Abstract

We aimed to evaluate the clinical benefits of dexmedetomidine (DEX) in comparison with the standard of care (SOC) sedation in critically ill, septic patients. Electronic databases (PubMed, EMBASE, Cochrane Central, Scopus, and Google Scholar) were systematically searched to identify only randomized clinical trials performed up until February 12, 2021. The primary outcomes were 28-day mortality, 90-day mortality, and intensive care unit (ICU) length of stay (LOS). We calculated risk ratios (RRs), 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for dichotomous data, and weighted mean differences (WMDs) for continuous data using a random-effects model. Seven randomized clinical trials were included, with a total of 529 patients in the DEX group and 520 patients in the SOC group. Compared with SOC, DEX was associated with a nonstatistically significant reduced 28-day mortality (RR = 0.76; 95% CI [0.51, 1.14]; P = 0.19), 90-day mortality (RR = 0.94; 95% CI [0.75, 1.18]; P = 0.60), and ICU LOS (WMD = −0.85; 95% CI [-2.60, 0.90]; P = 0.34). We conclude that among septic patients on sedation, the use of DEX in the ICU demonstrated no significant difference from SOC sedation protocols with respect to 28-day mortality, 90-day mortality, and total ICU LOS. Our findings suggest that DEX does not confer clinical benefit over SOC sedation in critically ill patients with sepsis.

Keywords: Dexmedetomidine, meta-analysis, sedation, sepsis, systematic review

Sepsis is a systemic inflammatory syndrome secondary to infection.1 In the last few years, there has been increasing interest in immunomodulatory agents like dexmedetomidine (DEX)2 in the battle against sepsis, with no apparent benefit proven to date. Dexmedetomidine is a selective alpha-2 adrenergic agonist with sedative characteristics.3 There have been reports that DEX has an inhibiting effect on the inflammatory response, resulting in minimization of organ damage.4,5 DEX, propofol, and benzodiazepines (i.e., midazolam, lorazepam, and diazepam) have routinely been used for sedation of septic patients. Our study aimed to update the current evidence and determine whether sedation with DEX has significant clinical benefits with regards to 28-day mortality, 90-day mortality, and intensive care unit (ICU) length of stay (LOS) in the septic adult patient requiring invasive mechanical ventilation when compared to the standard of care (SOC) sedation regimens.

METHODS

This systematic review was conducted according to Preferred Reporting for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA), as recommended by the Cochrane Collaboration.6,7 A systematic literature review using PubMed, EMBASE, Cochrane Central, Scopus, and Google Scholar was performed using the terms (“Dexmedetomidine” OR “alpha 2-adrenoceptor agonist”) AND (“sepsis” OR “septic shock” OR “septic”) and modified according to the database. We looked for literature published from inception until February 12, 2021, and used the ‘related articles’ feature to broaden our search. We included additional articles found in the review of bibliographies or suggested by coauthors based on their relevance to the selected search terms.

We saved the search results in the EndNote application and transferred them to the Covidence website. Two reviewers (BA and BM) independently performed the title and abstract screening. Conflicts were resolved through a third author (BK). Next, we reviewed the selected articles using the following inclusion criteria: randomized control trials (RCTs); study population involving patients with sepsis; intervention including DEX; at least one primary outcome of interest reported; and English text. We excluded the observational studies, studies that included nonseptic patients, abstracts, and non–full-text articles.

Two reviewers (BA, BM) extracted the data independently from included studies. A consensus was reached by the third author (BK) in the case of any inconsistencies between the two reviewers. The data extracted for qualitative synthesis included location, year of study, study design, sample size, population age (in years), Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation (APACHE) II score, and Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) score. The data were entered into a Google spreadsheet by two authors (BA, BM) and reviewed by a third author (BK). Any discrepancies were resolved by discussion among the authors.

We used the Cochrane Collaboration tool8 to perform quality assessment and to assess the risk of bias in the included clinical trials in the following domains: random sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding of participants and health care personnel, blinding of outcome assessment, incomplete outcome data, evidence of selective reporting, and other biases. The evaluation of the methodological quality of the studies was subsequently categorized into low risk, high risk, or unclear risk of bias.

The primary outcomes were 28-day mortality, 90-day mortality, and ICU LOS. Secondary outcomes included delirium-free days, ventilator-free days, changes in heart rate, and changes in the mean arterial pressure (MAP).

We calculated the pooled risk ratios (RRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for dichotomous data. Weighted mean difference (WMD) and 95% CIs were utilized for continuous data. We used a random-effects model for the analysis of the results. We assessed heterogeneity using I2 statistics. All analyses were performed using RevMan v5.3 software. The hypothesis test used was the superiority test, predicting that DEX was superior to SOC. All analyses were performed by two authors (MMGM and BA) and reviewed by a third author (BK). Pandharipa et al included 63 septic shock patients randomized into the lorazepam group (32 patients) or DEX group (31 patients), with 39 control patients without sepsis.9 We only included the 63 septic patient in the meta-analysis and pooled the outcome for the DEX group vs the Propofol group. We did not include the control patient group without sepsis. Also, we performed a sensitivity analysis for 28-day mortality and ICU LOS by omitting one study at a time to test the stability of the pooled results. The assessment of publication bias using the funnel plot is not reliable for the analysis of <10 studies, as described by Egger et al.10 Therefore, in the present meta-analysis, we could not examine the possibility of publication bias.

RESULTS

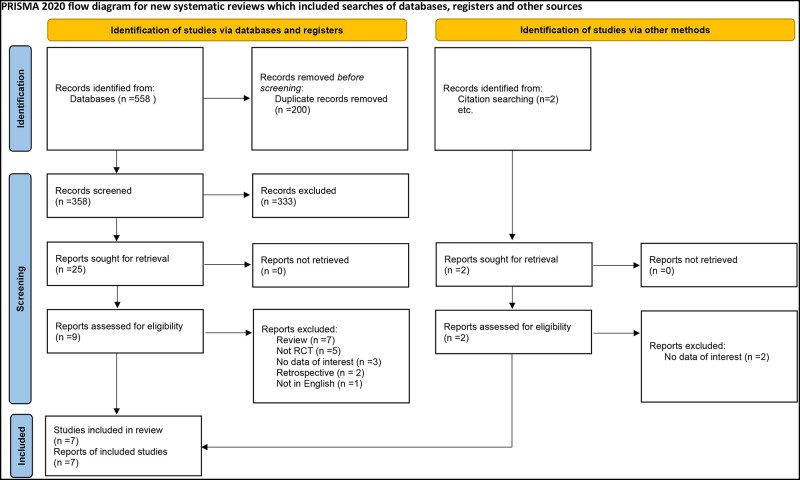

We identified 558 relevant citations. After removing the duplicates and screening and reviewing the remaining citations, seven articles9,11–16 were included in our systematic review for a grand total of 1049 patients. The process of inclusion and exclusion is detailed in the PRISMA flow diagram (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

PRISMA 2020 flow diagram for systematic reviews including the searches of databases, registers, and other methods.

Table 1 summarizes each selected study. One RCT included surgical patients with sepsis.15 The year of publication ranged from 2009 to 2021 for the included studies. Two RCTs were double-blinded.9,13 For all included RCTs, the pooled mean and SDs of each characteristic were as follows: age, 59.8 ± 19 years; male, 40.8% of participants; APACHE II score, 24 ± 10.7; SOFA score, 7.8 ± 3.8; Richmond agitation sedation score, −2.5 ± 1.5; MAP, 71 ± 11 mm Hg; and heart rate, 103 ± 13 beats per minute. The pooled mean and SD for the laboratory workup included lactate, 2.9 ± 2.2 mmol/L, and creatinine, 1.5 ± 1.0 mg/dL. The patient demographics and baseline characteristics are presented in Table 2.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the included studies

| Author, year | Length of study/country | Study design | Sample size | (n) Dexmedetomidine group and dose | (n) Control group and dose | Sedation level targets |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tasdogan et al, 200915 | 2007 / Turkey | Open-label | 40 | (20) LD: 1 μg/kg over 10 min. MD: 0.2–2.5 μg/kg/h over 24 h. | (20) Propofol: LD: 1 mg/kg over 15 min. MD: 1–3 mg/kg/h over 24 h. | < −2 |

| Memis et al, 200911 | 2009 / Turkey | Open-label | 40 | (20) LD: IV 1 μg/kg over 10 min. MD: 0.2–2.5 μg/kg/h over 24 h. | (20) Propofol: LD: IV 1 mg/kg over 15 min. MD: 1–3 mg/kg/h over 24 h. | < −2 |

| Pandharipa et al, 20109 | 2004–2006 / USA | Double-blind | 63 | (31) 1 mL/h (0.15 μg/kg/h) to a maximum of 10 mL/h (1.5 μg/kg/h). | (32) Lorazepam: LD 1 mL/h to a maximum of 10 mL/h. | −2 to −4 |

| Kawazoe et al, 201716 | 2013–2016 / Japan | Open-label | 201 | (100) Titrated 0.1 ∼ 0.7 μg/kg/h. | (101) Propofol: Titrated 0 ∼ 3mg/kg/h. Midazolam: Titrated 0 ∼ 0.15 mg/kg/h. | 0 to −2 |

| Cioccari et al, 202012 | 2013–2018 / Australia and Switzerland | Open-label | 83 | (44) No LD. Rate: 1.0 mcg/kg/h (varied between 0 and 1.5 mcg/kg/h). | (39) Usual care: midazolam (1–8 mg/h), propofol (50–200 mg/h), or both. | −2 to 1 |

| Liu et al, 202014 | 2014–2016 / China | Open-label | 200 | (100) LD: 1 μg/kg followed by a continuous IV infusion for 5 d. | (100) Propofol: LD:1 mg/kg. MD: IV infusion for 5 d. | −2 to 0 |

| Hughes et al, 202113 | 2013–2018 / USA | Double-blind | 422 | (214) 0.15 to 1.5 μg/kg of actual body weight per hour. | (208) Propofol: 5 to 50 μg/kg of actual body weight per minute. | 0 to −2 |

DEX indicates dexmedetomidine; LD, loading dose; MD, maintenance dose.

Table 2.

Patients’ demographic and baseline characteristics

| Author, year | Group | Mean age (years) (IQR) | Male sex (n) | APACHE II score: mean (IQR) | SOFA score: median (IQR) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tasdogan et al, 200915 | Propofol (n = 20) | 50 (19–74) | 11 | 18 (14–22) | 4 (1.5–6.5) |

| DEX (n = 20) | 58 (21–78) | 14 | 19 (14–24) | 4.2 (2.4–6) | |

| Memis et al, 200911 | Propofol (n = 20) | 54 (25–78) | 13 | 20 (12–28) | 4 (1.1–6.9) |

| DEX (n = 20) | 60 (31–80) | 14 | 22 (17–27) | 4.5 (1.7–7.3) | |

| Pandharipa et al, 20109 | DEX (n = 31) | 60 (46–65) | 18 | 30 (26–34) | 10 (9–13) |

| Lorazepam (n = 32) | 58 (44–66) | 13 | 29 (24–32) | 9 (8–12) | |

| Kawazoe et al, 201716 | DEX (n = 100) | 68 (53.1–82.9) | 63 | 23 (18–29) | 8 (6–11) |

| Control (n = 101) | 69 (55.4–82.6) | 64 | 22 (16–29.5) | 9 (5–11) | |

| Cioccari et al, 202012 | DEX (n = 44) | 67.7 (55.3–80.1) | 29 | 24.9 (18.2–31.6) | NA |

| Usual care (n = 39) | 62.9 (46.1–79.7) | 28 | 25.3 (18.3–32.3) | NA | |

| Liu et al, 202014 | Propofol (n = 100) | 54 (35–71) | 58 | 29 (22–36) | 11 (8–12) |

| DEX (n = 100) | 57 (31–66) | 57 | 29 (26–37) | 10 (8–13) | |

| Hughes et al, 202113 | DEX (n = 214) | 59 (48–68) | 121 | 27 (21–32) | 10 (8–13) |

| Propofol (n = 208) | 60 (50–68) | 120 | 27 (22–32) | 10 (8–12) |

APACHE indicates Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation; DEX, dexmedetomidine; IQR, interquartile range; NA, not applicable; SOFA, Sequential Organ Failure Assessment; usual care, likely to receive midazolam, propofol, or both.

Figure 2 presents the risk of bias. This systematic review included only RCTs. Random sequence generation was low in four studies and with an unclear risk of bias in three studies. Allocation concealment had a low risk of bias in three studies and an unclear risk of bias in two studies. Blinding of the participant had a low risk of bias in two studies. Blinding of outcome assessment had a low risk of bias in two studies. Only one study had a high risk of bias in incomplete outcome data and selective reporting. Other biases were all low risk.

Figure 2.

(a) Risk of bias summary: review authors’ judgments about each risk of bias item for each included study. (b) Risk of bias graph: review authors’ judgments about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies. The items are scored +, low risk; –, high risk; ?, unclear risk of bias.

There was no difference between groups with regard to 28-day mortality (RR = 0.76; 95% CI [0.51, 1.14]; P = 0.19) (Supplemental Figure S1). Following the omission of Liu et al, DEX demonstrated a reduced 28-day mortality compared to SOC (RR = 0.61; 95% CI [0.40, 0.92]; P = 0.02) (Supplemental Figure S2). There was no difference between groups with regards to 90-day mortality (RR = 0.94; 95% CI [0.75, 1.18]; P = 0.60) and ICU LOS (WMD = −0.85; 95% CI [−2.60, 0.90]; P = 0.34) (Supplemental Figures S3 and S4).

There were no significant differences with regards to mean delirium-free days (WMD = 1.38; 95% CI [−1.95, 4.70]; P = 0.42), ventilator-free days (WMD = 1.68; 95% CI [−1.48, 4.84]; P = 0.30), changes in heart rate (WMD = −3.75; 95% CI [−8.19, 0.68]; P = 0.10), and changes in MAP (WMD = −0.97; 95% CI [−2.07, 0.12]; P = 0.08). All meta-analysis results are summarized in Table 3.

Table 3.

Meta‐analysis for the impact of dexmedetomidine on the different variables

| Variable | Participants (dexmedetomidine /standard of care) | Trials | Quantitative data synthesis |

Heterogeneity analysis |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RR or MD | 95% CI | Z value | P value | I2 (%) | P value | |||

| Primary endpoints | ||||||||

| 28-day mortality | 269/270 | 5 | RR 0.76 | [0.51, 1.14] | 1.31 | 0.19 | 42 | 0.14 |

| • Omitting Tasdogan et al, 2009 | 91/107 | 4 | 0.76 | [0.49, 1.18] | 1.22 | 0.22 | 54 | 0.09 |

| • Omitting Pandharipa et al, 2010 | 87/96 | 4 | 0.96 | [0.79, 1.17] | 0.39 | 0.70 | 0 | 0.40 |

| • Omitting Memis et al, 2009 | 89/105 | 4 | 0.74 | [0.46, 1.19] | 1.24 | 0.21 | 56 | 0.08 |

| • Omitting Liu et al, 2020 | 28/47 | 4 | 0.61 | [0.40, 0.92] | 2.34 | 0.02 | 0 | 0.75 |

| • Omitting Kawazoe et al, 2017 | 73/81 | 4 | 0.75 | [0.42, 1.34] | 0.98 | 0.33 | 41 | 0.17 |

| 90-day mortality | 258/247 | 2 | RR 0.94 | [0.75, 1.18] | 0.52 | 0.60 | 0 | 0.65 |

| ICU LOS | 313/309 | 6 | MD −0.85 | [−2.60, 0.90] | 0.95 | 0.34 | 86 | 0.00001 |

| • Omitting Cioccari et al, 2020 | 269/270 | 5 | −0.80 | [−3.08, 1.47] | 0.69 | 0.49 | 83 | 0.0001 |

| • Omitting Kawazoe et al, 2017 | 213/208 | 5 | −0.76 | [−2.84, 1.33] | 0.71 | 0.48 | 88 | 0.00001 |

| • Omitting Liu et al, 2020 | 213/209 | 5 | −0.44 | [−1.14, 0.25] | 1.25 | 0.21 | 0 | 0.67 |

| • Omitting Memis et al, 2009 | 293/289 | 5 | −1.13 | [−2.94, 0.68] | 1.23 | 0.22 | 88 | 0.00001 |

| • Omitting Pandharipa et al, 2010 | 282/277 | 5 | −0.97 | [−2.79, 0.84] | 1.05 | 0.29 | 88 | 0.00001 |

| • Omitting Tasdogan et al, 2009 | 295/292 | 5 | −1.11 | [−3.08, 0.86] | 1.11 | 0.27 | 86 | 0.00001 |

| Secondary endpoints | ||||||||

| Delirium-free days | 245/240 | 2 | MD 1.38 | [−1.95, 4.70] | 0.81 | 0.42 | 91 | 0.0007 |

| Ventilator-free days | 345/341 | 3 | MD 1.68 | [−1.48, 4.84] | 1.04 | 0.30 | 63 | 0.07 |

| Change in HR | 95/91 | 3 | MD −3.75 | [−8.19, 0.68] | 1.66 | 0.10 | 28 | 0.25 |

| Change in MAP | 82/77 | 2 | MD −0.97 | [−2.07, 0.12] | 1.74 | 0.08 | 0 | 0.88 |

CI indicates confidence interval; HR, heart rate; ICU, intensive care unit; LOS, length of stay; MAP, mean arterial pressure; MD, mean difference; RR, risk ratio.

DISCUSSION

In this updated meta-analysis of RCTs, which included 1049 participants, we compared DEX to SOC (propofol, benzodiazepines, fentanyl) for sedation in critically ill patients with sepsis. There were no differences between DEX and SOC with regards to 28-day mortality, 90-day mortality, ICU LOS, delirium-free days, ventilator-free days, changes in heart rate, and changes in MAP. After omitting Liu et al from the analysis, DEX demonstrated a reduced 28-day mortality when compared to SOC. Further studies are needed to confirm this result.

A previous meta-analysis by Xia et al17 assessed the influence of DEX compared to propofol for adults admitted to the ICU and reported that utilizing DEX decreased ICU LOS (-0.81 days; 95% CI [−1.48, −0.15]) compared to propofol. However, the study analyzed critically ill patients, including both septic and nonseptic patients, and the clinical benefits observed in their analysis were mainly driven by the nonseptic patients. In the present meta-analysis, we included only RCTs specific to critically ill, septic patients. Our results demonstrated that DEX did not decrease the ICU LOS compared to SOC sedation, including propofol, for this population. The included trials in Xia et al had different baseline characteristics and clinical presentations for the patients, which led to heterogeneity in the outcomes. Also, the majority of the included trials had extensive exclusion criteria including hemodynamic instability, hepatic or renal insufficiency, and obesity, limiting the applicability of the results to critically ill patients. DEX may exhibit a protective role against organ damage (blood vessels, kidneys, heart, and brain).18 Taken together, these factors account for the differences in the outcomes reported in our study and the study by Xia et al.17

Zhang and his colleagues conducted a similar meta-analysis reviewing the efficacy of DEX on treating patients with sepsis.19 They reported a statistically significant decrease in 28-day mortality (RR = 0.49; 95% CI [0.35, 0.69]; P = 0.000) and ICU mortality (RR = 0.44; 95% CI [0.23, 0.84]; P = 0.013) with DEX compared to the control group. The hospital LOS and duration of mechanical ventilation were not significantly different (WMD = −0.05; 95% CI [−0.59, 0.48]; P = 0.84; and WMD = 1.05; 95% CI [−0.27, 2.37]; P = 0.392, respectively). Of note, their control group included saline or placebo, not SOC sedation protocols, as utilized in our study. This changes the effect size. They also included three RCTs—Lei et al 2019; Ren et al 2017; and Zhou et al 2017—that are no longer available in the database, and the links provided in the references were outdated and nonfunctioning. A P value of <0.001 was reported in their study for 28-day mortality, which was unexplainable statistically. The aforementioned factors that limit the validity of their meta-analysis explain the differences in the results of our analysis.

Ventilator-free days are defined as the number of days the patient is independent of mechanical ventilation and remains living.20 A more recent meta-analysis by Chen et al assessed the effect of DEX compared to SOC in septic patients.21 They included two trials9,16 and reported significant differences in ventilator-free days (WMD = 3.57; 95% CI [0.26, 6.89]; P = 0.03). We included a recently published RCT by Hughes et al,13 and the results of our meta-analysis demonstrated no significant difference between DEX and SOC. Chen et al also reported that DEX decreased 28-day mortality (RR = 0.61; 95% CI [0.49, 0.94]; P = 0.02).21 They included four trials in their analysis.9,15,16,22 Our updated meta-analysis results were contrary. We included five RCTs,9,11,14–16 and the result did not show any significant difference between DEX and SOC in 28-day mortality (RR = 0.76; 95% CI [0.51, 1.14]; P = 0.19). We added the study by Hughes et al13 that included 432 patients, and it comprised 51.5% of the weighted contribution for the outcome of ventilator-free days. Similarly, for the 28-day mortality outcome, we added Liu et al,14 which accounted for 46.6% of the weighted contribution. These considerations explain the difference in results between our study and that of Chen et al.21

Zhou et al compared DEX to midazolam and reported that there was no significant difference between them with respect to the occurrence of hypotension (odds ratio = 0.88; 95% CI [0.70, 1.10]; P = 0.26; P value for heterogeneity = 0.99; I2 = 0%) and mortality rates (odds ratio = 0.96; 95% CI [0.74, 1.25]; P = 0.77; P value for heterogeneity = 0.99; I2 = 0%).23 They did ultimately recommend DEX over midazolam, as DEX had a better clinical effect and safety profile in their study. The results of Zhou et al were similar to those of our meta-analysis. We compared DEX to SOC, including propofol, benzodiazepines, and fentanyl. We found that DEX did not affect MAP (WMD = − 0.97; 95% CI [−2.07, 0.12]; P = 0.08) and it is a safe option in patients with hemodynamic instability.

Our study had several strengths but also some limitations. First, some of the essential outcomes were derived from a small number of RCTs, and as a result, more RCTs are needed before making clinical recommendations based on these studies. Second, different Richmond agitation sedation scores, APACHE II scores, and SOFA scores were used among the trials. This could lead to heterogeneity in the clinical effects of each respective agent and, subsequently, influence the outcomes. Third, we compared DEX vs SOC sedation, including propofol, midazolam, fentanyl, or combinations of these agents. We did not compare DEX to each drug individually. Finally, we included studies from 2009 to 2021. The definition of sepsis has evolved during this timeframe,24 and there were no consistent criteria for sepsis or septic shock, which may lead to clinical heterogeneity.

In conclusion, the result of our meta-analysis suggests that DEX is not associated with reduced 28-day mortality, 90-day mortality, ICU LOS, delirium-free days, ventilator-free days, changes in heart rate, and changes in MAP when compared to SOC in critically ill, septic patients.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Diane Gardner, MLIS, AHIP, for editing and proofreading this article.

References

- 1.Fleischmann C, Scherag A, Adhikari NK, et al. Assessment of global incidence and mortality of hospital-treated sepsis. Current estimates and limitations. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2016;193(3):259–272. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201504-0781OC [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yuki K. The immunomodulatory mechanism of dexmedetomidine. Int Immunopharmacol. 2021;97:107709. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2021.107709 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Giovannitti JA Jr, Thoms SM, Crawford JJ.. Alpha-2 adrenergic receptor agonists: a review of current clinical applications. Anesth Prog. 2015;62(1):31–39. doi: 10.2344/0003-3006-62.1.31 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Xie Y, Guo C, Liu Y, Shi L, Yu J.. Dexmedetomidine activates the PI3K/Akt pathway to inhibit hepatocyte apoptosis in rats with obstructive jaundice. Exp Ther Med. 2019;18(6):4461–4466. doi: 10.3892/etm.2019.8085 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhai M, Liu C, Li Y, et al. Dexmedetomidine inhibits neuronal apoptosis by inducing Sigma-1 receptor signaling in cerebral ischemia-reperfusion injury. Aging (Albany NY). 2019;11(21):9556–9568. doi: 10.18632/aging.102404 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Syst Rev. 2021;10(1):89. doi: 10.1186/s13643-021-01626-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Page MJ, Moher D, Bossuyt PM, et al. PRISMA 2020 explanation and elaboration: updated guidance and exemplars for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;372(160):n160. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n160 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Higgins JP, Altman DG, Gøtzsche PC, et al. The Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ. 2011;343(2):d5928–d5928. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d5928 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pandharipande PP, Sanders RD, Girard TD, et al. Effect of dexmedetomidine versus lorazepam on outcome in patients with sepsis: an a priori-designed analysis of the MENDS randomized controlled trial. Crit Care. 2010;14(2):R38. doi: 10.1186/cc8916 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Egger M, Davey Smith G, Schneider M, Minder C.. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ. 1997;315(7109):629–634. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7109.629 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Memiş D, Kargi M, Sut N.. Effects of propofol and dexmedetomidine on indocyanine green elimination assessed with LIMON to patients with early septic shock: a pilot study. J Crit Care. 2009;24(4):603–608. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2008.10.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cioccari L, Luethi N, Bailey M, et al. The effect of dexmedetomidine on vasopressor requirements in patients with septic shock: a subgroup analysis of the Sedation Practice in Intensive Care Evaluation [SPICE III] Trial. Crit Care. 2020;24(1):441;. doi: 10.1186/s13054-020-03115-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hughes CG, Mailloux PT, Devlin JW, et al. Dexmedetomidine or propofol for sedation in mechanically ventilated adults with sepsis. N Engl J Med. 2021;384(15):1424–1436. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2024922 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liu J, Shi K, Hong J, et al. Dexmedetomidine protects against acute kidney injury in patients with septic shock. Ann Palliat Med. 2020;9(2):224–230. doi: 10.21037/apm.2020.02.08 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tasdogan M, Memis D, Sut N, Yuksel M.. Results of a pilot study on the effects of propofol and dexmedetomidine on inflammatory responses and intraabdominal pressure in severe sepsis. J Clin Anesth. 2009;21(6):394–400. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinane.2008.10.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kawazoe Y, Miyamoto K, Morimoto T, et al. Effect of dexmedetomidine on mortality and ventilator-free days in patients requiring mechanical ventilation with sepsis: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2017;317(13):1321–1328. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.2088 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Xia ZQ, Chen SQ, Yao X, Xie CB, Wen SH, Liu KX.. Clinical benefits of dexmedetomidine versus propofol in adult intensive care unit patients: a meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. J Surg Res. 2013;185(2):833–843. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2013.06.062 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dardalas I, Stamoula E, Rigopoulos P, et al. Dexmedetomidine effects in different experimental sepsis in vivo models. Eur J Pharmacol. 2019;856:172401. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2019.05.030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhang WQ, Xu P, Zhan XH, Zheng P, Yang W.. Efficacy of dexmedetomidine for treatment of patients with sepsis: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Medicine (Baltimore). 2019;98(18):e15469. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000015469 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yehya N, Harhay MO, Curley MAQ, Schoenfeld DA, Reeder RW.. Reappraisal of ventilator-free days in critical care research. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2019;200(7):828–836. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201810-2050CP [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chen P, Jiang J, Zhang Y, et al. Effect of dexmedetomidine on duration of mechanical ventilation in septic patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Pulm Med. 2020;20(1):42. doi: 10.1186/s12890-020-1065-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Guo F, Wang Q, Yan CY, Huang HY, Yu X, Tu LY.. Clinical application of different sedation regimen in patients with septic shock. Zhonghua Yi Xue Za Zhi. 2016;96(22):1758–1761. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.issn.0376-2491.2016.22.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhou WJ, Liu M, Fan XP.. Differences in efficacy and safety of midazolam vs. dexmedetomidine in critically ill patients: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trial. Exp Ther Med. 2020;21(2):156. doi: 10.3892/etm.2020.9297 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gyawali B, Ramakrishna K, Dhamoon AS.. Sepsis: the evolution in definition, pathophysiology, and management. SAGE Open Med. 2019;7:2050312119835043. doi: 10.1177/2050312119835043 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.