Abstract

Objective:

To determine the incidence of malocclusion in a 5-year follow-up of school children and verify the hypothesis that individuals with previous malocclusion are more prone to maintain the same characteristics in the transition from primary to mixed dentition.

Materials and Methods:

School children, ages 8 to 11 years, participated. Inclusion criteria consisted of normal occlusion in primary dentition or subsequent malocclusions, anterior open bite and/or posterior crossbite and/or overjet measuring more than 3 mm, and that subjects had not submitted to orthodontic treatment and adenoidectomy. Data collection was based on evaluation of occlusion in school children in the actual stage of mixed dentition. Descriptive, Chi-square, and relative risk (RR) 95% confidence interval (CI) analyses were carried out.

Results:

The greatest incidence of malocclusion was found in children with malocclusion (94.1%) when compared with those without malocclusion (67.7%) (RR = 1.4 [1.2–1.6]; P < .001). Anterior open bite (RR = 3.1 [1.7–5.8]), posterior crossbite (RR = 7.5 [4.9–11.5]), and overjet greater than 3 mm (RR = 5.2 [3.4–8.0]) in the primary dentition are risk factors for malocclusion in early mixed dentition. Spontaneous correction of the anterior open bite was confirmed in 70.1% of cases. Posterior crossbite and overjet greater than 3 mm were persistent in 87.8% and 72.9% of children.

Conclusions:

Malocclusion incidence was high. Individuals with previous anterior open bite, greater overjet, and posterior crossbite had greater risk of having the same characteristics in the mixed dentition.

Keywords: Cohort studies, Malocclusion, Primary dentition, Mixed dentition

INTRODUCTION

Primary occlusion may improve or worsen as an individual moves from primary to mixed and permanent dentition.1,2 Longitudinal studies indicate that, in most patients, a diagnosis of malocclusion and fairly consistent prediction of the development of mixed and permanent dentitions can be based on several occlusal features of the primary dentition.3

Accordingly, the key clinical question is whether these changes persist into the mixed dentition and to what degree. The available literature suggests that some occlusal characteristics persist into the mixed dentition.4,5 Conversely, the anterior open bite can be self-correcting in some cases.4,5–7

A large number of studies have included among the etiologic factors identification of changes in the normality pattern. Prolonged duration of nonnutritive sucking might have consequences for the development of occlusion.7–20 Thus, studies are needed to clarify these assumptions, and new data from primary to mixed dentition are required for a full understanding of this biogenetic course.

This study aimed to estimate the incidence of malocclusion in the mixed dentition among groups with and without previous malocclusion in primary dentition during a follow-up period of up to 5 years, and to confirm the presumption that individuals with previous malocclusion are more prone to retain the same characteristics in the mixed dentition.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

A longitudinal study was carried out to verify the incidence of malocclusion and the occurrence of self-correction of malocclusion during a 5-year follow-up period from May 2004 to May 2009. Two hundred forty-one school children were contacted. Two hundred twelve children, aged 8 to 11 years, were randomly selected from a representative sample to participate.26 Exclusion criteria were as follows: children with health problems, with previous orthodontic treatment, with adenoidectomy and any primary tooth problem affecting the integrity of the mesiodistal diameter in relation to dental caries. All children had the four upper and lower incisors and the four first permanent molars fully erupted, and congenitally missing or supernumerary primary or permanent teeth were absent.

Children were tracked through a questionnaire, thereby allowing participants to be located in current schools, and by means of telephone numbers and correspondence. The rights of individuals were protected, and informed consent and assent were obtained in accordance with the Human Research Ethics Committee of the Federal University of Minas Gerais.

Economic Status Evaluation

Economic classification was based on possession of the items by surveyed families and the level of education of the head of the household, according to Brazilian Association of Research Companies–ABEP criteria.21

Dental Arch Evaluation

All children underwent a clinical examination by a unique previously calibrated orthodontist blinded (kappa values ranging from 0.82 to 1.00 for anterior open bite, overbite, posterior crossbite and overjet). Evaluations included overjet and overbite measurements, classification of primary canines and second molars, first permanent molar relationships, and the presence or absence of malocclusions in centric occlusion.

Measurements were made directly using a buccal mirror, a tongue blade, and a millimeter probe to record the amount of overjet and overbite.22,23 Criteria for evaluating primary canines and second molars and first permanent molars relationships in Class I, Class II, or Class III, as well as posterior and anterior crossbite or open bite, were based on previously described methods.22,23 Anterior dental crowding was measured directly to the patient's mouth using a millimeter probe.32 All biosafety precepts were followed.

Eligibility criteria for normal occlusion in the mixed dentition were positive overjet and overbite from 1 to 3 mm, the primary canine relationship in normal occlusion (Class I), a distal terminal plane of primary second molars in the mesial step or vertical plane, first permanent molars in a straight or Class I relationship, anterior dental crowding up to 2 mm, and absence of any malocclusions.23,24 Children with malocclusion had at least one of the following alterations: anterior or posterior open bite and/or crossbite, overjet and/or overbite greater than 3 mm or less than 1 mm, primary canines or first permanent molars in Class II or III relationships, distal terminal plane of primary second molars in the distal step, and upper and/or lower anterior dental crowding greater than 2 mm.24 No discrimination was made between unilateral and bilateral for any type of malocclusion.

Assessment of Nonnutritive Sucking Habits

All information regarding the history and duration of existing pacifier-sucking and digit-sucking habits came from the questionnaire answered by parents or guardians and applied by the examiner in a previous study (in 2004) at the school.18 Participating children were categorized into groups for analysis of results: those who had never used a pacifier and those who used one up to the age of 2 years, 4 years, 6 years, and older than 6 years. The probability of self-correction of the malocclusion was evaluated by considering the first examination and the 5-year follow-up.

Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) for Windows, version 17.0 (SPSS Inc, Chicago, Ill). Bivariate analysis was the initial analytic strategy (Pearson's Chi-square test and relative risk, 95% CI). These tests evaluated risk factors between main variables in the transition from primary to mixed dentition. The level of significance was set at α = .05.

RESULTS

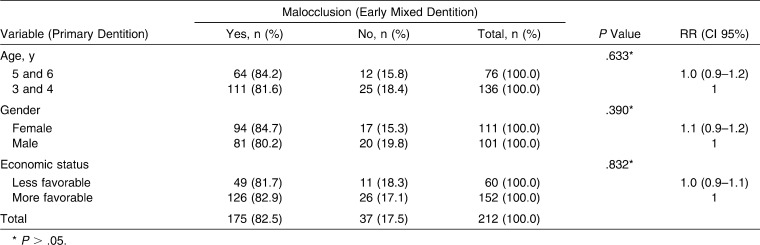

A total of 241 schoolchildren from 20 schools in Juiz de Fora, Brazil, were enrolled in the study. The response rate was 80.3% (92.6% in the malocclusion group and 68% in the nonmalocclusion group). The final sample was composed of 212 children (119 with malocclusion and 93 without malocclusion). It was verified, however, that nonagreed participants presented the same characteristics as those in the sample (ie, dropouts occurred at random). No statistically significant differences were observed with regard to the following confounding variables for dental malocclusion in the primary dentition and development of malocclusion in the mixed dentition: gender (P = .390), age (P = .633), and economic status (P = .832) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Univariate Analysis of Relative Risk Between Confounding Variables in the Primary Dentition and Malocclusion in the Early Mixed Dentition

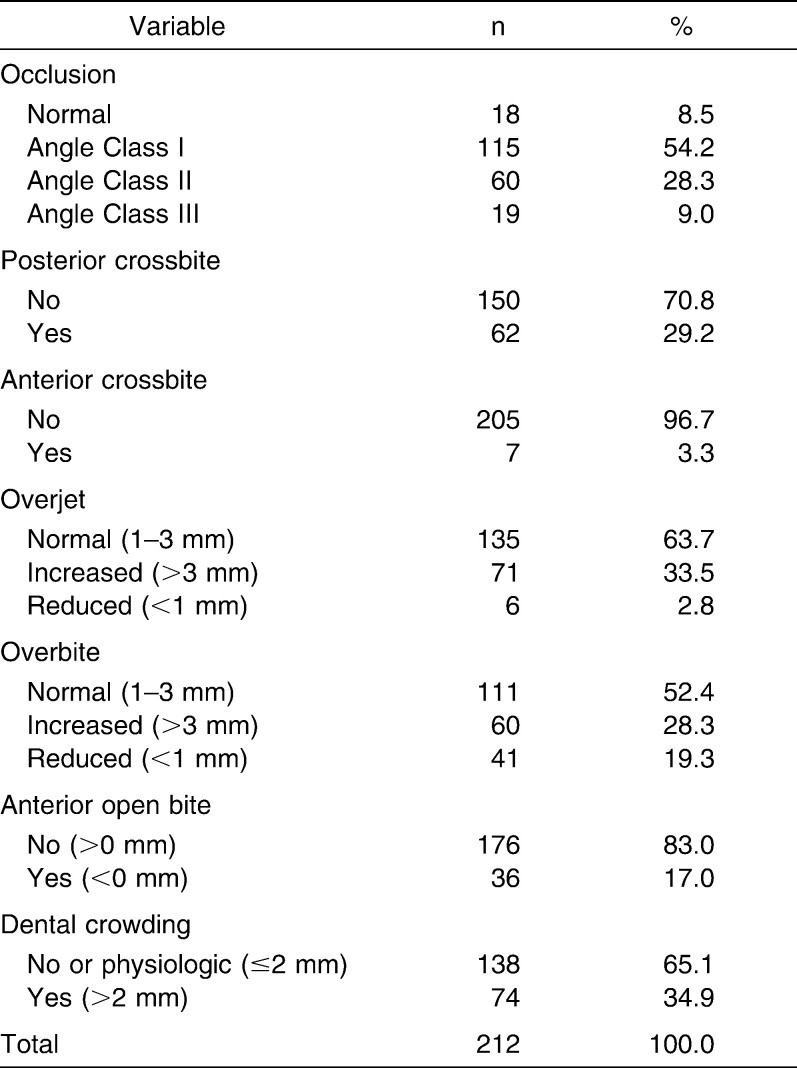

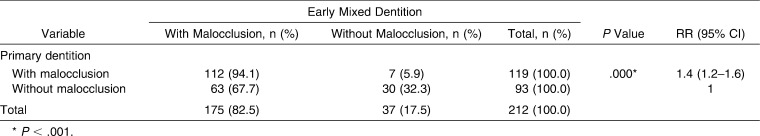

The sample comprised 111(52.4%) girls. Children were 7 (4.3%), 8 (27.8%), 9 (52.8%), and 10 (15.1%) years old. Categorized occlusal variables are displayed in Table 2. Confounding variables of gender, age, and economic status in the primary dentition were not considered risk factors for developing malocclusion in early mixed dentition (P > .05). The incidence of malocclusion in the early mixed dentition was 94.1% for the group with previous malocclusion and 67.7% for the group with no previous malocclusion. When normal occlusion frequency was evaluated, only 17.5% of the children retained such classification. Otherwise, the likelihood of schoolchildren with malocclusion rose from 56.1% to 82.5% between primary and early mixed dentition. Participants who had anterior malocclusion in the primary dentition had a 1.4 times greater risk of having malocclusion in early mixed dentition than participants without anterior malocclusion (RR [95% CI] = 1.4 [1.2–1.6]) (P < .001) (Table 3).

Table 2.

Sample Distribution in Relation to Occlusal Variables in Early Mixed Dentition

Table 3.

Univariate Analysis of Children With and Without Malocclusion Between Primary and Early Mixed Dentitions

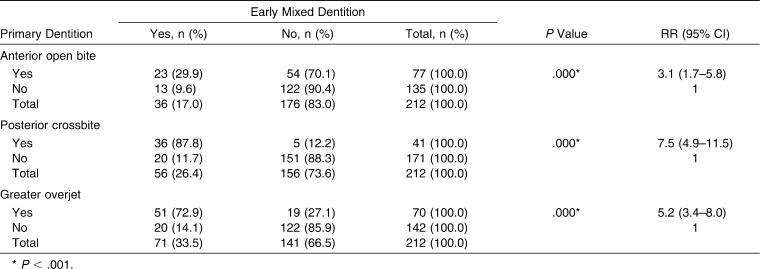

The prevalence of malocclusion in the primary and early mixed dentition was 36.3% and 17% for anterior open bite (Table 4), 19.3% and 26.4% for posterior crossbite (Table 4), and 33% and 33.5% for greater overjet (Table 4), respectively.

Table 4.

Univariate Analysis of Anterior Open Bite, Posterior Crossbite, and Greater Overjet Between Primary and Early Mixed Dentitions

In univariate analysis, a statistically significant association was found between primary and mixed dentitions for anterior open bite, posterior crossbite, and greater overjet (P < .001). Children who had anterior open bite in primary dentition had a 3.1 times greater risk (RR [95% CI] = 3.1 [1.7–5.8]) of presenting this malocclusion in mixed dentition than did children without anterior open bite in the primary dentition. Furthermore, children with previous anterior open bite showed 70.1% of self-correcting in the early mixed dentition (Table 4).

Conversely, children who had posterior crossbite in the primary dentition had a 7.5 times greater risk (RR [95% CI] = 7.5 [4.9–11.5]) of retaining this malocclusion in early mixed dentition. Crossbite was persistent in 87.8% of the children, with new cases occurring in 20 children (35.7%; Table 4). Likewise, children with overjet greater than 3 mm in primary dentition had a 5.2 times greater risk of retaining this malocclusion in early mixed dentition (RR [95% CI] = 5.2 [3.4–8.0]). According to this overjet, more than 3 mm was persistent in 72.9% of the children; moreover, new cases appeared in 20 participants (28.2%; Table 4).

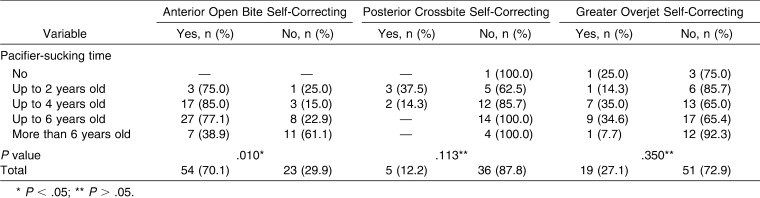

It was further confirmed that pacifier-sucking time played a significant role in spontaneous correction of the anterior open bite (70.1%; P < .05), more adversely in posterior crossbite (12.2%) and greater in overjet (27.1%; P > .05; Table 5).

Table 5.

Univariate Analysis of Malocclusions Self-Correcting According to Pacifier-Sucking Time

DISCUSSION

Although data collection had been thoroughly planned, we confirmed a 19.7% dropout rate. Dropouts occurred at random and produced no significant effect on the results. Dropouts presented similar characteristics to those in the sample, with no statistically significant differences with regard to confounding variables for malocclusion (gender, age, and economic status). Thus, the final sample may be considered a representative sample of schoolchildren from 7 to 10 years of age in Juiz de Fora, Brazil, and the results could be generalized for the entire population.

The study design makes the occurrence of recall bias unlikely because information used was collected during or shortly after exposure, leading to short recall periods. Observation bias is unlikely to have occurred because the observer was unaware of the children's exposure status when conducting the oral examination. Moreover, the accuracy of the examinations was greater in the clinical context owing to the fact that natural and artificial lights were used and a dental chair was available.

We confirmed the hypothesis that individuals having anterior malocclusion in the primary dentition presented greater risks of having malocclusion in the mixed dentition than those without anterior malocclusion.

The general proportion rate for malocclusion (82.5%) in the mixed dentition was significant to the point of being a public health problem. The risk is notable, and its reduction would be of value for maintaining more acceptable social and financial support levels. In our investigation, the prevalence of anterior open bite in the mixed dentition was similar to previous data.4,7 A survey of the literature provided evidence confirming this hypothesis with regard to the etiologic factors of malocclusion. The causes of malocclusion are complex and are influenced by hereditary and environmental factors. Only 5% of cases arise from specific known causes.24

The effect of nonnutritive sucking habits on the development of occlusion has been under investigation for several decades.5,7,8,11,14,18,20 The main question arising from these studies is whether such conditions disappear once risk factors for malocclusion have been identified and removed. The limited quantity of data in the literature show that anterior open bite tends to disappear when the habit is abandoned,4,5,7 but the same does not occur in the case of posterior crossbite4,5,8,25–27 and Class II malocclusion with increased overjet.4,11,28–32

In most patients in this study (70.1%), it was observed that anterior open bite tends to be self-correcting (n = 54) in the transition from primary to mixed dentition. In light of our findings, it appears advisable to recommend that pacifier-sucking habits be abandoned before the age of 6 years (ie, before eruption of the upper permanent incisors) to facilitate spontaneous correction of the anterior open bite in most children. Other investigators have presented similar data for this assumption.4,5–7

According to univariate analysis, children with posterior crossbite and greater overjet in the primary dentition had greater risk of having these malocclusions in the early mixed dentition, respectively, when compared with individuals without these anterior malocclusions. It was further observed that the prevalence of posterior crossbite increased in the transition from primary to mixed dentition. In fact, greater overjet remained remarkably stable. Moreover, the occurrence of 20 new cases of posterior crossbite may be explained by ectopic eruption of permanent first molars, dental changes in the position of the primary canines, and the appearance of unilateral posterior crossbite.

To intercept the development of crossbite and excessive overjet in mixed dentition, the developing occlusion should be observed in the primary dentition in children with prolonged digit or pacifier habits.8,10,12,13,15,18–20 Vertical, sagittal, and transverse occlusal relationships should be evaluated at 2 or 3 years of age, particularly in children with nonnutritive sucking habits.7,8,10,12,13,15,18–20 If interfering contacts of the primary canines are noted, or if a negative overbite or an excessive overjet is present, parents should be instructed to reduce pacifier- or finger-sucking time and to seek appropriate treatment, if required.7,13,15,18–20 Adverse dental effects of nonnutritive sucking habits may occur after the age of 2 years,8,18 3 years,7,12,15 or 4 years.13,19,20 Our results also discourage pacifier- and digit-sucking habits.

Primary

The transition period from primary to early mixed dentition is suitable for environmental and genetic factors to interfere with normal occlusal development. Defining the exact stage of intervention is of utmost importance for deciding upon and administering the appropriate orthodontic therapy. Starting treatment in the early mixed dentition could be advisable when lip or tongue functions are markedly altered. Psychological conditions related to esthetic problems and prevention of upper incision fractures after trauma can influence the decision in favor of an earlier intervention.11

CONCLUSIONS

Children with previous malocclusion presented greater risk of developing malocclusion in the early mixed dentition.

Individuals with posterior crossbite and greater overjet in the primary dentition are more prone to maintain the same characteristics in the early mixed dentition.

Anterior open bites tended to self-correct in the transition from primary to early mixed dentition if nonnutritive sucking habits were not/were no longer present.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the State of Minas Gerais Research Foundation (FAPEMIG) and the Brazilian Coordination of Higher Education (CAPES).

REFERENCES

- 1.Legovic M, Mady L. Longitudinal occlusal changes from primary to permanent dentition in children with normal primary occlusion. Angle Orthod. 1999;69:264–266. doi: 10.1043/0003-3219(1999)069<0264:LOCFPT>2.3.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Slaj M, Jezina M. A, Lauc T, Rajic-Mestrovic S, Miksic M. Longitudinal dental arch changes in the mixed dentition. Angle Orthod. 2003;73:509–514. doi: 10.1043/0003-3219(2003)073<0509:LDACIT>2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Keski-Nisula K, Keski-Nisula L, Mäkelã P, Mäki-Torkko T, Varrela J. Dentofacial features of children with distal occlusions, large overjets, and deepbites in the early mixed dentition. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2006;130:292–299. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2005.01.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bowden B. D. A longitudinal study of the effects of digit- and dummy-sucking. Am J Orthod. 1966;52:887–901. doi: 10.1016/0002-9416(66)90192-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Heimer M. V, Katz C. R. T, Rosenblatt A. Non-nutritive sucking habits, dental malocclusions, and facial morphology in Brazilian children: a longitudinal study. Eur J Orthod. 2008;30:580–585. doi: 10.1093/ejo/cjn035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Worms F. W, Meskin L. H, Isaacson R. J. Open-bite. Am J Orthod. 1971;59:589–595. doi: 10.1016/0002-9416(71)90005-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cozza P, Baccetti T, Franchi L, Mucedero M, Polimeni A. Sucking habits and facial hyperdivergency as risk factors for anterior open bite in the mixed dentition. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2005;128:517–519. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2005.04.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Warren J. J, Bishara S. E. Duration of nutritive and nonnutritive sucking behaviors and their effects on the dental arches in the primary dentition. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2002;121:347–356. doi: 10.1067/mod.2002.121445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Serra-Negra J. M, Pordeus I. A, Rocha-Jr J. F. Study of the relationship between infant methods, oral habits and malocclusion. Rev Odontol Univ São Paulo. 1997;11:79–86. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Katz C. R. T, Rosenblatt A, Gondim P. P. C. Nonnutritive sucking habits in Brazilian children: Effects on deciduous dentition and relationship with facial morphology. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2004;126:53–57. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2003.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Antonini A, Marinelli A, Baroni G, Franchi L, Defraia E. Class II malocclusion with maxillary protrusion from the deciduous through the mixed dentition: a longitudinal study. Angle Orthod. 2005;75:980–986. doi: 10.1043/0003-3219(2005)75[980:CIMWMP]2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Aznar T, Galán A. F, Marín I, Domínguez A. Dental arch diameters and relationships to oral habits. Angle Orthod. 2006;76:441–445. doi: 10.1043/0003-3219(2006)076[0441:DADART]2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bishara S. E, Warren J. J, Broffitt B, Levy S. M. Changes in the prevalence of nonnutritive sucking patterns in the first 8 years of life. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2006;130:31–36. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2004.11.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vázquez-Nava F, Quezada-Castillo J. A, Oviedo-Treviño S, Saldivar-González A. H, Sánchez-Nuncio H. R, Beltrán-Guzmán F. J, Vázquez-Rodriguez E. M, Vázquez-Rodriguez C. F. Association between allergic rhinitis, bottle feeding, non-nutritive sucking habits, and malocclusion in the primary dentition. Arch Dis Child. 2006;91:836–840. doi: 10.1136/adc.2005.088484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cozza P, Baccetti T, Franchi L, Mucedero M, Polimeni A. Transverse features of subjects with sucking habits and facial hyperdivergency in the mixed dentition. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2007;132:226–229. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2007.02.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Peres K. G, Barros A. J, Peres M. A, Victora C. G. Effects of breastfeeding and sucking habits on malocclusion in a birth cohort study. Rev Saúde Pública. 2007a;41:343–350. doi: 10.1590/s0034-89102007000300004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Peres K. G, Latorre M. R, Sheiham A, Peres M. A, Victora C. G, Barros F. C. Social and biological early life influences on the prevalence of open bite in Brazilian 6-year-olds. Int J Paediatr Dent. 2007b;17:41–49. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-263X.2006.00793.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Góis E. G. O, Ribeiro-Júnior H. C, Vale M. P. P, Paiva S. M, Serra-Negra J. M. C, Ramos-Jorge M. L, Pordeus I. A. Influence of nonnutritive sucking habits, breathing pattern and adenoid size on the development of malocclusion. Angle Orthod. 2008;78:647–654. doi: 10.2319/0003-3219(2008)078[0647:IONSHB]2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry (AAPD) Guideline on management of the developing dentition in pediatric dentistry. Pediatr Dent. 2009;31:196–208. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sexton S, Natale R. Risks and benefits of pacifiers. Am Fam Physician. 2009;79:681–685. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Abep-Assoiação Brasileira de Empresas de Pesquisa The economic status of Brazil. Available at: http://www.abep.org/novo/Content.aspx?ContentID=302 Accessed June 1, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Foster T. D, Hamilton M. C. Occlusion in the primary dentition: study of children at 2½ to 3 years of age. Br Dent J. 1969;126:76–79. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Moyers R. E. Handbook of Orthodontics 4th ed. Chicago, Ill: Year Book Medical; 1988. p. 577. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Proffit W. R. The etiology and development of orthodontic problems. In: Proffit W. R, Fields H. W Jr, Sarver D. M, editors. Contemporary Orthodontics 4th ed. St Louis, Mo: Mosby; 2007. pp. 130–161. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kutin G, Hawes R. R. Posterior cross-bites in the deciduous and mixed dentitions. Am J Orthod. 1969;56:491–504. doi: 10.1016/0002-9416(69)90210-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kurol J, Berglund L. Longitudinal study and cost-benefit analysis of the effect of early treatment of posterior cross-bites in the primary dentition. Eur J Orthod. 1992;14:173–179. doi: 10.1093/ejo/14.3.173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kloecke A, Nanda R. S, Kahl-Nieke B. Anterior open bite in the deciduous dentition: longitudinal follow-up and craniofacial growth considerations. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2002;122:353–358. doi: 10.1067/mod.2002.126898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Arya B. S, Savara B. S, Thomas D. R. Prediction of first molar occlusion. Am J Orthod. 1973;63:610–621. doi: 10.1016/0002-9416(73)90186-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bishara S. E, Hoppens B. J, Jakobsen J. R, Kohout F. J. Changes in the molar relationship between the deciduous and permanent dentitions: a longitudinal study. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 1988;93:19–28. doi: 10.1016/0889-5406(88)90189-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Baccetti T, Franchi L, McNamara J. A, Jr, Tollaro I. Early dentofacial features of Class II malocclusion: a longitudinal study from the deciduous through the mixed dentition. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 1997;111:502–509. doi: 10.1016/s0889-5406(97)70287-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Varrela J. Early developmental traits in Class II malocclusion. Acta Odontol Scand. 1998;56:375–377. doi: 10.1080/000163598428356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stahl F, Baccetti T, Franchi L, McNamara J. A., Jr Longitudinal growth changes in untreated subjects with Class II division 1 malocclusion. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2008;134:125–137. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2006.06.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]