Abstract

N 6‐methyladenosine (m6A) mRNA modification represents the most widespread form of internal modifications in eukaryotic mRNAs. In the model plant Arabidopsis thaliana, those known methyltransferases mainly deposit m6A at their target transcripts near the stop codon or in the 3′ untranslated region. Here, it is reported that FIONA1 (FIO1), a human METTL16 ortholog, acts as a hitherto unknown m6A methyltransferase that determines m6A modifications at over 2000 Arabidopsis transcripts predominantly in the coding region. Mutants of FIO1 show a decrease in global m6A mRNA methylation levels and an early‐flowering phenotype. Nanopore direct RNA sequencing reveals that FIO1 is required for establishing appropriate levels of m6A preferentially in the coding sequences of a subset of protein‐coding transcripts, which is associated with changes in transcript abundance and alternative polyadenylation. It is further demonstrated that FIO1‐mediated m6A methylation determines the mRNA abundance of a central flowering integrator SUPPRESSOR OF OVEREXPRESSION OF CONSTANS 1 (SOC1) and its upstream regulators, thus preventing premature flowering. The findings reveal that FIO1 acts as a unique m6A methyltransferase that mainly modifies the coding regions of transcripts, which underlies the key developmental transition from vegetative to reproductive growth in plants.

Keywords: Arabidopsis, FIO1, flowering, m6A, m6A writers

This work uncovers the function of FIONA1 as a unique m6A methyltransferase that mainly modifies the coding regions of transcripts, including those flowering‐related transcripts, to determine the transition from vegetative to reproductive development in plants. This study provides novel insights into understanding of m6A landscape, the associated new players, and their biological functions in plants.

1. Introduction

N 6‐methyladenosine (m6A), the most prevalent internal modification in mRNAs found in many eukaryotes, has emerged as a key regulatory mechanism to control gene expression. m6A modifications could serve as key switches on mRNA metabolism through affecting splicing, stability, alternative polyadenylation, secondary structure, nuclear export, and translation.[ 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 ] Transcriptome‐wide profiling of m6A modifications is thus fundamental for decoding the genome and can be mapped with the next generation sequencing, such as the antibody‐based m6A‐seq and m6A‐CLIP approaches,[ 5 , 6 ] and the third generation sequencing by Oxford nanopore technology.[ 7 ] Notably, nanopore technology that is able to directly sequence native full‐length RNA molecules overcomes the limitations of next generation sequencing that is based on short‐read cDNA sequencing and demands the conversion of RNA to cDNA.[ 8 , 9 ] In nanopore direct RNA sequencing, RNA sequences can be identified by the magnitudes of electric intensity across the nanopore surface when RNA passes the pore. RNA modifications cause shifts in the intensity levels so that the modified bases can be computationally identified at the single‐base resolution.[ 8 , 9 , 10 , 11 ]

m6A is a reversible modification and is dynamically regulated by the concerted cooperation of methyltransferases (writers), demethylases (erasers), and m6A binding protein (readers) that install, remove, and interpret m6A, respectively. In Arabidopsis thaliana, m6A methylation is deposited by a multicomponent methyltransferase complex containing mRNA adenosine methylase (MTA), MTB, FKBP12 INTERACTING PROTEIN 37KD (FIP37), VIRILIZER (VIR), and HAKAI.[ 12 , 13 , 14 , 15 ] This methyltransferase complex methylates thousands of transcripts mainly at regions near the stop codon and in the 3′ untranslated region (3′ UTR), and preferentially in the RRACH (R = A/G; H = A/C/U) motif.[ 9 , 13 ] Disruption of the component genes of the m6A methyltransferase complex, including MTA, FIP37, and VIR, results in greatly reduced (≈80–90% reduction), but not completely abolished m6A modifications.[ 12 , 13 , 16 ] Moreover, a transcriptome‐wide mapping of m6A sites in fip37 mutants (fip37‐4 LEC1:FIP37) has revealed that loss of function of FIP37 mainly affects the m6A peaks near the stop codon and 3′ UTR, but has less impact on those in the coding sequence (CDS) and 5′ UTR.[ 13 ] These findings indicate the presence of other unknown m6A methyltransferase(s) in Arabidopsis.

In this study, we show that FIONA1 (FIO1) acts as a hitherto unknown m6A methyltransferase in Arabidopsis. FIO1 is a nucleus‐localized protein[ 17 ] and orthologous to the human METTL16 that installs m6A on diverse RNA molecules, such as U6 small nuclear RNA (snRNA), the S‐adenosylmethionine (SAM) synthetase MAT2A pre‐mRNA, and possibly other RNAs.[ 18 , 19 , 20 ] Both U6 snRNA and MTA2A contain a conserved sequence, UACm 6 AGAGAA, required for METTL16‐mediated methylation. Here, we show that FIO1 functions as an m6A methyltransferase that is responsible for establishing appropriate levels of m6A modifications on a subset of protein‐coding transcripts mainly in the CDS in Arabidopsis. Disruption of FIO1 results in early flowering and a mild decrease in global m6A levels. Nanopore direct RNA sequencing uncovers a total of 3459 high‐confidence hypomethylated m6A sites in 2068 protein‐coding genes, including the key flowering time integrator SUPPRESSOR OF OVEREXPRESSION OF CONSTANS 1 (SOC1) and its upstream genes. Our findings reveal the role of FIO1 as a novel m6A methyltransferase that underlies the control of the floral transition in plants.

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Disruption of FIO1 Results in a Mild Reduction in Global mRNA m6A Levels

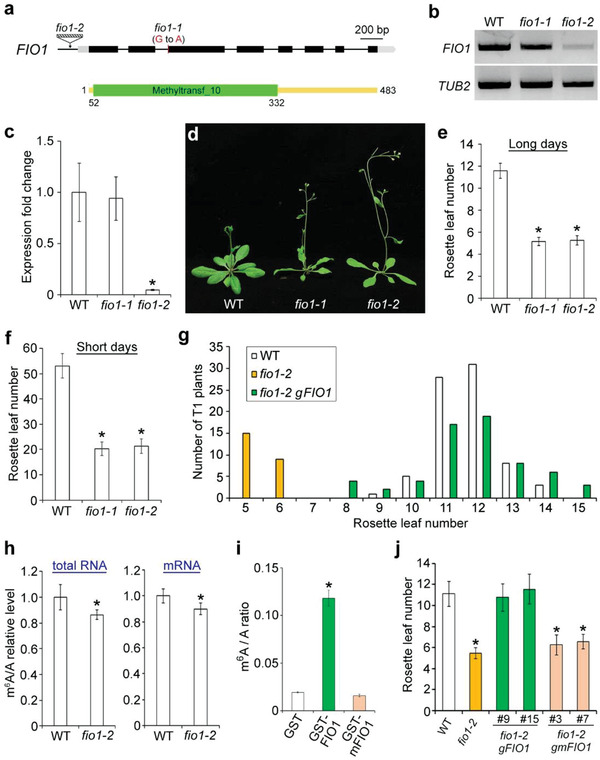

FIO1 contains a methyltransferase domain (Figure 1a) and is the only Arabidopsis ortholog of the human METTL16 (Figure S1, Supporting Information). Within the methyltransferase domain, FIO1 contains the key catalytic motif NPPF (residues 236–239), which is highly conserved among FIO1 homologs in various organisms (Figure S1, Supporting Information). FIO1 was widely expressed in various Arabidopsis tissues (Figure S2, Supporting Information). To study whether FIO1 is involved in m6A methylation in Arabidopsis, we isolated two fio1 mutants, fio1‐1 containing a G to A conversion at the splice acceptor site of the 2nd intron[ 17 ] and fio1‐2 carrying a T‐DNA insertion in the 5′ upstream region (Figure 1a; Figure S3a, Supporting Information). The mutation in fio1‐1 resulted in a 5 amino acid deletion of FIO1 protein sequence (Figure S3b, Supporting Information), but did not affect the FIO1 mRNA expression, whereas in fio1‐2 mutants, FIO1 expression was greatly reduced (Figure 1b,c). Both fio1‐1 and fio1‐2 exhibited early flowering phenotypes under long days (Figure 1d,e) and short days (Figure 1f). Since fio1‐1 and fio1‐2 showed a similar flower time defect, we used fio1‐2 for further studies. A genomic fragment of FIO1 (gFIO1) fully rescued the early flowering phenotype of fio1‐2 (Figure 1g; Figure S4, Supporting Information), demonstrating that FIO1 is responsible for the early‐flowering phenotype observed in fio1‐2.

Figure 1.

FIO1 affects flowering and mRNA m6A levels in Arabidopsis. a) Schematic diagrams show the mutation site in fio1‐1 and the T‐DNA insertion site in fio1‐2 (upper panel) and the methyltransferase domain (green box) in the FIO1 protein (lower panel). Exons in coding sequence and untranslated regions (UTRs) are shown in black and gray boxes, respectively, while introns and other genomic sequences are shown in black lines. fio1‐1 contains a G to A conversion in the last nucleotide in the second intron. b) Semiquantitative RT‐PCR shows the expression of FIO1 in fio1 mutants. TUB2 expression was used an internal control. c) Quantitative real‐time PCR analysis of FIO1 expression in 6‐day‐old seedlings of various genetic background. The expression level of FIO1 in wild‐type seedlings was set as 1.0. Error bars, mean ± SD; n = 3 biological replicates. Asterisk indicates a significant difference between fio1‐2 and wild‐type seedlings (two‐tailed paired Student's t‐test, P < 0.001). d) Loss of FIO1 greatly accelerates flowering under long days. Flowering time of fio1‐1 and fio1‐2 grown under e) long days and f) short days. Error bars, mean ± SD; n = 20. Asterisks indicate significant differences between fio1 mutants and wild‐type plants (two‐tailed paired Student's t‐test, P < 0.001). g) Flowering time distribution of T1 transgenic plants of fio1‐2 gFIO1. The flowering time of each individual T1 transgenic lines of fio1‐2 gFIO1 was scored. h) Measurement of m6A level relative to that of adenosine (m6A/A) by LC‐MS/MS in total RNA (left panel) and mRNA (right panel) isolated from 6‐day‐old wild‐type and fio1‐2 seedlings. The m6A/A ratios in wild‐type seedlings were set as 1.0. Error bars, mean ± SD; n = 3 biological replicates × 3 technical replicates. Asterisks indicate significant differences between fio1‐2 and wild‐type seedlings (two‐tailed paired Student's t‐test, P < 0.01). i) Measurement of m6A level relative to that of adenosine (m6A/A) by LC‐MS/MS in RNA purified from the m6A methylation assay. RNA oligo (GCCAGAGCCAGAGCCAGAGCCAGA) containing four repeats of the consensus m6A motif recognized by FIO1 was incubated with GST, GST‐FIO1, and GST‐mFIO1, after which RNA was purified for measurement of m6A levels by LC‐MS/MS analysis. Error bars, mean ± SD; n = 3 biological replicates. Asterisk indicates a significant difference between GST‐FIO1 and GST or GST‐mFIO1 (two‐tailed paired Student's t‐test, P < 0.01). j) Flowering time of representative fio1‐2 gFIO1 lines (9 and 15) and fio1‐2 gmFIO1 lines (3 and 7) grown under long days. Error bars, means ± SD; n = 20. Asterisks indicate significant differences between the specified genotypes and wild‐type plants (two‐tailed paired Student's t‐test, P < 0.01).

We then examined m6A levels in total RNAs isolated from 6‐day‐old wild‐type and fio1‐2 seedlings by dot blot analysis using anti‐m6A antibody and found a slight reduction of m6A levels in fio1‐2 (Figure S5, Supporting Information). Further quantitative measurement of m6A levels by liquid chromatography‐tandem mass spectrometry (LC‐MS/MS) revealed that m6A levels of total RNA and mRNA in fio1‐2 were decreased by ≈14% and ≈10%, respectively, as compared with those in wild‐type seedlings (Figure 1h). These results suggest that FIO1 is involved in m6A methylation in Arabidopsis. Expression levels of known m6A writer genes, such as MTA, MTB, FIP37, HAKAI, and VIR,[ 12 , 13 , 14 ] as well as the m6A eraser gene ALKBH10B [ 21 ] remained unchanged in fio1‐2 (Figure S6a, Supporting Information), suggesting that FIO1 may be directly involved in depositing m6A.

2.2. Nanopore Direct RNA Sequencing Identified Hypomethylated Sites in CDSs in fio1 Mutants

To reveal how FIO1 contributes to the global m6A mRNA modification, we performed nanopore direct RNA sequencing on poly(A)‐tailed mRNAs from three biological replicates of 6‐day‐old wild‐type and fio1‐2 seedlings. We obtained around three and two million of high‐quality reads (Q‐score > 7) for wild‐type and fio1‐2 seedlings, respectively. Most of the reads are of high‐quality with the Q‐score of around 11 and an average read length of 912–945 nt for each library (Figure S7a,b and Table S1, Supporting Information). This is in line with a previous study showing an average read length of 900–1000 nt of Arabidopsis mRNA.[ 22 ] In addition, we also observed long reads over 11600 nt (Figure S7c, Supporting Information). These observations indicate high integrity of our nanopore reads that can be used for subsequent analyses.

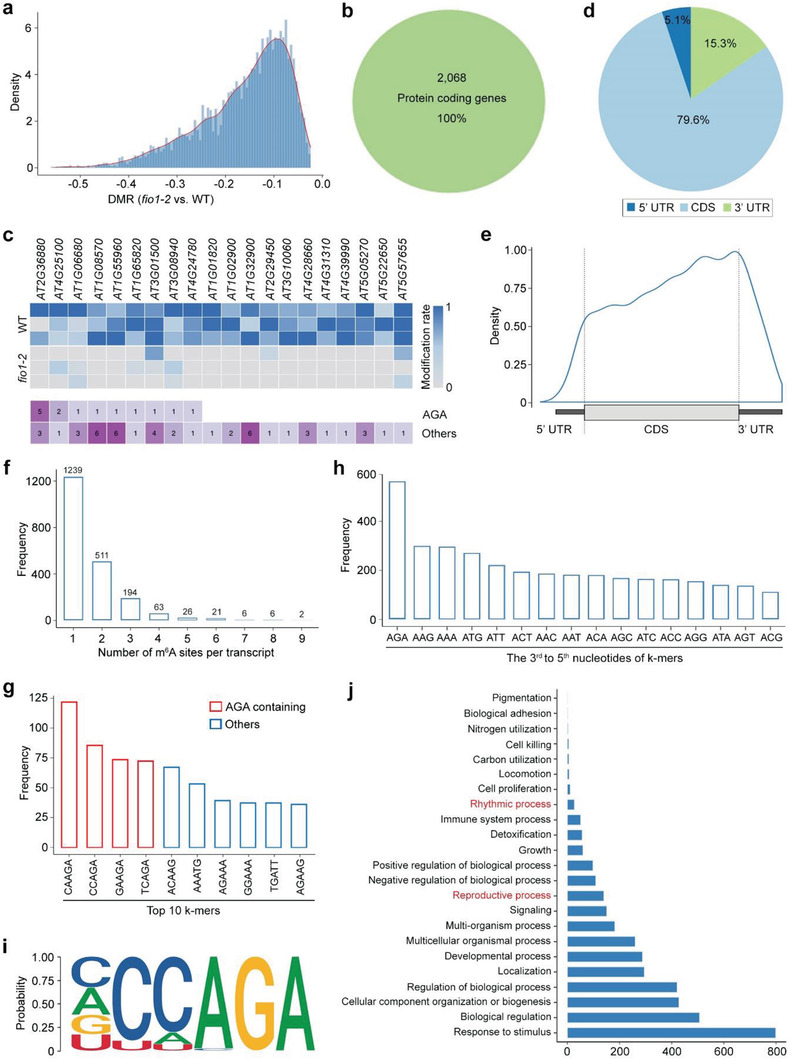

We first mapped the nanopore reads to the transcriptome by Minimap2,[ 23 ] and 96.6–98.4% of the reads were successfully mapped to TAIR10. After the signal segmentation with the Nanopolish software,[ 24 ] we applied the xPore method[ 8 ] to identify differential m6A RNA modifications between wild‐type and fio1‐2. xPore is a computational method that identifies positions of m6A modifications at the single‐base resolution and determines the differential modification rates across different conditions with high accuracy, and has been successfully used for profiling differential m6A modifications in human cell lines and cancer tissues.[ 8 ] By calculating differential modification rates (DMRs) that represent differences between the modification rates in wild‐type and fio1‐2 using A‐centered k‐mers (NNANN) with xPore, we identified a total of 3459 high‐confidence hypomethylated m6A sites that were consistently detected in all three biological replicates in 2068 protein‐coding genes in fio1‐2 (P < 0.01; Figure 2a,b; Table S2, Supporting Information). Most DMRs of hypomethylated sites were less than 50% (Figure 2a), which is in accordance with the mild decrease of total m6A levels observed in fio1‐2 (Figure 1h). We ranked hypomethylated sites by the lowest P value and found that DMRs were consistent in each biological replicate (Figure 2c). After comparing the distribution of these hypomethylated sites along transcripts relative to landmarks in their architecture, we revealed that the majority (79.6%) of hypomethylated sites were enriched in the CDSs and peaked before the stop codon (Figure 2d,e). This is in contrast to the known m6A writers including FIP37 and VIR, which affect m6A modifications mainly near the stop codon and 3′ UTR.[ 9 , 13 ] Thus, FIO1‐dependent m6A sites constitute a distinct subset of m6A modifications in the CDSs. Interestingly, the hypomethylated sites revealed in this study were partially overlapped with the m6A sites identified by the other two antibody‐based sequencing approaches, m6A‐seq[ 21 ] and miCLIP,[ 9 ] using 14‐day‐old seedlings (Figure S8, Supporting Information). Whether this indicates different detection thresholds of various sequencing approaches or a dynamic feature of m6A modifications at different developmental stages needs to be further investigated.

Figure 2.

Distribution of hypomethylated sites in fio1‐2. a) Distribution of DMR for hypomethylated sites in fio1‐2. DMR represents the difference between the modification rates detected between wild‐type and fio1‐2 plants. b) The hypomethylated sites are in 2068 protein‐coding transcripts. c) Heatmap showing the modification rates of top 20 significantly hypomethylated sites in fio1‐2 ranked by P‐value (upper panel) and number of modification sites with AGA or others (lower panel). d) The pie chart displaying the percentages of hypomethylated sites in fio1‐2 in different segments of transcripts divided into 5′ UTR, CDS, and 3′ UTR. e) Distribution of hypomethylated sites in fio1‐2 along the transcript divided into 5′ UTR, CDS, and 3′ UTR. f) Frequency of numbers of m6A sites per transcript of hypomethylated genes in fio1‐2. g) Frequency of the top 10 5‐bp k‐mers at the positions with significantly differential modification rates between wild‐type and fio1‐2 plants. h) Frequency of the last 3 nucleotides of k‐mers at the positions with significantly differential modification rates between wild‐type and fio1‐2 plants. i) Sequence logo representing the consensus motif (YHAGA) found in the hypomethylated sites in fio1‐2. “Y” represents C/U (C > U) and “H” represents C/A/U (C > A/U). j) Gene ontology (GO) enrichment analysis of hypomethylated genes in fio1‐2.

Most of the hypomethylated genes contain only one hypomethylated m6A site (Figure 2f). Some of the top ranked sites containing genes by lowest P value appeared to contain multiple m6A sites involving different k‐mers (Figure 2c). The top four k‐mers in the positions with significantly reduced DMRs between wild‐type and fio1‐2 plants were CAm 6 AGA, CCm 6 AGA, GAm 6 AGA, and TCm 6 AGA, which all contained the sequence of m 6 AGA at the last three nucleotides (Figure 2g). Consistently, m 6 AGA was observed as the most frequently occurred three‐nucleotide sequence in the 3rd to 5th positions of k‐mers (Figure 2h). Furthermore, we identified the YHm 6 AGA (Y = C/U; H = C/A/U) sequence as the most enriched motif among the hypomethylated sites using the HOMER program[ 25 ] (P = 1e‐20; Figure 2i), implying that FIO1 preferentially targets to this motif for m6A methylation. Interestingly, the conserved sequence recognized by METTL16, UACm 6 AGAGAA,[ 20 ] also contains an m 6 AGA sequence in the center. Further gene ontology (GO) analysis showed that the hypomethylated genes could regulate multiple biological processes (Figure 2j). Notably, the genes involved in plant reproductive process and rhythmic process were enriched, which could be associated with the early‐flowering (Figure 1) and lengthening of the free‐running circadian period phenotypes of fio1 mutants.[ 17 ] Taken together, these data demonstrate that FIO1 is responsible for m6A methylation on protein‐coding transcripts preferentially in the coding sequences in Arabidopsis.

To further examine whether FIO1 possesses the m6A methyltransferase activity, we performed in vitro methylation assay through incubating an RNA oligo containing the identified YHAGA motif (Figure 2i) with GST or the recombinant GST‐FIO1 protein, followed by examination of m6A levels by LC‐MS/MS and dot blot assays. GST‐FIO1, but not GST, methylates the RNA oligo (Figure 1i; Figure S9, Supporting Information), suggesting that FIO1 possesses the m6A methyltransferase activity. We then generated a catalytically inactive version of FIO1 by mutating the key catalytic residues NPPF to NAAF (mFIO1237A 238A; hereafter called mFIO1). Both LC‐MS/MS and dot blot assays revealed that mFIO1 lost the m6A methyltransferase activity (Figure 1i; Figure S9, Supporting Information). Moreover, gmFIO1, in which mFIO1 was driven by the same FIO1 promoter used in gFIO1 for the gene complementation assay (Figure 1g), failed to rescue the early‐flowering phenotype of fio1‐2 (Figure 1j), indicating that the m6A methyltransferase activity of FIO1 is essential for its function in flowering time regulation.

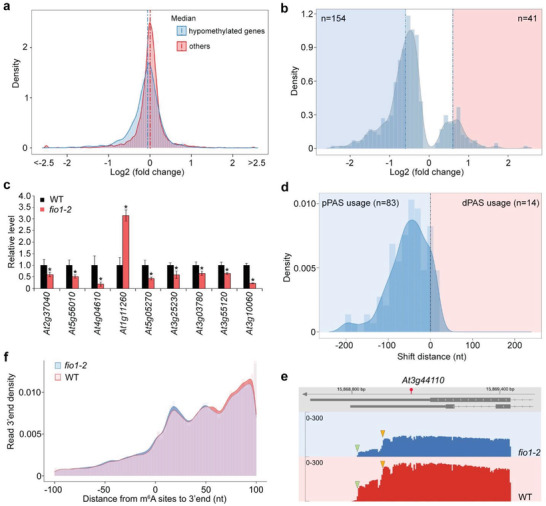

2.3. FIO1‐Mediated m6A Methylation Is Associated with Transcript Abundance and APA

To investigate whether there is a potential correlation between m6A modification and gene expression levels mediated by FIO1, we identified differentially expressed genes (DEGs) between wild‐type and fio1‐2 using the nanopore reads containing both RNA modifications and transcript processing information. There were 367 downregulated and 208 upregulated genes, respectively, in fio1‐2 mutants (fold change >1.5; padj < 0.05) (Table S3, Supporting Information). Genes with hypomethylated sites tended to be downregulated in fio1‐2 (Figure 3a), and comparison of differentially expressed genes with the hypomethylated gene list revealed that the transcript abundance for 154 or 41 genes was decreased or increased in fio1‐2, respectively (Figure 3b). We confirmed the changes in transcript levels of several randomly selected genes (Figure 3c). These observations suggest that FIO1‐mediated m6A modification modulates transcript abundance in Arabidopsis. We further examined whether FIO1 affects pre‐RNA processing events. FIO1 had only a mild effect on RNA splicing and poly(A) tail length (Figures S10 and S11 and Table S4, Supporting Information). In addition, there were 15.3% of the hypomethylated sites located in the 3′ UTR (Figure 2d). Since m6A methylation in 3′ UTR is associated with 3′ end formation,[ 9 ] we further examined whether FIO1 also affects the selection of alternative polyadenylation (APA) sites. Among 83 out of 97 transcripts shifting to the usage of proximal poly(A) sites (Figure 3d,e), 60.8% of these transcripts contained hypomethylated sites (Table S5, Supporting Information). The changes were mainly located downstream to the m6A sites (Figure 3f). Taken together, these data suggest that FIO1‐mediated m6A methylation is associated with transcript abundance and APA.

Figure 3.

FIO1 regulates transcript abundance and alternative polyadenylation. a) Distribution of changes in gene expression between fio1‐2 and wild‐type plants for hypomethylated genes and other genes (P < 10 × 10−16, two sided Mann–Whitney test). b) Distribution of differentially expressed genes with hypomethylated sites in fio1‐2 compared with wild‐type seedlings (P < 0.05; log2 (fold change) > 0.6). c) Expression of several randomly chosen differentially expressed genes in fio1‐2 determined by real‐time PCR. Six‐day‐old wild‐type and fio1‐2 seedlings grown under long days were harvested for expression analysis. The expression levels of each gene in wild‐type seedlings were set as 1.0. Error bars, mean ± SD; n = 3 biological replicates. Asterisks indicate significant differences between fio1‐2 and wild‐type seedlings (two‐tailed paired Student's t‐test, P < 0.05). d) A shift to the usage of proximal 3′ end polyadenylation sites found in fio1‐2 compared with wild‐type. e) At3g44110, which is methylated in the 3′ UTR, shows a shift to the usage of the proximal polyadenylation site in fio1‐2. The position of the hypomethylated site is indicated by a red circle. Green and yellow triangles indicate the distal and proximal sites, respectively. f) Histogram showing the distance from the hypomethylated sites to the 3′ end of nanopore reads.

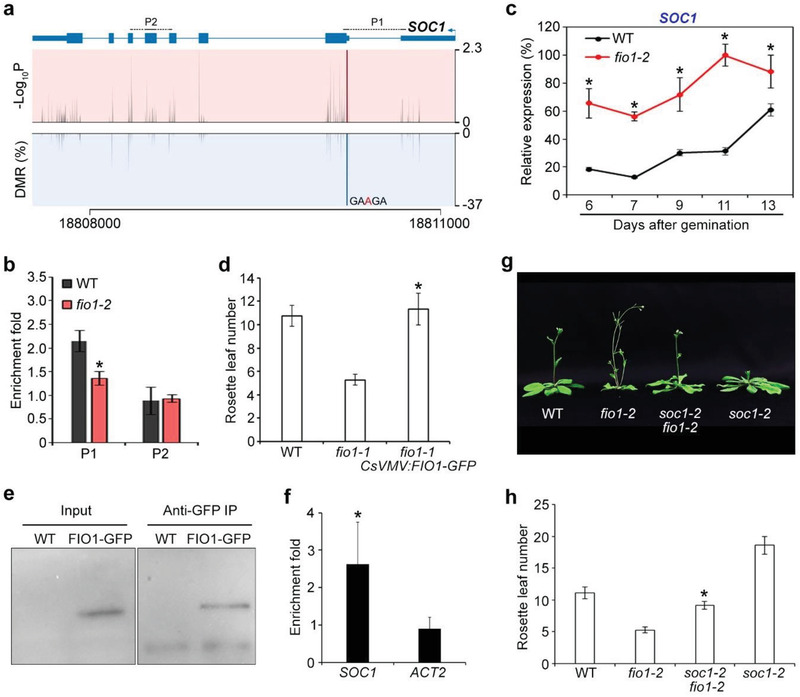

2.4. FIO1‐Mediated m6A Modification Suppresses SOC1 Expression to Control Flowering

In line with the early‐flowering phenotype observed in fio1‐2 mutants (Figure 1d,e), the hypomethylated genes include a key flowering integrator SOC1 [ 26 , 27 ] (Figure S12 and Table S2, Supporting Information), which is among the differentially expressed genes in fio1‐2 (Table S3, Supporting Information). SOC1 transcript contains a hypomethylated site (GAm 6 AGA) in the 5′ UTR immediately upstream of the start codon (Figure 4a). The reduced m6A levels on SOC1 transcripts were further verified by m6A‐IP‐qPCR in fio1‐2 mutants (Figure 4b). Consistent with the nanopore sequencing results, quantitative real‐time PCR revealed that SOC1 expression was significantly upregulated in developing fio1‐2 seedlings compared to wild‐type plants (Figure 4c). The reduction of m6A levels on SOC1 transcripts and increased SOC1 expression in fio1‐2 were restored in fio1‐2 gFIO1, but not in fio1‐2 gmFIO1 (Figure S13, Supporting Information). Moreover, FIO1‐GFP directly bound to SOC1 transcripts in vivo as revealed by RNA immunoprecipitation followed by quantitative real‐time PCR assays with a functional fio1‐1 CsVMV:FIO1‐GFP line[ 17 ] (Figure 4d–f), suggesting that FIO1 directly modulates m6A methylation on SOC1 transcripts and its expression levels.

Figure 4.

FIO1‐mediated m6A methylation modulates SOC1 expression in flowering time control. a) Diagram showing the DMR, the corresponding P value, and the transcript sequence with an identified m6A site in SOC1 transcripts. The gene structure is shown above. Thick and thin boxes represent exons and UTRs, respectively, and lines represent introns. The sequences amplified by the primers are labeled above the gene structure. b) Verification of the nanopore direct RNA sequencing result for SOC1. m6A‐IP‐qPCR was performed with 6‐day‐old wild‐type and fio1‐2 seedlings. Error bars, mean ± SD; n = 3 biological replicates. Asterisk indicates a significant difference in m6A enrichment levels between fio1‐2 and wild‐type seedlings (two‐tailed paired Student's t‐test, P < 0.05). c) Temporal expression pattern of SOC1 in developing wild‐type and fio1‐2 seedlings. Wild‐type and fio1‐2 seedlings grown under long days were harvested for expression analysis. The expression levels were normalized to TUB2 expression and then normalized to the highest expression level set as 100%. Error bars, mean ± SD; n = 3 biological replicates. Asterisks indicate significant differences between fio1‐2 and wild‐type seedlings (two‐tailed paired Student's t‐test, P < 0.05). d) An fio1‐1 CsVMV:FIO1‐GFP transgenic line shows comparable flowering time to a wild‐type plant under long days. Error bars, mean ± SD; n = 15. Asterisk indicates a significant difference in the flowering time between fio1‐1 CsVMV:FIO1‐GFP and fio1‐1 (two‐tailed paired Student's t‐test, P < 0.05). e) FIO1‐GFP can be detected and immunoprecipitated by anti‐GFP antibodies. Six‐day‐old wild‐type and CsVMV:FIO1‐GFP seedlings were harvested for analysis. Western blot was performed with the input and immunoprecipitated (IP) samples using anti‐GFP antibody. f) RNA immunoprecipitation assay reveals the direct binding of FIO1‐GFP to SOC1 transcripts. Six‐day‐old wild‐type and fio1‐1 CsVMV:FIO1‐GFP seedlings grown under long days were harvested for RNA immunoprecipitation assay. Enrichment of ACTIN2 (ACT2) was included as a negative control. Error bars, mean ± SD; n = 3 biological replicates. Asterisk indicates a significant difference in FIO1‐GFP enrichment on SOC1 compared with the ACT2 negative control (two‐tailed paired Student's t‐test, P < 0.05). g) A soc1‐2 fio1‐2 double mutant flowers later than fio1‐2. h) Flowering time of soc1‐2 fio1‐2 under long days. Error bars, mean ± SD; n = 15 plants. Asterisk indicates a significant difference in the flowering time between soc1‐2 fio1‐2 and fio1‐2 (two‐tailed paired Student's t‐test, P < 0.05).

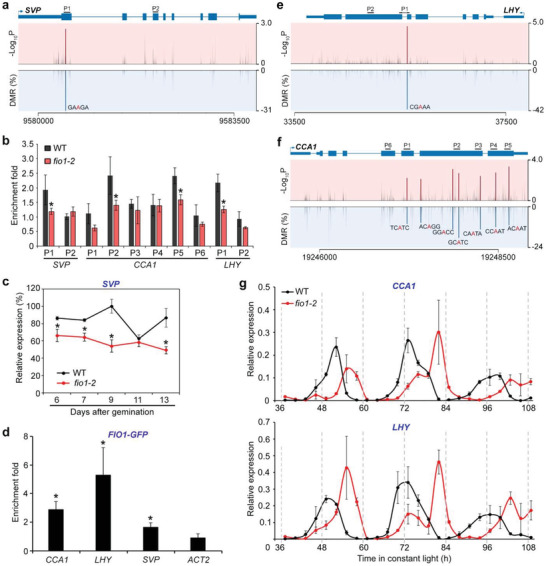

Interestingly, we also identified SHORT VEGETATIVE PHASE (SVP), a direct repressor of SOC1,[ 26 ] was a hypomethylated gene in fio1‐2 (Figure 5a; Figure S12 and Table S2, Supporting Information). The reduced m6A level on SVP transcript was further confirmed by m6A‐IP‐qPCR (Figure 5b). SVP expression was significantly downregulated in developing fio1‐2 seedlings compared to wild‐type plants (Figure 5c), which is in agreement with the early‐flowering phenotype of fio1‐2. FIO1‐GFP was associated with SVP transcripts (Figure 5d), indicating that FIO1 directly methylates SVP to regulate its expression. Indeed, the reduction of m6A levels on SVP transcripts and decreased SVP expression in fio1‐2 were restored in fio1‐2 gFIO1, but not in fio1‐2 gmFIO1 (Figure S13, Supporting Information).

Figure 5.

FIO1‐mediated m6A methylation modulates the expression pattern of genes acting upstream of SOC1. a) Schematic diagrams showing the DMRs, the corresponding P value, and the transcript sequence with an identified m6A site in SVP transcripts. The gene structure is shown above. Thick and thin boxes represent exons and UTRs, respectively, and lines represent introns. The sequences amplified by the primers are labeled above the gene structure. b) Verification of the nanopore direct RNA sequencing results for several genes acting upstream of SOC1. m6A‐IP‐qPCR was performed with 6‐day‐old wild‐type and fio1‐2 seedlings. Error bars, mean ± SD; n = 3 biological replicates. Asterisks indicate significant differences in m6A enrichment levels between fio1‐2 and wild‐type seedlings (two‐tailed paired Student's t‐test, P < 0.05). c) Temporal expression pattern of SVP in developing wild‐type and fio1‐2 seedlings. Wild‐type and fio1‐2 seedlings grown under long days were harvested for expression analysis. The expression levels were normalized to TUB2 expression and then normalized to the highest expression level set as 100%. Error bars, mean ± SD; n = 3 biological replicates. Asterisks indicate significant differences between fio1‐2 and wild‐type seedlings (two‐tailed paired Student's t‐test, P < 0.05). d) RNA immunoprecipitation assay reveals the direct binding of FIO1‐GFP to the transcripts of SVP, CCA1, and LHY. Six‐day‐old wild‐type and fio1‐1 CsVMV:FIO1‐GFP seedlings grown under long days were harvested for RNA immunoprecipitation assay. Enrichment of ACT2 was included as a negative control. Error bars, mean ± SD; n = 3 biological replicates. Asterisks indicate significant differences in FIO1‐GFP enrichment on SVP, CCA1, and LHY compared with ACT2 (two‐tailed paired Student's t‐test, P < 0.05). Schematic diagrams showing the DMRs, corresponding P values, and the transcript sequences with the identified m6A sites in e) CCA1 and f) LHY transcripts. g) Disruption of fio1‐2 lengthens the cycling periods of CCA1 (upper panel) and LHY (lower panel). Wild‐type and fio1‐2 seedlings were first entrained with 12 h light/12 h dark photoperiods for 9 days before being shifted to the constant light conditions at ZT 0. The samples were collected at 3 h interval from ZT 37 for 3 days. Expression levels of CCA1 and LHY were determined by quantitative real‐time PCR and normalized to the expression of TUB2.

Moreover, the central circadian oscillator genes CIRCADIAN CLOCK ASSOCIATED 1 (CCA1) and LATE ELONGATED HYPOCOTYL (LHY)[ 28 ] were also identified as hypomethylated genes in fio1‐2 (Figure S12 and Table S2, Supporting Information). Interestingly, CCA1 contains seven hypomethylated sites in its CDS involving different k‐mers, whereas LHY contains one hypomethylated sites (Figure 5e,f). Among them, several sites were verified with m6A‐IP‐qPCR (Figure 5b), implying that nanopore direct sequencing may identify modification sites below the detection threshold of antibody‐based approaches as similarly shown in mammalian cells.[ 8 ] As CCA1 and LHY are clock genes, we further examined the effect of FIO1 on their expression pattern, and found that disruption of FIO1 lengthened the period length of the expression of CCA1 and LHY (Figure 5g). This is consistent with the previous study showing that FIO1 controls period length in the circadian clock.[ 17 ] FIO1‐GFP was associated with the CCA1 and LHY transcripts (Figure 5d), indicating that FIO1 directly methylates CCA1 and LHY mRNAs. As a major output of the circadian oscillation is its effect on flowering time, we consequently observed the upregulation of two circadian‐regulated genes, CONSTANS (CO)[ 29 ] and its immediate downstream gene FLOWERING LOCUS T (FT),[ 30 , 31 ] in fio1‐2 mutants, although CO and FT were not the methylated targets of FIO1 (Figure S14a–c and Table S2, Supporting Information). As FT positively regulates SOC1 expression,[ 32 ] FIO1 effect on circadian clock genes indirectly contributes to repression of SOC1. Taken together, these observations indicate that FIO1‐mediated m6A methylation suppresses SOC1 expression through both directly downregulating SOC1 transcript abundance and indirectly affecting the mRNA expression of its upstream regulators, including SVP, CO, and FT. Indeed, soc1‐2 greatly suppressed the early‐flowering phenotype of fio1‐2 (Figure 4g,h), further supporting that FIO1 functions through SOC1 to prevent premature flowering.

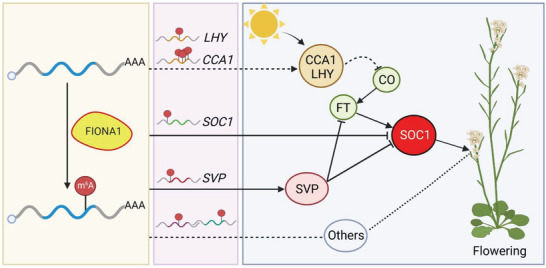

In this study, we have revealed that FIO1 functions as an m6A methyltransferase and regulates flowering time in Arabidopsis (Figure 6 ). Compared to m6A deposition mainly near the stop codon and 3′ UTR by other known m6A writers,[ 9 , 13 ] the hypomethylated sites in fio1 mutants are mainly located in the CDS region, implying that FIO1 acts independently of other known m6A writers. Similarly, METTL16‐dependent m6A peaks mainly found in the introns and intron–exon boundaries in human genes are also distinct from those m6A sites found in 3′ UTRs.[ 20 ] FIO1 does not regulate the expression levels of known m6A writer genes or is not involved in the multicomponent m6A writer complex (Figure S6b, Supporting Information). Moreover, the consensus motif YHm 6 AGA mostly enriched in the FIO1‐methylated targets is different from the motif RRm 6 ACH associated with the other known m6A writers.[ 9 , 13 ] Thus, different m6A methyltransferases exist and function concurrently to establish the m6A landscape in plants.

Figure 6.

A proposed model depicting the function of FIO1 in m6A modification and flowering time control in Arabidopsis. FIO1 is involved in depositing m6A methylation mainly on the CDS of a subset of protein‐coding transcripts. FIO1‐mediated m6A methylation determines the expression of the central flowering integrator SOC1 through both directly downregulating SOC1 transcript abundance and indirectly affecting the mRNA expression of its upstream regulators, including SVP, CO, and FT, to prevent premature flowering. FIO1 directly methylates the transcripts of SOC1, SVP, CCA1, LHY, and possibly other genes in regulating the floral transition. FIO1 modulates the transcript levels of SVP, a direct repressor of SOC1. FIO1 is also required for the normal cycling periods of CCA1 and LHY, which in turn affect the expression of CO and FT, thus influencing SOC1 expression. Direct stimulatory interactions are indicated by arrows, and direct or indirect inhibitory interactions are indicated by T‐bars or dashed lines with T‐bars, respectively. The dashed line with arrow indicates that FIO1 regulates the cycling periods of CCA1 and LHY, while the dashed lines indicate possible effects of other unknown targets of FIO1 on flowering. Created with BioRender.com

Unlike other known methyltransferases in Arabidopsis, FIO1‐mediated m6A modification uniquely regulates the key developmental transition from vegetative to reproductive growth through at least directly and indirectly downregulating the mRNA abundance of a central flowering integrator SOC1 (Figure 6). Interestingly, in addition to the FIO1‐dependent m6A sites in their 5′UTR/CDS junction and CDS, both SOC1 and SVP mRNAs extracted from various developmental stages also bear FIP37‐dependent m6A peaks or VIR‐dependent m6A sites in their 3′ UTRs (Figure S15a, Supporting Information). However, unlike FIO1, the other known m6A writers, including FIP37 and VIR, did not significantly affect the expression of SOC1 and SVP before the floral transition (Figure S15b, Supporting Information). These observations imply that although FIO1 and the other known m6A writers could methylate the same mRNAs, different methylation sites could result in different cellular fates of these mRNAs. Moreover, as the hypomethylated genes in fio1‐2 mutants also include other clock component genes or chromatin regulatory genes (Figure S12 and Table S2, Supporting Information), it would be interesting to further investigate whether FIO1 effect on these genes may also contribute to modulation of flowering time under different environmental and developmental conditions.

METTL16, the ortholog of FIO1 in human, also functions as a U6 snRNA m6A methyltransferase.[ 20 ] In our study, we found that m6A level in U6 snRNAs were indeed reduced in fio1‐2 (Figure S16, Supporting Information), suggesting the conserved function of FIO1 and METTL16 in methylating U6 snRNAs. In addition, we also observed that MAT1/2/3/4,[ 33 , 34 , 35 ] all four Arabidopsis orthologous genes of the human SAM synthetase gene MTA2A, contain hypomethylated sites in fio1 mutants (Figures S17 and S18a, Supporting Information), implying a scenario similar to methylating MTA2A by METTL16 in human. However, the MAT genes in Arabidopsis do not possess the hairpin structure in the 3′ UTR, which is present in human MTA2A and is m6A methylated by METTL16,[ 20 ] indicating that FIO1 and METTL16 may methylate on their targets in different manners. Moreover, the expression levels of these MAT genes were not altered in fio1 mutants (Figure S18b, Supporting Information), raising the possibility that FIO1 may affect MAT transcript processing in other aspects, such as translocation or translation.

3. Conclusion

Overall, our study elucidates the function of FIO1 as a unique m6A methyltransferase independently of other known m6A methyltransferases in establishing appropriate levels of m6A modifications preferentially in the coding sequences of a subset of protein coding transcripts. FIO1‐mediated m6A methylation is associated with transcript abundance and alternative polyadenylation, but has a limited effect on alternative splicing. We further reveal that FIO1‐mediated m6A methylation determines the mRNA abundance of a central flowering integrator SOC1 and its upstream regulators, thus preventing early flowering. Our findings provide novel insights into understanding of m6A landscape, the associated new players and their biological functions in plants, and also shed light into the cognate mechanisms of METTL16‐mediated RNA modification in animals.

4. Experimental Section

Plant Materials and Growth Conditions

Seeds of Arabidopsis (A. thaliana) were placed on soil or Murashige and Skoog (MS) medium and stratified at 4 °C in darkness for 3 days before they were grown under long days (16 h light/8 h dark) or short days (8 h light/16 h dark) at 23 ± 2 °C. The seeds of fio1‐2 (SALK_209355) were ordered from the Arabidopsis Information Resource, and the seeds of fio1‐1 mutants and fio1‐1 CsVMV:FIO1‐GFP transgenic plants were kindly provided by Prof. Hong Gil Nam (Daegu Gyeongbuk Institute of Science and Technology). Agrobacterium tumefaciens‐mediated transformation of Arabidopsis mutant plants was performed using the floral dipping method.[ 36 ]

Plasmid Construction

To construct gFIO1, the 4.7 kb FIO1 genomic sequence including 2.0 kb upstream sequence, 2.7 kb full‐length coding region plus intron, and the 3′ UTR was amplified and ligated into a pENTR vector. The gFIO1 construct also served as a template for generating gmFIO1, in which the key catalytic residues “NPPF” were mutated to “NAAF.” Both gFIO1 and gmFIO1 vectors were introduced to the destination vector through the Gateway LR recombination assay (Invitrogen).

Dot Blot Analysis

Dot blot analysis was performed as previously described.[ 13 ] Briefly, denatured mRNA was spotted onto a Hybond‐N+ membrane (Amersham) that is optimized for nucleic acid transfer. The membrane was UV crosslinked in a Stratalinker 2400 UV Crosslinked (Stratagene), before it was washed by 1× PBST buffer for 5 min at room temperature. The membrane was then blocked with 5% of nonfat milk in PBST, and incubated with anti‐m6A antibody (1:250, Synaptic Systems) overnight at 4 °C. After incubating with horseradish‐peroxidase‐conjugated anti‐rabbit IgG secondary antibody (Santa Cruz), the membrane was visualized with an ECL Western Blotting Detecting Kit (Thermo) in a ChemiDoc Touch Imaging System (Bio‐rad).

Measurement of m6A/A Ratio by LC‐MS/MS Analysis

Total RNA was extracted with the RNeasy Plus Mini Kit and mRNA was purified from the total RNA using Dynabeads Oligo(dT)25 (Invitrogen). mRNA was digested into single ribonucleosides as previously described,[ 37 ] followed by clean‐up with chloroform. Samples were subjected to LC‐MS/MS analysis on a SCIEX QTRAP 6500 spectrometer. Multiple reaction monitoring mode was used to detect A and m6A with mass transitions at 268.0 to 136.0 and 282.0 to 150.1, respectively.

Nanopore Direct RNA Sequencing

Six‐day‐old seedlings of wild‐type and fio1‐2 were harvested, and total RNA was extracted with the TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen). mRNA was then purified from the total RNA using Dynabeads Oligo(dT)25 (Invitrogen). The quantity and quality of mRNA were determined with an Agilent Bioanalyzer system. Each library was prepared with around 750 ng of mRNA using the Nanopore direct RNA sequencing kit (SQK‐RNA002, Oxford Nanopore Technologies). The prepared libraries were loaded onto FLO‐MIN106 flow cells and sequenced with the GridION device. The run duration for each library was ≈40‐72 h. The raw fast5 data were base called with Guppy 4.2.3 with the high accuracy mode to generate FASTQ files.

m6A Modification Site Analysis

The FASTQ reads were mapped to the reference transcriptome of TAIR10 by Minimap2 2.20.[ 23 ] Alignment was subsequently converted to BAM file by Samtools[ 38 ] and Nanopolish Eventalign v0.13[ 24 ] was used for signal segmentation. Both aligned reads and events with the reference annotation (Ensemble plant release 50) were processed with Xpore[ 8 ] to detect differential m6A modification site.

Differential Expression Analysis with Nanopore Reads

Reads count for wild‐type and fio1‐2 was performed with Subread v2.0.3[ 39 ] and featureCounts v2.0.2[ 40 ] in the long‐read mode. Differentially expressed genes were identified with DESeq2 v1.32.[ 41 ]

Poly(A) Length Estimation

Nanopolish v0.13[ 24 ] was performed to analyze the poly(A) signal from the fast5 file. Differences between fio1‐2 and wild‐type were identified using a Mann–Whitney test.

Alternative Splicing Analysis

Full‐length alternative isoform analysis of RNA (FLAIR) v1.5[ 42 ] was performed to detect the differential isoform usage and differential alternative splicing events between wild‐type and fio1‐2 with the nanopore reads following the standard workflow.

Identification of Alternative 3′ End Positions

3′ end usage of wild‐type and fio1‐2 plants was recorded and reads that overlapped with each gene locus less than 20% were filtered. To identify the differential usage of each position between wild‐type and fio1‐2, the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test was performed followed by multiple testing correction with the Benjamini–Hochberg method. The differential 3′ end usage results were filtered for an FDR of <0.05. Subsequently, the 3′ end usage to total number of reads of each gene locus was normalized, and the difference between normalized numbers of fio1‐2 and wild‐type of each site was used to get the minimum and maximum numbers, which represent the most reduced and increased 3′ end usage sites, respectively. The difference between most reduced and most increased 3′ end usage sites was used to estimate the direction and distance of each change.

In Vitro Methylation Assay

The in vitro methylation assay was performed as previously described.[ 43 , 44 ] An RNA probe (GCCAGAGCCAGAGCCAGAGCCAGA) containing four repeats of the consensus m6A motif recognized by FIO1 was synthesized. The full‐length coding sequence of FIO1 was cloned into pGEX‐6p‐2 vector (GE Healthcare). This construct further served as a template for generating mFIO1, in which the key catalytic residues “NPPF” were mutated to “NAAF.” GST, GST‐FIO1, and GST‐mFIO1 proteins were expressed in Escherichia coli Rosetta (DE3) cells by induction with isopropyl β‐D‐1‐thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) at 16 °C overnight, and purified with Glutathione Sepharose (Amersham Bioscience).

Expression Analysis

Total RNA was extracted with the RNeasy Plus Mini Kit (QIAGEN) and reversed transcribed with the M‐MLV Reverse Transcriptase (Promega) following the manufacturers’ protocols. Quantitative real‐time PCR was performed on three biological replicates using 7900HT Fast Real‐Time PCR systems (Applied Biosystems) with PowerUp SYBR Green Master Mix (Applied Biosystems). TUB2 expression was used as an internal control. The difference between the cycle threshold (Ct) of target genes and the Ct of control primers (∆Ct = Cttarget gene − Ctcontrol) was used to calculate the normalized expression of target genes. The primers used for gene expression analysis are listed in Table S6 in the Supporting Information.

m6A‐IP‐qPCR

m6A‐IP‐qPCR was performed as previously described.[ 6 , 13 ] Total RNA was extracted from wild‐type and fio1‐2 seedlings with the RNeasy Plus Mini Kit (QIAGEN) and fragmented into ≈200‐nucleotide‐long fragments. Fragmented RNA was incubated with anti‐m6A antibody (202‐003; Synaptic Systems) in IP buffer (10 × 10−3 m Tris‐HCl pH 7.4, 150 × 10−3 m NaCl, 0.1% Igepal CA‐630) supplemented with RNasin Plus RNase inhibitor (Progema) for 2 h at 4 °C with gentle rotation. This mixture was subsequently incubated with Protein A/G Plus Agarose (Santa Cruz) that was prebound with BSA for an additional 2 h at 4 °C with gentle rotation. After extensive wash with IP buffer, the bound RNA was eluted from the beads with IP buffer plus 6.7 × 10−3 m N 6‐methyladenosine 5′‐monophosphate sodium salt (Sigma) and precipitated by ethanol. The input and immunoprecipitated RNA were then reverse transcribed using random hexamers (Invitrogen) with M‐MLV Reverse Transcriptase (Promega). Relative enrichment of each fragment was determined by quantitative real‐time PCR and calculated as previously described.[ 13 ] A TUB2 fragment was used as internal control. The primers used for m6A‐IP‐qPCR analysis are listed in Table S6 in the Supporting information.

RNA Immunoprecipitation

RNA immunoprecipitation was performed as previously published[ 45 ] with minor modifications. Two grams of 6‐day‐old seedlings of FIO1‐GFP were collected and fixed with 1% formaldehyde under vacuum for 20 min. The fixed tissues were homogenized and lysed with cell lysis buffer (50 × 10−3 m Tris‐HCl, pH 7.5, 150 × 10−3 m NaCl, 4 × 10−3 m MgCl2, 0.25% Igepal CA‐630, 1% SDS, 0.25% sodium deoxycholate, and 5 × 10−3 m DTT) supplemented with Complete EDTA‐free Protease Inhibitor Cocktail (Roche) and RNasin Plus RNase inhibitor (Promega). The protein extract was subjected to immunoprecipitation with anti‐GFP antibody (Invitrogen) bound to Protein A/G Plus Agarose (Santa Cruz). After incubating at 4 °C for 4 h, the beads were washed extensively with the washing buffer (50 × 10−3 m Tris‐HCl, pH 7.5, 500 × 10−3 m NaCl, 4 × 10−3 m MgCl2, 0.5% Igepal CA‐630, 1% SDS, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, 2 m urea, and 2 × 10−3 m DTT) supplemented with RNasin Plus RNase inhibitor for four times. The beads were subsequently treated with Turbo DNase (Invitrogen) at 37 °C for 10 min. RNA was extracted from the input and beads with RNeasy Plus Mini Kit (QIAGEN) and reversed transcribed with random hexamers (Invitrogen) using the M‐MLV Reverse Transcriptase (Promega) following the manufacturers’ protocols. Relative enrichment of each gene was determined by quantitative real‐time PCR and calculated as previously described.[ 13 ] The primers used for RNA immunoprecipitation analysis are listed in Table S6 in the Supporting information.

Yeast Two‐Hybrid

To construct AD‐FIO1, the coding sequence of FIO1 was amplified and ligated into pGADT7 (Clontech). The coding sequences of MTA, MTB, HAKAI, and FIP37 were amplified and ligated into pGBKT7 (Clontech). The yeast two‐hybrid assay was performed with the yeast strain AH109 using the Yeastmaker Yeast Transformation System according to the manufacturer's instructions (Clontech).

Data Availability

The nanopore direct RNA sequencing data described in this study have been deposited in NCBI Sequence Read Archive (SRA) database with the accession number: PRJNA749003. All the other data are available from the corresponding authors upon request.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical details of the experiments are available in figure legends, including the statistical test used and exact value of n. The significance of the data between experimental groups was determined by two sided Mann–Whitney test, Kolmogorov–Smirnov test, Benjamini–Hochberg method, or two‐tailed paired Student's t‐test. A P value less than 0.05 represented a statistically significant difference, unless otherwise stated. P values of differential modification rates were determined by Xpore from z‐test of the differential modification rates.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Author Contributions

T.X., H.Y., and L.S. conceived and designed this study. T.X., X.W., C.E.W., F.S., Y.Z., Z.L., and L.S. performed the experiments. T.X., S.Z., H.Y., and L.S. analyzed data. T.X., H.Y., and L.S. wrote the paper. All authors read and approved the manuscript.

Supporting information

Supporting Information

Supplemental Table S1‐S6

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Prof. Hong Gil Nam (Daegu Gyeongbuk Institute of Science and Technology (DGIST)) for providing the Arabidopsis fio1‐1 and fio1‐1 CsVMV:FIO1‐GFP seeds. The authors thank Genome Institute of Singapore, A*STAR for the nanopore direct RNA sequencing service and the Protein and Proteomics Centre (PPC) in the Department of Biological Sciences, National University of Singapore, for the LC‐MS/MS service. This work was supported by the National Research Foundation Competitive Research Programme (NRF‐CRP22‐2019‐0001), the Agency for Science, Technology and Research (A*STAR) under its Industry Alignment Fund – Pre Positioning (IAF‐PP) (A19D9a0096), and the intramural research support from Temasek Life Sciences Laboratory and National University of Singapore. Figure for TOC is created with BioRender.com

Xu T., Wu X., Wong C. E., Fan S., Zhang Y., Zhang S., Liang Z., Yu H., Shen L., FIONA1‐Mediated m6A Modification Regulates the Floral Transition in Arabidopsis . Adv. Sci. 2022, 9, 2103628. 10.1002/advs.202103628

Contributor Information

Hao Yu, Email: dbsyuhao@nus.edu.sg.

Lisha Shen, Email: lisha@tll.org.sg.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are openly available in NCBI Sequence Read Archive (SRA) database at https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra/PRJNA749003, reference number 749003.

References

- 1. Shao Y., Wong C. E., Shen L., Yu H., Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2021, 63, 102047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kadumuri R. V., Janga S. C., Trends Mol. Med. 2018, 24, 886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Zhao B. S., Roundtree I. A., He C., Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2017, 18, 31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Shen L., Liang Z., Wong C. E., Yu H., Trends Plant Sci. 2019, 24, 328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Linder B., Grozhik A. V., Olarerin‐George A. O., Meydan C., Mason C. E., Jaffrey S. R., Nat. Methods 2015, 12, 767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Dominissini D., Moshitch‐Moshkovitz S., Salmon‐Divon M., Amariglio N., Rechavi G., Nat. Protoc. 2013, 8, 176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Garalde D. R., Snell E. A., Jachimowicz D., Sipos B., Lloyd J. H., Bruce M., Pantic N., Admassu T., James P., Warland A., Jordan M., Ciccone J., Serra S., Keenan J., Martin S., McNeill L., Wallace E. J., Jayasinghe L., Wright C., Blasco J., Young S., Brocklebank D., Juul S., Clarke J., Heron A. J., Turner D. J., Nat. Methods 2018, 15, 201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Pratanwanich P. N., Yao F., Chen Y., Koh C. W. Q., Wan Y. K., Hendra C., Poon P., Goh Y. T., Yap P. M. L., Chooi J. Y., Chng W. J., Ng S. B., Thiery A., Goh W. S. S., Göke J., Nat. Biotechnol. 2021, 39, 1394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Parker M. T., Knop K., Sherwood A. V., Schurch N. J., Mackinnon K., Gould P. D., Hall A. J., Barton G. J., Simpson G. G., eLife 2020, 9, e49658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Lorenz D. A., Sathe S., Einstein J. M., Yeo G. W., RNA 2020, 26, 19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Liu H., Begik O., Lucas M. C., Ramirez J. M., Mason C. E., Wiener D., Schwartz S., Mattick J. S., Smith M. A., Novoa E. M., Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 4079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Růžička K., Zhang M., Campilho A., Bodi Z., Kashif M., Saleh M., Eeckhout D., El‐Showk S., Li H. Y., Zhong S. L., De Jaeger G., Mongan N. P., Hejátko J., Helariutta Y., Fray R. G., New Phytol. 2017, 215, 157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Shen L. S., Liang Z., Gu X. F., Chen Y., Teo Z. W., Hou X. L., Cai W. M., Dedon P. C., Liu L., Yu H., Dev. Cell 2016, 38, 186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Zhong S. L., Li H. Y., Bodi Z., Button J., Vespa L., Herzog M., Fray R. G., Plant Cell 2008, 20, 1278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Shen L., Yu H., Mol. Plant 2021, 14, 1418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Bodi Z., Zhong S. L., Mehra S., Song J., Graham N., Li H. Y., May S., Fray R. G., Front. Plant Sci. 2012, 3, 48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kim J., Kim Y., Yeom M., Kim J. H., Nam H. G., Plant Cell 2008, 20, 307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Mendel M., Chen K. M., Homolka D., Gos P., Pandey R. R., McCarthy A. A., Pillai R. S., Mol. Cell 2018, 71, 986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Shima H., Matsumoto M., Ishigami Y., Ebina M., Muto A., Sato Y., Kumagai S., Ochiai K., Suzuki T., Igarashi K., Cell Rep. 2017, 21, 3354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Pendleton K. E., Chen B., Liu K., Hunter O. V., Xie Y., Tu B. P., Conrad N. K., Cell 2017, 169, 824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Duan H. C., Wei L. H., Zhang C., Wang Y., Chen L., Lu Z. K., Chen P. R., He C., Jia G. F., Plant Cell 2017, 29, 2995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Zhang S., Li R., Zhang L., Chen S., Xie M., Yang L., Xia Y., Foyer C. H., Zhao Z., Lam H. M., Nucleic Acids Res. 2020, 48, 7700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Li H., Bioinformatics 2018, 34, 3094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Loman N. J., Quick J., Simpson J. T., Nat. Methods 2015, 12, 733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Heinz S., Benner C., Spann N., Bertolino E., Lin Y. C., Laslo P., Cheng J. X., Murre C., Singh H., Glass C. K., Mol. Cell 2010, 38, 576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Li D., Liu C., Shen L., Wu Y., Chen H., Robertson M., Helliwell C. A., Ito T., Meyerowitz E., Yu H., Dev. Cell 2008, 15, 110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Lee H., Suh S. S., Park E., Cho E., Ahn J. H., Kim S. G., Lee J. S., Kwon Y. M., Lee I., Genes Dev. 2000, 14, 2366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Alabadi D., Oyama T., Yanovsky M. J., Harmon F. G., Mas P., Kay S. A., Science 2001, 293, 880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Shim J. S., Kubota A., Imaizumi T., Plant Physiol. 2017, 173, 5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Tiwari S. B., Shen Y., Chang H. C., Hou Y., Harris A., Ma S. F., McPartland M., Hymus G. J., Adam L., Marion C., New Phytol. 2010, 187, 57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Samach A., Onouchi H., Gold S. E., Ditta G. S., Schwarz‐Sommer Z., Yanofsky M. F., Coupland G., Science 2000, 288, 1613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Yoo S. K., Chung K. S., Kim J., Lee J. H., Hong S. M., Yoo S. J., Yoo S. Y., Lee J. S., Ahn J. H., Plant Physiol. 2005, 139, 770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Meng J., Wang L., Wang J., Zhao X., Cheng J., Yu W., Jin D., Li Q., Gong Z., Plant Physiol. 2018, 177, 652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Chen Y., Zou T., McCormick S., Plant Physiol. 2016, 172, 244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Mao D., Yu F., Li J., Van de Poel B., Tan D., Li J., Liu Y., Li X., Dong M., Chen L., Li D., Luan S., Plant, Cell Environ. 2015, 38, 2566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Clough S. J., Bent A. F., Plant J. 1998, 16, 735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Su D., Chan C. T., Gu C., Lim K. S., Chionh Y. H., McBee M. E., Russell B. S., Babu I. R., Begley T. J., Dedon P. C., Nat. Protoc. 2014, 9, 828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Li H., Handsaker B., Wysoker A., Fennell T., Ruan J., Homer N., Marth G., Abecasis G., Durbin R., 1000 Genome Project Data Processing Subgroup , Bioinformatics 2009, 25, 2078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Liao Y., Smyth G. K., Shi W., Nucleic Acids Res. 2019, 47, e47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Liao Y., Smyth G. K., Shi W., Bioinformatics 2014, 30, 923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Love M. I., Huber W., Anders S., Genome Biol. 2014, 15, 550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Tang A. D., Soulette C. M., van Baren M. J., Hart K., Hrabeta‐Robinson E., Wu C. J., Brooks A. N., Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 1438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Cui X., Liang Z., Shen L., Zhang Q., Bao S., Geng Y., Zhang B., Leo V., Vardy L. A., Lu T., Gu X., Yu H., Mol. Plant 2017, 10, 1387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Wang P., Doxtader K. A., Nam Y., Mol. Cell 2016, 63, 306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Meyer K., Koster T., Nolte C., Weinholdt C., Lewinski M., Grosse I., Staiger D., Genome Biol. 2017, 18, 204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supporting Information

Supplemental Table S1‐S6

Data Availability Statement

The nanopore direct RNA sequencing data described in this study have been deposited in NCBI Sequence Read Archive (SRA) database with the accession number: PRJNA749003. All the other data are available from the corresponding authors upon request.

The data that support the findings of this study are openly available in NCBI Sequence Read Archive (SRA) database at https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra/PRJNA749003, reference number 749003.