Abstract

Background

Obesity has been shown to increase the risk of severe outcomes and death for influenza virus infections. However, we do not understand the influence of obesity on susceptibility to infection or on nonsevere influenza outcomes.

Methods

We performed a case-ascertained, community-based study of influenza transmission within households in Nicaragua. To investigate whether obesity increases the likelihood of influenza infection and symptomatic infection we used logistic regression models.

Results

Between 2015 and 2018, a total of 335 index cases with influenza A and 1506 of their household contacts were enrolled. Obesity was associated with increased susceptibility to symptomatic H1N1pdm infection among adults (odds ratio [OR], 2.10; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.08–4.06) but not children, and this association increased with age. Among adults with H1N1pdm infection, obesity was associated with increased likelihood of symptoms (OR, 3.91; 95% CI, 1.55–9.87). For middle-aged and older adults with obesity there was also a slight increase in susceptibility to any H1N1pdm infection (OR, 1.20; 95% CI, .62–2.34). Body mass index (BMI) was also linearly associated with increased susceptibility to symptomatic H1N1pdm infection, primarily among middle-aged and older women (5-unit BMI increase OR, 1.40; 95% CI, 1.00–1.97). Obesity was not associated with increased H3N2 susceptibility or associated symptoms.

Conclusions

We found that, among adults, obesity is associated with susceptibility to H1N1pdm infection and with symptoms associated with H1N1pdm infection, but not with susceptibility to H3N2 infection or associated symptoms. These findings will help target prevention efforts and therapeutics to this high-risk population.

Keywords: influenza, household, obesity, susceptibility, sex difference

We found that, in adults, obesity is associated with increased susceptibility to H1N1pdm infection and this association increases with age. Obesity was not associated with H3N2 susceptibility.

Obesity has been recognized as a risk factor for increased influenza severity since the 2009 H1N1 pandemic [1, 2]. Since then, several studies have linked obesity to less severe influenza outcomes: a study of college-age participants with mild to moderate influenza A and B infections found that body mass index (BMI) was positively associated with increased viral load in fine and coarse aerosols, representing infection in the lung, while BMI was not significantly associated with viral load on nasopharyngeal swabs [3]. More recently, we showed that obesity is also associated with increased influenza A viral shedding duration among adults, even among adults with no or mild symptoms, suggesting that obesity may also influence influenza transmission [4].

The precise mechanism linking obesity to increased disease severity is not known, but many potential pathways exist. Molecular studies have shown that obesity increases proinflammatory and decreases anti-inflammatory cytokine levels as adipose tissue expands, leading to defective innate and adaptive immune function and chronic inflammation, which impairs host defenses [5]. Chronic inflammation increases with age and is associated with chronic diseases [6]. Obesity can also impair wound healing and lead to mechanical difficulties in breathing and increased oxygen requirements [5, 7]. The prevalence of obesity has been rising rapidly in all parts of the world [8, 9], and the contribution of obesity to the burden of influenza is not known but could potentially be substantial.

Here we investigate the effects of obesity on susceptibility to influenza infection, symptomatic infection, and the likelihood of symptoms (nonsevere outcomes) among participants with influenza virus infection. We used logistic regression models to assess the association of obesity and BMI on susceptibility to these influenza A outcomes.

METHODS

Ethics Statement

This study was approved by the institutional review boards at the Nicaraguan Ministry of Health and the University of Michigan. Informed consent or parental permission for minors was obtained from all participants. Assent was obtained for children aged 6 years and older.

Study Design

This work uses data from 2 household influenza transmission studies, the Household Influenza Transmission Study (HITS) and the Household Influenza Cohort Study (HICS), both conducted in the catchment area of the Health Center Sócrates Flores Vivas in Managua, Nicaragua. The HITS is a case-ascertained study of households that ran from 2012 to 2017 [10]. The HICS is a prospective cohort of approximately 330 households that are influenza free at baseline that started in May 2017. The HICS has a household transmission study embedded within the cohort that is activated when someone in a household tests positive for influenza. The embedded transmission study has the same design features as HITS, allowing data from the 2 studies to be combined.

Briefly, in both studies, influenza index cases were identified, and household members were then intensively monitored for infection for 10–15 days. In HITS, index influenza cases were recruited at the study health clinic and through the ongoing Nicaraguan Pediatric Cohort Study [11], and their household contacts were invited to enroll. Inclusion criteria for index cases in HITS were as follows: (1) a positive influenza QuickVue A+B rapid test, (2) experienced onset of acute respiratory infection (ARI) within the previous 48 hours, (3) live with at least 1 other household member, and (4) no household members had influenza-like illness (ILI) symptoms in the last 2 weeks. Similarly, once a household member enrolled in HICS becomes ill with rapid test– or real-time reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR)–confirmed influenza, the household enters the intensive monitoring period.

Four influenza seasonal epidemics are included in this analysis: October–December 2015, October–December 2016, July–November 2017, and September–December 2018.

Data Collection

Height and weight, blood samples, and household questionnaires were collected at enrollment (HITS: when index case identified; HICS: annual sampling at beginning of the influenza season). More detailed information on height and weight measurement and validation is available in the Supplementary Material. For both studies, after index cases were identified, study staff visited houses every 2–3 days for up to 10 to 15 days to collect nasal/oropharyngeal swabs and reported daily symptom diaries. Typically, 5 swabs are collected for each household member; however, if a participant presents with illness at the health center an additional swab was collected.

Obesity Definition

Obesity was defined as a BMI ≥30 kg/m2 for adults. BMI Z scores were calculated for children younger than 5 years based on the World Health Organization (WHO) growth reference standard and for children aged 5–17 years using a separate WHO growth reference [12, 13]. Obesity in children was defined as a BMI Z score greater than 2 SDs above the WHO reference population median for children aged 5–17 years and more than 3 SDs for children younger than 5 years.

Laboratory Testing and Influenza Definitions

Pooled nasal and oropharyngeal swabs were maintained in viral transport medium at 4°C, and blood samples were sent within 48 hours to the Nicaraguan National Virology Laboratory at the Nicaraguan Ministry of Health. Real-time RT-PCR was performed on RNA extracted from the swab samples per validated Centers for Disease Control and Prevention protocols for influenza H1N1pdm detection [14].

Influenza infection was defined as a participant with RT-PCR–confirmed influenza, regardless of symptoms. Symptomatic infection was defined as additionally having ILI, reported fever with a cough or sore throat.

Statistical Methods

Logistic regression models were used to investigate our main question of whether obesity (or BMI) is associated with influenza outcomes, separately for each subtype. We ran these models in children (0–17 years) and adults (18–85 years) separately and then stratified further to obtain group-specific odds ratios (ORs) for obesity. Age was further categorized in children based on the WHO reference group used to define obesity (0–4 and 5–17 years), and adults further categorized to obtain an approximately equal number in both groups (18–34 and 35–85 years). Confounders adjusted for in these age-stratified models were sex and a random effect for season. Additional detail on the modeling methods is located in the Supplementary Material.

To look at patterns by age, we also ran overall models, considering models that adjusted for age and sex, age squared (increased risk in the young and old), interactions of these variables with obesity, and random effects for season and household. We used the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) to choose the best model (Supplementary Figure 2), which adjusts for age and sex, has an obesity by age interaction term, and has random effects for season and household.

RESULTS

Study Population

Between 2015 and 2018, we enrolled 335 index cases with influenza A and 1506 of their household contacts (Supplementary Figure 1). Over 95% of people approached accepted screening to participate in HITS and HICS. Nearly 40% of the households had 5 or more people and 17% had 7 or more people. All age groups were roughly equally represented among household contacts, except for lower numbers of children under 5 (Table 1). Sex was balanced in children, but in adults there were fewer males than females (24% in adults aged 18–34, 30% in adults aged 35–85). Height and weight data were available for 1484 (98.5%) household contacts. The prevalence of obesity increased with age, from 2% in children aged 0–4 years to 53% in adults aged 35–85 years (Table 1). Throughout the intensive monitoring periods, 7780 swabs were collected (average: 4.2 per person), and 15 682 total person-days of symptoms were recorded (average: 8.6 days per person). Index cases presented to the study health clinic, on average, within 0.9 days of symptom onset (interquartile range, 0–2 days). Of the household contacts, 355 (24%) developed RT-PCR–confirmed influenza A infections matching the strain of their index case.

Table 1.

HITS and HICS Household Contact Participant Characteristics (2015–2018)

| Households With H1N1pdm | Households With H3N2 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Obese | Nonobese | Obese | Nonobese | Missinga | All | |

| All ages | ||||||

| n | 240 | 587 | 187 | 470 | 22 | 1506 |

| Male, n (%) | 60 (25.0) | 243 (41.4) | 46 (24.6) | 175 (37.2) | 11 (50.0) | 535 (35.5) |

| influenza A, n (%) | 47 (19.6) | 141 (24.0) | 32 (17.1) | 124 (26.4) | 6 (27.3) | 350 (23.2) |

| Age, n (%) | ||||||

| 0–4 years | 2 (0.8) | 99 (16.9) | 2 (1.1) | 85 (18.1) | 4 (18.2) | 192 (12.7) |

| 5–17 years | 30 (12.5) | 234 (39.9) | 18 (9.6) | 198 (42.1) | 8 (36.4) | 488 (32.4) |

| 18–34 years | 90 (37.5) | 143 (24.4) | 68 (36.4) | 105 (22.3) | 5 (22.7) | 411 (27.3) |

| 35–85 years | 118 (49.2) | 111 (18.9) | 99 (52.9) | 82 (17.4) | 5 (22.7) | 415 (27.6) |

| Age 0–4 years, n (%) | ||||||

| Male | 0 (0.0) | 52 (52.5) | 1 (50.0) | 41 (48.2) | 1 (25.0) | 95 (49.5) |

| influenza A | 2 (100.0) | 41 (41.4) | 0 (0.0) | 34 (40.0) | 3 (75.0) | 80 (41.7) |

| Age 5–17 years, n (%) | ||||||

| Male | 11 (36.7) | 113 (48.3) | 8 (44.4) | 81 (40.9) | 5 (62.5) | 218 (44.7) |

| influenza A | 7 (23.3) | 52 (22.2) | 3 (16.7) | 51 (25.8) | 1 (12.5) | 114 (23.4) |

| Age 18–34 years, n (%) | ||||||

| Male | 14 (15.6) | 41 (28.7) | 11 (16.2) | 28 (26.7) | 4 (80.0) | 98 (23.8) |

| influenza A | 13 (14.4) | 26 (18.2) | 17 (25.0) | 22 (21.0) | 1 (20.0) | 79 (19.2) |

| Age 35–85 years, n (%) | ||||||

| Male | 35 (29.7) | 37 (33.3) | 26 (26.3) | 25 (30.5) | 1 (20.0) | 124 (29.9) |

| influenza A | 25 (21.2) | 22 (19.8) | 12 (12.1) | 17 (20.7) | 1 (20.0) | 77 (18.6) |

Abbreviations: influenza A, real-time reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction–positive influenza A infection matching subtype of index case; HICS, Household Influenza Cohort Study; HITS, Household Influenza Transmission Study.

aMissing = Missing height and weight.

Obesity and Influenza A Susceptibility

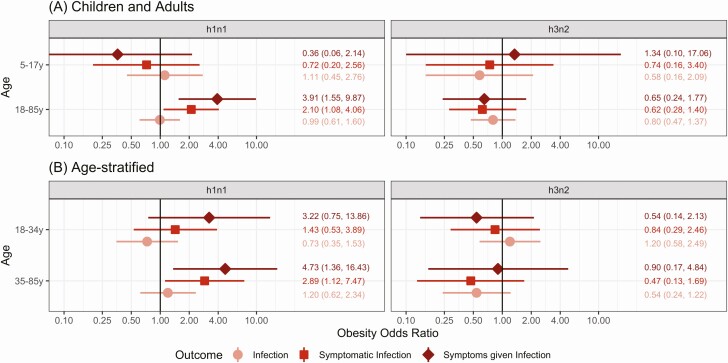

To examine the overall association of obesity with influenza A in adults and children we used mixed-effects logistic regression models adjusted for sex and season. Among adults (Figure 1A), those with obesity had twice the odds of symptomatic H1N1pdm infection (OR, 2.10; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.08–4.06) and nearly 4 times the odds of symptoms associated with H1N1pdm infection (OR, 3.91; 95% CI, 1.55–9.87). Of note, this association was not seen with H3N2. There was no association of obesity with H1N1pdm or H3N2 susceptibility in children aged 5–17 years. As there were only 4 household contacts under 5 years with obesity—2 who had H1N1pdm, 0 who had H3N2, and none who had ILI (Fisher’s exact tests: P = 1)— this age group was excluded. Models without random effects and with random effects for household are presented in Supplementary Figure 3.

Figure 1.

Obesity and H1N1pdm and H3N2 susceptibility stratified by age. Age-stratified ORs for obesity from models adjusted for sex are presented for H1N1pdm and H3N2. Age strata are (A) children and adults (ages 0–17 and 18–85 years) and (B) further subdivided (ages 5–17, 18–34, and 35–85 years). Obesity ORs for all infections are shown in pink, symptomatic infections are in red, and symptoms given infection are shown in dark-red/brown. Models are stratified by age and include terms for obese, sex, and random effects for season. Obesity ORs and 95% CIs are shown on each plot. Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; OR, odds ratio.

Obesity, Age, and Influenza A Susceptibility

To further examine the age dependency of the obesity and influenza susceptibility association, adults were stratified into 2 groups (Figure 1B). Among middle-aged and older adults (age 35–85 years) these associations were even stronger for H1N1pdm (OR for symptomatic infection, 2.89; 95% CI, 1.12–7.47; symptoms given infection, 4.73; 95% CI, 1.36–16.43) and no association was seen with H3N2.

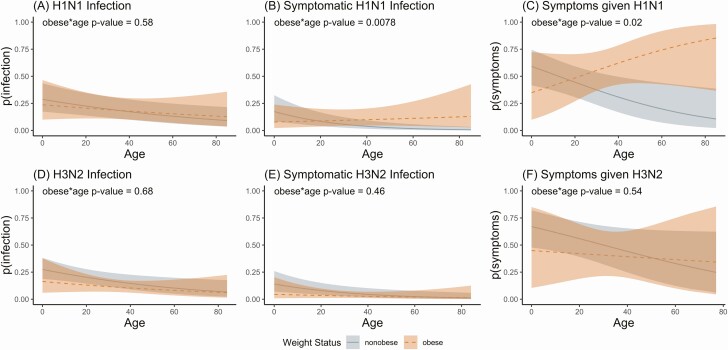

Overall mixed-effects logistic regression models adjusted for age, sex, random and effects for season and household and including an obesity by age interaction term showed a similar pattern. These models (Figure 2, Supplementary Table 1) show the associations of obesity starting in adulthood and increasing with age for susceptibility to symptomatic H1N1pdm infection (Figure 2B) (P value for obesity by age interaction = .0078) and symptoms given H1N1pdm infection (Figure 2C) (P value for interaction = .020). Again, no associations with obesity were seen for H3N2 susceptibility or symptoms.

Figure 2.

Obesity and H1N1pdm and H3N2 susceptibility. Curves show mixed-effects logistic regression model–predicted probabilities, for H1N1pdm (top, A–C) and H3N2 (bottom, D–F), of infection (A and D), symptomatic infection (B and E), and symptoms given infection (C and F), by age (x-axis) and weight status (obese = orange). Models include the following terms: obese, age, sex, random effects for household and season, and an age by obesity interaction term. P values for obesity × age interaction terms are shown on each plot.

To examine potential effects of imprinting, although underpowered, we also stratified the 35- to 85-year age group by influenza A subtype circulating at birth (Supplementary Figure 6) [15]. The direction of association with obesity and susceptibility to infection changed depending on strain circulating at birth (near or above 1 for both H1N1pdm and H3N2 for the cohorts that were not solely exposed to the subtype of interest; lower otherwise).

Obesity, Sex, and H1N1pdm Outcomes

To examine the effects of sex on the relationship between obesity we also stratified the models presented in Figures 1 and 2 by sex (Supplementary Figures 4 and 5), but the low number of men limited our ability to observe associations in men. For women, obesity was associated with increased symptomatic H1N1pdm infection (OR, 2.00; 95% CI, .91–4.38) and with H1N1pdm-associated symptoms (OR, 3.60; 95% CI, 1.31–9.91). These associations were again larger among women aged 35–85 years (OR for symptomatic infection, 2.62; 95% CI, .86–7.98; symptoms given infection, 4.09; 95% CI, 1.01–16.58). None of the associations for men were significant.

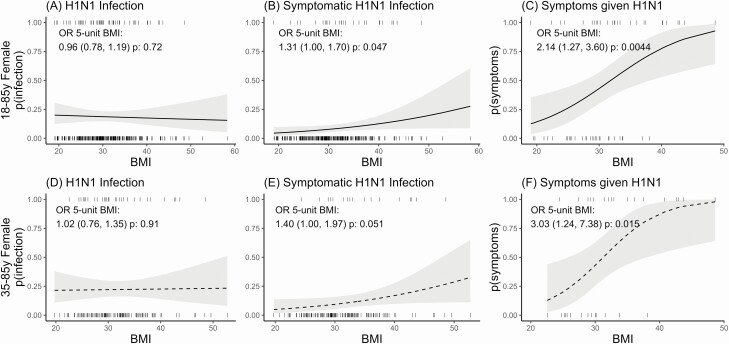

Body Mass Index and H1N1

To further examine the association between weight and influenza A H1N1pdm we examined the relationship between BMI and influenza. However, because men had a limited range of BMIs with few high values and there was a relatively low number of men in the study, we were unable to examine this association in men. For all women (aged 18–85 years) (Figure 3A–C), increasing BMI was significantly associated with increased symptomatic infection: for a 5-unit increase in BMI, they had 30% higher odds of symptomatic infection (OR, 1.31; 95% CI, 1.00–1.70) and twice the odds of symptoms given H1N1pdm infection (OR, 2.14; 95% CI, 1.27–3.60). These associations were again more pronounced among middle-aged and older women, who, for a 5-unit increase in BMI, had 40% higher odds of symptomatic H1N1pdm infection (OR, 1.40; 95% CI, 1.00–1.97) and 3 times higher odds of symptoms given infection (OR, 3.03; 95% CI, 1.24–7.38).

Figure 3.

BMI and H1N1pdm susceptibility in women. Curves show mixed-effects logistic regression model–predicted probabilities, for all women aged 18–85 years (top, A–C) and older women aged 35–85 years (bottom, D–F), of infection (A and D), symptomatic infection (B and E), and symptoms given infection (C and F), by BMI (x-axis). Models include the following terms: BMI and random effects for season. ORs and 95% confidence intervals for a 1-unit increase in BMI are shown on each plot. Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; OR, odds ratio.

DISCUSSION

In this study we found that obesity was associated with increased susceptibility to H1N1pdm infection, symptomatic H1N1pdm infection, and symptoms given H1N1pdm infection in adults. These associations increased with age. Interestingly, we found no associations for obesity and H3N2 infections.

Previous studies reporting associations of obesity and influenza outcomes in humans have primarily focused on severe outcomes such as death, hospitalization, and secondary pneumonia [1, 2, 16–20]. Our findings, coupled with the existing literature, demonstrate that obesity impacts the risk of influenza disease across the disease spectrum, including nonsevere outcomes. A strength of this study is that the efficient study design allowed us to identify influenza infections across individuals of all ages and to observe influenza infections that were mild enough to not require treatment or hospitalization. Mild influenza infections are less frequently studied but are critical to inform us about susceptibility to influenza infection and disease. Four prospective studies including adults looked at nonsevere outcomes, but none stratified by influenza (sub)type or sex. Three using symptom-based definitions found obesity associated with increased ILI [21–23]. One study of a health insurance database linked to reported laboratory-confirmed infections restricted to adults 45 and older found that obesity was associated with increased reported influenza infections [20].

Importantly, in our study, the effects of obesity on influenza A outcomes were specific to H1N1pdm and not to H3N2. This subtype-specific difference is interesting, and while the literature generally cites obesity as a risk factor for severe influenza without specifying type or subtype, existing studies have primarily reported on specific effects of H1N1pdm [1, 2, 16] or combined effects of all influenza types [19, 20, 24, 25]. These studies of combined influenza types found some evidence for increased hospitalization and mortality for seasonal influenza [19, 20, 24, 25]. One study of a season in which H3N2 predominated found no increased severity among hospitalized adults [26]. Thus, our findings are in line with the existing epidemiologic evidence. Possible explanations for the subtype difference in obesity associations include (1) biological differences between virus subtypes or (2) differences in immune response. It is possible that obesity could interfere with the immune system’s ability to generate new antibodies [27] but not have as strong an effect when pre-existing antibodies are present. It is possible that obesity affected initial response to H1N1 in 2009 or the ability to maintain immunity [27, 28]. In support of the immune-response hypothesis, 1 study found that obesity was associated with vaccine seroconversion to H3N2 but not H1N1 [29]. The association of obesity and influenza susceptibility may depend on early-life exposure history [15], but our study was underpowered to assess this variation.

There are many mechanisms through which obesity may act to increase susceptibility to and severity of influenza infections. Two reviews [5, 30] and a book chapter [27] summarize some of the pathways; many are identified based on mouse studies. Briefly, obesity can affect lung function, reducing lung volume and increasing the respiratory rate [7]; it can impair wound healing in the lungs [31]; and it leads to production of more proinflammatory and less anti-inflammatory cytokines, leading to systemic inflammation that can ultimately impair innate and adaptive immune responses [5, 30]. In the innate immune system, cytokines, natural killer cells, macrophages, and dendritic cells have been shown to be affected by obesity [5, 30, 32, 33]. T cells and the adaptive immune system have also been shown to be reduced and less effective under obese conditions [34–38].

Reported associations of obesity and influenza-associated death have been larger than associations with less severe outcomes [2], and we also found a larger association for H1N1pdm infection with symptoms versus all H1N1pdm infections. One possible explanation for this is that, in addition to pathways through which obesity acts to affect susceptibility, there are additional pathways to increase severity (eg, increased damage, impaired wound healing) compounding the effects of obesity [5, 31]. Further, that the association increased with age fits with our understanding that obesity can affect influenza outcomes through chronic inflammation, the effects of which increase over time [5].

Surprisingly, women had stronger associations with obesity and H1N1pdm outcomes than men, and it appears that most of the associations we observed were driven by the associations in women, although this could be due to the low adult male participation. We could not find any other studies that examined the association of obesity and influenza susceptibility by sex, although some published studies support sex differences. One study reported somewhat higher hazard ratios for BMI and influenza notifications among women than men [20], and pregnancy was noted as a risk factor for hospitalization and complications during the 2009 pandemic [30].

There is, however, some knowledge of sex differences for influenza outcomes: women mount stronger antibody and humoral immune responses to vaccination than men and pandemic influenza outcomes are generally worse for women [39, 40]. Worse outcomes in females are shown in mouse studies to correspond to increased cytokine and chemokine production in lungs along with greater immunopathology [39]. Sex hormones also affect levels of inflammatory cytokines and chemokines, and influenza infection in mice has been shown to interrupt the estrous cycle, keeping estradiol levels low and consequently leading to excessive inflammation, which can lead to greater pathogenesis [39]. Additionally, studies have also shown that sex and sex hormones play a role in regulating obesity-induced inflammation [41]. Future studies, including molecular and immunological studies, should consider the effect of sex on the relationship between obesity and influenza infection and disease.

One limitation of this study is that we had lower adult male participation, which limited our ability to observe differences by obesity and BMI in men. Another limitation is that we only collected swabs to test for virus every 2–3 days, so we may not have detected infections that only shed virus briefly. Because of this, we may be limited in our ability to discern whether adults with obesity are more susceptible to H1N1pdm infection. Our use of BMI as a measure of adiposity to define obesity is a further limitation: BMI is good at correctly identifying individuals with very high BMIs as having excess adiposity but less good at middle-range values of BMI. However, our analysis with BMI as a continuous predictor does indicate that higher BMIs are associated with increased susceptibility to H1N1pdm outcomes.

The merits of studying obesity as a causal risk factor of mortality have been debated by epidemiologists, with some arguing that one should instead focus on modifying behaviors, while others argue that causal health consequences are still worth knowing [42, 43]. For our current work with influenza, we believe there is merit to studying obesity rather than other modifiable behaviors (which will likely modify effects of obesity) because there are interventions available to help people with obesity reduce their influenza burden (eg, vaccines, antivirals, hand washing, avoiding likely exposure situations).

These findings extend our understanding of the connection between obesity and infectious diseases, indicating that the extent of the influence of obesity is larger than previously understood. Obesity is not only associated with influenza-related severe outcomes and death but also with the milder outcomes of susceptibility, symptoms, and, as we previously showed, viral shedding [4]. With the steadily increasing worldwide obesity epidemic, and given our findings, there is a potential for substantially increased influenza burden due to obesity, and also a potentially increased burden of other infectious diseases [44, 45]. Physicians should be informed of the importance of obesity as a risk factor for influenza, and preventive and therapeutic measures should consider targeting obesity as an important upstream risk factor. Future efforts should focus on identifying the pathways through which obesity increases the risk of influenza virus infection and outcomes, and how this varies by sex, to better inform the design of interventions and therapeutics.

Supplementary Data

Supplementary materials are available at Clinical Infectious Diseases online. Consisting of data provided by the authors to benefit the reader, the posted materials are not copyedited and are the sole responsibility of the authors, so questions or comments should be addressed to the corresponding author.

Notes

Acknowledgments. The authors thank the many dedicated study personnel in Nicaragua at the Centro Nacional de Diagnóstico y Referencia and the Sócrates Flores Vivas Health Center.

Financial support. This work was supported by the National Institute for Allergy and Infectious Disease (grant numbers U01 AI088654 and R01 AI120997 and contract number HHSN272201400006C).

Potential conflicts of interest. A. G. reports consulting fees from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, outside the submitted work. All other authors report no potential conflicts. All authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. Conflicts that the editors consider relevant to the content of the manuscript have been disclosed.

References

- 1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Intensive-care patients with severe novel influenza A (H1N1) virus infection—Michigan, June 2009. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2009; 58:749–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Van Kerkhove MD, Vandemaele KA, Shinde V, et al. Risk factors for severe outcomes following 2009 influenza A (H1N1) infection: a global pooled analysis. PLoS Med 2011; 8:e1001053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Yan J, Grantham M, Pantelic J, et al. ; EMIT Consortium . Infectious virus in exhaled breath of symptomatic seasonal influenza cases from a college community. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2018; 115:1081–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Maier HE, Lopez R, Sanchez N, et al. Obesity increases the duration of influenza A virus shedding in adults. J Infect Dis 2018; 218:1378–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Mancuso P. Obesity and respiratory infections: does excess adiposity weigh down host defense? Pulm Pharmacol Ther 2013; 26:412–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Gibson DC, Gubbels Bupp MR. Sex and the aging immune system. In: Ram JL, Conn PM, eds. Conn’s handbook of models for human aging. 2nd ed. London: Elsevier, 2018:803–30. Available at: 10.1016/B978-0-12-811353-0.00059-2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7. McClean KM, Kee F, Young IS, Elborn JS. Obesity and the lung: 1. Epidemiology. Thorax 2008; 63:649–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. World Health Organization. Obesity and overweight. Available at: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/obesity-and-overweight. Accessed 29 July 2019.

- 9. FAO; IFAD; UNICEF; WFP; WHO. The state of food security and nutrition in the world 2017. Building resilience for food and food security. Rome, Italy: FAO, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Gordon A, Tsang TK, Cowling BJ, et al. Influenza transmission dynamics in urban households, Managua, Nicaragua, 2012-2014. Emerg Infect Dis 2018; 24:1882–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Gordon A, Kuan G, Aviles W, et al. The Nicaraguan pediatric influenza cohort study: design, methods, use of technology, and compliance. BMC Infect Dis 2015; 15:504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. WHO Multicentre Growth Reference Study Group. WHO child growth standards: length/height-for-age, weight-for-age, weight-for-length, weight-for-height and body mass index-for-age; Methods and development. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 13. de Onis M, Onyango AW, Borghi E, Siyam A, Nishida C, Siekmann J. Development of a WHO growth reference for school-aged children and adolescents. Bull World Health Organ 2007; 85:660–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Dawood FS, Jain S, Finelli L, et al. ; Novel Swine-Origin Influenza A (H1N1) Virus Investigation Team . Emergence of a novel swine-origin influenza A (H1N1) virus in humans. N Engl J Med 2009; 360:2605–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Gostic KM, Ambrose M, Worobey M, Lloyd-Smith JO. Potent protection against H5N1 and H7N9 influenza via childhood hemagglutinin imprinting. Science 2016; 354:722–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Fuhrman C, Bonmarin I, Paty AC, et al. Severe hospitalised 2009 pandemic influenza A(H1N1) cases in France, 1 July-15 November 2009. Euro Surveill 2010; 15:17-21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Cocoros NM, Lash TL, DeMaria A Jr, Klompas M. Obesity as a risk factor for severe influenza-like illness. Influenza Other Respir Viruses 2014; 8:25–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Martin ET, Archer C, McRoberts J, et al. Epidemiology of severe influenza outcomes among adult patients with obesity in Detroit, Michigan, 2011. Influenza Other Respir Viruses 2013; 7:1004–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Yang L, Chan KP, Lee RS, et al. Obesity and influenza associated mortality: evidence from an elderly cohort in Hong Kong. Prev Med 2013; 56:118–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Karki S, Muscatello DJ, Banks E, MacIntyre CR, McIntyre P, Liu B. Association between body mass index and laboratory-confirmed influenza in middle aged and older adults: a prospective cohort study. Int J Obes (Lond) 2018; 42:1480–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Muscatello DJ, Barr M, Thackway SV, Macintyre CR. Epidemiology of influenza-like illness during Pandemic (H1N1) 2009, New South Wales, Australia. Emerg Infect Dis 2011; 17:1240–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Neidich SD, Green WD, Rebeles J, et al. Increased risk of influenza among vaccinated adults who are obese. Int J Obes (Lond) 2017; 41:1324–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Guerrisi C, Ecollan M, Souty C, et al. Factors associated with influenza-like-illness: a crowdsourced cohort study from 2012/13 to 2017/18. BMC Public Health 2019; 19:879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kwong JC, Campitelli MA, Rosella LC. Obesity and respiratory hospitalizations during influenza seasons in Ontario, Canada: a cohort study. Clin Infect Dis 2011; 53:413–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Zhou Y, Cowling BJ, Wu P, et al. Adiposity and influenza-associated respiratory mortality: a cohort study. Clin Infect Dis 2015; 60:e49–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Braun ES, Crawford FW, Desai MM, et al. Obesity not associated with severity among hospitalized adults with seasonal influenza virus infection. Infection 2015; 43:569–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Karlsson EA, Milner JJ, Green WD, Rebeles J, Schultz-Cherry S, Beck MA. Influence of obesity on the response to influenza infection and vaccination. Mech Manifest Obes Lung Dis 2019:227–59. Available at: 10.1016/B978-0-12-813553-2.00010-5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Sheridan PA, Paich HA, Handy J, et al. Obesity is associated with impaired immune response to influenza vaccination in humans. Int J Obes (Lond) 2012; 36:1072–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Talbot HK, Coleman LA, Crimin K, et al. Association between obesity and vulnerability and serologic response to influenza vaccination in older adults. Vaccine 2012; 30:3937–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Karlsson EA, Marcelin G, Webby RJ, Schultz-Cherry S. Review on the impact of pregnancy and obesity on influenza virus infection. Influenza Other Respir Viruses 2012; 6:449–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. O’Brien KB, Vogel P, Duan S, et al. Impaired wound healing predisposes obese mice to severe influenza virus infection. J Infect Dis 2012; 205:252–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Smith AG, Sheridan PA, Harp JB, Beck MA. Diet-induced obese mice have increased mortality and altered immune responses when infected with influenza virus. J Nutr 2007; 137:1236–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Smith AG, Sheridan PA, Tseng RJ, Sheridan JF, Beck MA. Selective impairment in dendritic cell function and altered antigen-specific CD8+ T-cell responses in diet-induced obese mice infected with influenza virus. Immunology 2009; 126:268–79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Karlsson EA, Sheridan PA, Beck MA. Diet-induced obesity impairs the T cell memory response to influenza virus infection. J Immunol 2010; 184:3127–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Karlsson EA, Sheridan PA, Beck MA. Diet-induced obesity in mice reduces the maintenance of influenza-specific CD8+ memory T cells. J Nutr 2010; 140:1691–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Nieman DC, Henson DA, Nehlsen-Cannarella SL, et al. Influence of obesity on immune function. J Am Diet Assoc 1999; 99:294–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. O’Rourke RW, Kay T, Scholz MH, et al. Alterations in T-cell subset frequency in peripheral blood in obesity. Obes Surg 2005; 15:1463–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Rebeles J, Green WD, Alwarawrah Y, et al. Obesity-induced changes in T-cell metabolism are associated with impaired memory T-cell response to influenza and are not reversed with weight loss. J Infect Dis 2019; 219:1652–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Klein SL, Hodgson A, Robinson DP. Mechanisms of sex disparities in influenza pathogenesis. J Leukoc Biol 2012; 92:67–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Morgan R, Klein SL. The intersection of sex and gender in the treatment of influenza. Curr Opin Virol 2019; 35:35–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Varghese M, Griffin C, Singer K. The role of sex and sex hormones in regulating obesity-induced inflammation. In: Mauvais-Jarvis F, ed, Sex and gender factors affecting metabolic homeostasis, diabetes and obesity. Vol. 1043. Switzerland: Springer International Publishing, 2017. Available at: https://link.springer.com/book/10.1007%2F978-3-319-70178-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Hernán MA, Taubman SL. Does obesity shorten life? The importance of well-defined interventions to answer causal questions. Int J Obes (Lond) 2008; 32(Suppl 3):S8–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Pearl J. Does obesity shorten life? Or is it the soda? On non-manipulable causes. J Causal Inference 2018; 6:1–7. [Google Scholar]

- 44. Maruvada P, Leone V, Kaplan LM, Chang EB. The human microbiome and obesity: moving beyond associations. Cell Host Microbe 2017; 22:589–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Nyitray AG, Peng F, Day RS, et al. The association between body mass index and anal canal human papillomavirus prevalence and persistence: the HIM study. Hum Vaccin Immunother 2019; 15:1911–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.