Abstract

In a context of worldwide emergence of resistance among Streptococcus pneumoniae strains, early detection of strains with decreased susceptibility to β-lactam antibiotics is important for clinicians. If the 1-μg oxacillin disk diffusion test is used as described by the National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards, no interpretation is available for strains showing zone sizes of ≤19 mm, and there is presently no disk diffusion test available for screening cephalosporin resistance. The zones obtained by the diffusion method by using the 1-μg oxacillin disk were compared with penicillin MICs for 1,116 clinical strains and with ceftriaxone MICs for 695 of these strains. Among the 342 strains with growth up to the 1-μg oxacillin disk margin, none were susceptible (MIC, ≤0.06 μg/ml), 62 had intermediate resistance (MIC, 0.12 to 1.0 μg/ml), and 280 were resistant (MIC, ≥2.0 μg/ml) to penicillin. For ceftriaxone, among 98 strains with no zone of inhibition in response to oxacillin, 68 had intermediate resistance (MIC, 1.0 μg/ml), and 22 were resistant (MIC, ≥2.0 μg/ml). To optimize the use of the disk diffusion method, we propose that the absence of a zone of inhibition around the 1-μg oxacillin disk be regarded as an indicator of nonsusceptibility to penicillin and ceftriaxone and recommend that such strains be reported as nonsusceptible to these antimicrobial agents, pending the results of a MIC quantitation method.

The emergence of resistance to β-lactam antibiotics in clinical isolates of Streptococcus pneumoniae has been reported throughout the world with increasing frequency (1, 8, 11, 12, 21, 25, 31). Because of the consequences of β-lactam resistance to the clinical response to antimicrobial therapy and the possible need to modify such a therapy based on susceptibility results, early detection of strains with decreased susceptibility to these antibiotics is important (20, 24). The diffusion method with a 1-μg oxacillin disk is currently recommended by the National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards (NCCLS) (22, 23) as an effective screening method for the detection of penicillin-resistant pneumococci and is commonly used by clinical laboratories. Although many studies have been done with disks containing ceftriaxone, cefotaxime, cefixime, ceftizoxime, cefuroxime, and loracarbef, there is presently no disk diffusion test available for the screening of cephalosporin resistance (2, 4, 5, 14, 15, 27). The recommended interpretative zone criteria for the detection of penicillin susceptibility with the 1-μg oxacillin disk is a zone size of ≥20 mm. No interpretation is available for zone sizes of ≤19 mm, because strains of pneumococci with this characteristic can be either sensitive, intermediately resistant, or resistant to penicillin (30). In this situation, determination of the strain susceptibility to penicillin by a quantitative method is indicated. The 1-μg oxacillin test is regarded as very sensitive for detection of penicillin resistance, but of low specificity. This study reports observations concerning the relationship between the absence of a growth inhibition zone around the 1-μg oxacillin disk and the susceptibility of S. pneumoniae to penicillin and ceftriaxone. It also reassesses the value of the oxacillin disk test, not only as a predictor of penicillin susceptibility, but also as a tool to rapidly detect decreased susceptibility to penicillin and ceftriaxone.

Isolates were sent to our laboratory for susceptibility testing or as part of a multicenter surveillance study of invasive S. pneumoniae infections in the province of Quebec (17). Between January 1995 and December 1996, strains (n = 1,116) were isolated from normally sterile body fluids (63%) and respiratory tract sources (37%).

Susceptibility methods were performed as outlined by the NCCLS (22, 23). Disk diffusion tests were performed on Mueller-Hinton agar supplemented with 5% defibrinated sheep blood, and test samples were incubated for 20 to 24 h at 35°C in a 5 to 7% CO2 atmosphere. Oxacillin disks were purchased from Oxoid (Unipath, Ontario, Canada). Broth microdilution tests were carried out with an inoculum prepared from an overnight growth on blood agar plates and adjusted to achieve approximately 5 × 105 CFU/ml. MICs were recorded after 20 to 24 h of incubation at 35°C in ambient air. Twofold dilutions of benzylpenicillin (32 to 0.03 μg/ml) of ceftriaxone (32 to 0.03 μg/ml) were performed with cation-adjusted Mueller-Hinton broth supplemented with 2 to 5% lysed horse blood. Antimicrobial powders were purchased from Sigma Chemical Co. (St. Louis, Mo.). S. pneumoniae ATCC 49619 was used as a control throughout the investigation and included with each batch of diffusion and microdilution tests. Results were interpreted according to NCCLS recommendations.

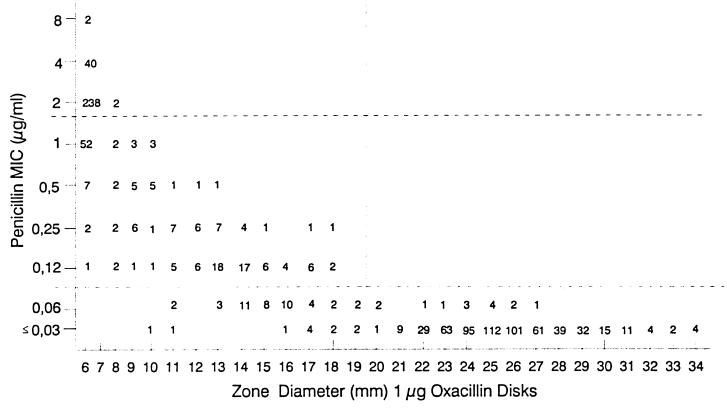

Figure 1 is a scattergram comparing oxacillin zone diameters to penicillin MICs for 1,116 strains. As expected, all strains (n = 592) showing a zone size of ≥20 mm were found susceptible (MIC, ≤0.06 μg/ml) to penicillin by the microdilution method. Among a total of 645 strains found susceptible by microdilution, 53 (8.2%) yielded oxacillin zone sizes of ≤19 mm and would be misclassified as nonsusceptible on the basis of the disk test. For the non-penicillin-susceptible strains (MIC, ≥0.12 μg/ml), all 189 intermediately resistant (MIC, 0.1 to 1.0 μg/ml) and all 282 resistant (MIC, ≥2.0 μg/ml) strains had oxacillin zone diameters of ≤19 mm. However, more interestingly, among the 342 strains with growth up to the disk margin (zone diameter = disk diameter = 6 mm), none were susceptible to penicillin: 62 and 280, respectively, were intermediately resistant and resistant to penicillin (Table 1). The absence of a zone of growth inhibition around the oxacillin disk had positive predictive values of 82% for resistance to penicillin (MIC, ≥2 μg/ml) and 100% for nonsusceptibility (MIC, ≥0.12 μg/ml). In Quebec, the prevalence of penicillin resistance found in our prospective surveillance program in 1996 was 6.9%, while the prevalence of nonsusceptibility was 9.8% (17). Taking into account these prevalence rates, the new positive predictive values for resistance as well as nonsusceptibility to penicillin were 87.6 and 100%, respectively.

FIG. 1.

Scattergram comparing penicillin MICs to zones of inhibition around a 1-μg oxacillin disk. A total of 1,116 S. pneumoniae isolates were tested.

TABLE 1.

Distribution of 1,116 strains by MICs of penicillin and growth inhibition zone diameter around 1-μg oxacillin disk

| Inhibition zone diam (mm) around 1-μg oxacillin disk | No. of isolates inhibited by penicillin MIC (μg/ml) of:

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| ≤0.06 | 0.12–1.0 | ≥2.0 | |

| 6 | 0 | 62 | 280 |

| 7–19 | 53 | 127 | 2 |

| ≥20 | 592 | 0 | 0 |

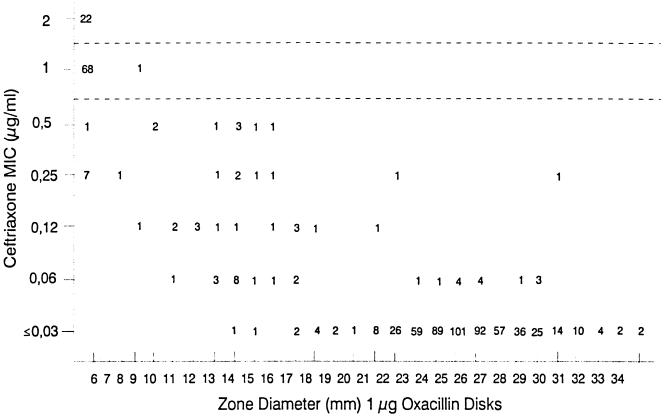

Among the 1,116 strains tested by disk diffusion, 695 were also tested for ceftriaxone susceptibility by broth microdilution. Figure 2 is a scattergram comparing oxacillin zone diameters with ceftriaxone MICs. Among the 98 strains with no zone diameter of inhibition in response to oxacillin, 68 (69.4%) were intermediately resistant (MIC, 1 μg/ml) and 22 (22.4%) were resistant (MIC, ≥2.0 μg/ml) to ceftriaxone. The positive predictive value was 85%, taking into account the observed prevalence of nonsusceptibility to ceftriaxone (MIC, ≥1.0 μg/ml) established at 7.1% in our surveillance program. We also observed that among strains tested with penicillin and ceftriaxone, 86 were found resistant (MIC, ≥2.0 μg/ml) to penicillin, and only 1 of them was susceptible to ceftriaxone (MIC, 0.5 μg/ml). The ceftriaxone MICs for 63 and 22 of the remaining strains, respectively, were 1.0 (intermediate resistance) and 2.0 μg/ml (resistant).

FIG. 2.

Scattergram comparing ceftriaxone MICs to zones of inhibition around a 1-μg oxacillin disk. A total of 695 S. pneumoniae isolates were tested.

All strains were tested along with the quality control strain, S. pneumoniae ATCC 49619 (23). Results obtained with this strain were always within the recommended MIC limits of penicillin (n = 147) and ceftriaxone (n = 104). For the disk diffusion method, concordance was 98%; in two occasions among 96 tests, the zone diameters were out of the expected range. Clinical strains belonging to these two batches were retested.

In Quebec, during the last 10 years, the prevalence of pneumococci nonsusceptible to penicillin (MIC, ≥0.12 μg/ml) rose from 1.3% to 9.8%, and the resistance rate (strains for which MICs were ≥2.0 μg/ml) increased from 0% to 6.9% (16, 17). The impact of this resistance on the treatment of severe pneumococcal infections is serious (8, 11, 20, 21). In the microbiology laboratories, the disk diffusion method with the 1-μg oxacillin disk is largely used in the screening of penicillin nonsusceptibility. Presently, there is no disk diffusion method accepted for the detection of broad-spectrum cephalosporin resistance, because minor error rates of more than 15% have been reported (18) for cefotaxime and ceftriaxone. As published previously (10, 18, 30) and confirmed by this study, a zone of growth inhibition of 20 mm or more around the 1-μg oxacillin disk is always predictive of susceptibility to penicillin. Similarly to what was previously reported by Doern et al. (10) and Jorgensen et al. (18), we observed some strains fully penicillin sensitive with an oxacillin zone size of ≤19 mm. The limitations of the oxacillin diffusion test are well documented by the NCCLS. Unfortunately, MIC determinations for strains showing zone sizes of ≤19 mm introduce a delay of at least 1 day in reporting the final result. For laboratories with sufficient technical resources, Doern et al. (10) recently recommended that MIC tests be performed directly, at least for strains isolated from cerebrospinal fluid. The NCCLS recommends testing of pneumococcal isolates from blood and the central nervous system (CNS) by using a MIC method, since reliable disk diffusion tests with agents such as ceftriaxone and cefotaxime do not yet exist (23). Unfortunately, the necessary technical resources are not always available on-site. Our study shows that the absence of a zone around the 1-μg oxacillin disk is highly predictive of penicillin and ceftriaxone nonsusceptibility. The results obtained by Doern et al. (10) and Barry et al. (4) were similar to ours. These studies presented scattergrams comparing MICs of penicillin or cefixime to zone inhibitions around a 1-μg oxacillin disk and showed that 99 and 98% of pneumococci with no zone of inhibition in response to oxacillin were nonsusceptible to penicillin, and 99% of them were also nonsusceptible to cefixime. The oxacillin disk test was also useful in predicting nonsusceptibility to cephalosporins when strains grew up to the margin of the disk. Unfortunately, discrimination between intermediate susceptibility and resistance cannot be achieved with enough confidence to be of any use, even with other β-lactam disks.

Penicillin remains the antibiotic of choice for treatment of infections caused by susceptible strains of S. pneumoniae. A high dosage is recommended for treatment of meningitis and other infections of the CNS. Penicillin at a higher dosage is recommended for pneumococci with intermediate susceptibility to penicillin in non-CNS infections, whereas for meningitis, other antimicrobial agents should be used, because many reports of penicillin failure with even moderately resistant strains have been published. Obviously, penicillin is not an option for any CNS infection with pneumococci showing resistance to penicillin. For the treatment of severe non-CNS infections with resistant strains, many experts recommend another antimicrobial agent (6, 7, 9, 13, 19, 25, 26).

Studies have shown that an increase in MICs of penicillin is usually accompanied by increases in MICs of other β-lactams (3, 28, 29). The extremely high rate of decreased ceftriaxone susceptibility among our penicillin-resistant strains is disturbing, because this antimicrobial agent or cefotaxime is part of the antimicrobial regimen for the treatment of meningitis caused by these strains.

As recommended by the NCCLS, MIC determinations are indicated for strains with a zone inhibition of ≤19 mm with oxacillin. For pneumococcal meningitis, immediate MIC testing is certainly a legitimate option. However, for the majority of other infections caused by S. pneumoniae, the 1-μg oxacillin disk screening test, due mainly to its simplicity and cost-effectiveness, remains an attractive method. We propose that strains with growth up to the margin of the oxacillin disk be reported as nonsusceptible to penicillin and ceftriaxone pending MIC results. This would be of particular interest to small institutions which have to rely on reference laboratories for MIC testing, further delaying the presentation of final results. Performance of MIC testing of such strains should be dictated by the severity of patient infection. In hospitals with a very high prevalence of penicillin resistance, immediate MIC testing of penicillin and broad-spectrum cephalosporins, by the dilution or E-test method, for all or the majority of pneumococci is an option to be considered.

Acknowledgments

We thank Martial Demers and François Robillard for technical assistance. We are grateful to Gilles Delage for helpful comments on the manuscript. Finally, we thank Lucie Carrière for secretarial assistance.

REFERENCES

- 1.Baquero F. Pneumococcal resistance to β-lactam antibiotics: a global geographic overview. Microb Drug Resist. 1995;1:115–120. doi: 10.1089/mdr.1995.1.115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barry A L, Brown S D, Novick W J. Criteria for testing the susceptibility of Streptococcus pneumoniae to cefotaxime and its desacetyl metabolite using 1 μg or 30 μg cefotaxime disks. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 1995;14:724–726. doi: 10.1007/BF01690885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barry A L, Brown S D, Novik W J. In vitro activities of cefotaxime, ceftriaxone, ceftazidime, cefpirome, and penicillin against Streptococcus pneumoniae isolates. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1995;39:2193–2196. doi: 10.1128/aac.39.10.2193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barry A L, Fuchs P C. Methods for predicting susceptibility of Streptococcus pneumoniae to cefixime. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:1031–1033. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.4.1031-1033.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barry A L, Fuchs P C. Surrogate disks for predicting cefotaxime and ceftriaxone susceptibilities of Streptococcus pneumoniae. J Clin Microbiol. 1996;34:2609–2612. doi: 10.1128/jcm.34.10.2609-2612.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bartlett J G, Breiman R F, Mandel L A, File T M. Community-acquired pneumonia in adults: guidelines for management. Clin Infect Dis. 1998;26:811–838. doi: 10.1086/513953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bradley J S, Scheld W M. The challenge of penicillin-resistant Streptococcus pneumoniae meningitidis: current antibiotic therapy in the 1990s. Clin Infect Dis. 1997;24:S213–S221. doi: 10.1093/clinids/24.supplement_2.s213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Butler J C, Hofmann J, Cetron M S, Elliott J A, Facklam R R, Breiman R F the Pneumococcal Sentinel Surveillance Working Group. The continued emergence of drug-resistant Streptococcus pneumoniae in the United States: an update from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention pneumococcal sentinel surveillance system. J Infect Dis. 1996;174:986–993. doi: 10.1093/infdis/174.5.986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Committee on Infectious Diseases. Therapy for children with invasive pneumococcal infections. Pediatrics. 1997;99:289–299. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Doern G V, Brueggemann A B, Pierce G. Assessment of the oxacillin disk screening test for determining penicillin resistance in Streptococcus pneumoniae. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 1997;16:311–313. doi: 10.1007/BF01695637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Doern G V, Brueggemann A B, Preston Holley H, Jr, Rauch A M. Antimicrobial resistance of Streptococcus pneumoniae recovered from outpatients in the United States during the winter months of 1994 to 1995: results of a 30-center national surveillance study. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1996;40:1208–1213. doi: 10.1128/aac.40.5.1208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Feldman C, Klugman K. Pneumococcal infections. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 1997;10:109–115. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Friedland I R, McCracken G H., Jr Management of infections caused by antibiotic-resistant Streptococcus pneumoniae. N Engl J Med. 1994;331:377–382. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199408113310607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Friedland I R, Shelton S, McCracken G H., Jr Screening for cephalosporin-resistant Streptococcus pneumoniae with the Kirby-Bauer disk susceptibility test. J Clin Microbiol. 1993;31:1619–1621. doi: 10.1128/jcm.31.6.1619-1621.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Goldstein F W, Kitzis M D, Acard J F. Screening for extended-spectrum cephalosporin resistance in Streptococcus pneumoniae. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1994;34:1076–1077. doi: 10.1093/jac/34.6.1076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jetté L P, Lamothe F The Pneumococcus Study Group. Surveillance of invasive Streptococcus pneumoniae infection in Quebec, Canada, from 1984 to 1986: serotype distribution, antimicrobial susceptibility, and clinical characteristics. J Clin Microbiol. 1989;27:1–5. doi: 10.1128/jcm.27.1.1-5.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jetté L P, Ringuette L The Pneumococcus Study Group. Abstracts of the 37th Interscience Conference on Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. Washington, D.C: American Society for Microbiology; 1997. Surveillance program of invasive Streptococcus pneumoniae strains in the province of Québec, abstr. E-116; p. 134. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jorgensen J H, Swenson J M, Tenover F C, Ferraro M J, Hindler J A, Murray P R. Development of interpretive criteria and quality control limits for broth microdilution and disk diffusion antimicrobial susceptibility testing of Streptococcus pneumoniae. J Clin Microbiol. 1994;32:2448–2459. doi: 10.1128/jcm.32.10.2448-2459.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Klugman K P. Epidemiology, control, and treatment of multiresistant pneumococci. Drugs. 1996;52:42–46. doi: 10.2165/00003495-199600522-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Koornhof H J, Klugman K P. Evolution of extended spectrum cephalosporin resistance in the pneumococcus. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1997;39:837–842. doi: 10.1093/jac/39.6.837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lovgren M, Spika J S, Talbot J A. Invasive Streptococcus pneumoniae infections: serotype distribution and antimicrobial resistance in Canada, 1992–1995. Can Med Assoc J. 1998;158:327–331. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards. Performance standards for antimicrobial disk susceptibility tests. 6th ed. Approved standard M2-A6. Villanova, Pa: National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 23.National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards. Methods for dilution antimicrobial susceptibility tests for bacteria that grow aerobically. 4th ed. Approved standard M7-A4. Villanova, Pa: National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pacheco T R, Cooper C K, Hardy D J, Betts R F, Bonnez W. Failure of cefotaxime treatment in an adult with Streptococcus pneumoniae meningitidis. Am J Med. 1997;102:303–305. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9343(99)80271-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pallares R, Linares J, Vadillo M, Cabellos C, Manresa F, Viladrich P F, Martin R, Gudiol F. Resistance to penicillin and cephalosporin and mortality from severe pneumococcal pneumonia in Barcelona, Spain. N Engl J Med. 1995;333:474–479. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199508243330802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Quagliarello V J, Scheld W M. Treatment of bacterial meningitidis. N Engl J Med. 1997;336:708–716. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199703063361007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schutze G E, Lewno M J, Mason E O., Jr Use of ceftizoxime screening for the detection of cephalosporin-resistant pneumococci. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 1997;27:99–101. doi: 10.1016/s0732-8893(96)00221-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sifaoui F, Kitzis M-D, Gutmann L. In vitro selection of one-step mutants of Streptococcus pneumoniae resistant to different oral β-lactam antibiotics is associated with alterations of PBP2x. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1996;40:152–156. doi: 10.1128/aac.40.1.152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Spangler S K, Jacobs M R, Appelbaum P C. Susceptibilities of 177 penicillin-susceptible and -resistant pneumococci to FK 037, cefpirome, cefepime, ceftriaxone, cefotaxime, ceftazidime, imipenem, biapenem, meropenem, and vancomycin. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1994;38:898–900. doi: 10.1128/aac.38.4.898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Swenson J M, Hill B C, Thornsberry C. Screening pneumococci for penicillin resistance. J Clin Microbiol. 1986;24:749–752. doi: 10.1128/jcm.24.5.749-752.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tomasz A. Antibiotic resistance in Streptococcus pneumoniae. Clin Infect Dis. 1997;24:S85–S88. doi: 10.1093/clinids/24.supplement_1.s85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]