ABSTRACT

Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) infection is associated with multiple malignancies, including pulmonary lymphoepithelioma-like carcinoma (pLELC), a particular subtype of primary lung cancer. However, the genomic characteristics of EBV related to pLELC remain unclear. Here, we obtained the whole-genome data set of EBV isolated from 78 pLELC patients and 37 healthy controls using EBV-captured sequencing. Compared with the reference genome (NC_007605), a total of 3,995 variations were detected across pLELC-derived EBV sequences, with the mutational hot spots located in latent genes. Combined with 180 published EBV sequences derived from healthy people in Southern China, we performed a genome-wide association study and identified 32 variations significantly related to pLELC (P < 2.56 × 10−05, Bonferroni correction), with the top signal of single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) coordinate T7327C (OR = 1.22, P = 2.39 × 10−15) locating in the origin of plasmid replication (OriP). The results of population structure analysis of EBV isolates in East Asian showed the EBV strains derived from pLELC were more similar to those from nasopharyngeal carcinoma (NPC) than other EBV-associated diseases. In addition, typical latency type-II infection were recognized for EBV of pLELC at both transcription and methylation levels. Taken together, we defined the global view of EBV genomic profiles in pLELC patients for the first time, providing new insights to deepening our understanding of this rare EBV-associated primary lung carcinoma.

IMPORTANCE Pulmonary lymphoepithelioma-like carcinoma (pLELC) is a rare, distinctive subtype of primary lung cancer closely associated with Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) infection. Here, we gave the first overview of pLELC-derived EBV at the level of genome, methylation and transcription. We obtained the EBV sequences data set from 78 primary pLELC patients, and revealed the sequences diversity across EBV genome and detected variability in known immune epitopes. Genome-wide association analysis combining 217 healthy controls identifies significant variations related to the risk of pLELC. Meanwhile, we characterized the integration landscapes of EBV at the genome-wide level. These results provided new insight for understanding EBV’s role in pLELC tumorigenesis.

KEYWORDS: Epstein-Barr virus, pulmonary lymphoepithelioma-like carcinoma, genome sequencing, genetic variation, DNA integration

INTRODUCTION

Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) is a widely distributed human herpesvirus infecting more than 95% of the worldwide population and causing 1.8% of all malignancy deaths. It has been found to be associated with a variety of malignancies, including nasopharyngeal carcinoma (NPC), EBV-associated gastric carcinoma (EBVaGC), Burkitt lymphoma (BL), Hodgkin lymphoma (HL), and NK/T cell lymphoma (NKTCL) (1). EBV can also be detected by EBV-encoded RNA (EBER) staining or quantitative PCR (qPCR) in the tumor tissues of patients with pulmonary lymphoepithelioma-like carcinoma (pLELC), which is a rare subtype of primary non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) with morphology similar to undifferentiated NPC (2–5). However, the role of EBV in the tumorigenesis of pLELC is unclear.

Geographic distribution and disease types may be associated with specific sequences and variations of the infected EBV (6). Previous studies have reported the genetic variations of EBV play an important role in several EBV-associated tumors (7). For example, NPC-derived LMP1 is less cytostatic than the LMP1 of B95-8 due to the variations in the transmembrane domain sequence (8). And the natural variations of the promoter regions of immediately early genes BZLF1 and BRLF1 are helpful for variations-carried EBV to transform to the lytic cycle, a possible EBV-induced carcinogenic process (9, 10). In addition, recent studies have identified NPC-related EBV subtypes based on the variations of EBV genomes, with significantly higher risk of NPC occurrence for population infected with the high-risk subtype of EBV than the low-risk subtype in southern China (11–13). However, the genomic characteristics of EBV in pLELC are still unknown. Moreover, a potential EBV carcinogenic mechanism, virus-host integration has been reported in NPC, EBVaGC, and EBV-positive lymphoma (14–16), but its role in pLELC remains unclear. Thus, identifying the molecular characteristics of infected EBV would contribute to understanding its potential role in the pathogenesis of pLELC and the development of therapeutic strategies.

In this study, to explore the role of EBV in pLELC carcinogenesis, we newly sequenced and assembled EBV genomes from 78 pLELC patients and 37 healthy controls. In combination with 180 reported EBV strains from healthy controls in Southern China, we conducted a genome-wide association study (GWAS) and identified 32 high-risk EBV variations for pLELC. We also characterized the human-EBV integrative features, methylation profiles, and infection statuses of pLELC-derived EBVs through comprehensive and systematic analyses. These findings depicted a multilayered molecular atlas of EBV in pLELC for the first time, providing new insights into the etiology and pathogenesis of pLELC.

RESULTS

Genomic profiles of EBV derived from pLELC.

We sequenced EBV genomes isolated from tumor tissues of 78 pLELC patients and saliva of 42 healthy control in southern China. Using NC_007605 EBV strain (EBV-wt) as reference genome, the mean sequencing depth of all isolates was 5,596×, and for each isolate, over 95% genome was covered by qualified reads (Table S1). Five healthy controls (11.9%) were excluded as multiple infections due to the heterogenous loci over 10%. Finally, we assembled a new EBV genomic data set of 78 pLELC patients and 37 healthy controls.

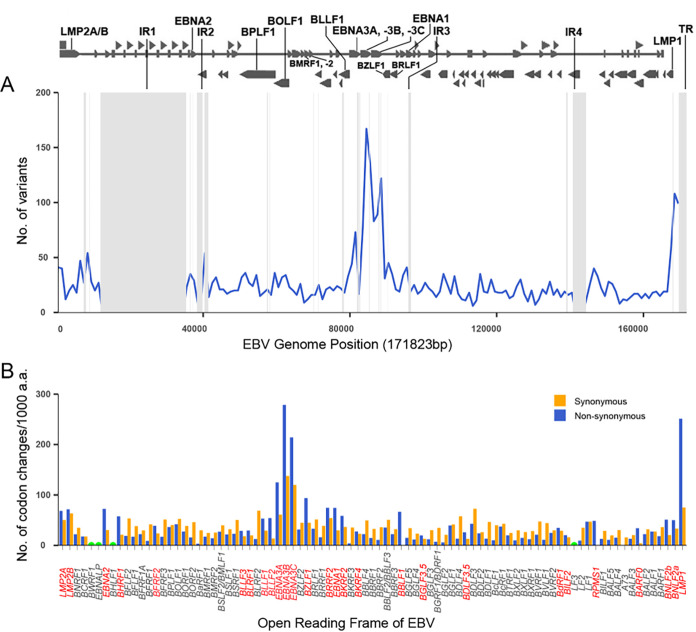

Compared with EBV-wt, a total of 3,995 variations (3,844 SNPs and 151 Indels) were identified from EBV strains derived from pLELC, with the number ranging from 983 to 1,516 for each sample (Table S2 and Table S3). By analyzing the variations of EBNA2 and EBNA3s, we found the majority of pLELC patients were infected with EBV strains of type I, with only one patient (1/78, 1.28%) infected by the intertype EBV with type I EBNA2 and type II EBNA3s (17). The variations were not randomly distributed across EBV genome, with mutation hot spots tending to the regions of latent genes LMPs and EBNAs (Fig. 1A). The highest frequency of codon variations existed in the genes EBNA3B, EBNA3C, and LMP1, with the variation frequency of 416, 334, and 326 per 1,000 amino acids, respectively (Fig. 1B). We also found the latent-associated genes and some lytic genes (including BZLF1, BRRF2, etc.) had a high ratio of nonsynonymous to synonymous (Fig. 1B), suggesting these genes might undergo selection pressures in infection (6).

FIG 1.

Variations across all EBV genomes derived from pLELC. (A) Variations frequency across 78 EBV genomes derived from pLELC. The line graph is plotted across the genome showing the total number of variants in a sliding 1,000-nt window. Repeat regions are masked out in gray. (B) Total number of codon changes per gene across 78 EBV genome. Codon changes per 1,000 amino acids are calculated to normalize for gene length, and data are provided for the nonrepetitive region only. The gene names in red indicate that the genes have more nonsynonymous variants than the synonymous variants. Gene BWRF1, EBNA-LP, BHLF1, and LF3 are incompletely assembled due to repeat regions and are not determined.

Genome-wide association study identified variations in EBV associated with pLELC.

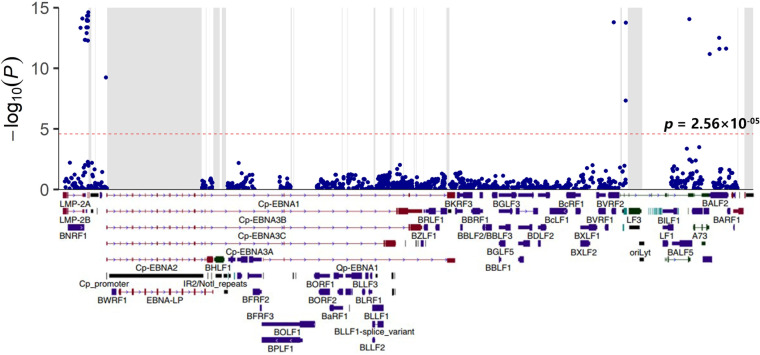

To explore the impact of EBV genomic variations on the risk of pLELC, a systematic GWAS of EBV genomes was performed using EBV sequences identified in this study (78 pLELC patients and 37 healthy controls) and 180 EBV sequences of healthy controls (after ruling out nine multiply infected people) from data sets SRP152584 (11) and PRJNA522388 (12). After adjusting for sex and age with linear mixed model, a total of 32 variations associated with pLELC risk were detected across the EBV genome with the P value cut-off 2.56 × 10−05 (Bonferroni correction; Fig. 2, Table 1 and Table S4). Twenty-two of these pLELC-associated variations were around EBERs (coordinates 5850–7327), with the top signal of SNP coordinate T7327C (OR = 1.22, P = 2.39 × 10−15) locating in the origin of plasmid replication (OriP). In addition, we found four SNPs could induce non-synonymous variations. Among them, two SNPs (coordinates C163364T and G163464A) caused amino acid changes in the DNA-binding protein BALF2 (S1093G and V317M), one SNP (coordinate A5399G) altered the 1,222nd amino acid residue of tegument protein BNRF1 (V1222I) and another SNP (coordinate A137316C) resulted in the replacement of H560P in virus serine protease BVRF2. We found significant linkage disequilibrium existed among all these pLELC-risk variations, with R2 greater than 0.6 (Fig. S1).

FIG 2.

GWAS of EBV variants in 78 pLELC patients and 217 healthy carriers. The top panel is a Manhattan plot of genome-wide P values from the association analysis using linear mixed model (LMM) adjusted for sex and age. The −log10-transformed P values are presented according to their positions in the EBV genome. The red dotted line shows genome-wide significance P value of 2.56 × 10−05. Repeat regions are masked out in gray. The bottom panel is the schematic of EBV genes.

TABLE 1.

The most significant pLELC-associated variations identified in the GWAS

| Position | Risk allele | Non-risk allele | % in pLELCa | % in controlb | Or (95% CI) | P-valuec | Annotation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5399 | A | G | 0.94 | 0.45 | 1.20 (1.15, 1.26) | 4.65 × 10−14 | BNRF1(Val1222Ile) |

| 5850 | T | A | 0.95 | 0.45 | 1.21 (1.16, 1.27) | 7.97 × 10−15 | BNRF1 (3′ UTR) |

| 6484 | T | C | 0.92 | 0.45 | 1.20 (1.14, 1.25) | 4.60 × 10−13 | Between BNRF1 and EBER1 |

| 6584 | G | A | 0.92 | 0.45 | 1.20 (1.14, 1.25) | 4.60 × 10−13 | Between BNRF1 and EBER1 |

| 6866 | A | G | 0.94 | 0.45 | 1.20 (1.15, 1.26) | 4.21 × 10−14 | Between EBER1 and EBER2 |

| 6884 | G | A | 0.94 | 0.45 | 1.20 (1.15, 1.26) | 4.21 × 10−14 | Between EBER1 and EBER2 |

| 6886 | T | G | 0.94 | 0.45 | 1.20 (1.15, 1.26) | 4.21 × 10−14 | Between EBER1 and EBER2 |

| 6911 | A | G | 0.94 | 0.45 | 1.20 (1.15, 1.26) | 1.26 × 10−13 | Between EBER1 and EBER2 |

| 6944 | G | A | 0.95 | 0.45 | 1.21 (1.16, 1.27) | 1.02 × 10−14 | Between EBER1 and EBER2 |

| 6999 | G | T | 0.95 | 0.45 | 1.21 (1.15, 1.27) | 1.21 × 10−14 | EBER2 |

| 7001 | T | A | 0.95 | 0.45 | 1.21 (1.15, 1.27) | 1.21 × 10−14 | EBER2 |

| 7012 | G | A | 0.96 | 0.46 | 1.21 (1.16, 1.27) | 4.67 × 10−15 | EBER2 |

| 7016 | T | A | 0.95 | 0.45 | 1.21 (1.15, 1.27) | 1.21 × 10−14 | EBER2 |

| 7048 | C | A | 0.95 | 0.45 | 1.21 (1.15, 1.27) | 1.21 × 10−14 | EBER2 |

| 7121 | C | CTA | 0.95 | 0.45 | 1.21 (1.16, 1.27) | 1.05 × 10−14 | EBER2 |

| 7134 | C | G | 0.95 | 0.45 | 1.21 (1.15, 1.27) | 1.21 × 10−14 | Between EBER2 and Orip |

| 7187 | A | AAACT | 0.94 | 0.45 | 1.20 (1.15, 1.26) | 4.27 × 10−14 | Between EBER2 and Orip |

| 7206 | A | T | 0.95 | 0.45 | 1.21 (1.15, 1.27) | 1.21 × 10−14 | Between EBER2 and Orip |

| 7213 | C | G | 0.95 | 0.45 | 1.21 (1.15, 1.27) | 1.21 × 10−14 | Between EBER2 and Orip |

| 7233 | A | G | 0.92 | 0.45 | 1.20 (1.14, 1.25) | 5.21 × 10−13 | Between EBER2 and Orip |

| 7262 | A | G | 0.95 | 0.45 | 1.21 (1.15, 1.27) | 1.21 × 10−14 | Between EBER2 and Orip |

| 7297 | T | C | 0.96 | 0.46 | 1.21 (1.16, 1.27) | 4.49 × 10−15 | Between EBER2 and Orip |

| 7327 | C | T | 0.96 | 0.45 | 1.22 (1.16, 1.27) | 2.39 × 10−15 | Orip |

| 11695 | G | T | 0.90 | 0.44 | 1.18 (1.12, 1.24) | 5.65 × 10−10 | BWRF1 (Upstream) |

| 137316 | C | A | 0.92 | 0.43 | 1.20 (1.15, 1.26) | 1.60 × 10−14 | BVRF2 (His560Pro) |

| 140255 | A | G | 0.95 | 0.50 | 1.18 (1.11, 1.25) | 4.65 × 10−08 | BILF2 (Upstream) |

| 140306 | C | T | 0.95 | 0.48 | 1.21 (1.16, 1.27) | 1.75 × 10−14 | BILF2 (Upstream) |

| 155989 | A | G | 0.95 | 0.46 | 1.21 (1.16, 1.27) | 8.87 × 10−15 | BALF5 (Leu100Leu) |

| 161036 | C | T | 0.92 | 0.47 | 1.19 (1.13, 1.25) | 6.63 × 10−12 | BALF2 (Ser1093Gly) |

| 163364 | T | C | 0.91 | 0.44 | 1.20 (1.14, 1.25) | 3.06 × 10−13 | BALF2 (Val317Met) |

| 163464 | A | G | 0.90 | 0.44 | 1.19 (1.13, 1.24) | 2.51 × 10−12 | BALF2 (Ser283Ser) |

| 165087 | C | T | 0.90 | 0.45 | 1.19 (1.13, 1.24) | 2.39 × 10−12 | BARF1 (Cys14Cys) |

Frequency of risk alleles in pLELC patients.

Frequency of risk alleles in healthy controls.

P-value was calculated with a linear mixed model including sex and age as fixed effects and genetic relatedness matrix as random effects.

Abbreviations: OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval.

The T-cell epitopes alternations associated with pLELC were enriched in latent genes and immediately early genes.

EBV encoded proteins have been reported to be targets for immune recognition during infection, and changes in the epitopes of these proteins may potentially affect the recognition and clearance of EBV by host immune system. By analyzing the changes of known T-cell epitopes (18), we identified 347 and 686 epitope alternations in EBV strains derived from 78 pLELC patients and 217 healthy controls, respectively. Among them, 176 alternations showed significant differences in their frequencies between two groups (P < 0.05, adjusted by false discovery rate). After controlling the effects of EBV subtypes, there were still 18 epitope-alternations enriched in EBV strains from pLELC and 14 alternations for healthy controls for the EBV of type I, the main subtype of EBV in pLELC (Table 2). Most of these differential epitope-related alternations were concentrated in latent and immediately early genes, including BZLF1 (9), EBNA3B (9), EBNA3C (4), EBNA3A (3), LMP2 (3), and BRLF1 (1). The remaining genes that contained differential epitopes included BNRF1 (2) and BLLF3 (1).

TABLE 2.

Differential changes of T-cell epitope in type-I EBV among pLELC and healthy controls

| Protein | Epitope sequence | Amino acid change | HLA Restriction |

% in pLELCa | % in controlb | Or (95% CI) | P-valuec |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LMP2 | TYGPVFMCL | C426S | A24 | 0.96 | 0.68 | 11.48 (3.46, 38.07) | 2.54 × 10−06 |

| CLGGLLTMV | C426S | A2.01 | 0.96 | 0.68 | 11.48 (3.46, 38.07) | 2.54 × 10−06 | |

| TYGPVFMCLGGLLTMVAGAV | C426S | DQB1*0601 | 0.96 | 0.68 | 11.48 (3.46, 38.07) | 2.54 × 10−06 | |

| EBNA3A | YPLHEQHGM | H464R | B35.1 | 0.22 | 0.51 | 0.28 (0.15, 0.51) | 7.72 × 10−05 |

| VQPPQLTLQV | V617E | B46 | 0.01 | 0.18 | 0.06 (0.01, 0.44) | 1.80 × 10−04 | |

| VQPPQLTLQV | P620T | B46 | 0.83 | 0.52 | 4.45 (2.29, 8.63) | 2.14 × 10−05 | |

| EBNA3B | TYSAGIVQI | I225L | A24.02 | 0.00 | 0.16 | / | 7.72 × 10−05 |

| AVFDRKSDAK | A399S | A11 | 0.12 | 0.34 | 0.26 (0.12, 0.57) | 8.74 × 10−04 | |

| AVFDRKSDAK | V400F | A11 | 0.04 | 0.27 | 0.11 (0.03, 0.36) | 4.87 × 10−05 | |

| AVFDRKSDAK | D402N | A11 | 0.68 | 0.37 | 3.45 (1.97, 6.04) | 5.91 × 10−05 | |

| IVTDFSVIK | V417L | A11 | 0.14 | 0.47 | 0.19 (0.09, 0.38) | 3.42 × 10−06 | |

| IVTDFSVIK | K424N | A11 | 0.82 | 0.43 | 6.29 (3.17, 12.46) | 4.49 × 10−07 | |

| VEITPYKPTW | Y662D | B44 | 0.05 | 0.27 | 0.15 (0.05, 0.43) | 7.72 × 10−05 | |

| VEITPYKPTW | K663E | B44 | 0.08 | 0.32 | 0.17 (0.07, 0.42) | 5.28 × 10−05 | |

| QAPTEYTRERRGVGPMPPT | A847E | DRB3*0201 | 0.14 | 0.39 | 0.26 (0.13, 0.52) | 1.72 × 10−05 | |

| EBNA3C | ILCFVMAARQRLQDI | I141V | DR13 | 0.82 | 0.59 | 3.05 (1.60, 5.84) | 1.12 × 10−05 |

| QNGALAINTF | Q213H | B62 | 0.79 | 0.48 | 4.06 (2.19, 7.55) | 2.14 × 10−05 | |

| KEHVIQNAF | E336D | B44.2 | 0.81 | 0.52 | 3.88 (2.06, 7.30) | 5.28 × 10−05 | |

| PQCFWEMRAGREITQ | R656G | 0.83 | 0.54 | 4.15 (2.09, 8.25) | 7.72 × 10−05 | ||

| BZLF1 | LLQHYREVAA | A205S | 0.77 | 0.49 | 3.38 (1.86, 6.16) | 9.52 × 10−05 | |

| RKCCRAKFKQLLQHYR | Q195H | C6 | 0.77 | 0.49 | 3.38 (1.86, 6.16) | 9.52 × 10−05 | |

| RAKFKQLL | Q195H | B8 | 0.77 | 0.49 | 3.38 (1.86, 6.16) | 9.52 × 10−05 | |

| TVQTAAAVVF | F130L | 0.75 | 0.47 | 3.43 (1.90, 6.19) | 7.72 × 10−05 | ||

| PGDNSTVQTAAAVVF | F130L | DRB1*13 | 0.75 | 0.47 | 3.43 (1.90, 6.19) | 7.72 × 10−05 | |

| PGDNSTVQTAAAVVF | A125del | DRB1*13 | 0.25 | 0.52 | 0.30 (0.17, 0.54) | 9.52 × 10−05 | |

| LQHYREVAA | Q105L | C8 | 0.75 | 0.47 | 3.43 (1.90, 6.19) | 7.72 × 10−05 | |

| VSTAPTGSWF | T68A | B58.01 | 0.75 | 0.48 | 3.35 (1.86, 6.06) | 9.52 × 10−05 | |

| LTAYHVSTAPTGSWF | T68A | DRB3*02 | 0.75 | 0.48 | 3.35 (1.86, 6.06) | 9.52 × 10−05 | |

| BRLF1 | VHEPVGSLTPAPV | V479I | 0.05 | 0.24 | 0.17 (0.06, 0.50) | 4.41 × 10−04 | |

| BLLF3 | HLTSFYSPHSDAGVL | L235I | 0.08 | 0.25 | 0.26 (0.16, 0.63) | 2.43 × 10−03 | |

| BNRF1 | PPGPSAVIEHLGSLV | G456R | 0.01 | 0.29 | 0.04 (0.005, 0.26) | 1.77 × 10−06 | |

| GPGMQQFVSSYFLNP | S497G | 0.01 | 0.24 | 0.04 (0.005, 0.30) | 5.54 × 10−06 |

Frequency of risk alleles in pLELC patients.

Frequency of risk alleles in healthy controls.

P-value was calculated using Fisher's exact test and adjusted by false discovery rate.

Abbreviations: OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval.

Genome diversity of EBV sequences derived from different diseases.

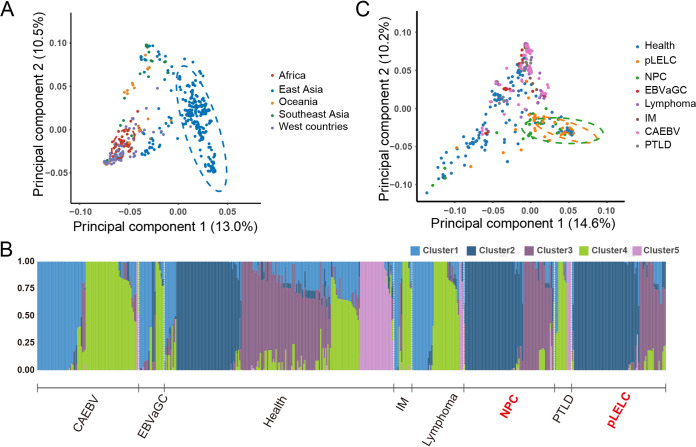

To test whether the EBV genomes derived from pLELC have distinct sequence signatures compared with other EBV-associated diseases, principal-component analysis (PCA) was performed with 115 EBV isolates from current study and 622 available EBV genomes from GenBank (Table S5). The first principal-component (PC1) explained 13.0% of the total genomic variance, and was related to geographical distribution, which could clearly distinguish the EBV strains from East Asia (Fig. 3A). Phylogenetic analysis also confirmed this phenomenon of geographical evolution, with the EBV of the same geographical origin tending to distribute together (Fig. S2).

FIG 3.

Principal component and population structure analysis of EBV genome. (A) Principal-component analysis (PCA) of 115 EBV isolates newly assembled in our study and 622 published isolates worldwide. The first two principal-component scores (PC1 and PC2) are indicated in the axes. PC1 explains 13.0% of the total genomic variance, which can clearly distinguish the EBV strains from East Asia. (B) Admixture analysis with 520 EBV isolates derive from East Asia. EBV strains from pLELC (consist of Cluster2/Cluster3-dominated EBV strains) share highest similarity with those from NPC compared with other diseases. (C) PCA of 520 EBV isolates derive from East Asia. CAEBV, chronic active EBV infection; EBVaGC, EBV-associated gastric carcinoma; IM, infectious mononucleosis; NPC, nasopharyngeal carcinoma; PTLD, posttransplant lymphoproliferative disorders; pLELC, pulmonary lymphoepithelioma-like carcinoma.

Considering the distinct geographical distribution, we conducted population structure analysis and clustered the EBV strains derived from East Asia into five clusters, according to genetic similarity of EBV sequences. Clustering results showed the EBV strains from healthy carriers contained all five clusters, but different diseases present their own EBV cluster characteristics (Fig. 3B and Table S6). In general, EBV strains from pLELC (consist of Cluster2/Cluster3-dominated EBV strains) shared highest similarity with those from NPC compared to other diseases (EBVaGC, EBV-associated lymphoma, etc.), which partly explained the similarities in histological and biological characteristics between pLELC and NPC from virological perspective. In addition, PCA of EBV strains from East Asia also illustrated the similarity of EBV strains between pLELC and NPC (Fig. 3C).

EBV-human integration in pLELC.

Previous studies have shown the integration events between virus (including EBV) and human genome play important roles in carcinogenicity. To further investigate the pathogenesis of EBV in pLELC, a genome-wide analysis of EBV integrations was performed. A total of 179 EBV-host integration sites were identified by bioinformatics methods and only seven were verified via targeted PCR amplification and Sanger sequencing (Table S7 and Fig. S3). These integration events occurred in three patients, all of whom had advanced tumors (stage III∼IV). We noticed an integration hot spot, chromosome subband 4q28.3, was integrated twice in one patient, and there was another integration breakpoint located in adjacent subband 4q31.21 for the same patient. Of all integration breakpoints, four (57.1%) were located in the introns of known UCSC-annotated genes (ETS1, SLC7A11-AS1, PGS1, and SGSM3). In addition, there were three other genes (SOCS3, SLCTA11, and ZNF330) whose transcription start sites (TSSs) were within 50 kb from breakpoints. No genes were integrated recurrently as reported in NPC.

EBV genomes were hypermethylated and expressed type-II latency profile in pLELC.

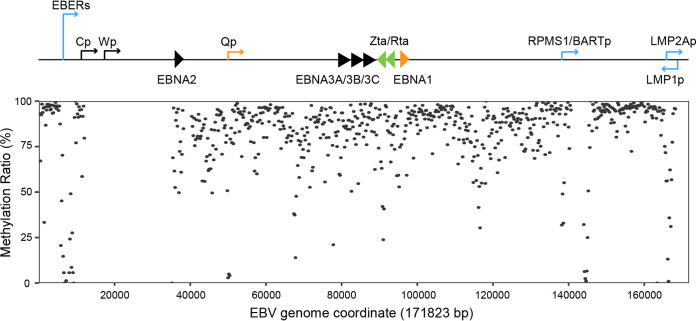

To further explore the biological characteristics of EBV in pLELC, we performed genome-wide methylation profiling of EBV genomes from five patients. We first divided the EBV genome into non-overlapping regions of 200 bp, and found the EBV genome exhibited global hypermethylation in pLELC (Fig. 4). Then we assessed CpG methylation densities in each potential promoter region. The result showed Q promoter (Qp), the specific promoter for EBNA1, was escaped from DNA methylation, however, the other promoter for EBNAs genes, C promoter (Cp), was hypermethylated in our study. We also observed several other regions with hypomethylation status, including the promoters for EBERs and LMP2A (Table 3). These methylation characteristics were similar to that previously reported in NPC, showing “Cp off” latency, with the hypomethylation of Qp and LMPs promoters and the hypermethylation of Cp (19).

FIG 4.

Methylation landscape of EBV genome in pLELC. The schematic of EBV genome showed the transcription start sites of the major latency transcripts and lytic immediate early genes BZLF1 (Zta) and BRLF1 (Rta). The plot displayed methylation densities of CpG loci across the EBV DNA genome from the pooled sequencing data of the five pLELC patients. Each dot shows the methylation density at corresponding CpG sites within 200 bp.

TABLE 3.

Methylation and expression profiles for pLELC-derived EBV stains

| Methylation |

Expression |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Promotera | Methylated CpGs | Unmethylated CpGs | Methylation ratio (%)b | Gene | Positive case, n/n (%) |

| EBERp | 30 | 380 | 7.32 | EBER1 | 22/23 (96) |

| Qp | 31 | 1218 | 2.48 | EBNA1 | 9/23 (39) |

| Cp | 624 | 62 | 90.96 | EBNA2 | 0/23 (0) |

| LMP1p | / | / | / | LMP1 | 23/23 (100) |

| LMP2Ap | 185 | 151 | 55.06 | LMP2A | 22/23 (96) |

| BZLF1p | 37 | 36 | 50.68 | BZLF1 | 13/23 (57) |

| BRLF1p | 233 | 54 | 81.18 | BRLF1 | 9/23 (39) |

| BMLF1p | / | / | / | BMLF1 | 0/23 (0) |

| BLLF1p | 141 | 31 | 81.98 | BLLF1 | 9/23 (39) |

Potential promoters were calculated from 200 bp upstream to 50 bp downstream of the transcription start sites.

The methylation ratio was calculated by: methylatedCpGs/(methylatedCpGs + unmethylatedCpGs)×100.

To determine the infection status of EBV in pLELC, the mRNA level of EBV-encoded genes, including five latent genes (EBER, LMP1, LMP2A, EBNA1, and EBNA2) and four lytic genes (BZLF1, BRLF1, BMLF1, and BLLF1) were measured (Table 3). The latency II transcription profile with LMP1 (23/23), LMP2A (23/23), EBNA1 (8/23) but not EBNA2 (0/23) expression was observed in EBV strains from pLELC, which is similar to that of NPC. Except for the latent genes, limited lytic genes expression could also be detected in partial samples. Two immediately early genes, BZLF1 and BRLF1, had the positive detection rates of 56.5% and 39.1%, respectively. In addition, the EBV membrane protein encoding gene, BLLF1 (encoding envelope glycoprotein gp350) was expressed in 39.1% of the pLELC patients. However, no positive expression signal was observed for the early gene BMLF1 in all patients.

DISCUSSION

PLELC is a distinct subset of EBV-associated NSCLC, whose genomic profiles of EBV have not been well explored. In this study, we provided the first global view of the genomic characteristics of pLELC-derived EBV through targeted sequencing analysis. Meanwhile, dozens of pLELC-associated EBV variations were identified through GWAS of 78 pLELC patients and 217 healthy controls. We also systematically characterized the integration and methylation landscape of EBV strains in pLELC patients.

The EBV genome was stable, and low-level genomic evolution occurs during in vivo infection (20). In this study, the low proportion of heterogeneous sites relative to the genome-wide variations ranged from 0.00% to 1.05% for the EBV strains derived from tissue samples of pLELC, indicating the probable clonal expansion of EBV in pLELC patients. However, because the EBV strains of healthy controls were isolated from saliva samples, 14 (6.1%) healthy carriers infected with multiple strains, which means the presence of transient multiple infections. These findings were consistent with the current view of monoclonal origin of EBV in EBV-associated tumors (12).

Similar to the studies on other EBV-associated malignancies, the latent genes were the most diverse regions of the viral genome, indicating selection pressures on these genes during latent infection (11, 12). Compared with the healthy controls, 32 amino acids alterations of T-cell epitopes with different frequencies were detected in type I EBV strains from pLELC. Most of these epitopes located in latent genes (LMP2, EBNA1, EBNA3A, EBNA3B, and EBNA3C) or immediately early genes (BZLF1 and BRLF1). Meanwhile, the frequencies of these EBV epitopes changes were similar in pLELC and NPC, but different from EBVaGC or EBV-positive lymphomas (Fig. S4). These alternations might help the EBV escape from immune recognition and maintain long-term latent infection, thus promoting malignant transformation of host cells. Moreover, because LMP2 were the important target antigens for cytotoxic T-lymphocytes therapies in patients with NPC or EBV-positive lymphoma, these changes might affect the therapeutic efficacy (21).

Previous studies have reported some variations in EBV sequences are associated with a variety of malignancies (11, 12). Through association analysis across the EBV genome, a total of 32 variations were enriched in the EBV strains derived from patients with pLELC other than healthy controls. Most of these high-risk variations (22/32) for pLELC were located in the EBER regions, a known area associated with the risk of NPC. Functionally, these variations could alter the secondary structure of EBER2, thereby affecting the pathogenicity of EBV (11). Moreover, we identified several previously reported NPC-associated EBV genomic variations were also present in the EBV strains from pLELC, such as the variations within the genes BNRF1 (A5399G), BVRF2 (A137316C), and BALF2 (C163364T), which led to the amino acid changes in the tegument protein BNRF1 (V1222I), virus serine protease BVRF2 (H560P), and DNA-binding protein BALF2 (V317M), respectively (11). These finding suggest the EBV strains derived from pLELC were the similar subspecies to those from NPC. Detecting these high-risk EBV variations could identify the high-risk individuals of both pLELC and NPC in clinical early screening. Meanwhile, we reported several other EBV sequence variations around genes BWRF1, BILF2, BALF5, and BARF1, which might be related to the malignant transformation ability of pulmonary epithelium of EBV. Given the high linkage disequilibrium among these risk variations, we suggest this may be a potentially high-risk subtype of pLELC as well as NPC. Further functional studies of the genes and sequence variations are needed.

Previous studies on whole-exome sequencing for pLELC patients revealed pLELC genetically resembled NPC but significantly differed from other kinds of NSCLC (4). In the current study, we found a strong similarity between the EBV genome from pLELC and that from NPC through multidimensional comparative analysis. In addition, we performed the phylogenetic analysis with the EBV strains from pLELC and other kinds of NSCLC (three squamous cell carcinomas and one adenocarcinoma) reported by Wang et al. (22). We noticed a closer distance among three EBV strains (LC1, LC3, and LC4) from Wang’s study, while LC2 was clustered into the pLELC-dominated branch (Fig. S5). This phenomenon revealed that pLELC is a special subtype of NSCLC from the perspective of EBV infection. Based on the above findings and the radiotherapy sensitivity of NPC (23), we hypothesized radiotherapy might bring greater benefits to pLELC patients, especially those who cannot be cured by surgical resection.

Virus-host integration has been considered an important carcinogenic mechanism for oncogenic viruses (24). We also observed EBV-human integration breakpionts in pLELC patients. However, of the 179 potential integration sites identified by bioinformatics analysis, only seven were technically validated. This phenomenon indicted the importance of validation in the virus-host integration researches. It was noteworthy that all three patients affected by the integration events had advanced tumors. Unlike the high frequency of human papillomavirus (HPV) integration in cervical carcinoma (76.3%) and hepatitis B virus (HBV) integration in hepatocellular carcinoma (100%), we noted integration events occurred at fairly low frequency in pLELC (5.1%), which was similar to the previous integration characteristics of EBV in NPC- (9.6%) and EBV-associated lymphoma (16.7%) (15, 25, 26). These differences can be explained by the following reasons. Firstly, EBV had a larger and more stable genome than HBV or HPV, which made the sequence integrations mediated by homologous recombination less common. Secondly, the mechanisms underlying carcinogenesis differed among the tumors associated with different viruses.

Our results showed four of seven identified integration breakpoints were located within cellular genes. One of the integration breakpoints was located in the intron region of the transcription factor ETS1 and 200 kb away from the TSS of FIL1, another transcription factor of the same family. Translocation fusion of these genes with EWSR1 gene have been known to cause Ewing’s sarcoma as well as primary neuroectodermal tumors (27). We also detected an integration breakpoint 44 kb upstream of tumor suppressor gene SOCS3 (28). And another breakpoint was 33 kb upstream of gene SLCTA11, encoding vector protein that regulates herpesvirus fusion and entry into cells (29). Integration might affect the expression and function of these genes, thereby promoting carcinogenesis.

Although pLELC was considered as a kind of EBV-associated tumor, the status of EBV infection in pLELC remained unclear. Our results showed the typical latency type II transcripts (including LMP1, LMP2A, EBNA1, but not EBNA2) could be detected in pLELC samples, with no or limited transcripts of lytic genes. This phenomenon indicated EBV was predominantly type II latent infection in pLELC patients, but either full or abortive viral reactivation could be induced sporadically. Besides, the methylation profiles of EBV derived from pLELC also supported the latent infection status of type II for EBV in pLELC, characterized by Cp hypermethylation, Qp, and LMPs promoter hypomethylation. These results indicated the methylation and expression status of EBV strains in pLELC were greatly similar to those of NPC. Tao et al. found similar Cp hypermethylation and Qp hypomethylation in BL tissues, but without LMP1 gene expression (30), implying the latent I infection. As for the EBVaGC, Li et al. reported that the LMPs promoters were hypermethylated and mediated the silencing of the LMPs genes, which exhibited type I latent characteristics (31), but Chen et al. reported the hypomethylation of LMPs promoters and potential type II latent infection as pLELC.

One of the limitations in our study is that due to the shortage of short-read sequencing, the variations in repeat regions were not explored. Second, despite finding the existence of EBV-human integrations, the lengths of the fragments inserted by EBV were still unknown. In addition, whether these fusion genes were expressed remained unclear. Future studies are needed to address these issues.

In summary, we have systematically mapped the EBV genomic atlas in pLELC, and identified 32 high-risk EBV variations through a genome-wide case-control study. Our findings indicate the presence of EBV-human integration sites and provide new perspectives for understanding EBV’s role in the etiology of pLELC. Further studies are needed to explore the tumorigenic effects of EBV variations and EBV-human integrations on pLELC.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study participants and samples.

A total of 78 patients diagnosed with primary preliminary pLELC at Sun Yat-sen University Cancer Center (SYSUCC) between January 2012 and May 2019 were recruited in this study, whose clinicopathologic characteristics were summarized in Table S8. All the patients received surgical resection and frozen tissue samples were collected during surgery. Saliva samples were collected from 42 healthy carriers, who were enrolled from a population-based study in the Guangdong province (32). All fresh-frozen tumor tissue and saliva specimens were stored at −80°C. Meanwhile, the publicly available EBV-captured sequencing data of other 189 healthy controls were gained from SRP152584 and PRJNA522388. The study was approved by the institutional ethics committee of SYSUCC, and informed consents were obtained from all participants.

DNA extraction, EBV genome quantification, and whole-genome sequencing.

Genomic DNAs were extracted from both frozen tissue and saliva samples using the Chemagic Star workstation described in our previous study (33). EBV DNA load was detected by real-time qPCR toward the BamHI-W region. The sequences of the primers and probe are listed in Table S9. To construct EBV-targeted capture libraries, genomic DNA was fragmented, purified, end blunted, adaptor ligated, and amplified by the NanoPrepTM DNA library construction kit (for Illumina®). Pretreatment DNA was subjected to hybrid capture using the EBV-targeting single-stranded DNA probes (Integrated DNA Technologies). After capture enrichment with xGen Target Enrichment Kit (for Illumina®), libraries were sequenced (paired-end 150 bp) using the Illumina NovaSeq 6000 platform.

Sequencing data preprocessing and multiple infection analysis.

After preprocessing the raw data using Trimmomatic (34), paired-reads that perfectly aligned to human genome (NCBI build 37, Hg19) with Bowtie2 were removed (35). Remaining reads were realigned to EBV-wt using the Burrow Wheeler Aligner (36) and duplicate reads were removed by Picard (37). Read counts for each genotype at every position were calculated using BCFtools (38) and in-house scripts. A position was defined as heterogeneous if two alleles were observed at that position and both had frequency over 10% and sequencing-depth more than 5. All patient samples and 217 healthy controls had heterozygous variation of less than 10% and were defined as single infection, and conversely, 14 healthy control samples (including five from current study and nine from public databases) above this threshold were identified as multiple infections.

Genome assembly, variation calling, and variation analysis.

For single-infection samples, the EBV-aligned reads were assembled into contigs using Velvet (39), with kmer sizes setting from 37 to 77. Draft-contigs were polished by Pilon (40), then oriented using ABACAS (41) against EBV-wt and the gaps were narrowed with GapFiller (42). The unrecognized regions were filled with “N” toward EBV-wt genome. Finally, quality assessment of each EBV genome was carried out using Quast (43). Assembled EBV sequences were aligned to EBV-wt using Minimap2 (44) and the variations were called by BCFtools. To increase the accuracy of calling, we further filtered out variations that were within 5 bp of indels or in repeat regions. SnpEFF (45) was used for functional annotation of EBV variations. The types of EBV genomes were differentiated by the similarities of EBNA2 and EBNA3s genes against type I and type II EBV reference genomes (EBV-wt and DQ279927) (6). Moreover, alterations of T-cell epitopes were deduced according to the changes of known T-cell epitope sequences (18). To compare the T-cell epitope alternation frequencies between two groups, Fisher’s exact test was conducted using R (version 3.6.3) with FDR adjusted P < 0.05 as statistically significant.

Association analysis.

After filtering variations with minor genotype frequency < 0.05 or call ratio < 0.90, the EBV GWAS was performed using GEMMA (46) with a linear mixed model including sex and age as fixed effects and genetic relatedness matrix as random effects. Bonferroni correction was used for adjustment of statistical significance. Linkage disequilibrium was analyzed and visualized by LDBlockShow (47).

Population genetic and phylogenetic analysis.

Six-hundred and 22 published EBV genomes with known origins and phenotypes were obtained from GenBank, and variations were identified with the same pipeline described above (Table S5). For the PCA, we used the R package SNPRelate (48). Population structure analysis was performed using Admixture (49). To construct a phylogenetic tree, fasta sequences were created using SNPs for all EBV genomes. Maximum likelihood tree was built using IQ-TREE (50) with the model of general time reversible and ascertainment bias correction (GTR + ASC).

Integration analysis.

After removing the reads with paired-end aligning completely to the human or EBV reference genomes, human-EBV integration sites were identified by Seeksv (51), with integration signals as follows: (a) discordant reads, with a read pair having one end mapped to the human genome and the other to the EBV genome; and (b) split reads, with individual read which aligned to both the human and EBV genome. The sites with integration signals > 3 were selected (15). Targeted PCR amplification and Sanger sequencing were used to verify potential EBV-host integration breakpoints. Primers were designed based on split reads, with one end matching the human genome and the other end matching the EBV genome (Table S9). The integration breakpoints were annotated using ANNOVAR (52).

Methylation library construction, sequencing, and bioinformatics analysis.

The pool tissue DNA library from five pLELC patients was constructed using the VariantBaitsTM Target Enrichment Library Prep Kit (LC-Bio Tech). The captured EBV DNA molecules were subjected to bisulfite treatment using Zymo Research EZ DNA Methylation-Gold Kit (Zymo Research). After bisulfite conversion, DNA was amplified using the SureSelect Methyl-Seq PCR Kit (Agilent Technologies). Then, the preprocessed DNA library was sequenced (paired-end 150 bp) using the NovaSeq 6000 system (Illumina). The bisulfite sequencing data were analyzed using Methy-Pipe (53). The fractions of unconverted cytosines (methylated) over the sum of unconverted cytosines (methylated) and converted thymine (unmethylated) present in its total depth were calculated as the methylation rates across the EBV genome.

RNA extraction, cDNA synthesis, and quantitative real-time PCR.

Total RNA from 24 tumor tissues were extracted using TRIzol Reagent (Invitrogen). For each sample, a total of 500 ng RNA was first used for cDNA synthesis with PrimeScript RT reagent kit with gDNA Eraser (TaKaRa). Reverse transcription was successfully completed in 23 samples. Relative quantification of transcription levels of five latent genes (EBER, LMP1, LMP2A, EBNA1, and EBNA2) and four lytic genes (BZLF1, BRLF1, BMLF1, and BLLF1) were measured using quantitative real-time reverse transcription-PCR (qRT-PCR). The level of GAPDH was used for EBV mRNA level normalization. The primer sequences for qRT-PCR are listed in Table S9.

Data availability.

All the newly assembled EBV sequences have been deposited in GenBank under accession numbers OM022115 to OM022229. The key raw data have been uploaded to the Research Data Deposit (RDD; http://www.researchdata.org.cn/) with an approval number of RDDA2021720248.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (grant number 2016YFC1302700), the Sino-Sweden joint research program (grant number 81861138006), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant numbers 81973131, 81903395, 81802708, 81803319, 82003520), the Natural Science Foundation of Guangdong Province, China (grant number 2021A1515012397), the Science and Technology Planning Project of Guangzhou, China (grant numbers 201804020094, 201904010467, 2019B030316031); the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (grant number 19ykpy185), the Key Area Research and Development Program of Guangdong Province (grant number 2019B110233004).

Yan-Xia Wu and Wen-Li Zhang contributed to study design, data collection, and analysis, and manuscript writing. Tong-Min Wang contributed to the quality control of data and algorithms, data analysis, and manuscript editing. Ying Liao, Yi-Jun Zhang, Ruo-Wen Xiao, Yi-Jing Jia, Zi-Yi Wu, Chang-Mi Deng, Da-Wei Yang, Wen-Qiong Xue, Yong-Qiao He, Xiao-Hui Zheng, Xi-Zhao Li, Ting Zhou, Pei-Fen Zhang, Shao-Dan Zhang, and Ye-Zhu Hu contributed to sample collection, quality control, and data acquisition. Jiang-Bo Zhang and Wei-Hua Jia conceived and designed the study, and edited and reviewed the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Footnotes

Supplemental material is available online only.

Contributor Information

Jiang-Bo Zhang, Email: zhangjb@sysucc.org.cn.

Wei-Hua Jia, Email: jiawh@sysucc.org.cn.

Jae U. Jung, Lerner Research Institute, Cleveland Clinic

REFERENCES

- 1.Young LS, Yap LF, Murray PG. 2016. Epstein-Barr virus: more than 50 years old and still providing surprises. Nat Rev Cancer 16:789–802. 10.1038/nrc.2016.92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bégin LR, Eskandari J, Joncas J, Panasci L. 1987. Epstein-Barr virus related lymphoepithelioma-like carcinoma of lung. J Surg Oncol 36:280–283. 10.1002/jso.2930360413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Xie M, Wu X, Wang F, Zhang J, Ben X, Zhang J, Li X. 2018. Clinical significance of plasma Epstein-Barr virus DNA in pulmonary lymphoepithelioma-like carcinoma (LELC) patients. J Thoracic Oncology 13:218–227. 10.1016/j.jtho.2017.10.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hong S, Liu D, Luo S, Fang W, Zhan J, Fu S, Zhang Y, Wu X, Zhou H, Chen X, Chen G, Zhang Z, Zheng Q, Li X, Chen J, Liu X, Lei M, Ye C, Wang J, Yang H, Xu X, Zhu S, Yang Y, Zhao Y, Zhou N, Zhao H, Huang Y, Zhang L, Wu K, Zhang L. 2019. The genomic landscape of Epstein-Barr virus-associated pulmonary lymphoepithelioma-like carcinoma. Nat Commun 10:3108. 10.1038/s41467-019-10902-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen B, Zhang Y, Dai S, Zhou P, Luo W, Wang Z, Chen X, Cheng P, Zheng G, Ren J, Yang X, Li W. 2021. Molecular characteristics of primary pulmonary lymphoepithelioma-like carcinoma based on integrated genomic analyses. Signal Transduct Target Ther 6:6. 10.1038/s41392-020-00382-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Palser AL, Grayson NE, White RE, Corton C, Correia S, Ba Abdullah MM, Watson SJ, Cotten M, Arrand JR, Murray PG, Allday MJ, Rickinson AB, Young LS, Farrell PJ, Kellam P. 2015. Genome diversity of Epstein-Barr virus from multiple tumor types and normal infection. J Virol 89:5222–5237. 10.1128/JVI.03614-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kanda T, Yajima M, Ikuta K. 2019. Epstein-Barr virus strain variation and cancer. Cancer Sci 110:1132–1139. 10.1111/cas.13954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Johnson RJ, Stack M, Hazlewood SA, Jones M, Blackmore CG, Hu LF, Rowe M. 1998. The 30-base-pair deletion in Chinese variants of the Epstein-Barr virus LMP1 gene is not the major effector of functional differences between variant LMP1 genes in human lymphocytes. J Virol 72:4038–4048. 10.1128/JVI.72.5.4038-4048.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bristol JA, Djavadian R, Albright ER, Coleman CB, Ohashi M, Hayes M, Romero-Masters JC, Barlow EA, Farrell PJ, Rochford R, Kalejta RF, Johannsen EC, Kenney SC. 2018. A cancer-associated Epstein-Barr virus BZLF1 promoter variant enhances lytic infection. PLoS Pathog 14:e1007179. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1007179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhang J-B, Huang S-Y, Wang T-M, Dong S-Q, He Y-Q, Zheng X-H, Li X-Z, Wang F, Jianbing M, Jia W-H. 2018. Natural variations in BRLF1 promoter contribute to the elevated reactivation level of Epstein-Barr virus in endemic areas of nasopharyngeal carcinoma. EBioMedicine 37:101–109. 10.1016/j.ebiom.2018.10.065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hui KF, Chan TF, Yang W, Shen JJ, Lam KP, Kwok H, Sham PC, Tsao SW, Kwong DL, Lung ML, Chiang AKS. 2019. High risk Epstein-Barr virus variants characterized by distinct polymorphisms in the EBER locus are strongly associated with nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Int J Cancer 144:3031–3042. 10.1002/ijc.32049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Xu M, Yao Y, Chen H, Zhang S, Cao S-M, Zhang Z, Luo B, Liu Z, Li Z, Xiang T, He G, Feng Q-S, Chen L-Z, Guo X, Jia W-H, Chen M-Y, Zhang X, Xie S-H, Peng R, Chang ET, Pedergnana V, Feng L, Bei J-X, Xu R-H, Zeng M-S, Ye W, Adami H-O, Lin X, Zhai W, Zeng Y-X, Liu J. 2019. Genome sequencing analysis identifies Epstein-Barr virus subtypes associated with high risk of nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Nat Genet 51:1131–1136. 10.1038/s41588-019-0436-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Xue W-Q, Wang T-M, Huang J-W, Zhang J-B, He Y-Q, Wu Z-Y, Liao Y, Yuan L-L, Mu J, Jia W-H. 2021. A comprehensive analysis of genetic diversity of EBV reveals potential high-risk subtypes associated with nasopharyngeal carcinoma in China. Virus Evolution 7. 10.1093/ve/veab010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ohshima K, Suzumiya J, Kanda M, Kato A, Kikuchi M. 1998. Integrated and episomal forms of Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) in EBV associated disease. Cancer Lett 122:43–50. 10.1016/s0304-3835(97)00368-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Xu M, Zhang WL, Zhu Q, Zhang S, Yao YY, Xiang T, Feng QS, Zhang Z, Peng RJ, Jia WH, He GP, Feng L, Zeng ZL, Luo B, Xu RH, Zeng MS, Zhao WL, Chen SJ, Zeng YX, Jiao Y. 2019. Genome-wide profiling of Epstein-Barr virus integration by targeted sequencing in Epstein-Barr virus associated malignancies. Theranostics 9:1115–1124. 10.7150/thno.29622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cao S, Strong MJ, Wang X, Moss WN, Concha M, Lin Z, O'Grady T, Baddoo M, Fewell C, Renne R, Flemington EK. 2015. High-throughput RNA sequencing-based virome analysis of 50 lymphoma cell lines from the Cancer Cell Line Encyclopedia project. J Virol 89:713–729. 10.1128/JVI.02570-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sample J, Young L, Martin B, Chatman T, Kieff E, Rickinson A, Kieff E. 1990. Epstein-Barr virus types 1 and 2 differ in their EBNA-3A, EBNA-3B, and EBNA-3C genes. J Virol 64:4084–4092. 10.1128/JVI.64.9.4084-4092.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Taylor GS, Long HM, Brooks JM, Rickinson AB, Hislop AD. 2015. The immunology of Epstein-Barr virus-induced disease. Annu Rev Immunol 33:787–821. 10.1146/annurev-immunol-032414-112326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Takacs M, Banati F, Koroknai A, Segesdi J, Salamon D, Wolf H, Niller HH, Minarovits J. 2010. Epigenetic regulation of latent Epstein-Barr virus promoters. Biochim Biophys Acta 1799:228–235. 10.1016/j.bbagrm.2009.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Weiss ER, Lamers SL, Henderson JL, Melnikov A, Somasundaran M, Garber M, Selin L, Nusbaum C, Luzuriaga K. 2018. Early Epstein-Barr virus genomic diversity and convergence toward the B95.8 genome in primary infection. J Virol 92:e01466. 10.1128/JVI.01466-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bollard CM, Gottschalk S, Torrano V, Diouf O, Ku S, Hazrat Y, Carrum G, Ramos C, Fayad L, Shpall EJ, Pro B, Liu H, Wu M-F, Lee D, Sheehan AM, Zu Y, Gee AP, Brenner MK, Heslop HE, Rooney CM. 2014. Sustained complete responses in patients with lymphoma receiving autologous cytotoxic T lymphocytes targeting Epstein-Barr virus latent membrane proteins. J Clin Oncol 32:798–808. 10.1200/JCO.2013.51.5304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang S, Xiong H, Yan S, Wu N, Lu Z. 2016. Identification and characterization of Epstein-Barr Virus genomes in lung carcinoma biopsy samples by next-generation sequencing technology. Sci Rep 6:26156. 10.1038/srep26156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chen Y-P, Chan ATC, Le Q-T, Blanchard P, Sun Y, Ma J. 2019. Nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Lancet (London, England) 394:64–80. 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)30956-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chen Y, Williams V, Filippova M, Filippov V, Duerksen-Hughes P. 2014. Viral carcinogenesis: factors inducing DNA damage and virus integration. Cancers (Basel) 6:2155–2186. 10.3390/cancers6042155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hu Z, Zhu D, Wang W, Li W, Jia W, Zeng X, Ding W, Yu L, Wang X, Wang L, Shen H, Zhang C, Liu H, Liu X, Zhao Y, Fang X, Li S, Chen W, Tang T, Fu A, Wang Z, Chen G, Gao Q, Li S, Xi L, Wang C, Liao S, Ma X, Wu P, Li K, Wang S, Zhou J, Wang J, Xu X, Wang H, Ma D. 2015. Genome-wide profiling of HPV integration in cervical cancer identifies clustered genomic hot spots and a potential microhomology-mediated integration mechanism. Nat Genet 47:158–163. 10.1038/ng.3178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li X, Zhang J, Yang Z, Kang J, Jiang S, Zhang T, Chen T, Li M, Lv Q, Chen X, McCrae MA, Zhuang H, Lu F. 2014. The function of targeted host genes determines the oncogenicity of HBV integration in hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol 60:975–984. 10.1016/j.jhep.2013.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Romeo S, Dei Tos AP. 2010. Soft tissue tumors associated with EWSR1 translocation. Virchows Arch 456:219–234. 10.1007/s00428-009-0854-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yin Y, Liu W, Dai Y. 2015. SOCS3 and its role in associated diseases. Hum Immunol 76:775–780. 10.1016/j.humimm.2015.09.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kaleeba JAR, Berger EA. 2006. Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus fusion-entry receptor: cystine transporter xCT. Science 311:1921–1924. 10.1126/science.1120878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tao Q, Robertson KD, Manns A, Hildesheim A, Ambinder RF. 1998. Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) in endemic Burkitt's lymphoma: molecular analysis of primary tumor tissue. Blood 91:1373–1381. 10.1182/blood.V91.4.1373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Li J, Liu X, Liu M, Che K, Luo B. 2016. Methylation and expression of Epstein-Barr virus latent membrane protein 1, 2A and 2B in EBV-associated gastric carcinomas and cell lines. Dig Liver Dis 48:673–680. 10.1016/j.dld.2016.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ye W, Chang ET, Liu Z, Liu Q, Cai Y, Zhang Z, Chen G, Huang Q-H, Xie S-H, Cao S-M, Shao J-Y, Jia W-H, Zheng Y, Liao J, Chen Y, Lin L, Liang L, Ernberg I, Vaughan TL, Huang G, Zeng Y, Zeng Y-X, Adami H-O. 2017. Development of a population-based cancer case-control study in Southern China. Oncotarget 8:87073–87085. 10.18632/oncotarget.19692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zheng X-H, Lu L-X, Li X-Z, Jia W-H. 2015. Quantification of Epstein-Barr virus DNA load in nasopharyngeal brushing samples in the diagnosis of nasopharyngeal carcinoma in southern China. Cancer Sci 106:1196–1201. 10.1111/cas.12718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bolger AM, Lohse M, Usadel B. 2014. Trimmomatic: a flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics 30:2114–2120. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Langmead B, Salzberg SL. 2012. Fast gapped-read alignment with Bowtie 2. Nat Methods 9:357–359. 10.1038/nmeth.1923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Li H, Durbin R. 2009. Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows-Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics 25:1754–1760. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wysoker A, Tibbetts K, Fennell T. 2013. Picard tools version 1.90. Jhpsn 107:308. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Li H. 2011. A statistical framework for SNP calling, mutation discovery, association mapping and population genetical parameter estimation from sequencing data. Bioinformatics 27:2987–2993. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btr509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zerbino DR, Birney E. 2008. Velvet: algorithms for de novo short read assembly using de Bruijn graphs. Genome Res 18:821–829. 10.1101/gr.074492.107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Walker BJ, Abeel T, Shea T, Priest M, Abouelliel A, Sakthikumar S, Cuomo CA, Zeng Q, Wortman J, Young SK, Earl AM. 2014. Pilon: an integrated tool for comprehensive microbial variant detection and genome assembly improvement. PLoS One 9:e112963. 10.1371/journal.pone.0112963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Assefa S, Keane TM, Otto TD, Newbold C, Berriman M. 2009. ABACAS: algorithm-based automatic contiguation of assembled sequences. Bioinformatics 25:1968–1969. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Boetzer M, Pirovano W. 2012. Toward almost closed genomes with GapFiller. Genome Biol 13:R56. 10.1186/gb-2012-13-6-r56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gurevich A, Saveliev V, Vyahhi N, Tesler G. 2013. QUAST: quality assessment tool for genome assemblies. Bioinformatics 29:1072–1075. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btt086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Li H. 2018. Minimap2: pairwise alignment for nucleotide sequences. Bioinformatics 34:3094–3100. 10.1093/bioinformatics/bty191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cingolani P, Platts A, Wang LL, Coon M, Nguyen T, Wang L, Land SJ, Lu X, Ruden DM. 2012. A program for annotating and predicting the effects of single nucleotide polymorphisms, SnpEff: SNPs in the genome of Drosophila melanogaster strain w1118; iso-2; iso-3. Fly (Austin) 6:80–92. 10.4161/fly.19695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhou X, Stephens M. 2012. Genome-wide efficient mixed-model analysis for association studies. Nat Genet 44:821–824. 10.1038/ng.2310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Dong S-S, He W-M, Ji J-J, Zhang C, Guo Y, Yang T-L. 2021. LDBlockShow: a fast and convenient tool for visualizing linkage disequilibrium and haplotype blocks based on variant call format files. Briefings in Bioinformatics 22. 10.1093/bib/bbaa227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zheng X, Levine D, Shen J, Gogarten SM, Laurie C, Weir BS. 2012. A high-performance computing toolset for relatedness and principal component analysis of SNP data. Bioinformatics 28:3326–3328. 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Alexander DH, Novembre J, Lange K. 2009. Fast model-based estimation of ancestry in unrelated individuals. Genome Res 19:1655–1664. 10.1101/gr.094052.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Nguyen L-T, Schmidt HA, von Haeseler A, Minh BQ. 2015. IQ-TREE: a fast and effective stochastic algorithm for estimating maximum-likelihood phylogenies. Mol Biol Evol 32:268–274. 10.1093/molbev/msu300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Liang Y, Qiu K, Liao B, Zhu W, Huang X, Li L, Chen X, Li K. 2017. Seeksv: an accurate tool for somatic structural variation and virus integration detection. Bioinformatics 33:184–191. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btw591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wang K, Li M, Hakonarson H. 2010. ANNOVAR: functional annotation of genetic variants from high-throughput sequencing data. Nucleic Acids Res 38:e164. 10.1093/nar/gkq603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Jiang P, Sun K, Lun FMF, Guo AM, Wang H, Chan KCA, Chiu RWK, Lo YMD, Sun H. 2014. Methy-Pipe: an integrated bioinformatics pipeline for whole genome bisulfite sequencing data analysis. PLoS One 9:e100360. 10.1371/journal.pone.0100360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1 to Table S9. Download jvi.01693-21-s0001.xlsx, XLSX file, 0.3 MB (294.9KB, xlsx)

Fig. S1 to Fig. S5. Download jvi.01693-21-s0002.pdf, PDF file, 1.0 MB (1MB, pdf)

Data Availability Statement

All the newly assembled EBV sequences have been deposited in GenBank under accession numbers OM022115 to OM022229. The key raw data have been uploaded to the Research Data Deposit (RDD; http://www.researchdata.org.cn/) with an approval number of RDDA2021720248.