The American Diabetes Association’s (ADA’s) Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes (the Standards) is updated and published annually in a supplement to the January issue of Diabetes Care. The Standards are developed by the ADA’s multidisciplinary Professional Practice Committee, which comprises expert diabetes health care professionals. The Standards include the most current evidence-based recommendations for diagnosing and treating adults and children with all forms of diabetes. ADA’s grading system uses A, B, C, or E to show the evidence level that supports each recommendation.

A—Clear evidence from well-conducted, generalizable randomized controlled trials that are adequately powered

B—Supportive evidence from well-conducted cohort studies

C—Supportive evidence from poorly controlled or uncontrolled studies

E—Expert consensus or clinical experience

This is an abridged version of the current Standards of Care containing the evidence-based recommendations most pertinent to primary care. The recommendations, tables, and figures included here retain the same numbering used in the complete Standards. All of the recommendations included here are substantively the same as in the complete Standards. The abridged version does not include references. The complete 2022 Standards of Care, including all supporting references, is available at professional.diabetes.org/standards.

1. Improving Care and Promoting Health in Populations

Diabetes and Population Health

Patient-centered care is defined as care that considers individual patient comorbidities and prognoses; is respectful of and responsive to patient preferences, needs, and values; and ensures that patient values guide all clinical decisions. Further, social determinants of health (SDOH)—often out of direct control of the individual and potentially representing lifelong risk—contribute to medical and psychosocial outcomes and must be addressed to improve all health outcomes.

Recommendations

1.1 Ensure treatment decisions are timely, rely on evidence-based guidelines, include social community support, and are made collaboratively with patients based on individual preferences, prognoses, and comorbidities, and informed financial considerations. B

1.2 Align approaches to diabetes management with the Chronic Care Model. This model emphasizes person-centered team care, integrated long-term treatment approaches to diabetes and comorbidities, and ongoing collaborative communication and goal setting between all team members. A

1.3 Care systems should facilitate team-based care, including those knowledgeable and experienced in diabetes management as part of the team and utilization of patient registries, decision support tools, and community involvement to meet patient needs. B

Strategies for System-Level Improvement

Care Teams

Collaborative, multidisciplinary teams are best suited to provide care for people with chronic conditions such as diabetes and to facilitate patients’ self-management with emphasis on avoiding therapeutic inertia to achieve the recommended metabolic targets.

Telemedicine

Telemedicine may increase access to care for people with diabetes. Increasingly, evidence suggests that various telemedicine modalities may be effective at reducing A1C in people with type 2 diabetes compared with or in addition to usual care. Interactive strategies that facilitate communication between providers and patients appear more effective.

Behaviors and Well-Being

Successful diabetes care requires a systematic approach to supporting patients’ behavior-change efforts, including high-quality diabetes self-management education and support (DSMES).

Tailoring Treatment for Social Context

Recommendations

1.5 Assess food insecurity, housing insecurity/homelessness, financial barriers, and social capital/social community support to inform treatment decisions, with referral to appropriate local community resources. A

1.6 Provide patients with self-management support from lay health coaches, navigators, or community health workers when available. A

Health inequities related to diabetes and its complications are well documented and have been associated with greater risk for diabetes, higher population prevalence, and poorer diabetes outcomes. SDOH are defined as the economic, environmental, political, and social conditions in which people live and are responsible for a major part of health inequality worldwide. In addition, cost-related medication nonadherence continues to contribute to health disparities.

2. Classification and Diagnosis of Diabetes

Classification

Diabetes can be classified into the following general categories:

Type 1 diabetes (due to autoimmune β-cell destruction, usually leading to absolute insulin deficiency including latent autoimmune diabetes of adulthood)

Type 2 diabetes (due to a progressive loss of β-cell insulin secretion frequently on the background of insulin resistance)

Specific types of diabetes due to other causes, e.g., monogenic diabetes syndromes (such as neonatal diabetes and maturity-onset diabetes of the young), diseases of the exocrine pancreas (such as cystic fibrosis and pancreatitis), and drug- or chemical-induced diabetes (such as with glucocorticoid use, in the treatment of HIV/AIDS, or after organ transplantation)

Gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM; diabetes diagnosed in the second or third trimester of pregnancy that was not clearly overt diabetes prior to gestation)

It is important for providers to realize that classification of diabetes type is not always straightforward at presentation, and misdiagnosis may occur. Children with type 1 diabetes typically present with polyuria/polydipsia, and approximately half present with diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA). Adults with type 1 diabetes may not present with classic symptoms and may have a temporary remission from the need for insulin. The diagnosis may become more obvious over time and should be reevaluated if there is concern.

Screening and Diagnostic Tests for Prediabetes and Type 2 Diabetes

The diagnostic criteria for diabetes and prediabetes are shown in Table 2.2/2.5. Screening criteria for adults and children are listed in Table 2.3 and Table 2.4, respectively. Screening for prediabetes and type 2 diabetes risk through an informal assessment of risk factors or with an assessment tool, such as the ADA’s risk test (diabetes.org/socrisktest) is recommended.

TABLE 2.2/2.5.

Criteria for the Screening and Diagnosis of Prediabetes and Diabetes

| Prediabetes | Diabetes | |

|---|---|---|

| A1C | 5.7–6.4% (39–47 mmol/mol)* | ≥6.5% (48 mmol/mol)† |

| Fasting plasma glucose | 100–125 mg/dL (5.6–6.9 mmol/L)* | ≥126 mg/dL (7.0 mmol/L)† |

| 2-hour plasma glucose during 75-g OGTT | 140–199 mg/dL (7.8–11.0 mmol/L)* | ≥200 mg/dL (11.1 mmol/L)† |

| Random plasma glucose | — | ≥200 mg/dL (11.1 mmol/L)‡ |

Adapted from Tables 2.2 and 2.5 in the complete 2022 Standards of Care.

For all three tests, risk is continuous, extending below the lower limit of the range and becoming disproportionately greater at the higher end of the range.

In the absence of unequivocal hyperglycemia, diagnosis requires two abnormal test results from the same sample or in two separate samples

Only diagnostic in a patient with classic symptoms of hyperglycemia or hyperglycemic crisis.

TABLE 2.3.

Criteria for Screening for Diabetes or Prediabetes in Asymptomatic Adults

| 1. Testing should be considered in adults with overweight or obesity (BMI ≥25 kg/m2 or ≥23 kg/m2 in Asian Americans) who have one or more of the following risk factors: • First-degree relative with diabetes • High-risk race/ethnicity (e.g., African American, Latino, Native American, Asian American, Pacific Islander) • History of CVD • Hypertension (≥140/90 mmHg or on therapy for hypertension) • HDL cholesterol level <35 mg/dL (0.90 mmol/L) and/or a triglyceride level >250 mg/dL (2.82 mmol/L) • Women with polycystic ovary syndrome • Physical inactivity • Other clinical conditions associated with insulin resistance (e.g., severe obesity, acanthosis nigricans) |

| 2. Patients with prediabetes (A1C ≥5.7% [39 mmol/mol], impaired glucose tolerance, or impaired fasting glucose]) should be tested yearly. |

| 3. Women who were diagnosed with GDM should have lifelong testing at least every 3 years. |

| 4. For all other patients, testing should begin at age 35 years. |

| 5. If results are normal, testing should be repeated at a minimum of 3-year intervals, with consideration of more frequent testing depending on initial results and risk status. |

| 6. People with HIV |

TABLE 2.4.

Risk-Based Screening for Type 2 Diabetes or Prediabetes in Asymptomatic Children and Adolescents in a Clinical Setting

| Screening should be considered in youth* who have overweight (≥85th percentile) or obesity (≥95th percentile) A and who have one or more additional risk factors based on the strength of their association with diabetes: • Maternal history of diabetes or GDM during the child’s gestation A • Family history of type 2 diabetes in first- or second-degree relative A • Race/ethnicity (Native American, African American, Latino, Asian American, Pacific Islander) A • Signs of insulin resistance or conditions associated with insulin resistance (acanthosis nigricans, hypertension, dyslipidemia, polycystic ovary syndrome, or small-for-gestational-age birth weight) B |

After the onset of puberty or after 10 years of age, whichever occurs earlier. If tests are normal, repeat testing at a minimum of 3-year intervals, or more frequently if BMI is increasing or risk factor profile deteriorating, is recommended. Reports of type 2 diabetes before age 10 years exist, and this can be considered with numerous risk factors.

Marked discrepancies between measured A1C and plasma glucose levels should prompt consideration that the A1C assay may not be reliable for that individual, and one should consider using an A1C assay without interference or plasma blood glucose criteria for diagnosis. (An updated list of A1C assays with interferences is available at ngsp.org/interf.asp.)

If the patient has a test result near the margins of the diagnostic threshold, the clinician should follow the patient closely and repeat the test in 3–6 months. If using the oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT), fasting or carbohydrate restriction 3 days prior to the test should be avoided, as it can falsely elevate glucose levels.

Certain medications such as glucocorticoids, thiazide diuretics, some HIV medications, and atypical antipsychotics are known to increase the risk of diabetes and should be considered when deciding whether to screen.

3. Prevention or Delay of Type 2 Diabetes and Associated Comorbidities

Recommendation

3.1 Monitor for the development of type 2 diabetes in those with prediabetes at least annually, modified based on individual risk/benefit assessment. E

Lifestyle Behavior Change for Diabetes Prevention

Recommendations

3.2 Refer adults with overweight/obesity at high risk of type 2 diabetes, as typified by the Diabetes Prevention Program (DPP), to an intensive lifestyle behavior change program consistent with the DPP to achieve and maintain 7% loss of initial body weight, and increase moderate-intensity physical activity (such as brisk walking) to at least 150 minutes/week. A

3.3 A variety of eating patterns can be considered to prevent diabetes in individuals with prediabetes. B

3.5 Based on patient preference, certified technology-assisted diabetes prevention programs may be effective in preventing type 2 diabetes and should be considered. B

The strongest evidence supporting lifestyle intervention for diabetes prevention in the U.S. comes from the DPP trial, which demonstrated that intensive lifestyle intervention could reduce the risk of incident type 2 diabetes by 58% over 3 years. Evidence suggests that there is not an ideal percentage of calories from carbohydrate, protein, and fat to prevent diabetes.

Delivery and Dissemination of Lifestyle Behavior Change for Diabetes Prevention

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) developed the National DPP, a resource designed to bring evidence-based lifestyle change programs for preventing type 2 diabetes to communities, including eligible Medicare patients. An online resource includes locations of CDC-recognized diabetes prevention lifestyle change programs (cdc.gov/diabetes/prevention/find-a-program.html).

Pharmacologic Interventions

Recommendations

3.6 Metformin therapy for prevention of type 2 diabetes should be considered in adults with prediabetes, as typified by the DPP, especially those aged 25–59 years with BMI ≥35 kg/m2, higher fasting plasma glucose (e.g., ≥110 mg/dL), and higher A1C (e.g., ≥6.0%), and in women with prior GDM. A

3.7 Long-term use of metformin may be associated with biochemical vitamin B12 deficiency; consider periodic measurement of vitamin B12 levels in metformin-treated patients, especially in those with anemia or peripheral neuropathy. B

Various pharmacologic agents have been evaluated for diabetes prevention, and metformin has the strongest evidence base. However, no agents have been approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for diabetes prevention.

Prevention of Vascular Disease and Mortality

Recommendation

3.8 Prediabetes is associated with heightened cardiovascular (CV) risk; therefore, screening for and treatment of modifiable risk factors for cardiovascular disease (CVD) are suggested. B

Patient-Centered Care Goals

Recommendation

3.9 In adults with overweight/obesity at high risk of type 2 diabetes, care goals should include weight loss or prevention of weight gain, minimizing progression of hyperglycemia, and attention to CV risk and associated comorbidities. B

4. Comprehensive Medical Evaluation and Assessment of Comorbidities

Patient-Centered Collaborative Care

Recommendations

4.1 A patient-centered communication style that uses person-centered and strength-based language and active listening; elicits patient preferences and beliefs; and assesses literacy, numeracy, and potential barriers to care should be used to optimize patient health outcomes and health-related quality of life. B

A successful medical evaluation depends on beneficial interactions between the patient and the care team. Individuals with diabetes must assume an active role in their care. The person with diabetes, family or support people, and health care team should together formulate the management plan, which includes lifestyle management, to improve disease outcomes and well-being.

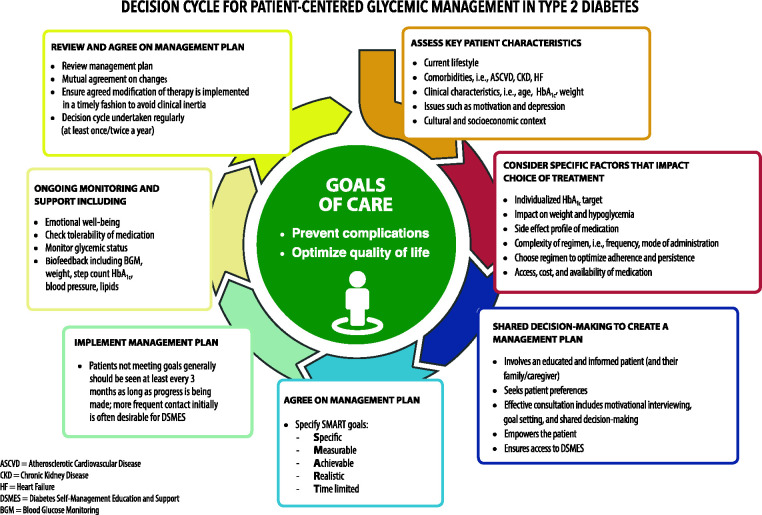

The goals of treatment for diabetes are to prevent or delay complications and optimize quality of life (Figure 4.1). The use of person-centered, strength-based, empowering language that is respectful and free of stigma in diabetes care and education can help to inform and motivate people. Language that shames and judges may undermine this effort. Use language that is person-centered (e.g., “person with diabetes” is preferred over “diabetic”).

FIGURE 4.1.

Decision cycle for patient-centered glycemic management in type 2 diabetes. HbA1c, glycated hemoglobin. Adapted from Davies MJ, D’Alessio DA, Fradkin J, et al. Diabetes Care 2018;41:2669–2701.

Comprehensive Medical Evaluation

Recommendations

- 4.3 A complete medical evaluation should be performed at the initial visit to:

- Confirm the diagnosis and classify diabetes. A

- Evaluate for diabetes complications and potential comorbid conditions. A

- Review previous treatment and risk factor control in patients with established diabetes. A

- Begin patient engagement in the formulation of a care management plan. A

- Develop a plan for continuing care. A

4.4 A follow-up visit should include most components of the initial comprehensive medical evaluation (see Table 4.1 in the complete 2022 Standards of Care). A

4.5 Ongoing management should be guided by the assessment of overall health status, diabetes complications, CV risk, hypoglycemia risk, and shared decision-making to set therapeutic goals. B

Immunizations

The importance of routine vaccinations for people living with diabetes has been elevated by the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic. Preventing avoidable infections not only directly prevents morbidity but also reduces hospitalizations, which may additionally reduce risk of acquiring infections such as COVID-19. Children and adults with diabetes should receive vaccinations according to age-appropriate recommendations.

Cancer

Patients with diabetes should be encouraged to undergo recommended age- and sex-appropriate cancer screenings and to reduce their modifiable cancer risk factors (obesity, physical inactivity, and smoking).

Cognitive Impairment/Dementia

See “13. OLDER ADULTS.”

Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease

Recommendation

4.10 Patients with type 2 diabetes or prediabetes and elevated liver enzymes or fatty liver on ultrasound should be evaluated for presence of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis and liver fibrosis. C

5. Facilitating Behavior Change and Well-Being to Improve Health Outcomes

Building positive health behaviors and maintaining psychological well-being are foundational for achieving diabetes treatment goals and maximizing quality of life. Essential to achieving these goals are DSMES, medical nutrition therapy (MNT), routine physical activity, smoking cessation counseling when needed, and psychosocial care

DSMES

Recommendations

5.1 In accordance with the national standards for DSMES, all people with diabetes should participate in diabetes self-management education and receive the support needed to facilitate the knowledge, decision-making, and skills mastery for diabetes self-care. A

5.2 There are four critical times to evaluate the need for diabetes self-management education to promote skills acquisition in support of regimen implementation, MNT, and well-being: at diagnosis, annually and/or when not meeting treatment targets, when complicating factors develop (medical, physical, psychosocial), and when transitions in life and care occur. E

5.4 DSMES should be patient-centered, may be offered in group or individual settings, and should be communicated with the entire diabetes care team. A

5.5 Digital coaching and digital self-management interventions can be effective methods to deliver DSMES. B

Evidence for the Benefits

Studies have found that DSMES is associated with improved diabetes knowledge and self-care behaviors, lower A1C, lower self-reported weight, improved quality of life, reduced all-cause mortality risk, positive coping behaviors, and reduced health care costs. Better outcomes were reported for DSMES interventions that were >10 hours over the course of 6–12 months.

MNT

Nutrition therapy plays an integral role in overall diabetes management, and people with diabetes should be actively engaged in education, self-management, and treatment planning with their health care team, including the collaborative development of an individualized eating plan. MNT delivered by a registered dietitian nutritionist is associated with A1C absolute decreases of 1.0–1.9% for people with type 1 diabetes and 0.3–2.0% for people with type 2 diabetes. See Table 5.1 in the complete 2022 Standards of Care for specific nutrition recommendations and refer to the ADA consensus report “Nutrition Therapy for Adults With Diabetes or Prediabetes: A Consensus Report” for more information on nutrition therapy.

Goals of Nutrition Therapy for Adults With Diabetes

- To promote and support healthful eating patterns, emphasizing a variety of nutrient-dense foods in appropriate portion sizes, to improve overall health and:

- Achieve and maintain body weight goals

- Attain individualized glycemic, blood pressure, and lipid goals

- Delay or prevent the complications of diabetes

To address individual nutrition needs based on personal and cultural preferences, health literacy and numeracy, access to healthful foods, willingness and ability to make behavioral changes, and existing barriers to change

To maintain the pleasure of eating by providing nonjudgmental messages about food choices while limiting food choices only when indicated by scientific evidence

To provide a person with diabetes the practical tools for developing healthy eating patterns rather than focusing on individual macronutrients, micronutrients, or single foods

Weight Management

Studies have demonstrated that a variety of eating plans, varying in macronutrient composition, can be used effectively and safely in the short term (1–2 years) to achieve weight loss in people with diabetes. The importance of providing guidance on an individualized meal plan containing nutrient-dense foods such as vegetables, fruits, legumes, dairy, lean sources of protein (including plant-based sources as well as lean meats, fish, and poultry), nuts, seeds, and whole grains, as well as guidance on achieving the desired energy deficit, cannot be overemphasized.

Physical Activity

Recommendations

5.27 Children and adolescents with type 1 or type 2 diabetes or prediabetes should engage in 60 minutes/day or more of moderate- or vigorous-intensity aerobic activity, with vigorous muscle-strengthening and bone-strengthening activities at least 3 days/week. C

5.28 Most adults with type 1 C and type 2 B diabetes should engage in 150 minutes or more of moderate- to vigorous-intensity aerobic activity per week, spread over at least 3 days/week, with no more than 2 consecutive days without activity. Shorter durations (minimum 75 minutes/week) of vigorous-intensity or interval training may be sufficient for younger and more physically fit individuals.

5.29 Adults with type 1 C and type 2 B diabetes should engage in 2–3 sessions/week of resistance exercise on nonconsecutive days.

5.30 All adults, and particularly those with type 2 diabetes, should decrease the amount of time spent in daily sedentary behavior. B Prolonged sitting should be interrupted every 30 minutes for blood glucose benefits. C

5.31 Flexibility training and balance training are recommended 2–3 times/week for older adults with diabetes. Yoga and tai chi may be included based on individual preferences to increase flexibility, muscular strength, and balance. C

5.32 Evaluate baseline physical activity and sedentary time. Promote increase in nonsedentary activities above baseline for sedentary individuals with type 1 E and type 2 B diabetes. Examples include walking, yoga, housework, gardening, swimming, and dancing.

Hypoglycemia

In individuals taking insulin and/or insulin secretagogues, physical activity may cause hypoglycemia if the medication dose or carbohydrate consumption is not adjusted for the exercise bout and post-bout impact on glucose. Patients need to be educated to check blood glucose levels before and after periods of exercise and about the potential prolonged effects of exercise, depending on its intensity and duration.

Exercise in the Presence of Microvascular Complications

For individuals with proliferative diabetic retinopathy or severe nonproliferative diabetic retinopathy, vigorous-intensity aerobic or resistance exercise may be contraindicated because of the risk of triggering vitreous hemorrhage or retinal detachment.

Individuals with peripheral neuropathy are at an increased risk of skin breakdown, infection, and Charcot joint destruction with some forms of exercise, due to decreased pain sensation. They should wear proper footwear and examine their feet daily to detect lesions early. Anyone with a foot injury or open sore should be restricted to non–weight-bearing activities.

Diabetes is associated with autonomic neuropathy, which can increase the risk of exercise-induced injury or adverse events through decreased cardiac responsiveness to exercise, postural hypotension, impaired thermoregulation, and greater susceptibility to hypoglycemia.

Smoking Cessation: Tobacco and e-Cigarettes

Recommendations

5.33 Advise all patients not to use cigarettes and other tobacco products or e-cigarettes. A

5.34 After identification of tobacco or e-cigarette use, include smoking cessation counseling and other forms of treatment as a routine component of diabetes care. A

Psychosocial Issues

Recommendations

5.36 Psychosocial care should be integrated with a collaborative, patient-centered approach and provided to all people with diabetes, with the goals of optimizing health outcomes and health-related quality of life. A

5.37 Psychosocial screening and follow-up may include, but are not limited to, attitudes about diabetes, expectations for medical management and outcomes, affect or mood, general and diabetes-related quality of life, available resources (financial, social, and emotional), and psychiatric history. E

5.38 Providers should consider assessment for symptoms of diabetes distress, depression, anxiety, disordered eating, and cognitive capacities using age-appropriate standardized and validated tools at the initial visit, at periodic intervals, and when there is a change in disease, treatment, or life circumstance. Including caregivers and family members in this assessment is recommended. B

Refer to the ADA’s Mental Health Resources for assessment tools and additional resources (professional.diabetes.org/mentalhealthsoc).

Diabetes Distress

Recommendation

5.40 Routinely monitor people with diabetes for diabetes distress, particularly when treatment targets are not met and/or at the onset of diabetes complications. B

Diabetes distress refers to significant negative psychological reactions related to emotional burdens and worries specific to an individual’s experience in having to manage a severe, complicated, and demanding chronic disease such as diabetes. The constant behavioral demands of diabetes self-management and the potential or actuality of disease progression are directly associated with reports of diabetes distress.

6. Glycemic Targets

Assessment of Glycemic Control

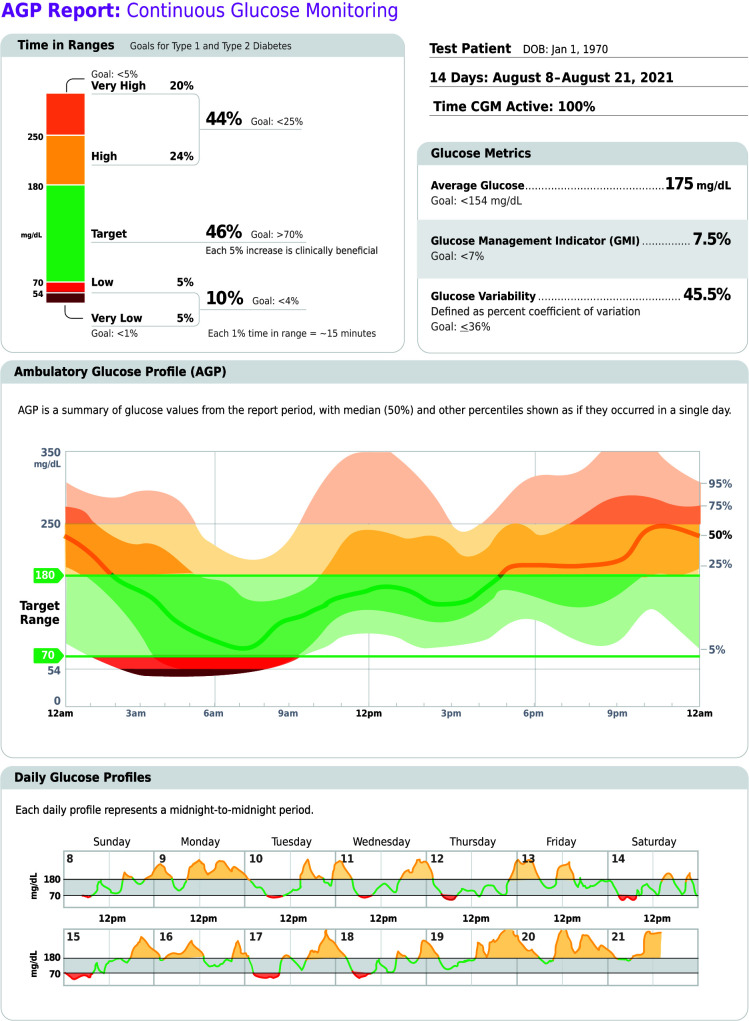

Glycemic control is assessed by A1C measurement, continuous glucose monitoring (CGM), and blood glucose monitoring (BGM). Clinical trials primarily use A1C to demonstrate the benefits of improved glycemic control. CGM serves an increasingly important role in managing the effectiveness and safety of treatment in many patients with type 1 diabetes and selected patients with type 2 diabetes.

Glycemic Assessment

Recommendations

6.1 Assess glycemic status (A1C or other glycemic measurement such as time in range [TIR] or glucose management indicator [GMI]) at least two times a year in patients who are meeting treatment goals (and who have stable glycemic control). E

6.2 Assess glycemic status at least quarterly and as needed in patients whose therapy has recently changed and/or who are not meeting glycemic goals. E

Glucose Assessment by CGM

Recommendations

6.3 Standardized, single-page glucose reports from CGM devices with visual cues, such as the ambulatory glucose profile (AGP), should be considered as a standard summary for all CGM devices. E

6.4 TIR is associated with the risk of microvascular complications and can be used for assessment of glycemic control. Additionally, time below target and time above target are useful parameters for the evaluation of the treatment regimen (Table 6.2). C

TABLE 6.2.

Standardized CGM Metrics for Clinical Care

| 1. Number of days CGM device is worn (recommend 14 days) | |

| 2. Percentage of time CGM device is active (recommend 70% of data from 14 days) | |

| 3. Mean glucose | |

| 4. GMI | |

| 5. Glycemic variability (%CV) target ≤36%* | |

| 6. TAR: % of readings and time >250 mg/dL (>13.9 mmol/L) | Level 2 hyperglycemia |

| 7. TAR: % of readings and time 181–250 mg/dL (10.1–13.9 mmol/L) | Level 1 hyperglycemia |

| 8. TIR: % of readings and time 70–180 mg/dL (3.9–10.0 mmol/L) | In range |

| 9. TBR: % of readings and time 54–69 mg/dL (3.0–3.8 mmol/L) | Level 1 hypoglycemia |

| 10. TBR: % of readings and time <54 mg/dL (<3.0 mmol/L) | Level 2 hypoglycemia |

%CV, percentage coefficient of variation; TAR, time above range; TBR, time below range.

Some studies suggest that lower %CV targets (<33%) provide additional protection against hypoglycemia for those receiving insulin or sulfonylureas. Adapted from Battelino T, Danne T, Bergenstal RM, et al. Diabetes Care 2019;42:1593–1603.

For many people with diabetes, glucose monitoring is key for achieving glycemic targets. It allows patients to evaluate their individual response to therapy and assess whether glycemic targets are being safely achieved.

CGM technology has grown rapidly in accuracy, affordability, and accessibilitiy. The GMI and data on TIR, hypoglycemia, and hyperglycemia are available to providers and patients via the AGP report (Figure 6.1), which offers visual cues and recommendations to assist in data interpretation and treatment decision-making. Table 6.2 summarizes CGM-derived metrics for assessment and glycemic management.

FIGURE 6.1.

Key points included in standard AGP report. Reprinted from Holt RIG, DeVries JH, Hess-Fischl A, et al. Diabetes Care 2021;44:2589–2625.

Glycemic Goals

Recommendations

6.5a An A1C goal for many nonpregnant adults of <7% (53 mmol/mol) without significant hypoglycemia is appropriate. A

6.5b If using AGP/GMI to assess glycemia, a parallel goal for many nonpregnant adults is TIR of >70% with time below range <4% and time <54 mg/dL <1% (Figure 6.1 and Table 6.2). B

6.6 On the basis of provider judgment and patient preference, achievement of lower A1C levels than the goal of 7% may be acceptable and even beneficial if it can be achieved safely without significant hypoglycemia or other adverse effects of treatment. B

6.7 Less stringent A1C goals (such as <8% [64 mmol/mol]) may be appropriate for patients with limited life expectancy or where the harms of treatment are greater than the benefits. B

Table 6.3 summarizes glycemic recommendations for many nonpregnant adults. For specific guidance, see “6. Glycemic Targets,” “14. Children and Adolescents,” and “15. Management of Diabetes in Pregnancy” in the complete 2022 Standards of Care. For information about glycemic targets for older adults, see Table 13.1 in “13. OLDER ADULTS.”

TABLE 6.3.

Summary of Glycemic Recommendations for Many Nonpregnant Adults With Diabetes

| A1C | <7.0% (53 mmol/mol)*# |

| Preprandial capillary plasma glucose | 80–130 mg/dL* (4.4–7.2 mmol/L) |

| Peak postprandial capillary plasma glucose† | <180 mg/dL* (10.0 mmol/L) |

More or less stringent glycemic goals may be appropriate for individual patients. #CGM may be used to assess glycemic target as noted in Recommendation 6.5b and Figure 6.1. Goals should be individualized based on duration of diabetes, age/life expectancy, comorbid conditions, known CVD or advanced microvascular complications, hypoglycemia unawareness, and individual patient considerations.

Postprandial glucose may be targeted if A1C goals are not met despite reaching preprandial glucose goals. Postprandial glucose measurements should be made 1–2 hours after the beginning of the meal, generally peak levels in patients with diabetes.

TABLE 13.1.

Framework for Considering Treatment Goals for Glycemia, Blood Pressure, and Dyslipidemia in Older Adults With Diabetes

| Patient Characteristics/Health Status | Rationale | Reasonable A1C Goal, % (mmol/mol)‡ | Fasting or Preprandial Glucose, mg/dL (mmol/L) | Bedtime Glucose, mg/dL (mmol/L) | Blood Pressure, mmHg | Lipids |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Healthy (few coexisting chronic illnesses, intact cognitive and functional status) | Longer remaining life expectancy | <7.0–7.5 (53–58) | 80–130 (4.4–7.2) | 80–180 (4.4–10.0) | <140/90 | Statin unless contraindicated or not tolerated |

| Complex/intermediate (multiple coexisting chronic illnesses* or 2+ instrumental ADL impairments or mild-to-moderate cognitive impairment) | Intermediate remaining life expectancy, high treatment burden, hypoglycemia vulnerability, fall risk | <8.0 (64) | 90–150 (5.0–8.3) | 100–180 (5.6–10.0) | <140/90 | Statin unless contraindicated or not tolerated |

| Very complex/poor health (LTC or end-stage chronic illnesses** or moderate-to-severe cognitive impairment or 2+ ADL impairments) | Limited remaining life expectancy makes benefit uncertain | Avoid reliance on A1C; glucose control decisions should be based on avoiding hypoglycemia and symptomatic hyperglycemia | 100–180 (5.6–10.0) | 110–200 (6.1–11.1) | <150/90 | Consider likelihood of benefit with statin |

This table represents a consensus framework for considering treatment goals for glycemia, blood pressure, and dyslipidemia in older adults with diabetes. The patient characteristic categories are general concepts. Not every patient will clearly fall into a particular category. Consideration of patient and caregiver preferences is an important aspect of treatment individualization. Additionally, a patient’s health status and preferences may change over time. ADL, activities of daily living.

A lower A1C goal may be set for an individual if achievable without recurrent or severe hypoglycemia or undue treatment burden.

Coexisting chronic illnesses are conditions serious enough to require medications or lifestyle management and may include arthritis, cancer, HF, depression, emphysema, falls, hypertension, incontinence, stage 3 or worse CKD, myocardial infarction, and stroke. “Multiple” means at least three, but many patients may have five or more.

The presence of a single end-stage chronic illness, such as stage 3–4 HF or oxygen-dependent lung disease, CKD requiring dialysis, or uncontrolled metastatic cancer, may cause significant symptoms or impairment of functional status and significantly reduce life expectancy. Adapted from Kirkman MS, Briscoe VJ, Clark N, et al. Diabetes Care 2012;35:2650–2664.

Hypoglycemia

The classification of hypoglycemia level is summarized in Table 6.4.

TABLE 6.4.

Classification of Hypoglycemia

| Glycemic Criteria/Description | |

|---|---|

| Level 1 | Glucose <70 mg/dL (3.9 mmol/L) and ≥54 mg/dL (3.0 mmol/L) |

| Level 2 | Glucose <54 mg/dL (3.0 mmol/L) |

| Level 3 | A severe event characterized by altered mental and/or physical status requiring assistance for treatment of hypoglycemia |

Reprinted from Agiostratidou G, Anhalt H, Ball D, et al. Diabetes Care 2017;40:1622–1630.

Recommendations

6.9 Occurrence and risk for hypoglycemia should be reviewed at every encounter and investigated as indicated. C

6.10 Glucose (approximately 15–20 g) is the preferred treatment for the conscious individual with blood glucose <70 mg/dL (3.9 mmol/L), although any form of carbohydrate that contains glucose may be used. Fifteen minutes after treatment, if BGM shows continued hypoglycemia, the treatment should be repeated. Once the BGM or glucose pattern is trending up, the individual should consume a meal or snack to prevent recurrence of hypoglycemia. B

6.11 Glucagon should be prescribed for all individuals at increased risk of level 2 or 3 hypoglycemia, so that it is available should it be needed. Caregivers, school personnel, or family members providing support to these individuals should know where it is and when and how to administer it. Glucagon administration is not limited to health care professionals. E

6.12 Hypoglycemia unawareness or one or more episodes of level 3 hypoglycemia should trigger hypoglycemia avoidance education and reevaluation and adjustment of the treatment regimen to decrease hypoglycemia. E

6.13 Insulin-treated patients with hypoglycemia unawareness, one level 3 hypoglycemic event, or a pattern of unexplained level 2 hypoglycemia should be advised to raise their glycemic targets to strictly avoid hypoglycemia for at least several weeks in order to partially reverse hypoglycemia unawareness and reduce risk of future episodes. A

6.14 Ongoing assessment of cognitive function is suggested with increased vigilance for hypoglycemia by the clinician, patient, and caregivers if impaired or declining cognition is found. B

7. Diabetes Technology

Diabetes technology includes the hardware, devices, and software that people with diabetes use to help manage their diabetes. This includes insulin delivery technology such as insulin pumps (also called continuous subcutaneous insulin infusion [CSII]) and connected insulin pens, as well as glucose monitoring via CGM system or glucose meter. More recently, diabetes technology has expanded to include hybrid devices that both monitor glucose and deliver insulin, some with varying degrees of automation. Apps can also provide diabetes self-management support.

General Device Principles

Recommendations

7.1 The type(s) and selection of devices should be individualized based on a person’s specific needs, desires, skill level, and availability of devices. In the setting of an individual whose diabetes is partially or wholly managed by someone else (e.g., a young child or a person with cognitive impairment), the caregiver’s skills and desires are integral to the decision-making process. E

7.2 When prescribing a device, ensure that people with diabetes/caregivers receive initial and ongoing education and training, either in-person or remotely, and regular evaluation of technique, results, and their ability to use data, including uploading/sharing data (if applicable), to adjust therapy. C

7.5 Initiation of CGM, CSII, and/or automated insulin delivery (AID) early in the treatment of diabetes can be beneficial depending on a person’s/caregiver’s needs and preferences. C

BGM

Recommendations

7.7 People who are on insulin using BGM should be encouraged to check when appropriate based on their insulin regimen. This may include checking when fasting, prior to meals and snacks, at bedtime, prior to exercise, when low blood glucose is suspected, after treating low blood glucose levels until they are normoglycemic, and prior to and while performing critical tasks such as driving. B

7.9 Although BGM in individuals on noninsulin therapies has not consistently shown clinically significant reductions in A1C, it may be helpful when altering diet, physical activity, and/or medications (particularly medications that can cause hypoglycemia) in conjunction with a treatment adjustment program. E

CGM

Table 6.2 summarizes CGM-derived glycemic metrics, and Table 7.3 defines the available types of CGM devices.

TABLE 7.3.

CGM Devices

| Real-time CGM (rtCGM) | CGM systems that measure and display glucose levels continuously |

| Intermittently scanned CGM (isCGM) | CGM systems that measure glucose levels continuously but only display glucose values when swiped by a reader or a smartphone |

| Professional CGM | CGM devices that are placed on the patient in the provider’s office (or with remote instruction) and worn for a discrete period of time (generally 7–14 days). Data may be blinded or visible to the person wearing the device. The data are used to assess glycemic patterns and trends. These devices are not fully owned by the patient—they are clinic-based devices, as opposed to the patient-owned rtCGM or isCGM CGM devices. |

Recommendations

7.11 Real-time CGM (rtCGM) A or intermittently scanned CGM (isCGM) B should be offered for diabetes management in adults with diabetes on multiple daily injections (MDI) or CSII who are capable of using devices safely (either by themselves or with a caregiver). The choice of device should be made based on patient circumstances, desires, and needs.

7.12 rtCGM A or isCGM C can be used for diabetes management in adults with diabetes on basal insulin who are capable of using devices safely (either by themselves or with a caregiver). The choice of device should be made based on patient circumstances, desires, and needs.

7.15 In patients on MDI and CSII, rtCGM devices should be used as close to daily as possible for maximal benefit. A is CGM devices should be scanned frequently, at a minimum once every 8 hours. A

7.16 When used as an adjunct to pre- and postprandial BGM, CGM can help to achieve A1C targets in diabetes and pregnancy. B

7.17 Periodic use of rtCGM or isCGM or use of professional CGM can be helpful for diabetes management in circumstances where continuous use of CGM is not appropriate, desired, or available. C

7.18 Skin reactions, either due to irritation or allergy, should be assessed and addressed to aid in successful use of devices. E

Inpatient Care

Recommendation

7.29 Patients who are in a position to safely use diabetes devices should be allowed to continue using them in an inpatient setting or during outpatient procedures when proper supervision is available. E

Other Technologies

See “7. Diabetes Technology” in the complete 2022 Standards of Care for more information on insulin delivery, including insulin syringes, pens, connected pens, pumps, and AID systems, which combine insulin pump and CGM with software automating varying degrees of insulin delivery; software systems; and digital health systems that combine technology with online coaching.

The Future

The most important component in the rapid pace of technology development is the patient. Having a device or application does not change outcomes unless the individual engages with it to create positive health benefits. The health care team should assist the patient in device/program selection and support its use through ongoing education. Although there is not yet technology that completely eliminates the self-care tasks necessary for treating diabetes, the tools described in this section can make diabetes easier to manage.

8. Obesity and Weight Management for the Prevention and Treatment of Type 2 Diabetes

Strong evidence exists that obesity management can delay the progression from prediabetes to type 2 diabetes and is highly beneficial in the treatment of type 2 diabetes. Modest weight loss improves glycemic control and reduces the need for glucose-lowering medications, and more intensive dietary energy restriction can substantially reduce A1C and fasting glucose and promote sustained diabetes remission through at least 2 years. Metabolic surgery strongly improves glycemic control and often leads to remission of diabetes, improved quality of life, improved CV outcomes, and reduced mortality.

Assessment

Recommendations

8.1 Use person-centered, nonjudgmental language that fosters collaboration between patients and providers, including people-first language (e.g., “person with obesity” rather than “obese person”). E

8.2 Measure height and weight and calculate BMI at annual visits or more frequently. Assess weight trajectory to inform treatment considerations. E

8.3 Based on clinical considerations such as the presence of comorbid heart failure (HF) or significant unexplained weight gain or loss, weight may need to be monitored and evaluated more frequently. B If deterioration of medical status is associated with significant weight gain or loss, inpatient evaluation should be considered, especially focused on associations between medication use, food intake, and glycemic status. E

8.4 Accommodations should be made to provide privacy during weighing. E

Table 8.1 summarizes treatment options for overweight and obesity in type 2 diabetes.

TABLE 8.1.

Treatment Options for Overweight and Obesity in Type 2 Diabetes

| Treatment | BMI Category, kg/m2 | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 25.0–26.9 (or 23.0–24.9*) | 27.0–29.9 (or 25.0–27.4*) | ≥30.0 (or ≥27.5*) | |

| Diet, physical activity, and behavioral counseling | † | † | † |

| Pharmacotherapy | † | † | |

| Metabolic surgery | † | ||

Recommended cut points for Asian-American individuals (expert opinion).

Treatment may be indicated for select motivated patients.

Diet, Physical Activity, and Behavioral Therapy

Recommendations

8.5 Diet, physical activity, and behavioral therapy to achieve and maintain ≥5% weight loss is recommended for most people with type 2 diabetes and overweight or obesity. Additional weight loss usually results in further improvements in control of diabetes and CV risk. B

8.6 Such interventions should include a high frequency of counseling (≥16 sessions in 6 months) and focus on dietary changes, physical activity, and behavioral strategies to achieve a 500–750 kcal/day energy deficit. A

8.9 Evaluate systemic, structural, and socioeconomic factors that may impact dietary patterns and food choices, such as food insecurity and hunger, access to healthful food options, cultural circumstances, and SDOH. C

8.10 For those who achieve weight loss goals, long-term (≥1 year) weight maintenance programs are recommended when available. Such programs should, at minimum, provide monthly contact and support, recommend ongoing monitoring of body weight (weekly or more frequently) and other self-monitoring strategies, and encourage regular physical activity (200–300 minutes/week). A

8.11 Short-term dietary intervention using structured, very-low-calorie diets (800–1,000 kcal/day) may be prescribed for carefully selected individuals by trained practitioners in medical settings with close monitoring. Long-term, comprehensive weight maintenance strategies and counseling should be integrated to maintain weight loss. B

8.12 There is no clear evidence that dietary supplements are effective for weight loss. A

Pharmacotherapy

Recommendations

8.13 When choosing glucose-lowering medications for people with type 2 diabetes and overweight or obesity, consider the medication’s effect on weight. B

8.14 Whenever possible, minimize medications for comorbid conditions that are associated with weight gain. E

8.16 If a patient’s response to weight loss medication is effective (typically defined as >5% weight loss after 3 months’ use), further weight loss is likely with continued use. When early response is insufficient (typically <5% weight loss after 3 months’ use) or if there are significant safety or tolerability issues, consider discontinuation of the medication and evaluate alternative medications or treatment approaches. A

Approved Weight Loss Medications

Nearly all FDA-approved medications for weight loss have been shown to improve glycemic control in patients with type 2 diabetes and delay progression to type 2 diabetes in patients at risk. Medications approved by the FDA for the treatment of obesity are summarized in Table 8.2 in the complete 2022 Standards of Care.

Metabolic Surgery

Recommendations

8.19 Metabolic surgery should be performed in highvolume centers with multidisciplinary teams knowledgeable about and experienced in the management of obesity, diabetes, and gastrointestinal surgery. E

8.20 People being considered for metabolic surgery should be evaluated for comorbid psychological conditions and social and situational circumstances that have the potential to interfere with surgery outcomes. B

8.21 People who undergo metabolic surgery should receive long-term medical and behavioral support and routine monitoring of micronutrient, nutritional, and metabolic status. B

8.22 If postbariatric hypoglycemia is suspected, clinical evaluation should exclude other potential disorders contributing to hypoglycemia, and management includes education, MNT with a dietitian experienced in postbariatric hypoglycemia, and medication treatment, as needed. A CGM should be considered as an important adjunct to improve safety by alerting patients to hypoglycemia, especially for those with severe hypoglycemia or hypoglycemia unawareness. E

9. Pharmacologic Approaches to Glycemic Treatment

Pharmacologic Therapy for Adults With Type 1 Diabetes

See “9. Pharmacologic Approaches to Glycemic Treatment” in the complete 2022 Standards of Care for detailed information on pharmacologic approaches to type 1 diabetes management in adults.

Pharmacologic Therapy for Adults With Type 2 Diabetes

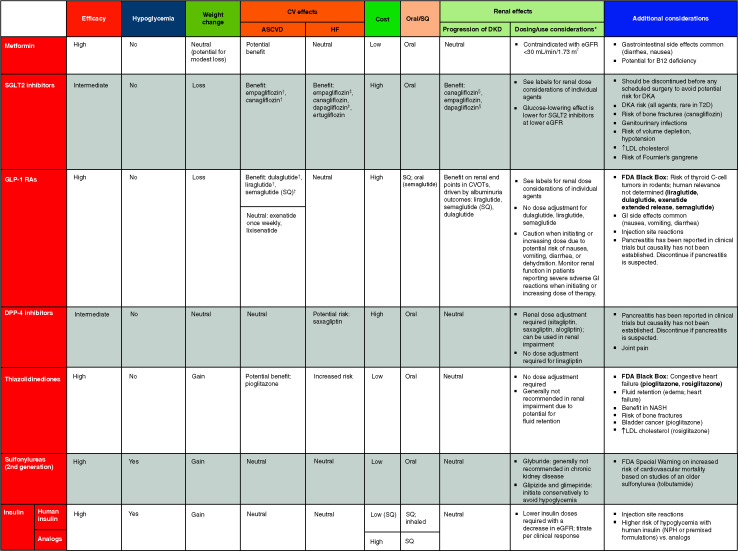

Table 9.2 and Figure 9.3 provide details for informed decision-making on pharmacologic treatment for the management of glycemia in type 2 diabetes.

TABLE 9.2.

Drug-Specific and Patient Factors to Consider When Selecting Antihyperglycemic Treatment in Adults With Type 2 Diabetes

For agent-specific dosing recommendations, please refer to the manufacturers’ prescribing information.

FDA-approved for CVD benefit.

FDA-approved for HF indication.

FDA-approved for CKD indication. CVOT, cardiovascular outcomes trial; DPP-4, dipeptidyl peptidase 4; GLP-1 RA, glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor agonist; NASH, nonalcoholic steatohepatitis; SQ, subcutaneous; T2D, type 2 diabetes.

FIGURE 9.3.

Pharmacologic treatment of hyperglycemia in adults with type 2 diabetes. 2022 ADA Professional Practice Committee (PPC) adaptation of Davies MJ, D’Alessio DA, Fradkin J, et al. Diabetes Care 2018;41:2669–2701 and Buse JB, Wexler DJ, Tsapas A, et al. Diabetes Care 2020;43:487–493. For appropriate context, see Figure 4.1. The 2022 ADA PPC adaptation emphasizes incorporation of therapy rather than sequential add-on, which may require adjustment of current therapies. Therapeutic regimen should be tailored to comorbidities, patient-centered treatment factors, and management needs. Refer to sections 10 and 11 in the complete 2022 Standards of Care for detailed discussions of CVD and CKD risk management. CVOT, cardiovascular outcomes trial; DPP-4i, dipeptidyl peptidase 4 inhibitor; GLP-1 RA, glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor agonist; SGLT2i, sodium–glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitor; SU, sulfonylurea; TZD, thiazolidinedione.

Recommendations

9.4a First-line therapy depends on comorbidities, patient-centered treatment factors, and management needs and generally includes metformin and comprehensive lifestyle modification. A

9.4b Other medications (glucagon-like peptide 1 [GLP-1] receptor agonists, sodium–glucose cotransporter 2 [SGLT2] inhibitors), with or without metformin based on glycemic needs, are appropriate initial therapy for individuals with type 2 diabetes with or at high risk for atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD), HF, and/or chronic kidney disease (CKD) (Figure 9.3). A

9.5 Metformin should be continued upon initiation of insulin therapy (unless contraindicated or not tolerated) for ongoing glycemic and metabolic benefits. A

9.6 Early combination therapy can be considered in some patients at treatment initiation to extend the time to treatment failure. A

9.7 The early introduction of insulin should be considered if there is evidence of ongoing catabolism (weight loss), if symptoms of hyperglycemia are present, or when A1C levels (>10% [86 mmol/mol]) or blood glucose levels (≥300 mg/dL [16.7 mmol/L]) are very high. E

9.8 A patient-centered approach should guide the choice of pharmacologic agents. Consider the effects on CV and renal comorbidities, efficacy, hypoglycemia risk, impact on weight, cost and access, risk for side effects, and patient preferences (Table 9.2 and Figure 9.3). E

9.9 Among individuals with type 2 diabetes who have established ASCVD or indicators of high CV risk, established CKD, or HF, an SGLT2 inhibitor and/or GLP-1 receptor agonist with demonstrated CVD benefit (Table 9.2 and Figure 9.3) is recommended as part of the glucose-lowering regimen and comprehensive CV risk reduction, independent of A1C and in consideration of patient-specific factors. A

9.10 In patients with type 2 diabetes, a GLP-1 receptor agonist is preferred to insulin when possible. A

9.11 If insulin is used, combination therapy with a GLP-1 receptor agonist is recommended for greater efficacy and durability of treatment effect. A

9.13 Medication regimen and medication-taking behavior should be reevaluated at regular intervals (every 3–6 months) and adjusted as needed to incorporate specific factors that impact choice of treatment (Figure 4.1 and Table 9.2). E

9.14 Clinicians should be aware of the potential for overbasalization with insulin therapy. Clinical signals that may prompt evaluation of overbasalization include basal dose more than 0.5 IU/kg/day, high bedtime-morning or post-preprandial glucose differential, hypoglycemia (aware or unaware), and high glycemic variability. Indication of overbasalization should prompt reevaluation to further individualize therapy. E

Both comprehensive lifestyle modifications and pharmacotherapy should begin at diagnosis. Glycemic status should be assessed, with treatment modified regularly (e.g., at least twice yearly if stable and more often if not at goal) to achieve treatment goals and to avoid therapeutic inertia. Not all treatment modifications involve sequential add-on therapy, but may involve switching therapy or weaning current therapy to accommodate for changes in the patient’s overall goals (e.g., the initiation of agents for reasons beyond glycemic benefit). See “9. Pharmacologic Approaches to Glycemic Treatment” in the complete 2022 Standards of Care for more detailed information on pharmacologic approaches to type 2 diabetes management in adults, including Figure 9.4 for guidance on intensifying to injectable therapies in type 2 diabetes.

10. CVD and Risk Management

ASCVD—defined as coronary heart disease, cerebrovascular disease, or peripheral arterial disease (PAD) presumed to be of atherosclerotic origin—is the leading cause of morbidity and mortality for individuals with diabetes. Controlling individual CV risk factors helps prevent or slow ASCVD in people with diabetes. HF is another major cause of morbidity and mortality from CVD. Studies show HF (with preserved ejection fraction [HFpEF] or reduced ejection fraction [HFrEF]) is twofold higher in people with diabetes compared to those without.

Risk factors, including duration of diabetes, obesity/overweight, hypertension, dyslipidemia, smoking, a family history of premature coronary disease, CKD, and the presence of albuminuria, should be assessed at least annually in all patients with diabetes to prevent and manage both ASCVD and HF.

The Risk Calculator

The American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association ASCVD risk calculator (Risk Estimator Plus) is generally a useful tool to estimate 10-year risk of an individual’s first ASCVD event (available online at tools.acc.org/ASCVD-Risk-Estimator-Plus).

Hypertension/Blood Pressure Control

Hypertension, defined as a sustained blood pressure ≥140/90 mmHg, is common among patients with either type 1 or type 2 diabetes.

Screening and Diagnosis

Recommendations

10.1 Blood pressure should be measured at every routine clinical visit. When possible, patients found to have elevated blood pressure (≥140/90 mmHg) should have blood pressure confirmed using multiple readings, including measurements on a separate day, to diagnose hypertension. A Patients with blood pressure ≥180/110 mmHg and CVD could be diagnosed with hypertension at a single visit. E

10.2 All hypertensive patients with diabetes should monitor their blood pressure at home. A

Treatment Goals

Recommendations

10.3 For patients with diabetes and hypertension, blood pressure targets should be individualized through a shared decision-making process that addresses CV risk, potential adverse effects of antihypertensive medications, and patient preferences. B

10.4 For individuals with diabetes and hypertension at higher CV risk (existing ASCVD or 10-year ASCVD risk ≥15%), a blood pressure target of <130/80 mmHg may be appropriate, if it can be safely attained. B

10.5 For individuals with diabetes and hypertension at lower risk for CVD (10-year ASCVD risk <15%), treat to a blood pressure target of <140/90 mmHg. A

Treatment Strategies

Lifestyle Intervention

Recommendation

10.7 For patients with blood pressure >120/80 mmHg, lifestyle intervention consists of weight loss when indicated, a Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH)-style eating pattern, including reducing sodium and increasing potassium intake, moderation of alcohol intake, and increased physical activity. A

Pharmacologic Interventions

Recommendations

10.8 Patients with confirmed office-based blood pressure ≥140/90 mmHg should, in addition to lifestyle therapy, have prompt initiation and timely titration of pharmacologic therapy to achieve blood pressure goals. A

10.9 Patients with confirmed office-based blood pressure ≥160/100 mmHg should, in addition to lifestyle therapy, have prompt initiation and timely titration of two drugs or a single-pill combination of drugs demonstrated to reduce CV events in patients with diabetes. A

10.10 Treatment for hypertension should include drug classes demonstrated to reduce CV events in patients with diabetes. A ACE inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs) are recommended first-line therapy for hypertension in people with diabetes and coronary artery disease (CAD). A

10.11 Multiple-drug therapy is generally required to achieve blood pressure targets. However, combinations of ACE inhibitors and ARBs and combinations of ACE inhibitors or ARBs with direct renin inhibitors should not be used. A

10.12 An ACE inhibitor or ARB, at the maximum tolerated dose indicated for blood pressure treatment, is the recommended first-line treatment for hypertension in patients with diabetes and urinary albumin-to-creatinine ratio (UACR) ≥300 mg/g creatinine A or 30–299 mg/g creatinine. B If one class is not tolerated, the other should be substituted. B

10.13 For patients treated with an ACE inhibitor, ARB, or diuretic, serum creatinine/estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) and serum potassium levels should be monitored at least annually. B

Resistant Hypertension

Recommendation

10.14 Patients with hypertension who are not meeting blood pressure targets on three classes of antihypertensive medications (including a diuretic) should be considered for mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist (MRA) therapy. B

Lipid Management

Lifestyle Intervention

Recommendations

10.15 Lifestyle modification focusing on weight loss (if indicated); application of a Mediterranean style or DASH eating pattern; reduction of saturated fat and trans fat; increase of dietary n-3 fatty acids, viscous fiber, and plant stanols/sterols intake; and increased physical activity should be recommended to improve the lipid profile and reduce the risk of developing ASCVD in patients with diabetes. A

10.16 Intensify lifestyle therapy and optimize glycemic control for patients with elevated triglyceride levels (≥150 mg/dL [1.7 mmol/L]) and/or low HDL cholesterol (<40 mg/dL [1.0 mmol/L] for men, <50 mg/dL [1.3 mmol/L] for women). C

Ongoing Therapy and Monitoring With Lipid Panel

Recommendations

10.17 In adults not taking statins or other lipid-lowering therapy, it is reasonable to obtain a lipid profile at the time of diabetes diagnosis, at an initial medical evaluation, and every 5 years thereafter if under the age of 40 years, or more frequently if indicated. E

10.18 Obtain a lipid profile at initiation of statins or other lipid-lowering therapy, 4–12 weeks after initiation or a change in dose, and annually thereafter, as it may help to monitor the response to therapy and inform medication adherence. E

Statin Treatment

Primary Prevention

Recommendations

10.19 For patients with diabetes aged 40–75 years without ASCVD, use moderate-intensity statin therapy in addition to lifestyle therapy. A

10.20 For patients with diabetes aged 20–39 years with additional ASCVD risk factors, it may be reasonable to initiate statin therapy in addition to lifestyle therapy. C

10.21 In patients with diabetes at higher risk, especially those with multiple ASCVD risk factors or aged 50–70 years, it is reasonable to use high-intensity statin therapy. B

10.22 In adults with diabetes and 10-year ASCVD risk of 20% or higher, it may be reasonable to add ezetimibe to maximally tolerated statin therapy to reduce LDL cholesterol levels by 50% or more. C

Secondary Prevention

Recommendations

10.23 For patients of all ages with diabetes and ASCVD, high-intensity statin therapy should be added to lifestyle therapy. A

10.24 For patients with diabetes and ASCVD considered very high risk using specific criteria, if LDL cholesterol is ≥70 mg/dL on maximally tolerated statin dose, consider adding additional LDL-lowering therapy (such as ezetimibe or PCSK9 inhibitor). A

10.25 For patients who do not tolerate the intended intensity, the maximally tolerated statin dose should be used. E

10.26 In adults with diabetes aged >75 years already on statin therapy, it is reasonable to continue statin treatment. B

10.27 In adults with diabetes aged >75 years, it may be reasonable to initiate statin therapy after discussion of potential benefits and risks. C

See “10. Cardiovascular Disease and Risk Management” in the complete 2022 Standards of Care for detailed guidance on statin therapy in patients with diabetes.

Treatment of Other Lipoprotein Fractions or Targets

Recommendations

10.29 For patients with fasting triglyceride levels ≥500 mg/dL, evaluate for secondary causes of hypertriglyceridemia and consider medical therapy to reduce the risk of pancreatitis. C

10.30 In adults with moderate hypertriglyceridemia (fasting or nonfasting triglycerides 175–499 mg/dL), clinicians should address and treat lifestyle factors (obesity and metabolic syndrome), secondary factors (diabetes, chronic liver or kidney disease and/or nephrotic syndrome, hypothyroidism), and medications that raise triglycerides. C

10.31 In patients with ASCVD or other CV risk factors on a statin with controlled LDL cholesterol but elevated triglycerides (135–499 mg/dL), the addition of icosapent ethyl can be considered to reduce CV risk. A

Other Combination Therapy

Recommendations

10.32 Statin plus fibrate combination therapy has not been shown to improve ASCVD outcomes and is generally not recommended. A

10.33 Statin plus niacin combination therapy has not been shown to provide additional CV benefit above statin therapy alone, may increase the risk of stroke with additional side effects, and is generally not recommended. A

Diabetes Risk With Statin Use

Although several studies have reported a modestly increased risk of incident diabetes with statin use, the CV event rate reduction with statins far outweighs the risk of incident diabetes even for patients at highest risk for diabetes.

Lipid-Lowering Agents and Cognitive Function

Although concerns have been raised regarding a potential adverse impact of lipid-lowering agents on cognitive function, several lines of evidence point against this association.

Antiplatelet Agents

Recommendations

10.34 Use aspirin therapy (75–162 mg/day) as a secondary prevention strategy in those with diabetes and a history of ASCVD. A

10.35 For patients with ASCVD and documented aspirin allergy, clopidogrel (75 mg/day) should be used. B

10.36 Dual antiplatelet therapy (with low-dose aspirin and a P2Y12 inhibitor) is reasonable for a year after an acute coronary syndrome and may have benefits beyond this period. A

10.37 Long-term treatment with dual antiplatelet therapy should be considered for patients with prior coronary intervention, high ischemic risk, and low bleeding risk to prevent major adverse cardiovascular (MACE) events. A

10.38 Combination therapy with aspirin plus low-dose rivaroxaban should be considered for patients with stable CAD and/or PAD and low bleeding risk to prevent major adverse limb and CV events. A

10.39 Aspirin therapy (75–162 mg/day) may be considered as a primary prevention strategy in those with diabetes who are at increased CV risk, after a comprehensive discussion with the patient on the benefits versus the comparable increased risk of bleeding. A

CVD

Screening

Recommendations

10.40 In asymptomatic patients, routine screening for CAD is not recommended as it does not improve outcomes as long as ASCVD risk factors are treated. A

10.41 Consider investigations for CAD in the presence of any of the following: atypical cardiac symptoms (e.g., unexplained dyspnea, chest discomfort); signs or symptoms of associated vascular disease, including carotid bruits, transient ischemic attack, stroke, claudication, or PAD; or electrocardiogram abnormalities (e.g., Q waves). E

Treatment

Recommendations

10.42a In patients with type 2 diabetes and established ASCVD, multiple ASCVD risk factors, or diabetic kidney disease (DKD), an SGLT2 inhibitor with demonstrated CV benefit is recommended to reduce the risk of MACE and/or HF hospitalization. A

10.42b In patients with type 2 diabetes and established ASCVD or multiple risk factors for ASCVD, a GLP-1 receptor agonist with demonstrated CV benefit is recommended to reduce the risk of MACE. A

10.42c In patients with type 2 diabetes and established ASCVD or multiple risk factors for ASCVD, combined therapy with an SGLT2 inhibitor with demonstrated CV benefit and a GLP-1 receptor agonist with demonstrated CV benefit may be considered for additive reduction in the risk of adverse CV and kidney events. A

10.43 In patients with type 2 diabetes and established HFrEF, an SGLT2 inhibitor with proven benefit in this patient population is recommended to reduce risk of worsening HF and CV death. A

10.44 In patients with known ASCVD, particularly CAD, ACE inhibitor or ARB therapy is recommended to reduce the risk of CV events. A

10.45 In patients with prior myocardial infarction, β-blockers should be continued for 3 years after the event. B

10.46 Treatment of patients with HFrEF should include a β-blocker with proven CV outcomes benefit, unless otherwise contraindicated. A

10.47 In patients with type 2 diabetes with stable HF, metformin may be continued for glucose lowering if eGFR remains >30 mL/min/1.73 m2 but should be avoided in unstable or hospitalized patients with HF. B

Cardiac Testing

Candidates for advanced or invasive cardiac testing include those with 1) typical or atypical cardiac symptoms and 2) an abnormal resting electrocardiogram.

11. CKD and Risk Management

Epidemiology of Diabetes and CKD

CKD is diagnosed by the persistent elevation of urinary albumin excretion (albuminuria), low eGFR, or other manifestations of kidney damage. CKD attributable to diabetes (DKD) typically develops after diabetes duration of 10 years in type 1 diabetes but may be present at diagnosis of type 2 diabetes. CKD can progress to end-stage renal disease (ESRD) requiring dialysis or kidney transplantation and is the leading cause of ESRD in the United States. CKD also markedly increases CV risk.

Screening

Recommendations

11.1a At least annually, urinary albumin (e.g., spot UACR) and eGFR should be assessed in patients with type 1 diabetes with duration of ≥5 years and in all patients with type 2 diabetes regardless of treatment. B

11.1b Patients with diabetes and urinary albumin ≥300 mg/g creatinine and/or an eGFR 30–60 mL/min/1.73 m2 should be monitored twice annually to guide therapy. B

Treatment

Recommendations

11.2 Optimize glucose control to reduce the risk or slow the progression of CKD. A

11.3a For patients with type 2 diabetes and DKD, use of an SGLT2 inhibitor in patients with an eGFR ≥25 mL/min/1.73 m2 and urinary albumin ≥300 mg/g creatinine is recommended to reduce CKD progression and CV events. A

11.3b In patients with type 2 diabetes and CKD, consider use of SGLT2 inhibitors additionally for CV risk reduction when eGFR and urinary albumin creatinine are ≥25 mL/min/1.73 m2 or ≥300 mg/g, respectively (Figure 9.3). A

11.3c In patients with CKD who are at increased risk for CV events or CKD progression or are unable to use an SGLT2 inhibitor, a nonsteroidal MRA (finerenone) is recommended to reduce CKD progression and CV events (Table 9.2). A

11.4 Optimization of blood pressure control and reduction in blood pressure variability to reduce the risk or slow the progression of CKD is recommended. A

11.5 Do not discontinue renin-angiotensin system blockade for minor increases in serum creatinine (≤30%) in the absence of volume depletion. A

11.6 For people with nondialysis-dependent stage 3 or higher CKD, dietary protein intake should be a maximum of 0.8 g/kg body weight per day (the recommended daily allowance). A For patients on dialysis, higher levels of dietary protein intake should be considered, since malnutrition is a major problem in some dialysis patients. B

11.9 An ACE inhibitor or an ARB is not recommended for the primary prevention of CKD in patients with diabetes who have normal blood pressure, normal UACR (<30 mg/g creatinine), and normal eGFR. A

11.10 Patients should be referred for evaluation by a nephrologist if they have an eGFR <30 mL/min/1.73 m2. A

11.11 Promptly refer to a nephrologist for uncertainty about the etiology of kidney disease, difficult management issues, and rapidly progressing kidney disease. A

Diagnosis and Staging of DKD

DKD is a clinical diagnosis made and staged based on the presence and degree of albuminuria and/or reduced eGFR in the absence of signs or symptoms of other primary causes of kidney damage. Two of three specimens of UACR collected within a 3- to 6-month period should be abnormal before considering a patient to have albuminuria. eGFR should be calculated from serum creatinine using a validated formula. The Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration (CKD-EPI) equation is generally preferred.

Interventions

Selection of Glucose-Lowering Medications for Patients With CKD

Metformin may be considered as the initial glucose-lowering medication in the setting of CKD. However, it is contraindicated in patients with an eGFR <30 mL/min/1.73 m2; eGFR should be monitored while taking metformin; the benefits and risks of continuing treatment should be reassessed when eGFR falls to <45 mL/min/1.73 m2; metformin should not be initiated for patients with an eGFR <45 mL/min/1.73 m2; and metformin should be temporarily discontinued at the time of or before iodinated contrast imaging procedures in patients with eGFR 30–60 mL/min/1.73 m2.

SGLT2 inhibitors should be given to all patients with stage 3 CKD or higher and type 2 diabetes regardless of glycemic control, as they slow CKD progression and reduce HF risk independent of glycemic control. Randomized clinical outcome trials have not demonstrated increased risk of acute kidney injury with SGLT2 inhibitor use. Empagliflozin and dapagliflozin are approved by the FDA for use with eGFR 25–45 mL/min/1.73 m2 for kidney/HF outcomes. Empagliflozin can be started with eGFR >30 mL/min/1.73 m2 (though pivotal trials for each included participants with eGFR ≥30 mL/min/1.73 m2 and demonstrated benefit in subgroups with low eGFR). Canagliflozin is approved to be initiated to eGFR levels of 30 mL/min/1.73 m2.

GLP-1 receptor agonists are suggested for CV risk reduction if such risk is a predominant problem, as they reduce risks of CVD events and hypoglycemia and appear to possibly slow CKD progression. Some GLP-1 receptor agonists require dose adjustment for reduced eGFR (the majority—liraglutide, dulaglutide, semaglutide—do not require it).

MRAs in CKD

Finerenone may reduce CKD progression and CVD in patients with advanced CKD, although monitoring of potassium levels is advised due to the risk of hyperkalemia. It may be used together with SGLT2 inhibitors.

12. Retinopathy, Neuropathy, and Foot Care

Diabetic Retinopathy

Recommendations

12.1 Optimize glycemic control to reduce the risk or slow the progression of diabetic retinopathy. A

12.2 Optimize blood pressure and serum lipid control to reduce the risk or slow the progression of diabetic retinopathy. A

Screening

Recommendations

12.4 Patients with type 2 diabetes should have an initial dilated and comprehensive eye examination by an ophthalmologist or optometrist at the time of the diabetes diagnosis. B

12.5 If there is no evidence of retinopathy for one or more annual eye exams and glycemia is well controlled, then screening every 1–2 years may be considered. If any level of diabetic retinopathy is present, subsequent dilated retinal examinations should be repeated at least annually by an ophthalmologist or optometrist. If retinopathy is progressing or sight-threatening, then examinations will be required more frequently. B

12.6 Programs that use retinal photography (with remote reading or use of a validated assessment tool) to improve access to diabetic retinopathy screening can be appropriate screening strategies for diabetic retinopathy. Such programs need to provide pathways for timely referral for a comprehensive eye examination when indicated. B

Treatment

Recommendations

12.9 Promptly refer patients with any level of diabetic macular edema, moderate or worse nonproliferative diabetic retinopathy (a precursor of proliferative diabetic retinopathy), or any proliferative diabetic retinopathy to an ophthalmologist who is knowledgeable and experienced in the management of diabetic retinopathy. A

12.14 The presence of retinopathy is not a contraindication to aspirin therapy for cardioprotection, as aspirin does not increase the risk of retinal hemorrhage. A

For more information about treatment of proliferative diabetic retinopathy, see “12. Retinopathy, Neuropathy, and Foot Care” in the complete 2022 Standards of Care.

Neuropathy

Screening

Recommendations

12.15 All patients should be assessed for diabetic peripheral neuropathy starting at diagnosis of type 2 diabetes and 5 years after the diagnosis of type 1 diabetes and at least annually thereafter. B

12.16 Assessment for distal symmetric polyneuropathy should include a careful history and assessment of either temperature or pinprick sensation (small-fiber function) and vibration sensation using a 128-Hz tuning fork (for large-fiber function). All patients should have annual 10-g monofilament testing to identify feet at risk for ulceration and amputation. B

12.17 Symptoms and signs of autonomic neuropathy should be assessed in patients with microvascular complications. E

Treatment

Recommendations

12.18 Optimize glucose control to prevent or delay the development of neuropathy in patients with type 1 diabetes A and to slow the progression of neuropathy in patients with type 2 diabetes. B

12.20 Pregabalin, duloxetine, or gabapentin are recommended as initial pharmacologic treatments for neuropathic pain in diabetes. A

Foot Care

Recommendations

12.21 Perform a comprehensive foot evaluation at least annually to identify risk factors for ulcers and amputations. B

12.22 Patients with evidence of sensory loss or prior ulceration or amputation should have their feet inspected at every visit. B

12.23 Obtain a prior history of ulceration, amputation, Charcot foot, angioplasty or vascular surgery, cigarette smoking, retinopathy, and renal disease and assess current symptoms of neuropathy (pain, burning, numbness) and vascular disease (leg fatigue, claudication). B

12.24 The examination should include inspection of the skin, assessment of foot deformities, neurological assessment (10-g monofilament testing with at least one other assessment: pinprick, temperature, vibration), and vascular assessment, including pulses in the legs and feet. B

12.25 Patients with symptoms of claudication or decreased or absent pedal pulses should be referred for ankle-brachial index and for further vascular assessment as appropriate. C

12.26 A multidisciplinary approach is recommended for individuals with foot ulcers and high-risk feet (e.g., dialysis patients and those with Charcot foot or prior ulcers or amputation). B

12.27 Refer patients who smoke or who have histories of prior lower-extremity complications, loss of protective sensation, structural abnormalities, or PAD to foot care specialists for ongoing preventive care and lifelong surveillance. C

12.28 Provide general preventive foot self-care education to all patients with diabetes. B

12.29 The use of specialized therapeutic footwear is recommended for high-risk patients with diabetes, including those with severe neuropathy, foot deformities, ulcers, callous formation, poor peripheral circulation, or history of amputation. B

See “12. Retinopathy, Neuropathy, and Foot Care” in the complete 2022 Standards of Care for specifics regarding comprehensive foot exams.

13. Older Adults

Recommendations

13.1 Consider the assessment of medical, psychological, functional (self-management abilities), and social domains in older adults to provide a framework to determine targets and therapeutic approaches for diabetes management. B

13.2 Screen for geriatric syndromes (i.e., polypharmacy, cognitive impairment, depression, urinary incontinence, falls, and persistent pain and frailty) in older adults, as they may affect diabetes self-management and diminish quality of life. B

Over one-fourth of people >65 years of age have diabetes, and one-half of older adults have prediabetes. Older adults with diabetes have higher rates of premature death, functional disability, accelerated muscle loss, and coexisting illnesses, such as hypertension, coronary heart disease, and stroke than those without diabetes. Screening for diabetes complications in older adults should be individualized and periodically revisited, as the results of screening tests may impact targets and therapeutic approaches.

Neurocognitive Function

Recommendation

13.3 Screening for early detection of mild cognitive impairment or dementia should be performed for adults 65 years of age or older at the initial visit and annually as appropriate. B