Abstract

Objective:

Reduced subchondral bone mass and increased remodeling are associated with early stage OA. However, the direct effect of low subchondral bone mass on the risk and severity of OA development is unclear. We sought to determine the role of low bone mass resulting from a bone-specific loss of estrogen signaling in load-induced OA development using female osteoblast-specific estrogen receptor-alpha knockout (pOC-ERαKO) mice.

Methods:

Osteoarthritis was induced by cyclic mechanical loading applied to the left tibia of 26-week-old female pOC-ERαKO and littermate control mice at peak loads of 6.5N, 7N, or 9N for 2 weeks. Cartilage damage and thickness, osteophyte development, and joint capsule fibrosis were assessed from histological sections. Subchondral bone morphology was analyzed by microCT. The correlation between OA severity and intrinsic bone parameters was determined.

Results:

The loss of ERα in bone resulted in an osteopenic subchondral bone phenotype, but did not directly affect cartilage health. Following two weeks of cyclic tibial loading to induce OA pathology, pOC-ERαKO mice developed more severe cartilage damage, larger osteophytes, and greater joint capsule fibrosis compared to littermate controls. Intrinsic bone parameters negatively correlated with measures of OA severity in loaded limbs.

Conclusions:

Subchondral bone osteopenia resulting from bone-specific loss of estrogen signaling was associated with increased severity of load-induced OA pathology, suggesting that reduced subchondral bone mass directly exacerbates load-induced OA development. Bone-specific changes associated with estrogen loss may contribute to the increased incidence of OA in post-menopausal women.

Keywords: osteoarthritis, subchondral bone, estrogen, preclinical studies

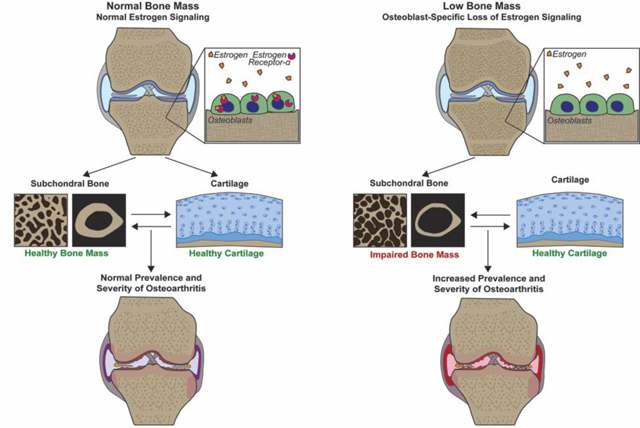

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

Osteoarthritis (OA) is a degenerative joint disease causing progressive cartilage damage, subchondral bone alterations, and osteophyte development. Late stage OA is associated with subchondral bone sclerosis and increased subchondral bone mass, suggesting that the biomechanical crosstalk between cartilage and subchondral bone plays an important role in OA progression [1]; however, the relationship between subchondral bone mass and OA development remains unclear. High subchondral bone mass and stiffness have long been hypothesized to increase stress on cartilage and, therefore, increase OA development [2]. In several more recent studies, subchondral plate thickening alone was insufficient to increase OA development without associated increases in subchondral bone remodeling, suggesting that increased remodeling, and not high bone mass, may be responsible for increased OA risk [3–5]. Early stage OA is associated with decreased subchondral bone mass resulting from increased bone resorption following OA intiation [6–9]; however, the role of reduced subchondral bone mass in OA development and progression also remains unclear. Low subchondral bone mass prior to OA initiation could also alter OA susceptibility and progression independent of increased bone resorption or remodeling.

Results from clinical studies are conflicting regarding the link between low subchondral bone mass (osteoporosis) and OA [10,11]. Multiple studies have suggested that osteoporotic patients have a decreased risk of OA development [11,12], while others observed no relationship between the two diseases [13,14]. Amongst a subset of patients with both osteoporosis and OA, decreased subchondral bone mass and increased remodeling positively correlated to OA severity [15]. In a number of preclinical studies, similar trends regarding low subchondral bone mass and high levels of subchondral bone remodeling increasing OA development have been observed [16–20]. Thus, both low subchondral bone mass and high levels of subchondral bone remodeling are associated with increased OA severity, but the specific contribution of low bone mass compared to remodeling is unclear.

Estrogen loss with menopause is associated with both decreased bone mass and increased OA development [21,22]. Many studies examining the role of low bone mass in OA development use surgically-induced menopause via ovariectomy (OVX) to decrease subchondral bone mass [16–20]. OVX significantly increases the severity and rate of OA development in a variety of preclinical models, in addition to both decreasing subchondral bone mass and increasing remodeling [16–20], suggesting that low subchondral bone mass and increased subchondral bone remodeling associated with global estrogen loss may exacerbate OA. However, estrogen has both anti-catabolic and anabolic effects on cartilage in studies examining in vitro estrogen supplementation to chondrocytes [23–27]. Currently it is unclear whether osteoarthritic cartilage damage associated with menopause results directly from loss of estrogen signaling in cartilage or occurs secondary to decreased bone mass and increased bone resorption.

To directly examine the role of low subchondral bone mass in OA development, we isolated decreased bone mass associated with loss of estrogen signaling from the detrimental cartilage changes occurring with a systemic loss of estrogen. Mature osteoblast-specific estrogen receptor-α (ERα) knockout (pOC-ERαKO) mice generated by use of an osteocalcin-Cre [28–30] provide a targeted in vivo model with which to study the impact of low bone mass resulting from bone-specific loss of estrogen signaling on OA development. Through crossing these mice with Rosa26-Cre reporter mice, we and others have previously demonstrated osteocalcin-Cre expression is limited to mature osteoblasts, osteocytes, and a portion of hypertrophic chondrocytes within the growth plate but not articular chondrocytes [28,31,32], demonstrating that the osteocalcin-Cre model does not directly target articular cartilage. Because pOC-ERαKO also do not have altered serum estrogen (E2) levels [28], this mouse model provides an opportunity to examine the direct effect of low subchondral bone mass on OA development without associated estrogen effects on cartilage. In addition, we previously demonstrated similar levels of bone resorption in pOC-ERαKO mice compared to their littermate controls despite reduced bone mass [28,29], allowing us to isolate the effects of low subchondral bone mass from increased subchondral bone resorption using this mouse model. Here, we determined the effect of low subchondral bone mass resulting from estrogen deficiency on the severity of load-induced OA. We subjected female pOC-ERαKO and littermate control (LC) mice to an established model of cyclic tibial compression to initiate OA development [33–36]. We hypothesized that pOC-ERαKO mice would develop more severe OA with mechanical loading compared to LC mice and that differences in OA severity would correlate with differences in initial subchondral bone properties.

Materials and Methods

Generation of osteoblast-specific ERαKO mice

LC and pOC-ERαKO mice were bred, validated, and genotyped as previously described [28,29]. Briefly, mice with a transgene encoding Cre recombinase driven by the human osteocalcin promoter (OC-Cre, provided by Dr. Thomas Clemens, The Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, MD) [37,38] were crossed with mice in which loxP sequences flanked exon 3 of the DNA-binding domain of the ERα gene (Esr1) (ERαfl/fl, provided by Dr. Kahn, University of Cincinnati, Cincinnati, OH) [39]. ERαfl/fl mice were inbred to be >99% pure C57Bl/6 by speed congenics before generation of ERαKO (DartMouse Speed Congenic Core Facility, Geisel School of Medicine at Dartmouth, Hanover, NH). Mice were genotyped as described [28]. Mice were housed 3–5 per cage with ad libitum access to food and water (fed a standard diet, Teklad LM-485). All experimental procedures were approved by the Cornell University IACUC.

Cyclic Mechanical Loading

Applied load magnitudes and bone stiffness for each genotype were determined from in vivo diaphyseal strains as previously described [40–42]. Single-element strain gauges (EA-06–015LA-120, Micro-Measurements, Wendell, NC) were surgically attached to the medial surface of the tibial midshafts of female 26-week-old LC and pOC-ERαKO mice (n = 4–5 per genotype). Cyclic compressive loads ranging from −2 to −13N peak load magnitude were applied to the left and right tibiae in our custom tibial-loading device, and bone stiffness was calculated [40,41]. Whole bone stiffness was similar between LC and pOC-ERαKO mice (0.00677 ± 0.0028N/με LC, 0.00705 ± 0.0043N/με pOC-ERαKO; mean ± SD).

Cyclic compressive loading applied to the left tibiae of female 26-week-old LC and pOC-ERαKO mice at peak load magnitudes of 6.5N (LC: n=8, pOC-ERαKO: n=8), 7N (LC: n=6, pOC-ERαKO: n=7) or 9N (LC: n=6, pOC-ERαKO: n=6) for two weeks (41 mice total, Fig.2A–C) [33,35,36]. Peak load magnitude of 6.5N corresponded to approximately +1000 microstrain (με) at the tibial midshaft, while a peak load magnitude of 9N corresponded to approximately +1200 με [42]. Right limbs served as contralateral controls. Mice were placed under general anesthesia during loading (2% isoflurane, 1.0L/min, Webster). Loading was applied to the left tibiae at 4Hz for 1200 cycles (5 min) per day, 5 days per week [33]. Following completion of the two-week loading period, mice were euthanized. Knee joints were harvested and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde overnight at 4° C.

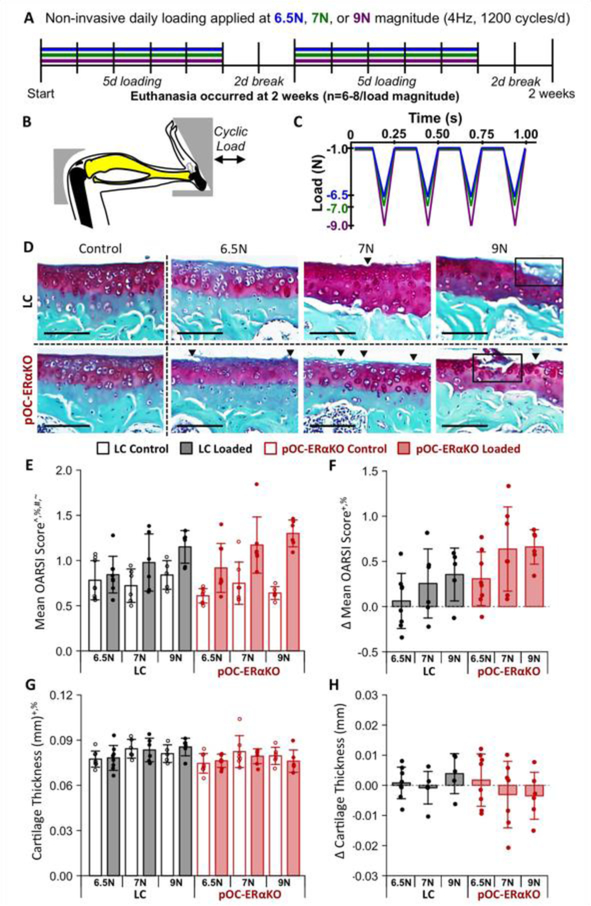

Figure 2.

Load-induced cartilage degradation was greater in pOC-ERαKO mice. (A) Overview of experimental design. (B) Schematic of mouse tibial loading configuration. (C) In vivo loading waveform. (D) Surface fibrillations (arrowheads) and cartilage erosions (boxes) occurred in both genotypes. Scale bar: 100μm. (E) Cartilage damage score increased with loading. (F) Load-induced increase in cartilage damage was greater in pOC-ERαKO mice. (G) Cartilage was slightly thinner in pOC-ERαKO mice when control and loaded limbs were pooled. (H) Loading did not affect cartilage thickness. Bars indicate mean ± standard deviation. Individual data points (n=6–8/group) are overlaid. Δ indicates difference between loaded and control limb measures within a single animal. p<0.05 indicated on vertical axis for effects of ^Load, +Genotype, %Magnitude, #Load×Genotype, ~Load×Magnitude, &Genotype×Magnitude, $Load×Genotype×Magnitude.

Microcomputed Tomography

Microcomputed tomography (microCT) scans were used to assess bone morphological differences between genotypes and changes in response to loading. After fixation, tissues were transferred to 70% ethanol. Intact knee joints were scanned using microCT, with an isotropic voxel resolution of 10 μm (μCT35, Scanco, Bruttisellen, Switzerland; 55kVp, 145μA, 600ms integration time) [43]. In all regions, bone was isolated by manually contouring the desired volume of interest (VOI). Thickness of the subchondral cortical plate was measured (SCB.Th). The VOI for the subchondral bone plate included the region of cortical bone beginning at the proximal end of the tibia and extended distally to the start of the cancellous bone in the epiphysis. Bone volume fraction was assessed in the metaphysis (distal to the growth plate) and epiphysis (proximal to the growth plate). The VOI for the metaphysis started distal to the growth plate and extended 10% of the tibia length excluding cortical bone. The epiphysis included cancellous bone distal to the subchondral plate and proximal to the growth plate.

Histological Analysis

Following microCT scanning, knee joints were decalcified in 10% EDTA for two weeks, dehydrated in an ethanol gradient, and embedded in paraffin for histological analysis. Coronal sections of 6μm thickness were obtained from posterior to anterior using a rotary microtome (Leica RM2255, Wetzlar, Germany). Cartilage damage was assessed with Safranin O/Fast Green stained slides of the medial and lateral tibial plateaus at 90μm intervals throughout the joint using histological scoring performed by a blinded researcher. A modified Mankin scoring system was used in the non-loaded control limbs to assess phenotypic differences in cartilage cellularity and composition [44]. The OARSI scoring system was used to evaluate structural cartilage damage in both loaded and control limbs [45]. Histological scores are reported as a whole joint average. Cartilage thickness was measured on three representative sections (posterior, middle, and anterior) on both medial and lateral tibial plateaus as previously described [33] and is reported as a whole joint average.

Medial tibial osteophyte formation was assessed from Safranin-O/Fast Green stained sections. The slide from each joint containing the largest portion of the medial tibial osteophyte was assessed. Osteophyte size was defined as the medial-lateral width of the osteophyte at its widest point, measured from the medial edge of the epiphysis to the edge of the ectopic bone. Osteophyte maturity was scored on a scale of 0 to 3 (0=no osteophyte, 1=primarily cartilaginous, 2=mixture of cartilage and bone, or 3=primarily bony structure) as previously described [46].

Synovium and joint capsule thickness and cellularity were examined using three representative haematoxylin and eosin (H&E) stained sections (posterior, middle, and anterior). Both the synovium and joint capsule were visually assessed for thickness and cellularity changes. The pathology of the joint capsule and synovium were subjectively compared between genotypes and load magnitudes.

Osteoclast number was quantified using two representative tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase (TRAP)-stained sections as previously described[28]. The number of positively-stained osteoclasts in the cancellous metaphysis of the tibia was quantified and normalized to bone surface (2 slides per limb, OsteomeasureXP v3.2.1.7).

Regression Analysis

Correlation and multiple regression analyses were conducted to examine the relationship between intrinsic bone parameters (non-loaded limb SCB plate thickness, epiphyseal BV/TV and metaphyseal BV/TV) and the severity of OA development with loading (loaded limb OARSI score and osteophyte size in loaded limbs with osteophytes). Pearson’s correlation coefficient was determined to establish bivariate relationships between each bone parameter and OA measure. Multiple regression models were constructed to determine the combination of bone parameters that was most predictive of OA severity. Stepwise regression of variables was used to develop predictive models of OARSI score or osteophyte size in loaded limbs from non-loaded control limb anatomical parameters and load magnitude. The exclusion criterion for variables in the model was p>0.10 and model significance was set at p<0.05.

Statistical Analysis

Histological scores, cartilage thickness, and bone parameters of LC and pOC-ERαKO non-loaded control limbs were compared using a Student’s t-test. Non-loaded control limbs from 6.5N, 7N, and 9N groups were pooled for each genotype for phenotype analysis. The effects of loading, load magnitude, and genotype were determined using a linear mixed-effects model with fixed effects of loading (control vs. loaded), load magnitude (6.5N vs. 7N vs. 9N) and genotype (LC vs. pOC-ERαKO), and a random mouse effect. Post-hoc analysis was performed using Tukey’s test for significant interaction effects and t-test for individual effects. Significance was set at p<0.05.

Results

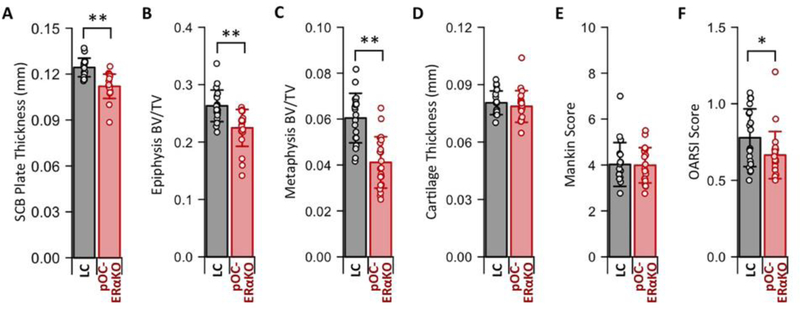

pOC-ERαKO Developed Osteopenic Subchondral Bone Phenotype

Due to the lack estrogen signaling specifically in bone, pOC-ERαKO mice should exhibit an altered bone but not cartilage phenotype when compared to their littermate controls (LC). To assess the phenotypic differences resulting from a bone-specific loss of estrogen signaling, we first examined bone and cartilage in non-loaded contralateral control limbs. Consistent with our previous work in younger mice [28,29], pOC-ERαKO mice developed an osteopenic phenotype with decreased cortical and cancellous bone mass in the proximal tibia. Control limbs in pOC-ERαKO mice had a thinner subchondral plate (p<0.001, Fig. 1A) and lower bone volume fraction (BV/TV) in the epiphysis (p<0.001, Fig. 1B) and metaphysis (p<0.001, Fig. 1C) relative to LC mice. In contrast, the cartilage phenotype was similar between genotypes. Control limb cartilage thickness was not different between genotypes (p=0.413, Fig. 1D). Control limb cartilage composition and cellularity, assessed by modified Mankin score[44], were not affected by ERα deletion (p=0.893, Fig. 1E). Cartilage structure in contralateral control limbs, assessed by OARSI score [45], was improved in pOC-ERαKO mice, indicating a more pristine cartilage surface with less fibrillation (p=0.043, Fig. 1F). Weight (p=0.204) and tibial length (p=0.179) were not different between genotypes. Bone-specific lack of estrogen signaling induced subchondral bone osteopenia but did not significantly alter cartilage phenotype.

Figure 1.

pOC-ERαKO resulted in an osteopenic subchondral bone phenotype and a minimal indirect effect on cartilage phenotype. (A) Control limb subchondral bone (SCB) plate thickness, (B) epiphyseal BV/TV, and (C) metaphyseal BV/TV were decreased in pOC-ERαKO. (D) Control limb cartilage thickness and (E) Mankin score were not different between genotypes. (F) Control limb OARSI score was decreased in pOC-ERαKO. Bars indicate mean ± standard deviation. Individual data points (n=20–21/group) are overlaid. *p<0.05 and **p<0.001.

Load-Induced Cartilage Damage Greater in pOC-ERαKO

To determine if load-induced OA development was altered by low subchondral bone mass induced by bone-specific loss of estrogen signaling, we applied mechanical loading to the left tibia of mice to induce OA (Fig. 2A–C). Different load magnitudes ranging from moderate-(6.5N and 7N) to high-level (9N) loads were used to determine how pOC-ERαKO affected the rate of OA development. Two weeks of loading induced cartilage damage at all load magnitudes in both genotypes (p<0.001, Fig. 2D,E). Cartilage damage was greater in pOC-ERαKO compared to LC (p= 0.008) and increased with load magnitude (p=0.029, Fig. 2F). Surface fibrillations were present in both genotypes at 6.5N and 7N load levels. Vertical clefts into cartilage and erosions of the articular surface occurred at the 9N load. Cartilage degradation occurred in both the medial and lateral tibial plateaus, with increased damage present in the lateral plateau.

pOC-ERαKO mice had slightly thinner articular cartilage compared to LC when pooled across loaded and control limbs (p=0.046, Fig. 2G). Mechanical loading did not alter cartilage thickness (p=0.935), and the effect of loading was similar between genotypes (p=0.233, Fig. 2H). Loading did not cause changes in localized cartilage thickness in any region of the tibial plateau. Overall, low subchondral bone mass from lack of estrogen signaling in bone correlated with more severe load-induced cartilage damage, but did not alter load-induced changes in cartilage thickness.

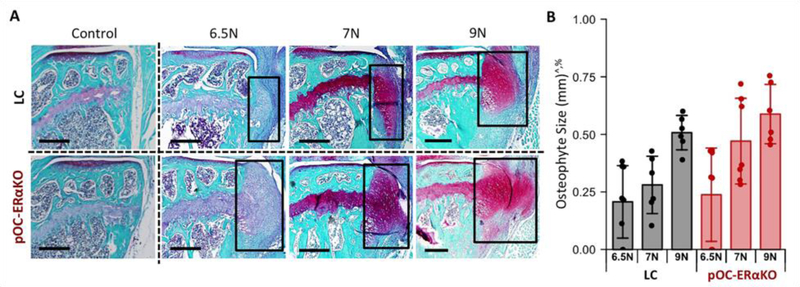

Load-Induced Osteophyte Formation Increased in pOC-ERαKO

Next, we assessed osteophyte formation to determine if the bone-specific loss of estrogen signaling also altered ectopic bone formation resulting from load-induced OA progression. Medial tibial osteophytes formed with loading in both genotypes (Fig. 3A). Osteophyte size increased with load magnitude (p<0.001, Fig. 3A,B). Osteophytes were present in all 7N and 9N loaded limbs of both genotypes. At the 6.5N load, 6 of 8 loaded limbs in LC mice and 5 of 8 loaded limbs in pOC-ERαKO mice developed osteophytes. No osteophytes were present in control limbs. Osteophytes were significantly larger in pOC-ERαKO mice (p=0.048, Fig. 3B). Osteophyte maturity was not different between genotypes (p=0.418), and the majority of osteophytes were cartilaginous after two weeks of loading. Low subchondral bone mass resulting from lack of estrogen signaling in bone corresponded to increased osteophyte formation following cyclic tibial loading to induce OA development.

Figure 3.

Osteophyte formation with loading was greater in pOC-ERαKO mice. (A) Representative images of medial tibial osteophytes. Scale bar: 300μm. (B) Osteophytes were larger in loaded limbs of pOC-ERαKO mice. Bars indicate mean ± standard deviation. Individual data points (n=6–8/group) are overlaid. p<0.05 indicated on vertical axis for effects of ^Load, +Genotype, %Magnitude, #Load×Genotype, ~Load×Magnitude, &Genotype×Magnitude, $Load×Genotype×Magnitude.

Load-Induced Joint Capsule Fibrosis Greater in pOC-ERαKO

To assess if the local inflammatory environment of the joint was also influenced by the bone-specific loss of estrogen signaling, we assessed synovium and joint capsule pathology resulting from load-induced OA progression. At all load magnitudes, we saw minimal to low-level synovial thickening and cellularity changes, indicating little synovitis development following two weeks of mechanical loading. However, mechanical loading caused joint capsule thickening and fibrosis at 6.5N, 7N, and 9N load levels in both genotypes (Fig. S1). Visually pOC-ERαKO mice appeared to have greater joint capsule fibrosis with loading compared to LC. Increased severity of joint capsule fibrotic response occurred with increased load magnitude. A moderate increase in joint capsule thickness and early stages of fibrosis occurred at 6.5N. At 7N, a moderate to severe increase in joint capsule thickness and fibrosis was observed. Both joint capsule thickness and fibrosis were severely increased with 9N loading. Bone-specific lack of estrogen signaling was associated with increased joint capsule fibrosis following cyclic tibial loading.

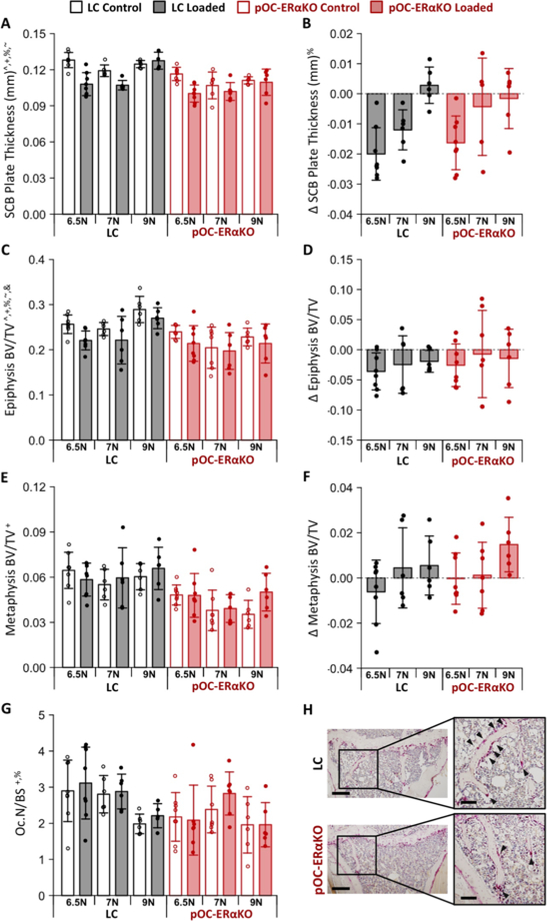

Load-Induced Bone Changes Similar in pOC-ERαKO and LC

We assessed subchondral bone morphology to determine the effect of the absence of estrogen signaling in bone on the load-induced adaptation. Subchondral cortical plate thickness was lower in pOC-ERαKO mice compared to LC (p<0.001, Fig. 4A) and decreased with mechanical loading in a load magnitude-dependent manner (p<0.001, Fig. 4B). Subchondral plate thickness was reduced with loading at both 6.5N and 7N load magnitudes when pooling across genotypes, but was not changed at the 9N load. Load-induced changes did not differ between genotypes (p=0.490). Epiphyseal cancellous BV/TV was lower in pOC-ERαKO mice compared to LC (p<0.001, Fig. 4C) and decreased with mechanical loading (p=0.004, Fig. 4D). Load-induced changes in epiphyseal BV/TV were not different between genotypes (p=0.450) or with load magnitude (p=0.609). Metaphyseal cancellous BV/TV was also lower in pOC-ERαKO mice (p<0.001, Fig. 4E) but was not affected by loading (p=0.141, Fig. 4F).

Figure 4.

Subchondral bone mass was decreased in pOC-ERαKO mice. (A) Subchondral bone plate was thinner in pOC-ERαKO mice. (B) Loading decreased Subchondral bone plate thickness. (C) Epiphyseal BV/TV was lower in pOC-ERαKO mice. (D) Loading decreased epiphyseal BV/TV. (E) Metaphyseal BV/TV was lower in pOC-ERαKO mice. (F) Loading had no effect on metaphyseal BV/TV. (G) Osteoclast number normalized to bone surface was lower in pOC-ERαKO. (H) Representative TRAP stained sections show fewer osteoclasts in pOC-ERαKO mice. Scale bar: 300μm, inlay: 100μm. Bars indicate mean ± standard deviation. Individual data points (n=6–8/group) are overlaid. Δ indicates difference between loaded and control limb measures within a single animal. p<0.05 indicated on vertical axis for effects of ^Load, +Genotype, %Magnitude, #Load×Genotype, ~Load×Magnitude, &Genotype×Magnitude, $Load×Genotype×Magnitude.

Finally, to determine if the bone-specific loss of estrogen signaling altered bone resorption during load-induced OA development, we quantified the presence of osteoclasts. pOC-ERαKO mice had reduced osteoclast numbers normalized to bone surface (p=0.0083, Fig. 4G,H). Osteoclast number was not different with loading (p=0.320). Overall, bone specific lack of estrogen signaling was associated with decreased subchondral bone mass and osteoclast numbers, but did not alter subchondral bone response to loading.

Subchondral Bone Mass Negatively Correlated to OA Severity

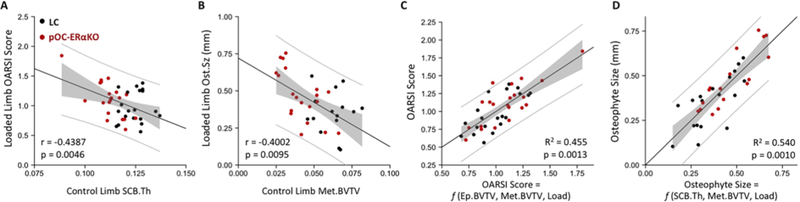

Correlation analyses were performed to examine the relationship between the severity of OA development (loaded limb OARSI score and osteophyte size) and intrinsic subchondral bone properties (control limb subchondral bone morphology) (Fig. 5A–B). OARSI score was negatively correlated to subchondral plate thickness (r=−0.439, p=0.005), and osteophyte size was negatively correlated to metaphyseal BV/TV (r=−0.400, p=0.010).

Figure 5.

Low subchondral bone mass correlated to increased OA severity. (A) OARSI score negatively correlated to subchondral plate thickness. (B) Osteophyte size negatively correlated to metaphysis BV/TV. (C) Multiple linear regression fit for OARSI score predicted by epiphyseal BV/TV, metaphyseal BV/TV, and load magnitude. (D) Multiple linear regression regression fit for osteophyte size predicted by subchondral plate thickness, metaphyseal BV/TV, and load magnitude. Regression line is black, 95% confidence interval of regression line is shaded gray and 95% prediction interval is indicated by the gray lines.

Multiple regression analyses were used to understand whether combinations of bone parameters predicted variation in OA severity (Fig. 5C–D). Combined epiphyseal BV/TV, metaphyseal BV/TV and load magnitude explained 45% of variability in OARSI score (R2=0.455, p=0.001, Table S1A). Combined subchondral plate thickness, metaphyseal BV/TV and load magnitude explained 54% of variability in osteophyte size (R2=0.548, p=0.008, Table S1B).

Discussion

To determine the role of low subchondral bone mass on OA development, we examined the effect of subchondral bone osteopenia induced by a bone-specific loss of estrogen signaling on load-induced OA development. As expected, the absence of estrogen signaling in bone led to decreased subchondral bone mass and the development of osteopenia. pOC-ERαKO mice also had decreased osteoclast presence, indicating reduced baseline levels of bone resorption in contrast to increased resorption observed following global estrogen loss [16–20]. In addition, a small but significant genotype difference was observed in baseline cartilage. Osteoblast-specific ERαKO mice had slightly smoother cartilage in non-loaded limbs compared to LC mice, counter to the direct detrimental effects lack of estrogen has on cartilage [24,26,27]. The development of an osteopenic subchondral bone phenotype without an associated increase in bone resorption or detrimental changes in cartilage indicates the pOC-ERαKO mouse is an improved model to more directly examine the effect of low subchondral bone mass on OA development compared to global estrogen deficiency.

Subchondral bone osteopenia was associated with more severe load-induced OA pathology, consistent with previous studies examining the effects of low bone mass induced via OVX on OA development [17–20] despite low levels of bone remodeling and healthy cartilage metabolism in pOC-ERαKO mice. Although the pOC-ERαKO mouse model was unable to completely isolate the effects of low bone mass due to genotypic differences in baseline cartilage health and bone resorption, both genotypic differences outside of reduced subchondral bone mass would most likely lead to the pOC-ERαKO mice being more resistant to load-induced OA damage rather than more susceptible. The vast majority of studies examining subchondral bone resorption in relation to OA indicate that reduced resorption attenuates OA development [47–53] or has no effect on OA severity [54–57]. Despite a reduction in bone resorption and subtle improvements in baseline cartilage health within the pOC-ERαKO mice, more severe load-induced joint damage developed in the pOC-ERαKO mice relative to LC mice. These findings suggest that, while outside of bone mass additional genotypic effects may contribute to the severity of OA development following loading, reduced bone mass within the pOC-ERαKO mice is likely the dominant effect, driving the differences in OA severity observed between genotypes.

To quantitatively assess the role of subchondral bone mass in OA severity, we examined the relationship between intrinsic subchondral bone mass and load-induced OA severity. Subchondral bone mass negatively correlated with measures of OA severity in loaded limbs across both mouse genotypes. Regression models that included multiple intrinsic bone parameters and accounted for load magnitude were highly explanatory for both cartilage damage and osteophyte development, further demonstrating the role of subchondral bone mass in determining the severity of OA development. Both preclinical and clinical studies examining the role of low bone mass in OA development have demonstrated similar negative correlations between subchondral bone mass and OA severity [15,18,19]. However, in these studies OA severity strongly correlated to increased bone remodeling parameters [15,18,19], and did not distinguish between the roles of low subchondral bone mass prior to OA initiation and reduced bone mass resulting from increased remodeling and resorption occurring as a result of OA development. Given that our correlation analysis used the bone parameters of non-loaded control limbs, our results indicate that low intrinsic subchondral bone mass leads to increased load-induced OA severity independent of bone remodeling changes associated with OA development and progression.

Our results suggest that subchondral bone osteopenia was sufficient to increase OA development without associated increases in bone remodeling and resorption. Subchondral bone changes corresponding with load-induced OA development were similar between pOC-ERαKO and LC mice. Subchondral plate thickness and bone volume fraction in the epiphysis decreased with loading similarly in both pOC-ERαKO and LC mice. An initial decrease in subchondral plate thickness occurred in less severe stages of OA (6.5N), followed by subchondral plate thickening in more severe stages of OA (9N). This pattern in subchondral bone changes has been demonstrated in the progression of post-traumatic OA [58]. In addition, loading did not alter bone resorption in either pOC-ERαKO or LC mice, although pOC-ERαKO mice did have a systemic decrease in the presence of osteoclasts relative to LC mice across both loaded and control limbs. In previous studies increased subchondral bone mass alone did not alter OA development without associated increases in subchondral bone resorption and remodeling, indicating that increased remodeling, not low subchondral bone mass, may drive more severe OA development [3–5]. In contrast, in the present study decreased subchondral bone mass without an associated increase in bone resorption led to more severe OA development, suggesting that low intrinsic subchondral bone mass directly increased OA risk.

Mechanical crosstalk between cartilage and subchondral bone may be an important factor in low bone mass leading to increased OA development. Lower bone mass in the epiphysis and thinning of the subchondral plate will reduce the stiffness of subchondral bone. Reduced subchondral bone stiffness could increase osteochondral deformation during cyclic loading, altering stresses transmitted to cartilage and ultimately lead to increased cartilage degeneration. In addition, molecular crosstalk between subchondral bone and cartilage is an important factor in OA initiation and progression [1]. Alterations in molecular signaling between bone and cartilage likely result from both decreased subchondral bone mass and lack of estrogen signaling in bone, and may influence OA development. By demonstrating that alterations in estrogen signaling specific to bone can lead to increased cartilage damage following OA initiation, our results highlight the importance of crosstalk between bone and cartilage in OA disease mechanism.

Global estrogen loss via OVX similarly increases OA severity and decreases subchondral bone mass in a variety of preclinical OA models [17–20,59]. We observed a synergistic relationship between joint mechanical loading, bone-specific lack of estrogen signaling, cartilage damage, and joint capsule fibrosis. OVX and mechanical loading via excessive treadmill running also synergistically exacerbated cartilage damage and synovial thickening, whereas OVX alone decreased subchondral bone mass but did not directly affect cartilage damage [60]. Together, these results indicate that both global and bone-specific loss of estrogen signaling interact synergistically with mechanical loading to increase the severity of OA development, but do not directly cause structural cartilage damage or joint capsule changes without an initiating event. The similarities between our results and those from global estrogen loss suggest that bone-specific changes resulting from estrogen loss, rather than the direct effect of estrogen loss on cartilage metabolism, may be a driving factor in increased OA severity following menopause.

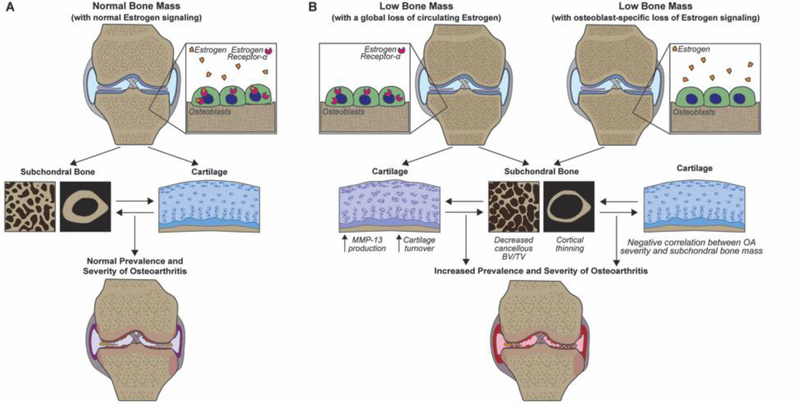

Based on the findings of the current study, we developed a post-menopausal OA model in which low bone mass resulting from bone-specific loss of estrogen signaling contributes to the increased OA severity associated with global estrogen loss and increased incidence of OA in post-menopausal women (Fig. 6). Our regression analysis demonstrating low subchondral bone mass correlates to increased OA severity supports our proposed model in which low subchondral bone mass resulting from bone-specific loss of estrogen signaling directly contributes to the increased OA severity associated with menopause. Additional studies would be needed to validate the proposed model and address limitations in the current study. Menopause and estrogen deficiency have complex direct and indirect effects across a variety of joint tissues, in addition to potentially altering the inflammatory environment in the joint [61]. The current study demonstrates that subchondral bone loss associated with lack of estrogen signaling specific to bone is sufficient to lead to increase OA development, as illustrated in the proposed model, but does not rule out the direct or indirect effects of global estrogen loss on cartilage, other joint tissues, or the interactions between these tissues on further increasing OA progression. Future work should further investigate the mechanical and molecular crosstalk between subchondral bone, cartilage, and other joint tissues with loading to better understand how low a lack of estrogen signaling in bone may affect protein and gene expression and crosstalk throughout the joint. Furthermore, future work should closely examine the presence of inflammatory cells within the joint following loading in both genotypes to better understand the role of localized inflammation on the level of joint damage. In addition, comparing load-induced OA severity between OVX mice with a global loss of estrogen signaling and bone-specific and cartilage specific ERαKO mice[59] would allow a better understanding of the relative roles of estrogen loss from bone and cartilage on OA progression.

Figure 6.

Proposed model summarizing the hypothesized effects of low bone mass resulting from global estrogen loss or osteoblast-specific loss of estrogen signaling on OA development. (A) Summary of the effect of normal estrogen signaling on subchondral bone and cartilage in load-induced OA development. (B) Despite different effects on cartilage, global estrogen loss via menopause (or OVX) and the effect of bone-specific loss of estrogen signaling (via conditional ERαKO deletion) both reduce subchondral bone mass, resulting in similarly increased load-induced OA development.

Conclusion

Reduced subchondral bone mass resulting from bone-specific loss of estrogen signaling via osteoblast-specific ERαKO was associated with increased severity of OA pathology following in vivo mechanical loading. Low subchondral bone mass in pOC-ERαKO mice was not associated with increased bone resorption, allowing us to more directly examine the effect of low subchondral bone mass on OA development. Intrinsic subchondral bone mass negatively correlated to OA severity, indicating that individuals with reduced subchondral bone mass may have an increased risk of OA development and increased rate of OA progression. In addition, bone-specific changes associated with loss of estrogen signaling, specifically reduced subchondral bone mass, may directly contribute to the increased incidence of OA observed in women at the onset of menopause, thus highlighting the potential of subchondral bone as a target for OA modifying treatment and prevention in post-menopausal women.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Figure 1. Joint capsule fibrosis and thickening with loading was slightly increased in pOC-ERαKO mice. Representative H&E stained histology images of the joint capsule (JC) insertion to the lateral tibia (LT). Joint capsule thickness and cellularity increased with loading. Scale bar: 500μm, inlay: 200μm.

Supplementary Table 1. Regression models for prediction of OARSI score and osteophyte size. (A) OARSI score predicted by epiphyseal BV/TV, metaphyseal BV/TV, and load. (B) Osteophyte size predicted by subchondral plate thickness, metaphyseal BV/TV, and load. Standardized beta coefficients. ^p<0.1, *p<0.05, **p<0.001.

Highlights:

Loss of ERα from bone reduced subchondral bone mass, but did not alter cartilage

Subchondral bone osteopenia resulting from loss of estrogen signaling in bone was associated with increased OA severity

Subchondral plate thickness was correlated to the severity of cartilage damage following loading

Effects of estrogen loss in bone may directly contribute to post-menopausal OA development

Low bone mass may increase OA risk and exacerbate OA development

Acknowledgments

We thank Mary Goldring, Steve Goldring, Elliott Kim, Andrew Sama, Erin Hudson, Lyudamila Lukashova, Cornell Statistical Consulting, and the Cornell CARE staff. We thank Dr. Thomas Clemens for providing OC-Cre mice and Dr. Sohaib Khan for providing ERαfl/fl mice. Funding provided by NIH R21-AR064034, NIH T32-AR007281, and the Clark Foundation. The sponsors had no role in the writing of the manuscript or in the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Footnotes

Competing Interests:

No author has any conflict of interest surrounding this work. Marjolein van der Meulen has grants/grants pending from NIH, NSF, and DOD, and is an associate editor for the Journal of Bone and Mineral Research.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- [1].Findlay DM, Kuliwaba JS, Bone–cartilage crosstalk: a conversation for understanding osteoarthritis, Bone Res. 4 (2016) 16028. 10.1038/boneres.2016.28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Radin EL, Rose RM, Role of subchondral bone in the initiation and progression of cartilage damage., Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. (1986) 34–40. 10.1097/00003086-198612000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Jia H, Ma X, Wei Y, Tong W, Tower RJ, Chandra A, Wang L, Sun Z, Yang Z, Badar F, Zhang K, Tseng WJ, Kramer I, Kneissel M, Xia Y, Liu XS, Wang JHC, Han L, Enomoto-Iwamoto M, Qin L, Loading-Induced Reduction in Sclerostin as a Mechanism of Subchondral Bone Plate Sclerosis in Mouse Knee Joints During Late-Stage Osteoarthritis, Arthritis Rheumatol. 70 (2018) 230–241. 10.1002/art.40351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Huebner JL, Hanes MA, Beekman B, TeKoppele JM, Kraus VB, A comparative analysis of bone and cartilage metabolism in two strains of guinea-pig with varying degrees of naturally occurring osteoarthritis, Osteoarthr. Cartil. (2002). 10.1053/joca.2002.0821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Burr DB, Utreja A, Editorial: Wnt Signaling Related to Subchondral Bone Density and Cartilage Degradation in Osteoarthritis, Arthritis Rheumatol. 70 (2018) 157–161. 10.1002/art.40382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Yuan XL, Meng HY, Wang YC, Peng J, Guo QY, Wang AY, Lu SB, Bone-cartilage interface crosstalk in osteoarthritis: Potential pathways and future therapeutic strategies, Osteoarthr. Cartil. 22 (2014) 1077–1089. 10.1016/j.joca.2014.05.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Burr DB, Gallant MA, Bone remodelling in osteoarthritis., Nat. Rev. Rheumatol. 8 (2012) 665–673. 10.1038/nrrheum.2012.130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Li G, Yin J, Gao J, Cheng TS, Pavlos NJ, Zhang C, Zheng MH, Subchondral bone in osteoarthritis: insight into risk factors and microstructural changes., Arthritis Res. Ther. 15 (2013) 223. 10.1186/ar4405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Intema F, Hazewinkel HAW, Gouwens D, Bijlsma JWJ, Weinans H, Lafeber FPJG, Mastbergen SC, In early OA, thinning of the subchondral plate is directly related to cartilage damage: Results from a canine ACLT-meniscectomy model, Osteoarthr. Cartil. 18 (2010) 691–698. 10.1016/j.joca.2010.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Il Im G, Kim MK, The relationship between osteoarthritis and osteoporosis, J. Bone Miner. Metab. 32 (2014) 101–109. 10.1007/s00774-013-0531-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Dequeker J, Aerssens J, Luyten FP, Osteoarthritis and osteoporosis: clinical and research evidence of inverse relationship., Aging Clin. Exp. Res. 15 (2003) 426–439. 10.1007/BF03327364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Hart DJ, Mootoosamy I, Doyle DV, Spector TD, The relationship between osteoarthritis and osteoporosis in the general population: The Chingford study, Ann. Rheum. Dis. (1994). 10.1136/ard.53.3.158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Ng KC, Revell PA, Beer M, Boucher BJ, Cohen RD, Currey HL, Incidence of metabolic bone disease in rheumatoid arthritis and osteoarthritis, Ann Rheum Dis. 43 (1984) 370–377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Rizou S, Chronopoulos E, Ballas M, Lyritis GP, Clinical manifestations of osteoarthritis in osteoporotic and osteopenic postmenopausal women, J. Musculoskelet. Neuronal Interact. (2018). 10.1007/s00198-013-2312-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Chu L, Liu X, He Z, Han X, Yan M, Qu X, Li X, Yu Z, Articular Cartilage Degradation and Aberrant Subchondral Bone Remodeling in Patients with Osteoarthritis and Osteoporosis, 00 (2019) 1–11. 10.1002/jbmr.3909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Sniekers YH, Weinans H, Bierma-Zeinstra SM, van Leeuwen JPTM, van Osch GJVM, Animal models for osteoarthritis: the effect of ovariectomy and estrogen treatment - a systematic approach, Osteoarthr. Cartil. 16 (2008) 533–541. 10.1016/j.joca.2008.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Calvo E, Castañeda S, Largo R, Fernández-Valle ME, Rodríguez-Salvanés F, Herrero-Beaumont G, Osteoporosis increases the severity of cartilage damage in an experimental model of osteoarthritis in rabbits, Osteoarthr. Cartil. 15 (2007) 69–77. 10.1016/j.joca.2006.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Bellido M, Lugo L, a Roman-Blas J, Castañeda S, Caeiro JR, Dapia S, Calvo E, Largo R, Herrero-Beaumont G, Subchondral bone microstructural damage by increased remodelling aggravates experimental osteoarthritis preceded by osteoporosis., Arthritis Res. Ther. 12 (2010) R152. 10.1186/ar3103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Bellido M, Lugo L, Roman-Blas JA, Castañeda S, Calvo E, Largo R, Herrero-Beaumont G, Improving subchondral bone integrity reduces progression of cartilage damage in experimental osteoarthritis preceded by osteoporosis, Osteoarthr. Cartil. 19 (2011) 1228–1236. 10.1016/j.joca.2011.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Castañeda S, Largo R, Calvo E, Bellido M, Gómez-Vaquero C, Herrero-Beaumont G, Effects of estrogen deficiency and low bone mineral density on healthy knee cartilage in rabbits, J. Orthop. Res. 28 (2010) 812–818. 10.1002/jor.21054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Srikanth VK, Fryer JL, Zhai G, Winzenberg TM, Hosmer D, Jones G, A meta-analysis of sex differences prevalence, incidence and severity of osteoarthritis, Osteoarthr. Cartil. 13 (2005) 769–781. 10.1016/j.joca.2005.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Nevitt MC, Felson DT, Sex hormones and the risk of osteoarthritis in women: Epidemiological evidence, in: Ann. Rheum. Dis, 1996. 10.1136/ard.55.9.673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Nasatzky E, Grinfeld D, Boyan BD, Dean DD, Ornoy A, Schwartz Z, Transforming growth factor-β1 modulates chondrocyte responsiveness to 17β-estradiol, Endocrine. 11 (1999) 241–249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Tankó LB, Søndergaard B-CB-C, Oestergaard S, Karsdal M. a., Christiansen C, An update review of cellular mechanisms conferring the indirect and direct effects of estrogen on articular cartilage., Climacteric. 11 (2008) 4–16. 10.1080/13697130701857639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Le Bail JC, Liagre B, Vergne P, Bertin P, Beneytout JL, Habrioux G, Aromatase in synovial cells from postmenopausal women, Steroids. 66 (2001) 749–757. 10.1016/S0039-128X(01)00104-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Liang Y, Duan L, Xiong J, Zhu W, Liu Q, Wang D, Liu W, Li Z, Wang D, E2 regulates MMP-13 via targeting miR-140 in IL-1β-induced extracellular matrix degradation in human chondrocytes, Arthritis Res. Ther. 18 (2016) 105. 10.1186/s13075-016-0997-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Claassen H, Steffen R, Hassenpflug J, Varoga D, Wruck CJ, Brandenburg LO, Pufe T, 17β-estradiol reduces expression of MMP-1, −3, and −13 in human primary articular chondrocytes from female patients cultured in a three dimensional alginate system, Cell Tissue Res. 342 (2010) 283–293. 10.1007/s00441-010-1062-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Melville KM, Kelly NH, Khan SA, Schimenti JC, Ross FP, Main RP, van der Meulen MCH, Female mice lacking estrogen receptor-alpha in osteoblasts have compromised bone mass and strength., J. Bone Miner. Res. 29 (2014) 370–379. 10.1002/jbmr.2082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Melville KM, Kelly NH, Surita G, Buchalter DB, Schimenti JC, Main RP, Ross FP, van der Meulen MCH, Effects of Deletion of ERalpha in Osteoblast-Lineage Cells on Bone Mass and Adaptation to Mechanical Loading Differ in Female and Male Mice., J. Bone Miner. Res. 30 (2015) 1468–1480. 10.1002/jbmr.2488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Rooney AM, van der Meulen MCH, Mouse models to evaluate the role of estrogen receptor α in skeletal maintenance and adaptation, Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1410 (2017) 85–92. 10.1111/nyas.13523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Xiong J, Onal M, Jilka RL, Weinstein RS, Manolagas SC, O’Brien CA, Matrix-embedded cells control osteoclast formation, Nat. Med. (2011). 10.1038/nm.2448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Zhong Z, Zylstra-Diegel CR, Schumacher CA, Baker JJ, Carpenter AC, Rao S, Yao W, Guan M, Helms JA, Lane NE, Lang RA, Williams BO, Wntless functions in mature osteoblasts to regulate bone mass, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. (2012). 10.1073/pnas.1120407109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Ko FC, Dragomir C, Plumb DA, Goldring SR, Wright TM, Goldring MB, Van Der Meulen MCH, In vivo cyclic compression causes cartilage degeneration and subchondral bone changes in mouse tibiae, Arthritis Rheum. 65 (2013) 1569–1578. 10.1002/art.37906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Ko FC, Dragomir CL, Plumb DA, Hsia AW, Adebayo OO, Goldring SR, Wright TM, Goldring MB, van der Meulen MCH, Progressive cell-mediated changes in articular cartilage and bone in mice are initiated by a single session of controlled cyclic compressive loading., J. Orthop. Res. (2016). 10.1002/jor.23204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Adebayo OO, Ko FC, Wan PT, Goldring SR, Goldring MB, Wright TM, van der Meulen MCH, Role of subchondral bone properties and changes in development of load-induced osteoarthritis in mice, Osteoarthr. Cartil. 25 (2017) 2108–2118. 10.1016/j.joca.2017.08.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Holyoak DT, Otero M, Armar NS, Ziemian SN, Otto A, Cullinane D, Wright TM, Goldring SR, Goldring MB, van der Meulen MCH, Collagen XI mutation lowers susceptibility to load-induced cartilage damage in mice, J. Orthop. Res. 36 (2018) 711–720. 10.1002/jor.23731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Zhang M, Xuan S, Bouxsein ML, Von Stechow D, Akeno N, Faugere MC, Malluche H, Zhao G, Rosen CJ, Efstratiadis A, Clemens TL, Osteoblast-specific knockout of the insulin-like growth factor (IGF) receptor gene reveals an essential role of IGF signaling in bone matrix mineralization, J. Biol. Chem. 277 (2002) 44005–44012. 10.1074/jbc.M208265200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Clemens TL, Tang H, Maeda S, a Kesterson R, Demayo F, Pike JW, Gundberg CM, Analysis of osteocalcin expression in transgenic mice reveals a species difference in vitamin D regulation of mouse and human osteocalcin genes., J. Bone Miner. Res. 12 (1997) 1570–6. 10.1359/jbmr.1997.12.10.1570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Feng Y, Manka D, Wagner K-U, Khan SA, Estrogen receptor-alpha expression in the mammary epithelium is required for ductal and alveolar morphogenesis in mice., Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 104 (2007) 14718–23. 10.1073/pnas.0706933104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Lynch ME, Main RP, Xu Q, Walsh DJ, Schaffler MB, Wright TM, van der Meulen MCH, Cancellous bone adaptation to tibial compression is not sex dependent in growing mice., J. Appl. Physiol. 109 (2010) 685–691. 10.1152/japplphysiol.00210.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Fritton JC, Myers ER, Wright TM, Van Der Meulen MCH, Loading induces site-specific increases in mineral content assessed by microcomputed tomography of the mouse tibia, Bone. 36 (2005) 1030–1038. 10.1016/j.bone.2005.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Melville KM, Robling AG, van der Meulen MCH, In vivo axial loading of the mouse tibia, Methods Mol. Biol. (2015). 10.1007/978-1-4939-1619-1_9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Bouxsein ML, Boyd SK, Christiansen BA, Guldberg RE, Jepsen KJ, Muller R, Guidelines for assessment of bone microstructure in rodents using micro-computed tomography., J. Bone Miner. Res. 25 (2010) 1468–1486. 10.1002/jbmr.141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Xu L, Flahiff CM, Waldman BA, Wu D, Olsen BR, Setton LA, Li Y, Osteoarthritis-like changes and decreased mechanical function of articular cartilage in the joints of mice with the chondrodysplasia gene (cho), Arthritis Rheum. 48 (2003) 2509–2518. 10.1002/art.11233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Glasson SS, Chambers MG, Van Den Berg WB, Little CB, The OARSI histopathology initiative - recommendations for histological assessments of osteoarthritis in the mouse., Osteoarthr. Cartil 18 Suppl 3 (2010) S17–23. 10.1016/j.joca.2010.05.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Little CB, Barai A, Burkhardt D, Smith SM, Fosang AJ, Werb Z, Shah M, Thompson EW, Matrix metalloproteinase 13-deficient mice are resistant to osteoarthritic cartilage erosion but not chondrocyte hypertrophy or osteophyte development., Arthritis Rheum. 60 (2009) 3723–33. 10.1002/art.25002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Hayami T, Pickarski M, Wesolowski GA, McLane J, Bone A, Destefano J, Rodan GA, Duong LT, The Role of Subchondral Bone Remodeling in Osteoarthritis: Reduction of Cartilage Degeneration and Prevention of Osteophyte Formation by Alendronate in the Rat Anterior Cruciate Ligament Transection Model, Arthritis Rheum. 50 (2004) 1193–1206. 10.1002/art.20124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Khorasani MS, Diko S, Hsia AW, Anderson MJ, Genetos DC, Haudenschild DR, Christiansen BA, Effect of alendronate on post-traumatic osteoarthritis induced by anterior cruciate ligament rupture in mice, Arthritis Res. Ther. 17 (2015) 1–11. 10.1186/s13075-015-0546-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Panahifar A, Maksymowych WP, Doschak MR, Potential mechanism of alendronate inhibition of osteophyte formation in the rat model of post-traumatic osteoarthritis: Evaluation of elemental strontium as a molecular tracer of bone formation, Osteoarthr. Cartil. 20 (2012) 694–702. 10.1016/j.joca.2012.03.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Shirai T, Kobayashi M, Nishitani K, Satake T, Kuroki H, Nakagawa Y, Nakamura T, Chondroprotective effect of alendronate in a rabbit model of osteoarthritis, J. Orthop. Res. 29 (2011) 1572–1577. 10.1002/jor.21394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Siebelt M, Waarsing JH, Groen HC, Muller C, Koelewijn SJ, de Blois E, Verhaar JAN, de Jong M, Weinans H, Inhibited osteoclastic bone resorption through alendronate treatment in rats reduces severe osteoarthritis progression., Bone. 66 (2014) 163–170. 10.1016/j.bone.2014.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Zhu S, Chen K, Lan Y, Zhang N, Jiang R, Hu J, Alendronate protects against articular cartilage erosion by inhibiting subchondral bone loss in ovariectomized rats, Bone. 53 (2013) 340–349. 10.1016/j.bone.2012.12.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Spector TD, Conaghan PG, Buckland-Wright JC, Garnero P, Cline GA, Beary JF, Valent DJ, Meyer JM, Effect of risedronate on joint structure and symptoms of knee osteoarthritis: results of the BRISK randomized, controlled trial [ISRCTN01928173]., Arthritis Res. Ther. 7 (2005) 625–633. 10.1186/ar1716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Bingham CO 3rd, Buckland-Wright JC, Garnero P, Cohen SB, Dougados M, Adami S, Clauw DJ, Spector TD, Pelletier J-P, Raynauld J-P, Strand V, Simon LS, Meyer JM, Cline GA, Beary JF, Risedronate decreases biochemical markers of cartilage degradation but does not decrease symptoms or slow radiographic progression in patients with medial compartment osteoarthritis of the knee: results of the two-year multinational knee osteoarthritis st, Arthritis Rheum. 54 (2006) 3494–3507. 10.1002/art.22160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Mohan G, Perilli E, Parkinson IH, Humphries JM, Fazzalari NL, Kuliwaba JS, Pre-emptive, early, and delayed alendronate treatment in a rat model of knee osteoarthritis: Effect on subchondral trabecular bone microarchitecture and cartilage degradation of the tibia, bone/cartilage turnover, and joint discomfort, Osteoarthr. Cartil. 21 (2013) 1595–1604. 10.1016/j.joca.2013.06.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Iwamoto J, Takeda T, Sato Y, Matsumoto H, Effects of risedronate on osteoarthritis of the knee, Yonsei Med. J. 51 (2010) 164–170. 10.3349/ymj.2010.51.2.164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Davis AJ, Smith TO, Hing CB, Sofat N, Are Bisphosphonates Effective in the Treatment of Osteoarthritis Pain? A Meta-Analysis and Systematic Review, PLoS One. 8 (2013). 10.1371/journal.pone.0072714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Intema F, Sniekers YH, Weinans H, Vianen ME, Yocum SA, Zuurmond AMM, DeGroot J, Lafeber FP, Mastbergen SC, Similarities and discrepancies in subchondral bone structure in two differently induced canine models of osteoarthritis, J. Bone Miner. Res. 25 (2010) 1650–1657. 10.1002/jbmr.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Engdahl C, Börjesson AE, Forsman HF, Andersson A, Stubelius A, Krust A, Chambon P, Islander U, Ohlsson C, Carlsten H, Lagerquist MK, The role of total and cartilage-specific estrogen receptor alpha expression for the ameliorating effect of estrogen treatment on arthritis., Arthritis Res. Ther. 16 (2014) R150. 10.1186/ar4612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Miyatake K, Muneta T, Ojima M, Yamada J, Matsukura Y, Abula K, Sekiya I, Tsuji K, Coordinate and synergistic effects of extensive treadmill exercise and ovariectomy on articular cartilage degeneration, BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 17 (2016) 238. 10.1186/s12891-016-1094-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Roman-Blas JA, Castañeda S, Largo R, Herrero-Beaumont G, Osteoarthritis associated with estrogen deficiency., Arthritis Res. Ther. 11 (2009) 241. 10.1186/ar2791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Figure 1. Joint capsule fibrosis and thickening with loading was slightly increased in pOC-ERαKO mice. Representative H&E stained histology images of the joint capsule (JC) insertion to the lateral tibia (LT). Joint capsule thickness and cellularity increased with loading. Scale bar: 500μm, inlay: 200μm.

Supplementary Table 1. Regression models for prediction of OARSI score and osteophyte size. (A) OARSI score predicted by epiphyseal BV/TV, metaphyseal BV/TV, and load. (B) Osteophyte size predicted by subchondral plate thickness, metaphyseal BV/TV, and load. Standardized beta coefficients. ^p<0.1, *p<0.05, **p<0.001.