Abstract

Background:

Rotational thromboelastometry (ROTEM) has been commonly used to assess the viscoelastic properties of the blood clotting process in the clinic for patients with a hemostatic or prothrombotic disorder.

Objective:

To evaluate the capability of ROTEM in assessing hemostatic properties in whole blood from various mouse models with genetic bleeding or clotting disease and the effect of factor VIII (FVIII) therapeutics in FVIIInull mice.

Methods:

Mice with a genetic deficiency in either a coagulation factor or a platelet glycoprotein were used in this study. The properties of platelet- or plasma-FVIII were also assessed. Citrated blood from mice was recalcified and used for ROTEM analysis.

Results:

We found that blood collected from the vena cava could generate reliable results from ROTEM analysis, but not blood collected from the tail vein, retro-orbital plexus, or submandibular vein. Age and sex did not significantly affect the hemostatic properties determined by ROTEM analysis. Clotting time (CT) and clot formation time (CFT) were significantly prolonged in FVIIInull (5- and 9-fold, respectively) and FIXnull (4- and 5.7-fold, respectively) mice compared to wild-type (WT)-C57BL/6J mice. Platelet glycoprotein (GP)IIIanull mice had significantly prolonged CFT (8.4-fold) compared to WT-C57BL/6J mice. CT and CFT in factor V (FV) Leiden mice were significantly shortened with an increased α-angle compared to WT-C57BL/6J mice. Using ROTEM analysis, we showed that FVIII expressed in platelets or infused into whole blood restored hemostasis of FVIIInull mice in a dose-dependent manner.

Conclusion:

ROTEM is a reliable and sensitive assay for assessing therapeutics on hemostatic properties in mouse models with a bleeding or clotting disorder.

Keywords: bleeding, clotting, mouse model, rotational thromboelastometry

1 |. INTRODUCTION

Rotational thromboelastometry (ROTEM) has been commonly used to assess the viscoelastic properties of the specific blood clotting process in the clinic for patients with abnormalities of blood coagulation.1–3 The ROTEM test is a methodology based on thromboelastography (TEG) that can reflect the interactions between coagulation factors and platelets.4–7 It can be used to assess the qualitative and quantitative properties of the onset of coagulation, platelet aggregation, clot firmness, and fibrinolysis.1 Although TEG was first described six decades ago,4 its application was limited at first due to the complexity of the analysis. With advanced technologies, several versions of TEG have been developed to improve the efficiency and reliability of the test.8–10

ROTEM was designed to rotate the pin instead of the cup. It has been shown that classical nonactivated ROTEM (NATEM, also known as native ROTEM), in which no additional reagent/substrate is needed except CaCl2 to recalcify citrated whole blood, is more sensitive to coagulation changes than activated ROTEM methods, EXTEM and INTEM.11 Several measurement parameters in ROTEM, including clotting time (CT), clot formation time (CFT), and alpha (α)-angle, are used to assess the viscoelastic properties of the coagulation process.12 The CT in the ROTEM assay is defined as the time from the beginning of the test to reach 2 mm in amplitude. It reflects the speed of fibrin formation, which could be influenced by the concentrations of clotting factors and anticoagulants. The CFT is the time it takes an amplitude of 2 mm to reach 20 mm. The α-angle is the angle between the baseline and a tangent to the clotting curve through the 2-mm amplitude point. Both CFT and α-angle denote the kinetics of clot formation, which can be affected by platelet function or level, fibrinogen level, and fibrin polymerization, as well as coagulation factors.13–16

ROTEM is a modification of TEG with some advantages for small animal model studies. ROTEM analysis requires less blood volume for the test and has the capacity to run more samples at the same time than TEG does.17 These advantages make ROTEM analysis attractive for studying hemostasis and abnormalities of blood coagulation in mouse models as blood volume could be a limitation in small animals. Mouse models have been widely used to study hemostasis and abnormalities of blood coagulation as well as the efficacy and safety of new therapeutics for bleeding and clotting disorders. While there are various assays being used to study blood coagulation in mouse models, many factors, including how blood samples are collected and handled, can cause experimental variabilities in the tests.18

In the current study, we examined the feasibility of ROTEM analysis to assess the dynamics of clot formation and the strength of the formed clot in whole blood from various mouse models with a deficiency of either a blood coagulation factor (factor VIII [FVIII]null, factor IX [FIX]null, or von Willebrand factor [VWF]null) or platelet glycoprotein (GPIbαnull or GPIIIanull), or with prothrombotic factor V (FV) Leiden. We investigated how blood collection impacts the variabilities of the assay and whether age and/or sex impact the hemostatic properties in whole blood determined by ROTEM analysis. We also evaluated the sensitivity and effectiveness of various levels of plasma- or platelet-derived FVIII in restoring the functional hemostatic properties in FVIIInull mice using ROTEM analysis of whole blood.

2 |. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1 |. Mice

Mice used in this study were in the C57BL/6J background except for 2bF8 mice, which were in a B6/129S mixed genetic background. FVIII knockout (FVIIInull) mice, which were generated via a targeted disruption of exon 17 of the F8 gene with undetectable FVIII in the plasma,19 were a kind gift from H. Kazazian (University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine) and the colony was maintained in our facility. FIX knockout (FIXnull) mice, which were generated via a targeted disruption of the promoter through exon 3 of the F9 gene,20 were purchased from the Jackson Laboratory and the colony was maintained in our facility. Glycoprotein (GP) Ibα knockout (GPIbαnull), which were generated by removing the GPIbα polypeptide coding sequence (GPIbαnull),21 were a generous gift from J. Ware (the University of Arkansas for Medical Science) and the colony was maintained in our facility. Integrin GPIIIa knockout (GPIIIanull, also named β3−/−) mice, which were generated via a targeted disruption of exon 1 and 2 of the β3-integrin gene,22 were kindly provided by R. O. Hynes (Howard Hughes Medical Institute) and bred in-house.23 VWF knockout (VWFnull) mice were purchased from the Jackson Laboratory and bred in-house. FVL (Q/Q) mice were derived from the originally described colony24 and bred in-house. BALB/cJ and 129P3/J wild-type mice were purchased from the Jackson Laboratory. 2bF8 mice were either transgenic animals with platelet-specific human B-domain deleted FVIII expression generated by lentiviral transgenesis25 or FVIIInull mice that received 2bF8 lentivirus transduction of hematopoietic stem cells followed by transplantation.26 All mice were maintained in pathogen-free microisolator cages at the animal facilities operated by the Medical College of Wisconsin. Animal studies were performed according to protocols approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the Medical College of Wisconsin. Isoflurane or ketamine was used for anesthesia.

2.2 |. Blood sample collection

Blood samples were collected via four routes: (1) tail blood vessels, (2) the submandibular vein, (3) retro-orbital venous plexus, and (4) the inferior vena cava (IVC). For the tail bleed (TB), mice were anesthetized and approximately 2 millimeters of the tail tip was excised using a sterile scalpel blade. The wounded tail tip was placed into a microcentrifuge tube containing 12 μl of 3.8% sodium citrate anticoagulant. The collection tube was premarked with a line to indicate the volume of 120 μl. The tail was held gently with one hand and stroked between the thumb and forefinger with the other hand to help maintain the flow of blood. A total of 120 μl of whole blood was collected for the ROTEM assay and the wounded tail tip was cauterized after blood collection. For the submandibular bleed (SB), a 28-gauge lancet needle was used to puncture the vein. The resulting blood flow was collected using a hematocrit tube containing sodium citrate anticoagulant solution. Direct pressure was applied to the puncture site until the bleeding stopped. For the eye bleed (EB), a pipette tip that was premarked for a volume of 120 μl and loaded with 12 μl of 3.8% sodium citrate was used to collect the desired amount of blood from the retro-orbital venous plexus of the anesthetized animal. Blood was transferred into a 0.6 ml microcentrifuge tube and gently mixed. For blood collection from the IVC, which is a terminal blood collection, an incision was made through the abdominal wall of the anesthetized animal to expose the internal body cavity. Organs were gently displaced to expose the vena cava vessel and approximately 500 μl of blood was drawn into a 1 ml syringe that was rinsed with 3.8% sodium citrate anticoagulant using a 25-gauge needle and loaded with 50 μl of sodium citrate. Blood was transferred into 1.5 ml microcentrifuge tube immediately and gently mixed.

2.3 |. Rotational thromboelastometry analysis of mouse whole blood

The NATEM assay was performed to assess the coagulation process in recalcified citrated mouse whole blood following the protocol provided by the manufacturer. The conventional ROTEM cup (ProCup) was used in most of the tests unless otherwise specified. The MiniCup was used only for comparison of blood collection methodology studies or for multiple tests from the same sample (i.e., FVIIInull blood with various levels of recombinant human B-domain deleted FVIII [rhFVIII] added). For the assay using the conventional ROTEM cup, 21 μl of 0.2 mol L−1 CaCl2 and 300 μl of citrated whole blood were loaded into the bottom of a conventional cup that was placed in the 37°C pre-warmed holder. For the assay using the MiniCup, 7 μl of 0.2 mol L−1 CaCl2 and 105 μl of citrated whole blood were loaded into the bottom of a MiniCup. All samples were manually loaded. Citrated blood samples were gently mixed with CaCl2 in the cup by pipetting up and down once. Samples were tested using ROTEM® delta (Instrumentation Laboratory). Samples were run for 1 h. Data were recorded as 3600 s if CT and/or CFT did not reach the threshold recorded by ROTEM by the end of the 1-h test. Of note, our 1-h NATEM assay is not designed to evaluate fibrinolysis, which may require a longer time or an additional reagent using other test assays, such as FIBTEM.27

2.4 |. Statistical analysis

Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD). The one-way analysis of variance was used for statistical comparisons of data from three or more groups. The Student’s t-test was used to compare data from two groups. The differences in the incidences of failed amplitude amplification and α-angle development between two experimental groups were analyzed by Fisher’s exact test. The relationship between platelet--FVIII expression levels and clotting time was evaluated by Pearson’s r correlation. Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism 7 (GraphPad Software) and SigmaPlot 14.0 (Systat Software, Inc.). For all comparisons, a value of P < .05 was considered statistically significant.

3 |. RESULTS

3.1 |. The impact of blood collection on ROTEM

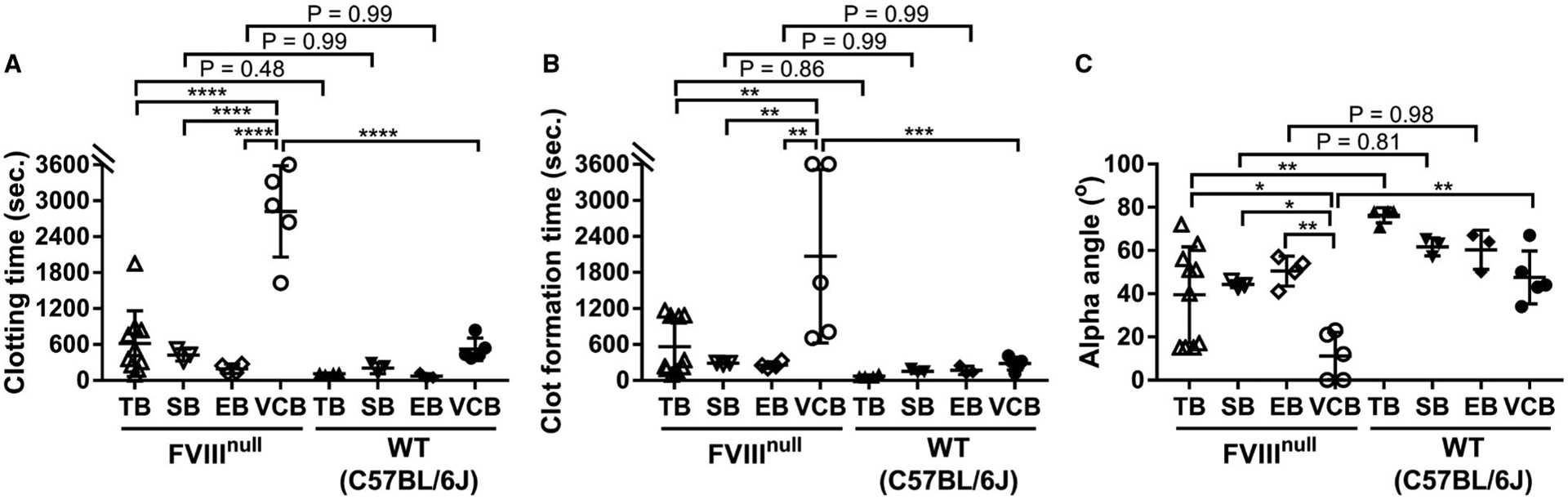

Because ROTEM is capable of analyzing a small sample volume (105 μl), we tested various routes of blood collection, including tail bleeding, retro-orbital (eye) bleeding, submandibular bleeding, and vena cava blood draw, on whole blood hemostasis analyzed by ROTEM. As shown in Figure 1A, when blood was collected from the IVC, the whole blood CT in the FVIIInull group was significantly longer than in the wild-type (WT) group (P < .0001). However, all three parameters, including CT, CFT, and α-angle, were significantly impacted when samples were collected from tail bleed, submandibular bleed, or eye bleed compared to the IVC blood draw. For hemophilia A (FVIIInull) mice, whole blood clotting times from the tail bleed, submandibular bleed, and eye bleed groups were significantly shorter than that obtained from the IVC group (Figure 1A). For WT mice, whole blood CT in the tail bleed group was also significantly shorter than in the IVC group. Of note, when blood samples were collected via TB, SB, or EB, there was no statistically significant difference in whole blood CT through ROTEM analysis between the FVIIInull and WT groups, although the distributions of CT data are different between the two groups in the TB route, demonstrating that the inappropriate sampling route renders the data inconsistent (Figure 1A).

FIGURE 1.

The impact of the method of blood collection on the parameters determined by rotational thromboelastometry (ROTEM). Blood samples were collected via tail bleed (TB), submandibular bleed (SB), eye bleed (EB), or inferior vena cava (IVC) blood draw from factor VIII knockout (FVIIInull) or wild-type (WT)-C57BL/6J mice; 3.8% sodium citrate was used as an anticoagulant at 1:10 (vol/vol). The hemostatic properties of blood samples were analyzed by ROTEM using the MiniCup, in which 7 μl 0.2 M CaCl2 was loaded to the bottom, followed by adding 105 μl of citrated blood and parameters were recorded for 1 h. A, Clotting time. B, Clot formation time. C, Alpha angle (α-angle). *P < .05. **P< .01. ***P < .001. ****P < .0001

Similar to the results of CT, when blood samples were collected from the IVC, CFT in the FVIIInull group was significantly longer than in the WT group. However, when blood samples were collected via either TB, SB, or EB from FVIIInull, CFT was significantly shorter compared to that obtained from the IVC group from the same colony of animals, dampening the difference between the FVIIInull and WT groups (Figure 1B). When blood samples were collected from the IVC, α-angle in the FVIIInull group was significantly smaller than in the WT group. However, when blood samples were collected via TB, SB, or EB from FVIIInull mice, α-angle was significantly larger compared to that obtained from the IVC group from the same colony of animals. The difference between the FVIIInull and WT groups was diminished in SB and EB routes (Figure 1C). These results suggest that sample collection through TB, EB, or SB is not suitable for ROTEM analysis, indicating that sample quality is critical for reliable results in this assay.

3.2 |. ROTEM analysis of whole blood from various coagulation defective mouse models

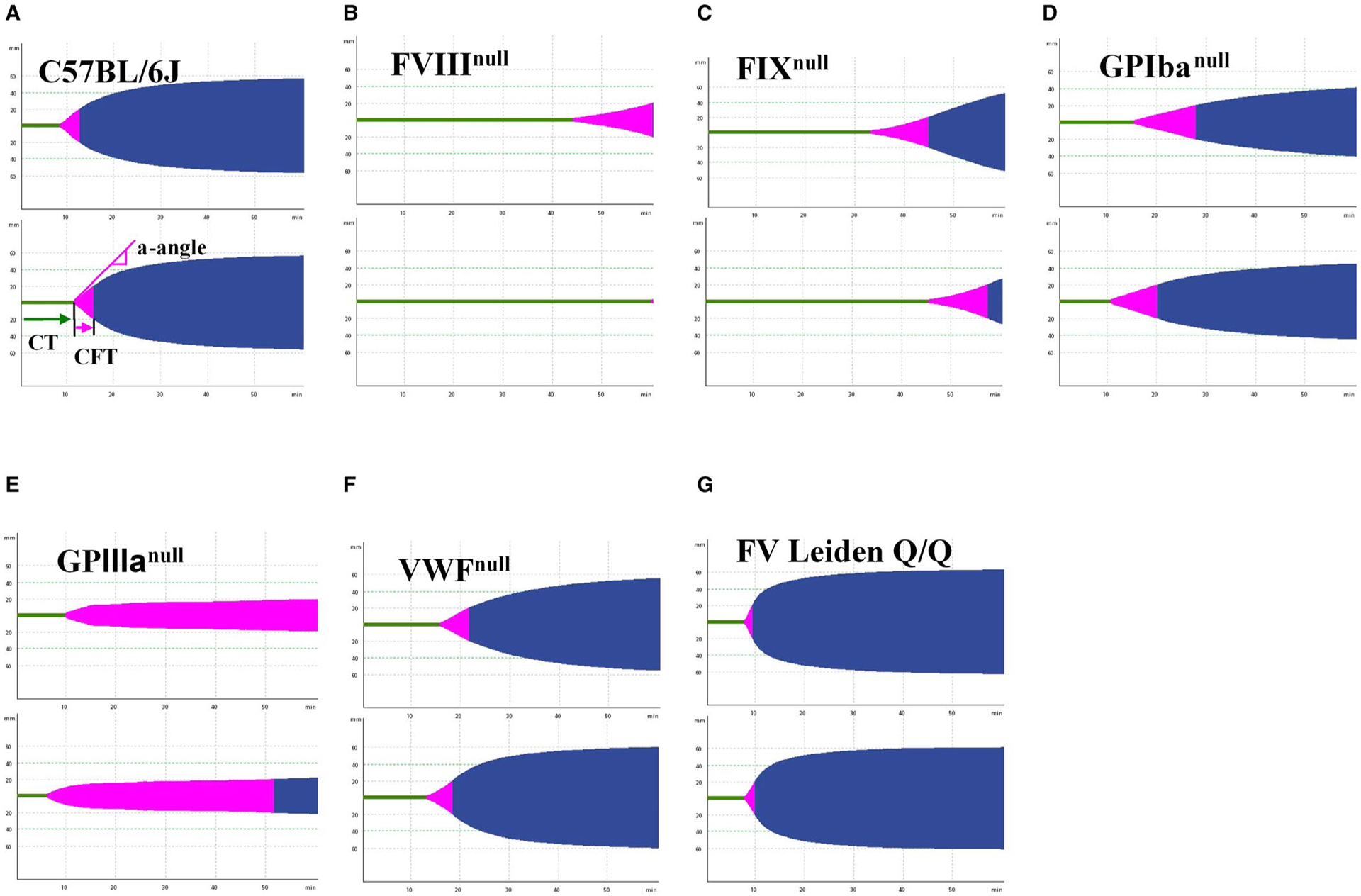

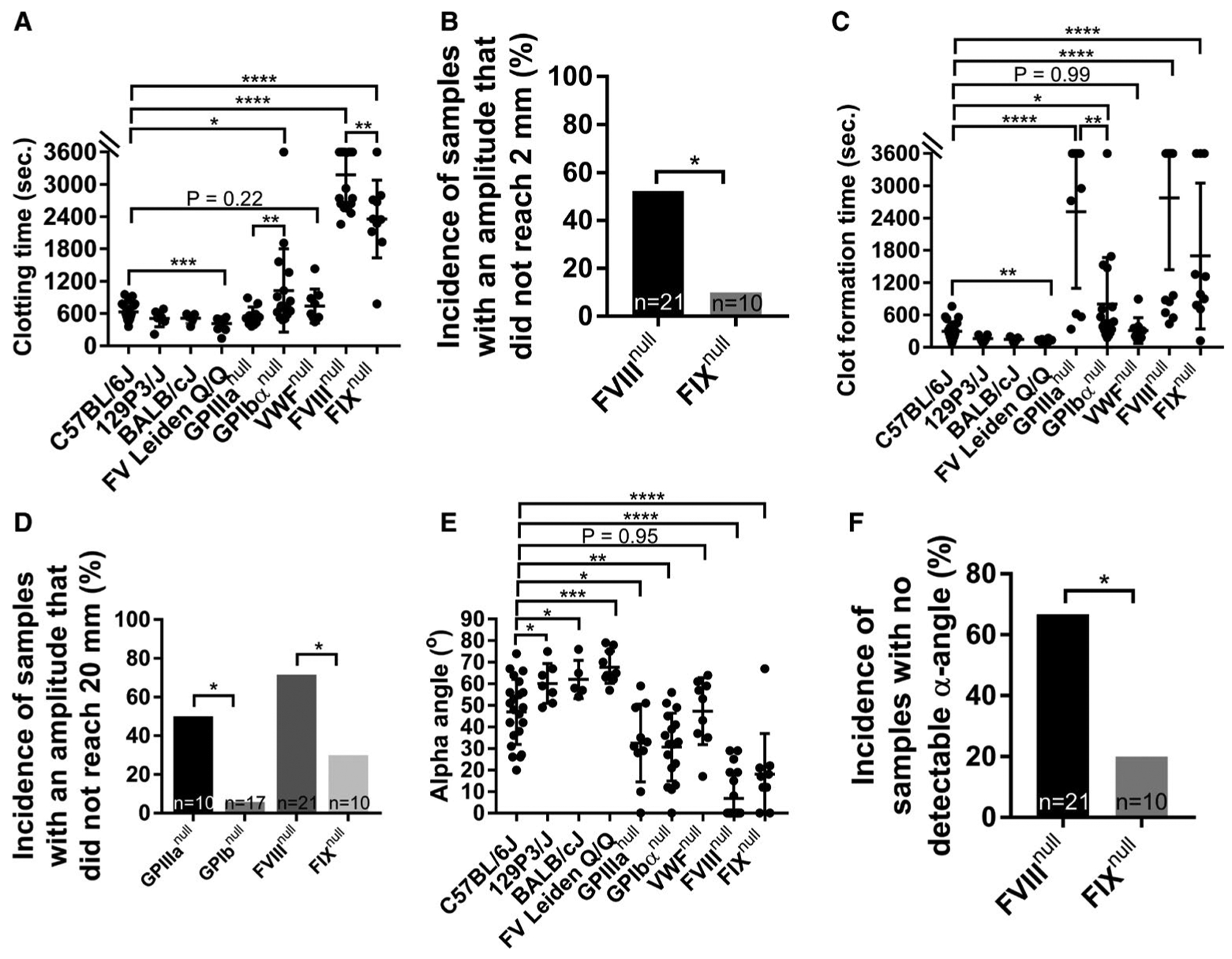

To evaluate the potential application of ROTEM analysis of whole blood in hemostatic and thrombotic disease mouse models, we performed the NATEM test using the conventional ROTEM cup (300 μl) on whole blood samples collected from the IVC from various colonies of animals. Representative TEMograms from WT C57BL/6J, FVIIInull, FIXnull, GPIbαnull, GPIIIanull, VWFnull, and FV Leiden Q/Q mice are shown in Figure 2A–G. The whole blood CT from WT mice in a C57BL/6J background was 632 ± 158 s (n = 22), which was not significantly different compared to those obtained from WT animals in a 129P3/J (509 ± 151 s, n = 7) or BALB/cJ (513 ± 94 s, n = 5) background, GPIIIanull mice (549 ± 173 s, n = 10), or VWFnull mice (739 ± 314 s, n = 9; Figure 3A). The whole blood CT in the FV Leiden Q/Q group (418 ± 124 s, n = 10) was significantly shorter than in the WT-C57BL/6J group (P < .001). The whole blood CTs from the mGPIbαnull (1029 ± 771 s, n = 17), FVIIInull (3178 ± 513 s, n = 21), and FIXnull (2535 ± 491 s, n = 9) groups were significantly longer than from the WT-C57BL/6J group (Figure 3A).

FIGURE 2.

Representative graphical images of thromboelastometry from various mouse colonies. Blood samples were collected from mice via inferior vena cava (IVC) blood draw with 3.8% sodium citrate as an anticoagulant (1:10 [vol/vol]). Whole blood samples were run using the rotational thromboelastometry (ROTEM) ProCup/pin for 60 min, and graphical images were generated. Representative TEMograms from two animals in each strain/model are shown. A, Wild-type C57BL/6J mice. B, Factor VIII knockout (FVIIInull) mice. C, Factor IX knockout (FIXnull) mice. D, Platelet glycoprotein Ibα knockout (GPIbαnull) mice. E, Platelet glycoprotein IIIa knockout (GPIIIanull) mice. F, von Willebrand factor knockout (VWFnull) mice. G, Factor V (FV) Leiden Q/Q mice

FIGURE 3.

Rotational thromboelastometry (ROTEM) analysis of hemostatic properties in various mouse colonies with bleeding or clotting disorders. Blood samples were collected via inferior vena cava (IVC) blood draw with 3.8% sodium citrate as an anticoagulant (1:10 [vol/vol]). The hemostatic properties of blood samples were determined by ROTEM using the ProCup, in which 21 μl 0.2 M CaCl2 was loaded to the bottom followed by adding 300 μl of citrated blood and parameters were recorded. Samples were run for 1 h. A, Clotting times from various mouse colonies. B, The incidence of samples with an amplitude that did not reach 2 mm, the threshold of clotting time recorded by ROTEM, in whole blood of factor VIII knockout (FVIIInull) and factor IX knockout (FIXnull) mice. C, Clot formation time from various mouse colonies. D, The incidence of samples with an amplitude that reached 2 mm but did not reach a firmness of 20 mm in platelet glycoprotein IIIa knockout (GPIIIanull), platelet glycoprotein Ibα knockout (GPIbαnull), FVIIInull, and FIXnull mice. E, Alpha angle (α-angle). F, Incidence of samples with no detectable α-angle in whole blood of FVIIInull and FIXnull mice within the test period of 1-h. *P < .05. **P < .01. ***P < .001. ****P < .0001

In platelet disease models, we compared GPIIIanull mice to GPIbαnull animals. The whole blood CT in the GPIbαnull group was significantly longer than in the GPIIIanull group (P < .01; Figure 3A). In hemophilia models, we compared FVIIInull mice to FIXnull mice. The whole blood CT from FVIIInull mice was significantly longer than that obtained from FIXnull mice (P < .01; Figure 3A). There were 11 out of 21 samples from FVIIInull mice in which the amplitude never reached 2 mm, meaning no clot formation during the 1-h test, and thereby whole blood CT from those animals was recorded as 3600 s. In contrast, there was only 1 of 10 FIXnull samples that did not clot within the 1-h test. The incidence of no-clot formation as determined by ROTEM in the FVIIInull group is significantly higher than in the FIXnull group (Figure 3B).

The CFT in WT-C57BL/6J mice was 300 ± 177 s, which was not statistically significantly different compared to those obtained from WT 129P3/J, WT-BALB/cJ, and VWFnull mice (165 ± 59 s, 152 ± 51 s, and 312 ± 238 s, respectively; Figure 3C). The CFT in the FV Leiden Q/Q group (115 ± 40 s) was significantly shorter than in the WT-C57BL/6J group. The CFTs in the GPIIIanull, GPIbαnull, FVIIInull, and FIXnull groups (2521 ± 1424 s, 804 ± 864 s, 2791 ± 1345 s, and 1698 ± 1355 s, respectively) were significantly longer than in the WT-C57BL/6J group. In the platelet disease models, there were 5 out of 10 samples in the GPIIIanull group with an amplitude that did not reach 20 mm during the 1-h test and thereby CFT from those animals was recorded as 3600 s. In contrast, only 1 of 17 in the GPIbαnull group had an amplitude that did not reach 20 mm (Figure 3D). The CFT in the GPIIIanull group was significantly longer than in the GPIbαnull group (Figure 3C). In hemophilia models, there were 15 out of 21 samples from the FVIIInull group with an amplitude that did not reach 20 mm, but only 3 of 10 in the FIXnull group did not reach the threshold of 20 mm (Figure 3D).

The α-angle in the WT-C57BL/6J group (47 ± 15.08 degrees) was significantly smaller than in the WT-129P3/J, WT-BALB/cJ, and FV Leiden Q/Q groups (60.14 ± 9.21, 62 ± 8.80, and 67.7 ± 7.42 degrees, respectively). The α-angle in the WT-C57BL/6J group was significantly higher than in the GPIIIanull, mGPIbαnull, FVIIInull, and FIXnull groups (32.5 ± 18.01, 30.65 ± 15.74, 6.86 ± 10.79, and 18.1 ± 18.81 degrees, respectively; Figure 3E). There was no statistically significant difference in the α-angle between the WT-C57BL/6J and VWFnull groups (Figure 3E). There were 14 of 21 samples from FVIIInull mice with no detectable α-angle formation during 1-h ROTEM analysis, which was significantly higher than the percentage of samples from FIXnull mice (Figure 3F).

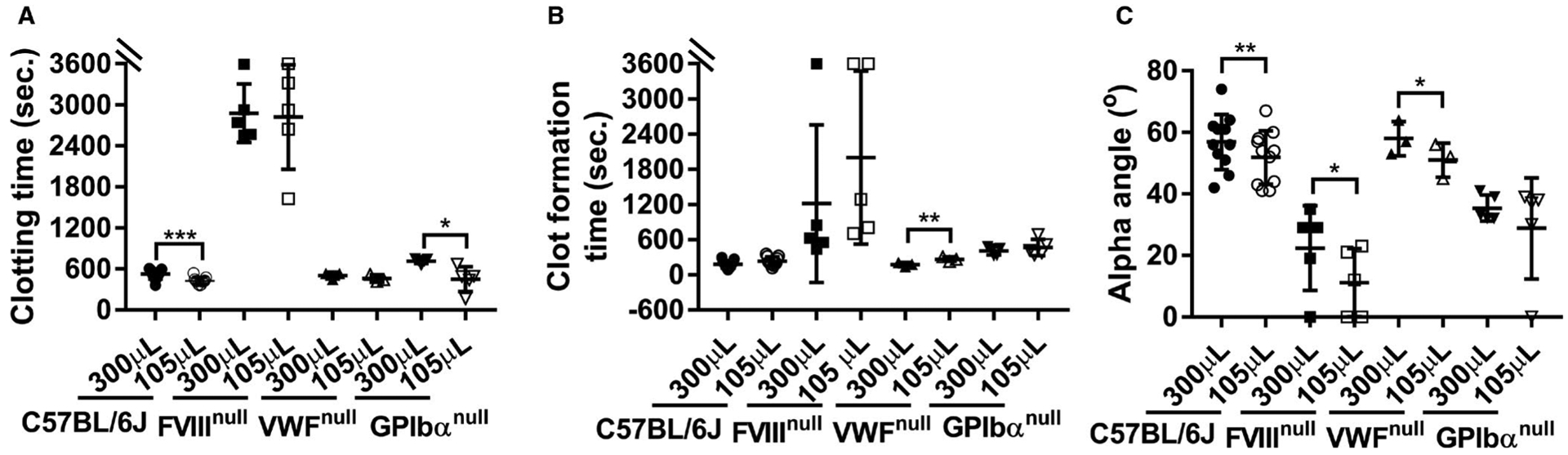

3.3 |. Other potential factors that may impact the parameters in ROTEM analysis

We then evaluated whether the type of cup used would impact the hemostatic parameters measured by ROTEM analysis of whole blood. As shown in Figure 4A, the CTs were statistically significantly shorter in both the WT-C57BL/6J and GPIbαnull groups, but not in the FVIIInull and VWFnull groups, using MiniCups with 105 μl of whole blood compared to the CTs from the tests using conventional ROTEM ProCup that requires 300 μl of whole blood. In terms of CFT, there was a difference between the tests using the MiniCup and the ProCup only in the VWFnull group, not in other colonies tested (Figure 4B). We found that α-angle in the C57BL/6J, FVIIInull, and VWFnull groups using the MiniCup was statistically significantly smaller than when using the ProCup. There was no significant difference in α-angle in the GPIbαnull group using the MiniCup versus the ProCup (Figure 4C). It appears that there is more variation in data generated from the MiniCup than from the ProCup in GPIbαnull mice in both CT (Figure 4A) and α-angle (Figure 4C).

FIGURE 4.

Comparing rotational thromboelastometry (ROTEM) analysis of whole blood in mice using the ProCup versus the MiniCup. Blood samples were collected from mice via inferior vena cava (IVC) blood draw using 3.8% sodium citrate as an anticoagulant (1:10 [vol/vol]). Whole blood from each mouse was run on the ROTEM ProCup/pin with 300 μl of blood plus 21 μl of 0.2 M CaCl2 and the MiniCup/pin with 105 μl of blood plus 7 μl of 0.2 M CaCl2 in parallel for 60 min and data were recorded. A, Clotting time. B, Clot formation time. C, Alpha angle. Statistical comparisons of two experimental groups were evaluated by paired Student’s t-test. *P < .05. **P < .01. ***P < .001

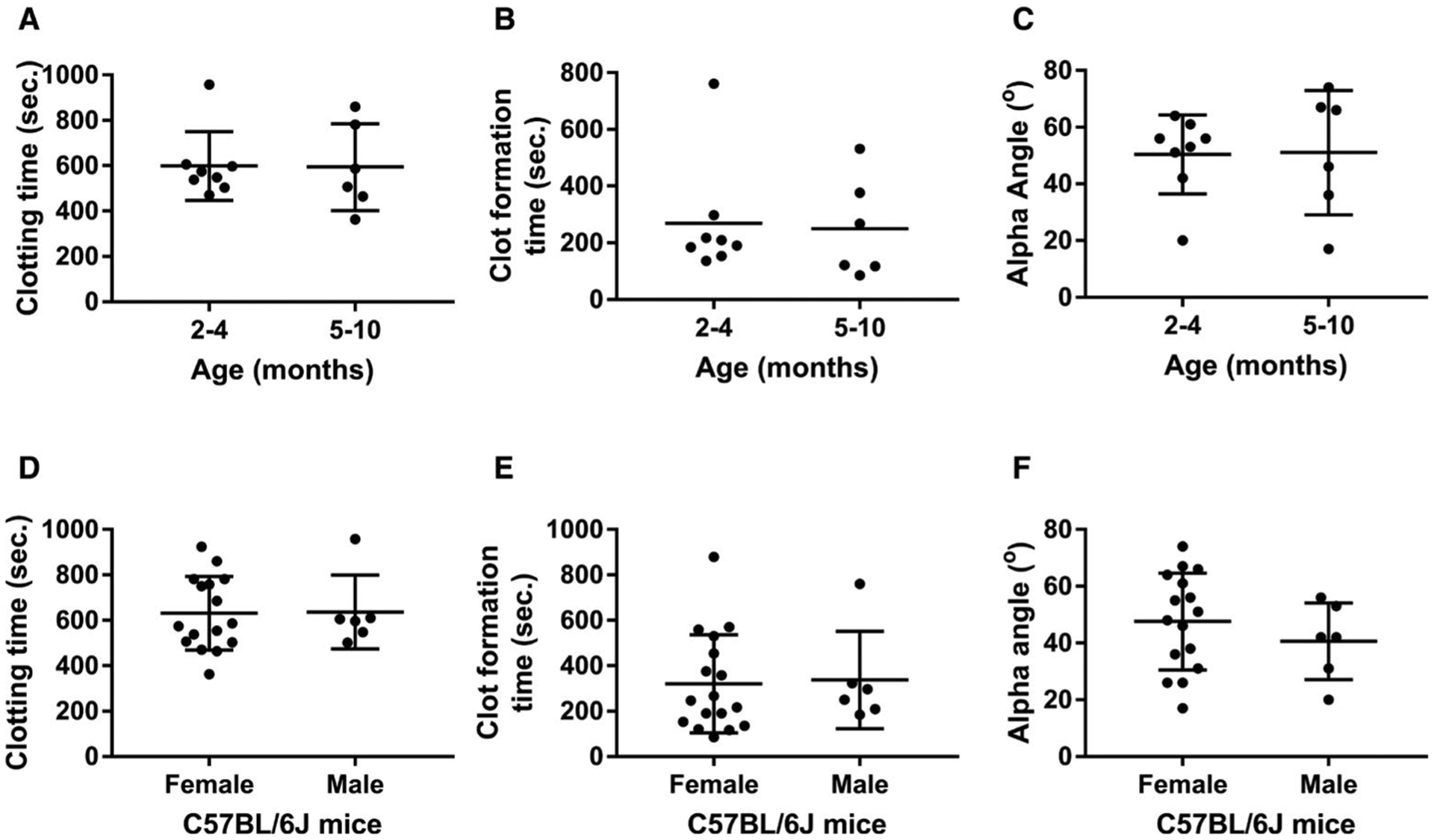

We then assessed whether age and/or sex impact hemostatic parameters in whole blood as determined by ROTEM analysis. We compared data from WT-C57BL/6J mice that were 2 to 4 versus 5 to 10 months old. There were no statistically significant differences between the two groups in any of the three parameters—CT, CFT, or α-angle (Figure 5A–C). When CT, CFT, and α-angle from females were compared to those from male WT-C57BL/6J animals, all three parameters were comparable between the two groups (Figure 5D–F). These data demonstrate that age and sex do not significantly affect the hemostatic parameters in whole blood as determined by ROTEM analysis in WT-C57BL/6J mice.

FIGURE 5.

Comparison of hemostatic properties determined by rotational thromboelastometry (ROTEM) analysis in wild-type C57BL/6J mice with different ages and sexes. Blood samples were collected from mice via inferior vena cava (IVC) blood draw using 3.8% sodium citrate as an anticoagulant (1:10 [vol/vol]). Samples from mice were run for 60 min using the ROTEM ProCup/pin loaded with 300 μl of blood plus 21 μl of 0.2 M CaCl2. Animals were assigned into two groups with the age difference between 2 to 4 months and 5 to 10 months or the sex difference between males and females. A, Clotting time in animals of different ages. B, Clot formation time in animals of different ages. C, Alpha angle in animals of different ages. D, Clotting time in animals of different sexes. E, Clot formation time in animals of different sexes. F, Alpha angle in animals of different sexes

3.4 |. Platelet-derived FVIII restores hemostatic properties in FVIIInull mice

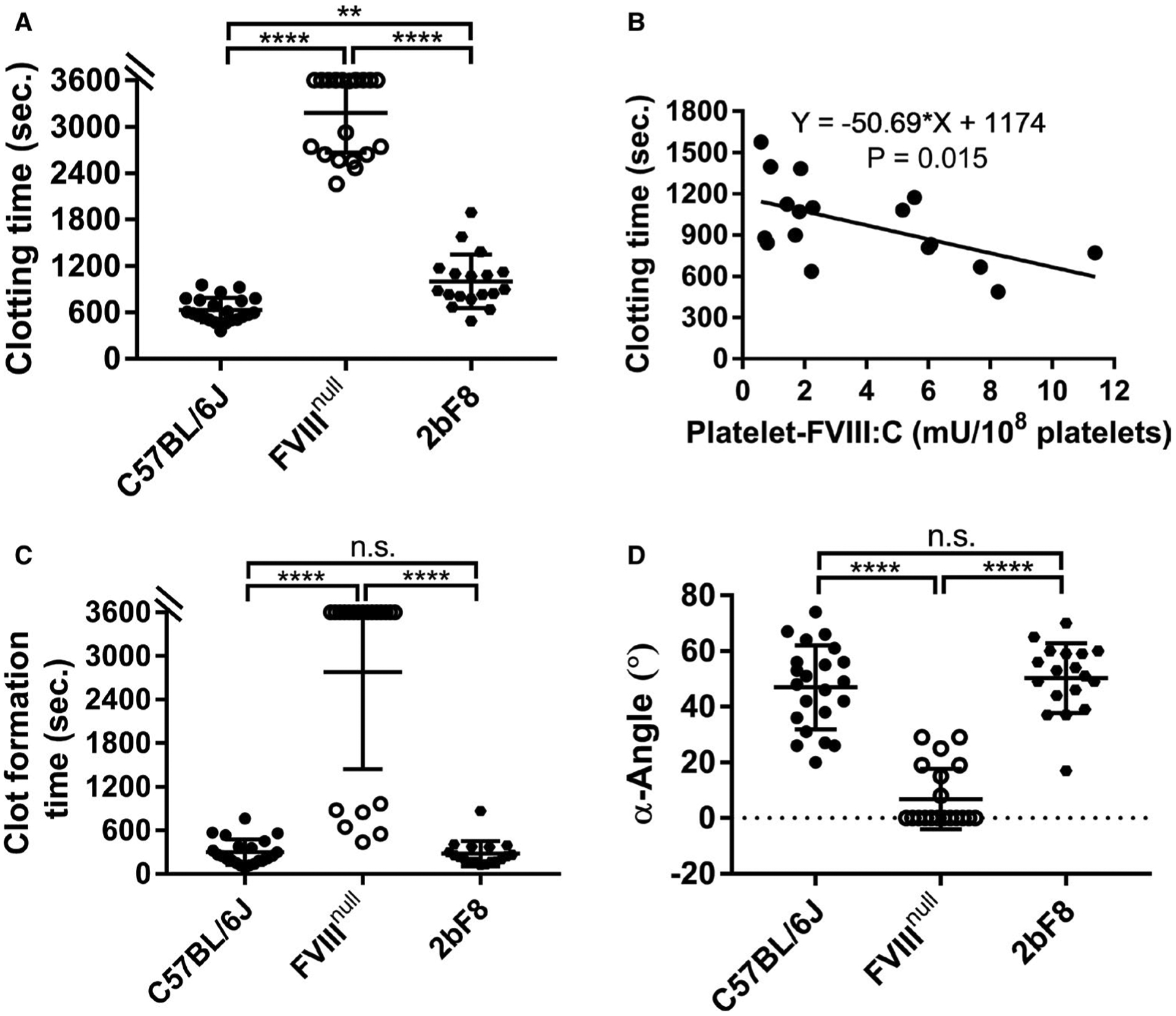

We evaluated the effectiveness of platelet-derived FVIII expression in restoring the hemostatic properties in hemophilia A mouse whole blood determined by ROTEM using the conventional ProCup. When FVIII was specifically expressed in FVIIInull mice with a level of 3.92 ± 3.18 mU per 108 platelets, ranging from 0.59 to 11.38 mU per 108 platelets, which corresponds to 1.2% to 22.7% of normal FVIII activity in whole blood in WT mice (assuming 1×109 platelets mL−1 in animals), hemostatic properties significantly improved compared to FVIIInull mice (Figure 6). Whole blood clotting time in the 2bF8 group (1003 ± 346 s, n = 18) was statistically significantly prolonged compared to the WT-C57BL/6J group (633 ± 158 s, n = 22; Figure 6A). There was a negative correlation between whole blood CT and the level of platelet-FVIII expression in 2bF8 mice (Figure 6B). Of note, there were no significant differences in terms of CFT and α-angle between the 2bF8 and WT groups (279 ± 172 s and 50.28 ± 12.48 degree vs. 299 ± 177 s and 47 ± 15.08 degrees, respectively; Figure 6C–D). These data demonstrate that expressing FVIII in platelets can restore hemostatic properties in hemophilia A mice as determined by ROTEM analysis.

FIGURE 6.

Rotational thromboelastometry (ROTEM) assessment of various levels of platelet-derived factor VIII (FVIII) in restoring hemostasis in FVIII knockout (FVIIInull) mice after platelet-specific FVIII (2bF8) expression. Blood samples were collected from mice via inferior vena cava (IVC) blood draw using 3.8% sodium citrate as an anticoagulant (1:10 [vol/vol]). Samples were run for 60 min using the ROTEM ProCup/pin loaded with 300 μl of blood plus 21 μl of 0.2 M CaCl2. Functional platelet-FVIII activity (platelet-FVIII:C) levels were determined by chromogenic assay. Wild-type C57BL/6J and FVIIInull mice served as controls. A, Clotting time. B, The correlation between clotting time and platelet-FVIII expression levels. C, Clot formation time. D, Alpha angle. **P < .01. ****P < .0001. “n.s.” indicates no statistically significant difference between the two groups

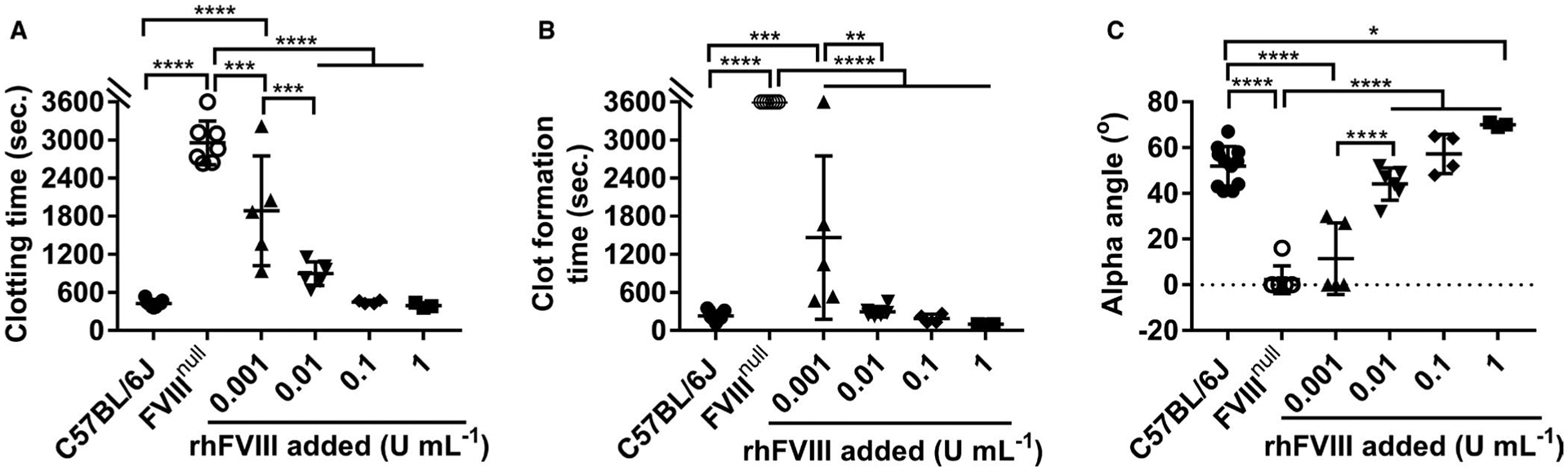

As a comparison, recombinant human B-domain deleted FVIII (rhFVIII, Xyntha [Pfizer]) was added to whole blood collected from FVIIInull mice to various levels (0.1% [0.001 U mL−1], 1% [0.01 U mL−1], 10% [0.1 U mL−1], and 100% [1 U mL−1]), and the hemostatic properties were assessed by ROTEM using MiniCups. Samples from FVIIInull mice with whole blood CTs that were greater than 2600 s and CFTs that did not reach the threshold of 20 mm were selected for the rhFVIII infusion study. We found that even 0.1% rhFVIII could significantly improve CT and CFT, but not α-angle, in FVIIInull whole blood. When 1% of rhFVIII was added to FVIIInull whole blood, all parameters were significantly improved to levels comparable to those in the WT control (Figure 7A–C). All parameters were significantly improved in the 1% rhFVIII group compared to the 0.1% group. Increasing the rhFVIII level from 1% to 10% appeared to further improve the hemostatic parameters, but there were no statistically significant differences between the two groups (Figure 7A–C). There were no statistically significant differences between the WT control group and the FVIIInull group with 1% or 10% rhFVIII in whole blood CT, CFT, or α-angle. These data suggest that ROTEM analysis is very sensitive to low levels of plasma FVIII.

FIGURE 7.

Rotational thromboelastometry (ROTEM) assessment of various levels of plasma-factor VIII (FVIII) in restoring hemostasis in FVIII knockout (FVIIInull) mice. Recombinant human B-domain deleted FVIII (rhFVIII) was added to whole blood collected from FVIIInull mice to various levels (0 U/ml, 0.001 U/ml [0.1%], 0.01 U/ml [1%], 0.1 U/ml [10%], and 1 U/ml [100%]). Samples were run for 60 min using the ROTEM MiniCup loaded with 105 μl of whole blood plus 7 μl of 2 M CaCl2. Wild-type C57BL/6J served as a control. A, Clotting time. B, Clot formation time. C, Alpha angle. *P < .05. **P < .01. ***P < .001. ****P < .0001

4 |. DISCUSSION

While ROTEM analysis has been commonly used in the clinic to measure the clot elasticity of whole blood coagulopathies, it could be more challenging to apply the assay in mouse model studies due to the natural limitations of the small animal model. In this study, we used ROTEM analysis to assess hemostatic properties in mouse models with various coagulopathies. We found that the quality of the blood samples is critical for generating reliable results in the ROTEM assay. With qualified blood samples, ROTEM enables quantitative and qualitative assessment of the hemostatic properties in mouse models with coagulopathies, including bleeding and abnormal clotting disorders.

Compared to TEG, which requires 360 μl of blood for the assay, ROTEM analysis offers the possibility of using a smaller volume (105 μl or 300 μl) of the sample, which could be beneficial for working on small animal models. While ROTEM MiniCup analysis offers the potential feasibility of survivable blood collection, which would allow animals to be saved for the time course study, the quality of blood specimens from survivable blood collection is a challenging issue that can cause variation and inconsistency for the ROTEM assay. We validated ROTEM analysis of whole blood samples collected from FVIIInull and WT mice via the tail vein, submandibular vein, and retro-orbital venous plexus, from which a sufficient blood volume could be collected for ROTEM MiniCup analysis. Our results demonstrate that all parameters determined by ROTEM analysis were affected when blood samples were collected via tail, submandibular, or eye bleed, resulting in no differences between the FVIIInull and WT groups. These data suggest that blood samples collected from either tail bleeds, submandibular bleeds, or eye bleeds are not suitable for ROTEM analysis. We reason that this might be due to tissue factor contamination, which may accelerate the activation of blood coagulation after recalcification. In addition, during our preliminary studies (data not shown), we noticed that air bubbles generated during the blood draw could also impact the ROTEM results. We conclude that, for ROTEM analysis, only qualified blood samples from smooth blood draws with an appropriate anticoagulant (e.g., 1:10 [vol:vol] of 3.8% sodium citrate) can generate reliable results. While both the ProCup and MiniCup can generate useful information, using the MiniCup is likely to result in higher variability compared to using the ProCup, which has also been reported in human studies.28 However, using the MiniCup allows for saving blood for other ROTEM tests if needed or for other assays. Thus, one must be aware of the potential differences in data generated using the ProCup versus the MiniCup, and one must use a consistent method throughout any given experiment.

For hemophilia-model mice, the defect in blood coagulation can be reflected in significantly prolonged whole blood CT and CFT as determined by ROTEM analysis. Viscoelastic properties of blood clots in hemophilia A mice were poorer than in hemophilia B mice. The whole blood CT is a sensitive parameter from ROTEM analysis that can be used to gauge low levels of plasma FVIII, but the difference becomes subtle when plasma FVIII levels are greater than 10%. While the chromogenic-based assay is a sensitive assay that is commonly used to quantify functional FVIII activity levels in both human and animal model studies, the sensitivity of the assay is 1%. Of note, the CT and CFT determined by ROTEM analysis in whole blood from FVIIInull with 0.1% rhFVIII were statistically significantly shortened compared to those without rhFVIII. When 0.1% rhFVIII was added to FVIIInull whole blood, CT and CFT measured by ROTEM dramatically improved by 36% and 59%, but not α-angle. However, when FVIII was expressed and stored in platelets in FVIIInull mice (with levels corresponding to 1.2–22.7%), CFT and α-angle were completely normalized in whole blood, although CT was not fully restored compared to WT mice. These results are consistent with our previous platelet-specific gene therapy reports in hemophilia A rats with platelet-FVIII expression.29 Our results indicate that once platelets are activated, the clot development could be normalized and with corrected viscoelastic properties of the blood clot if FVIII is stored in platelets.

Interestingly, all parameters in the VWFnull group by ROTEM analysis were comparable to those in the WT-C57BL/6J group. This could be because VWFnull mice still have approximately 10% of normal FVIII remaining in plasma.30,31 In addition, there is a possibility that the lack of a difference between the WT and the VWFnull groups is due to the absence of endothelium or the lack of shear stress in the ROTEM assay. In ROTEM analysis, no activated surface is present. Therefore, the role of VWF in mediating adhesion between activated platelets and the endothelium is lacking. Indeed, using a tail bleeding time assay, the bleeding time in VWFnull mice was significantly longer than in WT mice.30,32 Furthermore, our previous study showed that endothelial cell-derived VWF alone is sufficient to support hemostasis, but platelet-derived VWF is less effective as demonstrated by the tail bleeding time assay,32 confirming the important biological function of the interactions among VWF, endothelial cells, and platelets in clot formation in vivo. Thus, it is important to know that the ROTEM assay has its limitations in sensitivity and specificity in assessing the hemostatic properties of certain coagulation factor(s) in certain disease model(s) if the hemostatic function of that factor involves other element(s) beyond the components of blood, for example, VWF in the von Willebrand disease model.

For platelet disorder model mice, CFT and α-angle are the key parameters affected. Whole blood from GPIIIanull mice had a distinct ROTEM profile with normal CT, but an extreme prolongation of CFT and a small α-angle compared to those from WT mice. The amplitude in all GPIIIanull samples reached 2 mm within a range similar to WT samples, but 50% of the samples never reached 20 mm during our observation period (1 h). These results indicate that hemostasis can be initiated, but clot development is blocked due to the dysfunction of platelet αIIbβ3 in platelets leading to reduced platelet aggregation and clot retraction in the GPIIIanull group. This is in agreement with the results obtained from a clinical study using TEG or ROTEM to analyze the hemostatic profile in whole blood from patients with Glanzmann’s thrombasthenia.33–35 In contrast, in the GPIbαnull group, all parameters, including CT, CFT, and α-angle determined by ROTEM, were impaired compared to the WT group, but the changes were subtle and the amplitude of all samples but one reached the defined CFT threshold of 20 mm. Thus, CFT and α-angle from native ROTEM analysis could be reliable parameters used to determine the hemostatic properties in mouse models with platelet deficiency.

For thrombophilia FV Leiden mouse model mice, all parameters determined by ROTEM were significantly affected with shorter CT and CFT and larger α-angle compared to those from WT-C57BL/6J control animals. FV Leiden Q/Q mice have prothrombotic conditions with enhanced D-dimer and TAT (thrombin anti-thrombin complexes).24,36,37 Our studies confirm that ROTEM analysis can reflect a hypercoagulation condition in FV Leiden Q/Q mice. It has been shown that genetic background could impact the bleeding phenotype in mice determined by tail bleeding tests. For example, WT-C57BL/6J mice have increased blood loss compared to those in 129S or BALB/cJ backgrounds.38–40 When we compared hemostatic properties in WT mice in C57BL/6J, 129P3/J, and BALB/cJ backgrounds, we found that the only difference was that α-angles in the 129P3/J and BALB/cJ groups were significantly larger than in the C57BL/6J group. Although it has been reported that sex can impact the maximum amplitude determined by TEG and activated partial thromboplastin time, there were no significant differences between male and female mice in terms of CT, CFT, and α-angle determined by native ROTEM in our studies in C57BL/6J mice. It is unknown whether other strains might have sex differences, though there is no mechanistic reason to expect any gender difference in different strains.

In summary, our studies demonstrate that ROTEM analysis of whole blood is a sensitive assay that can be used to assess coagulation functions in mouse models with bleeding or clotting disorders. The whole blood clotting time generated by ROTEM analysis is a sensitive parameter that could be used to evaluate the hemostatic effectiveness of new therapeutic proteins in hemophilia mice. The quality of blood sample collection is critical for the ROTEM assay to achieve reliable results.

Essentials.

The route of blood collection can cause variabilities in the rotational thromboelastometry (ROTEM) test.

ROTEM is sensitive to low levels of plasma- or platelet-factor VIII in blood.

ROTEM is capable of detecting a deficiency in platelet glycoprotein (GP)Ibα or GPIIIa.

ROTEM is able to detect the thrombotic condition in factor V Leiden model.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank H. Kazazian at the University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine (Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, USA) for the FVIII knockout mice. We thank J. Ware at the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences (Little Rock, Arkansas, USA) for GPIbα knockout mice. We thank R. O. Hynes at the Howard Hughes Medical Institute (Cambridge, Massachusetts, USA) for β3−/− mice. This work was supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, National Institutes of Health grants HL-102035 (QS), HL-139847 (RRM), and HL-081588 (RRM), and generous gifts from the Children’s Wisconsin Foundation (QS), Midwest Athletes Against Childhood Cancer and Bleeding Disorder (MACC) Fund (QS), Versiti Blood Research Foundation (RRM), and John & Judith Gardetto and the Glanzmann Research Foundation (DAW).

Funding information

the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, National Institutes of Health grants, Grant/Award Number: HL-102035 (QS), HL-139847 (RRM) and HL-081588 (RRM)

Footnotes

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

REFERENCES

- 1.Theusinger OM, Nürnberg J, Asmis LM, Seifert B, Spahn DR. Rotation thromboelastometry (ROTEM) stability and reproducibility over time. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2010;37:677–683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Akay OM. The double hazard of bleeding and thrombosis in hemostasis from a clinical point of view: a global assessment by rotational thromboelastometry (ROTEM). Clin Appl Thromb Hemost. 2018;24:850–858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wikkelsø A, Wetterslev J, Møller AM, Afshari A. Thromboelastography (TEG) or rotational thromboelastometry (ROTEM) to monitor haemostatic treatment in bleeding patients: a systematic review with meta-analysis and trial sequential analysis. Anaesthesia. 2017;72:519–531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hartert H. Blood clotting studies with thrombus stressography; a new Investigation procedure. Klin Wochenschr. 1948;26:577–583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mallett SV, Cox DJ. Thrombelastography. Br J Anaesth. 1992;69:307–313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vig S, Chitolie A, Bevan DH, Halliday A, Dormandy J. Thromboelastography: a reliable test? Blood Coagul Fibrinolysis. 2001;12:555–561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Di BP, Baciarello M, Cabetti L, Martucci M, Chiaschi A, Thrombelastography BL. Present and future perspectives in clinical practice. Minerva Anestesiol. 2003;69:501–515. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Da Luz LT, Nascimento B, Shankarakutty AK, Rizoli S, Adhikari NK. Effect of thromboelastography (TEG(R)) and rotational thromboelastometry (ROTEM(R)) on diagnosis of coagulopathy, transfusion guidance and mortality in trauma: descriptive systematic review. Crit Care. 2014;18:518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Othman M, Kaur H. Thromboelastography (TEG). Methods Mol Biol. 2017;1646:533–543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sakai T. Comparison between thromboelastography and thromboelastometry. Minerva Anestesiol. 2019;85:1346–1356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Durila M. Nonactivated thromboelastometry able to detect fibrinolysis in contrast to activated methods (EXTEM, INTEM) in a bleeding patient. Blood Coagul Fibrinolysis. 2016;27:828–830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Crochemore T, Piza FMdT, Rodrigues RdR, Guerra JCdC, Ferraz LJR, Corrêa TD. A new era of thromboelastometry. Einstein. 2017;15:380–385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sørensen B, Johansen P, Christiansen K, Woelke M, Ingerslev J. Whole blood coagulation thrombelastographic profiles employing minimal tissue factor activation. J Thromb Haemost. 2003;1:551–558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hacein-Bey-Abina S, Le Deist F, Carlier F, et al. Sustained correction of X-linked severe combined immunodeficiency by ex vivo gene therapy. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:1185–1193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sørensen B, Ingerslev J. Thromboelastography and recombinant factor VIIa-hemophilia and beyond. Semin Hematol. 2004;41:140–144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sorensen B, Ingerslev J. Whole blood clot formation phenotypes in hemophilia A and rare coagulation disorders. Patterns of response to recombinant factor VIIa. J Thromb Haemost. 2004;2:102–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tanaka KA, Bolliger D, Vadlamudi R, Nimmo A. Rotational thromboelastometry (ROTEM)-based coagulation management in cardiac surgery and major trauma. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2012;26:1083–1093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brake MA, Ivanciu L, Maroney SA, Martinez ND, Mast AE, Westrick RJ. Assessing blood clotting and coagulation factors in mice. Curr Protoc Mouse Biol. 2019;9:e61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bi L, Lawler AM, Antonarakis SE, High KA, Gearhart JD, Kazazian HH Jr. Targeted disruption of the mouse factor VIII gene produces a model of haemophilia A. Nat Genet. 1995;10:119–121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lin HF, Maeda N, Smithies O, Straight DL, Stafford DW. A coagulation factor IX-deficient mouse model for human hemophilia B. Blood. 1997;90:3962–3966. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ware J, Russell SR, Marchese P, Ruggeri ZM. Expression of human platelet glycoprotein Ib alpha in transgenic mice. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:8376–8382. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hodivala-Dilke KM, McHugh KP, Tsakiris DA, et al. Beta3-integrin-deficient mice are a model for Glanzmann thrombasthenia showing placental defects and reduced survival. J Clin Invest. 1999;103:229–238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fang J, Hodivala-Dilke K, Johnson BD, et al. Therapeutic expression of the platelet-specific integrin, alphaIIbbeta3, in a murine model for Glanzmann thrombasthenia. Blood. 2005;106:2671–2679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cui J, Eitzman DT, Westrick RJ, et al. Spontaneous thrombosis in mice carrying the factor V Leiden mutation. Blood. 2000;96:4222–4226. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chen Y, Schroeder JA, Chen J, et al. The immunogenicity of platelet-derived FVIII in hemophilia A mice with or without preexisting anti-FVIII immunity. Blood. 2016;127:1346–1354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schroeder JA, Chen Y, Fang J, Wilcox DA, Shi Q. In vivo enrichment of genetically manipulated platelets corrects the murine hemophilic phenotype and induces immune tolerance even using a low multi-plicity of infection. J Thromb Haemost. 2014;12:1283–1293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang IJ, Park SW, Bae BK, et al. FIBTEM improves the sensitivity of hyperfibrinolysis detection in severe trauma patients: a retrospective study using thromboelastometry. Sci Rep. 2020;10:6980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Haas T, Spielmann N, Dillier C, Cushing M, Siegmund S, Kruger B. Comparison of conventional ROTEM(R) cups and pins to the ROTEM(R) cup and pin mini measuring cells (MiniCup). Scand J Clin Lab Invest. 2015;75:470–475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shi Q, Mattson JG, Fahs SA, Geurts AM, Weiler H, Montgomery RR. The severe spontaneous bleeding phenotype in a novel hemophilia A rat model is rescued by platelet FVIII expression. Blood Adv. 2020;4:55–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Denis C, Methia N, Frenette PS, et al. A mouse model of severe von Willebrand disease: defects in hemostasis and thrombosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:9524–9529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shi Q, Kuether EL, Schroeder JA, Fahs SA, Montgomery RR. Intravascular recovery of VWF and FVIII following intraperitoneal injection and differences from intravenous and subcutaneous injection in mice. Haemophilia. 2012;18:639–646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kanaji S, Fahs SA, Shi Q, Haberichter SL, Montgomery RR. Contribution of platelet vs. endothelial VWF to platelet adhesion and hemostasis. J Thromb Haemost. 2012;10:1646–1652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ahammad J, Kamath A, Shastry S, Chitlur M, Kurien A. Clinico-hematological and thromboelastographic profiles in glanzmann’s thrombasthenia. Blood Coagul Fibrinolysis. 2020;31:29–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shenkman B, Livnat T, Misgav M, Budnik I, Einav Y, Martinowitz U. The in vivo effect of fibrinogen and factor XIII on clot formation and fibrinolysis in Glanzmann’s thrombasthenia. Platelets. 2012;23:604–610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Grassetto A, Fullin G, Lazzari F, et al. Perioperative ROTEM and ROTEMplatelet monitoring in a case of Glanzmann’s thrombasthenia. Blood Coagul Fibrinolysis. 2017;28:96–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Eitzman DT, Westrick RJ, Shen Y, et al. Homozygosity for factor V Leiden leads to enhanced thrombosis and atherosclerosis in mice. Circulation. 2005;111:1822–1825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Baumgartner CK, Mattson JG, Weiler H, Shi Q, Montgomery RR. Targeting factor VIII expression to platelets for hemophilia A gene therapy does not induce an apparent thrombotic risk in mice. J Thromb Haemost. 2017;15:98–109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Broze GJ Jr, Yin ZF, Lasky N. A tail vein bleeding time model and delayed bleeding in hemophiliac mice. Thromb Haemost. 2001;85:747–748. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schiviz A, Magirr D, Leidenmühler P, Schuster M, Muchitsch E-m, Höllriegl W. Influence of genetic background on bleeding phenotype in the tail-tip bleeding model and recommendations for standardization: communication from the SSC of the ISTH. J Thromb Haemost. 2014;12:1940–1942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kopić A, Benamara K, Schuster M, et al. Coagulation phenotype of wild-type mice on different genetic backgrounds. Lab Anim. 2019;53:43–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]