To the Editor:

Critical care clinicians experienced high rates of burnout and depression early in the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic (1–3). We sought to longitudinally evaluate burnout, depression, and professional fulfillment—as measures of overall clinician wellness—among critical care healthcare professionals at seven hospitals within our hospital network. We hypothesized that well-being and depression would initially worsen over time but would improve with the arrival of the vaccine and that burnout rates would be higher among nonphysicians with less professional time dedicated to nonclinical activities such as education and research, which may allow time for renewal.

Methods

We administered a questionnaire quarterly to attending physicians, advanced practice providers (APPs) (including nurse practitioners and physician assistants), respiratory therapists (RTs), and clinical pharmacists who staffed intensive care units (ICUs) of seven hospitals at Penn Medicine. Nurses did not participate because of concurrent research studies and leadership concern about survey fatigue. As detailed elsewhere, our integrated academic medical center leveraged the health system Critical Care Alliance to create the COVID-19 Task Force, which served to develop and disseminate standardized clinical protocols, educate critical care clinicians, and monitor and optimize outcomes (4, 5).

We invited participants by e-mail in July of 2020, October of 2020, and January of 2021 to complete the questionnaire electronically via the Research Electronic Data Capture platform (the questionnaire is available from corresponding author upon request) (6). The questionnaire included the 7-item Well-Being Index (WBI) (7) and the 16-item Stanford Professional Fulfillment Index (SPFI) (8). As in previous studies, we defined burnout as an SPFI average burnout score of ⩾1.33 or a WBI score of ⩾4 and fulfillment as an SPFI fulfillment score of ⩾3 (2). We defined depression as a response of “yes” to the single WBI question about depression symptoms.

To test our hypotheses, we built three separate mixed-effect logistic regression models with dependent variables of burnout, depression, and professional fulfillment. Each model included a random effect for participant to account for multiple responses by individuals over time. We a priori selected female sex and years of experience to include as potential confounders on the basis of previous literature (9, 10). We used a P value of 0.05 as the threshold for statistical significance and used Stata 16.1 (StataCorp) for all statistical analyses. This study was approved by the University of Pennsylvania Institutional Review Board.

Results

Of 550 clinicians invited, 296 (54%) responded to at least one survey, including 73 attending physicians, 105 APPs, 18 pharmacists, and 100 RTs. Of the 296 participants, 171 (58%) were female, with a median number of years in clinical practice of 7 (interquartile range, 3–15). One hundred thirty-seven (46%) participants completed one survey, 88 (30%) completed two surveys, and 71 (24%) completed three surveys. The proportion of clinicians who completed the survey over time, by professional role, did not change significantly (P = 0.61).

Among all participants, 198 (67%) reported burnout symptoms in response to at least one quarterly survey, 136 (46%) reported depression symptoms, and 126 (43%) experienced professional fulfillment. By professional role, 41 (56%) physicians, 71 (68%) APPs, 12 (67%) pharmacists, and 74 (74%) RTs reported burnout symptoms at least once. Twenty-two (30%) physicians, 45 (47%) APPs, 10 (56%) pharmacists, and 57 (57%) RTs reported having symptoms of depression. And 41 (56%) physicians, 42 (40%) APPs, 7 (39%) pharmacists, and 36 (36%) RTs experienced professional fulfillment. As shown in Table 1, rates of burnout differed across hospitals. In general, burnout increased over time across hospitals and was the highest in hospitals with the greatest burden of critically ill patients with COVID-19.

Table 1.

Cumulative COVID-19 ICU census as of February 9, 2021, and burnout, by hospital

| Cumulative COVID-19 ICU Census | Burnout (%) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quarter 1 | Quarter 2 | Quarter 3 | ||

| Hospital A | 580 | 69 | 56 | 78 |

| Hospital B | 528 | 54 | 66 | 67 |

| Hospital C | 489 | 56 | 62 | 59 |

| Hospital D | 310 | 7 | 25 | 30 |

| Hospital E | 271 | 59 | 71 | 66 |

| Hospital F | 203 | 66 | Unavailable | 50 |

| Hospital G | Unavailable | 57 | 83 | 50 |

Definition of abbreviations: COVID-19 = coronavirus disease; ICU = intensive care unit.

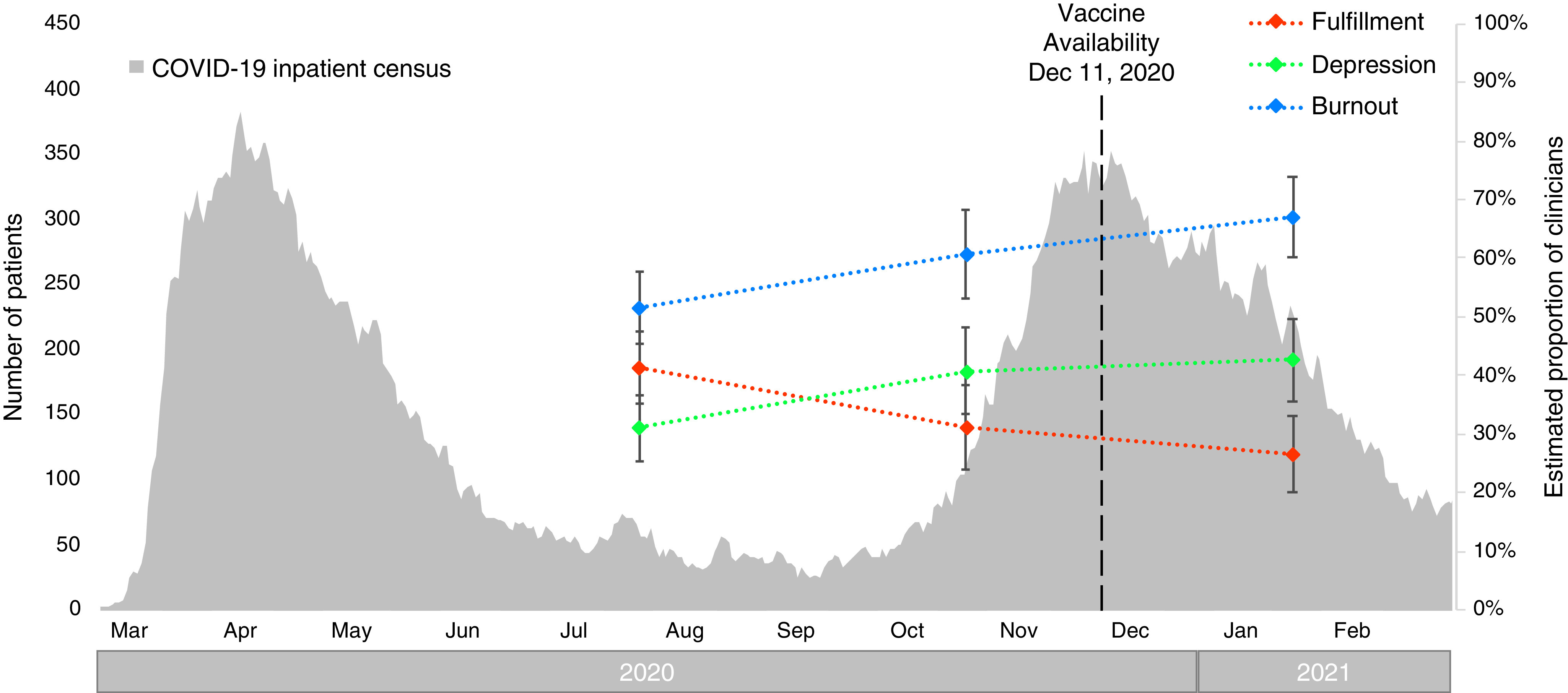

In multivariable analyses, burnout and depression significantly increased and professional fulfillment significantly decreased in the second and third quarterly surveys, compared with the first. Figure 1 illustrates predicted estimates of proportions of all clinicians experiencing burnout, depression, and fulfillment over time, accounting for differences in sex and years in practice. When using attending physicians as the reference group, burnout and depression were significantly worse and professional fulfillment were significantly lower among RTs, but not among other groups (Table 2). Among the 71 clinicians who completed all surveys, burnout increased from 56% to 60–71% over the three surveys, and depression increased from 29% at the first survey to 40% in the latter two surveys.

Figure 1.

Adjusted estimates of wellness measures during the pandemic. The dashed lines represent the predicted proportion of clinicians with burnout (blue), depression (green), and fulfillment (orange), which were estimated from multivariable models to account for differences in sex and years in practice. The gray bars indicate the inpatient census of confirmed COVID-19 cases across all University of Pennsylvania Health System hospitals over time. COVID-19 = coronavirus disease.

Table 2.

Multivariable analyses of wellness measures

| Variable | Burnout |

Depression |

Fulfillment |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | P Value | OR (95% CI) | P Value | OR (95% CI) | P Value | |

| Professional role | ||||||

| Attending physician | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| APP | 0.64 (0.21–1.97) | 0.43 | 1.06 (0.29–3.85) | 0.93 | 0.92 (0.31–2.70) | 0.88 |

| Clinical pharmacist | 0.79 (0.14–4.52) | 0.79 | 2.05 (0.28–14.8) | 0.48 | 0.53 (0.09–3.07) | 0.48 |

| Respiratory therapist | 3.70 (1.21–11.3) | 0.02 | 8.13 (2.17–30.5) | 0.002 | 0.28 (0.10–0.82) | 0.02 |

| Survey quarter | ||||||

| Quarter 1 | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| Quarter 2 | 2.04 (1.05–3.98) | 0.04 | 2.45 (1.18–5.09) | 0.02 | 0.45 (0.23–0.88) | 0.02 |

| Quarter 3 | 3.50 (1.75–7.02) | <0.001 | 2.87 (1.40–5.87) | 0.004 | 0.30 (0.15–0.59) | 0.001 |

Definition of abbreviations: APP = advanced practice provider; CI = confidence interval; OR = odds ratio.

Analyses included 509 responses that had complete data for potential confounders.

Discussion

In this longitudinal evaluation of critical care healthcare professional wellness during the pandemic, we found that symptoms of burnout and depression have increased and that fulfillment has decreased during the course of the pandemic. Furthermore, wellness is particularly low among RTs, who have the highest rates of burnout and depression and the lowest rates of fulfillment. Contrary to our hypothesis, there was no noticeable improvement after the start of vaccination efforts.

There are several possible explanations for the findings that wellness overall has worsened over time among all groups. All critical care professionals have likely experienced an excessive workload and may have clinical schedules that do not permit time for renewal. There have been changes in practices during the pandemic, such as increased death and suffering witnessed, challenges to shared decision-making and family communication related to restrictive visitation policies, and the loss of community at work. The vaccination efforts were slow and uncertain at the start, and COVID-19 activity remained high, so the impact of the vaccine may not have yet altered clinicians’ perceptions of the outlook for the pandemic or mitigated the existing burnout and fatigue from the preceding months. Alternatively, the vaccination efforts may have mitigated what would have been even worse burnout.

That burnout was worst among RTs bears noting. RTs may perceive even higher personal risk, as they are directly responsible for administering aerosol-generating treatments to patients with COVID-19 with respiratory compromise. Furthermore, in many places, including our institution, RTs faced staffing challenges during the pandemic that resulted in an increased workload, exposing them to greater risk and a greater volume of patients, many of whom did not survive. Future studies should target RTs to better understand and intervene regarding these findings to maintain this essential component of the critical care workforce.

Our study has a few important limitations. It was conducted within a single health system, which may limit generalizability; however, we included seven hospitals that are organizationally distinct and serve different patient populations. Second, we could not survey nurses, vital members of the interdisciplinary critical care team. Third, our well-being measures, although validated and recommended (11), rely on self-report. Finally, our response rate, although modest and lower than that of Azoulay and colleagues (1), was higher than the 45% response rate of our prepandemic survey (2) and was substantially higher than the 20% response rate reported in a recent survey conducted during the pandemic (12).

In summary, this study confirms earlier reports that revealed the impact of the pandemic on critical care healthcare professional well-being (1–3, 12) and reveals that wellness among this group has declined further during the pandemic, with RTs faring the worst among all groups studied. Although future studies are needed to examine the impact of the pandemic on the critical care workforce and their long-term mental health, these data serve as an urgent call to action for healthcare organizations to tend to the well-being of the critical care workforce.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgment

The authors thank Dr. Lisa Bellini for her support and advice in the conduct of this study. We thank Greg Kruse for his work to create the daily health system COVID-19 report, which is incorporated into our exhibits.

Footnotes

Supported by the Clifton Fund of the Perelman School of Medicine, the University of Pennsylvania (M.P.K., J.A.S., T.K., and M.E.M.).

Author Contributions: M.P.K., J.A.S., T.K., J.T.G., J.J., and M.E.M. contributed to the conception and design of the study. M.P.K. and M.E.M. conducted and take responsibility for all data analyses. All authors contributed to the writing and revising of the manuscript.

Author disclosures are available with the text of this letter at www.atsjournals.org.

References

- 1. Azoulay E, Cariou A, Bruneel F, Demoule A, Kouatchet A, Reuter D, et al. Symptoms of anxiety, depression, and peritraumatic dissociation in critical care clinicians managing patients with COVID-19: a cross-sectional study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med . 2020;202:1388–1398. doi: 10.1164/rccm.202006-2568OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Gomez S, Anderson BJ, Yu H, Gutsche J, Jablonski J, Martin N, et al. Benchmarking critical care well-being: before and after the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic. Crit Care Explor . 2020;2:e0233. doi: 10.1097/CCE.0000000000000233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Kok N, van Gurp J, Teerenstra S, van der Hoeven H, Fuchs M, Hoedemaekers C, et al. Coronavirus disease 2019 immediately increases burnout symptoms in ICU professionals: a longitudinal cohort study. Crit Care Med . 2021;49:419–427. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000004865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Anesi GL, Jablonski J, Harhay MO, Atkins JH, Bajaj J, Baston C, et al. Characteristics, outcomes, and trends of patients with COVID-19-related critical illness at a learning health system in the United States. Ann Intern Med . 2021;174:613–621. doi: 10.7326/M20-5327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ginestra JC, Atkins J, Mikkelsen M, Mitchell OJL, Gutsche J, Jablonski J, et al. The I-READI quality and safety framework: a health system’s response to airway complications in mechanically ventilated patients with COVID-19. NEJM Catal Innov Care Deliv . 2021;2:1–19. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG.Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap): a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support J Biomed Inform 200942377–381.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Dyrbye LN, Satele D, Sloan J, Shanafelt TD. Utility of a brief screening tool to identify physicians in distress. J Gen Intern Med . 2013;28:421–427. doi: 10.1007/s11606-012-2252-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Trockel M, Bohman B, Lesure E, Hamidi MS, Welle D, Roberts L, et al. A brief instrument to assess both burnout and professional fulfillment in physicians: reliability and validity, including correlation with self-reported medical errors, in a sample of resident and practicing physicians. Acad Psychiatry . 2018;42:11–24. doi: 10.1007/s40596-017-0849-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Poncet MC, Toullic P, Papazian L, Kentish-Barnes N, Timsit JF, Pochard F, et al. Burnout syndrome in critical care nursing staff. Am J Respir Crit Care Med . 2007;175:698–704. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200606-806OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Embriaco N, Azoulay E, Barrau K, Kentish N, Pochard F, Loundou A, et al. High level of burnout in intensivists: prevalence and associated factors. Am J Respir Crit Care Med . 2007;175:686–692. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200608-1184OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.National Academy of Medicine Action Collaborative on Clinician Well-Being and Resilience. Valid and reliable survey instruments to measure burnout, well-being, and other work-related dimensions Washington, DC: National Academy of Medicine; 2021. [accessed 2021 Mar 25]. Available from: https://nam.edu/valid-reliable-survey-instruments-measure-burnout-well-work-related-dimensions/ [Google Scholar]

- 12.Azoulay E, De Waele J, Ferrer R, Staudinger T, Borkowska M, Povoa P, et al. ESICM Symptoms of burnout in intensive care unit specialists facing the COVID-19 outbreak Ann Intensive Care 202010110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]