Abstract

Objectives

To measure the antibody decay after 2 BNT162b2 doses and the antibody response after a third vaccine dose administered 6 months after the second one in nursing home residents with and without prior COVID-19.

Design

Cohort study.

Setting and Participants

Four hundred-eighteen residents from 18 nursing homes.

Methods

Blood receptor-binding domain (RBD)-IgG (IgG II Quant assay, Abbott Diagnostics; upper limit: 5680 BAU) and nucleocapsid-IgG (Abbott Alinity) were measured 21‒28 days after the second BNT162b2 dose, as well as 1‒3 days before and 21‒28 days after the third vaccine dose. RBD-IgG levels of ≥592 BAU/mL were considered as high antibody response. Residents with prior positive quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction on a nasopharyngeal swab or with N-IgG levels above 0.8 S/CO were considered as prior COVID-19 residents.

Results

In prior COVID-19 residents (n = 122), RBD-IgG median levels decreased by 82% in 167 days on average. In the same period, the number of residents with a high antibody response decreased from 88.5% to 54.9% (P < .0001) and increased to 97.5% after the third vaccine dose (P = .02 vs the first measure). In residents without prior COVID-19 (n = 296), RBD-IgG median levels decreased by 89% in 171 days on average. The number of residents with a high antibody response decreased from 29.4% to 1.7% (P < .0001) and increased to 88.4% after the third vaccine dose (P < .0001 vs the first measure).

Conclusions and Implications

The strong and rapid decay of RBD-IgG levels after the second BNT162b2 dose in all residents and the high antibody response after the third dose validate the recommendation of a third vaccine dose in residents less than 6 months after the second dose, prioritizing residents without prior COVID-19. The slope of RBD-IgG decay after the third BNT162b2 dose and the protection level against SARS-CoV-2 B.1.1.529 (omicron) and other variants of concern provided by the high post-boost vaccination RBD-IgG response require further investigation in residents.

Keywords: BNT162b2 vaccine, SARS-CoV-2 spike antibodies, nursing home residents, boost vaccine dose

Nursing home (NH) residents are at high risk for severe COVID-19. Vaccination using the messenger RNA COVID-19 vaccine is safe and effective in adults but is less documented in older persons.1, 2, 3 The humoral response observed in NH residents 21 days after the first BNT162b2 vaccine dose,4 and 14 days5 , 6 and 6 months following the second vaccine dose,7, 8, 9 has been shown to be lower than that observed in health care professionals. In addition, outbreaks of the SARS-CoV-2 variants [B.1.1. 4-7 (alpha) and B.1.617.2 (delta)] have been reported in NHs less than 6 months after the full BNT162b2 vaccination of most residents.8, 10, 11 The low humoral response observed after 2 BNT162b2 doses, associated with reduced vaccine protection some months after the second vaccine dose, has led to recommendations in the US and in other countries such as France of an additional vaccine dose at least 5 months after the second vaccine dose in persons moderately or severely immunocompromised.12 , 13 In France, more than 95% of residents had received a third BNT162b2 dose in September 2021.14

The 6-month postvaccine antibody decay after the second vaccine dose and the antibody response to the third dose have not been quantified in the same NH residents, which does not enable the comparison of the antibody response after 2 and 3 BNT162b2 doses.

We compared IgG levels against the SARS-CoV-2 receptor-binding domain (RBD)-IgG) (1) after 2 doses of BNT162b2, (2) just before the third vaccine dose, and (3) after the third dose. We distinguished those with and without prior COVID-19.

Methods

Since March 2019, around 6000 residents from 122 nursing homes are being prospectively followed in the Montpellier area (French Occitanie region). All residents, with or without prior COVID-19 (outbreaks of wild type SARS-CoV-2 between March 2020 and February 2021; of SARS-CoV-2 B.1.1.7 between February 2021 and October 2021; of B.1.617.2 between July 2021 and October 2021) were offered 2 vaccine doses in January‒February 2021, and a third dose 6 months later. A follow-up of postvaccine antibody response was proposed in residents from 15 nursing homes having faced a COVID-19 outbreak in 2020. Blood testing was performed 21‒28 days after the second vaccine dose, as well as 1‒3 days before and 21‒28 days after the third dose, to assess RBD-IgG (IgG II Quant assay, Abbott Diagnostics; upper limit: 5680 BAU) and nucleocapsid-IgG (Abbott Alinity). RBD-IgG levels of <149 BAU/mL or ≥592 BAU/mL were considered as low or high responses, respectively.15 , 16 Residents with a history of positive quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction on a nasopharyngeal swab or with N-IgG levels above 0.8 S/CO were considered as prior COVID-19 residents. All participants (or their legal representative) provided informed consent. The study was approved by our University Hospital institutional review board. RBD-IgG levels were compared by using the Friedman and Cochran tests, and the multinomial mixed model for repeated measures. The statistical significance threshold was set at 5%. Analyses were performed using the SAS Enterprise Guide, v 7.3 (SAS Institute Inc).

Results

The characteristics of the residents included in the 15 nursing homes are shown in Table 1 . Of the 418 studied residents, 296 had no previous COVID-19 infection (mean age 88 ± 8 years, 74% women) and 122 had prior COVID-19 (88.6 ± 8 years, 81% women). The mean lapse of time between the first and the second RBD-IgG measures were 171 ± 11 and 167 ± 11 days, respectively.

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics of the Residents Studied in 15 NHs

| NHs | Studied Residents, n (%) | Female/Male Sex, n (%) | Age, y Mean (SD) |

Prior COVID-19, n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 38 (9.1) | 28 (73.7)/10 (26.3) | 86.5 (8.7) | 9 (23.7) |

| 2 | 38 (9.1) | 34 (89.5)/4 (10.5) | 92.1 (5.6) | 15 (39.5) |

| 3 | 37 (8.8) | 27 (73.0)/10 (27.0) | 86.4 (8.4) | 4 (10.8) |

| 4 | 14 (3.3) | 10 (71.4)/4 (28.6) | 83.1 (10.6) | 2 (14.3) |

| 5 | 25 (6.0) | 17 (68.0)/8 (32.0) | 84.6 (7.4) | 10 (40.0) |

| 6 | 28 (6.7) | 19 (67.9)/9 (32.1) | 86.8 (7.0) | 8 (28.6) |

| 7 | 26 (6.2) | 20 (76.9)/6 (23.1) | 87.0 (6.8) | 7 (26.9) |

| 8 | 21 (5.0) | 15 (71.4)/6 (28.6) | 86.7 (8.7) | 6 (28.6) |

| 9 | 32 (7.7) | 23 (71.9)/9 (28.1) | 86.6 (7.7) | 9 (28.1) |

| 10 | 34 (8.1) | 28 (82.3)/6 (17.7) | 91.2 (7.3) | 26 (76.5) |

| 11 | 11 (2.6) | 10 (90.9)/1 (9.1) | 92.8 (5.4) | 3 (27.3) |

| 12 | 20 (4. 8) | 15 (75.0)/5 (25.0) | 91.9 (7.2) | 9 (45.0) |

| 13 | 27 (6.5) | 21 (77.8)/6 (22.2) | 87.1 (8.8) | 6 (22.2) |

| 14 | 37 (8.8) | 27 (73.0)/10 (27.0) | 90.4 (5.6) | 8 (21.6) |

| 15 | 30 (7.2) | 23 (76.7)/7 (23.3) | 89.3 (8.2) | 0 (0.0) |

| Total | 418 (100) | 317 (75.8)/101 (24.2) | 88.7 (8.0) | 122 (29.2) |

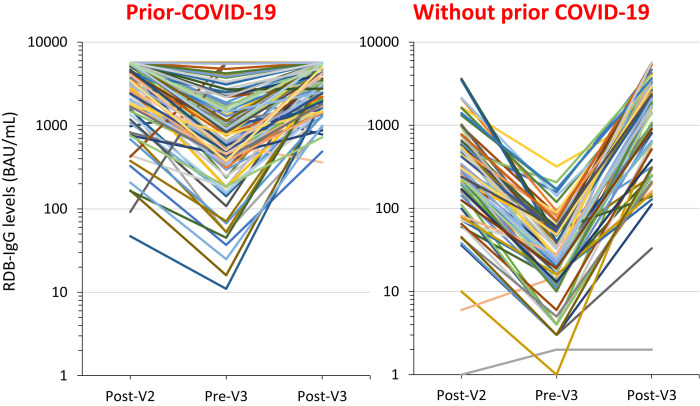

In prior COVID-19 residents, RBD-IgG median levels decreased by 82% between the first and second measures (4318 BAU/mL to 773 BAU/mL), and the number of residents with a high antibody response decreased from 88.5% to 54.9% (P < .0001). After the third dose, RBD-IgG median levels increased significantly (to 3596 BAU/mL), and the number of residents with a high RBD-IgG level was higher after the third and after the second dose (97.5% vs 88.5%, respectively) (P = .02) (Table 2 , Figure 1 ).

Table 2.

RBD-IgG Levels 4‒5 Weeks after the Second BNT162b2 Vaccine Dose (A), 1‒3 days before the Third Vaccine Dose (B), and 4‒5 Weeks after the Third Vaccine Dose (C) of Residents with (n = 122) or without (n = 296) Confirmed Prior COVID-19 Infection

| After the Second Vaccine Dose (A) | Before the Third Vaccine Dose (B) | After the Third Vaccine Dose (C) | P Value∗ | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prior COVID-19 residents (n = 122) | <.0001 | |||

| RBD IgG level, median (IQRs), BAU | 4318 (1772; 5680) | 773 (339; 1742) | 3596 (1751; 5680) | |

| RBD IgG level, no. (%) | <.0001† | |||

| −<149 BAU | 5 (4.1) | 16 (13.1) | 0 | <.001‡ A vs B and B vs C .02‡ A vs C |

| −150‒591 BAU | 9 (7.4) | 39 (32.0) | 3 (2.5) | |

| −≥592 BAU | 108 (88.5) | 67 (54.9) | 119 (97.5) | |

| Without prior COVID-19 residents (n = 296) | <.0001 | |||

| RBD IgG level, median (IQRs), BAU | 348 (120; 752) | 35 (15; 70) | 1926 (875; 3866) | |

| RBD IgG level, no. (%) | <.0001† | |||

| −<149 BAU | 81 (27.4) | 263 (88.8) | 14 (4.7) | <.0001‡ A vs B, B vs C, and A vs C |

| −150‒591 BAU | 128 (43.2) | 28 (9.5) | 41 (13.8) | |

| −≥592 BAU | 87 (29.4) | 5 (1.7) | 241 (88.4) |

Friedman test.

Multinomial mixed model.

Cochran test.

Fig. 1.

Individual change in RBD-IgG levels between 21 and 28 days after the second BNT162b2 vaccine dose (Post-V2), 1-3 days before the third vaccine dose (Pre-V3), and 21-28 after the third vaccine dose (Post-V3) of residents with or without confirmed prior COVID-19. Between March 2019 and September 2021, residents from nursing homes facing a COVID-19 outbreak had repeated RT-qPCR testing until no new cases were diagnosed. Residents from 18 nursing homes having faced a COVID-19 outbreak in 2020 were proposed to undergo blood testing (i) to follow their post-BNT162b2 vaccine response using SARS-CoV-2 Receptor-Binding Domain (RBD-IgG) levels (IgG II Quant assay, Abbott Diagnostics; upper limit: 5680 BAU) and (ii) to determine if they had prior COVID-19, using IgG antibodies against the SARS-CoV-2 nucleocapsid protein (N Protein-IgG) (Abbott Alinity; positive level when above 0.8 S/CO). Blood testing when an informed consent was obtained was performed 21-28 days after the second vaccine dose, 1-3 days before the third dose, and 21-28 days after the third dose in order to make comparisons possible in every resident. To make the illustration more readable, the change in values of RBD-IgG levels 21-28 days after the second vaccine dose, before the third dose administered 6 months after the second dose, and 21-28 days after the third vaccine dose are presented for 100 residents with and 100 residents without prior COVID-19. These residents were drawn at random from the 122 with and the 296 without confirmed prior COVID-19.

In residents without prior COVID-19, RBD-IgG median levels between the first and second measures decreased by 89% (348 BAU/mL to 35 BAU/mL) and the number of residents with a high antibody response decreased from 29.4% to 1.7% (P < .0001). After the third vaccine dose, 88.4% of residents had a high antibody response vs 29.4% after the second dose, and 4.7% had a low antibody response vs 27.4% (P < .0001; Table 2, Figure 1).

Discussion

This preliminary study shows that 6 months after the second BNT162b2 dose, 88.8% of residents without prior COVID-19 have an RBD-IgG level below 149 BAU and only 54.9% of those with prior COVID-19 have an RBD-IgG level above 592 BAU. The 82%‒89% decrease in RBD-IgG level observed in both groups in less than 6 months may partly explain the occurrence of outbreaks of the SARS-CoV-2 variants B.1.1. 4-7 and, more recently, of the Delta variant B.1.617.2 in NHs in which most of the residents had been vaccinated with 2 doses of the BNT162b2 vaccine.8 , 11 This tends to validate, on an immunologic basis, the recommendation of a third BNT162b2 dose at least 5 months after the second one in NH residents. The RBD-IgG response after 3 vaccine doses is significantly higher than that observed after 2 doses and is excellent, largely above 592 BAU, in 97.5% of the residents with prior COVID-19 and in 88.4% of those without. Limitations of the study include the relatively small sample size, with a possible lack of representativeness and the lack of clinical data in residents with prior COVID-19. Whether the severity of the initial infection has impacted the antibody response to the vaccine cannot be analyzed in this study. One other limitation is the lack of neutralization assays. However, we used an automated quantitative assay to measure the RBD IgG level that correlates well with virus neutralization.17 , 18 We did not assess T-cell contribution to vaccine-induced immunity. The present study focuses on antibodies and not on clinical disease. Even if associations have been shown between RBD-IgG levels and protection against SARS-CoV-2 in health care workers and NH residents,8 , 11 , 19, 20, 21 whether the high level of RBD IgG found after a booster BNT162b2 dose in most residents is associated with high protection against COVID-19 remains to be determined.

Because the administration of a booster BNT162b2 dose as well as the vaccination of previously infected individuals generate an anti-B.1.1.529 neutralizing response, with titers 5- to 31-fold lower against Omicron than against Delta,22 further studies are needed to assess whether the high RBD-IgG response found in most of the residents after the third vaccine dose will be sufficient to prevent SARS-CoV-2 B.1.1.529 in those with and without prior COVID-19 and, if so, for what duration.

Conclusions and Implications

The strong and rapid decay of RBD-IgG levels 6 months after the second BNT162b2 dose observed in most of the residents (with very low levels observed after the second dose in residents without prior COVID-19), as well as the high antibody response after the third dose in the residents (observed in the present study and in a recent unpublished study)23 support, on an immunologic basis, the recommendation to offer a third vaccine dose in NH residents at least 5 months after the second dose, prioritizing those without prior COVID-19. Whether the slope of RBD-IgG decay after the third BNT162b2 dose will be similar to that found after the second vaccine dose, and whether the high RBD-IgG response found after the third vaccine dose will be associated with a high protection level against SARS-CoV-2 B.1.1.529 and other variants of concern require further investigation in NH residents.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Jean Bousquet for the interpretation of data, Anna Bedbrook and Fabienne Portejoie for editorial assistance, Secours Infirmiers (Department of Geriatrics, Montpellier University Hospital), Florence Biblocque and Maxime Douville (admission office, Montpellier University Hospital) for material support, and the residents and staff members of the nursing homes involved in the study. None of these contributors received any compensation for their help in carrying out the study.

Footnotes

This research did not receive any funding from agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Benin A.L., Soe M.M., Edwards J.R., et al. Ecological analysis of the decline in incidence rates of COVID-19 among nursing home residents associated with vaccination, United States, December 2020‒January 2021. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2021;22:2009–2015. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2021.08.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cabezas C., Coma E., Mora-Fernandez N., et al. Associations of BNT162b2 vaccination with SARS-CoV-2 infection and hospital admission and death with COVID-19 in nursing homes and healthcare workers in Catalonia: prospective cohort study. BMJ. 2021;374:n1868. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n1868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Polack F.P., Thomas S.J., Kitchin N., et al. Safety and efficacy of the BNT162b2 mRNA COVID-19 vaccine. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:2603–2615. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2034577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Blain H., Tuaillon E., Gamon L., et al. Spike antibody levels of nursing home residents with or without prior COVID-19 3 weeks after a single BNT162b2 vaccine dose. JAMA. 2021;325:1898–1899. doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.6042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Canaday D.H., Carias L., Oyebanji O.A., et al. Reduced BNT162b2 messenger RNA vaccine response in severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2)-naive nursing home residents. Clin Infect Dis. 2021;73:2112–2115. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciab447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Blain H., Tuaillon E., Gamon L., et al. Antibody response after one and two jabs of the BNT162b2 vaccine in nursing home residents: the CONsort-19 study. Allergy. 2022;77:271–281. doi: 10.1111/all.15007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Salmerón Ríos S., Cortés Zamora E.B., Avendaño Céspedes A., et al. Immunogenicity after 6 months of BNT162b2 vaccination in frail or disabled nursing home residents: the COVID-A Study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2022;70:650–658. doi: 10.1111/jgs.17620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pierobon A., Zotto A.D., Antico A. Outbreak of SARS-CoV-2 B.1.617.2 (delta) variant in a nursing home 28 weeks after two doses of mRNA anti-COVID-19 vaccines: evidence of a waning immunity. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2022;28 doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2021.12.013. 614.e5-614.e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Canaday D.H., Oyebanji O.A., Keresztesy D., et al. Significant reduction in vaccine-induced antibody levels and neutralization activity among healthcare workers and nursing home residents 6 months following COVID-19 BNT162b2 mRNA vaccination. Clin Infect Dis. 2021;73:2112–2115. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciab963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Burugorri-Pierre C., Lafuente-Lafuente C., Oasi C., et al. Investigation of an outbreak of COVID-19 in a French nursing home with most residents vaccinated. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4:e2125294. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.25294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Blain H., Tuaillon E., Gamon L., et al. Receptor binding domain-IgG levels correlate with protection in residents facing SARS-CoV-2 B.1.1.7 outbreaks. Allergy. Published online October 15. 2021 doi: 10.1111/all.15142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hall E. Updates to Interim Clinical Considerations for Use of COVID19 Vaccines Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices Meeting. February 4, 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/acip/meetings/downloads/slides-2022-02-04/08-COVID-Hall-508.pdf

- 13.Covid-19: la Haute Autorité de Santé précise les populations éligibles à une dose de rappel de vaccine. https://www.has-sante.fr/jcms/p_3283153/fr/covid-19-la-has-precise-les-populations-eligibles-a-une-dose-de-rappel-de-vaccin

- 14.Le tableau de bord de la vaccination en France. https://solidarites-sante.gouv.fr/grands-dossiers/vaccin-covid-19/article/le-tableau-de-bord-de-la-vaccination

- 15.Khoury D.S., Cromer D., Reynaldi A., et al. Neutralizing antibody levels are highly predictive of immune protection from symptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infection. Nat Med. 2021;27:1205–1211. doi: 10.1038/s41591-021-01377-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Van Praet J.T., Vandecasteele S., De Roo A., et al. Humoral and cellular immunogenicity of the BNT162b2 mRNA Covid-19 Vaccine in nursing home residents. Clin Infect Dis. 2021;73:2145–2147. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciab300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Salazar E., Kuchipudi S.V., Christensen P.A., et al. Convalescent plasma anti-SARS-CoV-2 spike protein ectodomain and receptor-binding domain IgG correlate with virus neutralization. J Clin Invest. 2020;130:6728–6738. doi: 10.1172/JCI141206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang Z., Schmidt F., Weisblum Y., et al. mRNA vaccine-elicited antibodies to SARS-CoV-2 and circulating variants. Nature. 2021;592:616–622. doi: 10.1038/s41586-021-03324-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bergwerk M., Gonen T., Lustig Y., et al. Covid-19 Breakthrough infections in vaccinated health care workers. N Engl J Med. 2021;385:1474–1484. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2109072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Feng S., Phillips D.J., White T., et al. Oxford COVID Vaccine Trial Group Correlates of protection against symptomatic and asymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infection. Nat Med. 2021;27:2032–2040. doi: 10.1038/s41591-021-01540-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gilbert P.B., Montefiori D.C., McDermott A.B., et al. Immune Assays Team; Moderna, Inc. Team; Coronavirus Vaccine Prevention Network (CoVPN)/Coronavirus Efficacy (COVE) Team; United States Government (USG)/CoVPN Biostatistics Team Immune correlates analysis of the mRNA-1273 COVID-19 vaccine efficacy clinical trial. Science. 2022;375:43–50. doi: 10.1126/science.abm3425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Planas D., Saunders N., Maes P., et al. Considerable escape of SARS-CoV-2 Omicron to antibody neutralization. Nature. 2021;73:2145–2147. doi: 10.1038/s41586-021-04389-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Canaday D.H., Oyebanji O.A., White E., et al. Significantly elevated antibody levels and neutralization titers in nursing home residents after SARS-CoV-2 BNT162b2 mRNA booster vaccination. medRxiv. 2021 doi: 10.1101/2021.12.07.21267179. [DOI] [Google Scholar]