emotions can be implemented in schools, and services like Foundry. Having campaigns and services that normalize emotions such as anxiety, and promote the belief that services can support emotional experiences of distress may increase intentions to seek services.

Strategies and skills

The youth and parent advisory groups’ feedback to combine skills and strategies as one question illustrated there may be an important relationship between self-efficacy and knowledge. Based on our findings there is not enough information to determine which constructs served as either skills and/or strategies. This is due to both the interrelated nature of skills and strategies, the way the question was asked, and the variability of young people’s acquired skills and level of mastery when seeking services. Strategies are conscious plans executed by a young person to help facilitate access to services (38). While, skills are automatic unconscious behaviors that are acquired over time and demonstrate a certain level of mastery (38). Typically, strategies are used to help a young person acquire a level of mastery over a behavior such as help-seeking (38). Through practice, these strategies become automatic, which may innately enhance their level of mastery and in turn form a skill. For example, a teacher may suggest a strategy of getting friends to accompany youth to services. Over time, positive service use experiences coupled with the practice of seeking services could facilitate a level of competency that allows them to recognize when they need help and how to go about receiving it. Future studies assessing for skills and strategies among youth may consider asking follow-up questions that address the duration of use, saliency, and ease of use.

Youth health and mental health supports that include counseling services, health providers offices, and schools may consider providing concrete help-seeking strategies when encouraging youth to access services as not every youth that needs help has the skills to access services. Providing strategies in the form of a task list of steps needed to seek help, and questions to ask professionals when considering accessing services can aid service use. Other strategies may include developing videos that demystify service use experience and advertisements that accurately reflect the diverse range of youth that seek services. Future research should also consider the perspectives of families and friends.

Service use experiences

Split-second decision-making in relation to the UTB framework suggests that despite previous intentions to act on a behavior, something may occur last minute that can change one’s mind about acting on that behavior. One of the top categories to the question “what would change your mind about coming to Foundry” was if youth heard about or experienced a negative service use experience at Foundry which may influence their intentions about future service use. Youth research assistants anecdotally validated the impact of previous service use experiences on decisions for future service use, which is empirically supported by research from Munson and colleagues (21). Jaccard and Levitz (16) argue that split-second decision-making occurs because it is difficult for a young person to anticipate all parameters of a future context. A youth may have the intention to access services, but a last moment decision may get in the way of that behavior. Strengthening or forming intentions before youth encounter a scenario where negative experiences could influence their decision making is one strategy to address this. For example, promoting education regarding what qualifies as a positive or negative service experience and how to bring this to the attention of trusted others, so that youth can differentiate in those moments whether their experience should disqualify continued service use exploration at a particular service centre. Services can provide guidelines on what makes a good therapist or a good service use experience, or what service use navigation should look or feel like, and what to do when things are not what they should be.

Symptom severity

This analysis revealed group differences in the UTB responses by anxiety and depression symptom severity. Overall, youth that reported severe anxiety and depression in the last two weeks endorsed more UTB categories than youth that scored mild to moderate depression and anxiety. One could speculate that youth scoring higher scores have more at stake when it comes to seeking services, and potentially have had more experiences accessing mental health services prior to Foundry which over time could build agency for some youth. Youth that are more activated in their cognitive and affective appraisals of a situation, may have increased agency in decision-making which can increase levels of engagement and satisfaction in services (20,39). Similarly, one study in the United States (22) found that youth accessing mental health services for early psychosis endorsed more UTB categories than those involved in research only. The timing and type of early interventions in mental health play a critical role, with identifying early signs of mental illness at a crucial point in time to reduce the severity of a major psychiatric diagnosis (40). These findings indicate a need to target service engagement interventions differently to youth along the continuum of symptom severity. Based off our findings, to increase engagement and investment among youth experiencing mild to moderate symptoms, services can promote the belief that services can be helpful, there are people youth can talk to, and services can improve one’s well-being. Also, to increase agency among this group, services can promote strategies and skills (e.g. coping) to support service use. At the same time, youth in the higher severity group may need services that support difficult emotions as well as stigma experiences, promote the idea of what a positive versus negative service use experience looks like, and include family psychoeducation and involvement in care.

Strengths and Limitations

First, qualitative research does not seek generalizability; as the sample was recruited from youth attending one Foundry center in Canada, caution must be used when comparing findings across populations, regions, and countries. This sample included mainly European/White perspectives; as a result, future studies should prioritize other racial and ethnically diverse young Canadians, especially those disproportionately affected by mental health such as Indigenous voices, and other ethnically diverse people (41–43). A unique contribution of this study was capturing the spectrum of gender identity within its service users when examining the relationship between constructs from the UTB and service use. We intentionally recruited youth across the gender spectrum using theoretical sampling. This Foundry centre provides gender affirming care, as well as peer support groups for transgender youth which supported our recruitment. While gender differences in UTB categories were not found in this portion of the study, they did emerge in the grounded theory portion of the study. Future research should consider capturing an array of individuals on the gender spectrum. Failing to integrate the gender spectrum into research may lead to the possibility of overlooking important determinants such as gender roles and identity, structural experiences or interpersonal relationships, which in turn may decrease the effectiveness of interventions (44).

A second limitation is this study only included perspectives of those who have accessed mental health services at Foundry. While this gives perspectives from individuals who have successfully accessed service and what factors led them to doing so, it does not provide understanding to what is still limiting others who have never accessed mental health services from coming in. Also, youth were interviewed at different points in time which may impact their views on services they had received and their decisions to seek help. Working closely with expert mental health clinicians, communities, and a diverse range of Canadian youth that are seeking services including digital mental health services, as well as those that have never sought services, can substantiate these findings. An important strength to this study was the inclusion of trained patient partners in the research process. Researchers can increase youth partner’s knowledge of research methods, and youth expertise in the subject matter strengthens the methodology and enhances the credibility of the findings (26,27). Researchers should consider investing in trainings to enhance their capacity to engage with youth (45).

Third, this research is cross-sectional and captures service users at one point in time and at different stages of a youth’s service use trajectory. Longitudinal studies, following youth over the course of their health trajectory will greatly add to this literature. Fourth, qualitative methodology is limited by investigator bias (32). To mitigate this, perspectives from multiple coders were included when interpreting results, audit trails were kept, and feedback from youth was integrated into model development.

Conclusions

This study adds to the literature by exploring help-seeking behaviours of youth accessing care at one Foundry centre. The findings reported the top categories that emerged from each construct of the UTB. In collaboration with youth research partners, important additions to the literature included the interrelated relationship between skills and strategies, the dynamic nature of decision-making, and interventions that target youth along the continuum of symptom severity. Based on these findings, interventions can explore ways to increase service use engagement among youth, including promoting a culture of tolerance, acceptance, and education to the roles that emotions may play in the service use experience.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge the youth and parents that were involved in the research process, as well as the youth that participated in this study.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest

The study received Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council Insight Development Grant (430-2018-00471); Michael Smith Foundation for Health Research scholar award (18249)

References

- 1.Fusar-Poli P. Integrated mental health services for the developmental period (0 to 25 years): A critical review of the evidence. Front Psychiatry. 2019;10(JUN):1–17. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2019.00355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jones PB. Adult mental health disorders and their age at onset. Br J Psychiatry Suppl. 2013;s54:5–10. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.112.119164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, Jin R, Merikangas KR, Walters EE. Lifetime Prevalence and Age-of-Onset Distributions of. Arch Gen Psychiatry [Internet] 2005;62(June):593–602. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.593. Available from: http://archpsyc.jamanetwork.com/article.aspx?doi= [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Khan S. Concurrent mental and substance use disorders in Canada. Heal Reports [Internet] 2017;28(8):3–8. Available from: https://movendi.ngo/wp-content/uploads/2017/08/54853-eng.pdf. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Leitch KK. Reaching for the Top: A Report by the Advisor on Healthy Children and Youth. Ottawa: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mental Health Commission of Canada. Children and Youth [Internet] 2020. Available from: https://www.mentalhealthcommission.ca/English/what-we-do/children-and-youth.

- 7.Karr CA, Larson LM. Use of theory-driven research in counseling: Investigating three counseling psychology journals from 1990 to 1999. Couns Psychol [Internet] 2005;33(3):299–326. doi: 10.1177/0011000004272257. Available from: [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jaccard J, Dodge T, Dittus P. Parent-adolescent communication about sex and birth control: a conceptual framework. New Dir Child Adolesc Dev. 2002;(97):9–42. doi: 10.1002/cd.48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Barbic SP, Leon A, Manion I, Irving S, Zivanovic R, Jenkins E, et al. Understanding the mental health and recovery needs of Canadian youth with mental health disorders: A Strategy for Patient-Oriented Research (SPOR) collaboration protocol. Int J Ment Health Syst [Internet] 2019;13(1):1–8. doi: 10.1186/s13033-019-0264-0. Available from: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fishbein M, Ajzen I. Predicting and Changing Behavior: The Reasoned Action Approach. 1st ed. New York: Psychology Press; 2010. p. 538 p. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Janz NK, Becker MH. The Health Belief Model: A Decade Later. Heal Educ Behav. 1984;11(1):1–47. doi: 10.1177/109019818401100101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rosenstock IM, Strecher VJ, Becker MH. Social Learning Theory and the Health Belief Model. Heal Educ Behav. 1988;15(2):175–83. doi: 10.1177/109019818801500203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bandura A. Principles of behavior modification. New York, NY: Holt, Rinehart and Winston; 1969. p. 677. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Triandis HC. The analysis of subjective culture. New York: Wiley; 1972. p. 383. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gross JJ. Handbook of emotion regulation. New York: Guilford Press; 2007. p. 654. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jaccard J, Levitz N. Self-Regulation in Adolescence. 2015. Parent-based interventions to reduce adolescent problem behaviors: New directions for self-regulation approaches; pp. 357–88. [Google Scholar]

- 17.MacDonald K, Fainman-Adelman N, Anderson KK, Iyer SN. Pathways to mental health services for young people: a systematic review [Internet]. Vol. 53, Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology. Springer; Berlin Heidelberg: 2018. pp. 1005–1038. Available from: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brown A, Rice SM, Rickwood DJ, Parker AG. Systematic review of barriers and facilitators to accessing and engaging with mental health care among at-risk young people. Asia-Pacific Psychiatry. 2016;8(1):3–22. doi: 10.1111/appy.12199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gulliver A, Griffiths KM, Christensen H. Perceived barriers and facilitators to mental health help-seeking in young people: a systematic review. BMC Psychiatry [Internet] 2010;113(10) doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-10-113. Available from: http://download.springer.com/static/pdf/351/art%253A10.1186%252F1471-244X-10-113.pdf?originUrl= http%3A%2F%2Flink.springer.com%2Farticle%2F10.1186%2F1471-244X-10-113&token2=exp=1460473217~acl=%2Fstatic%2Fpdf%2F351%2Fart%25253A10.1186%25252F1471-244X-10-113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ben-David S, Cole A, Spencer R, Jaccard J, Munson MR. Social context in mental health service use among young adults. J Soc Serv Res [Internet] 2017;43(1):85–99. doi: 10.1080/01488376.2016.1239595. Available from: [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Munson MR, Jaccard J, Smalling SE, Kim H, Werner JJ, Scott LD. Static, dynamic, integrated, and contextualized: A framework for understanding mental health service utilization among young adults. Soc Sci Med [Internet] 2012;75(8):1441–9. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2012.05.039. Available from: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ben-David S, Cole A, Brucato G, Girgis RR, Munson MR. Mental health service use decision-making among young adults at clinical high risk for developing psychosis. Early Interv Psychiatry. 2019;13(5):1050–5. doi: 10.1111/eip.12725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lindsey MA, Chambers K, Pohle C, Beall P, Lucksted A. Understanding the Behavioral Determinants of Mental Health Service Use by Urban, Under-Resourced Black Youth: Adolescent and Caregiver Perspectives. J Child Fam Stud. 2013;22(1):107–21. doi: 10.1007/s10826-012-9668-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hetrick SE, Bailey AP, Smith KE, Malla A, Mathias S, Singh SP, et al. Integrated (one-stop shop) youth health care: best available evidence and future directions. Med J Aust. 2017;207(10):S5–18. doi: 10.5694/mja17.00694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Canadian Institutes of Health Research. Canada’s strategy for patient-oriented research—patient engagement framework [Internet] 2014. Available from: https://cihr-irsc.gc.ca/e/documents/spor_framework-en.pdf.

- 26.Bell E. Young Persons in Research: A Call for the Engagement of Youth in Mental Health Research. Am J Bioeth. 2015;15(11):28–30. doi: 10.1080/15265161.2015.1088977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Checkoway B, Richards-Schuster K. Evaluation research. MEDSURG Nurs. 2003;24(1):21–33. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tongco MDC. Purposive sampling as a tool for informant selection. Ethnobotany research and applications. Ethnobot Res Appl [Internet] 2007;5:147–58. Available from: www.ethnobotanyjournal.org/vol5/i1547-3465-05-147.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ellard-Gray A, Jeffrey NK, Choubak M, Crann SE. Finding the Hidden Participant: Solutions for Recruiting Hidden, Hard-to-Reach, and Vulnerable Populations. Int J Qual Methods [Internet] 2015;14(5) doi: 10.1177/1609406915621420. 160940691562142. Available from: [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cavanagh S. Content analysis: concepts, methods and applications. Nurse Res. 1997;4(3):5–16. doi: 10.7748/nr.4.3.5.s2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Erlingsson C, Brysiewicz P. A hands-on guide to doing content analysis. J Emerg Med. 2017;7(3):93–9. doi: 10.1016/j.afjem.2017.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Padgett DK. Qualitative methods in social work research. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JBW, Löwe B. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: The GAD-7. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166(10):1092–7. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.10.1092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zenone MA, Cianfrone M, Sharma R, Majid S, Rakhra J, Cruz K, Cosales S, Sekhon M, Matias S, Tugwell A, Barbic S. Supporting youth 12–24 during the COVID-19 pandemic: how Foundry is mobilizing to provide information, resources and hope across the province of British Columbia. Glob Health Promot. 2021;28(1):51–9. doi: 10.1177/1757975920984196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rosenblum GD, Lewis M. Emotional development in adolescence. In: Adams GR, Berzonsky MD, editors. Blackwell Handbook of Adolescence. Malden: Blackwell Publishing; 2003. pp. 269–89. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ciarrochi J, Wilson CJ, Deane FP, Rickwood D. Do difficulties with emotions inhibit help-seeking in adolescence? The role of age and emotional competence in predicting help-seeking intentions. Couns Psychol Q [Internet] 2003;16(2):103–20. doi: 10.1080/0951507031000152632. Available from: [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Corcoran C, Davidson L, Sills-Shahar R, Nickou C, Malaspina D, Miller T, et al. A qualitative research study of the evolution of symptoms in individuals identified as prodromal to psychosis. Psychiatr Q. 2003;74(4):313–32. doi: 10.1023/a:1026083309607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Afflerbach P, Pearson PD, Paris SG. Clarifying Differences Between Reading Skills and Reading Strategies. Read Teach. 2008;61(5):364–73. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Munson MR, Jaccard J. Mental health service use among young adults: a communication framework for program development. Adm Policy Ment Heal Ment Heal Serv Res. 2018;45(1):62–80. doi: 10.1007/s10488-016-0765-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mei C, Fitzsimons J, Allen N, Alvarez-Jimenez M, Amminger GP, Browne V, et al. Global research priorities for youth mental health. Early Interv Psychiatry. 2020;14(1):3–13. doi: 10.1111/eip.12878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Atkinson D. Considerations for indigenous child and youth population mental health promotion in Canada [Internet] Canada: 2017. Available from: https://nccph.ca/images/uploads/general/07_Indigenous_MentalHealth_NCCPH_2017_EN.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chiu M, Amartey A, Wang X, Kurdyak P. Ethnic Differences in Mental Health Status and Service Utilization: A Population-Based Study in Ontario, Canada. Can J Psychiatry. 2018;63(7):481–91. doi: 10.1177/0706743717741061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fante-Coleman T, Jackson-Best F. Barriers and Facilitators to Accessing Mental Healthcare in Canada for Black Youth: A Scoping Review. Adolesc Res Rev [Internet] 2020;5(2):115–36. doi: 10.1007/s40894-020-00133-2. Available from: [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tannenbaum C, Greaves L, Graham ID. Why sex and gender matter in implementation research Economic, social, and ethical factors affecting the implementation of research. BMC Med Res Methodol [Internet] 2016;16(1):1–9. doi: 10.1186/s12874-016-0247-7. Available from: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hawke LD, Darnay K, Relihan J, Khaleghi-Moghaddam M, Barbic S, Lachance L, et al. Enhancing researcher capacity to engage youth in research: Researchers’ engagement experiences, barriers and capacity development priorities. Heal Expect. 2020;23(3):584–92. doi: 10.1111/hex.13032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]