Abstract

Variation in parental beliefs about Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) may impact subsequent service use profiles. This study aimed to examine (1) variation in beliefs about ASD among English language proficient White (EP-W) mothers, English language proficient Latino (EPL) mothers, and limited English language proficient Latino (LEP-L) mothers of children with ASD; (2) variation in beliefs about ASD in the context of the child’s ASD severity, among EP White mothers, EP Latino others, and LEP Latino mothers; and (3) potential links between maternal beliefs about ASD and children’s current ASD treatment. This multi-site study included 305 English or Spanish-speaking parents of children with ASD, ages 2–10 years, who completed a survey about their beliefs about their child’s ASD, their child’s ASD severity, and treatments used by their children. Results showed that mothers in the EP-W, EP-L, and LEP-L groups differed in their beliefs about viewing ASD as a mystery. Only maternal views of ASD severity in the EP-W group were linked to their beliefs about ASD. Finally, maternal beliefs about ASD having major consequences on their child’s life, and ASD being a mystery were strongly associated with a child’s use of ASD intervention services. These findings provide new knowledge of how maternal beliefs about ASD vary in linguistically diverse groups, how a child’s ASD severity may influence such beliefs, and how maternal beliefs correlate with the amount of therapy children with ASD receive. Future research should address how these beliefs or views are formed, what factors influence them, or whether they are malleable. Understanding parents’ beliefs or views of having a child with ASD can potentially help us increase use of ASD intervention services in families of children with ASD.

Keywords: Autism, Maternal beliefs about ASD, Children, ASD severity, Intervention services use

Previous research has reported some variability in parental beliefs about their child’s Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD; Dale, Jahoda, & Knott, 2006; Silverman & Brosco, 2007). These parental beliefs about ASD might influence ASD-related treatment selection (Mandell & Novak, 2005). Understanding how variation in parental beliefs about ASD may be influenced by child and family characteristics could ultimately help increase optimal service utilization in children with ASD, as well as reduce racial, ethnic, and language-based disparities in care for children with ASD. Thus, this study sought to examine (1) variation in beliefs about ASD among English language proficient White (EP-W) mothers, English language proficient Latino (EP-L) mothers, and limited English language proficient Latino (LEP-L) mothers of children with ASD; (2) variation in beliefs about ASD in the context of the child’s ASD severity, among EP-W mothers, EP-L others, and LEP-L mothers; and (3) potential links between maternal beliefs about ASD and children’s current ASD treatment.

1. Parental beliefs about ASD

Super and Harkness (1986) and Harkness and Super (1994) advanced the developmental framework that posit that culture, which includes parents’ beliefs about parenting practices and child development, influences the developing child. This view has been supported by research that reports parental beliefs about child’s disability, causes of it, and treatment services to address that disability (Danseco, 1997). Previous research indicates that parents of children with ASD vary in their beliefs about their child’s ASD in terms of causes, prognosis, and general ASD knowledge (Dale et al., 2006; Silverman & Brosco, 2007). Although limited, recent research also suggests that parents of different ethnic and cultural backgrounds may have different beliefs about their child’s conditions. For instance, in one study, English-speaking parents of children with ASD were asked about beliefs regarding their child’s “learning or developmental conditions” (Zuckerman, Lindly, Sinche, & Nicolaidis, 2015). In that study, parents, who had lower income, lower educational level, or were racial/ethnic minorities, were more likely to believe child’s condition was a mystery, and less likely to believe their child’s condition was lifelong and it could be prevented or decreased with treatment.

Overall, however, an understanding of the effects of language and ethnicity on parental beliefs about ASD specifically is still lacking. Such information is important because it will enable understanding of what meaning or views parents have about their experience of having a child with ASD (Woodgate, Ateah, & Secco, 2008).

2. Utilization of ASD related services

Most children with ASD do not receive the recommended amount of intervention services (National Research Council, NRC, 2001; Odom, Boyd, Hall, & Hume, 2010; Pringle, Colpe, Blumberg, Avila, & Kogan, 2012; Siller, Reyes, Hotez, Hutman, & Sigman, 2014). Children from minority groups tend to receive even fewer intervention services than their White peers (Levy & Hyman, 2005; Magaña, Lopez, Aguinaga, & Morton, 2013; Magaña, Parish, Rose, Timberlake, & Swaine, 2012; Parish, Magaña, Rose, Timberlake, & Swaine, 2012; Stevens et al., 2009; Thomas, Ellis, McLaurin, Daniels, & Morrissey, 2007). For example, compared to White children, Latino children received fewer specialty services and had more unmet intervention needs (Leigh, Grosse, Cassady, Melnikow, & Hertz-Picciotto, 2016; Liptak et al., 2008; Magaña et al., 2013; Magaña et al., 2013; Thomas et al., 2007). Specifically, Latino children often receive fewer speech and language and occupation therapy services than White children (Irvin, McBee, Boyd, Hume, & Odom 2012).

In general, Latino children tend to receive worse health care access, utilization, and quality of services than their White peers (Magaña et al., 2012; Parish et al., 2012). The reasons for these disparities are likely complex and multifactorial, but utilization of ASD related intervention services might be, in part, influenced by family characteristics, such as race/ethnicity, SES, parent income/education, and parental beliefs (Mandell & Novak, 2005; Siller et al., 2014).

3. Severity in ASD

Some research has been reported on parental views about the severity of their child’s ASD. Parents who perceived their children’s ASD as more severe reported less progress in adaptive skills and cognitive abilities (Reed & Osborne, 2012; Zachor & Itzchak, 2010), and increased behavioral problems (Jang, Dixon, Tarbox, & Granpeesheh, 2011; Jang & Matson, 2015; Matson, Wilkins, & Macken, 2008). Also, when parents viewed their children’s ASD as more severe, they reported increased adjustment difficulties in siblings (Hastings, 2003; Meyer, Ingersoll, and Zambrick, 2011), and decreased parental satisfaction and maternal well-being (Hock & Ahmedani, 2012; Hoffman et al., 2008; Lyons, Leon, Phelps, & Dunleavy, 2010; Meirsschaut, Roeyers, & Warreyn, 2010; Moh & Magiati, 2012).

4. Parental beliefs, utilization of ASD related services, and ASD severity

Parental beliefs about ASD might be linked to parental decisions to use intervention services for their children (Bernheimer & Weisner, 2007; Mandell & Novak, 2005; Zuckerman et al., 2015). In two French studies, participation in parent training programs was found to be associated with the beliefs that ASD symptoms are permanent and that ASD has a genetic component (Al Anbar, Dardennes, Prado-Netto, Kaye, & Contejean, 2010); and parents who believed that early traumatic experiences caused ASD were less likely to use behavior therapy and PECS (Dardennes et al., 2011). In another study with English-speaking parents of children with ASD who were low functioning, parenting self-efficacy as well as parental understanding of their child development predicted the rate of change in the intensity (number of hours per week) of children’s individual intervention services over time, such that greater understanding and parenting self-efficacy were associated with increased intervention services intensity among children with ASD (Siller et al., 2014). In the same study, parental knowledge about their child’s development was found to be associated with higher intervention services use. To date, only one study has included children with from Latino families. In that study, a positive association was reported between knowledge of ASD resources and number of services received (Magaña et al., 2013). Together, previous research suggests that parental beliefs might be linked to the type and amount of intervention services used by children with ASD (Blacher, Cohen, & Azad, 2014; Zuckerman et al., 2014). However, this association needs to be further examined in families from linguistically diverse backgrounds.

Finally, some attention has been given to parental views about the severity of their child’s ASD in the context of family characteristics and intervention services. For instance, maternal views about ASD severity may be influenced by whether their child is receiving intervention services (Brachlow, Ness, McPheeters, McPheeters, & Gurney, 2007; Hertz-Picciotto & Delwiche, 2009; Mandell, Novak, & Zubritsky, 2005). In one study, parental views that their child’s ASD is severe and the beliefs that ASD course is unpredictable were found to be associated with increased use of educational methods and pharmaceutical treatments, respectively (Al Anbar et al., 2010). In another study, 28% of parents of children with ASD from non-English primary language households were more likely to believe that their child had “severe ASD” compared to 13% of English speaking households (Lin & Stella, 2015). Overall, given previous research on ASD severity and child and family characteristics, it is possible that parental beliefs about ASD might also vary in the context of their child’s ASD severity.

5. Current study

A significant limitation of previous research is that the link between maternal beliefs about ASD and use of intervention services has not been examined in linguistically diverse samples, which may vary more in their beliefs and be especially likely to face difficulties accessing needed intervention services (Harstad, Huntington, Bacic, & Barbaresi, 2013; Magaña et al., 2012). Current knowledge about maternal beliefs has been predominantly obtained from studies of participants who were middle class White or Latino with English language proficiency (e.g., Kuhn & Carter, 2006; Zuckerman et al., 2015; Zuckerman, Lindly, & Sinche, 2016). Also, some studies did not assess maternal beliefs about ASD specifically, but rather more general beliefs about children with learning and developmental problems (e.g., Zuckerman et al., 2015). In addition, most studies did not confirm children’s parent-reported ASD diagnosis (e.g., Al Anbar et al., 2010; Zuckerman et al., 2015; Zuckerman et al., 2016). Finally, whether beliefs about ASD vary in the context of ASD severity or whether those beliefs are linked to use of ASD intervention services remains unexplored in linguistically diverse families.

To better understand maternal beliefs about ASD, in the context of ASD severity and use of intervention services, this study included English language proficient White (EP-W) mothers, English language proficient Latino (EP-L) mothers, and limited English language proficient Latino (LEP-L) mothers who had one child or more diagnosed with ASD. The following questions were addressed by the current study:

Do maternal beliefs about their child’s ASD differ between the EP-W, EP-L, and LEP-L groups?

Do maternal beliefs about their child’s ASD differ in the context of maternal views of their child’s ASD severity in the EP-W, EP-L, and LEP-L groups?

Are maternal beliefs about ASD associated with child’s use of ASD intervention services in the EP-W, EP-L, and LEP-L groups?

6. Methods

6.1. Participants and procedures

In 2014–2015, we conducted a survey of parents of Latino and non-Latino white children with a confirmed ASD diagnosis at autism multidisciplinary clinics in Los Angeles, California; Denver, Colorado; or Portland, Oregon. Because each site had more eligible patients than were needed based on initial sample size calculations, a random sample of eligible medical records was selected at each site.

6.2. Study eligibility

To be selected for the study sample, children had to have received an ASD diagnosis at a multidisciplinary ASD clinic in the prior five years and be between 2 and 10 years of age at the time of the survey. A manual chart audit was conducted to confirm race/ ethnicity, the administration of the Autism Diagnostic Observational Schedule (ADOS), and use of Diagnostic and Statistical Manual- IV-TR or Diagnostic and Statistical Manual-5 criteria. The sample excluded children with other major comorbid developmental conditions (e.g., Down syndrome), children whose families spoke neither Spanish nor English, or parents who were younger than 18 years of age. Each institution’s Institutional Review Board independently approved the study protocol. A $5.00 participant incentive was provided in the initial mailing.

All selected families (n = 489) were mailed a self-administered survey in English or Spanish. Families who did not return a written survey were offered telephone survey administration in their preferred language by a bilingual, bicultural telephone interviewer. Of the 489 participants contacted, 376 returned or completed the questionnaire. Of the 376 respondents, 361 provided responses to all items about beliefs regarding their child’s ASD and its severity, and 360 reported information about current service use, leading to a composite response rate of 73.6%.

Twenty-three families in the EP-W group, ten families in the EP-L group, and three families in the LEP-L group were subsequently excluded from this analysis because the responders were not mothers. Fourteen LEP-L mothers were excluded because they completed the questionnaire in English making responses difficult to interpret. Five families did not report language proficiency status. Thus, the final sample for this study was 305 mothers (EP-W: n = 145; EP-L: n = 82; and LEP-L: n = 78).

6.3. Measures

The survey instrument consisted of 34 structured items assessing potential barriers to ASD diagnosis, children’s current intervention services, beliefs about ASD, and demographic information. For this study, we included demographic information (i.e., maternal age, years of education, marital status, and nativity; child age and gender), maternal beliefs about ASD, maternal perception of ASD severity, and maternal report of ASD intervention services. Mothers also reported their age, years of education, marital status, English language proficiency, and nativity.

6.3.1. Maternal beliefs about ASD

A number of items from the Illness-Perception Questionnaire-Revised for Autism (IPQ-RA) were used to gauge information about maternal beliefs about their child’s ASD (Al Anbar et al., 2010), which is available in its original form at www.uib.no/ipq/(Moss-Morris et al., 2002). Maternal beliefs were assessed using the following IPQ-RA statements: (1) My child’s condition is likely to be lifelong rather than temporary; (2) My child’s ASD has major consequences on his/her life; (3) My child’s condition is a mystery to me; (4) I have the power to influence my child’s condition; (5) The problems related to my child’s condition can be prevented or decreased with treatment. Each statement was rated on a 4-point Likert scale (Definitely Disagree, Disagree, Agree, Definitely Agree). We used the term “belief” rather than “knowledge” because “belief” indicates a viewpoint and “knowledge” indicates facts, in other words, parents can have knowledge about ASD that, in turn, shapes their beliefs about ASD (Danseco, 1997). These variables were treated as continuous. We examined these five items individually, because they may reflect different constructs and have not, together, been previously validated as a scale.

6.3.2. Maternal perception of ASD severity

Mothers were also asked, “How severe is your child’s ASD?” They responded to this question as mild, moderate, or severe. This item was adapted from the 2009/2010 National Survey of Children with Special Heath Care Needs (National Center for Health Statistics, 2015). Because most mothers in the English and Spanish speaking groups reported that their child’s ASD was either mild (49.03%) or moderate (40.47%), severe responses (10.50%) were few and those families were grouped with the moderate group.

6.3.3. Current treatment service use

To obtain information about intervention services, survey items were adapted from the 2011 Survey Pathways to Diagnosis and Services (Center for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics, State and Local Area Integrated Telephone Survey, 2011). Mothers were asked if their child were receiving any ASD intervention services on a regular basis at school or outside of school. Then, they reported the total hours of therapy service their child received per week at home or school (none, < 1 h, 1–4 h, 5–10 h, 11–20 h, > 20 h per week).

6.3.4. Assessment of english proficiency

Questions about maternal English proficiency were asked based on federal guidelines, using a single item from the U.S. Census American Community Survey (US Census Bureau, 2014): “How well do you speak English?” Two mutually exclusive groups were identified: if respondents indicated “Very well” in response to this item, they were categorized as ELP, or if participants indicated “Well,” “Not well,” or “Not at all,” they were categorized as LEP. U.S. Census data suggests that this definition of English proficiency has strong convergent validity with more rigorous English proficiency measures (Vickstrom, Shin, Collazo, & Bauman, 2015).

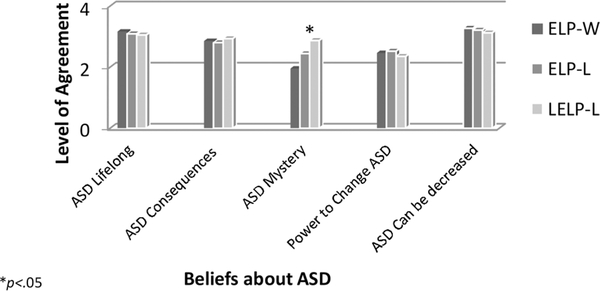

6.4. Statistical analyses

Descriptive statistics and chi-square or one-way ANOVA tests were first computed to compare child and maternal characteristics between the EP-W, EP-L, and LEP-L groups (Table 1). To address the first research question, differences in each maternal belief between the EP-W, EP-L, and LEP-L groups were examined using the Kruskal-Wallis H test (Fig. 1). To address the second research question, variation in each maternal belief according to perceived ASD severity (mild versus moderate/severe) and ethnicity/lan- guage (EP-W, EP-L, LEP-L) was examined using multiple linear regression, which included a cross-product interaction term (ASD severity * ethnicity/language; Table 2). A similar approach was used to address the third research question: a series of multiple linear regression model were fit to determine the effect modification according to ethnicity/language using cross product interaction terms (e.g., maternal belief * ethnicity/language; Table 3). Due to significant differences between the ethnicity and language groups in maternal age and education years, we controlled for both variables in all multiple regression models. Additionally, after finding variation in some beliefs by site, we adjusted for site in the corresponding regression models. All analyses were performed with the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences 15.

Table 1.

Child and Maternal Characteristics.

| Child | EP-W Group (n = 145) | EP-L Group (n = 82) | LEP-L Group (n = 78) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age: M (SD) | 5.92 years (2.01) | 5.83 years (1.90) | 5.81 years (2.07) |

| Sex | |||

| Male | n = 114 (78.60%) | n = 68 (82.90%) | n = 71 (91.00%) |

| Female | n = 29 (20.00%%) | n = 13 (15.90%) | n = 6 (7.70.%) |

| ASD Severity | |||

| Mild | 75 (51.70%) | 36 (43.90%) | 35 (44.90%) |

| Moderate/Severe | 67 (46.2%) | 45 (54.90%) | 41 (52.60%) |

| Mother | |||

| Age: M (SD)** | 36.43 years (6.34) | 33.76 years (6.11) | 36.36 years (5.10) |

| Education: M (SD)** | 15.02 years (3.59) | 14.52 years (3.00) | 10.25 years (3.25) |

| Marital status | |||

| Married | 116 (80.00%) | 61 (74.40%) | 64 (82.10%) |

| Single | 13 (9.00%) | 9 (11.00%) | 6 (7.70%) |

| Other + | 16 (11.00%) | 12 (14.60%) | 7 (9.00%) |

p < 0.01 (One-way ANOVA).

Notes. ELP-W = English Language Proficiency-White; ELP-L = English Language Proficiency-Latino; LEP-l-Limited English Language Proficiency-Latino.

”Other” marital status included: divorced, separated, and widowed.

Fig. 1.

Mean Scores for Mothers’ Beliefs about their Child’s ASD in the EP-W, EP-L, and LLP-L Groups.

Table 2.

Multiple Linear Regression Model Results: Associations between ASD Severity and Maternal Beliefs.

| ASD is lifelong (n = 302) |

ASD has consequences (n = 299) |

ASD is a mystery (n = 303) |

Have the power to change ASD (n = 301) |

ASD can be treated (n = 303) |

||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | SE | p-value | B | SE | p-value | B | SE | p-value | B | SE | p-value | B | SE | p-value | ||

| Intercept | 2.31 | 0.35 | < .001 | 1.47 | 0.33 | < .001 | 2.08 | 0.39 | < .001 | 2.69 | 0.37 | < .001 | 2.67 | 0.29 | < .001 | |

| Ethnicity & Language | ||||||||||||||||

| LEP-L | −.13 | 0.18 | 0.46 | 0.28 | 0.18 | 0.11 | 0.74 | 0.20 | < .001 | −.03 | 0.20 | 0.869 | 0.07 | 0.15 | 0.66 | |

| EP-L | −.20 | 0.16 | 0.21 | 0.23 | 0.16 | 0.14 | 0.55 | 0.18 | 0.002 | −.04 | 0.18 | 0.801 | 0.11 | 0.13 | 0.42 | |

| ASD Severity | ||||||||||||||||

| Moderate or Severe | 0.49 | 0.14 | < .001 | 0.65 | 0.14 | < .001 | 0.10 | 0.15 | 0.52 | −.39 | 0.15 | 0.010 | −.04 | 0.12 | 0.71 | |

| LEP-L*Moderate or Severe | −.14 | 0.22 | 0.52 | −0.29 | 0.22 | 0.19 | 0.01 | 0.24 | 0.98 | 0.30 | 0.24 | 0.228 | −.03 | 0.18 | 0.87 | |

| EP-L*Moderate or Severe | 0.07 | 0.22 | 0.76 | −0.50 | 0.22 | 0.02 | −.12 | 0.24 | 0.63 | 0.21 | 0.25 | 0.399 | −.32 | 0.18 | 0.08 | |

| Maternal Education, years | −.01 | 0.01 | 0.43 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.50 | −.03 | 0.02 | 0.11 | 0.04 | 0.02 | 0.016 | 0.05 | 0.01 | < .001 | |

| Maternal Age, years | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.01 | 0.001 | 0.003 | 0.01 | 0.69 | −.02 | 0.01 | 0.055 | −.003 | 0.01 | 0.61 | |

| Site | ||||||||||||||||

| Los Angeles, CA | 0.32 | 0.11 | 0.006 | – | – | – | 0.05 | 0.13 | 0.68 | – | – | – | 0.20 | 0.09 | 0.03 | |

| Portland, OR | 0.23 | 0.12 | 0.048 | – | – | – | 0.17 | 0.13 | 0.17 | – | – | – | 0.06 | 0.10 | 0.54 | |

| Likelihood Ratio Chi-Square (df) | 40.965 (9) | – | < .001 | 39.540 (7) | – | < .001 | 56.882 (9) | – | < .001 | 18.287 (7) | – | 0.011 | 39.547 (9) | – | < .001 | |

Note. The referent category is not shown for each categorical variable.

–Indicates that the statistic was not computed for the model. Site was only included in the models for beliefs that it had a statistically significant association with according to bivariate analysis results.

Table 3.

Multiple Linear Regression Model Results: Associations between Maternal Beliefs and ASD Treatment Hours.

| Model 1: ASD Tx Hours (n = 296) |

Model 2: ASD Tx Hours (n = 294) |

Model 3: ASD Tx Hours (n = 297) |

Model 4: ASD Tx Hours (n = 295) |

Model 5: ASD Tx Hours (n = 297) |

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | SE | p-value | B | SE | p-value | B | SE | p-value | B | SE | p-value | B | SE | p-value | |

| Intercept | 2.93 | 0.66 | < .001 | 2.45 | 0.62 | < .001 | 2.52 | 0.60 | < .001 | 3.20 | 0.60 | < .001 | 2.78 | 0.74 | < .001 |

| ASD Severity | |||||||||||||||

| Moderate or Severe | 0.39 | 15 | 0.009 | 0.27 | 0.15 | 0.080 | 0.36 | 0.14 | 0.013 | 0.38 | 0.15 | 0.009 | 0.40 | 0.15 | 0.006 |

| Maternal Education, years | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.47 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.223 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.54 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.156 | 0.005 | 0.02 | 0.84 |

| Maternal Age, years | −.01 | 0.01 | 0.49 | −.01 | 0.01 | 0.629 | −.01 | 0.01 | 0.70 | −.01 | 0.01 | 0.949 | −.005 | 0.01 | 0.68 |

| Ethnicity and Language | |||||||||||||||

| LEP-L | 0.33 | 0.72 | 0.65 | 0.39 | 0.68 | 0.57 | −.14 | 0.51 | 0.79 | −1.09 | 0.51 | 0.03 | −.23 | 0.82 | 0.78 |

| EP-L | 0.43 | 0.64 | 0.50 | 0.59 | 0.59 | 0.32 | 0.61 | 0.47 | 0.20 | −.68 | 0.51 | 0.18 | 0.23 | 0.86 | 0.79 |

| Site | |||||||||||||||

| Los Angeles, California | 0.60 | 0.18 | 0.001 | – | – | – | 0.57 | 0.18 | 0.001 | – | – | – | 0.55 | 0.18 | 0.002 |

| Portland, Oregon | 0.11 | 0.18 | 0.55 | – | – | – | 0.08 | 0.18 | 0.65 | – | – | – | 0.10 | 0.18 | 0.59 |

| Maternal ASD Beliefs and Interaction Terms | |||||||||||||||

| ASD is lifelong | 0.01 | 0.14 | 0.49 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| LEP-L*ASD Lifelong | −.22 | 0.21 | 0.31 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| EP_L*ASD Lifelong | −.15 | 0.20 | 0.47 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| ASD has consequences | – | – | – | 0.29 | 0.14 | 0.036 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| LEP-L * ASD consequences | – | – | – | −0.24 | 0.22 | 0.29 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| EP-L * ASD consequences | – | – | – | −0.18 | 0.20 | 0.37 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| ASD is a mystery | – | – | – | – | – | – | 0.34 | 0.14 | 0.012 | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| LEP-L * ASD mystery | – | – | – | – | – | – | −0.18 | 0.19 | 0.34 | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| EP-L * ASD mystery | – | – | – | – | – | – | −0.32 | 0.20 | 0.10 | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Have power to change ASD | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | −.10 | 0.13 | 0.43 | – | – | – |

| LEP-L*Power to change ASD | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 0.34 | 0.20 | 0.08 | – | – | – |

| EP_L* Power to change ASD | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 0.32 | 0.19 | 0.09 | – | – | – |

| ASD can be treated | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 0.16 | 0.18 | 0.38 |

| LEP-L*ASD can be treated | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | −.05 | 0.25 | 0.86 |

| EP_L* ASD can be treated | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | −.07 | 0.26 | 0.77 |

| Likelihood Ratio Chi-Square (df) | 26.988 (10) | – | 0.003 | 17.933 (8) | – | 0.022 | 32.875 (10) | – | < .001 | 21.121 (8) | – | 0.007 | 26.706 (10) | – | 0.003 |

Note. The referent category is not shown for each categorical variable.

–Indicates that the statistic was not computed for the model. Site was only included in the models for beliefs that it had a statistically significant association with according to bivariate analysis results.

7. Results

7.1. Participant characteristics

Descriptive statistics of demographics pertaining to child and mother characteristics are reported in Table 1. An overall main effect was found between the EP-W, EP-L, LEP-L groups for maternal age, F(2301) = 5.83, p = .003; and maternal education, F (2296) = 53.66, p < .001. That is, mothers in the EP-L group (M = 33.76) were younger than mother in the EP-W group (M = 36.43) and in the LEP-L (M = 36.36). Regarding education, mothers in the EP-W (M = 15.02 years) and the EP-L (M = 14.52 years) groups reported having more years of education than mothers in the LEP-L group (M = 10.25 years). In all groups, a majority of the mothers were married. No differences in child’s ASD severity were found between EP-W, EP-L, LEP-L groups.

7.2. Differences in beliefs about ASD in the EP-W, EP-L, and LEP-L groups

Kruskal-Wallis H test results showed a significant difference in the maternal belief that ASD is a mystery between EP-W, EP-L, and LEP-L groups, χ2(2) = 47.29, p < .001. That is, mothers in the LEP-L group more strongly endorsed that their child’s ASD was a mystery than the EP-L and EP-W groups. No other significant differences in maternal beliefs about ASD were found between EP-W, EP-L and LEP-L groups.

7.3. Associations of maternal beliefs about ASD with ASD severity and ethnicity/language

As shown in Table 2, multiple regression model results revealed that maternal views of the child’s ASD as moderate or severe (versus mild) were associated with greater endorsement of beliefs about the child’s ASD being lifelong (versus temporary) or ASD having major consequences for the child’s life. By contrast, results demonstrated maternal views of the child’s ASD as moderate or severe were associated with significantly less endorsement of the belief about the power to change ASD. Additionally, results showed that ethnicity and language—specifically being EP-L or LEP-L (versus EP-W)—was significantly associated with greater agreement that ASD is a mystery. Ethnicity and language was also found to significantly modify the association of ASD severity with the belief that ASD has major consequences for the child’s life. More specifically, mothers who viewed their child’s ASD as moderate or severe endorsed this belief to a lesser extent if they were EP-L versus EP-W. Years of maternal education were also positively and significantly associated with the belief about having the power to change ASD or that treatment can reduce problems due to the child’s condition, based on multivariable regression model results.

7.4. Associations of maternal beliefs and ethnicity/language with weekly ASD treatment hours

Multiple regression model results showed that the maternal beliefs ASD has consequences and that ASD is a mystery each retained a positive and statistically significant association with weekly ASD treatment hours after controlling for maternal age and education years, ASD severity, and language/ethnicity. In the multiple regression model examining associations of the maternal belief about having the power to change ASD and weekly ASD treatment hours, LEP-L was significantly and negatively associated with weekly ASD treatment hours. However, ethnicity/language was not found to significantly modify this association. Across the models, the maternal view of the child’s ASD being moderate or severe ASD was associated with more weekly ASD treatment hours.

8. Discussion

This study addressed three main topics: differences in maternal beliefs about ASD in EP-W, EP-L, and LEP-L groups, differences in maternal beliefs about ASD in the context of maternal views of their child’s ASD severity, and potential associations between maternal beliefs about ASD, intervention services used by children with ASD, and parent views of ASD severity. Study findings provide new knowledge of how maternal beliefs about ASD may vary in linguistically diverse groups, as well as how a child’s ASD severity may influence such beliefs and the relationship between maternal beliefs and amount of therapy children with ASD receive. These findings increase our understanding about different parents’ views and experiences of having a child with ASD in diverse families.

8.1. Beliefs about ASD in the EP-W, EP-L, and LEP-L groups

Findings from this study suggest that mothers in the LEP-L group were more likely to report that their child’s ASD was mystery to them than mothers in the EP-W and EP-L groups. One interpretation of this finding could be that mothers in the LEP-L group felt that their child’s ASD was a mystery because they understood/comprehended less about their child’s ASD or had more limited knowledge about ASD than did mothers in the EP-W and EP-L groups. This might be the case if parents equated mystery with understanding or comprehending ASD. Since mothers in the LEP-L group reported lower educational attainment than mothers in the other two groups, they may have had comparatively less access to resources about ASD (e.g., written or electronic information in English, English speaking professionals).

These results are similar to previous findings indicating that ethnically diverse families are more likely to report that their child’s learning or developmental condition is a mystery to them (Zuckerman et al., 2015). These results are also consistent with previous research in non-ASD populations that suggest parents from ethnic/minority groups might have different beliefs (e.g., timing for social development milestones) about typical child development than non-minority parents (Bornstein & Cote, 2004; Pachter & Dworkin, 1997; Ratto, Reznick, & Turner-Brown, 2015).

Study findings also indicate that mothers in the EP-W, EP-L and LEP-L groups have many similar beliefs about ASD, including believing that ASD is a lifelong condition, has major consequences for their child, and they have the power to influence their child’s ASD. These findings are inconsistent with earlier research that parents from diverse backgrounds differed in their beliefs about their power to influence their child’s learning or developmental condition and the stability of their child’s condition (Zuckerman et al., 2015). However, the Zuckerman study did not specifically assess beliefs “about ASD,” but rather about a child’s “learning and developmental problems,” and parents may have different beliefs about that condition as well. Additionally, that study did not assess the role of English proficiency specifically, and sampling design differences may have also contributed to this difference.

8.2. Beliefs about ASD, ASD severity, and ethnicity/language

Results from our study suggest that maternal views about ASD severity may be linked to beliefs regarding ASD. Specifically, our study showed that maternal views of a child’s ASD being moderate or severe were associated with the maternal belief that ASD is lifelong versus temporary, as well as the maternal belief that ASD had major consequences for the child’s life. Conversely, maternal views of a child’s ASD being moderate or severe were associated with reduced maternal beliefs about having the power to change their child’s ASD. Ethnicity and language were further found to modify the association between maternal views of ASD severity and the belief that ASD has consequences: EP-W mothers who viewed their child’s ASD as moderate or severe more strongly endorsed the belief that ASD has consequences than did EP-L mothers of children with similar ASD severity ratings. Together, these findings support the notion that maternal views of ASD severity and other maternal characteristics, such as ethnicity, are related to maternal beliefs about ASD.

It is surprising that mothers in the EP-L and LEP-L groups appear to hold similar beliefs about their child’s ASD regardless their child’s ASD severity. It might be that parental views of ASD severity is a proxy for family burden rather than of behavioral problems per se (Zablotsky et al., 2015). As a result, it is possible that LEP-L mothers perceive the condition as less malleable overall because they experience higher levels of family burden. Other factors related to family and parent characteristics, but not captured in this survey, such as parental self-efficacy/personal control, parental mental health and stress level, financial burden, might also influence parental views of ASD severity (Al Anbar et al., 2010; Brachlow et al., 2007; Kuhn & Carter, 2006; Liptak et al., 2008; Mandell & Novak, 2005; Schieve, Blumberg, Rice, Visser, & Boyle, 2007; Siller et al., 2014; Zablotsky, Bramlett, & Bumberg, 2015).

8.3. Associations of ASD beliefs and ethnicity/language with intervention services use

Maternal beliefs about ASD, as well as maternal views of the child’s ASD severity were each associated with weekly use of ASD intervention services. That is, mothers who more strongly believed ASD has major consequences on their child’s life or that their child’s ASD is a mystery used more ASD intervention services per week for their children, compared to mothers who held these beliefs less strongly. Also, maternal views that their child’s ASD was moderate or severe were also linked to increased use of weekly ASD treatment hours. These findings are consistent with previous research in which parental beliefs about their child (i.e., knowledge about their development) were associated with increased intervention services use (Siller et al., 2014).

Ethnicity and language was not generally associated with the use of ASD intervention services. After controlling for the belief about having the power to change ASD, however, LEP-L status was associated with the use of fewer ASD treatment hours per week. This finding suggests that not accounting for maternal beliefs regarding the ability to change a child’s ASD may obscure ethnicity based differences in ASD services use. No other links were found between maternal beliefs about ASD and ASD intervention services. It is possible that other factors may be more strongly linked to intervention services use, such as lack to health care access (Zuckerman et al., 2015; Magaña et al., 2012, Zuckerman et al., 2014). Given that poor access to care in ASD population is widespread, parental beliefs may play a secondary role. Still these results suggest that it may be important to create awareness about potential ASD consequences for a child’s life, and the importance of intervention services in improving ASD symptoms, as well as to empower parents to know that they could help improve their child’s ASD.

8.4. Limitations and future research

This study had several limitations. First, this study was cross-sectional. Thus, no inferences can be made about causation, and there is no assessment of how beliefs change over time (King et al., 2006). If parental beliefs do change over time, future research needs to explore what influences, forms, or shapes maternal beliefs about their child’s ASD as children get older. Given that other studies have reported that parents of children with ASD obtain information about ASD from popular media, anecdotal reports, and professionals (e.g., educators, Mille, Schreck, Mulick, & Butter, 2012), and that we only included families from the USA, these findings might or might not apply to families in other geographic locations because the sources or factors that shape their beliefs are likely to be different (e.g., community views; Zuckerman et al., 2015).

This study did not answer why beliefs about ASD are different in EP-W, EP-L, and LEP-L groups (Hertz-Picciotto & Delwiche, 2009; Mandell et al., 2005). Changes in services utilization and improvement in ASD symptoms might change parental beliefs about ASD (Zuckerman et al., 2015). Moreover, only mothers’ beliefs were examined; and mothers’ experiences are likely to be different from fathers’ beliefs about ASD (Hastings et al., 2005; Kayfitz, Gragg, & Robert Orr, 2010; Meirsschaut et al., 2010). Maternal report of the severity of ASD may not be consistent with a clinical diagnosis of severity, and comorbidities, such as anxiety or sleep problems, may also impact perceived severity (Jang et al., 2011; Jang & Matson, 2015; Matson et al., 2008. Additionally, future research needs to use questionnaires or instruments that can clarify whether parents from different backgrounds differ in their understanding or comprehension of ASD, as well as measures to gauge information about intervention services used (e.g., number of hours of each type of intervention, evidence based vs. non-evidence based intervention).

Regarding intervention services, this study did not examine whether parental beliefs are associated with specific interventions (e.g., evidence-based versus non-evidence-based treatments; school versus non-school services), or whether parents believe that intervention services are beneficial or useful or what child or family characteristics might predict use of evidence-based interventions for children with ASD (Bussing, Schoenberg, Rogers, Zima, & Angus, 1998; Itzchak & Zachor, 2011; Stevens et al., 2009; Yeh, Hough, McCabe, Lau & Garland, 2004; Yeh et al., 2005).

9. Conclusions

This study had three main findings. First, mothers in the EP-W, EP-L and LEP-L groups differed in their beliefs about viewing ASD a mystery. Second, only maternal views of ASD severity in the EP-W groups were linked to their beliefs about ASD. Finally, maternal beliefs about ASD having major consequences on their child’s life, and ASD being a mystery were strongly associated with their child’s use of ASD intervention services. Overall, the findings indicate that maternal beliefs can potentially inform seeking intervention treatment for children with ASD.

These findings also have clinical implications. Notably, we have some evidence that parents from diverse background might consider ASD a mystery, primary care providers could provide more information about ASD to this population to increase knowledge and understand of ASD. If beliefs about ASD are malleable, new interventions could address these maternal beliefs (e.g., the effect of ASD on the child’s development) to increase intervention service use in ASD (Al Anbar et al., 2010).

References

- Al Anbar NN, Dardennes RM, Prado-Netto A, Kaye K, & Contejean Y (2010). Treatment choices in autism spectrum disorder: The role of parental illness perceptions. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 31(3), 817–828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernheimer LP, & Weisner TS (2007). Let me just tell you what I do all day...: The family story at the center of intervention research and practice. Infants & Young Children, 20(3), 192–201. [Google Scholar]

- Blacher J, Cohen SR, & Azad G (2014). In the eye of the beholder: Reports of autism symptoms by Anglo and Latino mothers. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 8(12), 1648–1656. [Google Scholar]

- Bornstein MH, & Cote LR (2004). Who is sitting across from me? Immigrant mothers’ knowledge of parenting and children’s development. Pediatrics, 114(5), e557–e564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brachlow AE, Ness KK, McPheeters ML, & Gurney JG (2007). Comparison of indicators for a primary care medical home between children with autism or asthma and other special health care needs: National Survey of Children’s Health. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine, 161(4), 399–405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bussing R, Schoenberg NE, Rogers KM, Zima BT, & Angus S (1998). Explanatory models of ADHD: Do they differ by ethnicity, child gender or treatment status. Journal of Emotional and Behavioural Disorders, 6(4), 233–243. [Google Scholar]

- Center for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics, State and Local Area Integrated Telephone Survey (2011). Survey of pathways to diagnosis and services frequently asked questions. (2015, November 6). Retrieved June 20, 2016, from http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/slaits/spds.htm.

- Dale E, Jahoda A, & Knott F (2006). Mothers’ attributions following their child’s diagnosis of autistic spectrum disorder Exploring links with maternal levels of stress, depression and expectations about their child’s future. Autism, 10(5), 463–479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danseco Evangeline R. (1997). Parental Beliefs on Childhood Disability: Insights on culture, children development and intervention. International Journal of Disability, Development and Education, 44(1), 41–52. 10.1080/0156655970440104. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dardennes RM, Al Anbar NN, Prado-Netto A, Kaye K, Contejean Y, & Al Anbar NN (2011). Research in Developmental Disabilities, 32(3), 1137–1146. 10.1016/j.ridd.2011.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harkness S, & Super CM (1994). The developmental niche: A theoretical framework for analyzing the household production of health. Social Science & Medicine, 38(2), 217–226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harstad E, Huntington N, Bacic J, & Barbaresi W (2013). Disparity of care for children with parent-reported autism spectrum disorders. Academic Pediatrics, 13(4), 334–339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hastings RP, Kovshoff H, Ward NJ, Degli Espinosa F, Brown T, & Remington B (2005). Systems analysis of stress and positive perceptions in mothers and fathers of pre-school children with autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 35(5), 635–644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hastings RP (2003). Brief report: Behavioral adjustment of siblings of children with autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 33(1), 99–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hertz-Picciotto I, & Delwiche L (2009). The rise in autism and the role of age at diagnosis. Epidemiology (Cambridge, Mass.), 20(1) 84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hock R, & Ahmedani BK (2012). Parent perceptions of autism severity: Exploring the social ecological context. Disability and Health Journal, 5(4), 298–304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman CD, Sweeney DP, Lopez-Wagner MC, Hodge D, Nam CY, & Botts BH (2008). Children with autism: Sleep problems and mothers’ stress. Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities, 23(3), 155–165. [Google Scholar]

- Irvin DW, McBee M, Boyd BA, Hume K, & Odom SL (2012). Child and family factors associated with the use of services for preschoolers with autism spectrum disorder. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 6(1), 565–572. [Google Scholar]

- Itzchak EB, & Zachor DA (2011). Who benefits from early intervention in autism spectrum disorders? Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 5(1), 345–350. [Google Scholar]

- Jang J, & Matson JL (2015). Autism severity as a predictor of comorbid conditions. Journal of Developmental and Physical Disabilities, 27(3), 405–415. [Google Scholar]

- Jang J, Dixon DR, Tarbox J, & Granpeesheh D (2011). Symptom severity and challenging behavior in children with ASD. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 5(3), 1028–1032. [Google Scholar]

- Kayfitz AD, Gragg MN, & Robert Orr R (2010). Positive experiences of mothers and fathers of children with autism. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 23(4), 337–343. [Google Scholar]

- King GA, Zwaigenbaum L, King S, Baxter D, Rosenbaum P, & Bates A (2006). A qualitative investigation of changes in the belief systems of families of children with autism or Down syndrome. Child: Care Health and Development, 32(3), 353–369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuhn JC, & Carter AS (2006). Maternal self-efficacy and associated parenting cognitions among mothers of children with autism. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 76(4), 564–575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leigh JP, Grosse SD, Cassady D, Melnikow J, & Hertz-Picciotto I (2016). Spending by California’s department of developmental services for persons with autism across demographic and expenditure categories. Public Library of Science, 11(3), e0151970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy SE, & Hyman SL (2005). Novel treatments for autistic spectrum disorders. Mental Retardation andDevelopmental Disabilities ResearchReviews, 11(2), 131–142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin SC, & Stella MY (2015). Disparities in healthcare access and utilization among children with Autism Spectrum Disorder from immigrant non-English primary language households in the United States. International Journal of Maternal-Child Health (MCH) and AIDS, 3(2), 159–167. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liptak GS, Benzoni LB, Mruzek DW, Nolan KW, Thingvoll MA, Wade CM, & Fryer GE (2008). Disparities in diagnosis and access to health services for children with autism: Data from the National Survey of Children’s Health. Journal of Developmental & Behavioral Pediatrics, 29(3), 152–160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyons AM, Leon SC, Phelps CER, & Dunleavy AM (2010). The impact of child symptom severity on stress among parents of children with ASD: The moderating role of coping styles. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 19(4), 516–524. [Google Scholar]

- Magaña S, Parish SL, Rose RA, Timberlake M, & Swaine JG (2012). Racial and ethnic disparities in quality of health care among children with autism and other developmental disabilities. Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities, 50(4), 287–299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magaña S, Lopez K, Aguinaga A, & Morton H (2013). Access to diagnosis and treatment services among Latino children with autism spectrum disorders. Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities, 51(3), 141–153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandell DS, & Novak M (2005). The role of culture in families’ treatment decisions for children with autism spectrum disorders. Mental Retardation and Developmental Disabilities ResearchReviews, 11(2), 110–115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandell DS, Novak MM, & Zubritsky CD (2005). Factors associated with age of diagnosis among children with autism spectrum disorders. Pediatrics, 116(6), 1480–1486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matson JL, Wilkins J, & Macken J (2008). The relationship of challenging behaviors to severity and symptoms of autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Mental Health Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 2(1), 29–44. [Google Scholar]

- Meirsschaut M, Roeyers H, & Warreyn P (2010). Parenting in families with a child with autism spectrum disorder and a typically developing child: Mothers’ experiences and cognitions. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 4(4), 661–669. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer KA, Ingersoll B, & Hambrick DZ (2011). Factors influencing adjustment in siblings of children with autism spectrum disorders. Research inAutismSpectrum Disorders, 5(4), 1413–1420. [Google Scholar]

- Miller VA, Schreck KA, & Mulick JA (2012). Factors related to parents’ choice of treatment for their child with autism spectrum disorder. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorder, 6(1), 87–95. 10.1016/j.rasd.2011.03.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Moh TA, & Magiati I (2012). Factors associated with parental stress and satisfaction during the process of diagnosis of children with Autism Spectrum Disorders. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 6, 293–303. [Google Scholar]

- Moss-Morris R, Weinman J, Petrie K, Horne R, Cameron L, & Buick D (2002). The revised illness perception questionnaire (IPQ-R). Psychology andHealth, 17(1), 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- National Center for Health Statistics (2015). 2009–2010 national survey of children with special health care needs. November 6, Retrieved June 21, 2016, form www.cdc.gov/nchs/slaits/spds.htm.

- National Research Council, NRC (2001). Educating children with autism. Washington, DC: National Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Odom SL, Boyd BA, Hall LJ, & Hume K (2010). Evaluation of comprehensive treatment models for individuals with autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 40(4), 425–436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pachter LM, & Dworkin PH (1997). Maternal expectations about normal child development in 4 cultural groups. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine, 151(11), 1144–1150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parish S, Magaña S, Rose R, Timberlake M, & Swaine JG (2012). Health care of Latino children with autism and other developmental disabilities: Quality of provider interaction mediates utilization. American Journal on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities, 117(4), 304–315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pringle BA, Colpe LJ, Blumberg SJ, Avila RM, & Kogan MD (2012). Diagnostic history and treatment ofschool-aged children with Autism Spectrum Disorder and special health care needs. NCHS Data Brief No. 97. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; Retrieved June 20 2016, from http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/databriefs/db97.pdf. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ratto AB, Reznick JS, & Turner-Brown L (2015). Cultural effects on the diagnosis of autism spectrum disorder among Latinos. Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities 1088357615587501. [Google Scholar]

- Reed P, & Osborne L (2012). Impact of severity of autism and intervention time-input on child outcomes: Comparison across several early interventions. British Journal of Special Education, 39(3), 130–136. [Google Scholar]

- Schieve LA, Blumberg SJ, Rice C, Visser SN, & Boyle C (2007). The relationship between autism and parenting stress. Pediatrics, 119(Suppl. 1), S114–S121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siller M, Reyes N, Hotez E, Hutman T, & Sigman M (2014). Longitudinal change in the use of services in Autism Spectrum Disorder: Understanding the role of child characteristics, family demographics, and parent cognitions. Autism 1362361313476766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silverman C, & Brosco JP (2007). Understanding autism: Parents and pediatricians in historical perspective. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine, 161(4), 392–398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevens J, Wang W, Fan L, Edwards MC, Campo JV, & Gardner W (2009). Parental attitudes toward children’s use of antidepressants and psychotherapy. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychopharmacology, 19(3), 289–296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Super CM, & Harkness S (1986). The developmental niche: A conceptualization at the interface of child and culture. International Journal ofBehavioral Development, 9(4), 545–569. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas KC, Ellis AR, McLaurin C, Daniels J, & Morrissey JP (2007). Access to care for autism-related services. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 37(10), 1902–1912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- US Census Bureau (2014). American community survey. Retrieved June 21, 2016, from. https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/acs/.

- Vickstrom Shin, Collazo, & Bauman (2015). How Well—Still good? assessing the validity of the american community survey english-Ability question. Education and Social Stratification Branch Social, Economic, and Housing Statistics Division U.S. Census Bureau SEHSD Working Paper Number 2015–18. [Google Scholar]

- Woodgate RL, Ateah C, & Secco L (2008). Living in a world of our own: The experience of parents whohave a child with autism. Qualitative HealthResearch, 18(8), 1075–1083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeh M, Hough RL, McCabe K, Lau A, & Garland A (2004). Parental beliefs about the causes of child problems: Exploring racial/ethnic patterns. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 43(5), 605–612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeh M, McCabe K, Hough RL, Lau A, Fakhry F, & Garland A (2005). Whybother with beliefs? Examining relationships between race/ethnicity, parental beliefs about causes of child problems, and mental health service use. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 73(5), 800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zablotsky B, Bramlett M, & Blumberg SJ (2015). Factors associated with parental ratings of condition severity for children with autism spectrum disorder. Disability and Health Journal, 8(4), 626–634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zachor DA, & Itzchak EB (2010). Treatment approach, autism severity and intervention outcomes in young children. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 4(3), 425–432. [Google Scholar]

- Zuckerman KE, Mattox KM, Sinche BK, Blaschke GS, & Bethell C (2014). Racial, ethnic, and language disparities in early childhood developmental/ behavioral evaluations: A narrative review. Clinical Pediatrics, 53(7), 619–631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuckerman KE, Lindly OJ, Sinche BK, & Nicolaidis C (2015). Parenthealthbeliefs, social determinants of health, and child health services utilization among us school-age children with autism. Journal of Developmental & Behavioral Pediatrics, 36(3), 146–157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuckerman KE, Lindly OJ, & Sinche B (2016). Parent beliefs about the causes of learning and developmental problems among children with autism spectrum disorder: Results from a national survey. American Journal on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities, 121(5), 432–447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]