Abstract

Background

Family members influence maternal, child, and adolescent nutrition and are increasingly engaged in nutrition interventions and research. However, there remain gaps in the literature related to programmatic experiences and lessons learned from engaging these key influencers in nutrition activities.

Objectives

This research aimed to document global health professionals' experiences engaging family members in nutrition activities, and their perceived barriers, facilitators, and recommendations for nutrition activities that engage family members.

Methods

Global health and nutrition professionals were invited to complete an online survey about their experiences engaging family members in nutrition activities. The survey included 42 multiple-choice questions tabulated by frequency and 4 open-response questions, which were analyzed thematically.

Results

More than 180 respondents (n = 183) in 49 countries with experience engaging fathers, grandmothers, and other family members in nutrition activities participated in the survey. Participants highlighted the importance of conducting formative research with all members of the family system and using participatory processes in intervention design and implementation. Respondents reported engaging family members increases support for recommended behaviors, improves program sustainability, and facilitates family and community ownership. Some respondents also shared experiences with positive and negative unintended consequences when engaging family members; for example, one-fifth of participants reported that mothers were uncomfortable with involving men in discussions. Common challenges centered on limited resources for program delivery, not involving all influential family members, and traditional gender norms. Recommendations included incorporating family members in the project design phase and ensuring sufficient project resources to engage family members throughout the project lifecycle.

Conclusions

Surveying global health professionals provides an opportunity to learn from their experiences and fill gaps in the peer-reviewed literature to strengthen intervention design and implementation. Community ownership and sustainability emerged as key benefits of family engagement not previously reported in the literature, but responses also highlighted potential negative unintended consequences.

Keywords: behavior change, behavioral interventions, child nutrition, fathers, gender roles, grandmothers, maternal nutrition, social support

Global health professionals in 49 countries reported that family engagement in nutrition increases support for recommended behaviors, improves program sustainability, and promotes community ownership.

Introduction

Maternal, adolescent, and child nutrition play a critical role in health, growth, and development. Ensuring adequate nutrition for children, adolescents, and women benefits individuals, their families, communities, and national development. Nutrition interventions can reduce maternal and infant mortality and support child growth and development (1). Although much attention has focused on the first 1000 d as a critical period for intervention, recently adolescence has been recognized as a potential second window of opportunity for catch-up growth (2) and a time for supplemental actions to maintain healthy growth trajectories (3). Despite a wealth of evidence on the need and solutions to improve nutrition, challenges with program delivery remain and progress on global nutrition targets has lagged behind (4).

In recognition of the influence of family members on maternal, adolescent, and child nutrition, researchers have highlighted the need for consideration of the structure and dynamics of the family system, which extend beyond the nuclear family, in intervention design and implementation (5, 6). Support from family members is associated with improved nutrition practices and outcomes (7, 8). Maternal and child nutrition interventions and research can be strengthened by engaging family members, such as fathers, grandmothers, siblings, and extended family members, and using a family systems framework that explores and reflects family members’ roles, authority, relationships, and communication (6). Increasingly, nutrition interventions engage influential family members to support recommended practices, and some global frameworks have shifted from a maternal-child dyad focus to include family members (9–11).

Family engagement in adolescent nutrition merits special attention, because children develop greater autonomy and control over food choices during adolescence (12, 13). Diet quality in adolescence affects linear height and body composition, pubertal timing, and chronic disease risk later in life (14). Family remains an important determinant of diet, particularly in traditional food environments, although peers and social environment become greater influences during adolescence (13). Furthermore, adolescents might also be engaged as agents of household behavior change due to their influence on younger siblings (15) and other family members (16).

A previous scoping review identified interventions that engaged family members to improve nutrition from pregnancy through 2 y of age (17). A related systematic review examined the impact of engaging family members on maternal and child nutrition and explored the experiences of mothers and family members who participated in interventions that engaged family members (18). The reviews identified gaps in the literature and intervention approaches. Most interventions reported in these reviews focused on engaging fathers; it was less common for interventions to engage grandmothers or consider the family system more broadly (17, 18). Nearly all of the studies were from sub-Saharan Africa or Asia, with few examples from Latin America and the Caribbean or the Middle East and North Africa (17, 18). Most interventions focused on infant and young child feeding practices, especially breastfeeding, and very few on maternal nutrition (17, 18). Few articles identified by the review included adolescents, and those that did targeted only pregnant adolescents or adolescent mothers (17), except 1 school-based intervention that encouraged older children to share infant and young child feeding (IYCF) information with their mothers (16). Similar to a review of breastfeeding projects that involved fathers (19), only one-third of the interventions in the scoping review reported conducting formative research (17), even though it is critical for the design of maternal and child nutrition interventions (20, 21). The reviews also revealed the need for more implementation research on interventions that engaged family members, similar to recommendations from Cunningham et al. (22) and MacDonald et al. (23). Finally, it is important to consider potential unintended negative consequences resulting from program implementation (24), particularly when engaging men in areas that are traditionally women's domains (19, 25). However, very few of the included studies acknowledged the potential for negative unintended consequences or reported monitoring for them (18).

Since 2010, articles describing nutrition interventions that engaged family members have increased considerably; 77 of the 87 articles included in the scoping review were published between 2010 and 2021, although the earliest article was published in 1990 (17). Although these reviews identified >60 unique projects or interventions that engaged family members in maternal and child nutrition, the reviews are limited because they include only articles published in peer-reviewed journals. Programmatic experiences and learning that are not part of research efforts are not typically included in the peer-reviewed literature, yet documenting and disseminating these experiences is critical to increasing program and intervention effectiveness and impact. To that end, there is a need to systematically collect these valuable programmatic experiences and share the learning with the global nutrition community.

The community of global health and nutrition professionals represents an immensely valuable repository of learning from implementing a wide range of interventions in multiple contexts, which can help address the above gaps. The objectives of this research were to survey global health and nutrition professionals to document: 1) programmatic experiences implementing nutrition interventions that engaged family members in maternal, child, and adolescent nutrition; 2) barriers and facilitators to engaging fathers, grandmothers, and other family members, and 3) recommendations for improving the implementation and impact of activities to engage family members in nutrition.

Methods

We developed a 42-question online survey to understand global health and nutrition professionals' experiences engaging family members in maternal, child, and adolescent nutrition programming (Supplemental Material). The questions were developed based on gaps identified in the peer-reviewed literature, the study team's programmatic experience, and similar data collection efforts with global health and nutrition professionals (26, 27). The survey had predominantly multiple-choice and closed-ended questions, along with 4 open-response questions. Opportunities for respondents to share details and materials from their activities to engage family members in nutrition were provided. Questions were pretested by 5 experts in global health programs who provided feedback on survey content, question clarity, and survey length. The survey was programmed in Qualtrics Online Survey Software in English, although responses were accepted in any language. The survey opened on March 16, 2021 and responses were accepted through April 14, 2021. The survey link was distributed through the following electronic mailing lists: USAID Advancing Nutrition e-mail list, CORE Group Nutrition Working Group, CORE Group Social and Behavior Change Working Group, Interagency Gender Working Group, Agrilinks, Family Included, an internal USAID e-mail listserv, and individual e-mails to global health professionals with experience in family engagement. It was also posted in the Breakthrough ACTION Springboard online community. The median time to complete the survey was 28.8 min.

Descriptive statistics were generated for the quantitative data using Qualtrics and Microsoft Excel. Eligibility for the survey was determined based on self-reported experience engaging family members in nutrition. Incomplete surveys were included if the respondent answered ≥50% of the survey questions. Because gender norms emerged as a major theme in this survey as well as in prior literature, we conducted a post hoc analysis to test for differences in attitudes toward family engagement by gender identity using χ2 tests in Stata 16 (StataCorp LLC).

Open-ended responses were analyzed qualitatively using a 2-step inductive thematic coding process, in which each response was coded by the main topic(s) and then the topics were grouped by theme. All but 2 respondents who answered the open-ended questions responded in English. Responses were submitted by 1 respondent in French and 1 in Arabic, which were translated into English for analysis. Three study team members who were experienced global health professionals, including 2 coauthors (KL and SLM), reviewed the programmatic examples and materials respondents submitted. They selected examples that represent diversity in sector, intervention components, family members engaged, and geographic location to highlight the types of family engagement activities in which survey respondents were involved.

The Institutional Review Board at JSI reviewed the protocol and determined the activity to be exempt from human subjects oversight, and the Institutional Review Board at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill determined it was not human subjects research.

Results

Respondent characteristics

More than 180 individuals who reported engaging family members in nutrition activities completed ≥50% of survey questions (n = 183). Because the survey focused on professionals’ experiences engaging family members in nutrition interventions, individuals who responded “no” to the screener question about prior experience incorporating family engagement were not eligible to complete the survey (n = 37). Because the survey was shared on multiple e-mail listservs, which could have overlapping subscribers, it was not possible to calculate the survey response rate. However, after removing duplicate IP addresses (n = 3), 88 potential participants clicked on the survey link and responded affirmatively to the screener question (i.e., reported having experience engaging family members in nutrition), but answered fewer than half of the survey questions, resulting in a 67.5% completion rate (defined as completing ≥50% of the survey) among eligible individuals who began the survey (183/271 = 67.5%).

Respondent characteristics are presented in Table 1. Respondents living in 49 countries completed the survey (Supplemental Table 1). Over half of respondents (59%) self-identified as women, whereas 39% identified as men and 2% reported another gender identity or preferred not to answer. Respondents worked for nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) (56%), government agencies (20%), and universities or research institutions (12%). They had an average of 14 y of experience (range 1–57 y) and most worked within the nutrition, maternal and child health, and water, sanitation, and hygiene (WASH) sectors. Primary professional responsibilities included program implementation and management (70%), technical assistance (60%), and monitoring and evaluation (51%).

TABLE 1.

Survey respondent characteristics

| Characteristic | Respondents1 (n = 183) |

|---|---|

| Organization, n (%) | |

| Nongovernmental organization | 102 (56) |

| Government | 37 (20) |

| University/research institution | 22 (12) |

| Independent consultant | 11 (6) |

| UN agency | 5 (3) |

| Community-based organization | 3 (2) |

| Civil society organization | 2 (1) |

| Donor | 1 (1) |

| Gender, n (%) | |

| Men | 71 (39) |

| Women | 108 (59) |

| Prefer to self-describe | 2 (1) |

| Prefer not to say | 1 (1) |

| Current location (by region), n (%) | |

| Africa | 103 (56) |

| Americas | 32 (17) |

| Asia | 42 (23) |

| Europe | 6 (3) |

| Oceania | 0 (0) |

| Primary focus area,2n (%) | |

| Nutrition | 169 (92) |

| Maternal and child health | 116 (63) |

| Water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH) | 53 (29) |

| Early child development | 44 (24) |

| Newborn health | 43 (23) |

| Reproductive health | 42 (23) |

| Agriculture | 38 (21) |

| Social protection | 24 (13) |

| Emergency/humanitarian response | 23 (13) |

| HIV/AIDS | 15 (8) |

| Other | 11 (6) |

| Professional responsibilities,2n (%) | |

| Program implementation and management | 128 (70) |

| Technical assistance to programs | 110 (60) |

| Monitoring, evaluation and learning | 96 (52) |

| Program planning | 92 (50) |

| Activity design | 77 (42) |

| Proposal development/grant writing | 76 (42) |

| Advocacy | 76 (42) |

| Research | 68 (37) |

| Formative research | 61 (33) |

| Activity oversight | 61 (33) |

| Other | 10 (5) |

The survey sample (n = 183) was comprised of survey respondents who reported previous experience engaging family members in program activities and completed >50% of the survey.

Multiple responses allowed.

Types of family engagement

Respondents reported implementing activities to engage families in 84 countries. Approximately 81% reported working in a single country, whereas 19% reported activities in multiple countries (Supplemental Table 1). The family members most frequently involved in program activities were fathers (91%), grandmothers and elder women (77%), parents of adolescents (51%), and other female relatives (51%), among others (Table 2). Most activities focused on complementary feeding (84%), breastfeeding (83%), and maternal nutrition (82%), although many respondents also reported engaging families in programs to manage malnutrition (61%) and to improve adolescent nutrition (46%). Although less common, WASH (39%), women's empowerment (37%), early child development (35%), and agriculture (31%) were also reported.

TABLE 2.

Experience implementing activities to engage families

| Experience | Respondents1 (n = 183) |

|---|---|

| Where activities were implemented, by region: | No. of countries |

| Africa | 42 |

| Americas | 15 |

| Asia | 25 |

| Oceania | 2 |

| Total number of countries | 84 |

| Family members involved in the program2,3 | n (%) |

| Fathers (including pregnant women's malepartners) | 167 (91) |

| Grandmothers/elder women | 140 (77) |

| Parents of adolescents | 94 (51) |

| Other female relatives | 94 (51) |

| Grandfathers | 62 (34) |

| Older siblings | 53 (29) |

| Other male relatives | 46 (25) |

| Other | 17 (9) |

| Program outcomes/focus areas2 | |

| Complementary feeding | 153 (84) |

| Breastfeeding | 151 (83) |

| Maternal nutrition | 150 (82) |

| Management of malnutrition | 112 (61) |

| Adolescent nutrition | 84 (46) |

| Water, sanitation, and hygiene (WASH) | 72 (39) |

| Women's empowerment | 68 (37) |

| Early child development | 64 (35) |

| Agriculture | 56 (31) |

| HIV | 21 (11) |

| Other | 11 (6) |

The survey sample (n = 183) was comprised of participants who reported previous experience engaging family members in program activities and completed >50% of the survey.

Multiple outcomes allowed.

All options are in relation to the child or adolescent.

Specific recommendations for family members aligned closely with the most common program focus areas, because respondents frequently reported encouraging women to consume a nutritionally adequate, diverse diet (89%); ensuring women have time for exclusive breastfeeding (89%); and promoting prenatal care attendance (84%) (Table 3). Other behaviors often encouraged at the household level included supporting health care seeking behaviors (75%) and appropriate hygiene practices (74%). Most activities focused on maternal, child, or household-level behaviors; few respondents reported targeting specific behaviors related to adolescents, although 26% encouraged purchasing specific foods for adolescents.

TABLE 3.

Program characteristics

| Recommended behaviors for family members1 | Respondents2 (total n = 183), n (%) |

|---|---|

| Maternal nutrition | |

| Encourage women to eat a diverse, adequate diet | 162 (89) |

| Encourage women to attend antenatal care | 154 (84) |

| Encourage women to rest during pregnancy | 124 (68) |

| Encourage adherence to micronutrient supplements | 116 (63) |

| Provide or purchase specific foods for pregnant or lactating women | 93 (51) |

| Infant and young child care and feeding | |

| Ensure mothers have time for exclusive breastfeeding and child feeding | 163 (89) |

| Share in parenting/caregiving responsibilities with the mother | 122 (67) |

| Practice responsive care behaviors | 118 (64) |

| Provide or purchase specific foods or supplements for infants and young children | 100 (55) |

| Provide opportunities for early learning | 80 (44) |

| Adolescent nutrition | |

| Purchase specific foods for adolescents | 48 (26) |

| Family and household | |

| Support health care–seeking behaviors | 137 (75) |

| Practice appropriate hygiene behaviors | 135 (74) |

| Encourage women to participate in household decision-making | 111 (61) |

| Promote gender equity | 96 (52) |

| Improve family communication | 90 (49) |

| Contribute to household chores | 75 (41) |

| Did not encourage specific behavior | 3 (2) |

| Other | 9 (5) |

| Activities used to engage family members1 | |

| Interpersonal communication | |

| Home visits | 129 (70) |

| Inviting family members to activities for mothers/women (e.g., mothers’ groups) | 121 (66) |

| Facility-based counseling | 99 (54) |

| Fathers’ groups | 86 (47) |

| Grandmothers’ groups | 48 (26) |

| Community mobilization/collective action | |

| Community events | 139 (76) |

| Income-generating activities/savings and loans groups | 72 (39) |

| Other communication | |

| Community media | 88 (48) |

| Mass media | 88 (48) |

| Print media | 87 (48) |

| mHealth (text messages, recorded messages, social media) | 54 (30) |

| Other | |

| Family-friendly health services/facilities | 76 (42) |

| Quality improvement initiatives | 60 (33) |

| Youth clubs/safe spaces for adolescent girls | 51 (28) |

| Worksite programs | 31 (17) |

| Were family members reached together or separately?1 | |

| Mothers and fathers reached together | 120 (66) |

| Fathers reached separately | 89 (49) |

| Mothers and grandmothers reached together | 83 (45) |

| All family members reached together | 77 (42) |

| Grandmothers reached separately | 51 (28) |

| Adolescents and parents reached together | 47 (26) |

| Adolescents and grandmothers reached together | 16 (9) |

| Other | 14 (8) |

| Who delivered the activities/interventions?1 | |

| Community workers/volunteers | 143 (78) |

| Health care providers | 116 (63) |

| Project or partner staff | 106 (58) |

| Community leaders | 94 (51) |

| Mother peer leaders | 74 (40) |

| Father peer leaders | 64 (35) |

| Religious leaders | 57 (31) |

| Grandmother peer leaders | 31 (17) |

| Other | 11 (6) |

Multiple outcomes allowed.

The survey sample (n = 183) was comprised of participants who reported previous experience engaging family members in program activities and completed >50% of the survey.

Engaging family members most frequently occurred through community events (76%), home visits (70%), and inviting other family members to participate in women's groups or activities (66%). About half reported working with fathers’ groups, and about one-quarter of respondents reported working with grandmothers’ groups. Program activities were typically delivered by community workers/volunteers (78%), health care providers (63%), and project or partner staff (58%). Most respondents reported engaging mothers and fathers together (66%), although nearly half engaged fathers separately (49%). Reaching mothers and grandmothers together (45%), the whole family together (42%), and engaging parents and adolescents together (26%) were also common. The majority of respondents reported using a theory to develop program activities (78%) (Supplemental Table 2).

Most respondents had conducted formative research (62%). Among those who had conducted formative research, most respondents involved pregnant women/mothers (90%), fathers (75%), and/or community health workers (67%). Of those who reported using formative research, most used focus group discussions (91%), in-depth interviews (61%), observation (50%), or surveys (50%). Two-thirds of respondents reported collecting monitoring data, which included quantitative measures (e.g., number of family members reached) and qualitative measures (e.g., mothers’ responses to the program) (Table 4). Among those who conducted any type of evaluation (69%), baseline and endline program evaluations were most common, with fewer respondents reporting using midline or process evaluations.

TABLE 4.

Respondents’ experiences with monitoring and evaluation of activities engaging family members in nutrition

| Monitoring and evaluation | Respondents1 (total n = 183), n (%) |

|---|---|

| Collected monitoring data | |

| Yes | 115 (63) |

| No | 63 (34) |

| Type of data collected2,3 | |

| Number of family members reached | 93 (75) |

| Number of activities conducted | 85 (68) |

| Number of people trained by gender | 78 (63) |

| Mothers’ responses to program/intervention | 74 (61) |

| Family members’ responses toprogram/intervention | 67 (56) |

| Level of support by family members | 44 (36) |

| Other | 3 (3) |

| Identified unintended consequences | |

| Yes, through monitoring activities | 50 (27) |

| Yes, through observation/anecdotal evidence | 49 (27) |

| No, did not identify any | 43 (23) |

| We did not monitor for them | 33 (18) |

| Missing | 8 (4) |

| Conducted an evaluation3 | |

| No evaluations conducted | 46 (26) |

| Baseline evaluation | 105 (57) |

| Midline evaluation | 47 (26) |

| Endline evaluation | 78 (43) |

| Process evaluation | 56 (31) |

| Missing | 10 (5) |

The survey sample (n = 183) was comprised of participants who reported previous experience engaging family members in program activities and completed >50% of the survey.

Percentage of those who reported collecting monitoring data (n = 115).

Multiple outcomes allowed.

Respondents reported their efforts to promote the sustainability of activities that engage family members. The most common approaches were integrating family members into ongoing programs (72%), including income-generating activities or saving and loans activities for family members (42%), and/or undertaking policy and advocacy efforts (39%). Several respondents wrote in responses related to plans to incorporate programs into existing structures (e.g., local government, health facilities) or highlighted the need to build local capacity (e.g., train health workers) and involve trusted community leaders (e.g., elders) in programs to increase buy-in and continued support.

Programmatic examples

More than half of respondents (62%) shared information and materials from their interventions to engage family members in nutrition (Supplemental Table 3). Most of the examples engaged fathers, with fewer examples that engaged grandmothers or other family members. Several projects focused on adolescent nutrition engaged adolescents’ parents, but few reported engaging adolescents or older siblings in young child or maternal nutrition interventions. Examples included activities focused on nutrition and health as well as multisectoral nutrition activities. Select examples are presented in Supplemental Boxes 1–5, and include projects in Burkina Faso, Cambodia, Malawi, Mali, and Uganda. These examples share intervention details and lessons learned from engaging family members in multisectoral nutrition activities. Several of these examples started with formative research and/or a gender analysis, used Care Groups (either inviting family members to join women's groups or creating fathers’ or grandmothers’ groups), and identified “Champion Husbands.” In response to challenges with men's participation in Cambodia, a local NGO organized specific meetings for men after work when they would be available to participate, and they engaged community leaders to promote men's participation (Supplemental Box 2).

Benefits of engaging family members

More than 75% of respondents answered the open-ended question about the benefits of engaging family members in nutrition activities. Most often, these respondents reported that engaging family members increases their sense of ownership of program activities and recommended behaviors, and improves sustainability of recommended practices.

“They [family members] start to view themselves as part of the solution.” (Man, based in Africa, employed by donor organization, 15 y of experience)

Multiple participants noted that engaging family members fostered a greater sense of community ownership of program activities, rather than viewing the activities as external (i.e., belonging to or associated with an NGO). Family engagement increased the perception that activities were designed and implemented for and by the community members.

“They own the activities; they take more responsibility to achieve because of the direct involvement.” (Woman, based in Africa, employed by an NGO, years of experience not reported)

Many respondents also reported positive effects on family dynamics such as more joint decision-making and less conflict within the family, which they perceived as contributing to improved nutrition practices and outcomes.

“[Engaging family members contributes to] less conflict between couples and within the family than when just dealing with women and mothers. This comprehensive support leads to increased uptake of behavior change.” (Woman, based in North America, employed by an NGO, 40 y of experience)

Respondents said engaging family members contributes to increased support for mothers.

“The family members support the pregnant, postnatal mothers to look after their diet and nutritional status and ignore the taboos and traditional practices which may prevent the best practices of [maternal and child health] …” (Man, based in Asia, employed by an NGO, 25 y of experience)

Attitudes about engaging other family members

All respondents were asked about their attitudes toward engaging family members in maternal and child nutrition (Figure 1). The vast majority strongly agreed or agreed that nutrition activities should focus on changing social and gender norms rather than individual-level factors (94%). Most respondents agreed or strongly agreed that their organizations always engage other family members in nutrition (85%), and that more evidence is needed about the benefits of engaging family members (86%). Disagreeing with a need for more evidence did not necessarily reflect lack of support for research and evaluation of programs engaging family members, as 1 respondent explained:

FIGURE 1.

Global health professionals’ attitudes about engaging family members in maternal and child nutrition. These 4 questions were displayed to all survey respondents (n = 183), although some left the responses blank. Sample for Q1: n = 163; Q2: n = 160; Q3: n = 157; Q4: n = 158.

“I have indicated that I disagree with the statement ‘more evidence is needed about the benefits of engaging family members in nutrition interventions’ because I believe there is enough evidence to show that this is important and effective at improving nutrition behaviors. What is needed is more data and successful examples of HOW other family members can be effectively engaged.” (Woman, based in Asia, employed by an NGO, 10 y of experience)

Respondents’ opinions were more mixed about concerns around engaging men in areas that are typically women's domains, with more than one-third agreeing that this was of concern to them. In post hoc analyses, no statistically significant differences in attitudes by gender identity were found (Supplemental Table 4).

Perceived challenges

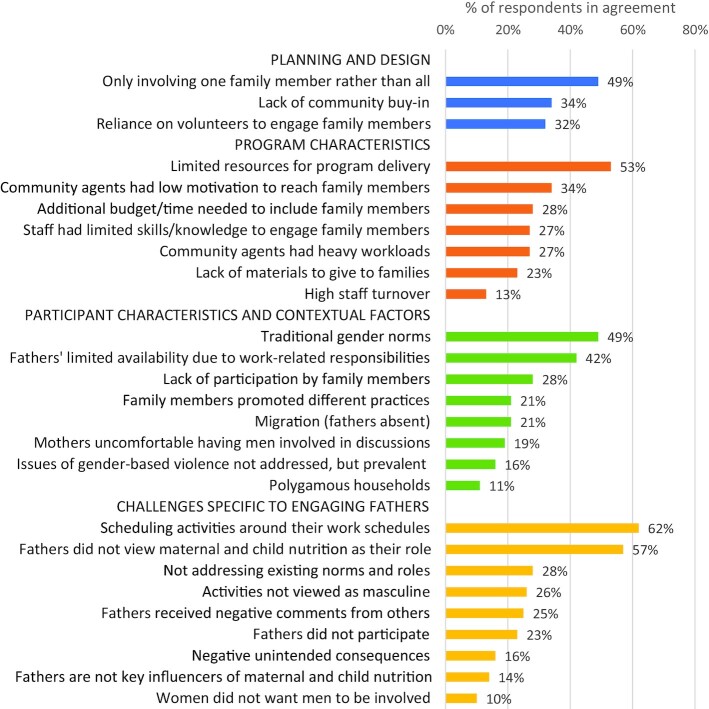

In terms of challenges of engaging family members, survey respondents reported limited resources for program delivery (53%), only involving 1 family member rather than all influential family members (49%), and traditional gender norms (49%) (Figure 2). Common difficulties respondents reported experiencing when engaging fathers specifically (n = 149, Figure 2) included scheduling activities around men's work schedules (62%) and fathers not viewing maternal and child nutrition as their responsibility (57%). A smaller proportion of these respondents also cited not addressing existing gender norms (28%), men not perceiving practices promoted by the program as masculine (26%), men receiving negative comments from other men (25%), and lack of father participation (23%). In contrast to the overall enthusiasm for engaging family members in nutrition activities, 14% of respondents who had engaged fathers selected “Fathers are not key influencers of maternal and child nutrition” as a challenge.

FIGURE 2.

Factors selected as the biggest challenges to effectively engaging family members in nutrition. The survey sample (n = 183) was comprised of participants who reported previous experience engaging family members in program activities and completed >50% of the survey. Multiple responses were allowed. Challenges specific to engaging fathers were only addressed to those who reported prior experience engaging fathers (n = 167).

Unintended consequences

Half of survey respondents reported identifying unintended consequences from their activities engaging family members (54%) (Table 4). These were most often observed through monitoring activities. Other less common approaches to identify unintended consequences included collecting information through routine supportive supervision visits and program meetings, formal data collection activities separate from routine monitoring (e.g., midline evaluations), informal feedback received from program staff or program participants, and informal observations. Through their responses to optional open-ended questions (n = 29/183), respondents reported both positive and negative unintended consequences. Positive unexpected consequences included: attitudes and health outcomes that were not the focus of the program improved, men encouraged other male family members to participate in the program and promoted recommended infant and young child feeding practices, families reported improved relationships or “more peace” in the household, increased client satisfaction, fathers expanded their perceptions of their child care roles, participants initiated income-generating activities, and grandmothers’ participation gave other younger women confidence to participate.

“The mother support group participants noted that men were more supportive and concerned about the way their infants were fed BUT they also became much more accepting of birth control methods and their use within the family, even if this was not at all the focus of the mother support groups.” (Woman, based in Europe, employed by an NGO, 26 y of experience)

The following negative unintended consequences were each reported by 1 or 2 respondents: men being ridiculed by other men for doing “women's work,” mothers and grandmothers not welcoming increased father involvement, fathers dominating decision-making on infant and young child feeding and maternal nutrition, mothers-in-law mandating new behaviors, increased gender-based violence, and asking pregnant women to bring male partners to antenatal care creating problems for women whose husbands did not want to come.

“Asking women to bring the father-to-be to health centers (and giving priority for couples) has led to negative consequences for women whose husbands do not want to come. Stories include women turned away, women inviting the motorbike driver to pose as a husband and then getting accused of cheating by husbands who learn that later.” (Woman, based in North America, employed by an NGO, 20 y of experience)

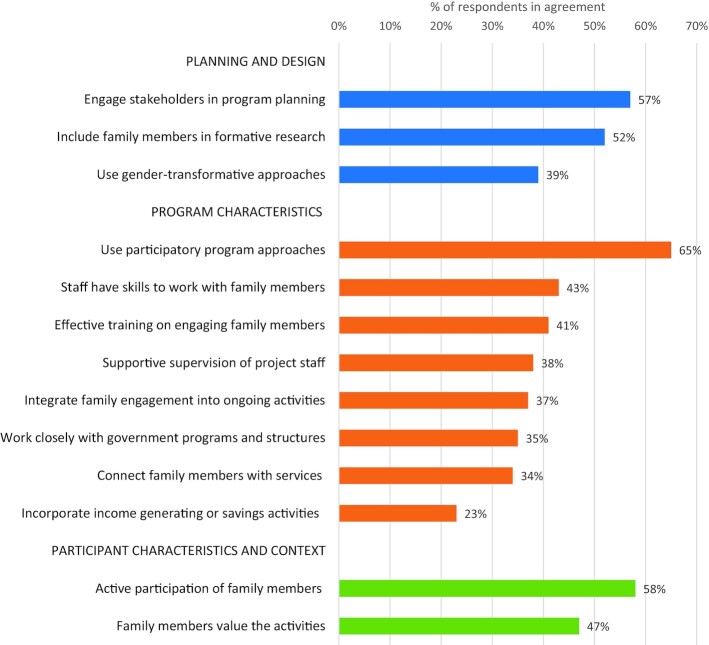

Recommendations for future programs

The most important factors for program success, according to respondents, were: using participatory program approaches (e.g., dialogue, experience sharing, problem solving) (65%), active participation by family members (58%), involving stakeholders in program planning (57%), and incorporating family members into formative research (52%) (Figure 3).

FIGURE 3.

Factors selected as the most important for effectively engaging family members in nutrition. The survey sample (n = 183) was comprised of participants who reported previous experience engaging family members in program activities and completed >50% of the survey. Multiple responses were allowed.

More than half of survey respondents (58%) responded to the open-ended question about recommendations for programs planning to engage family members in the future. Conducting formative research with specific attention to gender norms and expectations was one of the most frequently cited recommendations. Respondents reported formative research as an essential strategy to identify key influencers, unpack gender dynamics, and inform program development and implementation. Several respondents specifically recommended using formative research to facilitate dialogue in the family and community, and thereby contextualize program design:

“The use of formative research is critical to design appropriate programs, and I think that rather than promoting specific practices that men [or] grandparents should do to support women, it is better to create a space where family members can have an open dialogue and collaborate toward a common goal, to promote women's empowerment and while also promoting a shift in masculinity and parenthood that also benefit men (and avoid creating frustrations). Finally, to implement the gender-transformative intervention, the attitudes and behaviors of staff and health providers also need to be considered as it is also a personal journey of change for them in some contexts.” (Woman, based in North America, employed by an NGO, 12 y of experience)

Respondents recommended involving women and mothers in formative research in particular, to find out what women want and if or how they would like family members to be engaged in nutrition activities. As they are often primary caregivers and the intended participants of nutrition programs, women play an essential role in program activities; several respondents recommended identifying what is acceptable and desirable for women in particular.

“…The other part [is] finding out from whom she wants to learn and what kinds of information she want[s] those in the family to know. What is the most important to her?” (Woman, based in Asia, employed by an NGO, 18 y of experience)

Many respondents specifically recommended engaging household heads and key decision-makers in program activities, often citing fathers and grandmothers. A small number also mentioned engaging adolescents as frequent caretakers of younger children and potential agents of household change, or their parents, if the activity focused on adolescent nutrition. Several respondents noted male engagement as essential for future programs, stating that historically this group has been largely ignored, particularly in infant and young child nutrition programs. Engaging grandmothers and elder women was also cited as critical to the success of program activities:

“Active engagement of influential members of the family especially fathers, who in most cases is the head and provider of resources, and grandmothers, whose judgement are often trusted by the society are critical to the success of such programme or activity.” (Man, based in Africa, employed by an NGO, 17 y of experience)

Several respondents also noted the importance of incorporating family members starting from the design phase.

“Other family member engagement [is] not included in initial design of program, so [it is] hard to retrofit these activities. There always seems to be interest from key family members, however.” (Woman based in Africa, employed by an NGO, 10 y of experience)

Planning and budgeting for extra time and resources to engage family members was another salient recommendation. Several participants highlighted potential logistical constraints and stressed the importance of coordinating activities, including formative research, in advance to increase the likelihood that family members are available and engaged. In addition, several respondents recommended incorporating specific monitoring and evaluation strategies into program plans to track progress and document learning about engaging family members.

“Plan for systematic documentation and sharing of information on lessons learnt in regard to engaging family members on nutrition activities” (Woman, based in Africa, employed by an NGO, 5 y of experience).

Discussion

The results of this survey reflect the experiences of global health and nutrition professionals who have engaged family members in maternal, child, and adolescent nutrition programs in 84 countries. Their responses highlight some differences between programmatic experiences and evidence reported in the peer-reviewed literature, and also confirm many findings from peer-reviewed research. This survey provides an opportunity to gain insight from a diverse group of professionals, whose experience has not been systematically documented and shared with the global health and nutrition community. Whereas program participant perceptions of family engagement in nutrition activities have begun to be explored in the literature (18), less attention has focused on the perspectives of program implementers. Given the increasing interest in engaging family members in maternal, child, and adolescent nutrition, and the challenges that this may entail, learning from programmatic experiences is critical for strengthening intervention design, implementation, and research.

Engaging family members in nutrition throughout the lifecycle

Activities that engaged family members most frequently promoted maternal nutrition and exclusive breastfeeding. There are many examples of interventions to engage family members to promote breastfeeding (28, 29), but the focus on maternal dietary diversity diverged from prior reviews (17). Nearly half of respondents reported engaging family members in adolescent nutrition programs. Encouraging families to purchase specific foods or supplements for adolescents was commonly reported, but it is unclear what other behaviors were promoted to families to improve adolescent nutrition. There are limited examples of effective family-based adolescent nutrition interventions from low- and middle-income countries (LMIC) (30, 31), and more examples of evidence-based interventions are needed. Effective interventions that engage family members, most often parents, to improve adolescent nutrition in high-income countries (32) could provide examples that could be adapted for LMIC contexts, particularly when addressing all forms of malnutrition.

Community participation

Respondents reported community ownership, the sustainability of program activities, and support for recommended behaviors as the main benefits of engaging family members. Community ownership and sustainability were not prominent themes in earlier reviews on the topic (17, 18). Given the time- and resource-intensive nature of monitoring phenomena like community ownership and program sustainability, these are not often examined in intervention research, which typically describes shorter-term interventions and programs, nor are they collected as part of the more direct and immediate program outcomes for monitoring and evaluation. However, sustainability is critical for real-world impact. Respondents stressed the importance of community participation during formative research, intervention design, and implementation. Community participation is associated with improved maternal and child health and nutrition (33), but the mechanisms for impact are not well documented (34, 35). In addition to community-level participation, respondents’ recommended interventions provide opportunities for family members to actively participate in activities, consistent with previous research (7, 36). More implementation research is needed to further explore participation (22).

Social and gender norms

Respondents overwhelmingly agreed with a statement that interventions to engage family members should focus more on changing underlying social and gender norms rather than individual behaviors. They also noted challenges specific to gender norms and men's participation, which aligns with findings from a scoping review on the influence of social norms on complementary feeding (37). The review highlighted the need to employ theoretical models of social norms such as diffusion of innovation (38), along with formative research, to design culturally appropriate interventions for normative change, because there are limited examples of effective interventions to change nutrition-related norms (37). Respondents shared examples of multilevel, multicomponent interventions that can address social and gender norms. Additional research is needed to explore strategies to overcome challenges related to engaging family members, with particular attention to engaging fathers and men in nutrition activities.

Positive and negative unintended consequences

Unintended consequences can be positive or negative outcomes resulting from program implementation (24). Respondents were asked about any unintended consequences from engaging family members in nutrition activities. Respondents noted several unintended consequences, both positive and negative. Improved family relationships have been reported as a positive unintended and, to a lesser extent, intended consequence in several studies that engaged family members, but negative unintended consequences are rarely discussed or reported (18). Respondents in this survey shared several examples of unintended consequences resulting from engaging family members. Approximately one-fifth of respondents reported that mothers were uncomfortable having males involved in discussions, which points to the need to use a family systems approach to understand who women want involved and how best to engage family members and men specifically (e.g., separate fathers’ groups, rather than inviting men to women's groups). Although uncommon, increased gender-based violence and men dominating decisions about maternal and child nutrition were noted by a small number of respondents in different contexts and were the most severe negative examples. The potential for negative unintended consequences should be considered when designing interventions and research to engage family members in maternal, child, and adolescent nutrition (22), and structures should be put in place to monitor for and address them during implementation. This is particularly important given that almost two-thirds of survey respondents reported that they were not concerned about engaging men in traditionally women's domains. Reproductive health and HIV programs offer extensive experience and resources with engaging men, including ways to prevent unintended consequences (39), which can inform nutrition programs.

Formative research about family systems

Consistent with previous reviews and research, respondents emphasized the value of formative research for designing activities to engage family members. Formative research serves as an opportunity to collect input from family members and contextualize program design and implementation according to local needs, norms, and goals (6, 37). Focus group discussions, for example, can facilitate dialogue to learn local gender dynamics and decision-making processes and inform the design of interventions that build on existing norms, such as gender roles and expectations. Despite strong support for formative research among respondents, more than one-third reported they had not conducted formative research to inform interventions to engage family members in nutrition. Although reports of formative research are much higher among survey respondents compared with other reviews of interventions to engage men (19) or family members (17), it is still not universal. In addition, it was far more common for respondents to collect data from fathers than grandmothers. In order to holistically explore family roles and influences on maternal, child, and adolescent nutrition, a family systems approach is recommended (6, 23). Formative research is critical for designing contextually appropriate interventions. Resources are available to guide formative research using a family systems approach (40), to conduct a gender analysis (41, 42), and to use a participatory approach to intervention design and delivery (43).

Strengths and limitations

The strength of this study is that it documents programmatic experiences and perspectives from global health and nutrition professionals around the world, addressing a gap in the peer-reviewed literature. The diversity of respondents, in terms of sector, geographic location, responsibilities, and years of experience, is another strength. Survey questions were developed based on knowledge of the literature, the study team's programmatic experience, and reviewed by experts. However, as with any survey, the content of questions influences what information respondents shared. For example, only 1 respondent (based in the United States) described family engagement in child obesity prevention activities; however, the survey did not contain any questions directly addressing overweight and obesity or the dual burden of malnutrition. We included open-ended questions to allow respondents to share other learning and experiences that were not part of the survey. On the other hand, the length of the survey could have contributed to participant burden; responses in which ≥50% of questions were completed were included in the analysis to incorporate perspectives from those who did not complete the full survey. Respondents who had experience and interest in engaging family members could have been more motivated to complete the survey, which could lead to selection bias. Although multiple listservs were used to reach potential respondents, our selection of listservs might have contributed to recruitment bias. However, the geographic diversity in the sample suggests this might not be a strong limitation. Similarly, the survey and announcements were all in English, which might have limited participation. To reduce this risk, responses were accepted in any language; responses were submitted in French and Arabic. Finally, the focus of this study was to document the perspectives of global health professionals with experience engaging family members in nutrition activities; future research incorporating the perceptions of both global health professionals and program participants is needed to obtain a holistic understanding of program impact and to inform the development of future interventions.

Conclusion

Maternal, child, and adolescent nutrition programs and research are increasingly engaging family members in activities and interventions. The frequency and geographic distribution of responses to this survey affirm the widespread interest in engaging family members in nutrition activities. These survey findings highlight the importance of conducting formative research with all members of the family system, using participatory processes both in the design and implementation of interventions, and the potential for interventions that engage family members to increase community ownership. Additional research is needed to identify effective approaches to engaging family members to improve adolescent nutrition, because limited examples were identified in the peer-reviewed literature and in this survey. Lessons learned from programmatic experiences, alongside the peer-reviewed literature, can inform the design, implementation, and monitoring of future interventions.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank the survey respondents for taking the time to complete the survey and sharing their experiences with us. We appreciate the substantial contributions from Lisa Sherburne (USAID Advancing Nutrition), feedback we received from USAID Advancing Nutrition staff who pretested the survey, Catherine Kirk, Jennifer Burns, Andrew Cunningham, Amelia Giancarlo, and Altrena Mukuria, and the comments from Laura Itzkowitz (USAID Bureau for Global Health), who reviewed an earlier draft of the manuscript.

The authors’ responsibilities were as follows—SLM, KL, CML: designed research; CML, SLM, MS, BW: conducted research; CML, HCC, BW, MS, SLM: analyzed data; CML, SLM, HCC: drafted the manuscript; KL, BW, MS, KLD: reviewed and edited the manuscript; SLM, CML: had primary responsibility for final content; and all authors: read and approved the final manuscript.

Notes

The United States Agency for International Development (USAID) provided financial support for this activity through its flagship multisectoral nutrition project, USAID Advancing Nutrition. It was prepared under the terms of contract 7200AA18C00070 awarded to JSI Research & Training Institute, Inc (JSI). SLM was partially supported by the National Institutes of Health, Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, Grant/Award Number: P2C HD050924. USAID had no restrictions regarding publication and had no role in the design, implementation, analysis, or interpretation of the data. JSI had no restrictions regarding publication. CML received support from the National Institutes of Health, National Research Service Award, Cardiometabolic Disease Training Grant, T32 HL129969.

Author disclosures: The authors report no conflicts of interest.

Supplemental Material, Supplemental Boxes 1–5, and Supplemental Tables 1–4 are available from the “Supplementary data” link in the online posting of the article and from the same link in the online table of contents at https://academic.oup.com/cdn/.

Abbreviations used: IYCF, infant and young child feeding; LMIC, low- and middle-income countries; NGO, nongovernmental organization; USAID, United States Agency for International Development; WASH, water, sanitation, and hygiene.

Contributor Information

Caitlin M Lowery, Email: clowery@unc.edu, Department of Nutrition, Gillings School of Public Health, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, NC, USA.

Hope C Craig, Master of Public Health Program, Population Medicine & Diagnostic Sciences, Cornell University, Ithaca, NY, USA.

Kate Litvin, USAID Advancing Nutrition, Arlington, VA, USA.

Katherine L Dickin, Master of Public Health Program, Population Medicine & Diagnostic Sciences, Cornell University, Ithaca, NY, USA; USAID Advancing Nutrition, Arlington, VA, USA.

Maggie Stein, Department of Nutrition, Gillings School of Public Health, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, NC, USA.

Beamlak Worku, Department of Nutrition, Gillings School of Public Health, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, NC, USA.

Stephanie L Martin, Department of Nutrition, Gillings School of Public Health, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, NC, USA; Carolina Population Center, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, NC, USA.

Data Availability

Data described in the manuscript, code book, and analytic code will be made available upon request [pending approval].

References

- 1. Christian P, Mullany LC, Hurley KM, Katz J, Black RE. Nutrition and maternal, neonatal, and child health. Semin Perinatol. 2015;39(5):361–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Prentice AM, Ward KA, Goldberg GR, Jarjou LM, Moore SE, Fulford AJ, Prentice A. Critical windows for nutritional interventions against stunting. Am J Clin Nutr. 2013;97(5):911–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Tomlinson M, Hunt X, Daelmans B, Rollins N, Ross D, Oberklaid F. Optimising child and adolescent health and development through an integrated ecological life course approach. BMJ. 2021;372:m4784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Victora CG, Christian P, Vidaletti LP, Gatica-Domínguez G, Menon P, Black RE. Revisiting maternal and child undernutrition in low-income and middle-income countries: variable progress towards an unfinished agenda. Lancet. 2021;397(10282):1388–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Baker J, Sanghvi T, Hajeebhoy N, Martin L, Lapping K. Using an evidence-based approach to design large-scale programs to improve infant and young child feeding. Food Nutr Bull. 2013;34(3 Suppl 2):S146–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Aubel J, Martin SL, Cunningham K. Introduction: a family systems approach to promote maternal, child and adolescent nutrition. Matern Child Nutr. 2021;17(S1):e13228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Aidam BA, MacDonald CA, Wee R, Simba J, Aubel J, Reinsma KR, Girard AW. An innovative grandmother-inclusive approach for addressing suboptimal infant and young child feeding practices in Sierra Leone. Curr Dev Nutr. 2020;4(12):nzaa174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Nguyen PH, Frongillo EA, Sanghvi T, Wable G, Mahmud Z, Tran LM, Aktar B, Afsana K, Alayon S, Ruel MTet al. . Engagement of husbands in a maternal nutrition program substantially contributed to greater intake of micronutrient supplements and dietary diversity during pregnancy: results of a cluster-randomized program evaluation in Bangladesh. J Nutr. 2018;148(8):1352–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Stewart CP, Iannotti L, Dewey KG, Michaelsen KF, Onyango AW. Contextualising complementary feeding in a broader framework for stunting prevention. Mater Child Nutr. 2013;9(Suppl 2):27–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Every Woman Every Child (EWEC) . Global strategy for women's, children's and adolescents’ health (2016–2030). New York: Every Woman Every Child;2015. [Google Scholar]

- 11. World Health Organization, United Nations Children's Fund, World Bank Group . Nurturing care for early childhood development: a framework for helping children survive and thrive to transform health and human potential. Geneva: World Health Organization;2018. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Contento IR, Williams SS, Michela JL, Franklin AB. Understanding the food choice process of adolescents in the context of family and friends. J Adolesc Health. 2006;38(5):575–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Neufeld LM, Andrade EB, Ballonoff Suleiman A, Barker M, Beal T, Blum LS, Demmler KM, Dogra S, Hardy-Johnson P, Lahiri Aet al. . Food choice in transition: adolescent autonomy, agency, and the food environment. Lancet. 2022;399:185–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Norris SA, Frongillo EA, Black MM, Dong Y, Fall C, Lampl M, Liese AD, Naguib M, Prentice A, Rochat Tet al. . Nutrition in adolescent growth and development. Lancet. 2022;399:172–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Boncyk M, Ambikapathi R, Mosha D, Matangi E, Galvin L, Jeong J, Sultan R, Kumalija E, Kajuna D, Kieffer MPet al. . Big sister, big brother: a mixed methods study on older siblings’ role in infant and young child feeding and care in rural Tanzania. Curr Dev Nutr. 2019;3(Suppl 1):nzz034 [Google Scholar]

- 16. Knight J, Grantham-McGregor S, Ismail S, Ashley D. A child-to-child programme in rural Jamaica. Child Care Health Dev. 1991;17(1):49–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Martin SL, McCann JK, Gascoigne E, Allotey D, Fundira D, Dickin KL. Engaging family members in maternal, infant and young child nutrition activities in low- and middle-income countries: a systematic scoping review. Matern Child Nutr. 2021;17(Suppl 1):e13158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Martin SL, McCann JK, Gascoigne E, Allotey D, Fundira D, Dickin KL. Mixed-methods systematic review of behavioral interventions in low- and middle-income countries to increase family support for maternal, infant, and young child nutrition during the first 1000 days. Curr Dev Nutr. 2020;4(6):nzaa085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Yourkavitch JM, Alvey JL, Prosnitz DM, Thomas JC. Engaging men to promote and support exclusive breastfeeding: a descriptive review of 28 projects in 20 low- and middle-income countries from 2003 to 2013. J Health Popul Nutr. 2017;36(1):43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Bentley ME, Johnson SL, Wasser H, Creed-Kanashiro H, Shroff M, Fernandez Rao S, Cunningham M. Formative research methods for designing culturally appropriate, integrated child nutrition and development interventions: an overview. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2014;1308(1):54–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Fabrizio CS, van Liere M, Pelto G. Identifying determinants of effective complementary feeding behaviour change interventions in developing countries. Matern Child Nutr. 2014;10(4):575–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Cunningham K, Nagle D, Gupta P, Adhikari RP, Singh S. Associations between parents' exposure to a multisectoral programme and infant and young child feeding practices in Nepal. Matern Child Nutr. 2021;17(Suppl 1):e13143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. MacDonald CA, Aubel J, Aidam BA, Girard AW. Grandmothers as change agents: developing a culturally appropriate program to improve maternal and child nutrition in Sierra Leone. Curr Dev Nutr. 2020;4(1):nzz141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Tariqujjaman M, Rahman M, Luies SK, Karmakar G, Ahmed T, Sarma H. Unintended consequences of programmatic changes to infant and young child feeding practices in Bangladesh. Mater Child Nutr. 2021;17(2):e13077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ganle JK, Dery I, Manu AA, Obeng B. ‘If I go with him, I can't talk with other women’: understanding women's resistance to, and acceptance of, men's involvement in maternal and child healthcare in northern Ghana. Soc Sci Med. 2016;166:195–204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Ickes SB, Craig C, Heidkamp RA. How do nutrition professionals working in low-income countries perceive and prioritize actions to prevent wasting? A mixed-methods study. Matern Child Nutr. 2020;16(4):e13035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Pelto GH, Martin SL, Van Liere M, Fabrizio CS. The scope and practice of behaviour change communication to improve infant and young child feeding in low- and middle-income countries: results of a practitioner study in international development organizations. Matern Child Nutr. 2016;12(2):229–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Tadesse K, Zelenko O, Mulugeta A, Gallegos D. Effectiveness of breastfeeding interventions delivered to fathers in low- and middle-income countries: a systematic review. Matern Child Nutr. 2018;14(4):e12612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Negin J, Coffman J, Vizintin P, Raynes-Greenow C. The influence of grandmothers on breastfeeding rates: a systematic review. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2016;16(1):91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Lassi ZS, Moin A, Das JK, Salam RA, Bhutta ZA. Systematic review on evidence-based adolescent nutrition interventions. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2017;1393(1):34–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Salam RA, Hooda M, Das JK, Arshad A, Lassi ZS, Middleton P, Bhutta ZA. Interventions to improve adolescent nutrition: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Adolesc Health. 2016;59(4):S29–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Meiklejohn S, Ryan L, Palermo C. A systematic review of the impact of multi-strategy nutrition education programs on health and nutrition of adolescents. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2016;48(9):631–646.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Prost A, Colbourn T, Seward N, Azad K, Coomarasamy A, Copas A, Houweling TAJ, Fottrell E, Kuddus A, Lewycka Set al. . Women's groups practising participatory learning and action to improve maternal and newborn health in low-resource settings: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2013;381(9879):1736–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Marston C, Hinton R, Kean S, Baral S, Ahuja A, Costello A, Portela A. Community participation for transformative action on women's, children's and adolescents' health. Bull World Health Organ. 2016;94(5):376–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Gram L, Fitchett A, Ashraf A, Daruwalla N, Osrin D. Promoting women's and children's health through community groups in low-income and middle-income countries: a mixed-methods systematic review of mechanisms, enablers and barriers. BMJ Glob Health. 2019;4(6):e001972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Satzinger F, Bezner Kerr R, Shumba L. Intergenerational participatory discussion groups foster knowledge exchange to improve child nutrition and food security in northern Malawi. Ecol Food Nutr. 2009;48(5):369–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Dickin KL, Litvin K, McCann JK, Coleman FM. Exploring the influence of social norms on complementary feeding: a scoping review of observational, intervention, and effectiveness studies. Curr Dev Nutr. 2021;5(2):nzab001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Rogers E. Diffusion of innovations. 5th ed.New York: Free Press;2003. [Google Scholar]

- 39. Pulerwitz JGA, Betron M, Shattuck Don behalf of the Male Engagement Task Force, USAID Interagency Gender Working Group (IGWG) . Do's and don'ts for engaging men & boys. Washington (DC): IGWG;2019. [Google Scholar]

- 40. Aubel J, Rychtarik A. Focus on families and culture: a guide for conducting a participatory assessment on maternal and child nutrition. The Grandmother Project, TOPS, USAID;2015.

- 41. USAID Advancing Nutrition . Program guidance: engaging family members in improving maternal and child nutrition. Arlington (VA): USAID Advancing Nutrition;2020. [Google Scholar]

- 42. Jhpiego . Gender analysis toolkit for health systems [Internet]. Baltimore: Jhpiego;2016. Available from: https://gender.jhpiego.org/analysistoolkit/. [Google Scholar]

- 43. Bezner Kerr R, Young SL, Young C, Santoso MV, Magalasi M, Entz M, Lupafya E, Dakishoni L, Morrone V, Wolfe Det al. . Farming for change: developing a participatory curriculum on agroecology, nutrition, climate change and social equity in Malawi and Tanzania. Agric Human Values. 2019;36(3):549–66. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data described in the manuscript, code book, and analytic code will be made available upon request [pending approval].