Present-day emergency medical services (EMS) favor a “scoop and run” approach directed toward rapidly transporting patients to hospitals rather than delaying transport to optimize the scope and consistency of on-scene clinical care. This works for stroke, a disease where we traditionally rely on hospital as opposed to prehospital treatment, but not for the estimated 40,000 patients with status epilepticus.1

Descriptions of prehospital status epilepticus care depict a system challenged by misdiagnosis, delayed medication administration, and ill-defined transport protocols. Studies demonstrate nearly 50% of patients with status epilepticus have their seizures missed in the prehospital setting.2 Even when accurately diagnosed, >40% do not receive any prehospital benzodiazepine, and those who receive treatment are administered doses far below national guidelines.3 Patients who require EEG monitoring and specialized neurologic care are routinely transported to hospitals lacking these capabilities. Altogether, these gaps likely result in increased seizures, cost, disability, and potentially death. As specialists with responsibility for this neurologic emergency, neurologists can take the lead in building partnerships that close these gaps and advance prehospital systems of care.

Pathway to Improvement

Twenty years ago, we addressed similar challenges in delivering evidence-based treatment for patients with stroke. The Get With The Guidelines–Stroke Program was developed in 2003 as an inpatient registry and quality improvement program to address this gap. Today, >2,000 hospitals and 5 million patients have directly participated in the program, resulting in a doubling of the number of patients now receiving thrombolytic treatment.4

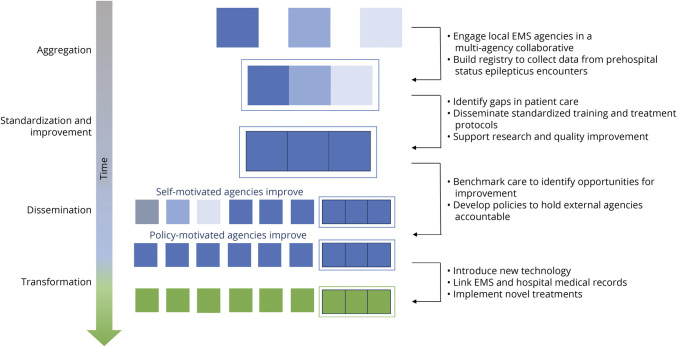

We can do the same for prehospital status epilepticus (Figure). Professional organizations can provide key leadership for developing a status epilepticus collaboration. Such program development could involve stakeholders such as epileptologists, neurohospitalists, the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration Office of EMS, emergency medicine clinicians, and paramedics who provide distinct expertise in the health system and care required for status epilepticus. The program could implement standardized prehospital protocols and training for prehospital providers to improve upon the current fractured educational infrastructure. The program would motivate consistent data collection and bolster efforts already underway through the National Emergency Medical Services Information System to use data to facilitate clinical research, motivate quality improvement, and hold EMS agencies externally accountable.

Figure. Model for Improving Prehospital Care.

Model for improving prehospital care in which there is collaborative development of a prehospital status epilepticus registry committed to evidence-based treatment protocols, high-quality training, standardized data collection, research, and quality improvement. This network would allow for benchmarking and motivate future policy to improve care outside the network, leading to transformation and improvement of prehospital care across all emergency medical service (EMS) agencies.

Novel technology might also be harnessed to improve outcomes. EEG devices that can be applied and interpreted in the field would inform on-scene diagnosis and transport decisions. More effective systems to link prehospital and hospital evaluation would increase awareness of how prehospital decisions influence patient outcomes and inform national EMS policy.

Seizing the Opportunity

We have a chance to improve brain health and the quality of prehospital care overall. Neurologists, EMS specialists, emergency medicine physicians, and the community of patients with epilepsy and advocates must take ownership of this space. Together, we comprise a neuroemergency community that can mitigate needless brain injury in the minutes following seizure onset. This community can voice the need for increased attention so that funding mechanisms, policy makers, and the health system at large put more resources behind terminating seizures and our prehospital status quo.

Acknowledgment

The authors thank Amy J. Markowitz, JD, for editorial assistance.

Appendix. Authors

Study Funding

The authors report no targeted funding.

Disclosure

E.L. Guterman receives funding from the National Institute of Neurologic Disorders and Stroke (1K23NS116128-01), National Institute on Aging (5R01AG056715), and American Academy of Neurology for investigator-initiated research. She previously received consulting fees from Marinus Pharmaceuticals, Inc. She currently serves as a consultant for REMO health and receives personal compensation from JAMA Neurology, which are unrelated to this work. D.H. Lowenstein receives funding from the National Institute of Neurologic Disorders and Stroke (U01NS088034), the Office of The Director, NIH (U54 OD020351), and the Human Epilepsy Project for investigator-initiated research. K.A. Sporer reports no disclosures relevant to the manuscript. Go to Neurology.org/N for full disclosures.

References

- 1.Betjemann JP, Josephson SA, Lowenstein DH, Burke JF. Trends in status epilepticus-related hospitalizations and mortality: redefined in US practice over time. JAMA Neurol. 2015;72(6):650-655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Semmlack S, Yeginsoy D, Spiegel R, et al. Emergency response to out-of-hospital status epilepticus: a 10-year observational cohort study. Neurology. 2017;89(4):376-384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Guterman EL, Sanford JK, Betjemann JP, et al. Prehospital midazolam use and outcomes among patients with out-of-hospital status epilepticus. Neurology. 2020;95(24):e3203-e3212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ormseth CH, Sheth KN, Saver JL, Fonarow GC, Schwamm LH. The American Heart Association's Get with the Guidelines (GWTG)–Stroke development and impact on stroke care. Stroke Vasc Neurol. 2017;2(2):94-105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]