Abstract

Restriction fragment length polymorphisms (RFLPs) identified in the ribosomal-DNA (rDNA) repeat were used for molecular strain differentiation of the dermatophyte fungus Trichophyton rubrum. The polymorphisms were detected by hybridization of EcoRI-digested T. rubrum genomic DNAs with a probe amplified from the small-subunit (18S) rDNA and adjacent internal transcribed spacer (ITS) regions. The rDNA RFLPs mapped to the nontranscribed spacer (NTS) region of the rDNA repeat and appeared similar to those caused by short repetitive sequences in the intergenic spacers of other fungi. Fourteen individual RFLP patterns (DNA types A to N) were recognized among 50 random clinical isolates of T. rubrum. A majority of strains (19 of 50 [38%]) were characterized by one RFLP pattern (DNA type A), and four types (DNA types A to D) accounted for 78% (39 of 50) of all strains. The remaining types (DNA types E to N) were represented by one or two isolates only. A rapid and simple method was also developed for molecular species identification of dermatophyte fungi. The contiguous ITS and 5.8S rDNA regions were amplified from 17 common dermatophyte species by using the universal primers ITS 1 and ITS 4. Digestion of the amplified ITS products with the restriction endonuclease MvaI produced unique and easily identifiable fragment patterns for a majority of species. However, some closely related taxon pairs, such as T. rubrum-T. soudanense and T. quinkeanum-T. schoenlenii could not be distinguished. We conclude that RFLP analysis of the NTS and ITS intergenic regions of the rDNA repeat is a valuable technique both for molecular strain differentiation of T. rubrum and for species identification of common dermatophyte fungi.

Dermatophyte fungi cause a variety of superficial and usually easily treated mycoses. However, nail infections (onychomycoses) due to Trichophyton rubrum are often more intractable, and relapse frequently occurs following cessation of antifungal therapy. Drug resistance is not a primary factor in such episodes, as susceptibility testing of nail isolates pre- and posttherapy usually confirms the strains to be fully sensitive to the chemotherapeutic agent used. We are currently attempting to establish whether recurrence of T. rubrum onychomycosis following an appropriate course of treatment is due primarily to treatment failure or to reinfection with a new strain. This requires the development and evaluation of an effective method for strain differentiation in T. rubrum.

Conventional (phenotypic) strain typing of dermatophyte fungi is problematic due to a lack of stable characteristics distinguishing between isolates. Most T. rubrum strains show uniformity in both microscopical and colonial appearance, although variations in colony morphology do exist. However, these apparent strain differences are often not stable on subculture or may simply be artifacts due to specific growth conditions or the presence of contaminating bacteria (21). Alternative molecular (genotypic) approaches to the subtyping of dermatophyte fungi have met with limited success. The discrimination achieved by techniques such as arbitrarily primed PCR (AP-PCR) (7, 11), random amplified polymorphic DNA analysis (RAPD) (16, 27), and restriction analysis of mtDNA (15) is generally adequate for species identification but insufficiently sensitive for strain differentiation of T. rubrum. Zhong et al. examined thirty isolates of T. rubrum by RAPD and found 22 strains to be indistinguishable and 8 to show very minor differences (27), while Liu et al., using AP-PCR, reported no differences between 8 strains of T. rubrum (11).

Interstrain polymorphisms in the spacer regions of fungal ribosomal-DNA (rDNA) repeat units have provided practical epidemiological markers for typing a range of clinically important species. Recently, fragment length polymorphisms present in the rDNA nontranscribed spacer (NTS) regions have been used to type both Candida krusei (4) and Aspergillus fumigatus (19), and nucleotide sequence variations in the internal transcribed spacers (ITS I and II) have been shown to differentiate strains of Pneumocystis carinii f. sp. hominis (10). We have examined molecular variation in the rDNA repeats of T. rubrum and other dermatophyte fungi and identified length variations in the NTS region which have been used for strain differentiation.

Additional analysis of the ITS regions has provided a simple and reproducible molecular method for dermatophyte species characterization, utilizing MvaI restriction enzyme patterns of PCR-amplified ITS I and ITS II regions. In this report we show that polymorphism analysis of the rDNA intergenic regions is a valuable technique both for strain typing and species identification in this important group of pathogenic fungi.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Dermatophyte isolates.

Clinical isolates of T. rubrum and other dermatophyte species were cultured from skin, hair, and nail samples submitted to the Leeds PHLS Mycology Reference Laboratory by general practitioners and hospital dermatology departments in the United Kingdom. Isolates from Iceland, Finland, Holland, and Germany were received during the course of a clinical trial from patients with onychomycosis in these countries. Cultures of six dermatophyte species were provided by Gillian Midgley, Institute of Dermatology, St. Thomas’ Hospital, London, United Kingdom, and three type cultures were obtained from the National Collection of Pathogenic Fungi, PHLS Mycology Reference Laboratory, Bristol, United Kingdom.

All clinical isolates were identified to species level on the basis of standard biochemical tests, microscopy, and colony characteristics. Strains grown from clinical samples were subcultured once to confirm purity, and cultures were maintained in sterile water and on Sabouraud agar slopes.

Isolation of fungal DNA.

Strains were cultured in 100 ml of Sabouraud liquid medium (Oxoid; Unipath Ltd., Basingstoke, United Kingdom) and incubated with shaking for up to 7 days at 27°C. Hyphal growth was harvested by filtration and washed twice with 100 ml of sterile saline. Strains which could not be processed immediately were frozen at −80°C prior to extraction. Liquid nitrogen was added to 2 to 3 g of frozen hyphae in a prechilled mortar, and the cells were ground finely with a pestle. Approximately 200 mg of frozen, ground mycelium was placed in a 1.5-ml microcentrifuge tube, and 600 μl of lysis buffer (400 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0; 60 mM EDTA; 150 mM NaCl; 1% sodium dodecyl sulfate [SDS]; 40 mg/ml proteinase K) was added. Samples were incubated for 1 h at 60°C with occasional mixing, and then 100 μl of 5 M sodium perchlorate was added and incubation continued for a further 15 min at 60°C. Tubes were cooled on ice, and extraction was performed with 500 μl of ice-cold chloroform and then with equal volumes of phenol-chloroform-isoamyl alcohol (25:24:1; pH 8.0; BDH Lab Supplies, Poole, United Kingdom) and finally with chloroform. Purified nucleic acids were precipitated with 2 volumes of ice-cold 95% ethanol, washed twice in 500 μl of 70% ethanol, air dried, and resuspended in 150 to 200 μl of sterile water.

Detection of rDNA polymorphisms in T. rubrum.

Ten micrograms (∼10 μl) of each DNA sample was digested for 18 h with 15 U of restriction endonuclease EcoRI (MBI Fermentas, IGI Ltd., Sunderland, United Kingdom) in a total volume of 20 μl. Samples were electrophoresed in 0.8% agarose gels, stained with ethidium bromide, and photographed. Gel denaturation and neutralization and immobilization of DNA fragments onto nylon membranes (Hybond-N; Amersham International plc, Little Chalfont, United Kingdom) by Southern transfer were performed according to standard protocols.

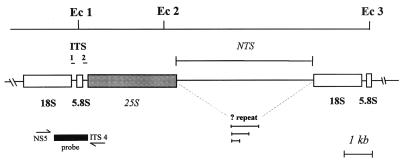

An rDNA probe was amplified from template DNA of T. rubrum NCPF 295 by using universal primers NS 5 (5′ AACTTAAAGGAATTGACGGAAG 3′) and ITS 4 (5′ TCCTCCGCTTATTGATATGC 3′) (26). The 1,219-bp probe consisted of a 550-bp fragment from the 3′ end of the 18S rDNA plus the adjacent ITS I, 5.8S rDNA, and ITS II regions (Fig. 1). The probe was labelled by incorporating digoxigenin (DIG)-labelled dUTP (Boehringer-Mannheim UK Ltd., Lewes, United Kingdom) into a standard PCR mixture. The PCR mixture contained reaction buffer (50 mM KCl, 10 mM Tris-HCl [pH 9.0], 0.1% Triton X-100), 1.5 mM magnesium chloride, a DIG-deoxynucleoside triphosphate (dNTP) mix (0.2 mM each of dATP, dCTP, dGTP; 0.13 mM dTTP; 0.07 mM DIG-11-dUTP, alkali labile, pH 7.0), 30 pmol each of primers NS 5 and ITS 4 (MWG-Biotech, Milton Keynes, United Kingdom), 5 U of Taq polymerase (Stratech Scientific Ltd., Luton, United Kingdom), and approximately 10 ng of diluted template DNA, made up to a total volume of 100 μl with pure water. PCR cycling conditions were 35 cycles of 95°C for 1 min, 55°C for 1 min, and 72°C for 2 min, followed by an extension step of 72°C for 10 min. The probe was gel purified with a GX resin system (Nucleon Biosciences, Coatbridge, United Kingdom), and the probe concentration was adjusted to ∼20 ng/ml in a 15-ml volume of hybridization solution (5× SSC [1× SSC is 0.15 M NaCl plus 0.015 M sodium citrate], 0.1% N-lauroylsarcosine, 0.02% SDS, 1% blocking reagent [formulation unknown; Boehringer-Mannheim]). Hybridization was carried out for 18 h at 65°C, followed by four stringent washes (twice for 5 min at 25°C with 2× SSC–0.1% SDS and twice for 15 min at 65°C with 0.5× SSC–0.1% SDS). Bound, labelled probe was conjugated with anti-DIG-AP Fab fragments (Boehringer-Mannheim), and signal was developed by using the chemiluminescent substrate CSPD (Boehringer-Mannheim).

FIG. 1.

EcoRI restriction map of the rDNA repeat unit of T. rubrum. The fragment between restriction sites Ec 1 and Ec 2 may encompass the whole of the 25S gene and is of constant length (∼3 kb) in all strains. The fragment between sites Ec 2 and Ec 3 represents the NTS region and the 18S gene and shows fragment length polymorphisms in several T. rubrum strains. One hypothesis to account for these length variations is the presence of a repetitive element located in the NTS region.

Detection of Mva I restriction site polymorphisms in the ITS I and II regions of the rDNA.

The contiguous ITS I, 5.8S, and ITS II regions were amplified from a range of dermatophyte species by using the conserved primers ITS 1 (5′ TCCGTAGGTGAACCTGCGG 3′) and ITS 4 (26). The PCR mixture and amplification conditions were the same as those used for preparing the labelled probe, but the DIG-dNTP labelling mix was replaced with a standard mix producing a final concentration of 0.2 mM of each dNTP. Species-characteristic restriction site polymorphisms were detected by digestion of the amplified product with the restriction enzyme MvaI (MBI Fermentas), which recognizes the sequence 5′ CC(T/A)GG 3′. Digest fragments were separated by electrophoresis in 2% agarose gels and stained with ethidium bromide prior to photography.

RESULTS

Strain typing of T. rubrum.

From the results of the probe hybridizations and using sequence data of the T. rubrum 18S and ITS I and ITS II regions (1, 2), a provisional restriction map of the rDNA repeat was constructed (Fig. 1). An EcoRI fragment comprising ITS I, all of the 18S gene, and an indeterminate length of the NTS region was polymorphic in size between strains. In most isolates, the length of this fragment varied over the range 4.7 to 5.8 kb (Fig. 2A), although a smaller proportion of strains had either two or four polymorphic bands in the same region (Fig. 2B). A second lower-molecular-weight EcoRI fragment of approximately 3 kb (not shown) was invariant in size and represented an uncharacterized segment of the 25S gene and the ITS II region proximal to this (Fig. 1). The probe also detected a third, high-molecular-weight band which was approximately equal in length to the sum of the sizes of the first two fragments. This may represent a subpopulation of repeat units from which one of the two EcoRI sites has been lost.

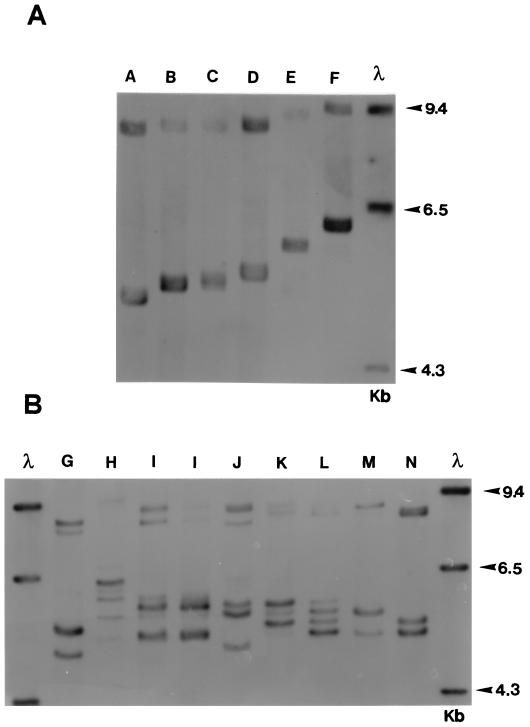

FIG. 2.

Southern blot of EcoRI-digested genomic DNA from 14 strains of T. rubrum, probed as described in Materials and Methods. Two distinct types of restriction fragment length polymorphism are present in the rDNA repeat of these strains. The six strains (types A to F) illustrated in panel A have a single variable fragment in the size range 4.7 to 5.8 kb, while the eight pattern types (G to N) shown in panel B have multiple variable fragments (either two or four) in the same region. An additional high-molecular-weight variable fragment(s) is present in the 9.0-kb region of all strains. The single, invariant band at 3.0 kb representing fragment Ec 1 to Ec 2 (Fig. 1) is not shown. Molecular weights of standards (in thousands) are given to the right of each panel. λ = molecular weight marker (HindIII-digested lambda DNA).

Six different single band types (types A to F [Fig. 2A]) and eight multiple band patterns (types G to N [Fig. 2B]) were recognized, making a total of 14 patterns overall among the 50 isolates examined. One pattern, DNA type A, was found for 19 of 50 (38%) of strains and was present in isolates from all geographic locations. Three other pattern types were prevalent: DNA types B (9 of 50 strains; 18%), C (5 of 50 strains; 10%), and D (6 of 50 strains; 12%). All other types were represented by single isolates only, except for two strains of DNA type I (Table 1; Fig. 2B). There was no obvious correlation between any pattern type and the geographical or clinical origin of an isolate, although such associations may not have been apparent due to the relatively small number of strains examined. Ten isolates with different rDNA profiles (rDNA types A, B, C, D, E, F, J, K, L, and M) were evaluated by RAPD using the primer OPK-17 (27). No clearly evident variations in RAPD pattern were found between any of these strains (data not shown).

TABLE 1.

Strain details and DNA types for 50 clinical isolates of T. rubrum

| Isolate no. | Source | Clinical site | DNA type |

|---|---|---|---|

| 97-12329 | UKa | Skin | A |

| 97-12444 | UK | Toe skin | A |

| 97-12912 | UK | Toenail | A |

| 97-12959 | UK | Toenail | A |

| 97-13550 | UK | Toenail | A |

| 97-14358 | UK | Toe web | A |

| 97-15521 | UK | Toenail | A |

| 97-N 221 | Iceland | Toenail | A |

| 97-N 250 | Iceland | Toenail | A |

| 97-N 251 | Iceland | Toenail | A |

| 95-T2/7 | Iceland | Toenail | A |

| 95-T2/14 | Iceland | Toenail | A |

| 95-T2/17 | Iceland | Toenail | A |

| 96-T2/1852 | Germany | Toenail | A |

| 96-T2/1895 | Germany | Toenail | A |

| 96-T2/2248 | Iceland | Toenail | A |

| 96-T2/3891 | Holland | Toenail | A |

| 96-T2/3962 | Finland | Toenail | A |

| 97-14468 | UK | NKb | A |

| LM 101 | UK | NK | B |

| 94-6597 | UK | Leg | B |

| 95-1295 | UK | Leg | B |

| 97-12698 | UK | Toenail | B |

| 97-13826 | UK | Toenail | B |

| 97-14279 | UK | Skin | B |

| 97-14482 | UK | Toenail | B |

| 95-T2/24 | Iceland | Toenail | B |

| 95-T2/27 | Iceland | Toenail | B |

| NCPF 295 | UK | Foot skin | C |

| 97-12335 | UK | Toenail | C |

| 97-14166 | UK | Groin | C |

| 97-14462 | UK | Foot skin | C |

| 96-T2/2240 | Iceland | Toenail | C |

| 93-DS.TrP | UK | Finger skin | D |

| 97-12063 | UK | Foot skin | D |

| 98-551 | UK | Foot skin | D |

| 95-T2/11 | Iceland | Toenail | D |

| 95-T2/13 | Iceland | Toenail | D |

| 95-T2/253 | Finland | Toenail | D |

| 96-T2/3877 | Iceland | Toenail | E |

| 97-12332 | UK | Toenail | F |

| 96-T2/3964 | Finland | Toenail | G |

| 96-8533 | UK | Toenail | H |

| LM 102 | UK | NK | I |

| 95-764 | UK | Skin | I |

| 98-5693 | UK | Nail | J |

| 97-14581 | UK | Foot skin | K |

| 95-T2/20 | Iceland | Toenail | L |

| 97-12790 | UK | Toenail | M |

| 97-12496 | UK | Toenail | N |

UK, United Kingdom

NK, not known.

Species identification of dermatophytes.

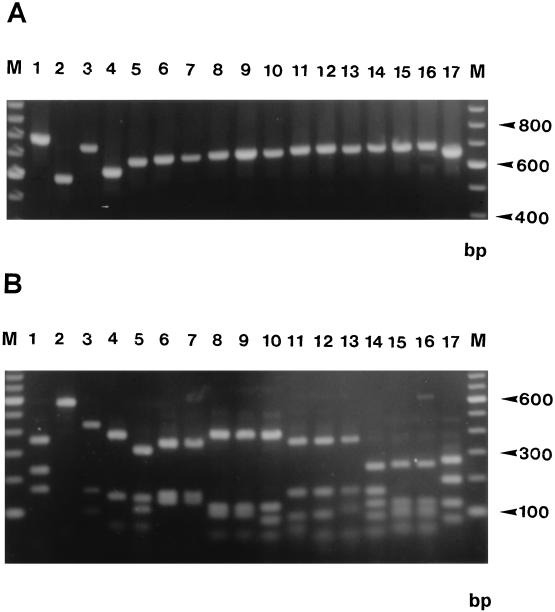

The ITS I, 5.8S, and ITS II region amplified from Trichophyton rubrum by using primers ITS 1 and ITS 4 was 692 bp in length (1). The amplification products obtained from 10 other Trichophyton spp. and from Microsporum persicolor were of approximately equivalent size (Fig. 3A). The ITS regions amplified from Epidermophyton floccosum and Microsporum canis were larger than that of T. rubrum by about 50 bp, while those from Trichophyton terrestre, Microsporum gypseum, and Microsporum audouinii were smaller, at approximately 670, 610, and 590 bp, respectively. Amplified products from all species had between two and four recognition sites for MvaI, except for M. audouinii, which had none. Thirteen different MvaI restriction patterns were produced from 17 dermatophyte species. Nine patterns were unique to one species only (M. audouinii, M. canis, M. gypseum, M. persicolor, E. floccosum, Trichophyton mentagrophytes, T. terrestre, Trichophyton verrucosum, and Trichophyton violaceum), while four patterns were shared between each of two Trichophyton species (T. quinkeanum and T. schoenlenii, T. soudanense and T. rubrum, T. equinum and T. tonsurans, and T. concentricum and T. erinacei) (Fig. 3B).

FIG. 3.

Agarose gel electrophoresis of PCR-amplified ITS regions (A) and MvaI restriction digests of amplified ITS products (B) from 17 dermatophyte species. All products were electrophoresed in 2% agarose gels and stained with ethidium bromide. Lanes: 1, E. floccosum DS.EF; 2, M. audouinii SJ.EM 4875; 3, M. canis 97/12400; 4, M. gypseum SJ.EM 3928; 5, M. persicolor NCPF 356; 6, T. concentricum NCPF 600; 7, T. erinacei LM 47; 8, T. quinkeanum LM 54; 9, T. schoenleinii SJ.EV 327; 10, T. verrucosum 98/4545; 11, T. rubrum NCPF 295; 12, T. soudanense 98/7676; 13, T. violaceum SJ.EM 7115; 14, T. mentagrophytes DS.TMvM; 15, T. equinum SJ.A1; 16, T. tonsurans SJ.EM 6717; 17, T. terrestre LM 39.

Three clinical isolates with atypical or equivocal species characteristics could be unambiguously assigned to specific taxa by the ITS PCR method (data not shown).

Stability and reproducibility of strain typing and species identification.

Five separate DNA extractions were made over a period of 8 months on strain T. rubrum NCPF 295. Multiple DNA extractions, restriction digests, and Southern blotting were also performed for several other isolates for comparative purposes. In each case, the rDNA types resulting from repeat extractions were unchanged (data not shown).

The results obtained from a comparison of MvaI ITS digestion and conventional species identification were fully concordant for multiple isolates of certain species, including 55 T. rubrum isolates 18 T. mentagrophytes isolates, 8 T. tonsurans isolates, 6 T. erinacei isolates, and 5 M. canis isolates (data not shown). The species-characteristic patterns were reproducible irrespective of the strain phenotype, geographic origin, frequency of subculture, or storage conditions. Additionally, the method demonstrated the stability of T. rubrum, in that T. rubrum NCPF 295, isolated several decades ago, showed a restriction pattern identical to that of strains from the modern era.

DISCUSSION

We have developed a molecular method for strain differentiation in T. rubrum to determine whether recurrent posttreatment onychomycosis is due to treatment failure or to reinfection with a new fungal strain. Strain typing of dermatophytes has a number of other potential clinical and epidemiological applications. Nail infections due to T. rubrum are increasingly being treated with a new generation of systemic triazole and allylamine antifungal agents. Treatment courses of either continuous or pulsed therapy (22) typically last for several months, increasing the potential for acquisition of resistance to some of these compounds (5). If resistant isolates do emerge, typing methods will allow these strains to be characterized and their occurrence and distribution to be monitored.

The ability to type dermatophytes could also provide new insights into the epidemiology, population biology and pathogenicity of these fungi. For example, our data suggest that only a limited number of strains are prevalent in T. rubrum infections, with four pattern types (DNA types A to D) predominant among our clinical isolates and one type (DNA type A) accounting for over a third of all strains. One reason for this may be a low discrimination index for the typing system we describe. However, this distribution pattern may also have resulted from a recent and widespread dissemination of these particular strain types, which may possess enhanced infectivity, invasiveness, or other virulence characteristics. The etiology of dermatophyte infection in the United Kingdom is undoubtedly linked to factors such as recent changes in foot hygiene, combined with an increased usage of communal recreational facilities such as swimming pools and leisure centers. These developments may have provided ideal conditions for the proliferation of a single or small number of particularly anthropophilic or pathogenic T. rubrum clones. This type of strain distribution has been termed epidemic or explosive spread in prokaryotes (14).

The success in typing dermatophytes according to phenotypic criteria such as colony morphology or biochemical reactivity has been limited. Molecular approaches such as RAPD have similarly failed to identify substantive intraspecific polymorphisms within T. rubrum or other dermatophyte species (7, 11, 16, 27). What little variations were seen for RAPD between isolates of T. rubrum were minor, and reduced-specificity PCR amplifications are notorious for problems of reproducibility (23). These results may reflect an innate lack of chromosomal variation in these fungi, perhaps as a consequence of the clonal population structure suggested above. However, our results demonstrate that substantial molecular diversity is present in the rDNA repeat of T. rubrum, and interstrain variations elsewhere in the genome may subsequently be identified by molecular methods other than RAPD, such as microsatellite typing. Interestingly, an early report also demonstrated rDNA variation in the dimorphic pathogenic fungus Histoplasma capsulatum (24). This species is a member of the order Onygenales, a monophyletic lineage from whose ancestor the family of dermatophyte fungi (Arthrodermataceae) also evolved (9).

The molecular polymorphisms we have identified may be due to variations in the copy number of a repetitive element present in the nontranscribed intergenic regions of the rDNA cistrons. Similar repetitive units have been identified in the rDNA intergenic regions of higher organisms such as Xenopus laevis (25) and Drosophila melanogaster (12), as well as in fungi such as Schizophyllum commune (20), Pythium ultimum (8), and C. krusei (3). The size difference separating each of the fragments in types A to D appears to be about 100 to 150 bp, which may indicate the presence of a repeating sequence of this length in the T. rubrum NTS region. We are currently attempting to confirm the existence and genetic identity of this presumptive repetitive element in our laboratory. The size difference separating types D, E, and F is somewhat larger than 150 bp, and fragments of intermediate sizes may be identified from a wider sample of isolates. The multiple banding patterns (types G to M) may be the result of heterogeneities in the number of repeat units within different copies of the rDNA cistrons of individual strains (8). If T. rubrum is diploid, then these isolates may additionally demonstrate heterozygosity in the rDNA interrepeats derived from each chromosomal homologue (13). A third possibility is that these strains represent heterokaryons, with different rDNA polymorphisms originating from each haploid mate (20).

While strain typing is useful for studying the clinical and epidemiological aspects of onchomycoses, species identification has a wider role in monitoring the demographic distribution and changes in frequency of specific dermatophyte infections (6). Accurate identification of dermatophytes can be time-consuming and requires extensive familiarity with the microscopical and cultural characteristics of these taxa (21). A molecular solution to problems of species identification in the commercially important black truffle fungi (Tuber melanosporum) involved simple restriction analysis of the amplified ITS region (18). The same approach has proved successful for the dermatophytes, although some closely related taxa cannot be distinguished. These include T. quinkeanum and T. schoenlenii, which have been shown to be closely related by mtDNA restriction analysis (17). Similarly, the 18S rDNA sequence data for T. soudanese and T. rubrum, species which have the same MvaI profile, are practically identical (9). No pattern differences were observed among T. mentagrophytes varieties interdigitale, granulosum, mentagrophytes, or sulphureum. Overall, the discrimination achieved by MvaI digestion of the ITS regions correlates well with species identification obtained by AP-PCR (7, 11). Further refinements of our system may enable the lack of discrimination evident from the above examples to be overcome. However, we cannot exclude the possibility that some of these apparently anomalous results will be resolved when dermatophyte taxonomy is fully defined on the basis of comparative sequence data.

The MvaI restriction patterns are highly reproducible and consistent for several species, indicating that the ITS regions in dermatophytes are conserved. This contrasts with pathogenic fungi such as P. carinii, for which sequence variability of the ITS regions is sufficient for strain characterization (10). Strain-specific variations in T. rubrum are located in the NTS rather than the ITS intergenic regions, and the demonstration of these rDNA polymorphisms has provided the first molecular technique for strain differentiation in this species.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We are grateful to the Janssen Research Foundation, Beerse, Belgium, who provided the financial support for this project.

REFERENCES

- 1.Berbee M L, Yoshimura A, Sugiyama J, Taylor J W. Is Penicillium monophyletic—an evaluation of phylogeny in the family Trichocomaceae from 18S, 5.8S and ITS ribosomal DNA sequence data. Mycologia. 1995;87:210–222. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bowman B H, Taylor J W, White T J. Molecular evolution of the fungi: human pathogens. Mol Biol Evol. 1992;9:893–904. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a040766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Carlotti A, Srikantha T, Schröppel K, Kvaal C, Villard J, Soll D R. A novel repeat sequence (CKRS-1) containing a tandemly repeated sub-element (kre) accounts for differences between Candida krusei strains fingerprinted with the probe CkF1,2. Curr Genet. 1997;31:255–263. doi: 10.1007/s002940050203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Carlotti A, Chaib F, Couble A, Bourgeois N, Blanchard V, Villard J. Rapid identification and fingerprinting of Candida krusei by PCR-based amplification of the species-specific repetitive polymorphic sequence CKRS-1. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:1337–1343. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.6.1337-1343.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Evans E G V. Causative pathogens in onychomycosis and the possibility of treatment resistance: a review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1998;38:S32–S56. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(98)70481-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ginter G, Reiger E, Heigl K, Propst E. Increasing frequency of onychomycoses. Is there a change in the spectrum of infectious agents? Mycoses. 1996;39(Suppl. 1):118–122. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0507.1996.tb00517.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gräser Y, el Fari M, Presber W, Sterry W, Tietz H-J. Identification of common dermatophytes (Trichophyton, Microsporum, Epidermophyton) using polymerase chain reactions. Br J Dermatol. 1998;138:576–582. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.1998.02165.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Klassen G R, Buchko J. Subrepeat structure of the intergenic region in the ribosomal DNA of the oomycetous fungus Pythium ultimum. Curr Genet. 1990;17:125–127. doi: 10.1007/BF00318381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Leclerc M C, Philippe H, Guého E. Phylogeny of dermatophytes and dimorphic fungi based on large subunit ribosomal RNA sequence comparisons. J Med Vet Mycol. 1994;32:331–341. doi: 10.1080/02681219480000451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lee C-H, Helweg-Larsen J, Tang X, Jin S, Li B, Bartlett M S, Lu J-J, Lundgren B, Lundgren J D, Olsson M, Lucas S B, Roux P, Cargnel A, Atzori C, Matos O, Smith J W. Update on Pneumocystis carinii f. sp. hominis typing based on nucleotide sequence variations in internal transcribed spacer regions of rRNA genes. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:734–741. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.3.734-741.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liu D, Coloe S, Pedersen J, Baird R. Use of arbitrarily primed polymerase chain reaction to differentiate Trichophyton dermatophytes. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1996;136:147–150. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1996.tb08040.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Long E O, Dawid I O. Restriction analysis of spacers in ribosomal DNA of Drosophila melanogaster. Nucleic Acids Res. 1979;7:205–215. doi: 10.1093/nar/7.1.205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Magee B B, d’Souza T M, Magee P T. Strain and species identification by restriction fragment length polymorphisms in the ribosomal DNA repeat of Candida species. J Bacteriol. 1987;169:1639–1643. doi: 10.1128/jb.169.4.1639-1643.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Maynard Smith J, Smith N H, O’Rourke M, Spratt B G. How clonal are bacteria? Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:4384–4388. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.10.4384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mochizuki T, Watanabe S, Uehara M. Genetic homogeneity of Trichophyton mentagrophytes var. interdigitale isolated from geographically distant regions. J Med Vet Mycol. 1996;34:139–143. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mochizuki T, Sugie N, Uehara M. Random amplification of polymorphic DNA is useful for the differentiation of several anthropophilic dermatophytes. Mycoses. 1997;40:405–409. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0507.1997.tb00175.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nishio K, Kawasaki M, Ishizaki H. Phylogeny of the genera Trichophyton using mitochondrial DNA analysis. Mycopathologia. 1991;11:127–132. doi: 10.1007/BF00442772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Paolocci F, Rubini A, Granetti B, Arcioni S. Typing Tuber melanosporum and Chinese black truffle species by molecular markers. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1997;153:255–260. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1997.tb12582.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Radford S A, Johnson E M, Leeming J P, Millar M R, Cornish J M, Foot A B M, Warnock D W. Molecular epidemiological study of Aspergillus fumigatus in a bone marrow transplantation unit by PCR amplification of ribosomal intergenic spacer sequences. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:1294–1299. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.5.1294-1299.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Specht C A, Novotny C P, Ullrich R C. Strain specific differences in ribosomal DNA from the fungus Schizophyllum commune. Curr Genet. 1984;8:219–222. doi: 10.1007/BF00417819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Summerbell R, Kane J. Physiological and other special tests for identifying dermatophytes. In: Kane J, Summerbell R, editors. Laboratory handbook of dermatophytes. Belmont, Calif: Star Publishing Co.; 1997. pp. 45–79. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tosti A, Priaccini B M, Stinchi C, Venturon N, Bardazzi F, Colombo M D. Treatment of dermatophyte nail infections: an open randomized study comparing intermittent terbinafine therapy with continuous terbinafine treatment and intermittent itraconazole therapy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1996;34:595–600. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(96)80057-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tyler K D, Wang G, Tyler S D, Johnson W M. Factors affecting reliability and reproducibility of amplification-based DNA fingerprinting of representative bacterial pathogens. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:339–346. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.2.339-346.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vincent R D, Goewert R, Goldman W E, Kobayashi G S, Lambowitz A M, Medoff G. Classification of Histoplasma capsulatum isolates by restriction fragment polymorphisms. J Bacteriol. 1986;165:813–818. doi: 10.1128/jb.165.3.813-818.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wellauer P, Dawid I, Brown D, Reeder R. The molecular basis for length heterogeneity in ribosomal DNA from Xenopus laevis. J Mol Biol. 1976;105:461–486. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(76)90229-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.White T J, Bruns T, Taylor J. Amplification and direct sequencing of fungal ribosomal RNA genes for phylogenetics. In: Innis M A, editor. PCR protocols: a guide to methods and applications. London, United Kingdom: Academic Press; 1990. pp. 315–322. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhong Z, Li R, Li D, Wang D. Typing of common dermatophytes by random amplification of polymorphic DNA. Jpn J Med Mycol. 1997;38:239–246. [Google Scholar]