Abstract

Sagittal misalignment has been associated with negative quality of life (QOL). However, there is no report on whether differences in preoperative sagittal misalignment in patients with lumbar degenerative diseases affect postoperative results after lateral lumbar interbody fusion (LLIF). We investigated whether preoperative sagittal alignment influences the correction of alignment after surgery and whether the preoperative sagittal alignment affects the rating of low back pain, leg pain, and leg numbness. The subjects were 81 patients (48 male, 33 females, average age at surgery 70.2 years) who underwent anterior–posterior combined surgery with LLIF and percutaneous pedicle screws from May 2018 to July 2020. Cluster analysis was performed using the preoperative sagittal vertical axis (SVA) value, and patients were classified into two groups (group 1; n = 30, SVA = 129.0 ± 53.4 mm, group 2; n = 51, SVA = 30.8 ± 23.5 mm). Baseline demographics and treatment data were compared between groups. Sagittal and pelvic parameters and pain scores, such as low back pain, leg pain, and leg numbness, were also compared. Operative time, blood loss, and length of hospital stay did not differ significantly between groups. The changes (Δ) in SVA and lumbar lordosis (LL) for all patients from before to after surgery were not significant (ΔSVA; p = 0.218, ΔLL; p = 0.189, respectively). The SVA, LL, and PI − LL changed significantly after the surgery in group 1, but no marked improvement in sagittal imbalance was obtained after LLIF surgery. The improvement in each pain score from before to after the surgery did not differ significantly between groups. LLIF surgery has a limited chance of recovering sagittal imbalance. However, postoperative low back pain, leg pain, and leg numbness may be improved by LLIF surgery, regardless of the preoperative sagittal alignment.

Subject terms: Neurology, Neurological disorders, Quality of life, Neurosurgery

Introduction

Sagittal misalignment as an adult spinal deformity (ASD) has attracted attention because of its association with negative quality of life (QOL) and increased disability1–3. An increased sagittal vertical axis (SVA) and pelvic incidence − lumbar lordosis (PI − LL) mismatch are strongly related to adverse patient-reported outcomes3,4. Thus, the goals of surgical correction involve optimizing the PI − LL and SVA to achieve global sagittal balance. Various procedures have been reported for planning the corrective surgery for treating ASD5–7. One widely accepted radiological target for achieving spinopelvic harmony via corrective surgery for ASD is to keep the pelvic incidence (PI)–lumbar lordosis (LL) within 10°4,8,9. Because the SVA more sensitively represents sagittal alignment and correlates strongly with the PI − LL mismatch, it is also used for planning surgical correction in ASD patients. Sagittal malalignment was defined as a sagittal vertical axis (SVA) ≥ 50 mm according to the Scoliosis Research Society-Schwab classification9.

Since its introduction in 200610, lateral lumbar interbody fusion (LLIF) surgery has been used to treat various spinal pathologies11,12. Some groups have adopted it as an adjunct in corrective surgery for spinal deformity13–15. There is a wealth of data to show that LLIF surgery is useful for obtaining indirect decompression of the spine for treating lumbar degenerative diseases (LDDs)16–20.

Factors that can predict the success of indirect decompression with LLIF, including patient and surgical factors, particularly the cage position, have been investigated but are still debated18,21–24. In general, it makes sense to place the LLIF cage anterior to obtain the degree of LL23, but cases have been reported in which indirect decompression may not be accepted18. In addition, although some spinal parameter correction rates after LLIF surgery have been reported, there remains limited evidence about the effectiveness of LLIF surgery to correct sagittal deformities25–28. Similarly, there are few reports of whether and how preoperative sagittal balance affects pain in specific areas, such as low back pain (LBP), leg pain (LP), and leg numbness (LN), after LLIF surgery.

Therefore, the purpose of our study was to evaluate whether preoperative sagittal alignment influences the correction of alignment after LLIF surgery and whether the preoperative sagittal alignment affects the rating of LBP, LP, and LN.

Results

Patient demographics

During the study period, a total of 120 patients received LLIF in our institutions, and 81 patients (48 male and 33 females) with an average of 70.2 ± 10.4 years were evaluated. Patients whose data were incomplete or could not be followed up were excluded. The demographic and operative characteristics are detailed in Table 1. LLIF was performed at 110 levels, and 58 (71.6%) patients underwent a single-level procedure. The most commonly treated level was L4/5 (59/110, 53.6%). When the sagittal imbalance was defined as SVA ≥ 50 mm, 40 patients (42/81, 51.9%) were classified as having a sagittal imbalance.

Table 1.

Demographic information.

| Characteristic | Values |

|---|---|

| Total number | 81 |

| Age (years), mean (SD) | 70.2(10.4) |

| ≧ 65 years, n (%) | 65 (80.2) |

| Sex, n (%) | |

| Male | 48 (59.3) |

| Female | 33 (40.7) |

| Height (cm), mean (SD) | 159.0 (9.7) |

| Body weight (kg), mean (SD) | 61.7 (12.2) |

| BMI (kg/m2), mean (SD) | 24.3 (3.6) |

| Number of levels treated, n (mean) | 110 (1.4) |

| Number of levels treated, n (%) | |

| 1 level | 58 (71.6) |

| 2 levels | 17 (21.0) |

| 3 levels | 6 (7.4) |

| Operated level, n | |

| L1/2 | 2 |

| L2/3 | 11 |

| L3/4 | 38 |

| L4/5 | 59 |

| Average OR time (min), mean (SD) | 109.2 (37.0) |

| Average Blood loss (ml), mean (SD) | 85.9 (118.8) |

| CRP on POD1, mean (SD) | 3.3 (2.5) |

| Average length of stay (days), mean (SD) | 15.1 (4.2) |

SD standard deviation.

Comparison of clinical outcomes and radiological assessment

Of the 81 patients, 30 were in group 1 with a high SVA (16 men, 14 females, average age 71.1 years), and 51 were in group 2 (32 men, 19 females, average age 69.7 years). A power analysis performed to detect the difference and showed 0.929 (effect size d = 0.8, alpha = 0.05, total sample size = 81, two-tailed). Age, sex distribution, height, body weight, and BMI did not differ significantly between the two groups. The number of levels treated, operative time, blood loss, and length of stay did not differ between the two groups. However, the C-reactive protein level on the day after surgery was lower in group 2. The rates of thigh pain and motor weakness, postoperative complications peculiar to LLIF surgery did not differ significantly between the two groups. Comparison of spinal parameters showed that preoperative LL differed significantly between groups 1 and 2 (24.3 ± 16.8° vs. 40.5 ± 12.3°, respectively) (Table 2). Given that the average PT in the elevated SVA group (group 1) is not high, most patients bend forward to relieve their stenosis.

Table 2.

Comparison of demographic and treatment data between two groups.

| Characteristic | Group 1 | Group 2 | p-value‡ |

|---|---|---|---|

| SVA (mm), mean (SD) | 129.0 (53.4) | 30.8 (23.5) | |

| No. of patients | 30 | 51 | |

| Age (years), mean (SD) | 71.1 (9.9) | 69.7 (10.8) | 0.670 |

| Sex, n (%) | |||

| Male | 16 | 32 | 0.408 |

| Female | 14 | 19 | |

| Height (cm), mean (SD) | 157.7(9.6) | 159.7 (9.7) | 0.363 |

| Body weight (kg), mean (SD) | 60.8 (13.2) | 62.3 (11.6) | 0.588 |

| BMI (kg/m2), mean (SD) | 24.2 (3.2) | 24.4 (3.9) | 0.876 |

| Number of levels treated, n (mean) | 46 (1.5) | 64 (1.3) | 0.122 |

| Average OR time (min) | 118.4 (42.1) | 103.8 (33.0) | 0.153 |

| Average Blood loss (ml) | 121.8 (167.3) | 64.8 (71.5) | 0.079 |

| CRP on POD1, mean (SD) | 4.5 (3.2) | 2.5 (1.6) | < 0.001* |

| Average Length of stay (days) | 15.8 (4.5) | 14.7 (3.9) | 0.279 |

| No. of motor weakness (%) | 6 (20.0) | 8 (15.7) | 0.762 |

| No. of thigh pain (%) | 7 (23.3) | 9 (17.6) | 0.572 |

| Preoperative parameter | |||

| CR Cobb (°) | 10.7 (8.7) | 6.3 (5.5) | 0.049* |

| LL (°) | 24.3 (16.8) | 40.5 (12.3) | < 0.001* |

| TK (°) | 21.8 (11.8) | 22.8 (10.3) | 0.679 |

| PI (°) | 50.4 (7.4) | 50.5 (8.8) | 0.969 |

| PT (°) | 23.2 (7.8) | 21.5 (7.2) | 0.325 |

| SS (°) | 27.2 (8.3) | 29.0 (8.7) | 0.374 |

SD standard deviation.

*Statistically significant.

‡Comparison between two groups.

Table 3 summarizes the pre-and postoperative sagittal parameters. In group 1, ΔSVA (− 34.0 ± 65.3 mm, p = 0.008), ΔLL (6.5 ± 14.0°, p = 0.021), and ΔPI − LL (− 4.9 ± 12.8°, p = 0.045) were significant from preoperative to postoperative. In group 2, ΔSVA (9.3 ± 25.1 mm, p = 0.011) was significant from preoperative to postoperative. ΔLL was significantly larger (1.6 ± 10.9°, p = 0.011), and ΔPI − LL was significantly improved (0.9 ± 7.3°, p = 0.029) in group 1 with high SVA compared with group 2. The pelvic parameters ΔPI, ΔPT, and ΔSS did not differ significantly between the two groups.

Table 3.

Preoperative, postoperative, and change from pre- to postoperative sagittal measurements.

| Preoperative | Postoperative | ΔPost–pre | p-value† | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SVA (mm) | ||||

| Group 1 | 129.0 (53.4) | 95.0 (48.8) | − 34.0 (65.3) | 0.008* |

| Group 2 | 30.8 (23.5) | 40.1 (34.9) | 9.3 (25.1) | 0.011* |

| ALL | 67.2 (60.5) | 60.4 (48.3) | − 6.7 (48.8) | 0.218 |

| p value‡ | < 0.001* | < 0.001* | 0.001* | |

| LL (°) | ||||

| Group 1 | 24.3 (16.8) | 30.7 (15.7) | 6.5 (14.0) | 0.021* |

| Group 2 | 40.5 (12.3) | 39.5 (11.6) | − 1.0 (8.0) | 0.363 |

| ALL | 34.7 (15.7) | 36.3 (13.9) | 1.6 (10.9) | 0.189 |

| p value‡ | < 0.001* | 0.020* | 0.011* | |

| TK (°) | ||||

| Group 1 | 21.8 (11.8) | 21.4 (12.8) | − 0.6 (5.6) | 0.723 |

| Group 2 | 22.8 (10.3) | 24.4 (9.1) | 1.5 (5.6) | 0.057 |

| ALL | 22.4 (10.8) | 23.3 (10.6) | 0.8 (5.6) | 0.183 |

| p value‡ | 0.679 | 0.278 | 0.108 | |

| PI (°) | ||||

| Group 1 | 50.4 (7.4) | 52.0 (8.1) | 1.6 (4.3) | 0.058 |

| Group 2 | 50.5 (8.8) | 50.4 (7.7) | − 0.1 (5.9) | 0.872 |

| ALL | 50.5 (8.3) | 51.0 (7.8) | 0.5 (5.4) | 0.412 |

| p value‡ | 0.969 | 0.371 | 0.173 | |

| PT (°) | ||||

| Group 1 | 23.2 (7.8) | 23.1 (7.5) | − 0.2 (5.5) | 0.867 |

| Group 2 | 21.5 (7.2) | 21.3 (6.9) | − 0.2 (5.5) | 0.777 |

| ALL | 22.2 (7.4) | 22.0 (7.1) | − 0.2 (5.5) | 0.742 |

| p value‡ | 0.325 | 0.289 | 0.969 | |

| SS (°) | ||||

| Group 1 | 27.2 (8.3) | 28.9 (9.2) | 1.7 (7.3) | 0.203 |

| Group 2 | 29.0 (8.8) | 29.1 (7.7) | 0.1 (5.7) | 0.914 |

| ALL | 28.3 (8.6) | 29.0 (8.2) | 0.7 (6.3) | 0.325 |

| p value‡ | 0.374 | 0.948 | 0.261 | |

| PI − LL (°) | ||||

| Group 1 | 26.2 (14.9) | 21.3 (13.8) | − 4.9 (12.8) | 0.045* |

| Group 2 | 10.0 (9.6) | 10.9 (9.9) | 0.9 (7.3) | 0.388 |

| ALL | 16.0 (14.1) | 14.7 (12.5) | − 1.3 (10.0) | 0.265 |

| p value‡ | < 0.001* | < 0.01* | 0.029* | |

†Comparison with pre op.

‡Comparison between two groups.

*Statistically significant.

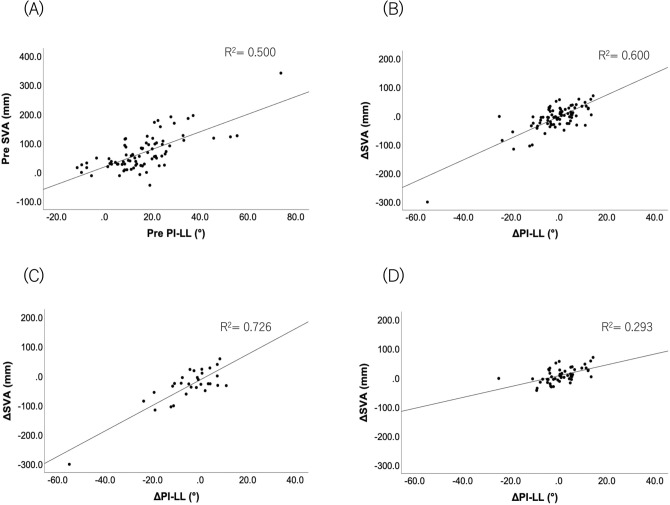

We found strong correlations between the preoperative SVA and PI − LL in all 81 patients (r = 0.647, p < 0.001) and between the changes in these parameters (r = 0.584, p < 0.001). The correlation coefficients between ΔSVA and ΔPI − LL were also statistically significant 0.607 (p < 0.001) and 0.562 (p < 0.001) in groups 1 and 2, respectively (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Correlations between SVA (y-axis) and PI − LL (x-axis). Each plot represents 81 cases. (A) Preoperative and (B) Δ (postoperative–preoperative) correlations. Each plot represents the case of (C) group 1 (n = 30) and (D) group 2 (n = 51). Δ (postoperative–preoperative) correlations. SVA sagittal vertical axis, PI − LL pelvic incidence minus lumbar lordosis.

To assess the degree of indirect decompression resulting from LLIF surgery, Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) scan was used to compare the CSA of the dural sac preoperatively and immediately after the operation. In all 81 patients, the average CSA increased from 60.2 ± 34.0 to 84.2 ± 36.4 mm2 from before to after the operation. The preoperative CSA (63.0 ± 34.2 vs 58.2 ± 35.5 mm2, p = 0.448), postoperative CSA (86.0 ± 37.7 vs 83.0 ± 36.7 mm2, p = 0.686), and ΔCSA (23.0 ± 18.8 vs 24.8 ± 24.8 mm2, p = 0.986) did not differ between groups (data not shown).

Comparison of pain scores

Numeric rating scale (NRS) scores were obtained for LBP (NRSLBP), LP (NRSLP), and LN (NRSLN). Preoperatively, all patients had NRS scores indicating LBP (mean NRSLBP 6.3 ± 2.6), LP (mean NRSLP 6.8 ± 2.8), or LN (mean NRSLN 6.3 ± 3.2), but these scores did not differ significantly between the two groups. The NRSLBP scores one year after surgery were 4.0 ± 3.4 and 2.4 ± 2.8 for groups 1 and 2, respectively (p = 0.054), and the NRSLP scores one year after surgery were 2.6 ± 2.7 and 1.8 ± 2.3 for groups 1 and 2, respectively (p = 0.150). Postoperative NRSLN score were statistically significant (3.4 ± 2.8 and 2.1 ± 2.8, p = 0.019, respectively). In both groups, postoperative pain improved one year after the operation, but the improvements in each NRS score did not differ significantly between the two groups (Table 4).

Table 4.

Preoperative, postoperative, and change from pre- to postoperative each NRS scores in the two groups.

| Preoperative | Postoperative | ΔPost–pre | p-value† | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NRSLBP | ||||

| Group 1 | 6.5 (2.7) | 4.0 (3.4) | − 2.6 (3.4) | < 0.001* |

| Group 2 | 6.2 (2.7) | 2.4 (2.8) | − 3.8 (3.9) | < 0.001* |

| All | 6.3 (2.6) | 3.0 (3.0) | − 3.4 (3.8) | < 0.001* |

| p value‡ | 0.474 | 0.054 | 0.180 | |

| NRSLP | ||||

| Group 1 | 6.6 (2.4) | 2.6 (2.7) | − 4.3 (2.7) | < 0.001* |

| Group 2 | 6.9 (3.0) | 1.8 (2.3) | − 5.1 (3.7) | < 0.001* |

| All | 6.8 (2.8) | 2.0 (2.4) | − 4.8 (3.4) | < 0.001* |

| p value‡ | 0.280 | 0.150 | 0.078 | |

| NRSLN | ||||

| Group 1 | 6.5 (2.9) | 3.4 (2.8) | − 3.4 (3.4) | < 0.001* |

| Group 2 | 6.1 (3.3) | 2.1 (2.8) | − 4.0 (4.0) | < 0.001* |

| All | 6.3 (3.2) | 2.5 (2.8) | − 3.8 (3.8) | < 0.001* |

| p value‡ | 0.701 | 0.019* | 0.281 | |

NRS numeric rating scale, NRSLBP NRS for low back pain, NRSLP NRS for leg pain, NRSLN NRS for leg numbness.

†Comparison with pre op.

‡Comparison between two groups.

*Statistically significant.

A power analysis performed to detect the correlation (effect size d = 0.5, alpha = 0.05, two-tailed) showed 0.999, 0.874, 0.979 for total sample sizes 81, 30, and 51, respectively. The correlations between ΔSVA and NRS for LBP, LP, and LN were not significant in either group (Table 5).

Table 5.

Spearman correlations mean (Spearman’s r) between ⊿SVA and each pain score.

| ∆SVA | NRSLBP | NRSLP | NRSLN | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All (n = 81) | ||||

| ΔSVA | 1.000 | |||

| ΔNRSLBP | − 0.014 | 1.000 | ||

| ΔNRSLP | − 0.061 | 0.569*** | 1.000 | |

| ΔNRSLN | − 0.194 | 0.487*** | 0.633*** | 1.000 |

| Group 1 (n = 30) | ||||

| ΔSVA | 1.000 | |||

| ΔNRSLBP | 0.116 | 1.000 | ||

| ΔNRSLP | 0.132 | 0.546** | 1.000 | |

| ΔNRSLN | 0.021 | 0.364* | 0.531** | 1.000 |

| Group 2 (n = 51) | ||||

| ΔSVA | 1.000 | |||

| ΔNRSLBP | 0.010 | 1.000 | ||

| ΔNRSLP | − 0.010 | 0.607*** | 1.000 | |

| ΔNRSLN | − 0.187 | 0.507*** | 0.673*** | 1.000 |

SVA sagittal vertical axis, NRS numeric rating scale, NRS scores for low back pain (NRSLBP), for leg pain (NRSLP), and for leg numbness (NRSLN).

*p < 0.05, **< 0.01, ***< 0.001 indicates significant differences.

Discussion

This is the first study to evaluate whether the sagittal balance in patients with LDD affects the improvement in pain one year after LLIF surgery. At present, various approaches are used in the ever-evolving context of spinal surgery29. LLIF surgery is now accepted as an effective treatment option for patients with LDD. Retrospective studies of indirect decompression surgery have investigated sagittal alignment changes after LLIF surgery30,31. Some groups have suggested that LLIF can increase segmental lordosis (SL) more than does transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion32,33. Acosta et al. reported that SL significantly increased by 2.9°, despite no significant changes in LL and SVA after the LLIF surgery30. Another study reported an increase in SL of 2.4°–2.7° after LLIF surgery17. A larger interbody cage is placed during LLIF than in surgery using the posterior approach, which results in more significant endplate contact for LLIF. Therefore, patients should benefit from a healthy biomechanical environment for fusion and segmental deformity correction. Another study reports that single position LLIF surgery can reduce operation time as minimally invasive spinal treatments17.

Understanding the limitations of LLIF is as important as knowing its strengths. It was previously reported that patients with claudication had sagittal imbalance, a higher SVA value, lower LL, and greater pelvic retroversion34. Sagittal imbalance is associated with poor QOL and is a source of LBP2. In addition, increasing the mechanical load on the lumbar spine because of PI − LL inconsistency, including SVA, raises concerns about adjacent segment disease35. For these reasons, improving spinal alignment is essential. Fuji et al. reported that sagittal imbalance returned to normal after decompression surgery in 43% of patients. They found that the prognostic factors for postoperative sagittal imbalance were a preoperative SVA value of > 69 mm and a PI − LL difference of > 11.536. Madkouri et al. also reported that sagittal spinal imbalance improved after decompression surgery, suggesting that the preoperative partially forward-leaning posture is reversible and relieves pain. However, they also reported that patients presenting with an SVA value of > 100 mm showed residual imbalance37. These data suggest that the preoperative SVA value is associated with improving the SVA after surgery.

The present study found no significant changes in the LL of the 81 patients one year after LLIF surgery and that the overall sagittal alignment as shown by the SVA parameter or pelvic parameter did not change after LLIF surgery. The anterior sagittal imbalance is thought to reflect the loss of LL primarily, although it has been suggested that increasing the postoperative LL can improve the SVA in patients with a large preoperative SVA. In our study, Group 1 had an increased degree of LL after LLIF surgery. However, the mean postoperative SVA was 95.0 ± 48.8 mm in group 1, which fit the criterion for imbalance as an SVA of ≥ 50 mm. We believe that the potential for improving the sagittal imbalance by LLIF surgery is limited in patients with severe preoperative sagittal imbalance.

A systematic review of LLIF surgery reported significantly improved clinical outcomes in patients with LDD11. It was recently reported that LLIF could improve LBP, LP, and numbness in the lower extremities38. The present study examined whether the changes in NRS scores for LBP, LP, and LN after LLIF surgery were related to the preoperative SVA. We found no significant differences and that all NRS scores showed similar improvement, as previously reported11,21.

Our study has some limitations, such as the retrospective study, small number of patients, and the short follow-up period. Despite the significant results with this small population, a larger sample size of this cohort is needed to improve the statistical power. In addition, the LLIF surgery performed by spine surgeons is not always unified. Finally, the effects of preoperative comorbidities and the patient's social background should also be considered. Future prospective studies are needed to stratify the population to reduce possible confounding effects.

Conclusions

LLIF surgery has a limited chance of recovering SVA in patients with preoperative sagittal imbalance. However, this study showed that indirect decompression using LLIF surgery might improve postoperative LBP, LP, and LN, regardless of the preoperative sagittal alignment.

Material and methods

The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Tokai University School of Medicine, the House Clinical Study Committee, and the Profit Reciprocity Committee, and all of the methods were carried out in accordance with the ethical principles set out in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki. This retrospective study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Tokai University School of Medicine, and the requirement to obtain informed consent was waived (IRB approval no.: 21R-147). After institutional review board approval, a retrospective review of the clinical data from a single academic institution was performed. Patients were treated from May 2018 to July 2020.

Included patients

The inclusion criteria included patients who underwent LLIF surgery for LDDs, including spondylolisthesis and spinal stenosis with instability. It is difficult to distinguish whether elevated SVA was from a spinal deformity or patients stooping forward due to spinal stenosis. Thus, we evaluated ASD or LDDs based on physical findings or pelvic parameters. Patients with LBP and mainly intermittent claudication and neurological symptoms, such as numbness, pain, and weakness in the lower extremities, were diagnosed with lumbar spinal stenosis.

Patients with significant lumbar scoliosis, grade 2 spondylolisthesis, or lumbar fracture were excluded. We also excluded patients who did not have adequate pre-and postoperative standing radiographs one year after surgery and those who could not evaluate their pain using a scoring system.

The preoperative information for all patients was assessed using standard radiographs, MRI scans, and computed tomography scans. The spine surgeon recorded the location of stenosis based on an evaluation of the preoperative imaging studies. The patient underwent indirect decompression with LLIF and posterior percutaneous pedicle screw fixation on the same day, and patients who underwent direct decompression were excluded. The operative approach for LLIF surgery has been detailed previously17,39.

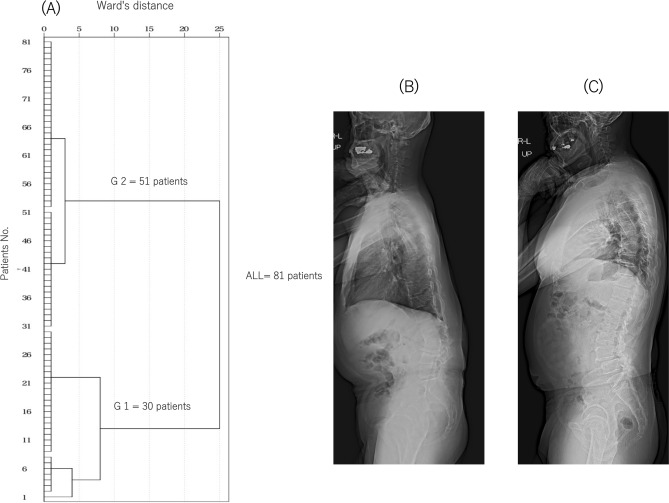

Cluster analysis was performed using the hierarchical cluster analysis procedure using IBM SPSS Statistics (version 23.0; IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Cluster analysis was used to classify the patients into two groups based on the preoperative SVA (Fig. 2): group 1 with a high SVA (129.0 ± 53.4 mm) and group 2 with an SVA close to normal (30.8 ± 23.5 mm).

Figure 2.

Dendrograms of the hierarchical classification of patients who received LLIF surgery (n = 81). (A) The numbers of patients in each cluster at different Ward’s distances are shown. The patients were classified into groups 1 (n = 30) and 2 (n = 51) from the cluster analysis. Standing full-length X-ray lateral views of typical cases in groups 1 (B) and 2 (C).

Surgical technique

The basic procedure of our LLIF was performed according to the surgical technique described by Ozgur et al.10. The technique has been explained in our previous papers, but we will briefly describe17,39–41. The surgery is performed for indirect decompression, and the emphasis is not on alignment correction. All patients underwent LLIF through a single incision, mini-open direct visualizing approach. Patients were placed in true lateral positions, and a horizontal skin incision was made. A blunt incision was made until it reached the vertebral body. The cartilage endplate was removed using a Cobb elevator and curette when treating the endplate. Cage size trials were followed by additional disc curettage and rasping of the endplates. The surgeon determined the appropriate cage size by combining preoperative images and intraoperative cage template findings. All LLIF segments were applied with supplemental percutaneous pedicle screw fixation.

Radiological assessment

Standing full-length radiographs were evaluated preoperatively and one year after the surgery. Using X-rays of the whole spine with the patient in the standing position and standard measurements reported elsewhere42, we assessed the coronal Cobb angle, SVA, LL at T12-S1, thoracic kyphosis (TK) at T5-12, PI, pelvic tilt (PT), sacral slope (SS), and PI − LL. PI was measured as the angle between a line drawn perpendicular to the sacral endplate at its midpoint and a line drawn from the midpoint of the sacral endplate to the midpoint of the femoral head axis. LL was measured as the sagittal Cobb angle measured between the superior end plate of T12 and the superior endplate of S1. MRI was performed preoperatively and immediately after surgery to determine the cross-sectional area (CSA) of the spinal canal using the axial plane of T2-weighted images.

Clinical assessment

The clinical records were reviewed retrospectively by identifying demographic data, including age, sex, height, body weight, and body mass index (BMI). The operative time, blood loss volume, level of LLIF surgery, length of hospital stay, and LLIF-specific complications (motor weakness and thigh pain) were quantified using surgical items and hospitalization records. Anterior thigh pain that occurred between the time of surgery and discharge was recorded as “thigh pain”. If there were clinical problems with hip flexion after LLIF, “motor weakness” was recorded. Motor weakness was evaluated using the Barthel Index (BI) as reported previously16. Briefly, the stair climbing score of the BI evaluates whether a person can climb and descend stairs safely using a 3-point scale (0 = unable; 5 = needs help, such as verbal, physical, or carrying aids; 10 = independent). Patients whose stair climbing score was lowered by one rank after surgery was considered a motor weakness.

The pain intensity was assessed using an NRS, and NRS scores were obtained for LBP (NRSLBP), LP (NRSLP), and LN (NRSLN) preoperatively and 1 year after the surgery. An 11-point scale was used in which 0 = no pain to 10 = worst pain or pain as bad as it could be.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics. All values are expressed as mean ± standard deviation. The Shapiro–Wilk test was used to confirm the normality of the data distribution. For the direct comparison of the two groups, Student's t-test was used to analyze normally distributed data, and the Mann–Whitney U test was used to analyze nonnormally distributed data. The Pearson or Spearman coefficient was used to identify significant correlations between pre-and postoperative spinal parameters and between the changes (Δ) in SVA and pain in each area. We used the G-Power Analysis software program to determine sample size validity (G*Power 3.1). Post-hoc analysis using G*Power 3.1 was performed to detect the correlation of subjects and the difference between two independent groups.

The type 1 error was set at 5% for all statistical analyses, and p < 0.05 was considered to be significant.

Author contributions

A.H., H.K., D.S., M.S., and M.W. conceived the study. A.H. and H.K. wrote the main manuscript text. A.H., D.S., and H.K. collected data. A.H., H.K., and M.W. analyzed results. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Funding

The authors did not receive support from any organization for the submitted work.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Glassman SD, Berven S, Bridwell K, Horton W, Dimar JR. Correlation of radiographic parameters and clinical symptoms in adult scoliosis. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2005;30:682–688. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000155425.04536.f7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Glassman SD, et al. The impact of positive sagittal balance in adult spinal deformity. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2005;30:2024–2029. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000179086.30449.96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Smith JS, et al. Change in classification grade by the SRS-Schwab Adult Spinal Deformity Classification predicts impact on health-related quality of life measures: Prospective analysis of operative and nonoperative treatment. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2013;38:1663–1671. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e31829ec563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schwab FJ, et al. Radiographical spinopelvic parameters and disability in the setting of adult spinal deformity: A prospective multicenter analysis. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2013;38:E803–812. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e318292b7b9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Inami S, et al. Optimum pelvic incidence minus lumbar lordosis value can be determined by individual pelvic incidence. Eur.. Spine J. 2016;25:3638–3643. doi: 10.1007/s00586-016-4563-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rose PS, et al. Role of pelvic incidence, thoracic kyphosis, and patient factors on sagittal plane correction following pedicle subtraction osteotomy. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2009;34:785–791. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e31819d0c86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yamato Y, et al. Calculation of the target lumbar lordosis angle for restoring an optimal pelvic tilt in elderly patients with adult spinal deformity. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2016;41:E211–E217. doi: 10.1097/brs.0000000000001209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Boulay C, et al. Sagittal alignment of spine and pelvis regulated by pelvic incidence: Standard values and prediction of lordosis. Eur. Spine J. 2006;15:415–422. doi: 10.1007/s00586-005-0984-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schwab F, et al. Scoliosis Research Society-Schwab adult spinal deformity classification: A validation study. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2012;37:1077–1082. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e31823e15e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ozgur BM, Aryan HE, Pimenta L, Taylor WR. Extreme Lateral Interbody Fusion (XLIF): A novel surgical technique for anterior lumbar interbody fusion. Spine J. 2006;6:435–443. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2005.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lang G, et al. Potential and limitations of neural decompression in extreme lateral interbody fusion—A systematic review. World Neurosurg. 2017;101:99–113. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2017.01.080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rabau O, et al. Lateral lumbar interbody fusion (LLIF): An update. Glob. Spine J. 2020;10:17s–21s. doi: 10.1177/2192568220910707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mummaneni PV, et al. The minimally invasive interbody selection algorithm for spinal deformity. J. Neurosurg. Spine. 2021 doi: 10.3171/2020.9.Spine20230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wewel JT, et al. Safety of lateral access to the concave side for adult spinal deformity. J. Neurosurg. Spine. 2021 doi: 10.3171/2020.10.Spine191270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yamato Y, et al. Planned two-stage surgery using lateral lumbar interbody fusion and posterior corrective fusion: A retrospective study of perioperative complications. Eur. Spine J. 2021 doi: 10.1007/s00586-021-06879-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hiyama A, et al. Radiographs assessment of changes in the psoas muscle at L4–L5 level after single-level lateral lumbar interbody fusion in patients with postoperative motor weakness. J. Clin. Neurosci. 2021;90:165–170. doi: 10.1016/j.jocn.2021.05.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hiyama A, et al. Comparison of radiological changes after single-position versus dual-position for lateral interbody fusion and pedicle screw fixation. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 2019;20:601. doi: 10.1186/s12891-019-2992-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hiyama A, et al. Cluster analysis to predict factors associated with sufficient indirect decompression immediately after single-level lateral lumbar interbody fusion. J. Clin. Neurosci. 2021;83:112–118. doi: 10.1016/j.jocn.2020.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kepler CK, et al. Indirect foraminal decompression after lateral transpsoas interbody fusion. J. Neurosurg. Spine. 2012;16:329–333. doi: 10.3171/2012.1.Spine11528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Oliveira L, Marchi L, Coutinho E, Pimenta L. A radiographic assessment of the ability of the extreme lateral interbody fusion procedure to indirectly decompress the neural elements. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2010;35:S331–S337. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e3182022db0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Alimi M, et al. Radiological and clinical outcomes following extreme lateral interbody fusion. J. Neurosurg. Spine. 2014;20:623–635. doi: 10.3171/2014.1.Spine13569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Navarro-Ramirez R, et al. Are locked facets a contraindication for extreme lateral interbody fusion? World Neurosurg. 2017;100:607–618. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2016.11.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Otsuki B, et al. Analysis of the factors affecting lumbar segmental lordosis after lateral lumbar interbody fusion. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2020;45:E839–E846. doi: 10.1097/brs.0000000000003432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tohmeh AG, Khorsand D, Watson B, Zielinski X. Radiographical and clinical evaluation of extreme lateral interbody fusion: effects of cage size and instrumentation type with a minimum of 1-year follow-up. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2014;39:E1582–E1591. doi: 10.1097/brs.0000000000000645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Asaid M, et al. Restoring spinopelvic harmony with lateral lumbar interbody fusion: Is it a realistic goal? J. Spine Surg. 2020;6:639–649. doi: 10.21037/jss-20-605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hiyama A, et al. Changes in spinal alignment following extreme lateral interbody fusion alone in patients with adult spinal deformity using computed tomography. Sci. Rep. 2019;9:12039. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-48539-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kim SJ, Lee YS, Kim YB, Park SW, Hung VT. Clinical and radiological outcomes of a new cage for direct lateral lumbar interbody fusion. Korean J. Spine. 2014;11:145–151. doi: 10.14245/kjs.2014.11.3.145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Phan K, Rao PJ, Scherman DB, Dandie G, Mobbs RJ. Lateral lumbar interbody fusion for sagittal balance correction and spinal deformity. J. Clin. Neurosci. 2015;22:1714–1721. doi: 10.1016/j.jocn.2015.03.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mobbs RJ, Phan K, Malham G, Seex K, Rao PJ. Lumbar interbody fusion: Techniques, indications and comparison of interbody fusion options including PLIF, TLIF, MI-TLIF, OLIF/ATP, LLIF and ALIF. J. Spine Surg. 2015;1:2–18. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2414-469X.2015.10.05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Acosta FL, et al. Changes in coronal and sagittal plane alignment following minimally invasive direct lateral interbody fusion for the treatment of degenerative lumbar disease in adults: A radiographic study. J. Neurosurg. Spine. 2011;15:92–96. doi: 10.3171/2011.3.Spine10425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nakashima H, et al. Changes in sagittal alignment following short-level lumbar interbody fusion: Comparison between posterior and lateral lumbar interbody fusions. Asian Spine J. 2019;13:904–912. doi: 10.31616/asj.2019.0011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Saadeh YS, et al. Comparison of segmental lordosis and global spinopelvic alignment after single-level lateral lumbar interbody fusion or transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion. World Neurosurg. 2019;126:e1374–e1378. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2019.03.106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sembrano JN, Yson SC, Horazdovsky RD, Santos ER, Polly DW., Jr Radiographic comparison of lateral lumbar interbody fusion versus traditional fusion approaches: analysis of sagittal contour change. Int. J. Spine Surg. 2015;9:16. doi: 10.14444/2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Suzuki H, Endo K, Kobayashi H, Tanaka H, Yamamoto K. Total sagittal spinal alignment in patients with lumbar canal stenosis accompanied by intermittent claudication. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2010;35:E344–E346. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181c91121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tempel ZJ, et al. The influence of pelvic incidence and lumbar lordosis mismatch on development of symptomatic adjacent level disease following single-level transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion. Neurosurgery. 2017;80:880–886. doi: 10.1093/neuros/nyw073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fujii K, Kawamura N, Ikegami M, Niitsuma G, Kunogi J. Radiological improvements in global sagittal alignment after lumbar decompression without fusion. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2015;40:703–709. doi: 10.1097/brs.0000000000000708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Madkouri R, et al. Improvement in sagittal balance after decompression surgery without fusion in patients with degenerative lumbar stenosis: Clinical and radiographic results at 1 year. World Neurosurg. 2018;114:e417–e424. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2018.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hiyama A, et al. Short-term comparison of preoperative and postoperative pain after indirect decompression surgery and direct decompression surgery in patients with degenerative spondylolisthesis. Sci. Rep. 2020;10:18887. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-76028-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hiyama A, Katoh H, Sakai D, Watanabe M. A new technique that combines navigation-assisted lateral interbody fusion and percutaneous placement of pedicle screws in the lateral decubitus position with the surgeon using wearable smart glasses: A small case series and technical note. World Neurosurg. 2021;146:232–239. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2020.11.089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hiyama A, Nomura S, Sakai D, Watanabe M. Utility of power tool and intraoperative neuromonitoring for percutaneous pedicle screw placement in single position surgery: A technical note. World Neurosurg. 2022;157:56–63. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2021.09.113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hiyama A, Sakai D, Sato M, Watanabe M. The analysis of percutaneous pedicle screw technique with guide wire-less in lateral decubitus position following extreme lateral interbody fusion. J. Orthop. Surg. Res. 2019;14:304. doi: 10.1186/s13018-019-1354-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schwab F, Patel A, Ungar B, Farcy JP, Lafage V. Adult spinal deformity-postoperative standing imbalance: How much can you tolerate? An overview of key parameters in assessing alignment and planning corrective surgery. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2010;35:2224–2231. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181ee6bd4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]