Abstract

Deciphering factors modulating DNA repair in chromatin is of great interest since nucleosomal positioning influences mutation rates. H3K56 acetylation (Ac) is implicated in chromatin landscape regulation, impacting genomic stability. Yet, the effect of H3K56Ac on DNA base excision repair (BER) remains unclear. We determined whether H3K56Ac plays a role in regulating AP site incision by AP endonuclease 1 (APE1), an early step in BER. Our in vitro studies of acetylated, well-positioned nucleosome core particles (H3K56Ac-601-NCPs) demonstrate APE1 strand incision is enhanced compared with unacetylated WT-601-NCPs. The high-mobility group box 1 protein enhances APE1 activity in WT-601-NCPs, but this effect is not observed in H3K56Ac-601-NCPs. Therefore, our results suggest APE1 activity on NCPs can be modulated by H3K56Ac.

Keywords: AP endonuclease 1, base excision repair, histone H3 lysine 56 acetylation, nucleosome core particle, DNA damage

INTRODUCTION

Damage to DNA occurs continuously as a consequence of its inherent instability and propensity to undergo a myriad of spontaneous and agent-induced chemical modifications3. In mammalian cells, many of these genomic stressors give rise to the apurinic/apyrimidinic (AP) lesion in double stranded DNA, resulting in a steady-state level of 50,000-200,000 AP sites3–5. Unrepaired and persistent AP sites can have negative biological consequences as they disrupt replication and transcription, potentially leading to cytotoxic strand breaks and mutations6. Accumulation of mutations, and other forms of genomic instability, is associated with carcinogenesis, aging, and other neurological disorders7.

The human AP endonuclease 1 (APE1) protein consists of 318 residues (~37 kDa) including regions involved in both DNA repair processes and redox regulation8. In the context of DNA repair, APE1 is responsible for removing more than 95% of the steady-state level of AP lesions by incising the DNA backbone 5′ to the AP site sugar using Mg2+ as a cofactor9. APE1 functions in the base excision repair (BER) pathway following the activity of lesion-specific DNA glycosylases or spontaneous base loss. The incision product of APE1 following monofunctional glycosylase activity or through spontaneous base loss is a one-nucleotide gap characterized by a 3′-hydroxyl group and a 5′-deoxyribose phosphate (5′-dRP) group at the margins. The activity of APE1 is also required to remove 3′ blocking moieties after the action of bifunctional DNA glycosylases, which also cleave the DNA backbone. In all cases, the generated 3′-OH is subsequently utilized by a DNA polymerase that fills in the missing nucleotide(s). The integrity of DNA is restored after ligation of the DNA backbone by DNA ligase I or the DNA ligase III-XRCC1 complex.

APE1 is crucial for cell viability10. In fact, APE1-null mice display significant developmental problems and die at ~embryonic day 5.511. In humans, dysregulated activity of APE1 has been found in many solid tumors, and APE1 over-expression is associated with resistance to some traditional therapeutic treatments12. These findings, along with its redox function, involved in transcriptional regulation, have made APE1 an attractive candidate for the development of new therapeutic treatments; however, our understanding on how APE1 functions to remove AP sites is limited to kinetic and structural studies using short free DNA substrates13, 14. Recent reports provide some insight on the activity of APE1 in the context of the fundamental unit of chromatin, the nucleosome core particle (NCP). These studies documented reduced APE1 activity in the NCP in a site-specific manner15, 16. However, they did not provide the kinetic parameters necessary to better understand the potential mechanisms for this APE1 inhibition. Moreover, NCPs are subject to intrinsic and extrinsic regulation, and how these factors influence AP site removal has not been evaluated. Identifying these parameters is vital, given that AP sites are inherently unstable as they exist in an equilibrium between a closed-ring hemiacetal and an open-ring aldehyde17, that is prone to β-elimination reactions promoting DNA-protein crosslinks (DPCs)18. DPCs are not repaired efficiently and require alternative repair pathways such as nucleotide excision repair. Importantly, DPCs are likely to be converted into cytotoxic double strand breaks19. The alkali lability of AP sites is consequently influenced by the presence and proximity of histone lysine residues that can promote strand scission. Greenberg and colleagues have found AP sites to be almost two orders of magnitude more reactive in nucleosomes than in free DNA, where rotational orientation20 and proximity to other AP sites play a role in AP site propensity to crosslink18. Although these observations are important for the overall biological effect and cellular consequences of AP sites, unraveling the kinetic mechanism with natural AP sites may be challenging due to this crosslinking susceptibility. Consequently, to delineate the kinetic parameters of APE1 activity in NCPs, we have utilized tetrahydrofuran (THF), a stable analog of the AP site, as the substrate for APE1 in all of our in vitro assays.

NCP stability is influenced by histone posttranslational modifications (PTMs) and action of chromatin-associated factors, which are postulated to influence repair; however, it is still unknown if PTMs exert an effect on APE1 activity. In this study, we investigated the role of H3K56Ac on BER in vitro. It was previously shown that histone acetylation at H3K14 and H3K56 decreased DNA synthesis by DNA polymerase (Pol) β21. Although the lesions were outside the region of increased accessibility afforded by H3K56Ac1, 2, 22, 23, the negative correlation was unexpected, and it suggested that histone acetylation in vivo may serve alternative roles than those associated with increased nucleosome dynamics or that this regulation is limited to the structural location of the DNA lesion.

H3K56Ac is a unique histone PTM deposited behind the replication fork in newly synthesized H3 molecules. In the absence of DNA damage, SIRT6 can deacetylate this site when the cell enters G2 or later stages of the cell cycle24; however, when DNA damage is present, H3K56Ac levels persist and are believed to promote repair due to charge neutralization at the entry-exit region of the NCP25. Despite this apparent concept of increased accessibility potentially leading to increased repair, the levels of H3K56Ac in response to DNA damage are still debatable with conflicting findings26, 27. In order to isolate the effects of histone site-specific acetylation on the kinetic parameters of APE1 activity, we generated homogeneously acetylated NCPs at H3K56 and H3K14. Our results with these NCPs as substrates indicate that APE1 activity is significantly hindered in the NCP. Site-specific histone acetylation that promotes nucleosome dynamics, such as H3K56Ac, enhances APE1 activity. However, acetylation at the alternate site H3K14Ac does not have an effect on APE1 activity, suggesting the structural location of histone acetylation is important in mediating repair. HMGB1 can additionally enhance APE1 activity in the absence of H3K56Ac. Our results have uncovered the complexity of an intrinsic and extrinsic regulation of APE1 activity and suggest this regulation is imbedded in the structural position of histone acetylation relative to the lesion and the action of chromatin associated factors (i.e., HMGB1) in BER that had not been previously appreciated in the context of chromatin.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Preparation of DNA substrates containing tetrahydrofuran (THF).

The 147-bp 601 nucleosome positioning DNA sequence28 was modified to introduce a single THF group 11 bp from the 5′ end of the J chain, which is equivalent to 64 nt from the dyad, and designated as THF (+64). The forward primer containing the THF: 5′-FAM-CAC AGG ATG TTHFGA TAT CTG GCC TGG AGA CTA G-3′, the reverse primer: 5′-TGG AGA ATC CCG GTG CCG AGG CCG CTC AAT TG-3′, and the plasmid: pGEM-3Z/601 were used to generate the substrate via the polymerase chain reaction (PCR) listed in Table S1. Following a PCR reaction, the PCR product was concentrated using a standard ethanol precipitation protocol and purified from a 1.2% agarose gel using a DNA agarose gel extraction kit (Qiagen). For the substrates containing the 5S nucleosomal positioning sequence21, the 162-bp DNA substrate was generated by first ligating the damaged strand containing a single THF group and 5′-FAM, using a splinter complementary DNA upstream and downstream of the lesion. This ligation reaction contained 110 units of E. coli DNA ligase and 1x ligation buffer provided by the manufacturer (New England Biolabs). The ligated product and the undamaged complementary strand (162-mer) were PAGE purified and subsequently annealed by heating to 95°C for 10 min and slow cooling in buffer containing 30 mM Tris, pH 7.5 and 100 mM potassium acetate. The dsDNA substrate is listed in Table S1.

Nucleosome core particle reconstitution.

Nucleosome core particles (NCPs) were reconstituted by salt gradient dialysis using recombinant octamer from Xenopus laevis containing all unmodified “wild type” (WT) core histones or histone H3 acetylated at Lys14 or Lys56. All WT core histones were each individually expressed in E. coli (BL21) as previously described29. After isolation, the histones were subjected to dialysis in a buffer containing 5 mM 2-mercaptoethanol and 0.2 mM PMSF. They were then lyophilized until dry, and the histone octamer was prepared as described by Luger et al.30 Briefly, the concentration of each unfolded histone protein was determined by A280 nm and equimolar amounts of all four histones were mixed and dialyzed three times in refolding buffer (2 M NaCl, 20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 1 mM Na-EDTA, 5 mM 2-mercaptoethanol) at 4°C. Generation of homogeneously acetylated histone octamers containing either H3K14Ac or H3K56Ac was performed as described previously30 and in Neumann et al.22 BL21 E. coli were co-transformed with a plasmid (pAcKRS-3) containing the ORF of the gene directing the synthesis of acetyl-lysine-tRNA synthetase from M. barkeri (Mb), which directs insertion of aceyl-lysine residues at amber codons, and plasmid (pCDF PyIT-1) containing the MbtRNACUA gene and an N-terminally hexahistadine-tagged histone H3, encoding an amber codon at position 14 or 56, downstream of a T7 promoter (both recombinant modified histone octamers were a generous gift of Dr. Michael Smerdon, Washington State University). Purification and assembly of these site-specifically modified histone octamers has been described previously21. Site-specific acetylated or WT histone octamers were then mixed with DNA containing a single THF group in a 1.2:1 molar ratio via salt gradient dialysis to reconstitute NCPs as described31, 32. Reconstitution efficiency was assessed in a 6% native/nondenaturing polyacrylamide gel, where reconstitutions containing ≤ 5% free DNA were used for biochemical assays.

Purification of WT and H133Y mouse SIRT6 proteins.

Bacterial expression plasmids for mouse WT and H133Y were obtained from Addgene (plasmid IDs: 20277, pET28a-Hix6-SIRT6 and 20279, pET28a-Hix6-SIRT6-H133Y). Competent cells BL21-codon plus (DE3) from Agilent (230245) were used to express WT and H133Y SIRT6 following a standard heat-pulse transformation protocol at 42°C with a 23s sonic pulse. Terrific broth containing the appropriate antibiotics (chloramphenicol and kanamycin) was inoculated for an overnight culture and then maintained at 37°C for 1.5 h with vigorous shaking. After this time, the temperature was lowered to 16°C until the OD600 nm reached 0.7, at which time cells were induced with IPTG (0.5 mM) overnight reaching an OD600 nm of 2.1, and then cells were harvested. The cell pellet from 1 l culture was resuspended with 75 ml of low salt lysis buffer (50 mM Tris-Cl, pH 8, 500 mM NaCl, 0.5 mM TCEP and freshly added protease inhibitors (1X): Leupeptin (1 μg/ml), protinin (1 μg/ml), pefabloc (100 μg/ml), and PepstinA (1 μg/ml). Cells were lysed via sonication in a dry ice-ethanol bath at 40% power for 5 min, taking 30 s breaks. Lysed cells were centrifuged using the Beckman Coulter Optima L-100 XP Ultracentrifuge with rotor Ti-45 (41,000 rpm) at 4°C for 1 h. The supernatant fraction was passed through a pre-equilibrated HisTrap HP column: washed with 2 column volumes of 50 mM EDTA, washed with 3 column volumes of dH2O, charged with 2 column volumes of 100 mM NiCl2, washed again with dH2O (3 column volumes), followed by addition of 3 column volumes of low salt lysis buffer with protease inhibitors and 5 mM imidazole). This was followed by a wash with high salt buffer (50 mM Tris-Cl, pH 8, 1M NaCl, 0.5 mM TCEP and freshly added protease inhibitors previously listed. The column was then washed again with low salt lysis buffer containing protease inhibitors and 5 mM imidazole. Elution was performed with 50 ml of elution buffer (50 mM Tris-Cl, pH 8, 250 mM NaCl, 0.5 mM TCEP, protease inhibitors, and 400 mM imidazole). The eluted sample was diluted 5X with a buffer containing 50 mM Tris-Cl, pH 8, 0.5 mM TCEP and protease inhibitors to allow the sample to be at the lower salt concentration of 50 mM NaCl. Then, it was loaded onto a pre-equilibrated Hi-trap SP sepharose column with low-salt buffer (50 mM Tris-Cl, pH 8, 50 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, pH 8, and 0.5 mM TCEP). Elution from this column was gradually achieved with a high salt buffer containing 50 mM Tris-Cl, pH8, 1M NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, pH 8, and 0.5 mM TCEP. The final step in the purification was performed using an AKTA HPLC and Superdex 200 column with an elution buffer of 50 mM Tris-Cl, pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, and 1mM EDTA. Samples along the purification steps were fractionated in a 12% Bis-tris SDS gel and Coomassie blue stained with SimplyBlue SafeStain.

Deacetylation activity assay of WT and H133Y mouse SIRT6 purified recombinant proteins.

To determine the deacetylation activity of both purified SIRT6 proteins, a fluorometric SIRT6 activity assay (Abcam) was used following the manufacturer’s recommendations. In this assay, a fluorophore and quencher are coupled at opposite N- and C-termini of a substrate peptide containing an acetylated lysine. Following the deacetylation activity of SIRT6, the substrate becomes a substrate peptide for a peptidase (which is added simultaneously) that cuts the peptide, and thus allowing the fluorophore to emit fluorescence. Fluorescence intensity was measured at extinction/emission wavelengths of A480/530 nm, respectively.

Western Blotting.

SIRT6 deacetylation activity was measured using H3K56Ac-NCP-THF (+64) as a deacetylation substrate. This damaged deacetylation substrate (630 nM) was incubated in a buffer containing 5 mM NAD+, 50 mM HEPES, pH 8, 100 mM KCl, 5 mM MgCl2, and 1 mg/ml BSA for 10 and 30 min at 37°C. Proteins were then fractionated in a 12% Bis-tris SDS gel and transferred onto a nitrocellulose membrane (Life Techonology). The membrane was then incubated in 5% nonfat milk in TBST (10 mM Tris, pH 8.0, 150 mM NaCl, 0.5% Tween 20) for 1 h, followed by incubation with primary antibody anti-H3K56 Ac (1:1000) from Abcam (ab76307). Goat anti-rabbit IgG conjugated to horseradish peroxidase (Bio-Rad) was used as secondary antibody, and immobilized horseradish peroxidase activity was detected by enhanced chemiluminescence (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Acetylation of the recombinant octamers was performed with the same antibody for H3K56Ac (1:5000) and for H3K14Ac (Active Motif 39697; 1:1000). Incubation with primary antibodies was performed either for 1 h at room temperature or overnight at 4°C, respectively. Membranes were subsequently washed three times for 10 min and incubated with the appropriate dilution of horseradish peroxidase-conjugated anti-rabbit antibodies for 2 h at room temperature. Blots were then washed with Tris buffered saline and Tween 20 solution (TBST) three times (5 min each) and developed with the ECL system (Amersham Biosciences) according to the manufacturer’s protocols either using Amersham hyperfilm ECL or Amersham Imager 600 system (as indicated in the figure legends).

Steady-state and single-turnover assays.

DNA/NCP substrate (amount indicated in each plot) reaction mixtures containing 50 mM HEPES, pH 8, 100 mM KCl, 5 mM MgCl2, and 0.01 mg/ml BSA were incubated at 37°C for 5 min prior to the addition of APE1 to initiate the reaction. Time points were taken (6 μl) and quenched with an equal volume of 100 mM EDTA, pH 8. This was followed by a phenol:chloroform:isoamyl alcohol extraction to isolate the DNA. Each sample was then mixed 1:1 (vol:vol) with deionized formamide, boiled, and fractionated in a 20% polyacrylamide 7 M urea denaturing gel. The ratio of DNA:enzyme is shown as an insert within the plots, indicating if they are steady-state or single-turnover assays. The summary bar graphs for the calculated apparent rate constants performed under steady-state conditions was as follows:

Kss = v0 / [Etotal], where v0 is the initial velocity and Etotal is the total APE1 concentration as calculated from Bradford assay. For steady-state reactions where data were fitted to a single exponential, the rate constant was calculated as reported previously 33

| Equation 1 |

The initial rate of the reaction (v0) was determined by taking the derivative of equation 1 (dY/dt) as t approaches 0. The rate constant, (v0/[Etotal]), was then calculated as follows

| Equation 2 |

For single turnover conditions, kobs was obtained directly from the fit of the data to a single exponential equation (Equation 1).

RESULTS

To better understand H3K56Ac regulation of BER, we conducted an assessment of the acetylation effect on APE1 activity within NCP substrates. The design of our in vitro substrates considers proximity of the AP site DNA lesion to the histone acetylation site. The experimental design includes analysis of the presence of the chromatin associated protein high mobility group box 1 (HMGB1), found to regulate chromatin structure34, as well as APE1 activity35.

Histone site-specific acetylation at H3K56 enhances APE1 activity.

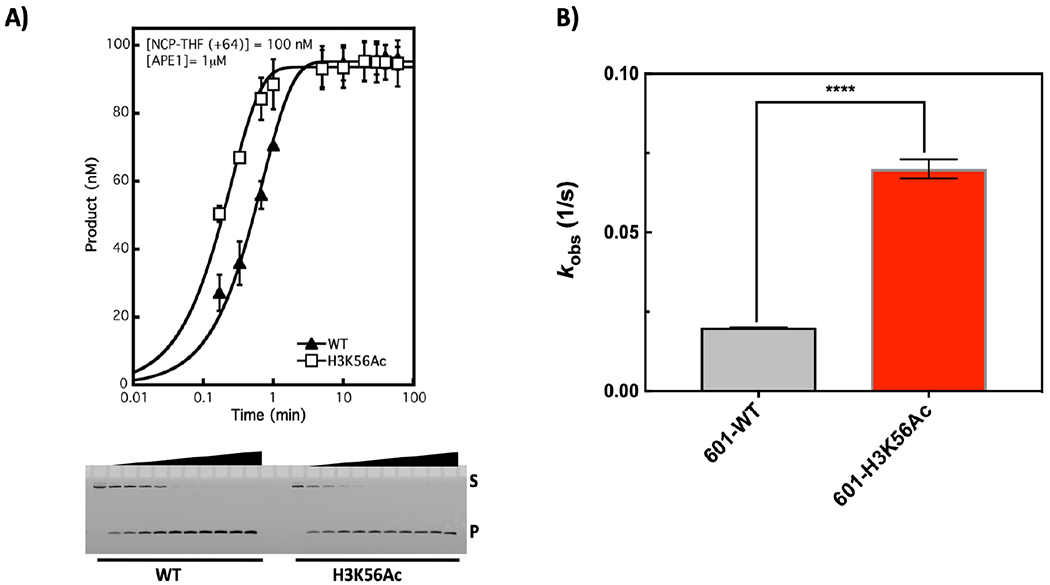

The in vivo results described by others suggest higher levels of H3K56Ac as a result of SIRT6 absence contribute to genomic instability36, 37, possibly by regulating the chromatin landscape and accessibility to DNA lesions. Because there are multiple in vivo parameters that could be at play, we chose to investigate the effect of H3K56Ac on APE1 strand incision activity. Nucleosome core particles (NCPs) were designed containing a strategically located AP site within the well-positioned 601 DNA (Table S1). The NCP reconstitution efficiency was verified for this substrate using native/non-denaturing PAGE. Representative results are shown in Figure S1A, demonstrating that NCP integrity was achieved independent of the presence of the AP site DNA lesion and histone acetylation status (confirmed by western blotting in Figure S1B). As shown in Figure 1, the AP site is in proximity to the H3K56Ac near the DNA ends, where DNA unwrapping has been shown to be enhanced by acetylation. The substrate nomenclature has been described previously21, 32, where the number in parenthesis indicates the number of nucleotides away from the dyad toward the 5′ end (designated as positive) or toward the 3′ end (negative). Because this lesion is near the end, it does not adopt a definitive rotational orientation, as the DNA is more loosely associated with the histones38. However, APE1 activity was assessed previously in NCPs containing the 601-DNA positioning sequence, where rotational orientation of the lesion was suggested to play a role in enzyme inhibition15. Yet, quantitative kinetic parameters of this inhibition, particularly as a function of histone acetylation, were not determined. We first obtained single-turnover kinetic parameters, where the APE1 molar concentration was in excess over the substrate. Under these conditions, the results shown in Figure 2A indicate a significant enhancement of APE1 activity conferred by H3K56 acetylation, where the rate obtained from a single exponential equation is plotted in Figure 2B (p-value <0.0001, two-tailed, unpaired t-test). In contrast, the 5S-NCPs exhibited biphasic kinetics as a result of more heterogeneity in the translational position of the histone octamer (Figure S3A). The fast phase (~ 0.2 ± 0.09 1/s) was similar in WT- and H3K56Ac-5S-NCPs. A larger population of WT-5S-NCPs (88%) was more readily incised compared to the H3K56Ac-5S-NCPs (60%) (Figure S3B). This suggests H3K56Ac enhances the heterogeneity of the nucleosomal substrate due to enhanced nucleosome dynamics. In this case, the larger 5S-H3K56Ac-NCP population was incised by APE1 at a slower rate (~10-fold) than the 601-NCPs.

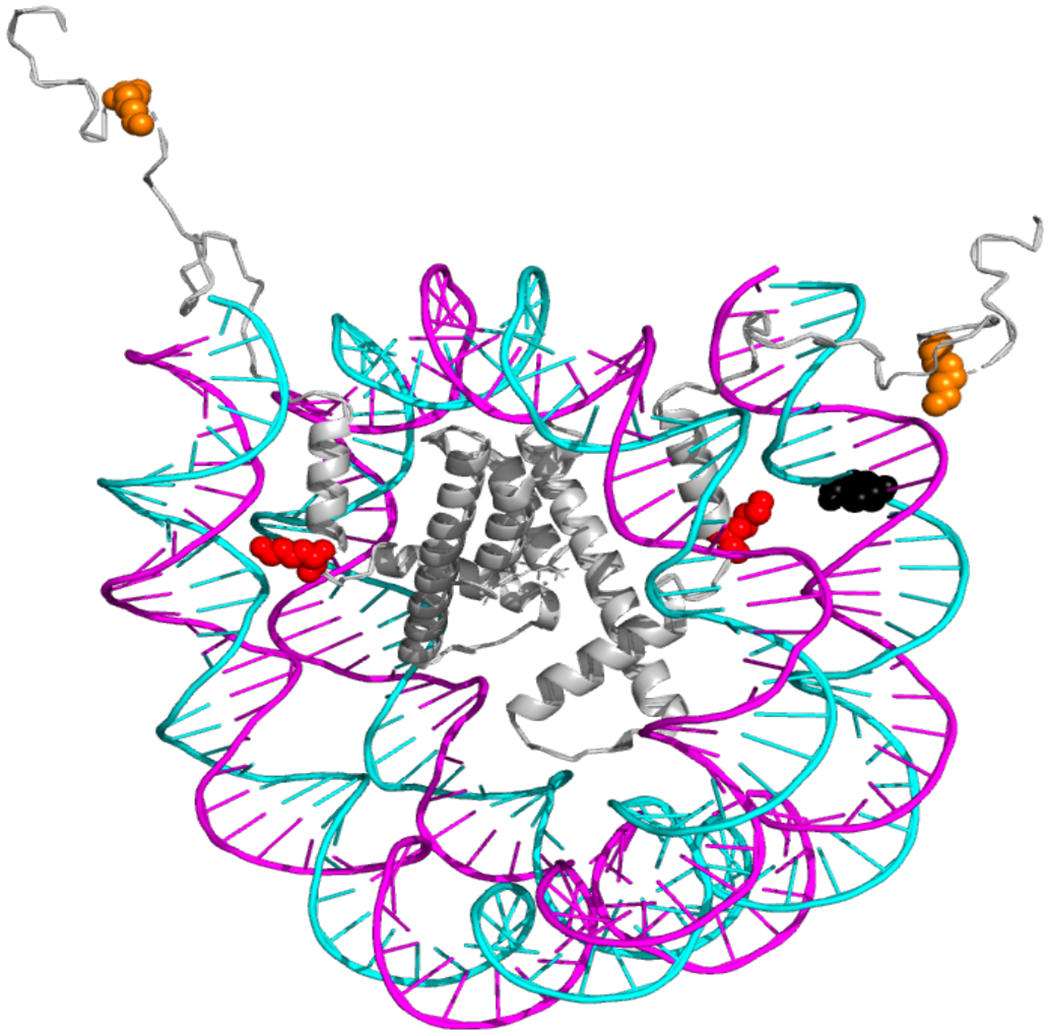

Figure 1.

Positioning of tetrahydrofuran (THF) relative to histone H3 site-specific acetylation in reconstituted nucleosomes and its effect on APE1 activity. The NCP crystal structure [Protein Data Bank (PDB) code IKX5] was modified to indicate the location of the THF lesion placed within the 147 bp 601 synthetic DNA sequence. The complete sequence is listed in Table S1 with the chemical structure of the THF highlighted in black in this figure. The two copies of histone H3 are shown in gray, residue H3K14 is shown in orange and H3K56 in red. Because this DNA lesion is near the DNA ends, it does not maintain definitive rotational orientation but it was chosen due to its proximity to H3K56Ac, strategically located within the region of increased nucleosome dynamics and accessibility1, 2. Numbers in parenthesis indicate the number of nucleotides from the 5′ end (+) of the dyad center of symmetry, which is designated as translational position 0.

Figure 2.

Incision of 601 NCPs. A) APE1 activity was assessed under single turnover conditions (enzyme is in excess relative to substrate). The mean of at least triplicate experiments was plotted and fitted to a single exponential equation given under Materials and Methods. Acetylation of H3K56 enhances the single turnover rate by ~4-fold in 601 well-positioned NCPs. B) The kobs were plotted, and an unpaired, two-tailed t-test was performed with asterisks denoting a significant difference (p-value <0.0001).

Histone acetylation effects are site-specific and enhance catalytic cycling of APE1; the effect is reversible in the presence of the functional H3K56 deacetylase SIRT6.

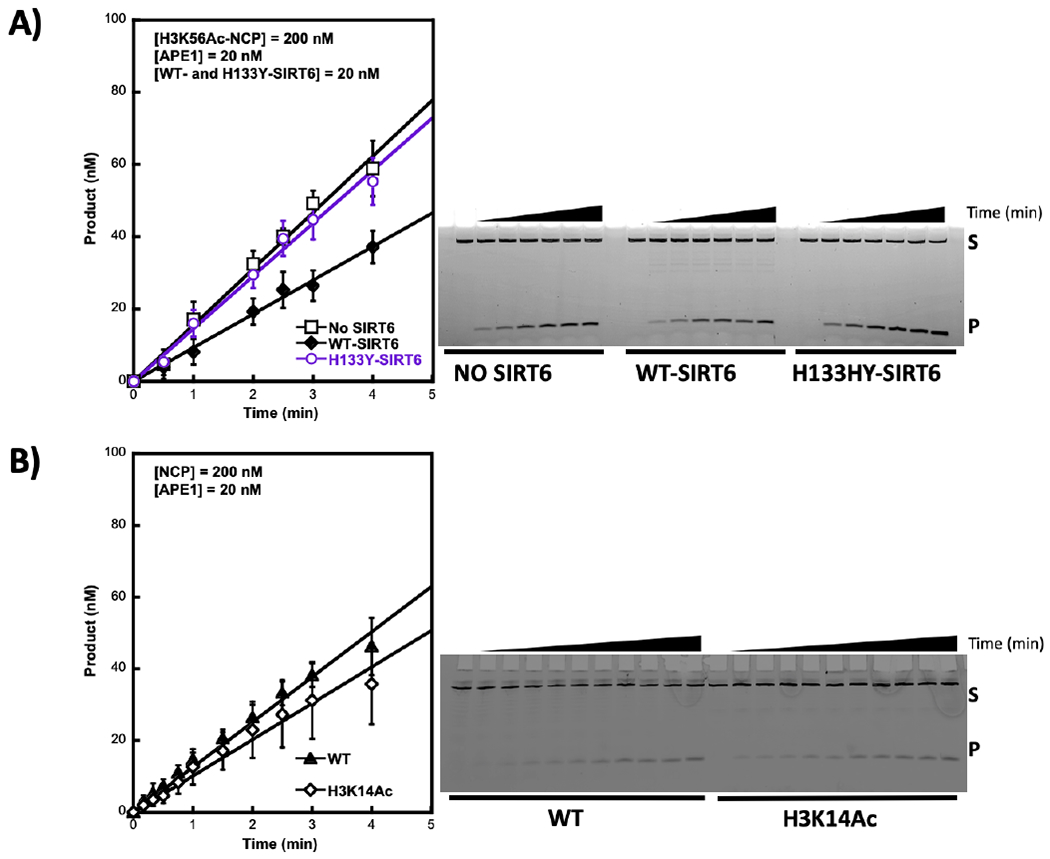

To further characterize the effect of H3K56Ac on APE1 activity, we utilized strand incision assays under steady-state conditions. In this assay with a limiting concentration of APE1, the incision rate constant reflects the catalytic step of enzyme dissociation from the incision product13. First, the steady-state rates with H3K56 acetylated NCPs and H3K56 unacetylated NCPs were compared, and the results revealed more activity with the acetylated NCPs (Figure 3A). Next, we confirmed that removal of the acetyl group from within the H3K56Ac substrate would alter the steady-state rate of APE1. Recombinant wild-type and a negative control mutant of SIRT6,H133Y, were purified, and the NAD+-dependent deacetylase activity of these enzymes was confirmed. As shown in Figure S2A, wild-type SIRT6 possessed deacetylase activity, while the negative control mutant (H133Y SIRT6) as expected, did not39. Importantly, wild-type SIRT6 deacetylated the H3K56Ac-NCP substrate (Figure S2B). Preincubation of the H3K56Ac-NCP substrate with wild-type SIRT6 resulted in a decrease in the steady-state rate constant of APE1, to a level equivalent to that found for unacetylated substrate (Figure 3A). Incubation of the same substrate with the negative control H133Y-SIRT6 did not have this effect (Figure 3A). Previously, H3K56Ac was shown to enhance accessibility of a restriction enzyme near the NCP DNA ends21, suggesting enzyme turnover may be enhanced due to increased nucleosome dynamics. These results are reminiscent of our result due to acetylation on APE1 activity. To determine if this enhancement was due to site-specific acetylation, corresponding to the direct effects of acetylation on nucleosome dynamics, we used an alternate substrate containing H3K14 acetylation, i.e., at the N-terminal tail as illustrated in Figure 1. H3K14 acetylation, unlike H3K56Ac, does not enhance nucleosome dynamics as previously shown by restriction enzyme accessibility assays21. Histone acetylation at H3K14 did not alter the steady-state kinetics of APE1 (Figure 3B). This supports the interpretation that the observed effects were due to increased nucleosome dynamics at H3K56 as a function of acetylation rather than to an interaction of APE1 with any histone acetyl group.

Figure 3.

Histone H3 acetylation site-specifically enhances APE1 activity. A) NCPs containing H3K56Ac (200 nM) were pre-incubated with SIRT6 (WT or H133Y) or without SIRT6 for 15 min at 37 °C in the presence of NAD+ (150 μM). The APE1 reaction was initiated by the addition of APE1 (20 nM). B) NCPs (WT or H3K14Ac) were incubated with APE1 (20 nM) for the specified times. All reactions were quenched with 100 mM EDTA, followed by isolation of the DNA via phenol:chloroform:isoamyl alcohol extraction. DNA was then denatured with formamide and substrate (S) and product (P) were separated in a 20% 7 M urea polyacrylamide denaturing gel (representative images shown on the right). Data points represent the mean of at least triplicates ± SD.

Acetylation at H3K56 does not override the NCP constraint imposed on BER enzymes.

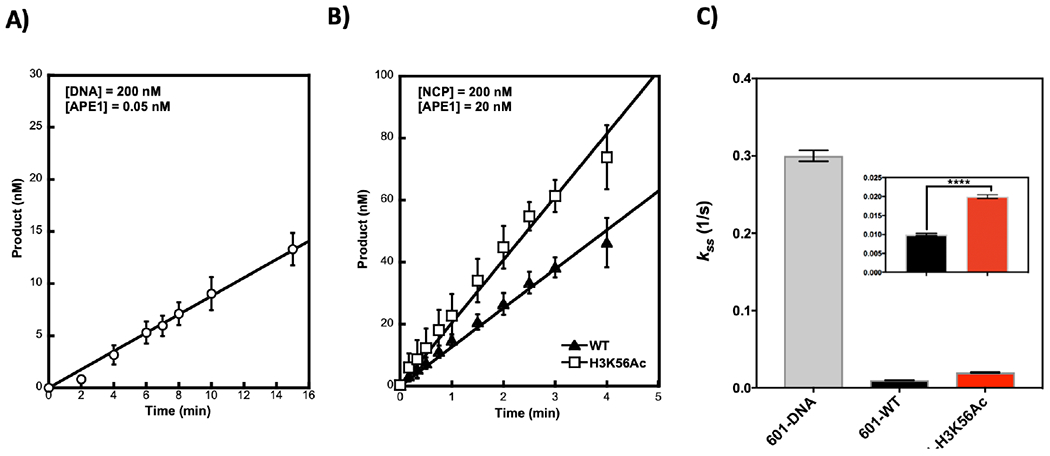

APE1 activity was previously shown to be hindered within the context of NCPs in more centrally located (closer to the dyad) AP sites15, with an approximate inhibition of 10-fold for a specified site. Here, this inhibition was characterized by comparing the steady-state rate constants and evaluating parameters that could override the inhibition. Our results show that APE1 exhibited similar steady-state rate constants (kss) with free DNA substrates as that previously reported14, i.e., 0.3 ± 0.0003 (1/s) (Figure 4A)13, 14 and independent of DNA sequence as the 5S-DNA kss is identical (Figure S4A). In the NCP, there was significant inhibition since the kss was decreased 30-fold in 601-WT-NCP (+64) (Figure 4C). This inhibition was somewhat alleviated in the presence of H3K56Ac (Figure 4B). Importantly, DNA sequence alone presented a more important factor for overriding the structural constraints posed by the histones given that kss in the 5S-NCP (−67) was diminished only 2-fold (Figure S4 B and C). The results suggest that regulation of APE1-mediated repair may be achieved intrinsically, with H3K56Ac being important in mediating repair in well-positioned NCPs. However, the direct contribution of any specific parameter, including H3K56Ac, to overall repair in vivo cannot be precisely discerned given that chromatin organization is much more complex and the mechanisms that regulate DNA accessibility are multiple and often interconnected. Nonetheless, in vitro experiments provide an important framework that can’t be addressed in vivo.

Figure 4.

Steady-state kinetics of APE1 activity on 601 DNA (A) and NCPs (B). Substrates were incubated with the specified amount of APE1. Reaction time point samples were taken and quenched with an equal volume of 100 mM EDTA, and samples were processed and analyzed as in Figure 3, except NAD+ was omitted in these reactions. Data points represent the mean of at least triplicates ± SD. Rate constants were calculated using the initial velocity and total APE1 concentration: Initial rate = V0/[Et] and data are plotted in panel (C). The kss or rate of enzyme turning over is likely limited by the rate of product release.

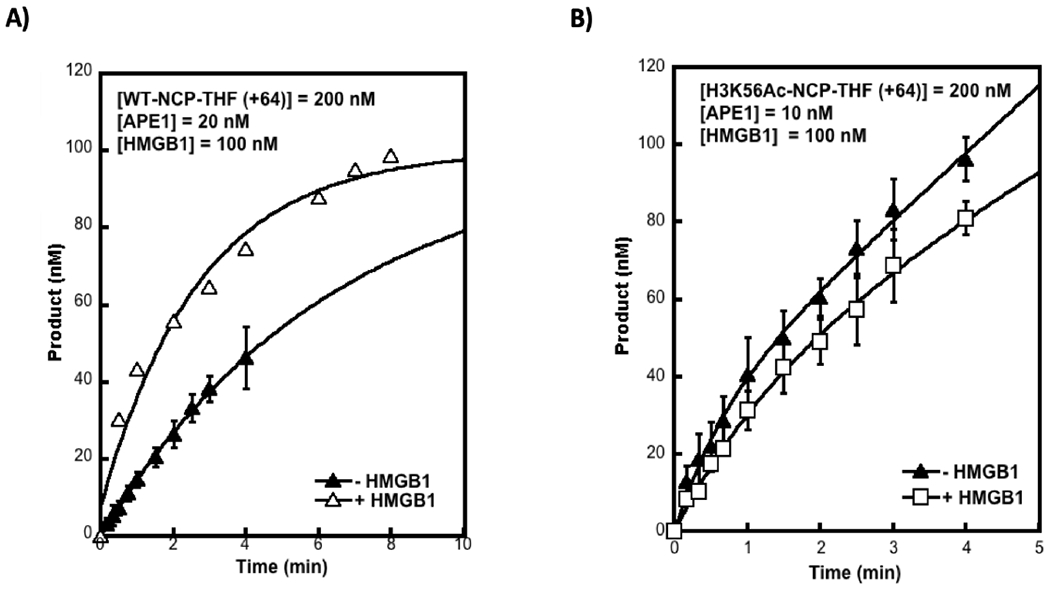

The chromatin-associated architectural protein high-mobility group B1 (HMGB1) promotes APE1 activity only in unacetylated, well-positioned NCPs.

HMGB1 is one of the few architectural proteins exhibiting dual roles in promoting BER: 1) via its direct interaction with BER enzymes such as APE1 and FEN135, 40; and 2) indirectly by exerting chromatin remodeling effects to promote pol β-mediated DNA synthesis41. HMGB1 has been shown to recognize distorted regions of DNA. The presence of a single AP site in DNA may not present a significant distortion, although its presence in the histone octamer induces local changes that deviate from association of undamaged DNA with the histone octamer. In fact, the presence of a single AP site, 29 nucleotides from the ends, has been shown to decrease NCP thermal stability, and this instability is enhanced with the addition of another AP site symmetrically placed on the opposite side of the DNA ends42. Importantly, the AP site can adopt alternative B-form and inchworm configurations42. In light of the locations of H3K56 acetylation and the AP site in our substrates, it is plausible that acetylation may provide a structural readout in addition to that of HMGB1. To evaluate potential combinatorial roles of HMGB1 and H3K56Ac on APE1 activity, steady-state assays were performed following preincubation of H3K56 unacetylated and acetylated NCPs with HMGB1. The results indicate that HMGB1 enhanced the APE1 rate (i.e., kss) 5-fold in the unacetylated 601-NCPs (+64) (Figure 5A). HMGB1 did not have an effect on APE1 activity in H3K56Ac-NCPs, but the initial rate constant due to H3K56Ac is comparable to that obtained in Figure 3A and 4C (Figure 5B). These results suggest H3K56Ac and HMGB1 may play overlapping roles in promoting accessibility by transiently disrupting histone-DNA interactions; transient competition between HMGB1 and APE1 may be promoted by H3K56Ac due to enhanced accessibility to nucleosomal DNA near the DNA ends, although unlikely given that HMGB1 is not known to form a stable complex with NCPs43. Additionally, HMGB1 is proposed to recognize distortions on the DNA and intercalates in the DNA’s minor groove while also interacting with the N-terminal tail of histone H343; it is plausible that H3K56Ac as well as the presence of the AP-site lesion may modulate these interactions via multiple mechanisms. For example, H3K56Ac, due to enhanced DNA breathing, may promote alternate lesion configurations than those adopted in 601-WT-NCPs, while also distinctly regulating the intercalation of the C-terminal of HMGB1 and its known interaction with the N-terminal tail of histone H3. The overall effects on this regulation may have a different impact in shaping histone-DNA interactions. Consequently, the enhanced dynamic nature of H3K56Ac may dilute the effects of HMGB1 given that they appear to be precisely dependent on the strength of the histone-DNA interactions as proposed by Joshi et al. Thus, HMGB1 appears to weaken or relax these interactions43. Our additional results with the 5S-NCPs suggest this might be the case since these NCPs are more unstable compared to 601-NCPs, exhibiting weaker histone-DNA interactions, and HMGB1 does not have an effect on APE1 activity in this case (Figure S4D). Alternate lesion configurations due to weaker histone-DNA interactions as a result of H3K56Ac or weaker DNA sequence could promote the inchworm configuration of the AP site, thereby counteracting the effects of enhanced accessibility due to H3K56Ac. Taken together our results provide insight into the complex regulation of histone site-specific acetylation and BER. These results confirmed that there was an increase in APE1 activity due to H3K56 acetylation or in the presence of HMGB1, but these two mechanisms are not additive. To more accurately delineate the role of HMGB1 in enhancing APE1 activity only in stable, well-positioned NCPs, high resolution structural analysis will be needed. AFM analyses have revealed some global structural differences due to the action of HMGB143 and this suggests these subtle differences may have a significant impact in weakening stronger histone-DNA interactions, resulting in a more ‘relaxed’ NCP structure. This effect is ‘diluted’ in already weakened histone-DNA interactions due to H3K56Ac and 5S-DNA positioning.

Figure 5.

Effect of HMGB1 on NCPs. Nucleosome core particles (200 nM) containing 601 WT (A) or H3K56Ac (B) were incubated with 100 nM of HMGB1 for 15 min prior to the addition of APE1 (as indicated). Quenching of the reaction at each time point was performed with 100 mM EDTA, following by isolation of the DNA and its fractionation via denaturing PAGE as described previously. Data represent the mean of at least triplicates ± SD. In panel (A), the steady-state rate constant of APE1 incision in the presence of HMGB1 = 0.05/s ± 0.007, showing a 5-fold enhancement in its turnover. In 601-H3K56AC- NCPs (B), the rate constant is unchanged in the presence of HMGB1.

DISCUSSION

Packaging of eukaryotic DNA into chromatin, although necessary, presents a formidable steric constraint on most DNA transactions. Consequently, modulation of the chromatin landscape and local changes in the fundamental unit of chromatin, the nucleosome, have been shown to be a critical step in many DNA-templated processes, including DNA repair. Histone H3 lysine 56 (H3K56) acetylation (Ac) has been previously identified as a unique mark for its role in maintaining genomic stability44, although the details on the mechanism are not fully understood. In fact, conflicting reports exist as to how the levels of H3K56Ac change in response to DNA damage26, 27. The uncertainty on this regulation is further confounded by the direct action of this modification in promoting DNA unwrapping22, 23, yet in vitro results show an inhibition of Pol β-mediated DNA synthesis for regions outside the dynamic range where the DNA ends (~ 13 bp) transiently unwrap21. Additionally, overexpression of the NAD+-dependent deacetylase targeting H3K56Ac, SIRT6, increases BER efficiency45. These studies warranted further investigation in a simplified in vitro system to comprehensively determine direct effects of Ac and provide a rationale for some of these discrepancies. In this study, we have uncovered a link between H3K56Ac and APE1-mediated repair of AP sites in vitro.

Mammalian cells expressing H3K56R mutants have increased levels of spontaneous DNA damage and are more sensitive to DNA damaging agents, including MMS44. This suggests acetylation at this site is critical in maintaining genomic stability by enhancing BER-mediated repair. Our in vitro results strengthen this conclusion given that APE1 activity (Figure 2) and its turnover (Figures 3 and 4) are significantly enhanced by H3K56Ac. These results suggest the observed increase in DNA unwrapping due to H3K56Ac in the DNA ends enhances APE1 transactions at the DNA lesion. Acetylation at H3K14, which does not change nucleosome dynamics, does not have an effect on APE1 activity (Figure 3B), indicating the location of the DNA lesion with respect to the site of acetylation and its ability to increase nucleosome dynamics is critical. Equally important, DNA sequence and consequently NCP stability plays a significant role in this regulation, where APE1 strand incision in weakly positioned 5S-NCPs is unaffected by H3K56Ac under steady-state conditions. However, due to a decrease in NCP stability, they are more amenable for repair compared to 601-NCPs (Figures 4C and S4C). Acetylation at H3K56 in 5S-NCPs produces a small inhibition of APE1 activity (Figure S3) only for the population that repairs more slowly, which may be due to the presence of linker DNA and H3K56Ac changing the preferential interactions of the N-terminal tails with linker DNA46. Structural characterization of nucleosomes containing the acetylation mimic H3K56Q by X-ray crystallography did not reveal any significant differences compared to WT. However, this mutation decreased oligomerization only in sub-saturated nucleosomal arrays, leading to more open chromatin47. This suggests the effects by H3K56Ac may be too transient to trap by static methods.

We turned to biochemical studies to determine the effects of removing acetylation at H3K56 on APE1 activity. Interestingly, only WT SIRT6 with deacetylase activity was able to reverse the enhancement of APE1 strand incision due to H3K56Ac (Figure 3A). This demonstrated acetylation at this site is responsible for the enhanced repair, and this deacetylation activity of SIRT6 may play a significant role in vivo in addition to the potential activation of PARP145. Interestingly, others have observed that SIRT6 deficient cells are hypersensitive to DNA-damaging agents, and this sensitivity can be rescued by overexpression of Pol β dRP lyase domain36.

Our results suggest a potential role for SIRT6 during BER in the context of chromatin and highlight the need for its deacetylation activity. It is still unclear, whether its ADP ribosylation activity targets histones and the effect in a potential regulation of BER proteins themselves, as SIRT6 was previously shown to co-immunoprecipitate with APE148. Moreover, SIRT6 has a role in DSB repair, also in a PARP1-dependent manner49, and clustered BER lesions can lead to DSBs, inducing cell death. Chronic exposure to BER-repaired DNA damage is more likely to lead to these types of lesions due to SSB conversion to DSBs during replication, and thus, cells are likely to become hypersensitive to this treatment; whereas, acute treatment may allow lesions to be repaired in a PARP-1-dependent manner before the next round of replication.

Remarkably, genome-wide analyses have shown H3K56Ac to be enriched at promoter regions27. Promoter regions contain more stable or well-positioned NCPs compared to NCPs distant from transcription start sites. Therefore, it is plausible that this regulation may have important biological implications for the repair of well-positioned NCPs near promoter regions. The enhancement in APE1 strand incision activity was consistent with the increased level of DNA breathing reported by others, ranging from 3- to 7-fold22, 23. These results suggest that H3K56Ac may have a direct effect on BER in vivo, which is directly linked to a combinatorial effect of the current chromatin landscape at the time of DNA damage and the induced chromatin plasticity by DNA damage.

The chromatin landscape, in addition to being regulated by histone PTM status and DNA damage induction, is subject to structural constraints by the abundance of non-histone chromosomal proteins. One such protein with overlapping roles in shaping chromatin landscape and influencing BER is HMGB1, previously shown to stimulate APE1 activity by 10-fold under steady-state conditions using free DNA as a substrate35. In this study, for the first time, we demonstrate a potential overlap between H3K56Ac and HMGB1 in promoting APE1 activity, where a combinatorial effect between these two mechanisms is not observed (Figure 5), suggesting they may play overlapping roles in vivo. Increased DNA unwrapping due to H3K56Ac may mask minor structural distortion on DNA associated with the lesion, and consequently, HMGB1 no longer recognizes these structural distortions. This might be a site-specific lesion effect, as it is still plausible that in an acetylated substrate, where the lesion is distant from increased dynamics, HMGB1 may still recognize and enhance repair. Alternatively, HMGB1 may also compete with other repair factors, decreasing overall BER efficiency. This potential competition will more likely be amplified in regions where accessibility to the lesion is more limited.

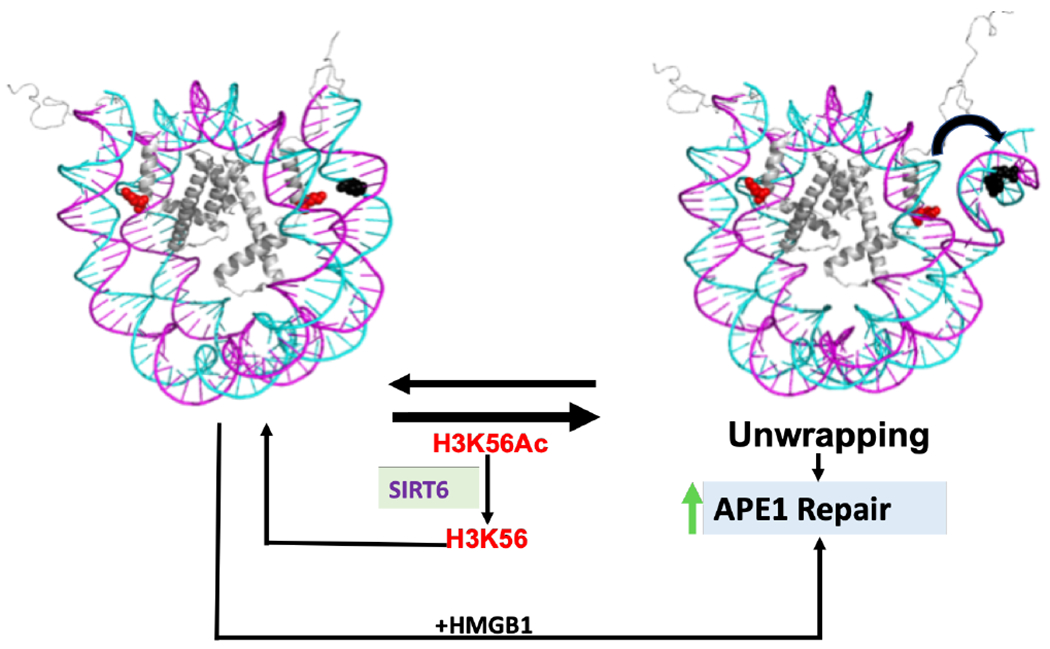

Greenberg and colleagues have made additional observations on spontaneous AP site strand incision mediated by histone lysines and have demonstrated that the rate of strand incision occurs 60-fold faster in NCPs compared to that in free DNA18, 50, 51. Importantly, histone lysine-catalyzed AP site strand incision can lead to covalent protein-DNA crosslinks, and this ultimately results in the activation of alternate repair pathways. It is still unknown how pathway coordination may occur in this scenario, but it is possible that enzymes participating in different repair pathways such as SIRT6 and PARP1 may coordinate processing of these BER lesions that have become more potentially cytotoxic lesions if not rapidly repaired. Our study suggests the repair of AP sites by APE1 in NCPs can be enhanced primarily by intrinsic factors such as histone acetylation, in a site-specific manner, and the presence of non-histone proteins that regulate the chromatin landscape (i.e., HMGB1) (Figure 6). Consequently, it is not surprising that despite the high number of baseline AP sites present in the mammalian genome, repair of these lesions is efficiently achieved via a number of intrinsic mechanisms.

Figure 6.

Model for intrinsic and extrinsic APE1 activity regulation in 601-NCPs. Acetylation of H3K56 promotes DNA unwrapping, allowing for enhanced APE1 activity on a lesion located 9 bp from the DNA ends, within the dynamic range (~13 bp from DNA ends). This enhancement is reversed in the presence of the H3K56 deacetylase SIRT6. An alternate method for regulating APE1 activity also occurs in the absence of H3K56Ac by the action of HMGB1.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We thank Dr. Rajendra Prasad for discussion and technical assistance with protein purification of SIRT6 and Dr. William A. Beard for critical discussion of this manuscript.

Funding Sources

Research has been supported by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences [Z01ES050158 and Z01ES050159]. Funding for open access charge: Intramural Research Program of the National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences [Z01ES050158 and Z01ES050159].

ABBREVIATIONS

- H3K56Ac

H3K56 acetylation

- NCP

nucleosome core particle

- BER

base excision repair

- APE1

AP endonuclease 1

- PTM

posttranslational modification

- DPC

DNA-protein crosslink

Footnotes

Supporting Information

Table S1: DNA sequences; Figure S1: NCP evaluation and confirmation of histone site-specific acetylation; Figure S2: Characterization of SIRT6 deacetylation activity; Figure S3: Single-turnover kinetic analysis of APE1-catalyzed incision of the THF group in 5S-NCPs as a function of H3K56 acetylation; Figure S4: Steady-state kinetic analysis of APE1 catalyzed incision of THF in 5S-NCPs as a function of H3K56 acetylation.

References

- [1].Simon M, North JA, Shimko JC, Forties RA, Ferdinand MB, Manohar M, Zhang M, Fishel R, Ottesen JJ, and Poirier MG (2011) Histone fold modifications control nucleosome unwrapping and disassembly, Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 108, 12711–12716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].North JA, Shimko JC, Javaid S, Mooney AM, Shoffner MA, Rose SD, Bundschuh R, Fishel R, Ottesen JJ, and Poirier MG (2012) Regulation of the nucleosome unwrapping rate controls DNA accessibility, Nucleic Acids Res 40, 10215–10227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Lindahl T (1993) Instability and decay of the primary structure of DNA, Nature 362, 709–715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Chastain PD 2nd, Nakamura J, Rao S, Chu H, Ibrahim JG, Swenberg JA, and Kaufman DG (2010) Abasic sites preferentially form at regions undergoing DNA replication, FASEB J 24, 3674–3680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Nakamura J, and Swenberg JA (1999) Endogenous apurinic/apyrimidinic sites in genomic DNA of mammalian tissues, Cancer Res 59, 2522–2526. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Loeb LA, and Preston BD (1986) Mutagenesis by apurinic/apyrimidinic sites, Annu Rev Genet 20, 201–230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Hoeijmakers JH (2001) Genome maintenance mechanisms for preventing cancer, Nature 411, 366–374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Tell G, and Wilson DM 3rd. (2010) Targeting DNA repair proteins for cancer treatment, Cell Mol Life Sci 67, 3569–3572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Demple B, and Sung JS (2005) Molecular and biological roles of Ape1 protein in mammalian base excision repair, DNA Repair (Amst) 4, 1442–1449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Larsen E, Meza TJ, Kleppa L, and Klungland A (2007) Organ and cell specificity of base excision repair mutants in mice, Mutat Res 614, 56–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Xanthoudakis S, Smeyne RJ, Wallace JD, and Curran T (1996) The redox/DNA repair protein, Ref-1, is essential for early embryonic development in mice, Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 93, 8919–8923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Raffoul JJ, Heydari AR, and Hillman GG (2012) DNA Repair and Cancer Therapy: Targeting APE1/Ref-1 Using Dietary Agents, J Oncol 2012, 370481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Maher RL, and Bloom LB (2007) Pre-steady-state kinetic characterization of the AP endonuclease activity of human AP endonuclease 1, J Biol Chem 282, 30577–30585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Freudenthal BD, Beard WA, Cuneo MJ, Dyrkheeva NS, and Wilson SH (2015) Capturing snapshots of APE1 processing DNA damage, Nat Struct Mol Biol 22, 924–931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Hinz JM (2014) Impact of abasic site orientation within nucleosomes on human APE1 endonuclease activity, Mutat Res 766-767, 19–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Hinz JM, Mao P, McNeill DR, and Wilson DM 3rd. (2015) Reduced Nuclease Activity of Apurinic/Apyrimidinic Endonuclease (APE1) Variants on Nucleosomes: IDENTIFICATION OF ACCESS RESIDUES, J Biol Chem 290, 21067–21075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Schermerhorn KM, and Delaney S (2013) Transient-state kinetics of apurinic/apyrimidinic (AP) endonuclease 1 acting on an authentic AP site and commonly used substrate analogs: the effect of diverse metal ions and base mismatches, Biochemistry 52, 7669–7677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Sczepanski JT, Wong RS, McKnight JN, Bowman GD, and Greenberg MM (2010) Rapid DNA-protein cross-linking and strand scission by an abasic site in a nucleosome core particle, Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 107, 22475–22480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Sczepanski JT, Jacobs AC, Van Houten B, and Greenberg MM (2009) Double-strand break formation during nucleotide excision repair of a DNA interstrand cross-link, Biochemistry 48, 7565–7567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Wang R, Yang K, Banerjee S, and Greenberg MM (2018) Rotational Effects within Nucleosome Core Particles on Abasic Site Reactivity, Biochemistry 57, 3945–3952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Rodriguez Y, Hinz JM, Laughery MF, Wyrick JJ, and Smerdon MJ (2016) Site-specific Acetylation of Histone H3 Decreases Polymerase beta Activity on Nucleosome Core Particles in Vitro, J Biol Chem 291, 11434–11445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Neumann H, Hancock SM, Buning R, Routh A, Chapman L, Somers J, Owen-Hughes T, van Noort J, Rhodes D, and Chin JW (2009) A method for genetically installing site-specific acetylation in recombinant histones defines the effects of H3 K56 acetylation, Mol Cell 36, 153–163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Shimko JC, North JA, Bruns AN, Poirier MG, and Ottesen JJ (2011) Preparation of fully synthetic histone H3 reveals that acetyl-lysine 56 facilitates protein binding within nucleosomes, J Mol Biol 408, 187–204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Michishita E, McCord RA, Boxer LD, Barber MF, Hong T, Gozani O, and Chua KF (2009) Cell cycle-dependent deacetylation of telomeric histone H3 lysine K56 by human SIRT6, Cell Cycle 8, 2664–2666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Maas NL, Miller KM, DeFazio LG, and Toczyski DP (2006) Cell cycle and checkpoint regulation of histone H3 K56 acetylation by Hst3 and Hst4, Mol Cell 23, 109–119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Das C, Lucia MS, Hansen KC, and Tyler JK (2009) CBP/p300-mediated acetylation of histone H3 on lysine 56, Nature 459, 113–117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Tjeertes JV, Miller KM, and Jackson SP (2009) Screen for DNA-damage-responsive histone modifications identifies H3K9Ac and H3K56Ac in human cells, EMBO J 28, 1878–1889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Fernandez AG, and Anderson JN (2007) Nucleosome positioning determinants, J Mol Biol 371, 649–668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Luger K, Rechsteiner TJ, and Richmond TJ (1999) Expression and purification of recombinant histones and nucleosome reconstitution, Methods Mol Biol 119, 1–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Luger K, Rechsteiner TJ, and Richmond TJ (1999) Preparation of nucleosome core particle from recombinant histones, Methods Enzymol 304, 3–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Duan MR, and Smerdon MJ (2010) UV damage in DNA promotes nucleosome unwrapping, J Biol Chem 285, 26295–26303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Rodriguez Y, and Smerdon MJ (2013) The structural location of DNA lesions in nucleosome core particles determines accessibility by base excision repair enzymes, J Biol Chem 288, 13863–13875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Rodriguez Y, Howard MJ, Cuneo MJ, Prasad R, and Wilson SH (2017) Unencumbered Pol beta lyase activity in nucleosome core particles, Nucleic Acids Res 45, 8901–8915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Catez F, Yang H, Tracey KJ, Reeves R, Misteli T, and Bustin M (2004) Network of dynamic interactions between histone H1 and high-mobility-group proteins in chromatin, Mol Cell Biol 24, 4321–4328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Prasad R, Liu Y, Deterding LJ, Poltoratsky VP, Kedar PS, Horton JK, Kanno S, Asagoshi K, Hou EW, Khodyreva SN, Lavrik OI, Tomer KB, Yasui A, and Wilson SH (2007) HMGB1 is a cofactor in mammalian base excision repair, Mol Cell 27, 829–841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Mostoslavsky R, Chua KF, Lombard DB, Pang WW, Fischer MR, Gellon L, Liu P, Mostoslavsky G, Franco S, Murphy MM, Mills KD, Patel P, Hsu JT, Hong AL, Ford E, Cheng HL, Kennedy C, Nunez N, Bronson R, Frendewey D, Auerbach W, Valenzuela D, Karow M, Hottiger MO, Hursting S, Barrett JC, Guarente L, Mulligan R, Demple B, Yancopoulos GD, and Alt FW (2006) Genomic instability and aging-like phenotype in the absence of mammalian SIRT6, Cell 124, 315–329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Yang B, Zwaans BM, Eckersdorff M, and Lombard DB (2009) The sirtuin SIRT6 deacetylates H3 K56Ac in vivo to promote genomic stability, Cell Cycle 8, 2662–2663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Luger K, Rechsteiner TJ, Flaus AJ, Waye MM, and Richmond TJ (1997) Characterization of nucleosome core particles containing histone proteins made in bacteria, J Mol Biol 272, 301–311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Tennen RI, Berber E, and Chua KF (2010) Functional dissection of SIRT6: identification of domains that regulate histone deacetylase activity and chromatin localization, Mech Ageing Dev 131, 185–192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Liu Y, Prasad R, and Wilson SH (2010) HMGB1: roles in base excision repair and related function, Biochim Biophys Acta 1799, 119–130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Balliano A, Hao F, Njeri C, Balakrishnan L, and Hayes JJ (2017) HMGB1 Stimulates Activity of Polymerase beta on Nucleosome Substrates, Biochemistry 56, 647–656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Osakabe A, Arimura Y, Matsumoto S, Horikoshi N, Sugasawa K, and Kurumizaka H (2017) Polymorphism of apyrimidinic DNA structures in the nucleosome, Sci Rep 7, 41783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Joshi SR, Sarpong YC, Peterson RC, and Scovell WM (2012) Nucleosome dynamics: HMGB1 relaxes canonical nucleosome structure to facilitate estrogen receptor binding, Nucleic Acids Res 40, 10161–10171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Yuan J, Pu M, Zhang Z, and Lou Z (2009) Histone H3-K56 acetylation is important for genomic stability in mammals, Cell Cycle 8, 1747–1753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Xu Z, Zhang L, Zhang W, Meng D, Zhang H, Jiang Y, Xu X, Van Meter M, Seluanov A, Gorbunova V, and Mao Z (2015) SIRT6 rescues the age related decline in base excision repair in a PARP1-dependent manner, Cell Cycle 14, 269–276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Angelov D, Vitolo JM, Mutskov V, Dimitrov S, and Hayes JJ (2001) Preferential interaction of the core histone tail domains with linker DNA, Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 98, 6599–6604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Watanabe S, Resch M, Lilyestrom W, Clark N, Hansen JC, Peterson C, and Luger K (2010) Structural characterization of H3K56Q nucleosomes and nucleosomal arrays, Biochim Biophys Acta 1799, 480–486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Hwang BJ, Jin J, Gao Y, Shi G, Madabushi A, Yan A, Guan X, Zalzman M, Nakajima S, Lan L, and Lu AL (2015) SIRT6 protein deacetylase interacts with MYH DNA glycosylase, APE1 endonuclease, and Rad9-Rad1-Hus1 checkpoint clamp, BMC Mol Biol 16, 12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Van Meter M, Mao Z, Gorbunova V, and Seluanov A (2011) Repairing split ends: SIRT6, mono-ADP ribosylation and DNA repair, Aging (Albany NY) 3, 829–835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Zhou C, Sczepanski JT, and Greenberg MM (2012) Mechanistic studies on histone catalyzed cleavage of apyrimidinic/apurinic sites in nucleosome core particles, J Am Chem Soc 134, 16734–16741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Sczepanski JT, Zhou C, and Greenberg MM (2013) Nucleosome core particle-catalyzed strand scission at abasic sites, Biochemistry 52, 2157–2164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.