Abstract

Airborne transmission is a possible infection route of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). This investigation focuses on the airborne infection risk of COVID-19 in a nursing unit in an inpatient building in Shenzhen, China. On-site measurements and questionnaire surveys were conducted to obtain the air change rates and occupant trajectories, respectively. The aerosol transport and dose–response models were applied to evaluate the infection risk. The average outdoor air change rate measured in the wards was 1.1 h−1, which is below the minimum limit of 2.0 h−1 required by ASHRAE 170–2021. Considering the surveyed occupant behavior during one week, the patients and their attendants spent an average of 19.4 h/d and 15.1 h/d, respectively, in the wards, whereas the nurses primarily worked in the nurse station (3.0 h/d) and wards (2.4 h/d). The doctors primarily worked in their offices (2.6 h/d) and wards (1.1 h/d). Assuming one undetected COVID-19 infector emitting severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) in the nursing unit, we calculated the accumulated viral dose and infection probabilities of the occupants. After one week, the cumulative infection risks of the patients and attendants were almost equal (0.002), and were higher than those of the nurses (0.0013) and doctors (0.0004). Proper protection measures, such as reducing the number of attendants, increasing the air change rate, and wearing masks, were found to reduce the infection risk. It should be noted that the reported results are based on several assumptions, such as the speculated virological properties of SARS-CoV-2 and the particular trajectories of occupants. Moreover, only second generations of transmission were taken into consideration, whereas in reality, the week-long exposure may cause third generation of transmission or worse.

Keywords: COVID-19, Infection risk, Inpatient department, Occupant behavior

1. Introduction

1.1. Background

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), which is caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), has had a significant effect on public health and economic development globally [[1], [2], [3]]. Scientists have highlighted the likelihood of airborne transmission of SARS-CoV-2 in enclosed spaces [4,5]. Hospitals are recognized as places with a considerable risk of infectious disease transmission, and there have been numerous reports of cross-infection between patients and hospital staff [6]. In a retrospective analysis study, researchers determined that 57 out of 138 patients with COVID-19 may have been infected inside a hospital [7]. The inpatient department in a hospital is a special facility, wherein patients and hospital staff share enclosed spaces for days or even weeks, thereby increasing the risk of infection of both occupants. A total of 119 cases, including 80 staff and 39 patients from five inpatient wards, were confirmed at one hospital in South Africa. The spread of the disease was attributed to the frequent movement of patients between and within wards [8]. An outbreak of COVID-19 among adolescents at an inpatient behavioral health hospital, with a total of 19 COVID-19 positive patients aged 11–17, has also been reported in the literature [9]. Therefore, the risk of infection of both patients and staff in inpatient departments must be studied further.

Viral aerosol is an important transmission pathway and has been documented in several COVID-19 infection events [10,11]. Ribonucleic acid (RNA) copies of SARS-CoV-2 have been detected in air samples collected inside several hospital facilities [[12], [13], [14], [15], [16]]. The airborne transmission of COVID-19 by SARS-CoV-2 RNA copies in both suspended and deposited particles in hospital facilities has been documented in Brazil [14]. In addition, SARS-CoV-2 RNA copies were detected in 2 out of 8 exhaled breath condensate samples and 1 out of 12 bedside air samples collected from COVID-19 patients [13]. Viral RNA was also found in the air in a hospital ward in Milan, posing a significant risk to the hospital staff and patients [12]. Extensive investigations have been carried out on the virological properties of SARS-CoV-2 and viral aerosols, including the virus concentration in respiratory fluid and the biologic decay rate of the virus [[17], [18], [19]]. The viral loads of SARS-CoV-2 are reportedly different in different parts of the respiratory system, with values of 105–107 RNA copies/mL [[17], [18], [19]]. The half-life of SARS-CoV-2 was determined to be 1.1–1.2 h at a temperature of 21 °C-23 °C, and a relative humidity of 65% [20]. Considering the indoor transport and deposition of viral aerosols, investigations have confirmed that aerosols dissipate quickly within a distance of 1 m from the mouth, before being diluted, filtered, or deposited on to walls, floors, and other surfaces [21]. The on-site measurement of the size distribution of virus-laden particles in a healthcare facility in Kuwait demonstrated that aerosols have different transport rules based on their size distribution [15]. Accordingly, multiple measures have been recommended and adopted to prevent the airborne transmission of COVID-19 in hospitals. Multiple studies have suggested that increasing the fresh air ventilation rate can reduce airborne transmission, and this approach has been recommended by several organizations and governments [22,23]. Mask wearing has also been mandated or encouraged in several countries or regions. Large gatherings have been prohibited in several public places including hospitals, as controlling the number of occupants in enclosed spaces reduces the probability of infection through close contact and long-range airborne transmission.

Various models, such as the SI model, SIS model, SIR model, and Wells–Riley model, have been established to quantitatively evaluate airborne disease transmission [[23], [24], [25]]. In the Wells–Riley model, the infection risk of occupants in an enclosed space is directly related to the ventilation, occupant exposure duration, and ratio of infected individuals in the space [[26], [27], [28], [29]]. The quantitative microbial risk assessment (QMRA), which considers additional influencing factors, was also established to assess the exposure and infection risk of occupants in enclosed spaces [[30], [31], [32]]. The QMRA combines the aerosol transport and dose–response models, and the viral aerosol emission, dilution, filtration, deposition, and biological decay processes are also considered in the calculation. In general, the QMRA includes three procedures: the collection of data regarding the basic conditions (including the ventilation and occupancy of the given space), the calculation of the inhaled viral dose (calculated using the viral aerosol transport model, and primarily dependent on the exposure duration), and an assessment of the infection risk (using the dose–response model). The QMRA methodology has been applied to supermarkets, gyms, conference rooms, wastewater treatment plants, etc. [[30], [31], [32]].

Several investigations have been conducted to assess the infection risk of airborne diseases in inpatient wards and optimize the design of inpatient buildings to better control airborne infections. Zhou et al. modified the Wells–Riley model using a computational fluid dynamic simulation to investigate the distribution of the airborne infection risk in naturally-ventilated hospital wards with a central corridor [33]. The infection risks of the patients were assessed assuming fixed patient locations during exposure to viral aerosols for 4 h. The accuracy of this assessment could be improved by considering realistic patient activities. The treatment activities of medical staff were considered in Ref. [34], which assessed the infection risk of the Middle East respiratory syndrome-related coronavirus (MERS-CoV) considering staff, patients, and visitors in the same ward. However, the patients and visitors were assumed to be stationary. Occupant mobility was considered in Ref. [35], and the activities and locations of the patients were designated according to certain hypothesized behavioral rules. The MERS-CoV transmission risk was assessed based on the assumed ventilation and exposure duration.

In both the Wells–Riley model and the QMRA methodology, the exposure duration of the susceptible occupant is a predominant factor that influences the airborne infection risk. The exposure duration is directly associated with the occupant behavior and occupancy status of the spaces. Numerous investigations have been conducted on space occupancy, with most focusing on the smart control of building environments and energy saving [36]. Some investigations have also focused on occupancy-related operation strategies in hospitals, with the aim of providing more efficient medical services [37,38]. However, accurate descriptions of occupant mobility and the consequent exposure patterns in buildings have seldom been investigated and reported, which explains the assumptions of stationary patients and hypothetical activities in Refs. [[33], [34], [35]].

According to Ref. [39], occupancy represents the occupied status or number of occupants at four different levels: (1) the number of occupants in the building, (2) the occupancy status of a space, (3) the number of occupants in a space, and (4) the location of each occupant in the space. Owing to the development of advanced tracking technologies in recent decades, occupancy information can be collected instantly and accurately [40]. The occupancy information of levels (1), (2), and (3) can be easily recorded using low-cost doorway beam-break sensors at each doorway [37]. The level (4) occupancy status can be recorded by using wearable devices assisted by a smart gateway, cloud server, and web application [40]. Considering infection risk assessment and pandemic control in built environments, the existing literature primarily focuses on the level (3) occupancy status, that is, the number of occupants in an enclosed space [[26], [27], [28], [29], [30], [31], [32]]. However, this is only appropriate when the occupants are stationary and continuously exposed to viral aerosols in the space. However, in a realistic scenario, the occupants would experience inconsistent exposure in multiple spaces owing to multiple entries and exits. The inpatient department is a typical scenario wherein doctors and nurses may visit different viral-polluted wards, treatment rooms, and offices, thereby being exposed to inconsistent risks. This repeated and intermittent exposure may occur over hours or days and can be accumulated according to the dose–response model. In general, compared with commercial buildings (such as supermarkets and gyms), patients and medical staff in inpatient departments face higher infection risks.

1.2. Research gaps and objectives

The airborne transmission of COVID-19 in built environments is a significant concern. The infection risk in enclosed spaces must be assessed accurately, and extensive research has been conducted to this end. To the best of our knowledge, airborne infection risk assessment in the existing literature has primarily focused on short-term non-repeated exposure. In this study, we assess the multi-space long-term cumulative exposure and infection risks of occupants considering practical occupant behaviors. Accordingly, a novel methodology combining occupant trajectory analysis and ventilation rate measurement is presented herein. This methodology is applied to a typical nursing unit in an inpatient building in a hospital in Shenzhen, China. Furthermore, multiple functional spaces are considered in the nursing unit.

The novelty of this study is as follows: (i) the multi-space long-term cumulative exposure and infection risk are assessed, which is essential for improved pandemic control in certain buildings with multi-functional spaces and long-term occupancy; (ii) the detailed trajectories of 111 occupants (comprising 15 doctors, 22 nurses, 50 patients, and 24 attendants) in a typical Chinese nursing unit are collected and analyzed over the course of one week; (iii) the sources of viral exposure and disease infection can be determined retrospectively using the proposed methodology, that is, the methodology illustrates the accumulated infection risk and sources of the risk (from whom or in which space). Accordingly, the findings obtained herein can be used to formulate more targeted pandemic control policies.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Building information

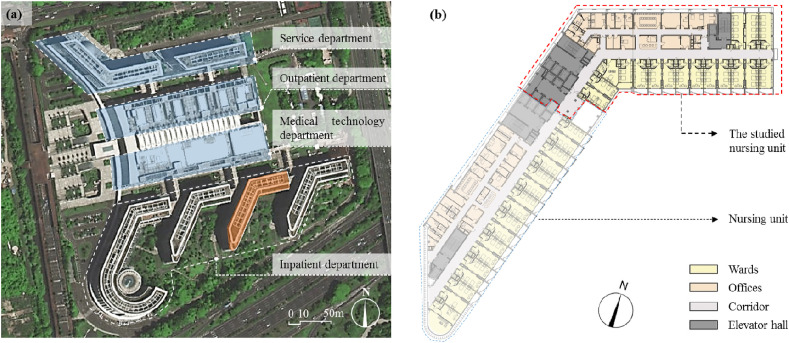

This study focuses on the individual infection risk of COVID-19 through aerosol transmission considering a typical nursing unit in a hospital in Shenzhen, China. The composition of the hospital is shown in Fig. 1 (a). It comprises four inpatient buildings (each with seven floors above ground and one basement), with a total of 2000 inpatient beds.

Fig. 1.

Nursing unit in a comprehensive hospital in Shenzhen, China: (a) surveyed inpatient building highlighted in orange and (b) plan of the inpatient building. (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the Web version of this article.)

The plans of the nursing units inside the inpatient buildings are similar. An orthopedic nursing unit (see Fig. 1(b)) on the 5th floor of the surveyed inpatient building (highlighted in orange in Fig. 1(a)) was selected herein. This nursing unit is quite typical, with a representative design of nursing units in Chinese hospitals. The area of the nursing unit is 1566 m2; it includes 17 wards (total area = 638 m2), four offices (total area = 150 m2), one treatment room (25 m2), one hazardous material storage room (10 m2), one nurse station (36.4 m2), and one elevator hall (65 m2) with four elevators shared by two adjacent nursing units.

The nursing unit is equipped with an air-conditioning system with distributed fan-coil units in each room and a central fresh air handling unit. Each ward contains a washroom with a continuously operating exhaust fan. All the windows in the nursing unit were sealed during the study.

The outdoor air change rates (ACH) of the multiple functional spaces in the nursing unit were obtained using the CO2 concentration decay curve method that was presented in our previous research [41]. Multiple studies have verified that this method can be used to accurately measure the air change rate of confined spaces [[42], [43], [44]]. The average air change rate in the 17 wards was 1.1 h−1, with the highest air change rate of 2.0 h−1. Detailed information is available in Ref. [41]. The average air change rates of the treatment and hazardous material storage rooms are 1.6 h−1 and 3.0 h−1, respectively. According to ASHRAE 170–2021 [45], the air change rates for inpatient, treatment, and hazardous material storage rooms should be above 2.0 h−1. Therefore, the air-conditioning system in the surveyed nursing unit does not provide sufficient fresh air in most wards and treatment rooms, which is unfavorable for controlling infectious disease transmission. In the infection risk assessment, the ACH value was set as follows (based on the field measurements): 1.1 h−1 for wards, 1.6 h−1 for treatment rooms, 1.5 h−1 for the office, 1.8 h−1 for medical rest rooms, 0.9 h−1 for the corridor and nurse station, and 0.6 h−1 for the elevator halls.

2.2. Occupant behavior survey

The medical staff in the nursing unit have fixed schedules that are updated on a weekly basis. Their daily routines are repetitive, with one doctor and two nurses in charge of 4–8 patients. During the survey week, 15 doctors and 22 nurses treated 50 inpatients. Their work schedules are presented in Table 1 .

Table 1.

Work schedules of medical staff in the nursing unit during the survey week.

| Category | Assigned ID | Workday | Ward No. in charge | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Doctor | Resident doctor | D1 | Mon, Tue, Wed (N), Sun | 1, 2, 3, 4 | |

| D2 | Fri, Sat, Sun (N) | 5, 6, 7, 8 | |||

| D3 | Mon, Tue (N), Sat, Sun | 8, 9, 10 | |||

| D4 | Mon (N), Thu, Fri, Sat (N) | 10, 11, 12 | |||

| D5 | Wed, Thu (N), Sun | 12, 13, 14, 15 | |||

| D6 | Tue, Wed, Thu, Fri (N) | 16, 17 | |||

| Attending doctor | AD1 | Thu | 12, 13, 14, 15 | ||

| AD2 | Wed | 1, 2, 3, 4 | |||

| AD3 | Tue, Sun | 10, 11, 12 | |||

| AD4 | Mon, Sat | 5, 6, 7, 8 | |||

| AD5 | Fri | 10, 11, 12, 16, 17 | |||

| Consultant doctor | CD1 | Mon, Tue, Fri | 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10 | ||

| CD2 | Wed, Thu | 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17 | |||

| Trainee doctor | TD1 | Mon, Fri | ___ | ||

| TD2 | Tue, Thu | ___ | |||

| Nurse | Group A | N1 | Wed, Thu, Fri, Sun | 3, 5 | |

| N2 | Mon, Tue, Thu, Fri | 5, 14 | |||

| N3 | Mon (N), Sat | 1, 2 | |||

| N4 | Mon, Tue (N) | 3, 4, 5 | |||

| N5 | Mon, Tue, Wed (N) | 6, 7 | |||

| N6 | Tue, Wed, Thu (N) | 1, 2 | |||

| N7 | Wed, Thu, Fri (N) | 3, 4, 5 | |||

| N8 | Tue, Fri, Sat (N) | 6, 7 | |||

| N9 | Fri, Sat, Sun (N) | 8, 9 | |||

| N10 | Thu, Sun | 9, 10 | |||

| Group B | N11 | Mon, Tue, Fri | 3, 5 | ||

| N12 | Tue, Wed, Sat | 5, 14 | |||

| N13 | Mon (N), Thu, Fri | 9, 10 | |||

| N14 | Mon, Tue (N), Sun | 8, 9 | |||

| N15 | Mon, Tue, Wed (N) | 11, 12 | |||

| N16 | Mon, Tue, Wed (N) | 12, 13 | |||

| N17 | Tue, Wed, Thu (N) | 14, 15, 16 | |||

| N18 | Wed, Thu, Fri (N) | 11, 12 | |||

| N19 | Thu, Fri, Sat (N) | 16, 17 | |||

| N20 | Fri, Sat, Sun (N) | 14, 15, 16 | |||

| N21 | Sat, Sun | 12, 13 | |||

| N22 | Tue, Wed | 16, 17 | |||

*(N) represents the night shift, during which the medical staff stay in the inpatient building for 24 h.

As illustrated in Table 1, there were 15 doctors working in the nursing unit, including resident doctors, attending doctors, consultant doctors, and trainee doctors. The resident doctors worked from 8:00 to 17:30 for three or four days during the week. Each resident doctor had one night shift (stayed in the nursing unit for 24 h) during the week. The attending doctors checked the patients in the wards between 8:00 and 9:00, and worked in the nursing unit for one or two days during the week. The consultant doctors worked in the nursing unit for two or three days during the week. The trainee doctors worked in the nursing unit for two days during the week. The 22 nurses were divided into two groups: Groups A and B. Each group comprised two head nurses (who worked from 8:00 to 17:30 for three or four days during the week) and eight nurses (who worked for two or three days and had one night shift during the week).

During the week, the doctor-to-patient ratio was 0.14–0.27, with a daily-averaged ratio of 0.2. The nurse-to-patient ratio was 0.28–0.46, with a daily-averaged ratio of 0.4. The attending doctors and nurses of each patient were relatively fixed. This arrangement reduces the inter-contact routes between the patients and the medical staff, i.e., the patients had limited chances of contact with other medical staff. From the perspective of pandemic control, the reduced inter-contact routes are favorable for preventing airborne disease transmission.

To obtain the detailed trajectories of each occupant, a questionnaire-based survey was conducted in the nursing unit during the week (May 31–June 6, 2020). The trajectories of the occupants in the nursing unit (including 15 doctors, 22 nurses, 50 patients, and 24 attendants, with a time interval of 5 min) were determined based on the questionnaires. The survey was performed as follows:

-

(1)

The working schedules of the doctors and nurses were collected, together with the admission and discharge timetable of all the patients.

-

(2)

The location of each occupant was recorded continuously (with a time interval of 5 min), and the movement trajectories of all the occupants were obtained.

-

(3)

The dwell times of the occupants in all the functional rooms were deduced, and the exposure duration was calculated if two or more occupants were in the same room simultaneously.

2.3. Airborne infection risk assessment

The individual COVID-19 infection risk of the occupants in the nursing unit was assessed based on the survey data recorded during the week. The assessment is based on the following assumptions:

-

(1)

One occupant was assumed to be infected with COVID-19, without being diagnosed or isolated. This assumption reflects the initial stages of the pandemic.

-

(2)

Only aerosol transmission (through aerosols containing viral RNA copies) was considered in the assessment. Aerosol transport was handled discretely considering four size bins, i.e., 0.8 μm, 1.8 μm, 3.5 μm, and 5.5 μm [46], which are the midpoint diameters of the aerosol particles in an equilibrium state after evaporation, that is, the residue.

-

(3)

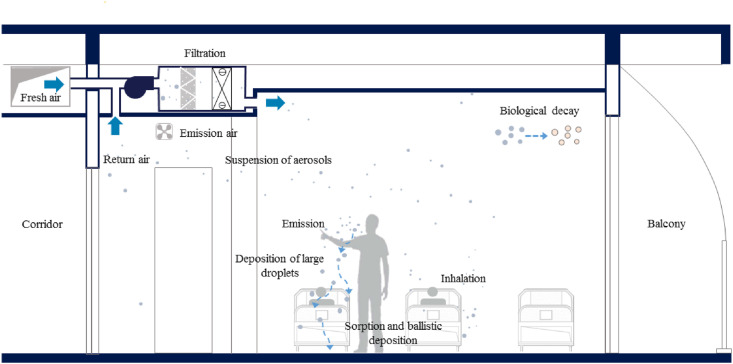

A well-mixed indoor air model was applied herein, that is, the viral aerosol concentration in any enclosed space was considered to be homogeneous. The viral concentration was determined by the emission rate of the infector, dilution by fresh air, filtration by the filter of the air-conditioning system, deposition on surfaces, and inactivation of the virus, as shown in Fig. 2 .

-

(4)

The viral RNA copies inhaled by each susceptible occupant in a viral-polluted space were accumulated, and the relationship between the inhaled viral dose and infection risk complied with the dose–response model.

Fig. 2.

Virus transport via exhaled aerosols in a ward.

Based on these assumptions, the time-varying virus concentration in an enclosed space can be expressed as:

| (1) |

| (2) |

where V is the volume of the enclosed space, m3; C i is the viral concentration in the i th size bin, RNA copies/m3; φ i is the total removal rate, h−1, including dilution, filtration, deposition, and inactivation of the virus; ACH is the air change rate of the enclosed space, h−1; ω i is the filtration rate by the filter in the i th size bin, h−1; γ i is the deposition rate in the i th size bin, h−1, which is determined by the area and deposition velocity with respect to the upward-facing horizontal surface, downward-facing horizontal surface, and vertical walls in the enclosed space [47]; and λ is the biological decay rate of the virus, h−1.

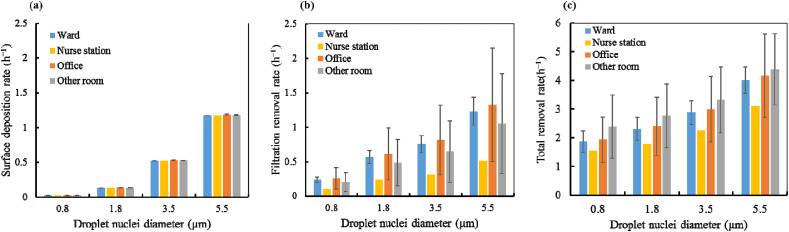

The infected individual was assumed to constantly emit viral aerosols. While some of the aerosols were removed through filtration and surface deposition, the rest were assumed to be uniformly distributed in the space. The surface deposition, filtration, and total removal rates in different functional spaces are illustrated in Fig. 3 . The removal rates in Eq. (2) were confirmed based on the on-site measurements (ACH) and data from several references. Detailed information is available in Ref. [48], which also focused on COVID-19 infection risks in built environments. Considering a particle size range of 0.5–10 μm, the deposition rate increases with the increase in particle diameter (see Fig. 3(a)). Furthermore, the surface deposition rates were almost the same in different functional spaces. The filtration rate was higher for larger particles, as depicted in Fig. 3(b). Consequently, the total removal rate was also higher for larger particles, as shown in Fig. 3(c). The total removal rate for different particle sizes is 1.5–4.0 h−1. Considering different functional spaces, the total removal rate of viral aerosols was lowest in the nurse station, followed by that in the wards and the office. These differences can be primarily attributed to the different outdoor air change rates in these spaces.

Fig. 3.

Removal rate for different particle size bins: (a) surface deposition rate; (b) filtration rate; and (c) total removal rate.

The experiment conducted in Ref. [20] revealed that the average half-life of SARS-CoV-2 in aerosol was 1.1 h. Accordingly, the biological decay rate of SARS-CoV-2 was set to 0.63 h−1 herein. The viral shedding rate by the infector, σ i (RNA copies/h), can be expressed as Eq. (3).

| (3) |

where q ex is the exhalation rate, which is set to 0.6 m3/h representing a light activity intensity; N i is the expelled particle concentration during breathing, 0.084 cm−3 (d eq = 0.8 μm), 0.009 cm−3 (d eq = 1.8 μm), 0.003 cm−3 (d eq = 3.5 μm), and 0.002 cm−3 (d eq = 5.5 μm) [46]; d 0 is the initial diameter of the expelled droplet; d eq is the equilibrium diameter (i.e., residue), which follows a linear relationship with d 0, i.e., d eq = 0.16d 0 [46]; and C virus is the virus concentration in the expelled fluid by the infector, RNA copies/mL. Based on the results of reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) tests of a throat swab [19], posterior oropharyngeal saliva [49], and a nasopharyngeal swab [50], the viral load in the respiratory fluid was set to 106 RNA copies/mL.

The virus exposure experienced by the susceptible (d) is:

| (4) |

where q in is the inhalation rate, which was set to 0.6 m3/h representing a light activity intensity, and t 0 and t 1 represent the entry and exit time of the susceptible occupant in the enclosed space.

The exponential dose–response model [Eq. (4)] is used in the infection risk assessment. A previous study [50] proved that the exponential dose–response model can be applied to the airborne transmission of SARS-CoV, which is quite similar to SARS-CoV-2. This model was implemented by Buonanno et al. [32] to assess SARS-CoV-2 airborne infection risks in a restaurant and a choir rehearsal hall.

| (5) |

where p is the infection probability and k is a pathogen dependent parameter (RNA copies). To the best of our knowledge, there are no experimental data and confirmed value of k for SARS-CoV-2. Considering the similarity between SARS-CoV-2 and SARS-CoV, the pathogen dependent parameter (k) was set to 55 RNA copies herein, based on the experimental data in Ref. [51], which suggested that an infectious dose of SARS-CoV on transgenic mice was 10–100 RNA copies.

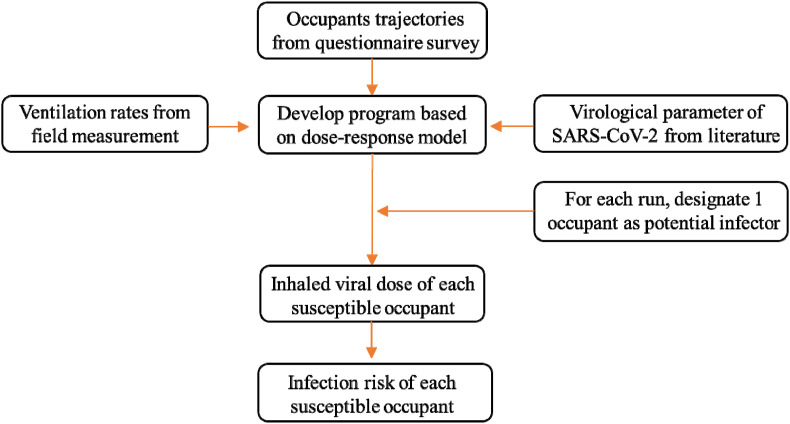

To fully consider and thoroughly discuss the possible cross-infections among the occupants (all 111 occupants were in the nursing unit at some point during the survey week), the assessment was repeated 111 times. In each iteration, one of the 111 occupants was assumed to be the undetected infector, whereas the rest were susceptible. The infection risks were analyzed based on the average conditions of the 111 iterations. The flowchart of the methodology used herein is shown in Fig. 4 .

Fig. 4.

Flowchart of the study methodology.

3. Calculations

3.1. Location distribution of occupants

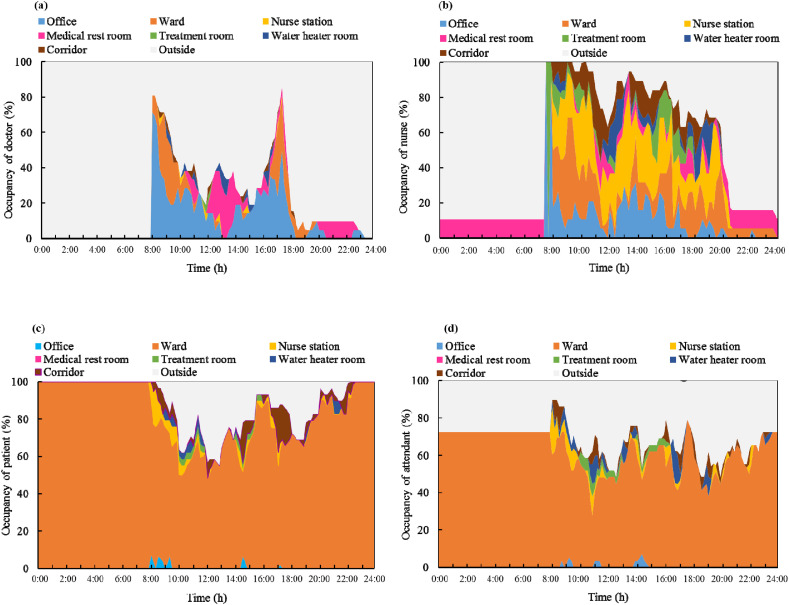

A total of 111 occupants were present in the nursing unit during the survey week. The spatial and temporal distributions of the occupants were recorded during the survey. The trajectories of the occupants in the inpatient building, that is, the changes in their spatial positions during the day are shown in Fig. 5 . The abscissa is the time of day, and the ordinate is the proportion of occupants. The colors represent the different functional spaces of the nursing unit. The gray background corresponds to occupants being outside the nursing unit.

Fig. 5.

Occupancy in different functional spaces: (a) doctors; (b) nurses; (c) patients; and (d) attendants.

As shown in Fig. 5(a), the doctors primarily worked in the offices and wards and rested in the medical rest room in the afternoon and at night. They spent a limited amount of time in the other functional spaces of the nursing unit. While working, approximately 25% of the doctors were in the medical offices, 25% of the doctors checked the patients in the wards during 8:30–10:00 and 16:30–17:30, and 20%–60% of the doctors left the nursing unit to diagnose or treat patients in the outpatient department. There was one doctor on duty in the medical rest room every night.

As shown in Fig. 5(b), the activities of the nurses were much more diversified compared to those of the other occupants and they moved around different spaces. In the early morning, the nurses worked in the office and the treatment room, preparing for the treatment of the patients and drug distribution. Subsequently, the nurses moved and worked in the offices, wards, and nursing station. They also spent a considerable amount of time in the corridor, recording data or walking between different functional spaces.

The spatial distributions of the patients and attendants were similar, but differed from that of the medical staff. As shown in Fig. 5(c) and (d), the patients and attendants spent most of their time in the wards. They occasionally went to the nurse station and corridor to make enquires or to walk. Approximately 35% of the patients and 40% of the attendants left the nursing unit to visit the garden nearby or the canteen inside the hospital. Of the 24 attendants present in the nursing unit during the survey, 17 spent 24 h in the nursing units, whereas the rest were present between 8:00 and 23:00.

3.2. Dwell time of occupants

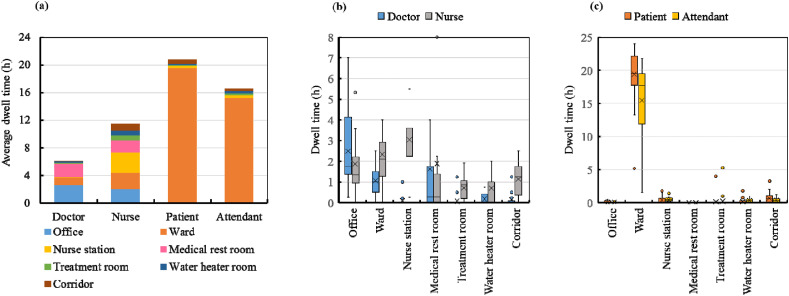

The temporal and spatial distributions of the occupants in the nursing unit were sorted, and the daily dwell time of the occupants in different functional spaces was confirmed. The results are illustrated in Fig. 6 .

Fig. 6.

Daily dwell times in different functional spaces: (a) daily-average dwell time; (b) dwell time quartile figure of medical staff; and (c) dwell time quartile figure of the patients and attendants.

The daily-averaged cumulative dwell times of the doctors, nurses, patients, and attendants in different functional spaces are shown in Fig. 6(a). As shown, the patients had the longest average dwell time in the inpatient building (20.8 h), followed by the attendants (16.7 h), nurses (11.9 h), and doctors (6.2 h). On average, doctors were in their offices for 2.6 h per day, the medical rest room for 1.9 h per day, and the wards for 1.1 h per day. The nurses spent an average of 3.0 h in the nurse station, 2.4 h in the wards, 2.0 h in the offices, 1.8 h in the nurse medical rest room, and 1.1 h in the corridor. Compared with the other occupants, the dwell times of the nurses in different functional spaces in the nursing unit were relatively consistent. The patients and attendants spent most of their time in the wards, which reaffirms the data shown in Fig. 5(c) and (d). The average dwell times of the patients were 19.4 h in the wards, 0.6 h in the corridor, and 0.3 h in the nurse station. The attendants spent 15.1 h in the wards, 0.4 h in the nurse station, and 0.3 h in the corridor.

The individual differences between the dwell times in different functional spaces are further highlighted in Fig. 6(b) and (c). The nurses worked in accordance with a fixed schedule, and their activity trajectories were less diversified. In contrast, the dwell times of the attendants in the wards and the doctors in the offices varied significantly, as their activity trajectories were quite diversified.

3.3. Contact duration among occupants

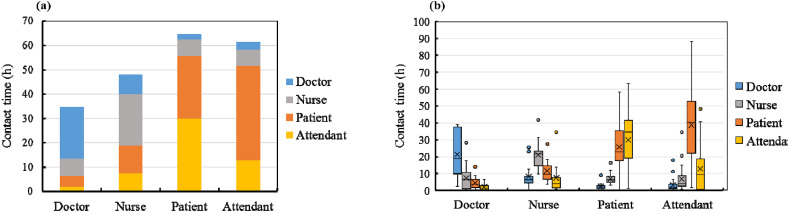

Herein, “contact” is defined as two or more individuals staying in the same space, and “contact duration” is calculated as the product of the co-staying time and the number of occupants. As in the case of the temporal and spatial trajectories of each occupant, the contact durations of the occupants were accumulated and sorted according to their groups. Accordingly, the contact durations of the different occupant groups were obtained. The daily-averaged results of the contact durations are shown in Fig. 7 .

Fig. 7.

Daily averaged contact duration: (a) cumulative histogram and (b) quartile figure.

Each color block in the cumulative histogram shown in Fig. 7(a) represents the contact duration per day between two different occupant groups. As the patients and attendants stayed in the nursing unit most of the time and shared the ward with other patients, the total contact duration of the patients and attendants was longer than that of the nurses and doctors. Furthermore, the contact duration between the patients and attendants was the longest. The nurses had a relatively uniform contact duration with all four occupant groups. The doctors had the longest contact duration with other doctors. The individual variations in the results are shown in Fig. 7(b). The contact duration among the doctors was quite diversified. This can be attributed to the different working schedules of the resident, attending, consultant, and trainee doctors. The contact duration of the nurses with the other occupants was less diversified owing to their relatively fixed schedule.

4. Results

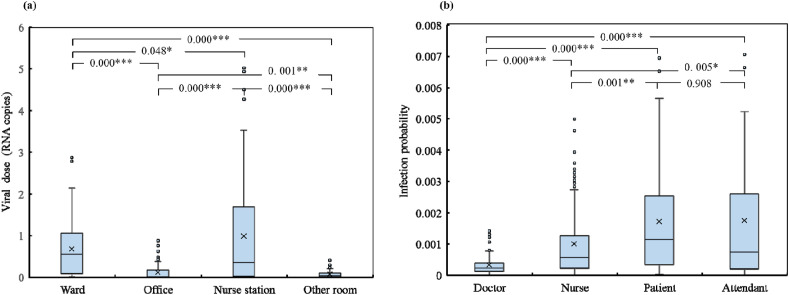

The temporal SARS-CoV-2 viral aerosol concentrations in each room of the nursing unit were ascertained using the simulation method described in Section 2.3. Each occupant was assigned a timetable in the simulation, that is, the occupants were assigned to certain rooms inside the nursing unit at any given time during the week-long simulation. The assignments were based on the temporal–spatial occupancy status of the occupants (i.e., the trajectories obtained from the timetable) obtained from the on-site survey, which represents the real case. If more than one occupant was present in a given room, they shared the room and made “contact” with each other. If one of the occupants in the shared room was the infector, the other occupant(s), that is, the susceptible, were exposed to viral aerosols and infection risks. An interesting situation occurs when a susceptible occupant enters a certain room after the infector has left. The susceptible occupant is possibly exposed to a low viral aerosol concentration with a low infection risk, as the viral aerosols may not be completely removed through dilution, filtration, deposition, and inactivation. In contrast, if a susceptible occupant enters the room before the infector, the exposure to viral aerosols only occurs after the infector enters the room, and the exposure duration is shorter than the total duration spent by the susceptible occupant in the room. The total viral dose inhaled by all the susceptible occupants in different functional spaces was calculated using Eq. (4), and the results are depicted in Fig. 8 (a). The accumulated COVID-19 infection risks of all the susceptible occupants were calculated using Eq. (5), and the results are illustrated in Fig. 8(b).

Fig. 8.

Weekly infection probability: (a) total viral dose in different functional spaces and (b) infection probability of susceptible occupants from different groups.

As shown in Fig. 8(a), the total inhaled virus RNA copies in the wards, offices, nurse station, and other rooms were 0.06–1.05, 0–0.3, 0.05–1.75, and 0–0.15 RNA copies, respectively. The averaged inhaled virus RNA copies in the wards, offices, nurse station, and other rooms were 0.68, 0.12, 0.98 and 0.07 RNA copies, respectively. The viral dose inhaled in the nurse station was significantly higher than that in the wards (p = 0.048), offices (p < 0.001) and other rooms (p < 0.001). Furthermore, the viral dose inhaled in the wards was significantly higher than that in the offices (p < 0.001) and other rooms (p < 0.001).

Considering the infection risks of different occupant groups, as shown in Fig. 8(b), the infection probabilities of the doctors, nurses, patients, and attendants were 0.00015–0.00035, 0.0002–0.0013, 0.0003–0.0026, and 0.0002–0.0026, respectively. The average infection probabilities of the doctors, nurses, patients, and attendants were 0.000329, 0.001001, 0.001720, and 0.001750, respectively. The accumulated infection risks in patients and attendants during the week were almost the same and exceeded those of the nurses and doctors. The results obtained herein contradict those obtained in Ref. [34], which assessed the infection risk of the Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS) in a hospital room using the dose–response model. The results in Ref. [34] indicated that nurses have the highest infection risk, followed by healthcare workers and patients. The differences in the results can be attributed to the fact that the study in Ref. [34] only focused on a single room, whereas our study focused on an entire nursing unit with different functional spaces and better reflects the real conditions.

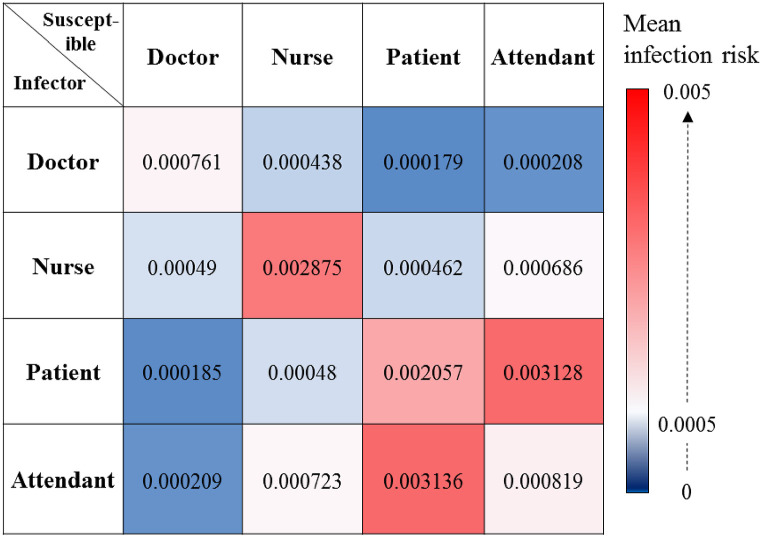

Assuming that one occupant is the infector, the cross-infection risk is defined as the probability of infection for a certain susceptible occupant group by an infector from the same or different occupant group. The cross-infection risks of the occupants after they had shared the nursing unit for a week are shown in Fig. 9 . The highest cross-infection risk (0.0031) occurred between the attendants and patients. The second highest cross-infection risk (0.0028) occurred among the nurses. The cross-infection risk among the patients was 0.0021. The cross-infection probabilities of the other occupant group pairs were less than 0.002. The infection risk for the doctors was primarily from other doctors.

Fig. 9.

Cross-infection probability among all occupant groups in the nursing unit.

5. Discussion

The proposed airborne infection risk assessment method can be used to quantify the performance of infection control policies in reducing the airborne infection risk in an inpatient building. The three most commonly used infection control policies, namely, reducing the number of attendants, increasing the ventilation rate, and requiring occupants to wear surgical masks, were investigated and analyzed herein. Practically, these policies can either be adopted separately or in combination. Therefore, a total of seven scenarios were investigated herein, as listed in Table 2 . Scenarios 1–3 consider different attendant-to-patient ratios, whereas Scenarios 4–6 consider different mask-wearing policies, while maintaining a constant air change rate and attendant-to-patient ratio. Scenario 7 combines all three policies with an enhanced air change rate (2 h−1 as required by ASHRAE 170–2021) [52], a reduced attendant-to-patient ratio, and mask wearing.

Table 2.

Scenario deterministic inputs.

| Scenario | Air change rate (h−1) | Ratio of attendant to patient | Mask wearing conditions |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Set according to the on-site measurement results (ward (1.1 h−1), treatment room (1.6 h−1), office (1.5 h−1), medical rest room (1.8 h−1), corridor (0.9 h−1), elevator hall (0.6 h−1)) | 1.0 | No one wear mask |

| 2 | The same as Scenario 1 | 0.75 | No one wear mask |

| 3 | The same as Scenario 1 | 0.5 | No one wear mask |

| 4 | The same as Scenario 1 | 0.5 | Only medical staff wear masks |

| 5 | The same as Scenario 1 | 0.5 | Only patients and attendants wear masks |

| 6 | The same as Scenario 1 | 0.5 | Everyone wears mask |

| 7 | Ward (2 h−1), the rest of spaces remain the same as Scenario 1. | 0.5 | Everyone wears mask |

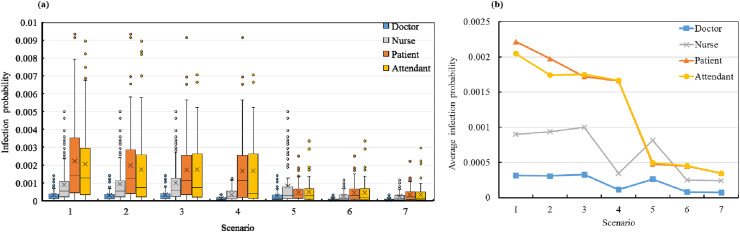

The accumulated infection probabilities of the patients, attendants, doctors, and nurses in all seven scenarios were calculated based on the surveyed occupant trajectories. The results are shown in Fig. 10 (a). The averaged infection risk of each occupant group was calculated, and the results are shown in Fig. 10(b).

Fig. 10.

Weekly infection risk in seven scenarios: (a) quartile graph of infection probability and (b) average infection probabilities of different occupant groups.

The infection probabilities for different attendant-to-patient ratios (1.0, 0.75, and 0.5) are shown in Fig. 10(a). The reduction in the attendant-to-patient ratio significantly reduced the infection risks of the patients and attendants, whereas those of the doctors and nurses changed almost imperceptibly. When the attendant-to-patient ratio reduced from 1.0 (Scenario 1) to 0.5 (Scenario 3), the averaged infection probabilities of the patients and attendants decreased by 22% and 15%, respectively.

Comparing the infection risks of Scenarios 3–6 provides supporting evidence for the benefits of surgical mask wearing. The aerosol filtration rates of the surgical mask for exhalation and inhalation were set to 50% herein, that is, the masks block 50% of the viral aerosols exhaled by the infected individual and inhaled by the susceptible occupants. This was simulated by multiplying the exhaled and inhaled SARS-CoV-2 RNA copy numbers by 50%. Enforcing mask wearing for doctors and nurses (Scenario 4) reduced the infection risks of all the occupants. The infection risk of the nurses decreased by 66%, as they tended to work long hours in multiple functional spaces and the surgical masks protected them from the viral aerosols. Similarly, the infection risk of the doctors reduced by 65%. In contrast, the infection risks of the patients and attendants did not reduce significantly. The benefits of surgical mask wearing are also highlighted by comparing Scenarios 3 and 5. When all the patients and attendants were required to wear surgical masks, their respective infection risks decreased significantly (Scenario 5). In Scenario 6, all the occupants in the nursing unit were required to wear surgical masks. In this scenario, the infection risks of all the occupant groups decreased significantly. Compared with Scenario 3, the infection risks of the occupants decreased by 74% in Scenario 6.

In Scenario 7, which combines all three infection control policies, the infection risks decreased even further. The average infection risks reduced to 0.000348 for patients, 0.000346 for attendants, 0.000241 for nurses, and 0.000075 for doctors. Compared with Scenario 6, the infection risks of the occupants in Scenario 7 decreased by an average of 15%. Therefore, surgical mask wearing has the highest influence on the infection risk among the three infection control policies. Nevertheless, the three policies (i.e., reducing the number of attendants, increasing ventilation rates, and surgical mask wearing) should be applied in combination, if possible.

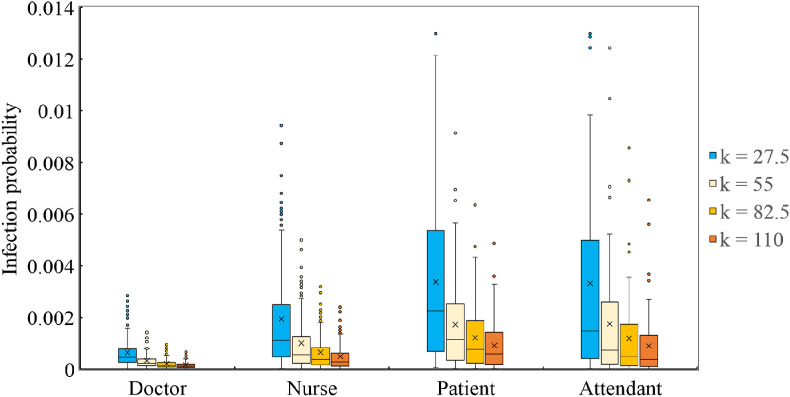

As the value of k characterizes the relationship between the inhaled viral dose and the possibility of the susceptible being infected, it has a significant influence on the results. Therefore, a sensitivity analysis was performed herein considering different values of k. The values of k were set to 27.5, 82.5, and 110, which corresponds to 50%, 150%, and 200% of the value assumed in Section 2.3, i.e., k = 55. The calculated infection risks of the doctors, nurses, patients, and attendants for different values of k are shown in Fig. 11 and the average risks are listed in Table 3 . The higher the value of k, the narrower the distributions of the infection risks of the different occupant groups. Furthermore, the average infection risk decreased with the increase in k, with an approximately inversely proportional relationship.

Fig. 11.

Distribution of infection risks for different values of k.

Table 3.

Average infection risks for different values of k.

| Occupants | k = 27.5 | k = 55 | k = 82.5 | k = 110 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Doctor | 0.00064 | 0.00033 | 0.00021 | 0.00016 |

| Nurse | 0.00194 | 0.00100 | 0.00065 | 0.00049 |

| Patient | 0.00337 | 0.00172 | 0.00121 | 0.00091 |

| Attendant | 0.00332 | 0.00175 | 0.00118 | 0.00089 |

Notably, the possibility of doctors being infected by other occupant groups is quite low, as shown in Fig. 11. This is because the doctors have minimal close contact with the other occupants in the nursing unit considered herein. If the working schedules, occupant trajectories, virus properties, and ventilation conditions were different, the infection risks could be different as well. Therefore, it is essential to obtain real data before applying the proposed model.

6. Limitations

This study focused on the airborne infection risk due to multi-space long-term cumulative exposure to viral aerosol. Despite demonstrating the efficacy of the proposed airborne infection risk assessment method, this study has some limitations. First, only aerosol transmission of COVID-19 was assessed herein. Therefore, in our next study, we intend to analyze the infection risk considering the close contact and fomite routes, using the occupant trajectories collected herein. Second, the concentration of SARS-CoV-2 in the enclosed space was assumed to be homogeneous. However, this is an acceptable assumption as the rooms in the nursing unit were small, and the air was well-mixed owing to continuous mechanical ventilation and occupant movement. Third, the uncertainty parameters introduce errors in the calculated infection risk. Addressing this limitation requires in-depth research on the virological properties of SARS-CoV-2. Moreover, the simulation assumed only one infector, which corresponds to the initial stages of the pandemic, when few infectors are present among the population. Finally, the week-long accumulated exposure to inhaled SARS-CoV-2 exaggerates the infection risks of the occupants in the nursing unit. In reality, week-long exposure may cause third generation transmission or worse, whereas the proposed model only considers second generation transmission. As the reported results are based on speculative virological properties of SARS-CoV-2 and specific occupant trajectories, the corresponding infection risks are a conservative estimate with redundancy. Accordingly, the adopted protection measures should be able to cope with such conservative estimates to suitably control infection transmission in a built environment.

7. Conclusions

In this study, we proposed a method that combines an occupant trajectory survey with on-site ventilation rate measurements to assess the infection risk of COVID-19 in a typical nursing unit in an inpatient hospital building in Shenzhen, China. The air change rates in the different functional spaces in the nursing unit were measured using the CO2 decay method. The trajectories of the 111 occupants present in the nursing unit during the week-long survey were obtained through an on-site survey and questionnaire. Assuming one undetected infector in the nursing unit, the COVID-19 infection risks of all the occupants were calculated based on first-hand data. The main conclusions are as follows:

-

(1)

The occupants in the inpatient building exhibited repetitive behavior. The patients and attendants primarily stayed inside the wards (19.4 h/d and 15.1 h/d, respectively), the nurses were primarily in the nurse station and wards (3.0 h/d and 2.4 h/d, respectively), and the doctors primarily stayed in the offices (2.6 h/d).

-

(2)

The weekly accumulated infection risks of the patients and attendants were almost equal (both averaged at 0.002) and were higher than those of the nurses (0.0013) and doctors (0.0004). The highest cross-infection probability (0.0031) occurred between the attendants and patients. The cross-infection probability among nurses (the same occupant group) was 0.0029. The cross-infection probability among patients was 0.0021. Doctors experienced the highest infection risk from other doctors.

-

(3)

A total of three infection control policies—reducing the number of attendants, increasing ventilation rates, and requiring surgical mask wearing—were analyzed herein. The effectiveness of these measures was compared through different simulation scenarios. Based on the infection risk assessment results of the different scenarios, we recommend the combined application of all three control policies.

It should be noted that the reported results are based on several assumptions, such as the speculated virological properties of SARS-CoV-2 and the particular trajectories of occupants. Moreover, only second generations of transmission were taken into consideration, whereas in reality, the week-long exposure may cause third generation of transmission or worse.

Credit author statement

Jiaxiong Li - Data collection, Data analysis, Writing - original draft. Chunying Li - Investigation, Writing - review and editing. Haida Tang - Methodology, Software, Funding acquisition.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgments

The study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 52078296 and No. 52008254).

References

- 1.Lipsitt J., Chan-Golston A.M., Liu J., Su J., Zhu Y., Jerrett M. Spatial analysis of COVID-19 and traffic-related air pollution in Los Angeles. Environ. Int. 2021;153:106531. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2021.106531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Amankwah-Amoah J. COVID‐19 pandemic and innovation activities in the global airline industry: a review. Environ. Int. 2021;156:106719. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2021.106719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Akbari P., Yazdanfar S., Hosseini S., Norouzian-Maleki S. Housing and mental health during outbreak of COVID-19. J. Build. Eng. 2021;43:102919. doi: 10.1016/j.jobe.2021.102919. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Morawska L., Milton D.K. It is time to address airborne transmission of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) Clin. Infect. Dis. 2020 doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bhattacharya A., Ghahramani A., Mousavi E. The effect of door opening on air-mixing in a positively pressurized room: implications for operating room air management during the COVID outbreak. J. Build. Eng. 2021;44 doi: 10.1016/j.jobe.2021.102900. 102900. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Peng J., Xu L., Wang M., Qi Y. Practical experiences on the prevention and treatment strategies to fight against COVID-19 in hospital. QJM. 2020;113(8):598–599. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/hcaa154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Li J., Gao R., Wu G., Wu X., Liu Z., Wang H., Huang Y., Pan Z., Chen J., Wu X. Clinical characteristics of emergency surgery patients infected with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pneumonia in Wuhan, China. Surgery. 2020;168(3):398–403. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2020.05.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lessells R., Moosa Y., de Oliveira T. 2020. Report into a Nosocomial Outbreak of Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID‐19) at Netcare St. Augustine's Hospital. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Krass P., Zimbrick-Rogers C., Iheagwara C., Ford C.A., Calderoni M. COVID-19 outbreak among adolescents at an inpatient behavioral health hospital. J. Adolesc. Health. 2020;67(4):612–614. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2020.07.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Li Y., Qian H., Hang J., Chen X., Ling H., Peng L., Jiansen L., Shenglan X., Jianjian W., Liu Li, et al. MedRXiv; 2020. Running Title: Aerosol Transmission of SARS-CoV-2 Evidence for Probable Aerosol Transmission of SARS-CoV-2 in a Poorly Ventilated Restaurant. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Azimi P., Keshavarz Z., Cedeno Laurent J.G., Stephens B., Allen J.G. Mechanistic transmission modeling of COVID-19 on the Diamond Princess cruise ship demonstrates the importance of aerosol transmission. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. Unit. States Am. 2021;118(8) doi: 10.1073/pnas.2015482118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Razzini K., Castrica M., Menchetti L., Maggi L., Negroni L., Orfeo N.V., Pizzoccheri A., Stocco M., Muttini S., Balzaretti C.M. SARS-CoV-2 RNA detection in the air and on surfaces in the COVID-19 ward of a hospital in Milan, Italy. Sci. Total Environ. 2020;742:140540. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.140540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Feng B., Xu K., Gu S., Zheng S., Zou Q., Xu Y., Yu L., Lou F., Yu F., Jin T., et al. Multi-route transmission potential of SARS-CoV-2 in healthcare facilities. J. Hazard Mater. 2021;402:123771. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2020.123771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Passos R.G., Silveira M.B., Abrahao J.S. Exploratory assessment of the occurrence of SARS-Co V-2 in aerosols in hospital facilities and public spaces of a metropolitan center in Brazil. Environ. Res. 2021;195:110808. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2021.110808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stern R.A., Al-Hemoud A., Alahmad B., Koutrakis P. Levels and particle size distribution of airborne SARS-CoV-2 at a healthcare facility in Kuwait. Sci. Total Environ. 2021;782:146799. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.146799. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhou L., Maosheng Y., Xiang Z., Bicheng H., Xinyue L., Haoxuan C., Lu Z., Yun L., Meng D., Bochao S., et al. Breath-, air- and surface-borne SARS-CoV-2 in hospitals. J. Aerosol Sci. 2021 doi: 10.1016/j.jaerosci.2020.105693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Iwasaki S., Fujisawa S., Nakakubo S., Kamada K., Yamashita Y., Fukumoto T., Sato K., Oguri S., Taki K., Senjo H., et al. Comparison of SARS-CoV-2 detection in nasopharyngeal swab and saliva. J. Infect. 2020;81(2):e145–e147. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2020.05.071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zou L., Ruan F., Huang M., Liang L., Huang H., Hong Z., Yu J., Kang M., Song Y., Xia J., et al. SARS-Co v-2 viral load in upper respiratory specimens of infected patients. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020:1177–1179. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2001737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pan X., Chen D., Xia Y., Wu X., Li T., Ou X., Zhou L., Liu J. Viral load of SARS-CoV-2 in clinical samples. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2020:411–412. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30113-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Morris D.H., van Doremalen N., Holbrook M.G., Williamson B.N., Gamble A., Lloyd-Smith J.O., Tamin A., de Wit E., Harcourt J.L., Munster V.J., et al. Aerosol and surface stability of SARS-CoV-2 as compared with SARS-CoV-1. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020;382(16):1564–1567. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2004973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gupta J.K., Lin C., Chen Q. Characterizing exhaled airflow from breathing and talking. Indoor Air. 2010;20(1):31–39. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0668.2009.00623.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dar M., Swamy L., Gavin D., Theodore A. Leveraging all available resources for a limited resource in a crisis. Ann. Am. Thorac. Soc. 2021:409–416. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.202004-317CME. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wilde H., Thomas M., Iwona H., John M.D., Spiros D., Christina P., Andrew D., Samir B., Seth F., Bilal A.M., et al. medRxiv; 2021. The Association between Mechanical Ventilator Availability and Mortality Risk in Intensive Care Patients with COVID-19: A National Retrospective Cohort Study. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hethcote H.W. The mathematics of infectious diseases. SIAM Rev. 2000;42(4):599–653. doi: 10.1137/S0036144500371907. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wells W.F. An Ecological Study of Droplet Infections; 1955. Airborne Contagion and Air Hygiene. An Ecological Study of Droplet infections., Airborne Contagion and Air Hygiene. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Qian H., Li Y., Nielsen P.V., Huang X. Spatial distribution of infection risk of SARS transmission in a hospital ward. Build. Environ. 2009;44(8):1651–1658. doi: 10.1016/j.buildenv.2008.11.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yan Y., Li X., Shang Y., Tu J. Evaluation of airborne disease infection risks in an airliner cabin using the Lagrangian-based Wells-Riley approac. Build. Environ. 2017:79–92. doi: 10.1016/j.buildenv.2017.05.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhang S., Lin Z. Dilution-based evaluation of airborne infection risk - thorough expansion of Wells-Riley model. Build. Environ. 2021;194:107674. doi: 10.1016/j.buildenv.2021.107674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Park S., Choi Y., Song D., Kim E.K. Natural ventilation strategy and related issues to prevent coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) airborne transmission in a school building. Sci. Total Environ. 2021;789:147764. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.147764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vuorinen V., Aarnio M., Alava M., Alopaeus V., Atanasova N., Auvinen M., Balasubramanian N., Bordbar H., Erästö P., Grande R., et al. Modelling aerosol transport and virus exposure with numerical simulations in relation to SARS-CoV-2 transmission by inhalation indoors. Saf. Sci. 2020;130:104866. doi: 10.1016/j.ssci.2020.104866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dada A.C., Gyawali P. Quantitative microbial risk assessment (QMRA) of occupational exposure to SARS-CoV-2 in wastewater treatment plants. Sci. Total Environ. 2021;763:142989. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.142989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Buonanno G., Morawska L., Stabile L. Quantitative assessment of the risk of airborne transmission of SARS-CoV-2 infection: prospective and retrospective applications. Environ. Int. 2020;145:106112. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2020.106112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhou Q., Qian H., Liu L. Numerical investigation of airborne infection in naturally ventilated hospital wards with central-corridor type. Indoor Built Environ. 2017;27(1):59–69. doi: 10.1177/1420326X16667177. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Adhikari U., Chabrelie A., Weir M., Boehnke K., Mckenzie E., Ikner L., Wang M., Wang Q., Young K., Haas C.N., et al. A case study evaluating the risk of infection from middle eastern respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS‐CoV) in a hospital setting through bioaerosols. Risk Anal. 2019;39(12):2608–2624. doi: 10.1111/risa.13389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Xiao S., Li Y., Sung M., Wei J., Yang Z. A study of the probable transmission routes of MERS-CoV during the first hospital outbreak in the Republic of Korea. Indoor Air. 2018;28(1):51–63. doi: 10.1111/ina.12430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hu S., Yan D., Azar E., Guo F. A systematic review of occupant behavior in building energy policy. Build. Environ. 2020;175:106807. doi: 10.1016/j.buildenv.2020.106807. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dedesko S., Stephens B., Gilbert J.A., Siegel J.A. Methods to assess human occupancy and occupant activity in hospital patient rooms. Build. Environ. 2015;90:136–145. doi: 10.1016/j.buildenv.2015.03.029. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Littig S.J., Isken M.W. Short term hospital occupancy prediction. Health Care Manag. Sci. 2007;10(1):47–66. doi: 10.1007/s10729-006-9000-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Feng X., Yan D., Hong T. Simulation of occupancy in buildings. Energy Build. 2015:348–359. https://escholarship.org/uc/item/9j6223kx [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yang G., Jiang M., Ouyang W., Ji G., Xie H., Rahmani A.M., Liljeberg P., Tenhunen H. IoT-Based remote pain monitoring system: from device to cloud platform. IEEE J. Biomed. Health. 2018;22(6):1711–1719. doi: 10.1109/JBHI.2017.2776351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tang H., Ding J., Li C., Li J. A field study on indoor environment quality of Chinese inpatient buildings in a hot and humid region. Build. Environ. 2019;151:156–167. doi: 10.1016/j.buildenv.2019.01.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shi S., Chen C., Zhao B. Air infiltration rate distributions of residences in Beijing. Build. Environ. 2015;92:528–537. doi: 10.1016/j.buildenv.2015.05.027. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cheng P.L., Li X. Air infiltration rates in the bedrooms of 202 residences and estimated parametric infiltration rate distribution in Guangzhou. Energy Build. 2017:219–225. doi: 10.1016/j.enbuild.2017.12.062. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cui S., Cohen M., Stabat P., Marchio D. CO2 tracer gas concentration decay method for measuring air change rate. Build. Environ. 2015;84:162–169. doi: 10.1016/j.buildenv.2014.11.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.ASHARE . 2021. ANSI/ASHRAE/ASHE Standard 170-2021. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nicas M., Nazaroff W.W., Hubbard A. Toward understanding the risk of secondary airborne infection: emission of respirable pathogens. J. Occup. Environ. Hyg. 2017;2(3):143–154. doi: 10.1080/15459620590918466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Thatcher T.L., Lai A.C.K., Moreno-Jackson R., Sextro R.G., Nazaroff William W. Effects of room furnishings and air speed on particle deposition rates indoors. Atmos. Environ. 2002;36:1811–1819. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Li C., Tang H. Comparison of COVID-19 infection risks through aerosol transmission in supermarkets and small shops. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2022;76:103424. doi: 10.1016/j.scs.2021.103424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.To K.K., Tsang O.T., Yip C.C., Chan K., Wu T., Chan J.M., Leung W., Chik T.S., Choi C.Y., Kandamby D.H., et al. Consistent detection of 2019 novel coronavirus in saliva. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2020;71(15):841–843. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wölfel R., Corman V.M., Guggemos W., Seilmaier M., Zange S., Müller M.A., Niemeyer D., Jones T.C., Vollmar P., Rothe C., et al. Virological assessment of hospitalized patients with COVID-2019. Nature. 2020;581(7809):465–469. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2196-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Watanabe T., Bartrand T.A., Weir M.H., Omura T., Haas C.N. Development of a dose-response model for SARS coronavirus. Risk Anal. 2010;30(7):1129–1138. doi: 10.1111/j.1539-6924.2010.01427.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Labat M., Woloszyn M., Garnier G., Roux J.J. Assessment of the air change rate of airtight buildings under natural conditions using the tracer gas technique. Comparison with numerical modelling. Build. Environ. 2012 doi: 10.1016/j.buildenv.2012.10.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]