From the Authors:

We thank Dr. Kasugai and colleagues for their insightful comment following our comparative cohort study (1), which raises, in particular, the question of the futility, and even the potential harmfulness, of empirical antibiotics for suspected early bacterial coinfection among critically ill patients with coronavirus disease (COVID-19). We take this opportunity to further discuss some additional data regarding the impact of “appropriate” early antibiotic therapy on the outcome of patients with COVID-19 requiring mechanical ventilation.

Antibiotic prescribing in patients with COVID-19 is substantial. Data from first waves worldwide show a rate of antibiotic use of 75%, with antibiotics mainly being started on admission, use being significantly higher in ICU settings (up to 85%), and an increasing proportion of use being shown in mechanically ventilated patients (2). Although a trend toward reduced antibiotic use is noted as the pandemic progresses, this rate is far higher than the reported prevalence, below 10%, of early bacterial coinfection among hospitalized patients, even in the ICU (1, 2). However, we agree with Dr. Kasugai and colleagues on the hypothesis of a future shift in the prevalence, etiology, and severity of early bacterial coinfection in patients with COVID-19 owing to the generalized use of antiinflammatory therapies and the evolution of patients’ underlying conditions, selecting those with a poor immune response to the vaccine.

Initial antibiotic therapy to treat suspected early bacterial coinfection can be retrospectively considered as “inappropriate” when 1) no antibiotic matched the in vitro susceptibility of the identified bacteria (3), and 2) no subsequent bacterial documentation occurred, leading to the conclusion of a possibly unnecessary initial antibiotic therapy. This last situation, the most frequent in daily practice, greatly depends on the effective microbiological diagnosis of coinfection. Bacterial identification may underestimate the true coinfection status owing to a lack of a quality microbiological specimen or antibiotics at the time of sampling.

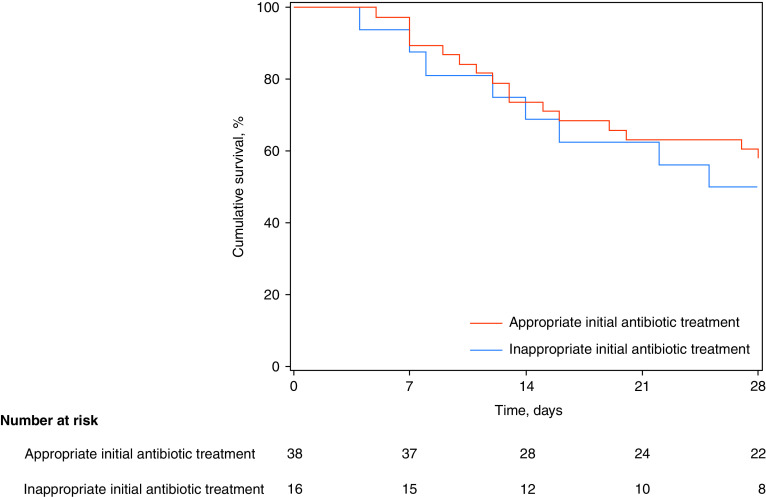

Ultimately, Dr. Kasugai and colleagues address two distinct research questions. First, is appropriate early antibiotic treatment among coinfected patients with COVID-19 ineffective and, therefore, futile? As reported, only 70% of coinfected patients with COVID-19 received appropriate antibiotics. Surprisingly, although early bacterial identification was associated with an increased risk for 28-day mortality in patients with COVID-19, we did not observe an association between appropriate antibiotics and survival (28-day mortality: 42% [16/38] and 50% [8/16] in the case of appropriate and inappropriate initial antibiotic treatment, respectively; Figure 1), as one could expect (3). Interestingly, appropriate antibiotic use did not result in better survival in coinfected critically ill patients with influenza despite coinfection being an independent risk factor of death in this population (4). Second, is unnecessary initial antibiotic therapy among patients with no proven early bacterial coinfection harmful? Reducing antibiotic exposure is the cornerstone of the fight against antimicrobial resistance and nosocomial infections in the ICU (5). However, again, no association was found between antibiotics started or continued in the first 24 hours of ICU admission and mortality among patients without documented early bacterial coinfection (28-day mortality: 31% [17/54] and 27% [121/450] in the absence and presence of initial antibiotic treatment, respectively; Figure 2). However, our study was clearly underpowered to detect an effect of early antibiotics on outcome, as the number of coinfected patients with COVID-19, as well as the number of noncoinfected patients without any antibiotic upon ICU admission, was limited.

Figure 1.

Kaplan-Meier 28-day survival curves for patients with coronavirus disease (COVID-19) with early bacterial identification, according to appropriateness of initial antibiotic treatment.

Figure 2.

Kaplan-Meier 28-day survival for patients with coronavirus disease (COVID-19) without early bacterial identification, according to the presence or not of initial antibiotic treatment (within the first 24 h of ICU admission).

Critically ill patients with COVID-19 under mechanical ventilation may not all benefit from systematic early empirical antibiotics. Indication for antimicrobial treatment should be individualized at ICU admission after microbiological sampling, including respiratory secretions, before any antibiotic administration if possible. Toward better antimicrobial stewardship, a reasonable strategy could be to wait for the microbiological findings before prescribing antibiotics in patients with less severe disease and to initiate antibiotics with quick discontinuation based on microbiological results in patients with more severe disease, such as those with severe acute respiratory distress syndrome or septic shock.

Footnotes

Originally Published in Press as DOI: 10.1164/rccm.202108-1846LE on September 21, 2021

Author disclosures are available with the text of this letter at www.atsjournals.org.

References

- 1. Rouzé A, Martin-Loeches I, Povoa P, Metzelard M, Du Cheyron D, Lambiotte F, et al. coVAPid study group. Early bacterial identification among intubated patients with COVID-19 or influenza pneumonia: a European multicenter comparative cohort study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med . 2021;204:546–556. doi: 10.1164/rccm.202101-0030OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Langford BJ, So M, Raybardhan S, Leung V, Soucy JR, Westwood D, et al. Antibiotic prescribing in patients with COVID-19: rapid review and meta-analysis. Clin Microbiol Infect . 2021;27:520–531. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2020.12.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Kollef MH, Sherman G, Ward S, Fraser VJ. Inadequate antimicrobial treatment of infections: a risk factor for hospital mortality among critically ill patients. Chest . 1999;115:462–474. doi: 10.1378/chest.115.2.462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Martin-Loeches I, J Schultz M, Vincent JL, Alvarez-Lerma F, Bos LD, Solé-Violán J, et al. Increased incidence of co-infection in critically ill patients with influenza. Intensive Care Med . 2017;43:48–58. doi: 10.1007/s00134-016-4578-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Rouzé A, Martin-Loeches I, Povoa P, Makris D, Artigas A, Bouchereau M, et al. coVAPid study Group. Relationship between SARS-CoV-2 infection and the incidence of ventilator-associated lower respiratory tract infections: a European multicenter cohort study. Intensive Care Med . 2021;47:188–198. doi: 10.1007/s00134-020-06323-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]