Abstract

Purpose

The current gold standard for chronic endometritis (CE) diagnosis is immunohistochemistry (IHC) for CD-138. However, IHC for CD-138 is not exempt from diagnostic limitations. The aim of our study was to evaluate the reliability and accuracy of MUM-1 IHC, as compared with CD-138.

Methods

This is a multi-centre, retrospective, observational study, which included three tertiary hysteroscopic centres in university teaching hospitals. One hundred ninety-three consecutive women of reproductive age were referred to our hysteroscopy services due to infertility, recurrent miscarriage, abnormal uterine bleeding, endometrial polyps or myomas. All women underwent hysteroscopy plus endometrial biopsy. Endometrial samples were analysed through histology, CD138 and MUM-1 IHC. The primary outcome was to evaluate the diagnostic accuracy of MUM-1 IHC for CE, as compared with CD-138 IHC.

Results

Sensitivity and specificity of CD-138 and MUM-1 IHC were respectively 89.13%, 79.59% versus 93.48% and 85.03%. The overall diagnostic accuracy of MUM-1 and CD-138 IHC were similar (AUC = 0.893 vs AUC = 0.844). The intercorrelation coefficient for single measurements was high between the two techniques (ICC = 0.831, 0.761–0.881 95%CI). However, among CE positive women, MUM-1 allowed the identification of higher number of plasma cells/hpf than CD-138 (6.50 [SD 4.80] vs 5.05 [SD 3.37]; p = 0.017). Additionally, MUM-1 showed a higher inter-observer agreement as compared to CD-138.

Conclusion

IHC for MUM-1 and CD-138 showed a similar accuracy for detecting endometrial stromal plasma cells. Notably, MUM-1 showed higher reliability in the paired comparison of the individual samples than CD-138. Thus, MUM-1 may represent a novel, promising add-on technique for the diagnosis of CE.

Keywords: Chronic endometritis, MUM-1, CD138, Diagnostic accuracy, Plasma cells

Introduction

Chronic endometritis (CE) is a subtle pathology characterized by a persistent inflammatory disorder of the endometrial lining [1, 2]. The pathogenesis of CE seems to be sustained by qualitative and quantitative alteration of endometrial microbioma [3]. Additionally, a new theory about an “impaired inflammatory state of the endometrium (IISE)” at the basis of CE (i.e. involving both infectious and non-infectious factors) was recently formulated [4].

Clinically, CE is commonly overlooked as it is mainly associated with mild and unspecific disturbances, such as abnormal uterine bleeding (AUB), dyspareunia, pelvic discomfort and leucorrhea [5, 6]. Nevertheless, the alterations of endometrial gene expression observed in CE may affect endometrial receptivity, potentially causing female infertility [7]. In this respect, different studies have previously shown that CE is highly prevalent in patients affected by unexplained infertility, repeated embryo implantation failure and recurrent pregnancy loss [8–13]. Even if a causal relationship between CE and reproductive failure is still far to be established, CE may theoretically impair embryo implantation due to cytokine dysregulation, leukocyte infiltration, vascular changes, altered decidualization, autophagy and altered uterine contractility [7, 14].

Diagnosis of CE is challenging for different reasons [3, 6, 9, 12]. Many patients with CE lack symptoms and ultrasound signs are non-specific. The microbial examination is not meaningful as most pathogens are not culturable and, additionally, during endometrial sampling, a certain contamination with cervical and vaginal bacteria cannot be prevented. CE may be diagnosed by fluid hysteroscopy based on the detection of specific endometrial signs such as focal or diffuse hyperemia, stromal edema and micropolyps [3, 9]. However, the diagnostic accuracy of hysteroscopy is dependent on operator expertise [15].

Therefore, histopathological identification of plasma cells in endometrial biopsy samples is considered the current diagnostic gold standard for CE [16, 17]. Identification of plasma cells by conventional tissue staining alone is difficult. Plasmacytes typically have a large cell body, high nuclei/cytoplasm ratio, basophilic cytoplasm and nuclei with heterochromatin rearrangement referred to as “spoke-wheel” or “clock-face” pattern [18]. These morphological features of plasmacytes are not always evident under microscopic examination, as plasma cells often exhibit an appearance similar to stromal fibroblasts and mononuclear leukocytes that reside in the human endometrium [15].

Immunohistochemistry for the plasmacyte marker CD-138 (also known as syndecan-1, a transmembrane type heparan sulphate proteoglycan) is currently the most reliable and time-saving diagnostic method for CE [19–21]. It has been shown that CD-138 immunostaining is superior to conventional tissue staining using methyl green pyronin, haematoxylin and eosin in CE detection (odds ratio 2.8; sensitivity, 100% versus 75%; specificity, 100% versus 65%) with less inter-observer (96% versus 68%) and intra-observer variability (93% versus 47%) [22].

Although CD-138 immunostaining is validated for CE diagnosis, it should be used with caution. Other than plasmacytes, also endometrial epithelial cells constitutively express CD-138 on their plasma membrane, potentially leading to a false-positive diagnosis of CE [18, 22]. Consequently, new insights on the staining techniques for plasma cells are warranted.

With regard to this scenario, multiple myeloma antigen 1 (MUM-1) is a protein which is normally expressed in plasma cells, activated B and T cells [23, 24]. Studies have shown that MUM-1 protein is required at several stages of B-cell development, including in the differentiation of mature B cell into antibody-secreting plasma cells [25, 26]. In other athors’ experiences, MUM-1 immunohistochemistry has been successfully used for the diagnosis of lymphomas and plasma cell tumours [27, 28]. Given the need for additional staining techniques in CE, we ought to test the usefulness of MUM-1 immunohistochemistry in the identification of endometrial plasma cells.

The aim of this multi-centre study was to evaluate the accuracy and reliability of MUM-1 immunohistochemistry, as compared with CD-138 immunohistochemistry, for the diagnosis of CE.

Materials and methods

Study design

This was a retrospective multi-centre study conducted at three centres (hysteroscopy units of the University of Bari, Padua and Barcelona) from August 2017 to January 2020. The study received local ethical approval. All patients gave their written consent for the anonymous use of their clinical data for research purposes, as per practice in our centre. The study was reported following the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) guidelines [29].

Participants

We included patients referred to our hysteroscopy services due to infertility (i.e. the failure to achieve pregnancy after 12 months or more of unprotected sexual intercourse), recurrent miscarriage (i.e. two or more consecutive miscarriages), abnormal uterine bleeding and suspicion of endometrial polyps or myomas.

Exclusion criteria were post-menopausal age, diagnosis of placental remnants, endometrial cancer or atypical hyperplasia, previous diagnosis of tuberculosis, hormonal or steroid treatment within three months or during the study period, any antibiotic treatments within 3 months or during the study period.

Hysteroscopy and endometrial sampling

All women underwent diagnostic mini-hysteroscopy in the follicular phase of the menstrual cycle. Mini-hysteroscopy was performed using a lens-based 2.7-mm OD mini-telescope and 105° angle of visual field equipped with a 3.5-mm OD single-flow diagnostic sheath (Karl Storz, Tuttlingen, Germany). In order to minimize the risk of iatrogenic contamination of the endometrial cavity, all examinations were performed after placing a vaginal speculum and cleaning the external uterine ostium with gauze soaked in iodine solution.

Saline was employed to distend the uterine cavity at a pressure generated by a simple drop from a bag suspended 1 m above the patient. A 300-W light source with a xenon bulb and a HD digital camera (Karl Storz, Tuttlingen, Germany) were used.

The exploration of the uterine cavity consisted of a panoramic view of the cavity followed by a thorough evaluation of the endometrial mucosa as previously described [15]. Diagnosis of CE at hysteroscopy was based on criteria previously published (micropolyps, focal/diffuse hyperemia, “strawberry aspect”, hemorrhagic spots, stromal edema). All hysteroscopies were performed by one author for each centre (A.V, E.C. and S.H.). After hysteroscopy, an endometrial biopsy using a 3 mm Novak’s curette connected to a 20-ml syringe was performed. The tissue samples obtained were placed in formalin for histological and immunohistochemical examinations.

Histology and immunohistochemistry

Endometrial samples were fixed in neutral formalin and later embedded in paraffin. Five microsections were stained with hematoxylin-eosin. Five-micrometre sections were cut and incubated, separately, with mouse anti-human monoclonal CD-138 and MUM-1 antibodies. The clones of anti-CD-138 and anti-MUM-1 monoclonal antibodies used in our study were MI15 Cell Marque (Biocare Medical, Concord, CA) and MRQ-8 Cell Marque (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, USA). CD138-positive plasma cells were identified in the stroma. The biopsies were graded as “negative” for CE if there was less than one plasma cell identified per 20 high-power fields (HPFs) and “positive” when there were one or more plasma cells identified per 20 HPFs, according to published criteria [2, 5]. Initially, histopathological and immunohistochemical analyses were completed by a single pathologist for each centre and served for the assessment of the primary and tertiary endpoints of our study. In a subset of patients, the immunohistochemical analyses with CD-138 and MUM-1 were repeated by two additional pathologists, who were unaware of their respective evaluations. The results of their observations were included in the inter-observer agreement analyses.

Data collection

Clinical data were collected in our clinical registers by two Authors for each centre. Data included patients’ general features (age, BMI, parity), medical history (general health status, pharmacological treatments), the indication for hysteroscopy and the results of each hysteroscopic, histological and immunohistochemical examination with CD-138 and MUM-1. In cases of missing data, the same authors contacted patients by telephone to obtain complete information.

Study outcomes

The primary outcome was to evaluate the accuracy of MUM-1 immunohistochemistry, as compared with CD-138 immunohistochemistry for the diagnosis of CE. The secondary outcome was to assess the inter-observer reliability of MUM-1 and CD-138 immunohistochemistry for the detection of plasma cells. The tertiary outcome was to compare the number of plasma cells identified through using MUM-1 versus CD-138 immunohistochemistry.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed by using SPSS v.22.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Continuous variables were reported as mean with standard deviation (SD), whereas qualitative variables were presented as absolute frequencies and percentages. Comparisons between categorical variables were tested by using contingency tables and the chi-square test or Fisher’s test when necessary. Comparisons between normally distributed continuous variables were made by using Student’s t-test. A value of p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves were elaborated to assess the performance of CD-138 and MUM-1 immunohistochemistry in order to detect CE (by using the combination of histological and hysteroscopic diagnoses as reference standard). The agreement was statistically assessed between the two immunohistochemical techniques (i.e. CD-138 and MUM-1 immunostaining), as well as between the evaluation of three pathologists for each single technique (i.e. separately for CD-138 and MUM-1 immunostaining). The measure of inter-observer agreement was expressed as the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC). An ICC of 0.20 was considered as a poor agreement, 0.21–0.40 fair agreement, 0.41–0.60 moderate agreement and 0.61–0.80 substantial agreement, while a value of 0.81–1.00 was considered as perfect agreement. The ICC was calculated by using a linear mixed model.

Results

Descriptive results

The demographic characteristics of the study population are displayed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics of patients included in the study. Data expressed as mean + SD or absolute numbers and percentages

| Age, years (mean ± SD) | 39.12 ± 4.55 |

|---|---|

| Parity (mean ± SD) | 0.86 ± 1.21 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 23.85 ± 3.17 |

| Indications for hysteroscopy, n (%) | |

| Infertility | 92 (47.67%) |

| Repeated miscarriage | 37 (19.17%) |

| Abnormal uterine bleeding | 25 (12.95%) |

| Suspicion of uterine polyps or myomas | 39 (20.21%) |

| CE at hysteroscopy, n (%) | 76 (39.40%) |

| CE at histology, n (%) | 54 (28.00%) |

| E at immunohistochemistry with CD-138, n (%) | 71 (36.80%) |

| CE at immunohistochemistry with MUM-1, n (%) | 65 (33.70%) |

Values are given as mean ± standard deviation or number (%) as appropriate; CE, chronic endometritis

Two hundred sixty-one patients were initially assessed for eligibility. After the exclusion of 68 women, a total number of 193 patients were included in the study. Of these, n = 92 (47.67%) suffered from infertility and n = 37 (19.17%) had a history of recurrent miscarriages. The remaining patients were referred to our centres due to abnormal uterine bleeding (n = 25, 12.95%) or the suspicion of endometrial polyps or myomas (n = 39, 20.21%).

Hysteroscopy identified CE in 76 women (39.40%), while histology diagnosed CE in 54 women (28.00%). Cumulatively, hysteroscopy and histology diagnosed CE in 84 patients (43.52%), of whom n = 46 were positive to both techniques (23.83%). CD-138 immunostaining was positive for CE in 71 cases (36.80%) and MUM-1 immunostaining was positive for CE in 65 cases (33.70%). The total number of patients in whom CD-138 or MUM-1 immunostaining was positive was 76 (39.40%). Both CD-138 and MUM-1 immunohistochemistry revealed the presence of plasma cells in n = 60 patients (31.09%). At least one technique among histology, hysteroscopy, CD-138 and MUM-1 immunohistochemistry was positive in 97 cases (50.26%), with a high prevalence in women with recurrent miscarriage (n = 26/37, 70.27%) and infertility (n = 53/92, 57.61%). Notably, results of CD-138 and MUM-1 immunohistochemistry did not match in 16 cases (Table 2).

Table 2.

2 × 2 table. Immunohistochemical staining (IHC) with MUM-1 as compared with CD-138

| CD-138 IHC | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CE positive | CE negative | Total | ||

| MUM-1 IHC | CE positive | 60 | 5 | 65 |

| CE negative | 11 | 117 | 128 | |

| Total | 71 | 122 | 193 | |

CD-138 and MUM-1: diagnostic accuracy and interclass correlation

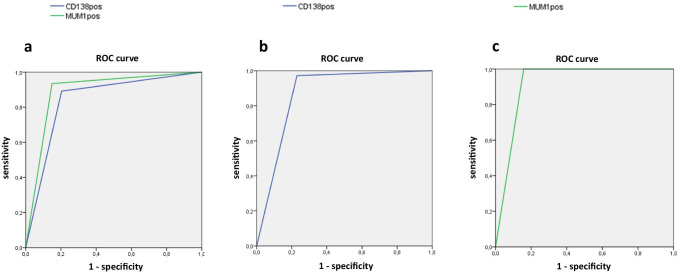

Using hysteroscopy plus histology as the reference standard, sensitivity and specificity of CD-138 and MUM-1 immunohistochemistry were respectively 89.13%, 79.59% versus 93.48% and 85.03%. The overall diagnostic accuracy of MUM-1 and CD-138 immunohistochemistry were similar (AUC = 0.893 vs AUC = 0.844; Figure 1a).

Fig. 1.

a–c ROC analyses: a diagnostic accuracy of MUM-1 and CD-138 immunohistochemistry for chronic endometritis using histology plus hysteroscopy as a reference standard; b diagnostic accuracy of CD-138 immunohistochemistry for chronic endometritis using a combination of MUM-1 immunohistochemistry, histology and hysteroscopy as a reference standard; c diagnostic accuracy of MUM-1 immunohistochemistry for chronic endometritis using a combination of CD-138 immunohistochemistry, histology and hysteroscopy as a reference standard

Using a combination of hysteroscopy, histology and CD-138 immunohistochemistry as the reference standard, sensitivity and specificity of MUM-1 immunohistochemistry were 100% and 84.21%. The overall diagnostic accuracy of MUM-1 immunohistochemistry was AUC = 0.921 (Figure 1b). Conversely, using hysteroscopy plus histology plus MUM-1 immunohistochemistry as the reference standard, sensitivity and specificity of CD-138 immunohistochemistry were 95.35% and 80.00%. The overall diagnostic accuracy of CD-138 immunohistochemistry was AUC = 0.877 (Figure 1c). The intercorrelation coefficient for single measurements between CD-138 and MUM-1 immunohistochemistry was high (ICC = 0.831, 0.761–0.881, 95%CI). Importantly, MUM-1 immunostaining showed similar but higher closeness of agreement with histology (ICC = 0.800 [0.743–0.846, 95%CI]) and hysteroscopy (ICC = 0.592 [0.492–0.677, 95%CI]) when compared to those observed for CD-138 immunohistochemistry (ICC = 0.696 [0.615–0.762, 95%CI] and ICC = 0.463 [0.344–0.567, 95%CI] with histology and hysteroscopy, respectively).

Inter-observer reliability of CD-138 and MUM-1 immunohistochemistry

The inter-observer variability between three pathologists was assessed for 86 patients. Although the agreement was fair with respect to both techniques, MUM-1 immunohistochemistry showed higher inter-observer agreement than CD-138 immunohistochemistry (ICC = 0.902 [0.843–0.943, 95% CI] versus ICC = 0.809 [0.712–0.881, 95% CI]).

Number of plasma cells detected by CD-138 and MUM-1 immunochemistry

Among those women in whom MUM-1 and CD-138 immunohistochemistry were both positive for CE, MUM-1 immunohistochemistry allowed the detection of a higher number of plasma cells/20 hpf than CD-138 immunohistochemistry (6.50 [SD 4.80] vs 5.05 [SD 3.37]; p = 0.017).

Analysis of cases where CD-138 and MUM-1 immunohistochemistry provided conflicting results

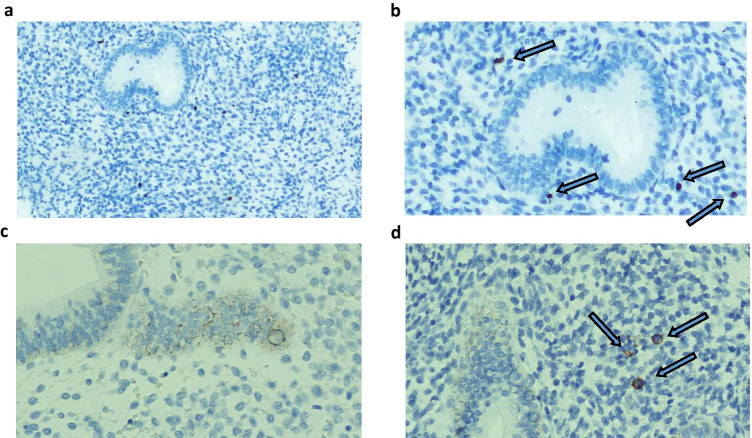

The results of CD-138 and MUM-1 staining did not match in 16 cases (Table 2), of which in 5 women CE was revealed by MUM-1staining but not by CD-138 staining. In a single patient, both histology and hysteroscopy were negative. In the remaining cases, at least one technique between histology and hysteroscopy was positive. After the re-evaluation of the samples, two patients were considered as false positive CE due to misinterpretation of marked lymphocytes. Contrastingly, in the 11 cases for which CD-138 showed immunoreactivity but MUM-1 did not, both hysteroscopy and histology were negative (Figure 2). After the samples were re-evaluated, nine patients were considered as false positive CE due to the intense reaction of epithelial cells.

Fig. 2.

a–d MUM-1 (a, b) and CD-138 stains (c, d) demonstrate the presence of plasma cells within the endometrial stroma (blue arrows). Note the endometrial glandular/surface reaction to CD-138 antibodies (2c) but not to MUM-1 antibodies (2a)

Discussion

The current diagnosis of CE relies on the histopathological examination of endometrial biopsy specimens, where the presence of endometrial stromal plasma cells represents the main diagnostic marker. The recent introduction of CD-138 immunohistochemistry has considerably improved the accuracy of the microscopic examination of the endometria in women with CE, thus overcoming the limitations of traditional staining techniques [21, 22]. In this respect, Bayer-Garner and Korourian reported that the diagnosis rate of CE by traditional histopathology was considerably lower than that by CD-138 immunohistochemistry (15% vs 42%, p < 0.05) in endometrial curettage samples [30]. Additionally, in a recent study on 100 endometrial preparations (of which 80 were from patients with CE and 20 controls), Kitaya et al. found a higher inter-observer agreement for the detection of endometrial stromal plasma cells using immunohistochemistry for CD138 (ICC 0.968–0.976) compared to the conventional histopathological method (0.687–0.771) [25]. The gap in favour of CD-138 staining was further increased when inexperienced pathologists were involved in the analysis, suggesting a better reproducibility of the immunohistochemical technique. As per the authors’ admission, the major concern in the immunohistochemical staining with CD-138 was that anti-human CD138 antibodies detected not only stromal plasmacytes but also endometrial glandular/surface epithelial cells which constitutively express this proteoglycan, potentially leading to false-positive diagnoses of CE. For this reason, the identification of further staining techniques for overcoming diagnostic uncertainty inherent to CE would be important. In this study, we aimed to evaluate the potential usefulness of MUM-1, a protein which is constitutively expressed in plasmacytes, as a novel immunohistochemical marker for endometrial stromal plasma cells in women with CE.

Main findings

Our study included a total number of 193 reproductive-aged patients for whom hysteroscopy plus endometrial biopsy was indicated due to infertility, recurrent miscarriages, abnormal uterine bleeding or the suspicion of polyps or myomas. For all patients, endometrial preparations with CD-138 and MUM-1 staining were realized alongside traditional histology.

By using all the techniques (hysteroscopy, histology, CD-138 and MUM-1 immunohistochemistry), our study revealed a high prevalence of CE in the entire sample of patients, especially in those women suffering from reproductive disorders. These findings were in line with our previous data on women suffering from infertility, repeated embryo implantation failure and recurrent miscarriage [4, 8, 31]. On the other hand, when compared to our recent study on women with intrauterine pathologies [5], this present study found a lower prevalence of CE. However, the two studies were different in terms of research design and population characteristics.

Interestingly, in this study, the accuracy for CE diagnosis of MUM-1 immunohistochemistry was similar to CD-138 staining (AUC = 0.893 vs AUC = 0.844 by using a combination of hysteroscopy and histology as reference standard), and the closeness of agreement between the two techniques was high (ICC = 0.831, 0.761–0.881, 95%CI). Notably, sensitivity and specificity of MUM-1 were slightly higher than CD-138 immunohistochemistry (93.48% and 85.03% vs 89.13% and 79.59%, respectively). These findings were further confirmed by individual matching of CE diagnoses achieved by the two immunohistochemical techniques with those obtained by hysteroscopy and histology (ICC = 0.800 and ICC = 0.592 vs ICC = 0.696 and ICC = 0.463 for MUM-1 and CD-138, respectively). These important results deserve consideration concerning the peculiar characteristics of the techniques under comparison. As previously mentioned, CD-138 antigen is constitutively expressed not only by plasma cells, but also by the epithelial cells of the endometrial glandular surface [18, 22]. Therefore, epithelial cells can appear as marked elements in the endometrial staining with anti-CD-138 monoclonal antibodies, generating a focal or diffuse background reaction. In such cases, a correct diagnosis is based on cell morphology-based criteria. Nevertheless, we must stress that some endometrial sections with CD-138 staining may be misleading (e.g. isolated or fragmented glandular epithelial cells in the sample) and potentially result in misidentification of epithelial cells as stromal plasma cells. Unlike CD-138, MUM-1 is not expressed by epithelial glandular cells but mainly by lymphoid cells, especially plasmacytes and activated B/T lymphocytes [23, 24]. Therefore, this latter staining technique does not display a background reaction, but it should be noted that it marks also other lymphoid lineage cells that can be found in the endometrial stroma. Here, once again differential diagnosis is achieved through morphological criteria, where plasma cells display eccentric nuclei with clock-face chromatin and abundant cytoplasm. Thereby, the inner characteristics of the techniques employed in our study may potentially explain their imperfect agreement in terms of CE diagnoses. Additionally, the lack of background reaction with MUM-1 staining (but not with CD-138 staining) may justify our findings about a higher inter-observer agreement between pathologists, as well as the higher mean number of plasma cells counted in paired samples by using MUM-1 immunohistochemistry. In our opinion, these specific differences between CD-138 and MUM-1 immunohistochemistry emphasize the potential advantages of using both techniques contextually in CE. However, we need to stress that our results, although exciting, need further confirmation in other institutional settings.

Study limitations

To the best of our knowledge, this was the first study investigating the accuracy and reliability of MUM-1 immunohistochemistry for the diagnosis of CE. Originality, rigorous methodology, the multi-centre setting of the study and the relatively large sample size were the points of strength.

The retrospective design was the main point of weakness in our study. Additionally, the choice to make CE diagnosis based on the smallest addressable unit (i.e. one or more plasma cells per 20 hpfs) may have dramatically increased the absolute number of CE in our series, as well as it may have expanded any differences in diagnostic accuracy between comparators. In this regard, recent studies raised important questions about the clinical meaningfulness of < 5 endometrial plasma cells per high-power field in women suffering from infertility. However, these results are still not conclusive and a precise cutoff of plasma cells for performing CE diagnosis has not been established yet [32–34].

Conclusions

Immunohistochemistry for MUM-1 and CD-138 showed similar accuracy for detecting endometrial stromal plasma cells. Notably, MUM-1 staining showed higher reliability in the paired comparison of the individual samples than CD-138 staining. Therefore, MUM-1 immunohistochemistry may represent a novel, promising add-on technique for improving the diagnostic process in women with CE.

Acknowledgements

University of Bari, University of Padua, University of Barcelona.

Availability of data and material

All data are available upon request.

Declarations

Ethics approval

The study received local ethical approval.

Consent to participate

All patients gave their written consent for the procedure.

Consent for publication

All patients gave their written consent for the anonymous use of their clinical data for research purposes.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Kitaya K, Takeuchi T, Mizuta S, Matsubayashi H, Ishikawa T. Endometritis: new time, new concepts. Fertil Steril. 2018;110:344–350. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2018.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Park HJ, Kim YS, Yoon TK, Lee WS. Chronic endometritis and infertility. Clin Exp Reprod Med. 2016;43:185–192. doi: 10.5653/cerm.2016.43.4.185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Moreno I, Cicinelli E, Garcia-Grau I, Gonzalez-Monfort M, Bau D, Vilella F, et al. The diagnosis of chronic endometritis in infertile asymptomatic women: a comparative study of histology, microbial cultures, hysteroscopy, and molecular microbiology. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2018;218(6):602.e1–602.e16. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2018.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Drizi A, Djokovic D, Laganà AS, van Herendael B. Impaired inflammatory state of the endometrium: a multifaceted approach to endometrial inflammation. Current insights and future directions. Prz Menopauzalny. 2020;19(2):90–100. doi: 10.5114/pm.2020.97863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kimura F, Takebayashi A, Ishida M, Nakamura A, Kitazawa J, Morimune A, Hirata K, Takahashi A, Tsuji S, Takashima A, Amano T, Tsuji S, Ono T, Kaku S, Kasahara K, Moritani S, Kushima R, Murakami T. Review: Chronic endometritis and its effect on reproduction. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2019;45(5):951–960. doi: 10.1111/jog.13937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cicinelli E, Bettocchi S, de Ziegler D, Loizzi V, Cormio G, Marinaccio M, Trojano G, Crupano FM, Francescato R, Vitagliano A, Resta L. Chronic endometritis, a common disease hidden behind endometrial polyps in premenopausal women: first evidence from a case-control study. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2019;26(7):1346–1350. doi: 10.1016/j.jmig.2019.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Buzzaccarini G, Vitagliano A, Andrisani A, Santarsiero CM, Cicinelli R, Nardelli C, Ambrosini G, Cicinelli E. Chronic endometritis and altered embryo implantation: a unified pathophysiological theory from a literature systematic review. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2020;37(12):2897–2911. doi: 10.1007/s10815-020-01955-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kitaya K. Prevalence of chronic endometritis in recurrent miscarriages. Fertil Steril. 2011;95:1156–8. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2010.09.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cicinelli E, Matteo M, Trojano G, Mitola PC, Tinelli R, Vitagliano A, et al. Chronic endometritis in patients with unexplained infertility: prevalence and effects of antibiotic treatment on spontaneous conception. Am J Reprod Immunol 2017. 10.1111/aji.12782. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Vitagliano A, Saccardi C, Noventa M, Di Spiezio Sardo A, Saccone G, Cicinelli E, Pizzi S, Andrisani A, Litta PS. Effects of chronic endometritis therapy on in vitro fertilization outcome in women with repeated implantation failure: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Fertil Steril. 2018;110(1):103–112.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2018.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McQueen DB, Bernardi LA, Stephenson MD. Chronic endometritis in women with recurrent early pregnancy loss and/or fetal demise. Fertil Steril. 2014;101:1026–30. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2013.12.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cicinelli E, Matteo M, Tinelli R, Lepera A, Alfonso R, Indraccolo U, et al. Prevalence of chronic endometritis in repeated unexplained implantation failure and the IVF success rate after antibiotic therapy. Hum Reprod. 2015;30:323–30. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deu292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Johnston-MacAnanny EB, Hartnett J, Engmann LL, Nulsen JC, Sanders MM, Benadiva CA. Chronic endometritis is a frequent finding in women with recurrent implantation failure after in vitro fertilization. Fertil Steril. 2010;93:437–441. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2008.12.131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Puente E, Alonso L, Laganà AS, Ghezzi F, Casarin J, Carugno J. Chronic endometritis: old problem, novel insights and future challenges. Int J Fertil Steril. 2020;13(4):250–256. doi: 10.22074/ijfs.2020.5779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cicinelli E, Vitagliano A, Kumar A, Lasmar RB, Bettocchi S, Haimovich S, International Working Group for Standardization of Chronic Endometritis Diagnosis Unified diagnostic criteria for chronic endometritis at fluid hysteroscopy: proposal and reliability evaluation through an international randomized-controlled observer study. Fertil Steril. 2019;112(1):162–173.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2019.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Li Y, Xu S, Yu S, Huang C, Lin S, Chen W, Mo M, Lian R, Diao L, Ding L, Zeng Y. Diagnosis of chronic endometritis: How many CD138+ cells/HPF in endometrial stroma affect pregnancy outcome of infertile women? Am J Reprod Immunol. 2020;85(5):e13369. 10.1111/aji.13369. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.Chen YQ, Fang RL, Luo YN, Luo CQ. Analysis of the diagnostic value of CD138 for chronic endometritis, the risk factors for the pathogenesis of chronic endometritis and the effect of chronic endometritis on pregnancy: a cohort study. BMC Womens Health. 2016;16(1):60. doi: 10.1186/s12905-016-0341-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Parks RN, Kim CJ, Al-Safi ZA, Armstrong AA, Zore T, Moatamed NA. Multiple myeloma 1 transcription factor is superior to CD138 as a marker of plasma cells in endometrium. Int J Surg Pathol. 2019;27(4):372–379. doi: 10.1177/1066896918814307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kannar V, Lingaiah HK, Sunita V. Evaluation of endometrium for chronic endometritis by using syndecan-1 in abnormal uterine bleeding. J Lab Physicians. 2012;15(4):69–73. doi: 10.4103/0974-2727.105584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kitaya K, Yasuo T. Immunohistochemistrical and clinicopathological characterization of chronic endometritis. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2011;66:410–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0897.2011.01051.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kitaya K, Tada Y, Taguchi S, Funabiki M, Hayashi T, Nakamura Y. Local mononuclear cell infiltrates in infertile patients with endometrial macropolyps versus micropolyps. Hum Reprod. 2012;27:3474–80. doi: 10.1093/humrep/des323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kitaya K, Yasuo T. Inter-observer and intra-observer variability in immunohistochemical detection of endometrial stromal plasmacytes in chronic endometritis. Exp Ther Med. 2013;5(2):485–488. doi: 10.3892/etm.2012.824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Falini B, Fizzotti M, Pucciarini A, Bigerna B, Marafioti T, Gambacorta M, Pacini R, Alunni C, Natali-Tanci L, Ugolini B, Sebastiani C, Cattoretti G, Pileri S, Dalla-Favera R, Stein H. A monoclonal antibody (MUM1p) detects expression of the MUM1/IRF4 protein in a subset of germinal center B cells, plasma cells, and activated T cells. Blood. 2000;95(6):2084–92. doi: 10.1182/blood.V95.6.2084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wasco MJ, Fullen D, Su L, Ma L. The expression of MUM1 in cutaneous T-cell lymphoproliferative disorders. Hum Pathol. 2008;39(4):557–63. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2007.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gaidano G, Carbone A. MUM1: a step ahead toward the understanding of lymphoma histogenesis. Leukemia. 2000;14(4):563–6. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2401748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Valsami S, Pappa V, Rontogianni D, Kontsioti F, Papageorgiou E, Dervenoulas J, Karmiris T, Papageorgiou S, Harhalakis N, Xiros N, Nikiforakis E, Economopoulos T. A clinicopathological study of B-cell differentiation markers and transcription factors in classical Hodgkin’s lymphoma: a potential prognostic role of MUM1/IRF4. Haematologica. 2007;92(10):1343–50. doi: 10.3324/haematol.11523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tsuboi K, Iida S, Inagaki H, Kato M, Hayami Y, Hanamura I, Miura K, Harada S, Kikuchi M, Komatsu H, Banno S, Wakita A, Nakamura S, Eimoto T, Ueda R. MUM1/IRF4 expression as a frequent event in mature lymphoid malignancies. Leukemia. 2000;14(3):449–56. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2401696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Naresh KN. MUM1 expression dichotomises follicular lymphoma into predominantly, MUM1-negative low-grade and MUM1-positive high-grade subtypes. Haematologica. 2007;92(2):267–8. doi: 10.3324/haematol.10682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gøtzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP, STROBE Initiative Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. BMJ. 2007;335(7624):806–8. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39335.541782.AD. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bayer-Garner IB, Korourian S. Plasma cells in chronic endometritis are easily identified when stained with syndecan-1. Mod Pathol. 2001;14:877–879. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3880405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cicinelli E, Matteo M, Tinelli R, Pinto V, Marinaccio M, Indraccolo U, De Ziegler D, Resta L. Chronic endometritis due to common bacteria is prevalent in women with recurrent miscarriage as confirmed by improved pregnancy outcome after antibiotic treatment. Reprod Sci. 2014;21(5):640–7. doi: 10.1177/1933719113508817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cicinelli E, Cicinelli R, Vitagliano A. Consistent evidence on the detrimental role of severe chronic endometritis on in vitro fertilization outcome and the reproductive improvement after antibiotic therapy: on the other hand, mild chronic endometritis appears a more intricate matter. Fertil Steril. 2021;116(2):345–346. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2021.06.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Song D, He Y, Wang Y, Liu Z, Xia E, Huang X, Xiao Y, Li TC. Impact of antibiotic therapy on the rate of negative test results for chronic endometritis: a prospective randomized control trial. Fertil Steril. 2021;115(6):1549–1556. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2020.12.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cicinelli E, Resta L, Loizzi V, Pinto V, Santarsiero C, Cicinelli R, Greco P, Vitagliano A. Antibiotic therapy versus no treatment for chronic endometritis: a case-control study. Fertil Steril. 2021;115(6):1541–1548. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2021.01.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All data are available upon request.