Abstract

The incorporation of checkpoint inhibitors into the treatment armamentarium of oncologic therapeutics has revolutionized the course of disease in a myriad of cancers. This has spurred clinical trial evaluation of other novel immunotherapy agents with varying level of success. This review explores possible explanations for differences in efficacy in clinical outcomes amongst currently FDA approved immunotherapy agents, lessons learned from clinical trial failures of investigational immunotherapies, and methods to improve success in the future. An inherent challenge of early phase immunotherapy trials is identifying maximal tolerated dose and understanding pharmacokinetics/pharmacodynamics as immunotherapies exert their effects indirectly via T cells rather than directly via dose dependent cytotoxic activity. The wide heterogeneity of the immune system amongst different patients and an individual patient over time largely affects the results of optimal dose and toxicity finding studies as well as the effectiveness of immunotherapy. Therefore, optimization of phase I/II study design is crucial for clinical trial success. These differences may also help elucidate the lack of immunotherapy benefit in certain disease subtypes despite presence of specific biomarkers. Broader investigation of the tumor microenvironment and its dynamic nature can help to identify alternative pathways for targeted therapies, mechanisms of immunotherapy resistance, and more correlative biomarkers. Finally, manipulation of the tumor microenvironment via a single agonist or antagonist may be inadequate and therefore assessment of combination therapies and sequencing of agents must be further investigated while balancing cumulative toxicity risk.

1. Introduction

The landscape of oncologic therapeutics has been revolutionized by checkpoint inhibitors (CPIs). Historically, the backbone of treatment in most solid malignancies has been cytotoxic chemotherapies. Efforts to improve treatment modalities have focused on improving tolerability while also increasing disease response and maintaining prolonged response to therapy. Identification of specific tumor driver mutations and select cancer biomarkers have led to the emergence of new targeted therapies and heralded an era of personalized medicine in order to achieve these aims. Additionally, over the past decade, advancements in the field of immunotherapy have spurred interest in further understanding and harnessing the power of the innate and adaptive immune system.

Of particular pharmaceutical and clinical interest is the tumor immune microenvironment (TME), which consists of interactions between T cells, antigen presenting cells, tumor cells, and cytokines, in a milieu of supporting matrix. The normal immune system pathways maintain immune homeostasis and prevent autoimmunity, while responding to infections and malignancies. Accordingly, the immune system may have the capacity to distinguish cancer cells from normal tissue. By therapeutically manipulating T cell activity via various co-stimulatory receptor agonists and inhibitor signal antagonists, an anticancer response can be elicited [1]. Effectively, immunotherapy promotes antitumor effects of T cells by mobilizing a patient’s own immune system to target malignant cells. Modulation of memory T cell responses can enable long term anamnestic protection against tumor cells [2], which can lead to prolonged responses.

In 2011, ipilimumab became the first CPI to impact survival and was approved by the FDA for unresectable metastatic melanoma and by 2014, pembrolizumab and nivolumab were approved for advanced melanoma[3–5]. CPIs, which at the time of this writing include the CTLA-4 inhibitor ipilimumab, PD1 inhibitors (nivolumab, pembrolizumab, and cemiplimab), and PD-L1 inhibitors (durvalumab, atezolizumab, and avelumab), have been a major breakthrough in oncology, especially in various cancer sites in which prognosis was particularly grim. For example, pembrolizumab more than doubled overall survival in advanced non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) with high PD-L1 scores and nivolumab more than tripled median overall survival in advanced melanoma regardless of PD-L1 score when compared to traditional chemotherapy [6, 7]. This class of therapy continues to show efficacy in an actively expanding list of malignancies. The extraordinary responses to these first-generation immunotherapies have been the impetus for identifying novel therapies to target other sites within the immune microenvironment such IDO, ICOS, OX40, TIM3, GITR, STING, LAG-3, CSF-1, and oncolytic viruses. Unfortunately, successes have been countered by a multitude of unsuccessful trials as well.

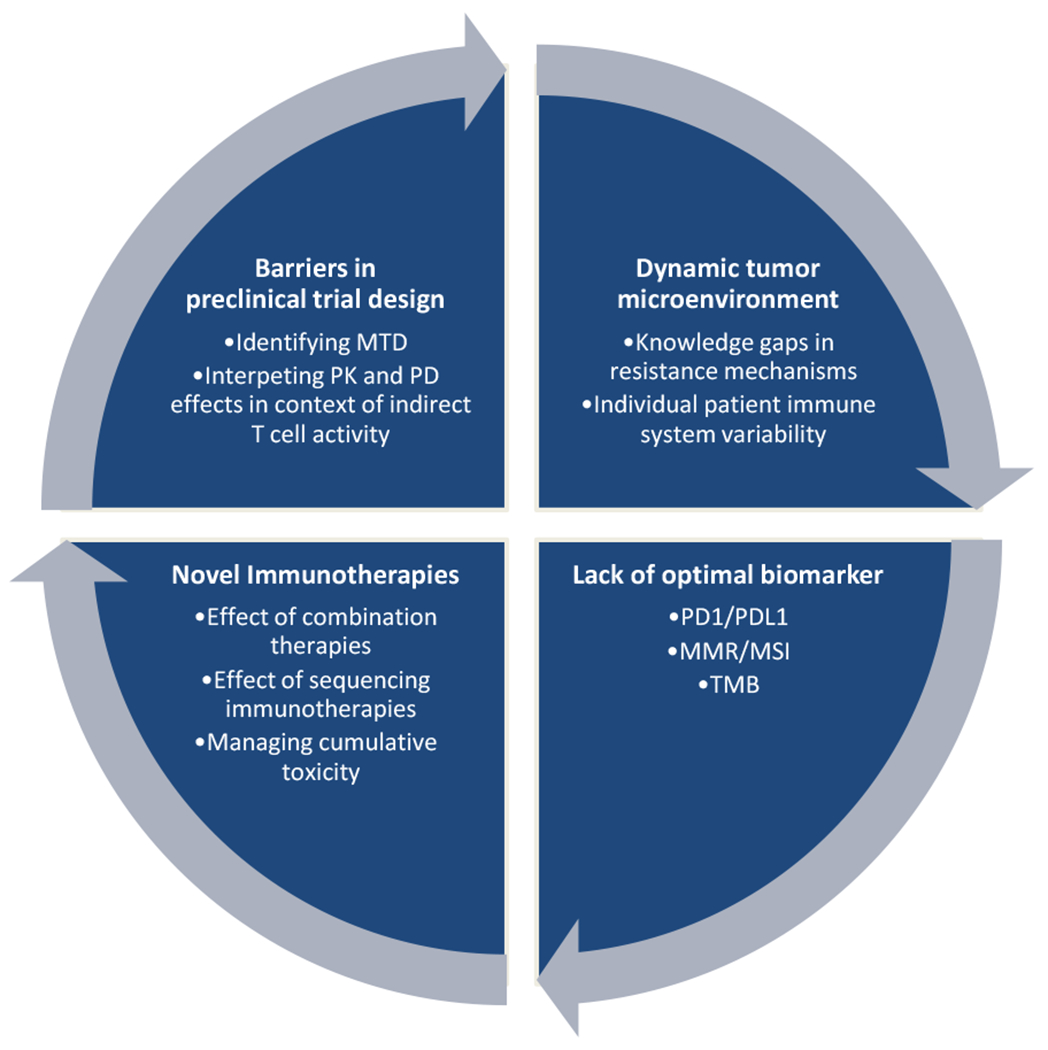

Unsuccessful trials carry both clinical and financial toxicity. Between 2006 and 2014, the number of clinical trials conducted in the United State nearly doubled and from 2015 to 2017, combination therapy trials including CPIs more than tripled [8] [9]. Secondary to the highly-competitive environment and potential financial gain, pharmaceutical companies are eager to recognize early signals of efficacy in phase I trials with hopes of translating them to an FDA approval with a phase III trial [10]. This practice, in particular, has been largely ineffective. Here, we explore lessons learned from prior successes and failures in immunotherapy drug development (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Challenges to Immunotherapeutic Drug and Clinical Trial Development. MMR, mismatch repair; MSI, microsatellite instability; MTD, maximum tolerated dose; PD, pharmacodynamics; PD1/PDL1, programmed death 1/programmed death ligand 1; PK, pharmacokinetics; TMB, tumor mutation burden.

2. Lesson Learned from Prior Immunotherapy Trials

2.1. Importance of Tumor Type

CPIs have shown durable responses, improved overall survival, and unique, generally favorable toxicity profiles when compared to traditional cytotoxic chemotherapy. These responses can vary drastically across tumor types. In the initial phase I/II study of nivolumab, the expansion cohort groups included patients with NSCLC, melanoma, renal cell carcinoma (RCC), castration-resistant prostate cancer (CRPC), and colorectal cancer (CRC) in 2nd or later line setting. Overall response rates were 17% for patients with NSCLC, 31% with melanoma, and 29% with RCC—but no responses were seen in the CRC or CRPC groups [11]. The remarkable survival data noted in this study led to phase III trials in NSCLC, melanoma, and RCC which confirmed efficacy of CPIs in these disease subtypes [12–14]. On the other hand, there has been no meaningful clinical activity for single agent checkpoint inhibition in the vast majority of patients with metastatic CRC or CRPC except for the approximately 3-4% of patients who harbor deficiency in mismatch repair genes or have high microsatellite instability [15][16], despite early evidence for broader efficacy in preclinical studies [17, 18]. The drastic differences in response between cancer disease sites illustrate the effect of patient selection and tumor type on outcomes in early clinical trials. Unfortunately, this has also created an impediment in exploring newer approaches in patients with “immunologically cold” tumors.

2.2. Importance of Biomarker Selection

Outside of individual cancer disease sites, various biomarkers have been studied to better identify which patients may respond. Identification of a single surrogate marker for immunotherapy response across all malignancies and different classes of immunotherapy has been a challenge, in part due to the dynamic nature of the TME and the complexity of inhibitory and stimulatory signaling that occurs in the immune system. [19]. While across most disease sites response rate has had some correlation to degree of PD-L1 tumor expression, there is lack of predictive therapeutic relevance in patient who test negative and in current standardization for PD-L1 testing or cutoff values. Two separate assays may provide discordant results from the same sample, and results in a single patient may vary depending on biopsy of primary or metastatic site.[19, 20]. Discordance also occurs within the same biopsy site, and expression is influenced by prior therapy.

In similarly designed separate phase III evaluations of pembrolizumab and nivolumab in first line metastatic or recurrent NSCLC compared to standard chemotherapy, the outcomes were unique based on differences in PD-L1 tumor marker cutoffs. Of note, two separate PD-L1 assays were utilized in these studies. In the nivolumab trial (CheckMate-026) in which a PD-L1 cutoff of > 5% was used, there was no statistically significant improvement in progression free survival (PFS) or overall survival (OS) when compared to standard chemotherapy. [21] However, in the pembrolizumab trial which used a PD-L1 cutoff of >50%, the median PFS and OS were improved [22].

Malignancies with high neoantigen burden have demonstrated response to immunotherapy potentially via induction of the adaptive immune system in response to neoantigen production. These malignancies include lung cancer and melanoma caused by damage from tobacco and ultraviolet light exposure, respectively, and also in cancers caused by DNA repair pathway mutations such colon cancer with mismatch repair deficiency (MMR-D) or high microsatellite instability (MSI-H). [19]. Tumor mutation burden (TMB) has been one marker studied as a correlative to neoantigen burden and immunotherapy response. While a TMB of 10 or more mutations per megabase has improved response and PFS in patients with NSCLC with ipilimumab and nivolumab, OS benefit was not seen [23, 24]. Additionally, no difference in outcomes was seen with pembrolizumab in NSCLC with a TMB cutoff of 175 mutations per exome [25, 26]. Therefore, the role of TMB as biomarker is undetermined at this time. On the other hand, microsatellite instability (MSI) or mismatch repair deficiency (MMR) which have been historically studied in colon cancer [27], have also recently shown correlation with immunotherapy response in other cancer types, though only 2% of screened patients harbored MMR deficiency [28]. Accordingly, a “one size fits all” approach cannot necessarily be applied to all tumor marker testing in future immunotherapy trials.

2.3. Importance of Drug and Combination Selection

The specific clinical efficacy differences within classes of CPIs has not been compared in head to head studies. On a molecular level, nivolumab and pembrolizumab are both IgG4 anti-PD1 monoclonal antibodies which block the interaction of PD-1 to the ligands, PD-L1 and PD-L2 and very weakly induce complement activation. Nivolumab is fully human while pembrolizumab is humanized. These therapies share similar pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamics properties. [29]. However, a number of clinical studies of pembrolizumab and nivolumab have been completed in what appear to be similar populations with similar study designs. It is intriguing to note the relative success of pembrolizumab compared to nivolumab in these indications [21, 22] While such observations cannot be considered proof of a difference, they are at least hypothesis generating.

The relevance of anti-drug antibody (ADA) is uncertain. Monoclonal antibodies, in particular, can illicit an immune response against the drug itself. Antibodies can be neutralizing, potentially negating the effect of the drug. Studies on the immunogenicity of CPIs have been done. A potentially significant ADA has been detected against ipilimumab with a small study associating its development with shortened survival [30]. The development of ADA to nivolumab and pembrolizumab has been reported at 12.7% and 3.6%, respectively [31, 32] though the clinical significance of this is unknown. In the absence of a head-to-head comparison, pharmaceutical companies should carefully consider variables that may have clinical impact, such as ADA development or the specificity and sensitivity of a biomarker to select a given population.

Since the initial efficacy data for single agent CPI therapy, further progress has been made in analyzing efficacy and tolerability of combination therapies. In metastatic melanoma, the addition of nivolumab to ipilimumab more than doubled median overall survival time [14]. Additionally, in disease sites such as metastatic prostate cancer where single agent checkpoint inhibition has been unsuccessful, dual checkpoint inhibition has shown efficacy in early clinical trials [33]. Combination of immunotherapy with cytotoxic chemotherapy has also been studied with the hypothesis that chemotherapy-mediated cell death and presentation of released antigens may enhance immunogenic responses by T cells and thereby improve the rate and duration of response. [34] The efficacy of this strategy is supported by results of the KEYNOTE-189 trial which evaluated the addition of first line pembrolizumab to standard chemotherapy (carboplatin and pemetrexed) and revealed improved overall survival with combination therapy across all PD-L1 scores, including those with scores <1%, despite the fact that a pemetrexed-based regimen includes supraphysiologic doses of glucocorticoid premedication which is classically associated with immunosuppression. [35]. In addition, the sequencing of immunotherapy may also play an important role. For example, a novel investigational CSF-1R antibody had greater efficacy when administered after or concurrently with a CTLA-4 inhibitor, whereas anti-OX40 antibody was more efficacious when administered before but not after a PD-1 inhibitor. [36, 37]. Additionally, the sequencing of administration with chemotherapy and/or targeted therapy must be considered. The Sequential Combo Immuno and Target Therapy (SECOMBIT) is one such trial, which aims to help answer some of these pressing questions.

Benefits of combination therapy must be carefully weighed against added toxicity. In patients with metastatic melanoma treated with combination nivolumab 1 mg/kg with ipilimumab 3 mg/kg every 3 weeks for 4 doses and then single agent nivolumab onwards had a significantly higher rate of grade 3 or 4 adverse events (59%) when compared to those patients who received either nivolumab or ipilimumab as a single agent (22% and 28%, respectively) [14]. Despite improved survival in this population with combination therapy, physicians treating metastatic melanoma do not standardly prescribe the combination regimen to all on basis of toxicity risk [14]. In order to capitalize on the improved survival but minimize toxicity, the inverse dosing regimen has been studied. Patients who received nivolumab at 3 mg/kg dose with ipilimumab at 1 mg/kg dose were compared with patients who received nivolumab at 1 mg/kg and ipilimumab at 3 mg/kg dose, with both regimens followed by same dose single agent nivolumab. The patients in the former group had a decrease in grade 3-5 adverse events without decrease in efficacy [38].

2.4. Importance of Early Phase Studies

Phase I trials have long been seen as an opportunity to understand the maximally tolerated dose of a drug and have been used with efficiency to exploit this need. Phase I trials have historically had only about 10% rate of response [39]. In the era of immunotherapy, respective responses in phase I studies have been much higher and have led to FDA accelerated approval based on phase I/II data in many cancer disease sites. [4, 27, 40–45]. As an example, phase I clinical study of pembrolizumab began in 2011 and within 3 and 5 years, respectively, this therapy gained FDA approval for unresectable or metastatic melanoma and PD-L1 expressing metastatic NSCLC. [46] The rapid procession of phase I to phase III studies has been enabled by the use of expansion cohorts which circumvent the traditional drug development schema and provides for shortened drug-development timelines. [47].

In the hopes of providing patients important new therapies, the FDA adopted accelerated approval pathways, contingent upon confirmatory studies for full approval. While this is a laudable and important effort, phase I/II trial successes have not always been “confirmed” in the subsequent phase III setting and these instances prompt a close evaluation of modern clinical trial design in the era of immunotherapy. For example, in patients with advanced urothelial carcinoma, atezolizumab showed no improvement in overall survival over chemotherapy in patients with platinum refractory disease with PD-L1 overexpression, despite phase II evidence revealing improved overall response rate when compared to historical controls [48, 49]. Similarly in small cell lung cancer (SCLC), nivolumab gained accelerated FDA approval for advanced disease that had progressed on platinum based therapy based on phase I/II and a randomized expansion cohort which revealed an ORR of 10% with nivolumab monotherapy and a 23% response rate in the nivolumab/ipilimumab combination group[44]. However, phase III study of single agent nivolumab failed to improve survival over chemotherapy in the 2nd line setting [50]. Additionally, combination nivolumab/ipilimumab failed to show efficacy as maintenance therapy after first line chemotherapy in SCLC [51].

While more rapid FDA approval can allow potentially life-prolonging therapies onto the market sooner, clinical trial failures should prompt a closer review regarding the safety of these approvals. In an effort to speed drug development, lessen the number of patients treated with an inadequate dose, decrease the total number of patients needed in a trial, and to enhance confidence regarding the maximum tolerated dose (MTD), a number of designs have been implemented over the “standard” 3 + 3 design. However, phase I trials are often critical in understanding dosing frequency and schedule and better characterizing pharmacokinetic (PK) and pharmacodynamic (PD) effects. Notably, there are inherent challenges to early phase study design in the era of immunotherapy that warrants further discussion. Specifically, MTD becomes difficult to define as the effect of immunotherapy is exerted indirectly via T cell effects rather than a dose-dependent cytotoxic activity. Additionally, immune side effects from immunotherapy do not necessarily occur in the first cycle which affects identification of dose limiting toxicities. [9]. Unique immune system variability among patients poses an additional challenge in identifying optimal dosage not only in terms of efficacy but also timing, severity, and type of adverse immune events.

Use of RECIST criteria may also underestimate response to immunotherapy in an uncommon but notable phenomenon called “pseudo-progression.” This may be considered when a response to immunotherapy is seen after an apparent initial increase in tumor burden. While <10% of patients demonstrate this [52], it has been associated with improved survival. On the other hand, “hyper-progression” describes a true unexpected rapid progression on immunotherapy which is a poor prognostic sign but likely occurs in part via a similar mechanism of T cell infiltration into the tumor [53]. Using RECIST criteria, pseudo-progression would also be character progressive disease despite the former actually being favorable [52]. Therefore an immune-related response criterion has been developed (iRECIST) to guide response evaluation, which does not automatically define such progression. [54]

Phase I trials have historically focused on a heterogenous “all-comers” population of solid tumor and lymphoma in which there was also the potential to realize a particularly promising disease site to explore further. However, it is becoming increasingly common to restrict phase I to specific disease sites, even in the dose escalation phase, due to biases from preclinical studies, other clinical studies, competitive information, or sponsor disease preference given potential market share. When the disease site is restricted, the number of patients treated is small, leading to unrecognized biases and challenges in determining efficacy. Broadly speaking, this practice does not appear to inform positive pivotal phase III outcomes.

2.5. Importance of Identifying Resistance Mechanisms and Immunotherapeutic Targets outside of Cytotoxic T cell Activity

An important development in our understanding of the TME is that mechanisms outside of cytotoxic T cells can be affected by CPIs for anti-tumor immune activation and also serve as a mechanism of resistance to these agents. For example, ipilimumab was designed to block signals of suppression to cytotoxic T cells to facilitate anti-tumor activity but a second key mechanism is with CTLA-4 targeted inhibition of T regulatory cells (Tregs) [55]. Tregs normally maintain immune homeostasis and self-tolerance and counterbalance cytotoxic T cell function. [56]. However, with Treg inhibition, tumor immune evasion may be overcome. Tregs inside the TME may also utilize alternative pathways to maintain immunosuppression which are under active preclinical and clinical investigation [55].

Interestingly, drugs within the same class of immunotherapy can have differences in secondary mechanisms of adaptive immune activation which can be critical to clinical outcomes. The two most widely studied CTLA-4 inhibitors, ipilimumab and tremilimumab were both evaluated in separate trials in metastatic melanoma. While ipilimumab was found to statistically improve overall survival, tremilimumab failed to show improvement over standard chemotherapy. [57, 58] The divergence in efficacy has been attributed in part to the fact that the ipilimumab IgG1 isotype may enable antibody dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity and complement dependent cytotoxicity, whereas the tremilimumab IgG2 isotype does not [59].

Efforts to boost T cell mediated immune response of CPIs have also been studied. Talimogene laherparepvec (T-VEC) is a HSV-1 derived oncolytic immunotherapy designed to work similarly to traditional vaccines but with the goal of antitumor immunity via increased antigen presentation and T cell priming [60]. In advanced melanoma, T-VEC showed promising single agent activity, which improved when combined with CPI therapy [61, 62].

Mechanisms of resistance also exist in the innate immune system including the vasculature and myeloid derived immune suppressor cells. Tumor vasculature is marked by suboptimal vessel network which can facilitate immune evasion and also decrease delivery of therapy and cytotoxic T cells to the tumor [63]. Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) signaling promotes vessel formation in normal physiologic state but can be overexpressed in solid tumors causing dysfunctional vasculature and may promote Treg, myeloid derived suppressor cell, and tumor associated macrophage immunosuppressive activity [63–65]. Targeting of VEGF with bevacizumab has been efficacious in a variety of chemotherapy combinations, and more recently in combination with checkpoint inhibition [66–70].

3. Current and Future Direction

The immune system is complex with numerous inhibitory and stimulatory factors aimed at mounting an appropriate response (largely to foreign antigens), while minimizing damage to the host. In short, this complex interplay is not readily circumvented through the manipulation of a single agonist or antagonist and will require a much more nuanced approach through further technologic innovation. Other mechanisms of adaptive immune resistance are actively being studied to find novel ways of overcoming T cell exhaustion and gaining neoantigen exposure to T cells [71]. Additionally, by addressing immunosuppressive pathways in the innate immune system such as myeloid cells and tumor vasculature, we may expand disease sites in which immunotherapy may be efficacious. [55].

Success of these endeavors relies on optimizing preclinical and early clinical studies to identify key on target and off target effects, dosing, and pharmacologic properties. Companion biomarker identification can significantly contribute to selection of tumor types in which these agents are successful. Combination immunotherapeutic regimens require careful safety analysis as clinically significant improvements in efficacy may not always outweigh the harm associated with cumulative toxicity.

Necessity of these measures is illustrated by the recent data on indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase (IDO) inhibitor, epacadostat. The IDO pathway takes part in CTLA-4 and CD40 mediated immune regulation and has been hypothesized as a potential mechanism of resistance to CPIs. Expression of IDO as a tumor marker on various tumor types had been reported making this a particularly attractive target for therapy [72, 73]. Epacadostat was tested with three CPIs: ipilimumab, pembrolizumab, and nivolumab with promising results [74–76]. In phase I analysis with ipilimumab, preliminary efficacy results suggested a robust response rate of 26% which compares quite favorably with historic controls of ipilimumab alone, which are closer to 10-15%. It is notable that the previously well tolerated single-agent epacadostat dose of 300 mg twice daily lead to unexpected hepatic transaminase elevation when combined with ipilimumab, leading to necessary but significant dose reductions of epacadostat [74]. In a companion phase I trial of epacadostat with pembrolizumab, Mitchell et al. reported an apparent 55% response rate in melanoma, and responses were also realized in NSCLC, RCC, urothelial, head and neck, and endometrial cancer. As surprising, however, was that a maximally tolerated dose of the IDO inhibitor was not found and 300 mg twice daily with the PD-1 inhibitor did not lead to a significant increase in adverse events[75].

The subsequent phase III trial in patients with metastatic melanoma was disappointingly negative and led to the closure of other phase III attempts in other disease sites [77]. In this situation, the phase I results regarding efficacy were clearly influenced by factors not readily recognized in the patient population. In hindsight, perhaps the better-than-expected tolerability profile, in stark contrast to the ipilimumab combination, could have offered some insight. It is usually more plausible to predict that an adverse event profile may run in parallel to enhanced efficacy. While not definitive, the lack of new or worsening adverse events may provide sponsors and investigators a rationale to more carefully consider efficacy and safety in the phase II setting before embarking on a phase III strategy.

Nonetheless, other promising targets in the TME continue to be under active investigation with the aim of improving response to novel immunotherapy and overcoming resistance mechanisms to CPI therapy, particularly by targeting co-expression of inhibitory receptors. One such target is ICOS (inducible co-stimulator), which was found to be up-regulated on peripheral T cells after ipilimumab therapy which makes this target rational for combination immunotherapy. JTX-2011 is an IgG1 antibody which targets the ICOS pathway in order to activate T effector cells but also to reduce intra-tumoral Tregs based on preclinical data. In the ICONIC phase I/II trials, JTX-2011 was studied alone and in combination with nivolumab in patients with heavily pretreated disease. In the phase I arm, all solid tumors were studied regardless of ICOS expression and in the phase II arm, only patients with high ICOS expression were included. Disease control rate was approximately 20% as monotherapy and 30% when combined with nivolumab and the emergence of an ICOS high CD4 T cell population while on therapy was associated with increased antitumor activity. However, this trial had a high early discontinuation rate (60%) for unclear reasons despite less grade 3 to 4 toxicities when compared to other immunotherapy combinations. [78]. These rates of discontinuation must be more closely explored as potential barriers to success in later phase studies.

4. Conclusions

In summary, the human immune response is a highly regulated and involves complex interactions of agonists and antagonists. While we have witnessed great success and broad applicability of immunotherapeutics, there have likewise been a number of disappointing results secondary to a failure to translate encouraging preclinical and early clinical data into phase III trials. Unfortunately, there are numerous factors which significantly impede our full understanding of the immune system and its interaction with tumors. These include, but are by no means limited to theoretical anti-drug antibody effects, suboptimal biologic dose, resistance mechanisms, and the dynamic nature of the tumor microenvironment. Success of late phase clinical trials rely on optimizing preclinical and early clinical studies to identify key on target and off target effects, dosing, and pharmacologic properties. Associated biomarker identification can significantly contribute to selection of tumor types in which these agents are successful. Combination immunotherapeutic regimens require careful safety analysis as clinically significant improvements in efficacy may not always outweigh the harm associated with cumulative toxicity. Ultimately, the future of the immunotherapeutic armamentarium will depend on a more measured approach in early clinical trials, while we continue to unravel the mysteries of the tumor microenvironment in preclinical studies.

Key Points:

Checkpoint inhibitors have transformed the landscape of oncologic care and prompted investigation of novel immunotherapeutic agents, many of which have been unsuccessfully in clinical trial investigation.

Further understanding of the dynamic and complex tumor microenvironment is crucial to identify mechanisms of resistance, novel targets and correlative biomarkers, and optimal treatment combinations and sequencing.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST:

Shazia Nakhoda declares that she has no conflicts of interest that might be relevant to the contents of this manuscript. Anthony J. Olszanski sits on advisory boards, with commensurate honorarium, for Array, BMS, Merck, Novartis, and Pfizer. Additionally, the institution receives funding from trials for which he is participating including Adaptimumne, Astellas, BMS, Boston Biomedical, Checkmate Pharmaceutical, EMD Serono, Glyconex, Immoncore, Incyte, Intensity Therapeutics, Kadmon, Kartos, Kura, Nektar, NGM Biopharmaceutical, Oncoceutics, OncoSec, Seattle Genetics, Sound Biologics, Spring Bank, Takeda, and Targovax

References

- 1.Pardoll DM, The blockade of immune checkpoints in cancer immunotherapy. Nat Rev Cancer, 2012. 12(4): p. 252–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sharpe AH and Pauken KE, The diverse functions of the PD1 inhibitory pathway. Nat Rev Immunol, 2018. 18(3): p. 153–167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hodi FS, et al. , Improved survival with ipilimumab in patients with metastatic melanoma. The New England journal of medicine, 2010. 363(8): p. 711–723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hazarika M, et al. , U.S. FDA Approval Summary: Nivolumab for Treatment of Unresectable or Metastatic Melanoma Following Progression on Ipilimumab. Clin Cancer Res, 2017. 23(14): p. 3484–3488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barone A, et al. , FDA Approval Summary: Pembrolizumab for the Treatment of Patients with Unresectable or Metastatic Melanoma. Clin Cancer Res, 2017. 23(19): p. 5661–5665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Reck M, et al. , Updated Analysis of KEYNOTE-024: Pembrolizumab Versus Platinum-Based Chemotherapy for Advanced Non—Small-Cell Lung Cancer With PD-L1 Tumor Proportion Score of 50% or Greater. 2019. 37(7): p. 537–546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ascierto PA, et al. , Survival Outcomes in Patients With Previously Untreated BRAF Wild-Type Advanced Melanoma Treated With Nivolumab Therapy: Three-Year Follow-up of a Randomized Phase 3 Trial. JAMA Oncol, 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ehrhardt S, Appel LJ, and Meinert CL, Trends in National Institutes of Health Funding for Clinical Trials Registered in ClinicalTrials.gov. JAMA, 2015. 314(23): p. 2566–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wages NA, Chiuzan C, and Panageas KS, Design considerations for early-phase clinical trials of immune-oncology agents. Journal for ImmunoTherapy of Cancer, 2018. 6(1): p. 81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Seruga B, et al. , Failures in Phase III: Causes and Consequences. Clin Cancer Res, 2015. 21(20): p. 4552–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Topalian SL, et al. , Nivolumab (anti-PD-1; BMS-936558; ONO-4538) in patients with advanced solid tumors: Survival and long-term safety in a phase I trial. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 2013. 31(15_suppl): p. 3002–3002. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Motzer RJ, et al. , Nivolumab versus Everolimus in Advanced Renal-Cell Carcinoma. New England Journal of Medicine, 2015. 373(19): p. 1803–1813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Paz-Ares L, et al. , Phase III, randomized trial (CheckMate 057) of nivolumab (NIVO) versus docetaxel (DOC) in advanced non-squamous cell (non-SQ) non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). Journal of Clinical Oncology, 2015. 33(18_suppl): p. LBA109–LBA109. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hodi FS, et al. , Nivolumab plus ipilimumab or nivolumab alone versus ipilimumab alone in advanced melanoma (CheckMate 067): 4-year outcomes of a multicentre, randomised, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol, 2018. 19(11): p. 1480–1492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Overman MJ, Ernstoff MS, and Morse MA, Where We Stand With Immunotherapy in Colorectal Cancer: Deficient Mismatch Repair, Proficient Mismatch Repair, and Toxicity Management. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book, 2018. 38: p. 239–247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Abida W, et al. , Analysis of the Prevalence of Microsatellite Instability in Prostate Cancer and Response to Immune Checkpoint BlockadeAnalysis of the Prevalence of Microsatellite Instability in Prostate Cancer and Response to Immune Checkpoint BlockadeAnalysis of the Prevalence of Microsatellite Instability in Prostate Cancer and Response to Immune Checkpoint Blockade. JAMA Oncology, 2019. 5(4): p. 471–478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Selby MJ, et al. , Preclinical Development of Ipilimumab and Nivolumab Combination Immunotherapy: Mouse Tumor Models, In Vitro Functional Studies, and Cynomolgus Macaque Toxicology. PLoS One, 2016. 11(9): p. e0161779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hurwitz AA, et al. , Combination immunotherapy of primary prostate cancer in a transgenic mouse model using CTLA-4 blockade. Cancer Res, 2000. 60(9): p. 2444–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Spencer KR, et al. , Biomarkers for Immunotherapy: Current Developments and Challenges. American Society of Clinical Oncology Educational Book, 2016(36): p. e493–e503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McLaughlin J, et al. , Quantitative Assessment of the Heterogeneity of PD-L1 Expression in Non—Small-Cell Lung Cancer Heterogeneity of PD-L1 Expression in Non—Small-Cell Lung Cancer Heterogeneity of PD-L1 Expression in Non—Small-Cell Lung Cancer. JAMA Oncology, 2016. 2(1): p. 46–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Carbone DP, et al. , First-Line Nivolumab in Stage IV or Recurrent Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. N Engl J Med, 2017. 376(25): p. 2415–2426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Reck M, et al. , Updated Analysis of KEYNOTE-024: Pembrolizumab Versus Platinum-Based Chemotherapy for Advanced Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer With PD-L1 Tumor Proportion Score of 50% or Greater. J Clin Oncol, 2019. 37(7): p. 537–546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ready N, et al. , First-Line Nivolumab Plus Ipilimumab in Advanced Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer (CheckMate 568): Outcomes by Programmed Death Ligand 1 and Tumor Mutational Burden as Biomarkers. J Clin Oncol, 2019. 37(12): p. 992–1000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Squibb B-M, Bristol-Myers Squibb Provides Update on the Ongoing Regulatory Review of Opdivo Plus Low-Dose Yervoy in First-Line Lung Cancer Patients with Tumor Mutational Burden ≥10 mut/Mb. 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Langer C Abstract OA04.05. in World Conference on Lung Cancer. 2019. Barcelona, Spain. [Google Scholar]

- 26.M G, Abstract OA04.06, in World Conference on Lung Cancer. 2019: Barcelona, Spain. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Overman MJ, et al. , Nivolumab in patients with metastatic DNA mismatch repair-deficient or microsatellite instability-high colorectal cancer (CheckMate 142): an open-label, multicentre, phase 2 study. Lancet Oncol, 2017. 18(9): p. 1182–1191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Azad NS, et al. , Nivolumab Is Effective in Mismatch Repair—Deficient Noncolorectal Cancers: Results From Arm Z1D—A Subprotocol of the NCI-MATCH (EAY131) Study. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 2019: p. JCO.19.00818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fessas P, et al. , A molecular and preclinical comparison of the PD-1-targeted T-cell checkpoint inhibitors nivolumab and pembrolizumab. Semin Oncol, 2017. 44(2): p. 136–140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kverneland AH, et al. , Development of anti-drug antibodies is associated with shortened survival in patients with metastatic melanoma treated with ipilimumab. Oncoimmunology, 2018. 7(5): p. e1424674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vugt M.v., et al. , Immunogenicity of pembrolizumab (pembro) in patients (pts) with advanced melanoma (MEL) and non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC): Pooled results from KEYNOTE-001, 002, 006, and 010. 2016. 34(15_suppl): p. 3063–3063. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Agrawal S, et al. , Evaluation of Immunogenicity of Nivolumab Monotherapy and Its Clinical Relevance in Patients With Metastatic Solid Tumors. 2017. 57(3): p. 394–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sharma P, et al. , Initial results from a phase II study of nivolumab (NIVO) plus ipilimumab (IPI) for the treatment of metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (mCRPC; CheckMate 650). Journal of Clinical Oncology, 2019. 37(7_suppl): p. 142–142. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jenkins RW, Barbie DA, and Flaherty KT, Mechanisms of resistance to immune checkpoint inhibitors. British Journal Of Cancer, 2018. 118: p. 9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gandhi L, et al. , Pembrolizumab plus Chemotherapy in Metastatic Non—Small-Cell Lung Cancer. New England Journal of Medicine, 2018. 378(22): p. 2078–2092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Messenheimer DJ, et al. , Timing of PD-1 Blockade Is Critical to Effective Combination Immunotherapy with Anti-OX40. Clin Cancer Res, 2017. 23(20): p. 6165–6177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Holmgaard RB, et al. , Timing of CSF-1/CSF-1R signaling blockade is critical to improving responses to CTLA-4 based immunotherapy. Oncoimmunology, 2016. 5(7): p. e1151595–e1151595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lebbe C, et al. , Evaluation of Two Dosing Regimens for Nivolumab in Combination With Ipilimumab in Patients With Advanced Melanoma: Results From the Phase IIIb/IV CheckMate 511 Trial. J Clin Oncol, 2019. 37(11): p. 867–875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Horstmann E, et al. , Risks and Benefits of Phase 1 Oncology Trials, 1991 through 2002. New England Journal of Medicine, 2005. 352(9): p. 895–904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Merck, Merck Provides Update on Phase 3 KEYNOTE-119 Study of KEYTRUDA® (pembrolizumab) Monotherapy in Previously-Treated Patients with Metastatic Triple-Negative Breast Cancer 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Finn RS, et al. , Results of KEYNOTE-240: phase 3 study of pembrolizumab (Pembro) vs best supportive care (BSC) for second line therapy in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). 2019. 37(15_suppl): p. 4004–4004. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chuk MK, et al. , FDA Approval Summary: Accelerated Approval of Pembrolizumab for Second-Line Treatment of Metastatic Melanoma. 2017. 23(19): p. 5666–5670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nghiem P, et al. , Durable Tumor Regression and Overall Survival in Patients With Advanced Merkel Cell Carcinoma Receiving Pembrolizumab as First-Line Therapy. J Clin Oncol, 2019. 37(9): p. 693–702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Antonia SJ, et al. , Nivolumab alone and nivolumab plus ipilimumab in recurrent small-cell lung cancer (CheckMate 032): a multicentre, open-label, phase 1/2 trial. The Lancet Oncology, 2016. 17(7): p. 883–895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Suzman DL, et al. , FDA Approval Summary: Atezolizumab or Pembrolizumab for the Treatment of Patients with Advanced Urothelial Carcinoma Ineligible for Cisplatin-Containing Chemotherapy. Oncologist, 2019. 24(4): p. 563–569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Emens LA, et al. , Cancer immunotherapy trials: leading a paradigm shift in drug development. J Immunother Cancer, 2016. 4: p. 42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bates SE, et al. , Advancing Clinical Trials to Streamline Drug Development. Clin Cancer Res, 2015. 21(20): p. 4527–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hoffman-Censits JH, et al. , IMvigor 210, a phase II trial of atezolizumab (MPDL3280A) in platinum-treated locally advanced or metastatic urothelial carcinoma (mUC). 2016. 34(2_suppl): p. 355–355. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Powles T, et al. , Atezolizumab versus chemotherapy in patients with platinum-treated locally advanced or metastatic urothelial carcinoma (IMvigor211): a multicentre, open-label, phase 3 randomised controlled trial. Lancet, 2018. 391(10122): p. 748–757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Reck M, et al. , LBA5Efficacy and safety of nivolumab (nivo) monotherapy versus chemotherapy (chemo) in recurrent small cell lung cancer (SCLC): Results from CheckMate 331. Annals of Oncology, 2018. 29(suppl_10). [Google Scholar]

- 51.Owonikoko TK, et al. , LBA1_PRNivolumab (nivo) plus ipilimumab (ipi), nivo, or placebo (pbo) as maintenance therapy in patients (pts) with extensive disease small cell lung cancer (ED-SCLC) after first-line (1L) platinum-based chemotherapy (chemo): Results from the double-blind, randomized phase III CheckMate 451 study. Annals of Oncology, 2019. 30(Supplement_2). [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wolchok JD, et al. , Guidelines for the Evaluation of Immune Therapy Activity in Solid Tumors: Immune-Related Response Criteria. Clinical Cancer Research, 2009. 15(23): p. 7412–7420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Frelaut M, Le Tourneau C, and Borcoman E, Hyperprogression under Immunotherapy. International journal of molecular sciences, 2019. 20(11): p. 2674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Seymour L, et al. , iRECIST: guidelines for response criteria for use in trials testing immunotherapeutics. The Lancet Oncology, 2017. 18(3): p. e143–e152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Datta M, et al. , Reprogramming the Tumor Microenvironment to Improve Immunotherapy: Emerging Strategies and Combination Therapies. 2019(39): p. 165–174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Liston A and Gray DH, Homeostatic control of regulatory T cell diversity. Nat Rev Immunol, 2014. 14(3): p. 154–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ribas A, et al. , Phase III Randomized Clinical Trial Comparing Tremelimumab With Standard-of-Care Chemotherapy in Patients With Advanced Melanoma. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 2013. 31(5): p. 616–622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hodi FS, et al. , Improved Survival with Ipilimumab in Patients with Metastatic Melanoma. New England Journal of Medicine, 2010. 363(8): p. 711–723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.He M, et al. , Remarkably similar CTLA-4 binding properties of therapeutic ipilimumab and tremelimumab antibodies. Oncotarget, 2017. 8(40): p. 67129–67139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Guo ZS, Liu Z, and Bartlett DL, Oncolytic Immunotherapy: Dying the Right Way is a Key to Eliciting Potent Antitumor Immunity. Front Oncol, 2014. 4: p. 74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Andtbacka RHI, et al. , Talimogene Laherparepvec Improves Durable Response Rate in Patients With Advanced Melanoma. 2015. 33(25): p. 2780–2788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Chesney J, et al. , Randomized, Open-Label Phase II Study Evaluating the Efficacy and Safety of Talimogene Laherparepvec in Combination With Ipilimumab Versus Ipilimumab Alone in Patients With Advanced, Unresectable Melanoma. J Clin Oncol, 2018. 36(17): p. 1658–1667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Jain RK, Antiangiogenesis strategies revisited: from starving tumors to alleviating hypoxia. Cancer Cell, 2014. 26(5): p. 605–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Shitara K and Nishikawa H, Regulatory T cells: a potential target in cancer immunotherapy. Ann N Y Acad Sci, 2018. 1417(1): p. 104–115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ott PA, Hodi FS, and Buchbinder EI, Inhibition of Immune Checkpoints and Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor as Combination Therapy for Metastatic Melanoma: An Overview of Rationale, Preclinical Evidence, and Initial Clinical Data. Front Oncol, 2015. 5: p. 202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Yamazaki K, et al. , Randomized phase III study of bevacizumab plus FOLFIRI and bevacizumab plus mFOLFOX6 as first-line treatment for patients with metastatic colorectal cancer (WJOG4407G). Annals of Oncology, 2016. 27(8): p. 1539–1546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Socinski MA, et al. , Atezolizumab for First-Line Treatment of Metastatic Nonsquamous NSCLC. N Engl J Med, 2018. 378(24): p. 2288–2301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Motzer RJ, et al. , IMmotion151: A Randomized Phase III Study of Atezolizumab Plus Bevacizumab vs Sunitinib in Untreated Metastatic Renal Cell Carcinoma (mRCC). 2018. 36(6_suppl): p. 578–578. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Pishvaian MJ LM, Ryoo B-Y,. Updated safety and clinical activity results from a Phase Ib study of atezolizumab + bevacizumab in hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). in ESMO. 2018. Munich, Germany. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Reck M, et al. , Phase III trial of cisplatin plus gemcitabine with either placebo or bevacizumab as first-line therapy for nonsquamous non-small-cell lung cancer: AVAil. J Clin Oncol, 2009. 27(8): p. 1227–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Fares CM, et al. , Mechanisms of Resistance to Immune Checkpoint Blockade: Why Does Checkpoint Inhibitor Immunotherapy Not Work for All Patients? 2019(39): p. 147–164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.DeMatteo R Targeting IDO: A Novel Immune Checkpoint in GIST. in 2016 ASCO Annual Meeting. 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Schalper KA Significance of PD-L1, IDO-1, and B7-H4 expression in lung cancer. in 2015 ASCO Annual Meeting. 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Gibney GT, et al. , Phase 1/2 study of epacadostat in combination with ipilimumab in patients with unresectable or metastatic melanoma. J Immunother Cancer, 2019. 7(1): p. 80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Mitchell TC, et al. , Epacadostat Plus Pembrolizumab in Patients With Advanced Solid Tumors: Phase I Results From a Multicenter, Open-Label Phase I/II Trial (ECHO-202/KEYNOTE-037). J Clin Oncol, 2018: p. Jco2018789602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Perez RP, et al. , Epacadostat plus nivolumab in patients with advanced solid tumors: Preliminary phase I/II results of ECHO-204. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 2017. 35. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Georgina V. Long RD, Hamid Omid, Gajewski Thomas, Caglevic Christian, Dalle Stéphane, Arance Ana, Carlino Matteo S., Grob Jean-Jacques, Kim Tae Min, Demidov Lev V., Robert Caroline, Larkin James M. G., Anderson James, Maleski Janet E., Jones Mark M., Diede Scott J., Mitchell Tara C. Epacadostat (E) plus pembrolizumab (P) versus pembrolizumab alone in patients (pts) with unresectable or metastatic melanoma: Results of the phase 3 ECHO-301/KEYNOTE-252 study. 2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Yap TA ICONIC: Biologic and clinical activity of first in class ICOS agonist antibody JTX-2011 +/− nivolumab (nivo) in patients with advanced cancers. in American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2018. Chicago. [Google Scholar]