Abstract

Purpose:

Racial/ethnic breast cancer survivorship disparities persist as minority breast cancer survivors (MBCSs) report fragmentation in survivorship care, namely in the access and delivery of survivorship care plans (SCPs). To better understand care coordination of MCBS, this review elucidated concerns of female MBCS about their preparation for post-treatment survivorship care, the preferred practices for the delivery of a SCP, and the associated content to improve post-treatment survivorship care understanding.

Methods:

A systematic search of articles from PubMed, Ovid-Medline, CINAHL databases, and bibliographic reviews included manuscripts using keywords for racial/ethnic minority groups and breast cancer survivorship care coordination terms. Salient themes and article quality were analyzed from the extracted data.

Results:

Fourteen included studies represented 5,854 participants and over 12 racial/ethnic groups. The following themes of post-treatment MBCS were identified from the review: (1) uncertainty about post-treatment survivorship care management is a consequence of sub-optimal patient-provider communication; (2) access to SCPs and related materials are desired, but sporadic; and (3) advancements to the delivery and presentation of SCPs and related materials are desired.

Conclusions:

Representation of only 14 studies indicates that the MBCSs’ perspective post-treatment survivorship care is underrepresented in the literature. Themes from this review support access to, and implementation of, culturally tailored SCP for MBCS. There was multi-ethnic acceptance of SCPs as a tool to help improve care coordination.

Implications for cancer survivors:

These findings highlight the importance of general education about post-treatment survivorship, post-treatment survivorship needs identification, and the elucidation of gaps in effective SCP delivery among MBCS.

Keywords: Breast cancer, Care planning, Long-term cancer survivors, Minority health, Survivorship care plans

Introduction

The overall survival rate for female breast cancer is 90%, in part, due to extensive advances in early detection and treatment [1,2,3]. However, for Black women, the 5-year survival rates are lower than those for their non-Hispanic White counterparts, with a 5-year overall survival rate at 80% [3, 4]. Compared to their non-Hispanic White counterparts, Hispanic women also have a reduced 5-year survival rates at 88% [5]. Reasons for reduced survival rates for female racial and ethnic minorities are due, in part, to consequences of the increased likelihood of late-stage diagnosis and other unfavorable tumor characteristics (e.g., high grade, triple negative sub-type) [6, 7], lower neighborhood and individual socioeconomic status [8], and delayed treatments [9, 10]. Racial and ethnic minority women are also less likely than non-Hispanic White women to access high-quality services for follow-up [11], and have a timely follow-up after an abnormal mammogram [12]. Although these disparities are manifested before the period of post-treatment survivorship (i.e., early detection, diagnosis, treatment), they have implications on long-term survival rates. Further, such disparities are synergistic and do not exist independently. For example, while women living in lower SES conditions are often either uninsured or underinsured, these conditions may result in reduced opportunities to access breast cancer health promotion materials or the resources to initiate timely treatments and screenings for recurrent cancers [13]. Considering these persistent racial and ethnic disparities, efforts to improve survivorship outcomes is an emerging public health priority [2, 14].

Racial and ethnic disparities may reflect fragmented implementation of survivorship care, which can be facilitated through the implementation of survivorship care plans (SCPs). According to the Commission on Cancer (COC) [15, 16] and the Institute of Medicine (IOM) [17], SCPs are intended to prepare survivors for their transition from active treatment to long-term survivorship, improve care coordination, prevent new and recurrent cancers and late effects through healthy lifestyle promotion, provide evidence-based recommendations for follow-up screenings, and promote interventions for the consequences of cancer and treatment [17,18,19]. Guidelines from the National Comprehensive Cancer Network, American Cancer Society, and the American Society of Clinical Oncology further provide recommendations, associated tools, and benchmarks to facilitate the implementation of SCP [20,21,22]. While SCPs are highly endorsed by survivors [23, 24], the current implementation of post-treatment communication of SCPs is inconsistent across healthcare systems and cancer types and lacks supportive evidence, resulting in recent updates to CoC guidelines which resend the mandate that all survivors receive an SCP [25,26,27,28,29]. Moreover, there are reported trends in patient-provider communication across racial/ethnic groups, with minority patients reporting lower levels of patient-centered communication [30, 31]. Survivors receiving poor communication regarding long-term survivorship care are at a greater risk for having a poor understanding of their survivorship care and other risks associated with poor survivorship care, such as limited compliance to follow-up screening recommendations [32,33,34]. Considering the evidence of reduced survival rates and sub-optimal patient-provider communication faced by racial and ethnic minority breast cancer survivors (MBCS), an examination of cancer survivorship communication received by this vulnerable population is a critical step to understanding the role of survivorship communication and disparities in survival rates and associated outcomes.

There is a growing body of literature regarding the implementation of SCPs and the adoption of best practices in clinical settings [35,36,37]. However, there is wide variation in adherence and acceptance of these best practices. Previous reviews have searched the literature for the utilization of SCPs [38,39,40,41], and few have highlighted the perspective of racial and ethnic minority survivors [42]. Overall, findings from these studies highlight the benefits of SCP for improving disease management and aiding providers and survivors through communication related to care coordination. In a systematic review of survivor and provider preferences for SCPs and treatment summaries, authors reveal a gap in the literature, particularly a need for comparative effectiveness trials to compare preferences among diverse populations of cancer patients [42]. Findings from an integrative review of SCP usage and preferences from breast cancer survivors reported that most studies, to date, represented the perspective of non-Hispanic White survivors [40]. Considering the previous reviews, little is known about the implementation of SCPs among MBCS.

As interests in the implementation of SCPs increases, it is important to understand the nuances of the implementation of SCPs and the concerns related to the delivery of a SCP by racial and ethnic minority women. In addressing this gap, investigators will have a better understanding of potential inconsistencies in the implementation of SCP for MBCS that may guide targeted interventions and policies aimed to eliminate racial and ethnic disparities in survivorship rates. The purpose of this systematic review is to thematically identify concerns by female MBCS about their preparation for post-treatment survivorship care, the preferred practices for the delivery of a SCP, and the associated content to improve an understanding of post-treatment survivorship care. Lessons learned from this review can expose the weaknesses of the current delivery of SCPs, and reveal better practices to improve post-treatment survivorship communication and survivorship outcomes for MBCS.

Methods

Eligibility criteria

This search included articles published in the English language before April 26, 2019. Studies of interest included investigations conducted in the USA concerning post-treatment survivorship care (i.e., survivorship care after the completion of acute treatment, but excluding long-term hormonal therapies) and the use of SCPs by MBCS. For studies assessing differences between racial and ethnic groups, at least 25% of the sample population must self-identify with a racial or ethnic minority group (e.g., African-American/Black, Hispanic, Asian). This review considered all definitions of survivorship, but only extracted and analyzed information related to the post-treatment to end-of-life period of breast cancer survivors.

Articles were excluded if they did not explicitly report post-treatment survivorship care needs of the minority participants. Literature reviews were also excluded. As this is a retrospective review of data from previously published studies, patient informed consent procedures were not of consideration. This study is exempt from review by the Intuitional Review Board (IRB).

Data sources and search strategy

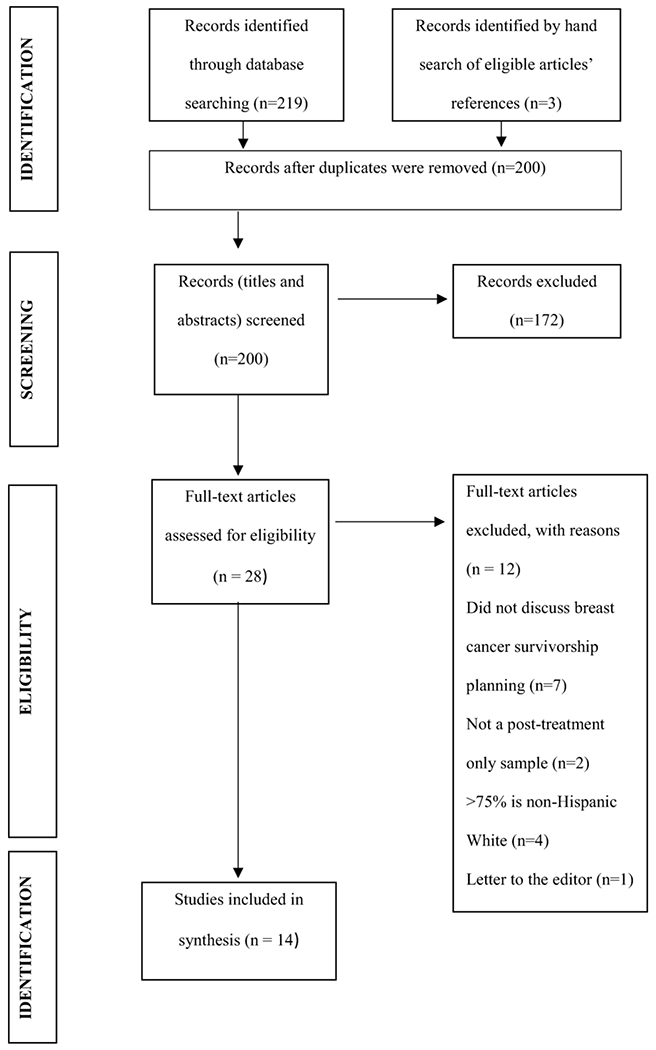

A paired team of reviewers (ML and TN) conducted systematic searches of PubMed, Ovid-Medline, and CINAHL databases using keywords for racial/ethnic minority groups (i.e., minority groups, African-Americans, Hispanic Americans, Asian Americans, Black, Hispanic, Latino, and Asian) and cancer survivorship care coordination terms (i.e., survivors, cancer survivors, breast, continuity of patient care, aftercare, patient care planning, health plan implementation, survivorship, care, plan, cancer, and follow-up). Selected databases accessed abstracts and citations representing a broad examination of published research, including topics related to nursing, allied health, oncology, and coordinated care. Last, authors (ML and TN) conducted a descendancy search of reference sections from included articles to find additional relevant articles. The current review method followed the PRISMA statement guidance for conducting a systematic review [43]. See Fig. 1 for a summary of the study selection process.

Fig. 1.

Identification of papers using the PRISMA scheme

All eligible articles included in this search underwent an initial title and abstract screening, and a full-text review before data extraction. All authors (ML, YM, TN, SS) screened imported articles based on the inclusion criteria using standardized procedures guided by a systematic review management tool, Covidence [44]. Reviewer pairs independently screened the title, abstracts, and full text via Covidence.

Data extraction and quality assessment

Two reviewers conducted the data extractions and quality assessment (ML and TN). A third reviewer resolved any disagreements (SS). During data extraction, reviewers (ML and TN) independently assigned quality assessment scores to each extracted article using the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) Critical Appraisal Checklist for Qualitative Research [45] and National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) Quality Assessment Tools for qualitative and quantitative articles, respectively [46]. A summary of the quality appraisal is shown in Table 1. A poor-quality assessment score did not exclude any articles from the search.

Table 1.

The study designs of the reviewed articles

| First Author (Year) | Study Design and Setting | Study description | Participant Sample | Key findings related to identified themes | Quality Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Advani (2014) | Design: Retrospective single observation cohort study Setting: A cohort of breast cancer survivors treated at The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center |

Data collection: gathered from the Cancer Center database. Aim: To examine the relationship between patient characteristics and adherence to surveillance mammography and follow-up clinic visits, and overall survival. |

N = 4,535 – White (71%) – Hispanic (11.4%) – Black (11.9%) – Native American (5.2%) |

Uncertainty about how to manage survivorship post-treatment care (follow-up care) – 15% of white patients were nonadherent to clinic visit guidelines in year 4 of survivorship care, compared with 26% and 20% of Hispanic and black patients, respectively. – There was no significant interaction between ethnicity and education level on nonadherence to clinic visit guidelines (P=0.13). – Black patients were more likely (OR = 1.12, 95% CI = 0.94 to 1.34) than white patients to be nonadherent or partially adherent to clinic visit guidelines. |

NIH Observational cohort 13/14 Good, Fair, Poor •No power statement •Unsure about blinding, but one can assume that as a retrospective study it was blinded. |

| Ashing-Giwa (2013) | Design: Qualitative Setting: All participants were members of the African American Cancer Coalition |

Data Collection: 3 “structured meetings” moderated by experienced moderators Aim: To report input from African-American Breast Cancer Survivors and advocates on appropriate cultural and socioecological content for an SCP template. |

N=28 – African-American Breast Cancer Survivors (82%) – African-American community health advocate (18%) |

Approval or need for SCPs and related materials – the SCP was useful for helping survivors to revisit and organize all of the information they had received from their doctors in the past. – 20% had seen or heard about treatment summaries and SCP. – 24 AABCS indicated that they received an assortment of unorganized documents Uncertainty about recurrent cancer risk reduction – More guidance and information on recurrences Preferred delivery method and content of SCPs – Suggestions for quality of life resources (emotional needs, financial needs, social support, transportation needs, spiritual care referrals, family needs, sexual health) – survivors are not aware of available informational, medical, and supportive care resources and that these should be noted in the SCP. – Improve usability and readability by enlarging the text and adding more spacing between each of the document items. – highlighted the number and severity of comorbidities among |

•8/10 • There is no statement to locate the researchers theoretically or culturally •Conclusions about the research are unclear |

| Ashing (2014) | Design: Mixed-methods Setting: Local Latina-focused cancer support and health advocacy groups, hospitals, Latino focused advocacy organizations, and support groups around the City of Hope Medical Center area |

Data Collection: 2 “consensus meetings” and a short questionnaire. Development of treatment summaries and SCP and Evaluation of treatment summaries and SCP Aim: To evaluate the utility of a Spanish language transcreation of the ASCO breast cancer treatment summary template (TSSCP-S). |

N=22 12 breast cancer survivors and advocates – Mexican-American (58%) – Central American (25%) – N=2 South American (17%) 10 interprofessional stakeholders – Mexican American (40%) – Central American (20%) – South American (30%) – Cuban American (10%) |

Approval or need for SCPs and related materials – the TSSCP-S template was more patient-user-friendly, quality, amount of detail, and information provided in the form was good. Preferred delivery method and content of SCP – incorporating information responsive to cultural values(familism, trust, respect) and social practices including spirituality (prayer and faith) and family support – health advisories, HRQOL and supportive care information and resources are inadequately documented and discussed TSSCP-S had higher ratings on content, clarity (Z=−2.25,p=0.02), utility (Z=−2.03,p=0.04), cultural and linguistic responsiveness (Z=−2.18,p=0.03), and socioecological responsiveness (Z=−2.52,p=0.01). |

• 8/10 • There is no statement stating the researchers cultural and theoretical location • Minimal reporting on the influence of the researchers on the research and vice versa. |

| Burg (2009) | Design: Qualitative Setting: Southeastern urban area that recruited from “Sisters Network” (a national African American organization with regional breast cancer support groups) and urban public health department |

Data Collection: 4 Focus groups Aim: To explore minority breast cancer survivors’ (1) recall of information from their oncologists about their cancer and follow-up care, (2) views on the potential use of SCPs, (3) cancer-related questions. |

N=32 – African American (91%) – Hispanic (3%) – White (6%) |

Approval or need for SCPs and related materials – unanimous approval of the concept of an SCP and believed that all survivors should have one for themselves, Uncertainty about how to manage survivorship post-treatment care – participants felt inadequately prepared for long-term survivorship. – participants felt they had to act “bossy” and aggressively ask questions to gain the information they needed – lack of a specific point of contact for follow-up care coordination. – Incomplete “Follow-up Care” section that lacks information on common issues women face in trying to stay healthy and avoid cancer recurrence Preferred delivery method and content of SCPs – Information about potential side effects and prevention and/or treatment approaches is not consistently delivered to breast cancer survivors – treatment summary portion used a lot of medical jargon and overly technical terminology. |

• 6/10 • Author’s interview guide fails to “explore the types of cancer-related questions minority survivors might bring to the primary care encounter” • Inadequate commentary on the implications of the study’s findings. • No statement locating the researcher culturally or theoretically • the influence of the researcher on the research is unknown |

| Burke (2016) | Design: Qualitative Setting: Women from the San Francisco Women’s Cancer Network with low health literacy and/or low English proficiency |

Data Collection: 6 focus conducted in English, Spanish, Cantonese, Russian, and Tagalog and separated by language. Moderated by bilingual facilitators. Aim: To identify informational and structural challenges to treatment and survivorship for safety-net breast cancer patients |

N=38 – Chinese (24%) – Filipina (18%) – White (16%) – African-American (13%) – Russian (11%) |

Uncertainty about survivorship as a stage in the continuum – Confusion about definitions of survivorship. – Women often remained on ongoing treatments despite ending active treatment – need for new terms of survivorship and active Approval or need for SCPs and related materials – None had received written information on what to expect in survivorship or transitioning Uncertainty about how to manage survivorship post-treatment care – Areas of information screening, recurrence, side effects and pain, reconstruction, and healthy eating/physical activity. – Needs more information on how to manage recurrence. – Participants and their primary care doctors, were confused about the level of screening and monitoring they should expect in survivorship. Survivorship care information should be delivered in a healthcare setting with more additional care coordination, quality of life, and culturally relevant content in SCPs – Time points to receive a SCP should be transition points during treatment (e.g. when side effects start to emerge), the transition between “active treatment” and “survivorship”, and subsequent points when needed. – Needed information (and often not obtained) includes information about screening, recurrence, side effects and pain, reconstruction, and self-care strategies related to diet, smoking cessation, nutrition, and exercise. – they wished a SCP would better equip them with the questions to ask one’s doctor – Include referrals to PCPs knowledgeable about breast cancer – Information on hereditary breast cancer |

• 8/10 • Inadequate reporting of the study’s interpretation of the findings. Talked about the utility of SCPs but not how this study advances the current knowledge • there is no statement locating the researcher culturally or theoretically |

| Casillas (2011) | Design: Cross sectional Setting: Survey to young adults survivors of different cancer types of the LIVESTRONG™ Survivorship Center of Excellence. Survey administered in-person at a clinic or via phone. Written components could be mailed. |

Data Collection: National survey Aim: To describe: (1) the health care settings utilized during the survivorship phase of care, (2) the self-reported receipt of survivorship care planning, (3) define survivors’ expectations of their providers, (4) explore characteristics of survivors who report low confidence in managing their survivorship care. |

N=376 – Non-Hispanic White (74%) – Mixed race/ethnicity (9%) – Hispanic/Latino (8%) – Asian (6%) – Black (3%) – Not reported (0.3%) * Only 5% of the population was a breast cancer survivor |

Approval or need for SCPs and related materials – 48% did not have a written treatment summary. – 55% did not have a written survivorship care plan. – 19% did not have a treatment summary, SCP, or medical records. – 26% possessed treatment summary, SCP, and medical records. Uncertainty about how to manage survivorship post-treatment care – racial/ethnic minority survivors were 66% less likely to have confidence in managing survivorship care. – and respondents reporting a lack of copies of medical records, a written treatment summary or survivorship care plan had higher odds of low confidence in managing survivorship care. – ethnic minority survivors lacking a SCP had significantly higher odds low confidence group. In survivorship management. |

• Fair score • Participation rate is unreported • Validated exposure measures are unreported |

| Greenlee (2016) | Design: Randomized control trial-comparing the effects of a single 2-hour survivorship counseling session with nurse and nutritionist (intervention) vs. printed materials on diet and lifestyle knowledge and behaviors (control) Setting: Columbia University Medical Center breast oncology clinic. |

Data collection: Questionnaires at baseline, 3, and 6 months. Aim: To evaluate the efficacy of survivorship care plans on post-treatment diet and lifestyle behavior change. |

N=126 Race: – White (61%) – Black (26%) – Asian (3%) – American Indian (<1%) – Other (10%) Ethnicity – Hispanic (48%) |

Uncertainty about recurrent cancer risk reduction – Intervention had a stronger effect on increasing non-Hispanics’ belief that a healthy diet was important to prevent breast cancer recurrence. |

• Fair/Poor • Not sure if other interventions were avoided considering the results were stratified by ethnicity and this maybe confounded by low levels of education and lower income. • Measures were not reported • Power calculations were not reported |

| Hershman (2013) | Design: Randomized control trial-comparing the effects of a single 2-hour survivorship counseling session with nurse and nutritionist (intervention) vs. printed materials on diet and lifestyle knowledge and behaviors (control) Setting: Columbia University Medical Center breast oncology clinic. |

Data collection: Questionnaires at baseline, 3, and 6 months. Aim: To evaluate the effect of an in-person survivorship intervention following adjuvant breast cancer therapy on health worry, treatment satisfaction, and the impact of cancer and (2) to determine if differences exist between His-panic and non-Hispanic ethnic groups |

N=124 Race: – White (59%) – Black or Caribbean (27%) – Asian (3%) – American Indian (<1%) – Other (10%) Ethnicity – Hispanic (48%) |

Uncertainty about how to manage survivorship post-treatment care – IOC (long-term survivorship concerns) was higher in the control group. – ASC (worry of recurrence). increased in control group and decreased significantly in the intervention group. – The health worry subscale higher for the control group. – Hispanic survivors had higher health worry and long-term survivorship concern scores than Non-Hispanic survivors. |

• Good • Not sure if other interventions were avoided considering the results were stratified by ethnicity and this maybe confounded by low levels of education and lower income. |

| Maly (2017) | Design: Randomized control trial-participants were randomly assigned to Setting: Breast clinics: (1) Los Angeles County, Harbor-University of California at Los Angeles (UCLA) Medical Center and (2) Los Angeles County plus University of Southern California Medical Center. |

Data collection: In-person baseline interview followed by telephone interviews quarterly. Aim: To explore the receipt and implementation of usual survivorship care (control) and individually tailored treatment summary and SCPs with a nurse counseling session with a bilingual moderator (intervention) on physician implementation of and patient adherence to recommended survivorship care, among a low-income population of breast cancer survivors over 12-months of follow-up care. |

N= 212 Ethnicity – Latina (72%) Race data was not reported. |

Approval or need for SCPs and related materials – Latinas agreed that the care plan provided more information than their provider. – For Latinas, SCPs provided new information they had not previously found on their own. – Treatment summaries and SCPs improved communication with providers. – The mean physician implementation score for TSSP recommendations was significantly greater for the intervention group. – The mean patient adherence score was greater for the intervention group. |

• Good |

| Olagunju (2018) | Design: Cross-sectional Setting: Breast clinics: (1) Los Angeles County, Harbor-University of California at Los Angeles (UCLA) Medical Center and (2) Los Angeles County plus University of Southern California Medical Center. |

Data collection: Telephone surveys with a bilingual interviewer. Aim: To identify gaps in knowledge, survivorship preparedness, and satisfaction with information received between Latinas and non-Latina patients enrolled in a randomized control trial. |

N= 212 Ethnicity – Latina (72%) Race data was not reported. |

Approval or need for SCPs and related materials – Latinas were less satisfied with the information they received for BC care Uncertainty about how to manage survivorship post-treatment care – Latinas reported less breast cancer survivorship knowledge |

• Fair • Sample size not justified. • Validity of the exposure measures was not reported • Did not test for confounder |

| Royak-Schaler (2008) | Design: Qualitative Setting: The University of Maryland Greenebaum Cancer Center, the Baltimore Washington medical center, the Sisters Network Baltimore Chapter, and the American Cancer Society’s Reach to Recovery Program. |

Data collection: 4 focus groups Aim: To investigate preventive health actions, understanding, and use of prevention and assess the understanding of cancer risk factors for breast cancer recurrence. |

N= 39 African American breast cancer survivors | Approval or need for SCPs and related materials – Most survivors have developed some type of survivorship care plan, largely without specific guidelines from physicians. Survivorship care information should be delivered in a healthcare setting with more additional care coordination, quality of life, and culturally relevant content in SCPs y method and content of SCPs – Older survivors dis not favor the Internet or computer-based educational programs as sources of information. – Older survivors identified brochures (13 of 19) as their main source of information, and younger participants (< 55 years) preferred the information provided by healthcare providers (15 of 20). – Books and the internet were identified as important sources but ranked after information provided in the healthcare setting. |

• 8/10 • Note: This study’s purpose addresses prevention of breast cancer recurrence, but the findings seem to apply to all of survivorship care. • There is not statement locating the researchers culturally or theoretically. • There is no commentary of the influence of the researchers on the research or vice versa. |

| Tisnado (2016) | Design: Qualitative Setting: Los Angeles County |

Data collection: 12 focus groups with bilingual interviewers. Aim: To examine the ways in which Latinas conceptualize survivorship care and their knowledge, attitudes, and beliefs regarding survivorship care for their breast cancer. |

N=74 Latina women | Uncertainty about recurrent cancer risk reduction – Many women did not know what the overall plan was for their care as they transitioned from receiving primary treatments to the survivorship phase of care; they instead relied upon their health care providers to let them know on an as-needed basis. Approval or need for SCPs and related materials – Few ever received a SCP and for most women, the study introduced them to a SCP. – Most women desired a more formalized presentation of care recommendations Uncertainty about how to manage survivorship post-treatment care – Confusion and concern about the quality of their own care due to the many variations in use of treatments and surveillance tests, and the perceived level of health care provider concern over side effects and late effects. Survivorship care delivery preferences for tailoring – Interest in more information about the risks, benefits and recommendations regarding diet, exercise, rest and stress reduction, use of complementary and alternative therapies, and other self-care activities. |

• 9/10 • Did not include questions about follow-up care activities. |

| Napoles (2017) | Design: Mixed methods Setting:5 counties from Northern California |

Data collection: – With survivors: Telephone survey and semi-structured interviews or focus group with a bilingual interviewer. – With cancer survivor support: semi-structured interviews. – With physicians: semi-structured interviews Aim: To identify the symptom management, psychosocial, and informational needs of Spanish-speaking breast cancer survivors during the transition to survivorship from the perspectives of the survivors, their cancer support providers, and cancer physicians. |

N= 118 Telephone surveys with Spanish-speaking survivors N=22 Spanish-speaking survivors completing individual and focus group interviews N=5 Spanish-speaking survivors’ support interviews N=4 Physician interviews – Non-Hispanic White (50%) – Asian (50%) |

Uncertainty about survivorship as a stage in the continuum – A desire for a formal transition from active treatment to follow-up care. Uncertainty about how to manage survivorship post-treatment care – Fear of recurrence when obtaining follow-up care. – Desired help with eating a healthier diet, getting more exercise, managing stress, and doing yoga or meditation. |

• 7/10 • No congruity between the stated philosophicalperspective and the research methodology • No statement locating the authors culturally or theoretically • Did not address the influence of the research on the researcher |

| Royak-Schaler (2009) | Design: Cross-sectional Setting: Baltimore Maryland medical center |

Data collection: Telephone survey Aim: To investigate, from the patient’s perspective, physician communication about the IOM Guidelines for Survivorship Care, and subsequent behaviors related to cancer prevention. |

N=99 survivors Race: – African-American (30%) – Caucasian (70%) |

Uncertainty about how to manage survivorship post-treatment care – Concerns about recurrence were positivity correlated with an increased knowledge of IOM Guidelines for Survivorship Care. |

• 12/14 • 99/335 participants • No power statement • 13/14 • participation rate of eligible persons was greater than 50%? |

Data analysis

To analyze the extracted data, a paired review group independently (ML and SS) identified SCP implementation themes from the extracted data. Themes were inductively developed, reviewed, and refined. Paired reviewer group YM and TN reviewed the refined themes, discussed thematic relevance, and reached a consensus on concordant themes. This approach was guided by previously published data analysis plans [47, 48].

Results

Figure 1 presents the identification and selection process in the PRISMA flow diagram. We identified 222 publications from all sources. After removing duplicate articles, 200 abstracts and titles were screened, of which 28 were included in the full-text review. Based on a full-text review, we excluded an additional 12 manuscripts. A total of 14 studies were eligible for inclusion for analysis [25, 49, 50, 51, 52, 53, 54, 55, 56, 57, 58, 59, 60, 61, 62, 63]. Table 1 presents the article descriptions and results.

Study characteristics

The study designs of the reviewed articles are presented in Table 1. This review included five qualitative studies [25, 49, 51, 59, 60], three cross-sectional studies [52, 57, 62], three randomized control trials [53,54,55], a single observation cohort study [63], and two mixed-methods studies [50, 61]. Focus group interviews were the most frequently used qualitative study design [25, 51, 59, 60]. A few exceptions to the focus group study design were “structured meetings” [49] and “consensus meetings” with a short questionnaire [50]. Four studies had a bilingual sample and/or used a trained bilingual interviewer [25, 50, 60, 61]. All cross-sectional surveys were administered over the phone, of which one study also administered a survey in-person at a clinic and a written component could be mailed [52].

Study aims are also presented in Table 1. Broadly, some qualitative studies aimed to assess the quality of information and utility of SCPs [25, 49,50,51]. Two other studies using qualitative study designs focused on the overall survivorship care of minority survivors [60, 61] and a single study more narrowly aimed to examine minority survivors’ understanding of cancer prevention and risk of recurrence [59]. The aims of the cross-sectional studies broadly addressed topics related to understanding survivorship [52, 57] and mammography surveillance guidelines [62]. All intervention arms of the reviewed randomized control trial developed tailored components of a SCP (e.g., treatment summary, mammography guidelines, lifestyle recommendations) that were delivered by a nurse and/or nutritionist, and focused on knowledge and attitudes of lifestyle behaviors [53]; health worry, treatment satisfaction, and the impact of cancer [54]; and adherence to the recommended survivorship care [55]. The observational cohort study represented in this review investigated associations between patient characteristics and adherence to mammography guidelines and follow-up clinic visits from a Cancer Center database [63].

Articles selected for this review represent 5,854 participants and over 12 different racial/ethnic groups. Of the 14 studies that meet the eligibility criteria within this systematic review, nine studies recruited multi-ethnic study samples [25, 51, 52, 53, 54, 55, 57, 62, 63]. Of the remaining studies, two studies had participants that solely identified as being African-American/Black [49, 59], and two other studies had participants that solely identified as being Hispanic [50, 60]. The majority of the studies (n = 11) solely recruited cancer survivors within their study sample [25, 51, 52, 53, 54, 55, 57, 59, 60, 62, 63]. Three studies recruited a combination of survivors along with community health advocates or health care professionals [49, 50, 61].

Table 1 presents the quality assessment of the 14 studies included in this review. Using the JBI Critical Appraisal Checklist for Qualitative Research [45], quality assessment scores ranged from 6 to 9 of 10 possible points. The quality of cross-sectional and observational cohort studies was assessed with the appropriate NHLBI Quality Assessment Tool, two studies had fair quality [52, 57], and a single study was scored as good quality [62]. Using the NHLBI Quality Assessment Tool, randomized control trial quality assessment scores ranged from poor [53] to good [54, 55].

Themes representing SCP content delivery preferences and needs

Three themes emerged from the reviewed literature of SCP delivery and content preferences and needs among female MBCS. These themes are as follows: (1) an uncertainty about post-treatment survivorship care management is a consequence of sub-optimal patient-provider communication, (2) access to SCPs and related materials is desired but sporadic, and (3) advancements to the delivery and presentation of SCPs and related materials are preferred. Following, we summarize the evidence supporting each theme and display an overview of the results in Table 1.

Uncertainty about post-treatment survivorship care management is a consequence of sub-optimal patient-provider communication

Sub-optimal communication resulted in survivors’ uncertainty and confusion about the appropriate care for long-term post-treatment survivorship in almost half of the selected studies (n = 6) [25, 51, 52, 57, 59, 60]. Uncertainty about post-treatment survivorship care varied across racial and ethnic groups. In Casillias et al. [52], MBCSs were 66% more likely to have low confidence in managing their survivorship care than non-Hispanic White survivors. In a cross-sectional sample of low-income Hispanic breast cancer survivors, survivors were more likely to report less breast cancer survivorship knowledge than the mostly racial and ethnic minority (e.g., African-American and Asian) comparison group [57]. In two qualitative studies, respondents felt the need to act “bossy” or aggressively with providers to receive adequate information on survivorship care from providers [51, 59].

Several studies also elucidated targeted areas of confusion and uncertainty that influenced survivors’ overall confidence in their ability to manage their post-treatment survivorship. Both the (1) survivors’ inadequate understanding of follow-up care needs and (2) the appropriate means to reduce the risk of recurrent cancers were related to poor communication about post-treatment survivorship care, thus uncertainty about post-treatment survivorship care management.

Uncertainty about follow-up care

One study reported that minority women had poor adherence to follow-up care clinic visits [63]. In Advani et al. [63], African-American survivors were 12% more likely to be nonadherent to follow-up clinic visits than White survivors. Two qualitative studies included African-American and Hispanic breast cancer survivors’ perspective regarding uncertainty about managing post-treatment survivorship care [51, 60]. Respondents of one study reported confusion about management of survivorship care was due, in part, to survivors’ inability to identify a specific clinical contact to initiate follow-up care [51]. In the all Hispanic breast cancer survivors’ focus group, respondents expressed confusion and concern about their overall quality of survivorship care because of perceived variations in the recommended amount of surveillance testing and poor communication regarding side effects and late effects of treatment [60].

Uncertainty about recurrent cancer risk reduction

Reducing the risks and fears of recurring cancers through timely follow-up clinical visits is key to post-treatment survivorship management. Six studies reported survivor fears of recurring breast cancers [25, 49, 51, 59, 61, 62], of which three studies reported that fears of recurrence were related to survivors’ uncertainty about necessary survivorship care [25, 51, 59]. In Burke et al. [25], survivors representing multiple racial and ethnic groups reported that primary care providers were uncertain about the expected level of screening and monitoring needed to reduce the risk of recurrence, thus contributing to survivors’ confusion about cancer risk reduction. Similarly in Burg et al. [51], survivors were confused by SCP templates that inadequately provided information about recurrence risk reduction. Uncertainty about the role of diet modifications and physical activity on risk reduction also contributed to uncertainty about necessary post-treatment management. In another study, 38 of 39 focus group respondents expressed receiving unclear recommendations for dietary and physical activity changes needed to reduce breast cancer recurrence [59]. Some African-American survivors participating in these focus groups explained that providers were initially dismissive and unresponsive toward their concerns about recurring cancers. When post-treatment recommendations and care needs were inadequately addressed, respondents relied on anecdotal strategies or theories. However, in a randomized control trial, non-Hispanic intervention survivors, which include some African-American, Asian, and American Indian survivors, were more likely to believe that a healthy diet helped prevent cancer recurrence after receiving a 2-h counseling from a nutritionist and nurse and a brochure on health behaviors changes for breast cancer survivors [53]. In a subsequent analysis, mean scores of long-term survivorship concerns were higher for control group participants receiving only the brochure than intervention participant receiving both the brochures and personalized counseling. Further, concerns about cancer recurrence increased overtime for control participants. Hispanic survivors reported higher scores for long-term survivorship and recurrence scores [54].

Access to SCPs and related materials are desired but sporadic

Of the selected articles, several studies revealed survivors’ approval of written materials to help organize medical and personal care concerns through post-treatment survivorship. Concerns about accessing SCPs and the desire for ongoing care planning spanned across ethnic groups. For some survivors, barriers to accessing post-treatment recommendations were a product of ambiguity around their transition into post-treatment status. For other survivors, other materials to supplement a SCP were desired.

Ambiguity about transitioning into post-treatment status

Four studies reported findings that survivors were uncertain about the completion of their active treatment and their transition into post-treatment survivorship [25, 59,60,61]. Survivors unaware of their post-treatment status may fail to advocate for a SCP, but may rely on their own care strategies [59]. In one study, survivors reported confusion about the definition of survivorship. Such ambiguity resulted from women continuing ongoing treatments despite providers communicating that active treatment had ended [25]. Respondents in Tisnado et al. [60] explained that an overall plan of care for transitioning was discussed on a “need to know” basis with their provider. Respondents had emotional and physical concerns, unmet physical symptom management needs, and felt abandoned by their health care team as they transitioned from active treatment to post-treatment survivorship care, while respondents from Napoles et al. [61] expressed the desire for a more formal transition to guide women from active treatment to follow-up care. Another suggestion of respondents from multi-ethnic focus groups in Burke et al. [25] was to develop new terms for active treatment and survivorship to reduce ambiguity.

Approval or need for SCPs and related materials

Despite the reported benefits of written SCPs for MBCS, four studies indicated that some survivors had never received a written SCP, or the respective study introduced survivor participants to a SCP [49, 52, 60]. In Ashing-Giwa et al. [49], only 20% of the respondents had ever seen or heard of both a treatment summary and a SCP. Instead, 24 of 25 African-American survivors reported receiving a collection of unorganized documents to describe recommended survivorship care. From a nationwide sample, 19% of those surveyed never received their medical records, a written treatment summary, or a SCP. In one study of 376 survivors, 179 (48%) of the survivors did not receive a written treatment summary, and 208 (55%) did not have a written SCP [52]. Hispanic women in Olagunju et al. [57] were dissatisfied with the received breast cancer survivorship care information. For all racial and ethnic minority survivors in this nationwide study, non-White race and lacking a written SCP was significantly associated with low confidence in managing survivorship care. In a study investigating the receipt of survivorship care from a “safety-net” hospital, all respondents from the multi-ethnic focus groups reported never receiving written information on survivorship care [25]. In another study, survivors that never received a SCP widely desired a formalized written presentation of survivorship care coordination [60].

MBCS and advocates that either received or reviewed a SCP found that SCPs were helpful for understanding survivorship care (n = 4) [49,50,51, 55]. In Royak-Schaler et al. [59], African-American breast cancer survivors developed their own SCP when one was not provided, which often did not include specific screening guidelines. Some Hispanic women that had access to a SCP were more likely to follow provider-recommended care, experience improved communication with their provider, and receive new information to supplement their health information research [55]. One study sample of African-American breast cancer survivors and advocates reported that all respondents considered SCPs useful for organizing relevant treatment and post-treatment survivorship information [49]. Receipt of a SCP and treatment summaries has benefits for minority survivors and their providers. Maly et al. [55] developed an intervention to test the effects of personalized treatment summaries and a SCP coupled with nurse counseling versus usual survivorship care for MBCS. In this study, providers of intervention participants, compared to providers of control participants, had improved implementation of survivorship care, such as recommending psychosocial services. Overall, survivors in the intervention group were more adherent to follow-up recommendations than those in the control group.

Advancements to the delivery and presentation of SCPs and related materials is preferred

As it is evidenced that SCPs are valued by MBCS, those reporting to have received a plan commented on methods to improve the implementation of SCP and post-treatment care, namely through the (1) desired delivery of care communication, and (2) additional information to add to SCPs and related materials.

Desired delivery of post-treatment survivorship care communication

Women from two studies identified various methods of receiving their post-treatment survivorship care information [25, 59]. Some survivor participants from Burke et al. [25] preferred receiving survivorship care information at relevant periods during treatment and post-treatment survivorship, including during active treatment, at the time of transition from “active treatment” to post-treatment “survivorship,” and at intermittent periods during long-term survivorship. Younger survivor participants (< 55 years), from Royak-Schaler et al. [59], preferred to receive information from healthcare providers. Older survivor participants (≥ 55 years) preferred to receive survivorship care information from brochures, but did not prefer to receive information from the Internet or computer-based educational sources. All survivors in this study favored receiving survivorship information from the healthcare setting more than information from books or the Internet. The majority of the respondents identified other breast cancer survivors as an ideal information source.

Additional information to add to SCPs and related materials

In addition to adaptations to the delivery of post-treatment survivorship communication, MBCS desired additional information for SCP and treatment summaries. Survivors from five studies reported that the content of post-treatment survivorship care communication lacked information explaining screening, treatment side effects, pain management, and recommended health behaviors [25, 51, 59,60,61]. Women participating in a telephone survey of breast cancer survivorship needs desired information regarding eating healthier (74%), physical activity (69%), managing stress (63%), and doing yoga and meditation (55%) [61]. Additionally, many women expressed an interest in quality of life information for stress reduction and rest, financial needs, social support, transportation, spiritual care referrals, family support, and sexual health [49, 50, 60]. A sample of African-American of breast cancer survivors and survivorship community health advocates recommended amendments to the SCP such as enlarging the text to improve usability and readability [49]. Findings related to the desired content of a SCP from Burke et al. [25] revealed that respondents wanted SCPs that helped them feel morfse comfortable to ask questions about preferred health behaviors and managing side effects. Burg et al. [51] suggested reducing the use of medical jargon in treatment summaries and substitute existing language with “planier English.” For Spanish-speaking survivors, an important consideration was the creation and evaluation of a culturally competent SCP with content, imaging, and Spanish language translations [50]. MBCS representing multiple ethnic groups (e.g., African-American, Chinese, Filipina, Hispanic) desired SCPs that provided referral information for primary care providers knowledgeable in breast cancer survivorship care [25, 49]. Although less frequently reported, but important to note, some survivors desired content regarding information about genetic risks of breast cancer [25], alternative therapies [60], and risks of comorbidities [49].

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first systematic review of the implementation and related concerns of SCPs among MBCS. As many of the racial and ethnic groups represented in the reviewed studies have a lower survival rate and poorer survivorship outcomes than non-Hispanic White women, and most of the existing reviews of the implementation of breast cancer survivorship care sample predominately non-Hispanic White women, our review is unique. The themes about the current implementation of SCPs emerged from the reviewed data which were shared across minority race and ethnic groups. The reviewed literature represents a diversity in study designs and the representation of over 12 different racial/ethnic groups. Collectively, the data identified three themes: (1) uncertainty about post-treatment survivorship care management is a consequence of sub-optimal patient-provider communication; (2) access to SCPs and related materials are desired, but sporadic; and (3) advancements to the delivery and presentation of SCPs and related materials is preferred. Salient themes from this review therefore support development and implementation of culturally targeted and tailored SCP for MBCS.

Whereas MBCS widely accepted SCPs, several reviewed articles reported that some minority survivors never received a SCP. Indeed, this finding supports previous evidence of larger administrative barriers to implementing SCP, particularly for healthcare facilities that service a higher volume of uninsured or underinsured patients [64, 65]. Nurses and physicians report administrative burdens associated with completing a SCP as a major barrier to its implementation [66]. Potential tools to overcome this barrier to implementing a SCP include patient advocacy, training programs [66], further implementation science investigations [67], and support from professional societies [15]. However, resource poor healthcare facilities, which are also likely to serve racial and ethnic minority population [68], may have limited access to the tools to overcome these administrative burdens. Thereby, MBCS are less likely to access these tools. Without tools to address current barriers to care planning, MBCSs have an increased likelihood of receiving poorer post-treatment survivorship care than their non-Hispanic White counterparts thereby potentially perpetuating racial disparities in post-treatment survivorship care.

Our results reveal that the lack of knowledge about the preferred method to receive post-treatment survivorship care information and the desired supplemental content are commonly reported challenges in implementing survivorship care. Overall, providers support the development and utility of SCPs as a method to improve patient-provider post-treatment survivorship communication; however, many providers report ambivalence about the best methods and information to report and discuss survivorship planning [37]. Evidence of inconsistent implementation of SCPs are seen in other populations such as adolescent young adults [69], rural women [28], and bowel cancer survivors [37]. In a similar study, Beaupin et al. [35] identified themes from young adult cancer survivors and revealed that 30% of the young adults failed to receive adequate, ongoing survivorship care after completing treatment. Like the MBCS reviewed in the current study, young adult survivors suggested desired content to the SCPs including a treatment summary with a follow-up schedule, screening recommendations, and contact information of specialists. Collectively, these findings indicate reoccurring gaps in post-treatment survivorship communication, and suggest the need for further implementation investigations to develop communication tools to improve and standardize survivorship care communication.

Other barriers to implementing post-treatment survivorship to MBCS, namely those where English is not their native language, are language barriers and the associated challenges of translating post-treatment survivorship care to written instructions [70]. Healthcare providers may not have access to interpreters that can communicate to non-native English-speaking survivors and their caregivers. Further, providers may not have access to pre-printed post-treatment survivorship care information or the ability to develop a SCP in languages other than English. Collectively, language barriers can make it difficult for providers to engage patients and caregivers. For Spanish-speaking breast cancer survivors, Napoles and colleagues used a mobile phone app and telephone coaching to address disparities in survivorship care knowledge among Latina survivors. Compared to baseline results, users experienced lower levels of fatigue, distress, and improved knowledge of follow-up care and emotional well-being [71]. Patient-centered activation interventions, such as mobile phone apps and telephone coaching, for non-native English-speaking survivors, show great promise to mitigate language barriers regarding post-treatment survivorship communication for racial/ethnic minority cancer survivors.

Reviews synthesizing study findings on MBCS’ perspective on the implementation of post-treatment survivorship are underrepresented in the literature. This is evidenced by 10 of the selected studies in this review represented ≤ 3 times in previous reviews, wherein Ashing et al. (2014) and Napoles et al. (2017) were never represented in a literature review before this study [50, 61]. Previous reviews of the implementation of post-treatment care of breast cancer survivors were often comprised of intervention studies and an underrepresentation of MBCS. Thematic analysis of these studies mostly focused on characteristics of post-treatment care rather than the implementation of care, including returning to work interventions [72,73,74], persistent pain [75], and tools to help manage survivorship care [76, 77], For reviews investigating survivorship care plans across cancer types, providers and survivors supported the use of SCPs, similar to reports from the current study [41, 42]. While MBCS in this study desired a SCP at intermittent periods throughout survivorship, in Klemanski et al., survivors desired SCPs within 0–6 months of post-treatment care [42]. Survivors from a review of survivorship care interventions described that interventions activated care management and improved patient-provider communication, both of which were identified areas of concern for MBCS in the current study [78]. From the limited review studies on racial and ethnic survivors, and consistent with themes identified in this study, findings recognized a need for culturally relevant supports and education in post-treatment care [79], including sexual concerns [23]. Thus, post-treatment survivorship care of MBCS should ideally entail a SCP.

It is worth noting that in 2020, the COC standards for survivorship programs no longer required the delivery of SCPs as a standard component of care, while still encouraging and recommending the use of SCPs as one of the services offered in a survivor’s care program [29]. Despite the relaxation in SCP requirements by the COC, findings from this study reflect disparities relevant to the COC’s required delivery of SCPs as of April 26, 2019—the date of the current study’s initial search. Further, the 2020 COC survivorship program standards continue to mandate that providers give survivors a list of services and programs for the care needs of survivors. Similarly, the current study identified that such a list is not only desired by MBCS but also infrequently delivered. Data from this review signal that as standards of care are updated, there is a persistent need to investigate disparities in the delivery of standards of survivorship care across racial and ethnic groups [29].

Clinical implications for MBCS

Findings from this review highlight the importance of general education about post-treatment survivorship, identification and management of post-treatment survivorship needs, and elucidation and mitigation of gaps in effective and efficient SCP delivery among MBCS. Universal high-quality cancer care is the goal for every cancer survivor. A fundamental concern that arose from this review is a need for healthcare providers to emphasize the continuum of cancer care with MBCS. Though there is consensus across national agencies that survivorship begins at the time of diagnosis, definitions of survivorship may not be salient. Further, iteration of consequences of cancer and its treatment, for various reasons, may not be adequately discussed with MBCS. Despite published standards of survivorship care and calls to action, implementation of SCPs which can be used as an opportunity to educate is subpar [15]. In moving forward, this implementation must become routine, be personalized, and be directive toward the needs of each survivor [80]. Further, the introduction of a SCP should be at the time of diagnosis, although this timing is unprescribed and highly dependent on the provider and other members of the care team. Our findings that MBCS shared concerns about the delivery of SCPs suggest that future researchers should conduct qualitative studies to explore the best SCP delivery methods among MBCS further exploring differences by cancer stage and treatment.

Here we found that MBCSs are receptive to routine surveillance of post-treatment survivorship needs, and they experience positive outcomes from this care. Yet, few oncology providers identify as survivorship specialists [81]. There is a need to educate the healthcare workforce about post-treatment survivorship care and resources available both locally and nationally. As illustrated in Nolan et al., training of advanced practice providers can be accomplished with dedicated time to engage in a survivorship-focused fellowship with clinical rotations, with fellowship alumni exhibiting better ability to manage post-treatment survivorship concerns than those who had not participated in the fellowship [82]. An informed healthcare provider can both inform and empower survivors to be active participants in care across the cancer continuum.

Activated survivors will require the health system to tailor support to their post-treatment survivorship needs. As the incidence of breast cancer continues to rise among minorities, findings from this review are pertinent. We identified that early initiation of detailed, culturally relevant post-treatment survivorship education is preferred among MBCS. However, to date, there is no empirical consensus on best practices for SCP delivery with respect to any population but there are recommendations [36, 40]. Further research to identify and employ interventions that address post-treatment survivorship in diverse populations is warranted.

Limitations

A strength of this review is that the reported studies represented heterogeneous methodologies, including randomized control trials and qualitative studies that enabled the elucidation of common SCP implementation patterns across study designs. Further, the reviewed studies included a diverse sampling of racial/ethnic sub-populations of breast cancer survivors, such as samples representing mono- and multi-ethnic, non-English-speaking, and immigrant groups. Consequently, we were also able to compare and identify the strengths and challenges of implementing SCPs across a spectrum of MBCS. However, this review is not without limitations. This review is limited to searches conducted in PubMed, Ovid-Medline, and CINAHL and might have benefited from additional searches from complementary databases (e.g., Embase, Web of Science, Scopus) to find additional studies that fit this review’s inclusion criteria. Aware of this limitation, a trained librarian conducted a similar search that rendered only three additional manuscripts to the authors’ original search. After two searches, the authors concluded that supplementary searches were unlikely to provide significantly different results. Moreover, this review was limited to articles published in English, thus excluding unpublished articles or articles published in another language. Despite the potential for publication bias, the identified themes are common to studies of SCP implementation from other marginalized populations (e.g., rural) [83] and across cancer sites (e.g., endometrial cancer) [28] suggesting that the influence of this bias is likely minimal and that the authors have adequately identified a gap in the post-treatment survivorship literature. Finally, this review synthesized findings related to care at the period of post-treatment survivorship and did not explore the implementation of SCP for survivors at diagnosis or during active treatment. The care needs of survivors considerably change as they progress through the cancer continuum. Further research is needed to explore the implementation of SCPs for MBCS at diagnosis and during active treatment, as it requires more detail and synthesis than permitted in a single study.

Conclusion

From this review of SCP utility and preferences, MBCS across the literature identified (1) an uncertainty about post-treatment survivorship care management as a consequence of sub-optimal patient-provider communications; (2) an appreciation for SCPs and related materials, but found access to these tools sporadic; (3) that adaptations to the implementation of post-treatment survivorship care must include changes to both the delivery of SCPs and the written material. While the implementation of post-treatment survivorship communication is not standardized, MBCS recognized SCPs as a useful survivorship care coordination tool. These findings highlight a need to reinforce post-treatment survivorship communication with SCPs. These findings have implications for improved survivorship care coordination between MBCS and members of their care team and informs the body of literature that aims to identify associations between access to SCPs and survivorship outcomes. As such, using the existing evidence to consistently employ SCPs with all breast cancer survivors, namely MBCS, will hopefully advance and strengthen the evidence for the utility of SCPs and potentially aid to reduce persistent racial and ethnic breast cancer disparities.

Acknowledgments

We thank Debbie Thomas of Becker Medical Library at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis for her work with the team to provide assistance in our search.

Funding

Dr. Lewis-Thames was supported by a Northwestern University Clinical and Translational Sciences Institute (NUCATS) UL1TR001422 (PI: Lloyd-Jones) grant, the Center for Community Health (CCH), a T32CA190194 (PI: Colditz/James), the Foundation for Barnes-Jewish Hospital, and by Siteman Cancer Center. Dr. Strayhorn was supported by the Cancer Education and Career Development Program at the University of Illinois at Chicago (T32CA057699). Dr. Molina was supported by the National Cancer Institute (K01CA193918).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: Disclaimer The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official view of the National Institutes of Health.

Conflict of interest The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Research involving human participants and informed consent As this is a retrospective review of data from previously published studies, patient informed consent procedures were not of consideration. This study is exempt from review by the Intuitional Review Board (IRB).

Ethical approval As this is a retrospective review of data from previously published studies, ethical approval is not required.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

- 1.DeSantis CE, Ma J, Goding Sauer A, Newman LA, Jemal A. Breast cancer statistics, 2017, racial disparity in mortality by state. CA Cancer J Clin. 2017;67(6):439–48. 10.3322/caac.21412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.DeSantis CE, Ma J, Gaudet MM, Newman LA, Miller KD, Goding Sauer A, et al. Breast cancer statistics, 2019. CA Cancer J Clin. 2019;69(6):438–51. 10.3322/caac.21583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2019. CA Cancer J Clin. 2019;69(1):7–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer Statistics, 2017. CA Cancer J Clin. 2017;67(1):7–30. 10.3322/caac.21387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Siegel RL, Fedewa SA, Miller KD, Goding-Sauer A, Pinheiro PS, Martinez-Tyson D, et al. Cancer statistics for Hispanics/Latinos, 2015. CA Cancer J Clin. 2015;65(6):457–80. 10.3322/caac.21314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Siegel R, Ward E, Brawley O, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2011: the impact of eliminating socioeconomic and racial disparities on premature cancer deaths. CA Cancer J Clin. 2011;61(4):212–36. 10.3322/caac.20121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sung H, DeSantis CE, Fedewa SA, Kantelhardt EJ, Jemal A. Breast cancer subtypes among Eastern-African-born black women and other black women in the United States. Cancer. 2019;125(19): 3401–11. 10.1002/cncr.32293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ren JX, Gong Y, Ling H, Hu X, Shao ZM. Racial/ethnic differences in the outcomes of patients with metastatic breast cancer: contributions of demographic, socioeconomic, tumor and metastatic characteristics. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2019;173(1):225–37. 10.1007/s10549-018-4956-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Silber JH, Rosenbaum PR, Clark AS, Giantonio BJ, Ross RN, Teng Y, et al. Characteristics associated with differences in survival among black and white women with breast cancer. JAMA. 2013;310(4):389–97. 10.1001/jama.2013.8272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gwyn K, Bondy ML, Cohen DS, Lund MJ, Liff JM, Flagg EW, et al. Racial differences in diagnosis, treatment, and clinical delays in a population-based study of patients with newly diagnosed breast carcinoma. Cancer. 2004;100(8):1595–604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ansell D, Grabler P, Whitman S, Ferrans C, Burgess-Bishop J, Murray LR, et al. A community effort to reduce the black/white breast cancer mortality disparity in Chicago. Cancer Causes Control. 2009;20(9):1681–8. 10.1007/s10552-009-9419-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Press R, Carrasquillo O, Sciacca RR, Giardina EG. Racial/ethnic disparities in time to follow-up after an abnormal mammogram. J Women’s Health (2002). 2008;17(6):923–30. 10.1089/jwh.2007.0402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Daly MC, Duncan GJ, McDonough P, Williams DR. Optimal indicators of socioeconomic status for health research. Am J Public Health. 2002;92(7):1151–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hewitt M, Greenfield S, Stovall E. From cancer patient to cancer survivor: lost in transition. National Academies Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Birken SA, Mayer DK, Weiner BJ. Survivorship care plans: prevalence and barriers to use. J Cancer Educ. 2013;28(2):290–6. 10.1007/s13187-013-0469-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Commission on Cancer. Important information regarding CoC Survivorship Care Plan Standard. The American College of Surgeons,, Chicago, IL. https://www.facs.org/quality-programs/cancer/news/survivorship Accessed December 10 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ganz PA, Hewitt M. Implementing cancer survivorship care planning: workshop summary. National Academies Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chan A, Gan YX, Oh SK, Ng T, Shwe M, Chan R, et al. A culturally adapted survivorship programme for Asian early stage breast cancer patients in Singapore: a randomized, controlled trial. Psycho-oncology. 2017;26(10):1654–9. 10.1002/pon.4357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ratjen I, Schafmayer C, Enderle J, di Giuseppe R, Waniek S, Koch M, et al. Health-related quality of life in long-term survivors of colorectal cancer and its association with all-cause mortality: a German cohort study. BMC Cancer. 2018;18(1):1156. 10.1186/s12885-018-5075-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.ASCO. ASCO cancer treatment and survivorship care plans. 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 21.National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Taking charge of follow-up care. 2020. https://www.nccn.org/patients/resources/life_after_cancer/survivorship.aspx. Accessed January 9 2020.

- 22.American Cancer Society. Survivorship Care Plans. 2020. https://www.cancer.org/treatment/survivorship-during-and-after-treatment/survivorship-care-plans.html. Accessed January 9 2020.

- 23.Husain M, Nolan TS, Foy K, Reinbolt R, Grenade C, Lustberg M. An overview of the unique challenges facing African-American breast cancer survivors. Support Care Cancer. 2019;27(3):729–43. 10.1007/s00520-018-4545-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nekhlyudov L, Mollica MA, Jacobsen PB, Mayer DK, Shulman LN, Geiger AM. Developing a quality of cancer survivorship care framework: implications for clinical care, research and policy. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2019;111:1120–30. 10.1093/jnci/djz089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Burke NJ, Napoles TM, Banks PJ, Orenstein FS, Luce JA, Joseph G. Survivorship care plan information needs: perspectives of safety-net breast cancer patients. PLoS One. 2016;11(12):e0168383. 10.1371/journal.pone.0168383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.DeGuzman P, Colliton K, Nail CJ, Keim-Malpass J. Survivorship care plans: rural, low-income breast cancer survivor perspectives. Clin J Oncol Nurs. 2017;21(6):692–8. 10.1188/17.Cjon.692-698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Forsythe LP, Parry C, Alfano CM, Kent EE, Leach CR, Haggstrom DA, et al. Use of survivorship care plans in the United States: associations with survivorship care. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2013;105(20):1579–87. 10.1093/jnci/djt258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rutledge TL, Kano M, Guest D, Sussman A, Kinney AY. Optimizing endometrial cancer follow-up and survivorship care for rural and other underserved women: patient and provider perspectives. Gynecol Oncol. 2017;145(2):334–9. 10.1016/j.ygyno.2017.03.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.American College of Surgeons. Optimal Resources for Cancer Care. Chicago, IL: 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Johnson RL, Roter D, Powe NR, Cooper LA. Patient race/ethnicity and quality of patient–physician communication during medical visits. Am J Public Health. 2004;94(12):2084–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schouten BC, Meeuwesen L. Cultural differences in medical communication: a review of the literature. Patient Educ Couns. 2006;64(1-3):21–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Moreno PI, Ramirez AG, San Miguel-Majors SL, Castillo L, Fox RS, Gallion KJ, et al. Unmet supportive care needs in Hispanic/ Latino cancer survivors: prevalence and associations with patient-provider communication, satisfaction with cancer care, and symptom burden. Support Care Cancer. 2019;27(4):1383–94. 10.1007/s00520-018-4426-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.de Rooij BH, Park ER, Perez GK, Rabin J, Quain KM, Dizon DS, et al. Cluster analysis demonstrates the need to individualize care for cancer survivors. Oncologist. 2018;23(12):1474–81. 10.1634/theoncologist.2017-0558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Butow PN, Phillips F, Schweder J, White K, Underhill C, Goldstein D. Psychosocial well-being and supportive care needs of cancer patients living in urban and rural/regional areas: a systematic review. Support Care Cancer. 2012;20(1):1–22. 10.1007/s00520-011-1270-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Beaupin LK, Uwazurike OC, Hydeman JA. A roadmap to survivorship: optimizing survivorship care plans for adolescent and young adult cancer survivors. J Adolesc Young Adult Oncol. 2018;7:660–5. 10.1089/jayao.2018.0061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Birken SA, Clary AS, Bernstein S, Bolton J, Tardif-Douglin M, Mayer DK, et al. Strategies for successful survivorship care plan implementation: results from a qualitative study. J Oncol Pract. 2018;14(8):e462–e83. 10.1200/jop.17.00054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Baravelli C, Krishnasamy M, Pezaro C, Schofield P, Lotfi-Jam K, Rogers M, et al. The views of bowel cancer survivors and health care professionals regarding survivorship care plans and post treatment follow up. J Cancer Survivorship : Res Pract 2009;3(2):99– 108. 10.1007/s11764-009-0086-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.LaGrandeur W, Armin J, Howe CL, Ali-Akbarian L. Survivorship care plan outcomes for primary care physicians, cancer survivors, and systems: a scoping review. J Cancer Survivorship : Res Pract 2018;12(3):334–47. 10.1007/s11764-017-0673-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Taylor K, Monterosso L. Survivorship care plans and treatment summaries in adult patients with hematologic cancer: an integrative literature review. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2015;42(3):283–91. 10.1188/15.Onf.283-291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mayer DK, Birken SA, Check DK, Chen RC. Summing it up: an integrative review of studies of cancer survivorship care plans (2006-2013). Cancer. 2015;121(7):978–96. 10.1002/cncr.28884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hill RE, Wakefield CE, Cohn RJ, Fardell JE, Brierley ME, Kothe E, et al. Survivorship care plans in cancer: a meta-analysis and systematic review of care plan outcomes. Oncologist. 2019. 10.1634/theoncologist.2019-0184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Klemanski DL, Browning KK, Kue J. Survivorship care plan preferences of cancer survivors and health care providers: a systematic review and quality appraisal of the evidence. J Cancer Survivorship: Res Pract. 2016;10(1):71–86. 10.1007/s11764-015-0452-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151(4):264–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Veritas Health Innovation. Covidence systematic review software. Melbourne, Australia. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Porritt K, Gomersall J, Lockwood C. JBI’s systematic reviews: study selection and critical appraisal. Am J Nursing. 2014;114(6): 47–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.National Heart Lung and Blood Institute. Study Quality Assessment Tools U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health-topics/study-quality-assessment-tools. Accessed August 5 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yilmaz NG, Schouten BC, Schinkel S, van Weert JCM. Information and participation preferences and needs of non-Western ethnic minority cancer patients and survivors: a systematic review of the literature. Patient Educ Couns. 2019;102(4):631–50. 10.1016/j.pec.2018.11.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Dixon-Woods M, Agarwal S, Jones D, Young B, Sutton A. Synthesising qualitative and quantitative evidence: a review of possible methods. J Health Services Res Pol. 2005;10(1):45–53. 10.1177/135581960501000110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ashing-Giwa K, Tapp C, Brown S, Fulcher G, Smith J, Mitchell E, et al. Are survivorship care plans responsive to African-American breast cancer survivors?: voices of survivors and advocates. J Cancer Surviv. 2013;7(3):283–91. 10.1007/s11764-013-0270-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ashing K, Serrano M, Weitzel J, Lai L, Paz B, Vargas R. Towards developing a bilingual treatment summary and survivorship care plan responsive to Spanish language preferred breast cancer survivors. J Cancer Surviv. 2014;8(4):580–94. 10.1007/s11764-014-0363-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Burg MA, Lopez ED, Dailey A, Keller ME, Prendergast B. The potential of survivorship care plans in primary care follow-up of minority breast cancer patients. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24(Suppl 2):S467–71. 10.1007/s11606-009-1012-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Casillas J, Syrjala KL, Ganz PA, Hammond E, Marcus AC, Moss KM, et al. How confident are young adult cancer survivors in managing their survivorship care? A report from the LIVESTRONG Survivorship Center of Excellence Network. J Cancer Survivorship : Res Pract 2011;5(4):371–81. 10.1007/s11764-011-0199-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Greenlee H, Molmenti C, Crew K, Awad D, Kalinsky K, Brafman L, et al. Survivorship care plans and adherence to lifestyle recommendations among breast cancer survivors. J Cancer Surviv. 2016;10(6):956–63. 10.1007/s11764-016-0541-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hershman DLGH, Awad D, Kalinsky K, Maurer M, Kranwinkel G, Brafman L, et al. Randomized controlled trial of a clinic-based survivorship intervention following adjuvant therapy in breast cancer survivors. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2013;138(3):795–806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]