Abstract

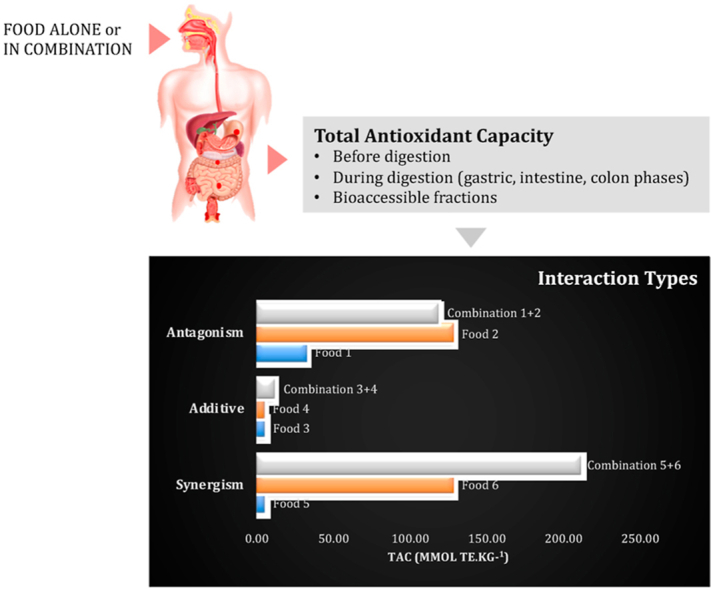

This study aims to investigate the antioxidant interactions between mostly co-consumed foods in daily diet. Total antioxidant capacities of individual and the binary combinations of certain food samples from different groups including fruits, vegetables, grain sources, dairy and meat products were measured. The types of interactions (synergism, antagonism, and additive) between food samples were determined by a statistical comparison between estimated and measured total antioxidant capacity. The results revealed an antagonism in the combinations of milk with the fruits or green tea extract while a clear synergism was reported in the combination of fruits with breakfast cereal, whole wheat bread, or yoghurt. The selected foods were also subjected to in vitro digestion protocol. Slightly alkaline conditions were found to significantly (p < 0.05) increase the total antioxidant capacity of foods. Synergism was observed during the digestion of the combinations of milk with fruits or tea extracts. Hydroxyl radical scavenging capacity was also determined in the bioaccessible fractions of foods. Green tea extract was found to be the most efficient scavenger (936.48 ± 16.64 mmol TE.kg−1).

Keywords: Food combinations, Co-digestion, Total antioxidant capacity, In vitro digestion, Synergism, Antagonism

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

Protein-phenol interactions provided an antagonism in milk combinations before digestion.

-

•

Protein-phenol interactions provided a synergism in milk combinations during digestion.

-

•

Transition metals in food caused prooxidation in lipid rich foods combinations.

-

•

The combination of breakfast cereal with fruits provided a clear synergism.

-

•

Hydroxyl radical scavenging potential of green tea was 936.48 ± 16.64 mmol TE.kg−1.

1. Introduction

Free radicals such as reactive oxygen and nitrogen species (ROS and RNS) are generated as a consequence of metabolic activities and are generally in balance with the antioxidant defense system in the human body (Phaniendra et al., 2015). Oxidative stress emerging from the imbalance between oxidants and antioxidants can cause damage in macromolecules such as lipids, proteins, and DNA and brings about pathological conditions eventually leading to tissue and cell damage, cardiovascular diseases, infectious diseases, diabetic complications, and neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer's (Liguori et al., 2018). In addition to the exogenous free radicals derived from dietary sources, the gastrointestinal tract is also constantly exposed to the free radicals through metabolic activities. Severe oxidative stress in the gastrointestinal tract has been involved in the pathogenesis of colorectal cancer and in inflammation-based gastrointestinal tract diseases (Kim et al., 2012). ROS and RNS in the gut can initiate, in the presence of transition metals, the lipid peroxidation of dietary polyunsaturated fatty acids, subsequently resulting in the production of lipid hydroperoxides and advanced lipoxidation end products (Tagliazucchi et al., 2010), which can be further absorbed and involved in the pathogenesis of some cardiovascular diseases (Halliwell et al., 2000).

Considering the health effects, prevention of oxidative stress in the body becomes important. In addition to the antioxidant defense system, natural antioxidant compounds found in foods and beverages consumed in daily diet are thought to play a crucial role in the prevention of oxidative stress. A substantial body of research has been conducted to investigate the antioxidant potential of the natural compounds in foods and beverages (Cömert and Gökmen, 2018). Many researchers have emphasized that the individual antioxidant capacity of a single compound is not adequate to assess the antioxidant potential of food or human plasma, as the compounds always present in the form of natural mixtures and may possess similar, overlapping, or different but complementary effects (Lila, 2009; Wang et al., 2011). There are several studies investigating the interactions between specific antioxidant compounds such as tocopherols, flavonoids, and ascorbic acid (Becker et al., 2007; Marinova et al., 2008; Hidalgo et al., 2010). The antioxidant capacities of combinations of different food extracts, including fruits, vegetables, and legumes, have been also evaluated (Wang et al., 2011). However, extraction methods could ignore the interactions of antioxidant compounds with the food macromolecules and bound antioxidant compounds, whose regeneration potential has been previously reported (Çelik et al., 2015). Considering the co-ingested food in daily diet, deep evaluation is needed to determine if the combination of foods would affect total antioxidant capacity (TAC) synergistically or antagonistically.

The gastrointestinal tract is of great importance because it is one of the major barriers to dietary antioxidant compounds in the human body in addition to being exposed to the oxidative stress. It was reported that the conditions in the gastrointestinal tract, such as digestive enzymes and pH in the stomach might influence the structures and functions of the antioxidant compounds (Segura-Campos et al., 2011). In a very recent study, it was indicated that co-digestion of Mediterranean diet salad with turkey meat could prevent lipid oxidation under gastrointestinal conditions (Martini et al., 2020a, Martini et al., 2020b). However, the effects of interactions between different food groups on TAC along the gastrointestinal tract have been ignored up to now.

To that end, in the present study, certain types of foods co-existing in daily diet were investigated in terms of their combined TACs determined by the QUENCHER method, which allows the physiological evaluation without any extraction procedure. Although the QUENCHER approach gives a basis to understand overall TACs of foods, the effects of gastrointestinal digestion on their TACs should be also considered. Therefore, TACs of the selected foods were also monitored at different stages of in vitro simulated gastrointestinal digestion system and in their bioaccessible fractions. In addition, hydroxyl radical scavenging capacity (HRSC) of foods were also determined in their bioaccessible fractions by electron spin resonance spectrometry (ESR). Accordingly, the resultant interaction types were determined at each step.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Chemicals and consumables

All chemicals and solvents used were of analytical grade, unless otherwise stated. Potassium peroxydisulfate, cellulose powder, 2,2-azinobis (3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid) (ABTS) (98%), 6-hydroxy-2,5,7,8-tetramethyl-chroman-2 carboxylic acid (Trolox) (97%), ethyl alcohol (96%), iron (II) sulfate heptahydrate (99%), and 5,5- dimethyl-1-pyrroline N-oxide (DMPO) (97%) were purchased from Sigma- Aldrich Chemie (Steinheim, Germany). Potassium chloride, sodium chloride, magnesium chloride, ammonium bicarbonate, potassium dihydrogen phosphate, methanol (98%), and hydrogen peroxide (30%, (w/w)) were purchased from Merck (Darmstadt, Germany). The enzymes pepsin (≥250 U/mg solid) from porcine gastric mucosa, pancreatin (4 × USP) from porcine pancreas, bile extract, protease from Streptomyces griseus, called also Pronase E (≥3.5 U/mg solid), and Viscozyme L were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich Chemie (Steinheim, Germany). Deionized water (5.6 μS/m) was used throughout the analysis and sample preparation. Syringe filters (nylon, 0.22 μm) were supplied by ISOLAB.

2.2. Food samples

A total of 20 foods, fresh and cooked, were selected from different food categories to represent the most consumed food in the daily diet. They were as follows: fruits (blueberry, strawberry, and black grape), vegetables (tomato, lettuce, and cabbage), dairy and meat products as a source of protein (milk, yoghurt, cheese, and jambon), grain sources (breakfast cereal and whole wheat bread), nuts and seeds (hazelnut, sesame, chia seed, and flaxseed), and beverage extracts (green tea extract, black tea extract, espresso, and wine). Fruits and vegetables were purchased from a local market and used freshly. Dairy and meat products, grains, nuts and seeds, and red wine, as processed foods, were purchased from the local market. Green tea and black tea extracts were obtained after brewing. A total of 3 g tea was brewed in 100 mL of boiling water for 15 min and tea infusions were filtered through a coarse filter paper. Espresso was prepared by brewing 6 g of coffee in 30 mL of water using a domestic coffee machine (DeLonghi Icona Vintage). All samples were frozen at − 80 °C and lyophilized. Lyophilized samples were ground using grinder and ceramic mortar prior to TAC measurement and in vitro digestion.

All samples and their mostly consumed binary combinations were exposed to TAC measurement to evaluate the interaction types between them. Besides, 12 selected food samples (strawberry, milk, cheese, jambon, breakfast cereal, whole wheat bread, hazelnut, flaxseed, green tea extract, black tea extract, espresso extract, and wine) and their binary combinations were subjected to the in vitro digestion protocol. TACs and the resultant interaction types were determined at each digestion step.

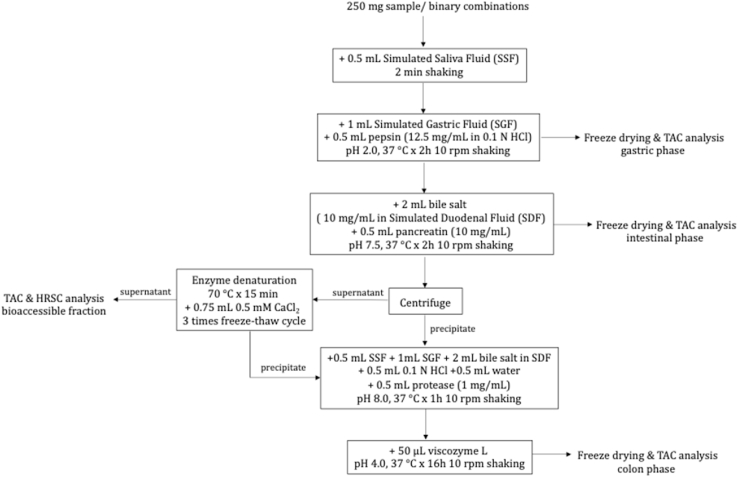

2.3. In vitro digestion

The in vitro digestion procedure and the steps being followed in this study were summarized in Fig. 1. Simulated salivary fluid (SSF), simulated gastric fluid (SGF), and simulated duodenal fluid (SDF) were prepared according to the procedure described by Minekus et al. (2014). A total of 250 mg of ground food samples or their binary combinations were transferred to a tube. The amount of food samples in the combinations to be digested was determined according to the serving size and the moisture content of the food samples and was listed in Table 1. To simulate the oral phase, 0.5 mL of SSF was added to the tube and shaken for 2 min. For the gastric digestion simulation, 0.5 mL of pepsin solution (12.5 mg/mL in 0.1 M HCl) and 1 mL of SGF were added to the mixture and it (pH 2.0) was incubated at 37 °C by shaking for 2 h at a speed of 10 rpm (revolutions per minute). To simulate the intestinal phase, 2 mL of the mixture of SDF with bile salt (10 mg/mL) and 0.5 mL of pancreatic solution (10 mg/mL in water) were added to the mixture and it (pH 7.5) was incubated at 37 °C for 2 h by shaking at a speed of 10 rpm. After intestinal digestion, the mixture was centrifuged, and the supernatant was transferred to another tube to prepare the bioaccessible fraction while the precipitate was kept completing digestion through the colon phase. The supernatant was heated at 70 °C for 15 min to denature the digestive enzymes. Digestive enzymes and other macromolecules present in the supernatant were precipitated by means of freeze-thaw cycles three times with adding of CaCl2 (50 mM). Then, the obtained supernatant was used as the bioaccessible fraction and the precipitate was added to the previous precipitate to complete digestion through the colon phase. For the colon phase, 0.5 mL of protease (1 mg/mL) and the digestive fluids were added to the tube involving the precipitates and the mixture (pH 8.0) was incubated at 37 °C for 1 h by shaking at a speed of 10 rpm. After that, 50 μL of Viscozyme L was added, and the mixture (pH 4.0) was incubated at 37 °C by shaking for 16 h. At the end of each digestion phase (gastric, intestinal, and colon), the samples in the tubes for the related phase were immediately frozen at − 80 °C to stop the reaction. All samples were digested in triplicate as described above.

Fig. 1.

Schematic representation of the steps of the simulated in vitro gastrointestinal digestion process.

Table 1.

The amounts of foods in the combinations subjected to the in vitro digestion protocol.

| Food Combinations | Food | Digested amount (mg) |

|---|---|---|

| BC + Milk | BC | 125.00 |

| Milk | 125.00 | |

| BC + Strawberry | BC | 162.50 |

| Strawberry | 87.50 | |

| Milk + Strawberry | Milk | 162.50 |

| Strawberry | 87.50 | |

| BC + Flaxseed | BC | 197.00 |

| Flaxseed | 53.00 | |

| BC + Hazelnut | BC | 130.00 |

| Hazelnut | 120.00 | |

| Milk + Flaxseed | Milk | 197.00 |

| Flaxseed | 53.00 | |

| Milk + GTE | Milk | 232.10 |

| GTE | 17.90 | |

| Milk + BTE | Milk | 232.10 |

| BTE | 17.90 | |

| Milk + Espresso | Milk | 216.70 |

| Espresso | 33.30 | |

| WWB + GTE | WWB | 228.30 |

| GTE | 21.70 | |

| WWB + BTE | WWB | 227.50 |

| BTE | 22.50 | |

| WWB + Jambon | WWB | 134.60 |

| Jambon | 115.40 | |

| Jambon + Cheese | Jambon | 125.00 |

| Cheese | 125.00 | |

| WWB + Wine | WWB | 169.40 |

| Wine | 80.60 | |

| Jambon + Wine | Jambon | 160.70 |

| Wine | 89.30 | |

| Cheese + Wine | Cheese | 160.70 |

| Wine | 89.30 |

BC: breakfast cereal, WWB: whole wheat bread, GTE: green tea extract, BTE: black tea extract.

2.4. Measurement of TAC by QUENCHER procedure

TAC of foods was measured by QUENCHER procedure using ABTS·+ as described elsewhere by Serpen et al. (2012). Briefly, 10 mg of the lyophilized foods, digests, or 100 μL of the bioaccessible fractions were transferred into a test tube and the reaction was started by adding 10 mL of ABTS·+. Following the vigorous shake in an orbital shaker at 350 rpm for 27 min in the dark, the tube was centrifuged at 6080×g for 2 min. After a total of 30-min reaction time, the optically clear supernatant was transferred into a cuvette, and absorbance was measured at 734 nm using a Shimadzu model 2100 variable wavelength UV–visible spectrophotometer (Shimadzu Corp., Kyoto, Japan). For the values of absorbance were below the linear response range of the radical discoloration formation due to the high antioxidant capacity, a preliminary dilution was performed by mixing lyophilized foods with cellulose. A calibration curve was built with Trolox in the concentration range between 0 and 600 mg L−1. The results were expressed as mmol Trolox equivalent (TE) per kg in dried weight.

TAC of each sample and their binary combinations before and at the end of digestion steps were measured. The measured antioxidant capacity of the binary combinations was expressed as TACmeasured. TACestimated values were calculated by summing the individual TAC of each food in the binary combinations. The interaction types (synergism, antagonism, and additive) were determined by a statistical comparison of TACmeasured with TACestimated values for each binary combination.

2.5. Measurement of HRSC by ESR

HRSC of the bioaccessible fraction of food was measured using ESR as described by Madhujith and Shahidi (2006), with some modifications. The hydroxyl radical generated via Fe (II)-catalyzed Fenton reaction spin trapped with DMPO and obtained DMPO-OH adduct was detected using a Bruker MicroESR (Bruker Biospin Co.). A total of 100 μL of bioaccessible fraction (water for blank) was mixed with 100 μL of 10 mM H2O2, 200 μL of 17.6 mM DMPO, and 100 μL of 1 mM FeSO4. All solutions were prepared in deionized water except FeSO4, which was dissolved in deoxygenated distilled water to maintain reduced status until mixed with the other reagents. After 1 min, the mixtures were passed through the capillary tubing, which guides the sample through the sample cavity of the magnet unit of the ESR spectrometer. The ESR spectrum was recorded at 24.0 dB digital gain, 2.0 G modulation amplitude, 1600 points, 5 scans, 3480.0 G center field, and 9.795 GHz microwave frequency. HRSC of the bioaccessible fraction of food was calculated by determination of the signal inhibition (%) according to the blank. A calibration curve was built by plotting the inhibition percentages (%) against the different concentrations (range between 0 and 600 mg L−1) of Trolox. The results were expressed as mmol Trolox equivalent (TE) per kg of digested food in dried weight.

2.6. Statistical analysis

Results of all experiments were reported as the mean ± standard deviation. Differences between measured and estimated TAC values of the food combinations were determined by the student t-test by using SPSS 17.0 statistical package. Duncan test was used for the evaluation of statistical significance of the differences among the TAC of foods at different digestion steps. p < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant for the results.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Effects of food-food interactions on TAC

Table 2 gives the measured and estimated TACs of the binary combinations of foods and the resultant interaction types determined by a statistical comparison of TACmeasured with TACestimated. TACmeasured values express the experimental data obtained from the measurement of TAC of the binary combinations while TACestimated values represent the calculated data obtained by summing the individual TAC of each food in the binary combinations. Synergism refers to a greater overall effect in the combination of two samples compared to the simple addition of their individual effects, which means that TACmeasured is greater (p < 0.05) than TACestimated, while the phenomenon, in which a lower (p < 0.05) net interactive effect than the sum of their individual effects (TACmeasured < TACestimated), is known as antagonism. Additive interaction occurs when a net interactive antioxidant effect is as same (p > 0.05) as the sum of the individual effects.

Table 2.

Measured and estimated total antioxidant capacity (TACmeasured and TACestimated) values of food combinations, and the resultant interaction types (S: synergism, An: antagonism, Add: additive).

| Food Combinations | TACmeasured (mmol TE.kg−1) | TACestimated (mmol TE.kg−1) | Interaction type |

|---|---|---|---|

| BC combinations | |||

| with fruits | |||

| BC + Strawberry | 211.39 ± 3.36b | 133.04 ± 2.82a | S |

| BC + Blueberry | 151.57 ± 18.26b | 117.73 ± 10.12a | S |

| BC + Black grape | 340.79 ± 13.22b | 212.29 ± 21.90a | S |

| with nuts and seeds | |||

| BC + Hazelnut | 43.35 ± 0.18b | 28.22 ± 1.61a | S |

| BC + Chia seed | 14.21 ± 0.84a | 12.99 ± 0.58a | Add |

| BC + Flaxseed | 14.34 ± 0.13a | 14.07 ± 0.34a | Add |

| with dairy products | |||

| BC + Yoghurt | 11.29 ± 0.15a | 9.56 ± 0.95a | Add |

| BC + Milk | 13.15 ± 3.65a | 37.25 ± 0.70b | An |

| WWB combinations | |||

| with beverages | |||

| WWB + GTE | 4441.3 ± 147.43b | 3193.59 ± 9.51a | S |

| WWB + BTE | 1926.61 ± 45.65b | 1113.29 ± 83.80a | S |

| with seeds | |||

| WWB + Flaxseed | 14.10 ± 0.73a | 17.26 ± 0.79b | An |

| WWB + Chia seed | 10.99 ± 1.28a | 16.19 ± 0.31b | An |

| WWB + Sesame | 8.66 ± 0.88a | 11.94 ± 0.42b | An |

| with dairy products | |||

| WWB + Cheese | 12.2 ± 1.29a | 13.41 ± 0.27a | Add |

| WWB + Milk | 29.72 ± 1.49a | 40.45 ± 0.59b | An |

| Dairy products combinations | |||

| with fruits | |||

| Milk + Strawberry | 118.13 ± 2.23a | 160.42 ± 2.87b | An |

| Milk + Blueberry | 102.38 ± 4.84a | 145.11 ± 5.41b | An |

| Milk + Black grape | 195.29 ± 12.43a | 239.68 ± 21.95b | An |

| Yoghurt + Strawberry | 157.01 ± 12.53b | 132.73 ± 2.84a | S |

| Yoghurt + Blueberry | 183.76 ± 3.97b | 117.42 ± 10.14a | S |

| Yoghurt + Black grape | 341.04 ± 23.93b | 211.98 ± 21.92a | S |

| with seeds | |||

| Milk + Chia seed | 17.65 ± 4.64a | 40.38 ± 0.46b | An |

| Milk + Flaxseed | 22.66 ± 0.37a | 41.45 ± 0.94b | An |

| Yoghurt + Flaxseed | 22.90 ± 4.05b | 13.76 ± 0.91a | S |

| Yoghurt + Chia seed | 12.71 ± 1.02a | 12.69 ± 0.43a | Add |

| with beverages | |||

| Milk + GTE | 2862.26 ± 104.74a | 3217.78 ± 9.66b | An |

| Milk + BTE | 2666.21 ± 237.4b | 1137.48 ± 83.95a | S |

| Milk + Espresso | 586.94 ± 29.72b | 361.08 ± 9.66a | S |

| Yoghurt + GTE | 3645.94 ± 186.97b | 3190.09 ± 9.63a | S |

| Yoghurt + BTE | 1256.02 ± 131.87b | 1109.79 ± 83.93a | S |

| Yoghurt + Espresso | 657.90 ± 35.01b | 333.39 ± 9.63a | S |

| Cheese + GTE | 2748.97 ± 130.02a | 3190.73 ± 9.34b | An |

| Cheese + BTE | 1517.11 ± 5.97b | 1110.43 ± 83.63a | S |

| Cheese + Espresso | 632.1 ± 20.27b | 334.03 ± 9.34a | S |

| Meat combinations | |||

| Jambon + WWB | 22.01 ± 2.65a | 26.26 ± 1.04b | An |

| Jambon + Lettuce | 35.43 ± 0.37a | 45.63 ± 1.00b | An |

| Jambon + Tomato | 29.95 ± 1.46a | 39.22 ± 3.10b | An |

| Jambon + Cheese | 34.22 ± 0.56b | 23.4 ± 0.87a | S |

| Vegetable combinations | |||

| Lettuce + Tomato | 65.9 ± 1.03b | 48.6 ± 2.46a | S |

| Lettuce + Cabbage | 112.56 ± 7.85b | 99.63 ± 2.91a | S |

| Lettuce + Flaxseed | 51.05 ± 6.45b | 36.63 ± 0.75a | S |

| Lettuce + Chia seed | 46.81 ± 3.32b | 35.56 ± 0.27a | S |

| Tomato + WWB | 34.83 ± 2.40a | 29.23 ± 2.50a | Add |

| Tomato + Cheese | 31.53 ± 6.98a | 26.36 ± 2.33a | Add |

| Wine combinations | |||

| Wine + Tomato | 486.03 ± 1.10b | 414.5 ± 17.73a | S |

| Wine + Black grape | 1730.53 ± 95.08b | 600.77 ± 37.03a | S |

| Wine + WWB | 458.78 ± 2.38b | 401.54 ± 15.67a | S |

| Wine + Cheese | 487.31 ± 2.38b | 398.68 ± 15.50a | S |

| Wine + Jambon | 584.77 ± 14.26b | 411.53 ± 16.27a | S |

Results are expressed as mean ± SD (n = 3). Different letters in the same row denote statistically significant differences (P < 0.05) according to student t-test. BC: breakfast cereal, WWB: whole wheat bread, GTE: green tea extract, BTE: black tea extract.

The binary combinations of breakfast cereal with fruits (strawberry, blueberry, and black grape) resulted in a clear synergism. A synergistic interaction was also seen in the binary combination of breakfast cereal with hazelnut while additive interactions between breakfast cereal and seeds (chia seed, flax seed) were observed. In the binary combination of breakfast cereal with yoghurt, no statistical difference (p > 0.05) between TACmeasured (11.29 ± 0.15 mmol TE.kg−1) and TACestimated (9.56 ± 0.95 mmol TE.kg−1) was observed while lower TAC (13.15 ± 3.60 mmol TE.kg−1) was measured compared to the expected from the binary combination of breakfast cereal with milk (37.25 ± 0.70 mmol TE.kg−1), pointing toward a clear antagonistic interaction. It was seen that whole wheat bread, as another main grain product mostly consumed in daily diet, interacted synergistically with green tea and black tea, the sources of the soluble phenolic compounds, while it interacted antagonistically with the seeds (flax seed, chia seed, and sesame) including bound antioxidant compounds, lignans and dietary fiber in their structure (Açar et al., 2009; Aludatt et al., 2013).

Corn-based plain breakfast cereal and conventional whole wheat bread exert antioxidant activity mainly due to the commercially added antioxidant compounds (such as tocopherol), phenolic acids bound to the dietary fiber in addition to the neo-formed antioxidant compounds such as melanoidins formed during thermal processes (Miller et al., 2000). Therefore, it was thought that soluble antioxidant compounds in fruits and beverages might be regenerated by the grain-based bound antioxidant compounds, melanoidins, and tocopherol present in breakfast cereal and whole wheat bread. A clear synergism between soluble antioxidant compounds and dietary fiber bound antioxidants demonstrated by Çelik et al. (2015) is also in good agreement with the results of the present study. Lipid fractions are predominant in seeds and hazelnut, and lipid soluble antioxidants, lignans, and dietary fiber bound antioxidants constitute to their antioxidant compositions (Venkatachalam and Sathe, 2006; Rabetafika et al., 2011). Besides, transition metal ions induce the prooxidative reactions especially in lipid fractions. The metal ions found in whole wheat bread were able to trigger oxidation in seeds and antagonistic interaction become unavoidable in these binary combinations.

When milk, as a protein source, combined with fruits, seeds, whole wheat bread, or green tea extract, TAC of the binary combination was measured to be lower (p < 0.05) than TACestimated, whereas its binary combination with black tea extract or with espresso resulted in a synergism. Protein-phenol interaction, a well-known phenomenon between milk proteins and phenolic compounds (Bandyopadhyay et al., 2012) was most likely the reason for the antagonism in the combinations of milk. However, the molecular weight and the size of phenolic compounds are thought to have significant effects on their interactions with protein. Black tea includes the polymerized forms of catechins, such as theaflavin and thearubigins (Peluso and Serafini, 2017), and espresso is rich in neo-formed high molecular weight antioxidants called melanoidins (Perrone et al., 2012). The mentioned polymerized compounds might impede the interactions between milk proteins and phenolic compounds and prevent the antagonism in their binary combinations. In a study, a masking effect on TAC due to the presence of milk in green tea has been attributed to interactions between proline groups of casein and hydroxyl groups of catechin. However, it has been noted that the interaction of coffee with milk have no significant effects on the TAC of coffee added with milk (Cilla et al., 2011). Another study showed that larger gallate esters of catechin were less affected by the presence of casein compared to smaller catechin (Bourassa et al., 2013).

In contrast to milk, yoghurt was found to interact synergistically (p < 0.05) with other certain types of foods, except chia seed (p > 0.05). TAC was also found to be higher in the combination of cheese with black tea extract or with espresso, while the presence of tomato or whole wheat bread did not cause statistically significant (p > 0.05) differences from the expected TAC. On the other hand, antagonism was observed between cheese and green tea extract. The antioxidant potential of protein is mostly dependent on the pH of the medium, which affects the net charge of protein and electron/hydrogen donation. The lower net charge of yoghurt and cheese than milk was thought to be the reason for lower antioxidant potential and resultant synergistic interaction with the foods. Moreover, in yogurt production, milk is homogenized and heated at 85–95 °C prior to fermentation to improve the textural properties. This treatment induces whey protein unfolding, aggregation and partial adsorption to the surface of casein micelles (Lamothe et al., 2014), which might diminish the affinity of proteins to the phenolic compounds.

The binary combinations of jambon with mostly co-consumed foods, whole wheat bread, lettuce, tomato, or cheese, resulted in antagonism. The transition metals found in meat protein, both heme and non-heme irons (Papuc et al., 2017), were thought to induce the oxidation in the binary combinations, providing a clear antagonism. On the other hand, wine interacted synergistically with the certain types of food (cheese, black grape, tomato, and whole wheat bread). It might be speculated that the anthocyanins, flavonoids, and resveratrol present in wine might be regenerated or stabilized by other food components including proteins, phenolic compounds, lycopene, or dietary fiber bound antioxidants. Regeneration of the antioxidant compounds by co-exist antioxidant compounds and their stabilization through other components in reaction medium are the phenomenon well accepted and extensively studied (Chen et al., 2021). Similarly, in the combinations of lettuce with other vegetables and seeds, TACmeasured was found to be higher than TACestimated, providing the synergistic interaction (p < 0.05). In a similar vein with the present study, Altunkaya et al., 2009 showed the synergistic antioxidant effects between lettuce extract and certain phenolic compounds on lipid oxidation.

3.2. Changes in TAC of foods during simulated gastrointestinal digestion

Table 3 gives the changes in TACs of the certain foods at the end of different stages of gastrointestinal digestion system. Gastric, intestine, and colon conditions had significant (p < 0.05) effects on TAC of food. At the end of gastric and intestinal digestion, there was a 2- and 5-fold increase in TAC of breakfast cereal compared to the initial TAC (9.87 ± 0.65 mmol TE.kg−1). The limited amount of antioxidant compounds was able to move to the colon and was most likely exposed to the oxidation, while 60% of antioxidant compounds in breakfast cereal were found to be ready for the absorption in its bioaccessible fraction (29.64 ± 1.74 mmol TE.kg−1). Similarly, Rufián-Henares and Delgado-Andrade (2009) showed that digestion process including gastric and intestinal phases caused a 4-fold increase in TAC of the breakfast cereal and the insoluble fraction that could reach the colon phase, was 20% of its TAC (Rufián-Henares and Delgado-Andrade, 2009). The increase could be associated with the antioxidant compounds buried in the food matrix which could be released due to the digestive enzyme activity, and acidic and/or alkaline environment.

Table 3.

Total antioxidant capacity (TAC) of foods at the end of each digestion step and in their bioaccessible fractions.

| Foods | TAC (mmol TE.kg−1) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Initial | Gastric phase | Intestinal phase | Colon phase | Bioaccessible fraction | |

| BC | 9.87 ± 0.65b | 19.09 ± 0.69c | 49.78 ± 0.08e | 3.95 ± 0.01a | 29.64 ± 1.74d |

| WWB | 16.27 ± 0.44a | 17.27 ± 1.38a | 123.32 ± 18.66c | 59.55 ± 10.6a | 70.8 ± 9.89ab |

| Flaxseed | 18.26 ± 1.14a | 40.25 ± 14.76ab | 83.46 ± 12.45b | 84.8 ± 19.1b | 101.74 ± 1.74b |

| Hazelnut | 46.57 ± 2.57a | 96.8 ± 19.02ab | 128.48 ± 5.97b | 83.39 ± 7.08ab | 107.41 ± 2.18b |

| Milk | 64.64 ± 0.74b | 10.29 ± 0.29a | 175 ± 14.74c | 3.46 ± 0.44a | 169.31 ± 5.67c |

| Cheese | 10.54 ± 0.14a | 72.48 ± 16.22ab | 192.71 ± 19.00b | 89.96 ± 37.99ab | 166.08 ± 17.08b |

| Jambon | 36.24 ± 1.64a | 33.63 ± 5.55a | 145.75 ± 15.16b | 131.37 ± 22.2b | 90.58 ± 6.29ab |

| Strawberry | 256.21 ± 4.49bc | 313.19 ± 21.67c | 173.49 ± 17.25ab | 174.17 ± 53.52ab | 108.72 ± 2.62a |

| GTE | 6370.92 ± 18.52b | 6621.66 ± 768.42b | 7068.25 ± 928.51b | 2971.63 ± 320.18a | 5052.22 ± 161.79ab |

| BTE | 2210.32 ± 167.17b | 3106.38 ± 347.82b | 2445.08 ± 165.43b | 1884.61 ± 318.13b | 472.8 ± 4.49a |

| Espresso | 657.52 ± 18.57b | 1582.57 ± 118.77bc | 959.44 ± 76.35b | 825.27 ± 23.33b | 243.6 ± 26.96a |

| Wine | 786.82 ± 30.90a | 1476.33 ± 391.26b | 585.96 ± 74.92a | 788.01 ± 2.77a | 398.87 ± 8.76a |

Results are expressed as mean ± SD (n = 3). Different letters in the same row denote statistically significant differences (P < 0.05) according to Duncan test. BC: breakfast cereal, WWB: whole wheat bread, GTE: green tea extract, BTE: black tea extract.

TAC of whole wheat bread (16.27 ± 0.44 mmol TE.kg−1) remained unaltered at the end of gastric digestion, while incorporation of pancreatin and alkaline conditions in the intestinal phase caused an 8-fold increase compared to the initial TAC. It was observed that 57% of antioxidant compounds was left in the bioaccessible fraction at the end of intestinal digestion, and the remaining part of the antioxidant compounds was exposed to the colonic digestion. In a similar manner with the present study, it was reported that TAC of whole wheat bread subjected to the different heat treatments was between 73 and 122 mmol TE.kg−1; however, despite a dramatic increase in the soluble fraction under gastric conditions, intestinal digestion was indicated eventually not to change TAC as much as in that of the present study (Delgado-Andrade et al., 2010).

Intestinal conditions caused significant increases (p < 0.05) in TACs of flaxseed and hazelnut, although gastric conditions did not cause any statistically significant (p > 0.05) changes. Surprisingly, the ascending TACs were observed at the end of colonic digestion, as well as exerting the highest TAC in the bioaccessible fractions of flaxseed and hazelnut. Slightly alkaline environment, bile salt, and lipase activity in pancreatin might trigger the activity of the lipid soluble phenolic compounds and peptide fractions, but phenolic acids bound to the insoluble fiber are generally resistant to the absorption (Cömert and Gökmen, 2017). Therefore, the antioxidant activity of grains, seeds, and nuts could be further enhanced by the microbial dependent enzymatic hydrolysis during colonic digestive processes. In agreement with the present study, between 49% and 66% of the phenolic compounds in hazelnut were found to be bioavailable at the end of gastrointestinal digestion (Herbello-Hermelo et al., 2018); and therefore, the remaining fractions most likely remained in the colon phase.

Dairy products, milk and cheese, showed different antioxidant behavior from each other during gastrointestinal digestion beyond having different initial TAC values. TAC of milk and cheese was found to be 64.64 ± 0.74 and 10.54 ± 0.14 mmol TE.kg−1, respectively. Incorporation of pepsin and acidic pH under gastric conditions caused a significant (p < 0.05) decrease in TAC of milk in contrast to increase in that of cheese. By further intestinal digestion, TAC of milk was found to reach to the level of 175 ± 14.74 mmol TE.kg−1 which also remained stable in its bioaccessible fraction. TAC of cheese also significantly increased at the end of intestinal digestion compared to the initial TAC, and the significant antioxidant activity were observed in colon phase in addition to exerting high antioxidant potential in the bioaccessible fraction.

Dairy products as the protein sources are able to exert antioxidant activity with their hydrophilic, hydrophobic, and aromatic amino acid side chains by donating protons or electrons to the radicals or chelating the metals (Tagliazucchi et al., 2016). The amino acid composition and the medium pH determine the net charge of milk proteins, which has a significant impact on the antioxidant potential of milk. It was supposed that differently charged peptides might show different fate during gastrointestinal digestion (Ao and Li, 2013). The net charge of the milk protein is negative before digestion, but it turns to the positive under gastric conditions, which caused a dramatic reduction in TAC of milk. Tagliazucchi et al. (2016) reported that the pH of bovine milk close to the isoelectric point such as acidic conditions in the gastric phase evoked masking the reaction between ABTS·+ and antioxidant peptides. In the same vein, the destruction of the positively charge casein fractions during gastric digestion within 2 h was asserted in a study evaluating the effects of charge properties of peptides on digestion stability (Ao and Li, 2013). During digestion, proteolytic gastrointestinal enzymes release the peptides and amino acid sequences that are inactive or buried in the core of the source protein but can exhibit special properties once liberated (Segura-Campos et al., 2011), providing an increase in its radical scavenging potential. However, pepsin was found to reduce the stability of aromatic amino acids in the casein fractions, by cleavage of the peptide bonds in the amino terminal of aromatic amino acids, such as phenylalanine, tryptophan, and tyrosine, which are significant radical scavengers in peptides (Ao and Li, 2013). In the same study, further pancreatin activity and the cleavage of the peptide bonds in the C terminal of lysine and arginine were likely held responsible for the increase in TAC of casein fractions. Higher TAC of cheese than milk under colon conditions was thought to be related to the cheese being resistant to hydrolysis under intestinal conditions and carrying its activity up to the colon. Lamothe et al. (2014) also supported this hypothesis by asserting that yoghurt and milk were exposed to faster protein and fat hydrolysis compared to cheese.

TAC of jambon was found to be stable during gastric digestion while intestinal digestion significantly (p < 0.05) increased its activity. More than 60% of its capacity at the end of intestinal digestion was found to be in the bioaccessible fraction and its TAC further increased in the colon phase. Meat contains significant amounts of insoluble fractions as well as high fat content. It has specific antioxidant compounds which are mostly dipeptides such as carnosine, anserine, and other substances such as L-carnitine, glutathione, creatine, and taurine (Liu et al., 2016). The combination of bile salt, pancreatin, and alkaline environment during intestinal digestion likely enriched the accessibility of the antioxidant compounds in jambon. In addition, the remaining antioxidants bound to insoluble fraction reached the colon and were probably released by enzymatic digestion. In a similar with the present study, Kim and Hur (2018) also reported that the intestinal digestion caused a 5-fold increase in TAC of pork patties and its activity remained stable through the colon.

Regarding food and beverage extracts (strawberry, green tea, black tea, espresso, and wine) with high antioxidant capacity due to the soluble phenolic compounds, gastric conditions were found to have no significant effects (p > 0.05) on their TAC, except wine. There was an approximately 2-fold increase in TAC (1476.33 ± 391.26 mmol TE.kg−1) of wine under gastric conditions. A significant part of the antioxidant capacity of wine and strawberry lost during incubation with pancreatin and bile salts at slightly basic pH, but that was stable in the digests of green tea extract, black tea extract, and espresso. At the end of intestinal digestion, a good proportion of TAC remained stable in the bioaccessible fractions of strawberry (108.72 ± 2.62 mmol TE.kg−1), green tea (5052.22 ± 161.79 mmol TE.kg−1), and wine (398.87 ± 8.76 mmol TE.kg−1), but it was found to be limited in espresso (243.6 ± 26.96 mmol TE.kg−1) and black tea (472.8 ± 4.49 mmol TE.kg−1). High molecular weight phenolic compounds found in espresso and black tea were thought to be the reason for low TACs in the bioaccessible fractions. The effects of molecular weight and size of a phenolic compound on its bioaccessibility and its limited recovery, as in the example of theaflavins in black tea, have been demonstrated before (Ketnawa et al., 2021).

Radical scavenging reactions depend on the structures of a radical scavenger and the radical itself, and the environmental conditions such as pH. According to the results, anthocyanins found in strawberry and wine were largely affected by the pH changes during gastrointestinal tract, rather than other phenolic compounds found in green tea, black tea, and espresso. In agreement with our study, most of the phenolic compounds, including flavonoids and anthocyanins, and their antioxidant potential have been reported to be quite stable under acidic conditions mimicking the stomach, despite the differences in the incubation conditions and the antioxidant measurement methods used. Besides, the small increases in anthocyanins following the gastric incubation were also revealed before and it was linked with the lower pH of the sample under gastric conditions than the pH of the fresh initial sample, which renders an increase of the flavylium cation in the solution (Bermúdez-Soto et al., 2007). There are contradictory studies about the effects of alkaline conditions on the antioxidant activity of phenolic compounds during pancreatic digestion. Some authors indicated that an increase in the racemization of molecules with increasing pH renders antioxidants more reactive at acidic pH in the gastric phase than at slightly alkaline conditions in the intestinal phase while others alleged that the antioxidant capacity of dietary antioxidants tend to increase as digestion progressed through the intestinal phase (Ketnawa et al., 2021). The increases in radical scavenging activity under intestinal conditions have been attributed to the deprotonation of the hydroxyl moieties present on the aromatic rings of the phenolic compounds (Tagliazucchi et al., 2010), which might also impair their stability. Herein, different antioxidant capacity measurement methods in addition to the different experimental conditions are thought to have significant effects on these contradictory results. Besides, total phenolic compounds were found to be stable or incline to increase although degradation of flavonoids was observed under intestinal conditions (Tagliazucchi et al., 2010; Donlao and Ogawa, 2018). It should be bear in mind that previous studies have focused on the specific phenolic compounds in the soluble fractions under intestinal conditions, while the food matrices, the insoluble bound antioxidant compounds, and the isomerization and degradation products derived from unstable flavonoids under intestinal conditions were mostly ignored. On the other hand, in the present study, overall TAC, including soluble and insoluble antioxidant compounds, as well as considering with the food matrix effects was determined in each digestion step. It was seen that the presence of food matrix, and insoluble and soluble antioxidant compounds together could affect TAC due to the interactions in the gastrointestinal tract.

3.3. Effects of food-food interactions on TAC of foods during simulated gastrointestinal digestion

Table 4 gives the measured and estimated TACs of the binary combinations of foods in the different digestion phases and the resultant interaction types determined by a statistical comparison of TACmeasured with TACestimated. Co-digestion of breakfast cereal or whole wheat bread with flaxseed caused a slightly but statistically significant (p < 0.05) decrease compared to TACestimated under gastric conditions, providing an antagonistic interaction, while synergism was observed in their binary combinations under intestinal conditions. Hazelnut interacted antagonistically with breakfast cereal under intestinal conditions despite the additive interaction under gastric and colon conditions. Strawberry or milk caused a synergistic or additive interaction with breakfast cereal under gastric and intestinal conditions while breakfast cereal caused a significant decrease in TAC of strawberry in the colon phase. Whole wheat bread combinations with jambon, or with beverage extracts black tea and wine, resulted in additive or synergistic interactions under each digestion step, while its co-ingestion with green tea caused a clear antagonism under intestinal conditions. Within the presence of jambon, TAC of wine inclined to decrease at the end of colonic digestion (86.81 ± 0.42 mmol TE.kg−1) and resulted in antagonism.

Table 4.

Measured (M) and estimated (E) total antioxidant capacity values of food combinations at the end of each digestion step and in their bioaccessible fractions, and the resultant interaction types (S: synergism, An: antagonism, Add: additive).

| Food Combinations | TAC (mmol TE.kg−1) |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gastric phase | Intestinal phase | Colon phase | Bioaccessible fraction | ||||||

| BC + Flaxseed | M | 19.62 ± 0.10a | An | 115.63 ± 11.00b | S | 2.50 ± 0.41a | An | 47.26 ± 0.44a | An |

| E | 29.32 ± 1.40b | 56.51 ± 2.42a | 20.12 ± 3.83b | 53.62 ± 1.74b | |||||

| BC + Hazelnut | M | 43.49 ± 2.29a | Add | 67.26 ± 8.34a | An | 55.71 ± 11.68a | Add | 30.29 ± 8.02a | An |

| E | 57.94 ± 9.85a | 89.13 ± 3.03b | 43.67 ± 3.54a | 74.5 ± 0.22b | |||||

| BC + Milk | M | 18.25 ± 0.29b | S | 180.19 ± 2.49b | S | 4.23 ± 1.71a | Add | 125.28 ± 0.87b | S |

| E | 14.69 ± 0.20a | 159.43 ± 7.27a | 3.7 ± 0.21a | 105.45 ± 3.71a | |||||

| BC + Strawberry | M | 161.37 ± 26.98a | Add | 181.11 ± 24.55b | S | 71.89 ± 17.25a | An | 60.77 ± 3.49a | Add |

| E | 124.97 ± 7.36a | 94.31 ± 6.26a | 128.78 ± 23.22b | 65.76 ± 2.06a | |||||

| WWB + Flaxseed | M | 19.89 ± 0.37a | An | 94.88 ± 9.76a | Add | 75.99 ± 1.63a | Add | 56.85 ± 6.54a | An |

| E | 30.51 ± 3.47b | 113.35 ± 10.88a | 65.86 ± 12.73a | 78.54 ± 6.98b | |||||

| WWB + GTE | M | 584 ± 151.16a | Add | 237.87 ± 18.89a | An | 1062.28 ± 50.39b | S | 201.71 ± 4.81a | An |

| E | 611.66 ± 70.41a | 748.36 ± 100.55b | 321.64 ± 19.17a | 519.13 ± 23.56b | |||||

| WWB + BTE | M | 222.9 ± 62.98a | Add | 349.14 ± 67.18a | Add | 413.57 ± 132.26b | S | 132.31 ± 9.38b | S |

| E | 295.29 ± 30.05a | 332.27 ± 31.87a | 223.81 ± 38.28a | 106.98 ± 8.59a | |||||

| WWB + Wine | M | 64.82 ± 6.31a | Add | 118.59 ± 39.57a | Add | 68.29 ± 8.42a | Add | 51.14 ± 8.20a | Add |

| E | 80.22 ± 17.09a | 113.37 ± 9.61a | 78.06 ± 7.29a | 67.97 ± 6.52a | |||||

| Milk + Flaxseed | M | 69.99 ± 2.5b | S | 136.52 ± 19.61a | Add | 27.34 ± 10.01a | Add | 70.28 ± 3.07a | An |

| E | 22.88 ± 2.28a | 155.78 ± 14.26a | 20.54 ± 3.67a | 155.12 ± 4.84b | |||||

| Milk + Strawberry | M | 156.95 ± 3.98b | S | 241.04 ± 2.21b | S | 145.75 ± 22.11b | S | 199.39 ± 2.62b | S |

| E | 119.33 ± 7.99a | 174.46 ± 3.22a | 44.13 ± 9.33a | 147.5 ± 4.57a | |||||

| Milk + GTE | M | 411.32 ± 35.47a | Add | 764.08 ± 4.17b | S | 517.21 ± 45.90b | S | 208.75 ± 0.47a | An |

| E | 473.09 ± 54.06a | 657.53 ± 51.29a | 211.23 ± 22.82a | 511.11 ± 6.05b | |||||

| Milk + BTE | M | 423.84 ± 6.26b | S | 574.23 ± 85.53b | S | 496.35 ± 100.14b | S | 124.33 ± 9.48a | An |

| E | 227.02 ± 24.07a | 333.91 ± 2.13a | 135.14 ± 21.86a | 190.55 ± 5.58b | |||||

| Milk + Espresso | M | 577.02 ± 1.67b | S | 178.76 ± 12.10a | An | 104.21 ± 5.84a | Add | 156.9 ± 4.69a | An |

| E | 214.69 ± 15.18a | 268.71 ± 11.17b | 110.29 ± 2.65a | 178.97 ± 1.42b | |||||

| Cheese + Wine | M | 122.12 ± 1.69a | Add | 209.52 ± 21.97b | S | 107.51 ± 15.21a | Add | 127.82 ± 13.87a | Add |

| E | 118.88 ± 6.70a | 161.94 ± 9.84a | 99.34 ± 26.72a | 134.66 ± 12.36a | |||||

| Jambon + WWB | M | 89.43 ± 3.36b | S | 186.27 ± 26.03b | S | 73.94 ± 14.28a | Add | 89.77 ± 5.49b | S |

| E | 24.8 ± 1.81a | 133.64 ± 17.05a | 92.59 ± 15.94a | 79.9 ± 8.23a | |||||

| Jambon + Cheese | M | 64.51 ± 6.95a | Add | 166.9 ± 23.57a | Add | 93.45 ± 7.58a | Add | 128.25 ± 15.20a | Add |

| E | 53.06 ± 5.34a | 169.23 ± 17.08a | 110.67 ± 7.90a | 128.33 ± 5.39a | |||||

| Jambon + Wine | M | 70.57 ± 10.99a | Add | 176.98 ± 8.87b | S | 86.81 ± 0.42a | An | 102.15 ± 8.88a | Add |

| E | 91.68 ± 21.94a | 129.07 ± 7.15a | 128.33 ± 15.41b | 81.81 ± 4.00a | |||||

Results are expressed as mean ± SD (n = 3). Different letters in the same column of measured (M) and estimated (E) value pair for each combination denote statistically significant differences (P < 0.05) according to student t-test. BC: breakfast cereal, WWB: whole wheat bread, GTE: green tea extract, BTE: black tea extract.

The changes in antioxidant compounds present in the binary combinations of food during digestion might affect the antioxidant interactions between foods. It is known that an antioxidant compound could be a prooxidant depending on its concentration, leading to antagonism in its binary combination. In addition, the presence of transition metals and the lipid fractions in foods, as in the example of flaxseed, hazelnut, and jambon, could be the reason for prooxidation resulting in antagonism in their combinations. In a similar extent with our observation, it was demonstrated that enrichment of the pig's diet with flaxseed increased the lipid oxidation during in vitro digestion of pork meat compared to the control without flaxseed (Martini et al., 2020a, Martini et al., 2020b).

Except for espresso, milk co-digestion with food or beverages transformed the interaction type to the synergism from the antagonism observed before digestion. It was thought that the digestive enzymes in the gastrointestinal tract might break down the protein-phenol complexes by destabilizing the protein structure and let the phenolic compounds released during digestion. Besides, the stabilization of polyphenols by milk proteins and prevention of their oxidation were also believed to be possible by providing a physical trapping for reactive polyphenols, and regeneration of the phenolic compounds by amino acids residues. Lamothe et al. (2014) supported the assertion by showing the increased recovery of green tea polyphenols during digestion due to the presence of dairy products. They reported that the presence of dairy products significantly improved the polyphenol stability in the intestinal phase and increased the antioxidant activity by 29–42% depending on dairy products.

3.4. Effects of food-food interactions on HRSC of the bioaccessible fractions of foods

Table 5 gives the HRSC of foods and their combinations, and the resultant interaction types determined by a statistical comparison of HRSCmeasured with HRSCestimated. As a physiologically relevant reactive oxygen species, hydroxyl radicals generated by Fenton type reaction and their scavenging by the bioaccessible fractions of foods were monitored by ESR. Accordingly, green tea was found to be the most efficient scavenger (936.48 ± 16.64 mmol TE.kg−1) to eliminate hydroxyl radicals. HRSCs of whole wheat bread and breakfast cereal were found to be very lower compared to other foods and beverage extracts, in line with their TACs determined by ABTS·+ scavenging capacity.

Table 5.

Hydroxyl radical scavenging capacity (HRSC) of the bioaccessible fractions of foods and their combinations (HRSCmeasured and HRSCestimated), and the resultant interaction types (S: synergism, An: antagonism, Add: additive).

| Foods | HRSC (mmol TE.kg−1) | Food Combinations | HRSCmeasured (mmol TE.kg−1) | HRSCestimated (mmol TE.kg−1) | Interaction type |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BC | 43.41 ± 1.25 | BC + Flaxseed | 31.04 ± 5.43a | 49.44 ± 1.55b | An |

| WWB | 42.16 ± 2.66 | BC + Hazelnut | 3.97 ± 0.43a | 48.06 ± 2.34b | An |

| Flaxseed | 70.31 ± 1.74 | BC + Milk | 89.58 ± 1.25b | 77.62 ± 1.13a | S |

| Hazelnut | 54.29 ± 2.82 | BC + Strawberry | 76.21 ± 2.49b | 68.03 ± 0.01a | S |

| Milk | 110.58 ± 1.0 | WWB + Flaxseed | 33.87 ± 3.07 | 48.77 ± 4.74 | An |

| Cheese | 110.25 ± 7.48 | WWB + GTE | 62.26 ± 8.24 | 124.15 ± 4.26b | An |

| Jambon | 89.83 ± 2.02 | WWB + BTE | 66.08 ± 4.94b | 49.41 ± 7.26a | S |

| Strawberry | 103.53 ± 1.74 | WWB + Wine | 20.58 ± 8.25a | 33.27 ± 4.88a | Add |

| GTE | 936.48 ± 16.64 | Milk + Flaxseed | 69.4 ± 6.23a | 102.55 ± 1.45b | An |

| BTE | 195.61 ± 49.82 | Milk + Strawberry | 98.88 ± 7.73a | 108.05 ± 1.27a | Add |

| Espresso | 288.79 ± 26.02 | Milk + GTE | 72.39 ± 2.68a | 170.49 ± 2.70b | An |

| Wine | 508.49 ± 12.15 | Milk + BTE | 79.7 ± 3.64a | 112.36 ± 5.80b | An |

| Milk + Espresso | 97.47 ± 6.66a | 133.75 ± 5.64b | An | ||

| Cheese + Wine | 88.00 ± 5.25a | 80.93 ± 4.63a | Add | ||

| Jambon + WWB | 73.22 ± 1.25b | 64.09 ± 2.32a | S | ||

| Jambon + Cheese | 107.76 ± 5.81a | 100.04 ± 4.00a | Add | ||

| Jambon + Wine | 82.02 ± 2.73b | 66.63 ± 9.11a | S |

Results are expressed as mean ± SD (n = 3). Different letters in the same row denote statistically significant differences (P < 0.05) according to student t-test. BC: breakfast cereal, WWB: whole wheat bread, GTE: green tea extract, BTE: black tea extract.

According to the comparison between the HRSCmeasured and HRSCestimated of the bioaccessible fractions of binary combinations, the presence of co-ingested food except breakfast cereal and strawberry resulted in antagonism with milk. It is known that the interactions between antioxidant compounds are mainly concentration dependent. Significant decreases in the antioxidant compounds of green tea and black tea extracts in their bioaccessible fractions might be the reason for their antagonistic interactions with milk although their interactions were recorded as synergism under intestinal conditions, where tea extracts have high TAC. Besides, the reversible hydrophilic and hydrophobic interactions between peptides, proteins, and enzymes with phenolic compounds could create a physical trapping under intestinal conditions and prevent their passing to bioaccessible fraction, providing a lower antioxidant potential than expected from the milk combinations.

Breakfast cereal also interacted antagonistically with hazelnut or flaxseed during hydroxyl radical scavenging under physiological conditions. The prooxidant effect of alpha tocopherol found in breakfast cereal might be the reason for the antagonism, as previously reported by Mohanan et al. (2018). Similarly, antagonism was observed between whole wheat bread and flaxseed. In a similar manner, Kamiloglu et al. (2014) also showed that co-digestion of nuts with fruits caused a decrease in TAC of dialyzed fractions.

4. Conclusion

Foods consumed together in daily diet are known to constitute to the primary sources of natural antioxidant compounds that possibly interact with each other and exert their antioxidant activity synergistically, additively, or antagonistically. From a physiological perspective, foods, after consumption, are subjected to a gastrointestinal digestion process having possible effects on their antioxidant potential. Within this context, the present study evaluated the antioxidant interactions among foods both before and during the digestion of the binary combinations of foods. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first comprehensive study investigating the effects of food-food interactions on TAC considering the different food matrices. According to the results, foods, including polyunsaturated fatty acids and transition metals, as in the examples of seeds and nuts, interacted antagonistically with other foods due to the prooxidant potential of transition metals on lipid rich system. In addition, protein-phenol interactions masking the TACs of phenol rich foods before digestion could stabilize and regenerate the phenolic compounds under the gastrointestinal digestion conditions, providing a synergistic interaction. It was also observed that the intestinal conditions promoting the reaction between antioxidant compounds and the radicals resulted in increases in TACs of foods. In addition, the enzymatic colonic digestion caused the significant increases in TACs of certain foods. These findings are thought to make a noteworthy contribution to both food design and regulation of the daily diet, by providing a basis to increase antioxidant activity in daily diet and new food formulations. This study will be a starting point for further investigations directed to evaluate the interactions between specific food groups.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Ezgi Doğan Cömert: Conceptualization, Methodology, Software, Formal analysis, Validation, Investigation, Data curation, Visualization, Writing – original draft. Vural Gökmen: Conceptualization, Methodology, Resources, Supervision, Project administration, Writing – review & editing.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgement

Authors gratefully acknowledge the infrastructure (electron spin resonance spectrometry) and support provided by Hacettepe University (Project code FBA-2017-14246).

References

- Açar O.C., Gökmen V., Pellegrini N., Fogliano V. Direct evaluation of the total antioxidant capacity of raw and roasted pulses, nuts and seeds. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2009;229:961–969. [Google Scholar]

- Aludatt M.H., Rababah T., Ereifej K., Alli I. Distribution, antioxidant and characterisation of phenolic compounds in soybeans, flaxseed and olives. Food Chem. 2013;139:93–99. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2012.12.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altunkaya A., Becker E.M., Gökmen V., Skibsted L.H. Antioxidant activity of lettuce extract (Lactuca sativa) and synergism with added phenolic antioxidants. Food Chem. 2009;115(1):163–168. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2008.11.082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ao J., Li B. Stability and antioxidative activities of casein peptide fractions during simulated gastrointestinal digestion in vitro: charge properties of peptides affect digestive stability. Food Res. Int. 2013;52(1):334–341. doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2013.03.036. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bandyopadhyay P., Ghosh A.K., Ghosh C. Recent developments on polyphenol-protein interactions: effects on tea and coffee taste, antioxidant properties and the digestive system. Food Funct. 2012;3(6):592–605. doi: 10.1039/c2fo00006g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker E.M., Ntouma G., Skibsted L.H. Synergism and antagonism between quercetin and other chain-breaking antioxidants in lipid systems of increasing structural organisation. Food Chem. 2007;103(4):1288–1296. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2006.10.034. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bermúdez-Soto M.-J., Tomás-Barberán F.-A., García-Conesa M.-T. Stability of polyphenols in chokeberry (Aronia melanocarpa) subjected to in vitro gastric and pancreatic digestion. Food Chem. 2007;102(3):865–874. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2006.06.025. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bourassa P., Côté R., Hutchandani S., Samson G., Tajmir-Riahi H.-A. The effect of milk alpha-casein on the antioxidant activity of tea polyphenols. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B Biol. 2013;128:43–49. doi: 10.1016/j.jphotobiol.2013.07.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Çelik E.E., Gökmen V., Skibsted L.H. Synergism between soluble and dietary fiber bound antioxidants. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2015;63(8):2338–2343. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.5b00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X., Li H., Zhang B., Deng Z. The synergistic and antagonistic antioxidant interactions of dietary phytochemical combinations. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2021:1–20. doi: 10.1080/10408398.2021.1888693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cilla A., Perales S., Lagarda M.J., Barberá R., Clemente G., Farré R. Influence of storage and in vitro gastrointestinal digestion on total antioxidant capacity of fruit beverages. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2011;24(1):87–94. doi: 10.1016/j.jfca.2010.03.029. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cömert E.D., Gökmen V. Antioxidants bound to an insoluble food matrix: their analysis, regeneration behavior, and physiological importance. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2017;16(3) doi: 10.1111/1541-4337.12263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cömert E.D., Gökmen V. Evolution of food antioxidants as a core topic of food science for a century. Food Res. Int. 2018;105 doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2017.10.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delgado-Andrade C., Conde-Aguilera J.A., Haro A., Pastoriza de la Cueva S., Rufián-Henares J.Á. A combined procedure to evaluate the global antioxidant response of bread. J. Cereal. Sci. 2010;52(2):239–246. doi: 10.1016/j.jcs.2010.05.013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Donlao N., Ogawa Y. Impacts of processing conditions on digestive recovery of polyphenolic compounds and stability of the antioxidant activity of green tea infusion during in vitro gastrointestinal digestion. LWT. 2018;89:648–656. doi: 10.1016/j.lwt.2017.11.051. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Halliwell B., Zhao K., Whiteman M. The gastrointestinal tract: a major site of antioxidant action. Free Radic. Res. 2000;33(6):819–830. doi: 10.1080/10715760000301341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herbello-Hermelo P., Lamas J.P., Lores M., Domínguez-González R., Bermejo-Barrera P., Moreda-Piñeiro A. Polyphenol bioavailability in nuts and seeds by an in vitro dialyzability approach. Food Chem. 2018;254:20–25. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2018.01.183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hidalgo M., Sánchez-Moreno C., de Pascual-Teresa S. Flavonoid–flavonoid interaction and its effect on their antioxidant activity. Food Chem. 2010;121(3):691–696. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2009.12.097. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kamiloglu S., Pasli A.A., Ozcelik B., Capanoglu E. Evaluating the in vitro bioaccessibility of phenolics and antioxidant activity during consumption of dried fruits with nuts. LWT. 2014;56(2):284–289. doi: 10.1016/j.lwt.2013.11.040. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ketnawa S., Reginio F.C., Thuengtung S., Ogawa Y. Changes in bioactive compounds and antioxidant activity of plant-based foods by gastrointestinal digestion: a review. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2021:1–22. doi: 10.1080/10408398.2021.1878100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim H.S., Hur S.J. Effects of in vitro human digestion on the antioxidant activity and stability of lycopene and phenolic compounds in pork patties containing dried tomato prepared at different temperatures. J. Food Sci. 2018;83(7):1816–1822. doi: 10.1111/1750-3841.14205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim Y.J., Kim E.H., Hahm K.B. Oxidative stress in inflammation-based gastrointestinal tract diseases: challenges and opportunities. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2012;27(6):1004–1010. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2012.07108.x. PMID: 22413852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamothe S., Azimy N., Bazinet L., Couillard C., Britten M. Interaction of green tea polyphenols with dairy matrices in a simulated gastrointestinal environment. Food Funct. 2014;5(10):2621–2631. doi: 10.1039/C4FO00203B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liguori I., Russo G., Curcio F., Bulli G., Aran L., Della-Morte D., Gargiulo G., Testa G., Cacciatore F., Bonaduce D., Abete P. Oxidative stress, aging, and diseases. Clin. Interv. Aging. 2018;13:757–772. doi: 10.2147/CIA.S158513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lila M.A. In: BT - Anthocyanins: Biosynthesis, Functions, and Applications. Winefield C., Davies K., Gould K., editors. Springer; New York: 2009. Interactions between flavonoids that benefit human health; pp. 306–323. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu R., Xing L., Fu Q., Zhou G., Zhang W. A review of antioxidant peptides derived from meat muscle and by-products. Antioxidants. 2016;5(3):32. doi: 10.3390/antiox5030032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madhujith T., Shahidi F. Optimization of the extraction of antioxidative constituents of six barley cultivars and their antioxidant properties. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2006;54(21):8048–8057. doi: 10.1021/jf061558e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marinova E., Toneva A., Yanishlieva N. Synergistic antioxidant effect of α-tocopherol and myricetin on the autoxidation of triacylglycerols of sunflower oil. Food Chem. 2008;106(2):628–633. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2007.06.022. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Martini S., Conte A., Bottazzi S., Tagliazucchi D. Mediterranean diet vegetable foods protect meat lipids from oxidation during in vitro gastro-intestinal digestion. Int. J. Food Sci. Nutr. 2020;71(4):424–439. doi: 10.1080/09637486.2019.1677570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martini S., Tagliazucchi D., Minelli G., Lo Fiego D. Pietro. Influence of linseed and antioxidant-rich diets in pig nutrition on lipid oxidation during cooking and in vitro digestion of pork. Food Res. Int. 2020;137 doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2020.109528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller H.E., Rigelhof F., Marquart L., Prakash A., Kanter M. Antioxidant content of whole grain breakfast cereals, fruits and vegetables. J. Am. Coll. Nutr. 2000;19(3):312S–319S. doi: 10.1080/07315724.2000.10718966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minekus M., Alminger M., Alvito P., Ballance S., Bohn T., Bourlieu C., Carriere F., Boutrou R., Corredig M., Dupont D., Dufour C., Egger L., Golding M., Karakaya S., Kirkhus B., Le Feunteun S., Lesmes U., Macierzanka A., Mackie A., Brodkorb A. A standardised static in vitro digestion method suitable for food - an international consensus. Food Funct. 2014;5(6):1113–1124. doi: 10.1039/c3fo60702j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohanan A., Nickerson M.T., Ghosh S. Oxidative stability of flaxseed oil: effect of hydrophilic, hydrophobic and intermediate polarity antioxidants. Food Chem. 2018;266:524–533. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2018.05.117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papuc C., Goran G.V., Predescu C.N., Nicorescu V. Mechanisms of oxidative processes in meat and toxicity induced by postprandial degradation products: a review. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2017;16(1):96–123. doi: 10.1111/1541-4337.12241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peluso I., Serafini M. Antioxidants from black and green tea: from dietary modulation of oxidative stress to pharmacological mechanisms. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2017;174(11):1195–1208. doi: 10.1111/bph.13649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perrone D., Farah A., Donangelo C.M. Influence of coffee roasting on the incorporation of phenolic compounds into melanoidins and their relationship with antioxidant activity of the brew. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2012;60(17):4265–4275. doi: 10.1021/jf205388x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phaniendra A., Jestadi D.B., Periyasamy L. Free radicals: properties, sources, targets, and their implication in various diseases. Indian J. Clin. Biochem. 2015;30(1):11–26. doi: 10.1007/s12291-014-0446-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rabetafika H.N., Van Remoortel V., Danthine S., Paquot M., Blecker C. Flaxseed proteins: food uses and health benefits. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2011;46(2):221–228. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2621.2010.02477.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rufián-Henares J.A., Delgado-Andrade C. Effect of digestive process on Maillard reaction indexes and antioxidant properties of breakfast cereals. Food Res. Int. 2009;42(3):394–400. doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2009.01.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Segura-Campos M., Chel-Guerrero L., Betancur-Ancona D., Hernandez-Escalante V.M. Bioavailability of bioactive peptides. Food Rev. Int. 2011;27(3):213–226. doi: 10.1080/87559129.2011.563395. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Serpen A., Gökmen V., Fogliano V. Total antioxidant capacities of raw and cooked meats. Meat Sci. 2012;90(1):60–65. doi: 10.1016/j.meatsci.2011.05.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tagliazucchi D., Helal A., Verzelloni E., Conte A. Bovine milk antioxidant properties: effect of in vitro digestion and identification of antioxidant compounds. Dairy Sci. Technol. 2016;96(5):657–676. doi: 10.1007/s13594-016-0294-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tagliazucchi D., Verzelloni E., Bertolini D., Conte A. In vitro bio-accessibility and antioxidant activity of grape polyphenols. Food Chem. 2010;120(2):599–606. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2009.10.030. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Venkatachalam M., Sathe S.K. Chemical composition of selected edible nut seeds. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2006;54(13):4705–4714. doi: 10.1021/jf0606959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang S., Meckling K.A., Marcone M.F., Kakuda Y., Tsao R. Synergistic, additive, and antagonistic effects of food mixtures on total antioxidant capacities. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2011;59(3):960–968. doi: 10.1021/jf1040977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]