Abstract

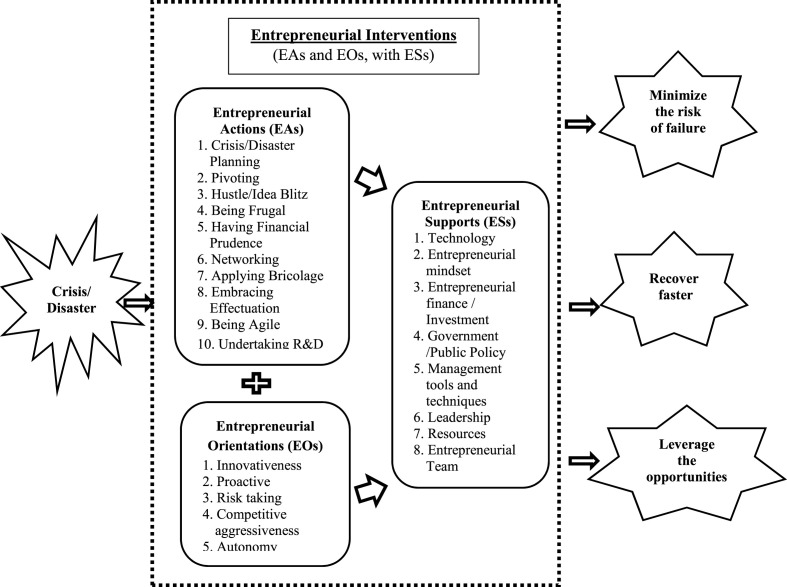

This article investigates both the negative and positive impacts of a crisis on Entrepreneurial Ventures. The behaviour of Entrepreneurial Ventures during the COVID-19 pandemic crisis is studied by undertaking a Systematic Literature Review (SLR) using Bibliometrics of 154 related publications. After analyzing the literature, the behaviour of Entrepreneurial Ventures during the crisis is synthesized and presented as a Phenomenon Structure Diagram, which highlights a combination of Entrepreneurial Actions (EAs) and Entrepreneurial Orientations (EOs), with Entrepreneurial Supports (ESs) employed by them to manage the crisis. This combination of EAs and EOs with ESs is contingent on the surrounding environment, and they aid in minimizing the risk of failure as well as leverage new opportunities. We propose and develop a conceptual model that a combination of EAs and EOs with ESs, referred to as Entrepreneurial Interventions, can better manage a crisis or disaster and improve organizational resilience. This multi-disciplinary study contributes towards theory development that Entrepreneurial Interventions can be made as a crisis and disaster management strategy.

Keywords: Small business and SME, Systematic Literature Review, Bibliometric Analysis, Crisis/Disaster Management, Resilience, Risk of failure

1. Introduction

Managing a crisis or disaster in organizations and businesses is an emerging research area [32,39,40,60,83,98,165,167,199,202]. Crisis management is primarily considered as a response to adversity to bring back the disrupted system into alignment [13,57,85,91,98,145,199,202]. There is an overlap between crisis management and resilience since resilience deals with the ability of an organization to get back to its original state and maintain reliable functioning despite adversity [32,39,40,60,83,98,165,167,199,202]. Recent studies on organizational resilience highlight the following (a) resilience is beyond restoration and includes the development of new capabilities and an expanded ability to keep pace with and create new opportunities [177], (b) resilience is an ability to develop ‘proactive’ and ‘reactive’ capabilities [39,47,60] to increase the level of readiness to respond to disruption during the various stages of crisis such as pre-crisis, during-crisis, and post-crisis [91], (c) resilience is founded on four major pillars: preparedness, responsiveness, adaptability and learning [40], (d) resilience consists of two dimensions, namely ‘planned’ and ‘adaptive’ resilience [32,167,184], (e) ‘absorptive’ and ‘adaptive’ resilience can be considered as two paths for organizational resilience, and (f) dynamic capabilities are known to manage crises, disruptions, and unexpected events, and maximize the organizations' recovery speed, which is known as dynamic resilience [27]. The above studies and findings are significant from the perspective of crisis management and resilience (proactive, adaptive, and dynamic resilience). We propose to additionally contribute to this subject, in this paper. We intend to study the combined influence of negative and positive impacts, namely risk of failure and leveraging opportunities arising from a crisis, and how some crisis management strategies can enhance an organization's proactive/adaptive/dynamic resilience.

Several crises and disasters have impacted organizations, such as the global financial crisis, natural disasters such as floods and cyclones, geopolitical threats, and the most recent one due to the COVID-19 pandemic, and scholars have studied ways to manage them [1,14,32,57,71,83,85,91,110,146,167,181,183,199,200]. In this paper, we propose to primarily focus on the COVID-19 pandemic crisis, which started in late 2019, and the consequential lockdowns that resulted in an unforeseen and sudden adverse impact on the global economy [52,66,83,132]. The COVID-19 pandemic can be classified as a crisis and disaster since Faulkner [67] states that disasters are sudden with unpredictable catastrophic changes over which the victims had minimum control. However, the lockdowns that followed were an unexpected problem that originated in planning and management deficiencies of organizations, society, and countries. Since these causes are man-made, they can also be considered as a crisis. Faulkner [67] distinguished between crisis and disaster based on the origin/root cause of the event. In this article, since the focus is on the outcomes/effects of the pandemic and not on its causes, our findings would be equally applicable for both crisis and disaster management. Other authors have also followed such an approach while developing their frameworks for managing crises and disasters [67,91,144].

Considering the existing literature in crisis/disaster management and organizational resilience and viewing crises as having both negative and positive impacts, we propose to study how the COVID-19 pandemic crisis has impacted organizations both negatively (risk of failure) and positively (leveraging opportunities). It would be best to study Entrepreneurial Ventures (EVs) from an opportunity angle since they are known to creatively pursue and realize opportunities [31,56,80,176,199]. At the same juncture, EVs are also known to have a very high failure rate [22,30,45,66,113,178]. Thus, studying EVs' behaviour during a crisis would be appropriate; Annarelli and Nonino (2016) [27] highlighted the need to study SMEs’ resilience. The book by Shepherd and Patzelt (2017) [187] also brings out the need to undertake specific studies on EVs related to their failure and resilience. Similarly, Williams et al. (2017) [199] found that entrepreneurial experience will help in influencing resilience. Thus, in this study, we focus on EVs to understand their behaviour during the COVID-19 pandemic crisis. There are different types of EVs, and Morris et al. [133: Table 1 , p. [162], identified four broad venture types and among them listed the following as EVs, which include Small business, Small family business, Marginal enterprise, Lifestyle enterprise, High-growth start-up, Tech start-ups, and Innovative start-ups. We add Micro, Small, and Medium Enterprises (MSMEs) and SMEs to this list of EVs since they are similar to Small businesses [52,104,106]. Interestingly, EVs have presented divergent behaviours during crises. These firms have shown high failure rates [22,30,45,66,113,178]. At the same juncture, they are also known to recover from disasters and crises [1,57,67,91] due to their (a) entrepreneurial orientation1 (EO) [106], (b) ability to take quick entrepreneurial action2 (EA) [74,101,106], (c) resilience [127,172] character of being agile [101], flexibility [63,91,127], pivoting capability [132,179], and (d) resilient business models [57,110,113] to leverage market opportunities [63,172]. Studying the behaviour of EVs during the COVID-19 pandemic would thus help understand both negative and positive impacts encountered by a venture during a crisis. Management scholars could be interested to know if patterns can be identified through research on EVs during the COVID-19 crisis and whether any actionable knowledge for effective governance during crisis [202] can be developed from such patterns. Therefore, in this study, we attempt to understand the behaviour pattern of EVs through a sequencing-based approach, as proposed by Buchanan and Denyer (2013) [206] for crisis management.

Table 1.

Locating the study with inclusion and exclusion criteria.

| Inclusion criteria | |

| Search String | (*COVID* OR Pandemic OR *Corona* OR SARS OR Lockdown) AND (Entrepreneur* OR {SME*} OR {MSME*} OR Start*up* OR Spin*off* OR Silicon Valley * OR High*Tech* OR NTBF* OR Small busines* OR Family busines* OR Life*style busines* OR Marginal* OR unorganized sector*) |

| Search period | From: not specified (open-ended) To: 18 Oct 2020 |

| Search location | Title, Abstract, Keywords |

| Type of Document | Article, Conference article, Editorial, Business case studies, book chapters |

| Database used | Scopus and Web of Science (WoS) |

| Merging Database | 427 (331 documents from Scopus and 96 from WoS) 94 WoS documents were found in the Scopus database also. 331 Scopus +2 from WoS = 333 document |

| Exclusion criteria | |

| Duplicates | 34 documents: Balance = 299 document |

| Non-English documents | 14 documents: Balance = 285 document Documents in Chinese, Russian, Spanish, German, Portuguese, and Italian were removed |

| Irrelevant documents | 131 documents, after reading their abstract.

|

The research problem that we aim to address concerns the behaviour of EVs during the COVID-19 pandemic crisis. We investigate the negative and positive impacts of the crisis, to formulate some crisis management strategies. We further briefly investigate if EVs' behaviour could apply to large organizations to enhance their resilience. Systematic Literature Review (SLR) using Bibliometrics is undertaken here, as this is the most appropriate method (see Section-2) to address the above research problem. Several similar studies [27,50,196] have employed SLR using bibliometrics as the research method. The contributions of this multi-disciplinary study are consolidatory in nature with an attempt towards theory development. The first contribution is in understanding EVs’ behaviours during the pandemic and presenting a diagrammatic representation through a Phenomenon Structure Diagram (PSD) (see Fig. 6, Fig. 7). The second contribution is in identifying that EVs employ a combination of Entrepreneurial Actions (EAs) and Entrepreneurial Orientations (EOs) with Entrepreneurial Supports (ESs) to overcome the COVID-19 pandemic crisis. We denote this combination of EAs and Eos with ESs as Entrepreneurial Interventions (EIvs). The third contribution is developing a conceptual model (see Fig. 7) highlighting the applicability of EIvs as a crisis management strategy and the suggestion that this strategy is contingent on the surrounding environment. In addition, this study has tabulated the current status of COVID-19 research for each type of EVs across the various research topics, sectors, and countries of research (see Table C-1, C-2, C-3 in Appendix C). The table highlights the research gaps that academicians can further investigate and convert into research opportunities.

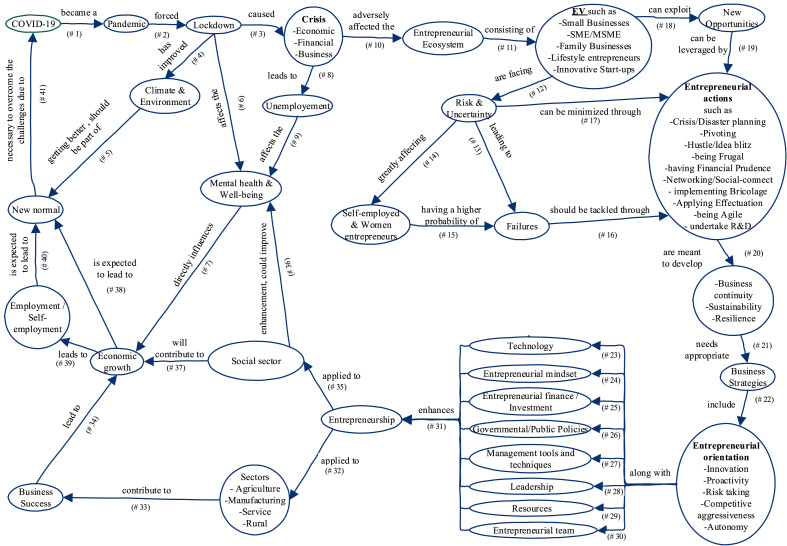

Fig. 6.

Phenomenon Structure Diagram (PSD) showing the impact of COVID-19 on Entrepreneurial Ventures (EV).

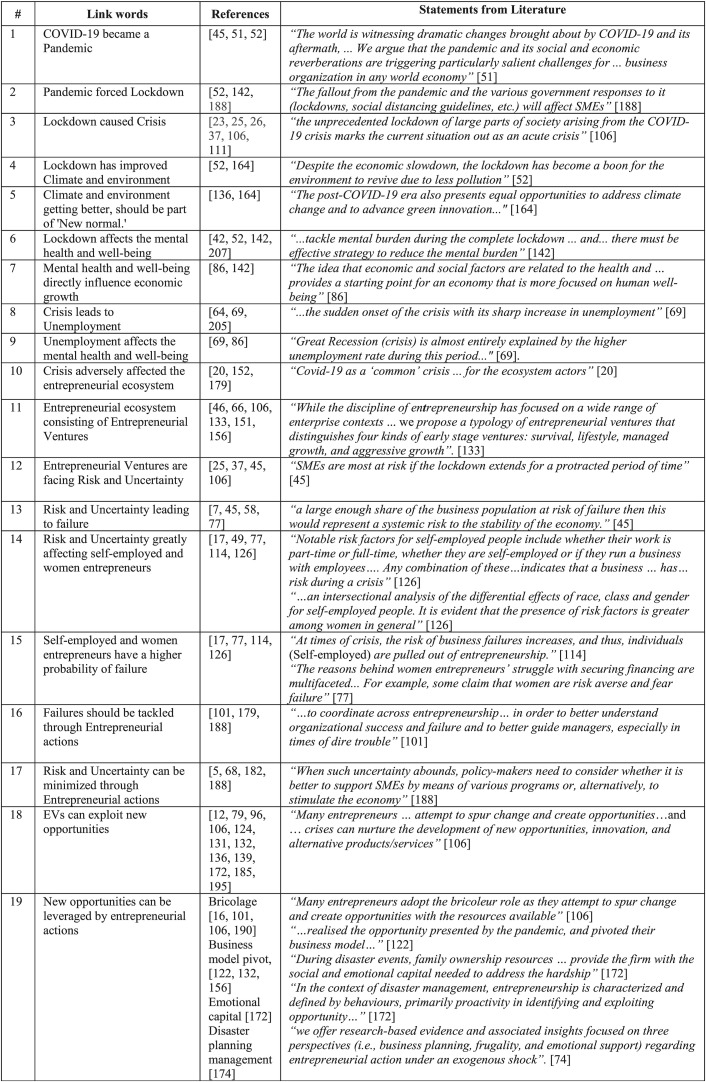

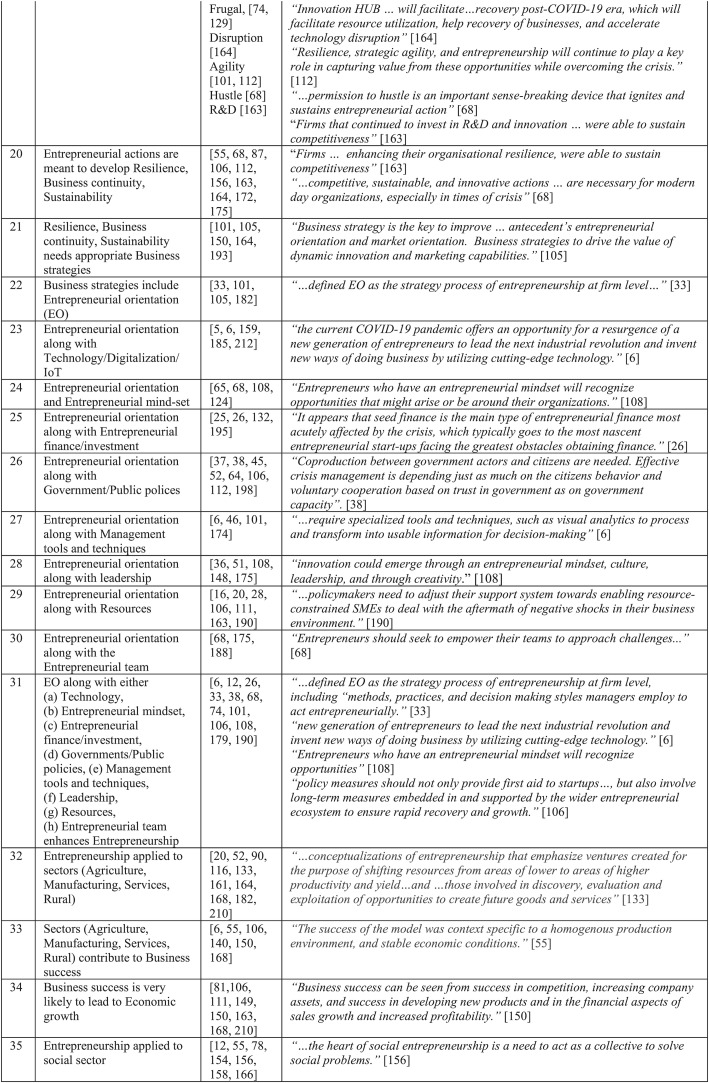

Fig. 7.

Phenomenon Structure Diagram (PSD) references to the link between the structural entities showing the impact of COVID-19 on Entrepreneurial Ventures (EV).

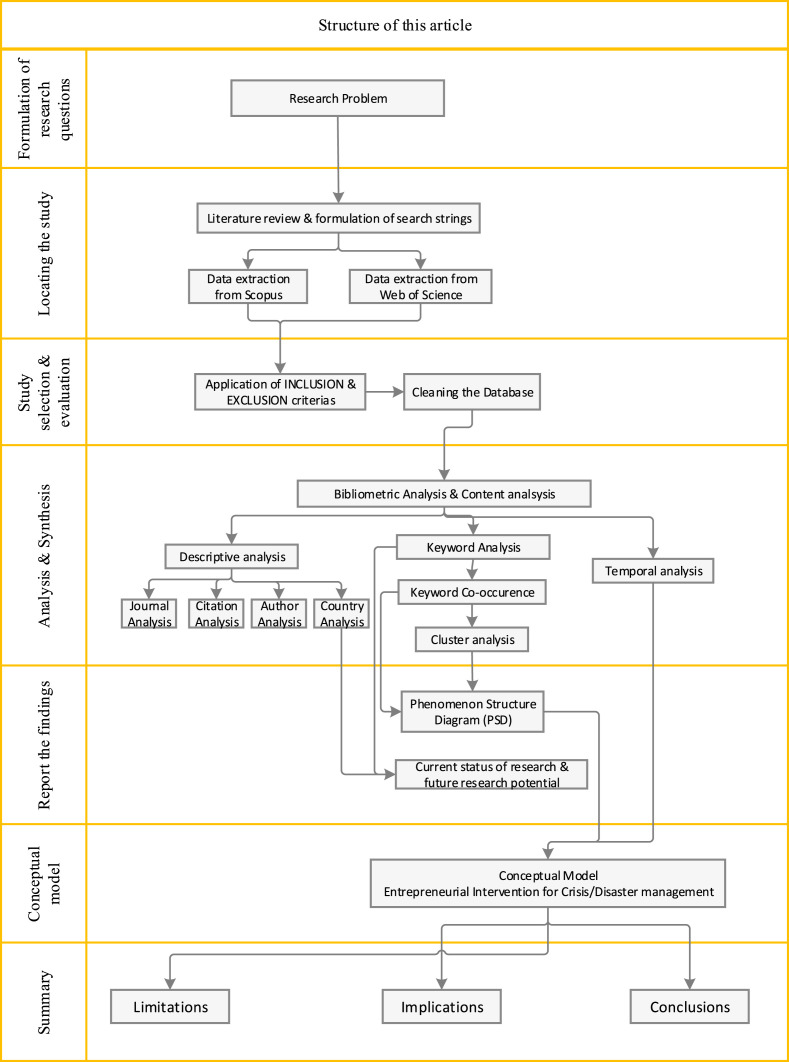

This article is structured as follows: The method used to systematically study the literature is presented. Then, the behaviour of EVs during a crisis is consolidated and presented as a theoretical proposition. Finally, a conceptual model on Entrepreneurial intervention for crisis management is elaborated. The structure of this article is presented in Fig. 1 .

Fig. 1.

Structure of the article along with the research method employed.

2. Research methods and tools used

We have performed an SLR using Bibliometrics of the relevant extant literature. Since the COVID-19 pandemic impacted the whole world, we wanted to study the behaviour of EVs in all possible countries. To do this, we opined that an SLR would be a quick and appropriate research method since an SLR can consolidate literature from different countries. Undertaking SLR is the best approach for this research since it comprehensively combines information, engendering new ideas/framework/models, and provides new research directions [189] in a transparent and reproducible manner [54]. SLR has been used to study similar subjects in the recent past, such as the dynamic perspective on the resilience of firms [213], and linking resilience and entrepreneurship [214]. As Tranfield et al. [189] proposed, we have employed SLR, and it's five stages as listed vertically in Fig. 1. For the fourth stage of ‘analysis and synthesis’, we have used Bibliometrics (‘co-occurrence’ and ‘bibliographic coupling’) to group and form clusters that will enable a systematic understanding of the publications on the subject. Bibliometrics is a popular statistical quantitative research tool to study existing publications and examine the evolution of research domains; it can be used to study the intellectual/conceptual structure of the research topic [43]. Such a combination of SLR and Bibliometrics has been used in recent publications in business and management to study SMEs' risks [50], study the organization resilience [27], and the impact of COVID-19 in business and management [196].

For undertaking Bibliometrics, we used VOSviewer, an open-source software. VOSviewer is compatible with Scopus and Web of Science (WoS) bibliometric databases. Recent publications [35,196] have used VOSviewer for Bibliometrics.

3. Consolidation of publications on pandemics and entrepreneurial ventures

3.1. Locating the study

Scopus and WoS were used for locating literature to build a database of relevant documents on COVID-19 and EVs. Castriotta et al. (2019) [35] have recommended using more than one database to include a greater variety of journals. As we wanted to study the impact of the COVID-19 and the pandemic on EVs, we formulated search strings based on keywords identified in previous SLR/Bibliometrics-based research. For articles related to COVID-19, we referred to Verma and Gustafsson [196], which guided us to use the following keywords, viz., COVID-19, Pandemic, Coronavirus, SARS virus, and Lockdown. Similarly, the articles on EVs [133] and emerging organizations [35] led to the following search string words: Entrepreneurship, Entrepreneur, Start-up, Spin-off, Silicon Valley enterprise/firm, High-Tech firm, New Technology-based firm (NTBF), SME, MSME, Small business, Family business, Lifestyle business, Marginal business, and Unorganized sector. These keywords were reviewed with two experts and finalized after three rounds of iterations for downloading journal citations and reviewing them. Using a combination of search strings (refer to Table 1), the citation details of documents were searched and downloaded from Scopus and WoS. This search process did not specify any start date since we wanted to capture the past research on the pandemic before COVID-19. The end date was the search date (18 Oct 20) of downloading the bibliographic data.

3.2. Study selection and evaluation

The search resulted in a total of 427 documents (331 from Scopus and 96 from WoS). The inclusion criteria used for the identification of appropriate documents are tabulated in Table 1. The databases’ results were superimposed on each other using DOI numbers, and 94 documents from WoS were available in the Scopus database. The two WoS documents not in the Scopus database were added to the latter so that the Scopus database could be used as the master database. Exclusion criteria were applied to this master database containing 333 documents. This resulted in 154 documents, as detailed in Table 1.

These 154 documents were cleaned for uniformity. The correctness of the journal name, author name, and document title was checked and amended. The author keywords were studied and cleaned by performing the following: (a) converting plural to singular, (b) uniformity in hyphenation, (c) various authors have used different keywords to mean a single or similar idea/concept. For example, COVID-19 and Coronavirus convey similar ideas (in the context of this article). Such keywords were identified and replaced with one common keyword, and (d) author keywords were not listed in14 documents. Index keywords were used as surrogates of authors' keywords for nine, and for the remaining five documents, keywords were assigned from those used in the other 149 documents. The above cleaning of keywords was done by the first author and then rechecked by the second author to improve results' correctness [35].

4. Analysis and synthesis of pandemic literature on entrepreneurial ventures

The shortlisted 154 articles were subjected to three types of analysis and synthesis, which are (1) Descriptive analysis, (2) Keyword, Co-occurrence and Cluster Analysis, and (3) Temporal analysis.

4.1. Descriptive analysis

In the descriptive analysis, the following were analyzed (a) Journal analysis, (b) Citation analysis, (c) Country analysis. The details are placed in Appendix-A.

4.2. Keyword, Co-occurrence, and Cluster Analysis

4.2.1. Keyword analysis

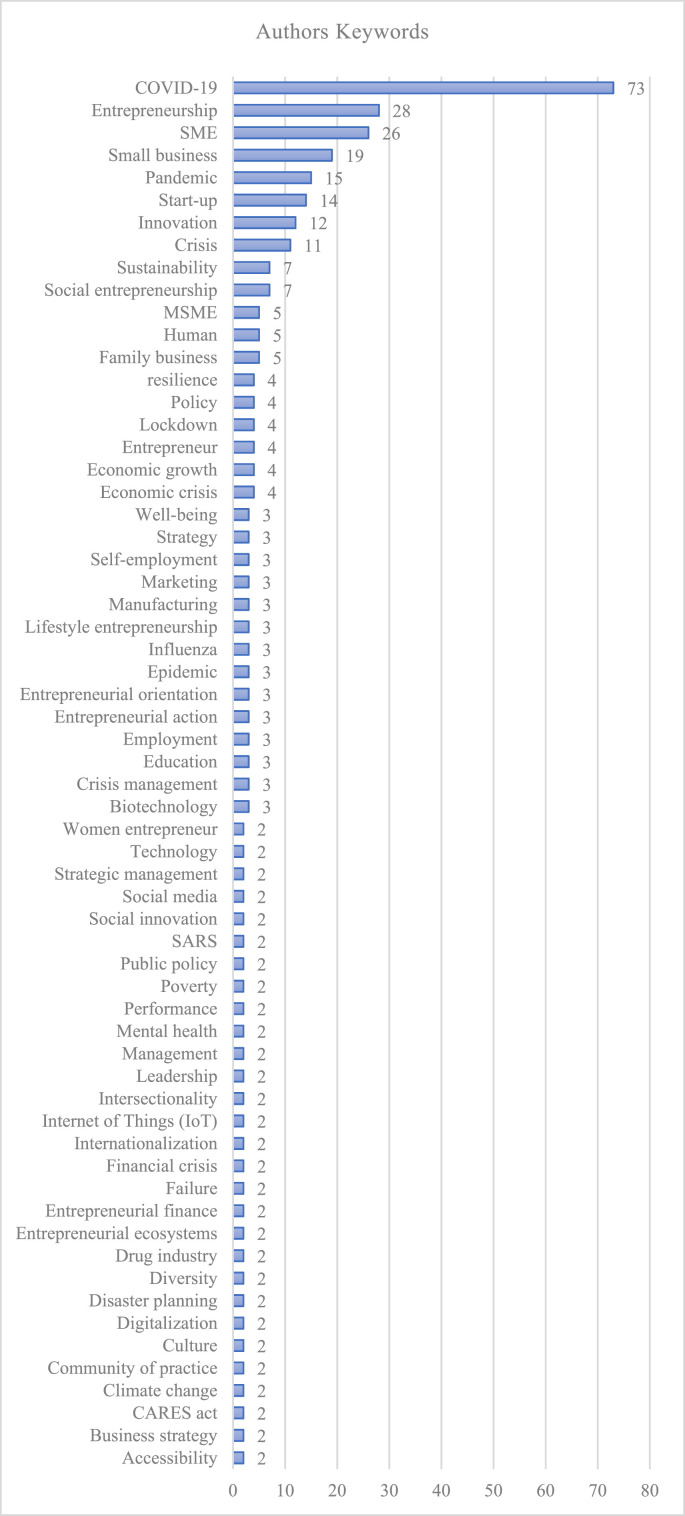

The database of 154 documents contained 577 different keywords. Their frequency of occurrence was analyzed, and 62 keywords were used in more than two documents. Fig. 2 shows these keywords and their respective frequencies.

Fig. 2.

Author keywords appearing more than once.

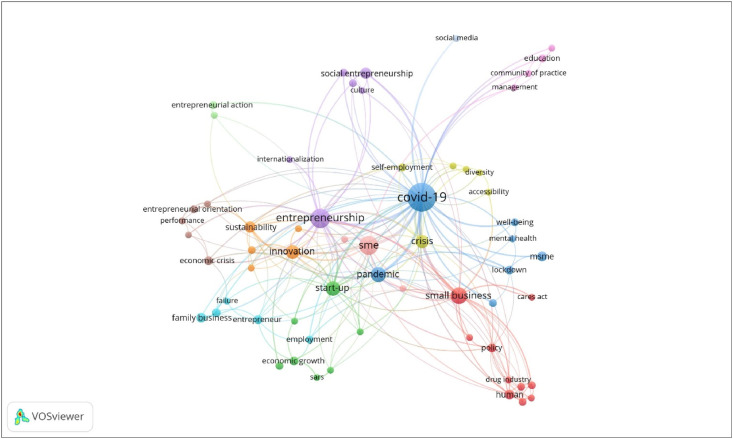

4.2.2. Keyword Co-occurrence, and cluster analysis

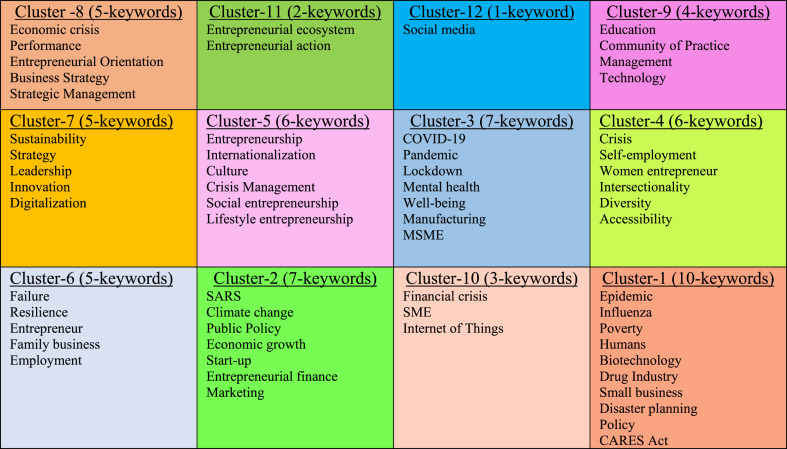

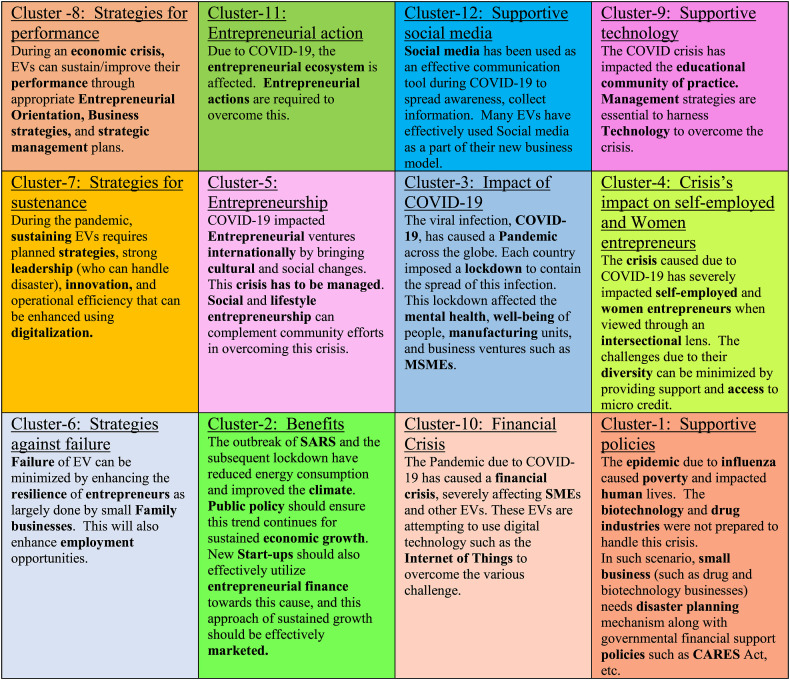

VOSviewer applies text-mining techniques for Co-occurrence [192]. The co-occurrence map of author-keywords with the threshold set as two documents is presented in Fig. 3 . The 61 keywords (as one keyword, ‘social innovation’ is not a part of the cluster) are grouped into 12 clusters during co-occurrence processes by VOSviewer. Different colours represent each cluster. All the 61 keywords in Fig. 3 are represented cluster-wise in Fig. 4 because keywords close to each other in Fig. 3 are not visible. A cluster contains keywords that can be grouped to represent concepts, as seen in the bibliometric coupling of documents in the citation analysis, where the articles are grouped into 12 clusters.

Fig. 3.

Keyword co-occurrence map of 61 keywords from 154 documents.

Fig. 4.

Cluster representation of keywords based on co-occurrence map of 61 keywords.

A study of Fig. 3 (or its representation in Fig. 4) for various types of EVs reveals that the following types of firms have been studied in the currently published literature. These are, as we move from the left towards the right extreme, (1) Family business, (2) Start-up, (3) Lifestyle entrepreneur, (4) SME, (5) Small business, and (6) MSME. We have therefore considered these six different types of EVs in our further studies. Start-ups and Innovative Start-ups have been used interchangeably [26,106]. Also, since firms such as hi-tech start-ups, university spin-offs, and innovative start-ups are grouped as Innovative Start-ups (ISs) [104], we have used Innovative Start-up (ISs) in this article to refer to the above types of Start-ups.

From each of these 12 clusters, the keywords and their corresponding articles were identified and studied. The views expressed in each article were understood. To highlight the type of analysis undertaken by us using keyword co-occurrence, we have presented views for some clusters (with the keywords marked in bold):

-

(a)

Cluster-3: This is the central cluster. There are seven keywords in this cluster. The views of authors connecting these keywords in their article are as follows. Article [142] mention that the “COVID-19 pandemic can be considered as a life-threatening war … and … it is essential to follow the lockdown protocols till the worldwide situation improves”. Similar views are expressed by Refs. [52,76]. Article [142] also highlight the need to “… tackle mental burden during the complete lockdown … and … there must be some effective strategy to reduce the mental burden”. Similar views have been indicated by other authors [76,86]. Debata et al. [52], state that the pandemic and the subsequent lockdown has resulted in “The industrial sectors – manufacturing and start-ups are temporarily closed leading to a significant revenue loss”. Article [168] state that “The impact is severe on trade, manufacturing and MSME sectors”. After reading all the relevant articles, the consolidated, integrated concept that emerges from cluster-3 is expressed in Fig. 5 .

-

(b)

Cluster-5: This cluster has six keywords. The authors' views related to these keywords are: Zahra [209] highlights that “When thinking about the global business environment and how it affects international ventures, it is clear that Covid has already brought about major changes that will profoundly impact these businesses for years to come”. Ratten [152] also states that “Coronavirus has significantly affected international business particularly in terms of free movement”. Ratten [156] highlights that the “(COVID-19) crisis brought about unintended cultural change”. Ratten [156] elaborates that “the meaning of entrepreneurship changes over time with the concept broadening to include more lifestyle , cultural and social goals”. Ratten [156] proposes that “ Social entrepreneurship is needed more in times of a crisis because of the emphasis on societal well-being” and “ Lifestyle entrepreneurship can mean lifestyle business opportunities are found that can be used to alleviate problems caused by the crisis ”. Similar views on Social, Cultural and Lifestyle entrepreneurship are expressed by Refs. [10,55,154,157,158]. The integrated concept for this cluster is presented in Fig. 5.

-

(c)

Cluster-6: The author(s) views related to the six keywords are: Shepherd [179] states that “In the aftermath of the pandemic (and response), a lot of businesses have failed , but there is little they could have done to avoid this outcome” and “… these victim entrepreneurs can eventually drop the label victim and build back a better future for themselves and enhance resilience in the process.“. Sawalha [174] states that “ resilience should further reflect an ability to take advantage of these incidents to become even stronger.” Salvato et al. [172], state that “ family firms ' superior longevity is their resilience to mass emergencies and their ability to transform post-crisis threats into entrepreneurial opportunities”. Similar views on small family business and resilience are expressed by Refs. [51,65,151]. Fossen [69] stated that “Self- employment will increase during recessions when unemployment is high …“. The integrated concept for this cluster is presented in Fig. 5.

-

(d)

Cluster-10: This cluster highlights that COVID-19 caused a financial crisis, which impacted entrepreneurial ventures such as SMEs. Brown and Rocha [25] illustrate in their article “how chronic uncertainty caused by crisis events affects the availability of entrepreneurial sources of finance for start-ups and SMEs ”. To come out of this financial crisis, Roper and Turner [163] highlight that SMEs need to focus on R&D and Innovation “The COVID-19 crisis seems likely to leave many firms financially weaker, with the most significant impacts on the willingness or ability of SMEs to sustain R&D and innovation”. In addition to R&D and Innovation, disruptive technology, such as the Internet of things, is identified by Ref. [5] by stating that “… disruptive computing technologies, data analytics, and the Internet of Things (IoT) required to engineer new business models, reduce overheads, enhance competitive advantages, and digitize SMEs' business operations”. A similar view has been expressed in the article [6]. Refer to Fig. 5 for the integrated concept.

-

(e)

Cluster-8: The focus of this cluster is on Entrepreneurial Orientation (EO) to improve performance during an economic crisis. Kuckertz et al. [106], state “The COVID-19 pandemic has placed an unprecedented burden … and … have caused an economic crisis by bringing a vast amount of economic activity to an abrupt halt” and have identified “seven factors related to adversity and coping strategies ”. Article [193] highlights that “Taking into account the environment in which an organization operates, the choice and effective implementation of appropriate strategies should instinctively lead to better performance ” and “business performance is a multi-dimensional phenomenon”. Several articles have listed different strategies to overcome the economic crisis caused by the COVID-19 pandemic [2,7,107,112,122,124,190,193]. Cannavale et al. [33], have observed that “In the low-resilient (due to external shocks) sanctioned economy, Iran, EO-performance link is moderated by the level of CEOs' (leadership) self-transcendence value” and “higher level of CEO self-transcendence leads to stronger impact of EO on performance ”. Smith et al. [182], suggest “ EO may be viewed as the entrepreneurial strategy -making processes” and similar views are expressed by Refs. [33,105]. Refer to Fig. 5 for the integrated concept.

-

(f)

Cluster-7: The focus of this cluster is on strategies for sustenance. Smith et al. [182], state that “the organisational ability to be entrepreneurially orientated, grow, adapt and be a responsible and sustainable business is affected by factors … that include …” and they also state that Entrepreneurial Orientation “EO may be viewed as the entrepreneurial strategy -making processes that key decision-makers use to enact their firm's organisational purpose, sustain its vision and create competitive advantage”. Ketchen and Craighead [101] highlight the need to “build knowledge about how to coordinate across entrepreneurship, supply chain management, and strategic management in order to better understand organizational success and failure and to better guide managers, especially in times of dire trouble”. Similar views are expressed by Ref. [115]. Sawalha [174] states that “A number of contemporary disaster management studies started stressing the value of leadership and emphasize the need for leaders who possess innovative insight and entrepreneurial skills needed to mitigate disasters”. Zahra [209] states that “The changes prompted by Covid are likely to fuel innovation worldwide as a means of finding solutions to the problems entrepreneurs encounter. Digital technology is likely to expedite this trend” and “ digital technology has offered innovative solutions”. Soto-Acosta [185] states that “companies can apply digital technologies to accelerate business processes, eliminate inefficiencies, and/or reduce costs or even to sell more”. Refer to Fig. 5 for the integrated concept.

-

(g)

Cluster-11: The focus of this cluster is the Entrepreneurial ecosystem and Entrepreneurial action. Ratten [152] states that “the pandemic has impacted various entities of the (entrepreneurial) ecosystem …“. Kuckertz et al. [106], highlight that “some businesspeople in the entrepreneurial ecosystem already perceive entrepreneurial opportunity in a positive sense, that is, they see an opportunity to address current issues by employing entrepreneurial measures”. Giones et al. [74], state that “ Entrepreneurial action must be situated in the entrepreneurs' assessment of the opportunities and environment where they operate” and they “… offer research-based evidence and associated insights focused on three perspectives (i.e., business planning, frugality, and emotional support) regarding entrepreneurial action under an exogenous shock”. Similar views are expressed by Shepherd [179], who states that “victims (affected entrepreneurs) of adversity engage in entrepreneurial actions that help themselves”. Fisher et al. [68] also states that “ Entrepreneurial action must be situated in the entrepreneurs' assessment of the opportunities and environment where they operate.“. Viewing it from a country perspective, Kuckertz et al. [106], state that “countries that have established resilient entrepreneurial ecosystems will be able to resume their pre-crisis level of activity more quickly than those that have not”. Refer to Fig. 5 for the integrated concept.

-

(h)

Cluster-9: The integrated concept from this cluster is, supporting technologies and management skills help in overcoming the crisis. Ratten [155] states that “Covid-19 (coronavirus) has significantly affected education communities particularly in terms of the massive shift towards online learning. This has meant a quick transformation of the curriculum and learning styles to a digital platform”. Adoption of technology is essential during a crisis, as highlighted by Akpan et al. [6], “The strategies to survive the ‘new normal’ imposed by COVID-19 and fierce global competition includes a successful adoption of advanced technologies ”. Management skills are also essential for survival amidst the crisis, as highlighted by Akpan et al. [5], “… decision-analytic framework for innovative marketing, management , and financial planning … are required … to avoid small business failure”. Refer to Fig. 5 for the integrated concept.

-

(i)

Cluster-12: The importance of social media, information and communication technology (ICT) for business communities during the COVID crisis is highlighted in this cluster. Saleh [171] states that “ICTs and social media help these businesses to increase their overall performance and spread the business in different markets”.

Fig. 5.

Keywords cluster with a brief description of integrated concepts.

The condensed integrated concepts for all the 12 clusters are presented in Fig. 5. This has evolved after analyzing and synthesizing multiple authors’ views. These integrated concepts developed using bibliometrics form the backbone towards understanding the behaviour of Entrepreneurial ventures during a crisis. This is used in developing the PSD in the subsequent section.

4.3. Temporal analysis

Temporal analysis is performed to understand the evolution of a subject over a period of time [35]. Temporal analysis of the 154 documents reveals that 21 documents have been published before the onset of COVID-19. The details of the Temporal analysis are placed in Appendix-B. Interestingly, even before the advent of COVID-19, researchers have published articles highlighting the possible effect that pandemics could have on small businesses. The pre-COVID-19 era publications indicate (a) A pandemic can cause the failure of entrepreneurial ventures [93,118,197], (b) Entrepreneurship has been identified as one strategy to reduce the unemployment crisis [120], (c) Entrepreneurship and social entrepreneurship have been identified as a saviour of lives while investigating the Ebola pandemic crisis-ridden communities [119], and (d) Both entrepreneurship and social entrepreneurship talk about proactivity, innovation, risk management, seeking and recognizing opportunities [119].

5. Impact of the pandemic on entrepreneurial ventures: reporting the findings

The outcomes of the literature analysis are reported in the subsequent two sub-sections.

5.1. Research status and gaps in the literature related to COVID-19 and entrepreneurial ventures (EVs)

The current status of research for each type of EVs is consolidated using Bibliometrics and represented in Appendix-C. The non-availability of research articles indicates a gap, and 295 gaps are identified. These gaps need further investigation [138] to establish research opportunities.

5.2. Diagrammatic representation of COVID-19's impact on EVs

The integrated concepts, elaborated in Fig. 5, are used in understanding the behavioural pattern of EVs during the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic. This understanding has been translated into a Phenomenon Structure Diagram (PSD) presented in Fig. 6. This PSD provides a comprehensive graphical representation of the current status of research on the COVID-19 pandemic and its impact on EVs. It reveals the phenomenon's conceptual structure in terms of the relationships among the entities related to the pandemic. The PSD has been developed after reviewing all the SLR articles and integrating the various concepts/ideas presented in them. The keywords used in the co-occurrence map (Fig. 4) have been used as the conceptual entities in the PSD. Each entity is represented within a circle in Fig. 6. The link between these entities is parsimoniously indicated by short statements adjacent to the arrow connecting them. Fig. 6 should be read from one entity to its neighbouring entity, in the direction of the arrow along with the link word(s) marked adjacent to the arrow connecting the two entities. For example, in the top left corner, there are two entities, ‘COVID-19’ and ‘Pandemic’; this should be read as ‘COVID-19 became a pandemic’. The literary references corresponding to each link are marked as # with a number. This #number is linked with corresponding references in Fig. 7(a). For example, the #1 below the arrow refers to select important references, which are [45,51,52]. Relevant statements from these reference(s) are listed in the last column in Fig. 7(a). Such a PSD representation is a first attempt to portray the COVID-19 phenomenon and its impact on EVs graphically and presents the story sequentially as abstracted from the 154 articles in the database.

This PSD highlights the influences of the COVID-19 pandemic on EVs, based on various researchers' findings and views on this subject. The comprehensive understanding from this PSD presented in simple sentences is:

“COVID-19 became a pandemic. The pandemic forced national lockdowns that affect the human populations’ mental health and well-being. The lockdown also reduced environmental pollution and helped to improve the climate. It also resulted in a crisis (Economic, Financial, and Business) affecting the entrepreneurial ecosystem, encompassing EVs that faced risk and uncertainty that could lead to their failure. The self-employed and women entrepreneurs were subjected to higher risks and uncertainty, leading to a higher probability of failure. In the same situation, some EVs attempted to capitalize on the new opportunities created by COVID-19. EVs that are likely to fail, and those which are seeing opportunities in this crisis, can employ appropriate entrepreneurial actions (EA), such as crisis/disaster planning, business model pivoting, Hustle/Idea blitz, being frugal, having financial prudence, networking, and social connecting, bricolage, effectuation, being agile, and undertaking R&D. Entrepreneurial actions (EA) are required to develop business continuity, sustainability, and resilience. Business strategies at the firm-level are known as entrepreneurial orientation (EO), whose components are Innovativeness, Proactiveness, Risk-taking, Competitive aggressiveness, and Autonomy. The EO supported with (a) Technology, (b) Digitalization/IoT, (c) Entrepreneurial mindset, (d) Finance and Investment, (e) Government policies, (f) Management tools, (g) Leadership, (h) Resources, and (i) Entrepreneurial team, will enhance entrepreneurship. Entrepreneurship, when practiced in various sectors such as agriculture, manufacturing, and services in urban/rural areas, could lead to business success contributing to economic growth. In the social sector, entrepreneurship could improve the well-being of people, further accelerating the national economy. A spur in economic growth will increase employment/self-employment opportunities and lead to a new normal that will help transcend the challenges posed by the COVID-19 pandemic.”

The PSD presented in Fig. 6 is entirely supported by published literature on COVID-19, which is tabulated in Fig. 7(a).

6. Discussion: entrepreneurial intervention (EIv) for crisis management

From this PSD, the entrepreneurial behaviour of EVs during the COVID-19 pandemic can be understood. Entrepreneurial behaviour refers to the behaviour set during the entrepreneurial process. It generally denotes a series of acts with which entrepreneurial firms develop resources creatively to pursue opportunities and realize opportunity value [31,80,176]. Looking at how EVs are managing the crisis caused by the COVID-19 pandemic and the lockdown, we observe that EVs employ some strategies to manage the crisis, minimize the risk of failure as well as attempt to leverage new opportunities created by the crisis. A critical analysis of the PSD reveals that a combination of Entrepreneurial Actions (EAs), Entrepreneurial Orientations (EOs), with assistance from various support-systems could probably be the reasons for the EVs to manage the crisis better. A further study on EA, EO, and Support-Systems is essential for formulating a proposition.

6.1. Evidence from literature on entrepreneurial actions, orientations, and support-systems

We investigate the contribution of EAs, EOs, and support-systems towards crisis management of EVs based on COVID-19 literature.

6.1.1. Entrepreneurial actions (EAs)

EAs can contribute to the restructuring and adaptation of an organization during and after a crisis [106]. Research-based evidence is available that EAs can be used to overcome the exogenous shock caused by COVID-19 [74]. These EAs are (1) crisis and disaster planning [74], (2) pivoting [122]), (3) Hustle/Idea blitz [12,68], (4) frugality [74], (5) including financial prudence [74], (6) emotional support (through networking and lobbying initiatives [74]. Other possible EAs that can be taken during the crisis are(7) bricolage [74,101,106], (8) effectuation [74,106], (9) agility [101], and (10) R&D [163], which are justified below. Since resources are limited during a crisis/disaster, applying bricolage [74,101,106] helps in optimum resource utilization. Similarly, applying the principle of effectuation [74,106] also helps to use the available resources to find a solution. Agility and quick decision-making are vital during a crisis/disaster [101]. Studies have also established that R&D is essential to quickly move out from a crisis into the post-crisis stage; in fact, R&D will lead to better survival chances, growth, and profitability [163]. In summary, the above-mentioned ten EAs, as identified from our SLR database, have been observed to manage a crisis/disaster better. The list of EAs can be further enhanced based on future publications.

6.1.2. Entrepreneurial orientations (EOs)

EOs serve as a firm's driver towards improved performance and success [33], which is essential to overcome the current and post-COVID crisis [209]. As per the multi-dimensional concept, the five components3 of EO can co-exist or vary independently, and all of them need not co-exist in a firm [33,182]. Researches [101] on entrepreneurship, supply chain management, and strategic management have highlighted the importance and role of EOs during the COVID-19 crisis and indicated the applicability of these five components: (1) the propensity to experiment through innovation, (2) being proactive in anticipating and acting on future opportunities and making strategic moves, (3) the ability to take calculated risks which shows the inclination to take bold actions, (4) possessing competitive aggressiveness, where a firm directly engages its competition, and (5) having autonomy, where the organization members have the freedom to develop an idea towards its completion. These five components of EOs are essential for managing a crisis/disaster.

6.1.3. Support systems

EVs need supports from multiple sources. During the COVID-19, the following components were used as supports to manage the crisis: (1) Technology in the form of Digitalization, IoT, etc. [185,212], (2) Entrepreneurial mindset/thinking [11,74], (3) Finance/investment [25,45], (4) Supportive Government/Public policies [25,90], (5) Management tools and techniques [84,88], (6) Leadership [33], (7) Resources [46,74,111], and (8) Entrepreneurial team [188]. These supportive components are not exhaustive. Some more can be added; we have listed the above based on the information available in our SLR database. We call all these components together as Entrepreneurial Support (ES) and highlight that these ESs are essential to overcome the crisis.

6.2. Proposition development

From the study of the above literature, we observe that EVs combine entrepreneurial actions (EAs) and entrepreneurial orientations (EOs) with entrepreneurial supports (ESs) to overcome the crisis. We, therefore, propose to call the combination of EAs and EOs with ESs as Entrepreneurial Interventions (EIvs) and underscore that EIvs can be used to manage a crisis and disaster and improve organizational resilience. The above proposition will be strengthened and validated based on evidence from eleven case studies.

7. Case study review of the applicability of EIv for crisis management

The proposition that Entrepreneurial Interventions (EIvs) can be used to manage a crisis has been developed based on the study of EVs, which experienced the crisis due to COVID-19. We first attempt to validate this proposition by checking its applicability for general management in large organizations, which experienced the COVID-19 pandemic. Then, we shall validate in the context of general management in large organizations, which experienced a crisis other than that caused by COVID-19.

7.1. Evidence from organizations that experienced the COVID-19 pandemic crisis

Four articles containing case studies from quality journals (only A*, A, and B of ABDC ranking) were selected, in which organizations encountered crises due to the COVID-19 pandemic. These four articles cover large organizations [16,34] and general management [42,209]. They were analyzed to identify the components of EAs and EOs, with ESs employed to either minimize the risk of failure or leverage the opportunity created by the crisis. The outcome of this study is presented in Table 2 . We observed some components of EA, EO, with ES employed to overcome the COVID-19 crisis for each case. The EAs'/EOs'/ESs’ components have been highlighted in bold and italics in Table 2. All the components indicated for EAs, EOs, with ESs in sub-section 6.1 are cumulatively present across all four cases.

Table-2.

Evidence of Entrepreneurial Interventions made during COVID-19 by large organizations as a crisis management strategy.

| Reference | Crisis/disaster details | EA taken | EO used | ES availed |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| How Michelin-starred chefs are being transformed into social bricoleurs? An online qualitative study of luxury foodservice during the pandemic crisis [16] | The luxury foodservice sector is facing a severe crisis due to lockdown, and the business was forced to close. | Social bricolage, since the chefs used the available resources and prepared food for health workers. These chefs used the available ingredients to innovatively devise recipes and thereby applied effectuation. These elite chefs used their social status, reputation, and lobbying/networking power to influence and formulate government policies supporting the food industry during the pandemic. |

These chefs relearned creative and innovative ways to cook, pack and deliver luxury meals. | These chefs adopted Entrepreneurial thinking to develop a multilevel response strategy to tackle social issues. These elite chefs had a legitimate status to act as influential leaders, influence public opinion, and formulate government policies in favour of hotel/restaurant business. |

| Employee Adjustment and Well-Being in the Era of COVID-19: Implications for Human Resource Management [34] | Employees were struggling with the new working environment. The Human Resource (HR) professionals were attempting to help them. | To ensure a smooth transition into the new working style, the HR professionals are undertaking multiple approaches such as ‘work-from-home, online recruitment, virtual training, etc. By using the available resources/techniques and not much worried about the long-term outcomes of these actions, the HR professionals are applying the principle of effectuation. Conduct online training/social events to help the employees to socially connect and network with other employees. |

The proactive orientation of HR professionals for ensuring the relevance of person-environment fit (P-E fit) for their employees. Providing autonomy to employees during the work-from-home scenario so that the work-life balance is not affected. |

The HR professionals are shifting the recruitment, selection, and training to virtual mode, using technology (Digitalization). The HR professionals are applying entrepreneurial mindset/thinking for the benefit of employees. |

| Reflections on threat and uncertainty for the future of elite women's football in England [42] | The elite women's football team in England is facing a threat and uncertainty during the COVID-19 due to economic repercussions, and the need for maintaining players' well-being, and related contractual issues. | Due to the reduced financial inflow from corporate companies, crisis planning is undertaken to avoid football clubs' closing. During the financial crisis, the football clubs are reducing their costs by applying all possible financial prudence. Also, they are applying bricolage in using scarce financial resources. The football associations are attempting to pivot their business model by conducting matches near tourist sites. |

The Women's clubs attempted to explore aninnovative source of revenue through crowdfunding. The women's football team plans to proactively integrate with the professional men's club (as men's clubs are better funded). Secondly, such integration can enhance the competitive aggressiveness of football clubs among other sports. |

Women's clubs are encouraged to embrace an entrepreneurial mindset to explore revenue generation and improve their wellbeing. To increase the financial inflow and retain the league's integrity, regular crisis management reviews are undertaken by the higher level of leadership, and suitable supportive policies are being formulated. To ensure the well-being of the players, additional resources (infrastructure) are employed. Only a team of relevant stakeholders (governing bodies of football clubs, players associations, football associations, etc.) with coordinated action will help the football clubs to overcome the crisis. |

| International entrepreneurship in the post-Covid world [209] | Travel restrictions on Global and International businesses (IBs), caused due to lockdown. | To overcome the inability to travel IBs have shifted focus on local development of R&D, as they believe this will give them a unique competitive advantage. These firms may collaborate with local ventures to engage in frugal innovations so that local resources are best used by way of bricolage. Due to digital communication technologies, IBs have achieved greater responsiveness and agility in handling IBs. |

IBs attempt to use universities' discoveries, aiming to convert these innovative ideas/prototypes into products and goods. The IBs are taking a calculated risk, as their challenges to handle stakeholders across the globe have increased. |

Digital technology helps IBs to connect with firms across the globe. |

7.2. Evidence from organizations during crises (non-COVID-19)

To further validate that EIvs can be used to manage crises in general, we examine the application of this proposition in large organizations and general management by taking case studies unrelated to COVID-19. We explore these case studies to review if various components of EIvs have been employed. Seven case studies, two from an organizational [13,89] and five from a general management perspective [73, 144 (3 separate cases), 100], were analyzed. After a complete analysis and synthesis of these cases, the outcome is summarized in Table 3 . For each case, the explicit crisis management approach adopted, as indicated by the respective author(s), is mentioned. The EA and EO, with ES components employed to overcome the crisis, are indicated (in bold and italics) separately. The above table considers cases from various sectors and contexts such as manufacturing, reconstruction projects, natural calamities such as earthquake, fire, tsunami, civil calamity, different types of businesses such as SMEs, large organizations, and corporates.

Table 3.

Evidence of Entrepreneurial Interventions made as a crisis management strategy by any business/organization and in general management.

| Reference | Details of Crisis/Disaster | Details of Crisis/Disaster management as per Author(s) | EAs taken | EOs used | ESs availed |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Crisis management for SMEs: insights from a multiple-case study [89] | Firm C is a US automobile stamping firm, a supplier to three leading automobile manufacturers in Detroit. The technology used by Firm C got obsolete, and therefore, their major customers' de-sourced them, leading them into a crisis. |

Immediate actions by Firm-C:

|

Crisis plan: The firm established a crisis management plan and a systematic recovery plan through insurance. Business model Pivot: The firm changed its target market. Financial Prudence: Reduced the operational costs by laying off employees and reducing working time. Networking: The top management was proactively communicating with their suppliers and customers to rebuild their relationships. |

Proactiveness: Observed their competitors undertake technological innovation and foresaw the crisis. Innovativeness: Undertook technological innovation, as they realized only this could help them sustain in the market. Competitive Aggressiveness: They increased their competitive aggressiveness by investing in technology. |

Technology: Updated their technological infrastructure. Investment: Made a significant investment in technology. |

| Towards the agility of collaborative workflows through an event driven approach – Application to crisis management [13] | This article discusses a software/platform which supports decision-making during crises. The platform's use is illustrated in the context of the Fukushima nuclear disaster. . |

|

Crisis/disaster management plan: Use of adaptative strategy. Agility: The platform (Agility service) works on the principle that agility is essential during collaboration. Pivot: Used adaptative and pivoting strategies during crises. Networking: This platform facilitated collaboration (through networking) between heterogeneous organizations that are connected with each other. |

Proactiveness: The proposed platform proactively orchestrates and drives collaborative situations. Risk-taking: The platform helps the decision-maker to select a crisis management solution with risk as one of the variables. |

Technology: Information systems architecture for the development of the platform. Management tools: The ‘Agility service’ platform helps the decision-makers’ use of appropriate tools for crisis response. Resources: The available resources are used as a meta-type variable. Team: The proposed platform helps organizations to collaborate as a team to face crises. |

| Notre-Dame Is Burning: Learning from the Crisis of a Superstar Religious Monument [73] | The fire accident took place at Notre-Dame in April 2019. The Notre-Dame fire accident was considered a Processual crisis. |

Immediate response:

|

Disaster Recovery Plan: A restoration bill was drafted immediately and adopted by the National Assembly. Idea Blitz: Tourists can experience an online digital show during the restoration work so that they are not disappointed. Financial prudence: While seeking funds for restoration, donations were exempted from tax. |

Aggressiveness: The national leadership demonstrated aggressiveness to address the crisis. The French President addressed the public from the burning cathedral. Innovativeness: The reconstruction work was planned by calling for an ‘international architectural competition’. The restoration team adopted innovative ways to reconstruct without damaging the existing structure. |

Digital technology: During restoration work, the tourists were shown digital movies about the monument. Supportive Government policies: The Government issued supportive policies to overcome the crisis. Leadership: Role played by the Government in taking the views of relevant stakeholders such as Heritage experts, Architects, religious and political views before finalizing the restoration plan. |

| Intentionally building relationships between participatory online groups and formal organizations for effective emergency response [144] | This paper has presented four case studies Case-1: Violence in Kenya post-election-2007-08, that claimed the lives of around 1500 people. |

|

Being Frugal: A dozen software developers and bloggers designed and build ‘Ushahidi’. This simple and cost-effective solution (Frugal) ensured sharing of information leading towards providing help to affected victims. Agility: Quickly processing/categorizing information in ‘Ushahidi’. This was happening in near real-time by the volunteers. Networking: The Ushahidi volunteers actively build partnerships with Kenyan NGOs and with the local contacts at the site of incidence to provide support. |

Innovativeness: Bloggers developing Ushahidi using Google maps. Proactiveness: A Kenyan lawyer calling out bloggers to develop a platform to help violence victims. |

Technology: Information Communication Technology (ICT) enabled bloggers to develop Ushahidi. Team: Formation of teams by individuals (Bloggers, NGOs, Social workers, etc.) to develop a system to coordinate peacebuilding efforts in Kenya. |

| -do- | Case-2: An earthquake of 7.0 magnitude struck Haiti on 12 January 2010, leaving several people homeless without basic amenities. |

|

Frugal: OSM volunteers using donated satellite imagery to develop a digital map. Idea Blitz: (a) The idea of deploying ‘Ushahidi’ in Haiti as ‘Ushahidi-Haiti’ platform; (b) Subsequently, the ‘Ushahidi-Haiti’ platform being modified with an open chatroom, where volunteers could translate messages; (c) Integration of ‘Mission-4636′ and the Ushahidi-Haiti platform. Bricolage: (a) Diverse resources were brought together by Haitian telecommunication companies, local radio stations, NGOs, and several global organizations to develop and launch ‘Mission-4636'; (b) Translation of SMSs by translators (available resources) staying in 49 countries. Agility: The average processing speed of response for each SMS after its receipt was less than 10 min. Networking: Multiple organizations (Haiti's telecommunication companies, local radio stations, and NGOs) and volunteers worked together. |

Proactiveness: (a) In less than 2 h after the earthquake struck Haiti, the Ushahidi-Haiti platform was set-up; (b) a computational linguist calling for volunteers to translate SMS messages. Innovativeness: (a) Updating ‘Ushahidi-Haiti’ platform with chat room for translators, and then integrating it with Mission 4636; (b) Taking the support of translators from 49 counties to translate SMSs, using Facebook. |

Technology: Use of the Ushahidi-Haiti platform, Mission-4636, SMS translation, OSM Maps to acquire, process, and share data/information. Funding: Donations obtained from the world bank and imagery companies. Assumed leadership role: (a) A Ph.D. student set up the Ushahidi-Haiti platform and organized more than 200 volunteers to process data. (b) A computational linguist was organizing more than 1000 volunteers to translate SMS messages. Team: Self-formed teams (200 ‘Ushahidi-Haiti’ volunteers, 1000 translators, 600 OSM volunteers) working towards earthquake relief. |

| -do- | Case-4: An earthquake of 9.0 magnitude struck Japan on 11 March 2011, followed by Tsunamis causing damage to the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant, resulting in enormous amounts of radiation leaking into the environment. |

|

Frugal: low-cost development of radiation monitoring device-'bGeigie Nano'. Blitz: Idea to develop a radiation monitoring system, as the government-provided data was felt incomplete and inadequate. Bricolage: Resources across the globe join hands to work together ((a) 200 volunteers participated in this crisis mapping project, (b) 500 OSM volunteers created digital maps, (c) designers, engineers, computer programmers, and scientists developed radiation monitoring device) Networking: Volunteers among OSM and Safecast working together for disaster management. |

Innovativeness: An innovative low-cost radiation monitoring device was designed, prototyped, and developed by ‘Safecast’. This was deployed, and approximately 18 million radiation data points were collected. |

Technology: Digital technology was used for (a) developing digital maps, (b) generating radiation data. Funding: A crowdfunding platform was used to collect funds for developing the radiation monitoring device. Entrepreneurial team: (a) A team of three key founding members, along with designers, engineers, computer programmers, and scientists, developed a radiation monitoring device. (b) The Japanese OSM community (200 volunteers) jointly created a digital crisis map. |

| Balancing and stabilizing South Asia: challenges and opportunities for sustainable peace and stability [100] | The constant conflict between India and Pakistan, due to terrorism and the Kashmir issue. This has become one of the major issues between these two countries, fearing escalation to military/nuclear confrontation. | To focus on crisis management rather than conflict resolution. This can be done through

|

Crisis plan: Both countries attempt to divide the bigger issues into smaller issues for working out a solution. Financial prudence: Both countries want to avoid the cost of war. Networking: Role of third-party countries in preventing major military escalations. This networked relationship with other countries helps in preventing crisis escalation. Effectuation: Both India and Pakistan, focusing only on their immediate goals rather than their ultimate goal (conflict resolution). Handling the immediate goal is under the control of the local military power. This is preventing crisis escalation. R&D: The Think-tanks from both countries are advising their respective Governments on long-term strategies. |

Innovativeness: A regular confidence-building measure being formulated and adopted from both sides. Proactiveness: Both countries are evaluating the situation and taking corrective actions constantly and, quickly. . Autonomy: Freedom given to the team which undertakes confidence-building measures, especially for building backchannel confidence-building measures. |

Technology: Remote possibility of the accidental use of nuclear weapons during peacetime is pre-empted by technological advancement.. Leadership: The national/political leaders' conscious effort to show self-restraint and the “wait and see” approach signals the seriousness of ending the crisis mutually. |

While developing Table-2, Table 3, we observed that some components of EAs, EOs, and ESs were explicitly or inherently used to manage the crisis. In a few instances, we performed thematic coding [170] to identify the use of EAs/EOs/ESs. The first and second authors did coding separately to confirm the correct interpretation. These case studies reinforce the observation that all the components of EAs/EOs/ESs need not be applied concurrently. To manage crisis/disaster better, a suitable combination of EAs/EOs/ESs needs to be employed, and it is contingent on the environmental condition.

8. Conceptual model on crisis management using entrepreneurial intervention

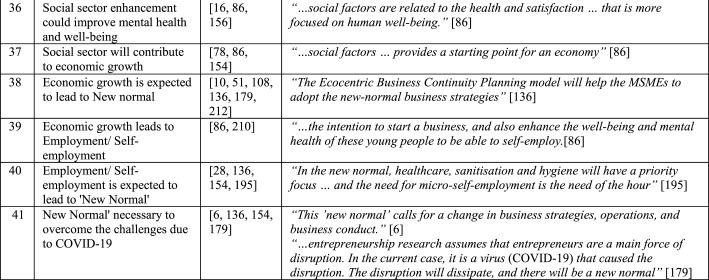

After studying the behaviour of EVs during the crisis caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, a phenomenon structure diagram (PSD) has been developed (Fig. 6 Fig. 7(a)). From this PSD, it is observed that EVs have used entrepreneurial actions (EAs) and entrepreneurial orientation (EOs), with entrepreneurial supports (ESs) to minimize the risk of failure as well as leverage the opportunities created during the crisis. Based on this, a proposition has been developed which states that Entrepreneurial Interventions (EIvs), which are a combination of EAs and EOs, with ESs, can be made to manage a crisis better by handling the negative and positive impacts of a crisis/disaster. The correctness of this proposition has been checked with eleven case studies on crises that affected large organizations and general management. In all these cases, it is observed that appropriate combinations of components of EAs and EOs, with ESs, were employed to minimize the negative effects of the respective crises and leverage the opportunities. The Temporal analysis (Section 4.3) of the pre-COVID-19 era shows that the failure rates of EVs were high during the earlier pandemics. Also, during those pandemics, entrepreneurship and social entrepreneurship helped to reduce unemployment and saved certain communities. A conceptual model has been developed based on these studies (PSD, Temporal analysis, and case studies analysis). The conceptual model shows that EIvs, which are a combination of EAs and EOs, with ESs, can be made to manage the negative and positive impacts of a crisis. The negative impacts of a crisis could lead to the failure of enterprises, whereas the positive impacts of a crisis could facilitate these enterprises to leverage the crisis-given new opportunities. This conceptual model is presented in Fig. 8 .

Fig. 8.

Conceptual model for Crisis/Disaster Management using Entrepreneurial Interventions.

In the above figure, we can observe that when an enterprise is impacted by a crisis or disaster (shown in the left corner), it can employ Entrepreneurial Interventions (EIvs). The components of EAs and EOs, with ESs, are listed in the center of the model. These components have been identified from the literature on EVs. The EIvs during a crisis/disaster will either (a) minimize the risk of failure of enterprises, or (b) help its management to recover faster, or (c) help enterprises to leverage the opportunities generated. Thus, Entrepreneurial Interventions can be used as a crisis management strategy and to improve organizational resilience.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first time such a model has been developed for crisis/disaster management based on the behaviour observed in EVs during a crisis. This conceptual model is a unique outcome of the above multi-disciplinary study. It presents a pragmatic approach [3] by way of being a ready reckoner in managers' hands to manage an organizational crisis. It also appears that some of the above-identified components of EAs, EOs, and ESs can be applied during three different broad stages of a crisis, namely pre-crisis, during-crisis, and post-crisis stages; this would need further investigation. The strategy to resolve a crisis must be decided based on the environmental conditions. A single solution may not fit all conditions [84]. Crisis management needs custom-made strategies [84,146]. This is in line with the view that crises do not follow a clear pattern, and every crisis could be unique and needs to be studied for its context and industry sector [84,85]. Thus, a contingent approach towards crisis management [84] would be appropriate, and our proposed EIvs model would support such an approach.

9. Limitations, implications, and conclusions

9.1. Limitations

The SLR on COVID-19, Pandemic, and EVs has been undertaken based on the published works available in the Scopus and WoS databases till mid-Oct 2020 only. Research works beyond this time, and other databases have not been considered in this article. These published articles capture the initial period of the COVID-19 crisis, and thus they may not capture the complete behaviour. However, a quick review of subsequent publications reveals no major conceptual changes in the articles published subsequently. Therefore, our findings based on this SLR published works could be largely relevant. Secondly, the 295 research gaps identified through this SLR would need further investigations [138] to see if there are any research opportunities corresponding to each gap. Thirdly, the above research has been undertaken mainly based on published literature and case studies. Therefore, this would need further empirical validation. The existing component list of EAs, and ESs, has been developed based on the 154 published articles; this list can be further enhanced.

9.2. Implications

9.2.1. Theoretical contributions

The behaviour of EVs during the COVID-19 pandemic has been captured using a PSD. To the best of our knowledge, such development of PSD has been undertaken for the first time. Future researchers can develop similar PSDs to study (a) the impacts of crises on other types of organizations, and (b) the impacts of other types of crises, such as natural disasters, on different types of organizations. Secondly, from the behaviour of the EVs, a conceptual model is developed for EIvs, which are combinations of EAs and EOs with ESs for crisis/disaster management. Researchers can extend this study by empirically validating the EIvs model for (a) different stages of the crisis, namely pre-, during- and post-crisis stages, (b) linking the EIvs model with ‘proactive’ and ‘reactive’ resilience/capacity, and (c) studying resilience as a dynamic attribute. Thirdly, this paper points out and justifies the applicability of contingency theory as a crisis management strategy. Future researchers can use this paper to extend the existing knowledge on either ‘contingency theory’ or ‘crisis management strategy’. In addition, this paper has identified 295 gaps in existing literature related to the COVID-19 pandemic and EVs. Future researchers can study these gaps for research potential [138] and undertake research.

9.2.2. Managerial implications

This article has generated a pragmatic set of ten components of EAs, five components of EOs, and eight components of ESs to overcome crises/disasters as presented in Fig. 8. Owners and/or managers can use this list to formulate crisis management strategies. In addition, our paper suggests owners and/or managers that crisis management strategies need to be formulated depending on the environmental condition and surrounding situation. The approach of ‘one-size, fits for all’ does not work.

9.3. Conclusions

In this article, based on a Structured Literature Review (SLR) using Bibliometrics of 154 publications, an understanding of Entrepreneurial Ventures’ behaviours during the crisis caused by the pandemics is presented. An abstraction of the entrepreneurial behaviours during the COVID-19 crisis is diagrammatically represented in the form of a PSD, which shows that COVID-19, depending upon the context, causes either slowdowns or growth of EVs. This PSD also highlights the various combinations of Entrepreneurial Actions (EAs) and Entrepreneurial Orientations (EOs), with Entrepreneurial Supports (ESs) that can be employed on a contingency basis, depending upon the situation in the surrounding environment, to deal with the negative or positive impacts caused by a crisis. From the behaviours of EVs, a conceptual model of crisis management employing Entrepreneurial Interventions (EIvs) has been developed. EIvs, which are a combination of EAs and EOs with ESs, can be made to manage a crisis better by handling the negative and positive impacts of a crisis/disaster. The EIvs model highlights the applicability of contingency theory and provides a pragmatic solution for formulating a crisis management strategy and improving the dynamic resilience of an organization. This article has laid a theoretical foundation for crisis management and resilience based on evidence from entrepreneurship and has thus attempted to integrate different fields.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Footnotes

EO refers to strategic posturing through specific activities, practices, and processes, enabling an enterprise to create value by engaging in an entrepreneurial endeavor. EO serve as a firm's driver towards improved performance and success [33]. Further details in section 6.1.2.

EAs contribute to the restructuring and adaptation of an organization during and after a crisis [106]. Further details of EA are provided in section 6.1.1.

The five componets of EO are (1) Innovation, (2) Proactiveness, (3) Risk-taking (4) Competitive aggressiveness, and (5) Autonomy.

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijdrr.2022.102830.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following are the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Asgary A., Anjum M.I., Azimi N. Disaster recovery and business continuity after the 2010 flood in Pakistan: case of small businesses. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduc. 2012;2:46–56. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aceytuno M.T., Sánchez-López C., de Paz-Báñez M.A. Rising inequality and entrepreneurship during economic downturn: an analysis of opportunity and necessity entrepreneurship in Spain. Sustainability. 2020;12(11):4540. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ansell C., Boin A. Taming deep uncertainty: the potential of pragmatist principles for understanding and improving strategic crisis management. Adm. Soc. 2019;51(7):1079–1112. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Akpan I.J., Soopramanien D., Kwak D.H. Cutting-edge technologies for small business and innovation in the era of COVID-19 global health pandemic. J. Small Bus. Enterpren. 2020:1–11. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Akpan I.J., Udoh E.A.P., Adebisi B. Small business awareness and adoption of state-of-the-art technologies in emerging and developing markets, and lessons from the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Small Bus. Enterpren. 2020:1–18. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Al‐Sarraf A. Bankruptcy reform in the Middle East and North Africa: analyzing the new bankruptcy laws in the UAE, Saudi Arabia, Morocco, Egypt, and Bahrain. Int. Insolv. Rev. 2020;29(2):159–180. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ateljevic I. Transforming the (tourism) world for good and (re) generating the potential ‘new normal. Tourism Geogr. 2020:1–9. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Audretsch D.B., Moog P. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice; 2020. Democracy and Entrepreneurship. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bacq S., Geoghegan W., Josefy M., Stevenson R., Williams T.A. The COVID-19 Virtual Idea Blitz: marshaling social entrepreneurship to rapidly respond to urgent grand challenges. Bus. Horiz. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.bushor.2020.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Barthe-Delanoë A.M., Montarnal A., Truptil S., Bénaben F., Pingaud H. Towards the agility of collaborative workflows through an event driven approach–Application to crisis management. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduc. 2018;28:214–224. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Asgary A., Ozdemir A.I. Global risks and tourism industry in Turkey. Qual. Quantity. 2020;54(5):1513–1536. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Batat W. How Michelin-starred chefs are being transformed into social bricoleurs? An online qualitative study of luxury foodservice during the pandemic crisis. J. Service Manag. 2020 doi: 10.1108/JOSM-05-2020-0142. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bruderl J., Schussler R. Organizational mortality: the liabilities of newness and adolescence. Adm. Sci. Q. 1990:530–547. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Brown R., Rocha A. Entrepreneurial uncertainty during the Covid-19 crisis: mapping the temporal dynamics of entrepreneurial finance. J. Business Ventur. Insights. 2020;14 [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brown R., Rocha A., Cowling M. Financing entrepreneurship in times of crisis: exploring the impact of COVID-19 on the market for entrepreneurial finance in the United Kingdom. Int. Small Bus. J. 2020;38(5):380–390. doi: 10.1177/0266242620937464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Annarelli A., Nonino F. Strategic and operational management of organizational resilience: current state of research and future directions. Omega. 2016;62:1–18. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cardon M.S., Stevens C.E., Potter D.R. Misfortunes or mistakes?: cultural sensemaking of entrepreneurial failure. J. Bus. Ventur. 2011;26(1):79–92. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cai L., Peng X., Wang L. The characteristics and influencing factors of entrepreneurial behaviour: the case of new state-owned firms in the new energy automobile industry in an emerging economy. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change. 2018;135:112–120. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chowdhury M., Prayag G., Orchiston C., Spector S. Postdisaster social capital, adaptive resilience and business performance of tourism organizations in Christchurch, New Zealand. J. Trav. Res. 2019;58(7):1209–1226. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cannavale C., Nadali I.Z., Esempio A. Entrepreneurial orientation and firm performance in a sanctioned economy–does the CEO play a role? J. Small Bus. Enterprise Dev. 2020 doi: 10.1108/JSBED-11-2019-0366. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Carnevale J.B., Hatak I. Employee adjustment and well-being in the era of COVID-19: implications for human resource management. J. Bus. Res. 2020;116:183–187. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2020.05.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Castriotta M., Loi M., Marku E., Naitana L. What's in a name? Exploring the conceptual structure of emerging organizations. Scientometrics. 2019;118(2):407–437. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chowdhury M.M.H., Quaddus M. Supply chain resilience: conceptualization and scale development using dynamic capability theory. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2017;188:185–204. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Koronis E., Ponis S. Better than before: the resilient organization in crisis mode. J. Bus. Strat. 2018;39(1):32–42. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Clarkson B.G., Culvin A., Pope S., Parry K.D. Covid-19: reflections on threat and uncertainty for the future of elite women's football in England. Manag. Sport Leisure. 2020:1–12. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cobo M.J., López-Herrera A.G., Herrera-Viedma E., Herrera F. An approach for detecting, quantifying, and visualizing the evolution of a research field: a practical application to the fuzzy sets theory field. J. Inform. 2011;5(1):146–166. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cowling M., Brown R., Rocha A. Did you save some cash for a rainy COVID-19 day? The crisis and SMEs. Int. Small Bus. J. 2020 doi: 10.1177/0266242620945102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Csath M. Crisis situations: how should micro, small and medium enterprises handle them with a long term view? Dev. Learn. Org. Int. J. 2020 doi: 10.1108/DLO-04-2020-0086. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Duchek S. Organizational resilience: a capability-based conceptualization. Business Res. 2020;13:215–246. [Google Scholar]

- 50.de Araujo Lima P.F., Crema M., Verbano C. Risk management in SMEs: a systematic literature review and future directions. Eur. Manag. J. 2020;38(1):78–94. [Google Scholar]

- 51.De Massis A., Rondi E. COVID‐19 and the future of family business research. J. Manag. Stud. 2020 doi: 10.1111/JOMS.12632. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Debata B., Patnaik P., Mishra A. COVID‐19 pandemic! It's impact on people, economy, and environment. J. Publ. Aff. 2020;20(4) [Google Scholar]

- 54.Denyer D., Tranfield D. In: The Sage Handbook of Organizational Research Methods. Buchanan D.A., Bryman A., editors. Sage Publications Ltd; 2009. Producing a systematic review; pp. 671–689. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Desa G., Jia X. Sustainability transitions in the context of pandemic: an introduction to the focused issue on social innovation and systemic impact. Agric. Hum. Val. 2020;37(4):1207–1215. doi: 10.1007/s10460-020-10129-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Devece C., Peris-Ortiz M., Rueda-Armengot C. Entrepreneurship during economic crisis: success factors and paths to failure. J. Bus. Res. 2016;69(11):5366–5370. [Google Scholar]

- 57.de Vries H.P., Hamilton R.T. Smaller businesses and the Christchurch earthquakes: a longitudinal study of individual and organizational resilience. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduc. 2021;56:102125. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Jia X., Chowdhury M., Prayag G., Chowdhury M.M.H. The role of social capital on proactive and reactive resilience of organizations post-disaster. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduc. 2020;48:101614. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Eggers F. Masters of disasters? Challenges and opportunities for SMEs in times of crisis. J. Bus. Res. 2020;116:199–208. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2020.05.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ejupi-Ibrahimi A., Ramadani V., Ejupi D. Family businesses in North Macedonia: evidence on the second generation motivation and entrepreneurial mindset. J. Fam. Bus. Manag. 2020 doi: 10.1108/JFBM-06-2020-0047. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Fairlie R. The impact of COVID‐19 on small business owners: evidence from the first three months after widespread social‐distancing restrictions. J. Econ. Manag. Strat. 2020;29(4):727–740. doi: 10.1111/jems.12400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Faulkner B. Towards a framework for tourism disaster management. Tourism Manag. 2001;22(2):135–147. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Fisher G., Stevenson R., Burnell D. Permission to hustle: igniting entrepreneurship in an organization. J. Business Ventur. Insights. 2020;14 [Google Scholar]

- 69.Fossen F.M. Self-employment over the business cycle in the USA: a decomposition. Small Bus. Econ. 2020:1–19. doi: 10.1007/s11187-020-00375-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Games D., Sari D.K. Earthquakes, fear of failure, and wellbeing: an insight from Minangkabau entrepreneurship. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduc. 2020;51:101815. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Gombault A. Notre-dame is burning: learning from the crisis of a superstar religious monument. Int. J. Arts Manag. 2020;22(2):83–94. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Giones F., Brem A., Pollack J.M., Michaelis T.L., Klyver K., Brinckmann J. Revising entrepreneurial action in response to exogenous shocks: considering the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Business Ventur. Insights. 2020;14 [Google Scholar]

- 76.González R.J., Marlovits J. Life under lockdown: notes on covid‐19 in Silicon Valley. Anthropol. Today. 2020;36(3):11–15. doi: 10.1111/1467-8322.12574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Haynie J.M., Shepherd D.A., McMullen J.S. An opportunity for me? The role of resources in opportunity evaluation decisions. J. Manag. Stud. 2009;46(3):337–361. [Google Scholar]

- 83.Krishnan S.N., Ganesh L.S., Rajendran C. The Square Inch quilting studio: survival strategies for a lifestyle enterprise. Int. J. Enterpren. Innovat. 2021 doi: 10.1177/14657503211044771. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Krishnan S.N., Ganesh L.S., Rajendran C. Management accounting tools for failure prevention and risk management in the context of Indian innovative start-ups: a contingency theory approach. J. Indian Business Res. 2021 doi: 10.1108/JIBR-02-2021-0060. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Henderson J.C. Communicating in a crisis: flight SQ 006. Tourism Manag. 2003;24(3):279–287. [Google Scholar]