Abstract

Background and Aims:

To improve evidence-based addiction care in acute care settings, many hospitals across North America are developing an inpatient addiction medicine consultation service (AMCS). St Paul’s Hospital in Vancouver, Canada houses a large interdisciplinary AMCS. This study aimed to: (1) describe the current model of clinical care and its evolution over time; (2) evaluate requests for an AMCS consultation over time; (3) highlight the established clinical training opportunities and educational curriculum and (4) provide some lessons learned.

Design, Setting and Participants

A retrospective observational analysis in an urban, academic hospital in Vancouver, Canada with a large interdisciplinary AMCS, studied from 2013 to 2018, among individuals who presented to hospital and had a substance use disorder.

Measurements

Data were collected using the hospital’s electronic medical records. The primary outcome was number of AMCS consultations over time.

Findings

In 2014 the hospital’s AMCS was restructured into an academic, interdisciplinary consultation service. A 228% increase in the number of consultations was observed between 2013 (1 year prior to restructuring) and 2018 (1373 versus 4507, respectively; P = 0.027). More than half of AMCS consultations originated from the emergency department, with this number increasing over time (55% in 2013 versus 74% in 2018). Referred patients were predominantly male (> 60% in all 5 years) between the ages of 45 and 65 years. Reasons for consultation remained consistent and included: opioids (33%), stimulants (30%), alcohol (23%) and cannabis use (8%).

Conclusions

After St Paul’s Hospital in Vancouver, Canada was restructured in 2014 to a large, interdisciplinary addiction medicine consultation service (AMCS), the AMCS saw a 228% increase in the number of consultation requests with more than half of requests originating from the emergency department. Approximately two-thirds of consultation requests were for opioid or stimulant use.

Keywords: Addiction medicine education, consultation service, hospitalized patient, inpatient management, opioid use disorder, substance use disorder

INTRODUCTION

Despite the high prevalence and cost of substance use disorders, only approximately 10% of individuals eligible for treatment are in receipt of evidence-based medications [1]. While reasons for this are probably multi-factorial, lack of integration of addiction medicine training into the curricula of medical education to date (e.g. medical schools, residency programmes) is probably a large contributor [2]. Consequently, many health-care providers in current clinical practice do not have the skills required to effectively screen for, diagnose or manage a patient with a substance use disorder. This treatment gap is especially evident in acute care settings, with one study demonstrating only 11% of individuals admitted for infective endocarditis (related to injection drug use) to be either initiated or continued on addiction treatment during hospitalization [3]. This occurs despite evidence demonstrating improved health and treatment outcomes following hospital-initiated medication for substance use disorder treatment [3–5].

Existing literature demonstrates that hospitalized individuals with a substance use disorder who receive a consultation from an inpatient addiction medicine service provider (compared to those who do not) demonstrate better engagement with primary care and HIV treatment following discharge as well as reduced homelessness [6–8]. Further, a 2017 study by Wakeman et al. demonstrated hospital-based engagement with addiction consultation to increase the number of days abstinent from drugs and alcohol after discharge and reduced addiction severity. With the ongoing opioid crisis in North America, it is difficult to ignore the need for improved addiction services in acute care settings.

To address this, an increasing number of hospitals throughout North America are developing and implementing an inpatient addiction medicine consultation service (AMCS) [4, 5, 9]. Similar to other subspecialty consultation (e.g. non-admitting) services, the AMCS completes a thorough history and physical examination and provides evidence-based clinical recommendations and ongoing care for the management of either substance misuse or a substance use disorder. St Paul’s Hospital (SPH) in Vancouver, Canada has had an AMCS since the mid-90s. In 2014, the service underwent a significant academic restructuring and subsequently has become a large, interdisciplinary consultation service. Accordingly, this paper seeks to provide insight and guidance to others who may be interested to establish a similar model of care in their setting. More specifically, by highlighting the AMCS at SPH, we aim to: (1) describe the current model of clinical care and its evolution over time; (2) evaluate requests for an AMCS consultation over time (3) highlight the established clinical training opportunities and educational curriculum; and (4) provide some lessons learned.

DESIGN AND SETTING

A retrospective observational analysis was conducted of the AMCS at SPH between 2013 and 2018. Data were collected using the hospital’s electronic medical record. SPH is an acute care hospital located in downtown Vancouver, Canada. The hospital is close to Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside neighbourhood—an area rife with poverty, homelessness, mental illness and substance use.

Initial model of care (mid-1990s–2013)

The AMCS at SPH was originally created in the mid-1990s but underwent substantial restructuring in 2014 to become an interdisciplinary academic consultation service. Originally the AMCS was created to ensure that methadone maintenance therapy could be continued (or initiated) for patients with an opioid addiction while in hospital. Other forms of opioid agonist treatment (e.g. buprenorphine/naloxone) were not routinely offered, largely because they were neither easily reimbursable at the time nor available as a treatment option in Canada until 2008 (e.g. buprenorphine/naloxone). Similarly, pharmacotherapy for smoking cessation or alcohol use disorder were not provided through the AMCS at that time. The staff initially comprised four primary care physicians, two public health physicians and one general internist (seven physicians in total). The service was not interdisciplinary—it did not include social workers, nurses or trainees. One physician from the AMCS group was available daily (09:00–16:00) at weekdays to provide coverage for the hospital.

Restructuring of the model of care (2014)

In 2014, the increasing prevalence of substance use disorders among hospitalized patients at SPH was becoming an urgent concern, alongside concerns with increased substance use disorder harms in the community. In parallel, recognition was growing among hospital staff around the need for an academic service within the hospital that was able to provide comprehensive addiction care across the spectrum, as well as provide educational opportunities in addiction medicine, as SPH is an academic teaching hospital. The recruitment of a new physician director presented the opportunity to negotiate for additional resources to support a dedicated addiction medicine team. Specifically, a new incoming physician director and the retirement of a long-standing staff person provided the impetus for leadership to broaden the mandate of the AMCS to: (1) address all substance use disorders beyond opioid use disorder; (2) provide evidence-based recommendations across the spectrum from harm reduction (i.e. policies, programmes or practices that seek to minimize the negative consequences associated with ongoing substance use—an example would be the provision of safe injection supplies to a hospitalized patient) to complete abstinence (i.e. completely refraining from any use of the substance); (3) create an interdisciplinary team consisting of addiction nurses and social workers to holistically address the patient’s individual and contextual circumstances related to substance use; and (4) develop training opportunities in addiction medicine for medical trainees. The request also highlighted the potential that early access to evidence-based addiction care for individuals presenting to hospital may have on: (1) reducing rates of patients leaving hospital against medical advice [10]; (2) compliance with medical treatment while hospitalized [10]; (3) shortening duration of hospital stay; and (4) potential for reducing rates of hospital re-admission [11, 12].

Current model of care (2014–present)

Accordingly, the AMCS at SPH has grown to be a service that is operational every day of the year (i.e. 7 days a week, 365 days a year). While a second physician and one full-time social worker were initially added to the team, expansion of the service has continued steadily over time. Between Mondays and Fridays, the interdisciplinary team now comprises three addiction medicine physicians (each of whom has successfully completed speciality addiction medicine training and either the American Board of Addiction Medicine or the International Society of Addiction Medicine examination). The clinical backgrounds of each staff physician are varied, and include family medicine, internal medicine, emergency medicine and public health. Additionally, two full-time social workers are also embedded within the service to assist with motivational interviewing and psychosocial interventions related to a patient’s substance use disorder (e.g. counselling, residential treatment, coverage for medication). Lastly, one full-time addiction assessment nurse has been hired to support health-care providers in the emergency department. This nurse can be consulted directly by any health-care provider in the emergency department (i.e. the referral process is independent of a consultation to the AMCS) to complete an assessment of any patient who has a substance use disorder, and will determine their degree of discomfort or withdrawal and request a more urgent consultation from the AMCS if needed (to prevent patients from leaving hospital against medical advice). This nurse also provides harm-reduction and overdose prevention education (including the provision of a take-home naloxone kit) and will link a patient to community services if being discharged from the emergency department.

The AMCS team is available for consultation to health-care providers from both the hospital’s emergency department and/or wards between 08:00 and 18:00. At present, the service does not admit its own patients and acts purely in a consultation and follow-up capacity. Three inpatient AMCS teams exist (team A, team B and team C), with one staff physician being assigned per team to direct and oversee the provision of patient care. One staff is assigned to be ‘on call’ for a 24-hour period (08:00 until 08:00 the following day) and helps to direct patient-related phone calls and triage urgent referrals for consultations. New consultations are evenly distributed between each team utilizing a ‘drip’ system (e.g. the first new consultation is assigned to team A, the second to team B, the third to team C, and repeat). When multiple consultations are assigned per team, they are triaged by the staff physician and completed in order of priority. Members of the interdisciplinary staff (e.g. social workers and emergency assessment nurse) are shared resources among the three inpatient teams. Referrals for addiction social work involvement are primarily made by a member of the AMCS (although sometimes direct referrals from other health-care providers within the hospital occur) when it is felt the patient would benefit from their involvement.

After hours (between 18:00 and 08:00 the following day), one staff physician is assigned to provide overnight call coverage. Patients who present to hospital and are known to have a substance use disorder and would benefit from being seen by the AMCS are referred overnight, but the on-call physician only receives a telephone call if there is some urgency regarding the referral. Otherwise, the patient’s name and information is added to a new consultation list (maintained through the hospital’s electronic medical record database) that is checked by the staff on call for that day.

During the weekend, the AMCS is staffed with two addiction medicine physicians (each of whom provides 24 consecutive hours of call coverage) as well as the addiction assessment nurse (located in the emergency department). There is no weekend addiction social work coverage.

Upon discharge from hospital, if a patient does not have an addiction medicine provider to continue care in the community, they are referred (or can self-refer) to the hospital-based outpatient rapid access addiction clinic (RAAC), which is located one floor above the hospital’s emergency department. The RAAC, which become operational in 2016, provides patients with same-day access to an interdisciplinary team of addiction medicine providers (including two physicians, three nurses, one social worker and one peer support specialist). The clinic’s mandate is for short-term stabilization and management of a substance use disorder. Accordingly, a patient will typically receive care for up to 3 months in the clinic while stabilizing on their opioid agonist therapy (or other addiction treatment medications) and engaging in psychosocial interventions. Part of the work accomplished at the RAAC is identifying a community care provider who is willing to accept the patient and manage their primary care and addiction needs long-term. The RAAC is fortunate to be a part of a large network of community primary care and addiction medicine providers in Vancouver, Canada. A significant amount of outreach has been undertaken between the RAAC and these community primary care clinics to develop and strengthen relationships. This, combined with Canada’s ability to provide methadone maintenance therapy at any designated community pharmacy, allows patients to be transitioned from the RAAC to a primary care provider with relative ease.

Clinical training and education

Part of the impetus for restructuring the AMCS in 2014 was a growing recognition of the need to provide training opportunities in addiction medicine for medical trainees. Doing so would help to create a work-force that is skilled in the screening, diagnosis and management of patients with a substance use disorder. To accomplish this, several educational and training initiatives were developed.

Clinical addiction medicine fellowship

An interdisciplinary addiction medicine clinical fellowship training programme (the St Paul’s Goldcorp Addiction Medicine Fellowship) was created, with SPH being the home training site for the programme and the first cohort of fellows having graduated in 2014. Physicians from varied clinical backgrounds (including family medicine, internal medicine, emergency medicine, public health and psychiatry) acquire a breadth of experience during a 1-year period by rotating through different addiction treatment settings (e.g. hospitals, community clinics, withdrawal management and residential treatment facilities) and working with different addiction-focused preceptors. While rotating through the AMCS, the addiction medicine fellow is responsible for initially seeing consultations in the emergency department or hospital inpatient wards. After a period of approximately 2–4 weeks, the fellow assumes a leadership role with the AMCS and is responsible for: (1) triaging and assigning all new consultations; (2) taking ward calls; (3) leading AMCS morning teaching rounds (which typically consists of a 30-minute discussion of an educational case or prepared teaching on a pre-selected case); (4) delivering a formal 1-hour fellow-led structured teaching session to the medical trainees on the AMCS (approximately once every 4–6 weeks); and (5) preparing and leading one-morbidity and -mortality rounds. Following completion of the addiction medicine fellowship, graduates are competent to screen for and manage an array of substance use disorders as well as the myriad of negative consequences associated with substance use.

Addiction medicine clinical elective

An addiction medicine clinical elective was also created in 2014 to allow the opportunity for medical trainees from across the country (e.g. medical students, residents) to acquire addiction medicine exposure during their clinical training. Each medical trainee is paired with an addiction medicine provider through the AMCS for a period of 2–4 weeks. During this time, they are taught how to take a thorough addiction-focused history, complete a comprehensive physical examination and develop timely and appropriate management plans for patients who present to hospital for management of a substance use disorder or a complication related to substance use (e.g. infective endocarditis, soft tissue infection, intoxication or overdose).

Addiction medicine clinical preceptorship

An addiction medicine clinical preceptorship was also created in 2014 to allow the opportunity for health-care providers currently in practice (e.g. primary care physicians, nurse practitioners) to develop skills in addiction medicine screening and management. Similar to the clinical elective, health-care providers are paired with an addiction medicine provider through the AMCS for a period of between 1 and 12 weeks and are taught how to effectively screen for, diagnose and treat substance use disorders or medical complications related to substance use. Funding for this training is most commonly provided by the health authority within which the health-care provider works (as a way to develop skill and capacity for the provision of addiction care within their local region).

Addiction medicine clinical observership

An opportunity for addiction medicine clinical observation was created in 2016. Clinical leaders and/or health-care providers from acute care settings both in Canada (beyond just British Columbia) and the United States have previously participated in this programme, spending between 4 and 48 hours shadowing one of the AMCS addiction medicine physicians. Such an opportunity allows participants to observe the model of clinical care provided and operational flow of the AMCS. Many participants of this programme have a keen interest in developing a similar consultation service at their local hospital. Beyond this, the addiction medicine clinical observership is also utilized by a select number of medical students who have an interest in learning more about addiction medicine in their pre-clinical years.

A rigorous weekly educational curriculum was developed in parallel to the creation of the above clinical training opportunities, and includes: (1) morning teaching rounds (daily Monday–Friday, led by the addiction medicine consultation fellow); (2) noon rounds (1-hour daily Monday–Friday, led by either an addiction medicine nurse, social worker or physician); and (3) one weekly student-led journal club. In addition, monthly grand rounds (presented by an addiction medicine fellow) and morbidity and mortality rounds also occur. For a detailed example of this curriculum, see Table 1. Teaching topics rotate on a monthly basis to accommodate the schedule of most medical trainees.

Table 1.

An example of the addiction medicine consultation service’s (AMCS) teaching curriculum at St Paul’s Hospital (Vancouver, Canada).

| Week 1 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Monday | Tuesday | Wednesday | Thursday | Friday |

| 7:30–8:30: Orientation for new trainees only Conducted by fellow on service if ≥ 2 new trainees that week aIf < 2 trainees orientation is self‐directed for the new trainees and the group starts at 8:30 8:30–9:00: Extended handover Monday mornings, including all patients admitted over weekend and any complex discharge planning issues for the week. We ask that the staff from the weekend be present or call in to give handover 12:00–1:00: Social work teaching: community resources |

8:30–8:45: Handover 8:45–9:00: Fellow picks an interesting case to present 12:00–1:00: Journal club (see restructuring notes below) aAddiction grand rounds replaces journal club when it is happening |

7:30–8:30: Addiction Fellow teaching: DSM‐5 Diagnosis of Substance Use Disorders and Screening, Brief Intervention, and Referral to Treatment (SBIRT) 8:30–8:45: Handover 8:45–9:00: Fellow picks an interesting case to present 12:00–1:00: Trainees can attend other hospital rounds |

8:30–8:45: Handover 8:45–9:00: Fellow picks an interesting case to present 12:00–1:00: Nursing teaching: physician‐nurse collaboration for substance use assessments |

8:30–8:45: Handover 8:45–9:00: Fellow picks an interesting case to present 12:00–1:00: AMCS staff teaching |

| Week 2 | ||||

| Monday | Tuesday | Wednesday | Thursday | Friday |

| 7:30–8:30: Orientation for new trainees only 8:30–9:00: Extended handover 12:00–1:00: Social work teaching: complex behaviour management |

8:30–9:00: Handover and morning rounds 12:00–1:00: Journal club aGrand rounds replaces journal club when it is happening |

7:30–8:30: Addiction Medicine Fellow teaching: pain management in the setting of substance use disorders 8:30–9:00: Handover and morning rounds 12:00–1:00: Trainees can attend other hospital rounds |

8:30–9:00: Handover and morning rounds 12:00–1:00: Nursing teaching: harm reduction in acute care |

8:30–9:00: Handover and morning rounds 12:00–1:00: AMCS staff teaching |

| Week 3 | ||||

| Monday | Tuesday | Wednesday | Thursday | Friday |

| 7:30–8:30: Orientation for new trainees only 8:30–9:00: Extended handover 12:00–1:00: Social work teaching: trauma‐informed care |

8:30–9:00: Handover and morning rounds 12:00–1:00: Journal club (see restructuring notes below) aGrand rounds replaces journal club when it is happening |

7:30–8:30: Addiction Medicine Fellow Teaching: Management of alcohol and benzodiazepine withdrawal 8:30–9:00: Handover and morning rounds 12:00–1:00: Trainees can attend other hospital rounds |

8:30–9:00: Handover and morning rounds 12:00–1:00: Nursing teaching: take‐home naloxone |

8:30–9:00: Handover and morning rounds 12:00–1:00: AMCS staff teaching |

| Week 4 | ||||

| Monday | Tuesday | Wednesday | Thursday | Friday |

| 7:30–8:30: Orientation for new trainees only 8:30–9:00: Extended handover 12:00–1:00: Social work teaching: ecological approach to working with clients |

8:30–9:00: Handover and morning rounds 12:00–1:00: Journal club (see restructuring notes below) aGrand rounds replaces journal club when it is happening |

7:30–8:30: Addiction Medicine Fellow teaching: opioid agonist therapies for the clinical management of opioid use disorders 8:30–9:00: Handover and morning rounds 12:00–1:00: Trainees can attend other hospital rounds |

8:30–9:00: Handover and morning rounds 12:00–1:00: Nursing teaching: relational practice |

8:00–8:45: Morbidity and mortality rounds 8:45–9:00: Handover 12:00–1:00: AMCS staff teaching |

PARTICIPANTS

Individuals who presented to SPH and were referred to the AMCS between 2013 and 2018 were included.

MEASUREMENTS

Data pertaining to requests for an AMCS consultation at SPH in Vancouver, Canada were examined between 2013 (1 year prior to the restructuring of the AMCS) and 2018. Primary outcome of interest was the number of AMCS consultations over time. Secondary outcomes included: source of AMCS consultation, reason for consultation and number of clinical trainees over time. The Mann–Kendall trend test was performed for the number of consultations per fiscal year to determine statistical significance. This analysis was not pre-registered and the following findings should be considered exploratory.

FINDINGS

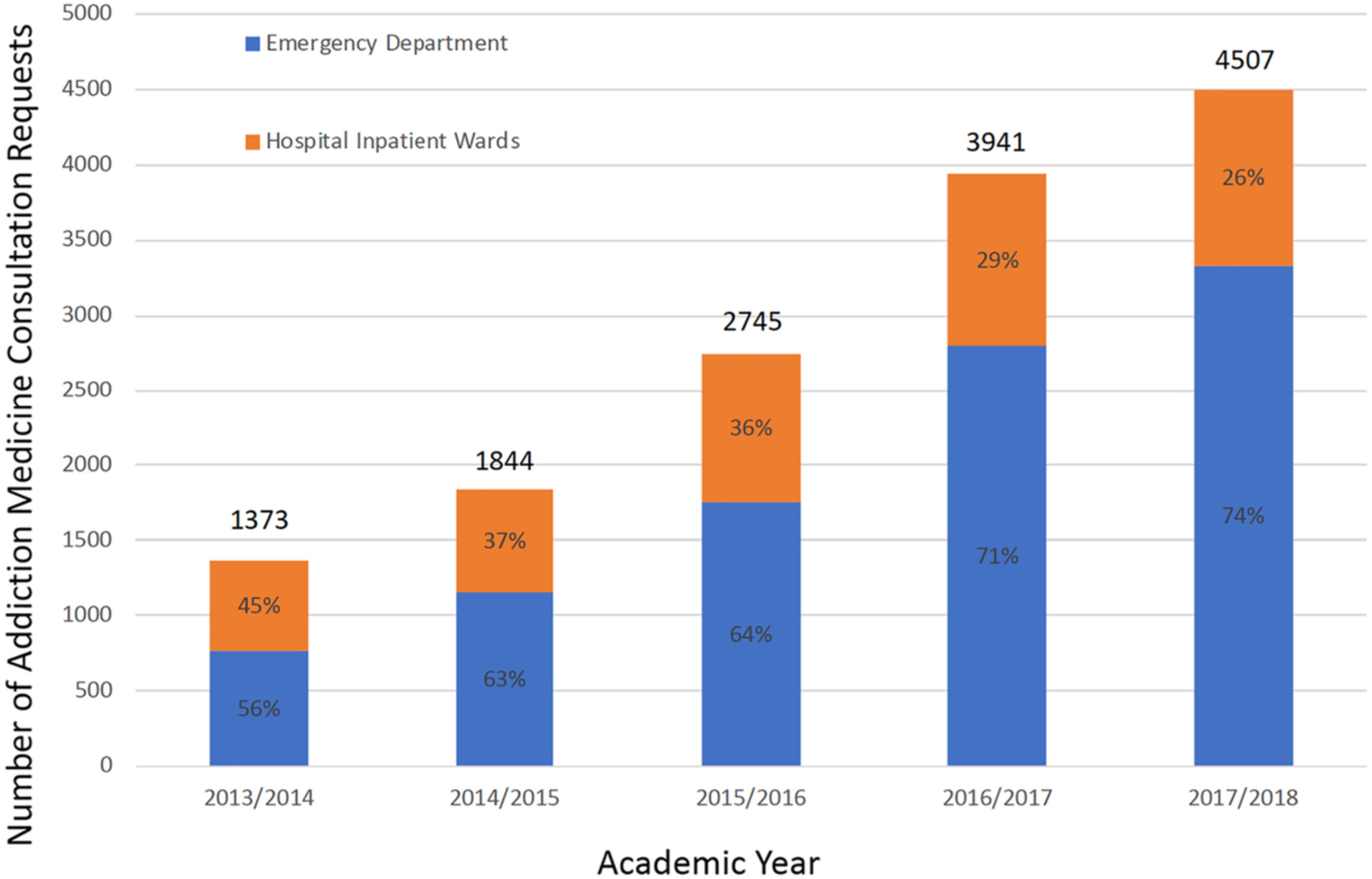

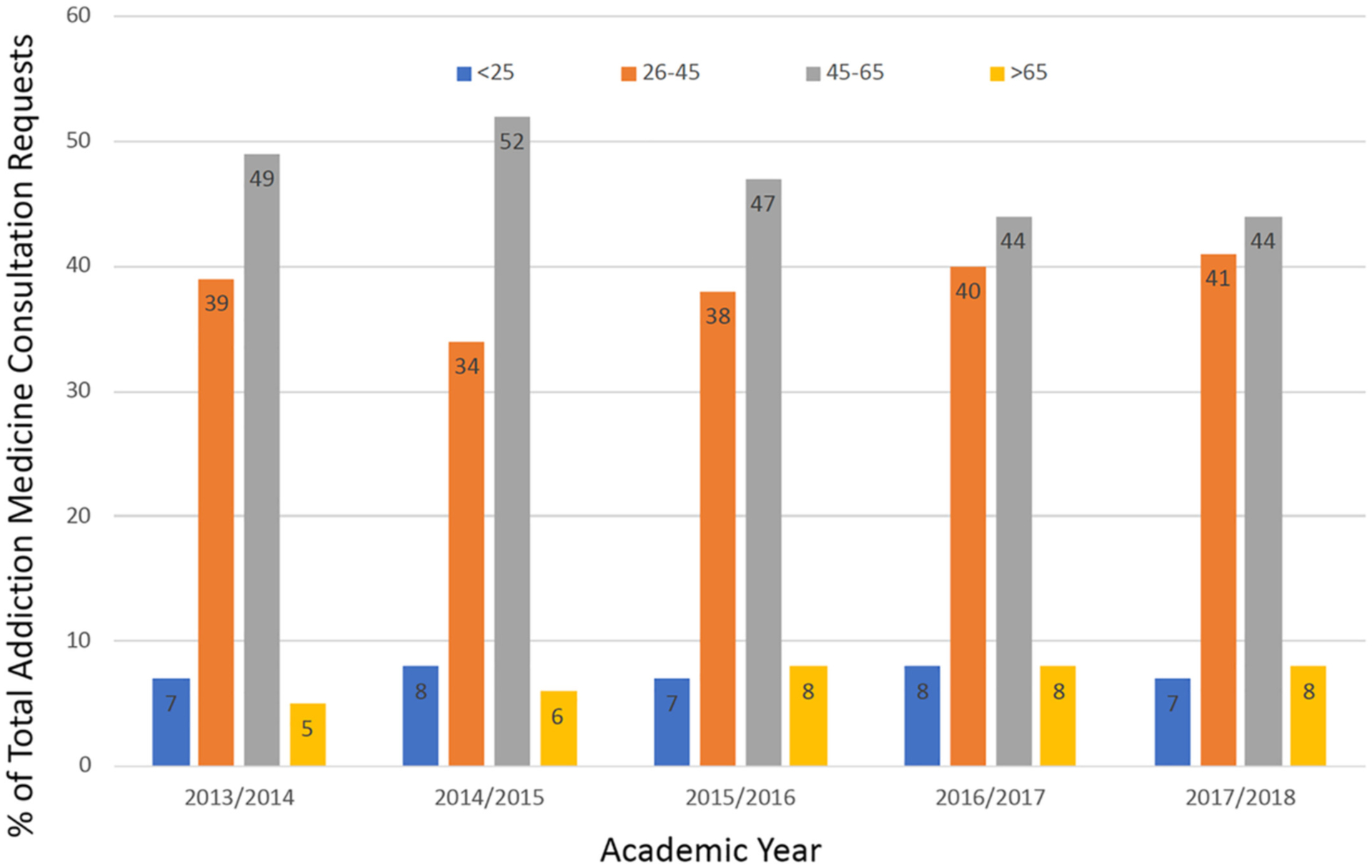

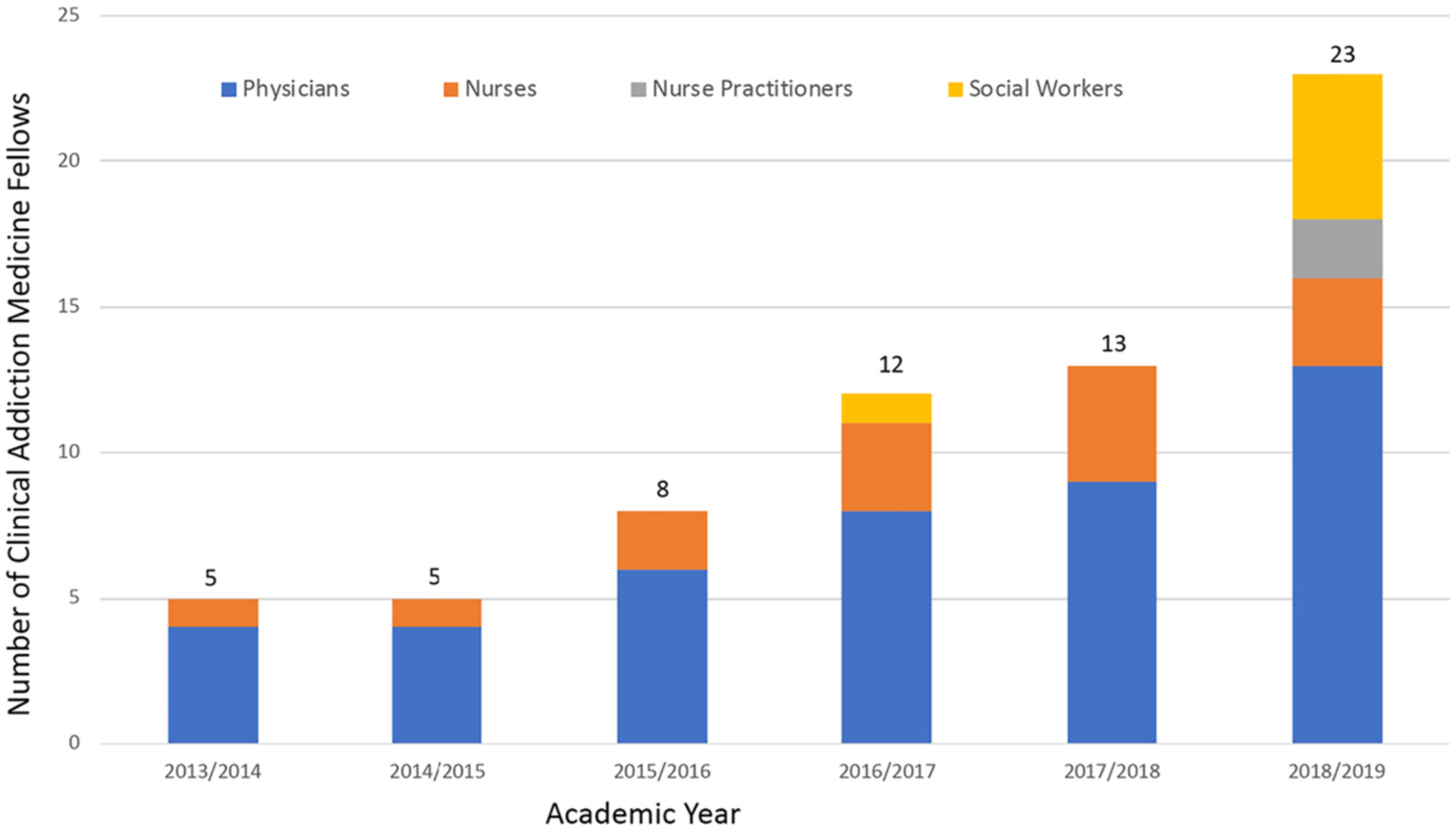

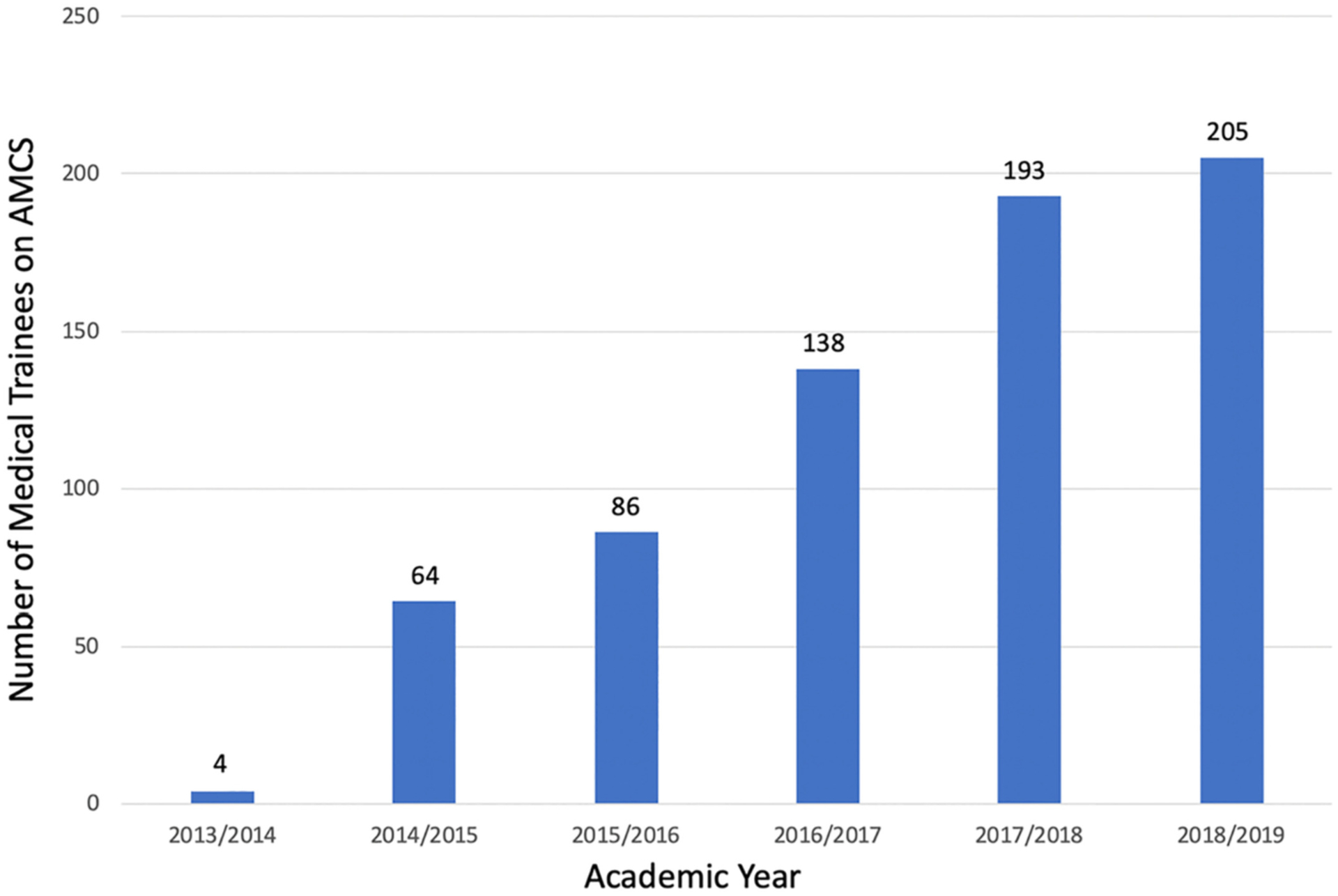

Overall, a 228% (P = 0.027) increase in the number of consultations was observed between 2013 and 2018 (1373 compared to 4507, respectively; Fig. 1). The majority of AMCS consultation requests originated from health-care providers within the emergency department (Fig. 1), with this proportion increasing over time (55% in 2013/14 versus 74% in 2017/18). Patients referred for an AMCS consultation were predominantly men (> 60% in all 5 years), with an increasing percentage being between the ages of 26 and 45 years over time (Fig. 2). Reasons for an AMCS consultation request remained consistent over time and included: opioid use (33%), stimulant use (30%), alcohol use (23%) and cannabis use (8%). Further, the number of clinical trainees increased over the study’s duration from 5 to 25 for the Clinical Addiction Medicine Fellowship and 5 to 205 for the addiction medicine clinical elective (Figs. 3 and 4, respectively).

Figure 1.

Number and source of consultation requests to the addiction medicine consultation service (AMCS) at St Paul’s Hospital, 2013/2014–2017/2018 (Vancouver, Canada)

Figure 2.

Age of patients referred to the addiction medicine consultation service (AMCS) at St Paul’s Hospital, 2013/2014–2017/2018 (Vancouver, Canada)

Figure 3.

Graduates of the St Paul’s Goldcorp addiction medicine clinical fellowship programme by discipline, 2013/2014–2018/2019 (Vancouver, Canada)

Figure 4.

Number of medical trainees who completed the University of British Columbia’s addiction medicine clinical elective, 2013/2014–2018/2019 (Vancouver, Canada)

DISCUSSION

Although addiction consultation services remain a nascent form of hospital service, in recent years there have been several other major centres that have pioneered AMCS-style services in their respective regions. To the best of our knowledge, SPH has one of the largest and most long-standing AMCS in North America, although it is difficult to gage exact size or year of establishment from the existing literature. Boston Medical Centre (BMC) implemented an addiction consultation service in 2017 and reported a similar trajectory of growth described at our centre, with more than 330 consultations within the first 26 weeks of operation [5]. Further, Priest & McCarty conducted qualitative interviews with addiction medicine physicians who operated AMCS-like services at nine US hospitals, although exact statistics on the size of each service and its growth trajectory are not reported [13]. The majority of the services described are interdisciplinary (with the inclusion of both nurse practitioners and social workers), with only one service reporting the provision of addiction support at the weekend [13]. The general principles of care described, however, mirror that of SPHs AMCS; namely, to undertake a substance use assessment and provide psychological and medical intervention, as well as pain management (if appropriate) with linkage to longitudinal addiction care [13]. In terms of longevity, the AMCS at SPH and that of the Addiction Psychiatry Service (APS) at Montefiore Medical Centre (New York, NY, USA) are comparable, with the APS being established in 1999 (only a few years after the initiation of SPH’s AMCS) [14]. The APS is also described as being interdisciplinary, with the inclusion of an addiction psychologist and social worker. Furthermore, the service also provides teaching to a variety of medical trainees [14]. In 2009, the service was described to still be working to expand its services to provide consultation to patients in the emergency department [14]. Emergency department consultation was also noted by Priest & McCarty to be an area in which the majority of the services interviewed lacked [13]. This poses a potentially large volume of missed opportunities for intervention, as the majority of AMCS consultation at SPH originated from the emergency department—and many patients who may benefit from addiction services may not ultimately be admitted to hospital.

Lessons learned

The AMCS at St Paul’s Hospital in Vancouver Canada has demonstrated steady growth since restructuring in 2014, improving access to evidence-based addiction care for individuals who present to hospital. Accordingly, a number of important lessons have been learned. Most notably has been the increasing need for support to hospital-based health-care providers in the management of individuals with a substance use disorder, as evidenced by the growing number of AMCS consultation requests during the study period. Continued expansion of the AMCS over time (with both physicians and medical trainees) was often met with hesitation by staff unsure if the volume of work available would increase in parallel. To date, this has not proved problematic and, in fact, ongoing expansion has only allowed more individuals to access evidence-based addiction care in an acute care setting over time. The need to be responsive to consultation requests has also been an important lesson. The first few hours following presentation to the emergency department can be a critical time for substance use intervention, as patients may be experiencing either severe intoxication or withdrawal. During this period, many health-care providers may feel ill-equipped to provide adequate symptom management, and failure to do so may result in the patient leaving hospital against medical advice. Early patient engagement by the AMCS (often even before an assessment by the hospital’s admission service has been completed) can help to provide rapid symptom relief, and with that the avoidance of a missed opportunity for engagement in the addiction treatment system. We suspect the efficacy of early AMCS engagement, at least in part, was reflected by the increased number of AMCS referrals requested by emergency department health-care providers over time. Lastly, the need to cultivate a non-threatening training environment with a strong emphasis on evidence-based addiction care has become increasingly recognized as a key factor in continuing to attract medical trainees.

CONCLUSION

The rapid growth of the AMCS in Vancouver, Canada, demonstrates the significant need that exists for specialized addiction services and education in acute care settings. In the wake of North America’s opioid epidemic and its frequent intersection with acute care settings, hospitals offer a tremendous opportunity to initiate evidence-based care for the management of not just opioid addiction, but all substance use disorders. This paper describes one model of care for specialist addiction consultation and education in a hospital setting, and may offer insight and guidance to other health-care professionals interested in establishing a similar model of care in their setting to improve access to evidence-based care for individuals with a substance use disorder.

Acknowledgements

L.T. is supported by the Michael Smith Foundation for Health Research (MSFHR). N.F. is supported by the MSFHR and the St Paul’s Hospital Foundation. K.A. is supported by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research Embedded Scholar Award. E.W. is supported through a Tier 1 Canada Research Chair in Addiction Medicine. S.N. is supported by the MSFHR and the University of British Columbia’s Steven Diamond Professorship in Addiction Care Innovation.

Footnotes

Declaration of interests

None

REFERENCES

- 1.National Institute on Drug Abuse, National Institute on Health, US Department of Health and Human Services. Principles of Drug Addiction Treatment: A Research-based Guide. Available at: https://www.drugabuse.gov/node/pdf/675/principles-of-drug-addiction-treatment-a-research-based-guide-third-edition (accessed 8 March 2019).

- 2.Klimas J, Small W, Ahamad K, Cullen W, Mead A, Rieb L, et al. Barriers and facilitators to implementing addiction medicine fellowships: a qualitative study with fellows, medical students, residents and preceptors. Addict Sci Clin Pract 2017; 12: 21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rosenthal ES, Karchmer AW, Theisen-Toupal J, Castillo RA, Rowley CF Suboptimal addiction interventions for patients hospitalized with injection drug use-associated infective endocarditis. Am J Med 2016; 129: 481–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Weinstein ZM, Wakeman SE, Nolan S Inpatient addiction consult service: expertise for hospitalized patients with complex addiction problems. Med Clin North Am 2018; 102: 587–601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Trowbridge P, Weinstein ZM, Kerensky T, Roy P, Regan D, Samet J, et al. Addiction consultation services - linking hospitalized patients to outpatient addiction treatment. J Subst Abuse Treat 2017; 79: 1–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Aszalos R, McDuff DR, Weintrau E, Montoya I, Schwartz R Engaging hospitalized heroin-dependent patients into substance abuse treatment. J Subst Abuse Treat 1999; 17: 149–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Englander H, Dobbertin K, Lind BK, Nicolaidis C, Graven P, Dorfman C, et al. Inpatient addiction medicine consultation and post-hospital substance use disorder treatment engagement: a propensity-matched analysis. J Gen Intern Med 2019; 34: 2796–803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Englander H, King C, Nicolaidis C, Collins D, Patten A, Gregg J, et al. Predictors of opioid and alcohol pharmacotherapy initiation at hospital discharge among patients seen by an inpatient addiction consult service. J Addict Med 2019; 14: 415–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Englander H, Weimer M, Solotaroff R, Nicolaidis C, Chan B, Velez C, et al. Planning and designing the improving addiction care team (IMPACT) for hospitalized adults with substance use disorder. J Hosp Med 2017; 12: 339–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McNeil R, Small W, Wood E, Kerr T Hospitals as a ‘risk environment’: an ethno-epidemiological study of voluntary and involuntary discharge from hospital against medical advice among people who inject drugs. Soc Sci Med 2014; 105: 59–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wei J, Defries T, Lozada M, Young N, Huen W, Tulsky J An inpatient treatment and discharge planning protocol for alcohol dependence: efficacy in reducing 30-day readmissions and emergency department visits. J Gen Intern Med 2015; 30: 365–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chan A, Palepu A, Guh DP, Sun H, Schechter MT, O’Shaughnessy MV, et al. HIV-positive injection drug users who leave the hospital against medical advice: the mitigating role of methadone and social support. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2004; 35: 56–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Priest KC, McCarty D Role of the hospital in the 21st century opioid overdose epidemic: the Addiction Medicine Consult Service. J Addict Med 2019; 13: 104–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Murphy MK, Chabon B, Delgado A, Newville H, Nicolson SE Development of a substance abuse consultation and referral service in an academic medical center: challenges, achievements and dissemination. J Clin Psychol Med Settings 2009; 16: 77–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]