INTRODUCTION

While post-acute sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 are increasingly recognized,1 studies are still needed to identify risk factors, treatment options, and the duration and evolution of symptoms. Vaccination against SARS-CoV-2 prevents infection and acute complications. However, once infected, it is unclear whether vaccination can help prevent or improve long COVID or post-acute sequelae of SARS-CoV-2.2,3 In this study, we describe the association of vaccination and the evolution of six cardinal symptoms embodying post-acute sequelae of SARS-CoV-2.

METHODS

From April 23 to July 27, 2021, an online survey was sent to 6987 individuals who previously tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 infection (RT-PCR test) at the outpatient testing center of the Geneva University Hospitals, Switzerland. The survey inquired about post-acute sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 and vaccination status. At the time of the study, the public health recommendations in Switzerland were for previously infected individuals to preferably receive one dose of vaccination only. Data was collected using REDCap v11.0.3 and analyzed using Stata, version 15.1 (StataCorp). The outcome of persistence of symptoms was defined as having any of the following: fatigue, difficulty concentrating or memory loss, loss of or change in smell, loss of or change in taste, shortness of breath, and headache. These six cardinal symptoms were chosen to characterize persistent symptoms post-SARS-CoV-2 based on previous studies.1,4

RESULTS

Overall, 2094 participants answered the survey (response rate 29.9%). Of symptomatic participants, n = 1596 reported their symptoms developed after SARS-CoV-2 infection and that their comorbidities, when applicable, pre-dated the infection (characteristics in Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of Participants (n = 1596)

| Age mean ± SD yr | 43.5 ± 13.7 |

|---|---|

| N (%) | |

| Age categories | |

| Below 40 yr | 704 (44.1) |

| 40–59 yr | 697 (43.7) |

| 60 yr and above | 195 (12.2) |

| Sex | |

| Female | 883 (55.3) |

| Male | 713 (44.7) |

| Time from infection to survey | |

| 3–6 months | 33 (2.1) |

| 6–9 months | 1140 (71.4) |

| 9–12 months | 184 (11.5) |

| More than 12 months | 239 (15.0) |

| Smoking status | |

| Never smoked | 874 (54.8) |

| Current smoker | 235 (14.7) |

| Ex-smoker | 450 (28.2) |

| Prefer not to answer | 37 (2.3) |

| Comorbidities | |

| None | 858 (53.8) |

| Overweight | 179 (11.2) |

| Sleeping disorder | 122 (7.6) |

| Hypertension | 111 (7.0) |

| Migraine | 106 (6.6) |

| Anxiety | 76 (4.8) |

| Other comorbidities | 63 (3.9) |

| Depression | 56 (3.5) |

| Other arthritis | 56 (3.5) |

| Irritable bowel syndrome | 54 (3.4) |

| Obesity | 49 (3.1) |

| Respiratory disease | 48 (3.0) |

| Tendinitis | 47 (2.9) |

| Tension headache | 44 (2.8) |

| Hypothyroidism | 39 (2.4) |

| Cardiovascular disease | 34 (2.1) |

| Anemia | 33 (2.1) |

| Attention deficit | 33 (2.1) |

| Diabetes | 29 (1.8) |

| Other digestive disorder | 27 (1.7) |

| Memory disorder | 26 (1.6) |

| Other types of headache | 24 (1.5) |

| Chronic fatigue | 24 (1.5) |

| Immunosuppression | 15 (0.9) |

| Dysmenorrhea | 14 (0.9) |

| Hyperthyroidism | 11 (0.7) |

| Chronic pain syndrome | 10 (0.6) |

| Other neurological disorder | 10 (0.6) |

| Rheumatoid arthritis | 10 (0.6) |

| HIV | 8 (0.5) |

| Thrombosis | 8 (0.5) |

| Multiple sclerosis | 6 (0.4) |

| Fibromyalgia | 5 (0.3) |

| Crohn’s disease | 5 (0.3) |

| Ulcerative colitis | 5 (0.3) |

| Ankylosing spondylitis | 5 (0.3) |

| Cancer | 3 (0.2) |

| Renal disease | 3 (0.2) |

| Other psychiatric disorders | 3 (0.2) |

| Lupus | 3 (0.2) |

| Reactive arthritis | 2 (0.1) |

| Sjogren disease | 1 (0.1) |

SD standard deviation, yr year

Proportions of vaccinated participants included in our study were 47.1% (26.6% one dose, 20.5% two doses), compared to 65.3% of 228 asymptomatic participants (17.5% one dose, 47.8% two doses), and 69.0% of eligible adults in the general population by the end of July 2021 (18.8% one dose, 50.2% two doses).

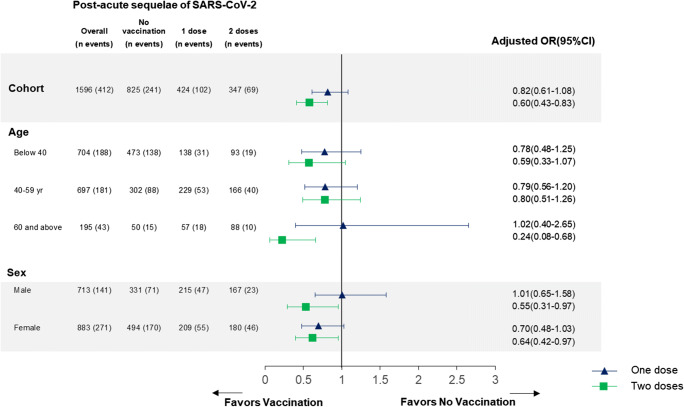

Following vaccination, symptoms disappeared (30.8%) or improved (4.7%) in 35.5% of cases, were stable in 28.7% of cases, and worsened in 3.3% of cases. Symptoms’ evolution was reported as other in 29.0% of cases and 2.6% preferred not to answer. Symptoms’ improvement or worsening occurred within 5 days post-vaccination in 69.6% and 82.3% of cases respectively. Vaccination (one or two doses) was associated with a decreased prevalence of the six cardinal post-SARS-CoV-2 symptoms (adjusted odds ratio, aOR 0.72; 0.56–0.92). Vaccination with 2 doses was associated with a decreased prevalence of dyspnea (aOR 0.34; 0.14–0.82) and change in taste (0.38; 0.18–0.83) as well as a decreased prevalence of any one symptom (aOR 0.60; 0.43–0.83) (details in Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Associations between vaccination and the post-acute sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 infection, stratified by age groups and sex (n = 1596). Post-acute sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 were defined as the presence of fatigue, difficulty concentrating or memory loss, loss of or change in smell, loss of or change in taste, shortness of breath, and headache. These six cardinal symptoms were chosen to characterize persistent symptoms in long-COVID patients based on previous studies on the prevalence of symptoms more than 6 months after an infection.1 Participants answering (“Prefer not to answer”) were not included in this analysis (n = 8). Participants reporting never having symptoms were not included in this analysis of post-acute sequelae of SARS-CoV-2. Participants received the COVID-19 vaccine (mRNA-1273) of Moderna in 60.7% of cases, and the Comirnaty® (BNT162b2) vaccine of Pfizer/BioNTech in 38.5% of cases. Participants answered the survey on average 250.3 ± 72.1 days from their infection (257.8 ± 70.9 days for vaccinated versus 243.2 ± 72.5 days for non-vaccinated) and on average 40.3 ± 29.2 days after vaccination (range from 0 to 183 days, median 37 days, IQR 19–57). OR: odds ratios; CI: confidence interval. Odds ratios were adjusted for time for infection, age, sex, smoking, and the following comorbidities present prior to the infection: overweight or obese, hypertension, respiratory disease, cardiovascular disease, diabetes, migraine, tension headache, sleeping disorder, anxiety, depression, hypothyroidism, anemia, and chronic fatigue.

DISCUSSION

Vaccination was associated with a decreased prevalence of post-acute sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 infection compared to no vaccination. A recent study2 had shown similar results on a smaller scale (n = 36), and a pre-print with 900 participants3 showed improvement in 56.7% of cases post-vaccination, versus worsening (18.7%) and stability (24.6%). Another pre-print with 545 infected individuals showed that vaccination lowered symptom severity at 120 days.5 Postulated hypotheses include the potential correction of dysregulated immune or inflammatory responses, or the possible elimination of persisting viruses or viral remnants of SARS-CoV-2.6

Our study includes several limitations. It is challenging to attribute symptom improvement to vaccination versus other concomitant factors, with a potential indication bias if more symptomatic individuals preferred to withhold vaccination. To mitigate this potential bias, we adjusted for comorbidities and included only individuals with new symptoms post-infection. Also, while we cannot formally exclude indication bias, and specific new symptoms post-vaccination, we found no association between having symptoms prior to vaccination (at the time of testing) and vaccination rates. This suggests that more symptomatic participants were not more likely to get vaccinated (data not shown). Vaccinated participants also had a slightly longer time interval between the infection and the survey (14 days on average), mitigated by adjusting for time from infection. Finally, while our study is to date one of the largest, it lacked power for some stratified analyses, such as the impact of one vaccination dose. While acknowledging these limitations, we believe that the strength of the association, as well as a dose-response effect, could support a causal association, in addition to possible biological rationales evoked recently.6 If confirmed, this would mean that vaccination not only prevents infection but also can potentially improve post-acute sequelae of SARS-CoV-2.

Acknowledgements

We thank all co-investigators who participated in this study, Pr. Francois Chappuis, Pr. Laurent Kaiser, and the CoviCare Study Team for their ongoing support in the research on post-acute sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 in Geneva, Switzerland.

Author Contribution

MN, IG, HS, JS, FJ, OB, and DC contributed to the collection of the data. MN and IG contributed to the analysis of the data. MN and IG contributed to the drafting of the manuscript. All of the authors reviewed and approved the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the private research funds of the Division of Primary Care Medicine at the Geneva University Hospitals.

Declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they do not have a conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

We confirm that the manuscript has been read and approved by all named authors and that there are no other persons who satisfied the criteria for authorship but are not listed.

We further confirm that any aspect of the work covered in this manuscript that has involved human patients has been conducted with the ethical approval of the Cantonal Research Ethics Commission of Geneva, Switzerland, and that such approvals are acknowledged within the manuscript.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Nehme M, Braillard O, Chappuis F, Courvoisier DS, Guessous I. Prevalence of Symptoms More Than Seven Months After Diagnosis of Symptomatic COVID-19 in an Outpatient Setting. Ann Intern Med. 2021. doi: 10.7326/M21-0878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 2.Arnold DT, Milne A, Samms E, Stadon L, Maskell NA, Hamilton FW. Symptoms After COVID-19 Vaccination in Patients With Persistent Symptoms After Acute Infection: A Case Series. Ann Intern Med. 2021:M21-1976. 10.7326/M21-1976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 3.LongCovidSOS, The impact of COVID vaccination on symptoms of Long Covid. An international survey of 900 people with lived experience https://3ca26cd7-266e-4609-b25f-6f3d1497c4cf.filesusr.com/ugd/8bd4fe_a338597f76bf4279a851a7a4cb0e0a74.pdf. Accessed July 18, 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 4.Blomberg B, Mohn KG, Brokstad KA, Zhou F, Linchausen DW, Hansen BA, Lartey S, Onyango TB, Kuwelker K, Sævik M, Bartsch H, Tøndel C, Kittang BR; Bergen COVID-19 Research Group, Cox RJ, Langeland N. Long COVID in a prospective cohort of home-isolated patients. Nat Med. 2021. 10.1038/s41591-021-01433-3.

- 5.Tran VT, Perrodeau E, Saldanha J, Pane I, Ravaud P. Efficacy of COVID-19 Vaccination on the Symptoms of Patients With Long COVID: A Target Trial Emulation Using Data From the ComPaRe e-Cohort in France. Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3932953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 6.Marshall M. The four most urgent questions about long COVID. Nature. 2021;594(7862):168–170. doi: 10.1038/d41586-021-01511-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]