Key Points

Recurrent thrombosis can present in antiphospholipid syndrome despite anticoagulation, antiplatelet, and immunosuppressive therapies.

Complement inhibition may be a therapeutic option for recurrent thrombosis associated with antiphospholipid syndrome.

Abstract

Antiphospholipid syndrome (APS) is characterized by arterial and/or venous thrombosis with antiphospholipid antibodies. Dysregulation of the complement pathway has been implicated in APS pathophysiology. We report the successful use of eculizumab, an anti-C5 monoclonal antibody, in controlling and preventing recurrent thrombosis in a refractory case of APS. An 18-year-old female was diagnosed with APS after developing extensive, unprovoked deep vein thrombosis (DVT) of axillary, inferior vena cava, and brachiocephalic veins. Thrombophilia evaluation revealed triple-positive lupus anticoagulant, β-2 glycoprotein IgM, IgA, and anticardiolipin antibodies (each >40 U/mL) with persistently positive titers after 12 weeks. She was refractory to multiple anticoagulants alone (enoxaparin, fondaparinux, apixaban, rivaroxaban, and warfarin) with antiplatelet (aspirin and clopidogrel) and adjunctive therapies (hydroxychloroquine, immunosuppression with steroids and rituximab, and plasmapheresis). Despite these, she continued to develop recurrent thrombosis and additionally developed hepatic infarction and pulmonary embolism with failure to decrease titers after 6 weeks of plasma exchange. Following this event, eculizumab (600 mg weekly × 4 weeks followed by 900 mg every 2 weeks) was initiated in combination with fondaparinux, aspirin, clopidogrel, and hydroxychloroquine. She has remained on this regimen without recurrence of thrombosis. Our case suggests that eculizumab may have a role as a therapeutic option in refractory thrombosis in APS.

Introduction

Antiphospholipid syndrome (APS) is an autoimmune disorder characterized by arterial or venous thrombosis, recurrent pregnancy loss, and the presence of persistent antiphospholipid antibodies (APA).1 Rarely, APS causes refractory thrombosis affecting small vessels of multiple organ systems or large blood vessels.2 APS affects both sexes; however, it is more commonly recognized in females, with a prevalence of 1 in 2000 Americans.3 It is the most common cause of stroke in young adults, responsible for around 20% deep vein thrombosis (DVT) and 1 in 5 recurrent miscarriages.

More recently, derangements in the complement pathway have been implicated in the pathophysiology of APS.4,5 Complement is a component of the innate immune system and is composed of regulatory proteins and enzymes, consisting of the classical, lectin, and alternate pathways. Eculizumab is a monoclonal antibody that selectively binds complement protein C5, thereby inhibiting cleavage to C5a and C5b, preventing the generation of the terminal complement complex (TCC) C5b-9.6 In refractory APS, eculizumab has been considered a potential treatment option.7,8 Herein, we describe a case of refractory, recurrent venous thromboembolism and hepatic infarction in a patient with APS, successfully treated with eculizumab as part of a multidrug regimen.

Case description

An 18-year-old female, cigarette and marijuana smoker with a past medical history of immune thrombocytopenic purpura presented with acute painful discoloration of the right arm. She was found to have an unprovoked right subclavian DVT extending to the axillary, internal jugular, and superficial brachiocephalic veins requiring catheter-directed thrombolysis. Thoracic outlet syndrome was determined, and a right first cervical rib resection was performed. A laboratory thrombophilia evaluation noted normal protein C and S activity, antithrombin activity, antithrombin antigen, and fasting serum homocysteine. Testing for factor V Leiden and prothrombin G20210A revealed the absence of prothrombotic gene variants. Testing for antiphospholipid antibodies revealed triple positivity for lupus anticoagulant (LA), anti–β-2 glycoprotein I (GPI) IgG 84.9 SGU Units, IgM 76.5 SMU Units, IgA 66.7 SAU Units, and strongly positive IgG and IgM anticardiolipin antibodies (each >40 U/mL; values >20 considered positive). Titers remained positive 12 weeks after initial testing, confirming the diagnosis of APS (Table 1).1,9 The patient was not using hormonal contraception, and testing for other autoimmune diseases was unrevealing.

Table 1.

Chronology of events, anticoagulation, and antiphospholipid antibody titers: eculizumab initiated on 9/4/2019.

| Event | Date | Presentation | Intervention | Prior anticoagulation | Current anticoagulation | Antiphospholipid antibody titers (U) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | 7/2016 | Right subclavian, axillary, internal jugular, brachiocephalic vein thrombosis | Thrombolysis,cervical rib resection | None | Enoxaparin (1 mg/kg twice daily) bridged to warfarin (INR 2-3) | Anti–β-2 GPI: IgG, 84.9 SGU; IgM, 76.5 SMU; IgA, 66.7 SAU.* Antiphosphatidylserine: IgG, 3.9 GPL; IgM, 26.2 MPL; IgA, 2.4 APL. Antiphosphatidylinositol: IgG, 4.5 GPL; IgM, 45.8 MPL; IgA, 0.6 APL. Antiphosphatidylcholine: IgG, 2.4 GPL; IgM, 5.1 MPL; IgA, 0.4 APL. Antiphosphatidylethanolamide: IgG, 6.1 GPL; IgM, 112.6 MPL; IgA, 0.9 APL. Antiphosphatidic acid: IgG, 10.1 GPL; IgM, 211.7 MPL; IgA, 14.1 APL. Antiphosphatidylglycerol: IgG, 16.2 GPL; IgM, 56.5 MPL; IgA, 0.5 APL. Lupus anticoagulant: positive |

| 2. | 11/2016 | Left subclavian vein thrombosis | Thrombolysis | Warfarin (INR 1.1) | Warfarin (INR 2-3) + ASA (81 mg daily) | Anti–β-2 GPI: IgG, 124.9 SGU; IgM, 112.6 SMU; IgA, 66.0 SAU.* Antiphosphatidylserine: IgG, 21.5 GPL; IgM, 39.7 MPL; IgA, 1.8 APL. Antiphosphatidylinositol: IgG, 2.1 GPL; IgM, 12.3 MPL; IgA, 1.8 APL. Antiphosphatidylcholine: IgG, 4.5 GPL; IgM, 8.9 MPL; IgA, 2.2 APL. Antiphosphatidylethanolamide: IgG, 0.6 GPL; IgM, 2.9 MPL; IgA, 0.4 APL. Antiphosphatidic acid: IgG, >120.0 GPL; IgM, 98.2 MPL; IgA, 4.8 APL. Antiphosphatidylglycerol: IgG, 2.0 GPL; IgM, 11.7 MPL; IgA, 1.7 APL. Lupus anticoagulant: positive |

| 3. | 12/2016 | Left common femoral and iliac vein thrombosis | Thrombolysis | Warfarin (INR 1.7) + ASA (81 mg daily) | Apixaban (10 mg twice daily × 7 days, 5 mg twice daily) | Anti–β-2 GPI: IgG, 111.5 GPL-U/mL; IgM, >112 MPL-U/mL; IgA, 34.8 APL-U/mL.* Antiphosphatidylserine: IgG, 18.7 GPL; IgM, 34.4 MPL; IgA 1.6 APL. Antiphosphatidylinositol: IgG, 2.1 GPL; IgM, 7.5 MPL; IgA, 0.8 APL. Antiphosphatidylcholine: IgG, 0.8 GPL; IgM, 11.5 MPL; IgA, 3.8 APL. Antiphosphatidylethanolamide: IgG, 1.4 GPL; IgM, 2.0 MPL; IgA, 1.3 APL. Antiphosphatidic acid: IgG, >120.0 GPL; IgM, 98.9 MPL; IgA, 13.5 APL. Antiphosphatidylglycerol: IgG, 2.8 GPL; IgM, 11.2 MPL; IgA, 0.8 APL. Lupus anticoagulant: positive |

| 4. | 12/2016 | Recurrent Left common femoral and iliac, popliteal vein thrombosis | Thrombolysis and stent placement | Apixaban (5 mg twice daily) | Apixaban (5 mg twice daily) + ASA (81 mg daily) + rituximab (889 mg = 375 mg/m2 × 2.37 m2), weekly × 4 | Per #3 |

| 5. | 2/2018 | Left common femoral to saphenous vein thrombosis | None | Apixaban (5 mg twice daily) + ASA (81 mg daily) | Apixaban (10 mg twice daily × 7 days, 5 mg twice daily) + ASA (81 mg daily) | Anticardiolipin: IgG, 110.7 GPL-U/mL; IgM, >112.0 MPL-U/mL; IgA, 46.0 APL-U/mL.† Anti–β-2 GPI: IgG, 90.5GPL-U/ML; IgM, >112.0 MPL-U/mL; IgA, 38.2 APL-U/mL. Lupus anticoagulant: positive |

| 6. | 3/2018 | Left common femoral vein thrombosis (new thrombus burden) | Thrombolysis and venoplasty | Apixaban (5 mg twice daily) + ASA (81 mg daily) | Apixaban (10 mg twice daily × 7 days, 5 mg twice daily) + ASA (81 mg daily) + clopidogrel (75 mg daily) + hydroxychloroquine (200 mg daily) | Per #5 |

| 7. | 4/2018 | Left leg extensive venous thrombus burden | Thrombolysis + stent | Apixaban (5 mg twice daily) + ASA (81 mg daily) + clopidogrel (75 mg daily) + hydroxychloroquine (200 mg daily) | Enoxaparin (1 mg/kg twice daily) × 1 moHydroxychloroquine (200 mg twice daily) + ASA (81 mg daily) + clopidogrel (75 mg daily). Enoxaparin transitioned to fondaparinux 10 mg daily after approximately 1 mo outpatient | Per #5 |

| 8. | 4/2019 | Hepatic infarction | Plasma exchange × 6 sessions for 50-75% titer reduction goal + methylprednisolone 1000 mg × 3 days, followed by prednisone 60 mg daily | Fondaparinux (10 mg daily + ASA (81 mg daily) + clopidogrel (75 mg daily) | Fondaparinux (10 mg daily) + ASA (81 mg daily) + clopidogrel (75 mg daily) + hydroxychloroquine (200 mg twice daily) + prednisone (60 mg daily) | PREplasma exchange: Anticardiolipin: IgG, 103.5 GPL-U/mL; IgM, >112.0 MPL-U/mL; IgA, 59.3 APL-U/mL; Anti–β-2 GPI: IgG, 82.2 GPL-U/mL; IgM, >112.0 MPL-U/mL; IgA, 42.6 APL-U/mL.† Lupus anticoagulant: positivePOSTplasma exchange: Anticardiolipin: IgG, 111.5 GPL-U/mL; IgM, 60.7 MPL-U/mL; IgA, >65.0 APL-U/mL; Anti–β-2 GPI: IgG, >112.0 GPL-U/mL; IgM, 102.1 MPL-U/mL; IgA, >65.0 APL-U/mL.† Lupus anticoagulant: positiveRepeated 5/2019: Anticardiolipin: IgG, 89.6 GPL-U/mL; IgM, >112.0 MPL-U/mL; IgA, >65.0 APL-U/mL; Anti–β-2 GPI: IgG, >80.3 GPL-U/mL; IgM, >112.0 MPL-U/mL; IgA, >65.0 APL-U/mL.† Lupus anticoagulant: positive |

| 9. | 6/2019 | Evolution of hepatic infarction | None | Fondaparinux (10 mg daily) + ASA (81 mg daily) + clopidogrel (75 mg daily) + hydroxychloroquine (200 mg twice daily) + prednisone (60 mg daily) | Eculizumab (900 mg every alternate week infusion) + fondaparinux (10 mg daily) + ASA (81 mg daily) + clopidogrel (75 mg daily) + hydroxychloroquine (200 mg twice daily) | Anticardiolipin: IgG, 110.1 GPL-U/mL; IgM, 97.7 MPL-U/mL; IgA, 61.2 APL-U/mL; Anti–β-2 GPI: IgG, >112.0 GPL-U/mL; IgM, >112.0 MPL-U/mL; IgA, 52.1 APL-U/mL.† Lupus anticoagulant: positive |

| 10. | 10/2019 | Segmental and subsegmental pulmonary emboli-left lower lobe of lung | None | Eculizumab (900 mg every alternate week infusion) + fondaparinux (10 mg daily) + ASA (81 mg daily) + clopidogrel (75 mg daily) + hydroxychloroquine (200 mg twice daily) | Eculizumab (900 mg every alternate week infusion) + fondaparinux (10 mg daily) + ASA (81 mg daily) + clopidogrel (75 mg daily) + hydroxychloroquine (200 mg twice daily) | Per #9 |

| 11. | 6/2020 | Outpatient follow-up: no new thrombotic event | None | Eculizumab (900 mg every alternate week infusion) + fondaparinux (10 mg daily) + ASA (81 mg daily) + clopidogrel (75 mg daily) + hydroxychloroquine (200 mg twice daily) | Eculizumab (900 mg every alternate week infusion) + fondaparinux (10 mg daily) + ASA (81 mg daily) + clopidogrel (75 mg daily) + hydroxychloroquine (200 mg twice daily) | Anti–β-2 GPI: IgG, 142.4 SGU; IgM, 136 SMU; IgA, >150 SAU.* Antiphosphatidylserine: IgG, 35.2 GPL; IgM, 115.5 MPL; IgA, 5.1 APL. Antiphosphatidylinositol: IgG, 5.0 GPL; IgM, 13.9 MPL; IgA, 2.1 APL. Antiphosphatidylethanolamide: IgG, 2.4 GPL; IgM, 5.0 MPL; IgA, 2.0 APL. Antiphosphatidic acid: IgG, 85.2 GPL; IgM, 82.1 MPL; IgA, 5.8 APL. Antiphosphatidylglycerol: IgG, 43.3 GPL; IgM, 79.9 MPL; IgA, 6.9 APL. Anticardiolipin: IgG, >112.0 GPL-U/mL; IgM, >112.0 MPL-U/mL; IgA, >65.0 APL-U/mL; Anti–β-2 GPI: IgG, >112.0 GPL-U/mL; IgM, >112.0 MPL-U/mL; IgA, >30.9 APL-U/mL.† Lupus anticoagulant: positive |

No evidence of venous or arterial thrombosis since 10/2019 to 01/05/2022.

U, units.

ELISA assay.

Multiplex flow immunoassay.

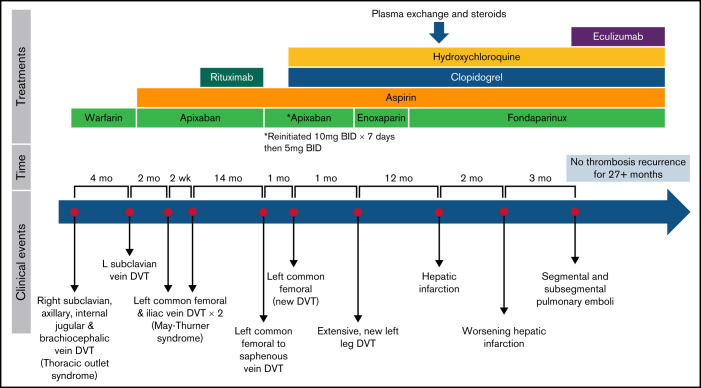

Four months later, while nonadherent to warfarin (international normalized ratio [INR], 1.1), she developed a left upper extremity DVT extending into the left subclavian, cephalic, and basilic veins, again necessitating catheter-directed thrombolysis with continued anticoagulation and addition of antiplatelet therapy, low dose (81 mg/day) aspirin (ASA) (Table 1; Figure 1). There was continued poor adherence to warfarin, and the following month she developed DVTs of the left common femoral and iliac veins necessitating thrombectomy (INR 1.7). The patient was unwilling to treat with enoxaparin long-term. Therefore, anticoagulation was changed to apixaban (10 mg twice daily × 7 days, then 5 mg twice daily) with the hope of better adherence, and ASA was held for a brief time due to hematuria (Table 1; Figure 1). Ten days later, while receiving apixaban, the patient developed recurrent left common femoral, iliac, and popliteal DVTs, requiring additional catheter-directed thrombolysis and angioplasty of left common iliac and femoral veins with common iliac stent vein placement, with evidence of May-Thurner syndrome. Following this fourth episode of thrombosis in 6 months, she was maintained on low dose ASA and apixaban with the initiation of 4 weekly doses of rituximab, despite which APA titers remained profoundly elevated (Table 1).

Figure 1.

Clinical event and treatment timeline.

Fourteen months later, she developed recurrent nonocclusive left common femoral, femoral, and greater saphenous DVT, and apixaban was increased for 1 week (5 mg twice daily to 10 mg twice daily). One month later, she developed acute occlusive thrombus in the left common femoral vein extending into the iliac and patellar veins concerning for stent narrowing and occlusion, requiring iliac venoplasty and thrombolysis. With recurrent thrombosis refractory to rituximab, hydroxychloroquine (200 mg daily) and clopidogrel (75 mg daily) were added to the anticoagulation regimen.9 Approximately 40 days later, she again developed a new thrombus in the left external iliac, common femoral, femoral, popliteal, tibial, and peroneal trunk veins, leading to repeat thrombolysis and stenting of the left common femoral to external iliac veins. Anticoagulation was changed to therapeutic enoxaparin with patient shared decision-making, then transitioned to fondaparinux for long-term therapy to avoid potential osteopenia, with continuation of dual antiplatelet therapy and hydroxychloroquine increased to twice daily (Table 1; Figure 1). Each new thrombotic event was associated with new symptoms and evidence of acute thrombus extension on repeated imaging.

One year later, she presented with right upper quadrant abdominal pain. Computed tomography of the abdomen showed an acute segmental hepatic infarction of the left medial hepatic lobe with concomitant significant elevation of APA titers (Table 1). Laboratory studies at the time of hepatic infarct revealed: white blood cells, 10.68 K/mcL; hemoglobin, 8.1 g/dL; platelets, 84 K/mcL; activated partial thromboplastin clotting time, 59 seconds; INR, 1.4; creatinine, 0.72 mg/dL; aspartate aminotransferase, 146 U/L; alanine aminotransferase, 134 U/L; total bilirubin, 0.9 mg/dL. This presentation raised concern for possible catastrophic antiphospholipid syndrome (CAPS),10 a rare, potentially life-threatening form of APS with thrombotic microangiopathy and multiorgan thromboses.11 Plasma exchange was initiated with a goal of 50% to 75% titer reduction. Methylprednisolone (1000 mg) was initiated as she underwent 6 sessions of plasma exchange, despite which APA titers remained elevated (Table 1). IV immune globulin was not used due to concerns for thrombosis risk.12,13 Therapeutic anticoagulation was transitioned to fondaparinux, prednisone (60 mg daily), aspirin, clopidogrel, and hydroxychloroquine.

Over the next 6 weeks, corticosteroids were tapered. Two months later, she developed an extension of the inferior right hepatic lobe infarction, secondary to thrombosis of the right portal vein. Despite multimodal therapy, recurrent thrombosis persisted with elevated APA titers. Therefore, eculizumab (600 mg weekly × 4 weeks, followed by 900 mg once on week 5, followed by 900 mg every 2 weeks) was initiated in addition to antiplatelet and anticoagulation therapies.6,11,14-17 The patient received the meningococcal vaccine prior to eculizumab initiation. During the initiation of weekly loading doses of eculizumab, she developed left lower lobe segmental and subsegmental pulmonary emboli without right heart strain. She did not require supplemental oxygen therapy, and current drug therapies were continued, including loading and subsequent maintenance doses of eculizumab. As of the time of this writing, she continues to receive fondaparinux, aspirin, clopidogrel, hydroxychloroquine, and eculizumab 900 mg IV every 2 weeks since October 2019 without recurrent thrombosis. Subsequently, she underwent sequencing for complement regulatory gene mutations (on a panel including CFH, CI, MCP, C3, CFB, CFD, CFHR1, CFHR2, CFHR3, CFHR4, CFHR5, CFP, and THBD) and did not have pathogenic germline variants.

Methods

This report was a retrospective chart review of 1 patient with APS and refractory thrombosis. The patient provided consent for review of medical records and publication of results per the Declaration of Helsinki. The University of Illinois College of Medicine Institutional Review Board approved the study.

Results and discussion

APA contributes to thrombosis via multiple mechanisms, including platelet and coagulation cascade activation, some of which involve complement.18 Increased C3, C5a, and TCC may activate platelets and endothelium with direct histologic evidence of anti–β-2 GP1 IgG–C5b-9 immune complexes in microvascular organ thrombi.11,14 Further, complement activates anaphylactic peptides and cytolytic compounds, stimulating proinflammatory mediators.18 Complement deposition in infarcted tissue, and resistance of complement-deficient animal models to APA-associated thrombosis, reinforce the potential benefit of complement inhibition. Additionally, eculizumab is used in atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome and paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria.11,15-17,19,20 Though our patient did not meet strict criteria for CAPS, complement involvement in thrombosis prompted the use of eculizumab in addition to anticoagulation and antiplatelet therapies.

Eculizumab preventing TCC formation may have a role in refractory thrombosis in APS when other therapies fail and was chosen as empirical treatment in this case of potentially life-threatening recurrent thrombosis. In this case, eculizumab appeared to contribute to successful thrombosis prevention along with anticoagulation and antiplatelet therapy. Complement may also be implicated through rare germline mutations in complement regulatory genes5; however, no specific complement pathway mutation was determined in this case. As the role of complement in thrombosis continues to be elucidated, a multifaceted therapeutic approach should be considered. Eculizumab may have a role as a therapeutic option in refractory thrombosis in APS.

Acknowledgment

The authors would like to thank the clinical care team at the Bleeding & Clotting Disorders Institute for their excellence in the continued management of this patient.

The Hemostasis and Thrombosis Research Society, Inc. (HTRS) provided support from its Publication Fund for Early-stage Investigators to offset the cost of publication. Dr. Hussain received this support as part of an Abstract Award from the HTRS 2021 Scientific Symposium.

Authorship

Contribution: H.H. and J.C.R. analyzed the data and wrote the initial draft of the manuscript; S.C. performed complement regulatory gene testing; H.H., M.D.T., S.C., K.R.M., and J.C.R. reviewed, edited, and approved the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Jonathan C. Roberts, Bleeding & Clotting Disorders Institute, 427 W. Northmoor Rd, Peoria, IL 61614; e-mail: jroberts@ilbcdi.org.

References

- 1.Miyakis S, Lockshin MD, Atsumi T, et al. International consensus statement on an update of the classification criteria for definite antiphospholipid syndrome (APS). J Thromb Haemost. 2006;4(2):295-306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aguiar CL, Erkan D. Catastrophic antiphospholipid syndrome: how to diagnose a rare but highly fatal disease. Ther Adv Musculoskelet Dis. 2013;5(6):305-314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Duarte-García A, Pham MM, Crowson CS, et al. The epidemiology of antiphospholipid syndrome: a population-based study [published correction appears in Arthritis Rheumatol 2020;72(4):597]. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2019;71(9):1545-1552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chaturvedi S, Brodsky RA, McCrae KR. Complement in the pathophysiology of the antiphospholipid syndrome. Front Immunol. 2019;10:449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chaturvedi S, Braunstein EM, Yuan X, et al. Complement activity and complement regulatory gene mutations are associated with thrombosis in APS and CAPS. Blood. 2020;135(4):239-251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kronbichler A, Frank R, Kirschfink M, et al. Efficacy of eculizumab in a patient with immunoadsorption-dependent catastrophic antiphospholipid syndrome: a case report. Medicine (Baltimore). 2014;93(26):e143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rovere-Querini P, Canti V, Erra R, et al. Eculizumab in a pregnant patient with laboratory onset of catastrophic antiphospholipid syndrome: a case report. Medicine (Baltimore). 2018;97(40):e12584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Meroni PL, Macor P, Durigutto P, et al. Complement activation in antiphospholipid syndrome and its inhibition to prevent rethrombosis after arterial surgery. Blood. 2016;127(3):365-367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Arachchillage DRJ, Laffan M. Pathogenesis and management of antiphospholipid syndrome. Br J Haematol. 2017;178(2):181-195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Asherson RA, Cervera R, de Groot PG, et al. ; Catastrophic Antiphospholipid Syndrome Registry Project Group . Catastrophic antiphospholipid syndrome: international consensus statement on classification criteria and treatment guidelines. Lupus. 2003;12(7):530-534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tinti MG, Carnevale V, Inglese M, et al. Eculizumab in refractory catastrophic antiphospholipid syndrome: a case report and systematic review of the literature. Clin Exp Med. 2019;19(3):281-288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Marie I, Maurey G, Hervé F, Hellot MF, Levesque H. Intravenous immunoglobulin-associated arterial and venous thrombosis; report of a series and review of the literature. Br J Dermatol. 2006;155(4):714-721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Guo Y, Tian X, Wang X, Xiao Z. Adverse effects of immunoglobulin therapy. Front Immunol. 2018;9:1299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ruffatti A, Tarzia V, Fedrigo M, et al. Evidence of complement activation in the thrombotic small vessels of a patient with catastrophic antiphospholipid syndrome treated with eculizumab. Autoimmun Rev. 2019;18(5):561-563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shapira I, Andrade D, Allen SL, Salmon JE. Brief report: induction of sustained remission in recurrent catastrophic antiphospholipid syndrome via inhibition of terminal complement with eculizumab. Arthritis Rheum. 2012;64(8):2719-2723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Strakhan M, Hurtado-Sbordoni M, Galeas N, Bakirhan K, Alexis K, Elrafei T. 36-year-old female with catastrophic antiphospholipid syndrome treated with eculizumab: a case report and review of literature. Case Rep Hematol. 2014;2014:704371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Guillot M, Rafat C, Buob D, et al. Eculizumab for catastrophic antiphospholipid syndrome-a case report and literature review. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2018;57(11):2055-2057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Luo S, Hu D, Wang M, Zipfel PF, Hu Y. Complement in hemolysis- and thrombosis- related diseases. Front Immunol. 2020;11:1212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pierangeli SS, Girardi G, Vega-Ostertag M, Liu X, Espinola RG, Salmon J. Requirement of activation of complement C3 and C5 for antiphospholipid antibody-mediated thrombophilia. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;52(7):2120-2124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shamonki JM, Salmon JE, Hyjek E, Baergen RN. Excessive complement activation is associated with placental injury in patients with antiphospholipid antibodies. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2007;196(2):167.e1-167.e5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]