Abstract

Though frequently associated with tumor progression, inflammatory cytokines initially restrain transformation by inducing senescence, a key tumor-suppressive barrier. Here, we demonstrate that the inflammatory cytokine Oncostatin M (OSM) activates a mesenchymal/stem cell (SC) program that engages cytokine-induced senescence (CIS) in normal human epithelial cells. CIS is driven by Snail induction and requires cooperation between STAT3 and the TGF-β effector SMAD3. Importantly, as cells escape CIS, they retain the mesenchymal/SC program and are thereby bestowed with a set of cancer SC (CSC) traits. Of therapeutic importance, cells that escape CIS can be induced back into senescence by CDK4/6 inhibition, confirming that the mechanisms allowing cells to escape senescence are targetable and reversible. Moreover, by combining CDK4/6 inhibition with a senolytic therapy, mesenchymal/CSC can be efficiently killed. Our studies provide insight into how the CIS barriers that prevent tumorigenesis can be exploited as potential therapies for highly aggressive cancers.

INTRODUCTION

Inflammatory cytokines in the tumor microenvironment (TME) regulate cancer cell proliferation, epithelial-mesenchymal plasticity, and cancer stem cell (CSC) phenotypes which drive metastasis and therapy failure, two aggressive features responsible nearly all cancer-related deaths.1 Though immune cell infiltration and inflammation are most often discussed in the context of tumor progression, they also occur in normal tissues to help restrain malignant transformation by inducing and maintaining a key tumor-suppressive senescence barrier.1, 2 A wide range of stalled, premalignant human lesions harbor elevated numbers of immune cells and stain positive for senescence, including melanocytic nevi,3 colon and lung adenomas,3–5 prostatic intraepithelial and pancreatic intraductal neoplasms,6 mammary atypical ductal hyperplasias and carcinoma in situ,3 and ovarian neoplasms.7

Mutations in oncogenes such as B-RAF or N-RAS can drive the initial expansion of premalignant lesions.8 After limited expansion, proliferation is countered by oncogene-induced senescence (OIS) and the secretion of a collection of soluble factors, termed the senescence-associated secretory phenotype (SASP).9 SASP-factors can recruit immune cells and activate an immune response that helps maintain premalignant cells in a senescent, dormant state.9–11 Unfortunately, a subset of the senescent, premalignant population can escape senescence and continue the transformation process, ultimately emerging as proliferative cancer cells that fuel tumor expansion.8 Determining how would-be cancer cells undermine the intrinsic and extrinsic factors that induce and maintain senescence is critical to understanding the biology underlying tumorigenesis, and may provide new therapeutic avenues that reengage these dismantled suppressive pathways.

Elevated levels of Oncostatin M (OSM), an Interleukin-6 (IL-6) family cytokine, coincide with increased immune cell infiltration in early-stage benign breast, prostate, melanocytic, and ovarian lesions, where senescent cells commonly reside.7, 12–14 OSM-induced senescence in non-transformed epithelial cells is mediated by STAT3 and the TGF-β effector SMAD3, which cooperate to repress c-MYC expression.15, 16 Yet, whereas OSM engages senescence in premalignant cells, it promotes EMT and CSC-associated properties in cells harboring dysregulated c-MYC expression, resulting in invasion and metastasis.17 These findings are consistent with studies showing that elevated OSM levels in the breast TME correlates with increased tumor-recurrence and poor prognosis.15 Recently, cancer cells escaping chemotherapy-induced senescence were shown to acquire stem cell (SC)-properties, ultimately leading to therapy failure.18 Whether non-transformed cells escape from senescence to acquire more stem-like properties as they continue through the transformation process remains unclear.

Here, we find that the activation of an aberrant EMT by OSM precedes senescence in normal human mammary epithelial cells (HMEC). Cooperative STAT3/SMAD3 activity rapidly induces the EMT transcription factor (EMT-TF) Snail, which induces a mesenchymal/SC program coincident with the loss of proliferation and the gain of senescence markers. Notably, aberrant expression of single EMT-TFs was also sufficient to induce senescence, which again was concomitant with and underlies the mesenchymal/SC-associated phenotype. Thus, while a senescent phenotype predominates in non-transformed epithelial cells exposed to inflammatory cytokines, an underlying mesenchymal/SC-like program appears to initiate senescence. Importantly, inducible expression of c-MYC in senescent cells results in the emergence of transformed cells that maintain the underlying mesenchymal/SC program. Cells that have not undergone senescence fail to become transformed or acquire the mesenchymal/SC program. The mesenchymal/CSC that have escaped senescence are more highly sensitive to CDK4/6 inhibition, which selectively reengages senescence, making cells sensitive to senolytic therapies. Our studies highlight the importance of understanding senescence-induced stemness and provide insight into how aggressive mesenchymal/CSC can be potentially targeted.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell culture conditions and reagents.

Non-immortalized, finite lifespan pre-stasis HMEC from specimen 48R, batch T (48RT-HMEC) were obtained from discarded surgical material under IRB approval (provided by Dr. Martha Stampfer; Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory). Non-immortalized primary 48RT-HMEC and their derivatives were examined between passage 10 and passage 30; and were cultured in M87 media in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2 at 37°C as described previously.19 Phoenix–Ampho (ATCC Cat# CRL-3213, RRID:CVCL_H716) and HEK 293T (ATCC Cat# CRL-3216, RRID:CVCL_0063) were grown in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2 in DMEM media (Corning, cat. # 10013CV) supplemented with 5% and 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Atlanta Biologicals, cat. # S10350), respectively. MDA-MB-231 (ATCC Cat# CRM-HTB-26, RRID:CVCL_0062), HCC1187 (ATCC Cat# CRL-2322, RRID:CVCL_1247), HCC1937 (ATCC Cat# CRL-2336, RRID:CVCL_0290), Hs578T (ATCC Cat# HTB-126, RRID:CVCL_0332), and BT-474 (ATCC Cat# HTB-20, RRID:CVCL_0179) breast cancer cell lines were purchased from ATCC on January 5, 2010 and grown at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2. MDA-MB-231, HCC1187, and HCC1937 were cultured in RPMI-1640 medium (Hyclone, cat. # SH30027.02) supplemented with 10% FBS; Hs578T and BT-474 were cultured in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS. Cells purchased from ATCC were utilized within one year and were not independently authenticated. All cancer cell lines were used after thawing for up to fifteen passages; and all cell lines were tested for Mycoplasma, Acholeplasma, Entomoplasma, and Spiroplasma on a monthly basis using the MycoAlert Plus Mycoplasma Detection Kit (Lonza catalog # LT07–710) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Cell lines were last tested for contamination on August 3, 2020. Cells were treated with recombinant human OSM (DAPCEL, cat. # OSM10–13) at 10 ng/mL, Doxycycline hydrochloride (Sigma, cat. # D-9891) at .5 μg/mL, Palbociclib/PD-0332991 HCl (Selleck Chemical, cat. # S1116) at .25 μM, and Navitoclax/ABT-263 (Selleck Chemical, cat. # S1001) at .5 μM unless otherwise indicated. Short-term treatments were directly added to culture medium after serum-starving cells for 24 hours in basal medium. For long-term experiments, treatments were given with fresh medium every 48 hours until cells were analyzed.

Viral vectors and infection.

The retroviral vector pMSCV-sin Hygro shp16 was provided by Dr. Scott Lowe (Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, Cold Spring Harbor, NY); and the retroviral plasmids pLNCX2 MYC-IRES-GFP (MYC) and pLNCX2 MYC-IRES-H-RAS V12 (MiR) are described elsewhere.15, 16, 20 The retroviral plasmids pRetroSUPER-Puro shSMAD2 and pRetroSUPER-Puro shSMAD3 (Addgene plasmid #s 15722 and 15726) were gifts from and deposited to Addgene by Dr. Joan Massague (Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center); and pRetroSUPER-Puro shGFP was obtained from Dr. Yosef Shiloh (Department of Neurobiology, Tel Aviv University, Tel Aviv, Israel). For lentiviral vectors, pLV-shp53-bleo encoding short-hairpin-RNA targeting p53 (shp53) was described previously20; and pLenti CMV rtTA3 Blast (w756–1) (plasmid # 26429), pLenti CMV H-RasV12 Neo (w108–1) (plasmid # 22259), and pLenti CMVTRE3G eGFP-Neo (w821–1) (plasmid # 27569) were obtained from Addgene and were gifts from Eric Campeau. Other lentiviral vectors also obtained from Addgene were gifts from Eric Campeau and Paul Kaufman, including pLenti CMV-Neo GFP (657–2) (plasmid # 17447), pLenti CMV-Puro GFP (658–5) (plasmid # 17448), pENTR4 no ccDB (686–1) (plasmid # 17424), pLenti CMV-Puro DEST (w118–1) (plasmid # 17452), pLenti CMV-Neo DEST (705–1) (plasmid # 17392), and pLenti CMV/TO Neo DEST (685–3) (plasmid # 17292). Additional lentiviral expression vectors were generated using Gateway Technology (Invitrogen) for cDNA cloning into entry vectors and then recombination into specific Gateway destination expression vectors using a Gateway LR Clonase II Enzyme Mix (Invitrogen, cat. #11791–100). pLenti CMV-Puro Vec (empty) was generated by recombining the multiple cloning site of the pCR8/GW/TOPO entry vector (Invitrogen; cat. # 46–0899) into the pLenti CMV-Puro DEST (w118–1) Gateway destination vector. pLenti CMV-Puro OSM and pLenti CMV-Neo OSM were generated by recombining Human OSM (NM_020530) cDNA in the pENTR221 Gateway entry vector (Geneopeia; cat. # HOC12948) into pLenti CMV-Puro DEST (w118–1) and pLenti CMV-Neo DEST (705–1) Gateway destination vectors, respectively, and then sequence-verified. pLenti CMV-Puro TWIST1 was created by recombining Human TWIST1 (NM_000474.3) cDNA from the Gateway PLUS pShuttle entry vector (Geneopeia; cat. # GC-U1219) into pLenti CMV-Puro DEST (w118–1), and then sequence-verified. cDNA subcloned from other vectors or amplified by PCR were cloned into the MCS of the pCR8/GW/TOPO Gateway entry vector using a pCR8/GW/TOPO-TA Cloning Kit (Invitrogen, cat. # K2500–20) and then sequenced verified. Human Snail (NM_005985.3) cDNA was subcloned from pBabe-Puro Snail (Addgene Plasmid # 23347), a kind gift from Bob Weinberg, using BamHI-HF (NEB Catalog # R3136S) and EcoRI-HF (NEB Catalog # R3101S). Human Zeb1 (NM_030751.4) cDNA was amplified by PCR from pLuc-CDS (ZEB1) (Addgene Plasmid # 42100) using the primers ZEB1 Forward 5’-GGATCCGCCGCCACCATGGCGGATGGCCCCAG-3’ and ZEB1 Reverse 5’-CGAATTCTTAGGCTTCATTTGTCTTTTCTTC-3’, which introduced BamHI and EcoRI restriction enzyme recognition sites at the ends of the sequence. Human Snail cDNA and the Human Zeb1 PCR fragment were both subcloned into the pCR8/GW/TOPO entry vector using BamHI-HF and EcoRI-HF. Human CD44 (NM_000610.3) and Human HAS2 (NM_ 005328.2) cDNA were amplified by PCR using mRNA isolated from OSM-treated SKD-HMEC and the primer sets CD44s Forward 5’-GCCGCCACCATGGACAAGTTTTGGTGGCACG-3’ and CD44s Reverse 5’-GTGTTACACCCCAATCTTCATGTCCACATTCTGC-3’, and HAS2 Forward 5’- GCCGCCACCATGCATTGTGAGAGGTTTCTATG-3’ and HAS2 Reverse 5’- GGATCATACATCAAGCACCATGTC −3’; which introduced EcoRI restriction enzyme recognition sites on both ends of the cDNA sequences. Both Human CD44 and Human HAS2 PCR fragments were then subcloned into the pCR8/GW/TOPO entry vector using EcoRI-HF. The pCR8-Snail, pCR8- Zeb1, pCR8- CD44s, and pCR8- HAS2 Gateway entry vectors were then each recombined with pLenti CMV-Puro DEST (w118–1) using the LR Clonase II Enzyme Mix described above to generate pLenti CMV-Puro Snail, pLenti CMV-Puro Zeb1, pLenti CMV-Puro CD44s, and pLenti CMV-Puro HAS2, respectively. Human c-MYC cDNA was subcloned from pLNCX2 MiG into the pENTR4 Gateway entry vector using EcoRI-HF and SalI-HF (NEB, cat. # R3138S), and then recombined into the Gateway destination vectors pLenti CMV-Puro DEST (w118–1), pLenti CMV-Neo DEST (705–1), and pLenti CMV/TO-Neo DEST (685–3) to create pLenti CMV-Puro c-MYC, pLenti CMV-Neo c-MYC, and doxycycline-inducible pLenti CMV/TO-Neo c-MYC expression vector. Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen, cat. # 11668019) was used in transfections for virus production. Retroviruses were created by transfecting Phoenix–Ampho cells with retroviral vectors and a packaging plasmid encoding the MLV-gag-pol and env genes; and Lentiviruses were produced by transfecting lentiviral vectors in HEK 293T cells simultaneously with the second-generation packaging constructs pCMV-dR8.74 and pMD2G, kind gifts from Dr. Didier Trono (University of Geneva, Switzerland) as previously described.20 Supernatant M87 media containing viruses was collected 24–48 hours post-transfection, filtered using a 0.22 mm filter, and supplemented with 4 μg/mL polybrene (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, cat. # sc-134220) prior to concentration titering, freezing aliquots of lentiviruses; and before being used to infect cells for 24–48 hours in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2 at 37°C. Uninfected cells were removed with the appropriate antibiotic selection reagents: G418 [200 μg/mL] (Sigma, cat. # 4727878001), puromycin [1 μg/mL] (Sigma, cat. # P8833), hygromycin (200 μg/mL] (Sigma, cat. # H3274), blasticidin [10 μg/ml] (Sigma, cat. # 203350), or zeocin [200 μg/mL] (Invitrogen, cat. # R25001).

Proliferation assays and population doubling (PD) calculation.

Relative growth assays were performed by seeding 2.5 × 104 cells per well in triplicate in six-well plates. Cells were grown in the presence or absence of treatment for 10 days unless otherwise noted, and total cell number was quantified using a Beckman Coulter counter. Results are presented as the mean ± SEM for each triplicate. Population Doubling (PD) assays were conducted by seeding 2 × 104 cells in triplicate in six-well plates and passaging cell cultures when they reach 80% confluency. Cell number was quantified at each passage for all triplicates, and then cells were seeded into new six-well plates and grown as before. The number of PD at each passage was calculated using the formula: PD = log (cells counted/cells plated)/log2. The PD at each point cells were passaged represents the mean of all triplicates counted.

Senescence, apoptosis, and cell viability analyses.

Senescence was assessed by qRT-PCR analysis of MYC, GLB1, CDKN2D, and IL-6 expression, as well as by detecting senescence-associated β-galactosidase (SA-β-Gal) activity for cells cultured in 6-well plates using a SA-β-Galactosidase Staining Kit (Cell Signaling, cat. # 9860) and performing the standard protocol according to the manufacturer’s instructions. SA-β-Gal+ cells were identified by blue-staining using brightfield microscopy and quantified using a minimum of 3 fields from 3 independent biological replicates within one experiment in order to more accurately represent the entire population. The number of blue-stained cells counted were divided by the total number of cells in each well. A minimum of 375 cells per well was counted. Each condition was performed in triplicate and the percent of SA-β-Gal-positive cells was calculated as the average number for all three wells. SA-β-gal enzymatic activity was also assessed by flow cytometry using a CellEvent Senescence Green Flow Cytometry Assay Kit (Invitrogen; Catalog number C10840) according to the manufacturer’s instructions and a modified protocol to multiplex the assay with antibodies against the cell surface markers. Specifically, cells were trypsinized and counted, then 1 × 106 cells were washed and resuspended in 100 μL 2% BSA in PBS. Cell surface antigens (CD24 and CD44) were stained by adding and incubating cells with antibodies as described in the “Flow cytometry analysis and fluorescence activated cell sorting (FACS)” section below. After surface antigen staining, cells were washed with 2% BSA in PBS and fixed in 100 μL of 3% paraformaldehyde in PBS for 10 minutes at room temperature in the dark. Fixative solution was removed by washing cells in 3 mL of 2% BSA in PBS, then cells were probed with 1.0 μM CellEvent Senescence Green fluorescent substrate as described by the manufacturer and assessed by flow cytometry using a 488 nm laser and 530/30 nm filter. Percentages of SA-β-Gal−, SA-β-Gal+/LO, SA-β-Gal+/HI cells were quantified according to the median fluorescence intensity of CellEvent Senescence Green staining in probed cells compared to negative control, unstained non-senescent cells. As a secondary method to assess β-Galactosidase activity by flow cytometry, lysosomal alkalinization was accomplished by washing cells and incubating at 37°C, 5% CO2 for 2 hours with 100 nM of bafilomycin A1 (Sigma, cat. # B1793) in complete culture medium. Cells were then probed with the fluorescent β-galactosidase substrate, C12FDG, at 37°C, 5% CO2 using a ImaGene Green C12FDG lacZ Expression Kit (Invitrogen, cat. # I2904) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Unlabeled and C12FDG-labeled cells were then assessed by flow cytometry and subjected to FACS as previously described21. BrdU incorporation assays were conducted with the BD Pharmingen FITC-BrdU Flow Kit (BD Biosciences, cat. # 559619). 10 μM BrdU was added to cell cultures for 2 hours at 37°C, 5% CO2. BrdU-pulsed cells were trypsinized and counted, then 1 × 106 cells were stained 1 hour on ice with antibodies specific for cell surface antigens (anti-CD24-PE and anti-CD44-APC). Cells were then fixed, permeabilized, stained with anti-BrdU-fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC), and assessed by flow cytometry according to the manufacturer’s standard protocol. BrdU+ cells were quantified according to the median fluorescence intensity of BrdU-FITC staining relative to unstained negative control cells. For apoptosis analysis using flow cytometry, 5 × 105 cells were seeded in 60-mm dishes and treated for an additional 48 hours in culture with 1 μM palbociclib, accordingly, then treated with .5 μM navitoclax for 24 hours. Treated cells were trypsinized and counted, then Annexin V/propidium iodide (PI) staining assays were performed using 5 × 105 cells and an eBioscience Annexin V-FITC Apoptosis Detection Kit (Invitrogen; Catalog number 88–8005-74) according to the manufacturers’ instructions. Cells stained with FITC-labeled Annexin V and propidium iodide (PI) were then examined by flow cytometry. Viable cells (Annexin V-/PI-; Gate III), early-stage apoptotic cells (Annexin V+/PI-; Gate IV), late-stage apoptotic and necrotic cells (Annexin V+/PI+; Gate II), and Annexin V-/PI- cells (Gate I) were then identified and percentages quantified.

Western blot analysis.

Western blotting analysis was performed with whole-cell protein extracts and enhanced chemiluminescence as described previously.16 Immunoblotting of membranes was conducted with primary antibodies and dilutions indicated in Supplementary Table 1. Primary antibodies were detected with secondary antibodies from Cell Signaling Technology that were horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG (cat. # 7076, RRID:AB_330924) and goat anti-rabbit IgG (cat. # 7074, RRID:AB_2099233), both used at a 1:5,000 dilution.

RNA isolation and quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) analysis.

Total messenger ribonucleic acid (mRNA) isolation, cDNA synthesis using 1 μg total mRNA, and qRT-PCR analysis was conducted as previously described16, 17 at a 60° C annealing temperature using iQ SYBR Green Supermix (Bio-Rad, cat. # 170–8882) and primers listed in Supplementary Table 2. qRT-PCR was performed in technical triplicates and samples were normalized to ACTB expression. Data represent the mean ± SEM (error bars) of technical triplicates for one experiment. Pathway expression analysis was performed with the RT2 Profiler qRT-PCR Array Systems for Human Cellular Senescence (Qiagen, cat. # 330231 PAHS-050ZA) and Human Epithelial to Mesenchymal Transition (Qiagen, cat. # 330231 PAHS-090ZA). For each profiler array, total mRNA (2.5 μg) was reverse transcribed into cDNA with the RT2 First Strand cDNA synthesis Kit (Qiagen, cat. # 330401), and qRT-PCR was performed using RT2 SYBR Green qPCR Mastermix (Qiagen, cat. # 330500) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Raw threshold cycle (CT) data was analyzed using the RT2 Profiler PCR Array Data Analysis Webportal with the GeneGlobe Data Analysis Center (Qiagen). CT values were normalized based on manual selection of reference genes, with the Human Cellular Senescence profiler array normalized to an average of housekeeping genes (HKG) and the Human Epithelial to Mesenchymal Transition profiler array normalized to HPRT1.

Flow cytometry analysis and fluorescence activated cell sorting (FACS).

Flow cytometry was performed with 1 × 106 cells per sample as previously described19 using anti-CD24-phycoerythrin (PE) (Clone ML5; BioLegend, cat. # 311106) and anti-CD44-allophycocyanin (APC) (Clone BJ18; BioLegend, cat. # 338806). Flow cytometry analysis was performed on a BD LSRII using FACSDiva software version 6.2 (BD FACSDiva Software, RRID:SCR_001456, Becton Dickinson) and Fluorescent activated cell sorting (FACS) was conducted on a BD Biosciences FACS ARIA II as described17.

Microscopy and immunofluorescence (IF).

Brightfield images were obtained with oblique illumination and a 10X PlanFluor_DL 0.30/15.20mm Ph1 objective using a Keyence BZ-X810 microscope and BZ-X Analyzer software. 25 fields were captured from biological triplicates for each treatment, with one representative image per sample presented in figures. Phase contrast images were captured at 10X magnification using a Leica DMI6000 microscope and MetaMorph software (Molecular Devices). Confocal immunofluorescence analysis was conducted as previously described16, 19 using 1 μg/mL Diaminophenylindole (DAPI) (Sigma-Aldrich, cat. # D9542) to stain nuclei and the Alexafluor-conjugated primary antibodies and dilutions indicated in Supplementary Table 1. Confocal microscopy mages were captured using AIM software (Leica) with a Zeiss LSM 510 multiphoton microscope and 63X oil immersion objective.

Doxycycline-inducible c-MYC expression system and senescence-escape assays.

For doxycycline-inducible expression experiments and senescence-escape assays, M87 HMEC medium was created using tetracycline-free TET tested FBS (Atlanta Biologicals, cat. # S10350). Stable SKD-HMEC with doxycycline-inducible c-MYC or GFP expression were generated with the T-REx Tet-on System (Invitrogen) in two steps. First, SKD-HMEC at passage 12 were infected with lentivirus encoding the 3rd generation reverse tetracycline-controlled transactivator 3 (rtTA3) and selected for with 10 μg/ml blasticidin. SKD-HMEC constitutively expressing rtTA3 (SKD/rtTA3) were subsequently infected at passage 15 using lentiviruses produced with either the pLenti CMV/TO-Neo c-MYC or pLenti CMVTRE3G-Neo eGFP vectors described above. SKD-HMEC with stable doxycycline-inducible c-MYC expression (MYC-inducible HMEC) or GFP expression (GFP-inducible HMEC) were then selected for with 200 μg/mL G418 (neomycin). For senescence-escape assays with lentiviral infections, 5 × 106 MYC-inducible SKD-HMEC at passage 18–22 were infected for 24 hours in 10 cm plates with lentiviruses encoding either empty control vector (proliferating cells) or OSM to induce senescence. After lentiviral infection, cells were grown for 72 hours in regular M87 HMEC medium. Cells were seeded 5 days post-infection in 6-well plates at 2 × 104 cells each well, with 3 triplicate wells plated for cell counting and 3 wells plated for passaging per sample, and then plates were incubated 48 hours at standard cell culture conditions. For senescence-escape assays with recombinant OSM, 5 × 106 MYC-inducible empty control vector SKD-HMEC at passage 36 were left untreated or treated with 10 ng/mL of OSM for 7 days in 15 cm plates to induce senescence. Cells were stained with C12FDG and sorted by FACS 7 days post-initial OSM exposure, then seeded in 6-well plates and cultured as described above. MYC expression was then induced 7 days post-lentiviral infection by adding M87-HMEC medium containing 0.5 μg/ml doxycycline to proliferating vector control cells and fully senescent OSM-expressing HMEC in culture. For long-term experiments, elevated MYC expression was maintained by replenishing cells with fresh medium containing 0.5 μg/ml doxycycline every 48 hours. Cells were then subjected to PD assays as described above in order to assess proliferation until the completion of the experiment. Cell number was quantified at each time point for all triplicate wells, PD was calculated, and cells were seeded into new six-well plates and grown as before. Results are presented as the mean number of PD ± SEM for all triplicate wells counted at each time point cells were passaged.

Three-dimensional cell culture, migration, and invasion assays.

Soft agar anchorage-independent growth (AIG) assays were conducted as previously described16 using type VII agarose (Sigma-Aldrich, cat. # A4018) and by seeding 5 × 104 cells in 60-mm plates in triplicate. AIG was quantified after culturing cells for 3 weeks by scanning each plate with an automated multipanel scanning microscope, and analyzing the stitched digital images using OpenCFU Software (Sourceforge) with a value of 10, regular type of threshold, and a 30 pixel minimum radius to acquire soft agar colony counts for each entire plate. Data shown for soft agar assays represent mean ± SEM of three independent biological replicates. Organotypic culture in growth factor-reduced, laminin-rich basement membrane (Matrigel) (Corning, cat. # 354230) in six-well plates was discussed in detail elsewhere.15 Organotypic cultures were visually assessed and captured by bright field microscopy at 5X magnification; images presented are one of three biological replicates. Migration and invasion assays were conducted using the live cell IncuCyte ZOOM imaging system (Essen BioScience) and IncuCyte Scratch Wound Assay protocols to measure migration or invasion into a wound region according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Concisely, cells were seeded into a 96-well ImageLock plate (Essen BioScience Cat #4379) at a density of 4 × 104 cells/well and incubated at 37°C, 5% CO2 overnight. The next day, wounds were made in all wells simultaneously using a 96-pin IncuCyte WoundMaker Tool (Essen BioScience Cat #4563). For invasion assays, cells were overlayed in each well with 50μL of 50 mg/mL growth factor-reduced Matrigel in culture media prior to microscopy anaylsis. Plates were immediately incubated and imaged at 10X magnification at the indicated time points.

Wells were imaged and analyzed using live cell Incucyte Zoom imaging software (Essen BioScience) at 4 hour intervals for 1 day to determine confluence over time, with cell migration quantified by wound width (μm) and cell invasion quantified by percent wound confluence.

Statistical analyses.

Results are presented as mean ± SEM, n = 3 independent biological replicates, unless stated otherwise. SA-β-Gal staining and qRT-PCR data were quantified as described in the above sections. Statistical analysis was performed with GraphPad Prism8 (GraphPad Software, RRID:SCR_002798) using a two-tailed unpaired Student’s t-test under the assumption of unequal variance or one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). Statistically significant differences are indicated with * when P < 0.05, ** when P < 0.01, *** when P < 0.001, and **** when P < 0.0001. Differences with a value of P > 0.05 were considered non-significant and indicated ns.

Reporting Summary.

Additional details about experimental designs are linked to this article and available.

Data availability.

Source data for figures, tables, and supplementary information is located in Supplementary Table 3. Other supporting data can be requested from corresponding author.

RESULTS

Cytokine-induced senescence induces EMT-associated gene expression changes.

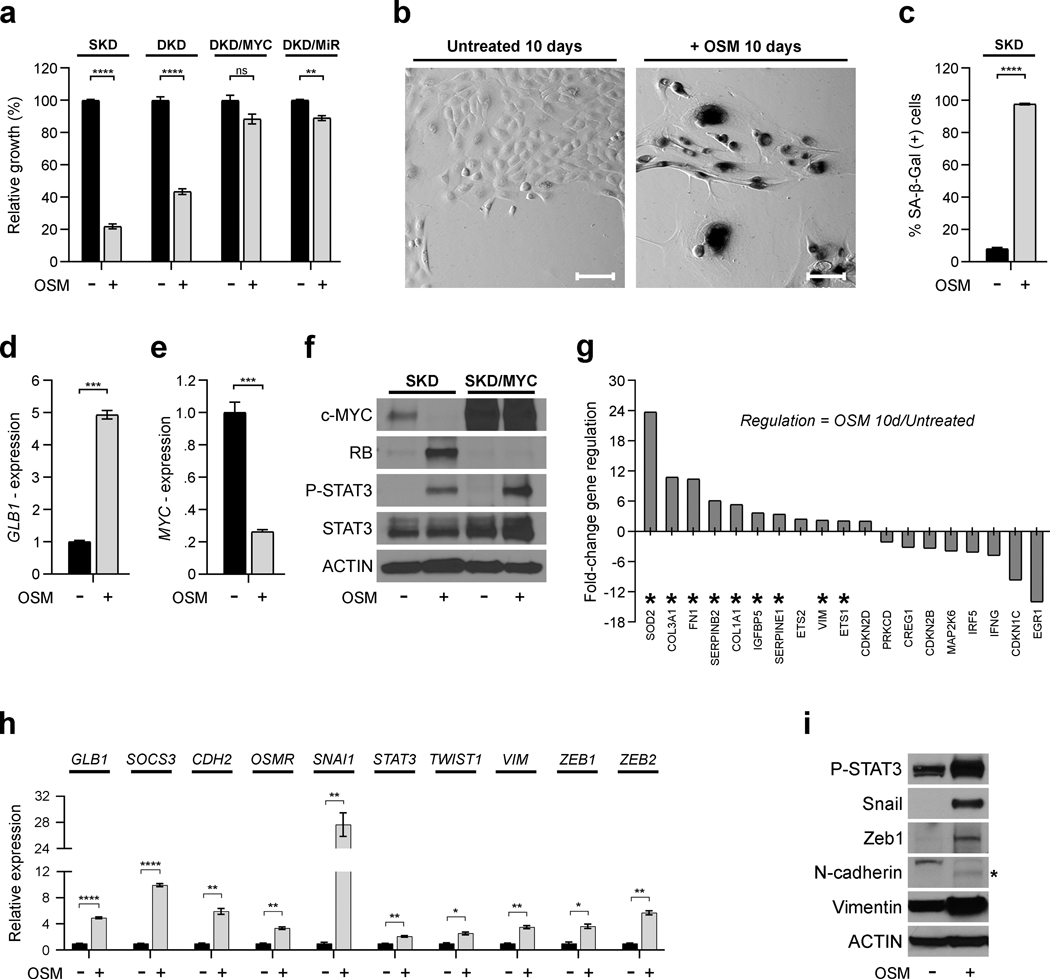

We have previously assessed the divergent roles of inflammatory cytokines, including OSM, during tumorigenesis using a stepwise model of normal, primary HMEC transformation (Supplementary Figure 1).16, 17, 19 To define the mechanisms that prevent transformation in response to OSM, we assessed early passage HMEC that harbor shp16 (SKD-HMEC, “single knock-down”) or both shp16 and shp53 (DKD-HMEC, “double knock-down”) (Supplementary Figure 1). Following exposure to recombinant OSM, the proliferation of SKD-HMEC and DKD-HMEC decreased by ~80% and ~60%, respectively (Fig. 1a). Likewise, the proliferation of unmanipulated, primary HMEC (HMEC-3A and HMEC-5A) was also suppressed (Supplementary Figure 1); confirming that p16 loss doesn’t influence OSM-induced growth inhibition. In contrast, expression of MYC in DKD-HMEC (DKD/MYC) or MYC and RAS (DKD/MiR) abrogates senescence following OSM exposure (Fig. 1a). Senescence-associated-β-galactosidase (SA-β-Gal) activity and GLB1 (encodes SA-β-Gal) are significantly increased in OSM-treated SKD-HMEC, with approximately 98% of OSM-treated cells staining positive (Fig. 1b–d). Notably, roughly 8% of untreated SKD-HMEC also stain positive for SA-β-Gal activity (Fig. 1b–c), most likely due to their limited lifespan, as they have not been immortalized by exogenous hTERT.

Fig. 1: Cytokine-induced senescence induces EMT-associated gene expression changes.

a, Relative growth assays of SKD-, DKD-, DKD/MYC-, and DKD/MiR-HMEC grown in the presence (+) and absence (−) of recombinant OSM [10 ng/mL] 10 days. b, Senescence-associated β-galactosidase (SA-β-Gal) activity staining (dark) in untreated SKD-HMEC and cells treated with OSM [10 ng/mL] for 10 days. Scale bar, 100 μm. c, Quantification of percentage of SA-β Gal-positive cells in (b), shown as mean ± SEM of counts from 3 independent microscopic fields (10X) for a minimum total of at least 375 cells counted per sample. The percentage of SA-β-Gal-positive cells was calculated as a mean of total number of SA-β-Gal-positive cells divided by total cell number per well. d-e, qRT-PCR analysis using primers targeting GLB1 (d) or MYC (e) in untreated SKD-HMEC and cells treated with OSM [10 ng/mL] for 10 days. f, Western analysis of c-MYC, the tumor suppressor retinoblastoma (RB), phosphorylated STAT3 at tyrosine 705 (P-STAT3), total STAT3, and Actin (loading control) protein levels in SKD-HMEC infected with lentivirus encoding empty control (SKD) or c-MYC (SKD/MYC) grown (+/−) OSM [10 ng/mL] for 10 days. g, mRNA from SKD-HMEC grown in the presence or absence of OSM [10 ng/mL] for 10 days was subjected to a targeted Human Cellular Senescence qRT-PCR profiler array. Genes exhibiting at least a 2-fold change in expression in OSM-treated SKD-HMEC relative to untreated cells were selected and displayed. h, qRT-PCR analysis of SKD-HMEC in the presence or absence of OSM [10 ng/mL] for 10 days using primers targeting EMT-associated genes (CDH2, OSMR, SNAI1, STAT3, TWIST1, VIM, ZEB1, ZEB2) not included on human cellular senescence profiler array in (g). i, Western analysis of protein levels for P-STAT3, Snail, Zeb1, N-cadherin, Vimentin, and Actin (loading control) in untreated SKD-HMEC and cells treated with OSM [10 ng/mL] for 10 days. Error bars indicate mean ± SEM for three technical replicates. Statistically significant differences are indicated with * when P < 0.05, ** when P < 0.01, *** when P < 0.001, and **** when P < 0.0001. Differences with a P value > 0.05 were considered non-significant and indicated with ns.

OSM-induced senescence involves the repression of endogenous c-MYC with concomitant STAT3 activation and RB stabilization (Fig. 1e–f).15, 16 Exogenous expression of MYC in SKD-HMEC (SKD/MYC-HMEC), which prevents repression of MYC protein, also prevents OSM-mediated RB stabilization and abrogates senescence without preventing STAT3 activation (Fig. 1f and Supplementary Figure 1). Our findings demonstrate that MYC acts as a molecular switch which alters the response of HMEC to OSM. To identify additional transcriptional changes associated with OSM-induced senescence, mRNA from OSM-treated SKD-HMEC and untreated controls was assessed using a human senescence qRT-PCR array. Expression changes greater than 2-fold occurred for 19 of the 84 genes on the array following OSM exposure (11 genes upregulated and 8 genes downregulated; Fig. 1g). Surprisingly, the robust OSM-induced senescence response correlated with the upregulation of only one cell cycle inhibitor, CDKN2D (encodes cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 2D; or p19INK4D), in the array (Fig. 1g). These results suggested that OSM-induced senescence may be engaged by a more non-canonical mechanism of RB and cell cycle regulation. Interestingly, 9 of the 11 genes upregulated in the array by OSM have a role in EMT (Fig. 1g, asterisks). Consistent with this finding, some of the OSM-treated cells acquired a spindle-like mesenchymal morphology (Fig. 1b, right). qRT-PCR confirmed that OSM upregulates FN1 (encodes Fibronectin 1) and SERPINE1 expression 90-fold and 20-fold, respectively (Supplementary Figure 1). OSM also upregulates SOCS3 (a STAT3 target gene) and additional mesenchymal markers, including VIM (encodes Vimentin), CDH2 (encodes N-cadherin), OSMR (encodes OSM receptor subunit β; OSMRβ), STAT3, and the EMT-TFs SNAI1 (encodes Snail), TWIST1, ZEB1, and ZEB2 (Fig. 1h). Consistent with the gene expression changes, OSM upregulated Snail, Zeb1, N-cadherin, and Vimentin protein levels and repressed E-cadherin (an epithelial cell marker) (Fig. 1i and Supplementary Figure 1). The assessment of long term population doubling (PD) confirmed that all OSM-exposed cells had undergone senescence, as no spontaneous outgrowth occurred even 54 days after initial OSM exposure (Supplementary Figure 1). Notably, this permanent OSM-induced senescence response was observed even when OSM was removed 14 or 28 days after initial OSM exposure (Supplementary Figure 1). However, SKD-HMEC interestingly reentered the cell cycle and regained a proliferative capacity similar to untreated cells when OSM was removed after 7 days (Supplementary Figure 1). Collectively, our results suggest that OSM promotes EMT concomitant with senescence in non-transformed HMEC.

A mesenchymal/SC program correlates with OSM-induced senescence intensity.

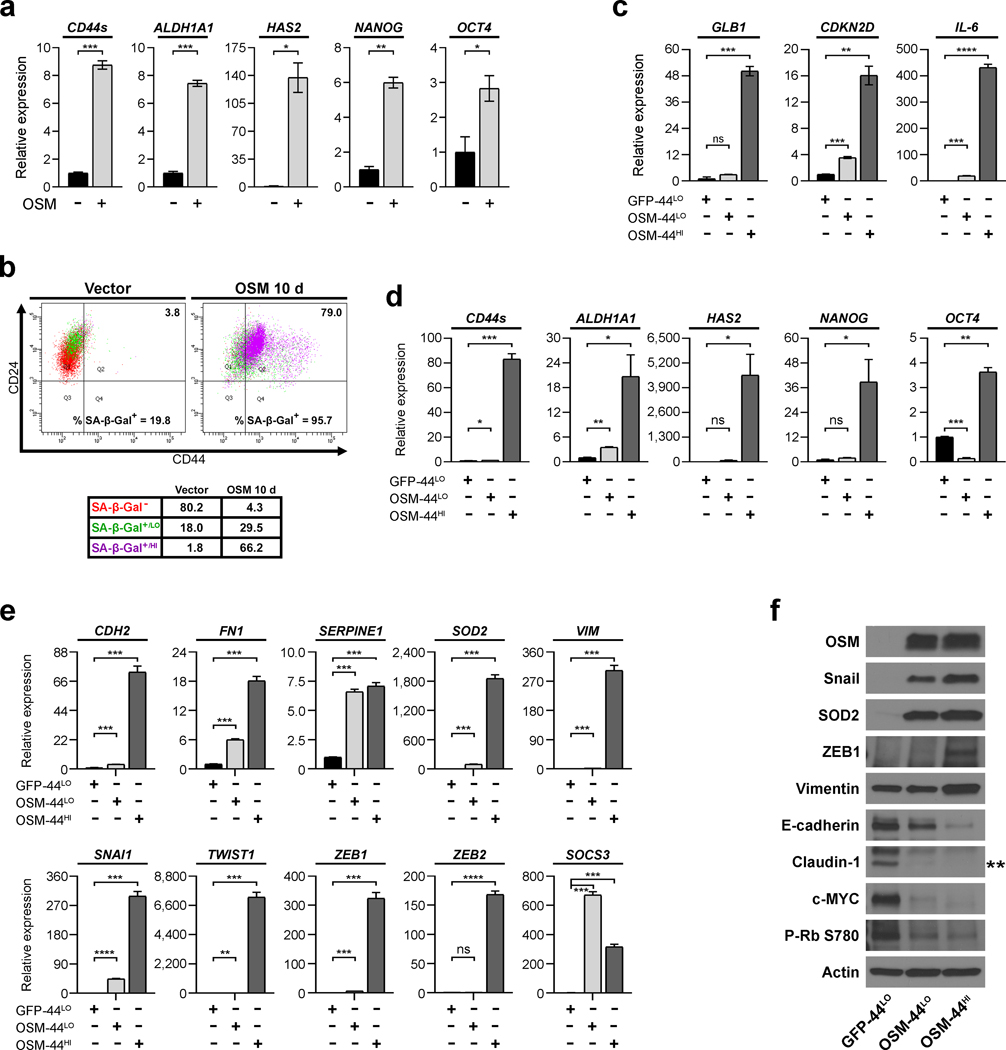

EMT can promote cancer stem cell (CSC) behaviors in cancer cells, including tumor-initiating capacity, increased migratory and invasive behaviors, and decreased sensitivity to current therapies.22 Therefore, we assessed the expression of normal and breast cancer SC-associated genes. Indeed, OSM-induced SC-markers concurrently during EMT (Fig. 2a). To further investigate whether SC-marker induction directly associated with senescence, SKD-HMEC infected with lentivirus encoding OSM or vector control were subjected to flow cytometry for CD24 and CD44, two surface markers that distinguish breast CSC (identified by a CD24LO/CD44HI profile) from non-CSC (CD24HI/CD44LO), and SA-β-Gal activity using a fluorescent SA-β-Gal substrate. Dead cells were excluded from the analysis and unlabeled cells were used to set the appropriate gates (Supplementary Figure 1). Control SKD-HMEC comprised a uniform CD24HI/CD44LO population with a subset of cells having low SA-β-Gal (SA-β-Gal+/LO) activity (Fig. 2b). OSM promoted CD44 expression, with little CD24 loss, and concomitantly increased SA-β-Gal activity in 96% of cells (Fig. 2b). Notably, most CD44HI OSM-expressing cells had high SA-β-Gal activity (SA-β-Gal+/HI), suggesting that the magnitude of induction for both senescence and a SC-phenotype directly correlate (Fig. 2b).

Fig. 2: A mesenchymal/SC program correlates with OSM-induced senescence intensity.

a, qRT-PCR analysis of the breast CSC-associated genes ALDH1A1, NANOG, OCT4, HAS2 (encodes hyaluronan synthase 2), and CD44s in untreated SKD-HMEC and cells treated 10 days with 10 ng/mL OSM. Error bars indicate mean ± SEM for three technical replicates. b, Flow cytometry of CD24 and CD44 surface-profile expression and SA-β-Gal activity via staining with the CellEvent Senescence Green Probe 10 days after SKD-HMEC were infected with lentivirus encoding empty control (Vector) or OSM. SA-β-Gal− cells shown as red, SA-β-Gal+/LO as green, and SA-β-Gal+/HI as purple. Black numbers in the upper right represent percent of the population that are CD44HI cells and black numbers at the bottom represent total percent of SA-β-Gal+ (SA-β-Gal+/LO and SA-β-Gal+/HI combined). c-f, 10 days after SKD-HMEC were infected with lentiviruses encoding either GFP or OSM and selected with the appropriate antibiotic, cells were subjected to FACS to purify three populations: CD44LO GFP-control cells (GFP-44LO) and two sub-populations of OSM-expressing cells representing the lowest CD44 expressing cells (OSM-44LO) or the highest level of CD44 (OSM-44HI). After FACS-purification, mRNA and protein harvested from each population sorted was subjected to (c-e) qRT-PCR analysis to compare the expression of (c) senescence-associated genes (GLB1, CDKN2D, IL-6), (d) breast CSC-associated genes (CD44s, ALDH1A1, HAS2, NANOG, OCT4), or (e) EMT-associated genes (CDH2, FN1, VIM, SOD2, SERPINE1, SNAI1, TWIST1, ZEB1, ZEB2); and also (f) western analysis of EMT and senescence-associated proteins. Actin was used as a loading control. Error bars indicate mean ± SEM for three technical replicates. Statistically significant differences are indicated with * when P < 0.05, ** when P < 0.01, *** when P < 0.001, and **** when P < 0.0001. Differences with a P value > 0.05 were considered non-significant and indicated with ns.

Since SA-β-Gal activity was higher in the emergent CD44HI HMEC, we hypothesized that senescence may be engaged by an inappropriate induction of a mesenchymal/de-differentiation program, similar to inappropriate proliferative signaling (i.e. oncogene-induced senescence). To test this hypothesis, SKD-HMEC were infected with lentivirus encoding either GFP as a control or OSM and selected with the appropriate antibiotic, then three populations were purified based on CD24/CD44 expression by fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS): (i) CD44LO GFP-control (GFP-44LO); (ii) CD44LO OSM-expressing cells (OSM-44LO); and (iii) CD44HI OSM-expressing cells (OSM-44HI) (Supplementary Figure 1). Senescence-associated genes4 were strongly upregulated in OSM-44HI cells relative to OSM-44LO or GFP-44LO cells (Fig. 2c and Table 1). CD44s expression was increased by 80-fold in OSM-44HI cells, confirming the integrity of the FACS (Fig. 2d). Likewise, numerous mesenchymal and SC-markers were highly expressed in senescent OSM-44HI-sorted cells (Fig. 2d–e). Interestingly, many genes that were highly expressed in OSM-44HI cells were also upregulated in OSM-44LO cells relative to the GFP-44LO cells, albeit it to a lesser extent than in the OSM-44HI cells (Fig. 2d–f and Table 1). In contrast, Zeb1 and Vimentin are increased specifically in OSM-44HI cells (Fig. 2f). E-cadherin and c-MYC were suppressed more in the OSM-44HI cells (Fig. 2f). OSM protein levels and the STAT3-responsive gene, SOCS3, were elevated in both OSM-44LO and OSM-44HI cells relative to GFP-44LO cells, ensuring that the gene expression differences noted between the OSM-44LO and OSM-44HI cells were not due to differential signal transduction (Fig. 2e–f). Likewise, Claudin-1 and RB phosphorylation at Ser780 (P-RB S780) were comparably down-regulated in the OSM-44LO and OSM-44HI. Together, these results suggest that OSM induces the reprogramming of epithelial cells to a mesenchymal/SC-like state during senescence.

Table 1. Fold-change expression of senescence-, EMT-, and CSC-associated genes in OSM-induced CD44LO and CD44HI populations.

SKD-HMEC were infected with lentiviruses encoding either GFP or OSM. 10 days after lentiviral infection, cells were subjected to FACS to purify three populations: CD44LO GFP-control cells (GFP-44LO) and two sub-populations of OSM-expressing cells representing the lowest CD44 expressing cells (OSM-44LO) or the highest level of CD44 (OSM-44HI). After FACS-purification, mRNA was harvested from each sorted population and subjected to qRT-PCR analysis to compare the expression of senescence-associated, EMT-associated, and CSC-associated genes. Data shown for relative gene expression represent the mean of technical triplicates for one experiment normalized to GFP-44LO; Statistical significance was determined by performing a two-tailed unpaired Student’s t-test using the Holm-Sidak method without assuming a consistent SD. A value of P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

| STEM CELL-ASSOCIATED GENES | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TARGET | SAMPLE | CONTROL | EXPRESSION | SEM | P-value |

| ALDHA1A | GFP-44LO | * | 1 | 0.12711 | NA |

| ALDHA1A | OSM-44LO | 3.53739 | 0.15941 | 0.0002397 | |

| ALDHA1A | OSM-44HI | 20.746 | 5.21866 | 0.0193921 | |

| CD44s | GFP-44LO | * | 1 | 0.04518 | NA |

| CD44s | OSM-44LO | 1.40321 | 0.06421 | 0.00681183 | |

| CD44s | OSM-44HI | 83.23653 | 4.26436 | 0.00004262 | |

| HAS2 | GFP-44LO | * | 1 | 0.236 | NA |

| HAS2 | OSM-44LO | 80.85253 | 23.31589 | 0.02666647 | |

| HAS2 | OSM-44HI | 4565.03869 | 1100.01984 | 0.01427126 | |

| NANOG | GFP-44LO | * | 1 | 0.37539 | NA |

| NANOG | OSM-44LO | 1.90863 | 0.22662 | 0.10696627 | |

| NANOG | OSM-44HI | 38.87018 | 10.91938 | 0.0256743 | |

| OCT4 | GFP-44LO | * | 1 | 0.03324 | NA |

| OCT4 | OSM-44LO | 0.13782 | 0.03664 | 0.00006363 | |

| OCT4 | OSM-44HI | 3.64127 | 0.17463 | 0.00011948 | |

| EMT-ASSOCIATED GENES | |||||

| TARGET | SAMPLE | CONTROL | EXPRESSION | SEM | P-value |

| CDH2 | GFP-44LO | * | 1 | 0.07867 | NA |

| CDH2 | OSM-44LO | 3.47387 | 0.11536 | 0.00005962 | |

| CDH2 | OSM-44HI | 72.91869 | 4.44801 | 0.00008565 | |

| FN1 | GFP-44LO | * | 1 | 0.0377 | NA |

| FN1 | OSM-44LO | 6.01094 | 0.1983 | 0.00001563 | |

| FN1 | OSM-44HI | 18.0955 | 0.88557 | 0.00004259 | |

| SERPINE1 | GFP-44LO | * | 1 | 0.03409 | NA |

| SERPINE1 | OSM-44LO | 6.60764 | 0.20811 | 0.00001189 | |

| SERPINE1 | OSM-44HI | 7.08524 | 0.3025 | 0.00003696 | |

| SNAI1 | GFP-44LO | * | 1 | 0.08201 | NA |

| SNAI1 | OSM-44LO | 44.29897 | 1.41655 | 0.00000687 | |

| SNAI1 | OSM-44HI | 299.06378 | 13.80684 | 0.00002724 | |

| SOD2 | GFP-44LO | * | 1 | 0.0294 | NA |

| SOD2 | OSM-44LO | 95.30145 | 3.90225 | 0.0000174 | |

| SOD2 | OSM-44HI | 1854.23846 | 77.63658 | 0.00001827 | |

| TWIST1 | GFP-44LO | * | 1 | 0.05232 | NA |

| TWIST1 | OSM-44LO | 2.14523 | 0.11849 | 0.00090337 | |

| TWIST1 | OSM-44HI | 7222.69702 | 363.26645 | 0.00003778 | |

| VIM | GFP-44LO | * | 1 | 0.06751 | NA |

| VIM | OSM-44LO | 2.53156 | 0.0703 | 0.00009581 | |

| VIM | OSM-44HI | 303.31059 | 15.65518 | 0.00004239 | |

| ZEB1 | GFP-44LO | * | 1 | 0.01384 | NA |

| ZEB1 | OSM-44LO | 6.63397 | 0.21759 | 0.00001332 | |

| ZEB1 | OSM-44HI | 323.24307 | 19.72057 | 0.0000821 | |

| ZEB2 | GFP-44LO | * | 1 | 0.03393 | NA |

| ZEB2 | OSM-44LO | 0.84141 | 0.03277 | 0.02825207 | |

| ZEB2 | OSM-44HI | 168.02446 | 5.78632 | 0.00000857 | |

| SENESCENCE/CELL CYCLE-ASSOCIATED GENES | |||||

| TARGET | SAMPLE | CONTROL | EXPRESSION | SEM | P-value |

| CDKN2D | GFP-44LO | * | 1 | 0.05609 | NA |

| CDKN2D | OSM-44LO | 3.56423 | 0.13985 | 0.00006992 | |

| CDKN2D | OSM-44HI | 16.07239 | 1.41541 | 0.00044174 | |

| GLB1 | GFP-44LO | * | 1 | 0.84761 | NA |

| GLB1 | OSM-44LO | 2.97855 | 0.02785 | 0.07998794 | |

| GLB1 | OSM-44HI | 50.20408 | 2.12816 | 0.00002778 | |

| IL-6 | GFP-44LO | * | 1 | 0.04013 | NA |

| IL-6 | OSM-44LO | 19.47945 | 0.70473 | 0.00001265 | |

| IL-6 | OSM-44HI | 432.49629 | 12.04744 | 0.00000363 | |

| SOCS3 | GFP-44LO | * | 1 | 0.87423 | NA |

| SOCS3 | OSM-44LO | 670.30449 | 22.73688 | 0.00000795 | |

| SOCS3 | OSM-44HI | 316.37404 | 17.55201 | 0.00005667 | |

OSM-mediated Snail induction drives an aberrant EMT that induces senescence.

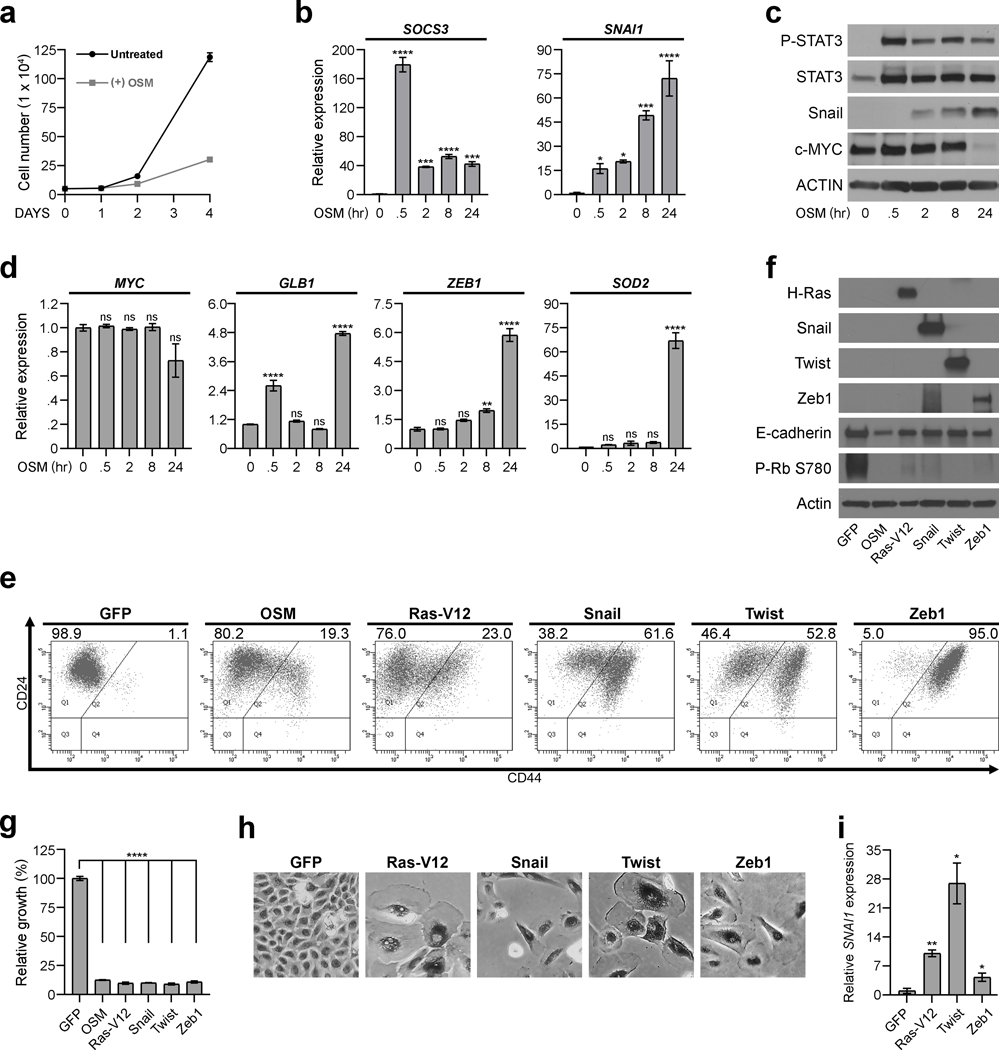

To delineate the kinetics underlying OSM-induced senescence and mesenchymal/SC reprogramming, SKD-HMEC were assessed 30 minutes to 24 hours after exposure to OSM. Whereas proliferation differences are not obvious until 2 days of OSM exposure (Fig. 3a), OSM induced SOCS3 by 175-fold and SNAI1 expression approximately 15-fold within 30 minutes (Fig. 3b). The immediate induction of SNAI1 occurred concomitant with upregulated Snail protein and STAT3 phosphorylation (Fig. 3c), and was also observed in primary HMEC (HMEC-3A and HMEC-5A) (Supplementary Figure 2). In contrast, neither senescence-associated MYC repression nor GLB1 upregulation was consistently apparent until 24 hours after OSM-treatment (Fig. 3c–d). Similarly, other OSM-induced EMT genes (ZEB1, SOD2) and SC genes (CD44, ALDH1A1, HAS2) were not upregulated until 24 hours of OSM treatment (Fig. 3d and Supplementary Figure 2). Given that Snail induction uniquely preceded senescence-associated gene expression changes or growth inhibition, we hypothesized that OSM-induced Snail activates EMT and a SC-program, which is viewed by the cell as inappropriate, resulting in a protective, senescence response. To test this hypothesis, Snail was expressed in SKD-HMEC. In addition, Twist, Zeb1, and mutant H-RAS V12 (Ras-V12), which promotes oncogene-induced senescence, were included for comparison with OSM. Expression of Snail, Twist, Zeb1, and Ras-V12 increased CD44, reduced E-cadherin and RB phosphorylation, and reduced cell number by ~90% compared to GFP control. Likewise, each population displayed an enlarged and flattened senescent morphology, and increased SA-β-Gal activity (Fig. 3e–h). Interestingly, SNAI1 was upregulated in each senescent population (Ras-V12, Snail, Twist, Zeb1; Fig. 3i). In contrast to OSM, Ras-V12, and EMT-TFs, expression of CD44 or HAS2 (Hyaluronan Synthase 2) failed to alter proliferation, or induce EMT markers (Supplementary Figure 2). These results indicate that the aberrant reprogramming to a mesenchymal/SC-like state, mediated by either OSM or EMT-TF expression, engages senescence.

Fig. 3: OSM-mediated Snail induction drives an aberrant EMT that induces senescence.

a, Growth curve of SKD-HMEC left untreated or treated with OSM [10 ng/mL] for 1, 2, and 4 days. The mean cell number ± SEM (error bars) of all biological triplicates are presented for each time point. b-d, SKD-HMEC were serum-starved for 24 hours and then left untreated or subjected to a time course treatment with OSM [10 ng/mL] for .5, 2, 8, or 24 hours. At each time point, mRNA and protein were harvested from cells and subjected to (b) qRT-PCR analysis using primers targeting SOCS3 and SNAI1; (c) western analysis examining protein levels of P-STAT3, total STAT3, Snail, c-MYC, and Actin as a loading control; or (d) qRT-PCR analysis using primers targeting MYC or GLB1 to assess proliferation and senescence-associated gene changes as well as ZEB1 and SOD2 to assess EMT-associated gene changes. Error bars indicate mean ± SEM for three technical replicates. e, Flow cytometry of CD24 and CD44 surface-profile expression in GFP, OSM, H-Ras V12 (Ras-V12), Snail, Twist, and Zeb1-expressing SKD-HMEC 10 days post lentiviral-infection. Black numbers represent the percent of total cell population that are CD44LO (left) or CD44HI (right). f, Western analysis to confirm elevated protein levels in each respective SKD-HMEC derivative 10 days after infection with lentiviruses encoding GFP, OSM, Ras-V12, Snail, Twist, or Zeb1. g, Relative growth assays of SKD-HMEC derivatives expressing GFP, OSM, Ras-V12, Snail, Twist, or Zeb1 10 days post lentiviral-infection. Error bars indicate mean ± SEM for three technical replicates. h, Brightfield microscopy (10X) of senescence-associated β-galactosidase (SA-β-Gal) activity staining (dark) in GFP, Ras-V12, Snail, Twist, and Zeb1-expressing SKD-HMEC. i, qRT-PCR analysis of SNAI1 expression in SKD-HMEC 10 days after infection with lentiviruses encoding either GFP, Ras-V12, Twist, or Zeb1. Error bars indicate mean ± SEM of three independent experiments. Statistically significant differences are indicated with * when P < 0.05, ** when P < 0.01, *** when P < 0.001, and **** when P < 0.0001. Differences with a P value > 0.05 were considered non-significant and indicated with ns.

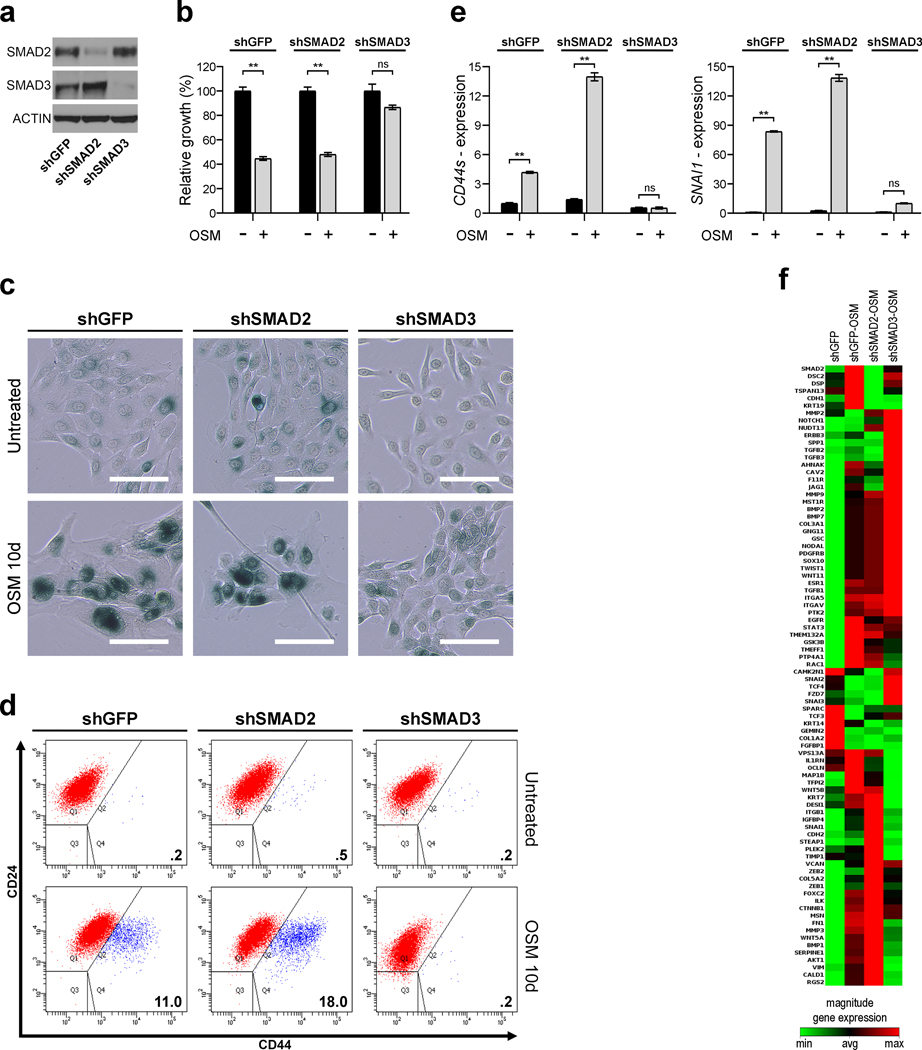

OSM-induced Snail expression requires STAT3- and TGF-β/SMAD3-mediated signaling.

In fully transformed cells, OSM/STAT3-induced Snail expression and mesenchymal/CSC reprogramming requires functional TGF-β/SMAD3 signaling.17 Thus, we hypothesized that OSM-induced Snail expression observed prior to mesenchymal/SC-marker expression in non-transformed HMEC is also dependent on the OSM/STAT3/SMAD3 axis. To identify whether SMAD proteins contributed to OSM/STAT3-induced mesenchymal/SC-like program, shRNAs targeting SMAD2 or SMAD3 were expressed in SKD-HMEC and the suppression by each was confirmed (Fig. 4a). In addition to preventing OSM-induced senescence, cells expressing shSMAD3, but not shSMAD2, failed to induce CD44 (CD44s) or SNAI1, as well as blunting other EMT-associated genes in response to OSM (Fig. 4b–e and Supplementary Figure 3). To test a larger class of EMT genes, mRNA from untreated shGFP cells and OSM-treated shGFP-, shSMAD2-, or shSMAD3-expressing cells were examined and compared using an EMT qRT-PCR profiler array. Non-supervised hierarchical clustering identified OSM-treated shGFP and shSMAD2 cells as having comparable, co-regulated EMT-gene signatures while OSM-treated shSMAD3 cells had a distinct gene expression pattern (Fig. 4f). Importantly, many EMT genes upregulated in OSM-treated shGFP and shSMAD2 cells, including SNAI1, CDH2, VIM, FN1, SERPINE1, WNT5A, BMP1, FOXC2, FZD7, KRT7, TFPI2, MAP1B, PTP4A1, and IGFBP4, were suppressed in the absence of SMAD3 (Fig. 4f). Overall, our results suggest the OSM/STAT3 and TGF-β/SMAD3 pathways converge in normal epithelial cells to induce Snail, which subsequently initiates the mesenchymal/SC program responsible for triggering senescence.

Fig. 4: OSM-induced Snail expression requires STAT3- and TGF-β/SMAD3-mediated signaling.

a, Western analysis of SMAD2, SMAD3, and ACTIN (loading control) levels in SKD-HMEC expressing shRNAs targeting GFP (shGFP), SMAD2 (shSMAD2), or SMAD3 (shSMAD3). b-f, SKD-HMEC expressing shRNAs targeting GFP (shGFP), SMAD2 (shSMAD2), or SMAD3 (shSMAD3) were left untreated or treated with recombinant OSM [10 ng/mL] for 10 days and then subjected to the following assays. b, Relative growth assays of shGFP-, shSMAD2-, and shSMAD3-expressing HMEC grown in the presence (+) and absence (−) of OSM. Mean ± SEM (error bars) of all triplicates are presented for each sample. c, Senescence-associated β-galactosidase (SA-β-Gal) activity staining (blue) in untreated shGFP-, shSMAD2-, and shSMAD3-expressing HMEC and cells treated with OSM. Scale bar, 150 μm. d, Flow cytometry of CD24 and CD44 surface-profile expression in shGFP-, shSMAD2-, and shSMAD3-expressing SKD-HMEC grown in the presence (+) and absence (−) of OSM. CD44LO cells are shown as red and CD44HI cells as blue. Black numbers represent the percent of total cell population that are CD44HI. e, qRT-PCR analysis of cells grown in the presence (+) and absence (−) of OSM using primers targeting CD44s (SC gene; left) and SNAI1 (EMT gene; right) f, Following treatment with OSM [10 ng/mL] for 10 days, mRNA was harvested from shGFP-, shSMAD2-, or shSMAD3-expressing SKD-HMEC and subjected to a targeted Human EMT qRT-PCR profiler array. Heat map displaying non-supervised hierarchical clustering of fold-regulation gene expression data between OSM-treated cells relative to untreated shGFP-cells with the brightest green representing the smallest value, brightest red the highest value, and black the average magnitude of gene expression. Error bars indicate mean ± SEM of three independent experiments. Statistically significant differences are indicated with * when P < 0.05, ** when P < 0.01, *** when P < 0.001, and **** when P < 0.0001. Differences with a P value > 0.05 were considered non-significant and indicated with ns.

Senescence-escape generates transformed CSC.

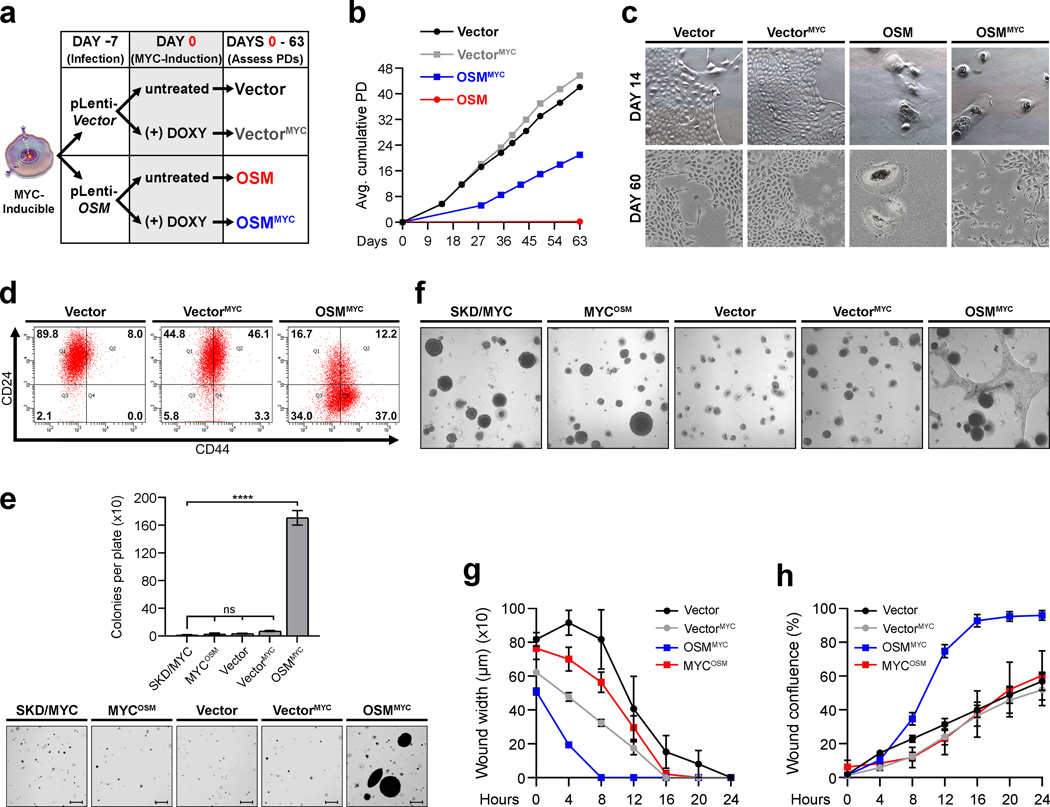

Recent observations identified that cancer cells can escape therapy-induced senescence (TIS), which results in dedifferentiation and acquisition of CSC properties.10 We hypothesized that mesenchymal/SC program responsible for inducing senescence in non-transformed cells may persist even as cells escape senescence. If true, these cells may continue to harbor traits commonly associated with the mesenchymal/SC program as they complete the transformation process. To test this hypothesis, we generated SKD-HMEC with doxycycline-inducible MYC (MYC-inducible) expression. Upon doxycycline addition, MYC was induced to levels that are comparable to endogenous MYC in triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) cell lines MDA-MB-231 and Hs578T (Supplementary Figure 4). Importantly, OSM-induced senescence was comparable in control (GFP-inducible) and MYC-inducible cells grown in the absence of doxycycline (Supplementary Figure 4). In contrast, the addition of doxycycline to MYC-inducible cells prior to OSM exposure prevented senescence comparably to constitutive CMV promoter-driven MYC expression (SKD/MYC-HMEC) (Supplementary Figure 4). Our earlier findings indicated that senescent SKD-HMEC reenter the cell cycle and began to proliferate when OSM is removed after 7 days of exposure (Supplementary Figure 1). Thus, we next assessed whether inducing MYC expression 7 days after OSM expression could also prompt an escape from senescence (Fig. 5a). Indeed, induction of MYC 7 days after OSM expression (OSMMYC) resulted in the emergence of a small population of proliferating cells (Fig. 5b; blue line), while OSM-expressing cells grown in the absence of doxycycline (OSM; no MYC expression) failed to grow (Fig. 5b; red line). Moreover, in the absence of OSM, control (Vector; Fig. 5b, black line) and MYC-expressing (VectorMYC; Fig. 5b, gray line) cells proliferated comparably and all cells maintained an epithelial morphology (Fig. 5c, top). After escaping senescence, the OSMMYC cells lost all senescence-associated morphological features, and a subpopulation of cells exhibiting a spindle-like, mesenchymal morphology was evident (Fig. 5c, bottom). Importantly, only the OSMMYC cells that had escaped from senescence exhibited a CD24LO/CD44HI CSC phenotype, acquired the ability to grow anchorage-independently in soft agar, had an enhanced migratory capacity, and were highly invasive in 3-dimensional organotypic culture (Fig. 5d–h). In contrast, cells constitutively expressing MYC (SKD/MYC-HMEC) that had never undergone senescence following OSM expression (MYCOSM) remained epithelial, retained a CD24HI/CD44LO profile, did not grow anchorage-independently, and were less migratory and invasive (Fig. 5e–h and Supplementary Figure 4). To further evaluate whether senescence-escape leads to the development of transformed CSC, we subsequently subjected MYC-inducible Vector control HMEC to another senescence-escape assay. This time, Vector control cells were treated for 7 days with OSM and then stained with the fluorescent β-galactosidase substrate, C12FDG. Unlabeled and labeled cells were subjected to FACS, then recombinant OSM-induced senescent cells (rOSM) were gated and sorted based on high SA-β-Gal activity (Supplementary Figure 4). Purified Untreated and rOSM cell populations were then grown continuously with rOSM exposure in the absence or presence of doxycycline to once again activate MYC expression (UntreatedMYC and rOSMMYC cells). Much like before, MYC induction 7 days after initial OSM exposure resulted in the generation of proliferating rOSMMYC cells that no longer stained positive for SA-β-gal activity 30 days after the cell populations were sorted (Supplementary Figure 4). Most importantly, only rOSMMYC cells exhibited significantly elevated expression of the CSC marker gene, CD44s, and the mesenchymal genes, SNAI1 and ZEB1, with concomitant repression of the epithelial gene, CDH1 (Supplementary Figure 4). Of note, we observed that the rOSM (without MYC-induction) cells were not fully senescent and had selected for elevated MYC expression during the course of the senescence-escape assay, explaining how they continued to proliferate at later time points (Supplementary Figure 4). These results suggest that, while senescence serves to initially suppress tumorigenesis, it also enables premalignant cells to acquire mesenchymal/SC features that, upon senescence-escape can lead to the emergence of transformed mesenchymal/SC-like cells.

Fig. 5: Senescence-escape generates transformed CSC.

a, Schematic of senescence-escape assay in (b-c). b, Growth curve of senescence-escape assay displaying cumulative average population doublings (PD) for MYC-Inducible SKD-HMEC infected with lentivirus encoding empty control (Vector) or (OSM). 7 days post-infection with lentiviruses, Vector and OSM cells were grown in the absence or presence (VectorMYC and OSMMYC) of doxycycline at .5 μg/mL. Cell number was counted to quantify PD at the indicated times. Error bars indicate mean ± SEM for biological triplicates. c, Brightfield microscopy images (10X) of cells from (b) 14 and 60 days post-infection with lentiviruses encoding control vector or OSM. d, Flow cytometry of CD24/CD44 surface-profile expression in Vector, VectorMYC, and OSMMYC cells. Black numbers represent percent of total cell population in each quadrant. e, Number of colonies per plate and representative images of anchorage-independent growth (AIG) for SKD/MYC HMEC infected with lentivirus encoding empty control (SKD/MYC) or OSM (MYCOSM), and Vector, VectorMYC, and OSMMYC cells from (a-d) grown in soft agar. Bars represent mean ± SEM of biological triplicates. Scale bar, 100 μm. f, Brightfield microscopy images (10X) of 3-dimensional matrigel cultures of cells from (e). g-h, Incucyte assays assessing migration (g) or invasion (h) over 24 hours for Vector, VectorMYC, OSMMYC, and MYCOSM cells from e-f. Data represents mean ± SEM (error bars) of all biological replicates at each point. Statistically significant differences are indicated with * when P < 0.05, ** when P < 0.01, *** when P < 0.001, **** when P < 0.0001, or ns when P> 0.05 and considered non-significant.

Senescence-escaped mesenchymal/CSC and MYC-expressing TNBC are sensitive to palbociclib.

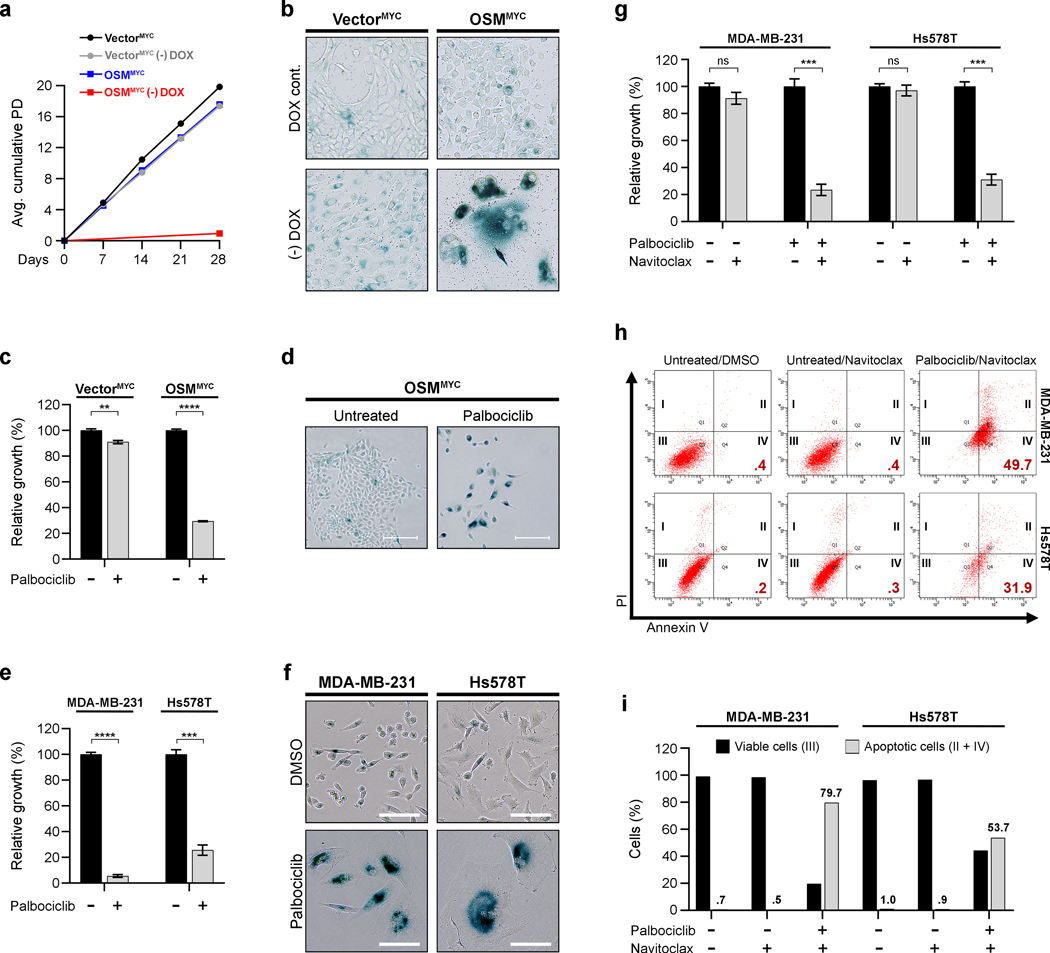

The proliferation of senescence-escaped OSMMYC cells is dependent on sustained MYC expression, as senescence was reengaged upon doxycycline removal (Fig. 6a–b). Recently, the CDK4/6 inhibitor, palbociclib, has been approved for advanced, luminal breast cancers.23 The preclinical activity of palbociclib in TNBC has also led to clinical trials in these patients. Interestingly, palbociclib has been shown to block cell cycle progression and inhibit growth in TNBC cells by not only preventing CDK4/6-Cyclin D1-mediated RB phosphorylation, but by also downregulating c-MYC expression and activity.23 Therefore, we hypothesized that CDK4/6 inhibition may provide a therapeutic opportunity to treat transformed CSC that emerged from senescence due to MYC expression. Indeed, palbociclib strongly suppressed the growth of CD24LO/CD44HI, OSMMYC cells, which had escaped senescence, but not the CD24HI/CD44LO, VectorMYC control cells (Fig. 6c). The inhibition of OSMMYC proliferation was accompanied by the emergence of an enlarged, flattened morphology and increased SA-β-Gal activity (Fig. 6d and Supplementary Figure 4). Correspondingly, in established TNBC cells that express elevated levels of endogenous MYC (MB-MDA-231 and Hs578T; Supplementary Figure 4), palbociclib similarly induced senescence (Fig. 6e–f). We next postulated that senolytic drugs, which selectively induce apoptosis in senescent cells, may form potent two-step combinatorial treatment with senescence-inducing therapies, like palbociclib. To test this, TNBC cells induced into senescence by palbociclib were treated with navitoclax (ABT-263), a BCL-2 family inhibitor and one of the first senolytic drugs identified.24 Remarkably, navitoclax selectively induced apoptosis only in the palbociclib-treated TNBC whereas actively proliferating cells (those that were not pre-treated with palbociclib) remained proliferative and viable. Notably, navitoclax did not significantly ablate growth in HMEC which are resistant and do not engage senescence in response to palbociclib treatment, such as VectorMYC control cells (Supplementary Figure 4). Altogether our results demonstrate that palbociclib can selectively reestablish senescence in TNBC harboring elevated MYC expression, making them susceptible to senolytic therapies.

Fig. 6: Senescence-escaped CSC and MYC-expressing TNBC are highly sensitive to palbociclib.

a, Growth curves displaying cumulative average population doublings (PD) for VectorMYC and OSMMYC HMEC grown 28 days in the continued presence of .5 μg/mL doxycycline or its absence after removal (-DOX). Cell number counted to quantify PD at indicated times. Error bars indicate mean ± SEM for biological triplicates. b, SA-β-Gal activity staining (blue) of VectorMYC and OSMMYC HMEC grown 10 days with .5 μg/mL doxycycline or in its absence (-DOX) after removal. Scale bar, 100 μm. c, Relative growth assays of VectorMYC and OSMMYC HMEC grown 10 days ± .25 μM palbociclib. Data represents mean ± SEM (error bars) of biological triplicates. d, SA-β-Gal activity staining (blue) in OSMMYC HMEC grown ± .25 μM palbociclib 10 days. Scale bar, 100 μm. e, Relative growth assays of MYC-overexpressing TNBC cells (MDA-MB-231 and Hs578T) treated 7 days ± 1 μM palbociclib. Data represents mean ± SEM (error bars) of biological triplicates. f, SA-β-Gal activity staining (blue) in MDA-MB-231 and Hs578T cells grown 7 days ± 1 μM palbociclib. Scale bar, 100 μm. g, Relative growth assays of MDA-MB-231 and Hs578T grown ± 1 μM palbociclib 7 days, then treated ± .5 μM navitoclax for 5 days. Data represents mean ± SEM (error bars) for biological triplicates. h-i, MDA-MB-231 and Hs578T cells grown 7 days ± 1 μM palbociclib were then treated 24 hours with DMSO or .5 μM navitoclax, stained with FITC-conjugated Annexin V and propidium iodide (PI), and analyzed by flow cytometry. (h) Flow cytometric plots distinguish early-stage apoptotic cells (Annexin V+/PI-; Gate IV), late-stage apoptotic and necrotic cells (Annexin V+/PI+; Gate II), and viable cells (Annexin V-/PI-; Gate III). Black roman numerals indicate gates and red numbers % early-stage apoptotic cells (Annexin V+/PI-; Gate IV). (i) Quantitation of percentage of viable cells (Annexin V-/PI-; Gate III) and total Annexin V+ apoptotic cells (Annexin V+/PI-; Gate IV and Annexin V+/PI+; Gate II) for populations displayed in h. Statistically significant differences indicated with * when P < 0.05, ** when P < 0.01, *** when P < 0.001, **** when P < 0.0001, or ns when P> 0.05 and considered non-significant.

DISCUSSION

Inflammatory cytokines are major regulators of senescence.4, 25 Therefore, delineating how inflammatory cytokines engage senescence in normal epithelial cells is imperative if we seek to reestablish these hidden tumor-suppressive barriers in cancer cells. Our studies provide insight into how inflammatory cytokine-mediated senescence functions as a tumor-suppressive barrier. Immune cell infiltration is observed during the earliest stages of transformation, with hyperplasic regions in breast, prostate, and colon tissues often harboring senescent epithelial cells together with the infiltrating immune cells.4, 5, 13, 14 As an inflammatory cytokine and SASP factor26, 27, OSM is commonly found near senescent cells in these early-stage benign lesions.7, 12–14 We suggest that the OSM-induced mesenchymal/CSC program, which is normally suppressed in differentiated epithelial cells28, is detected as an inappropriate stressor, much like aberrant oncogene signaling, resulting in senescence.9–11 Considering that senescence escape and immortalization are important barriers to tumor development and progression, genetic events that can help achieve both (such as elevated MYC) would be highly valuable for developing cancer cells.29, 30

Recent findings showing that chemotherapy and radiation-induced senescence in cancer cells is eventually followed by proliferation, both in vitro and in vivo21, 31–36, counter the notion that senescence is an irreversible proliferative arrest.31, 36–38 As cancer cells escape from therapy-induced senescence (TIS), they acquire mesenchymal and CSC markers and properties.21, 31–36 What remained unanswered from these studies was whether non-transformed cells can similarly escape an established senescence program, and if so, whether senescence-escape promotes plasticity and stemness prior to malignancy? Our studies begin to address these questions by demonstrating that like cancer cells following TIS,39, 40 normal and non-transformed HMEC can escape CIS. A recent assessment of human invasive breast carcinomas identified that 83.7% of tumors contain senescent cells, despite not yet being exposed to chemotherapy or radiation.41 Interestingly, 88.9% of TNBC do not contain senescent cells.41 Consistent with this observation, TNBC may possess a more prominent ability to escape senescence by upregulating MYC or downstream Cyclin/CDK activity compared to other BC subtypes.42 MYC acts as a molecular switch to turn a tumor-suppressive CIS into a tumor-promoting mesenchymal/CSC program not only for OSM, but for other SASP inflammatory cytokines as well, including IL-6 and TGF-β.4, 15, 16, 22 These findings further illuminate the paradoxical nature of inflammatory cytokines and suggest that normal epithelial cells may commonly activate an aberrant mesenchymal/CSC program in response to additional cytokines, but evidence of the program may often remain cloaked by senescence.

Notably, escape from CIS led to the expansion of a transformed, mesenchymal/CSC population harboring cancer cell behaviors (AIG, increased migratory and invasive potential); in contrast, cells expressing MYC prior to OSM exposure that had simply bypassed senescence (i.e had never engaged the senescence program) did not acquire a transformed, mesenchymal/CSC phenotype. Yet, cells that escape OSM-mediated CIS and TNBC cells are highly sensitive to the CDK4/6 inhibitor palbociclib, confirming that the mechanisms allowing cells to escape senescence are reversible and targetable. Importantly, “pro-senescence” therapies such as palbociclib create a further vulnerability in these aggressive cells to “senolytic” therapies. This two-step pro-senescence/senolytic combinatorial treatment regimen selectively induces apoptosis in the senescent cancer cells.43 If successful in patients, such an approach could target mesenchymal/CSC in both primary and metastatic tumors, while also having the added benefit of removing senescent normal cells, which cause many of the side effects common during chemotherapy.44

Mechanistically, we show that OSM-induced senescence requires cooperative STAT3/SMAD3 signaling, which rapidly induces Snail expression. Our previous studies using transformed HMEC identified that OSM-activated STAT3 mediates SMAD3-recruitment to the SNAI1 promoter, and that Snail expression alone sufficiently induces EMT and CSC properties (Supplementary Figure 5).17 Here, we show that OSM/STAT3/SMAD3 signaling also induces Snail and an aberrant mesenchymal/CSC program in normal epithelial cells. Importantly, expressing Snail or the EMT-TFs, Twist and Zeb1, alone is sufficient to induce RB hypophosphorylation and senescence. What remains unclear currently, is how STAT3/SMAD3-induced Snail expression engages senescence in normal HMEC. Snail has been shown to decrease cell growth by upregulating p21CIP1 and p15INK4B upregulation or downregulating cyclin D1 and D2.45, 46 Whether OSM-induced senescence is due to direct Snail-mediated control of cell cycle-regulating proteins has yet to be determined. Moreover, we recognize that the ability of OSM or exogenous EMT-TFs (Snail, Twist, and Zeb1) to induce senescence conflicts with previous reports showing that EMT-TFs allow cells to bypass senescence to help drive unrestrained cancer cell growth.28, 47–50 These conflicting observations may be explained by the use of different cell types, as previous studies utilized murine and human fibroblasts as cellular models.28, 47–50 In addition, ectopic hTERT expression was used in previous HMEC models, but was not employed here. hTERT overexpression abrogates senescence and additionally permits TGF-β to induce EMT and CSC properties in immortalized HMEC.3, 22, 28, 30

Taken together, our study suggests that a premalignant cell’s arduous escape from CIS can bestow increased stemness when compared to a cell that has never engaged senescence. Moreover, our findings may explain why some premalignant cells have an increased potential to disseminate even before complete transformation, as this mesenchymal program bestows increased migratory and invasive phenotypes. Our studies provide important insight into how CIS barriers that are eroded during transformation can be exploited as potential therapies to reengage senescence. Together with our expanding knowledge about how senescent cells can be targeted, new senescence/senolytic combinations can be developed to upgrade our repertoire of cancer treatments, providing much needed options to help improve patient survival.

Supplementary Material

IMPLICATIONS.

These studies reveal how a normal cell’s arduous escape from senescence can bestow aggressive features early in the transformation process, and how this persistent mesenchymal/stem-cell program can create a novel potential targetability following tumor development.

Acknowledgments

Financial Support: S. Taylor. was supported by the NIH/NCI fellowship grant (F30 CA224979) and T32 GM007250 (CWRU MSTP). M. Jackson is supported by the US NIH (R01CA138421) and the American Cancer Society (Research Scholar Award # RSG CCG-122517). Additional support was provided by the Case Comprehensive Cancer Center (P30 CA43703; Cytometry & Imaging Microscopy Core Facility).

Footnotes

SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION

Supplementary information and Source Data files for this paper are available in the online version of this paper.

Competing interests: The authors declare no potential conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Colotta F, Allavena P, Sica A, Garlanda C. & Mantovani A. Cancer-related inflammation, the seventh hallmark of cancer: links to genetic instability. Carcinogenesis 30, 1073–1081 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ren JL, Pan JS, Lu YP, Sun P. & Han J. Inflammatory signaling and cellular senescence. Cell Signal 21, 378–383 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Suram A. et al. Oncogene-induced telomere dysfunction enforces cellular senescence in human cancer precursor lesions. EMBO J 31, 2839–2851 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kuilman T. et al. Oncogene-induced senescence relayed by an interleukin-dependent inflammatory network. Cell 133, 1019–1031 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Furth EE et al. Induction of the tumor-suppressor p16(INK4a) within regenerative epithelial crypts in ulcerative colitis. Neoplasia 8, 429–436 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Majumder PK et al. A prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia-dependent p27 Kip1 checkpoint induces senescence and inhibits cell proliferation and cancer progression. Cancer Cell 14, 146–155 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Savarese TM et al. Coexpression of oncostatin M and its receptors and evidence for STAT3 activation in human ovarian carcinomas. Cytokine 17, 324–334 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zattra E, Fortina AB, Bordignon M, Piaserico S. & Alaibac M. Immunosuppression and melanocyte proliferation. Melanoma Res 19, 63–68 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Coppe JP, Desprez PY, Krtolica A. & Campisi J. The senescence-associated secretory phenotype: the dark side of tumor suppression. Annu Rev Pathol 5, 99–118 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lecot P, Alimirah F, Desprez PY, Campisi J. & Wiley C. Context-dependent effects of cellular senescence in cancer development. Br J Cancer 114, 1180–1184 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Burton DGA & Stolzing A. Cellular senescence: Immunosurveillance and future immunotherapy. Ageing Res Rev 43, 17–25 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mitsui H. et al. Discrimination of Dysplastic Nevi from Common Melanocytic Nevi by Cellular and Molecular Criteria. J Invest Dermatol 136, 2030–2040 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Royuela M. et al. Immunohistochemical analysis of the IL-6 family of cytokines and their receptors in benign, hyperplasic, and malignant human prostate. J Pathol 202, 41–49 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Garcia-Tunon I. et al. OSM, LIF, its receptors, and its relationship with the malignance in human breast carcinoma (in situ and in infiltrative). Cancer Invest 26, 222–229 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kan CE, Cipriano R. & Jackson MW c-MYC functions as a molecular switch to alter the response of human mammary epithelial cells to oncostatin M. Cancer Res 71, 6930–6939 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bryson BL, Junk DJ, Cipriano R. & Jackson MW STAT3-mediated SMAD3 activation underlies Oncostatin M-induced Senescence. Cell Cycle 16, 319–334 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Junk DJ et al. Oncostatin M promotes cancer cell plasticity through cooperative STAT3-SMAD3 signaling. Oncogene 36, 4001–4013 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Milanovic M. et al. Senescence-associated reprogramming promotes cancer stemness. Nature 553, 96–100 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Junk DJ, Cipriano R, Bryson BL, Gilmore HL & Jackson MW Tumor microenvironmental signaling elicits epithelial-mesenchymal plasticity through cooperation with transforming genetic events. Neoplasia 15, 1100–1109 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Junk DJ, Cipriano R, Stampfer M. & Jackson MW Constitutive CCND1/CDK2 activity substitutes for p53 loss, or MYC or oncogenic RAS expression in the transformation of human mammary epithelial cells. PLoS One 8, e53776 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Alotaibi M. et al. Radiosensitization by PARP Inhibition in DNA Repair Proficient and Deficient Tumor Cells: Proliferative Recovery in Senescent Cells. Radiat Res 185, 229–245 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mani SA et al. The epithelial-mesenchymal transition generates cells with properties of stem cells. Cell 133, 704–715 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.DeMichele A. et al. CDK 4/6 inhibitor palbociclib (PD0332991) in Rb+ advanced breast cancer: phase II activity, safety, and predictive biomarker assessment. Clin Cancer Res 21, 995–1001 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chang J. et al. Clearance of senescent cells by ABT263 rejuvenates aged hematopoietic stem cells in mice. Nat Med 22, 78–83 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Acosta JC et al. A complex secretory program orchestrated by the inflammasome controls paracrine senescence. Nat Cell Biol 15, 978–990 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Acosta JC et al. Chemokine signaling via the CXCR2 receptor reinforces senescence. Cell 133, 1006–1018 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.De Ceuninck F, Dassencourt L. & Anract P. The inflammatory side of human chondrocytes unveiled by antibody microarrays. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 323, 960–969 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Morel AP et al. EMT inducers catalyze malignant transformation of mammary epithelial cells and drive tumorigenesis towards claudin-low tumors in transgenic mice. PLoS Genet 8, e1002723 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Novak P, Jensen TJ, Garbe JC, Stampfer MR & Futscher BW Stepwise DNA methylation changes are linked to escape from defined proliferation barriers and mammary epithelial cell immortalization. Cancer Res 69, 5251–5258 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Garbe JC et al. Immortalization of normal human mammary epithelial cells in two steps by direct targeting of senescence barriers does not require gross genomic alterations. Cell Cycle 13, 3423–3435 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gewirtz DA, Alotaibi M, Yakovlev VA & Povirk LF Tumor Cell Recovery from Senescence Induced by Radiation with PARP Inhibition. Radiat Res 186, 327–332 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shelton JW et al. In vitro and in vivo enhancement of chemoradiation using the oral PARP inhibitor ABT-888 in colorectal cancer cells. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 86, 469–476 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chow JP et al. PARP1 is overexpressed in nasopharyngeal carcinoma and its inhibition enhances radiotherapy. Mol Cancer Ther 12, 2517–2528 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Efimova EV et al. Poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase inhibitor induces accelerated senescence in irradiated breast cancer cells and tumors. Cancer Res 70, 6277–6282 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Barreto-Andrade JC et al. Response of human prostate cancer cells and tumors to combining PARP inhibition with ionizing radiation. Mol Cancer Ther 10, 1185–1193 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gewirtz DA, Holt SE & Elmore LW Accelerated senescence: an emerging role in tumor cell response to chemotherapy and radiation. Biochem Pharmacol 76, 947–957 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Munoz-Espin D. & Serrano M. Cellular senescence: from physiology to pathology. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 15, 482–496 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chakradeo S, Elmore LW & Gewirtz DA Is Senescence Reversible? Curr Drug Targets 17, 460–466 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Le Duff M. et al. Regulation of senescence escape by the cdk4-EZH2-AP2M1 pathway in response to chemotherapy. Cell Death Dis 9, 199 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sabisz M. & Skladanowski A. Cancer stem cells and escape from drug-induced premature senescence in human lung tumor cells: implications for drug resistance and in vitro drug screening models. Cell Cycle 8, 3208–3217 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cotarelo CL et al. Detection of cellular senescence within human invasive breast carcinomas distinguishes different breast tumor subtypes. Oncotarget 7, 74846–74859 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]