Abstract

The mural of the Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh contains a unique symbol of an eye placed in the palm of a hand. The symbol is known by many names—the Eye of Providence, the All-Seeing Eye, and the Eye of Horus—and has been a central symbol of religious and medical organizations across many cultures, including Egyptian, British, Indian, and American. The symbol is also representative of the Hamsa. In Arabic cultures, the Hamsa is a palm-shaped amulet that is popular in jewelry and wall hangings. It is a symbol of protection against evil. Both symbols have an important history with regards to medical practice. This paper examines the history of the Eye of Providence and the Hamsa with regard to their use and meaning within the medical profession.

Keywords: All-Seeing eye, Eye of Providence, Hamsa, medicine, Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh, Royal College of Surgeons

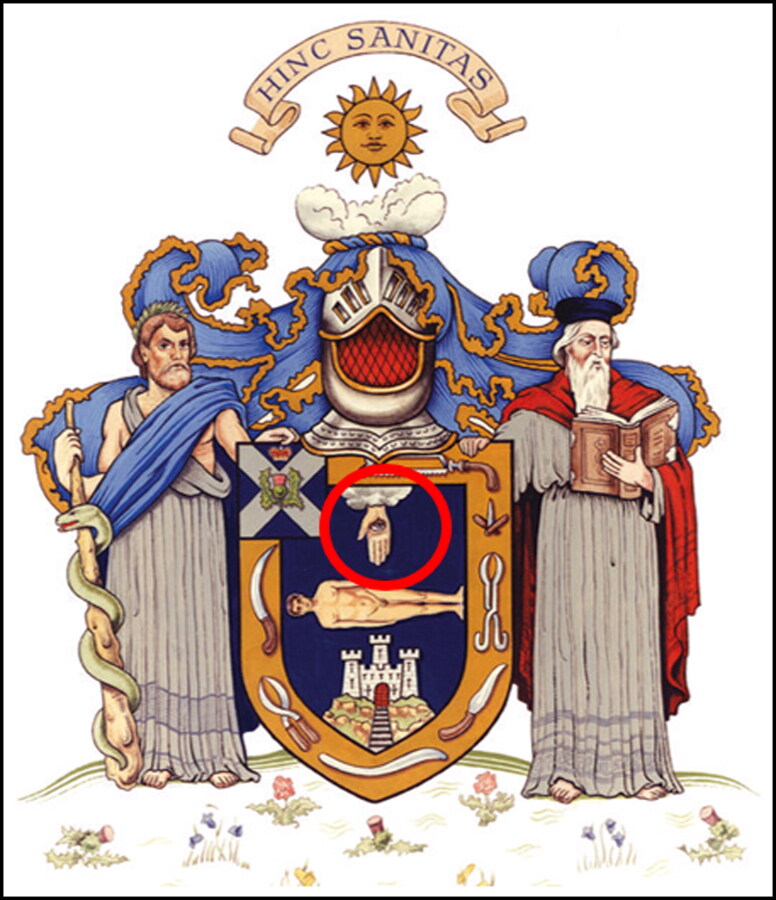

The Royal College of Surgeons has been around for centuries. Its predecessor, the Company of Barber-Surgeons, was founded in the 1540s when the Company of Barbers and the Fellowship of Surgeons merged to become the Company of Barber-Surgeons through the direction of King Henry VIII. The Royal College of Surgeons later split into several branches. One branch, the Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh, began as a craft guild,1 and its mural reflects those origins (Figure 1). Of particular interest, the mural contains a unique symbol of an eye placed in the palm of a hand. The symbol is known by many names—the Eye of Providence, the All-Seeing Eye, Hamsa, and the Eye of Horus.

Figure 1.

Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh mural showing the Eye of Providence on the palm of the hand.

THE EYE OF PROVIDENCE AND THE HAMSA

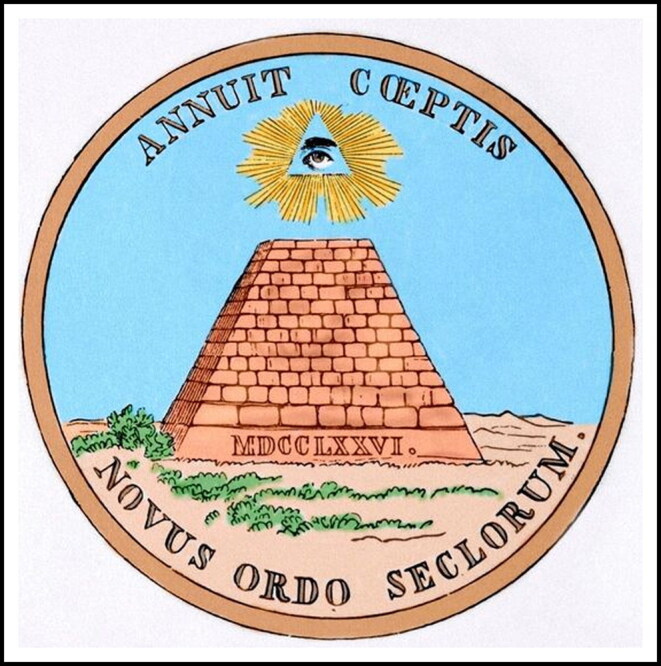

The Eye of Providence represents divine providence, whereby the eye of God watches over humanity.2,3 This symbol can be traced back to the Greek classics, as evidenced by comparable emblems and references of 17th-century authors, followed by references in alchemy, astrology, kabala, Rosicrucianism, and Freemasonry.2,3 This emblem, which depicts a benign deity’s protecting eye, is also found on the back of the US $1 bill. The Eye of Providence was included as part of the iconography on the reverse side of the US Great Seal in 1782 (Figure 2). As Albert Potts described:

Figure 2.

The Eye of Providence on the US Seal.

One is entitled to speculate why the committee on the Great Seal did not use the word for our symbol which had been universal in Europe for a hundred years: the Eye of God. It is at least conceivable that the Eye of Providence represents a compromise arrived at between the Deist philosophy of Franklin and Jefferson which minimized interference with the laws of nature, and the religious orthodoxy of the majority of the colonists. However this may be, the Eye of Providence, whose history has never been recorded, has a history for all that. It stands in the pages of the classic philosophers, the astrologers and the alchemists and is their legacy to the United States of America.3

As Albert Mackey alluded to, the open eye in the Eye of Providence was selected as the symbol of watchfulness, and the eye of God as the symbol of divine watchfulness and care of the universe.4 As Mackey wrote:

Our French Brethren place this letter YOD in the centre of the Blazing Star. And in the old Lectures, our ancient English Brethren said, The Blazing Star or Glory in the center refers us to that grand luminary, the Sun, which enlightens the earth, and by its genial influence dispenses blessings to mankind. They called it also in the same lectures, an emblem of PRUDENCE. The word Prudentia means, in its original and fullest signification, Foresight; and, accordingly, the Blazing Star has been regarded as an emblem of Omniscience, or the All-seeing Eye, which to the Egyptian Initiates was the emblem of Osiris, the Creator. With the YOD in the center, it has the kabalistic meaning of the Divine Energy, manifested as Light, creating the Universe.4

The Hamsa hand is a five-digited open right hand (Figure 3). Its actual origin is uncertain, although its use in the Middle East predates Islam and Judaism. Khamsa (five in Arabic), hamesh (five in Hebrew), hamesh hand, and chamsa are all names for the Hamsa hand.5 Stopping offensives can be done by raising a hand with the palm visible and spread fingers. The splayed digits of the Hamsa hand can be used to ward off aggressors and to blind evil. To bring good luck, the digits of the Hamsa might be closed together. The digits may be pointing upwards or downwards.5 The Hamsa hand’s palm may have an eye to repel malevolent gazes.

Figure 3.

The Hamsa.

The Hamsa hand is also known as the hand of Fatima Zahra, the Prophet Mohammed’s daughter, in Islam. In Islam, the number 5 is associated with the five pillars of Islam and the five daily prayers. The number 5 is associated with the Prophet’s family of five holy people, according to Shiites. It’s known among Christians in the Levant as Mary’s hand. The Hamsa hand is a Jewish emblem for the Hand of Miriam, Moses’ and Aaron’s sister.5 For Jews, the number 5 (hamesh) may signify the five books of the Torah. In the Buddha’s teaching and protective gesture, the picture of an open right hand may be observed. The International Federation of Societies for Hand Surgery chose an open right hand as its emblem because it is a global symbol that represents protection, blessing, health, happiness, and wealth in all faiths.5

The Hamsa symbolizes the three main monotheistic faiths; the five fingers symbolize the Five Books of Moses, which inspire the religious. The three fingers in the center of the Hamsa are symbolic of important virtues for moral behavior: the three primary virtues of wisdom, strength, and beauty; the three grand principles of brotherly love, relief, and truth; and the three great monotheistic religions. In contrast, the five fingers represent faith, tolerance, charity, strength, and love.

The concept of the All-Seeing Eye and the Hamsa fits very nicely with naive notions of objectivity. Both symbols see situations of circumstances as objective facts. Scientists’ efforts are focused at creating perspectives that are as near to the All-Seeing Eye’s view as feasible. With regards to medicine, the notion of objectivity lies at the heart of medical practice. For the ophthalmologists at the Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh, the Eye of Providence and the Hamsa held a special meaning toward the unique functions of the eye and the journey of medical practice to treat its various illnesses.

THE EYE OF PROVIDENCE AND HAMSA IN MEDICINE

Since the ancient Egyptians, the Eye of Providence, known as the Eye of Horus, represented the physicians’ fascination with the wondrous capacity of the eye to both reveal and color the world we see. The ancient Egyptians were pioneers in art and medicine.6 Documented papyrus, as well as the walls of many temples and tombs, bear witness to this. Ancient Egyptians used their creative talents and knowledge of anatomy with their strong belief in mythology to create the Eye of Horus. The relevance of the Eye of Horus is to recognize and respect the wisdom and foresight of an ancient culture in deciphering the complicated functioning of the human central nervous system.6

Fascination with the eye would continue for generations of physicians. The Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh wrote extensively on the importance and uniqueness of the eye. In the book written in 1859 for the Royal College of Physicians, Know Thyself, Jane Taylor wrote:

Seeing and hearing are obviously the most precious, as means of acquiring knowledge, and promoting mental improvement. The enjoyments furnished by the senses of seeing and hearing, take a far wider range, and are of a far nobler nature, than those of the other senses, which seem to be more directly useful to the body than to the mind…. How wise, good, and All-Seeing, must be the creator who made the eye, so perfect, so beautiful, and so wonderful! We should never neglect a proper care of the senses with which we are endowed; for a deprivation of any of them is one of the greatest misfortunes that can befall us.7

For Taylor, the eye represented the unity of the human nervous system in all its parts to produce the wonderful sensations and identity of human beings with regards to their relationship to the outside world. As Taylor emphasized near the beginning of her book,

The eye is not sight, because it is used in seeing, nor is the ear, hearing, but the organ of hearing. The brain likewise, is not the mind, but the organ of the mind, or the seat of the intellectual and reasoning faculties of man, such as thought, memory, hope, love, hatred, ambition, etc. In brute animals the brain is the organ of what is called instinct. Of what is the brain composed? Of matter which is subject to decay.7

Over time, the meaning of the Eye of Providence and the Hamsa has evolved to represent the rigors and challenges physicians face in treating ever more complex medical conditions while also remembering to maintain the humanity of their patients and themselves. This sentiment was explored by the poet Andrew Greig with the passing of his father, Donald Stewart Greig, who was an obstetrician and gynecologist at the Stirling Royal Infirmary and Airthrey Castle. Upon seeing the mural of the Royal College of Surgeons of Edinburgh, Andrew Greig was inspired to write the following poem on the symbol with respect to his father’s work and life.

My only talent lay in these.

My father rubbed his hands together,

stared as though their whorls held codes

of thirty years obstetric surgery.

It’s a manual craft –the rest’s just memory

and application. The hard art

lies in knowing when to stop….

I stare at the College coat of arms,

that eye wide-open in the palm,

hear his long-dead voice, see again

those skillful hands that now are ash;

working these words I feel him by me,

lighting up the branching pathways.

Impossible, of course, and yet it gives

me confidence. We need

to believe we are not working blind;

with his eye open in my mind

I open the notebook and proceed.8

For Andrew Greig, the mural’s Eye of Providence and Hamsa became a reminder of the dedication his father had for his many duties and responsibilities as a father and surgeon. The symbols embodied the intimate areas of life his father tread on a daily basis as he interacted with patients in their most vulnerable moments. Most of all, the poem showed the pride Greig’s father experienced in using his technical abilities as a physician to play a small role in the betterment of humanity. As Andrew Greig reflected on his poem:

He [Donald Stewart Greig] seldom talked about his work, other than to say he regarded himself as very fortunate in having never been bored a day in his working life. Because my father is long dead, it was emotional for me to walk round the College [Royal College of Surgeons of Edinburgh] in the certain knowledge he had been here. This was his world. I looked on portraits and photos of names he had mentioned with reverence and respect: Simpson, Lister, Wade, Bell. But the real moment of contact—and the opening of this poem—came when I asked about the meaning of the mysterious ‘Eye in the hand’ in the stained glass window. I recalled then my father saying his real talent wasn’t diagnostic or intellectual, it was in his hands, which were large, long-fingered, powerful, exact. He rubbed them together and said to me “It’s odd—at times I felt I could almost see through the skin.” So that’s it. The poem is a memoir of my father, a gesture of respect to him and his profession.9

CONCLUSION

We give symbols to the things we care about. Symbols not only allow us to readily connect with the object of our attention, but they also provide us with a tangible item to which we may attach our emotions. As shown with the Eye of Providence and the Hamsa, these symbols remind physicians that everything they do for patients relates back to their creator who oversees all that happens. The All-Seeing Eye can thus be seen as a metaphor of God shown in his omnipresence—his guarding and protecting nature—to which Solomon alludes in Proverbs. For physicians, the Eye of Providence and the Hamsa are two symbols that reflect their dedication toward perfecting their craft—a craft that aims for healing of the body as well as the soul.

References

- 1.Maynard A, Ayalew Y.. Performance management and the Royal Colleges of Medicine and surgery. J R Soc Med. 2007;100(7):306–308. doi: 10.1177/014107680710000710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Koenderink J. The all seeing eye? Perception. 2014;43(1):1–6. doi: 10.1068/p4301ed. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Potts AM. The eye of providence. Doc Ophthalmol. 1973;34(1):327–334. doi: 10.1007/BF00151819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mackey AG. The Symbolism of Freemasonry. London: Forgotten Books; 1882. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Afshar A, Ahmadi A.. The hand in art: Hamsa hand. J Hand Surg. 2013;38(4):779–780. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2012.12.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.ReFaey K, Quinones GC, Clifton W, Tripathi S, Quiñones-Hinojosa A.. The eye of horus: The connection between art, medicine, and mythology in ancient Egypt. Cureus. 2019;11(5):e4731. doi: 10.7759/cureus.4731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Taylor J. Know Thyself. London: Royal College of Surgeons; 1859. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Greig A. From the Royal College of Surgeons of Edinburgh. In: Morrison L, Gillies J, Newell A, Fraser L, eds. Tools of the Trade: Poems for New Doctors. Scottish Poetry Library: Edinburgh; 2014. https://www.scottishpoetrylibrary.org.uk/poem/royal-college-surgeons-edinburgh/ [Google Scholar]

- 9.Greig A. The eye in the hand. Scottish Poetry Library. https://www.scottishpoetrylibrary.org.uk/poem/eye-hand/. Accessed October 1, 2021.