Abstract

We performed immunohistochemical staining on the nontumorous renal tissue of 45 patients with renal cancer but without progressive multifocal encephalopathy using JCV-specific antibody. For one patient we found positive staining of the nuclei of the renal collecting ducts. Immunoelectron microscopic examination of the positive cell nuclei revealed electron-dense polyomavirus-like particles.

JC virus (JCV) is a member of the polyomavirus group of viruses and is the causative agent of progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy (PML) (18). JCV infects humans mostly at a young age without obvious clinical manifestations and persists in the kidney tissue (6, 15, 19, 21). Although the renal infection with JCV is not associated with clinically apparent tissue damage, PML is a devastating central nervous system disease that mostly occurs in immunocompromised patients (5, 18, 22). JCV has been detected in urine and renal tissue not only of PML and immunocompromised patients but also those of the immunocompetent general population (6, 8, 10, 12, 13, 14). Although there have been many reports of studies of JCV in urine and kidney tissue by DNA hybridization and/or PCR (6, 4, 7), histological examinations of the JCV replication site in the kidney are scarce. Dörries and ter Meulen (9) reported on the detection of the JCV genome in the cells of renal collecting ducts in a PML patient by in situ hybridization; however, renal JCV localization by immunohistochemistry (IHC) and immunoelectron microscopy (IEM) has not been reported. Recently, we developed a JCV-specific antibody (JCAb1) that is effective with formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tissue (3). Here we report, for the first time, on the localization of JCV in the kidney of an immunocompetent patient without PML by IHC and IEM with a nontumorous part of the renal tissue resected for renal cancer.

Kidney tissues resected for renal cancer from 45 patients were obtained at the Department of Urology, Branch Hospital, Faculty of Medicine, the University of Tokyo, and the Department of Urology, Mitui Memorial Hospital. The kidney tissue collection included kidney tissues from 32 patients previously reported on for the detection of renal JCV DNA (21). No patients were undergoing immunosuppressive or anticancer drug therapy. The tissues were obtained from 33 males and 12 females (average age, 65.1 years). Urine and/or frozen renal tissues were collected, stored, and submitted for JCV DNA detection by PCR as reported previously (21). Among the 45 patients, both urine samples and kidney tissues were available for 38. For four patients, only urine samples were available. For three patients, only kidney tissues were available. JCV DNA was detected in the kidney tissues of 20 of 41 patients and in the urine samples of 19 of 42 patients from whom urine was available. The tumor tissues were negative for JCV DNA by PCR (data not shown).

Tissues for histological examination were fixed immediately after nephrectomy in 10% formalin and were embedded in paraffin. One block containing nontumorous kidney tissue was selected from each patient, and 4-μm-thick sections were made.

JCAb1, a JCV-specific antibody used throughout this work, reacts with a decapeptide of the VP1 protein of JCV and has been shown to not cross-react with the closely related BKV or simian virus 40 (SV40) polyomaviruses. The specificity of JCAb1 has been confirmed by positive staining of JCV-infected IMR32 cells, negative staining of BKV-infected 293 cells, and negative staining of SV40-infected IMR32 cells. The specificity has also been confirmed by positive staining of the typical JCV-infected oligodendrocytes and astrocytes of formalin-fixed paraffin sections of brain tissues from patients with PML (3; unpublished data). Immunohistochemical staining has been performed as reported previously with the peroxidase LSAB kit (DAKO), with visualization with diaminobenzidine (DAB) (3). Formalin-fixed paraffin sections of brain tissues from patients with PML were used as positive controls throughout this experiment. For the negative controls, JCAb1 was replaced by normal rabbit serum.

For examination by IEM, paraffin sections were processed in the same way as they were for light microscopic IHC through the DAB coloring step, but the microwave treatment was skipped to avoid tissue damage. After visualization with DAB, the sections were processed as described previously (2).

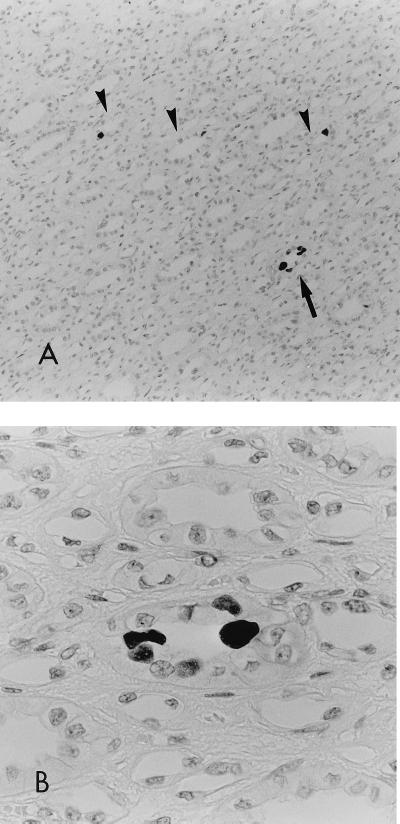

IHC-positive staining was obtained for tissue from one patient (patient 881073), whose kidney tissue was positive for JCV DNA but whose urine was not available for examination. The patient had a nephrectomy on 25 April 1988, when he was 51 years old. His postoperative course has been uneventful, with no signs or symptoms of either PML or a recurrence of renal cell carcinoma until the time of submission of the manuscript of this report. In the kidney tissue of patient 881073, strong staining was observed in the lining epithelial cells of the collecting ducts in a single area of the renal papilla of the section (Fig. 1A and B), which shows the focal nature of the intrarenal distribution of JCV infection. Granular positive staining was recognized in the nuclei of these cells. Some cells with strongly positive nuclei showed faint cytoplasmic staining. A single to several positive cells were found in each positive duct, but these were not associated with degenerative or necrotic changes. Some of the positive cells appeared to be protruding into the tubular lumen, with the positive nuclei of the cells protruding into the luminal side. This might reflect a process of exfoliation into the tubular lumen (Fig. 1B). No specific staining was observed in the other segments of the renal tubules, in the glomerulus, in the interstitial kidney tissues, or in the tumorous tissues adjacent to the normal kidney tissue. The discrepancy between the number of PCR-positive patients (n = 20) and the number of IHC-positive patients (n = 1) may be due to (i) the relative low sensitivity of the IHC method compared with that of PCR, (ii) viral latency (the presence of viral DNA without VP1 antigen expression), and (iii) a focal distribution of cells with viral replication.

FIG. 1.

IHC of the renal medulla. The tissue was counterstained with hematoxylin. (A) The arrowheads and the arrow indicate positive collecting ducts. The ducts indicated by arrowheads each contain one positive cell. Magnification, ×120. (B) High-power view of the positive duct indicated by an arrow in panel A. Note the two strongly positive (black in this photo) nuclei and the three weakly positive nuclei that can be seen to be protruding into the lumen. Magnification, ×480.

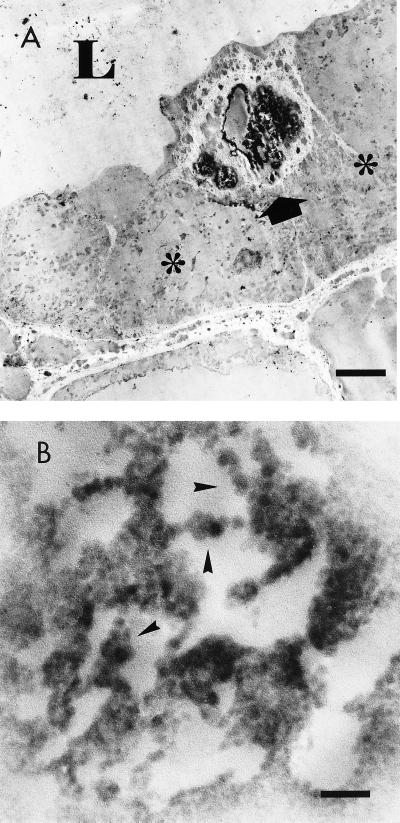

IEM revealed that the collecting ducts had positive epithelial cells, which concurred with our light microscopic findings. The electron-dense staining was localized in the nuclei of ductal cells. Some of these positive cells were located in the luminal side and were lying on the negative cells (Fig. 2A). JCV replication may affect the cellular adhesion to the basement membrane and/or to the adjacent cells, or JCV replication may be facilitated in the exfoliating cells. The cells loaded with high viral contents may exfoliate into the lumen and may serve as a source of the urinary JCV (7, 12, 24). Although most of the IEM-positive electron-dense material was of a particular or a granular nature, the virus-like nature of the particles was clear only in some limited areas. These virus-like particles measured 35 to 45 nm in diameter (16, 17, 20) and aligned in beads or clusters (Fig. 2B), which were compatible with polyomavirus particles. Filamentous forms were not observed. Cytoplasmic virus-like particles were not readily discernible, although the cytoplasmic structures were poorly preserved.

FIG. 2.

IEM of the positive duct. The tissue was counterstained with uranyl acetate. (A) Low-power view of the positive collecting duct. Arrow, a positive cell; L, the lumen; ∗, a negative cell. Note that the positive cell protrudes into the lumen and overlies the negative cells. Bar, 4 μm. Magnification, ×2,600. (B) High-power view of the positive nuclei in panel A. Arrowheads indicate representative areas containing electron-dense polyomavirus-like particles. Bar, 200 nm. Magnification, ×50,000.

No inflammatory cell infiltration was observed in the area containing JCV-positive collecting ducts either by IHC or by IEM. Although Dörries and ter Meulen (9) also found no inflammatory cell infiltration in the area with ISH-positive cells in a patient with PML, the implication suggested by our findings is different. In typical patients with PML, the lack of inflammatory reactions in central nervous system lesions has been ascribed to the presence of generalized immunodeficiency, including specific cellular immunity against JCV (1, 11, 23). By the same token, the renal reaction may lack a cellular immune response in patients with PML. On the other hand, our findings suggest a lack of an apparent local cellular immune response against the JCV-infected tubular epithelial cells even in the immunocompetent patient. This kind of virus-host interaction may closely be related to mechanisms of persistent infection of JCV in renal tissue.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Y. Yogo, Institute of Medical Science, the University of Tokyo, for helpful suggestions.

REFERENCES

- 1.Achim C L, Wiley C A. Expression of major histocompatibility complex antigens in the brains of patients with progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 1992;51:257–263. doi: 10.1097/00005072-199205000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aoki N, Gerber M A, Thung S N, Chen M-L, Christman J K, Price P M, Flordellis C S, Acs G. Ultrastructural studies of fibroblasts transfected with hepatitis B virus DNA. Hepatology. 1984;4:84–89. doi: 10.1002/hep.1840040115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aoki N, Mori M, Kato K, Sakamoto Y, Noda K, Tajima M, Shimada H. Antibody against synthetic multiple antigen peptides (MAP) of JC virus capsid protein (VP1) without cross reaction to BK virus: a diagnostic tool for progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy. Neurosci Lett. 1996;205:111–114. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(96)12389-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Arthur R R, Dagostin S, Shah K V. Detection of BK virus and JC virus in urine and brain tissue by the polymerase chain reaction. J Clin Microbiol. 1989;27:1174–1179. doi: 10.1128/jcm.27.6.1174-1179.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Berger J R, Kaszovitz B, Post M J D, Dickinson G. Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy associated with human immunodeficiency virus infection. A review of the literature with a report of sixteen cases. Ann Intern Med. 1987;107:78–87. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-107-1-78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chesters P M, Heritage J, McCance D J. Persistence of DNA sequence of BK virus and JC virus in normal human tissues and in diseased tissues. J Infect Dis. 1983;147:676–684. doi: 10.1093/infdis/147.4.676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cobb J J, Wickenden C, Snell M E, Hulme B, Malcom A D B, Coleman D V. Use of hybridot assay to screen for BK and JC polyomaviruses in non-immunosuppressed patients. J Clin Pathol. 1987;40:777–781. doi: 10.1136/jcp.40.7.777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Coleman D V, Wolfendale M R, Daniel R A, Dhanjal N K, Gardner S D, Gibson P E, Field A M. A prospective study of human polyomavirus infection in pregnancy. J Infect Dis. 1980;142:1–8. doi: 10.1093/infdis/142.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dörries K, ter Meulen V. Progressive multifocal leucoencephalopathy: detection of papovavirus JC in kidney tissue. J Med Virol. 1983;11:307–317. doi: 10.1002/jmv.1890110406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Grinnell B W, Padgett B L, Walker D L. Distribution of nonintegrated DNA from JC papovavirus in organs of patients with progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy. J Infect Dis. 1983;147:669–675. doi: 10.1093/infdis/147.4.669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hair L S, Nuovo G, Powers J M, Sisti M B, Britton C B, Miller J R. Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy in patients with human immunodeficiency virus. Hum Pathol. 1992;23:663–667. doi: 10.1016/0046-8177(92)90322-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hogan T F, Padgett B L, Walker D L, Borden E C, McBain J A. Rapid detection and identification of JC virus and BK virus in human urine by using immunofluorescence microscopy. J Clin Microbiol. 1980;11:178–183. doi: 10.1128/jcm.11.2.178-183.1980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kitamura T, Aso Y, Kuniyoshi N, Hara K, Yogo Y. High incidence of urinary JC virus excretion in nonimmunosuppressed older patients. J Infect Dis. 1990;161:1128–1133. doi: 10.1093/infdis/161.6.1128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kitamura T, Kunitake T, Guo J, Tominaga T, Kawabe K, Yogo Y. Transmission of the human polyomavirus JC virus occurs both within the family and outside the family. J Clin Microbiol. 1994;32:2359–2363. doi: 10.1128/jcm.32.10.2359-2363.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kitamura T, Sugimoto C, Kato A, Ebihara H, Suzuki M, Taguchi F, Kawabe K, Yogo Y. Persistent JC virus (JCV) infection is demonstrated by continuous shedding of the same JCV strains. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:1255–1257. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.5.1255-1257.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mázló M, Tariska I. Morphological demonstration of the first phase of polyomavirus replication in oligodendroglia cells of human brain in progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy (PML) Acta Neuropathol (Berlin) 1980;49:133–143. doi: 10.1007/BF00690753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Muller J, Watanabe I. Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy. Am J Clin Pathol. 1967;47:114–123. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/47.2.114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Padgett B L, Walker D L, ZuRhein G M, Eckroade R J, Dessel B H. Cultivation of papova-like virus from human brain with progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy. Lancet. 1971;i:1257–1260. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(71)91777-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Padgett B L, Walker D L. Prevalance of antibodies in human sera against JC virus, an isolate from a case of progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy. J Infect Dis. 1973;127:467–470. doi: 10.1093/infdis/127.4.467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shimada H, Noda K, Mori M, Aoki N, Tajima M, Kato K. Papovavirus detection by electron microscopy in the brain of an elderly patients without overt progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy. Virchows Arch. 1994;424:569–572. doi: 10.1007/BF00191445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tominaga T, Yogo Y, Kitamura T, Aso Y. Persistence of archetypal JC virus DNA in normal renal tissue derived from tumor-bearing patients. Virology. 1992;186:736–741. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(92)90040-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Walker D L, Padgett B L. Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy. In: Frankel-Conrat H, Wegner R R, editors. Comprehensive virology. Vol. 18. New York, N.Y: Plenum Press; 1983. pp. 161–193. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Willoughby E, Price R W, Padgett B L, Walker D L, Dupont B. Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy (PML): in vitro cell-mediated immune responses to mitogens and JC viruses. Neurology. 1980;30:256–262. doi: 10.1212/wnl.30.3.256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yogo Y, Kitamura T, Sugimoto C, Ueki T, Aso Y, Hara K, Taguchi F. Isolation of a possible archetypal JC virus DNA sequence from nonimmunocompromised individuals. J Virol. 1990;64:3139–3143. doi: 10.1128/jvi.64.6.3139-3143.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]