Abstract

We genetically characterized multidrug-resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex strains which caused a nosocomial outbreak of tuberculosis affecting six human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-positive patients and one HIV-negative staff member (E. Bouvet, E. Casalino, G. Mendoza-Sassi, S. Lariven, E. Vallée, M. Pernet, S. Gottot, and F. Vachon, AIDS 7:1453–1460, 1993). The strains showed all the phenotypic characteristics of Mycobacterium bovis. They presented a high copy number of IS6110, the spacers 40 to 43 in the direct repeat locus, and the mtp40 fragment. They lacked the G-A mutation at position 285 in the oxyR gene and the C-G mutation at position 169 in the pncA gene. These genetic characteristics revealed that these were dysgonic, slow-growing M. tuberculosis strains mimicking the M. bovis phenotype, probably as a consequence of cellular alterations associated with the multidrug resistance. Spoligotyping and IS6110 restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) analysis confirmed that the outbreak was due to a single strain. However, the IS6110 RFLP pattern of the strain isolated from the last patient, diagnosed three years after the index case, differed slightly from the patterns of the other six strains. A model of a possible genetic event is presented to explain this divergence. This study stresses the value of using several independent molecular markers to identify multidrug-resistant tubercle bacilli.

Multidrug-resistant (MDR) tuberculosis is an increasingly significant cause of morbidity and mortality worldwide. There have been several outbreaks in the last decade in institutions (hospitals, prisons, and homeless shelters) in the United States, Europe, and Latin America (1, 22, 23). Outbreaks are more common among immunosuppressed patients, especially human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-positive patients, and are characterized by a high fatality rate (17). However, immunocompetent people, including other patients in the same institution, family members, and healthworkers, are also involved during outbreaks. Recently, an outbreak has been described in a hospital nursery, affecting several infants and a woman who had given birth there (16).

The strains involved in most of these outbreaks have been identified as Mycobacterium tuberculosis, the main agent of human tuberculosis worldwide. Tuberculous disease due to MDR Mycobacterium bovis is rare. However, coinfection with HIV favors M. bovis transmission among patients, leading rapidly to disease (9). Along with resurgent M. tuberculosis and the increase of MDR tuberculosis outbreaks, there is a growing number of cases of invasive disease due to M. bovis strains in immunocompromised patients. Nosocomial transmission of MDR M. bovis has been reported in Spain and Italy (2, 8), including transmission between immunocompetent patients (11, 19). Sporadic community cases in immunocompetent patients have also been reported (25). Many of these cases have not been rigorously documented at the molecular genetic level.

M. tuberculosis and M. bovis have different host ranges (34). M. tuberculosis causes disease almost exclusively in humans and rarely in other animals, whereas M. bovis can cause tuberculosis in a wide range of animal hosts, including humans (36). Distinguishing between these two members of the M. tuberculosis complex is therefore essential for epidemiological investigations of cases and for identifying potential animal reservoirs that may be a risk to public health. The clinical, radiological, and anatomopathological findings in tuberculous patients are identical whatever the organism involved, and consequently differentiation is only possible by using bacteriological methods. Classical methods are based on the analysis of phenotypic characteristics such as colony morphology, growth rate, and biochemical properties (18). Modifications of these characteristics have been described for antimicrobial-resistant strains (28, 37).

Genetic systems like Gen-Probe Mycobacterium TB complex (Gen-Probe, Inc., San Diego, Calif.) detect the 16S rRNA of tubercle bacilli, allowing their rapid identification. However, these sequences are identical for all the members of the M. tuberculosis complex (14), and a battery of classical biochemical tests must be performed to provide a final identification. The search for genetic markers in M. tuberculosis has led to the identification of repeated sequences (21): IS6110, DR (direct repeats), IS1081, MPTR (major polymorphic tandem repeats), PGRS (polymorphic G+C-rich sequence), and MIRU (mycobacterial interspersed repetitive unit). Their distribution in the genome may be useful to determine the epidemiological relatedness of strains and to trace the sources of infection (30). However, all these markers are present in all tubercle bacilli and cannot be used to differentiate between the members of the complex. It has been claimed that other genetic markers are specific to M. tuberculosis or M. bovis. Most M. bovis strains lack the mtp40 sequence found in M. tuberculosis (33) and carry a particular mutation at position 169 in the pncA gene conferring pyrazinamide (PZA) resistance (24). A specific mutation at position 285 in the oxyR gene (26) and the absence of the five 3′ spacers (spacers 39 to 43) in the DR locus (13) have been also described as characteristic for M. bovis.

Between 1989 and 1991, a nosocomial outbreak of MDR tuberculosis occurred in an infectious disease unit in Paris. Six HIV-positive people were affected. A later case diagnosed in 1992 in an immunocompetent member of the staff was related to this outbreak. All cases involved strains with an M. bovis phenotype. This was the first outbreak reported as involving MDR M. bovis (3). A reinvestigation based on molecular markers suggested that the clinical isolates were unusual strains of M. tuberculosis (12). We report a more extensive molecular analysis of these isolates and (i) confirm the M. tuberculosis identification, (ii) stress the value of using several independent molecular markers to identify dysgonic MDR tubercle bacilli, and (iii) confirm at the molecular level that all seven cases were related and were thus a single outbreak.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mycobacterial strains and phenotypic characteristics.

Between September 1989 and January 1992, seven mycobacterial strains presenting the same microbiological characteristics were isolated from six HIV-positive patients and one medical staff member in a hospital in Paris (3). The isolates grew as smooth, transparent, dysgonic colonies on Löwenstein-Jensen medium within 6 to 8 weeks. They were negative for niacin and nitratase production, their growth was inhibited by thiophene-2-carboxylic acid hydrazide (TCH) and stimulated by pyruvate, and they were resistant to PZA. Drug susceptibility patterns, determined by the proportion method described by Canetti et al. (4), on Löwenstein-Jensen medium showed resistance to isoniazide, rifampin, ethambutol, streptomycin, ethionamide, and rifabutin.

Genotypic characterization.

The isolates were genotypically identified as M. tuberculosis complex strains with a nucleic acid probe recognizing the species-specific 16S rRNA (Gen-Probe Mycobacterium TB complex).

(i) Detection of the mtp40 sequence.

The primers for the mtp40 sequence were PT1 (5′-CAACGCGCCGTCGGTGG-3′) and PT2 (5′-CCCCCCACGGCACCGC-3′), which amplify a 396-bp fragment (7). The amplification mixtures contained 10 μl of template DNA and 40 μl of a reaction mixture, such that the final concentrations were as follows: 200 μM concentrations of each deoxynucleoside triphosphate, 0.5 μM concentrations of each primer, 1.0 U of AmpliTaq DNA polymerase (Perkin-Elmer), 10 mM Tris hydrochloride (pH 8.3), 50 mM KCl, 0.01% gelatin, 0.5 mM MgCl2, and 10% dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO). After an initial denaturation of 10 min at 94°C the reaction mixtures were amplified by 35 cycles of denaturation at 94°C for 30 s, annealing at 65°C for 2 min, extension at 72°C for 3 min, and a final extension at 72°C for 10 min.

(ii) PCR amplification of the pncA sequence.

The primers used were the forward primer pncATB-1.2 (5′-ATGCGGGCGTTGATCATCGTC-3′) and the reverse primers pncAMT-2 (5′-CGGTGTGCCGGAGAAGCGG-3′) and pncAMB-2 (5′-CGGTGTGCCGGAGAAGCCG-3′), which amplify a 185-bp fragment (7). The amplifications were carried out in a total volume of 25 μl containing 200 μM concentrations of each deoxynucleoside triphosphate, 1 μM concentrations of each primer, 1.0 U of Taq Gold DNA polymerase (Perkin-Elmer), 10 mM Tris hydrochloride (pH 8.3), 50 mM KCl, 2 mM MgCl2, 0.01% gelatin, 10% DMSO, and 5 μl of template DNA. The cycle conditions were as previously described (7).

(iii) PCR amplification of the oxyR sequence.

The forward primer was oxyRTB-2.1 (5′-TGGCCGGGCTTCGCGCGT-3′) and the reverse primers were oxyRMT-1 (5′-GCACGACGGTGGCCAGGCA-3′) and oxyRMB-1 (5′-TGCACGACGGTGGCCAGGTA-3′), which amplify a 270-bp fragment (7). The amplification mixtures were as described above for the pncA sequence. The cycle conditions were as previously described (7).

The amplifications were carried out in a thermal cycler (Progene, Techne LTD). Aliquots of 10 μl of each reaction mixture were electrophoresed in 2% agarose gels in Tris-borate-EDTA buffer. The amplified products were visualized by UV transillumination.

(iv) Molecular typing of the strains by IS6110 restriction length fragment polymorphism (RFLP) analysis.

Mycobacterial chromosomal DNA was extracted, and Southern blotting was performed by a previously described standardized method (29). The membranes were probed with either an 857-bp fragment specific for the 3′ end of IS6110 (right probe) or a 482-bp fragment specific for the 5′ end of IS6110 (left probe). Right and left probes were obtained by PCR amplification of the entire IS6110 (27). For this, the IS6110s were amplified from the DNA of strain Mt14323 with a single primer corresponding to the invert repeat sequence (5′-CCCGGCATGTCCGGAGACTC-3′). The reaction mixture was as follows: 200 μM concentrations of each deoxynucleoside triphosphate, a 0.4 μM concentration of primer, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 10 mM Tris hydrochloride (pH 8.3), 50 mM KCl, 0.01% gelatin, 10% DMSO, 1.0 U of AmpliTaq DNA polymerase (Pharmacia), and 5 μl of template DNA in a total volume of 50 μl. The conditions for amplification were 9 min at 95°C, followed by 30 cycles of denaturation at 95°C for 1 min, annealing at 55°C for 2 min, and extension at 72°C for 3 min, and a final extension at 72°C for 10 min. The amplicon was digested with PvuII, and the two fragments used as probes were separated by electrophoresis and purified with a Nucleotrap extraction kit (Macheray-Nagel). The probes were labeled and detected with an enhanced chemiluminescence kit (ECL; Amersham International).

(v) Characterization of the DR region by spoligotyping.

The DR cluster DNA of the strains was amplified by PCR. The labeled PCR product was used as a probe to hybridize with 43 synthetic spacer oligonucleotides attached to a carrier membrane (Isogen Bioscience B.V.), as described previously (13).

RESULTS

Table 1 summarizes the phenotypic and genotypic characteristics of the MDR strains studied.

TABLE 1.

Usual characteristics of M. tuberculosis and M. bovis and features of the MDR strains studied

| Characteristica | Result for:

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| M. tuberculosis | MDR strains in this study | M. bovis | |

| Phenotype | |||

| Colony | Eugonic | Dysgonic | Dysgonic |

| Niacin | + | − | − |

| Nitrate reductase | + | − | − |

| TCH | Resistant | Sensitive | Sensitive |

| PZA | Sensitive | Resistant | Resistant |

| Pyrazinamidase | + | NDb | − |

| Genotype | |||

| mtp40 | Present | Present | Absent |

| pncA nucleotide 169 | Cytosine | Cytosine | Guanine |

| oxyR nucleotide 285 | Guanine | Guanine | Adenine |

| IS6110 | Numerous copies | 11 copies | Few copies |

| DR spacers 39–43 | Present | Present (40–43) | Absent |

Niacin, nitrate reductase, and pyrazinamidase refer to the niacin detection, nitrate reductase, and pyrazinamidase biochemical tests, respectively; TCH, growth in the presence of TCH; PZA, growth in the presence of PZA; the genotypic features are detailed in the text.

ND, not determined.

PCR analysis of the mpt40 sequence and the allele-specific polymorphisms.

The PCR amplifications with specific primers showed that all seven strains (i) contained the mtp40 sequence, (ii) did not contain the pncA allele-specific polymorphism at position 169 typically present in M. bovis strains isolated from humans, and (iii) did not contain the oxyR allele-specific polymorphism at position 285 typically present in M. bovis strains.

IS6110 RFLP fingerprinting.

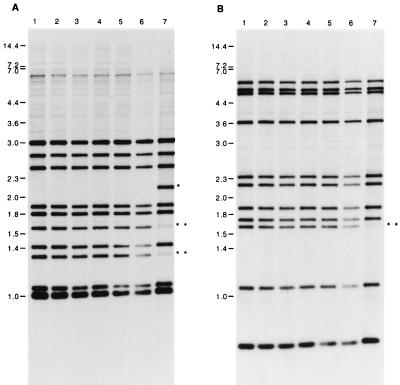

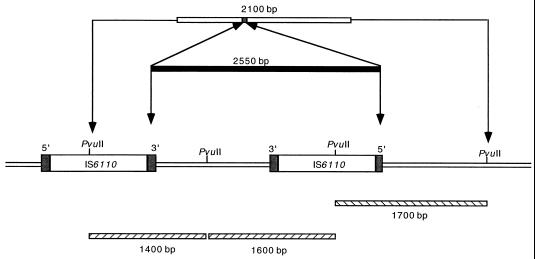

Standard IS6110 RFLP analysis with the right (Fig. 1A) and left (Fig. 1B) probes showed the presence of 11 IS6110 copies in the genomes of six strains. These six strains all gave an identical hybridization pattern (strains 1 to 6). One strain (strain 7) presented one additional band when probed with the right probe (Fig. 1A, line 7) but not when probed with the left probe (Fig. 1B, line 7). This strain was from the staff member and had been isolated 3 years after the diagnosis of the index case (strain 1). Three bands in the IS6110 RFLP pattern of strain 7 were less intense than the corresponding bands of the other six strains (two when probed with the right probe and one when probed with the left probe). This RFLP pattern suggests a mixed population composed of a clone identical to the other six strains of the cluster and one different clone. The absence of an additional band with the left probe suggests that this polymorphism was due not to an additional copy of the IS6110 sequence but to a deletion of a 2,550-bp fragment comprising a copy of IS6110 as shown in Fig. 2. A homologous recombination between the invert repeat sequences of two adjacent IS6110s could be the origin of this deletion.

FIG. 1.

IS6110 RFLP of the seven strains isolated during the nosocomial outbreak. Southern blots of PvuII-digested genomic DNAs were hybridized with a probe specific for either the 3′-end IS6110 (A) or the 5′-end IS6110 (B). The sizes are indicated in kilobase pairs. ∗, the additional band for strain 7. ∗∗, bands of lower intensity for strain 7.

FIG. 2.

Schematic representation of a possible genetic event in strain 7, which explains the different RFLP profiles observed in Fig. 1. The loss of one fragment of DNA (2,550 bp) containing an IS6110 copy from the chromosome of strain 7 results in an additional band (2,100 bp) in the RFLP profile observed with the probe specific for the 3′-end IS6110. The right IS6110 copy is inverted. Fragments of PvuII-digested DNA, resulting in weak bands when probed with the 3′-end (1,400- and 1,600-bp fragments) or 5′-end (1,700-bp fragment) IS6110, are shown. Inverted repeated sequences are shown as shaded boxes on either side of the insertion sequences.

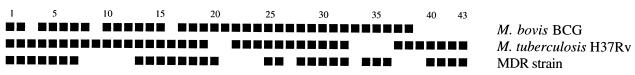

Spoligotyping.

The strains were studied by spoligotyping, a novel method that tests for the presence of 43 short spacer DNA sequences in the polymorphic DR locus of M. tuberculosis complex bacteria. All seven strains generated identical spoligotyping patterns (Fig. 3). Moreover, they presented spacers 40 to 43, which have not been found in any M. bovis strain studied by spoligotyping.

FIG. 3.

Schematic representation of the spoligotyping pattern of the MDR strains. The PCR products of the MDR strains, M. bovis BCG, and M. tuberculosis H37Rv were hybridized to 43 spacer sequences which are found in the DR region. The black squares represent positive hybridization signals with the spacers, and the blank spaces represent lack of hybridization, indicative of the absence of the particular spacer within the amplified DNA. The numbers on the top are the numbers of the spacer sequences. All seven MDR strains shared the same spacers, and the pattern is represented once.

DISCUSSION

M. tuberculosis complex isolates may be classified according to their phenotype as strains that completely fulfill the criteria for M. tuberculosis or M. bovis. For such strains no further characterization is usually performed. We believe that this is the first description of M. tuberculosis complex strains that show all the phenotypic characteristics of M. bovis but which have a genotype more closely related to M. tuberculosis. These strains were the etiological agent of a nosocomial outbreak of MDR tuberculosis involving seven patients, one of whom was an HIV-negative staff member.

The phenotypic criteria used for the specific identification of M. bovis include dysgonic growth, negative results in tests for niacin and nitratase production, PZA resistance, and growth inhibition by TCH and stimulation by pyruvate (Table 1). Dysgonic human strains and eugonic bovine strains were described by Griffith as early as 1941 (10). For M. tuberculosis H37Rv and M. bovis BCG, differences in colony morphotypes have been described and are associated with differences in virulence, but the biochemical and genetic bases for these differences are unknown (32). Both slower growth and negative biochemical test results have been described as being associated with antimicrobial resistance in mycobacteria. Isoniazid-resistant M. tuberculosis strains have been reported to grow more slowly than susceptible strains (37), and it has been shown that PZA resistance was associated with niacin-negative reactions (24). In M. tuberculosis, antimicrobial resistance is usually due to simple nucleotide substitutions (15). The most likely mechanism of emergence of MDR strains is the sequential acquisition of single drug resistances by independent mutations. These mutations might have various and different consequences on the physiologies of the resulting resistant strains (39).

In these dysgonic MDR strains we found the mtp40 fragment, a high copy number of IS6110, and the spacers 40 to 43 in the DR locus. They did not carry the M. bovis-specific polymorphism in the oxyR gene or the C-G mutation at position 169 in the pncA gene. These features identify the strains as M. tuberculosis (Table 1). Their M. bovis phenotype could be a consequence of the mutations leading to MDR, because these mutations may alter molecular targets essential for bacterial metabolism, such as genes involved in protection against oxidative products, RNA polymerase, and ribosomes, the targets of isoniazid, rifampin, and streptomycin, respectively.

The pncA gene, encoding pyrazinamidase, was initially reported to present a sequence polymorphism at nucleotide 169, the base at this position being specific for each species. M. bovis strains have a single C-G point mutation, resulting in an H57D substitution that is the molecular basis for PZA resistance (24). Strains initially identified as M. bovis that did not contain the characteristic pncA mutation have been occasionally reported. Scorpio and Zhang (24) found that these rare strains are susceptible to PZA and produced pyrazinamidase and reclassified them as Mycobacterium africanum. Other studies found that M. bovis strains isolated from goats similarly did not carry this mutation (7). M. bovis isolates from goats cluster in distinct spoligotyping groups, very different from those including other M. bovis and M. tuberculosis strains, and show a mixed phenotype according to the classic biochemical markers. Our MDR strains were resistant to PZA, and they did not present the M. bovis C-G point mutation in the pncA gene. Single PZA resistance is an excellent M. bovis marker and may be used to identify strains susceptible to other antituberculous drugs. However, this identification marker can no longer be considered valid for MDR strains.

oxyR in M. tuberculosis is a pseudogene, a homolog of the oxyR gene in Escherichia coli involved in the expression control of genes encoding detoxifying enzymes. It presents a polymorphic nucleotide located at position 285 that differentiates M. bovis from other complex members (26). According to previously reported data (7), the oxyR mutation is a more reliable marker than the pncA mutation for distinguishing between M. bovis and M. tuberculosis.

The mtp40 fragment, part of a sequence coding for a hemolytic phospholipase, was first reported to be present only in M. tuberculosis strains. Exceptions were described for MDR M. tuberculosis lacking this sequence and for two M. bovis strains that presented this sequence (35). However, its presence in M. bovis remains controversial, because a large number of M. bovis strains have been observed to be negative for mtp40 and the only two strains reported as positive, by PCR, have not been characterized further (33).

The strains of this outbreak showed a high-copy-number IS6110 RFLP profile. The copy number of IS6110 alone has been suggested as a marker that can be used to differentiate M. tuberculosis from M. bovis: most M. tuberculosis strains have multiple copies, whereas M. bovis strains have only one or two. However, exceptions are encountered. Thus, some M. tuberculosis strains have few copies, and some, especially those isolated in East Asia, have none (38). Moreover, studies of large collections of M. bovis strains revealed strains with a high IS6110 copy number (31), and nowadays the copy number alone is not considered sufficient for differentiation.

The most recently isolated strain of this study (strain 7) showed a one-band difference in its IS6110 RFLP pattern. Despite this difference, the seven strains can be assumed to be of common origin, as epidemiologically related strains have been shown to differ from one another in the size or presence of one or two IS6110 sequences that make up the fingerprint (5). These changes may be due to the potential capacity for transposition, duplication, and excision within the genome of the mobile element IS6110 (27) or to mutations altering the position of the PvuII restriction site in its flanking genomic sequence, as has been shown for the MDR strain W of M. tuberculosis (20). Our results suggest that the genetic event in MDR strain 7 could be a homologous recombination between inverted repeat sequences, leading to the loss of an IS6110 copy.

The identification and common origin of the strains were also supported by the results from spoligotyping. Spoligotyping is nowadays considered a confirmatory genetic means for the differentiation of M. bovis and M. tuberculosis (11, 13), and it is particularly useful for resistant strains with atypical biochemical identification test results (19). M. bovis strains lacked the characteristic spacers 39 to 43 in the DR locus. The strains of the outbreak analyzed here presented the spacers 40 to 43, a definitive demonstration of its initial phenotypic misidentification. Although this PCR-based method is less discriminating than RFLP in differentiating strains carrying more than five copies of IS6110 (13), it relies on a genetic marker unrelated to IS6110, and the two strategies provide independent molecular evidence of strain relationship.

The increasing frequency of reports of outbreaks of tuberculosis due to MDR strains, including the recent outbreaks due to MDR M. bovis strains in Spain and Italy (8, 11), and our results with a dysgonic MDR strain of M. tuberculosis mimicking the M. bovis phenotype emphasize the value of using molecular methods for the differentiation of members of the M. tuberculosis complex. The exceptions encountered in differentiating tubercle bacilli according to each marker separately indicate that several, independent molecular markers are required for the accurate differentiation of M. tuberculosis from M. bovis.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Carlos Martín for ideas and interest and Stefano Bonora for a critical reading of the manuscript.

M. C. Gutiérrez was the recipient of a postdoctoral fellowship from the Spanish Ministry of Education and Culture. J. C. Galán was the recipient of an F.I.S.S. fellowship (BEFI 98/9060).

REFERENCES

- 1.Bifani P J, Plikaytis B B, Kapur V, Stockbauer K, Pan X, Lutfey M L, Moghazeh S L, Eisner W, Daniel T M, Kaplan M H, Crawford J T, Musser J M, Kreiswirth B N. Origin and interstate spread of a New York City multidrug-resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis clone family. JAMA. 1996;275:452–457. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blázquez J, Espinosa de los Monteros L E, Samper S, Martín C, Guerrero A, Covo J, van Embden J, Baquero F, Gómez-Mampaso E. Genetic characterization of multidrug-resistant Mycobacterium bovis strains from a hospital outbreak involving human immunodeficiency virus-positive patients. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:1390–1393. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.6.1390-1393.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bouvet E, Casalino E, Mendoza-Sassi G, Lariven S, Vallée E, Pernet M, Gottot S, Vachon F. A nosocomial outbreak of multi-drug resistant Mycobacterium bovis among HIV-infected patients. A case-control study. AIDS. 1993;7:1453–1460. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199311000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Canetti G, Rist N, Grosset J. Mesure de la sensibilité du bacille tuberculeux aux drogues antibacillaires pour la méthode des proportions. Rev Tuberc Pneumol. 1963;27:263–272. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cave M C, Eisenach K D, Templeton G, Salfinger M, Mazurek G, Bates J H, Crawford J T. Stability of DNA fingerprint pattern produced with IS6110 in strains of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J Clin Microbiol. 1994;32:262–266. doi: 10.1128/jcm.32.1.262-266.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.del Portillo P, Murillo L A, Patarroyo M E. Amplification of a species-specific DNA fragment of Mycobacterium tuberculosis and its possible use in diagnosis. J Clin Microbiol. 1991;29:2163–2168. doi: 10.1128/jcm.29.10.2163-2168.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Espinosa de los Monteros L E, Galán C, Gutiérrez M, Samper S, García Marín J F, Martín C, Domínguez L, de Rafael L, Baquero F, Gómez-Mampaso E, Blázquez J. Allele-specific PCR method based on pncA and oxyR sequences for distinguishing Mycobacterium bovis from Mycobacterium tuberculosis: intraspecific M. bovis pncA sequence polymorphism. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:239–242. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.1.239-242.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gori A, Marchetti G, Catozzi L, Nigro C, Ferrario G, Rossi M C, Degli Esposti A, Orani A, Franzetti F. Molecular epidemiology characterization of a multidrug-resistant Mycobacterium bovis outbreak amongst HIV-positive patients. AIDS. 1998;12:445–446. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Grange J M, Daborn C, Cosivi O. HIV-related tuberculosis due to Mycobacterium bovis. Eur Respir J. 1994;7:1564–1566. doi: 10.1183/09031936.94.07091564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Griffith A S. The problem of the virulence of the tubercle bacillus. Tubercle. 1941;22:33–39. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Guerrero A, Cobo J, Fortún J, Navas E, Quereda C, Asensio A, Cañón J, Blázquez J, Gómez-Mampaso E. Nosocomial transmission of Mycobacterium bovis resistant to 11 drugs in people with advanced HIV-1 infection. Lancet. 1997;350:1738–1742. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(97)07567-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gutiérrez M C, Bouvet E, Blázquez J, Vincent V. Identification as Mycobacterium tuberculosis of previously described M. bovis multidrug-resistant strains. Lancet. 1998;351:758. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(05)78537-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kamerbeek J, Schouls L, Kolk A, van Agterveld M, van Soolingen D, Kuijper S, Bunschoten A, Molhuizen H, Shaw R, Goyal M, van Embden J. Simultaneous detection and strain differentiation of Mycobacterium tuberculosis for diagnosis and epidemiology. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:907–914. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.4.907-914.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kirschner P, Springer B, Vogel U, Meier A, Wrede A, Kiekenbeck M, Bange F-C, Böttger E C. Genotypic identification of mycobacteria by nucleic acid sequence determination: report of a 2-year experience in a clinical laboratory. J Clin Microbiol. 1993;31:2882–2889. doi: 10.1128/jcm.31.11.2882-2889.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Musser J M. Antimicrobial agent resistance in Mycobacteria: molecular genetic insights. Clin Infect Dis. 1995;8:496–514. doi: 10.1128/cmr.8.4.496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nivin B, Nicholas P, Gayer M, Frieden T R, Fujiwara P I. A continuing outbreak of multidrug-resistant tuberculosis, with transmission in a hospital nursery. Clin Infect Dis. 1998;26:303–307. doi: 10.1086/516296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nolan C M. Nosocomial multidrug-resistant tuberculosis. Global spread of the third epidemic. J Infect Dis. 1997;176:748–751. doi: 10.1086/514099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nolte F S, Metchock B. Mycobacterium. In: Murray P R, Baron E J, Pfaller M A, Tenover F C, Yolken R H, editors. Manual of clinical microbiology. 6th ed. Washington, D.C: American Society for Microbiology; 1995. pp. 400–437. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Palenque E, Villena V, Rebollo M J, Jiménez M S, Samper S. Transmission of multidrug-resistant Mycobacterium bovis to an immunocompetent patient. Clin Infect Dis. 1998;26:995–996. doi: 10.1086/517645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Plikaytis B B, Marden J L, Crawford J T, Woodley C L, Butler W R, Shinnick T M. Multiplex PCR assay specific for the multidrug-resistant strain W of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J Clin Microbiol. 1994;32:1542–1546. doi: 10.1128/jcm.32.6.1542-1546.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Poulet S, Cole S T. Repeated sequences in mycobacteria. Arch Microbiol. 1995;163:79–86. doi: 10.1007/BF00381780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ritacco V, di Lonardo M, Reniero A, Ambroggi M, Barrera L, Dambrosi A, Lopez B, Isola N, de Kantor I N. Nosocomial spread of human immunodeficiency virus-related multidrug-resistant tuberculosis in Buenos Aires. J Infect Dis. 1997;176:637–642. doi: 10.1086/514084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rullán J V, Herrera D, Cano R, Moreno V, Godoy P, Peiro E F, Castell J, Ibáñez C, Ortega A, Sánchez Agudi L, Pozo F. Nosocomial transmission of multidrug-resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis in Spain. Emerg Infect Dis. 1996;2:125–129. doi: 10.3201/eid0202.960208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Scorpio A, Zhang Y. Mutations in pncA, a gene encoding pyrazinamidase/nicotinamidase, cause resistance to the antituberculous drug pyrazinamide in tubercle bacillus. Nat Med. 1996;2:662–667. doi: 10.1038/nm0696-662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Signorini L, Matteelli A, Bombana E, Pinsi G, Gulletta M, Tebaldi A, Carosi G. Tuberculosis due to drug-resistant Mycobacterium bovis in pregnancy. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 1998;2:342–343. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sreevatsan S, Escalante P, Pan X, Gillies II D A, Siddiqui S, Khalaf C N, Kreiswirth B N, Bifani P, Adams L G, Ficht T, Perumaalla V S, Cave M D, van Embden J D A, Musser J M. Identification of a polymorphic nucleotide in oxyR specific for Mycobacterium bovis. J Clin Microbiol. 1996;34:2007–2010. doi: 10.1128/jcm.34.8.2007-2010.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Thierry D, Cave M D, Eisenach K D, Crawford J T, Bates J H, Gicquel B, Guesdon J L. IS6110, an IS-like element of Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex. Nucleic Acids Res. 1990;18:188. doi: 10.1093/nar/18.1.188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tsukamura M. Niacin-negative Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1974;110:101–103. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1974.110.1.101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.van Embden J D A, Cave M D, Crawford J T, Dale J W, Eisenach K D, Gicquel B, Hermans P, Martín C, McAdam R, Shinnick T M, Small P M. Strain identification of Mycobacterium tuberculosis by DNA fingerprinting: recommendations for a standardized methodology. J Clin Microbiol. 1993;31:406–409. doi: 10.1128/jcm.31.2.406-409.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.van Soolingen D, de Haas P E W, Hermans P W M, Groenen P M A, van Embden J D A. Comparison of various repetitive DNA elements as genetic markers for strain differentiation and epidemiology of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J Clin Microbiol. 1993;31:1987–1995. doi: 10.1128/jcm.31.8.1987-1995.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.van Soolingen D, de Haas P E W, Haagsma J, Eger T, Hermans P W M, Ritacco V, Alito A, van Embden J D A. Use of various genetic markers in differentiation of Mycobacterium bovis strains from animals and humans and for studying epidemiology of bovine tuberculosis. J Clin Microbiol. 1994;32:2425–2433. doi: 10.1128/jcm.32.10.2425-2433.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.van Soolingen D, Hoogenboezem T, de Haas P E W, Hermans P W M, Koedam M A, Teppema K S, Brennan P J, Besra G S, Portaels F, Top J, Schouls L M, van Embden J D A. A novel pathogenic taxon of the Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex, Canetti: characterization of an exceptional isolate from Africa. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1997;47:1236–1245. doi: 10.1099/00207713-47-4-1236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vera-Cabrera L, Howard S T, Laszlo A, Johnson W M. Analysis of genetic polymorphism in the phospholipase region of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:1190–1195. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.5.1190-1195.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wayne L, Kubica G P. The mycobacteria. In: Sneath P H A, Holt J G, editors. Bergey’s manual of systematic bacteriology. Vol. 2. Baltimore, Md: The Williams & Wilkins Co.; 1986. pp. 1435–1457. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Weil A, Plikaytis B B, Butler W R, Woodley C L, Shinnick T M. The mtp40 gene is not present in all strains of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J Clin Microbiol. 1996;34:2309–2311. doi: 10.1128/jcm.34.9.2309-2311.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.World Health Organization. Zoonotic tuberculosis (Mycobacterium bovis): memorandum from a WHO meeting. Bull W H O. 1994;72:851–857. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Youatt J. A review of the action of isoniazid. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1969;99:729–747. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1969.99.5.729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yuen L K W, Ross B C, Jackson K M, Dwyer B. Characterization of Mycobacterium tuberculosis strains from Vietnamese patients by Southern blot hybridization. J Clin Microbiol. 1993;31:1615–1618. doi: 10.1128/jcm.31.6.1615-1618.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhang Y, Young D. Molecular genetics of drug resistance in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1994;34:313–319. doi: 10.1093/jac/34.3.313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]