Abstract

Background/Aims

Stargardt disease is a rare, inherited, degenerative disease of the retina that is the most common type of hereditary macular dystrophy. Currently, no approved treatments for the disease exist. The purpose of this study was to characterise the pharmacodynamics of emixustat, an orally available small molecule that targets the retinal pigment epithelium–specific 65 kDa protein (RPE65), in subjects with macular atrophy secondary to Stargardt disease.

Methods

In this multicentre study conducted at six study sites in the USA, 23 subjects with macular atrophy secondary to Stargardt disease were randomised to one of three doses of daily emixustat (2.5 mg, 5 mg or 10 mg) and treated for 1 month. The primary outcome was the suppression of the rod b-wave recovery rate on electroretinography after photobleaching, which is an indirect measure of RPE65 inhibition.

Results

Subjects who received 10 mg emixustat showed near-complete suppression of the rod b-wave amplitude recovery rate postphotobleaching (mean=91.86%, median=96.69%), whereas those who received 5 mg showed moderate suppression (mean=52.2%, median=68.0%). No effect was observed for subjects who received 2.5 mg emixustat (mean=−3.31%, median=−12.23%). The adverse event profile was consistent with prior studies in other patient populations and consisted primarily of ocular adverse events likely related to RPE65 inhibition.

Conclusion

This study demonstrated dose-dependent suppression of rod b-wave amplitude recovery postphotobleaching, confirming emixustat’s biological activity in patients with Stargardt disease. These findings informed dose selection for a 24-month phase 3 trial (SeaSTAR Study) that is now comparing emixustat to placebo in the treatment of Stargardt disease-associated macular atrophy.

Keywords: clinical trial, drugs, electrophysiology, retina, macula

Introduction

Stargardt disease (STGD) is a rare, inherited, degenerative disease of the retina that affects 1 in 8000–10 000 individuals, making it the most common type of hereditary macular dystrophy.1 It typically causes vision loss during childhood or adolescence, progressing slowly over time until an individual’s vision is 20/200 or worse. Currently, a pressing need exists for novel therapies for STGD, as no approved treatments for the disease exist.

The vast majority of STGD cases are type 1 (STGD1) and caused by mutations of the ABCA4 gene, in contrast to ELOVL4 (STGD3) and PROM1-associated STGD4.2–5 ABCA4 encodes a protein that transports a precursor of toxic bis-retinoids (N-retinylidene-phosphatidylethanoloamine (PE), which consists of one molecule of PE covalently bound to one molecule of 11-cis- or all-trans-retinal) from the lumen side of photoreceptor disc membranes to the cytoplasmic side, where the retinal is hydrolysed from PE.6 When ABCA4 is mutated, this precursor molecule accumulates in disc membranes, is phagocytised by retinal pigment epithelium cells, and is eventually converted into toxic bis-retinoids such as N-retinylidene-N-retinylethanolamine (A2E). Build-up of toxic bis-retinoids can lead to loss of function or death of the retinal pigment epithelium.6 This, in turn, leads to the dysfunction of both rod and cone photoreceptors,7 8 their eventual death and permanent loss in vision.

Evidence suggests that emixustat hydrochloride may protect against the retinal damage that occurs in STGD. Emixustat is an orally available small molecule that targets the retinal pigment epithelium-specific 65 kDa protein (RPE65), reducing the production of visual chromophore (11-cis-retinal) in a dose-dependent and reversible manner.9 By depleting 11-cis-retinal, and thus all-trans-retinal, the substrates necessary for the production of toxic bis-retinoids such as A2E, emixustat decreases the rate at which these harmful molecules accumulate in the retinal pigment epithelium. In an ABCA4-/- mouse model of STGD, in which excessive A2E accumulates in the retinal pigment epithelium, treating young mice with emixustat for 3 months significantly reduces A2E accumulation when compared with vehicle treatment.10

The primary objective of this study was to characterise the pharmacodynamic effects of emixustat on electroretinography (ERG) in subjects with macular atrophy (MA) secondary to STGD, when the drug was administered orally for 1 month. The rod b-wave amplitude of the ERG is regarded as a reliable measure of signal processing in the retina and represents the extent of rhodopsin regeneration.11 There is a proportional relationship between the magnitude of the rod b-wave amplitude and rhodopsin levels.12 Reduction of the rod b-wave amplitude indicates a reduction in rhodopsin, and thus 11-cis-retinal, levels. Following exposure to a bright bleaching light, the rod b-wave amplitude is reduced, but recovers over approximately 30 min. The rate of recovery over time reflects the regeneration rate of rhodopsin, and hence 11-cis-retinal, which is governed by RPE65 activity.13 Thus, assessing the effects of emixustat on rod recovery after photobleach is an indirect measure of RPE65 inhibition.

Materials and methods

Study design

This multicentre, randomised, double-masked study was conducted from January to November 2017 at six study sites in the USA, at which subjects with MA secondary to STGD were assigned to one of three doses of emixustat (2.5 mg, 5 mg or 10 mg) and treated daily for 1 month. The three emixustat doses were selected based on experience in prior clinical trials.14 15 The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA), and the basic principles of the International Council for Harmonisation (ICH) E6 (R1) Guideline for Good Clinical Practice. All subjects provided written informed consent before study-specific procedures began. This study was registered with ClinicalTrials.gov as NCT03033108.

Participants

The study planned to enrol approximately 30 subjects, with the goal of having 24 (8 per treatment group) complete the masked treatment phase.

Inclusion criteria included

Ability to provide informed consent.

≥18 years of age.

Clinical diagnosis of MA secondary to STGD in one or both eyes, with one or more pathogenic mutations of the ABCA4 gene. If only one pathogenic mutation was detected, a typical fleck phenotype was required.

Total area of MA (definitely decreased autofluorescence (DDAF) plus questionably decreased autofluorescence (QDAF) on reduced-illuminance fundus autofluorescence (RI-FAF)16 17 in the study eye equal to 1.25–26 mm2, as measured by a central image reading centre (Duke Reading Center, Durham, North Carolina, USA).

Early treatment diabetic retinopathy study best-corrected visual acuity (BCVA) of ≥20 letters in the study eye.

Ability to administer oral medication by self or with available assistance.

The original study protocol, which limited the total area of MA to 1.25–18 mm2 of DDAF, was amended to the criterion above, as this allowed enrolment of a broader population of subjects with STGD by including larger lesions and those containing QDAF, an earlier stage of MA than DDAF.18 Reliable measurement of QDAF can be challenging as the borders may be poorly demarcated.19 All RI-FAF images were obtained with the Heidelberg SPECTRALIS; and all areas of MA were measured using Heidelberg RegionFinder software.

Exclusion criteria included

MA associated with a condition other than STGD in either eye.

Active ocular disease that compromised or confounded visual function (eg, choroidal neovascularisation, diabetic retinopathy, uveitis).

Any intraocular or ocular surface surgery within 3 months of screening.

If both of a subject’s eyes qualified for study, the investigator selected the eye with the larger MA lesion; if both eyes had an equal MA lesion area, the right eye was selected.

Randomisation and masking

Subjects were randomly assigned to daily treatment with emixustat 2.5, 5, or 10 mg in a 1:1:1 ratio. The randomisation schedule was computer generated using permuted blocks and included stratification by study site. It was uploaded to an interactive web response system where qualified subjects were sequentially assigned to the next available randomisation number by a member of the study site staff. The appropriate masked medication was then given to the subject using a preassigned kit number. Emixustat tablets were all identical in appearance and dispensed in identical packaging, and study subjects, investigators and staff, and other individuals involved in the conduct, monitoring and analysis of the study were masked to the identity of treatment assignments until after the final database was locked.

Procedures

Subjects were treated with the assigned dose of emixustat every evening for 1 month. Scheduled visits included screening (within 30 days prior to baseline), baseline (day 1), end of treatment (EoT; day 30) and study exit (30 days after EoT).

Full-field ERG was performed for each eye in all subjects at baseline and EoT. Identical ERG systems were used at each study site (Diagnosys, Lowell, Massachusetts, USA). ERG data were sent to a central ERG reading centre (Retina Foundation of the Southwest, Dallas, Texas, USA) to be evaluated. Briefly, the ERG procedure began with the subject’s pupils being maximally dilated, followed by a period of dark adaptation that lasted for at least 30 min. At the end of this period, an electrode (Dawson Trick Litskow fibre) was placed on each eye under dim red light, and a rod response and a maximal response (mixed) ERG were recorded. Following a single-flash cone response and 31 Hz flicker response at the end of a 10 min period of light adaptation, subjects underwent photobleaching for a period of 3 min. Rod responses were recorded immediately after photobleaching and at 10, 20 and 30 min following the photobleaching.

Assessments performed only at screening included ABCA4 genotyping (Molecular Vision Lab, Hillsboro, Oregon, USA) and RI-FAF (performed on a Heidelberg Spectralis). At screening, baseline, EoT, and study exit, BCVA, slit-lamp biomicroscopy, and dilated ophthalmoscopy were performed. At screening and EoT, physical examination, vital signs, electrocardiography, clinical laboratory tests and intraocular pressure were performed.

Outcomes

The study’s primary outcome was the percent suppression of rod b-wave recovery rate after photobleaching at the end of the 1-month treatment period, compared with baseline. This was defined as the percent decrease from baseline in the rod b-wave amplitude recovery rate (slope in µv/minute) over 30 min postphotobleaching, as measured by ERG. The percent suppression prebleach was defined as the percent reduction in the pre-bleach b-wave amplitude (μV) at month 1 relative to baseline. The secondary outcomes were (1) incidence, severity, seriousness of and discontinuations due to adverse events (AEs); and (2) changes from baseline in laboratory values, vital signs, physical examination findings, ECGs and ophthalmic assessments. All AEs had their verbatim terms mapped to the corresponding thesaurus terms using the Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities coding dictionary, V.20.1.

Statistical methods

The study’s pharmacodynamic analysis included all randomised subjects who had (1) a baseline ERG and (2) a post-baseline ERG while on study drug that was considered at least partially analyzable by the central ERG reading centre. Continuous and ordinal variables were summarised by the number of observations, arithmetic mean, SD, SE, minimum, median and maximum. Discrete variables were summarised by frequency counts and percentages. The rate of recovery of the ERG response after photobleaching (ERG slope) was quantified for the three treatment groups by fitting a least-squares regression line through the 4 b-wave amplitudes obtained at 0, 10, 20 and 30 min postphotobleaching for each eye separately and averaging the results across eyes for each subject for reporting.

The study’s safety analysis included all randomised subjects who took at least 1 dose of emixustat. All safety endpoints were summarised descriptively.

Results

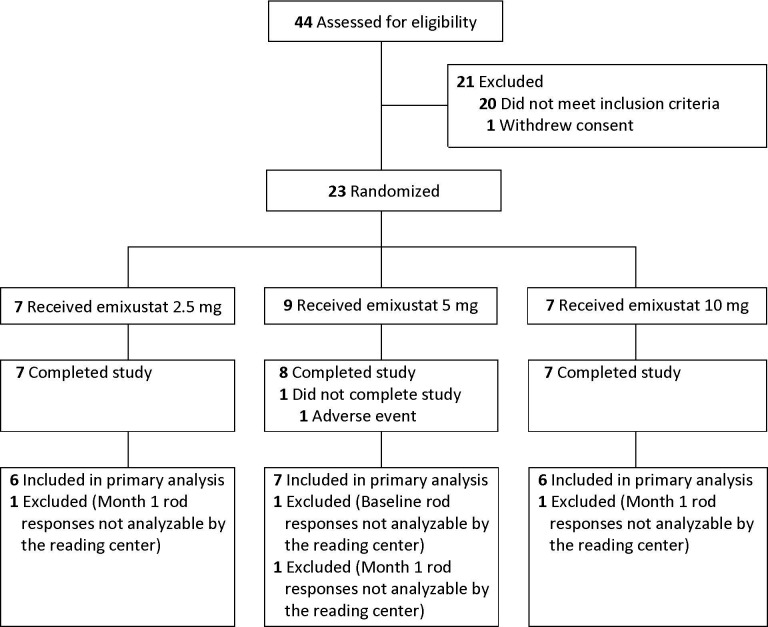

The investigators screened 44 subjects (figure 1). Of these, 21 did not pass the screening process. The 23 remaining subjects were randomised to emixustat treatment: 7–2.5 mg, 9–5 mg and 7–10 mg. All but one subject (from the 5 mg group) completed the study. All study exit visits were completed.

Figure 1.

Disposition of study subjects.

Demographic characteristics were generally comparable between the three treatment groups. More than half of the subjects (15/23, 65.2%) were male, and most were white (18/23, 78.3%). Their mean age was 51.6 years, with an age range of 18–77 years, and more than half of subjects (13/23, 56.5%) were ≥45 years. Overall, study drug compliance was 95.8% and was comparable between the three treatment groups; the majority of subjects (20/23, 87.0%) were >80% compliant, and only one subject (in the 5 mg group) had 25%–50% compliance.

Baseline data were also comparable between the three treatment groups, with the exception of mean total MA area in the study eye, which was largest among subjects treated with 10 mg and smallest in subjects treated with 5 mg (table 1). Of 23 subjects, 5 had one pathogenic ABCA4 mutation and the remaining 18 had two pathogenic ABCA4 mutations. The mean BCVA letter score for subjects’ right eyes was 51.3 and for left eyes was 50.7. Of the 19 subjects with evaluable baseline ERGs, 15 were assessed as Lois group 1.20

Table 1.

Subject baseline characteristics

| Baseline characteristic | Emixustat 2.5 mg (N=7) |

Emixustat 5 mg (N=9) |

Emixustat 10 mg (N=7) |

All subjects (N=23) |

| ABCA4 genotype—n (%) | ||||

| One pathogenic mutation | 1 (14.3) | 2 (22.2) | 2 (28.6) | 5 (21.7) |

| Two pathogenic mutations | 6 (85.7) | 7 (77.8) | 5 (71.4) | 18 (78.3) |

| BCVA—letter score | ||||

| Right eye | ||||

| N | 7 | 9 | 7 | 23 |

| Mean (SD) | 54.9 (23.79) | 52.4 (27.03) | 46.3 (20.84) | 51.3 (23.48) |

| Median | 45.0 | 50.0 | 38.0 | 45.0 |

| Minimum, maximum | 29–84 | 3–89 | 25–83 | 3–89 |

| Left eye | ||||

| N | 7 | 9 | 7 | 23 |

| Mean (SD) | 43.4 (22.17) | 57.8 (23.04) | 49.0 (23.66) | 50.7 (22.76) |

| Median | 39.0 | 64.0 | 40.0 | 43.0 |

| Minimum, maximum | 20–79 | 27–85 | 25–84 | 20–85 |

| Area of macular atrophy (mm2) (study eye) | ||||

| Pre-protocol amendment | ||||

| Total area (DDAF) | ||||

| N | 2 | 4 | 5 | 11 |

| Mean (SD) | 6.80 (0.42) | 11.21 (5.18) | 11.11 (4.90) | 10.36 (4.56) |

| Median | 6.80 | 10.75 | 13.18 | 8.70 |

| Minimum, maximum | 6.50–7.09 | 6.21–17.12 | 3.66–15.10 | 3.66–17.12 |

| Post-protocol amendment | ||||

| Total area (DDAF+QDAF) | ||||

| N | 5 | 5 | 2 | 12 |

| Mean (SD) | 11.42 (9.30) | 3.09 (1.45) | 17.66 (7.96) | 8.99 (8.38) |

| Median | 6.82 | 2.64 | 17.66 | 5.02 |

| Minimum, maximum | 2.50–22.25 | 1.64–5.14 | 12.03–23.29 | 1.64–23.29 |

| Lois ERG group*—n (%) | ||||

| N | 6 | 7 | 6 | 19 |

| Group 1 | 4 (66.7) | 7 (100) | 4 (66.7) | 15 (78.9) |

| Group 2 | 2 (33.3) | 0 | 1 (16.7) | 3 (15.8) |

| Group 3 | 0 | 0 | 1 (16.7) | 1 (5.3) |

*Phenotypes on full-field ERG; a total of 19 subjects had an evaluable ERG at baseline; Group 1 = normal rod and cone function; Group 2 = normal rod function with abnormal cone function; Group 3 = abnormal rod and cone function.

BCVA, best-corrected visual acuity; DDAF, definitely decreased autofluorescence; ERG, electroretinography; QDAF, definitely decreased autofluorescence.

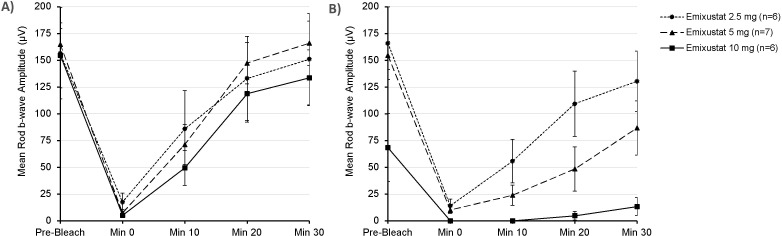

At baseline, the observed mean values for b-wave amplitudes decreased after photobleaching and recovered to near prebleach values by 30 min after photobleaching in all subjects (figure 2A). At EoT, the mean change from baseline (CFB) rod b-wave amplitude before photobleaching was similar in subjects following treatment with 2.5 mg (9.35 μV) and 5 mg (−10.45 μV) and was largest in subjects following treatment with 10 mg (−86.18 μV). For an individual, the criterion for a decrease in rod b-wave amplitude to be significant at the 95% confidence level is 40–46 μV.21 22 The mean decrease from baseline in ERG rod b-wave amplitude 30 min postbleaching was dose dependent. It was largest in subjects treated with 10 mg, followed by subjects treated with 5 mg; it was smallest in subjects treated with 2.5 mg (figure 2B). The mean CFB implicit times for rod response were insignificant, and differences between the treatment groups were not evident (data not shown).

Figure 2.

Mean±SE of the mean rod b-wave amplitudes prior to photobleaching and then over a 30 min period postbleaching at (A) baseline, prior to emixustat treatment and (B) after 1 month of daily treatment with emixustat.

At prebleach, a moderate degree of suppression (50.0%) was observed in the 10 mg treatment group, and no suppression was observed in the 2.5 mg and 5 mg treatment groups. At baseline, the mean rate of recovery after photobleach was similar between the 2.5 mg and 10 mg groups (4.46 and 4.54 μV/minute, respectively) and higher in the 5 mg group (5.58 μV/minute). At month 1, the mean CFB rate of recovery showed dose dependency, with the largest decrease in subjects treated with 10 mg (−4.12 μV/minute), followed by subjects treated with 5 mg (−3.05 μV/minute) and 2.5 mg (−0.42 μV/minute). Thus, subjects treated with 10 mg showed near-complete suppression of the rod b-wave recovery rate post-photobleaching (mean=91.86%, median=96.69%), whereas subjects treated with 5 mg showed a moderate degree of suppression (mean=52.2%, median=68.0%) (table 2). No effect was observed for subjects treated with 2.5 mg (mean=−3.31%, median=−12.23%). The results were consistent between the subjects with one identified ABCA4 mutation (n=5) compared with those with two identified ABCA4 mutations (n=14).

Table 2.

Percent suppression of rod b-wave amplitude recovery rate prebleaching and 30 min postbleaching at month 1, relative to baseline*

| Percent suppression | Emixustat 2.5 mg (N=6) |

Emixustat 5 mg (N=7) |

Emixustat 10 mg (N=6) |

|||

| at month 1 | Prebleach | Postbleach | Prebleach | Postbleach | Prebleach | Postbleach |

| n | 6 | 6 | 7 | 7 | 6 | 6 |

| Mean (SD) | −18.85 (47.02) | −3.31 (41.43) | 4.19 (22.12) | 52.20 (34.99) | 49.98 (41.52) | 91.86 (13.63) |

| SE | 19.20 | 16.91 | 8.36 | 13.22 | 16.95 | 5.56 |

| Median | −11.03 | −12.23 | −3.07 | 68.00 | 49.04 | 96.69 |

| Minimum, maximum | −80.7 to 37.5 | −41.0 to 54.7 | −22.8 to 35.3 | 1.0 to 91.5 | 4.3 to 100.0 | 64.9 to 100.0 |

*A positive percent suppression indicates a decrease from baseline and a negative percent suppression indicates an increase from baseline.

The mean CFB for ERG rod and cone mixed response for b-wave amplitude was larger in subjects following treatment with 10 mg than in subjects treated with 5 mg or 2.5 mg. The mean changes for 5 mg and 10 mg were decreases. The mean CFB b-wave implicit times were small, and no differences could be assessed between the three treatment groups. At month 1, the mean CFB in the single-flash cone response and 31 Hz flicker cone response for b-wave or peak amplitudes, respectively, and implicit times were insignificant (data not shown).

The majority of AEs were ocular (81.6%), with a similar proportion of ocular AEs across all treatment groups. The most common AEs were delayed dark adaptation (11/23, 47.8%), erythropsia (5/23, 21.7%), vision blurred (4/23, 17.4%) and photophobia and visual impairment (3/23, 13.0%) (table 3). Delayed dark adaptation was more frequent in the 5 mg and 10 mg groups. Headache was the only non-ocular treatment-emergent AE (TEAE) reported in >1 subject (present in two subjects). Of the 49 AEs, 39 were considered related to the study drug; the number of study drug-related AEs and proportion of subjects experiencing study drug-related AEs were comparable between subjects in the 5 mg and 10 mg groups and lower in subjects in the 2.5 mg group.

Table 3.

Summary of adverse events that occurred in three or more subjects overall*

| Adverse event | Emixustat 2.5 mg (N=7) n (%) |

Emixustat 5 mg (N=9) n (%) |

Emixustat 10 mg (N=7) n (%) |

All subjects (N=23) n (%) |

| Any adverse event | 6 (85.7) | 8 (88.9) | 7 (100) | 21 (91.3) |

| Delayed dark adaptation | 1 (14.3) | 6 (66.7) | 4 (57.1) | 11 (47.8) |

| Erythropsia | 1 (14.3) | 3 (33.3) | 1 (14.3) | 5 (21.7) |

| Vision blurred | 2 (28.6) | 1 (11.1) | 1 (14.3) | 4 (17.4) |

| Photophobia | 1 (14.3) | 2 (22.2) | 0 | 3 (13.0) |

| Visual impairment | 1 (14.3) | 1 (11.1) | 1 (14.3) | 3 (13.0) |

*Percentages were based on the total number of subjects enrolled in each treatment group for the safety analysis set (N).

One subject, in the 5 mg group, experienced 3 TEAEs (delayed dark adaptation, night blindness, vision blurred), which led to study discontinuation; these TEAEs were of mild severity and were considered related to study drug. No subject experienced a serious AE during the study.

With regard to changes from baseline in safety assessments—including slit-lamp biomicroscopy, dilated ophthalmoscopy, intraocular pressure, clinical laboratory tests, physical examinations, vital signs or ECGs—few clinically relevant findings were observed. Across the study, mean and median changes in BCVA from baseline were small, with a range of −11 to +9 letters.

Discussion

The primary objective of this study was to characterise the pharmacodynamics of emixustat in subjects with MA secondary to STGD. After being randomised to 1 month of daily treatment with emixustat at one of three doses (2.5 mg, 5 mg or 10 mg), subjects exhibited dose-dependent suppression of rod b-wave amplitude recovery postphotobleaching, with near-complete suppression at 10 mg but minimal to no suppression at 2.5 mg. This finding provides evidence of dose-dependent inhibition of RPE65 with emixustat in this population. Meaningful changes were not observed in single-flash cone response or 31 Hz flicker cone response. The lack of cone effect under these conditions may be attributable to the fact that cones also receive 11-cis-retinal from a cone-specific visual cycle.23 24

Consistent with the results of this study in STGD patients, emixustat has also demonstrated a biologic effect on the retina in prior studies in healthy subjects25 and in subjects with geographic atrophy secondary to age-related macular degeneration,14 as evidenced by dose-dependent suppression of rod recovery on ERG after photobleaching. In these studies, the effects of emixustat on rod ERG were reversed after drug cessation; no effects on cone function were demonstrated on or off the drug.

The safety profile observed was also consistent with prior clinical trials in both healthy volunteers and patients with geographic atrophy secondary to age-related macular degeneration.14 15 25 26 The most common AEs in this study were ocular in nature, and the most common ocular AEs (delayed dark adaptation, erythropsia, vision blurred, photophobia, visual impairment) are consistent with emixustat’s mechanism of action (inhibition of RPE65, resulting in decreased availability of 11-cis-retinal to photoreceptors). Consistent with the lack of effect on ERG with 2.5 mg, there were lower incidences of delayed dark adaptation and study drug-related AEs in the 2.5 mg group.

On the basis of demographic and baseline characteristics, the population studied in this trial appears to be representative of STGD patients more generally, though the subjects in this study may be older than the average STGD patient enrolled in clinical trials. In the recent ProgStar study, the largest natural history study of STGD carried out to date, mean age at study entry was 33 years.27 The mean age of subjects in the current study was 52 years old. In terms of race and ethnicity, subjects in this study were similar to those enrolled in ProgStar. In addition, the areas of decreased autofluorescence on RI-FAF in this study fell within the range seen in ProgStar.

Limitations of this study include the small sample size and the inherent, significant intersubject and intrasubject variability observed in ERGs.22 These issues, in addition to the significant genetic and phenotypic variability across the STGD population,27 could limit the ability to apply the results of this study to the broader STGD population. However, the results of this study did demonstrate clear differences between the dose groups.

The results of this study informed the dose selection for an ongoing, 24-month clinical trial [Safety and efficacy of EmixustAt in STARgardt disease (SeaSTAR) Study] comparing emixustat to placebo for the treatment of MA secondary to STGD (NCT03772665). This phase 3, randomised, double-masked, international trial is now investigating the effects of a 10 mg daily dose of emixustat on the mean rate of change in subjects’ total area of MA. If emixustat is shown to slow the growth of MA secondary to STGD disease, it could represent the first effective treatment for this condition.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the Protocol 4429-204 investigators: Paul Bernstein (Moran Eye Center, University of Utah, Salt Lake City, Utah, USA), Karl Csaky (Retina Foundation of the Southwest, Dallas, Texas, USA), Kanishka Thiran Jayasundera (W.K. Kellogg Eye Center, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan, USA), Byron Lam (Bascom Palmer Eye Institute, University of Miami-Miller School of Medicine, Miami, Florida, USA), Mandeep Singh (Wilmer Eye Institute, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, Maryland, USA), and Elias Traboulsi (Cole Eye Institute, Cleveland Clinic, Cleveland, Ohio, USA). The authors also thank Kristin Harper, PhD, of Harper Health & Science Communications, for providing writing and editorial support in accordance with Good Publication Practice (GPP3) guidelines.

Footnotes

Contributors: All authors contributed to the research design of the study, the analysis and interpretation of the study results, and the revision and review of the manuscript. JG contributed to study administration and supervision, and JMK contributed to the data analysis. All authors approved the final manuscript as submitted and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Funding: Funding for the study was provided solely by Kubota Vision. This study was registered with ClinicalTrials.gov as NCT03033108.

Competing interests: RK, JKG and JMK are employees of Kubota Vision. RK has pending and issued patents related to emixustat hydrochloride. DGB received grants from Kubota Vision during the conduct of the study.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement

No data are available. The drug being tested in this clinical trial is investigational, and the data are proprietary and may be part of future regulatory submissions. Therefore, the data cannot be made available at this time.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not required.

Ethics approval

The protocol and informed consent forms were prospectively approved by either a central institutional review board (IRB; Chesapeake IRB) or site-specific IRBs (University of Utah IRB, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine IRB, and the Cleveland Clinic IRB).

References

- 1. Tanna P, Strauss RW, Fujinami K, et al. Stargardt disease: clinical features, molecular genetics, animal models and therapeutic options. Br J Ophthalmol 2017;101:25–30. 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2016-308823 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Briggs CE, Rucinski D, Rosenfeld PJ, et al. Mutations in ABCR (ABCA4) in patients with Stargardt macular degeneration or cone-rod degeneration. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2001;42:2229–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Rivera A, White K, Stöhr H, et al. A comprehensive survey of sequence variation in the ABCA4 (ABCR) gene in Stargardt disease and age-related macular degeneration. Am J Hum Genet 2000;67:800–13. 10.1086/303090 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Zernant J, Xie YA, Ayuso C, et al. Analysis of the ABCA4 genomic locus in Stargardt disease. Hum Mol Genet 2014;23:6797–806. 10.1093/hmg/ddu396 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Braun TA, Mullins RF, Wagner AH, et al. Non-exomic and synonymous variants in ABCA4 are an important cause of Stargardt disease. Hum Mol Genet 2013;22:5136–45. 10.1093/hmg/ddt367 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Molday RS, Zhong M, Quazi F. The role of the photoreceptor ABC transporter ABCA4 in lipid transport and Stargardt macular degeneration. Biochim Biophys Acta 2009;1791:573–83. 10.1016/j.bbalip.2009.02.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Cideciyan AV, Swider M, Aleman TS, et al. Abca4 disease progression and a proposed strategy for gene therapy. Hum Mol Genet 2009;18:931–41. 10.1093/hmg/ddn421 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Strauss RW, Kong X, Bittencourt MG, et al. Scotopic microperimetric assessment of rod function in Stargardt disease (smart) study: design and baseline characteristics (report No. 1). Ophthalmic Res 2019;61:36–43. 10.1159/000488711 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kubota R, Gregory J, Henry S, et al. Pharmacotherapy for metabolic and cellular stress in degenerative retinal diseases. Drug Discov Today 2020;25:30455–6. 10.1016/j.drudis.2019.11.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Bavik C, Henry SH, Zhang Y, et al. Visual cycle modulation as an approach toward preservation of retinal integrity. PLoS One 2015;10:e0124940. 10.1371/journal.pone.0124940 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Brown KT, Wiesel TN. Localization of origins of electroretinogram components by intraretinal recording in the intact cat eye. J Physiol 1961;158:257–80. 10.1113/jphysiol.1961.sp006768 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Bonting SL, Caravaggio LL, Gouras P. The rhodopsin cycle in the developing vertebrate retina. Exp Eye Res 1961;1:14–24. 10.1016/S0014-4835(61)80004-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Lee KA, Nawrot M, Garwin GG, et al. Relationships among visual cycle retinoids, rhodopsin phosphorylation, and phototransduction in mouse eyes during light and dark adaptation. Biochemistry 2010;49:2454–63. 10.1021/bi1001085 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Dugel PU, Novack RL, Csaky KG, et al. Phase II, randomized, placebo-controlled, 90-day study of EMIXUSTAT hydrochloride in geographic atrophy associated with dry age-related macular degeneration. Retina 2015;35:1173–83. 10.1097/IAE.0000000000000606 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Rosenfeld PJ, Dugel PU, Holz FG, et al. Emixustat hydrochloride for geographic atrophy secondary to age-related macular degeneration. Ophthalmology 2018;125:1556–67. 10.1016/j.ophtha.2018.03.059 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kuehlewein L, Hariri AH, Ho A, et al. Comparison of manual and semiautomated fundus autofluorescence analysis of macular atrophy in Stargardt disease phenotype. Retina 2016;36:1216–21. 10.1097/IAE.0000000000000870 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Cideciyan AV, Swider M, Aleman TS, et al. Reduced-illuminance autofluorescence imaging in ABCA4-associated retinal degenerations. J Opt Soc Am A Opt Image Sci Vis 2007;24:1457–67. 10.1364/JOSAA.24.001457 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Strauss RW, Muñoz B, Ho A, et al. Progression of Stargardt disease as determined by fundus autofluorescence in the retrospective progression of Stargardt disease study (ProgStar report No. 9). JAMA Ophthalmol 2017;135:1232–41. 10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2017.4152 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Strauss RW, Muñoz B, Jha A, et al. Comparison of short-wavelength reduced-illuminance and conventional autofluorescence imaging in Stargardt macular dystrophy. Am J Ophthalmol 2016;168:269–78. 10.1016/j.ajo.2016.06.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Lois N, Holder GE, Bunce C, et al. Phenotypic subtypes of Stargardt macular dystrophy-fundus flavimaculatus. Arch Ophthalmol 2001;119:359–69. 10.1001/archopht.119.3.359 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Birch DG, Hood DC, Locke KG, et al. Quantitative electroretinogram measures of phototransduction in cone and rod photoreceptors: normal aging, progression with disease, and test-retest variability. Arch Ophthalmol 2002;120:1045–51. 10.1001/archopht.120.8.1045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Grover S, Fishman GA, Birch DG, et al. Variability of full-field electroretinogram responses in subjects without diffuse photoreceptor cell disease. Ophthalmology 2003;110:1159–63. 10.1016/S0161-6420(03)00253-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Mata NL, Radu RA, Clemmons RC, et al. Isomerization and oxidation of vitamin A in cone-dominant retinas: a novel pathway for visual-pigment regeneration in daylight. Neuron 2002;36:69–80. 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)00912-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Sato S, Kefalov VJ. cis Retinol oxidation regulates photoreceptor access to the retina visual cycle and cone pigment regeneration. J Physiol 2016;594:6753–65. 10.1113/JP272831 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Kubota R, Boman NL, David R, et al. Safety and effect on rod function of ACU-4429, a novel small-molecule visual cycle modulator. Retina 2012;32:183–8. 10.1097/IAE.0b013e318217369e [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Kubota R, Al-Fayoumi S, Mallikaarjun S, et al. Phase 1, dose-ranging study of EMIXUSTAT hydrochloride (ACU-4429), a novel visual cycle modulator, in healthy volunteers. Retina 2014;34:603–9. 10.1097/01.iae.0000434565.80060.f8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Strauss RW, Ho A, Muñoz B, et al. The natural history of the progression of atrophy secondary to Stargardt disease (ProgStar) studies: design and baseline characteristics: ProgStar report No. 1. Ophthalmology 2016;123:817–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

No data are available. The drug being tested in this clinical trial is investigational, and the data are proprietary and may be part of future regulatory submissions. Therefore, the data cannot be made available at this time.