Abstract

Background

Trans Vaginal Mesh (TVM) surgeries have been used to treat stress urine incontinency (SUI) and/or pelvic organ prolapse (POP). Systematic reviews of clinical studies of outcomes suggest that the procedures have benefited a majority of women, while noting that a small minority of women have experienced harms. To provide a more complete picture of outcomes, we conducted a systematic review of the qualitative literature to provide a comprehensive analysis of women’s own accounts of their experience.

Method

We conducted a systematic review and thematic synthesis of the evidence from the international qualitative literature on women’s experiences of and perspectives on TVM surgery for SUI and/or POP between 1996 and 2020. We retrieved 6587 papers from PubMed, Cochrane, CINAHL, PsycINFO, Scopus, and Sociological Abstracts. After application of inclusion and exclusion criteria and full-text review of eligible articles, five articles were included in our systematic review.

Results

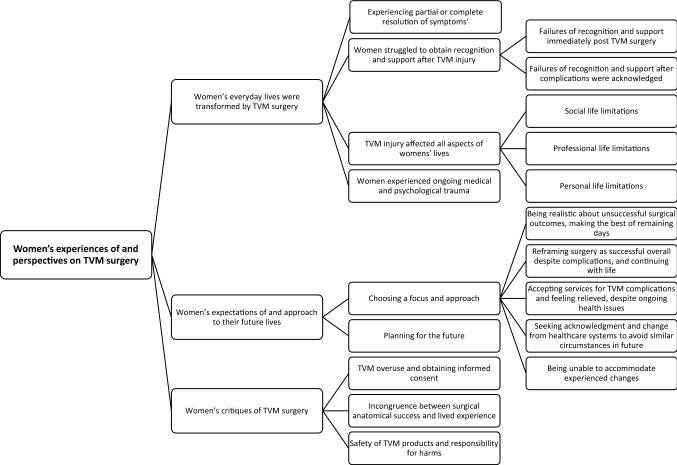

Findings from included articles were organised under three main themes: women’s everyday lives were transformed by TVM surgery; women’s expectations of and approach to their future lives; and women’s critiques of TVM surgery. The transformation of women’s everyday lives included a struggle to obtain recognition and support for their injuries before and after corrective surgery, ongoing limitations on their social, professional and personal lives, and compounding medical and psychological trauma as a result. Women’s approaches to their future lives changed because of this transformation; we identified five main approaches, four were ways of accommodating change, a fifth involved being unable to accommodate life changes. Women’s critiques included that TVM surgeries were overused, consent processes were poor, and surgeons’ definitions of success were deficient. Women expressed concerns about the safety of TVM products and future risks of further complications and discussed multiple system failures in the health care they received.

Conclusion

This review suggests that discounting women’s experiences has caused compound trauma and skewed the clinical evidence base; while harms occurred in a minority of women, we suggest they should be recognised as an ethically significant potential outcome. Approaches to TVM injury should attend to historical epistemic injustice and recognise women’s agency.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s40271-021-00547-7.

Key Points for Decision Makers

| Low-rate severe adverse events should be recognised as an ethically significant potential outcome of innovation in surgery. |

| Addressing epistemic injustice (a pattern of ignoring, or being unable to understand, the testimony of patients) is a key ethical challenge for evaluating the use of surgical innovations such as transvaginal mesh (TVM). |

| Women should be acknowledged as knowledge holders and agents in their experience of TVM surgery. |

Introduction

The first transvaginal mesh (TVM) device was approved by the USA Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 1996 for use in minimally invasive surgical treatment of stress urine incontinency (SUI) [1, 2]. Despite the rise of the evidence-based surgery movement in the 1990s [3], recent studies reveal there was no published clinical trials supporting the safety and efficacy of these devices at the time of first FDA approval [1]. Nonetheless, this initial FDA approval proved highly consequential, as it permitted a cascade of TVM products to be approved using ‘substantial equivalence’, for treatment of both SUI and pelvic organ prolapse (POP) [1, 2, 4].

As TVM surgery was scaled up, stories began to emerge of women experiencing post-surgical harms and complications [4]. However, these negative outcomes tended to be de-emphasised or were not reported in early trials. There are two known causes for this failure to report or adequately represent low-incidence adverse events (even when severe):

The incongruence between efficacy and effectiveness [5].

The methodological limitations in clinical trials [1].

Clinical trial evaluations of surgical treatments tend to focus on ‘objective’ and anatomical outcomes, and less on effectiveness, subjective outcomes and patient-reported outcomes [2, 5]. Uptake of innovations in surgery is highly dependent on evidence of their efficacy; however, there is a need for evidence of their effectiveness to understand their usefulness, safety and effects on populations and individuals’ lives [5].

Significant underreporting of harms and complications associated with TVM surgeries means that estimates of the number of women affected globally is based on extrapolation and assumptions [6]. However, by late 2017, over 100,000 women around the world have taken legal actions against manufacturers and providers involved in use of TVM devices [6], and there has been a continuous global increase in the prevalence and severity of reported adverse events [4, 6].

Since regulatory approval in 1996, a TVM trial literature has developed. Systematic reviews of this literature present data from quantitative measures of outcomes including subjective cure rates, symptoms and quality of life. For example, our search prior to this systematic review identified only two Cochrane reviews on use of TVM for SUI, published 21 years after introduction of TVM [7, 8]. These reviews focused on reporting comparative cure rates for different TVM procedures rather than reporting on harms and complications. Aggregated quantitative estimates of adverse events in TVM procedures were presented late in the reviews (sometimes as appendices); authors concluded that the rate of adverse events was low, and limited information was provided regarding severity. These quantitative measures also provide limited opportunity for women to explain outcomes from their own perspective, such that the detail of women’s experience was arguably lost in quantitative aggregation. To better understand and report on low-rate severe adverse events associated with TVM and its effects on women’s lives, we conducted a systematic review and thematic synthesis of the evidence from the international qualitative literature on women’s experiences of and perspectives on TVM surgery for SUI and/or POP between 1996 and 2020. This complements existing quantitative reviews by synthesising what is known from women’s own accounts of their experience.

Method

We used thematic synthesis for this qualitative systematic review to better understand women’s experiences of and perspectives on TVM surgeries. Thematic synthesis provides an opportunity to develop descriptive themes via coding primary studies ‘line by line’, then to use these descriptive themes as the basis for generation of analytic themes [9]. This analysis enabled us to generate new interpretive constructs that complement and are not covered by existing quantitative studies.

We searched PubMed, Cochrane, CINAHL, PsycINFO, Scopus, and Sociological Abstracts using a strategy designed to identify qualitative literature focusing on women’s experiences of and perspectives on TVM surgery for treatment of SUI, POP or both conditions. Our final search was conducted in September 2020. We conducted manual searches and pearling and screened the reference lists of included studies. The search strategy was guided and developed over several iterations and is available in Supplement 1 (see electronic supplementary material [ESM]).

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Two authors (MM and SC) independently identified English language articles and conducted title/abstract eligibility screening. We included qualitative studies reporting on use of TVM (all types of TVM products) for treatment of SUI, POP, or both SUI and POP. We included any studies comparing TVM surgery with other surgical methodologies in these conditions.

We excluded studies using only standardised quantitative instruments to measure outcomes, as these have already been included in systematic reviews of the quantitative literature. We included all qualitative and mixed method reporting on TVM procedures outcomes from patients’ perspective and in their own words, including women’s stories and experiences and their accounts of outcomes, including cure rates, harms and complications. We included studies based on the methodology used, regardless of whether they reported positive or negative surgical outcomes. We excluded studies focusing on use of mesh products for abdominal surgeries and hernia repair surgeries, and studies on non-human animals. Studies on mixed SUI with other medical conditions such as urge incontinency or autoimmune diseases, or use of TVM for secondary repair surgery (following failure of other surgical methods), were excluded.

Appraising the Methodological Limitations in Included Studies and Confidence in Synthesis Findings

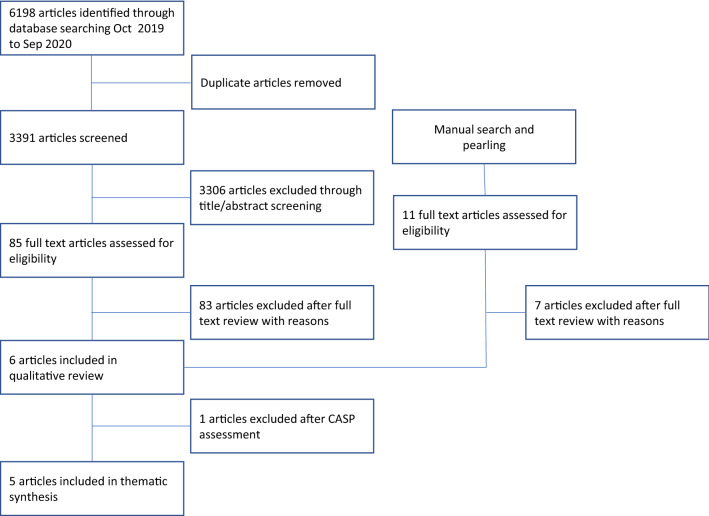

All included studies were assessed using the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) tool [10] by two authors (MM and SC), independently, to assess reliability, validity and usefulness. Any differences in assessment were resolved by discussion (Fig. 1). To ensure confidence in individual descriptive findings and emerging themes, the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation—Confidence in Evidence from Reviews of Qualitative research (GRADE-CERQual) [11] approach was used by two authors (MM and SC) to assess the included studies. Further details about the CASP and GRADE-CERQual procedures are available in Supplement 2 (see ESM).

Fig. 1.

PRISMA flow diagram

Data Extraction and Synthesis

Full texts of eligible studies were examined independently by two authors (MM and SC). Papers were extracted in full into NVivo 12 software for data management and were initially coded line by line. After completion of coding, themes were synthesised by discussion between all three authors, over several iterations, to best present women’s perspectives on TVM surgeries, resolve any uncertainties and ensure coherence and alignment with study objectives.

Results

Following CASP assessment, five articles published between 1996 and 2020 were found eligible [12–16]. One additional article was excluded in the CASP assessment phase due to the poor quality of the qualitative data and analysis. Two of the five included articles reported on one study: they were conducted by the same author, presented as a thesis and then a summary published article; the thesis contains more detailed findings [13, 14]. To avoid any confusion, when both thesis and article present the same finding, only the article [14] is cited as a reference in this review; when the thesis presents unique findings, the thesis is cited [13]. All included studies had positive evaluation of all quality criteria and they mostly included high quality analysis. Although one study [13, 14] had a small sample, its methodology was coherent and the quality of analysis was high. In GRADE-CERQual assessment, mostly we had no or very minor concerns regarding methodological limitations, relevance, coherence, and adequacy of provided evidence. Details of the included studies are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Description of included articles and their participants

| Study | Number of participants Methods for recruitment of participants |

Location of study | Inclusion criteria and focus of study | Timeframes | Analysis method |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bramwell and Sullivan (2019) [12] |

23 participants Recruited women via a mesh support Facebook group Women’s written narratives collected via emails |

New Zealand | Focused on the experiences of women affected by the implantation of surgical mesh |

Report submitted in April 2019 The mean length of time participants had lived with surgical mesh was 9 years |

Braun and Clarke’s method for thematic analysis |

| Brown (2019) (thesis) [13] |

7 participants Used modified standardised questionnaire and qualitative interview |

New Zealand | Women who have experienced TVM complications |

Research started January 2018 Women had TVM surgeries in 2002, 2006, 2008 (3 pts), 2010 and 2014 |

Van Manen’s hermeneutic phenomenological method was used |

| Brown (2020) (published article) [14] |

7 participants Used modified standardised questionnaire and qualitative interview |

New Zealand | Women who have experienced TVM complications |

Research started January 2018 Women had TVM surgeries in 2002, 2006, 2008 (3 pts), 2010 and 2014 |

Van Manen’s hermeneutic phenomenological method was used |

| Dunn et al. (2014) [15] |

84 participants Phone interview using 2 open-ended questions Sufficient data was collected from 51 for one question and 71 for the other question |

USA | Women who have had TVM as primary surgery and experienced complications |

Study conducted from January 2006 to December 2011 The mean length of time from the index surgery to the study was 4.5 years |

The collected data was analysed using qualitative description with low-inference interpretation to provide a straightforward, unadorned description of women’s experiences of mesh complications |

| Izett-Kay et al. (2020) [16] | 752 participants among 1766 recruited participants answered a free-text response component of a questionnaire on paper, online or in a telephone interview | UK | All women who have had TVM implants for primary surgery |

Study published in 2020 Women had surgeries between 2010 and 2018. The median length of time from surgery to response was 46 months |

Braun and Clarke’s method for thematic analysis |

TVM transvaginal mesh

All included articles reported on interviews with women who had experienced harm from TVM; one [16] also included women who benefited from TVM surgery. Overall, 866 women were included in these studies. The numbers of women in individual studies ranged widely: 7 [13, 14], 23 [12], 84 [15] and 752 [16], respectively.

Distribution of emerging themes in contributing studies and supporting quotes for emerging themes from contributing studies are available in Supplement 3 (see ESM) (Fig. 1).

Our synthesis is organised into three central themes (Fig. 2):

Women’s everyday lives were transformed by TVM surgery.

Women’s expectations of and approach to their future lives.

Women’s critiques of TVM surgery.

Fig. 2.

Women’s experiences of and perspectives on TVM surgery for SUI and POP, between 1996 and 2020. POP pelvic organ prolapse, SUI stress urine incontinency, TVM transvaginal mesh

Women’s Everyday Lives Were Transformed By TVM Surgery

All included studies reported that women’s everyday lives had been transformed by TVM surgery, but for most this was not positive. Negative impacts included difficulties in finding support and recognition for their experienced symptoms, severe adverse effects on their social, professional and personal lives, and ongoing compounded medical and psychological trauma arising from these experiences (Fig. 2).

Experiencing Partial or Complete Resolution of Symptoms

A small portion of women in one study expressed how the advantage of partial or complete symptom resolution following TVM surgery improved their quality of life and overall their physical and psychological health status [16]. Some of these women appeared satisfied with their treatment and the improvement in their quality of life [16]. However, some women, despite improvements in their quality of life, did not recognise their surgical outcomes as a complete resolution for their symptoms and deliberately discussed other experienced changes in their physical and psychological health status after TVM surgeries rather than improvement of their quality of life [16].

Women Struggled to Obtain Recognition and Support After TVM Injury

The predominant theme from all five studies was women’s struggle to obtain recognition of their post-surgical injuries, and support to address those injuries [12, 14–16]. This failure of recognition was so significant that women’s challenges can be conceptualised on a timeline, with a bright line between the period before and after complications were acknowledged by health care providers.

Failures of Recognition and Support Immediately After TVM Surgery

All included studies reported that TVM-injured women experienced a long, sometimes catastrophic recovery period, which pre-operation advice had not prepared them to expect [12, 14–16]. Women reported that from immediately post-procedure onwards, they struggled to have their symptoms recognised and to receive support [14–16]. Women’s descriptions of how they felt as a result included words such as humiliated, ashamed, unheard, isolated, demoralised, demeaned, depressed, hopeless and disappointed [12, 13].

Women reported that even when health care providers conducted physical examinations that revealed evidence of TVM complications, these providers generally did not recognise or acknowledge women’s pain and other symptoms, or their suffering [12, 14]. Rather than accepting TVM as the cause, women’s reported symptoms were attributed to depression, hypochondria, prescription drug- and attention-seeking, and other psychogenic origins, and women’s own causal accounts were dismissed [12, 14]. Conversely, if symptoms were recognised as legitimate, women were treated as a very rare case of complications [13]. Some women reported similar lack of acknowledgement and understanding from their children and other family members, who perceived them to be making excuses to avoid activities, or intentionally self-isolating [12].

Similar experiences were reported in interactions with health insurance companies or compensation agencies.1 Coverage and payments were sometimes declined due to lack of evidence that the surgery had caused the symptoms, or when surgery was accepted as the cause and coverage was provided, women had to fight to have each new symptom covered [12, 13]. Women reported being required to attend multiple review sessions to discuss their experienced complications and share intimate details of their lives, and failure to adapt these processes to their impairments (e.g. being required to attend in person while the other parties attended virtually) [13].

Failures of Recognition and Support After Complications Were Acknowledged

Four included studies reported on interviews with some women who had eventually experienced recognition of their TVM complications [12, 14, 15]. Women reported that a benefit of medically authorised recognition was that it prompted greater support and acknowledgment from their family members [13]. However, it did not always improve their health care experience, further reducing women’s trust in the health care system [13].

If removal of the implant was undertaken, women reported again receiving inadequate explanation of follow-up interventions, including failure to inform about risks and complications, and repeated refusal to recognise ongoing symptoms after repair surgery [13]. Women described their subsequent feelings using words such as betrayed, let down and abandoned, and believed the truth was being hidden and further treatment and investigations unfairly refused [13]. If told cure of their symptoms was impossible, these feelings intensified, and women reported feeling even more isolated and incapacitated [14, 15]. Women reported ongoing difficulties with insurance companies and/or accident compensation agencies, including selective acceptance and decline of coverage for certain symptoms, inconsistent support for injured women’s ongoing services, or under-funding of required treatments, leaving women with incomplete procedures; for example, funding a first procedure and declining funding for further procedures recommended to control symptoms [12, 14].

TVM Injury Affected All Aspects of Women’s Lives

In addition to the medical issues described above, women in all included studies also described profound effects on other aspects of their social, professional and personal lives, due to severe, permanent disabilities; these were described as ‘cascading disabilities’ because they continued to emerge, and were related in complex ways [12, 14–16].

Social Life Limitations

Limited mobility and inability to travel around, to participate in social events, to pursue recreational activities and to maintain social relationships separated women from their previous active daily lives [12, 14, 15]. Women described their feelings about the resulting restriction and physical isolation using words such as frustrated, devastated and miserable [12, 14, 15]. In addition to this physical distance from their previous social lives, women described “suffering in silence” [14]. This arose from (1) social awkwardness in discussing reproductive anatomy and function; (2) challenges discussing profound suffering with others; and (3) women’s fear of rejection, judgment or stigma if they revealed their disabilities to the community [14]. It often took many years for women to find support groups, initiated by other TVM-affected women, to discuss their suffering in a safe environment and find sympathy from other women with similar experiences without fear of judgment or stigmatisation [14].

Professional Life Limitations

The physical impairment, ongoing medical issues, and multiple surgeries women experienced had profound effects on their professional lives. Women described reducing their working hours, taking extensive sick leave, leaving their professional roles or continuing in their professional roles only with extensive modifications to their daily routines [12, 13]. Many women experienced grief and psychological burdens from early retirement on medical grounds, role loss and/or reduced financial resources [12, 13]. Women’s life goals radically shifted from ambitious professional achievements to simply being able to stand, move within the radius of their homes and toilets, or complete limited home-based tasks [12, 13].

Personal Life Limitations

TVM complications had devastating impacts on women’s relationships with their immediate families. Their impairments prevented them from playing their role as a person, a partner, and a parent [12, 14, 15]. Women experienced different symptoms and functional effects (e.g. ability to sleep, sit, walk, stand and remain standing), with different effects on activities of daily living [12, 14, 15]. While most studies discussed women’s impairment in general terms [12, 14, 15], one study identified chronic pain as most significant in women’s evaluation of whether their surgery had an acceptable outcome [16]. This study reported that some women with ongoing pelvic floor dysfunction but no chronic pain after TVM surgery reported improved quality of life post-surgery [16]. However, most women participating in the included studies reported a dramatic decrease in the quality of their own lives [12, 14–16], and their families lives [12, 14]. These women highlighted their need to be always aware of how far they are from a toilet, and a frequent need to lie horizontally, greatly affecting their daily routine [12, 14]. Women’s intimate relationships were also limited or completely stopped due to severe pain, scarring, and their partners’ laceration and injuries due to contacting eroded TVM devices during intimacy [12, 13]. Consequently, intimate partner relationships became carer/patient relationships [12, 14, 15]. Women also reported relationship impacts of imposed infertility due to hysterectomy following TVM complications [13].

Women’s loss of roles, independence, and ability to care for others led to feelings of guilt and frustration [12, 14, 15]. Their inability to contribute financially or participate in family events caused embarrassment and tension in relationships [12, 14], and led women to feel like a burden to their families [12, 14, 15].

Women Experienced Ongoing Compound Medical and Psychological Trauma

In addition to the primary effects described above, women described secondary emotional distress and mental health issues in all included articles [12, 14–16]. These issues were barriers to further treatment-seeking [14–16], and included severe psychological effects, such as post-traumatic stress disorders diagnosed in two of seven women in Brown’s study [14]. We describe this as compound medical and psychological trauma because the secondary psychological issues due to experiencing TVM-associated complications had considerable impact on how women were experiencing the TVM-associated complications and interfered with their received services. These compound mental health issues arose partly from the losses described above, and partly because of social stigmatisation. This stigmatisation separated women even more from their social lives. They described their feelings using words such as: self-conscious, embarrassed, self-blame, guilt, frustrated, depression, “unnaturalness” and shame, were reluctant to seek care, and sometimes admitted having suicidal thoughts [12, 15].

Some women reported anxiety in planning any activities, basic housework or traveling even for short distances from home/toilet [12, 14]. Women also reported increased vigilance, always watching for health changes, worrying about further cascading health problems, and experiencing stress whenever a new symptom was experienced, fearing it was related to their TVM implants [15]. Women who had not had TVM complications also reported feeling anxiety and stress about the possibility of developing complications in the future [16].

Women’s Expectations of and Approach to Their Future Lives

Included studies often discussed with women their perception of their future lives and how they were planning to approach the time ahead.

Choosing a Focus and Approach

Women in the included studies who had experienced TVM complications were all forced to adjust to a “new normal”. However, across the studies, we identified five ways that women faced the required changes in their lives, each entailing a different focus and approach (Fig. 2) [12, 14–16].

Being Realistic About Unsuccessful Surgical Outcomes, Making the Best of Remaining Days

Some women moved their focus away from the emotional and physical challenges they faced, and onto building their future lives, making plans one day at a time dependent on their abilities that day [14, 15]. This required accepting that TVM had been unsuccessful and caused harms, and planning to make the best of their lives [13].

Reframing Surgery as Successful Overall Despite Complications, and Continuing With Life

Some women were able to consider their surgery a success, despite TVM implant complications, by reasoning that the complications were not worse than their original symptoms of SUI or/and POP [12, 15, 16]. These women were able to accept radical changes in their lives and consider themselves satisfied with the overall result [12, 15, 16].

Accepting Services for TVM Complications and Feeling Relieved, Despite Ongoing Health Issues

For some women, being given treatment for TVM complications, even if not completely successful, provided relief and made it possible to adjust to altered expectations and plans for their life [12, 15].

Seeking Acknowledgment and Change From Health Care Systems to Avoid Similar Circumstances in Future

Women in one study focused on seeking acknowledgment and change from health care systems, to prevent other women from being harmed in the same way [14]. It was not clear from the report how this altered women’s experience of their lives.

Being Unable to Accommodate Experienced Changes

The four positions above required acceptance of limitations on capabilities [12, 14]. In two studies, a proportion of women reported not being able to accept what had occurred. These women reported experiencing suicidal thoughts, and wishing for their end of life [12, 14].

Planning for the Future

Participants in the included studies reported changed expectations of their future lives [12, 13]. For some women, planning for the future became almost impossible, as their limited physical capabilities constrained available opportunities [13], and cascading compounded health problems created significant uncertainty [12, 14, 15]. This radical reconfiguration of future lives also influenced and constrained the future plans of their family and friends [13].

Women’s Critiques of TVM Surgery

All included articles provided women’s critical perspectives on the use of TVM products for treatment of their conditions [12, 14–16]. There were three main critiques, outlined below.

TVM Overuse and Obtaining Informed Consent

In all included articles, women retrospectively questioned whether TVM surgery had been the best surgical treatment option [12, 14–16], and argued that they should have been better informed of potential adverse events, including life-threatening complications, and alternative treatments [12, 14, 16]. They considered their surgeon responsible for failures to fully inform, or for giving them false assurance that the procedure was supported by evidence, effective and safe [12, 13, 16]. Women reported that the expertise imbalance between patient and surgeon meant they felt powerless and forced them to trust their surgeon and accept the offered solutions irrespective of the severity of their symptoms [13]. Women also reported not being told how to seek help should a complication arise [16].

Incongruence Between Surgical Anatomical Success and Lived Experience

All included studies revealed a significant disparity between surgeons’ and women’s perspectives on surgical outcomes [12, 14–16]. Women expressed frustration that their knowledge of their own body had been discounted, worsening their physical and psychological outcomes [12, 13].

As discussed above, surgeons at least initially held that all surgeries had been successful [12, 14–16]. One study suggested this was because surgeons defined success as restoring the true anatomical position of all organs in the pelvis [13]. Surgeons thus rejected women’s accounts because they did not believe such symptoms were possible when an anatomically correct outcome had been achieved. Women were consequently not offered a thorough investigation to identify medical reasons for their symptoms [12, 14].

Similar problems occurred after women had corrective surgery to address complications. For technical reasons (due to the location, and the nature of TMV devices), the surgical location is difficult to visualise (e.g. radiologically). Women who underwent corrective surgery, but then experienced further symptoms and complications, reported that because no device remnants could be seen on imaging, this commenced a new cycle of lack of recognition and support, in which women’s symptoms were ascribed to psychogenic origins [14].

Safety of TVM Products and Responsibility for Harms

Concerns about the safety of TVM products and future risks of further complications were expressed by women with and without complications, in all included studies [12, 14–16]. Women argued that they would not have assented to surgery if they had understood the potential and extent of adverse events [14–16], and wanted to warn other women against assenting to TVM surgeries in future [13, 15]. While surgeons were considered responsible for failures to fully inform in all studies [12, 14–16], in one study women argued that companies, organisations and individuals who developed and regulated TVM products should also be held accountable for harms [16].

Discussion

Systematic reviews of clinical studies of outcomes from TVM surgeries for treatment of SUI and/or POP suggest that the procedures have benefited a majority of women, while noting that a small minority of women have experienced harms [2]. This systematic review of the qualitative literature provides an important complement and corrective to that clinical literature. Women’s stories and explanations revealed how their everyday lives were transformed after TVM surgery, as well as their struggle to obtain recognition and support for their injuries. The experienced ongoing medical and psychological trauma from these events changed TVM-injured women’s expectations of and approach to their future lives. While these harms may have occurred in a minority of women, their severity and far-reaching effects suggest that they should be recognised as an ethically significant potential outcome of TVM surgery.

One available framework for considering the potential ethical challenges in the use of surgical innovations is that proposed by Johnson and Rogers [17]. They developed a typology of ethical challenges in four groups: patient harm, informed consent, distribution of health care resources, and conflicts of interest [17]. We note that distribution of health care resources and conflicts of interest were not raised in the primary studies we analysed. This does not disconfirm these issues as ethical challenges but suggests they may not be central to women’s accounts of how they were wronged by TVM surgery. The first two categories however—patient harm and informed consent—were central themes for women, corroborating those elements of Johnson and Rogers’ typology, and we will consider these two themes first. We will then propose that epistemic injustice should be added to the list of ethical concerns and conclude with a discussion of the need to recognise women both as knowledge holders and agents in their health care experience.

Informed Consent

A fundamental principle of medical ethics and law is the need to obtain valid consent from patients before undertaking a procedure [18]. Obtaining valid consent in innovative surgeries can be compromised as a result of several problems. Variations in the definition of innovation in surgery mean that clinicians may not be transparent about innovation during consent processes [19, 20]. Lack of evidence about the risks and benefits of innovative procedures, especially in the early stages of innovation [17], mean that these cannot be disclosed. Finally, there is a tendency to believe that innovation is intrinsically advantageous, that it offers increased benefit or quality of outcomes simply because it is innovative [17].

The quality of the informed consent process is as important as obtaining it [18]. Patients’ knowledge, their understanding of given consent and their perception of consenting free from coercion are central principles in bioethics [18].

TVM-injured women describe failures to be informed of potentially life-threatening associated complications, and/or false assurance that the TVM procedure was established, well evidenced, and the best and safest option for them [14–16]. Such withholding of information, or provision of inaccurate or incomplete information, is not justifiable in the context of consent for planned surgeries [17].

Patient Harm

Surgical treatment, because it involves cutting and altering the body, inevitably entails some harms, as well as increased risk of mortality and morbidity [17]. Harms can include physical harms to the patient from surgery itself, as well as risks of harm after surgery arising from, for example, infection, anaesthesia or length of hospitalisation [17]. Particularly in the context of surgical innovation, a lack of knowledge about safety and efficacy may increase the potential for patient harm in comparison with better established surgeries [17]. Patients and their families can face harms in other domains, including imposed financial burden and psychological hardship [17].

Surgery—including innovative surgery—is offered and accepted on the basis that any harms experienced will be outweighed by the benefits of the procedure. Primary studies included in this review offered participants’ stories of harms experienced. Bringing these accounts together allowed development of a typology of how these harms affected women after TVM surgery—they limited women’s social, professional and personal lives. In addition, this review connects women’s experience of harm to their treatment in health care systems. Relevant harms were not just those caused by the surgery itself. Rather, medical and psychological trauma were compounded by health system failures and injustice. We turn to these issues now.

Epistemic Injustice

We propose that epistemic injustice is both a harm in itself for TVM-affected women and is a mechanism for exacerbating the physical and psychological harms experienced as a result of TVM surgery. Epistemic injustice occurs when a person’s contribution to the production of knowledge is unrecognised or unjustly excluded, dismissed, or relegated to a lower status [21]. One influential theorist of epistemic injustice, Miranda Fricker, distinguishes between testimonial epistemic injustice and hermeneutic epistemic injustice [21]. Testimonial injustice occurs when ones’ testimony is wrongly deflated by the hearer’s prejudice or judgment, to a degree that blocks the flow of knowledge produced by the speaker [21]. Hermeneutic injustice occurs when a speaker’s powerlessness, and a lack of relevant interpretive resources in their community, hinders them from making sense of their social experiences in a social group [21]. In other words, the speaker’s lived experience and produced knowledge are unfairly dismissed due to a structurally prejudiced social gap, such that others dismiss them as knowers, and/or are unable to make sense of what they are experiencing.

The significance of epistemic injustice in TVM surgery is supported by several of our themes and subthemes:

Incongruence between surgical anatomical success and lived experience.

Failures of recognition and support immediately after TVM surgery.

Failures of recognition and support after complications were acknowledged.

Ongoing and compounding medical and psychological trauma.

Drawing on these themes, we propose an overarching explanation for this aspect of women’s experience. Women’s experience was epistemologically incongruent with their surgeon’s understandings of success and outcomes. This meant that both after initial surgery, and after complications were acknowledged, women did not receive recognition of harms, or support to rectify these harms. The inability of surgeons to recognise women’s suffering constituted both hermeneutic and testimonial injustice.

The evidentiary environment of TVM devices laid the ground for this epistemic injustice. TVM devices were approved for a median of 5 years before primary clinical trials were published to determine whether there was a favourable benefit-to-harm balance [1]. These clinical trials, when published, emphasised the efficacy of TVM surgeries via quantitative evidence such as scored symptoms, laboratory test results, period of treatment and associated mortality rates [5]. This stimulated extensive marketing and uptake in practice [1]. Not considering evidence of effectiveness, quality of life and patient satisfaction in assessment of surgical innovations [5] laid the ground for a prejudicial environment, which we argue enabled hermeneutic injustice. The lived experience of TVM-associated complications went unheard and were accounted as having no value in assessment of TVM surgeries; they remained unavailable to the surgical community as they made sense of TVM procedures. It is well established that qualitative methods can provide insights that are not able to be derived via quantitative methods [22]. Given this, and especially in situations such as this where epistemic injustice is an issue, it seems important to ensure that research on the topic includes qualitative engagement with affected persons.

Not only were patients’ lived experiences neglected in assessment of TVM surgery’s effectiveness, patients’ testimony and participation in knowledge formation was incessantly dismissed and considered not as important as their physicians’ views. This clearly constitutes a form of testimonial injustice, which harmed women in compounding ways. It is important to recognise that this procedure was gender-specific innovative surgery. Gender essentialism and underrepresentation of women in clinical research has a long history that significantly exposes women to disproportionate harm [23]; an issue also often neglected in debates about the ethics of surgical innovations.

Women’s experience of epistemic injustice was the main mechanism for the compounding of their medical and psychological trauma. The failure of the health care system to provide women with just health care services was primarily caused by a recurring pattern of miscommunication between women and health care professionals. These communication gaps occurred before and after TVM surgery [12, 14–16], including,

failure to obtain informed consent,

failure to acknowledge complications associated with TVM surgery,

failure to provide appropriate investigation and treatment for women’s continuous experienced symptoms [12, 14],

if symptoms were recognised as legitimate, treating women as a very rare case of complication or leaving them with incomplete procedures [12, 14].

Experiences of the epistemic injustice encoded in how the health system evaluated post-surgical outcomes had significant consequences for TVM-injured women. The majority lost their trust in the capacity of health care to address their pain and suffering [13]. Many women stopped seeking further treatment, effectively exiting the health care system that had first caused and then failed to recognise the harms [14–16], to “suffer in silence” [14].

Recognising Women’s Agency

Patients’ knowledge and understanding of their own health conditions are rarely recognised by health professionals and are often marginalised in knowledge formation [24]. The five different approaches taken by TVM-injured women highlighted how women can have agency in the situation of their health care. Based on this review, we propose that recognition, support and respect for this agency may have ethical value in its own right but may also offer a practical strategy to promote epistemic justice in health care delivery. In providing this recognition and respect for women’s agency in TVM surgery, it is important to understand the diversity of lived experiences and values revealed by this review, as these generate different expectations of and responses to the required adjustment to the “new normal” and planning for future. Despite this diversity, women who received some support and acknowledgement in their journeys were able to have some level of acceptance of caused harms and were more successful in adjusting and shaping their present and future lives with their current condition. This analysis also highlights that some women were not able to accommodate experienced changes in their lives and developed suicidal thoughts, suggesting a subset of TVM-affected women will need ongoing and intensive support [12, 14].

Strength and Limitations

This synthesis was limited by the small number of qualitative studies representing women’s voices regarding their experiences of and perspectives on TVM procedures; however, our extensive searching and inclusion/exclusion procedures suggests we have included all available research within our chosen time period. As with all research, the available studies have inherent methodological limitations including the potential for response bias, and social and cultural barriers to expression of concerns about gender-specific health issues. Our use of structured evaluation tools was designed to minimise this to the extent possible.

The inclusion/exclusion criteria were chosen to ensure we were including studies where the outcomes women described were clearly a result of TVM surgery. While TVM use in mixed conditions, and secondary use, are important clinical contexts, they also make it more difficult to draw conclusions about the impact of TVM surgery. For example, in women who have experienced TVM procedures as a secondary repair, it is difficult to conclude whether or to what extent the TVM procedure, or the primary procedure, is the cause of their experience. For this reason, we chose to exclude articles reporting on outcomes of TVM use for secondary repair surgery or mixed conditions. We did not record the number of articles excluded for this reason, which is a limitation. However we are confident that we have captured all relevant studies published before our cut-off date where TVM surgery was the primary procedure.

After our cut-off date for inclusion, Uberoi et al. [25] published their primary qualitative study of 19 women who had removal or revision of TVM for SUI. Uberoi and colleagues also emphasised the existence of numerous studies on surgical outcomes using standardised questionnaires and reporting broadly categorised quantitative data, as well as the limited number of qualitative studies on women’s experiences after TVM surgeries [25]. The findings of Uberoi et al. [25] were consistent with our review, as follows:

TVM surgery impacted multiple domains of women’s lives (sexual health, mental health, relationships and professional lives).

Women’s concerns were not appropriately acknowledged, and this strained patient–physician relationships.

Women reported experiencing inappropriate and inadequate pre-operative counselling to obtain true informed consent.

While this consistency suggests our findings are reliable, we note that Uberoi et al. interpretation of their findings had a stronger emphasis on the need for good patient–physician relationships [25], which was more implicit than explicit in the studies included in our systematic review.

Conclusion

This analysis of women’s stories suggests that experienced compound harms and failures of obtaining informed consent were important wrongs done in TVM surgery, affecting women in three main ways: by limiting their social, professional and personal lives. Although there was no evidence of women’s concerns about conflict of interest or misallocation of resources in our included studies, women have expressed their concerns about system failures in ensuring safety of delivered health care and ambiguity of who bears responsibility in health systems. Women considered clinicians responsible for failure to communicate possible adverse events before and after their surgeries [12, 14–16], and suggested that individuals, companies and organisations involved in development and regulation of TVM should be held accountable for associated harms [16].

We propose that two further ethically relevant considerations—epistemic injustice and the ethical importance of recognising women’s agency—are as important as the four ethical challenges in the use of surgical innovations introduced by Johnson and Rogers [17]. Discounting, dismissing or excluding women’s experiences in evaluation of gender-specific surgical outcomes was wrong, but also led to unnecessary harm [21, 26]. Ethically relevant harms go beyond the direct physical and psychological harms done by the surgery itself in that both hermeneutic and testimonial injustice compounded the harms experienced. We have also suggested that women’s agency in managing their experience of TVM should be recognised, and that there should be a special responsibility towards those women unable to accommodate the changes they have experienced. Together, these studies suggest the need to ensure that the evidence base for innovative surgeries is particularly attentive to patient-centred accounts of outcomes, and that this evidence is used to plan and offer interventions in a way that will minimise both the wrongs and the harms done to women.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to Melissa Fox from Health Consumers Queensland, who first suggested the need for further research on women’s experience of transvaginal mesh and provided invaluable advice in the early stages of the project.

Declarations

Funding

This research is supported by the Australian Centre for Health Engagement Evidence and Values (ACHEEV) at University of Wollongong, NSW, and the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council Centre for Research Excellence, 1104136.

Conflict of Interest

Not applicable.

Ethics Approval

Not applicable.

Consent to Participate

Not applicable.

Consent for Publication

Not applicable.

Footnotes

Three of the included studies were from New Zealand where an Accident Compensation Corporation provides a no-fault compulsory insurance scheme that helps pay for recovery of accidently injured people. This includes treatment injuries caused as a direct result of treatment by a health professional that is not a normal side effect of treatment.

Contributor Information

Mina Motamedi, Email: mm870@uowmail.edu.au.

Stacy M. Carter, Email: stacyc@uow.edu.au

Chris Degeling, Email: degeling@uow.edu.au.

References

- 1.Heneghan CJ, Goldjacre B, Onakpoya I, et al. Trials of transvaginal mesh devices for pelvic organ prolapse: a systematic database review of the US FDA approval process. BMJ Open. 2017;7(12):e017125. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-017125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Karmakar D, Hayward L. What can we learn from the vaginal mesh story? Climacteric. 2019;22(3):277–282. doi: 10.1080/13697137.2019.1575355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McCullough LB, Gordon TA, Cameron JL. Ethical issues. Evidence-based surgery. Hamilton: BC Decker Inc; 2000.

- 4.Thompson C, Faunce TA. Australian senate committee report on transvaginal mesh devices. Thompson C Faunce TA Aust Senate Comm Rep Transvaginal Mesh Implants J Law Med. 2018;25(4):934–943. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rogers W, Degeling C, Townley C. Equity under the knife: justice and evidence in surgery. Bioethics. 2014;28:119–126. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8519.2012.01980.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Heneghan C, Aronson JK, Goldacre B, Mahtani KR, Plüddemann A, Onakpoya I. Transvaginal mesh failure: lessons for regulation of implantable devices. BMJ. 2017;359:j5515. 10.1136/bmj.j5515. PMID: 29217786. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Ford AA, Rogerson L, Cody JD, Aluko P, Ogah JA. Mid-urethral sling operations for stress urinary incontinence in women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017 doi: 10.1002/14651858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nambiar A, Cody JD, Jeffery ST, Aluko P. Single‐incision sling operations for urinary incontinence in women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9.Thomas J, Harden A. Methods for the thematic synthesis of qualitative research in systematic reviews. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2008;8(1):45–45. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-8-45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP). CASP checklists. Oxford, UK: CASP UK; 2018. http://www.casp-uk.net/checklists.

- 11.Lewin S, Booth A, Glenton C, Munthe-Kaas H, Rashidian A, Wainwright M, Bohren MA, Tunçalp Ö, Colvin CJ, Garside R, Carlsen B. Applying GRADE-CERQual to qualitative evidence synthesis findings: introduction to the series. Implementation Sci. 2018;13:2. 10.1186/s13012-017-0688-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 12.Bramwell E, Sullivan P. The Loss of a Life Well Lived: A qualitative study exploring the impact of surgical mesh implants on the lives of a group of New Zealand women. Unpublished report: Mesh Down Under group. 2019.

- 13.Brown JL. A Thorn in the Flesh: The experience of women living with pelvic surgical mesh complications. Otago University: Unpublished thesis. 2019.

- 14.Brown JL. The experiences of seven women living with pelvic surgical mesh complications. Int Urogynecol J. 2020;31:82. doi: 10.1007/s00192-019-04155-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dunn GE, Hansen BL, Egger MJ, et al. Changed women: The long-term impact of vaginal mesh complications. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg. 2014;20(3):131–136. doi: 10.1097/SPV.0000000000000083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Izett-Kay ML, Lumb C, Cartwright R, et al. 'What research was carried out on this vaginal mesh?' Health-related concerns in women following mesh-augmented prolapse surgery: a thematic analysis. BJOG. 2020;128:131–139. doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.16331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Johnson J, Rogers W. Innovative surgery: the ethical challenges. J Med Ethics. 2012;38(1):9–12. doi: 10.1136/jme.2010.042150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Convie LJ, Carson E, McCusker D, McCain RS, McKinley N, Campbell WJ, Kirk SJ, Clarke M. The patient and clinician experience of informed consent for surgery: a systematic review of the qualitative evidence. BMC Med Ethics. 2020;21(1):1–7. https://bmcmedethics.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12910-020-00501-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 19.Hutchison K, Rogers W, Eyers A, Lotz M. Getting clearer about surgical innovation. Ann Surg. 2015;262(6):949–954. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000001174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rogers WA, Hutchison K, McNair A. Ethical issues across the IDEAL stages of surgical innovation. Ann Surg. 2019;269(2):229–233. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000003106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fricker M. Epistemic injustice: power and the ethics of knowing. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Heneghan C, Aronson JK, Goldacre B, Mahtani KR, Plüddemann A, Onakpoya I. Transvaginal mesh failure: lessons for regulation of implantable devices. BMJ. 2017;7:359. doi: 10.1136/bmj.j5515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hutchison K, Rogers W. Hips, knees, and hernia mesh: when does gender matter in surgery. Int J Fem Approaches Bioethics. 2017;10(1):148–174. doi: 10.3138/ijfab.10.1.148. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Clarke AE. Situational analyses: grounded theory mapping after the postmodern turn. Symb Interact. 2005;26(4):553–576. doi: 10.1525/si.2003.26.4.553. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Uberoi P, Lee W, Lucioni A, Kobashi KC, Berry DL, Lee UJ. Listening to women: a qualitative analysis of experiences after complications from mesh mid-urethral sling surgery. Urology. 2021;1(148):106–112. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2020.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Blease C, Carel H, Geraghty K. Epistemic injustice in healthcare encounters: evidence from chronic fatigue syndrome. J Med Ethics. 2017;43(8):549–557. doi: 10.1136/medethics-2016-103691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.