Abstract

Introduction

The majority of people living with type 1 diabetes (PLWT1D) struggle to access high-quality care in low-income countries (LICs), and lack access to technologies, including continuous glucose monitoring (CGM), that are considered standard of care in high resource settings. To our knowledge, there are no studies in the literature describing the feasibility or effectiveness of CGM at rural first-level hospitals in LICs.

Methods and analysis

This is a 3-month, 2:1 open-randomised trial to assess the feasibility and clinical outcomes of introducing CGM to the entire population of 50 PLWT1D in two hospitals in rural Neno, Malawi. Participants in both arms will receive 2 days of training on diabetes management. One day of training will be the same for both arms, and one will be specific to the diabetes technology. Participants in the intervention arm will receive Dexcom G6 CGM devices with sensors and solar chargers, and patients in the control arm will receive Safe-Accu home glucose metres and logbooks. All patients will have their haemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) measured and take WHO Quality of Life assessments at study baseline and endline. We will conduct qualitative interviews with a selection of participants from both arms at the beginning and end of study and will interview providers at the end of the study. Our primary outcomes of interest are fidelity to protocols, appropriateness of technology, HbA1c and severe adverse events.

Ethics and dissemination

This study is approved by National Health Sciences Research Committee of Malawi (IRB Number IR800003905) and the Mass General Brigham (IRB number 2019P003554). Findings will be disseminated to PLWT1D through health education sessions. We will disseminate any relevant findings to clinicians and leadership within our study catchment area and networks. We will publish our findings in an open-access peer-reviewed journal.

Trial registration number

PACTR202102832069874.

Keywords: general diabetes, diabetes & endocrinology, epidemiology, public health

Strengths and limitations of this study.

First randomised controlled trial to study use of continuous glucose monitoring (CGM) in a rural first level hospital in a low-income country.

Will enrol entire population of known people living with type 1 diabetes in two hospitals in Neno District, Malawi.

Will include interviews with patients living with type 1 diabetes and providers to contextualise acceptability and challenges of using CGM.

Because this is the entire population of people living with type 1 diabetes, it is limited sample size.

Introduction

Type 1 diabetes (T1D) is a severe autoimmune condition where the pancreas produces insufficient insulin.1 In sub-Saharan Africa T1D prevalence, while low, is thought to be increasing.2 People living with T1D (PLWT1D) require uninterrupted access to insulin to survive, as well as tools for glucose monitoring and continuous access to education and healthcare services to attain glycaemic control and prevent long-term complications. PLWT1D without access to proper care generally do not survive 1 year.3 Both premature death and diabetes-related complication rates are significantly higher in low and lower middle income countries due to challenges with access to care and supplies.4 Ogle et al defined guidelines for minimal, intermediate and comprehensive levels of care for PLWT1D, and proposed intermediate level of care as an achievable goal for resource-limited settings that could decrease premature mortality and complication rates.5 Intermediate care includes multiple daily injections of insulin, checking blood glucose 2–4 times per day, consistent point-of-care haemoglobin A1c (HbA1c), complication screening and a team approach to diabetes education and support.

The majority of PLWT1D are unable to access intermediate care in low-income countries (LICs), with care mostly restricted to national or regional centres.2 4 6 7 Recent efforts have begun to increase access and lower the costs of care by decentralising services to primary hospitals through nurse-led integrated delivery models called PEN-Plus.8 Consistent with intermediate care described in Ogle et al, the standard of care within PEN-Plus currently includes self-monitoring of blood glucose (SMBG) by glucose metres. However, we acknowledge that there are challenges in patient adherence to bringing the device and log book to clinic visits. Patients may also not adhere to the SMBG schedule. Thus, there is a need for more innovation at rural decentralised clinics to advance the standard of care particularly around glucose monitoring at home. At this stage, it is critical to establish viable strategies to improve glycaemic control for patients with T1D as PEN-Plus is adapted and scaled throughout Africa.

New advancements in blood glucose management technology, namely real-time continuous glucose monitoring (CGM), allow for patients’ glucose levels to be automatically recorded throughout the day and reviewed by the patient in real time and at home to look at patterns throughout the day or uploaded for the clinician to review at the clinic. This technology has been shown to significantly reduce HbA1c values and median duration of hypoglycaemia by allowing uniform tracking of the glucose concentrations in the body’s interstitial fluid.9 This near real-time glucose data can be used to inform and direct precise diabetes management.10 A Cochrane review of CGM systems for the management of PLWT1D showed a statistically significant average decline in HbA1c levels 6 months after baseline for patients who started on CGM therapy at the time of the study.11 Additionally, a recent international consensus statement on the use of CGM technology in the clinical management of diabetes concluded that CGM data should be considered for use to help patients with diabetes improve glycaemic control provided that appropriate educational and technical support is available.10 While these studies indicate significant benefits that CGM therapy can achieve in the management of patients with T1D, they are conducted in high-income countries where robust health systems and a higher familiarity with technology and data-informed self-management are more common. Additionally, many of the studies included patients utilising CGM sensor augmented insulin pump therapy, a therapy not largely available in low-resource settings at this time.

Currently, no data exist on the feasibility and clinical impact of CGM for PLWT1D in rural, low-resource settings, especially in areas that experience a lack of electricity, literacy and data-informed self-management. In one randomised controlled trial on the clinical benefits of CGM technology in the management of women with gestational diabetes at an urban tertiary facility in Malaysia, 22 of the 81 eligible participants refused to participate in the study due to inconvenience (n=6) and refusal of the CGM intervention (n=16).12 Even at this urban facility in a middle-income country, there are potential barriers to the feasibility of delivering CGM technology. An observational study of flash CGM use in PLWT1D in urban East African youth was able to complete follow-up on 68 of 78 participants and found CGM to be feasible in this setting.13 This study aims to assess the feasibility and clinical impact of CGM use among patients with T1D with limited literacy receiving care at rural first-level hospitals in an LIC.

Objectives

The objectives of this study are to: (1) assess the feasibility of CGM use among a rural population of patients with T1D and limited literacy in an LIC; (2) determine the effectiveness of CGM on diabetes clinical outcomes among patients with T1D in LICs using clinical endpoints and (3) determine variability in the SD of HbA1C in order to inform further studies.

Methods and analysis

This protocol is reported following the Standard Protocol Items Recommendations for Interventional Trials.

Study setting

This study will be conducted at two rural first-level hospitals in Neno, Malawi. Neno District in southern Malawi has a population of about 138 000 people, who mostly rely on subsistence agriculture. Neno has two Ministry of Health (MOH) hospitals: one district hospital in the centre of Neno, and a community hospital in Lisungwi. Since 2007, Partners In Health (PIH), a US-based non-government organisation known locally as Abwenzi Pa Za Umoyo, has partnered with the MOH to improve healthcare and socioeconomic development in Neno District. In 2018, Neno District opened two advanced non-communicable disease (NCD) clinics at each of the first-level hospitals. The clinics provide high-quality care for complex NCDs, consistent with the PEN-Plus model.8 Patients with T1D are enrolled in this clinic and receive care from mid-level providers (clinical officers) with specialised training in NCDs. All insulin is provided free of charge to all patients at their routine monthly appointments. In addition, every household in Neno is assigned a community health worker (CHW) who visit households monthly for education and screening for multiple common conditions, enrolment into maternal and chronic care, and accompaniment to clinic. PLWT1D are supported through more frequent visits, when CHWs conduct treatment and adherence counselling, identification of side effects or danger signs, and missed visit tracking.

Study design

This is a 3-month feasibility 2:1 parallel arm open-randomised control study to assess the feasibility and impact of CGM among PLWT1D in two rural hospitals in Neno, Malawi.

Prior to the start of data collection, NCD clinicians will partake in a 1-week training on the study protocol as it applies to the use of CGM, glucose metres and logbooks. Providers will have the opportunity to wear a Dexcom device as part of their training to familiarise themselves with the technology. Initial education will be followed up by real-time, ongoing digital training every 2 weeks.

The trial will consist of two arms in a 2:1 ratio (intervention to comparison). In the intervention group participants will be given the CGM Dexcom G6 model with transmitters, receivers and solar charges.

The comparator group is to be given Safe-Accu glucose metres, Safe-Accu test strips, lancets and locally made logbooks, which are increasingly being used in low-resource settings and are the current standard of care in Neno. This comparator intervention was used as it has been shown to be feasible and effective in LICs14 and does not require the level of resources or training that CGM does.

At the beginning of the trial, both arms will attend a 2-day training for participants, their families and CHWs. Training related to diabetes management will be adapted from the International Society for Pediatric and Adolescent Diabetes and Life for a Child curriculum.15 On the first training day, all participants will receive training in a culturally appropriate manner on diabetes management including: diabetes symptom recognition, insulin treatment, managing hypoglyacaemia, sick day management, blood glucose monitoring, nutritional management, physical activity management and dispelling of myths and false beliefs surrounding diabetes. On the second day, each arm will receive specialised training related to either CGM or home glucose metres, including a refresher of the first day’s material regarding safe diabetes management in the context of using a CGM or glucose metre.

Participants in both groups will be expected to attend at least monthly follow-up clinic visits. For participants in the treatment group, clinicians will use the Dexcom computer software CLARITY to upload CGM data, create reports, and review data to inform their management of T1D.

For those in the control group, participants will be required to bring their glucose metre machines and logbooks to monthly visits, consistent with current practice. During these visits the study staff will assess the utilisation of the log book by checking completeness as per the expected number of recordings. The utilisation of the glucose metre will be assessed by reviewing the historical memory. To check the validity of the log book records, the records in the log book will be compared by study staff to those in the glucose metre memory including the time and readings of the glucose levels.

In line with current practice, we will not be encouraging patients to self-titrate. We are instead focusing on encouraging providers to help patients problem-solve possible scenarios around diabetes management that may require adjusting insulin doses (eg, food insecurity and illness). All participants will receive routine T1D care including regular blood tests for HbA1c every 3 months. Thus, all participants will receive HbA1c testing at enrolment and on conclusion of the study period.

At the beginning and end of the study, we will conduct semistructured interviews with 3–4 purposively selected participants from both arms to ask about their experiences with living with and managing their T1D and their experience utilising CGM if in the treatment group.

Randomisation and allocation

Sequence generation: The research coordinator based in Neno will randomise subjects using a random number table.

Allocation concealment: Allocation will be concealed through the use of sealed envelopes. The research coordinator will be responsible for the allocation at all sites, and this person will not have access to the subject records.

Due to the nature of the study blinding will not be possible.

Eligibility criteria

We will enrol all eligible participants in the respective T1D programmes from the PIH supported districts. Any patient diagnosed with T1D will be eligible to participate. The inclusion and exclusion criteria will be as follows:

Inclusion criteria: a T1D diagnosis; enrolled in the NCD programme at the mentioned PIH-supported MOH facilities.

Exclusion criteria: pregnant; inability of subject or care provider to use transmitter and applicator.

Eligible participants will be identified through electronic medical records, chart review or referred to the study staff by the NCD clinicians. The study staff will then contact the participants either during routine follow-up visits or phone calls to obtain informed consent to participate in the study. All participants will be required to sign an informed consent form on the day of enrolment (online supplemental appendix A). Assent will be collected from children under the age of 18 (online supplemental appendix B). Patients will be enrolled regardless of literacy. No patients with mental impairment will be included.

bmjopen-2021-052134supp001.pdf (109.6KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2021-052134supp002.pdf (92.5KB, pdf)

Sample size

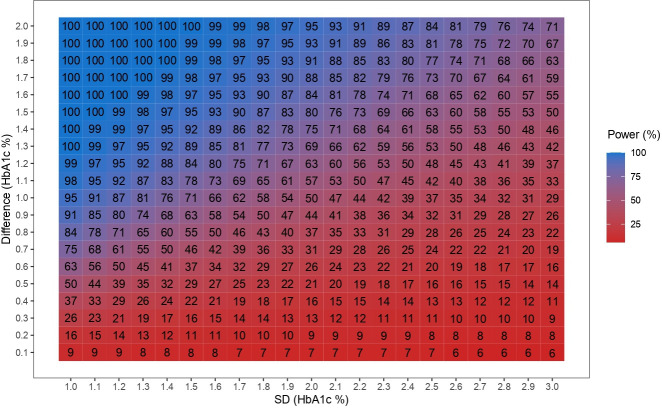

All 50 PLWT1D identified at the two hospitals in Neno will be offered to take part. Figure 1 shows the expected power for examining difference in reduction of HbA1c between arms. Given an expected SD of 1.6 or less we would have 80% power to identify a 1.2% difference in reduction between the treatment arm and the control arm.

Figure 1.

Power table showing expected power for range of changes in HbA1c levels for different SD. HbA1c, haemoglobin A1c.

Data collection

The study is expected to begin recruitment in March 2022. We expect data collection to be completed by June 2022. A T1D research and clinical fellow, who is experienced in CGM care delivery, training and evaluation, will be on site for the training at the initiation of the study. All participants will complete the intake form on enrolment to include information on duration since diagnosis with T1D, marital status and education level. At baseline and endline all participants will complete the WHO Quality of Life questionnaire and a point-of-care test for HbA1c. We will also conduct chart reviews to obtain information about insulin dosage and dose adjustments.

Outcomes

Primary outcomes

Implementation outcomes

Fidelity: Variables that reflect the participants’ adherence to the per protocol utilisation of technology including (1) Per cent of time worn; (2) Per cent of expected blood glucose readings logged; (c) Per cent of participants who brought log book to clinic during study period; (4) Per cent of expected times blood sugar test was performed (based on logbooks, home glucose metres, numbers of strips); (5) Per cent of expected times CGM and SMBG information was used to inform lifestyle adjusted interventions and (6) Number of sensors worn.

Appropriateness: Factors will be assessed from quantitative and qualitative data. The frequency of technology or battery issues will be measured. Additionally, participants will take part in qualitative interviews at baseline and endline discussing the ease of use and benefits and challenges of CGM technology in their setting.

Clinical outcomes

Change in HbA1C: HbA1c in rural Malawi is generally tested via a point-of-care device and requires a lancet-induced drop of capillary blood from the participant’s fingertip. The resulting per cent value reflects the blood glucose level over the past 1–3 months. This will be measured at study enrolment and on conclusion of the study period. While per cent time in range is considered the gold standard in CGM trials, because in this trial we are unsure what proportion of individuals will be able to successfully use their CGM, we are choosing HbA1c as a primary outcome, as we will be able to measure it in all study participants.

Severe adverse events: Potential adverse events include infection, local skin reaction, bleeding, hospitalisation, hypoglycaemia and hyperglycaemia. Data sources will include readings/reports from CGM and home glucose metres, clinician’s reports and self-reports through logbooks and qualitative interviews.

Secondary outcomes

Acceptability: In qualitative interviews at baseline and endline, participants and clinical providers will discuss their satisfaction with content, complexity, comfort and delivery of CGM or SMBG technologies.

Per cent time in range: This value represents the proportion of blood glucose readings observed by the subject which are within the normal range (70–180 mg/dL). This will be measured using uploaded CGM data in the intervention arm.

Average SD in HbA1c: This statistic will determine variability in the SD of HbA1C in order to inform further studies.

Quality of life: WHO Quality of Life surveys will be conducted at the start and conclusion of the study period.

Statistical methods

The analysis will be conducted as an intention to treat. We will also conduct a secondary sensitivity per-protocol analysis. For continuous outcomes including HbA1c, we will use analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) models adjusting for baseline levels and site. For binary outcomes we will conduct logistic regressions adjusting for possible confounders including site. For qualitative outcomes, we will conduct a narrative synthesis using a thematic analysis.

Harms

All participants will be provided an educational session about the project and training on proper disposal of Dexcom sensors and insertion devices. While rates of infection, skin reaction and traumatic bleeding are extremely low, clinical staff will be available by phone and in-person at health facilities for monitoring and appropriate clinical management. Clear protocols warranting medical attention will be provided to participants. Research staff and clinical teams will be well-versed in proper protocols and/or clinical management for any adverse events. Any reported adverse events will be immediately assessed and documented. A monthly report describing all adverse events will be reviewed by research staff, including the principal investigator, and reported to the NCD Unit within the Clinical Services Directorate at the Malawi MOH.

All data will be stored in password-protected files and/or computers in locked research offices and the patient’s CGM receiver. All patients will be trained to keep receivers with them at all times and not share the device with others. Any transfer of data between sites will occur via password protected and encrypted email accounts housed within the participating institutions

Patients and public research involvement

PLWT1D will be engaged throughout the entire study. As the primary outcome of this research is feasibility and acceptability, perspectives, experiences and views of the technology by PLWT1D is core to the entire study. One of the study coauthors (GF) is living with T1D, and will be involved throughout the design of the protocol, tools and implementation of the study.

Ethics and dissemination

The protocol is approved by National Health Sciences Research Committee of Malawi (IRB Number IR800003905) and the Mass General Brigham (IRB number 2019P003554). All participants will be required to provide signed or fingerprinted informed consent to NCD clinic staff prior to enrolment in the study. Findings will be disseminated to PLWT1D through health education sessions. We will disseminate any relevant findings to clinicians and leadership within our study catchment area and networks. We will publish our findings in an open-access peer-reviewed journal. Any deviations from the study protocol will be communicated to investigators and participants, as well as clearly outlined in any publications.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: Study and tool design: AJA, TR, FV, CT, GF, AM, EW, CK, GB and PP. Manuscript drafting: AJA, LD, PP and GB. All authors contributed to the final manuscript. GB and PP shared last authorship

Funding: This work was supported by the Leona M. and Harry B. Helmsley Charitable Trust grant number 2105-04638. Dexcom generously donated CGM Dexcom 6 glucose meters and sensors for the study free of charge

Disclaimer: The funders had no input into the design or conduct of the study.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

References

- 1.World Health Organization . Definition and diagnosis of diabetes mellitus and intermediate hyperglycemia: report of a WHO/IDF consultation, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Atun R, Davies JI, Gale EAM, et al. Diabetes in sub-Saharan Africa: from clinical care to health policy. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 2017;5:622–67. 10.1016/S2213-8587(17)30181-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Beran D, Yudkin JS. Diabetes care in sub-Saharan Africa. Lancet 2006;368:1689–95. 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69704-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chan JCN, Lim L-L, Wareham NJ, et al. The Lancet Commission on diabetes: using data to transform diabetes care and patient lives. Lancet 2021;396:2019–82. 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)32374-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ogle GD, von Oettingen JE, Middlehurst AC, et al. Levels of type 1 diabetes care in children and adolescents for countries at varying resource levels. Pediatr Diabetes 2019;20:93–8. 10.1111/pedi.12801 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ogle GD, Middlehurst AC, Silink M. The IDF life for a child program index of diabetes care for children and youth. Pediatr Diabetes 2016;17:374–84. 10.1111/pedi.12296 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Klatman EL, Ogle GD. Access to insulin delivery devices and glycated haemoglobin in lower-income countries. World J Diabetes 2020;11:358–69. 10.4239/wjd.v11.i8.358 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.World Health Organization Regional Office for Africa . WHO PEN and integrated outpatient care for severe, chronic NCDs at first referral hospitals in the African Region (PEN-Plus) - Report on regional consultation, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Beck RW, Riddlesworth T, Reudy K. Glucose monitoring and glycemic control via insulin injections: the diamond randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2017;317:371–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Danne T, Nimri R, Battelino T, et al. International consensus on use of continuous glucose monitoring. Diabetes Care 2017;40:1631–40. 10.2337/dc17-1600 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Langendam M, Luijf YM, Hooft L, et al. Continuous glucose monitoring systems for type 1 diabetes mellitus. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2012;1:CD008101. 10.1002/14651858.CD008101.pub2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Paramasivam SS, Chinna K, Singh AKK, et al. Continuous glucose monitoring results in lower HbA1c in Malaysian women with insulin-treated gestational diabetes: a randomized controlled trial. Diabet Med 2018;35:1118–29. 10.1111/dme.13649 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McClure Yauch L, Velazquez E, Piloya‐Were T, et al. Continuous glucose monitoring assessment of metabolic control in East African children and young adults with type 1 diabetes: a pilot and feasibility study. Endocrinol Diab Metab 2020;3. 10.1002/edm2.135 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ruderman T, Ferrari G, Valeta F. Implementation of self-monitoring of blood glucose for insulin dependent diabetes patients in a rural non-communicable disease clinic in Neno, Malawi. Ann Afr Med. Under review. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Phelan H, Lange K, Cengiz E, et al. ISPAD clinical practice consensus guidelines 2018: diabetes education in children and adolescents. Pediatr Diabetes 2018;19 Suppl 27:75–83. 10.1111/pedi.12762 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2021-052134supp001.pdf (109.6KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2021-052134supp002.pdf (92.5KB, pdf)