Abstract

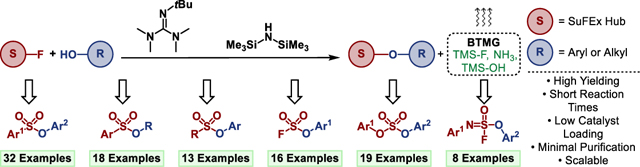

SuFEx click chemistry is a powerful method designed for the selective, rapid and modular synthesis of functional molecules. Classical SuFEx reactions form stable S-O linkages upon exchange of S-F bonds with aryl silyl-ether substrates, and while near-perfect in their outcome, are sometimes disadvantaged by relatively high catalyst loadings and prolonged reaction times. We herein report the development of ‘Accelerated SuFEx Click Chemistry’ (ASCC), an improved SuFEx method for the efficient and catalytic coupling of aryl and alkyl alcohols with a range of SuFExable hubs. We demonstrate Barton’s hindered guanidine base (2-tert-butyl-1,1,3,3-tetramethylguanidine; BTMG) as a superb SuFEx catalyst that, when used in synergy with silicon additive hexamethyldisilazane (HMDS), yields stable S-O bond linkages in a single step; often within minutes. The powerful combination of BTMG and HMDS reagents allows for catalyst loadings as low as 1.0 mol% and, in congruence with click-principles, provides a scalable method that is safe, efficient, and practical for modular synthesis. ASSC expands the number of accessible SuFEx products and will find significant application in organic synthesis, medicinal chemistry, chemical biology, and materials science.

Keywords: click chemistry, guanidines, organocatalysis, synthetic methods, SuFEx

Graphical Abstract

We report accelerated SuFEx click chemistry utilizing a synergistic BTMG-HMDS catalytic system. The power and versatility of the reaction are showcased by the SuFEx synthesis of >100 unique molecules from diverse SuFExable hubs. Accelerated SuFEx is a next generation click reaction that improves upon existing protocols and expands the scope of accessible products.

The catalytic Sulfur(VI) Fluoride Exchange (SuFEx)[1–3] reaction, developed by Sharpless and co-workers in 2014, is becoming accepted as a second ideal click reaction for erecting stable and pharmacophoric linkages between pre-functionalized modules. The copper-catalyzed azide-alkyne cycloaddition (CuAAC), its predecessor, was found in 2002 and represents a truly perfect reaction[4,5]. Between them, these two transformations are enabling unprecedented reliability and speed in producing in new substances in the never-ending quest to find functional molecules[6–8].

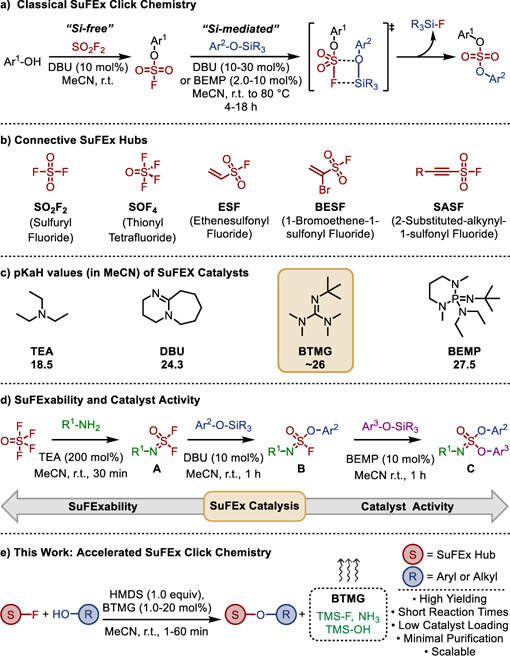

Classical SuFEx typically involves substituting stable S-F bonds with aryl silyl ethers to give the corresponding S-O union (Fig 1a); although SuFEx reactions can also occur with amines[9–11], organometallic reagents[12], and other carbon nucleophiles[13] to yield stable S-N and S-C bonds, respectively. The operational simplicity and robust nature of SuFEx, coupled with the wide commercial availability of SuFExable substrates (sulfonyl fluorides, alcohols, amines, etc.), render this modern click reaction ideal for high-throughput modular synthesis[14] and for accessing diverse click libraries[15]. Another feature unique to SuFEx is the growing number of versatile SuFExable hubs, including SO2F2, SOF4, ESF, BESF, and SASFs[1,16–21], that serve as robust connectors for creating diverse functional molecules and expanding the ever-growing applications of click chemistry (Fig 1b)[21–26].

Fig 1. SuFEx Click Chemistry;

a) Classical Si-free and Si-mediated SuFEx click reactions; b) Exemplary connective SuFEx hubs for modular click chemistry; c) pKaH values of representative SuFEx catalysts; d) Example of the relationship between SuFExability and catalyst activity; e) The development of BTMG-HMDS mediated Accelerated SuFEx Click Chemistry (ASCC); direct coupling of aryl and alkyl alcohols with SuFExable hubs mediated by HMDS.

Pivotal to SuFEx reactivity is the transition of fluoride from a stable covalent S-F bond to a leaving group; a process assisted by interactions with H+, R3Si+ and/or mediated by catalysts including basic tertiary amines (e.g., triethylamine, TEA), amidines (e.g., DBU), phosphazenes (BEMP), and/or bifluoride ion salts[1,27–31] (Fig 1c). The relative electrophilicity of the sulfur core — a useful measure of ‘SuFExability’ — reflects the need for different catalysts; stronger bases being required to catalyze the SuFEx reactions of increasingly stable substrates as each S-F bond is replaced (e.g., SOF4 → A → B C, Fig 1d). Steric factors also play an important role in SuFEx catalyst function; hence, through judicious selection of a catalyst and reaction conditions, impressive chemoselectivity between SuFExable functionality is possible[32,33].

The fidelity and versatility of SuFEx secures its place as a near-perfect click reaction; nevertheless, there are opportunities for improvement. For example, SuFEx reactions are sometimes disadvantaged by the need for relatively high catalyst loadings (>30 mol%)[1,30], particularly when the reaction conditions expedite catalyst degradation.[34,35]. Another factor affecting the rate of SuFEx reactions is the steric bulk around the silicon center. Smaller silyl groups like trimethylsilyl ethers tend to react rapidly, whereas bulkier tert-butyldimethylsilyl groups can require several hours for the reaction to reach completion[1]. Several prototypical examples of silicon-free SuFEx reactions with aryl alcohols[1,36,37] that negate the need to prepare the silyl ethers have been developed. While eliminating synthetic steps is practical and has both environmental and economic benefits, particularly when synthesizing large libraries of compounds[15], Si-free reactions do not profit from the formation of the thermodynamically favorable Si-F bond (BDE = 135 kcal mol–1), and can also require stoichiometric catalyst loadings.

We report herein the development of ‘Accelerated SuFEx Click Chemistry’ (ASCC), a universal and improved method for clicking SuFExable hubs directly with alcohol substrates (Fig 1e). We demonstrate powerful SuFEx catalysis by the sterically hindered 2-tert-butyl-1,1,3,3-tetramethylguanidine (Barton’s base, BTMG)[38,39] that, when used in concert with the silicon additive hexamethyldisilazane (HMDS), delivers SuFEx products in high yield within a matter of minutes.

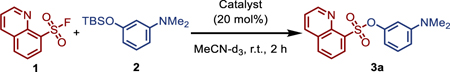

Recent findings by Kelly, Sharpless and co-workers implicating arginine residues as potential mediators of biological SuFEx reactions caught our attention: a fluorosulfate probe was demonstrated to react selectively with a tyrosine residue situated within a conserved Arg-Arg-Tyr motif found in the binding site of intracellular lipid-binding proteins[40]. Experimental results suggest that the proximal guanidine-containing amino acid facilitates this covalent reaction by lowering the pKa of the Tyr-OH residue and stabilizing the departing fluoride anion. Since guanidine-type bases have been largely overlooked in the context of SuFEx click chemistry[41,42], we elected to explore this style of biomimetic catalysis. A screen of guanidine bases (20 mol%) was performed on the relatively sluggish SuFEx reaction between 8-quinolinesulfonyl fluoride (1) and the hindered tert-butyl-dimethylsilyl ether of 3-dimethylaminophenol (2) in acetonitrile (Table 1). Barton’s hindered guanidine base (BTMG) was identified as the standout catalyst[43–45], accelerating the reaction between 1 and 2 to completion within just 2 hours (Table 1, Entry 6). In contrast, the comparative reaction catalyzed by DBU achieved only 17% conversion over the same period (Table 1, Entry 1). The SuFEx catalyst KHF2[31] failed to deliver product 3a within 5 minutes (Table 1, Entry 8). As a base, BTMG pKaH ~26 (in MeCN)[46] occupies a ‘sweet spot’ sitting between DBU (pKaH = 24.3 in MeCN)[35] and BEMP (pKaH = 27.6 in MeCN)[47], affording a unique balance between reactivity and selectivity.

Table 1. SuFEx catalyst screen.

Reactions were performed on 0.1 mmol scale, and conversions were determined by 1H NMR analysis.

| ||

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Entry | Catalyst | Conversion (%) |

|

| ||

| 1 | DBU | 17 |

| 2 | l-arginine methyl ester•HCl | 0 |

| 3 | N-Boc- l-arginine methyl ester | 0 |

| 4 | 1,3-diphenylguanidine | 0 |

| 5 | 1,1,3,3-tetramethylguanidine | 0 |

| 6 | BTMG | >99 |

| 7 | 1,5,7-triazabicyclo(4.4.0)dec-5-ene | 0 |

| 8 | KHF2 | 0 |

BTMG is known to generate phenolate anions effectively[38,39], and we found that it could also enable catalytic SuFEx directly with alcohol substrates. We considered whether a suitable silicon additive could work synergistically with BTMG to activate the SuFEx process and sequester the released fluoride ion, thereby by preventing catalyst degradation by HF and allowing optimal loading (cf. DBU)[34].

Several silicon reagents, including TMS-OH[48,49], hexamethyldisiloxane, and HMDS, were screened in the SuFEx reaction between 4-(trifluoromethyl)benzenesulfonyl fluoride (4) and sesamol (5) with BTMG (Table 2). HMDS (1.0 equiv) was found to be the superior choice when used with 20 mol% BTMG, with quantitative conversion through to the sulfonate product 3b observed in just 1 min (Table 2, entry 6). The control reaction in the absence of HMDS reached only 77% conversion after 5 min (Table 2, entry 1). Further, we found that the catalyst loading could be lowered to 1.0 mol% without impacting the reaction rate (Table 2, Entry 9), but lower levels (e.g., 0.1 mol%) resulted in longer reaction times to reach the same level of conversion.

Table 2. Optimization of silicon additive and catalyst loadings.

Reactions were performed on 0.1 mmol scale, and conversions were determined by 1H NMR analysis.

| ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Entry | Si additive (equiv) | Catalyst (mol%) | T (min) | Conversion (%) |

|

| ||||

| 1 | — | BTMG (20) | 5 | 77 |

| 2 | — | DBU (20) | 30 | 20 |

| 3 | — | BTMG (1.0) | 5 | 18 |

| 4 | TMS-OH (1.0) | BTMG (20) | 5 | >99 |

| 5 | (TMS)2O (1.0) | BTMG (20) | 5 | >99 |

| 6 | HMDS (1.0) | BTMG (20) | 1 | >99 |

| 7 | HMDS (1.0) | BTMG (10) | <5 | >99 |

| 8 | HMDS (1.0) | BTMG (5.0) | <5 | >99 |

| 9 | HMDS (1.0) | BTMG (1.0) | <5 | >99 |

| 10 | HMDS (1.0) | BTMG (0.5) | 30 | 96 |

| 11 | HMDS (1.0) | BTMG (0.1) | 60 | 98 |

| 12 | HMDS (1.0) | DBU (20) | 1 | >99 |

| 13 | HMDS (1.0) | DBU (1.0) | 180 | 67 |

| 14 | HMDS (1.0) | DBU (0.1) | 180 | 1.5 |

| 15 | HMDS (0.5) | BTMG (1.0) | 30 | 66 |

Recently, Niu and co-workers reported a one-pot SuFEx O-sulfation employing HMDS as an in situ silylating agent[42] in the presence of DBU. We too observed that HMDS markedly accelerates the DBU catalyzed SuFEx reaction: with 20 mol% DBU, a 20% conversion to the sulfonate 3b was noted after 30 minutes (Table 2, Entry 2), compared to >99% in just 1 minute (Table 2, Entry 12) when used in concert with HMDS. However, we find the BTMG-HMDS mediated conditions superior overall with the benefit of allowing simple product purification by removing the volatile BTMG catalyst and reaction by-products (e.g.,TMS-F[49], TMS-OH[50], Fig 1e).

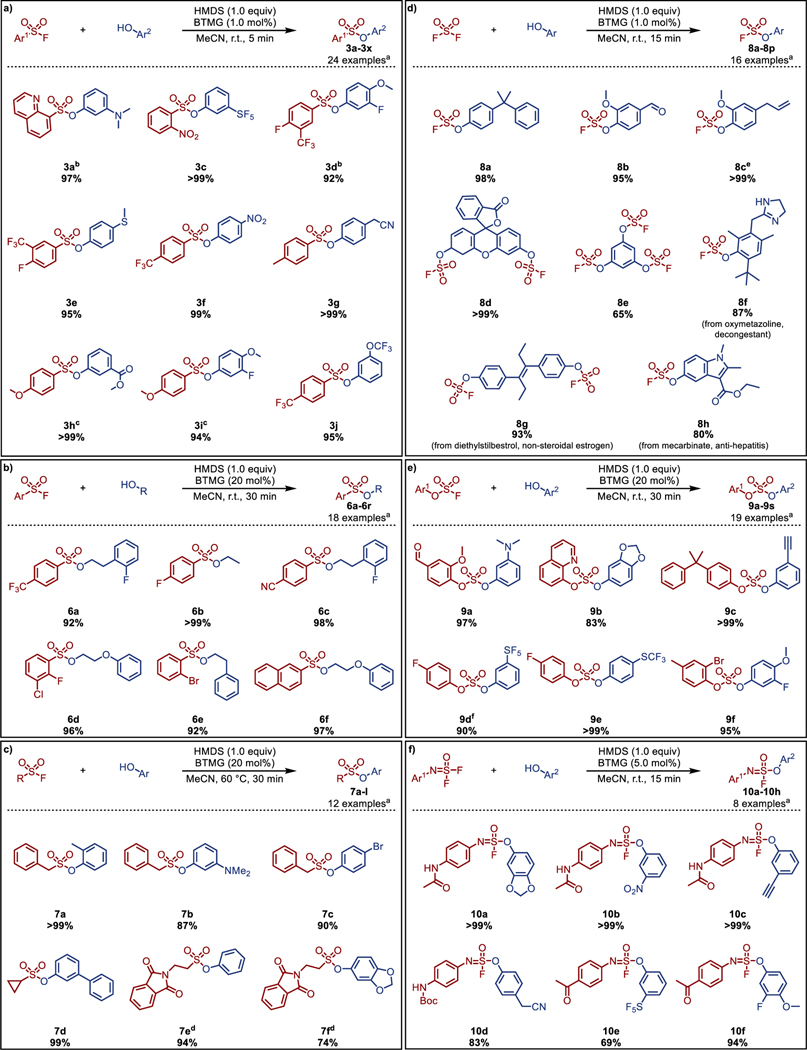

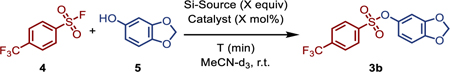

We next explored the substrate scope with a selection of aromatic sulfonyl fluorides and aryl alcohols (Scheme 1a; see Supporting Information for a complete list of examples). The coupling of electron-poor sulfonyl fluorides with electron-poor and electron-rich aryl alcohols proceeded smoothly under the new ASCC conditions. Most reactions reached complete conversion within 5 minutes to afford the sulfonate products 3a–3x in excellent isolated yields. The products were quickly recovered in each case by evaporating the volatile components under reduced pressure or passing the reaction mixture through a short pad of silica. In some instances, with electron-rich sulfonyl fluoride substrates, increased catalyst loadings and reaction times were found necessary (e.g., 3h, 3i). Notably, the reaction performed well with nitrogen heterocyclic sulfonyl fluorides (e.g., 3a, 3p).

Scheme 1. BTMG-HMDS mediated ASCC reaction between a variety of SuFEx hubs and aryl or alkyl alcohols.

Reaction conditions: a) Aromatic sulfonyl fluoride (0.1 mmol), aryl alcohol (0.1 mmol), HMDS (0.1 mmol), and BTMG (1.0 mol%) stirred in MeCN for 5 min; b) Aromatic sulfonyl fluoride (0.1 mmol), alkyl alcohol (0.1 mmol), HMDS (0.1 mmol), and BTMG (20 mol%) stirred in MeCN for 30 min; c) Alkyl sulfonyl fluoride (0.2 mmol), aromatic alcohol (0.1 mmol), HMDS (0.1 mmol), and BTMG (20 mol%) stirred in MeCN under microwave irradiation for 30 min at 60 °C; d) Aryl alcohol (0.1 mmol), HMDS (0.1 mmol), and BTMG (5.0 mol%) were stirred in MeCN under an atmosphere of sulfuryl fluoride (balloon) for 15 min; e) Aryl fluorosulfate (0.1 mmol), aryl alcohol (0.1 mmol), HMDS (0.1 mmol), and BTMG (20 mol%) were stirred in MeCN for 30 min; f) Iminosulfur oxydifluoride (0.1 mmol), aryl alcohol (0.1 mmol), HMDS (0.1 mmol), and BTMG (5.0 mol%) were stirred in MeCN for 5 min; [a]Select examples shown, see Supporting Information for a full list of examples; [b]Reaction stirred for 30 min using 5.0 mol% BTMG; [c]Reaction stirred for 60 min using 10 mol% BTMG; [d] Reaction conducted on 0.2 mmol scale using 1.0 equiv of alkyl sulfonyl fluoride; [e]Conducted on a 50 mmol scale; [f]Reaction run for 20 min.

SuFEx reactions with aliphatic alcohol nucleophiles are rare and more challenging than with aryl alcohols, not least due to competing SN2 pathways of the sulfonate products[51,52]. Under ASCC conditions, SuFEx between aromatic sulfonyl fluorides and primary alkyl alcohols proceed smoothly at room temperature, albeit requiring a high catalyst loading of 20 mol% (Scheme 1b; see Supporting Information for a complete list of examples). The transformations are generally complete within 30 minutes, delivering the sulfonate products 6a–6r in high yield and purity. Even secondary alkyl alcohols under microwave-assisted heating to 60 °C for 30 minutes gave good product yields (e.g., 6g, 6h, 6q, and 6r). Alkyl sulfonyl fluoride substrates also perform well under microwave irradiation (Scheme 1c; see Supporting Information for a complete list of examples), expanding the scope of SuFEx to alkyl variants of both coupling partners (7a–7l). However, attempts to couple alkyl sulfonyl fluorides with alkyl alcohol substrates under the ASCC reaction conditions proved unfruitful.

The sulfuryl fluoride (SO2F2) connective hub — an invaluable reagent that grants access to fluorosulfates for further derivatization — was next investigated. The classic SuFEx reaction between SO2F2 and aryl alcohols generally requires at least 1.5 equivalents of the given base catalyst (e.g., TEA), with prolonged reaction times between 2–6 hours. Under accelerated SuFEx conditions with 5.0 mol% loading of BTMG, we find that the reactions are generally complete within 15 minutes to deliver the fluorosulfates (8a–8p) in excellent yield (Scheme 1d; see Supporting Information for a complete list of examples). Particularly noteworthy are the syntheses of the fluorosulfate derivates of the drugs oxymetazoline (8f), diethylstilbestrol (8g), and mecarbinate (8h). The challenging benzene-1,3,5-triyl tris(sulfurofluoridate) (8e) is also accessible in good yield directly from benzene-1,3,5-triol; this is a marked improvement over the previously reported synthesis of 8e from benzene-1,3,5-tris(trimethylsilyl)ether, which required a 4 h reaction time and high catalyst loading (30 mol% DBU)[1]. The accelerated SuFEx protocol with SO2F2 is also readily scalable, and exemplified by the 50 mmol scale synthesis of fluorosulfate 8c from eugenol (Scheme 1d).

Fluorosulfates are themselves SuFExable substrates, although generally requiring longer reaction times than their aryl sulfonyl fluoride counterparts. For example, the accelerated SuFEx coupling of aryl fluorosulfates and aryl alcohols proceed with good conversion at room temperature in 24 h with a BTMG catalyst loading of 5.0 mol%. Increasing the catalyst loading to 20 mol% results in total consumption of the fluorosulfate starting material within 30 minutes, giving the corresponding diaryl sulfates (9a–9s) in excellent yield (80%–99%) (Scheme 1e; see Supporting Information for a complete list of examples) — even at scale (9I, 40.6 mmol – see SI).

The multidimensional SOF4 derived iminosulfur oxydifluoride hubs also work well: the ASCC coupling of a range of aryl alcohols proceed to completion within 15 minutes with a catalyst loading of just 5.0 mol% at room temperature. This is a significant improvement over DBU, which requires loadings of between 10–20 mol% and a reaction time of over 1 h with aryl silyl ether equivalent substrates. In addition, these reactions are chemoselective with no observed competitive SuFEx of the remaining S-F bond of the sulfurofluoridoimidate products (10a–10h)[16] (Scheme 1f; see Supporting Information for a complete list of examples).

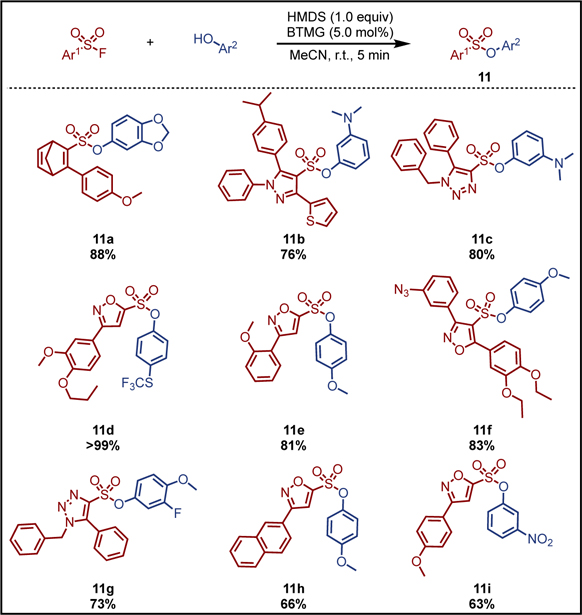

Finally, a selection of diverse sulfonyl fluoride hubs derived from the Diversity Oriented Clicking of BESF[18] and SASF[21]; including pyrazole, 1,2,3-triazoles, diene, and isoxazoles, were explored as substrates (Scheme 2). The aromatic heterocyclic sulfonyl fluoride substrates are notably challenging substrates for SuFEx, often requiring high DBU catalyst loadings and long reaction times with aryl silyl ether substrates. Under accelerated SuFEx conditions, we find that with a catalyst loading of just 5.0 mol%, the reactions between the sulfonyl fluoride hubs and a range of aryl alcohols proceed to completion within just 5 minutes to give the corresponding aryl sulfonate derivatives (11a–11i) in good yields.

Scheme 2. BTMG-HMDS mediated ASCC reaction between BESF/SASF derived sulfonyl fluoride hubs and aryl alcohols.

Reaction conditions: Sulfonyl fluoride hubs (0.1 mmol), aryl alcohol (0.1 mmol), HMDS (0.1 mmol), and BTMG (5.0 mol%) were stirred in MeCN for 5 min.

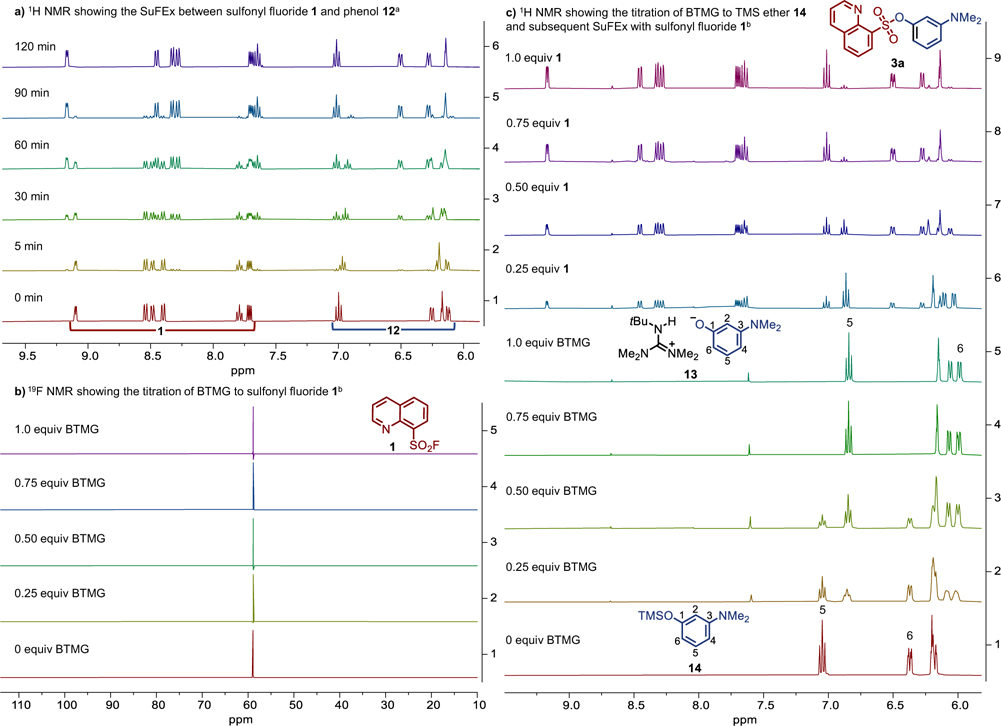

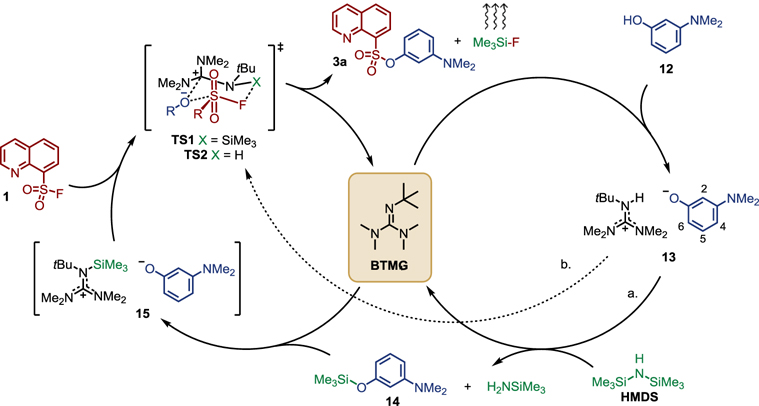

To help elucidate mechanistic details[3,53], we next performed a series of NMR experiments (Fig 2 & Supplementary Information) using the relatively slow SuFEx reaction between 8-quinolinesulfonyl fluoride (1) and 3-(dimethylamino)phenol (12) as a model system. In the presence of 1.0 equivalent of HMDS and 1.0 mol% BTMG, the gradual formation of sulfonate 3a was observed with no apparent intermediates detected on the NMR timescale (Fig 2a, Fig S1).

Fig 2. Key NMR experiments.

All spectra taken in MeCN-d3; 1H NMR = 400 MHz, 19F NMR = 376 MHz; [a]Conducted on a 0.1 mmol scale; [b]Conducted on a 0.05 mmol scale.

Gembus and co-workers proposed a mechanism of activation of p-toluenesulfonyl fluoride by DBU via formation of an arylsulfonyl ammonium fluoride salt[27].. However, titrating the sulfonyl fluoride 1 with 1.0 equivalent of BTMG gave no observable shift in the 19F (Fig 2b) or 1H NMR (Fig S2–S4) spectra, suggesting no obvious interaction between BTMG and 1[27]. We next considered whether the catalytic cycle might begin with deprotonation of the phenol 12 by BTMG to form the guanidinium salt 13. Gradual addition of 1.0 equivalent of BTMG to the phenol 12 in MeCN-d3 resulted in an upfield shift in the aromatic region of the proton spectrum (e.g., H6 shifted from 6.26 to 6.00 ppm and H5 from 7.00 to 6.85 ppm (proton positions labelled in Scheme 3; see Fig S5–S7 for spectra)). The change in chemical shift is consistent with the formation of the phenoxide guanidinium complex 13[54] and was corroborated by the facile reformation of phenol 12 upon addition of deuterated acetic acid (Fig S12)[55]. Titration of the sulfonyl fluoride 1 to the ion pair 13 resulted in the steady formation of the sulfonate product 3a (Fig S8–S9). Collectively, these experiments support 13 as a feasible intermediate in the SuFEx reaction.

Scheme 3.

Plausible catalytic cycle for the BTMG-HMDS accelerated SuFEx reaction.

Next our attention turned to exploring the role of the silicon additive HMDS in the catalytic cycle. As HMDS is known to act as a silylating agent[42], we could not discount the in situ formation of TMS ether 14 during the ASCC reaction. When 14 was titrated with 1.0 equivalent of BTMG (see Fig 2c for aromatic region, see Fig S13–S14 for additional spectra), we observed the rapid BTMG mediated[56,57] desilylation of 14 and formation of the BTMG-phenoxide ion pair 13[58]. Subsequent titration of sulfonyl fluoride 1 to this reaction mixture led to the rapid SuFEx reaction and formation of sulfonate 3a (see Fig 2c for aromatic region, Fig S15–S16 for full spectra), along with TMS-F. The immediate consumption of the sulfonyl fluoride was in stark contrast to the accumulation of 1 when the SuFEx reaction was conducted in the absence of a silicon source (compare Fig S8–S9 to Fig S15–S16), demonstrating the accelerating effect of HMDS.

Based upon these preliminary NMR experiments, we conceive two plausible pathways from the BTMG-phenoxide ion pair 13 (Scheme 3). In path a, the phenoxide ion reacts with HMDS to form the TMS ether 14[42,59]; itself rapidly desilylated by BTMG to form the guanidinium-phenoxide 15[57,60]. The transient intermediate 15 is primed to undergo rapid exchange with the incoming sulfonyl fluoride 1 — perhaps through a six-membered transition state TS1 — whereby the interaction of the fluoride with the TMS group would likely enhance the electrophilicity of the sulfur center, facilitating attack of the closely held phenoxide. In this manner, it is reasonable that a complex such as 15 would activate both the SuFEx electrophile and nucleophile. Alternatively, in pathway b, the ion pair 13 could itself participate directly in the SuFEx reaction via the related transition state TS2[36][33]. In this instance, the proton would activate the sulfonyl fluoride toward phenoxide addition, with the fluoride ion being rapidly sequestered by HMDS. Both pathways a & b yield the sulfonate product 3a, TMS-F, and the regenerated BTMG catalyst. Further work to thoroughly explore the catalytic mechanism is ongoing in our laboratory and will be reported in due course.

To summarize, we report Accelerated SuFEx Click Chemistry (ASCC) as a powerful click method for the rapid coupling of alkyl and aryl alcohols directly with SuFExable hubs – accessing >100 unique products in good to excellent yields. We demonstrate the hindered guanidine base BTMG (Barton’s base) as an excellent SuFEx catalyst that, in concert with the silylating reagent HMDS, functions as a powerful and universal accelerator of SuFEx click chemistry across the board. The accelerated SuFEx reactivity is achieved with relatively low catalyst loadings while circumventing the need to prepare silyl-ether substrates that are required in classical SuFEx click chemistry. The reaction coupling partners are easily prepared or are widely available with great abundance and structural diversity. Product isolation is straightforward through simple evaporation of the volatile BTMG catalyst and side-products, rendering the procedure attractive for high-throughput modular synthesis. We believe accelerated SuFEx click chemistry will be of general interest for modular function discovery in a diverse range of fields.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory for developmental funds from the NCI Cancer Center Support Grant 5P30CA045508 (JEM). In addition, we thank the Sharpless group (Scripps Research) for gifting SOF4 derived substrates.

Footnotes

Institute and/or researcher Twitter usernames: @harborspring; @ClickMoses; @CSHL

Supporting information for this article is given via a link at the end of the document

References

- [1].Dong J, Krasnova L, Finn MG, Sharpless KB, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2014, 53, 9430–9448; Angew. Chem. 2014, 126, 9584–9603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Barrow AS, Smedley CJ, Zheng Q, Li S, Dong J, Moses JE, Chem. Soc. Rev. 2019, 48, 4731–4758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Lee C, Cook AJ, Elisabeth JE, Friede NC, Sammis GM, Ball ND, ACS Catal. 2021, 11, 6578–6589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Tornøe CW, Christensen C, Meldal M, J. Org. Chem. 2002, 67, 3057–3064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Rostovtsev VV, Green LG, Fokin VV, Sharpless KB, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2002, 41, 2596–2599; Angew. Chem. 2002, 114, 2708–2711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6]. The term click chemistry was first coined by K. Barry Sharpless in 1998 and was later published as a concept in 2001 see ref: [7].

- [7].Kolb HC, Finn MG, Sharpless KB, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2001, 40, 2004–2021; Angew. Chem. 2001, 113, 2056–2075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Moses JE, Moorhouse AD, Chem. Soc. Rev. 2007, 36, 1249–1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Wei M, Liang D, Cao X, Luo W, Ma G, Liu Z, Li L, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2021, 60, 7397–7404; Angew. Chem. 2021, 133, 7473–7480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Luy J-N, Tonner R, ACS Omega 2020, 5, 31432–31439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Mahapatra S, Woroch CP, Butler TW, Carneiro SN, Kwan SC, Khasnavis SR, Gu J, Dutra JK, Vetelino BC, Bellenger J, am Ende CW, Ball ND, Org. Lett. 2020, 22, 4389–4394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Gao B, Li S, Wu P, Moses JE, Sharpless KB, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2018, 57, 1939–1943; Angew. Chem. 2018, 130, 1957–1961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Smedley CJ, Zheng Q, Gao B, Li S, Molino A, Duivenvoorden HM, Parker BS, Wilson DJD, Sharpless KB, Moses JE, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2019, 58, 4552–4556; Angew. Chem. 2019, 131, 4600–4604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Kalliokoski T, ACS Comb. Sci. 2015, 17, 600–607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Meng G, Guo T, Ma T, Zhang J, Shen Y, Sharpless KB, Dong J, Nature 2019, 574, 86–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Li S, Wu P, Moses JE, Sharpless KB, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2017, 56, 2903–2908; Angew. Chem. 2017, 129, 2949–2954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Giel M-C, Smedley CJ, Mackie ERR, Guo T, Dong J, da Costa TPS, Moses JE, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2020, 59, 1181–1186; Angew. Chem. 2020, 132, 1197–1202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Smedley CJ, Giel M-C, Molino A, Barrow AS, Wilson DJD, Moses JE, Chem. Commun. 2018, 54, 6020–6023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Leng J, Qin H-L, Chem. Commun. 2018, 54, 4477–4480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Thomas J, Fokin VV, Org. Lett. 2018, 20, 3749–3752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Smedley CJ, Li G, Barrow AS, Gialelis TL, Giel M-C, Ottonello A, Cheng Y, Kitamura S, Wolan DW, Sharpless KB, Moses JE, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2020, 59, 12460–12469; Angew.Chem. 2020, 132, 12560–12569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Li S, Li G, Gao B, Pujari SP, Chen X, Kim H, Zhou F, Klivansky LM, Liu Y, Driss H, Liang D-D, Lu J, Wu P, Zuilhof H, Moses J, Sharpless KB, Nat. Chem. 2021, 13, 858–867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Xu S, Cui S, Org. Lett. 2021, 23, 5197–5202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Liu F, Wang H, Li S, Bare GAL, Chen X, Wang C, Moses JE, Wu P, Sharpless KB, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2019, 58, 8029–8033; Angew. Chem. 2019, 131, 8113–8117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Kitamura S, Zheng Q, Woehl JL, Solania A, Chen E, Dillon N, Hull MV, Kotaniguchi M, Cappiello JR, Kitamura S, Nizet V, Sharpless KB, Wolan DW, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2020, 142, 10899–10904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Zheng Q, Xu H, Wang H, Du W-GH, Wang N, Xiong H, Gu Y, Noodleman L, Sharpless KB, Yang G, Wu P, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2021, 143, 3753–3763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Gembus V, Marsais F, Levacher V, Synlett 2008, 10, 1463–1466. [Google Scholar]

- [28].Barrow AS, Moses JE, Synlett 2016, 27, 1840–1843. [Google Scholar]

- [29].Dong J, Sharpless KB, Kwisnek L, Oakdale JS, Fokin VV, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2014, 53, 9466–9470; Angew.Chem. 2014, 126, 9620–9624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Yatvin J, Brooks K, Locklin J, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2015, 54, 13370–13373; Angew. Chem. 2015, 127, 13568–13571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Gao B, Zhang L, Zheng Q, Zhou F, Klivansky LM, Lu J, Liu Y, Dong J, Wu P, Sharpless KB, Nat. Chem. 2017, 9, 1083–1088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Marra A, Nativi C, Dondoni A, New J Chem. 2020, 44, 4678–4680. [Google Scholar]

- [33].Gahtory D, Sen R, Pujari S, Li S, Zheng Q, Moses JE, Sharpless KB, Zuilhof H, Chem. Weinh. Bergstr. Ger. 2018, 24, 10550–10556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Vorbrüggen H, Synthesis 2008, 2008, 1165–1174. [Google Scholar]

- [35].Hyde AM, Calabria R, Arvary R, Wang X, Klapars A, Org. Process Res. Dev. 2019, 23, 1860–1871. [Google Scholar]

- [36].Liang D-D, Streefkerk DE, Jordaan D, Wagemakers J, Baggerman J, Zuilhof H, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2020, 59, 7494–7500; Angew. Chem. 2020, 132, 7564–7570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Li C, Zheng Y, Rakesh KP, Qin H-L, Chem. Commun. 2020, 56, 8075–8078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Barton DHR, Elliott JD, Géro SD, J. Chem. Soc. Perkin 1 1982, 2085–2090. [Google Scholar]

- [39].Barton DHR, Charpiot B, Motherwell WB, Tetrahedron Lett. 1982, 23, 3365–3368. [Google Scholar]

- [40].Chen W, Dong J, Plate L, Mortenson DE, Brighty GJ, Li S, Liu Y, Galmozzi A, Lee PS, Hulce JJ, Cravatt BF, Saez E, Powers ET, Wilson IA, Sharpless KB, Kelly JW, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016, 138, 7353–7364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Choi EJ, Jung D, Kim J-S, Lee Y, Kim BM, Chem. – Eur. J. 2018, 24, 10948–10952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Liu C, Yang C, Hwang S, Ferraro SL, Flynn JP, Niu J, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2020, 59, 18435–18441; Angew. Chem. 2020, 132, 18593–18599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Barrett AGM, Cramp SM, Roberts RS, Zecri FJ, Org. Lett. 1999, 1, 579–582. [Google Scholar]

- [44].Barrett AGM, Cramp SM, Hennessy AJ, Procopiou PA, Roberts RS, Org. Lett. 2001, 3, 271–273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Wipf P, Lynch SM, Org. Lett. 2003, 5, 1155–1158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Perea-Buceta JE, Fernández I, Heikkinen S, Axenov K, King AWT, Niemi T, Nieger M, Leskelä M, Repo T, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2015, 54, 14321–14325; Angew. Chem. 2015, 127,14529–14533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Kotsuki H in Superbases for Organic Synthesis: Guanidines, Amidines, Phosphazenes and Related Organocatalysts, (Ed.: Ishikawa T), Wiley, Chichester, 2009, pp. 187. [Google Scholar]

- [48].Dr. A. S. Barrow first performed a model SuFEx reaction using BTMG as a catalyst with TMS-OH additive (November 19th, 2019, unpublished results).

- [49].Trimethylsilanol (TMS-OH, 20 equiv) has been employed as a post-SuFEx quench to sequester the fluoride ion product as the volatile fluorotrimethylsilane (TMS-F, b.p. is 16 °C), see: Liu Z, Li J, Li S, Li G, Sharpless KB, Wu P, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018, 140, 2919–2925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].The hydrolysis of HMDS gives the volatile trimethylsilanol (TMS-OH) and ammonia (NH3); for example, see Pellegata R, Italia A, Villa M, Synthesis 1985, 517–519. [Google Scholar]

- [51].Epifanov M, Foth PJ, Gu F, Barrillon C, Kanani SS, Higman CS, Hein JE, Sammis GM, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018, 140, 16464–16468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Tribby AL, Rodríguez I, Shariffudin S, Ball ND, J. Org. Chem. 2017, 82, 2294–2299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Fu X, Tan C-H, Chem. Commun. 2011, 47, 8210–8222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Pross A, Radom L, Taft RW, J. Org. Chem. 1980, 45, 818–826. [Google Scholar]

- [55].Comparison of the 13C NMR spectra of ion pair 13 to BTMG-trifluoroacetate ion pair 16 (Fig S11) added further support for the existence of an ion pair; the partial convergence of the BTMG NMe2 peaks (due to the now facile interconversion of the two mesomeric forms) is indicative of a guanidinium cation, see; Rappo-Abiuso M, Llauro M-F, Chevaliera Y, Le Perchec P, Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys 2001, 3, 99–106. [Google Scholar]

- [56].The DBU-mediated de-silylation of aryl silyl ethers has been reported: Yeom C-E, Kim HW, Lee SY, Kim BM, Synlett 2007, 1, 146–150. [Google Scholar]

- [57].Soderquist JA, Soto-Cairoli B, Kock I, Yang G, Justo de Pomar J, Guzmán JM, González JR, Antomattei A, Heterocycles 2010, 80, 409. [Google Scholar]

- [58].The TMS ether signal (0.23 ppm) disappeared along with residual water (2.13 ppm) to give a new peak at 0.06 ppm, likely attributed to the formation of TMS-OH or TMS2O (Fig S14).

- [59].Joseph AA, Verma VP, Liu X-Y, Wu C-H, Dhurandhare VM, Wang C-C, Eur. J. Org. Chem 2012, 2012, 744–753. [Google Scholar]

- [60].Wang L, Huang X, Jiang J, Liu X, Feng X, Tetrahedron Lett. 2006, 47, 1581–1584. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.